Abstract

While the changes in ocean heat uptake in a warming climate have been well explored, the changes in response to climate mitigation efforts remain unclear. Using coupled climate model simulations, here we find that in response to a hypothesized reduction of greenhouse gases in the late 21st century, ocean heat uptake would significantly decline in all ocean basins except the North Atlantic, where a persistently weakened Atlantic meridional overturning circulation results in sustained heat uptake. These prolonged circulation anomalies further lead to interbasin heat exchanges, characterized by a sustained heat export from the Atlantic to the Southern Ocean and a portion of heat transfer from the Southern Ocean to the Indo-Pacific. Due to ocean heat uptake decline and interbasin heat export, the Southern Ocean experiences the strongest decline in ocean heat storage therefore emerging as the primary heat exchanger, while heat changes in the Indo-Pacific basin are relatively limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the pre-industrial age, the Earth’s climate system has undergone rapid warming primarily due to human activities. The prevailing global warming trend is predominantly driven by anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs). Elevated concentrations of GHGs alter the heat fluxes at the ocean surface, leading to an enhancement of global ocean heat uptake (OHU)1,2,3. Consequently, excess heat is stored in the ocean interior, resulting in an increase in global ocean heat content (OHC)2,3,4 (see “Methods”), as indicated by both climate models5 and empirical data6. The warming of the ocean contributes to the intensification of hurricanes7 and sea level rise8,9, posing significant threats to the coastal communities. Additionally, future projections from climate models indicate that, under high emission scenarios10,11 (Supplementary Fig. 1), both OHU and OHC are expected to continue rising, increasing the likelihood of more frequent and severe extreme events.

Various strategies have been proposed to mitigate the warming trend, with the reduction of atmospheric GHGs concentrations being the most popular way. In hypothetical future scenarios where GHGs concentrations are substantially reduced, models simulate a noticeable decrease in net downward energy flux at the top of the atmosphere (TOA), resulting in a cooling effect on Earth12. It is crucial to note that certain variables exhibit significant hysteresis in their response to GHGs removal, such as changes in hydrological cycles13,14,15,16, Antarctic ice sheet retreat17, and ocean acidification18,19. These hysteresis effects are largely attributed to ocean dynamics. For instance, in the North Atlantic, despite a reduction in GHGs, the weakened state of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) due to previous CO2 increase persists in many models on a multi-decadal timescale20,21,22,23,24,25. The AMOC is a critical component of the global conveyor belt, with effects extending beyond the Atlantic basin26,27. Despite these interconnected impacts, the long-term consequences of AMOC weakening on the global energy imbalance in a mitigation scenario driven by decreasing GHGs remain unclear. Understanding these effects is essential for creating accurate climate projections and making well-informed policy decisions for the coming decades. To address this issue, we utilize ensembles of climate simulations conducted with the Seamless System for Prediction and Earth System Research28 (SPEAR) model, employing both the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways SSP5-8.5 (SSP585) and SSP5-3.4-overshooting (SSP534OS) simulations, as well as runs in seven Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 models (CMIP6, see “Methods”). Notably, the SSP534OS scenario shares the same GHGs trajectory as SSP585 until the mid-21st century, after which it anticipates a rapid decrease in GHGs concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Results

Global energy imbalance in the late 21st century

We first examine the global energy evolution in the late 21st century using SSP585 and SSP534OS simulations from the SPEAR and seven CMIP6 models (see “Methods”, Supplementary Table. 1). The multi-model mean (MMM) exhibits an increase in net energy flux (positive: downward thereafter) at the TOA throughout the 21st century in SSP585 (Fig. 1a). This increased net TOA energy flux indicates that more heat is being stored in the earth system, contributing to global warming under high GHGs emission scenarios, as reflected in the global mean surface temperature rising to about 292 K by the end of 21st century (Fig. 1b). In contrast, the MMM for SSP534OS shows a decrease in net TOA energy flux and a cooling trend of surface temperature starting from the mid-21st century in response to reduced GHG concentrations. It is important to note that the net TOA energy flux remains positive throughout 2015-2100 in SSP534OS, indicating that the earth system continues to store energy. Specifically, the energy enters the earth system in low latitudes and escapes in the high latitudes at the TOA (Supplementary Fig. 3). The ocean absorbs most of this energy as ocean heat uptake, primarily in the Indo-Pacific and Atlantic regions, with a smaller portion being released back into the atmosphere in the Southern Ocean and Arctic Ocean. Therefore, even though the Earth system continues to absorb energy until the end of SSP534OS, the surface temperature decreases (Fig. 1), indicating more heat is being transferred to the deeper ocean than is entering the system from TOA.

