Abstract

The rapid expansion of the Internet of Things (IoT) has significantly raised concerns over secure identification and authentication of IoT devices. While physical unclonable function (PUF)-based anticounterfeiting cryptography shows promise, implementing multi-factor authentication (MFA) system with resource-constrained PUF device remains a significant challenge. Here, we demonstrate a multidimensional-encoded optical PUF fabricated with multi-color quantum dots (mQDs), resilient to machine learning attacks, for use in anticounterfeiting MFA. Randomly distributed mQDs in a periodic nanostructure fabricated via nanoimprint lithography generate spatially chaotic, unpredictable multiple security keys when ultraviolet (UV) light is only illuminated. Photoluminescence measurements revealed irregular mQD emission, where disordered distribution-induced Förster resonant energy transfer produces unpredictable color patterns. Our PUF-induced multiple keys were validated through advanced PUF metrics like uniformity, uniqueness, correlation factor, entropy, and even resilience to machine learning attack. We further demonstrate efficient implementation of a cryptography protocol with MFA system for IoT applications using mQDs-based optical PUFs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advances of Internet of Things (IoT) technology have greatly enhanced the convenience in our daily lives. Particularly, IoT applications are rapidly evolving and becoming increasingly significant in modern society, with projections indicating that the number of IoT devices will exceed 75 billion by 20251. These IoT devices collect and transmit a wide range of data, from personal information to critical industrial data, through connected networks. However, these devices and their networks are highly susceptible to hacking and cyber attacks. Furthermore, the proliferation of counterfeit integrated circuits within IoT devices poses significant challenges for secure electronics supply chains. The existing software-oriented security alone has proven insufficient against sophisticated attacks utilizing quantum computing and machine learning (ML), prompting the exploration of hardware cryptography solutions2,3.

Traditional hardware cryptographic solutions typically rely on non-volatile memory to store security keys used in cryptographic algorithms. However, these stored keys are secure only for the device’s lifetime and remain vulnerable to side-channel attacks4. To overcome these limitations, Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) have emerged as promising hardware cryptographic primitives5,6,7. PUFs are innovative techniques that generate unforgeable authentication information by leveraging the physical characteristics of hardware. By harnessing the unique randomness that naturally occurs during manufacturing, PUFs provide a unique identifier nearly impossible to replicate, making them highly effective in preventing duplication or breaches of IoT devices. PUF device produces the security keys by generating responses to given challenges: an input (challenge) prompts a unique output (response) based on the device’s unique physical characteristics. Unlike traditional security methods relying on static secrets, PUFs generate dynamic responses tied to the hardware’s unique traits. This dynamic nature makes it exceedingly difficult for an attacker to replicate the exact physical conditions needed to produce the same PUF response, thus ensuring that PUFs possess a unique and unforgeable identity.

Extensive efforts have focused on implementing PUFs in various forms. State-of-the-art PUF largely utilizes unique and irregular electrical signals from SRAM and NAND flash fabricated through conventional complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) semiconductor processes8,9,10. Additionally, recent advancements have introduced PUF technologies that utilize optical signals from materials such as optical fibers11, metallic nanoparticles12,13,14, and fluorescent particles15, as well as stochastic resistive switching from memristor16,17,18,19 and frequency fluctuations in ring oscillator circuits20. In addition, emerging materials beyond Si-based PUF technologies, such as graphene21,22, carbon nanotubes23,24, molybdenum disulfide25 and polymers26, have been investigated for their unique mechanical, structural, and electrical properties. Among these, optical PUFs have gained significant attention thanks to their high output complexity with high entropy and resilience against erratic IoT power supplies27. With the expansion of AI technologies and the energy-intensive operations of data centers processing vast amounts of data, low-power security devices are increasingly essential.

To date, most optical PUFs rely on one-dimensional responses in which a single PUF device generates a security key, including micropattern imaging28, Raman scattering12,29, fluorescent lifespan30, and fluorescent intensity at each pixel15. These one-dimensionally encoded optical PUFs limit encoding capacity and pose a challenge for the multi-factor authentication (MFA) systems, which require at least two authentication protocols. Thus, optical PUFs that can generate multiple keys within a single pixel have been intensively investigated, which includes fluorescent protein31, gap-enhanced nanoparticles (NPs)12, plasmonic NPs32, organic molecules33, and nanorods34. However, many of these optical PUFs suffer from a signal cross-talk problem and low information entropy due to the use of heterogeneous materials in anticounterfeiting solutions and their limited optical responses within a pixel22,28,35,36. Recent efforts with Si metasurface and erbium-doped Si quantum dots (QD) can realize multidimensionally-encoded optical PUF have introduced multidimensional encoding capabilities36, but these approaches are still limited by encoding capacity using identical QD in restricted areas. In addition to overcoming physical constraints, optical PUFs must exhibit strong resistance to ML attacks, wherein adversaries collect challenge–response pairs to construct predictive models capable of replicating the PUF device. These attacks leverage subtle correlations in optical outputs—such as luminescence intensity patterns, color distributions, and spatial characteristics—to infer mathematical mappings between challenges and responses within the PUF device. Such vulnerabilities undermine the inherent unpredictability and physical unclonability of optical PUFs, posing a critical threat to the security of systems. Therefore, there is essential to develop multidimensionally encoded optical PUF with high entropy, encoding capacity, and resilience to ML attack, which are crucial requirements for anticounterfeiting in IoT devices.

