Abstract

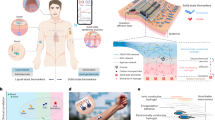

Severe hypoxia within thick bioengineered tissues critically impairs cell viability and function, limiting their application in organ-scale engineering and regenerative medicine. Current methods for oxygen delivery often fall short of providing sustained oxygenation before neovascularization. Here, we introduce a smart self-oxygenating tissue (SSOT) platform that leverages a bio-ionic liquid (BIL)-functionalized biocompatible hydrogel electrolyte for localized and controlled oxygen generation via electrolysis. Comprehensive characterization of the system confirmed stability and electrochemical properties, with molecular dynamics simulations demonstrating that BIL enhances oxygen release. In vitro, the SSOT platform maintains cell viability and promotes vascularization under severe hypoxic conditions. Diabetic wound healing studies using mouse models showed that an SSOT patch accelerates wound closure in chronic and non-chronic wounds. These findings highlight the potential of electrolysis-driven methods for providing on-demand and sustained oxygen delivery, essential for the development of functional living tissues and ultimately organs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the quest for more precise and representative models of human physiology, bioengineered tissue platforms are emerging as a valuable tool in biomedical research. Traditional small-animal models often fall short due to significant phenotypic and genetic differences that limit their ability to recapitulate normal and aberrant biological processes1,2. Engineered tissue models overcome these limitations by offering a high degree of biomimicry, reproducibility, and control, making them invaluable for studying disease mechanisms and testing new therapeutics. They provide a precise way to study the effects of specific molecular factors, drugs, cell types (such as parenchymal, vascular, and immune cells), and micro-physiological configurations (such as geometry and the presence of dynamic flow or mechanical forces) on functional responses3,4,5,6. By reducing confounding variables such as genetic variability, tissue-engineered models deliver more reliable and consistent results, offering insights that directly translate to humans.

Moreover, tissue-engineered implants offer a promising alternative to traditional organ transplantation, addressing issues such as donor organ shortages, high costs, unpredictable surgeries, and lifelong immunosuppression7,8,9. As of September 2020, over 109,000 individuals were on the organ transplant waitlist in the U.S., with approximately 20 deaths daily due to the lack of suitable donors10. Developing viable, lab-grown human tissues that integrate with the patient’s body could reduce reliance on donor organs. However, maintaining cell viability in larger tissue constructs remains challenging due to insufficient oxygen and nutrient diffusion. When the distance between cells and blood vessels exceeds 100–200 μm, hypoxia and anoxia occur, leading to tissue necrosis and cell death11. While hypoxia can stimulate angiogenesis, anoxia inhibits aerobic respiration and ATP production, ultimately destroying the vascular network and resulting in cell death. A consistent oxygen supply is crucial for the survival and functional maturation of bioengineered tissues until neovascularization is achieved12,13,14.

Oxygen deficiency severely restricts the scale and functionality of bioengineered tissues. Relying on passive oxygen diffusion without a pre-formed vascular network results in inadequate oxygen penetration and necrotic core formation in large constructs. Current strategies to bolster oxygen release include incorporating angiogenic factors to stimulate vessel formation and using oxygen carriers like perfluorocarbons (PFCs), silicon oil, and crosslinked hemoglobin. However, these methods fall short of providing sustained and adequate oxygenation during the critical pre-vascular phase15,16,17,18. Bioreactors and microfluidic techniques can facilitate blood vessel formation but are only applicable in vitro19,20. Porous interconnected scaffolds are increasingly being explored, but they are associated with heterogeneous oxygen distribution, which is highly dependent on pore size and architecture21,22. Oxygen-generating biomaterials (ORBs) have shown promising results for localized oxygen release, preventing anoxia-induced cell death. Common approaches involve using solid inorganic peroxides23, liquid peroxides24, and photosynthetic microalgae25 to continuously generate oxygen. This concept can be integrated into the fabrication of hydrogels, polymer films, fibers, and 3D-printed scaffolds to provide a controlled and long-lasting oxygen supply26,27,28,29,30. It has been previously demonstrated to sustain cell viability and promote angiogenesis, collagen synthesis, and bacterial eradication, all of which are crucial for implant integration with host tissue. However, the oxygen release function with these approaches is often short-lived, and the challenge of oxygenation before the formation of a functional neo-vasculature remains unsolved.

Electrochemical systems have emerged as a compelling alternative for oxygen production due to their precise control over oxygen-release kinetics. This approach utilizes electrochemical principles to split water into oxygen and hydrogen, enabling a localized oxygen supply. Most existing knowledge comes from industrial applications such as hydrogen production for fuel cells and wastewater treatment31,32. Only a few studies have explored electrolysis-mediated oxygen generation in biological contexts, which require biocompatible, miniaturized, and power-efficient systems33,34. Our previously patented work introduced a biocompatible electrocatalytic system for controlled oxygen generation within bioengineered scaffolds, demonstrating its potential for sustained cell growth and survival35. A recent study by Lee et al. demonstrated that an iridium oxide electrocatalyst platform significantly improved cell viability under hypoxic conditions after 10 days of implantation in rats36. Integrating electrolysis-driven oxygenation into bio-fabrication of thick implantable tissues requires consideration of components beyond the electrocatalyst. In the context of tissue engineering, consideration of the electrolyte is crucial for developing multifunctional self-oxygenating platforms. Conventional liquid electrolyte-based systems face challenges like leakage, while solid-state electrolytes are unsuitable for soft tissues and dynamic biological environments due to their rigidity37. Bio-ionic liquids (BILs) are an emerging class of biomaterials gaining interest for their ionic conductivity, thermal stability, biocompatibility, and bioadhesive properties37,38,39,40. Their tunable chemical structures allow optimization for specific applications. Previous publications demonstrated the potential of choline BIL-functionalized gelatin methacryloyl (BioGel) hydrogels in enhancing cell viability, proliferation, and differentiation within bioengineered tissues39,41,42.

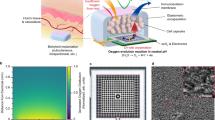

Here, we introduce a smart self-oxygenating tissue (SSOT) platform utilizing a BioGel combined with cobalt phosphate (CoP) or platinum (Pt) electrodes for on-demand, localized oxygen generation. The BioGel electrolyte is fabricated by incorporating BIL into gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), creating an electroconductive scaffold that supports both electrolysis and cell growth. We assessed the physicochemical properties, electroconductivity, and oxygen generation capabilities of the SSOT setup. Full atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations demonstrated that BIL enhances oxygen release, improving the SSOT’s ability to mitigate hypoxia. In vitro studies revealed that the oxygen-generating capability of the platform enhanced cell viability and facilitated rapid vascularization under hypoxia (1% and 5% O2). The technology significantly accelerated wound healing, increased collagen deposition, and promoted angiogenesis in diabetic wound healing models with minimal immune response. This platform represents a comprehensive approach for controlled, prolonged oxygen delivery within bioengineered tissues, addressing challenges in creating clinically sized implants by integrating flexible electronics, electrocatalysis, and tissue engineering.

Results and discussions

Design considerations and physical characterization of the SSOT platform

The SSOT setup was meticulously designed to tackle the prevalent challenge of inadequate oxygen supply in thick bioengineered tissues. This platform integrates a biocompatible hydrogel electrolyte and high-performance electrocatalysts connected to a power source to ensure sustained and localized oxygen generation essential for maintaining cell viability in clinically sized tissue constructs (Fig. 1A). Two electrode configurations were explored: Pt and a 3D-printable composite electrode comprising GelMA, Laponite, and CoP. The Pt electrodes were selected for their well-documented stability and efficiency in catalyzing the oxygen evolution reaction (OER)43. The CoP composite electrodes offered a cost-effective alternative, leveraging the synergistic properties of the materials to enhance catalytic activity while maintaining biocompatibility. Central to the SSOT technology is the BioGel electrolyte, synthesized by incorporating a choline-based BIL into a GelMA matrix (Fig. 1B). This modification imparts ionic conductivity, thermal stability, and adhesive properties to the hydrogel, as well as antimicrobial effects, resulting in a multifunctional electrolyte39,40,41,44. To develop an effective self-oxygenating platform, several parameters were investigated, including the inter-electrode distance, electrolyte thickness, and the optimal voltage required for stable oxygen generation within the system.