We then explore the impact of declining GHGs on mitigating global warming in the late 21st century using SSP534OS simulations. Our primary focus is on examining the MMM of changes in global energy imbalance from 2051 to 2100, compared to the averaged result from the period 2041-2050 when the mitigation effects are negligible. We observe that mitigation efforts can significantly alter radiative heat fluxes, as indicated by negative changes in the TOA net energy flux (Fig. 2a). These negative changes are attributed to both radiative forcing changes and associated climate feedbacks29, suggesting a reduction in the rate of incoming energy between 2051–2100 and 2041–2050 in the SSP534OS MMM. In contrast to scenarios with increasing GHG concentrations30, the reduction in GHGs enhances outgoing longwave radiation across most regions via reduced external forcing and increased temperature feedback (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, this increase in outgoing longwave radiation is somewhat offset by anomalous downward shortwave radiation, resulting in a noticeable overall decrease in net energy flux at low to middle latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, reaching up to −0.3 PW (1 PW = 1015 W) by the end of the 21st century (Fig. 2a, b). Besides, the Southern Hemisphere middle-high latitudes (30°S–90°S) exhibit the second weakest decline in net radiation heat flux, contributing to negative TOA energy anomalies and reduced energy storage during 2051–2100 relative to 2041–2050 under the SSP534OS scenario.

a Changes in annual mean net energy flux at the top of the atmosphere integrated over 90oS-30oS [multi-model mean (MMM): purple; inter-model spread: light purple], 30oS-60oN (MMM: cyan; inter-model spread: light cyan) and 60oN-90oN (MMM: brown; inter-model spread: light brown) relative to the mean of 2041-2050 in the 8-model SSP534OS simulations. c Annual mean changes in ocean heat uptake integrated over the Arctic Ocean (60°N ~ 90°N; MMM: green; inter-model spread: light green), Atlantic (30°S ~ 60°N; MMM: yellow; inter-model spread: light yellow), Indo-Pacific (30°S–60°N; MMM: blue; inter-model spread: light blue) and Southern Ocean (90°S–30°S; MMM: red; inter-model spread: light red) relative to the mean of 2041-2050 in the 8-model SSP534OS simulations. e As in (c) but for changes in full-depth ocean heat content trend. b Changes in annual mean net energy flux at the top of the atmosphere in the mean of 2051-2100 relative to the mean of 2041–2050 in the 8-model SSP534OS simulations. d, f As in (b) but for changes in ocean heat uptake and full-depth ocean heat content trend. Inter-model spread is denoted by one standard derivation. The stipples in (b, d, f) refer to the regions where at least six of the eight models agree with the sign of the MMM. Curves in (a, c, e) are derived after a 5-year running mean.

The oceans serve as the primary source of the reduced rate in the TOA incoming energy, which releases heat to the atmosphere through heat fluxes at the ocean surface. However, alterations in the OHU exhibit robust regional characteristics in SSP534OS MMM. In the North Atlantic, the enhancement of OHU driven by early GHGs increases persists from 2051 to 2100, showing a positive anomaly of up to 12 W m−2 (Fig. 2d). This positive OHU anomaly is constrained by the turbulent air-sea heat flux feedback via damping the sea surface temperature anomalies and the air-sea surface temperature contrast31,32, indicating that portions of the northern North Atlantic ocean continues to absorb heat from the atmosphere during 2051-2100 relative to 2041-2050, even with a reduction of GHGs in the late 21st century. Consequently, although the ocean releases heat to the atmosphere over the tropical and south Atlantic regions, the overall OHU shows minimal changes when integrated over the entire Atlantic (Fig. 2c). These minimal changes in Atlantic OHU persist through the late 21st century and are not related to the magnitudes of CO2 reduction (Supplementary Fig. 5). Moreover, the Indo-Pacific basin significantly contributes to surface heat release in response to decreasing GHGs, with the Southern Ocean playing a secondary role. This is in contrast to scenarios with increasing GHGs in the SSP585 MMM, where the Southern Ocean primarily absorbs excessive heat. (Fig. 2c, d vs Supplementary Fig. S1c, d).