In this work, we propose a multidimensionally encoded optical PUF based on multi-color quantum dots (mQDs) utilizing the Förster resonant energy transfer (FRET) effect, achieved by mixing and coating two different colored QD materials onto nanopatterned films. The mQD-coated films exhibit luminescence upon ultraviolet (UV) exposure. By converting the red and green color values (0–255 per pixel) into binary, we demonstrated the ability to form a large encoded capacity with high entropy in a compact area. This approach eliminates the need for additional optical analysis equipment to generate security keys. Our mQDs-based multiple keys were validated through advanced PUF metrics like uniformity, uniqueness, correlation factor, entropy, and even resilience to ML attack. Furthermore, our PUF device can be fabricated on the transparent and flexible substrate platform, enabling transparent and flexible film PUF application nearly without power consumption. Finally, we demonstrate that the mQDs-based PUF device can be implemented for an MFA cryptography system, leveraging dual color codes-based multiple security keys.

Results

Fabrication of mQDs-based multidimensionally encoded optical PUFs

The game of Go, as exemplified by AlphaGo, is a survival competition in which players alternately place black and white stones on a board. As shown in Fig. 1a, the board is composed of 19 horizontal and 19 vertical lines, resulting in a total of 361 positions for placing stones. Furthermore, the number of possible configurations for alternating placements of black and white stones is an astounding 361! (approximately 2.6 × 10845). Therefore, applying the probability value (p) to the entropy calculation of Eq. (1) indicates the potential for achieving a very high level of entropy. This implies substantial data scalability in bit units.

a AlphaGo inspired PUF, b High entropy FRET-based PUF concept, c nanoimprint Lithography process for replicable nano-patterned films and QD spin coating process, d SEM images before and after QD coating on nanopattern films and luminescence variation based on the concentration ratio and arrangement of two QD particles under UV illumination, e Principle of FRET as a Jablonski diagram, f Color-shifting effect: fluorescence excitation and emission spectra of a FRET donor–acceptor pair (As the FRET efficiency increases, the emission of the donor decreases (Green ↓), while the emission of the acceptor increases (Red ↑). The gray patterned region highlights the overlap between the donor emission spectrum and the absorption spectrum of the acceptor).

We are inspired to emulate the uncertainty inherent in the game of Go by mixing two distinct QD nanoparticles (QDs) (Fig. 1b). This process will lead to the formation of irregular ratios and arrangements of the two different QDs at the nanoscale, resulting in observable color changes. These color variations are leveraged as random entropy sources for PUF devices. Initially, we fabricated a periodic nanoscale hole pattern through the nanoimprinting lithography process. This nanostructure is designed to embed QDs within a well-like structure with sufficient depth of about 150 nm, as shown in Fig. S1. QDs coated on an unpatterned flat surface form uneven layers with insufficient dispersion, resulting in reduced luminescence intensity. In contrast, a nanopatterned surface facilitates a more regular arrangement of the QDs, enabling pixelation for color signaling, as evidenced by the PL intensity comparison in Fig. 2b and the emission images and corresponding color values in Fig. S2.

a Formation of nanoscale color value distribution (PUF’s response) in 6-inch nano-patterned films coated with QDs based on FRET phenomenon, b comparison of PL spectra between non-patterned and nano-patterned films, c calculation of variations in FRET efficiency with distance R between two color QDs (for enhancing the randomness characteristics of PUF), d PL spectra before and after two color QD mixing, e time-resolved PL decay after two color QD mixing.

Figure 1c illustrates the nanoimprinting process and the subsequent QD coating procedure on a 6-inch substrate. A master mold with nanoscale diameter hole patterns was coated with nanoimprinting resin, followed by the application of a polyethylene terephthalate (PET) film, which was evenly coated using a roller. To cure the resin, UV exposure was conducted for 90 s, after which the master mold was separated from the cured film, and a secondary post-curing step was performed. The resulting cured first film exhibits a pattern that is the inverse of the master mold. By repeating the aforementioned process, multiple second films with the hole pattern can be replicated from the first film. The replication process via nanoimprinting lithography enables the cost-effective fabrication of nanostructure-based optical PUF. Finally, to enhance the adhesion between the film and QDs during coating, an O₂ plasma treatment was performed to make the surface hydrophilic. We utilized red and green CdSe/ZnS QDs with a core/shell structure to realize mQDs-based optical PUF on the nanopatterned film. The sizes of the red and green QDs were confirmed via zeta potential measurements to be approximately 10 ± 2 nm and 8 ± 2 nm, respectively (Fig. S3). A 1:1 ratio solution of red and green QDs was mixed using a magnetic stirrer and then uniformly dispersed onto the nanopatterned film via spin coating.

Figure 1d shows top-view and cross-sectional scanning electron microscope images for nanopatterned film before and after mQDs coating. The diameter of the formed nano-pattern holes is approximately 250 nm, with a depth of 500 nm and a pitch of 250 nm between the holes. It was observed that the mQDs are uniformly distributed within the wells of the nanopatterned film, achieving pixel-like arrangements with a thickness of around 150 nm. The irregular distribution of mQDs, composed of red and green QDs, within the nanopatterned film results in variations in red and green luminescence. The pixelated nano-well structure allows the QD particles to be densely packed within narrow nanoscale regions, enabling mutual luminescent influence.