A Schematic illustration of the oxygenating system and its application in designing thick tissue constructs and promoting tissue regeneration. B Chemical synthesis pathway of the BIL and BioGel, detailing the reaction of choline bitartrate with acrylic acid to form choline acrylate BIL, which is subsequently conjugated with GelMA, resulting in BioGel. Mechanical properties of the BioGel electrolyte are presented with respect to C compression modulus and D elastic modulus for GelMA conjugated with varying concentrations of BIL. E The degradation ratio of the BioGel electrolyte was evaluated from 0 to 14 days, and F swelling ratio from 0 to 24 h. The composition of BioGel included GelMA at 7% (w/v) with BIL concentrations of 0, 2, 4, and 6% (w/v), along with 0.5% lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) as a photoinitiator. This was subjected to 60 seconds of 405 nm light to form the structure. Data represent means ± SEM (n = 4) with P values determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (statistical significance denoted by ns–no significance, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

The mechanical properties of the BioGel electrolyte were observed to significantly improve with increasing BIL concentrations (Fig. 1C, D). The compressive modulus of 7% (w/v) GelMA is 4.0 ± 1.0 kPa, while its elastic modulus is 6.43 ± 0.92 kPa. Following the addition of 4% (w/v) BIL, these values increased to 8.3 ± 0.3 kPa for compressive modulus and 17.83 ± 1.25 kPa for elastic modulus. The elevated mechanical properties are attributed to the increased density of electrostatic interactions due to the larger number of BIL groups. The quaternary ammonium of the BIL pendant group interacts electrostatically with the OH and NH2 bonds on the polymer’s main chain, preventing chain slippage and movement during mechanical tests. This interaction increases modulus and yield strength45. The BIL groups also form electrostatic clusters that act as physical crosslinking nodes, making chain rotation difficult and contributing to higher elastic and compressive moduli. In ionomers, ionic pendant groups can similarly act as physical crosslinkers through ionic clustering or physical aggregation due to electrostatic interactions. These temporary crosslink nodes occur in clusters or multiplets, where lower percentages of BIL may dominate, anchoring polymer chains and restricting mobility, while the more flexible portions of the chain reinforce flexibility, leading to increased toughness41,46,47.

The degradation rate and swelling ratio of BioGel offer insights into its functionality (Fig. 1E, F). The degradation behavior of BioGel also depends on BIL content. As shown in Fig. 1E, the degradation rate increases significantly from day 1 to day 14 for all BIL concentrations. GelMA without BIL has an initial degradation rate of 15.0% ± 2.0 kPa, which increases to 30.0 ± 2.0 kPa for BioGel with 2% BIL. This increase is attributed to the catalytic effect of the quaternary ammonium head in choline, which facilitates hydrolysis42. Higher BIL content further accelerates degradation, with BioGel containing 4% and 6% BIL showing degradation rates exceeding 50% by day 14. GelMA without BIL functionalization absorbs water more rapidly than BIL-conjugated BioGel. The swelling ratio for GelMA is 33.6%, while for BioGel with 2% BIL, it drops to 24.3% (Fig. 1F). Stronger electrostatic interactions between BIL moieties restrict polymer expansion, leading to controlled swelling. As BIL content increases, the polymer network’s polarity and hydrophilic character are enhanced, resulting in higher swelling ratios for BioGel with 4% BIL compared to 2% BIL.

The overall BioGel structure balances degradation and swelling through dynamic interactions that ensure hydrogel stability and flexibility. Initially, the hydrogel absorbs water, causing polymer chains to enter a local semi-dilute region with overlapping blobs and hydration spheres48. Lower BIL content allows these blobs to open rapidly, facilitating water absorption until equilibrium swelling is reached. Higher BIL content creates electrostatic clusters that initially restrict water access, limiting swelling. Water continues to hydrate the gel due to the concentration gradient between the inside and outside of the gel’s semi-dilute phase. The hydrogel swells until the polar and ionic groups are fully hydrated or until network constraints prevent further expansion. In the presence of BIL clusters, primary-bound water forms consolidated ionic aggregate clusters with the quaternary ammonium groups, pausing further swelling and preventing overexpansion42.

Proteolytic degradation is a vital consideration in the design of hydrogels for tissue repair, as it directly influences scaffold stability, cell-mediated remodeling, and extracellular matrix (ECM) regeneration. Collagenases, a subset of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1, -8, and -13), mediate the enzymatic cleavage of collagen-based biomaterials by targeting specific Gly-Leu/Ile peptide motifs49,50. To evaluate the proteolytic stability of the BioGel electrolyte, we assessed degradation in the presence of collagenase II over 7 days, using GelMA hydrogels as controls. When exposed to 10 U mL−1 collagenase II, GelMA exhibited rapid degradation with 38 ± 6 % mass loss within 12 h, exceeding 90 % by day 3, and complete degradation by day 7. Increasing the collagenase II concentration to 50 U mL−1 further accelerated degradation, resulting in 67 ± 4 % mass loss within 12 h and complete hydrolysis within 24 h (Supplementary Fig. S1). These results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating dose-dependent degradation of GelMA hydrogels. For instance, 5 wt % GelMA hydrogels have been reported to degrade fully within 3 days at enzyme concentrations as low as 2 U mL−1, whereas more concentrated formulations (20 wt%) retained partial structural integrity even after extended collagenase exposure51. Another study reported that low-density GelMA ( ≤ 10 wt%) underwent complete degradation within 24 h, while more densely crosslinked 15 wt % GelMA hydrogels persisted significantly longer under comparable enzyme conditions52.

Remarkably, BioGel demonstrated significantly enhanced proteolytic stability compared to GelMA, exhibiting only 23 ± 3 % and 25 ± 2 % mass loss at 10 U mL−1 and 50 U mL−1 collagenase II, respectively, after 7 days. This substantial increase in stability ( ≈ 3-fold slower degradation) is attributed to the cationic functionalization, which maintains hydrogel integrity. The presence of densely grafted quaternary ammonium groups from choline bitartrate likely confers electrostatic repulsion against collagenase II (pI ≈ 5.5) and restricts enzyme access to susceptible cleavage sites. Similar protective effects have been previously reported, where cationic modifications effectively diminished collagenase-mediated degradation of gelatin-based hydrogels and microspheres, further corroborating our findings53,54. These results show that bio-ionic liquid incorporation, as implemented in BioGel, offers a promising strategy for enhancing hydrogel stability in protease-rich physiological environments. This is particularly advantageous for chronic wounds, where prolonged structural integrity and controlled degradation are essential for therapeutic efficacy and integration with host tissue.

Electroconductivity and oxygen generation in SSOT constructs

The development of biocompatible and biodegradable conductive materials is essential for biological applications where conductivity is preferred. Conventional methods to engineer conductive hydrogels (CHs) often involve incorporating conductive nanomaterials and polymers, which can lead to cytotoxicity, reduced solubility, poor processability, and degradability55. To address these challenges, we utilized BioGel, a choline BIL-modified hydrogel as a biocompatible conductive electrolyte in the development of an SSOT construct. The efficacy of BioGel hydrogel, both as an electrolyte and an adhesive with high tissue adhesion, has been demonstrated in our previous work35,38,39.

In the SSOT technology, BioGel serves as a conductive and adhesive hydrogel scaffold for electrocatalysis, in addition to supporting cell survival and growth. The BioGel electrolyte is synthesized by incorporating BIL into GelMA. Electroconductive characterization was performed using cyclic voltammetry, conductivity measurements, and Nyquist plots with varying BIL percentages (Fig. 2A(i–iii)). The conductivity of GelMA without BIL was 6 × 10−4 ± 0.7 × 10−4 S/m, increasing to 190 × 10−4 ± 6 × 10−4 S/m for 6% (w/v) BIL. The cyclic voltammetry curve shows a current response to a potential sweep, with a peak at 0.9 V indicating the OER (Fig. 2A(iv)). BIL concentration in BioGel influences oxygen generation, with a strong OER peak at 4% w/v BIL. Increased BIL concentration shifts both reduction and oxidation peaks to the onset potential of OER, enhancing electrocatalytic efficiency. The alternating current and potential response of BioGel over time suggests a stable and cyclical electrochemical reaction within the system (Fig. 2A(v)). Capacitance retention of the SSOT, shown by constant current charge/discharge cycles, indicates excellent stability and retention of electrochemical properties, crucial for long-term applications (Fig. 2A(vi)).

