Abstract

This study demonstrates a compact, modular platform that simultaneously generates freshwater and hydrogen gas by leveraging nanoelectrokinetic ion concentration polarization through cation-exchange membranes (CEMs). Using a microfluidic platform, we demonstrate real-time concurrent hydrogen production at the cathode and freshwater production adjacent to the anodic side of CEM. Ion removal is confirmed by fluorescence imaging and ion chromatography, while gas generation is validated using pH indicators. To evaluate practical performance, the device is scaled-up to a mesoscale platform, enabling quantitative measurement of purification efficiency and hydrogen output across varying parameters such as applied currents and source water concentration, etc. We demonstrate that approximately 10% of input electrical energy is recovered as hydrogen, improving overall energy efficiency and enabling the possibility of periodically substituting externally supplied power with internally produced hydrogen. At higher applied currents, hydrogen ions transport through CEM is favored over sodium ion transport, boosting hydrogen production efficiency and device durability. This energy-recoverable purification platform reduces infrastructure needs and suits for decentralized and portable applications in resource-limited settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ensuring access to clean water and sustainable energy remains a fundamental global challenge, particularly in decentralized or resource-limited settings. These two demands are often intertwined: water purification processes require significant energy input, while many energy production systems rely heavily on water resources. This interdependence calls for diverse technological efforts aimed at improving water and energy systems either independently or in tandem, depending on application needs.

On energy production, electrochemical hydrogen production has emerged as a leading technology for clean energy generation1,2. In particular, ion-exchange membranes play a central role in electrolyzer systems by enabling selective ion transport between electrodes while physically separating the anodic and cathodic reactions. This architecture offers efficient hydrogen and oxygen generation in separate chambers, thereby improving overall conversion efficiency and gas purity3,4. Beyond their role in energy systems, ion-exchange membranes are also widely used in water treatment applications5. A representing example is electrodialysis (ED), which produces freshwater utilizing the alternative stacking of both cation exchange membrane (CEM) and anion exchange membrane (AEM) with DC electric field across the stack6,7. Thus, there have been reports on ED’s ability to produce hydrogen gas and freshwater simultaneously8,9. However, protons favorable for hydrogen production are mostly trapped between the laminated space composed of CEM and AEM layers in ED, limiting continuous proton transport across the membrane. On the other hand, ion concentration polarization (ICP) purification allows protons to move freely through a stacked membrane structure composed solely of CEMs, thereby creating a favorable ionic environment that can support hydrogen production at the cathode10. Therefore, ICP purification enables a one-step process for combining purification and electrolysis.

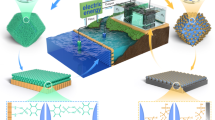

Building upon the nanoelectrokinetic transport of ions through ion exchange membranes, this study aims to create an integrated system capable of achieving simultaneous water purification and hydrogen generation in a one-step process as shown in Fig. 1. In a nanoelectrokinetic phenomenon known as ICP through unipolar ion exchange membranes and their surrounding fluids, by applying a voltage across CEM, an ion depletion zone (IDZ) is formed on the anodic side and an ion enrichment zone (IEZ) on the cathodic side11. In the IDZ, not only salt ions but also larger impurities can be actively repelled or redirected, enabling ICP purification to remove a wide range of contaminants—including heavy metals, suspended solids, bio-contaminants, and even oils—in a single step, whereas ED is largely limited to salt ion removal10,12,13. Importantly, ICP-based desalination systems have been experimentally demonstrated to achieve higher salt removal ratios than ED at comparable or even lower energy consumption levels. This advantage stems from the unique ion transport dynamics within the depletion zone, which enhances separation efficiency without requiring alternating AEM/CEM stacks12,13. Furthermore, as previously described, the continuously supplied protons are reduced in the IEZ to generate hydrogen gas. A detailed comparison between ICP and ED is provided in the Supplementary Information. Leveraging this principle, our approach extracts purified water from the IDZ, as successfully demonstrated in our previous seawater desalination study10, while simultaneously reducing protons to hydrogen gas at the cathodic electrode. This integrated process enables multifunctional treatment capabilities that go beyond those of conventional ED or reverse osmosis (RO) systems.

a Schematic illustration of the system for simultaneous hydrogen gas and freshwater production using ICP. In the upper anodic channel, saltwater splits into brine (green region) and purified water (sky blue region) streams by the formation and expansion of IDZ near CEM. In the lower cathodic channel, protons transported through CEM create a proton-rich stream (acidic red region), which is reduced to hydrogen gas at the cathode, eventually resulting in a proton-depleted stream (basic purple region). b Magnified view of near CEM region from (a), illustrating the competitive ion transport processes. Na+ ions, moving from the anodic channel to the cathodic channel, primarily contribute to water purification, while H+ ions play a crucial role in simultaneous hydrogen production.

Another key advantage of employing nanoelectrokinetic ICP water purification is the inherent scalability and compact design, making the technology well-suited for small-scale or portable applications. Traditional RO systems are optimized for centralized plants that treat thousands of tons of water per day and face limitations in miniaturization for decentralized use. In contrast, the ICP module presented in this study can be designed to produce only a few liters of purified water per day, and the overall throughput can be linearly increased by parallelizing multiple modules without the need to redesign the system architecture. Thanks to this scalable, lightweight form factor and the additional benefit of simultaneous hydrogen production, ICP becomes especially attractive for deployment in size- and infrastructure-constrained environments such as wearable healthcare sector14, disaster zones15,16, military operations17,18, and even space missions19,20. The hydrogen gas generated at the cathode can be collected and reconverted into electricity, for instance using a fuel cell, thus improving the total energy efficiency of the purification process. Rather than competing with large-scale desalination infrastructure to solve the energy-water nexus at global scale, the proposed ICP approach fills a critical gap by providing compact, energy-efficient “micro-utilities” that deliver both clean water and power in resource-limited settings.

Despite these advantages, a major hurdle to develop the simultaneous production system is that the movement of Na+ through ion-exchange membranes is favorable for water purification system, while the H+ transport is preferable for hydrogen production system. In practice, however, ion transport within ion-exchange membranes involves a competitive process between Na+ and H+ in both systems, necessitating a thorough analysis and a refined operational strategy to achieve optimal ion selectivity and system efficiency. Therefore, a deep understanding and precise control of the nanoelectrokinetic processes through ion exchange membrane play a pivotal role in both water purification and electrolytic hydrogen production.

In this work, we demonstrate the simultaneous production of freshwater and hydrogen gas using branched microfluidic channels with ion exchange membrane. Specifically, by incorporating microelectrodes within the channels, we qualitatively visualize simultaneous hydrogen gas bubble generation at the reduction electrode, while water purification occurs at the anodic side which is quantitatively confirmed by ion chromatography. The gas bubble formed at the cathodic side was evidenced as hydrogen by the color change of pH indicator of the solution collected at the cathodic reservoir. For the quantitative analysis and direct visualization of hydrogen gas production, we build a scaled-up device capable of producing sufficient hydrogen gas for gas chromatography (GC) analysis. Furthermore, we observed that the transport of Na+ and H+ varied in a competitive manner depending on the applied current, with H+ transport becoming more dominant as the current increased. Through this nanoelectrokinetic study of ion transport through the membrane, we propose a simple and straightforward strategy to regulate the competition between the Na+ and H+ ions, thereby enhancing proton transport across the membrane for efficient and stable hydrogen production with simultaneous water purification.

