Abstract

Due to its broadband optical absorption and advancement in wafer-based processing technology, silicon is extensively employed in photovoltaic devices. However, the application of silicon for photoelectrochemical reactions in its wafer/bulk form is limited and has consistently demonstrated inadequate photoelectrochemical performance. This Review offers a critical summary on light-induced H2 production, CO2 reduction, NH3 formation via nitrate or N2 reduction and biomass valorization using silicon nanostructures. In these photoelectrochemical applications, how nanostructuring of silicon and tuning its optoelectronic/surface properties impact the performance is emphasized. Elucidating such a comprehensive correlation offers key insights into harnessing the true potential of silicon as a photoelectrode towards solar fuel production. In addition, emerging opportunities and strategies in designing silicon nanostructures-based photoelectrodes for light-driven single-atom catalysis and overall water splitting reactions are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Considering the ever-increasing global demand for energy and associated carbon footprint, utilizing clean and green energy sources is crucial. In this direction, sustainable fuel production via the photocatalysis approach using abundantly available sunlight is a promising approach. In such a process, upon light absorption, the photocatalyst (semiconductor) generates holes and electrons in the valence and conduction bands, respectively. These charge carriers are separated and migrate to the surface of the photocatalyst, where they are used in various reactions such as water splitting, CO2 reduction, N2 reduction, and biomass valorization1. Analogous to photocatalysis, the photoelectrochemical (PEC) approach is also extensively investigated for solar fuel production. Honda and Fujishima first demonstrated the water splitting reaction using TiO2 via the PEC approach in 19722. This discovery paved the way to develop efficient light-absorbing semiconductor-based photoelectrodes to drive various reactions that are of immense importance to achieve sustainability.

In a typical three-electrode PEC cell, as illustrated in Fig. 1a, light-absorbing semiconductor serves as the working photoelectrode. A reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) or an Ag/AgCl or a standard calomel electrode is typically used as the reference electrode, while platinum wire/mesh is commonly used as a counter electrode. Upon light illumination, the semiconductor generates charge carriers that are separated and transferred to the counter electrode using an external potential to facilitate a redox reaction. A n-type semiconductor acts as a photoanode promoting oxidation reactions, such as the O2 evolution reaction (OER) and glycerol oxidation. While a p-type semiconductor facilitates reduction reactions, such as H2 evolution, CO2 reduction, and N2 reduction reactions, resulting in a photocathodic response.

a A schematic representation of a three-electrode PEC cell. WE working electrode, CE counter electrode, RE reference electrode. Current vs. potential plots comparing b Electrochemical (EC) and PEC H2 evolution reaction (HER) and c EC and PEC OER. d Overlay of the solar spectrum and optical absorption spectra of polished thin Si wafer, g-C3N4, and Ta3N5, all measured in diffuse reflection mode using an integrating sphere. The theoretical maximum solar-to-hydrogen (STH) energy conversion efficiency is mentioned above the spectral overlay. e Potential applications of Si nanostructures for various PEC reactions.

Unlike a pure photocatalytic system, application of mild external bias along with incident light in a typical PEC reaction plays a crucial role in improving charge separation, transport, and importantly, in selectivity of the reaction. As shown in Fig. 1b, c, the PEC reactions demonstrate a significant shift in onset potential and an increase in current density compared to EC reactions. For the PEC HER, the onset potential shifts to a more positive potential, indicating that less energy is required to drive the reaction (Fig. 1b). Similarly, for the PEC OER, the onset potential shifts to a lower potential compared to EC OER (Fig. 1c). In PEC reactions, the performance is usually evaluated using various efficiency metrics. One such metric is Faradaic efficiency, which refers to the percentage of electrons utilized during the PEC reaction of interest to form a product, with respect to the total amount of charges passed during the reaction3. Additionally, when an external bias is applied in PEC HER, the applied bias photon-to-current efficiency (ABPE) is employed. ABPE determines the efficiency of conversion of incident solar energy into chemical energy at a specific applied voltage. The incident photon-to-current efficiency (IPCE) measures the wavelength-dependent conversion of incident photons into photocurrent4.

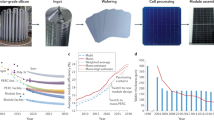

The choice of semiconductor utilized in a PEC reaction plays a crucial role in determining its efficiency. To enhance the efficiency of a PEC reaction, it is essential for the photoelectrode to absorb a wider part of the incoming sunlight. In addition, to further reduce the cost of solar fuel production, it is desirable to develop earth-abundant photoelectrodes. Over the last five decades, several classes of photoelectrodes like metal oxides, sulfides, nitrides, and metal oxyhalides have been developed to drive a range of PEC reactions5,6. However, to demonstrate scalable and efficient solar fuel production, utilization of a broadband light-absorbing photoelectrode is critical. Due to its abundance, tunability, and broad light absorption, silicon (Si) is a promising candidate for PEC applications7. With a 1.1 eV optical band gap, Si can harness over 65% of solar light to drive PEC reactions8. Figure 1d compares the solar spectrum with optical absorption spectra of Si wafer, g-C3N4, and Ta3N5 photocatalysts. The ability of Si to absorb light up to 1100 nm makes it an ideal photoelectrode for various PEC applications, shown in Fig. 1e.

Note that a given PEC reaction is thermodynamically feasible only when the band edges of Si align with respect to the reduction or oxidation potentials of reactants. For the photocathodic reaction, the conduction band (CB) edge of Si must be at a more negative potential than the reduction potential. While for the photoanodic reaction, the valence band (VB) edge must be located at a more positive potential than the oxidation potential. As a result, a photogenerated electron can be transferred from the CB to a chemical species with an energy high enough (also called overpotential) to activate it. Respectively, chemical species can be oxidized by the photogenerated holes in the VB. Both the energies of the electrons and the holes are referenced with respect to the Fermi level (EF). This concept is illustrated in Fig. 2a–c and explained as follows. When p-Si is immersed in an electrolyte, its EF must align with the redox potential of the electrolyte to reach equilibrium. Since EF of p-Si is lower than that of H+/H2 redox couple (Fig. 2a), charge carriers are transferred from the electrolyte to p-Si. This leads to the formation of a space-charge region at the surface of p-Si, resulting in a downward band bending (Fig. 2b). Upon illumination, the photoexcited charge carriers are generated as shown in Fig. 2c. The accumulation of photoexcited electrons at the surface of p-Si partially neutralizes the space-charge region, thereby reducing the steepness of band bending. Under this condition, the EF splits into two quasi-Fermi levels, EF,p and EF,n, and the potential difference between these two levels is the maximum photovoltage (VOC) that can be generated by p-Si. A similar but opposite trend will be expected for n-Si that drives photoanodic reactions.

Band diagrams of p-Si/electrolyte interface a before equilibrium, b after equilibrium, and c under illumination. VB valence band, CB conduction band, EF Fermi level, EF,p and EF,n quasi-Fermi levels, VOC Photovoltage. d Band diagram of intrinsic Si at equilibrium with respect to redox potential of various PEC reactions. e Statistics from the Web of Science database on the number of publications related to Si over the last decade. The keywords used for the search were “Silicon + solar cells” and “Silicon + photoelectrochemical”.

The redox potentials of the various PEC reactions with respect to the band edge levels of Si are illustrated in Fig. 2d. If we consider a proton as the chemical species, the potential for reduction of protons to H2 (H+/H2), requiring two electrons, is 0 V vs. RHE. Similarly, the redox potential for the CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) to CO is −0.11 V vs. RHE9. Albeit smaller, the energy of a photogenerated electron is still high enough to activate CO2. Conversely, the reduction potential for N2 to ammonia (NH3) is +0.092 V vs. RHE10 compared to HER. However, the electrochemical reduction of N2 to NH3 is a multistep process involving the transfer of six electrons, leading to a more sluggish reaction kinetics than HER.

The pH of the electrolyte also plays a crucial role in determining PEC performance and stability. In a strong acidic or alkaline electrolyte, increased ionic conductivity enhances photocurrent density and reduces ohmic losses11. However, these conditions can degrade the Si-based photoelectrodes, affecting their stability in PEC reactions. Alternatively, neutral electrolytes aid in enhanced stability but suffer from poor charge kinetics due to the lower concentration of H+/OH−. In CO2 conversion reactions, the pH of the electrolyte also influences the selectivity of the products12.

With steady advancements in wafer-based processing technology13, Si is extensively employed in photovoltaic devices and is deployed at scale with efficient light-to-electrical conversion efficiency. However, the implementation of Si in PEC reactions and research related to solar fuels production is inadequate. This notion agrees with noticing at least ten times fewer publications in the last decade for PEC research compared to solar cells (Fig. 2e). Considering the unity quantum efficiency, ≈45% STH energy conversion efficiency14 is theoretically expected for Si (Fig. 1d), which is significantly higher than typical electrolyzers15. However, the experimentally obtained STH energy conversion efficiency for Si is still below 0.1%16, which indicates significant loss processes involved in converting solar-to-chemical energy. At the same time, it shows the gap in tailoring the Si nanostructures for enhancing the efficiency of PEC reactions.

