Abstract

Achieving carbon neutrality in the lead industry requires both technological decarbonization and comprehensive reduction of surplus lead to mitigate environmental risks from stacking. A successful decarbonization pathway requires integrating material-oriented and technology-oriented factors synergistically. In this study, a comprehensive dynamic model was developed to encompass emissions of greenhouse gases throughout various processes and levels of lead redundancy across different scenarios. The results show that China’s cumulative lead consumption amounts to 190.24 million tonnes, with greenhouse gases emissions reach 250.96 million tonnes CO2-equivalent between 2021 and 2060. Strategies focused on material-oriented approaches to achieve an earlier carbon peak can yield short-term success, while a technology-oriented strategy demonstrates superior long-term optimization. In order to achieve synergistic outcomes in reducing pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, it is imperative to prioritize short-term improvements in recycling rates and long-term technological advancements. Additionally, exploring new applications for surplus lead should also be pursued.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Limiting global warming to 1.5 °C necessitates achieving net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050–20601. Given its energy-intensive nature and higher GHG emission intensity compared to steel, the decarbonization of the lead industry is imperative2,3. As a component within the industrial sector, achieving carbon neutrality in the lead industry necessitates consideration not only technical characteristics but also various factors encompassing production processes, product consumption, recycling practices, and more4,5,6. Based on statistical data, the cumulative global primary lead consumption has reached 224.6 million tonnes (Mt) between 1960 and 20227. The widespread adoption of lead-acid batteries (LABs) has sign remarkable contributed to the rapid growth in global lead consumption, which is projected to reach 12.6 Mt by 2022, with LABs consumption accounting for over 80%7,8. However, the growing prevalence of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) driven by the progress towards carbon neutrality presents a gradual challenge to LABs, potentially leading to decreased demand for lead9,10. Simultaneously, lead, as a metal with high recovery rate and social inventory, is increasingly contributing to the supply of secondary lead; however, it is expected that the availability of raw lead ore will remain abundant in the future due to its association with zinc mining7,11,12. In this particular context, the lead industry is confronted with a challenge posed by environmental segregation resulting from an excessive supply13. Therefore, decarbonization pathway of the lead industry should not solely focus on technical means to reduce GHG emissions but also comprehensively address how to mitigate environmental risks arising from oversupply.

The combination of material orientation and technology orientation is crucial for the decarbonization of the lead industry. Regarding the technology orientation, life cycle assessment (LCA) is primarily employed to calculate GHG emissions in the lead product manufacturing14,15,16, as well as recycling processes17,18. However, these studies overlook the comprehensive impact and temporal dynamics in the life cycle of the lead industry. Regarding the dynamic material flow in the lead industry, current research predominantly focuses on conducting bottom-up and top-down analyses of historical and future lead flows and stocks across various countries and regions13,19,20,21. The combination of material flow and GHG emissions of lead metal has received relatively less attention. Although several studies have combined material flow with GHG emissions3,22, the importance of decarbonization of the lead industry has been demonstrated. However, these studies have not taken into account heterogeneous country contexts, detailed bottom-up data, and differences between technology orientation and material orientation.

As the largest global producer and consumer of refined lead7,23, China has already initiated the Implementation Plan for Carbon Peaking in Non-ferrous Metal Industry to ensure that the carbon peaking is accomplished on schedule24. The investigation of the evolutionary trajectory of GHG emissions in China’s lead industry within the social and economic system is of utmost importance. The integration of material flow analysis (MFA) with GHG emissions offers a promising approach to address this issue. The comprehensive assessment framework of the GHG emission accounting model is depicted in Fig. 1, integrating material-oriented dynamic MFA with technology-oriented material-energy-emission relationships. Considering China’s unique circumstances, this study initially employs a combination of bottom-up and top-down methods to analyze and forecast lead flows and stocks in China’s socio-economic system from 1990 to 2060. Subsequently, based on the technical requirements of different processes, the direct (scope 1), energy indirect (scope 2), and other indirect (scope 3) GHG emission factors for each stage are quantitatively calculated through mass balance, emission factors, and LCAs. Furthermore, by combining dynamic MFA, a GHG emission accounting model for the lead industry is constructed. Finally, nine policy scenarios are proposed to forecast the future emission status of China’s lead industry, revealing the material and emission implications of China’s lead industry under various individual or combined technology- and material-oriented transition scenarios.

a System framework, b combination scenario settings. P1-P9 represent the nine key processes in the lead cycle. M1-M9 represent the nine typical product categories. S1-S2 represent the two prototypical product inventories. L1-L8 represent the lead losses in eight typical processes. ①-⑨ correspond to the nine crucial factors considered in this study, while the three colors signal lamp symbolize distinct future development scenarios. S1-S9 denotes GHG emission changes resulting from alterations in material-oriented transition (⑤-⑨), indicated by the horizontal arrow, and shifts in technology-oriented transition(①-④), represented by the vertical arrow.