Results and Discussion

The concept for simultaneous hydrogen gas and freshwater production proposed in this study is described in Fig. 1a. The ICP desalination technology, which we intend to use as a water purification method, can effectively remove salt ions and suspended particles from saltwater10. By applying an electric field across a cation-exchange membrane, an ion depletion zone is formed adjacent to the membrane, which repels substances larger than ions, causing most of contaminants to reroute to brine channel due to the electroneutrality10,21. In the meantime, cations including Na+ and H+ preferentially transport through the membrane due to the cation-selectivity of the membrane22,23,24. Finally, one could collect the purified water as shown in Fig. 1a. During this water purification process at the upper channel, one would concurrently expect to have a proton- or sodium-rich stream flowing toward GND reservoir. By installing a microelectrode in the middle of the channel, hydrogen gas is generated on the surface of the microelectrode, and the proton-rich stream would turn to be the proton-depleted stream, which will be verified by analyzing pH changes in lower channel.

As outlined in the introduction section, unlike conventional ED systems, ICP purification enables the continuous supply of cations all the way down from the anode to the cathode because of utilizing only CEM. However, to achieve a simultaneous process, as illustrated in Fig. 1b, it is necessary to regulate the competitive transport between Na+ and H+ ions through CEM. Enhanced transport of Na+ ions benefits the purification process, while increased transport of H+ ions favors hydrogen gas generation. We first focus on the demonstration of simultaneous production of hydrogen and freshwater using a microfluidic device in Section “Demonstration of simultaneous hydrogen gas generation and freshwater collection in a microfluidic platform”. Subsequently, the same process is demonstrated with a scaled-up device in Section “Demonstration of simultaneous hydrogen gas generation and freshwater collection in a mesoscale platform”. Finally, a strategy to control aforementioned competitive transport will be discussed in Section “Competitive transport of Na+ and H+ ions through the ion-exchange membrane Analysis by transported Na+ ions”.

Demonstration of simultaneous hydrogen gas generation and freshwater collection in a microfluidic platform

The microfluidic device used for this demonstration is shown in Fig. 2a. See experimental method section for the fabrication method. The internal structure of each channel within this microfluidic device is shown in the magnified image (Fig. 2b). Note that this image consists of a fluorescent image (upper) and a brightfield image (lower), depicting the concurrent production of purified water and hydrogen gas generation, respectively. The two channels are connected by a Nafion membrane as a representative CEM, and two kinds of electrolyte solution were injected into upper and lower channels from the inlet on the left side with the flow rate of 150 nL/min using a syringe pump. For the demonstration of water purification, NaCl solution was injected into the upper channel, as a representative saltwater feed. Although any electrolyte can be used in the lower channel, referred to as the ‘hydrogen channel,’ LiCl was selected as the electrolyte because it contains a cation different from Na+, allowing for more accurate measurement of Na+ ion migration from the upper channel to the lower channel. Note that Li+ ions were used solely for analytical purposes in lab-scale experiments, while arbitrary supporting electrolytes (e.g., Na+ , K+ salts or others) could be used in practical applications. The upper channel is branched at the vicinity of the Nafion membrane to separate the purified water and remaining brine. By adding a small amount of fluorescent dye to the NaCl saltwater and observing the solution flow in dark field, a clear IDZ boundary was visualized, confirming effective water purification. Since the fluorescent dye is also charged, it is repelled from the IDZ and flows out with the brine. Therefore, in the anodic side channel, the fluorescent-colored brine solution exits through the ‘brine channel’ outside the IDZ, while the purified water, appearing black, flows through the ‘purified water channel’ located closer to the CEM. Simultaneously, a microelectrode was integrated into the hydrogen channel to clearly visualize gas generation. The generated gas bubbles are carried out through the outlet along with the rinsing water. Supplementary Video 1 shows the simultaneous generation of freshwater in the upper channel and gas bubble formation at the microelectrode in the lower channel, carried out with the flow.

a An image of the microfluidic device demonstrating simultaneous hydrogen gas and freshwater production. The upper channel processes the saltwater feed introduced from the inlet on the left-hand side, which is split into brine and purified water channels near the Nafion membrane. The lower hydrogen channel receives rinsing water from its inlet and carries cations transported through CEM. In this microfluidic device, the Nafion membrane is formed by coating a Nafion solution onto a glass substrate, and it connects the upper and lower PDMS microchannels. The current is applied via an anode ( + V) and a cathode (GND) positioned at the reservoirs of the brine and hydrogen channels, respectively. b Magnified views of the microfluidic device showing IDZ formation in the upper anodic channel with fluorescent image and hydrogen gas generation at the microelectrode in the lower cathodic channel with brightfield image. See Supplementary Video 1. c Concentration of Na+ in brine, purified water, and hydrogen channels at various feed saltwater concentrations (10–500 mM NaCl). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from measurements on 5 different devices. The inset depicts the molar ratio of Na+ in each channel. d Visualization of pH changes with pH indicators added to both channels: the brine channel exhibited a basic environment due to OH− generation, while the hydrogen channel turned acidic due to H+ transport through Nafion. e Final pH changes in each reservoir with pH indicators, showing a basic environment in the reservoir of the hydrogen channel (purple), a neutral pH in the reservoir of the purified water channel (green), and an acidic pH in the reservoir of the brine channel (yellow). The inset depicts the pH measurements in the reservoir of the hydrogen channel via a pH meter during current application, starting with 10 μL of 10 mM KCl in the reservoir without pH indicator. f Schematic of the electrochemical reactions contributing to the observed pH changes, including hydrogen production at the cathode and potential oxidation reactions at the anode, such as chlorine gas evolution or water oxidation.

To verify the efficiency of water purification in this micro/nanofluidic device, we measured the concentration of Na+ ions in the solution flowing through each channel. As shown in Fig. 2c, the comparison of the concentrations in each stream of the brine, purified water, and hydrogen channels demonstrates that water purification occurs on this platform as we expected from the fluorescent image in Fig. 2b, even when the Na+ concentration of the saltwater feed varies from low (10 mM, 20 mM and 40 mM) to high (200 mM and 500 mM, representing brackish water and seawater, respectively). Notably, across all feed concentrations, the Na+ concentration remains lowest in the purified water channel. For feed concentration of 10–40 mM and 200 mM, the Na+ concentration in the purified water decreased to approximately 10% of the initial feed concentration, indicating effective purification (e.g., 10 mM to 1.01 ± 0.54 mM, 20 mM to 1.79 ± 0.77 mM, 40 mM to 4.63 ± 3.21 mM, and 200 mM to 25.78 ± 13.09 mM). However, for the 500 mM feed, the concentration decreased to above 20% of the initial feed concentration (e.g., 500 mM to 121.93 ± 54.43 mM), primarily due to the diminished effectiveness by instability of ICP at higher salt concentration25. As the saltwater concentration increases to higher levels, such as 500 mM, the thickness of the electric double layer on the inner walls of nanoporous structures such as Nafion can become thinner, potentially reducing ion selectivity of the membrane and weakening the ICP effect, leading to unstable IDZ formation. Furthermore, this figure shows that the Na+ concentration in the hydrogen channel is higher than that in the brine channel, indicating a stronger migration of Na+ ions from the inlet toward the hydrogen channel than toward the brine channel. This trend is further corroborated by the molar ratio of Na+ ions in each channel, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2c. This result suggests that the movement of Na+ ions into the hydrogen channel plays a significant role in the water purification process, as the removal of Na+ ions is essential for effective purification.