While acknowledging earlier seminal Review articles17,18,19,20,21, our Review presents a comprehensive understanding of the key parameters, design principles, and emerging nanostructures with the aim to enhance the solar-to-chemical energy conversion efficiency using Si. Besides focusing on Si nanostructures for HER, we highlight its recent applications and significant developments related to CO2RR, NH3 production, and biomass valorization. In all these reactions, fundamental insights into how optoelectronic and surface modifications enhanced the PEC performance from both thermodynamics and kinetics perspectives are provided. Most of the earlier reports in PEC reactions employed Si in its nanowire (NW) configuration. Hence, we emphasize on alternate cost-effective Si configurations such as nanoporous Si, amorphous Si, silicene, silicide, and Si quantum dots, beyond extensively studied Si NWs for PEC applications. In addition, promising but to be extensively employed applications of Si via the PEC approach are explained. For example, utilizing Si as a substrate for single-atom catalysis (SACs) is discussed in detail, with rational insights into both challenges and approaches to address them effectively are presented. Similarly, we also discuss the design principles for overall water splitting (OWS) using Si p–n junctions. Overall, this Review offers critical insights into opportunities and challenges to effectively utilize Si as a photoelectrode for efficient solar fuel production that will accelerate the transition towards sustainability.

Approaches towards scalable and cost-effective solar fuel production using Si

To utilize the potential of Si as a photoelectrode for scalable and cost-effective solar fuel production, various strategies are employed, as illustrated in Fig. 3. This subsection details how nanostructuring, surface modification, the use of cocatalysts, and doping influence the optoelectronic properties and PEC reaction efficiency of Si.

Planar vs. nanostructured Si: why and how it helps

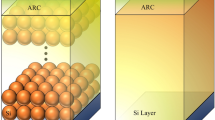

The importance of making Si nanostructures to enhance PEC reaction efficiency can be understood as follows. In planar Si, 25% of the incident photons are reflected at the semiconductor/electrolyte interface, thus reducing the efficiency of photon absorption and subsequent charge carrier generation22. In solar cells, antireflection coatings are typically employed to reduce such reflection losses. However, in the PEC system, such coating layers are difficult to integrate as they affect the charge transfer at the semiconductor/electrolyte interface. Alternatively, controlled Si nanostructures can be fabricated to promote light trapping (reduce reflection loss) and enhance the light absorption capacity of Si22. The efficiency of light trapping, which depends on the aspect ratios of one-dimensional (1D) structures, is typically higher for Si NWs compared to planar Si due to multiple internal light scattering23,24. In addition, due to their high surface area, they offer abundant active sites for reactants to adsorb on the surface of Si nanostructures, which promotes charge transfer. Both parameters are key to enhancing the efficiency of PEC reactions25. This phenomenon can be understood by comparing planar Si and Si NWs, as shown in Fig. 4. Nanostructuring Si was found to reduce the overpotential for PEC H2 production from –0.17 to –0.10 V vs. Ag/AgCl22.

Furthermore, considering the anisotropic nature of vertical NWs, charge carriers can efficiently reach the surface due to the short diffusion length, which is expected to enhance their performance as illustrated in Fig. 425. Similarly, Si nanostructures in different shapes, such as nanoholes26 or nanocones27, also demonstrate decreased reflectivity and thus enhanced light absorption. Consequently, these materials effectively harness solar light and are utilized for various types of PEC reactions.

Quasi-0D Si nanoparticles exhibit a higher surface area than 1D structures, enhancing their catalytic activity due to more active sites25,28. The quantum confinement effect in Si nanocrystals occurs when their size is smaller than the Bohr exciton radius (4.5 nm)29. Porous nanostructures, another class of quasi-0D materials, also offer a high surface area, which is proposed to facilitate charge carrier collection and reduce recombination30. The bandgap of Si nanoparticles is influenced by their size, pore topology, and crystallinity. For instance, 2–4 nm Si quantum dots have bandgaps of 1.5–2.2 eV, while 1–2 nm dots have bandgaps of 2.3–3.5 eV31. Wider bandgaps enable Si nanoparticles to participate in more redox reactions, and multi-reflections caused by pores induce effective light trapping in Si porous nanostructures31.

Among the various Si nanostructures, Si NWs are extensively used for PEC applications, with fewer reports on other nanostructures such as nanoparticles, nanocones, and nanopyramids.

Low-temperature methods to fabricate Si nanostructures

Various experimental tools are available to fabricate different types of Si nanostructures. However, most methods rely on expensive epitaxy-based techniques that demand high vacuum and temperature in a controlled environment. Hence, developing low-temperature, cost-effective methods to efficiently create Si nanostructures is essential. In addition, to further reduce the solar fuel production cost, it is necessary to produce photoelectrodes via a simple and robust route in a cost-effective manner. The following sub-sections outline methods used to fabricate different types of Si NWs.

1D nanostructure arrays are synthesized using a few “top-down” and “bottom-up” strategies32. The Si NWs produced using different techniques have distinct crystal structures and surface features that alter their properties33. Two prominent top-down fabrication techniques for Si NWs are deep reactive ion etching (DRIE) and metal-assisted wet chemical etching (MACE). Both processes rely on wet and dry etching, which offer distinct chemical environments yielding unique surface properties. Simultaneously, the standard method for growing Si NWs on substrates is the vapor–liquid–solid (VLS) process, a bottom-up synthesis approach.

Metal-assisted wet chemical etching (MACE)

Top-down techniques offer tunability and a vast fabrication area to produce NW arrays. Surface roughness of Si wafers in the nanoscale can be controlled by etching with diluted hydrofluoric acid (HF) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), assisted by Au nanoparticles34. Typically, the MACE approach consists of two steps35,36:

-

i.

Deposition of noble metal layer like Ag, Au, Pt, and Pd or its nanoparticles by sputtering, thermal or electronic-beam evaporation, or electroless chemical deposition as depicted in Fig. 5a.

-

ii.

Metal-assisted etching of Si in an HF-and oxidant-filled aqueous mixture solution, as demonstrated in Fig. 5b.

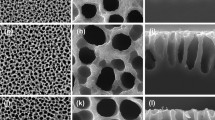

a, b Schematic diagram to produce Si NWs using MACE. SEM images of Si NWs grown on lightly doped c p-Si(100) and d p-Si(111), heavily doped e p-Si(100) and f p-Si(111). Reprinted with permission from ref. 37 Copyright 2008, American Chemical Society.

MACE processes constitute anisotropic etching by metal-catalyzed reactions. Taking an example of a system catalyzed by Ag, the MACE mechanism involves the following reactions and shows the net etching process of Si as in Fig. 5a, b37:

which can be split into two reactions:

Due to the positive electrochemical potential of H2O2 compared to Si38, the oxidation reaction is promoted, subsequently dissolving Si in HF. Then, noble metals function as catalysts to accelerate the reactions occurring at the interface between Si and oxidizing agents. Ag nanoparticles would eventually migrate into the etching pits during the reactions, forming an aligned array of Si NWs as shown in Fig. 5b. The effectiveness and control of this process are affected by the concentration of reactants (AgNO3, H2O2, and HF), the doping level of the Si wafer, the crystallographic plane of Si, and the temperature employed39. The crystallographic plane and doping level, such as lightly and heavily doped p-Si(100) and p-Si(111), have a direct impact on the morphology of Si NWs. The Si NWs grown on heavily doped Si wafers are fine and well separated compared to lightly doped Si. In addition, on p-type (111) wafers, the NWs tilt ~40 °C to the surface37. In contrast, Si NWs on p-type (100) wafers grow vertically along 〈100〉 direction as shown in Fig. 5c–f. By modifying the etching time, reactant concentration, deposition mask, the length, spacing, distribution density, and shape of the Si NWs can be controlled. Consequently, this fabrication process provides a versatile way to create NWs in different shapes40. Overall, the MACE technique can develop Si NWs in an aqueous solution without demanding specialized equipment, thus making it a scalable, affordable, and controllable approach for fabricating various Si nanostructures.

Deep reactive ion etching (DRIE)

With decades of research, DRIE has evolved into a sophisticated fabrication technique since the 1970s41,42. Inductively coupled plasma (ICP)-based Bosch process is usually employed to fabricate Si NWs in the DRIE method43. Typically, to cover Si wafers, a metal, silica-based, or photoresist mask with precise patterns must be designed42. Figure 6 shows the fabrication of Si NWs via DRIE. A photoresist is patterned using photolithography, followed by deposition of Au to protect specified areas during etching. The Si wafer then undergoes alternating cycles of isotropic plasma etching using SF6 and deposition of the passivation layer of C4F8. The passivation layer protects the sidewalls, ensuring vertical etching. After several cycles, the metals and photoresist masks are removed, and Si NWs are created. Overall, DRIE is a good tool for fabricating Si nanostructures. The diameters and lengths of these NWs can be tuned by using mask patterns. This process produces highly ordered Si NW arrays with rough sidewalls and larger diameters compared to MACE or VLS techniques, and can be made scalable too.