Results

History and future of lead cycle in China

It can be observed that China’s cumulative lead consumption from 1990 to 2020 amounts to 62.75 Mt, with LAB usage accounting for 77.43% of this total. Under the BAU scenario, the cumulative lead consumption in China between 2021 and 2060 will reach 190.24 Mt (Fig. 2a). The supply source of lead, as illustrated in Fig. 2b, has observed a consistent increase in the proportion of secondary lead supply in China due to the continuous implementation of the extended producer responsibility system. By 2023, it is projected that secondary lead supply will surpass 50%, emerging as the primary source of lead resources in China. It is anticipated that by 2060, it will account for ~82.95% of China’s total supply. Simultaneously, as China’s lead industry faces declining demand, it is projected that China will have an excess of lead concentrate by 2039 under the BAU scenario. This trend is expected to progressively intensify, resulting in a surplus of 11.7 Mt of lead in China by 2060. The appropriate management and disposal of the remaining stock will become an important future concern due to the environmental toxicity associated with lead.

a Forecasted flow and stock of the lead industry in China from 2021 to 2060, b source of lead in China from 1990 to 2060, c consumption of lead in China from 1990 to 2060, d in-use stock of lead in China from 1990 to 2060, e scrap of lead in China from 1990 to 2060. The data from 1990 to 2020 are historical data, while the data from 2021 to 2060 are forecasted.

The demand for China’s lead industry is depicted in Fig. 2c. In terms of overall demand, it reached peak in 2025 at 6.19 Mt and gradually declined to 2.31 Mt by 2060 due to the gradual replacement of lead in power battery (PB) and other sectors. Regarding the proportion of demand, the stock of electric bicycles will reach saturation for traction batteries, leading to an accelerated replacement of LAB with LIB. Consequently, PB consumption will peak and then decrease to 0.49 Mt by accounting for 21.38% of LAB consumption. As for starting, lighting and ignition battery (SliB), the in-use stock will continue growing alongside vehicle growth. With the implementation of new energy vehicles and reducing lead content demands peaked at 1.73 Mt in 2033.

The change of lead-in-use stock in China’s social and economic system is indeed shown in Fig. 2d. From 1990 to 2020, China increased from 0.35 Mt to 13.66 Mt, with a compound annual growth rate of 12.99%. From the perspective of annual increment, lead in-use stock began to increase rapidly from 2004. In particular, the increase in the use of power batteries is particularly obvious; China’s lead stock will peak at 14.47 Mt in 2027 and then decline slowly. In terms of the structure of the use stock, LABs are still the largest lead-in-use stock in the socio-economic system.

As depicted in Fig. 2e, the ownership of lead scrap in China has exhibited a consistent growth trend, escalating from 0.06 Mt in 1990 to 4.59 Mt in 2020. The cumulative amount of scrap has reached an impressive total of 44.67 Mt. Subsequently, as lead consumption diminishes within China, the annual volume of scrap is projected to gradually decline and is anticipated to reach 2.25 Mt by 2060. From 2021 to 2060, under the BAU scenario, it is estimated that the cumulative volume of scrap will soar up to ~168.01 Mt; with battery scraps accounting for around 95.42%. Regarding lead loss, it predominantly occurs during the dissipation use stage (52.1%) and milling and mining activities (30.3%), which are not subjected to recycling efforts (S5.1).

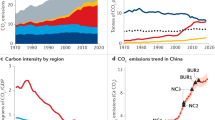

GHG emissions of lead industry

The GHG emissions of China’s lead industry are presented in Fig. 3a. These emissions have been increasing due to the rising demand for PBs and SliBs. From 1990 to 2013, the compound growth rate was recorded at 11.26%. However, subsequent efforts by China to eliminate outdated production capacity led to a decline in primary lead production. Technological progress also contributed to a decrease in GHG emissions from the lead industry between 2013 and 2017. Nevertheless, as domestic lead consumption continued to grow, GHG emissions started rebounding. By 2020, GHG emissions from this industry reached a level of 9.86 Mt CO2-equivalent (CO2e). Analysis of different emission processes reveals that smelting currently serves as the primary source of the lead industry GHG emissions in China, accounting for approximately 4.30 Mt CO2e (43.26% of total emissions) in 2020.

The GHG emissions intensity of mining and milling, smelting, refining, processing, and recycling has shown a consistent decrease from 0.34 t CO2e t−1, 2.08 tCO2e t−1, 0.61 t CO2e t−1, 0.13 t CO2e t−1, and 1.74 t CO2e t−1 in 1990 to 0.32 t CO2e t−1, 1.41 t CO2e t−1, 0.60 t CO2e t−1, 0.11 t CO2e t−1 and 1.03 t CO2e t−1 in 2020 (S5.2). In particular regard to the smelting process within China’s mining industry sector; sintering pots and other outdated technologies have been gradually phased out while concurrently promoting oxygen-enriched air smelting processes and advancing direct reduction technology to consistently reduce energy consumption during smelting operations thereby resulting in a corresponding decline in GHG emissions intensity. However, the electrolytic refining process in China has not witnessed any substantial advancements, thereby resulting in limited variability in GHG emissions intensity. Furthermore, traditional industries such as reverberatory furnaces have been continuously eliminated throughout the recycling process leading to a consistent reduction in unit GHG emissions overall.

With the consumption in China has gradually increased to its peak, it is projected that annual GHG emissions of lead industry will reach 10.05 Mt CO2e by 2022 and subsequently decline to 2.28 Mt CO2e by 2060. The cumulative emissions from 2021 to 2060 are estimated to amount to 250.96 Mt CO2e. In terms of emission reduction strategies, as demand from China’s lead industry continues to diminish, efforts will be made until 2060 to progressively reduce the most GHG-intensive smelting processes. This targeted approach is expected to sensible mitigate GHG emissions from China’s lead industry, resulting in a projected emission level of only 0.39 Mt CO2e by 2060. From the period between 2021 and 2060, the cumulative emission attributed specifically to smelting activities is anticipated at approximately 82.41 Mt CO2e.