While it appears that the significant migration of Na+ ions into the hydrogen channel contributes substantially to the water purification process as shown in Fig. 2c, it should be emphasized that H+ ions also migrate through CEM. This phenomenon was observed in Fig. 2d. For this experiment, pH indicators were added to both feed solutions, which consisted of 10 mM NaCl in the upper channel and 10 mM LiCl in the lower channel, and the color changes of pH indicators were monitored. The pH indicator color in the hydrogen channel changed to red (i.e. acidic), while that in the brine channel shifted to blue (i.e., basic). The red color change in the hydrogen channel can be attributed to the addition of H+ ions from the upper channel. Due to the extremely amplified electric field inside IDZ26,27, especially at the interface between Nafion and saltwater, water dissociation vigorously occurs so that one has a number of generated H+ and OH− 28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Then, H+ ions can pass through CEM so that pH indicator turns red at the interface between Nafion and rinsing water, while OH− ions are rejected from IDZ so that pH indicator turns blue at “certain distance” from the Nation. This certain distance is the thickness of IDZ and one can extract fluid within it, leading to water purification process. This experiment demonstrated that the flow of H+ ions through Nafion can be observed even from the neutral NaCl saltwater. These H+ ions are advantageous for promoting simultaneous hydrogen gas production within the system. Figure 2c, d demonstrated that the migration of Na+ ions advantageous for water purification and the transport of H+ ions beneficial for hydrogen production occur concurrently through CEM. Therefore, to enable the simultaneous production of hydrogen and freshwater using a single membrane, a comprehensive study of the competitive transport between Na+ and H+ ions is required, which will be discussed in more detail in Section “Competitive transport of Na+ and H+ ions through the ion-exchange membrane Analysis by transported Na+ ions”.

Following this, we observed the color changes of pH indicator in pipette tips inserted at the outlet of the microchannel to verify the eventual fate of H+ ions. In Fig. 2d, the pH indicator near CEM of the hydrogen channel turned red inside the microsystem, indicating an acidic environment due to the hydrogen ions passing through the CEM. However, as shown in Fig. 2e, the pH indicator at the reservoir of the hydrogen channel exhibited a deep purple color, signifying high alkalinity. This observation provides indirect evidence that the gas bubbles produced in the microsystem were hydrogen gas, since hydrogen gas can be generated either by the reduction of hydrogen ions (H+ + e− → 1/2H2, E0 = 0.0 VSHE) or by the reduction of water (H2O + e− → 1/2H2 + OH−, E0 = −0.828 VSHE) at the cathode, both of which result in the pH increase of the solution due to the consumption of H+ ions or the generation of OH− ions, as illustrated in Fig. 2(f). While the other cations such as Na+ and Li+ are present near cathode in our system, the reduction of hydrogen ions or water is more favorable than the reduction of other species, such as Na+ and Li+ (Na+ + e− → Na, E0 = −2.71 VSHE; Li+ + e− → Li, E0 = −3.04 VSHE)35. Thus, we would expect all applied current to be converted to hydrogen gas, assuming a Faradaic Efficiency (FE) of nearly 100% with the Pt electrode. To neutralize pH at cathodic reservoir, a proportional amount of H+ ions would need to be supplied to the cathode side via CEM. However, as observed in Fig. 2c, d, both Na+ ions and H+ ions contribute to the charge transport through CEM. Consequently, when using saltwater (i.e., not pure water or acidic water) as the feed, the total charge passing through CEM cannot be attributed solely to H+ ion transport due to competitive ion transport. This competition results in a deficit of hydrogen ions at the cathode, leading to a significant increase in pH. Thus, the color change of the pH indicator at the cathode indirectly confirms both the production of hydrogen gas and the occurrence of competitive ion transport through CEM. Moreover, Fig. 2e corroborates that water purification is occurring concurrently with the hydrogen production process, consistent with the results shown in Fig. 2c. At the pipette tips located at the end of the brine channel and the water purified channel, the brine reservoir exhibited acidity, while the purified water reservoir showed neutral pH. In an aqueous NaCl solution, possible oxidation reactions at the anode include chlorine gas evolution (Cl− → 1/2Cl2 + e−, E0 = 1.358 VSHE) and water oxidation (1/2H2O → 1/4O2 + H+ + e−, E0 = 1.229 VSHE)35, both of which can acidify the solution (Fig. 2f). In addition, other chlorine-related oxidation reactions such as hypochlorous acid (HClO) formation (Cl− + H2O → HClO + H+ + 2e−, E0 = 1.482 VSHE) may also occur, further contributing to the local acidification due to proton generation35. This explains the acidic nature of the brine reservoir. In contrast, the reservoir of the purified water channel displayed a neutral pH (green color), as it contained purified water with most ionic species removed during the purification process within the microsystem.

Demonstration of simultaneous hydrogen gas generation and freshwater collection in a mesoscale platform

In the microfluidic platform demonstration described above, the indirect evidence of hydrogen gas generation was obtained through the color change of pH indicators, but the volume of the generated bubbles was too small for quantitative hydrogen production analysis. Therefore, we scaled up the microfluidic platform and fabricated a mesoscale device using 3D printing to provide the direct evidence of the simultaneous production of hydrogen and purified water. Notably, this mesoscale approach overcomes the limitations of microfluidic desalination systems such as low throughput and high pressure drop by enabling scalable design via 3D printing while preserving key nanoelectrokinetic behaviors. Multiple modules can be integrated in parallel to increase capacity while maintaining a compact, modular form factor. The modular and expandable units are well-suited for decentralized applications, including disaster relief, military operations, and space missions. A recent study by our group demonstrated this concept in a wearable artificial kidney platform, highlighting the potential of ICP-based systems in extreme environments14.

To realize higher throughput in hydrogen and freshwater production, however, hydrodynamic and electrokinetic instabilities must be carefully addressed. Simply increasing the width of microchannels can induce hydrodynamic instabilities, leading to IDZ boundary layer collapse and local mixing36,37,38, which decreases the quality of freshwater. In previous works, we studied the suppression of hydrodynamic instabilities using microstructures39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48. Based on this, we designed a device that maintains the hydrodynamic domain of a microfluidic platform, while the design can significantly enhance the throughput of freshwater and hydrogen production. The designed mesoscale device was fabricated using a 3D printer, as shown in Figs. 3a–c. Detailed fabrication process is described in Experimental methods. The purification chamber has an internal volume of 11 mm × 10 mm × 7 mm, and the hydrogen chamber had an internal volume of 11 mm × 10 mm × 4 mm, representing a scaled-up version of the microfluidic platform and serving as a mesoscale module in this study. The purification chamber and hydrogen chamber were separated by a Nafion sheet (contact area of 11 mm × 10 mm). To prevent mixing between purified water formed near the Nafion membrane and brine pushed outside the IDZ, fin-type structures were designed to guide the two streams separately. Argon-purged saltwater and rinsing water were introduced at the inlets of the device using syringe pumps at the flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. In the meantime, redox reactions occurred at the electrodes inserted in each chamber. This allows the production of freshwater and acidic by-products in the purification chamber. Then, the freshwater and the by-product split toward purified stream and brine stream, respectively. On the other hand, hydrogen gas was produced in hydrogen chamber and flow out naturally with waste water to collect the gas. The amount of hydrogen gas was enough to collect for GC analysis in this mesoscale device. See Supplementary Video 2 for the hydrogen gas production. Therefore, we can achieve stable IDZ separation, improved hydrogen gas collection, and quantify the quality of the produced freshwater and the amount of hydrogen generated using this mesoscale module.