Vapor–liquid–solid (VLS) process

Wagner and Ellis first produced 1D crystalline Si nanostructures using the VLS process in 196444. The growth mechanism for the VLS approach is depicted in Fig. 7. In this process, metal nanoparticles such as Au are deposited on the Si wafers (Fig. 7a), which forms a small droplet of liquid alloy with Si (Fig. 7b) upon heating. This droplet serves as a catalyst for reactions as well and is an energetically preferred site for hosting Si atoms from the precursor gas, typically silane (SiH4). The supersaturation of Si in Au–Si alloy causes axial crystal development of Si and the precipitation of the components on the liquid-solid interface (Fig. 7c). As a result of nucleation, 1D nanostructures are formed from the crystalline Si phase (Fig. 7d).

The VLS technique allows for including different types of dopants into the Si NWs during their growth by co-adding phosphine or borane gas, in addition to silane45. This method leads to the formation of Si nanostructures with axial or radial p-n junctions46,47. Figure 8 shows one such creation of a heavily doped p-region (deduced from secondary ion mass spectrometry) that resulted in forming an internal electric field, facilitating charge carrier separation and prolonging carrier lifetime. Control over the diameter, density, length, location, doping characteristics, and crystal orientation of Si NWs in the VLS technique offers a variety of applications in semiconductor devices and catalysis.

Calculated radial distribution of the electrical field in n-type doped Si NWs grown, based on the phosphorus doping profile shown in the inset. Reprinted with permission from ref. 160 Copyright 2011, IOP Publishing Ltd.

A summary of the low-temperature methods to fabricate Si NWs is detailed in Table 1. Key advantages and prospects of MACE, DRIE, and VLS techniques are compared.

Other synthesis methods of Si nanostructures

Compared to Si NWs, Si nanoparticles are easier to synthesize as they do not require patterning or the use of catalysts. These quasi-0D nanomaterials exhibit a wide range of unpredictable exposed crystal faces. The simplest technique for producing Si nanoparticles devoid of chemical reactions is the high-energy ball milling technique48,49. Other techniques, such as the nonthermal plasma method50, thermal reduction51, and low-temperature molten salt process52, are also used for the synthesis of Si nanoparticles. Additionally, Si quantum dots can be produced via electrochemical etching53, microwave method54, and colloidal approach55. The hollow and porous Si nanostructures made by physicochemical methods are another distinct class of quasi-0D nanostructures that offer more active sites than nanoparticles due to their high surface area.

Importance of tuning optoelectronic and surface properties of Si to enhance PEC reaction efficiency

Tuning the surface properties of Si nanostructures

In a Si crystal, four covalent bonds are formed by Si atoms, resulting in a tetrahedral coordination. To decrease the Si crystal to the nanoscale, a few of these covalent bonds must be broken, leaving dangling bonds on the surface. To reduce surface energy and the number of dangling bonds, Si atoms covalently bond with other atoms, enabling surface modifications56. Si nanostructures, having a high specific surface area, possess more dangling bonds, leading to more opportunities for surface modification. Though Si is a comparatively stable material, the exposed and unsaturated dangling bonds contribute to its increased reactivity57. Typically, Si is susceptible to surface oxidation, leading to the formation of a thin oxide layer, even in wafer form. Upon making nanostructures with a high surface area, Si is highly prone to undergo surface oxidation. This insulating layer significantly impedes the efficiency of the interfacial charge transfer process58, which is crucial for achieving high PEC performance. To remove the surface oxide layer on Si nanostructures, HF treatment is widely employed, which leads to the formation of comparatively stable Si–H bonds, essentially hydrogen-terminating the Si surface. The HF-treated Si surfaces or bare Si surfaces reacting with strong substituents are functionalized to produce modified surfaces like halogenated or alkylated surfaces. Methyl-terminated Si NWs synthesized using a bi-step process consisting of chlorination and alkylation showed high atmospheric stability, improved carrier mobility, and limited surface deformations59. Hydrosilylation reactions are the most widely used methods for the surface modification of Si nanostructures by the addition of alkyl groups. H-terminated Si nanostructures would also undergo direct reaction with amines to produce a covalent Si–nitrogen linkage or with organolithiums to give a Si–lithium and a Si–alkyl termination. The surface modifications also influence the optical nature of Si nanostructures. The surface modifications with oxide and polar groups such as diol, epoxy, and amine red shift the emission of Si quantum dots60,61. Hence, different surface ligands such as Si–hydride, Si–hydroxide, Si–O–Si, Si–amine, Si–alkyl, and Si–halogen are used to tune the optical and chemical properties of Si nanostructures.

Recently, hydrogen-terminated porous Si was used as a support for immobilizing Re and Mn-based molecular catalysts for PEC reactions62,63. As shown in Fig. 9a, porous Si offers a high surface area compared to planar Si, leading to a higher number of active sites, consequently enhancing the performance. The process in Fig. 9b describes binding of such molecular catalysts with porous Si via hydrosilylation of alkene group of the Re complex that converts Si–H bonds of p-type porous silicon (H-porSi) to Si–C (Fig. 9b). The immobilized Re compound on H-porSi photocathode demonstrated remarkably high 90% Faradaic efficiency for PEC conversion of CO2 to CO. Despite these prospects and promising advantages of H-porSi, it has some challenges to address, such as (i) the hydrosilylation process requires the presence of alkene groups in the catalyst and involves high temperatures (160 °C) and (ii) during CO2RR, the Si–H bonds in H-porSi participate in HER, producing significant amount of H2. To address these issues, the H-porSi was passivated using a SiOx layer by thermal oxidation in air and further utilized for PEC conversion of CO2 to formate (Fig. 9c). Mn-based molecular catalysts containing silatrane moieties were immobilized onto SiOx-porous Si via hydrolysis. This photocathode was relatively stable under ambient conditions and exhibited higher selectivity to formate with a photocurrent density of ~0.6 mA/cm2. Nevertheless, in PEC applications, H-terminated Si nanostructures remain prone to photocorrosion and oxidation in aqueous electrolytes, compromising long-term stability. Although methyl-terminated Si NWs offer improved stability in aqueous electrolytes due to their Si–C bond, it is still susceptible to degradation over extended periods64. Therefore, further research in improving the stability of surface-modified Si nanostructures is essential to advance their applications in PEC reactions.

a Prospects of porous Si substrate over planar Si for immobilization of molecular CO2RR catalysts. b Immobilizing Re-based molecular catalysts over H-porSi via thermal hydrosilylation, and c molecular Mn catalysts containing silatrane groups attached onto SiO2-porous Si for PEC CO2RR to formate. Adapted with permission from ref. 62 Copyright 2025, Elsevier.

Role of cocatalysts in PEC reactions

Cocatalysts and other surface modifications are used for surface passivation of Si nanostructures65. Depositing/coating a cocatalyst on the surface of Si provides active sites, facilitating interfacial charge transfer (redox) reactions, either due to the formation of a Schottky junction or a type-II heterojunction. In addition, surface passivation by depositing metal oxide thin films of materials like metal oxides and other charge-selective n- and p-type layers on the surface of Si nanostructures is found to enhance the PEC performance. Such surface modifications must comply with the thermodynamic considerations described as follows: on the photocathode side, the CB edge of the metal oxide layer must satisfy a more negative potential than the reduction potential; on the anode side, its VB edge must be located at a more positive potential than the oxidation potential. For example, TiO2, which is known to stabilize the Si surfaces66, fulfils this condition for the photoexcited electrons, because the CB edge of TiO2 is below the CB edge of Si67. Electrons can therefore accumulate in the TiO2 cathode, whereas the large VB offset blocks the holes from getting transferred to the TiO2 layer68. However, a trade-off must be ensured on TiO2 thickness to ensure efficient extraction of electrons from Si at the Si/TiO2 interface, subsequently to the electrolyte interface, and to avoid surface accumulation of electrons. Moreover, particular care must be taken of the chemical composition of the heterointerfaces, which can induce an upward band bending in the n-doped Si region, inhibiting the electron transfer to the TiO2 layer69. Similar considerations apply for the passivation of Si with NiO that favors photoexcited hole transfer by virtue of thermodynamic driving energy offset at the Si/NiO interface to drive photoanodic reactions70,71.