With the increasing production of secondary lead in China, it is projected that by 2036, secondary lead will surpass smelting lead and emerge as the primary source within the lead industry. Furthermore, by 2060, GHG emissions from recycling process are expected to account for 56.37% of total emissions. From an emission scope perspective, scope 1 cumulative emissions amount to 136.19 Mt CO2e, representing 56.49% of China’s lead industry emissions and serving as a key target for emission reduction efforts within this sector (S5.2). Additionally, considering emission intensity, there has been a sensible decrease of 30.76% compared to levels observed in 2020 due to changes in China’s technological structure.

Figure 3b shows the comparison between the annual emissions and carbon emission requirements of China’s lead industry under the SSP1-1.9 scenario. The lead industry in China has the largest abatement demand in 2040, reaching 4.22 Mt CO2e. The emission reduction rate more than 50%. As shown in Fig. 3c, the carbon budget of China’s lead industry by 2060 is 140.63 Mt CO2e. However, under the BAU, the cumulative GHG emissions of China’s lead industry will reach 250.96 Mt CO2e from 2021 to 2060, and the task of emission reduction is arduous.

Comparison of GHG emissions across different scenarios

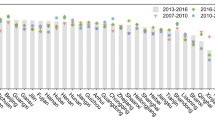

The findings depicted in Fig. 3 demonstrate that China’s cumulative GHG emissions have surpassed the SSP1-1.9 scenario by a staggering 78.45%. In 2060, China’s lead industry still emissions 2.28 Mt CO2e, highlighting the need for analysis of emission reduction effects under different policy scenarios. Figure 4 illustrates the variations in GHG emission reduction effects across different single scenarios.

Regarding energy materials technology, the upstream impact of GHG emission reduction on the lead industry is demonstrated by S-MI and S-EI, specifically in terms of scope 3 emissions. In comparison to the BAU, there is no discernible influence on the flow of elements within the lead industry. As the efficiency of upstream energy emission reduction gradually improves, so does its effect on emission reduction, resulting in a medium scenario with a reduction rate of 17.73% by 2060. The cumulative emission reductions by 2060 are explicitly different at 8.17 Mt CO2e, 14.57 Mt CO2e, and 20.91 Mt CO2e for each respective scenario. In terms of electric power cleaning, when compared to non-ferrous metals like copper and aluminum, the lead industry exhibits relatively lower power consumption and less sensitivity to emissions intensity of power consumed. However, as emission intensity reductions in the power industry gradually decrease over time, their impact on emission reduction weakens accordingly. The cumulative emission reductions under three scenarios amount to 7.95 Mt CO2e, 10.63 Mt CO2e, and 13.47 Mt CO2e respectively.

The utilization of low-carbon energy in China’s lead industry will experience a corresponding acceleration as the process of achieving carbon neutrality continues to advance, driving technological progress. As demonstrated in S-SM, when zero or low-carbon fuels replace conventional fuels, there is a noticeable reduction in emissions, making it a sensible contributor to scope 1 emission reductions. Additionally, substitution efficiency can greatly impact industrial carbon emissions and exhibits high sensitivity. In the medium scenario, annual emissions are projected to be 1.57 CO2e Mt by 2060 with an emission reduction rate reaching 31.43%. The cumulative emission reduction amounts to 43.44 Mt CO2e. Under S-CL, through the development of shorter processes that cater precisely to enterprise demands while reducing lead melting and casting operations and effectively minimizing power consumption; cumulative emission reductions for this scenario amount to 5.83 Mt CO2e, 8.53 Mt CO2e, and 11.23 Mt CO2e respectively.

The consumption of lead will increase in response to rising demand, leading to an elevation in GHG emissions. Conversely, a decrease in demand will result in a reduction of surplus lead. Regarding the S-OW, under the high scenario, China’s lead industry is projected to exhibit an upward trend with emissions reaching 2.51 Mt CO2e by 2060, representing a cumulative increase of 16.47 Mt CO2e. In the low scenario, emissions from the lead industry are expected to decrease to 2.09 Mt CO2e by 2060 and cumulative emissions would reduce to 20.78 Mt CO2e; however, this would coincide with an increase in cumulative residual lead resources. The application of lead-carbon batteries (LCBs) would result in increased lead consumption and subsequently alter the flow of lead while increasing emissions accordingly. Under all three scenarios considered, China’s lead industry is estimated to emit 2.60 Mt CO2e, 2.83 Mt CO2e and 3.12 Mt CO2e, respectively by 2060; corresponding to cumulative increases of 5.85 Mt CO2e, 8.12 Mt CO2e and 13.07 Mt CO2e, respectively. Finally, in terms of import and export dynamics, the declining volume of LAB exports has led to a continuous decrease in the demand for China’s lead industry. However, due to its relatively small proportion, the emission reduction effect remains relatively weak.

The proportion of secondary lead within the supply category in China is increasing due to the rising recovery rate of lead and advancements in the recycling process. However, enhancing the recovery rate can effectively stimulate domestic production and substitution of secondary lead within China, thereby augmenting emission reduction in China’s lead industry to 2.11 Mt CO2e by 2060, with a cumulative reduction of 12.72 Mt CO2e. In the S-ZD scenario, collaborative management between lead-zinc industries will result in a decrease in lead mining amount in China; although its carbon reduction effect is relatively weak, it exhibits sensible residual reduction effects with reductions amounts of 3.31 Mt CO2e, 2.80 Mt CO2e, and 2.28 Mt CO2e under three scenarios (S5.2).