a Schematic diagram of the 3D mesoscale device, scaled-up from the geometry of the microfluidic device, employing the same strategy for simultaneous hydrogen gas and freshwater production. The device comprises a purification chamber and a hydrogen chamber, separated by a Nafion sheet. Fin-type structures within the purification chamber stabilize the IDZ and guide the separation of purified water and brine streams. b Cross-sectional diagram of the 3D mesoscale device. The device operates via same mechanism as the microfluidic device shown in Fig. 2b but is extended along the z-axis to form a scaled-up structure. c Actual image of the 3D-printed mesoscale device, showing the separation of streams and gas production. Saltwater and rinsing water are introduced into the purification and hydrogen chambers, respectively, and hydrogen gas is produced at the cathode in the hydrogen chamber. d Quantitative results for hydrogen gas production and Na+ ion concentration in purified water at 20 mM feed concentration under various applied currents (4, 10, 15 and 20 mA). Hydrogen production increased linearly with the current, while Na+ concentration in purified water plateaued, indicating diminishing returns in purification performance. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from measurements on 4 different devices. e Ratio of Na+ ions transported to each stream at 20 mM feed concentration. Higher currents increased the fraction of Na+ ions in the hydrogen chamber, while decreasing the fractions in the purified water and brine streams. f Quantitative results for hydrogen gas production and Na+ ion concentration in purified water at 200 mM feed concentration under various applied currents (40, 100, 150 and 200 mA). Hydrogen production and Na+ concentration have similar trends of (c). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from measurements on 4 different devices. g Ratio of Na+ ions transported to each stream at 200 mM feed concentration. Higher currents increased the fraction of Na+ ions in the hydrogen chamber, while decreasing the fractions in the purified water and brine streams.

Figure 3d, e show the quantitative evaluation of hydrogen and freshwater production at the representative low concentration of 20 mM, which was a previously tested concentration in the microfluidic platform for comparison. The experiment was conducted under constant current conditions by applying an electric field across the purification chamber and hydrogen chamber, each equipped with Pt wire electrodes. As shown in Fig. 3d, hydrogen production increased proportionally with the current (e.g., 1.65 ± 0.03 mL/h at 4 mA, 4.69 ± 0.11 mL/h at 10 mA, 7.43 ± 0.15 mL/h at 15 mA, and 9.91 ± 0.37 mL/h at 20 mA). The Faradaic Efficiency (FE), which represents the fraction of charges converted into hydrogen gas compared to the total charge, was approximately 98% at 4 mA and reached up to 100% at 10 mA, 15 mA and 20 mA, attributed to the use of Pt wire optimized for hydrogen generation. For water purification, when the feed concentration was 20 mM, the quality of freshwater improved with increasing current (e.g., 11.04 ± 1.04 mM at 4 mA, 6.16 ± 0.94 mM at 10 mA, 4.54 ± 0.74 mM at 15 mA, and 3.37 ± 0.83 mM at 20 mA), as shown in Fig. 3d, while the rate of improvement slightly saturated at higher currents. To track Na+ transportation, the ratio of moles of Na+ ions migrating to each stream was plotted in Fig. 3e as a function of applied current, showing that the fraction in the hydrogen chamber increased with higher current. Contrarily, the fraction in brine and purified water keeps decreasing. These analyses suggest that while Na+ ions are transported more through CEM as the current increases, they eventually reach a saturation point (indicating that purification performance saturates). Concurrently, however, hydrogen gas production continues to increase linearly with the applied current.

The same conclusion was also obtained at a high concentration representative value of 200 mM as shown in Fig. 3f, g. Given that the over-limiting current regime for ICP is expected to shift to higher voltage and current ranges at higher feed concentrations25, constant currents of 40, 100, 150, and 200 mA—ten times higher than those used for the 20 mM tests—were applied. As a result, hydrogen production increased proportionally with the applied current (e.g., 20.87 ± 1.83 mL/h at 40 mA, 53.51 ± 2.61 mL/h at 100 mA, 83.97 ± 0.83 mL/h at 150 mA, and 111.50 ± 3.73 mL/h at 200 mA), as shown in Fig. 3f. For water purification, with a 200 mM feed, the quality of freshwater improved with increasing current (e.g., 125.79 ± 5.40 mM at 40 mA, 59.18 ± 10.79 mM at 100 mA, 52.04 ± 4.51 mM at 150 mA, and 46.30 ± 6.68 mM at 200 mA). The slightly lower purification levels observed with the 200 mM feed compared to the 20 mM feed are interpreted as a weakening of ICP due to the thinner electric double layer within the nanostructure of the Nafion membrane at higher concentrations. However, similar to the 20 mM case, we observed that as the current increased, more Na+ ions migrated to the hydrogen chamber in Fig. 3g, but the rate of decrease in freshwater concentration relative to the feed concentration diminished at higher currents (Fig. 3f). The latter observation is attributed to the competitive transport of Na+ and H+ ions through the ion-exchange membrane, which will be discussed in the next section.

Next, we discuss potential applicability of hydrogen produced concurrently with freshwater in our system. As observed above, although the quality of freshwater improves with increasing current, the degree of improvement reaches a saturation point. This indicates that achieving higher purification quality requires significantly greater energy consumption, which has been a primary limitation in most of desalination systems. However, by utilizing the hydrogen produced simultaneously with ICP purification, we can improve the energy efficiency of ICP purification systems through the following approach, inspired by hybrid type electric vehicle. Producing 1 liter of freshwater from 200 mM brackish water reduced to a concentration of 50 mM at 200 mA requires 397.71 Wh, which is a substantial energy demand but is able to produce 1.59 g of hydrogen at the same time using our device. Converting this hydrogen back into electricity using a commercial fuel cell with a 60% energy conversion efficiency yields 31.80 Wh of electrical energy. When this energy is recycled to power the ICP purification system, the energy efficiency improves by 8.00% compared to conventional ICP purification systems that do not recycle hydrogen. For detailed calculations on energy efficiency, refer to the Supplementary Information. In the desalination research community, while the energy consumption of our system may appear higher than that of conventional ED (20–200 Wh/L at optimized condition) or RO systems (3.5–5 Wh/L, achievable only at large-scale plants), it should be noted that our system performs functions beyond ionic desalination including simultaneous hydrogen production and non-ionic contaminant rejection, which cannot be fully captured by a direct Wh/L comparison alone. Importantly, by optimizing the device through strategies such as enhancing surface conduction45,46,47 or utilizing recirculation flow41,48 to improve ion transport, it is possible to substantially reduce the energy consumption required for ICP purification. Notably, while other technologies such as RO require large-scale infrastructure, the ICP purification platform is inherently scalable through parallel integration of compact modules, making it well-suited for small, portable, and customizable systems. This scalability means that, despite the seemingly high energy consumption, the actual cost remains relatively low compared to the total expenses required when producing thousands of tons of water using RO. Building on this modularity, the single mesoscale unit can be readily scaled up by parallelizing multiple modules to achieve high-capacity output, paving the way for practical deployment in real-world applications, to be further pursued in our future work. Moreover, the ICP approach offers tunable performance, allowing dynamic control over both water quality and hydrogen production by adjusting the applied current. The broader benefits of the ICP system were summarized in Supplementary Table 1 and illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Competitive transport of Na⁺ and H⁺ ions through an ion-exchange membrane

Analysis by transported Na+ ions

In the previous section, we observed that as the current increased, the purification performance saturated, while the hydrogen gas production continues to increase with the applied current (Fig. 3d, f). To elucidate the underlying mechanism of this phenomenon, we analyzed how the number of moles of Na+ ions transported through CEM (ΔNa+) contributes to the total charge transported through CEM (ΔQ) according to the applied current values, as shown in Fig. 4, where the ΔNa+ values of each experiment were measured using ion chromatography. Interestingly, the molar ratio of Na+ ion transport relative to the total charge passing through the CEM (ΔNa+/ΔQ) decreased with higher current in both microfluidic device and mesoscale device as shown in Fig. 4a, b, respectively. This trend was consistent across all tested concentration conditions (10 mM ~ 500 mM in microfluidic device and 20 mM and 200 mM in the mesoscale device). In the microfluidic device, we adjusted the current to maintain the stable IDZ formation and freshwater production for each experiment by real-time observation of the fluorescent images showing the IDZ boundary so that the data is plotted as a function of the average current values (IAvg). The results in both plots demonstrated that the ΔNa+/ΔQ ratio decreased with increasing current as shown in Fig. 4a, b.