Figure 10a presents various low-cost wet methods21 and dry methods for depositing cocatalysts. Among the wet techniques, electrodeposition is widely used because it offers control over the thickness, selectivity, composition, and morphology by tuning deposition parameters such as pH, temperature, and applied potential and current21. Recently, CoS was deposited onto the Si NWs via the electrodeposition method72. Before deposition of CoS, Au nanoparticles were loaded onto Si NWs to increase conductivity and facilitate electrodeposition. During the process, electrons from the Si NWs are transferred to Au, thus depositing CoS. Thiourea, being the source of sulfur, reacts with reduced OH– on the Si NWs/Au surface to produce S2–, which then combines with Co2+ in the electrolyte to form CoS as depicted in Fig. 10b. The deposited Au nanoparticles increase the light absorption of Si NWs via localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect and promote charge transport from Si NWs to CoS. The electrodeposited CoS provides sufficient active sites for HER. The fabricated Si NW/Au/CoS photocathode exhibited a photocurrent density of –33.1 mA cm–2 at 0 V vs. RHE, a 3300 times increase compared to bare Si NWs (–0.01 mA cm–2). Other co-catalysts, such as MoS2, Ni3S272, and NiCoSex73, were also deposited using a similar approach, which exhibited enhanced PEC performance. Alternatively, synthesized co-catalysts can be drop-casted onto the Si nanostructures. Various materials, such as graphene quantum sheet74, Ag nanoparticles75, and carbon nanorods encapsulated Bi nanoparticles76, are drop-casted onto Si NWs, further increasing their PEC reaction efficiency. In addition to these methods, other wet techniques such as spin coating77, spray coating78, and dip coating79 are also utilized to deposit cocatalysts onto Si nanostructures.

a Various wet and dry fabrication methods of Si nanostructures-based photoelectrodes. b Electrochemical deposition of CoS on Si NWs for PEC HER. Current density (mA cm–2) is measured at 0 V vs. RHE. Adapted with permission from ref. 72 Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society.

In addition to wet methods, dry deposition techniques such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD)80, magnetron sputtering81, and atomic layer deposition (ALD)82 are also employed to deposit cocatalysts onto Si nanostructures. In a similar approach, carbon nanowires (C NWs) were synthesized on Si NWs via the CVD method, using Cu as a catalyst and a gas mixture of H2 and CH480. Cu vapor from a Cu foil facilitated the growth of C NWs at 1000 °C under a H2/CH4 atmosphere. The resulting C NWs/Si NWs photocathode exhibited a positive shift of 0.20 V vs. RHE in the onset potential for PEC HER compared to bare Si NWs.

Various materials are integrated into Si NWs using the above-mentioned techniques, including MoS383, Ni12P584, TiO285, and Ta3N586. These materials promote charge separation, decrease interfacial charge-transfer resistance, and inhibit the influence of surface defects to enhance the PEC reaction efficiency of Si nanostructures. It is essential for the materials coated to be transparent for light illumination and not hinder the light absorption in Si nanostructures. When wide bandgap semiconductors like TiO2 are coated, they do not interfere with the light absorption of longer wavelengths in Si nanostructures. This is in contrast with visible-light active materials like MoSe2, which hinders the light absorption in Si87. Hence, the thickness of the materials coated on the surface is crucial for efficient PEC performance of Si nanostructures. Molybdenum-based materials are often coated on a Si substrate to enhance their PEC HER efficiency. MoS2 was deposited on Ag core–shell Si shell nanospheres (Ag@Si NSs) via the chemical vapor deposition technique88. The NSs with increased surface area ratio offer more active sites of MoS2 compared to planar Si. As a result, Ag@Si/MoS2 produced three times higher photocurrent density than MoS2 deposited on planar Si. In another report, Si NWs were developed on a porous carbon substrate (PCS), thus optimizing optical absorption89. MoSx was electrodeposited on these Si NWs as an HER electrocatalyst. The substrate also acts as a passivation layer, therefore inhibiting the oxidation of Si. The PCS/Si NW/MoSx demonstrated enhanced photocurrent density of 0.23 mA cm–2 at –0.15 V vs. RHE and anodic shift in onset potential of 0.1 V compared to bare Si NW. MoSx promotes electron transport, thus increasing the PEC reaction efficiency. Furthermore, metal oxides such as In2O3 are coated on Si NWs as a cocatalyst for the OER90. The ultrathin mesoporous In2O3 with high optical transparency was deposited on top of the Si NWs, preliminarily coated with an intermediate TiO2 layer by ALD. The deposition of In2O3 enhances charge separation efficiency, leading to an increased current density of 27 mA cm–2 at 1.23 V vs. RHE, as shown in Fig. 11a.

a Si NW/TiO2/In2O3 photoanode for OER. Current density (mA cm–2) is measured at 1.23 V vs. RHE. Adapted with permission from ref. 90 Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. b Ag nanoparticles embedded into Si nanoholes, leading to the formation of a Schottky junction, are employed for PEC CO2 fixation reaction. Adapted with permission from ref. 92 Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society.

Along with the coating materials on Si nanostructures, various nanoparticles such as Pt91 and Ag92 are also used as cocatalysts. The Pt nanoparticles deposited on Si NWs improved the charge separation and transfer, thus increasing the HER efficiency65. Similarly, Ag nanoparticles were incorporated into Si nanoholes using the MACE technique, as shown in Fig. 11b92. The downward band bending of Si nanoholes forms a Schottky junction between the Ag nanoparticles and Si nanoholes, effectively promoting charge carrier separation. As a result, the photocathode exhibited excellent performance in the PEC carboxylation reaction, achieving high yield rates of 21.05 μmol cm–2 h–1 for 2-phenylpropanoic acid and 34.44 μmol cm–2 h–1 for Ibuprofen.

Role of doping in PEC reactions

Upon light irradiation with energy greater than or equal to the bandgap of Si, photogenerated electrons are excited to the CB, thus forming holes in the VB. The efficient generation of these charge carriers and their separation and transport are crucial in PEC reactions93. Intrinsic Si has higher carrier mobility compared to extrinsic Si, which is significantly higher for photochemical conversion reactions. Whereas extrinsic Si with dopant impurities shows low resistance and high charge carrier concentration, depending on the amount of dopant. Donor impurities create an n-type semiconductor where electrons are the majority carriers, whereas acceptor impurities give a p-type semiconductor with holes as majority carriers. The charge carrier kinetics are crucial to understanding the charge conversion efficiency in semiconductors under light illumination. The majority of carriers mainly influence the photogenerated current in the circuit of PEC cells. Whereas the lifetime, diffusion length, and recombination rate of minority carriers affect the efficiency of the cell94. These factors define the available carriers for photochemical reactions before depleting their energy95. The charge carrier recombination in Si undergoes the Shockley-Read-Hall recombination mechanism, also called trap-assisted recombination. This mechanism explains the recombination via trapped states created within the bandgap of Si upon introducing lattice or surface impurities25. The resistivity of Si directly influences the PEC reaction efficiency96,97. The mobility of charge carriers is reduced due to scattering by dopants in Si98. Furthermore, heavily doped Si has a higher recombination rate and reduced mobility99. Hence, selecting appropriate dopant concentrations is necessary to inhibit the rate of recombination and improve the catalytic efficiency of Si. In this direction, heavily doped Si nanostructures are widely used in PEC applications. As already mentioned, doping significantly shifts the EF of Si. This affects the characteristics of Si in PEC systems since the gap between the vacuum level and the EF is a critical factor for determining interfacial charge transfer. Upon heterojunction formation, electrons move from a low to a high work function area until the EF of the carriers is aligned, and band bending occurs at the interface. Doping further affects the band alignment and bending due to an internal shift of EF in Si. The charge carrier separation is enhanced by band bending and subsequent electric field generation in the space charge region, further promoting the charge carrier diffusion93. The carrier mobility, longer minority charge carrier lifetime, and wide diffusion length are maintained in Si nanostructures with greater surface area compared to bulk Si. Si nanostructures employed with materials such as reduced graphene oxide100 and Pt nanoparticles24,101 further inhibit surface charge recombination.

The energy band diagram of Si in equilibrium and flat-band condition with respect to the redox potential of various PEC reactions is illustrated in Fig. 2d. The band potentials of Si do not straddle the redox potential for the OWS reaction (generating both H2 and O2), and only H2 production is theoretically feasible. Upon modification, p-Si photocathodes and n-Si photoanodes are suitable for HER and OER, respectively, as shown in Fig. 12a and b. The EF of Si nanostructures shares equilibria with the potential of redox couples in the system, which leads to band bending, promoting charge separation and transport in PEC reactions. The increase in the surface area of Si NWs helps in the efficient transport of minority charge carriers towards the surface of the electrode. The junction area determines the minority carrier flux through the electrode/electrolyte junction. A large junction area in Si nanostructures decreases the minority carrier flux through the junction, affecting the onset potential. The surface defects are also proposed to contribute to the anodic shift of the onset potential in Si nanostructures102. The band bending in Si nanostructures is enhanced due to the high surface-to-volume ratio compared to planar Si. Hence, light absorption, band structure engineering for efficient charge separation and transport, and surface/interface engineering are crucial in Si nanostructures to achieve various target reactions. Doping offers an avenue to control the energetics and tune the electronic properties favorably to realize the PEC reaction of interest.