A (i) EIS and cyclic voltammetry analysis with a three-electrode setup to deduce the electrochemical properties of BioGel electrolyte (ii) Quantified conductivity of BioGel electrolyte with varying BIL content (iii) Nyquist plot indicating impedance characteristics of BioGel electrolyte with different percentages of BIL. (iv) Cyclic voltammetry curve of BioGel with a voltage of 1 V using Ag/AgCl reference electrode shows the current response to potential sweep. (v) Alternating current and potential response of BioGel over time. The pattern suggests a stable and cyclical electrochemical reaction occurring within the system. (vi) Capacitance retention of SSOT shown by constant current charge/discharge cycles. B (i) Experimental setup for quantitative analysis of oxygen generated using a probe sensor (ii) Oxygen ON/OFF study depicting the oxygen production sustainability of the SSOT in vitro when powered intermittently with 1 V DC; inset shows the synthesized oxygen concentration over a 7-day period. (iii) Oxygen concentration synthesized in mg/L over time. (iv) Different oxygen concentrations produced by varying BIL concentrations in the BioGel electrolyte indicate BIL concentration-dependency in oxygen production. C (i) Visualization of oxygen generation in BioGel electrolyte using a 2D sensor foil connected to a detection system powered by a DC supply at 1 V. (ii) Observation of the evolution of oxygen within the electrolyte over time, with the voltage alternately turned on and off. Data represented as means ± SEM (n = 4) with statistical significance indicated by P values from one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (ns–no significance, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

SSOT constructs were further evaluated for electrochemical performance and oxygen generation by connecting them to a DC power supply at 1 V under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 2B). Oxygen concentration was 0.085 ± 0.021 mg/L after 30 min, increasing to 0.525 ± 0.035 mg/L by day 1. By day 2, the concentration increased fivefold to 2.45 ± 0.14 mg/L, indicating steady electrolysis. The steady cycling capacity of the SSOT technology in galvanostatic charge-discharge cycles confirms the stability of the printed setup (Fig. 2B(ii)). A critical challenge in engineering 3D tissues is ensuring an adequate oxygen supply. SSOT technology mitigates this by providing a consistent and controlled oxygen supply, essential for cell survival, growth, proliferation, and vascularization. Consistent oxygen supply is vital, as oxygen is crucial for metabolism and signaling. Although oxidation is fundamental, an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants can harm cells14. To address this, oxygen generation was measured while alternating the power supply on and off at 24-hour intervals (Fig. 2B(ii)). During the initial 24-hour period, oxygen concentration increased from 2.5 mg/L at 15 min to 6.95 mg/L. When the power supply was disconnected for the next 24 h, the concentration was reduced to 3.9 mg/L, reaching 2.3 mg/L in 48 h. This pattern persisted throughout the 30-day period, indicating the capability to modulate oxygen synthesis by regulating the power supply, crucial for preventing oxidative stress and maintaining cellular health.

To understand the effect of varying BIL concentrations on oxygen generation, BIL content was adjusted from 0% to 6% (w/v), and the resulting oxygen concentration was measured. The concentration increased from 2.03 ± 0.10 mg/L for 0% BIL to 7.93 ± 0.4 mg/L for 4% BIL, highlighting the dependency of oxygen production on BIL concentration (Fig. 2B(iv)). This trend demonstrates the tunability of the BioGel system for different biological applications, allowing precise control over oxygen delivery. The visualization of oxygen generation using a 2D sensor foil connected to a detection system powered by a DC supply at 1 V provides further insights into the dynamics of O2 synthesis (Fig. 2C). The images show the evolution of oxygen within the BioGel electrolyte over time, with the voltage alternately turned on and off. The clear increase in oxygen concentration during the ON periods and the decrease during the OFF periods validate the ability to dynamically control oxygen production. This dynamic control is crucial for mimicking the varying oxygen demands in different tissue types, enabling the development of more accurate in vitro models and improving the physiological relevance of tissue-engineered constructs.

The inclusion of CoP as an electrocatalyst further enhances the performance of the SSOT constructs. CoP, synthesized and characterized in our study (Supplementary Fig. S2), shows excellent electrochemical properties, including a strong OER peak at ~0.9 V (Supplementary Fig. S1C), high stability in charge-discharge cycles (Supplementary Fig. S1D), and high porosity as indicated by BET surface area measurements (217.9 m2/g) (Supplementary Fig. S1E, F)). The integration of CoP with BioGel provides an alternative electrocatalytic material that can work synergistically with the hydrogel to further improve oxygen generation and stability. CoP offers potential benefits, including reactive oxygen species detection and reduced risk of cytotoxicity, making it a viable and sustainable option for long-term biological applications56,57. These advancements make this platform capable of providing a stable, efficient, and controllable oxygen supply, essential for the survival, growth, and proliferation of cells in tissue engineering applications. The broader impact of this lies in its potential to address critical challenges in engineering 3D tissues of clinically relevant sizes by ensuring an adequate and controllable supply of oxygen, thus supporting cell viability and function.

Molecular dynamics insights into SSOT oxygen release function

Full atomistic MD simulations were conducted to elucidate the roles of BIL in oxygen generation and the properties of GelMA on the Pt surface. Experimental data indicated BIL’s enhancement of oxygen release, necessitating molecular-level insights. Polyethyleneglycol diacrylate (PEGDA) was used to validate the force fields due to the lack of experimental data on BIL. This involved inserting 100 polymer chains into a cubic box (10 × 10 × 10 nm3), followed by energy minimization, heating from 0 to 300 K using an NVT ensemble, and equilibration in NPT MD simulations at 300 K. The calculated density of 1.16 g/ml differed from the experimental values by only 3.57% (Supplementary Fig. S3), demonstrating the accuracy and reliability of the force field and MD protocols. The chemical structures of BIL and GelMA are shown in Fig. 3A. BIL cations contain three NMe3+ groups, resulting in nine positive charges. GelMA was modeled with Pro-Gly-HydroxyPro-Glu-Gly-Arg-Pro-Gly-Ala, functionalized by methacrylic acid (MA). BIL concentrations (0 to 20 wt% and 0 to 25 wt%) were combined with 7 and 20 wt% GelMA in a 10 × 10 × 12 nm3 box (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. S3).

A Proposed chemical structure for the BIL cation and its counterion (bitartrate), alongside the chemical structure of GelMA and an example of the simulation setup employed to analyze the properties of the BioGel on the [111] surface of platinum. B Computed radial distribution functions (RDFs) for the distribution of oxygen molecules on the platinum surface in the presence of GelMA at concentrations of 7 wt% and 20 wt%, respectively, in complexation with varying concentrations of the BIL. C Calculated interaction energies between O2 molecules and the platinum surface in the presence of BioGel with various GelMA-BIL mixtures, indicating potential changes in interaction strength with different BIL concentrations. D The calculated diffusion coefficients of oxygen molecules within the BioGel matrices containing 7 wt% and 20 wt% GelMA highlight the influence of GelMA concentration on the mobility of O2 molecules.

To investigate BioGel-oxygen interactions, 300 oxygen molecules were added around BioGel systems on the [111] Pt surface. The structures obtained after simulation indicated significant effects of BIL on the distribution of GelMA on the metal surface and its interactions with Pt (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5). BIL cations were mixed with GelMA, while bitartrate anions were adsorbed on the metal surface. Experimentally, BIL reduced polymer expansion from 33.6 ± 1.15 kPa for 7% GelMA to 24.3 ± 2.00 kPa for BioGel. Radius of gyration (Rg) values showed that low BIL concentrations (4–10 wt%) significantly reduced the Rg of GelMA, revealing decreased polymer flexibility and expansion. However, higher BIL concentrations (20–25 wt%) increased Rg due to repulsive interactions between monomers (Supplementary Fig. S5). The number of contacts between GelMA and the Pt surface indicated that BIL concentration affects interactions with the metal surface (Supplementary Fig. S5B). Increased BIL reduced GelMA affinity to the surface. Hydrogen bond (H-bond) interactions between GelMA and water molecules decreased in the presence of BIL, suggesting competition between water and BIL for GelMA interaction. BIL altered GelMA’s internal H-bonds and dynamical properties (Supplementary Fig. S6A). Interaction energies showed GelMA had a higher affinity for Pt than BIL, with BIL reducing the number of contacts (Supplementary Fig. S6B).

Radial distribution function (RDF) analysis showed that BIL affects cation distribution around GelMA, with peak intensities decreasing as BIL concentration increased (Supplementary Fig. S7A). Water molecules showed greater interaction with BIL than GelMA. Higher BIL concentrations increased water molecule probability around GelMA, enhancing water absorption (Supplementary Fig. S7B). RDFs for GelMA and the cation with Pt showed that these compounds lie about 3.2 Å from the surface, with GelMA having higher interaction intensities. Increased BIL concentration reduced RDF peak intensity for GelMA, confirming BIL’s impact on GelMA’s solvation shell (Supplementary Fig. S8A). MD simulations of BioGel-oxygen interactions revealed that BIL facilitates oxygen release by reducing surface affinity for oxygen molecules (Supplementary Fig. S7B). RDF peaks showed oxygen molecules at 2.9 Å from Pt, with increased BIL reducing O2 interaction with the surface (Fig. 3B). Interaction energy calculations showed a linear correlation with BIL concentration, reducing O2-surface interaction energy (Fig. 3C). Higher BIL concentrations reduced O2 diffusion, enhancing oxygen release by reducing solubility and diffusivity, aligning with experimental observations (Fig. 3D). Overall, 8 wt% BIL with 7 wt% GelMA and 5 wt% BIL with 20 wt% GelMA had the maximum effects on O2-GelMA interactions, reducing interactions by about 65% and 35%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S8B). RDFs for oxygen distribution around the cation (BIL) showed greater interactions with BIL backbone atoms compared to GelMA, confirming BIL’s role in facilitating oxygen release (Supplementary Fig. S9). These findings provide molecular-level insights essential for optimizing the SSOT platform for efficient and sustained oxygen delivery in tissue engineering applications.