Figure 1e presents a Jablonski diagram illustrating the mechanism of energy transfer through FRET, influenced by the arrangement of two types of fluorescent QDs (donor and acceptor). When the donor fluorophore absorbs a photon, it transitions from the ground state (S0) to the excited state (S1), subsequently emitting fluorescence as it returns to the ground state. In FRET, instead of emitting fluorescence, the energy from the donor is transferred and absorbed by the acceptor fluorophore, which then gets excited and subsequently emits fluorescence. In other words, the FRET phenomenon occurs when the donor emits light at a specific wavelength, which is subsequently absorbed by a nearby acceptor, resulting in energy transfer37, as shown in Fig. 1f. Consequently, the variation in FRET efficiency due to the random arrangements of red and green QDs can induce a wide spectrum of color-shifting effects, as illustrated in Fig. 1b.

Optical properties of mQDs coated on nanopatterned film by FRET effect

We analyzed the optical properties of a 6-inch nano-hole patterned film coated with a mixture of red QDs and green QDs in equal volume ratios after exposing it to UV light. As shown in Fig. 2a, each pixel area within this 6-inch film exhibits different emission colors. This variation is attributed to the differences in volume ratios of the green QDs and red QDs coated in each pixel. Moreover, even when coated at the same volume ratio, significant deviations in color values within a single pixel can be observed, depending on the ratios and arrangement of the green QDs and red QDs within the nano-hole patterned structure. To validate the potential for forming PUF security keys using nanoscale color variations, we performed various optical analyses on the mQD-coated films we fabricated.

We initially conducted an optical analysis of a nano-patterned film coated with a solution in which red and green QDs were mixed in a 1:1 ratio to verify the reliability and improvement of dispersion characteristics of the color values corresponding to the response values for PUF devices. Figure 2b presents the results of PL spectra analysis conducted on the films with and without nano-patterns. The nano-patterned film exhibited higher PL intensity compared to the non-patterned film, as the QD particles were coated in a relatively larger volume within the nano-hole patterned structures. Notably, when the diameter of the hole pattern was increased from 200 to 400 nm, the PL intensity increased by approximately 1.5 times, attributed to the greater QD volume. Importantly, even though the concentrations of red and green QDs were mixed in equal ratios, the PL intensity value in the red wavelength range is twice that of the green wavelength range. This can be attributed to the red color-shifting phenomenon, which is a result of the FRET effect discussed earlier. The FRET phenomenon follows the theory proposed by Förster in 194837,38,39. Initially, the energy transfer efficiency in a typical scenario is described by Eq. (2).

Here, R represents the distance between the donor (green QD) and the acceptor (red QD), while R0 is the Förster distance, which is the distance at which the FRET efficiency (E) is 50%. This indicates that the FRET phenomenon is significantly dependent on the distance between the donor and acceptor. However, when the two colors of QDs are arranged within the wells of the nano-patterned structure, energy transfer occurs not only between a single donor and acceptor, but also across various configurations of distances between donors and acceptors, as shown in Fig. 2a. This implies that multiple coupling effects can arise, potentially enhancing the energy transfer efficiency. Therefore, we reflected the modified transfer efficiency equation (Eq. (3)) to calculate the variations in energy transfer efficiency that can occur when green QDs and red QDs are arranged on the nano-patterned structure. This suggests an additional increase in energy transfer efficiency relative to n, the ratio of donors (Green QDs) to acceptors (Red QDs).

Figure 2c shows the simulation results of the FRET efficiency based on the fixed R0 value (4.2 nm) calculated for the QDs we used, taking into account the distance R between the two colors of QD particles. The R0 value was experimentally determined from the donor (green QD) lifetime and intensity changes in the presence of the acceptor (red QD), from which the FRET efficiency was derived and converted to R0 using the standard Förster relation. We then incorporated the calculated R0/R values for the red and green QD particles40,41,42. Considering both scenarios—where the two colors of QDs are fully aggregated and in contact, as well as when they form empty spaces and do not contact—the FRET efficiency can be estimated to range from 0% to approximately 30%, depending on the specific configurations. Therefore, the color values, or response signals, for each pixel may be relatively irregular and unpredictable, influenced not only by the concentration ratios of the two colors of QD particles but also by the FRET effects arising from their mutual arrangement. To verify the existence of FRET effects in the two colors of QDs coated on the nano-patterned film, we examined their optical properties in comparison with the simulation results.

Figure 2d shows the PL spectra measured from pure green QDs (donor), pure red QDs (acceptor), and the 1:1 mixture of QDs coated nano-patterned films. A decrease in PL intensity was observed in the green QDs (donor) and simultaneous increase in the red QDs (acceptor) in the mixed QDs. To further confirm the existence of FRET, time-resolved PL measurements were conducted. Figure 2e displays the PL decay profiles for the green QDs, red QDs, and the mixed QDs on nano-patterned films. Notably, compared to pure QDs, the PL lifetimes of the green QDs decrease, while those of the red QDs increase in the mixed case. This behavior is attributed to the FRET effect, wherein photo-generated carriers in the donors have an additional pathway to transfer energy to the acceptors, resulting in longer emission lifetimes for the donors. Thus, these results are consistent with the expected behavior of FRET.