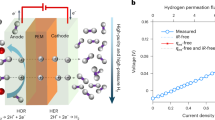

a The competitive transport relationship between Na+ and H+ ions through the Nafion membrane in the microfluidic device at various feed saltwater concentrations (10, 20, 40, 200, and 500 mM NaCl) as a function of applied current. The ratios of Na+ ion transport (ΔNa+) and H+ ion transport (ΔH+) to the total charge transport (ΔQ) through the CEM are represented as ΔNa+/ΔQ and ΔH+/ΔQ, respectively. The average current (IAvg.) was adjusted to maintain stable IDZ formation and freshwater production. b The competitive transport relationship between Na+ and H+ ions through the Nafion membrane in the mesoscale device at various feed saltwater concentrations (20 mM and 200 mM NaCl) as a function of the constant applied current. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from measurements on 4 different devices.

Once ΔNa+/ΔQ passing through the CEM decreases, alternative charge carriers should compensate the deficit of charge. The nano-structured ionomer of Nafion comprises a Teflon-like backbone with side chains terminated by sulfonate groups, forming a perfluorinated sulfonic-acid (PFSA) structure. In the nanoporous structure of Nafion with this strongly negatively charged surface, the electric double layers overlap along the pore surfaces, imparting high selectivity for cations within the Nafion structure. Considering these characteristics, the primary charge carriers through CEM are predominantly cations, as Nafion’s selectivity for cations is orders of magnitude greater than for anions, in general23,24. In our system, since NaCl aqueous solution was used as the feed, the cations that can pass through the Nafion membrane are Na+ and H+ ions. Therefore, we can express the total charge ΔQ as ΔQ = ΔNa+ + ΔH+, allowing the relationship of ΔNa+/ΔQ in Fig. 4 to be interpreted as ΔNa+/ΔQ = 1 - ΔH+/ΔQ, where ΔH+/ΔQ is the proportion of H+ ions relative to the total charge passing through the membrane. As shown in Fig. 4a, b where y-axis has two labels as ΔNa+/ΔQ and ΔH+/ΔQ, when varying the current at a fixed concentration, it is observed that H+ ions pass through more efficiently at higher currents. For instance, the gray circular symbols represent cases where Na+ concentration in salt water is 10 mM. At a lower current (indicated by the red dotted circle), total ion transport consists of 70 % by Na+ ion and 30 % by H+ ion. However, when a high current is applied (indicated by the blue dotted circle), the ion transport shifts, with Na+ decreasing to 40% and H+ increasing to 60% of the total ion transport. This trend was consistently observed across all tested concentration values in Fig. 4a (microfluidic device) and 4b (mesoscale device), while the increase of ΔH+/ΔQ with current appeared to plateau beyond ~100 mA.

The increase in the proportion of H+ ions over Na+ ions as the current increases can be attributed to enhanced water dissociation at the interface between Nafion and saltwater. This enhancement can be results of the synergistic combination of multiple mechanisms.

First, the sulfonic acid groups in Nafion provide a dense array of acidic sites, which accelerate the dissociation of water molecules into H+ and OH− ions28,32. This localized generation of protons increases the availability of charge carriers within the membrane, enhancing proton conductivity, especially at higher currents where rapid ion transport is required. Also Nafion’s sulfonic acid groups create an environment with an elevated local dissociation constant compared to bulk water. This increase is from the highly polar environment and electrostatic interactions within Nafion’s hydrophilic channels, which encourage water molecules to dissociate more readily than in a non-polar or bulk aqueous environment. Secondly, it has been reported that within IDZ, the electric field can amplify beyond 1 kV/cm26,27, sufficient to strip Li+ or Na+ ions of their hydration shells49. This amplified electric field not only peel off the hydration shells but also accelerates water dissociation via the second Wien effect28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Consequently, additional water molecules that have composed the hydration shell dissociate, generating further protons. Additionally, the exceptional mobility of protons within the Nafion structure, facilitated by the Grotthuss mechanism-which is more than an order of magnitude greater than that of Na+ ions23-enables rapid proton transport through CEM. This efficient proton removal shifts the equilibrium toward further water dissociation. Also, the concentration gradient established in this process further drives H+ diffusion from saltwater toward Nafion surface, reinforcing proton transfer through diffusion. However, in the mesoscale device of Fig. 4b, the observed plateau in ΔH+/ΔQ at high current suggests that the water dissociation process itself may become limited. Although strong electric fields within the IDZ promote water splitting via the second Wien effect, these fields may also reach a saturation point due to space-charge regulation and electroconvective instabilities that arise at high current densities25,38. Once the electric field enhancement within the IDZ is no longer linearly responsive to the applied current, further increases in water dissociation and proton supply are constrained.

While the quantitative enhancement of the dissociation constant by these synergistic effects remains an active area of research28,29,30,31,32,33,34, the mechanism provides a compelling explanation for the enhanced water dissociation observed at the Nafion interface and the consequent increase of ΔH+/ΔQ values in our study.

Analysis by transported H+ ions

To obtain experimental evidence for increase of H+ ion transport compared to the Na+ ion transport with higher applied current, we analyzed the pH values of the hydrogen chamber as a function of the applied current in the mesoscale platform, as shown in Fig. 5. In this case, the applied current was controlled to be constant total charge through CEM by applying 4 mA for 2.5 h, 10 mA for 1 hour, 20 mA for 0.5 hours, and 40 mA for 0.25 h at the feed concentration of 20 mM NaCl. The purpose of controlling the charge was to maintain the similar amount of hydrogen production (as indicated by black open circle symbol in Fig. 5). While the initial pH of the 20 mM LiCl solution as rinsing water injected into the hydrogen chamber was 5.58, pH rose above 11 for all four current conditions after hydrogen gas production and the subsequent consumption of H+ by reactions shown in Fig. 2f. However, despite similar hydrogen gas output, higher applied current led to relatively lower pH in the hydrogen chamber (as indicated by red triangle symbol and the right y-axis in Fig. 5), which is direct experimental evidence for enhanced H+ transport through CEM as applied current increases. This strategy is promising for efficient hydrogen production in our system, since the H+ ions serve as the primary reactants in the generation of hydrogen gas.

pH changes in the hydrogen chamber of the mesoscale device as a function of applied currenFor the 20 mM feed saltwater condition, the total charge passed through the system was kept constant by adjusting the application time for each current. The measured pH values in the hydrogen chamber (red triangles) and the calculated OH− ion concentrations (purple circles) are shown. The observed pH decreased in the hydrogen chamber at higher applied currents, despite similar hydrogen production levels, indicates enhanced H+ ion transport through the CEM. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from measurements on 4 different devices.