Biocompatibility assessment of SSOT technology in vitro and in vivo

The development of functional tissue constructs in vitro is constrained by challenges in scaling tissue size and ensuring vascularization within large scaffolds. Vascular networks are crucial for delivering nutrients and oxygen, which are regulated by oxygen concentration during cell culture12,29. Effective neovascularization requires controlled oxygen delivery to sustain cell viability in fabricated scaffolds. To assess oxygen generation and cell proliferation with the SSOT technology, constructs of 0.1 cm and 0.5 cm thicknesses were evaluated under normoxic, hypoxic (5% O2), and anoxic (1% O2) conditions (Fig. 4A–D). Oxygen deficiency can lead to inflammation, infection, reduced treatment efficacy, tissue necrosis, and implant failure. SSOTs demonstrated sufficient oxygen release in vitro, alleviating anoxia-induced cell death and supporting metabolic needs.

In vitro Functional evaluation of cell growth within the hydrogels with and without the SSOT technology at Day 14 via F-Actin/DAPI fluorescence assay and Live/Dead assay considering MSCs, HUVECs, and HDFs under normoxic, hypoxic (5% O2), and anoxic (1% O2) conditions for A 0.1 cm and B 0.5 cm constructs. Scale bar = 200 μm. Quantification of metabolic activity, relative fluorescence units (RFU) via PrestoBlue assay, ATP content, and DAPI-stained cell nuclei for C 0.1 cm constructs and D 0.5 cm constructs. E The total amounts of secreted VEGF and DNA were quantified and used to determine the VEGF/DNA ratio of hMSC-encapsulated SSOT constructs cultured under normoxic, hypoxic, and anoxic conditions. F In vivo biocompatibility analysis with and without SSOT technology via Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), Masson’s Trichrome (TRI), Human Nuclear Antigen (HNA)/C-reactive Protein (CRP), CD31/DAPI, and TUNEL/DAPI assays. Scale bar = 200 μm. Data represent means ± SEM (n = 4) with statistical significance indicated by P values from two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (ns–no significance, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

Implantable SSOT constructs (BioGel, CoP electrodes) were evaluated with Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), and human dermal fibroblasts (HDF). Cell viability, proliferation, and metabolic activity assays were conducted on days 1, 4, 7, and 14 under various oxygen conditions. MSC counts per mm2 in normoxia were 1020 ± 105 on Day 4, compared to 815 ± 35 under hypoxia and 585 ± 40 under anoxia. With SSOT, cell counts increased to 945 ± 55 and 1005 ± 96 under hypoxia and anoxia, respectively. HUVEC counts increased to 1065 ± 105 from 930 ± 40 under hypoxia with SSOT. On Day 14, MSC counts in normoxia were 1236 ± 188, compared to 633 ± 166 under hypoxia and 335 ± 166 under anoxia. SSOT increased counts to 940 ± 90 and 1020 ± 125 under hypoxia and anoxia, respectively. HDF and HUVEC counts also showed significant increases with SSOT (Fig. 4A–D).

Metabolic activity assays showed increased relative fluorescence units (RFU) with the SSOT setup under hypoxic conditions: MSC (5575 ± 86 vs. 1674 ± 427), HDF (5917 ± 505 vs. 3185 ± 315), and HUVEC (48807 ± 190 vs. 2310 ± 375). Increasing tissue thickness from 0.1 cm to 0.5 cm improved cell survival and proliferation due to enhanced electrocatalysis at the electrode-electrolyte junction (Fig. 4C, D). After 14 days in culture, MSC viability increased from 42 ± 5% to 74 ± 4% under anoxia with SSOT, HDF viability from 46 ± 3% to 79 ± 4%, and HUVEC viability from 38.6 ± 7.5% to 78 ± 5%. Metabolic activity and ATP measurements indicated healthier cell proliferation under anoxia with SSOT: MSC (1920 ± 108 RFU to 5181 ± 157.8 RFU), HDF (2470 ± 286 RFU to 6975 ± 199 RFU), and HUVEC (2183 ± 388 RFU to 5589 ± 498 RFU) (Fig. 4C, D). Approximately 80% of cells in SSOT formulations continued to proliferate over 14 days under anoxic conditions, demonstrating SSOT’s efficacy in preventing anoxia-induced cell death. The VEGF/DNA ratio in hMSC-encapsulated SSOT constructs indicated increased VEGF secretion and DNA content with SSOT under normoxic, hypoxic, and anoxic conditions (Fig. 4E), showing enhanced angiogenic potential and cell proliferation.

Digital images of 3D-printed BioGel, CoP, and SSOT are shown in Supplementary Fig. S10A. The ALLEVI bioprinter enabled extrusion-based printing of the BioGel electrolyte and CoP electrode using a blend of laponite, gelatin, and CoP. SSOT’s potential for cell survival and proliferation was evaluated over 7 days (Supplementary Fig. S10B–E). The viability of cells seeded on the construct was 98.0 ± 1.0%, comparable to 98.3 ± 0.5% for controls, indicating minimal cytotoxicity. Metabolic activity increased throughout the culture, demonstrating SSOT’s biocompatibility.

In vivo biocompatibility is essential for implantable biomedical devices to avoid adverse inflammatory responses9. SSOT interaction with native tissue was assessed on days 4 and 28, indicating constant degradation (Supplementary Fig. S11). CD68 staining on day 28 showed low macrophage infiltration, suggesting considerable SSOT degradation. H&E staining and immunohistochemistry indicated macrophage presence on day 4 due to surgery-induced inflammation. Further histological analysis via H&E staining showed good integration with surrounding tissues and minimal inflammatory response (Fig. 4F). Masson’s Trichrome staining confirmed collagen deposition and tissue remodeling around the SSOT implants, indicative of tissue regeneration. Immunohistochemical analysis using human nuclear antigen and c-reactive protein markers demonstrated minimal immune response, while CD31/DAPI staining indicated enhanced vascularization in the SSOT-treated tissues. TUNEL/DAPI assays showed reduced apoptosis with SSOT technology compared to controls, further highlighting the biocompatibility and efficacy of this platform in promoting cell survival and tissue integration.

We also evaluated the SSOT’s cytocompatibility using Pt electrodes, which revealed remarkable cell survival and distribution within the BioGel matrix and at the BioGel–Pt electrode interface (Supplementary Fig. S12). Additionally, we evaluated cell survival under hypoxia within SSOT made of neutral electrodes, such as carbon, which demonstrated poor cell survival due to inadequate oxygen availability (Supplementary Fig. S13).

These results underscore this platform’s efficacy in generating oxygen to alleviate hypoxic stress, supporting cell viability, proliferation, and metabolic activity in both in vitro and in vivo settings. This is crucial for successful implementation in regenerating defective tissues, highlighting the potential of SSOT technology to enhance the survival and functionality of engineered tissue constructs in hypoxic conditions. Additionally, the biocompatibility and degradation profile of SSOTs make them suitable candidates for long-term implantation without adverse immune responses. Future studies could explore the integration of SSOT technology with various tissue engineering scaffolds to further optimize their therapeutic potential.

Therapeutic efficacy of SSOT technology in diabetic wound healing

The potential application of SSOT technology in the treatment of chronic and non-chronic diabetic wounds was assessed through a series of in vivo studies. An SSOT patch fitted with composite CoP electrodes was tested for non-chronic diabetic wound healing (Supplementary Fig. S14). A 6 mm excisional wound was created in 12-week-old diabetic mice, and the SSOT was connected to a battery for constant voltage. Wound-healing progression was monitored every other day for 18 days (Supplementary Fig. S14A, B). Controls with no SSOT patch and negative controls consisting of SSOT patch with no battery connection were also observed. Oxygen imaging using the VisiSens A1 sensor confirmed oxygen generation by the SSOT connected to a 1.3 V battery (Supplementary Fig. S14C). Quantified results showed a significant reduction in wound size in SSOT-treated wounds with and without battery connection compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. S14D). By day 18, SSOT-treated wounds with battery connection showed substantial wound size reduction, confirming the efficacy of SSOT’s oxygen generation function. Histological analysis via H&E and Masson trichrome staining revealed tissue regeneration in the SSOT group, while tissue remained unhealed in the control group (Supplementary Fig. S14E). Histological analysis using Masson’s Trichrome and Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) staining revealed marked differences in wound healing progression between the SSOT/ON-treated and control groups. In the control group, Masson’s Trichrome staining demonstrated dense and disorganized collagen deposition indicative of fibrotic tissue remodeling, while H&E staining revealed an incomplete and thin epithelial layer, suggesting impaired re-epithelialization. In contrast, SSOT/ON-treated wounds exhibited more organized and uniformly distributed collagen fibers, with reduced fibrotic features and increased dermal cellularity. Notably, the H&E-stained sections from the SSOT/ON group showed a well-defined and continuous stratified epithelium, indicative of successful epidermal regeneration. Together, these findings suggest that SSOT/ON treatment significantly enhances wound repair by promoting structured ECM remodeling, reducing fibrotic scarring, and facilitating re-epithelialization, thereby supporting more functional and complete tissue regeneration compared to the untreated control. Additionally, quantification of the explanted hydrogel/tissue area calculation showing better hydrogel/tissue integration in the SSOT group is shown in Supplementary Fig. S15.