Application of Si nanostructures in PEC reactions

Water splitting reaction

Since the band edges of Si do not straddle with both HER and OER, Si cannot drive the OWS reaction. When Si is exposed to water, it oxidizes and forms an insulating oxide layer on its surface, which competes with water oxidation, limiting the efficiency of OER. When p-Si photocathodes are used for HER in an alkaline medium, the dissolution of Si becomes significant. Hence, it is essential to prevent surface oxidation in Si photoanodes and the dissolution of Si in photocathodes to develop stable and efficient Si electrodes. A range of Si nanostructures, such as NWs103, nanobelts104, nanoholes105, quantum dots106, and nanoporous Si107 are employed as photocathodes for PEC HER. Various metal sulfides88, oxides108, and phosphides109 are used to optimize Si nanostructures to lower the effect of surface passivation. Co2P drop-casted on Si NWs acted as a cocatalyst for HER and as an effective passivation layer for Si NWs, as shown in Fig. 13a109. The Si NW@Co2P photocathode exhibited a photocurrent density of –21.9 mA cm–2 at 0 V vs. RHE, which is two orders of magnitude higher than bare Si NWs. The higher HER efficiency is also attributed to improved charge transfer upon deposition of Co2P. In another study, crystalline TiO2 with graded oxygen defects (b-TiO2) and Pd nanoparticles were deposited on black Si (b-Si) as a protective layer and cocatalyst for HER, respectively108. The oxygen defects in b-TiO2 create a conducting path, thus improving electron transport, and Pd nanoparticles provide active sites for HER as demonstrated in Fig. 13b. The Pd/b-TiO2/b-Si photocathode achieved a photocurrent density of 8.3 mA cm−2 at 0 V vs. RHE and demonstrated stability for over 100 h in both acidic and alkaline electrolytes. In addition to Si NWs, Si QDs are also utilized for the PEC H2 generation reaction. Under light illumination, the undoped Si QDs show anodic response, corresponding to the self-oxidation of Si QDs by photogenerated holes, and electrons are transferred to the back contact106. To overcome this drawback, Si QDs are codoped with B and P, facilitating a cathodic response corresponding to HER. The efficiency of PEC HER predominantly depends on the size of the Si QDs, where larger Si QDs exhibit a stable photocathodic response, suppressing self-oxidation. Recently, Co-based molecular catalyst with o-phenylenediamine as ligand with SO3H group was incorporated into nanoporous p-Si (Nano-p-Si/Co(pda-SO3H)2) for PEC HER107. The molecular catalyst with an electron-withdrawing SO3H group promotes band bending and interfacial charge carrier migration. The modified photocathode demonstrates improved photocurrent density of –14.5 mA cm−2 at 0 V vs. RHE.

a Deposition of Co2P on Si NWs for efficient PEC H2 generation. Current density (mA cm–2) is measured at 0 V vs. RHE. Adapted with permission from ref. 109 Copyright 2018, Springer Nature. b b-TiO2 and Pd nanoparticles deposited on b-Si as a protective layer and cocatalyst for HER, respectively. Current density (mA cm–2) is measured at 0 V vs. RHE. Adapted with permission from ref. 108 Copyright 2018, Springer Nature.

The importance of various cocatalysts and surface modifications and their effect on PEC H2 generation efficiency in Si nanostructures is summarized in Table 2.

Nanostructured core–shell Si–Ta3N5 photoanodes were designed for OER86. The fabrication of the photoanode enabled higher photocurrent due to improved light absorption owing to the light-trapping effect. The efficient charge carrier extraction with enhanced light absorption increased the photocurrent ten times compared to planar counterparts. When CoTiOx was used as an OER cocatalyst, the onset potential was shifted to 0.6 V vs. RHE. Since bare Si cannot drive the OER, incorporating suitable photocatalysts such as Ta3N5 and other cocatalysts helps to facilitate efficient OER.

In the OWS reaction, H2 and O2 are produced in 2:1 stoichiometric ratios, respectively. As discussed in Fig. 2d, the band edges of Si do not straddle between both HER and OER; hence, as such, Si is not capable of driving the OWS reaction. However, OWS using Si forms one of the key processes in solar fuel production; two approaches in this direction are discussed as follows. The Si/TiO2 heterostructure was formed by fabricating TiO2 NWs on top of Si NWs110. Si and TiO2 absorb visible/near-infrared and ultraviolet regions in the solar spectrum, respectively, leading to photogeneration of charge carriers. Due to effective band bending, the photogenerated electrons in Si NWs migrate to the surface to reduce H+ to produce H2, and photogenerated holes in TiO2 produce O2, thus yielding H2 and O2, respectively.

Figure 14 presents an alternate approach to achieve OWS using only Si. The p-Si photocathodes and n-Si photoanodes are used for HER and OER, respectively. The PEC OWS reaction in Si can thus be achieved by using p–n Si junctions. Here, the photogenerated holes and electrons are separated by virtue of the built-in electric field and diffuse to oxidize water molecules and reduce H+ to form O2 and H2, respectively. A photovoltage also arises from the non-equilibrium condition, the EF in the junction being replaced by quasi-Fermi levels that are different for electrons and holes. While targeting the highest current density is key for PEC reaction, the photovoltage produced by the photoelectrode should exceed the sum of the thermodynamically required potential difference of H2O/O2 and H+/H2, i.e., 1.23 V vs. RHE. Considering overpotentials of the anodic and cathodic sides of the p–n junction, a more realistic potential difference is 1.5–1.6 V111. Therefore, as bulk Si with a bandgap of 1.1 eV can theoretically provide a maximum photovoltage of 0.8 V, the photovoltage of a single Si p–n junction is too small for water splitting. But junctions can be added in series to provide sufficient photovoltage and subsequently drive the OWS reaction, as detailed in Fig. 14. It, however, requires the optimization of the current matching between both adjacent p–n junctions with the fabrication of efficient tunnel junctions. Such a careful design of multiple p-type–intrinsic–n-type (p–i–n) junctions grown in a Si NW configuration led to an increasing open-circuit voltage as the number of p–i–n junctions increased, reaching 10 V for 40 junctions in series16. As a result, the photovoltage was much larger than the electrochemical reaction potential required to drive the reaction, and both reactions could proceed simultaneously. Such junction engineering in Si opens the door to other redox reactions which involve photogenerated electrons and holes with high energy, as required, for example, in the methane oxidation by photoexcited holes112.

Recently, OWS was demonstrated using multijunction Si NWs16. A p–i–n superlattice was fabricated in Si NWs. Pt was used as the HER cocatalyst and deposited on n-type, and CoOx was deposited on p-type, which acts as a cocatalyst for OER. HER and OER were observed until 1050 and 940 nm, respectively. The narrow band gap of Si NWs aided in utilizing lower energy photons and increased the photocurrent at longer wavelengths. This multiple-junction configuration is ideal to reach the threshold photovoltage for a specific reaction without the need for an external bias. For example, it can perform bias-free unassisted photocatalytic overall splitting in fresh or seawater. In such a system, the Si NWs coated with cocatalysts are simply suspended in water, which reduces the system cost and limits the photocatalyst corrosion. But they still face a low STH efficiency. One reason is related to the high surface-to-volume ratio of the NWs, giving rise to useless recombination along the NW sidewalls. It therefore calls for the creation of planar multiple Si junctions, where the efficiency and stability of the systems are enabled by spatially and functionally decoupling the light absorption by Si and the surface protection thanks to a metal oxide layer. This strategy is not only worth for standalone and monolithic photocatalysts but could also work for photoelectrodes in a PEC system113. For example, a multijunction Si device, passivated with a metal oxide layer, like TiO2, could be operated as a photocathode reducing water to H2 on its surface, the dark metallic anode connected to the device oxidizing water to O2.