Decarbonization potential of integrated scenarios

The subsequent section illustrates the GHG emissions of nine integrated scenarios, highlighting the challenges in meeting the decarbonization requirements of the lead industry and emphasizing the imperative to comprehensively consider the cumulative impacts of various policy scenarios. The GHG emission trajectories under these integrated scenarios and the corresponding lead residuals are depicted in Fig. 5a, b. The findings reveal that technology-oriented and material-oriented approaches have explicitly divergent impacts on the potential for emission reduction within the lead industry. As depicted in Figs. 5a, S1, S2, and S3, annual emissions decrease gradually with declining demand; specifically, by 2060 they amount to 2.42 Mt CO2e, 1.85 Mt CO2e, and 1.30 Mt CO2e respectively. Under conditions where consumption remains unchanged, there is a gradual reduction in emission intensity resulting in respective emissions of 2.42 Mt CO2e, 1.75 Mt CO2e, and 1.13 Mt CO2e by 2060. In terms of long-term trends, the efficiency gains from technological advancements surpass reductions achieved through decreased demand. However, in relation to 2030, the short-term impact of supply and demand is evident as indicated by respective emissions for S1, S2, and S3 at 8.04 Mt CO2e, 7.09 Mt CO2e, and 6.21 Mt CO2e. Furthermore, S4 exhibits an emission level similar to that of S7 at 7.57 CO2e Mt and 7.12 Mt CO2e respectively.

The cumulative total emissions from 2021 to 2060, as depicted in Fig. 5c, demonstrate that both material-oriented and technology-oriented transitions exhibit similar potential for emission reduction, albeit with distinct patterns. Material-oriented transformation can reduce cumulative emissions from 2021 to 2060 by about 23% (for example, S1, S4, and S7 in cumulative emissions from 246.87 Mt CO2e, 224.68 Mt CO2e and 199.87 Mt CO2e to 185.61 Mt CO2e, 167.19 Mt CO2e and 149.41 Mt CO2e of S3, S6 and S9, respectively). Simultaneously, as the demand diminishes, the proportion of secondary lead increases while the primary source of emissions shifts from smelting to recycling processes. Similarly, a technology-oriented transition can reduce the cumulative total emissions of the corresponding demand scenario by 20% (Decreased from 246.87 Mt CO2e, 214.09 Mt CO2e, 185.61 Mt CO2e in S1, S2 and S3 to 199.87 Mt CO2e, 171.38 Mt CO2e, 149.41 Mt CO2e in S7, S8 and S9), through technological innovation, efficiency gains, and other improvements. As for the carbon budget, as shown in Figs. 5d, S6, S8 and S9 all meet SSP1-2.6, while other scenarios cannot meet SSP1-2.6 due to high consumption or emission intensity.

Regarding the surplus lead resources, as the demand diminishes, there is a gradual increase in surplus. In the low-demand scenario, surplus emerges by 2034 (Fig. 5b). Cumulative surplus results depicted in Fig. 5e indicate that under the low-demand scenario, the surplus amounts to 19.18 Mt. It reaches 10.25 Mt in the medium scenario and 2.71 Mt in the high demand scenario. Considering Fig. 5d, it becomes evident that S8 exhibits the smallest volume of remaining lead resources under the SSP1-2.6 scenario.

Simultaneously, in response to the pressing challenges of climate change, practical approaches combining material- and technology-oriented transition pathways will be employed for mitigation strategies. To explore various partial combinations as well as full and sequential integration of policy pairs on emission paths, we conducted a decarbonization analysis using BAU and S9 as benchmarks. When implementing all these strategies in a sequential combination, annual emissions are projected to gradually decrease. By 2060, emissions are expected to reduce from 2.28 Mt CO2e to 0.48 Mt CO2e, representing a reduction of 79.10% (Fig. 6a).

The findings in Fig. 6b further validate the evolving significance of technology and material-oriented strategies over time, consequently altering mitigation priorities. For instance, the integrated technology-oriented strategy is projected to contribute 57.89% towards emission reduction by 2025, which escalates to 87.31% by 2060. In contrast, relative to the BAU scenario, the demand-oriented integrated strategy’s contribution towards emission reduction will only amount to 12.69% of annual emissions by 2060. Regarding comprehensive contributions (Fig. 6c), industrial technologies (S-CL + S-SM) constitute a sensible portion at 41.61% of the total. This is followed by materials and energy technologies (S-EI + S-MI) at 29.32%. Demand category (S-EL + S-OW + S-AL) represent smaller shares, ~15.11%, Among them, the contribution rate of S-AL is −2.78%, attributed to its application in new fields which leads to an increase in lead consumption. Supply category (S-RR + S-ZD) have the smallest share, ~13.96%.

Discussion

The results clearly demonstrate the necessity and practicality of integrating material-oriented and technology-oriented approaches into a systems-based framework. This comprehensive overview effectively optimizes the trade-offs between climate change mitigation and other sustainability challenges, providing insights into the timing and effectiveness of current strategies aimed at reducing GHG emissions in the lead industry. It is important to note that simultaneous implementation of technology- oriented strategies and demand-oriented approaches may potentially counterbalance each other.