Diabetic wounds often suffer from high oxidative stress and prolonged inflammation, often exacerbated by infections with antibiotic-resistant biofilm-forming pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa58,59. These bacteria contribute to delayed healing and complicate treatment due to their robust biofilm formation and resistance to conventional antibiotics. A significant component of the BioGel electrolyte is choline BIL, which confers antimicrobial properties44, crucial for healing chronic wounds populated with antibiotic-resistant biofilm-forming bacteria. Phosphonium and cholinium-based BILs reduce bacterial adherence by as much as four orders of magnitude, aiding the healing process40. This effect could explain the partial healing observed in wounds treated with non-battery-powered SSOT patches in Supplementary Fig. S14, where no oxygen generation occurred. Based on the promising results with non-chronic diabetic wounds, we next explored the efficacy of the SSOT patch in the treatment of chronic wounds in diabetic mice.

Chronic diabetic wounds pose a significant medical challenge due to hypoxia-mediated delays in healing, resulting from suppressed production of angiogenic factors and impaired vascularization, tissue repair, and regeneration. Approximately 6.5 million people in the United States suffer from chronic wounds, costing the healthcare system $25 billion annually60. The increasing prevalence of type II diabetes and associated comorbidities exacerbates these issues. Wound-healing involves hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling, all of which require adequate oxygenation. Oxygen is critical for these cellular functions and is also involved in leukocyte bactericidal activity against aerobic Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms58. Insufficient oxygen supply can lead to prolonged inflammation and increased risk of infection, which severely impedes the healing process.

To address these challenges, the oxygen-generating function of the SSOT was tested on chronic wounds in an advanced human-relevant diabetic mouse model61,62. Briefly, to model chronic wounds, we used db/db−/− diabetic mice and induced high OS levels in the wound tissue immediately after injury. This was achieved through a single treatment with inhibitors targeting the antioxidant enzyme catalase (using 3-amino-1,2,4-trizole (ATZ)) and glutathione peroxidase (using mercaptosuccinic acid (MSA))—two key regulators of oxidative balance during wound healing. As a result, these wounds exhibited high OS levels, developed biofilm naturally, and became fully chronic, remaining open throughout the mice’s lifetime. This novel model closely resembles many features of diabetic chronic wounds in humans. For comparison, untreated 7 mm full-thickness cutaneous wounds in db/db−/− mice typically heal within 20–25 days, whereas the same wounds in C57BL/6 mice close within 11–12 days. However, when catalase and glutathione peroxidase inhibitors were applied at the time of injury, the wound microenvironment changed, allowing biofilm-forming bacteria from the skin microbiota to establish biofilms. Notably, in our diabetic mouse model, these bacteria were not artificially introduced post-wounding but were already present in the skin microbiota. The high OS levels in the wound created favorable conditions for biofilm formation, which intensified over time. In the weeks following wounding, biofilm accumulation increased significantly, leading to persistent wound infection and prolonged wound opening—often lasting for weeks.

The controlled and stable release of oxygen facilitated by the SSOT technology accelerates wound closure. Chronic wounds often experience decreased angiogenesis, which limits the supply of nutrients and oxygen to the wound63,64. The SSOT circuit, complete with BioGel hydrogel and Pt electrodes, facilitated a steady generation and release of oxygen when connected to a battery (Fig. 5A). Electrochemical characterization of Pt electrodes was performed using cyclic voltammetry, with the curve showing a current response to a potential sweep, with a peak around 0.9 V indicating the OER (Supplementary Fig. S16). The BioGel hydrogel by itself has been shown to facilitate chronic wound healing and hair regeneration65. Wounds treated with the battery-powered SSOT patch showed accelerated healing, characterized by wound closure and hair growth around the wound site, indicative of healing (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Fig. S17). Quantitative wound area measurements showed that battery-powered SSOT patches significantly reduced wound size after Day 15 (Fig. 5C). SSOT treatment accelerated wound closure, with controlled oxygen generation being a key factor. As expected, in the control group without SSOT treatment, the wound size kept increasing with time and did not show signs of healing. To further assess the quality of healing, the wound tissue was collected and embedded in OCT and cryosectioned, followed by H&E and Masson’s trichrome staining (Supplementary Fig. S18). The sections showed re-epithelialization on the surface with a uniform layer of granulation tissue formation underneath the epithelial layer, confirming proper wound closure. Additionally, organized dense collagen deposition in Masson’s trichrome sections further indicated regenerative wound healing. These results demonstrate SSOT technology’s potential to accelerate chronic wound healing by providing controlled oxygen delivery for tissue repair and regeneration.

A Schematic representation of the treatment regimen involving BioGel electrolyte and platinum electrodes connected to a battery source for sustained oxygen generation. B Timeline of wound progression from Day 0 to Day 33 in both SSOT/ON (Mouse 1 in C SSOT/ON plot) and control groups, demonstrating faster recovery with the SSOT platform. Scale bars are 1 cm. C Quantitative analysis of wound closure using ImageJ for area measurements from serial wound images. The graphs plot normalized wound area over time post-wounding, comparing outcomes with and without SSOT. Wounds treated with SSOT show significantly faster closure within 33 days compared to the lack of healing in the control group. P-value was determined by Student’s t test (n = 4, ***p < 0.001).

The therapeutic efficacy of the SSOT technology in diabetic wound healing is underscored by its ability to mitigate anoxia-induced stress, a major obstacle in effective wound repair66. Anoxia impedes the wound-healing process by suppressing angiogenic factors, disrupting cellular functions, and exacerbating inflammation. By delivering controlled bursts of oxygen, the SSOT alleviates the nutrient-starved environment while avoiding excessive oxygenation and the resultant oxidative stress. This sustained oxygen delivery has been shown to promote angiogenesis, collagen deposition, and re-epithelialization, which are essential for granulation tissue formation and wound closure67,68. Furthermore, the incorporation of choline BIL provides antimicrobial properties, reducing bacterial load and biofilm formation, common complications in diabetic wounds. The SSOT platform thus offers a multifaceted therapeutic approach to managing chronic wounds, effectively addressing the critical barriers to successful healing.

Conclusion

The development of self-oxygenating scaffolds marks a transformative advancement in addressing the pervasive challenge of hypoxia in tissue-engineered constructs. This study introduces an electrolysis-driven oxygenation method for developing thick, clinically relevant human tissue constructs that significantly enhance cell survival and angiogenesis. SSOT constructs composed of BioGel and Pt electrodes maintained high levels of cell viability, proliferation, and metabolic activity under normoxic, hypoxic, and anoxic conditions, effectively mitigating anoxia-induced cell death. The biocompatible and stable CoP electrodes, combined with the 3D-printable BioGel electrolyte, provided a controlled and prolonged oxygen release, essential for sustaining the metabolic needs of engineered tissues. In vivo studies confirmed the clinical potential of the SSOT, showing effective integration with native tissues with minimal inflammatory response. Notably, battery-powered SSOT patches accelerated wound closure in chronic and non-chronic diabetic wounds. The SSOT platform holds significant potential for the development of advanced wound care solutions and functional 3D tissue models. This technology could also be adapted for use in bioreactors and microfluidic systems to support cell growth in vitro. Future research should focus on optimizing SSOT technology for diverse applications, integrating real-time monitoring and feedback control systems, and exploring advanced fabrication techniques.

Methods

Synthesis and characterization of the electrode and electrolyte

BioGel synthesis involves combining GelMA and choline acrylate BIL. The BIL was synthesized following our previously established procedure42. Briefly, choline bitartrate and acrylic acid were reacted in an equimolar ratio for five hours at 50 °C, and the synthesized BIL was then purified using a rotary evaporator. The system was maintained at a pH of 2–2.2 to enhance the acid-catalyzed esterification reaction. The synthesized BIL was conjugated to the backbone of the GelMA. To synthesize GelMA, a 10% (w/v) gelatin solution and eight milliliters of methacrylic anhydride were reacted for three hours. The unreacted anhydride was then dialyzed out for five days. The resultant product was frozen and lyophilized. The BioGel electrolyte was made using 7% (w/v) GelMA and 4% (w/v) BIL with 0.5% (w/v) LAP as a photoinitiator. This mixture was photopolymerized using visible light (405 nm for 60 seconds).