Application of Si nanostructures in CO2RR to CO and other chemicals

The PEC conversion of CO2 into value-added chemicals has gained significant attention, which aids in achieving a zero net carbon footprint. Si nanostructures, drawing inspiration from natural photosynthesis, can be effective light absorbers for PEC CO2 conversion. For efficient CO2 conversion, the photocathodes should selectively reduce CO2, inhibiting the competing HER process. Among the various Si nanostructures, Si NWs deposited with suitable nanoparticles are used for CO2RR. Hence, the morphology of Si and deposition of suitable nanoparticles on Si are crucial for selective CO2RR producing value-added products. Various nanoparticles, such as Sn114, Bi115, and Cu116, have been deposited on Si NWs for efficient CO2RR. Sn nanoparticles deposited on p-type Si NWs efficiently convert CO2 to formic acid and CO, as shown in Fig. 15a114. Sn nanoparticles increased the selectivity for formate production by five times and improved current density compared to Si NWs, as depicted in Fig. 15b. Since a fraction of formate was produced at Pt (counter electrode) in a single cell assembly, to avoid such oxidation reaction, p-Si NWs were separated from the counter electrode via an H-type cell. This system produced formate with an 88% Faradaic efficiency compared to 40% using a single-cell assembly. In another report, Bi and Sn were deposited on p-Si, Bi was loaded as NPs, and Sn was deposited as thin films115. Bi–Sn deposition did not affect the optical absorption of Si NWs, which strongly absorbs in the range of 300–800 nm. The Bi nanoparticles act as active sites for CO2RR, while Sn films prevent the contact between Si and H2O, thus suppressing competing HER. Hence, deposition of Sn enhanced the selectivity towards formate production. Also, Bi–Sn/p-Si creates a suitable energy band structure for efficient charge transport of photogenerated electrons, as illustrated in Fig. 15c. The assembly of Si, Bi, and Sn photocathode facilitates electron migration from Si to Bi, followed by Sn, which reacts with adsorbed CO2 and H2O. Bare Si NWs do not produce formate, whereas Bi–Sn/Si NWs assembly yielded a high formate production rate of 14.25 μmol h–1 cm–2, as shown in Fig. 15d. Recently, 100% selectivity towards CO was achieved by depositing Ni on Si NWs117. The incorporation of the single-atom Ni sites with N-doped C on Si NWs enhances the optical absorption of the photocathode. The Ni-NC/Si NWs achieved nearly 100% Faradaic efficiency of CO production at –0.6 V vs. RHE. The single-atom Ni sites not only act as active sites for CO2RR but also suppress competing HER. Figure 15e shows Cu coordinated covalent triazine framework modified Si NWs (Si@CuCTF6) photocathode with excellent 95.6% selectivity for multi-carbon products (C2+). The porous structure of the triazine framework facilitates CO2 adsorption, and the N atoms in the triazine group and Cu–N sites in the bypyridine units promote C–C coupling. As a result, formate, methanol and C2+ products such as ethanol, acetate, and acetone are efficiently produced via PEC CO2RR at different potentials (Fig. 15f). Various other Si NW assemblies, as mentioned in Table 3, are reported for efficient CO2RR.

a Schematic representation of Sn-coupled p-Si NWs for CO2RR. Reprinted with permission from ref. 114 Copyright 2014, John Wiley and Sons. b PEC formate production efficiency of Sn-coupled p-Si NWs. Adapted with permission from ref. 114 Copyright 2014, John Wiley and Sons. c Proposed band structure and d PEC reaction efficiency of Bi-Sn/Si NWs photocathode for CO2RR. Adapted with permission from ref. 115 Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. e Si@CuCTF6 photocathode for PEC conversion of CO2 to C2+, f The generation rate and selectivity of different products at a range of potentials. Reprinted with permission from ref. 156 Copyright 2024, Institute of Process Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Besides the CO2RR process to form CO, Si nanostructures are also employed for C2–C4 product formation via CO2RR. Upon Cu sensitization, p-type Si NWs were used as a photoelectrode to produce hydrocarbon fuels under visible light, such as CH4, C2H4, and C3–C4 products118. Upon irradiation of light on Si NWs, benzilic acid can be produced through carboxylation reactions involving benzophenone119. Additionally, the integration of Si NWs and [Ni(bpy)2] provides an effective and stereospecific synthetic technique for trisubstituted alkenes from CO2 and alkyne, as illustrated in Fig. 16120. Utilizing CO2 as a source of carbon in such chemical processes is another benefit of the above-mentioned PEC system, as it offers light-driven CO2 conversion to chemicals, a sustainable approach to mitigate the negative effects of CO2 increase.

Mechanism of photoinduced CO2 fixation, proposed by Tan et al. Reprinted with permission from ref. 120 Copyright 2013, John Wiley & Sons.

Application of Si nanostructures in NH3 production

NH3 is one of the most widely produced chemicals, extensively used as a fertilizer and in other industrial applications. Compared to other carbon-intensive processes, the production of NH3 via the nitrogen reduction reaction (N2RR) is a clean and sustainable method. Si nanostructures as photocathodes are gaining a lot of prominence in N2RR. Various Si-based photocathodes, such as Ag/b-Si121, Ni-MoS2/Si NWs122, and Au NP/b-Si/Cr123 are used for PEC N2RR. The b-Si decorated with plasmonic Au acts as an effective photocathode for N2RR. The Au nanoparticles act as active N2 reduction sites. While the holes generated can oxidize Si, an anodic layer of Cr was coated to facilitate the oxidation reaction. Upon coating of Cr, the NH3 production in Au NP/b-Si/Cr increased by two times. Furthermore, this system could generate ammonium sulfate fertilizer when the electrolyte was changed to sodium sulfite as illustrated in Fig. 17a. Since b-Si with a bandgap of 1.12 eV absorbs a broader range of light with enhanced scattering, the NH3 was produced upon visible light illumination (≤800 nm) as shown in Fig. 17b. The optical absorption in the visible region of the solar spectrum and tunable morphology in Si nanostructures offer opportunities for PEC N2 reduction reactions.

a Schematic diagram of Au NP/b-Si/Cr photoelectrochemical cell producing ammonium sulfate and b Quantum efficiency of production of NH3 by Au NP/b-Si/Cr cell as a function of wavelength. Reprinted with permission from ref. 123 Copyright 2016, Springer Nature.

PEC nitrate reduction reaction (NO3RR) to synthesize NH3 is a promising route because of the ease of nitrate source availability (NO3– ions present in hazardous pollutants and wastewater). Unlike N2RR, the NO3RR method can contribute to achieving environmental remediation and convert NO3 into value-added chemicals. Moreover, NO3– ions are highly soluble in water, while N2 has low solubility, and the N = O bond has a lower dissociation energy compared to the high dissociation energy of the N ≡ N triple bond of N2124. For the selective conversion of NO3– to NH3, cocatalysts, such as Au and Cu nanoparticles, are deposited on Si NWs. PEC NO3RR was first demonstrated using hexagonally ordered Si NWs deposited with Au nanoparticles124. The highly ordered Si NWs exhibited better charge transport and reduced recombination compared to planar Si. As a result, Au-deposited Si NWs exhibited a Faradaic efficiency of 95.6% at 0.2 V vs. RHE for NH3 production. Deposition of Cu nanoparticles on Si NWs led to selective photoconversion of NO3– to NH3 with a Faradaic efficiency of 97.03%125. The deposition of Cu nanoparticles facilitated higher band bending at the semiconductor/electrolyte interface, thus suppressing the rate of charge recombination. The high surface area of Si NWs provided more active sites of Cu nanoparticles for NO3– adsorption, which is crucial for selective conversion. Si nanostructures with improved light absorption and high surface area, with suitable cocatalysts, act as efficient photocathodes for selective NO3RR-producing NH3. Other reports on N2RR and NO3RR for NH3 production using Si nanostructures as photocathodes are summarized in Table 4.

Application of Si nanostructures in biomass valorization

Though Si nanostructures have been utilized for water splitting reactions, their application towards light-driven oxidation of abundantly available biomass waste is limited. Biomass oxidation reactions, which also benefit from lower energy requirements than OER126, and yield value-added products, collectively increase the overall efficiency of the water splitting reaction. In addition, developing Si nanostructures for cost-effective biomass conversion into fuel and value-added products offers avenues to realize sustainability.

A high thermodynamic energy requirement of 1.23 V vs. RHE for OER limits the overall efficiency of the PEC reaction during the water splitting reaction. In this direction, alternative resources, such as alcohols, are employed to reduce the operational voltage, thus reducing the cost involved in the PEC OWS reaction. In addition, employing biomass (its derivatives) for the oxidation reaction ameliorates the sluggish kinetics of OER and offers the added advantage of generating value-added products. Glycerol, a biomass waste obtained after biodiesel production, is one such alternate source. Glycerol oxidation reaction (GOR) requires significantly lower potential (0.69 vs. RHE) than 1.23 V vs. RHE required for OER, as depicted in Fig. 18a126. In addition, GOR can also produce various value-added and commercially important raw materials such as dihydroxyacetone and glyceric acid, as shown in Fig. 18b127.