Additionally, the nano-patterned films can enhance the reliability of optical properties and to increase the variance of color values corresponding to the response values of PUF devices. In the non-patterned film, insufficient coating thickness leads to a narrow distribution of color values within the pixels. Moreover, excessive coating of the red QDs causes saturation of the color code values up to 255, resulting in a similar reduction in distribution values, as shown in Fig. S2. Within a single pixel, the presence of defects due to poor coating results in a scattered distribution of color codes. In contrast, when a sufficient amount of QDs is densely arranged on the nano-patterned films, a relatively high distribution value is observed, with a more uniform range of color value formation across the pixels in the film.

PUF performance of mQDs-based multidimensionally encoded optical PUFs

Figure 3a illustrates the methodology for generating multiple security keys in our optical PUF devices based on FRET characteristics of bicolor mQDs. QDs exhibit quantized energy levels due to the quantum confinement effect, allowing them to emit specific luminescence values based on particle size dependent energy bandgap variations. To generate multiple security keys, UV light serves as the challenge, producing a security key response. This UV light excites the mQD-coated nanopatterned film, resulting in luminescence. The resulting image of the luminescent film is captured using a charge-coupled device camera with a resolution of approximately 5 megapixels under darkroom conditions (Fig. S4). The luminescence is generated by a stabilized UV LED light source, and the relative angle and position between the light source, the mQD-coated nanopatterned film, and the CCD camera are fixed during measurement. The term “darkroom conditions” refers to an environment where all external light is completely blocked to ensure accurate and noise-free image acquisition. For image analysis, we developed a customized software tool using Microsoft Visual Studio 2015 MFC and employed Mvtec’s Halcon library for image processing detailed further in the Methods section and Supplementary Note 1. The analysis process of the captured images involves several steps: pixel setting for the data processing area, extraction of red/green color values, binary classification of the data, and formation of a binary image. The data processing area is designated by dividing the acquired image into microscale pixels. At this stage, the bit capacity of the PUF can be further expanded by adjusting the pixel area size. Increasing the pixel area from micrometers to millimeters or centimeters could potentially increase data bit values by several thousand-fold. Next, red and green channels are separated to extract color values ranging from 0 to 255, with each color channel converted to grayscale for independent processing. Histograms for color values of each channel are generated, and binarization is performed using a pre-established threshold to produce response bits. This process generates separate red and green security keys from a single image. Further details on our computer vision processing software are provided in the supplementary materials. Notably, unlike previous optical PUF devices that required separate optical analysis equipment, our mQDs-based optical PUF operates independently of such equipment, enabling practical application.

To evaluate the anticounterfeiting performance, we analyzed key figure-of-merits for PUF application, including entropy, uniformity, uniqueness, and correlation coefficient (CC). Each PUF consists of a square image with 30\(\,\times \,\)30 pixels. Uniformity is defined by the ratio of “0” and “1” bits in the bit stream, ideally achieving 50% to maximize randomness. It is calculated as follows:

where \(n\) is the length of the security key and \({r}_{i}\) is the number of a bit “1”. The uniformity of mQDs-based optical PUF is 50.46% and 50.49% for red and green security keys, respectively (Fig. 3b, c), indicating minimal bias in the generated security key. Next, we calculated the entropy (\(E\)), representing the system’s randomness:

where p is the uniformity of PUF. Red and green security keys exhibit entropy value near the ideal value of 1, indicating sufficient stochasticity (Fig. S5). Uniqueness, another critical metric, quantifies the distinctiveness of one PUF compared to others. It is evaluated using the inter-Hamming distance (HD) and CC. The inter-HD is calculated as follows:

where \(k\) is the number of security keys and \(n\) is the length of the security key, and \({r}_{i}\) and \({r}_{j}\) represent the response of security keys \(i\) and \(j\), respectively. If the HD between a pair of security keys is too long or too short, one security key can be deciphered using the knowledge of the other PUF, indicating that the ideal value of inter-HD is 50%. The inter-HD for red and green security keys is a near-ideal value of 49.90% and 49.86%, respectively. The CC measures the linear correlation between two security keys and is calculated as follows:

where \(x\) and \(r\) are two variables with means of \(\bar{x}\) and \(\bar{r}\), respectively. Figure 3f, g show CC values of 0.01 and 0.00 for red and green security keys, closely approaching the ideal value of 0. These ideal PUF performances benefit from FRET effect-induced coupling strengths between mQD, as discussed in Fig. 2. Additionally, the bit capacity of mQDs-based optical PUF can be expanded by increasing the pixel area size in the captured same image (Fig. 3h). The entropy, uniformity, uniqueness, and CC for mQDs-based optical PUFs with increased bit capacity maintain ideal PUF performances (Fig. S6). These results confirm that mQDs-based multidimensionally encoded optical PUFs with large bit capacity are highly suitable for applications in authentication, anticounterfeiting, and security key generation for secure IoT devices and systems. Furthermore, the reproducibility, long-term stability, and environmental robustness of the security keys were evaluated. The repeated measurements on the same PUF device consistently maintained very low error rates (Fig. S5), and more than 150 devices exhibited stable entropy and uniformity across multiple repeated measurements (Fig. S6). In addition, the mQDs-based PUFs maintained stable optical responses under varying temperature and humidity conditions, confirming their capability to operate reliably in practical IoT environments (Fig. S7). These results demonstrate that the mQDs-based PUF can reliably generate secure keys even over prolonged use and diverse environmental conditions. However, several factors can introduce variability in optical measurements, including temperature fluctuations, slight variations in UV illumination intensity, detector noise, and minor mechanical misalignments during repeated measurements. These variations could lead to inconsistent bit generation from the same physical PUF. For practical deployment, future work will address measurement variations through error correction and fuzzy extractors to ensure reliable key regeneration.