The CoP catalyst was prepared as follows: a 0.86 M solution of cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Millipore Sigma) and a 0.57 M solution of sodium phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) were prepared. These solutions were mixed and stirred for 2 h. The mixture was then transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and heated at 200 °C in an oven. After 6 h, the resulting solid cobalt phosphate was vacuum filtered and washed three times each with ethanol and deionized water. To characterize the physical properties of the synthesized CoP catalyst, EDAX-SEM was performed for elemental analysis, showing the various percentages of the elements present in the synthesized catalyst. Furthermore, to fabricate the electrode for the SSOT, CoP was mixed with Laponite and GelMA blend at a ratio of 9% (w/v) Laponite, 7% (w/v) CoP, and 1% (w/v) GelMA to optimize the rheological properties for printing. In addition to using the Cobalt Phosphate-Laponite-GelMA blend as the electrode (denoted here as CoP), several SSOT structures for both in vivo and in vitro studies were made using Pt electrodes, particularly for ease of in vivo application. The figures detailing the results are presented accordingly, and the electrode used is mentioned throughout the manuscript.

Physical and chemical characterization of the BioGel electrolyte

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to evaluate the porosity of the BioGel electrolyte and the synthesized CoP electrode material. Samples were prepared using PDMS molds and then freeze-dried. The synthesized CoP was crushed into fine particles for the test. Both the electrode and BioGel electrolyte were coated with gold before imaging. Mechanical properties of the BioGel were estimated using samples prepared with PDMS molds. Compression and tensile tests were carried out on an Instron mechanical tester equipped with a 100 N load cell. Compression tests were conducted by compressing the samples, while tensile tests used tensile grips, both at a constant rate of 1 mm/min until failure. The sample surface area and length were used to calculate compressive/tensile stress and compressive/tensile strain from the load-extension plots. Finally, the compressive/tensile moduli were calculated from the slope of the linear region of the stress-strain curves. For the swelling and degradation studies, BioGel samples were fabricated as previously described and incubated in DPBS at 37 °C. Degradation was monitored over two weeks, with samples being lyophilized and weighed at 1, 7, and 14 days. The swelling ratio was assessed by freeze-drying and weighing the samples before incubation, followed by measurements at 4, 8, and 24 h post-incubation.

To simulate proteolytic degradation under physiologically relevant conditions, hydrogel samples were exposed to collagenase type II (from Clostridium histolyticum, Sigma-Aldrich) at final concentrations of 10 U mL⁻¹ or 50 U mL⁻¹ in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, Gibco). Two formulations were assessed: GelMA hydrogels (20 wt% porcine GelMA, 0.25 wt% LAP) and BioGel hydrogels (20 wt% porcine GelMA, 15 wt% acrylated choline bitartrate, 0.25 wt% LAP). Hydrogels were synthesized in well plates and photocrosslinked using 405 nm light as previously described. Following gelation, they were freeze-dried for 24 h, and the initial dry mass (Wᵢ) was recorded before transferring to 48-well plates. Next, 400 μL of collagenase solution was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C. At predetermined time points (12 h, 1 d, 3 d, and 7 d), the collagenase solution was removed, and the hydrogels were rinsed twice with DI water. Samples were then refrozen, lyophilized, and their dry weights (Wt) were recorded. The degradation ratio (%) at each time point was calculated using the following equation:

Electrochemical characterization of the electrolyte, electrode, and fabricated SSOT

Electrochemical characterization of the BioGel electrolyte, CoP electrode, and the fabricated SSOT was conducted using cyclic voltammetry, charge/discharge tests, and impedance spectroscopy analysis with a CHI 660E potentiostat (CH Instruments, Inc.). The electrochemical properties of the BioGel electrolyte were studied by polymerizing the gel into a cylindrical shape and employing a glassy carbon electrode in a three-electrode system. For the CoP electrode material, the CoP catalyst was mixed with PVDF and cast on the working electrode. The BioGel was evaluated as an electrolyte with a glassy carbon electrode, while the CoP-based electrode was tested using a PBS electrolyte. The SSOT’s electrochemical properties were assessed by coating a working electrode with CoP and using BioGel as the electrolyte. The edge of the fabricated SSOT device was attached to the working electrode with adhesive conductive copper tape. Ag/AgCl was used as the reference electrode, and gold served as the standard electrode. For EIS, a frequency range of 105–0.05 Hz, an amplitude of 10 mV, and a scan rate of 10–200 mV/s were used. Cyclic voltammetry was performed at a scan rate of 10 mV/s between −1 V and 1 V, along with galvanostatic charge-discharge at 0.1 A/cm3.

Oxygen generation measurement in the SSOT

Oxygen production in the SSOT platform was measured using two approaches: a probe sensor for quantitative measurements and a sensor foil for qualitative assessments. Quantitative estimation employed the SevenGo Duo® pro™ SG98 pH/Ion/Optical Dissolved Oxygen Meter with a probe sensor from METTLER TOLEDO® under hypoxic conditions (1% O2). Pt electrodes were secured to the bottom of a vial with carbon tape and connected to a DC power source. The BioGel electrolyte solution was added, and the vial was sealed with a custom-made airtight cap. The probe sensor was embedded in the hydrogel and polymerized with 405 nm light for 1 min. After stabilization, a constant DC voltage of 1 V was applied, and oxygen concentration (mg/L) was recorded at designated time points. For qualitative evaluation, the VisiSens A1 system with a Detector Unit (DU01) and a planar fluorescent sensor foil was used under hypoxic conditions (1% O2). The sensor foil was affixed to a microscope slide with Pt electrodes attached on each side and connected to a power source. BioGel solution was directly applied to the sensor, covered with Tegaderm, and polymerized with 405 nm light for 1 min. The setup was placed on the detector unit, a DC voltage of 1 V was applied, and oxygen profiles were visualized in real-time using VisiSens AnalytiCal 1 software, monitoring temporal oxygen gradients at designated time points.

Computational simulation studies of the SSOT

Molecular dynamics simulations were applied to investigate the properties of the BioGel on the Pt surface and the role of the synthesized BIL on the oxygen evolution process from the molecular viewpoint. Since there is no available experimental data about the properties of the synthesized BIL to compare them with the calculated molecular features by the MD simulation methods in the first step, the PEGDA was selected as the reference polymer to check the validity of the employed force fields to reproduce the properties of the corresponding polymers.

At the first step of the MD simulation, to check the force fields’ ability to reproduce the PEGDA’s properties, 100 chains of the polymer composing 20 monomers were randomly inserted in a cubic box (10 × 10 × 10 nm3). Then 100,000 steps of energy minimization were applied to reduce the unfavorable short contacts. In the next step, the temperature of the system was increased by employing an NVT ensemble from 0 to 300 K during 1000 ps with 1 fs time step. The obtained structure from the heating step was equilibrated during three NPT MD simulations, including 50 ns (300 K), 10 ns (350 K), and 10 ns (300 K) using 1 fs time step. Finally, 150 ns (2 fs time step) NPT MD (300 K and 1 bar) simulations were performed on the equilibrated structure as the product step. The calculated density value for the corresponding polymer from the MD simulation is in good agreement with the experimental value, which confirms that the employed force field and MD protocols can reproduce the PEGDA properties.

Each branch of the BIL has three NMe3+ groups, therefore, each cation of the BIL has 9 positive charges. The chemical structure of the GelMA was modeled based on the reported structures in the literature69. The sequence of the GelMA is composed of Pro-Gly-HydroxyPro-Glu-Gly-Arg-Pro-Gly-Ala, in which the hydroxyl and amine groups of residues 3 and 6 were functionalized by MA, respectively, according to the reported structure by Zhu and coworkers69. In the next step, to create a model of the BioGel on the Pt surface, which acts as the electrode, different concentrations of BIL ranging from 0 to 20 wt% and 0 to 25 wt% in the presence of 7 and 20 wt% of GelMA were inserted into a rectangular box (10 × 10 × 12 nm3), respectively. The number of GelMA and BIL molecules in each simulation is reported in Table S1. Then all the structures were minimized through 100,000 steps of energy minimization as the initial step of the MD simulation for the BioGel on the Pt surface. In the heating step, the temperature of the systems increased from 0 to 300 K during 20 ns (1 fs time step) in an NVT ensemble. Then the obtained structures were equilibrated during 20 ns (1 fs time step) in an NPT ensemble (1 bar and 300 K). Finally, 100 ns NPT MD simulations were performed with a 2 fs time step on the obtained structures from the equilibration step.

As the final step of the MD simulations to analyze the interactions between BioGel and oxygen molecules and the role of BioGel on the oxygen distribution in the system, 300 oxygen molecules were added around the BioGel systems on the [111] surface of Pt, randomly. In other words, the obtained structures of the BioGel on the electrode surface were used as the initial configuration in this step. The minimization, heating (by applying a typical force constant of 2.5 kcal mol−1 A−2 for the solute structures), and equilibration steps are the same as the reported condition for the BioGel in the absence of O2 molecules. Then, 300 ns NPT MD simulations were performed as the product step on the equilibrated structures to analyze the effects of the BioGel on O2 distribution in the system. All the simulations were repeated three times independently. Another separate MD simulation was performed in the absence of the BioGel for a system including water, electrode, and O2 molecules to elucidate the oxygen distribution in pure water.