Furthermore, the decrease of pH values in hydrogen chamber has another advantage on the durability of the device. Given the ion product constant of water, Kw at 25 oC for pure water and aqueous solutions is Kw = [H+][OH−] = 1.0 × 10−14 mol2/L2, resulting in the relationship pH + pOH = 14 in the hydrogen chamber. Using this relationship, we calculated the concentration of OH− ions in the hydrogen chamber after applying current, as indicated by the purple circle symbol and the y-axis offset in Fig. 5. The OH− concentration after applying current at 4 mA × 2.5 h was approximately three times higher than at 40 mA × 0.25 h. Generally, in water electrolysis, the consumption of H+ due to hydrogen production raises the pH of the solution at the cathode significantly (i.e., extensive amount of OH- ions are generated). Once Mg2+, Ca2+, or other cations are present in the solution, these high pH conditions can lead to the formation of Mg(OH)2, CaCO3, or similar precipitates that contaminate the electrode and impair the durability of the device35,50. Considering the results in Fig. 5, operating the system at higher current to enhance H+ transport through the CEM can significantly reduce the formation of cationic precipitates at the cathode in the presence of ions such as Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions. Therefore, utilizing higher current to enhance H+ transport through CEM presents a straightforward and effective strategy not only to boost hydrogen production efficiency but also to protect the system from potential contamination and scaling issues. Moreover, the ICP system has demonstrated excellent long-term operational stability in our recent study, which reported continuous operation over 30 days without observable membrane degradation or scaling. These findings confirm the practical advantage of the CEM-only ICP configuration in terms of durability and fouling resistance51.

Conclusions

Efficient water purification and energy recovery in decentralized or resource-limited settings remain major engineering challenges, especially where infrastructure is minimal and portability is crucial. In this study, we demonstrate a compact platform that integrates freshwater production and hydrogen gas generation via a nanoelectrokinetic ICP process using CEMs. This approach defeats the key limitations of conventional methods, offering a scalable and energy-efficient alternative for small-scale, self-sustained applications.

Using a microfluidic device, we successfully demonstrated the simultaneous production of freshwater and hydrogen gas: Water purification was achieved by extracting fluid from IDZ, as confirmed by fluorescence imaging and ion concentration measurements, while hydrogen gas was concurrently generated at the cathode, evidenced by pH indicator color changes (Fig. 2). These findings were successfully scaled up in a mesoscale platform fabricated via 3D printing, enabling measurable hydrogen gas outputs for quantitative performance evaluation (Fig. 3). The mesoscale device maintained stable IDZ formation and effective separation of purified water and brine streams using fin-type structures. Also, the proportional increase in hydrogen production and concurrent improvement in freshwater quality with applied current underscores the scalability and practicality of this approach. Furthermore, by recycling the hydrogen gas generated during the ICP process, energy efficiency can be improved, offering a scalable and energy-efficient solution for integrated water purification and hydrogen production.

The suggested ICP module of our study is intrinsically engineered for “few-liter-per-day” duty cycles, far below the thousands of tons per day scale handled by conventional large plants. By parallelizing or stacking multiple ICP modules, the volumetric throughput of freshwater and the mass of hydrogen gas can be increased by one or more orders of magnitude without redesigning individual units. This combination of compact form factor, modular scalability, and intrinsic energy recovery makes the technology well suited to environments where size, mass, and infrastructure independence dominate design constraints: (i) wearable artificial kidney devices that continuously recycle only a few mL min−1 of dialysate14; (ii) portable kits for disaster relief that should supply roughly 2 L day−1 per person from contaminated sources15,16; (iii) forward military outposts requiring on-site purification from any accessible source17,18; and (iv) crewed space missions, where closed-loop recycling of bodily fluids and aqueous wastes, including water-based biopharma streams, requires compact, high-efficiency purifiers19,20. Rather than competing with megaton scale infrastructure, the proposed ICP system therefore fills a critical gap by providing portable, energy-efficient micro utilities that secure both water and power in resource limited conditions.

The study also unveiled the competitive ion transport dynamics through the CEM, revealing that H+ transport becomes increasingly dominant at higher applied currents as Na+ transport decreases (Fig. 4). The enhanced proton transport is attributed to water dissociation at the Nafion-saltwater interface by the synergistic effect of local functional groups of sulfonic acid, amplified electric fields within the IDZ, and the Grotthuss mechanism enabling rapid proton mobility. Experimental evidence, including pH measurements in the hydrogen chamber, validated this increased H+ transport (Fig. 5). Additionally, operating the system at higher currents reduced cathodic pH elevation and mitigated the risk of scaling from cationic precipitates, which can improve device durability and efficiency. These findings highlight that increasing the current applied through the CEM is a simple strategy to enhance both hydrogen production and water purification performance, while mitigating operational challenges.

In conclusion, this work establishes a versatile framework for compact water-hydrogen co-generation devices that prioritize modularity, portability, and energy efficiency. Future research will focus not only on optimizing membrane interfaces and microstructural designs to enhance ion transport and system durability, but also on scaling up the platform into fully functional, macroscale devices for real-world deployment. Ultimately, this platform has the potential to serve as a practical solution for decentralized water purification in off-grid environments.

Experimental methods

Device fabrication

The micro/nanofluidic devices for freshwater and hydrogen production were fabricated in the following method. A poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS, Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer kit, Dow Corning) block was fabricated to possess two microchannels of 200 μm width, 5 mm length, and 70 μm depth by the soft lithography method. Upper channel was bifurcated to separately collect freshwater and brine, as shown in Fig. 2a. Two microchannels were connected by Nafion membrane as a CEM. The Nafion solution (20 wt% resin, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was applied on the glass substrate using a surface patterning method. Briefly, a single strip of Nafion (200 μm width and ~1 μm thickness after drying) was patterned onto a slide glass using a straight microchannel of 200 μm width and 50 μm depth. For visualizing hydrogen gas bubble generation at the lower microchannel (hydrogen channel), a titanium microelectrode was deposited on the glass substrate using a standard evaporation/lift-off process as a thickness of 100 nm and then platinum nanoparticles were electrodeposited on the titanium microelectrode52. Subsequently, the Nafion- and microelectrode-patterned glass was irreversibly bonded to connect the above-mentioned two PDMS microchannels at a designated position using an oxygen plasma bonder (Femto Science, Korea).

The scaled-up device for freshwater and hydrogen production was fabricated mainly using a 3D printer. As shown in the schematics of Fig. 3a, 3b, the 3D-printed mesoscale device consists of a purification chamber with an internal volume of 11 mm × 10 mm × 7 mm and a hydrogen production chamber with an internal volume of 11 mm × 10 mm × 4 mm. The two chambers were bonded using epoxy glue with a sandwiched Nafion sheet (11 mm × 10 mm × 25 μm, Nafion 211 sheet, Chemours, USA). Notably, the internal space in the purification chamber was discretized by fin arrays to create microfluidic environment in the mesofluidic device. The fin played a role not only for stabilizing ICP phenomenon but also enhancing ion transportation46. Each chamber was printed using a commercially available 3D printer (ProJet MJP 2500 Plus by 3D Systems, USA) with resin (VisiJet M2R-CL, 3D Systems) and a supportive material (VisiJet M2 SUP, 3D Systems). To apply external electric power, Pt wires (a diameter of 0.5 mm, 99.95% purity, Made Lab, Korea) were inserted via a through-hole which is placed orthogonal to the flow direction.