Machine learning attack resilience

The advancement of ML has raised concerns about potential attacks on IoT devices, especially those using cloud network-based security systems. The ML attacks based on regression models have demonstrated effective in various PUF systems, including Si43 and 2D materials-based PUFs22. In particular, the regression model based on Fourier series as supervised method can efficiently predict security keys by forecasting future values based on historical data, often outperforming reinforcement learning or evolutionary models. Their effectiveness lies in the direct modeling of the mathematical model of PUF, whereas other models like support vector machines and neural networks build their own intrinsic models22. These typically involve collecting challenge-response (security key) pairs from a PUF device through physical access or protocol eavesdropping, then training predictive models to capture the specific input-output mapping within the same device rather than attempting cross-device prediction43. Although each PUF has distinct physical characteristics, regression models can still uncover subtle statistical patterns, enabling high prediction accuracy. This highlights the critical importance of developing PUF systems resistant to ML attacks for secure IoT applications. The Fourier regression-based estimation function is represented as the following:

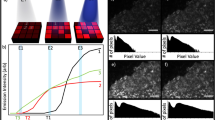

where NF is the order of the Fourier series and \({x}_{i}\) represent the \(i\) th value in the security key. As NF increases, the Fourier series model can improve spectral resolution by including more temrs in the estimation function. Therefore, we utilize the Fourier regression model to assess the ML attack resilience of our optical PUF devices. In this ML attack test, we created the 30-bit-long security keys by dividing each row in the 30 \(\times\) 30 binary image, generating a large dataset for improved ML model accuracy. Figure 4a illustrates the methodology for predicting the 30-bit-long security keys using the Fourier regression-based estimation function \(f\left({x}_{i}\right)\left(i=1,\,2,\ldots ,\,30\right)\). During training process, 720 experimental security keys were utilized as the training dataset, while the remaining 180 security keys were used as the test dataset. For prediction, values generated by the trained estimation function at specific NF were binarized against a threshold of 0.5, assigning “0” or “1” based on whether they were smaller or larger than 0.5, respectively. Figure 4b shows representative training and prediction results for red security keys with NF of 1, 3, and 11. Note that the accuracy of estimation function improves as NF increases, indicating that well-trained Fourier regression models are suitable for evaluating ML attack resilience. However, the predicting values generated from the estimation functions shows low accuracy, highlighting the inherent unpredictability of our optical PUFs.

a Schematic of predicting security keys generated from mQDs-based optical PUFs using Fourier regression model. b Representative training and test results for various Fourier order (NF). Statistical analysis of test accuracy and heatmap of training/test accuracy for various NF using c, e red and d, f green security keys, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 4c, d, the average prediction accuracies for red and green security keys were 51.11% and 53.88%, respectively, close to the ideal 50%. The heat maps in Fig. 4e, f exhibit the training and prediction accuracy with various NF = 1, 3,…, 9, 11 for red and green security keys, respectively. While training accuracy improves with increasing NF, prediction accuracy consistently hovers around 50%, unaffected by NF in both red and security green keys. The training accuary is improved by increasing NF, indicating that NF values larger than 7 and 11 are required for accurate ML attack test for red and green security keys, respectively. However, note that the prediction accuracy remains consistently around 50%, unaffected by NF for both red and green security keys. Therefore, the mQDs-based multidimensionally encoded optical PUFs demonstrate strong resilience to ML attacks.

Protocol for anticounterfeiting and authentication with mQDs-based PUF

Conventional anticounterfeiting and identification mostly rely on physical tags with optical image on currency or Europay, MasterCard, and Visa chip in credit card. However, these are susceptible to image duplication-based counterfeiting and side-channel attacks. Optical PUF-based tags can present a promising solution for anti-counterfeiting applications, because they can implement MFA through color-specific security key generation. Our mQDs-based optical PUF can be fabricated on flexible and transparent substrates, because mQD-coated nanostructure films show outstanding transparent features in the visible light range (Fig. S8) and allow large bit capacity within densely integrated areas. When irradiated with UV light, mQD-based optical PUFs emit distinctive luminescent colors based on the QD mixing ratio.

Our mQDs-based PUF system can operate through a three-phase protocol, as illustrated in Fig. 5a: (1) Manufacturing and registration phase, (2) Authentication phase, (3) Verification phase. In the manufacturing and registration phase, the manufacturer fabricates mQD-based optical PUFs with random spatial distributions and registers them in the authentication system. Upon UV illumination, each PUF emits a unique photoluminescent pattern determined by its QD composition and spatial layout. This UV challenge yields two optical response channels—red and green—from which binary security keys are extracted (as detailed in Fig. 3). The green channel data is used to generate a private key, securely assigned to the user, while the red channel forms the public key and corresponding color signature. These public identifiers are registered in the central authentication server during the initial enrollment phase.

a Schematic illustration for anticounterfeiting and authentication using mQDs-based PUF. The overall schematic depicts the process in which products with anti-counterfeiting or authentication tags are issued along with private keys to the user. Authentication is conducted by comparing the private keys embedded in the products with the corresponding public keys registered in the data center. b Schematic illustration of the image encryption and decryption process using secure keys generated from robust optical PUFs. The process demonstrates the use of mQDs-based optical PUFs for secure image encryption and decryption, enhancing data security for information communication.