The FF14SB70, General Amber Force Field parameters71, and reported parameters by Heinz and coworkers72 were applied for the GelMA, BIL, (PEGDA and oxygen molecules), and Pt, respectively. The atomic charges of the PEGDA, BIL, and GelMA were calculated by the CHelpG method at the M06-2X/6-31 + G(d) level of theory using Gaussian 16 computational software package73. The periodic boundary conditions were applied in all directions for the studied systems. The isotropic Berendsen method and Langevin thermostat were applied in the NPT simulations to control the pressure and temperature with a relaxation time of 1 ps and a collision frequency of 1 ps−1 for pressure and temperature, respectively74,75. 12 Å direct cut-off was applied to calculate the long-range electrostatic interactions using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method. The SHAKE constraints were used for all bonds involving hydrogen atoms76. All the above MD simulations were performed using the Amber 22 software package77.

Biocompatibility of the SSOT in vitro

HUVEC, HDF, and MSC were cultured both on the surface of and encapsulated within BioGel hydrogels to fabricate the SSOT. These constructs were placed in 12-well plates with 1 ml of the respective medium, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The 3D cell cultures were maintained for 14 days in a cell culture incubator. Cell viability with BioGel hydrogels was assessed using a Live/Dead viability kit, where live cells swere tained green and dead cells were stained red. Metabolic activity was evaluated on days 1, 4, and 7 using PrestoBlue assay (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cell proliferation was analyzed by fluorescent staining of actin filaments and cell nuclei, as previously described42. Both CoP and Pt electrodes were used for these in vitro studies.

Functional evaluation of the fabricated SSOT constructs in vitro

To evaluate the performance of the SSOT, HUVECs, HDFs, and MSCs at a density of 2 × 104 cells/scaffold were encapsulated in BioGel hydrogels with 7% (w/v) GelMA and 4% (w/v) choline acrylate BIL. After encapsulation, the BioGel electrolyte was set by polymerizing the GelMA and choline acrylate BIL between Pt or printed CoP electrodes (9% (w/v) Laponite, 7% (w/v) CoP, and 1% (w/v) GelMA) spaced 5 mm apart. The setup was maintained under sterile conditions, polymerized using visible light, and cultured in the respective media according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A regulated low-voltage DC power supply (B & K Precision SE) of 1 V was connected to the electrodes in the culture, under hypoxic conditions in a tri-gas incubator with 5% and 1% oxygen levels. Control setups without the power supply were also included. The voltage in the culture was monitored at timed intervals to ensure stability throughout the experiment. Cell media was changed every 48 h. The function of the SSOT was evaluated by measuring cellular metabolic activity, cell viability, cell proliferation, and ATP levels.

Biocompatibility of the SSOT in vivo

Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Rowan University. Male Wistar rats, weighing 200–250 grams, were purchased from Charles River (Boston, MA, USA). Anesthesia was induced with 5% isoflurane and maintained at 2–2.5%, with subcutaneous buprenorphine administration. Skin incisions were made on the posterior side to implant the fabricated SSOTs (in the form of 5 × 5 mm discs). The skin incisions were closed using wound clips, and the animals were allowed to recover. Implanted samples were explanted along with the surrounding tissue on days 4, 14, and 28. The samples were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and immunofluorescent staining using an anti-CD68 primary antibody and an Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody. Images were acquired using an AxioObserver Z1 microscope from Zeiss.

Subcutaneous implantation of fabricated SSOT constructs for vascularization studies

To study the vascularization of the fabricated constructs, nude rats were acclimated for at least three days before any manipulation. Male rats between 200–250 g and at least 10–12 weeks of age were used. Anesthesia was performed using 5% isoflurane. While monitoring the status of the rat, Buprenorphine SR (sustained-release, 1.2–1.5 mg/Kg) or meloxicam SR (sustained-release, 2.5–5 mg/Kg) was injected subcutaneously 30 min before surgery to minimize animal discomfort during and after surgery. The skin was disinfected under a BSL2 laminar flow cabinet using 70% isopropyl alcohol followed by 2% chlorhexidine scrub, three times, for a total of 6 scrubbings, to provide adequate and long-lasting disinfection with a final iodine paint prep to ensure sterility. The mediodorsal skin of systemically anesthetized rats was incised by 1 cm in length, and a small lateral subcutaneous pocket was bluntly prepared. SSOT with encapsulated hMSCs were subcutaneously implanted in the rats, and skin incisions were closed with wound clips. The entire setup (SSOT and battery) was further secured to the animal usinga Tegaderm dressing, wrapped around the chest and back. At the endpoint (7 days), rats were euthanized, and the scar tissue along with the implanted setup was collected for immunofluorescence and histological analysis.

In vivo diabetic non-chronic wound healing study

Animal experiments were approved by the IACUC at Rowan University. For the study, diabetic B6.BKSD-Leprdb/J mice were ordered from Jax and acclimated for three days before any manipulation. Hyperglycemia was assessed and recorded before surgery with a standard glucometer (Bayer) using a drop of blood drawn from nicking the tail with a sterile needle. Blood glucose levels average around 250 mg/dL but can be as high as 400 mg/dL. Mice with blood glucose levels lower than 200 mg/dL were excluded from the study. Briefly, shaving was performed under light isoflurane anesthesia. Buprenorphine SR (sustained-release, 1.2–1.5 mg/Kg) or meloxicam SR (sustained-release, 2.5–5 mg/Kg) was injected subcutaneously 30 min before surgery to minimize animal discomfort during and after surgery. Anesthesia was performed using 5% isoflurane and maintained at 3% isoflurane during surgery.

The skin was disinfected by using 70% isopropyl alcohol followed by 2% chlorhexidine scrub, three times, for a total of 6 scrubbings, to provide adequate and long-lasting disinfection with a final iodine paint prep under BSL2 laminar flow cabinet to ensure sterility, wounds were created in the dorsal skin by punching through both sides of a fold of skin with a 6 mm biopsy punch. Subsequently, two silicone splints (Grace Bio-Labs) were attached to the skin, a standard step to ensure the wounds do not close by contraction. For the mice group without treatment, only Tegaderm was used to wrap the wounds around the chest and back. For the other groups (SSOT/ON and SSOT/OFF), SSOT was applied to the damage inside the ring and connected to a coin battery (6 mm) glued to the silicon rings. The whole setup (rings, SSOT, and the battery) was further secured to the animal using Tegaderm dressing, wrapping around the chest and back. At the endpoint (full wound closure or 21 days), mice were euthanized using CO2 and cervical dislocation. Wound/scar tissue was collected for further histological assessment.

In vivo diabetic chronic wound healing study

To evaluate the efficacy of SSOT treatment on a diabetic mouse chronic wound model, experiments were conducted following the UCR IACUC protocol (Protocol 11 2023). Diabetic heterozygous B6.BKSD-Leprdb/J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and bred to produce db/db−/− mice. These mice are phenotypically obese and diabetic. They were used at 20–24 weeks of age with weights ranging from 40–80 g, averaging around 60 g. Blood glucose levels average ~250 mg/dL but can be as high as 400 mg/dL. Mice with blood glucose levels lower than 200 mg/dL were excluded from the study. A day before surgery, the mice were shaved and treated with depilatory lotion (Nair) to ensure smooth skin for firm adhesion of the transparent Tegaderm dressing. On the day of surgery, buprenex (0.05 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally (IP) 30 min prior to minimize discomfort. Subsequently, ATZ) in sterile PBS was injected IP at 1 g/kg, 20 min before surgery. Anesthesia was performed using 5% isoflurane for 1–2 min at a flow rate of 2–3.5 L/min and maintained with 2–3% isoflurane. This was confirmed by the lack of response to a strong toe pinch. The surgical site was cleaned with 70% ethanol. Care was taken to not wipe with 70% ethanol excessively, to minimize the risk of killing the bacteria present on the skin. The success of the chronic wound model relies on the bacterial microbiome that resides on the skin for the subsequent initiation and development of chronic wounds upon treatment with inhibitors of antioxidant enzymes. Therefore, conventional pre-surgical sterilization of the wounding site is contra-indicated. A 7 mm full-thickness circular wound was created using a disposable biopsy punch, which was covered with a transparent Tegaderm dressing (6 cm × 3.5 cm), and MSA in sterile PBS was applied topically at 150 mg/kg. Post-surgery buprenex injections were administered as needed.