In the long term, technological advancements alone can contribute explicitly to reducing GHG emissions within the lead industry, thereby leading to a substantial overall decrease in emissions. Policies that prioritize technology will witness a gradual increase in emission reduction through strategies such as material intensity optimization, material substitution, and closed-loop recycling; by 2060, their comprehensive contribution to emission reduction is anticipated to surpass 70%. However, short-term increases in emissions are likely due to reliance on current coal-based power sources and low rates of closed-loop recycling. The development and implementation of renewable energy technologies must be meticulously planned and executed for maximum climate benefits. Furthermore, accelerating the rate of closed-loop recycling within the lead industry through appropriate guidelines and best practices prior to decarbonization will further mitigate energy consumption and GHG emissions.

In contrast to technology-oriented strategies, material-oriented strategies play a crucial role in achieving short-term emissions reduction. As depicted in Fig. 6, the early-stage GHG emission reductions primarily stem from demand reduction and recycling improvements, accounting for 43% by 2025 and 13% by 2060. Consequently, it is imperative to promptly formulate policies that capitalize on this opportunity and further develop material-oriented measures. Enhancing the construction of a green recycling chain within the lead industry and implementing an extended producer responsibility system are essential steps towards bolstering lead resource recycling capacity while facilitating material availability for expediting short process realization25.

However, it is crucial to consider the sensible redundancy of lead mines and the growth of end-of-life waste in future developments within the lead industry, in order to prevent sustainability challenges from transitioning from climate-related issues to waste management and environmental toxicity concerns. This presents a capacity planning challenge for the lead industry. As depicted in Fig. 5d, there is a substantial accumulation of lead ore due to declining demand for lead industrial products; hence, ensuring safe and responsible utilization of this resource becomes imperative26. These circumstances offer opportunities for energy conservation and emission reduction that extend beyond mere reduction in demand for lead consumption. Therefore, gaining a comprehensive understanding of material cycles and applications associated with transformative development within the lead industry is essential to achieve a mutually beneficial outcome encompassing relevant resources, waste management practices, and climate policies.

Simultaneously, for the lead industry, measures such as resource and energy efficiency improvement in promoting carbon reduction also facilitate coordinated pollutant emission reduction. As illustrated in S5.1, China’s lead loss has decreased to 0.94 Mt by 2060, a decline of 69.31% compared with 2020 due to the development of China’s lead industry. Furthermore, under S8, China’s lead loss is projected to be 0.85 Mt in 2060 which is a decrease of 10.64% from BAU scenario and effectively mitigates environmental risks associated with lead dissipation. The results depicted in S5.3 demonstrate a consistent pattern of other environmental impacts, wherein an increase in recycling rate is associated with a sensible reduction of 6.99% in GHG emissions. Moreover, this positive trend corresponds to notable decreases in eutrophication potential, marine aquatic ecotoxicity potential, freshwater aquatic ecotoxicity potential, and human toxicity potential by up to 13.18%, 10.55%, 9.72%, and 5.03% respectively. Thus, on the lead industry decarbonization pathways, it is imperative that we simultaneously address pollutant emissions throughout the entire process to achieve synergistic outcomes.

According to the study, lead demand in China is projected to remain stagnant in 2020, mirroring the trends observed in North America and Europe. However, there is still expected growth in India, South America, and other regions. Consequently, import and export policies regarding lead ore can be flexibly adjusted in the short term to achieve a balance of supply and demand between China and other countries. Additionally, it is crucial to focus on the development of new applications on a global scale. As lead batteries continue advancing and battery demand reaches its peak, addressing how to incorporate lead becomes a worldwide concern. Given their high reliability compared to LIBs along with explicitly lower costs, LCBs are gaining increasing attention for large-scale energy storage purposes27,28. Therefore, emphasis should be placed on promoting and applying LCBs within the rapidly growing field of energy storage.

The practical realization of this material-oriented mitigation potential is expected to be a complex and challenging endeavor, necessitating collaborative efforts from all levels of government, industry, and consumers. It should be noted that the perspective provided by this study on decarbonizing the lead industry is not exhaustive. In addition to the various categories of material-oriented parameters considered in our analysis, there may exist additional strategies that warrant further comprehensive and quantitative research in the future. For instance, it is necessary to calculate the emission reduction costs of different decarbonization pathway, so as to provide support for the economic feasibility of decarbonization paths. Moreover, it would be valuable to explore whether resources such as nickel, cobalt, lithium can adequately support the growing demand for new energy batteries29,30 and assess their impact on replacing lead batteries.

Materials and methods

This paper employs a combination of bottom-up and top-down approaches to analyze the dynamic MFA of lead in China. The system definition of the Chinese anthropogenic lead cycle is illustrated in S2.1. The flow of lead within the socio-economic system can be categorized into five main processes, each consisting of several sub-processes. All processes strictly adhere to the principle of mass balance, and all inventories and flows are quantified based on lead metal equivalents. The spatial system boundary is the geographical boundary of mainland China. The study presents nine scenarios to assess the impact of technology and materials on China’s lead industry. Finally, it reveals the potential material and GHG emission consequences under different policy scenarios or integrated technology and material scenarios.