In the authentication phase, the PUF is illuminated with standardized UV light to induce its characteristic optical response. The red private key is extracted from the PUF’s luminescent response. This private key is then transmitted to the authentication server as part of the verification attempt. For the verification process, the server retrieves the corresponding public key and color signature for the claimed device from its database. It then verifies the received private key by checking its consistency with the stored public key. Authentication is granted only when the private key correctly corresponds to the registered public key. If a counterfeit device is used, it will fail to regenerate the valid private key due to the unclonable nature of the PUF, enabling robust detection. This protocol leverages the deterministic yet unclonable optical response of the PUF to generate a consistent key pair, with the public key serving as a registered reference and the private key as a reproducible authentication factor, providing robust security for IoT devices.

Furthermore, our mQDs-based optical PUF can support secure information communication in IoT systems. Conventional information encryption and communication between two parties rely on the security keys stored in a data center, leaving them vulnerable to side-channel and ML attacks. We propose a secure communication protocol using our mQDs-based multidimensionally encoded optical PUF for encryption and decryption. We utilized the Vernam algorithm44 to encrypt and decrypt an image data using the secure keys generated from the mQDs-based optical PUF. In this protocol, the multi-security key is generated through the bit exclusive OR operation of red and green security keys. As illustrated in Fig. 5b, the 50\(0\,\times \,\)500 pixel image was efficiently encrypted into a cipher using the security key generated from 90 images, rendering the original image unrecognizable. To restore the encrypted image, four security keys are investigated: (1) multi-security key, (2) red key, (3) green key, and (4) key generated from ML. Note that only the correct multi-key restored the original image, while attempts with other keys (red, green, or ML-generated) failed. This demonstrates that unauthorized hackers would be unable to access the encrypted image, highlighting the robust security potential of optical PUFs in IoT applications. Moreover, the generated cryptographic keys can be securely transmitted through RFID or NFC modules to external devices or servers, providing a practical data communication channel for authentication and key exchange in IoT environments.

Discussion

We have demonstrated advanced mQDs-based optical PUFs with large bit capacity. The multiple keys generated from red and green mQDs emissions offer high entropy due to FRET effect-induced interactions between donor and acceptor QDs. Our mQDs-based optical PUFs exhibit ideal security features, including uniformity, uniqueness, entropy, and CC, as well as strong ML attack resilience, confirming the unpredictability of their security keys. With these features and inherent unclonability, our optical PUFs are well-suited for identification and anti-counterfeiting applications. Compared to the characteristics of other PUF devices, our study also demonstrated excellent uniformity, uniqueness, resistance to ML attacks, and reliability (Table S1). Furthermore, unlike existing electronics-based PUFs, our optical PUFs can significantly reduce power consumption by generating security keys solely through UV exposure and can be fabricated for versatile form factors as flexible and wearable devices. We believe that continued research can expand our study to large-scale PUF system applications, where the superior density, robustness, and multi-mode security of mQDs provide a compelling advantage. Therefore, the optical PUFs can facilitate secure identification and authentication for IoT devices and systems, advancing the era of hyperconnectivity.

Method section

Materials

Core/shell CdSe/ZnS QD were synthesized by Uniam Co., Ltd. The red-emitting CdSe core exhibited a diameter of 4 nm, with the total diameter, including the ZnS shell, measuring 10 ± 2 nm. The green-emitting CdSe core had a diameter of 3 nm, resulting in a total diameter of 8 ± 2 nm. Emission peaks were observed at 625 nm and 513 nm for the red and green QD, respectively. To facilitate the mixing and dispersion of the two QD types on film, a toluene suspension at a concentration of 10 mg/mL was prepared. The QDs used in our experiments were coated with oleic acid containing a carboxyl (–COOH) functional group. The length of the oleic acid ligand is approximately 2.0 nm, with a variation of ±0.3 nm. A nanohole pattern film was fabricated by replicating a master with a nanohole pattern onto a polyurethane-based UV resin, synthesized by combining OH and NCO monomers. For this purpose, the MINS-311RM UV resin from Minuta Co., Ltd. was utilized. The substrate used for resin patterning was a 0.1 T thick PET film.

Optical PUF fabrication

Before the fabrication of nano-hole patterned films, a master with a nano-hole pattern was subjected to ultrasonic cleaning in acetone and isopropyl alcohol (IPA) for 10 min. To eliminate any residual contaminants, deionized (DI) water rinsing was performed, followed by drying with a nitrogen gun. Subsequently, UV-curable resin was drop-cast onto the nano-hole patterned master, and a PET film was placed on top. A roller was used to ensure an even dispersion of the resin. After removing the resin-coated PET film from the master, the film underwent UV curing for 90 s, resulting in the production of a primary replicated film with nano-hole patterns. This process was repeated using the primary replicated film to fabricate secondary replicated films with the same nano-hole pattern. To prevent agglomeration of QD particles before coating, the film was treated with oxygen plasma for 1 min. A toluene suspension was used to mix red-emitting and green-emitting QDs in equal volume ratios, and magnetic stirring was employed to ensure a homogeneous solution and prevent particle aggregation. The QD mixed solution was then applied to the nano-hole patterned film using spin coating at 4000 RPM for 1 min. Finally, the QD-coated nano-hole patterned film was processed at 110 °C for 5 min using a heater to complete the fabrication process.