In the control group, no treatment was applied, and the wound was secured with Tegaderm. In the ‘SSOT/ON’ group, BioGel hydrogel and Pt electrodes (ThermoFisher Scientific) were connected to a 1.4 V size 312 button cell battery (Duracell) and secured with Tegaderm. The battery was placed and secured near the mouse’s neck to avoid contact with the wound. A 405 nm blue light was used to polymerize the BioGel electrolyte for 60 seconds. The setup was replaced every 3–4 days to ensure consistent activity. The SSOT implants (both the hydrogel and the electrodes) were periodically replaced during the duration of the treatment and eventually removed once the wound had healed in a fashion similar to traditional wound dressing. Pictures were taken each time the dressing was replaced. At the study endpoint (full wound closure or 33 days), mice were euthanized using CO2, and wound tissues were extracted. Wound areas were calculated from digital photographs using ImageJ and plotted as a function of treatment duration. The extracted wound tissues were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin & eosin and Masson’s trichrome stains for histological analysis.

Cryosectioning and histology

The tissue collected was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by quenching with 0.1 M glycine. The tissue was washed with PBS for 15 min between each step. The tissue was then treated with 30% sucrose, followed by freezing in OCT. The tissue was then sectioned at 10 µm in a Leica CM 1950 cryostat. The sections were stained with H&E and examined under a Nikon Microphot-FXA fluorescence microscope at ×4 magnification.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate unless otherwise stated. Statistical evaluation using two-tailed Student’s t test or ANOVA with post hoc tests as applicable was performed on IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 29). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation or standard error of the mean as applicable. Statistical levels of significance were ns—non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript and its Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Neef, N. Limitations of pathology and animal models. In Pathology of Toxicologists 157–183 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2017).

Doncheva, N. T. et al. Human pathways in animal models: possibilities and limitations. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 1859–1871 (2021).

Hansen, A. et al. Development of a drug screening platform based on engineered heart tissue. Circ. Res. 107, 35–44 (2010).

Hwang, D. G., Choi, Y. & Jang, J. 3D bioprinting-based vascularized tissue models mimicking tissue-specific architecture and pathophysiology for in vitro studies. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 685507 (2021).

Tourovskaia, A., Fauver, M., Kramer, G., Simonson, S. & Neumann, T. Tissue-engineered microenvironment systems for modeling human vasculature. Exp. Biol. Med. 239, 1264–1271 (2014).

Kim, J. et al. Manufactured tissue-to-tissue barrier chip for modeling the human blood-brain barrier and regulation of cellular trafficking. Lab Chip 23, 2990–3001 (2023).

Saidi, R. F. & Hejazii Kenari, S. K. Challenges of organ shortage for transplantation: solutions and opportunities. Int J. Organ Transpl. Med. 5, 87–96 (2014).

Roberts, M. B. & Fishman, J. A. Immunosuppressive agents and infectious risk in transplantation: managing the “net state of immunosuppression. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73, e1302–e1317 (2021).

Edgar, L. et al. Regenerative medicine, organ bioengineering and transplantation. Br. J. Surg. 107, 793–800 (2020).

Organ Donation Statistics | organdonor.gov. https://www.organdonor.gov/learn/organ-donation-statistics.

Zaidi, M., Fu, F., Cojocari, D., McKee, T. D. & Wouters, B. G. Quantitative visualization of hypoxia and proliferation gradients within histological tissue sections. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7, 397 (2019).

Fraisl, P., Mazzone, M., Schmidt, T. & Carmeliet, P. Regulation of angiogenesis by oxygen and metabolism. Dev. Cell 16, 167–179 (2009).

Santore, M. T., McClintock, D. S., Lee, V. Y., Budinger, G. R. S. & Chandel, N. S. Anoxia-induced apoptosis occurs through a mitochondria-dependent pathway in lung epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 282, L727–L734 (2002).

Farris, A. L., Rindone, A. N. & Grayson, W. L. Oxygen delivering biomaterials for tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 4, 3422–3432 (2016).

Poncelet, D., Leung, R., Centomo, L. & Neufeld, R. J. Microencapsulation of silicone oils within polyamide—polyethylenimine membranes as oxygen carriers for bioreactor oxygenation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 57, 253–263 (1993).

Chin, K., Khattak, S. F., Bhatia, S. R. & Roberts, S. C. Hydrogel-perfluorocarbon composite scaffold promotes oxygen transport to immobilized cells. Biotechnol. Prog. 24, 358–366 (2008).

Charbe, N. B. et al. A new era in oxygen therapeutics? From perfluorocarbon systems to haemoglobin-based oxygen carriers. Blood Rev. 54, 100927 (2022).

Agarwal, T. et al. Oxygen releasing materials: towards addressing the hypoxia-related issues in tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 122, 111896 (2021).

Moses, S. R., Adorno, J. J., Palmer, A. F. & Song, J. W. Vessel-on-a-chip models for studying microvascular physiology, transport, and function in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 320, C92–C105 (2021).

Dellaquila, A., Le Bao, C., Letourneur, D. & Simon-Yarza, T. In vitro strategies to vascularize 3D physiologically relevant models. Adv. Sci. 8, 2100798 (2021).

Melchels, F. P. W. et al. Effects of the architecture of tissue engineering scaffolds on cell seeding and culturing. Acta Biomater. 6, 4208–4217 (2010).

Malda, J. et al. The effect of PEGT/PBT scaffold architecture on oxygen gradients in tissue engineered cartilaginous constructs. Biomaterials 25, 5773–5780 (2004).

Farzin, A. et al. Self-oxygenation of tissues orchestrates full-thickness vascularization of living implants. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2100850 (2021).

Baker, C. J., Deahl, K., Domek, J. & Orlandi, E. W. Scavenging of H2O2 and production of oxygen by horseradish peroxidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys, 382, 232–237 (2000).

Zhong, D., Du, Z. & Zhou, M. Algae: a natural active material for biomedical applications. VIEW 2, 20200189 (2021).

Augustine, R. et al. Oxygen-generating scaffolds: one step closer to the clinical translation of tissue engineered products. Chem. Eng. J. 455, 140783 (2023).

Willemen, N. G. A. et al. Oxygen-releasing biomaterials: current challenges and future applications. Trends Biotechnol. 39, 1144–1159 (2021).

Farris, A. L. et al. 3D-printed oxygen-releasing scaffolds improve bone regeneration in mice. Biomaterials 280, 121318 (2022).

Oh, S. H., Ward, C. L., Atala, A., Yoo, J. J. & Harrison, B. S. Oxygen generating scaffolds for enhancing engineered tissue survival. Biomaterials 30, 757–762 (2009).

Zoneff, E. et al. Controlled oxygen delivery to power tissue regeneration. Nat. Commun. 15, 4361 (2024).

Huang, L. et al. Hydrogen production via electrolysis of wastewater. Nanomaterials 14, 567 (2024).

Lagadec, M. F. & Grimaud, A. Water electrolysers with closed and open electrochemical systems. Nat. Mater. 19, 1140–1150 (2020).

Wu, H. et al. In situ electrochemical oxygen generation with an immunoisolation device. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 875, 105–125 (1999).

Scianmarello, N. et al. Oxygen generation by electrolysis to treat retinal ischemia. In 2016 IEEE 29th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS) 399–402 https://doi.org/10.1109/MEMSYS.2016.7421645. (2016).

Noshadi, I. Biocompatible oxygen gas generating devices for tissue engineering. US Patient, USPTO 11389583 (2022).

Lee, I. et al. Electrocatalytic on-site oxygenation for transplanted cell-based-therapies. Nat. Commun. 14, 7019 (2023).

Vioux, A., Viau, L., Volland, S. & Le Bideau, J. Use of ionic liquids in sol-gel; ionogels and applications. C. R. Chim. 13, 242–255 (2010).

Krishnadoss, V. et al. In situ 3D printing of implantable energy storage devices. Chem. Eng. J. 409, 128213 (2021).

Krishnadoss, V. et al. Bioionic liquid conjugation as universal approach to engineer hemostatic bioadhesives. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 38373–38384 (2019).

Kanjilal, B. et al. Bioionic liquids: enabling a paradigm shift toward advanced and smart biomedical applications. Adv. Intell. Syst. 5, 2200306 (2023).

Noshadi, I. et al. Engineering biodegradable and biocompatible bio-ionic liquid conjugated hydrogels with tunable conductivity and mechanical properties. Sci. Rep. 7, 4345 (2017).

Krishnadoss, V. et al. Programmable bio-ionic liquid functionalized hydrogels for in situ 3D bioprinting of electronics at the tissue interface. Mater. Today Adv. 17, 100352 (2023).

Wu, J. & Yang, H. Platinum-based oxygen reduction electrocatalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1848–1857 (2013).

Siopa, F. et al. Choline-based ionic liquids: improvement of antimicrobial activity. ChemistrySelect 1, 5909–5916 (2016).

Shamsuri, A. A. & Jamil, S. N. A. M. Application of quaternary ammonium compounds as compatibilizers for polymer blends and polymer composites—a concise review. Appl. Sci. 11, 3167 (2021).