Historical lead cycle analysis

In this study, the dynamic MFA method31,32,33 was employed to quantify the material flow of lead in China from 1990 to 2020. The volume of in-use stocks and waste streams is modeled by historical apparent consumption of lead by end-use sector and its corresponding lifetime. Subsequently, other upstream and downstream flows are calculated by transfer coefficients, statistics, or mass balance principles34,35,36. The primary calculation formula is as follows:

∆Stock(t) represents the increase in inventory in t year;Fcon(t) represents the consumption in t year; P(t) represents the total scrap volume in t year; i and E represents imports and exports from other countries; W(t) represents the cumulative scrap rate in t year (using two-parameter Weibull distribution); u and g are parameters; f(t) represents the scrap rate in t year.

This study calculates the annual consumption of LABs from top to down, and then uses stock based to calculate the annual lead consumption for SliB, PB, storage battery (SB), and uninterruptible power supply battery (UPSB), and the difference between the annual consumption of LAB and the annual consumption of four kinds of LABs is the consumption of Other LABs (OBs). The stock of lead content is determined based on the following formula:

m represents the lead content per unit LAB capacity (kg kWh−1); n represents the LAB capacity per user (ahV). a represents market share (%); Q represents the LAB user’s stock. The specific parameters and calculation methods can be found in S2.2.

Prospective lead cycle analysis

The MFA of the future lead industry mainly adopts the combination of bottom-up and top-down methods, and the specific calculation methods mainly refer to the S2.3. It is primarily categorized into four segments, namely lead demand in LABs, lead demand in non-batteries, primary lead supply, and secondary lead supply.

Stock-based bottom-up approach is employed to quantify future stocks of lead in four typical LABs, the specific calculation formula is given by formulas (1)–(4). The level of detail regarding future stock growth assumptions varies across industries. For SliBs, Gompertz models are utilized to forecast the number of vehicles, considering their dependence on population and economy37. For PBs, it is mainly applied to electric bicycles as a special phenomenon in China31,38; However, they are being replaced by LiBs. For UPSBs, combined with industry research, this study predicts that the number of communication base station is 28.3 million39. For SBs, The implementation of China’s renewable energy strategy has set ambitious targets for the total installed capacity of wind and solar energy. By 2030, the target is to exceed 1.2 billion kilowatts, while by 2060, it aims to reach a staggering 5 billion kilowatts40,41,42. The pace of carbon neutrality in China is accelerating, and it is expected to be achieved at least five years ahead of schedule. For OBs, it is assumed that the consumption of OBs keeps pace with the growth of the LAB segments.

For lead demand of non-battery industries, this study expert that future demand in these sectors could be forecast from recent trends. The compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for sheets, alloys and other industries was 6.28%, 7.66%, and −6.21%, respectively from 2015 to 2020. The assumption is made that the non-battery consumption of lead will continue to follow the current trend from 2021 to 2025, and subsequently stabilize.

The relationship between primary mineral lead and primary mineral zinc in China is illustrated in S2.3. However, zinc is primarily utilized in the galvanizing sector. with the majority of consumption stemming from primary sources. the future of lead and zinc mining in China is primarily driven by the demand for zinc13. Therefore, this study determines that the supply of lead from primary minerals is contingent upon the supply of zinc. On the demand side, annual zinc demand is positively to the economy. The Brown linear trend forecast model was employed to estimate per capita GDP, while population data were based on the United Nations Population projections. The detailed calculation procedure and outcomes are presented in S2.3. According to relevant studies, China’s zinc supply dependence from 2021 to 2060 is 33%. Recycled zinc supply grows from 17% in 2020 to 20% in 2050 and 21% in 206043.

The supply of secondary lead is mainly determined by scrap amount and collection rate. The quantity of scrap is primarily determined through the utilization of formulas 1–4, while the future recovery rate is predominantly established based on the extended producer responsibility system, aiming to achieve a rate of 70% by 2030 and further increase it to 90% by 2060.

GHG emissions accounting

The quantification of GHG emissions related to the lead cycle is predominantly dependent on the coefficients assigned to each process output. This includes accounting for scope 1, scope 2, and scope 344. Due to the absence of non-carbon dioxide GHG emissions in the process, direct GHG emissions (Scope 1) solely encompass carbon dioxide resulting from energy combustion and coke reduction. The Gabi database (2021 version) is employed for accounting indirect GHG emissions data, which includes upstream production and processing chains as well as auxiliary materials. This comprehensive dataset primarily encompasses carbon dioxide and non-carbon dioxide GHGs such as methane. This study mainly focuses on five processes: mining and milling, smelting, refining, process, and recycling. However, for the manufacturing and use stages, which are challenging to allocate to a single material, they should be reported by a specialized industry department45. Additionally, transportation of raw materials is excluded from this study due to its small proportion; reference can be made to other industry research46. The specific model used for GHG emission accounting is presented in Table 1.

In the mining and milling process, lead and zinc are often symbiotic in primary deposits, mainly lead-zinc sulfide ore, and the GHG emission in the mining and milling process is distributed by the value of lead and zinc content47,48. During crude lead smelting, there have been continuous improvements in technology and equipment to transition from the highly polluting and energy-intensive sintering machine-blast furnace reduction process to more environmentally friendly options such as oxygen-rich molten pool smelting-liquid high lead slag direct reduction process or oxygen-rich flash smelting49. Different typical technologies are used to calculate emissions according to the proportion of processes. In the refining process, China primarily employs the electrolysis technique. In the recycling process, it mainly includes crushing, grid smelting, lead paste smelting, and lead refining, mainly including the traditional industry represented by the reverberatory furnace and the advanced process represented by the molten pool smelting50,51. The details can be found in Supplementary Note 3.