Characterization

The images of the nano-hole patterned films before and after the QD coating were analyzed using a focused ion beam. (FIB, Thermoscientific Co., Ltd, Helios 5 UX) In addition, this FIB images were used along with zeta potential measurements (ELSZ−1000, Otsuka Electronics Co., Ltd., Japan) to examine the morphology and size distribution of the QD particles on the film surface. PL spectra were measured using a UV–Vis Fourier transform near infrared fluorescence spectrometer (FS-2, Scinco Co., Ltd.) Transmittance measurements were conducted in the wavelength range of 400–700 nm for PET films with and without nano-patterns, as well as for QD-coated PET films with nano-patterns, using a UV–Vis spectrometer. (S-3100, Scinco Co., Ltd.)

Data processing

To utilize the emission color variance of UV-exposed QD-coated nanohole pattern films on a 6-inch scale as security keys in PUF devices, a camera and lighting tool setup was prepared. A Crevis Co., Ltd. MG-A500k-22 camera model was used, featuring a resolution of approximately 5 megapixels (2464 × 2056 pixels). The camera is equipped with a CMOS Pregius IMX 264 sensor, with each pixel measuring 3.45 μm × 3.45 μm. A CCTV lens from COMPUTAR Co., Ltd. (model M1614-VSW) was attached, providing a field of view of approximately 191 mm × 160 mm. This configuration yields a system resolution of 0.077821 mm × 0.077821 mm. The lighting system consists of a bar-type UV LED with a wavelength of 405 nm. For image processing and analysis, the Halcon image processing library by Mvtec Co., Ltd. was adopted. Within the 6-inch area of the QD-coated nanohole pattern film, the image processing region could be selected at scales ranging from micrometer-sized rectangular areas to larger desired dimensions. Additionally, the processing region could be divided into multiple rows and columns, allowing the generation of hundreds to thousands of security keys within the 6-inch film area. The selected image processing area was separated into Red, Green, and Blue channels using the decompose function. This operation resulted in three grayscale images, each corresponding to the individual color channels. Gray-scale values ranging from 0 to 255 for the Red and Green channels were then utilized to create a histogram. The median histogram value was determined as the threshold value, which was used to perform binary thresholding and generate binary codes.

Data availability

All data which support the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information, or available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Schiller, E. et al. Landscape of IoT security. Comput Sci. Rev. 44, 100467 (2022).

Zhang, J., Rajendran, S., Sun, Z., Woods, R. & Hanzo, L. Physical layer security for the internet of things: authentication and key generation. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 26, 92–98 (2019).

Beckmann, N. & Potkonjak, M. Hardware-based public-key cryptography with public physically unclonable functions. In Proc. 11th International Workshop on Information Hiding, IH’2009, Darmstadt, Germany, June 8−10, 2009 Revised Selected Papers 11 (Springer, 2009).

Lu, Y. & Xu, L. D. Internet of Things (IoT) cybersecurity research: a review of current research topics. IEEE Internet Things J. 6, 2103–2115 (2019).

Gao, Y., Al-Sarawi, S. F. & Abbott, D. Physical unclonable functions. Nat. Electron. 3, 81–91 (2020).

Sun, N. et al. Random fractal-enabled physical unclonable functions with dynamic AI authentication. Nat. Commun. 14, 2185 (2023).

Kim, Y. et al. Reconfigurable multilevel optical puf by spatiotemporally programmed crystallization of supersaturated solution. Adv. Mater. 35, 2212294 (2023).

Nguyen, T.-N., Park, S. & Shin, D. Extraction of device fingerprints using built-in erase-suspend operation of flash memory devices. IEEE Access 8, 98637–98646 (2020).

Chen, A. Utilizing the variability of resistive random access memory to implement reconfigurable physical unclonable functions. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 36, 138–140 (2014).

Guajardo, J., Kumar, S. S., Schrijen, G.-J. & Tuyls, P. FPGA intrinsic PUFs and their use for IP protection. In Proc. 9th Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems-CHES 2007: International Workshop, Vienna, Austria, September 10–13, 2007 (Springer, 2007).

Kim, M. S. et al. Revisiting silk: a lens-free optical physical unclonable function. Nat. Commun. 13, 247 (2022).

Gu, Y. et al. Gap-enhanced Raman tags for physically unclonable anticounterfeiting labels. Nat. Commun. 11, 516 (2020).

Caligiuri, V. et al. Hybrid plasmonic/photonic nanoscale strategy for multilevel anticounterfeit labels. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 49172–49183 (2021).

Lu, Y. et al. Plasmonic physical unclonable function labels based on tricolored silver nanoparticles: implications for anticounterfeiting applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 9298–9305 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Inkjet-printed unclonable quantum dot fluorescent anti-counterfeiting labels with artificial intelligence authentication. Nat. Commun. 10, 2409 (2019).