Experimental setup and chemicals

For the microfluidic device, two electrolyte solution of NaCl as saltwater and LiCl (Sigma Aldrich, USA) as rinsing solution were fed into the anodic and cathodic microchannels, respectively, using a syringe pump (PHD 2000, Harvard apparatus, USA). This setup ensured controlled flow rates (150 nL/min in our study) for both solutions into their designated microchannels. NaCl was introduced into the upper channel as a representative electrolyte for saline water, suitable for demonstrating the purification process in this channel. In the lower channel, a rinsing solution was introduced to remove products generated by electrode reactions, as is typical in desalination or electrolysis devices. LiCl was used as the electrolyte for the rinsing water, selected for its different cation (Li+) to facilitate accurate measurement of Na+ ion migration from the upper to the lower channel. Platinum wires were used in pipette tips inserted at the ends of the microchannels in experiments for analyzing the ion concentration of the stream outflowing from each microchannel, while the Pt-deposited microelectrode on the glass substrate was used for the gas bubble formation instead of a Pt wire at the reservoir of the hydrogen channel. An external electric power was applied across the Nafion membrane using a source measurement unit (Keithley 2612B, Tektronix, USA).

To confirm proper formation of the ion depletion zone in the microfluidic channel, pH insensitive fluorescent dye (1 µM, Alexa Fluor 488 (Sigma Aldrich, m.w. 643.41 g/mol)) was added in NaCl solution. The ion depletion boundaries were imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope (IX73, Olympus) and captured using CellSens software. Due to the microfluidic instability near the Nafion membrane in this ICP phenomenon25, the IDZ can expand or contract even under a constant current or voltage. In the microfluidic experiments, the simultaneous production was carried out by adjusting the applied current while continuously monitoring the boundary of the IDZ, which appears with the fluorescent dye, to ensure effective water purification. Although it is also possible to control the IDZ by adjusting the flow rate of the feed solution, in this experiment, the flow rate was kept constant, and only the applied voltage was adjusted. During the application of electricity across the CEM, the average current applied for each feed concentration was 3.9, 7.2, 14.9, 86.0, and 135.9 µA for concentrations of 10, 20, 40, 200, and 500 mM, respectively. When adjusting the current in this way, the voltage ranged between 100 and 200 V, due to the high resistance resulting from the small cross-sectional area (approximately ~200 µm²) of the Nafion membrane in the microsystem.

Sample analysis methods

The concentrations of collected cations at each reservoir were analyzed using ion chromatography (ICS-3000, Dionex, USA). Due to the nature of the microsystem, water evaporation from the reservoir significantly affects ion concentration analysis. To address this issue, a 10 μL aqueous solution of 2 mM KCl (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), which is a different composition from any of inlet solution (i.e., NaCl or LiCl), was injected into each outlet reservoir of the microchannel before the device operation. Potassium ions were used as a concentration reference to correct for ion concentration variations caused by water evaporation, since the number of moles of potassium ions remains constant despite the feeding of each stream into the reservoir or water evaporation21. By using the unchanging number of moles of K+ ion, we estimated the final volume in each reservoir after 1 h of electricity application and calculated the Na+ ion concentration of each stream. To track the pH changes due to hydrogen production in situ, a universal pH indicator (10%, UI-100, Micro Essential, USA) was mixed with each solution. Furthermore, we checked the pH values of the collected solution at the reservoir of hydrogen microchannel using a pH meter (Orion Star A215, Thermo Scientific) with a microprobe (Orion 9810 N, Thermo Scientific). In this experiment using the pH meter, the reservoir of the hydrogen microchannel initially contained a 10 μL aqueous solution of 2 mM KCl, which was further filled with the outflow of 10 mM LiCl containing the cathodic reaction products at a flow rate of 150 nL/min.

To provide a quantitative hydrogen production result, we utilized the mesoscale devices fabricated with a 3D printer, as mentioned above, because we were unable to quantitatively measure the hydrogen gas production within the microfluidic device, since the gas volume produced (on the nL scale) was too small to reach the detection limit of GC. In the mesoscale device, the volume of hydrogen produced was on the mL scale, allowing for the quantitative measurement of hydrogen production with a GC (YL 6500 GC, Carboxen 100 column, thermal conductivity detector, Young In Chromass Co., Ltd.). Using this mesoscale device, we fed an NaCl solution into the purification chamber and a LiCl solution into the hydrogen production chamber at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min using a syringe pump. The NaCl and LiCl solutions used here were purged with argon gas before being introduced into the system. This step was taken because any oxygen molecules present in the solutions, previously exposed to air, could interfere with hydrogen production at the cathode, as the reduction potential of oxygen is lower than that of hydrogen ions35. During the application of electricity through the Pt wire electrodes, the outflows of each stream, containing electrolyte solution and produced gas, were collected in gas-tight syringes of appropriate volume. Then, the ion concentration of the collected sample was analyzed using an IC, and the hydrogen production was quantitatively measured using a GC. Additionally, pH values of the hydrogen chamber were measured with a pH meter with a microprobe used in the microfluidic platform. For the analysis of ion concentration and pH values, the solutions collected from the brine and purified water compartments were used as-is from the collection syringe. However, in the hydrogen chamber, additional inflow water was used to push out hydrogen gas bubbles trapped within the device for accurate hydrogen gas analysis. Consequently, the ion concentration in the hydrogen chamber was analyzed after thoroughly mixing the inflow water with the solution collected in the syringe after the reaction. Using the measured Na+ concentration and the volume of each solution, we calculated the number of moles of Na+ ions of each solution.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. (Prof. Sung Jae Kim) gates@snu.ac.kr

References

Megía, P. J., Vizcaíno, A. J., Calles, J. A. & Carrero, A. Hydrogen production technologies: from fossil fuels toward renewable sources. A mini review. Energy Fuels 35, 16403–16415 (2021).

Chatenet, M. et al. Water electrolysis: from textbook knowledge to the latest scientific strategies and industrial developments. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 4583–4762 (2022).

Liu, R.-T. et al. Recent advances in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 5652–5683 (2023).

Miller, H. A. et al. Green hydrogen from anion exchange membrane water electrolysis: a review of recent developments in critical materials and operating conditions. Sustain. Energy Fuels 4, 2114–2133 (2020).

Tanaka, Y. Ion-Exchange Membrane Electrodialysis for Saline Water Desalination and Its Application to Seawater Concentration. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 50, 7494–7503 (2011).

Al-Amshawee, S. et al. Electrodialysis desalination for water and wastewater: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 380, 122231 (2020).

Ahmed, F. E., Khalil, A. & Hilal, N. Emerging desalination technologies: Current status, challenges and future trends. Desalination 517, 115183 (2021).

Kim, S., Piao, G., Han, D. S., Shon, H. K. & Park, H. Solar desalination coupled with water remediation and molecular hydrogen production: a novel solar water-energy nexus. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 344–353 (2018).

Kim, B. -j, Shon, H. K., Han, D. S. & Park, H. In-situ desalination-coupled electrolysis with concurrent one-step-synthesis of value-added chemicals. Desalination 551, 116431 (2023).

Kim, S. J., Ko, S. H., Kang, K. H. & Han, J. Direct seawater desalination by ion concentration polarization. Nat. Nanotech 5, 297–301 (2010).

Kim, S. J., Wang, Y.-C., Lee, J. H., Jang, H. & Han, J. Concentration polarization and nonlinear electrokinetic flow near a nanofluidic channel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 044501 (2007).

Kim, B. et al. Purification of high salinity brine by multi-stage ion concentration polarization desalination. Sci. Rep. 6, 31850 (2016).

Kwak, R., Pham, V. S., Kim, B., Chen, L. & Han, J. Enhanced salt removal by unipolar ion conduction in ion concentration polarization desalination. Sci. Rep. 6, 25349 (2016).

Kim, W. et al. Scalable ion concentration polarization dialyzer for peritoneal dialysate regeneration. J. Nanobiotechnol. 23, 255 (2025).

Patterson, C. L. & Adams, J. Q. Emergency response planning to reduce the impact of contaminated drinking water during natural disasters. Front. Earth Sci. 5, 341–349 (2011).