Scenarios

Table 2 illustrates the utilization of industrial material orientation and technology orientation to establish nine scenarios, based on the business-as-usual (BAU) scenario presented. At the technology orientation, two aspects are considered: energy/material technology and industrial technology. In terms of energy technology, the focus is mainly on energy/material emission intensity and electricity emission intensity scenarios. The focus in industrial technology lies primarily on closed-loop recycling and material substitution. Regarding material orientation, scenarios include LAB export, ownership changing, LCB application scenario, recycling rate scenario, and zinc concentrate demand change scenario. Additionally, in order to explore future dynamics in China’s lead industry along with its impact on materials and GHG, we define low-, medium-, and high-levels based on material-oriented as well as technology-oriented transition paths. These nine parameters form a combination of scenarios that present a wide range of possible worst- and best-case outcomes. The determination of low-, medium-, and high-level parameters is primarily based on historical patterns in China as well as future projections considering different socioeconomic development narratives.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Supplementary notes, figures, and data that support the findings of this study are provided in the supplementary information file. All data are available in the figshare Data repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26068183

References

Bergero, C. et al. Pathways to net-zero emissions from aviation. Nat. Sustain. 6, 404–414 (2023).

Abdul, F., Iizuka, A., Ho, H., Adachi, K. & Shibata, E. Potential of major by-products from non-ferrous metal industries for CO2 emission reduction by mineral carbonation: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 78041–78074 (2023).

Van der Voet, E., Van Oers, L., Verboon, M. & Kuipers, K. Environmental Implications of future demand scenarios for metals: methodology and application to the case of seven major metals. J. Ind. Ecol. 23, 141–155 (2019).

Guerra, O. J., Almajed, H. M., Smith, W. A., Somoza-Tornos, A. & Hodge, B. Barriers and opportunities for the deployment of CO2 electrolysis in net-zero emissions energy systems. Joule 7, 1111–1133 (2023).

Dai, M. et al. Country-specific net-zero strategies of the pulp and paper industry. Nature 626, 327–334 (2024).

Fritzeen, W. E. et al. Integrated assessment of the leading paths to mitigate CO2 emissions from the organic chemical and plastics industry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 20571–20582 (2023).

ILZSG. The World Lead Factbook 2023. https://www.ilzsg.org/wp-content/uploads/SitePDFs/1_ILZSG%20World%20Lead%20Factbook%202023.pdf (Accessed 21 December 2023).

Mamede Bezerra, M. D. L., Mendonça Silva, M. & Machado Santos, S. Forecasting of secondary lead recovery from motorcycle batteries in Brazil: a contribution to waste management. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 106260–106275 (2023).

Zhang, J. Study on Demand Forecast and Supply Structure of Lead in China from 2020 to 2035 (China University of Geosciences, 2019).

Elshkaki, A., Graedel, T. E., Ciacci, L. & Reck, B. K. Resource demand scenarios for the major metals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 2491–2497 (2018).

Rostek, L., Pirard, E. & Loibl, A. The future availability of zinc: potential contributions from recycling and necessary ones from mining. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 19, 200166 (2023).

Roberts, H., Evolution of global secondary lead production. In Proc. 9th International Symposium on Lead and Zinc Processing, 2020 (eds. Siegmund, A. et al) 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37070-1_1 (TMS, Springer, 2020).

Liu, W., Chen, L. & Tian, J. Uncovering the evolution of lead in-use stocks in lead-acid batteries and the impact on future lead metabolism in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 5412–5419 (2016).

Hong, J. et al. Life cycle environmental and economic assessment of lead refining in China. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 22, 909–918 (2017).

Davidson, A. J., Binks, S. P. & Gediga, J. Lead industry life cycle studies: environmental impact and life cycle assessment of lead battery and architectural sheet production. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 21, 1624–1636 (2016).

Gao, W. et al. Life cycle assessment of a typical lead smelting process in China. J. Clean. Prod. 415, 137796 (2023).

Tian, X. et al. Environmental impact and economic assessment of secondary lead production: comparison of main spent lead-acid battery recycling processes in China. J. Clean. Prod. 144, 142–148 (2017).

Wang, Z., Yang, J., Qu, R. & Xiao, G. Environmental impact assessment of the dismantled battery: case study of a power lead-acid battery factory in China. Processes 11, 2119 (2023).

Ogundele, D., Ogundiran, M. B., Babayemi, J. O. & Jha, M. K. Material and substance flow analysis of used lead acid batteries in Nigeria: implications for recovery and environmental quality. J. Health Pollut. 10, 200913 (2020).

Fuse, M. & Tsunemi, K. Assessment of the effects of the Japanese shift to lead-free solders and its impact on material substitution and environmental emissions by a dynamic material flow analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 438, 49–58 (2012).

Jeong, K. P. & Kim, J. G. Lead acid battery recycling and material flow analysis of lead in Korea. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 20, 1348–1354 (2018).

Yokoi, R., Watari, T. & Motoshita, M. Future greenhouse gas emissions from metal production: gaps and opportunities towards climate goals. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 146–157 (2022).

Sun, Z. et al. Spent lead-acid battery recycling in China-A review and sustainable analyses on mass flow of lead. Waste Manage 64, 190–201 (2017).

Gu, Y. et al. Regulation mechanism for designing decarbonization pathways in the copper industry toward carbon neutrality. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 1518–1530 (2023).