Zhang, R. et al. Nanoscale diffusive memristor crossbars as physical unclonable functions. Nanoscale 10, 2721–2726 (2018).

Jiang, H. et al. A provable key destruction scheme based on memristive crossbar arrays. Nat. Electron. 1, 548–554 (2018).

Nili, H. et al. Hardware-intrinsic security primitives enabled by analogue state and nonlinear conductance variations in integrated memristors. Nat. Electron. 1, 197–202 (2018).

Oh, J. et al. Memristor-based security primitives robust to malicious attacks for highly secure neuromorphic systems. Adv. Intell. Syst. 4, 2200177 (2022).

Deng, D., Hou, S., Wang, Z. & Guo, Y. Configurable ring oscillator PUF using hybrid logic gates. IEEE Access 8, 161427–161437 (2020).

Lee, S. et al. Graphene-based physically unclonable functions with dual source of randomness. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 33878–33889 (2023).

Dodda, A. et al. Graphene-based physically unclonable functions that are reconfigurable and resilient to machine learning attacks. Nat. Electron. 4, 364–374 (2021).

Yang, H. I. et al. Simulation of a randomly percolated CNT network for an improved analog physical unclonable function. Sci. Rep. 14, 8811 (2024).

Jeong, J. S., Lee, G. S., Park, T. E., Lee, K. Y. & Ju, H. Bio-inspired electronic fingerprint PUF device with single-walled carbon nanotube network surface mediated by M13 bacteriophage template. Sci. Rep. 12, 20096 (2022).

Alharbi, A., Armstrong, D., Alharbi, S. & Shahrjerdi, D. Physically unclonable cryptographic primitives by chemical vapor deposition of layered MoS(2). ACS Nano 11, 12772–12779 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. Bright and stable anti-counterfeiting devices with independent stochastic processes covering multiple length scales. Nat. Commun. 16, 502 (2025).

Aman, M. N., Chua, K. C. & Sikdar, B. Mutual authentication in IoT systems using physical unclonable functions. IEEE Internet Things J. 4, 1327–1340 (2017).

Kim, J. H. et al. Nanoscale physical unclonable function labels based on block copolymer self-assembly. Nat. Electron. 5, 433–442 (2022).

Lee, S. et al. Machine learning attacks-resistant security by mixed-assembled layers-inserted graphene physically unclonable function. Adv. Sci. 10, e2302604 (2023).

Yakunin, S. et al. Radiative lifetime-encoded unicolour security tags using perovskite nanocrystals. Nat. Commun. 12, 981 (2021).

Leem, J. W. et al. Edible unclonable functions. Nat. Commun. 11, 328 (2020).

Smith, J. D. et al. Plasmonic anticounterfeit tags with high encoding capacity rapidly authenticated with deep machine learning. ACS Nano 15, 2901–2910 (2021).

Im, H. et al. Chaotic organic crystal phosphorescent patterns for physical unclonable functions. Adv. Mater. 33, e2102542 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Triple-layer unclonable anti-counterfeiting enabled by huge-encoding capacity algorithm and artificial intelligence authentication. Nano Today 41, 101324 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. An all-in-one nanoprinting approach for the synthesis of a nanofilm library for unclonable anti-counterfeiting applications. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1027–1035 (2023).

Lakowicz J. R. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy 3rd edn (Springer, 2006).

Hochreiter, B., Pardo Garcia, A. & Schmid, J. A. Fluorescent proteins as genetically encoded FRET biosensors in life sciences. Sensors 15, 26281–26314 (2015).

Förster, T. Zwischenmolekulare energiewanderung und fluoreszenz. Ann. der Phys. 437, 55–75 (1948).

Hildebrandt N. How to apply FRET: From experimental design to data analysis. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA (Weinheim, 2013).

Chou, K. F. & Dennis, A. M. Forster resonance energy transfer between quantum dot donors and quantum dot acceptors. Sensors 15, 13288–13325 (2015).

Lakowicz J. R. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy 3rd edn. (Springer, 2006).

Medintz, I. L. et al. Self-assembled nanoscale biosensors based on quantum dot FRET donors. Nat. Mater. 2, 630–638 (2003).

Ruhrmair, U. et al. PUF modeling attacks on simulated and silicon data. IEEE T Inf. Foren. Sec. 8, 1876–1891 (2013).

Shao, B. et al. Highly trustworthy in-sensor cryptography for image encryption and authentication. ACS Nano 17, 10291–10299 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Nano & Material Technology Development Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2024-00408446). This research was supported by the Technology Innovation Program funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea) (No. 20019400).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K. and B.C.J. designed this project. B.C.J. and B.-K.J. supervised the project. K.K. designed, fabricated, and characterized all optical PUF devices. S.S., J.Y., and J.C.B. prepared the materials and performed the nanoimprinting process for device fabrication. B.C.J. and Y.K. analyzed the anticounterfeiting performance and resilience to ML attacks of the PUFs using a Fourier series-based regression model. Y.M. designed and prepared the computer vision processing software for analyzing the luminescent images of the PUF devices. This manuscript was primarily written by K.K. and B.C.J., with contributions from all authors. The final version of the manuscript was approved by all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Xiaohu Liu and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, K., Moon, Y., Kim, Y.K. et al. Optical physical unclonable functions based on Förster resonant energy transfer in multi-color quantum dots. Commun Mater 6, 270 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00984-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00984-z