Loo, S.-L., Fane, A. G., Krantz, W. B. & Lim, T.-T. Emergency water supply: a review of potential technologies and selection criteria. Water Res. 46, 3125–3151 (2012).

Hur, A. Y., Page, M. A., Guest, J. S. & Ploschke, C. M. Financial analysis of decentralized water reuse systems in mission critical facilities at US Army installations. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 10, 603–613 (2024).

Rubel, J., Buysschaert, F. & Vandeginste, V. Review and selection methodology for water treatment systems in mobile encampments for military applications. Clean. Water 3, 100065 (2025).

French, M. & Lange, K. Water Recovery Trades for Long-Duration Space Missions.). 49th International Conference on Environmental Systems (2019).

Etlin, S. et al. Enhanced astronaut hygiene and mission efficiency: a novel approach to in-suit waste management and water recovery in spacewalks. Front. Space Technol. 5, 1391200 (2024).

Kim, W., Park, S., Kim, K. & Kim, S. J. Experimental verification of simultaneous desalting and molecular preconcentration by ion concentration polarization. Lab Chip 17, 3841–3850 (2017).

Luo, T., Abdu, S. & Wessling, M. Selectivity of ion exchange membranes: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 555, 429–454 (2018).

Kusoglu, A. & Weber, A. Z. New Insights into Perfluorinated Sulfonic-Acid Ionomers. Chem. Rev. 117, 987–1104 (2017).

Mauritz, K. A. & Moore, R. B. State of Understanding of Nafion. Chem. Rev. 104, 4535–4586 (2004).

Dydek, E. V. et al. Overlimiting Current in a Microchannel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 118301 (2011).

Seo, J., Ha, S. & Kim, S. J. Investigation of Operational Parameters for Nanoelectrokinetic Purification and Preconcentration. Langmuir 40, 16443–16453 (2024).

Seo, M., Park, S., Ryu, J. & Kim, S. J. Adhesive lift method for patterning arbitrary-shaped thin ion-selective films in micro/nanofluidic device. Lab on a Chip 22, 1723–1735 (2022).

Simons, R. Water splitting in ion exchange membranes. Electrochim. Acta 30, 275–282 (1985).

Nikonenko, V. V. et al. Desalination at overlimiting currents: State-of-the-art and perspectives. Desalination 342, 85–106 (2014).

Nikonenko, V. V. et al. Intensive current transfer in membrane systems: Modelling, mechanisms and application in electrodialysis. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 160, 101–123 (2010).

Simons, R. Strong electric field effects on proton transfer between membrane-bound amines and water. Nature 280, 824–826 (1979).

Simons, R. Electric field effects on proton transfer between ionizable groups and water in ion exchange membranes. Electrochim. Acta 29, 151–158 (1984).

Kharkats, Y. I. & Sokirko, A. V. Theory of the effect of migration current exaltation taking into account dissociation-recombination reactions. J. Electroanal. Chem. Inter. Electrochem 303, 27–44 (1991).

Nikonenko, V., Urtenov, M., Mareev, S. & Pourcelly, G. Mathematical modeling of the effect of water splitting on ion transfer in the depleted diffusion layer near an ion-exchange membrane. Membranes 10, 22 (2020).

Dresp, S., Dionigi, F., Klingenhof, M. & Strasser, P. Direct Electrolytic Splitting of Seawater: Opportunities and Challenges. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 933–942 (2019).

Druzgalski, C. & Mani, A. Statistical analysis of electroconvection near an ion-selective membrane in the highly chaotic regime. Phys. Rev. Fluids 1, 073601 (2016).

Druzgalski, C. L., Andersen, M. B. & Mani, A. Direct numerical simulation of electroconvective instability and hydrodynamic chaos near an ion-selective surface. Phys. Fluids 25, 110804 (2013).

Rubinstein, I. & Zaltzman, B. Electro-osmotically induced convection at a permselective membrane. Phys. Rev. E 62, 2238 (2000).

Park, J. S., Cho, I., Park, J. & Kim, S. J. Differential Impact of Surface Conduction and Electroosmotic Flow on Ion Transport Enhancement by Microscale Auxiliary Structures. Langmuir 40, 10098–10106 (2024).

Seo, M., Kim, W., Lee, H. & Kim, S. J. Non-negligible effects of reinforcing structures inside ion exchange membrane on stabilization of electroconvective vortices. Desalination 538, 115902 (2022).

Lee, H. et al. Overlimiting Current in Nonuniform Arrays of Microchannels: Recirculating Flow and Anticrystallization. Nano Lett. 21, 5438–5446 (2021).

Lee, D., Choi, D., Park, H., Lee, H. & Kim, S. J. Electroconvective circulating flows by asymmetric Coulombic force distribution in multiscale porous membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 636, 119286 (2021).

Kim, S. et al. Electrokinetic-Driven Fast Ion Delivery for Reversible Aqueous Zinc Metal Batteries with High Capacity. Small 17, 2008059 (2021).

Huh, K. et al. Surface conduction and electroosmotic flow around charged dielectric pillar arrays in microchannels. Lab Chip 20, 675–686 (2020).

Kim, W., Oh, J., Kwon, S., Kim, K. & Kim, S. J. Quantifying the pH shift induced by selective anodic electrochemical reactions in the ion concentration polarization phenomenon. Lab on a Chip 19, 1359–1369 (2019).

Kim, K., Kim, W., Lee, H. & Kim, S. J. Stabilization of ion concentration polarization layer using micro fin structure for high-throughput applications. Nanoscale 9, 3466–3475 (2017).

Nam, S. et al. Experimental Verification of Overlimiting Current by Surface Conduction and Electro-Osmotic Flow in Microchannels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 114501 (2015).

Park, H. et al. Enhancement of Overlimiting Current in a Three-Dimensional Hierarchical Micro/Nanofluidic System by Non-uniform Compartmentalization. BioChip J. 18, 505–519 (2024).

Cho, I. et al. Non-negligible diffusio-osmosis inside an ion concentration polarization layer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 254501 (2016).

Kienitz, B. L., Baskaran, H. & Zawodzinski, T. A. Modeling the steady-state effects of cationic contamination on polymer electrolyte membranes. Electrochim. Acta 54, 1671–1679 (2009).

Seo, J. et al. In operando spatiotemporal analysis of ion concentration profile using ion-selective membrane probes in electrokinetic systems. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 437, 137737 (2025).

O’Neil, G. D., Christian, C. D., Brown, D. E. & Esposito, D. V. Hydrogen Production with a Simple and Scalable Membraneless Electrolyzer. J. Electrochem Soc. 163, F3012 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work is mainly supported by the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2023-00302600). H. Lee was partially supported by NRF-2020R1C1C1013689. Also, this work is also supported by BK21 PLUS program, Mid-Career Bridging Program and Carbon Neutral Campus Initiative, 2025 Hyper-Convergence Research Support Program (0681-20250036) at Seoul National University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jihee Park: Methodology, Experimental investigation, Writing – original draft. Sehyuk Yoon: Methodology, Experimental investigation, Writing – original draft. Myeonghyeon Cho: Writing – review & editing. Donggeun Eom: Methodology. Beomjoon Kim: Writing – review & editing. Hyomin Lee: Writing – review & editing. Wonseok Kim: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Sangwook Park: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Sungjae Ha: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Sung Jae Kim: Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J., Yoon, S., Cho, M. et al. Energy-efficient modular water purification system via concurrent freshwater and hydrogen generation using ion concentration polarization. Commun Mater 6, 275 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01001-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01001-z