Du, B., Hou, H., Xu, H. & Zhang, M. How to solve the problem of irregular recycling of spent lead-acid batteries in China?—An analysis based on evolutionary game theory. J. Clean Prod. 421, 138514 (2023).

Gottesfeld, P. Lead industry influence in the 21st century: an old playbook for a “modern metal. Am. J. Public Health. 112, S723–S729 (2022).

Yin, J. et al. Lead-carbon batteries toward future energy storage: from mechanism and materials to applications. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 5, 1–32 (2022).

Lopes, P. P. & Stamenkovic, V. R. Past, present, and future of lead–acid batteries. Science 369, 923–924 (2020).

Della Bella, S., Sen, B., Cimpan, C., Rocco, M. V. & Liu, G. Exploring the impact of recycling on demand-supply balance of critical materials in green transition: a dynamic multi-regional waste input-output analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 10221–10230 (2023).

Lal, A. & You, F. Will reshoring manufacturing of advanced electric vehicle battery support renewable energy transition and climate targets? Sci. Adv. 9, 6740 (2023).

Yan, L., Wang, A., Chen, Q. & Li, J. Dynamic material flow analysis of zinc resources in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 75, 23–31 (2013).

Rasmussen, K. D., Wenzel, H., Bangs, C., Petavratzi, E. & Liu, G. Platinum demand and potential bottlenecks in the global green transition: a dynamic material flow analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 11541–11551 (2019).

Zeng, A. et al. Battery technology and recycling alone will not save the electric mobility transition from future cobalt shortages. Nat. Commun. 13, 1341 (2022).

Liu, W., Cui, Z., Tian, J. & Chen, L. Dynamic analysis of lead stocks and flows in China from 1990 to 2015. J. Clean Prod. 205, 86–94 (2018).

Yang, J., Li, X., Xiong, Z., Wang, M. & Liu, Q. Environmental pollution effect analysis of lead compounds in China based on life cycle. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 2184 (2020).

China Nonferrous Metals Industry Association. China Nonferrous Metals Industry Yearbook, Beijing (China Metallurgical Press, 2021).

Huo, H. & Wang, M. Modeling future vehicle sales and stock in China. Energy Policy 43, 17–29 (2012).

Wu, T., Zhang, M. & Ou, X. Analysis of future vehicle energy demand in china based on a Gompertz function method and computable general equilibrium model. Energies 7, 7454–7482 (2014).

Liu, W. Study of cleaner production of lead-acid battery industry and lead flows and stocks in China. Tsinghua University, Beijing, 2016. J. Clean. Prod. 205, 86–94.

NDRC. Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Development of Energy Storage Technology and Industry. https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-10/12/content_5231304.htm) (Accessed 26 December 2023).

GEIDCO. China 2030 energy and power development planning research and 2060 outlook. https://www.shanxiranqi.com/show-18-16458-1.html) (Accessed 27 December 2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Accelerating the energy transition towards photovoltaic and wind in China. Nature 619, 761–767 (2023).

Yanjing, Z. Dynamic material flow analysis of indium in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 167, 105394 (2021).

Wang, P. et al. Efficiency stagnation in global steel production urges joint supply- and demand-side mitigation efforts. Nat. Commun. 12, 2066 (2021).

Liu, G., Bangs, C. E. & Müller, D. B. Unearthing potentials for decarbonizing the U.S. aluminum cycle. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 9515–9522 (2011).

Song, X. et al Life Cycle carbon emission accounting and emission reduction potential assessment of steel industry. J. Environ. Sci. 148, 650–664 (2023).

Farjana, S. H., Huda, N. & Mahmud, M. A. P. Life cycle analysis of copper-gold-lead-silver-zinc beneficiation process. Sci. Total Environ. 659, 41–52 (2019).

Wang, C., Deng, J., Carranza, E. J. M. & Lai, X. Nature, diversity and temporal–spatial distributions of sediment-hosted Pb―Zn deposits in China. Ore Geol. Rev. 56, 327–351 (2014).

Bai, L., Xie, M., Zhang, Y. & Qiao, Q. Pollution prevention and control measures for the bottom blowing furnace of a lead-smelting process, based on a mathematical model and simulation. J. Clean. Prod. 159, 432–445 (2017).

Jie, X. et al. Progress in waste lead paste recycling technology from spent lead–acid battery in China. J. Sust. Metall. 8, 978–993 (2022).

Wu, X. Research on lead material flow accounting and pollution load control strategy in the process of secondary lead smelting. World Nonferrous Met. 36, 5–6 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (52070007), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Funded Project (2022M720324), Changzhou Leading Innovative Talent Introduction and Cultivation Project (No. CQ20220070).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.G. was involved in the conception of the study, development of the optimization framework, model simulation, analysis of the results, writing of the first paper draft, and revising of the paper. G.Y. was involved in the development of the optimization framework, analysis of the results, and revising of the paper draft. W.Y. was involved in the conception of the study, development of the optimization framework, analysis of the results, and revising of the paper draft. L.Y. was involved in the development of the optimization framework, analysis of the results, and revising of the paper draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Xing Yao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: I-Yun Hsieh, Clare Davis, Alice Drinkwater, Heike Langenberg. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, G., Gu, Y., Wu, Y. et al. Technology and material-oriented strategies can reduce lead industry carbon emissions in China. Commun Earth Environ 5, 664 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01743-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01743-7