The Si nanostructures can also be used as bifunctional electrodes to realize both reduction and oxidation (redox) reactions. Recently, Si-based photoelectrodes were utilized for PEC CO2RR and GOR128. As presented in Fig. 18c, TiO2 is coated as a passivation layer for the Si photoanode with PtAu clusters acting as catalysts, while perovskite/Cu nanoflower junctions were used as photocathodes. The Si NWs-based photocathode produced glycerate, acetate, lactate, and formate as liquid byproducts of GOR (Fig. 18d). Compared to planar Si, Si NWs-based photoelectrodes produced a higher yield of products and prolonged stability, which was attributed to higher surface area and reduced mass transport limitations. In another study, a Pt–Au-loaded Si NWs was used as a photoanode for GOR with a biophotocathode for CO2RR129. The photochemical diode achieved ~80% Faradaic efficiency for anodic and cathodic products under red light illumination. The Pt-Au/TiO2/Si NWs demonstrated an onset potential of ~0 V vs. RHE for GOR and enhanced photocurrent density compared to planar Si. The bias-free PEC cell yielded a photocurrent density of 1.20 mA cm–2. The overall Faradaic efficiency of anodic products was ~79%, with glyceric acid as the major product and lactic acid, acetic acid, and formate as minor products. When Si NWs in the photoanode were replaced with planar Si, a seven times lower photocurrent density was produced. These results emphasize the role of nanostructuring Si to enhance its performance and demonstrate the potential of Si as a photoanode for biomass valorization.

a Current vs. applied potential graph showing a lower onset potential required for GOR compared to OER. b Selected value-added products that can be formed upon GOR. c Schematic representation of Si NWs-based PEC cell for GOR and CO2RR. d The Faradaic yield of various byproducts with different areas of Cu nanoflowers for GOR. Reprinted with permission from ref. 128 Copyright 2025, Springer Nature.

Employing Si as a substrate (support) for photoinduced SACs reactions

Typically, alumina, silica, and carbon are widely used as support/substrate for different metals like Pt, Pd, Ni in heterogeneous catalytic reactions130,131. However, realizing SACs on a semiconducting substrate via photogenerated electrons and holes is a promising green approach. Earlier attempts in this direction, employing metal oxides and g-C3N4132, yielded poor efficiency due to inadequate light absorption and inefficient charge carrier generation/transport. Here, we highlight the advantageous role of Si as a substrate for SACs and identify its potential applications for future research. In addition, strategies to overcome the challenges involved in the effective utilization of Si for SACs are also elucidated.

Considering broadband absorption, elemental abundance, tunable electronic nature, and a high thermal stability that allows deposition of various types of metals by ex-solution method or solid-state chemical strategy, Si is a promising candidate for SACs and can potentially enhance the efficiency of various types of PEC reactions discussed in earlier sections. This is collectively due to (i) a precise control over the distribution and electronic nature of the metal clusters that can offer unprecedented selectivity, (ii) the absence of shadowing effect, as single-atom catalysts do not reduce the efficiency of light absorption, thus leading to a higher photocurrent density in PEC reactions, and (iii) the potential suppression of surface recombination around single atom catalysts, which enhances the efficiency of photoinduced charge transfer to energetically favorable catalytic sites. Overall, Si could serve as a suitable substrate for SACs in enhancing the efficiency of various PEC reactions. Recently, SACs using Si with cobalt active sites were successfully demonstrated for light-induced syngas production133. By tuning the synthesis conditions, the H2/CO ratio in the produced syngas was enhanced 13 times compared to earlier reports. Though this report is not directly related to PEC reaction, it showed the promise to realize photoinduced SACs and their potential for PEC reactions as well.

In one such recent example, the utilization of Ir on Si for SACs is efficiently demonstrated. In this work, Ir single-atom catalysts were atomically dispersed on Si photoanodes for the PEC water splitting reaction134. The NiO/Ni in Ir SAs/NiO/Ni/ZrO2/n-Si photoanode has intrinsically Ni vacancies, which help in stabilizing single-atom catalysts. The Ir single-atom catalysts effectively decrease the rate of recombination of photogenerated charge carriers and promote charge transport. Figure 19 compares the PEC efficiency of the OER reaction between Ir single-atom catalysts, Ir nanoclusters, and Ir film on Si photoanodes. The Ir single-atom catalysts anchored to the Si photoanode exhibited a photocurrent density of 27.7 mA cm−2 at 1.23 V vs. RHE with a remarkable stability of 130 h for PEC OER.

a Ir single atoms, nanoclusters and film fabricated on n-Si-based photoanodes and their corresponding. b Photoanodic current density for PEC OER measured at 1.23 V vs. RHE. c Chronoamperometry measurements at 1.23 V vs. RHE showing stability of 130 h. Adapted with permission from ref. 134 Copyright 2023, Springer Nature.

In lieu of utilizing metals as single-atom catalysts, single molecular catalysts are immobilized onto Si for PEC applications. Recently, Re63 and Mn-based62 molecular catalysts attached to hydrogen-terminated Si demonstrated efficient CO2RR (Fig. 9) with Faradaic efficiency exceeding 90%. These reports highlight the importance of single-atom catalyst-based Si photoelectrodes for efficient PEC reactions. Unlike the photocatalytic approach, PEC reactions offer bias-assisted selectivity in reaction pathways. Thus, SACs can offer control over reversible changes to the reactive metal catalytic sites that enhance the productivity and selectivity in CO2RR, considering the possibility of forming diverse products due to the different mechanisms/pathways available.

Despite the immense prospects that favor the utilization of Si for SACs in PEC configuration, there are limited reports. This can be attributed to the challenges posed by the Si itself due to its unique properties. Firstly, due to the rapid oxidation of the Si surface, the direct adsorption of metal atoms on Si is prevented. However, such issues can be solved by preparing Si surfaces in ultrahigh vacuum, which allows precise control over atomic arrangements depending on the crystal orientations and the doping135,136. Secondly, when the deposition of metal atoms increases, particularly at relatively high temperatures in ultrahigh vacuum, the surface atoms tend to rearrange and sometimes aggregate. This kind of structural modification can potentially lead to modifications of the electronic and chemical properties of the Si surfaces. Hence, a careful trade-off between the deposition rate of metal atoms on the Si surfaces and the desired chemical reactivity must be rationalized to enhance the efficiency of SACs involving Si photoelectrodes. Another challenge, like in any other substrate in SACs reaction, is to control the hybridization of single atoms on Si that eventually dictates their reactivity137. When very small amounts of metals are adsorbed on clean and well-ordered Si surfaces, the dispersed metal atoms can strongly influence the surface reactivity. For example, Pd-based metal clusters with a well-defined atomic arrangement, leading to a stable configuration corresponding to Pd6 hexamer clusters on Si(111)−7 × 7. Such metal assembly on the Si surface has been predicted to selectively convert CO2 to alkanes and alcohols, providing direct pathways to promote C–C coupling reactions138. Although the reconstructed Si surfaces offer a template for the deposition of dispersed metal catalysts, their subsequent exposure to oxygen during the PEC reactions might disrupt the uniformity and density of active sites. Therefore, they can be effectively used for reactions that do not require an oxygen atmosphere, for example, in the non-oxidative coupling of alkanes.

The self-assembly of molecular networks on Si surfaces offers another alternative strategy to control the electronic properties and reactive surfaces of Si. Such a process usually involves the passivation of the Si dangling bonds to prevent a strong chemisorption of the molecules, resulting in a weak interaction between molecules and the Si surface. This approach allows the diffusion of adsorbed molecules to self-assemble into supramolecular structures139 with precise alignment for the formation of distinct pore geometries. Their size can be tunable depending on the number of atoms that can be adsorbed prior to the subsequent reactions.

Overall, the different approaches presented here can effectively be applied to use single metal atoms or small metal clusters anchored on Si photoelectrodes for PEC reactions in the near future. The examples provided with reference to recent PEC reactions and ongoing research in employing Si for SACs are a promising area to investigate.

Alternate and emerging Si configurations to enhance the PEC reaction efficiency

Among different forms of nanostructures, Si NWs are extensively employed for PEC reactions. However, it is essential to understand alternate Si configurations, beyond the NW configuration, to drive PEC reactions. In this direction, this section provides an overview of emerging configurations of Si, though some of them are yet to be tested for PEC applications. The two-dimensional (2D) Si-based materials, such as silicene, silicane, and Si nanosheets, offer a high specific surface area and improved charge transport compared to planar Si140. However, like Si NWs, these 2D materials are prone to surface oxidation, which can be passivated through various surface modification techniques. Currently, studies on these 2D materials are primarily focused on their applications in electronic and energy storage devices141. However, these materials show great potential in photocatalysis142. Further research into their structural, surface, and optoelectronic properties will enhance their efficiency and further enable utilization in PEC applications.

Amorphous Si with its disordered atomic structure offers a high optical absorption coefficient, enabling efficient light absorption143. Additionally, amorphous Si can be deposited at low temperatures using scalable techniques such as plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition, making it a cost-effective alternative for PEC electrode fabrication. Due to these prospects, p/i/n and n/i/p junctions based on amorphous Si were recently utilized to drive efficient PEC bias-free OWS reaction144. Additionally, silicides, particularly transition metal silicides, have gained significant interest for PEC applications. Metal silicides such as NiSi have been fabricated on Si-based photoelectrodes for PEC HER145 and OER146. The NiSi exhibits strong alkali resistance, ensuring high stability for photoelectrodes in alkaline electrolytes. The NiSi also inhibits charge recombination, thus further increasing the PEC efficiency of Si.

Outlook

Due to the advancement in tools and methods for making different nanostructures, the last decade has witnessed a renaissance in utilizing Si for solar-to-chemical energy conversion via CO2RR, N2RR to form NH3, biomass valorization, and HER. Though surface and optoelectronic modifications yielded a modest increment in the PEC performance, the observed quantum efficiency values are significantly low. For example, compared to the theoretically maximum STH efficiency exceeding 40%, the currently achieved STH is not even 1%. A critical outlook on understanding the origin of loss processes and how fundamental photophysical processes such as light absorption, charge carrier transport, and transfer at the electrolyte interface influence PEC activity is provided in this Review.

NW configuration is by far the extensively employed Si nanostructures for various types of PEC reactions, due to their light trapping ability (thus enhancing the light absorption efficiency) and higher surface area. Both these parameters are expected to enhance the PEC efficiency. Though the NW-based photoelectrode showed higher PEC performance than its wafer (film) form, it is still orders of magnitude lower than the theoretically achievable efficiency. This inadequate performance can be attributed to inefficient charge transfer, which is in kinetic competition with efficient charge carrier trapping at surface defects, eventually limiting the PEC efficiency. In addition, the extent to which the anisotropic charge transport (along vs across the wire) affects the PEC performance under bias needs to be unveiled. One of the approaches to address this would be by fabricating NWs of a width shorter than the diffusion length of photogenerated charge carriers to promote enhanced interfacial charge transfer, leading to higher PEC performance. However, due to the indirect band gap of Si, having thin layers will result in lower absorption efficiency. As an alternate strategy to enhance light absorption, a tandem configuration by sandwiching Si with a wider band gap photocatalyst may also be employed for PEC applications. For example, the tandem assembly of perovskite-BiVO4 with improved light absorption was found to increase PEC reaction efficiency, as the metal oxide absorbs light in the visible region and the perovskite harvests low-energy photons147. Moreover, such a tandem cell with a dual light absorber design improves spatial separation of charge carriers, leading to efficient charge extraction and subsequent utilization in various PEC reactions148. Recent emphasis on the ease of using Si in the design of metasurfaces with enhanced optical absorption properties could also be beneficial. However, the behavior of such metasurfaces for PEC applications needs to be explored further149,150.

It is also essential to pay attention to the alternate nanostructures, beyond the usually employed nanowire configuration. For example, silicide nanostructures with a well-defined interface with Si151 were developed in the 1980s, and there is a renewed interest in such nanostructures for PEC applications145,146. In addition, thin films of amorphous Si144 and nanoporous Si62 have gained attention and emerged as promising candidates for low-cost yet efficient PEC applications. Note that, unlike in photovoltaic devices, creating a smooth interface is not necessarily required.

As discussed in the section “Role of doping in PEC reactions”, depending on the PEC reaction type, n- or p-doped Si is widely employed to ensure sufficient thermodynamic driving energy. However, dark carriers formed due to doping promote recombination with photogenerated charge carriers. Note that the number of carriers that successfully transfer at the electrolyte interface eventually dictates the PEC efficiency. In this process, bulk electron-hole recombination and trapping of charge carriers are major bottlenecks limiting the PEC performance. To address these challenges, various kinds of metal cocatalysts and oxide layers are coated on the surface of Si. However, they can only create surface band bending and accept charge carriers if they are able to reach them to drive PEC reactions. Hence, there needs to be a better strategy so that charge carriers generated in bulk can efficiently be migrated to the electrolyte interface.

To conclude, the rational insights discussed in this Review may aid in unlocking the true potential of Si as a photoelectrode to enhance solar fuel production and to make a transition towards sustainability. Immense prospects in developing cost-effective nanostructures with tailored optoelectronic/surface properties for light-driven technologies, such as SACs and bias-free OWS, will be exciting for researchers from the wider community.

References

Yu, J. et al. Basic comprehension and recent trends in photoelectrocatalytic systems. Green Chem. 26, 1682–1708 (2024).

Fujishima, A. & Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 238, 37–38 (1972).

Kempler, P. A. & Nielander, A. C. Reliable reporting of Faradaic efficiencies for electrocatalysis research. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–4 (2023).

Zabara, M. A. et al. Photoelectrocatalytic hydrogen generation: current advances in materials and operando characterization. Glob. Chall. 8, 2400011 (2024).

Kumar, M., Meena, B., Subramanyam, P., Suryakala, D. & Subrahmanyam, C. Recent trends in photoelectrochemical water splitting: the role of cocatalysts. NPG Asia Mater. 14, 1–21 (2022).

Sivula, K. & Van De Krol, R. Semiconducting materials for photoelectrochemical energy conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 1–16 (2016).

Luo, Z., Wang, T. & Gong, J. Single-crystal silicon-based electrodes for unbiased solar water splitting: current status and prospects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 2158–2181 (2019).

Tavakoli, N. et al. Over 65% sunlight absorption in a 1 μm Si Slab with hyperuniform texture. ACS Photonics 9, 1206–1217 (2022).

White, J. L. et al. Light-driven heterogeneous reduction of carbon dioxide: photocatalysts and photoelectrodes. Chem. Rev. 115, 12888–12935 (2015).

Mane, S. J., Joseph, N. B., Kumari, R., Narayan, A. & Bhattacharyya, A. J. Electrochemical reduction of nitrogen to ammonia using zinc telluride. ACS Mater. Au 4, 582–591 (2024).

Jang, W. J., Park, P. J., Ma, J. & Kim, S. Y. Engineering perovskite solar cells for photovoltaic and photoelectrochemical systems: strategies for enhancing efficiency and stability. Chem. Commun. 61, 8137–8156 (2025).

Moura de Salles Pupo, M. & Kortlever, R. Electrolyte effects on the electrochemical reduction of CO2. ChemPhysChem 20, 2926–2935 (2019).

Lee, S. W., Bae, S., Kim, D. & Lee, H. S. Historical analysis of high-efficiency, large-area solar cells: toward upscaling of Perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002202 (2020).

Zhou, P. et al. Solar-to-hydrogen efficiency of more than 9% in photocatalytic water splitting. Nature 613, 66–70 (2023).

Tang, C., Chen, Y., Rao, J., Guo, H. & Zhou, Y. Solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiency for photovoltaic water electrolysis to produce green hydrogen. Small 21, 2502342 (2025).

Teitsworth, T. S. et al. Water splitting with silicon p–i–n superlattices suspended in solution. Nature 614, 270–274 (2023).

Deng, J. et al. Nanowire photoelectrochemistry. Chem. Rev. 119, 9221–9259 (2019).

Andrei, V., Roh, I. & Yang, P. Nanowire photochemical diodes for artificial photosynthesis. Sci. Adv. 9, eade9044 (2023).

Zhang, B., Jie, J., Zhang, X., Ou, X. & Zhang, X. Large-scale fabrication of silicon nanowires for solar energy applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 34527–34543 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Advancing silicon-based photoelectrodes toward practical artificial photosynthesis. Acc. Mater. Res. 5, 809–821 (2024).

Fabre, B. & Loget, G. Silicon photoelectrodes prepared by low-cost wet methods for solar photoelectrocatalysis. Acc. Mater. Res. 4, 133–142 (2023).

Oh, J., Deutsch, T. G., Yuan, H.-C. & Branz, H. M. Nanoporous black silicon photocathode for H2 production by photoelectrochemical water splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 1690 (2011).

Garnett, E. & Yang, P. Light trapping in silicon nanowire solar cells. Nano Lett. 10, 1082–1087 (2010).

Boettcher, S. W. et al. Energy-conversion properties of vapor–liquid–solid-grown silicon wire-array photocathodes. Science 327, 185–187 (2010).

Priolo, F., Gregorkiewicz, T., Galli, M. & Krauss, T. F. Silicon nanostructures for photonics and photovoltaics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 19–32 (2014).

Peng, K. Q., Wang, X., Li, L., Wu, X. L. & Lee, S. T. High-performance silicon nanohole solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6872–6873 (2010).

Bian, C. et al. Wafer-scale fabrication of silicon nanocones via controlling catalyst evolution in all-wet metal-assisted chemical etching. ACS Omega 7, 2234–2243 (2022).

Sun, W. et al. Heterogeneous reduction of carbon dioxide by hydride-terminated silicon nanocrystals. Nat. Commun. 7, 12553 (2016).

McVey, B. F. P. & Tilley, R. D. Solution synthesis, optical properties, and bioimaging applications of silicon nanocrystals. Acc. Chem. Res 47, 3045–3051 (2014).