Changes in ocean heat content trend [Tr(OHC)] reveal distinct patterns in the SSP534OS MMM during the late 21st century. In the North Atlantic, where positive OHU persists, Tr(OHC) suggests a decrease across most of the region, except for a mild increase in the south of Greenland (Fig. 2f). Simultaneously, the Indo-Pacific basin, the primary contributor to heat release at the ocean surface, shows negligible changes in Tr(OHC) until 2070 and a slight decrease afterward. Despite the comparatively weaker changes in OHU, the Southern Ocean accounts for most of the global Tr(OHC) decrease (Fig. 2e). This contrast between regional OHU and Tr(OHC) underscores the importance of heat redistribution, as well as the interbasin heat exchanges, in modulating the heat anomalies in global oceans. Furthermore, the distinct roles played by individual ocean basins in contributing to the global OHU and Tr(OHC) anomaly suggest that, while the response of global mean changes to declining GHGs concentrations might be rapid12,33, the regional patterns exhibit pronounced hysteresis.

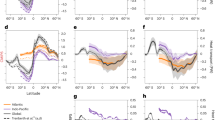

Mechanisms influencing changes in ocean heat uptake and redistribution

To explore the mechanism driving ocean heat anomaly under mitigation efforts, we conducted an ocean heat budget analysis, which links the meridional ocean heat transport convergence/divergence, regional ocean heat uptake and heat storage in each ocean basin (see “Methods”). In the Atlantic basin, even as GHGs concentrations begin to decline, the weakening of the AMOC is prolonged on a multi-decadal timescale (Supplementary Fig. 6), influenced by both the thermal and haline processes22,34. In the SSP534OS MMM, the weakening of the AMOC peaks at up to 3.3 Sv (1 Sv = 106 m3 s−1) between 2051 and 2100 compared to the period from 2041 to 2050 (Fig. 3a). This weakening is accompanied by a reduced northward ocean heat transport (OHT), leading to an ocean heat transport divergence [\(\frac{-\partial \left({OHT}\right)}{\partial y}\) < 0] north of 30°N and a convergence [\(\frac{-\partial \left({OHT}\right)}{\partial y}\) > 0] to the south (Fig. 3b). Meanwhile, the reduced OHT cools the sea surface temperature, amplifying the air-sea surface temperature contrast in the subpolar region35. Consequently, OHU is reinforced there, which, in turn, weakens the AMOC and triggers the redistribution feedback loop35,36,37. This effectively offsets the OHT divergence, resulting in a mild ocean heat storage (OHS) decrease between 45°N-60°N. South of 30°N, negative OHU overweights the effects of OHT convergence, resulting in an overall decrease in OHS. Consistent with the OHS changes, the Atlantic exhibits a robust surface cooling (<−0.28 K decade−1) over the entire basin, primarily confined to the upper 600 m but extending downward to about 1000 m between 45°N and 50°N (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Meanwhile, warming anomalies (>0.12 K decade−1) are observed in the subsurface ocean of the tropical North Atlantic, mainly between 5°N and 30°N. This contrast in surface and subsurface temperature changes reflects an anticorrelation that serves as a fingerprint of the weakened AMOC38,39. The pattern is largely associated with the temperature dome structure in the tropical North Atlantic, as mentioned in previous studies38.

a, c, e Changes in the annual mean Eulerian mean plus eddy-induced MOC in the Atlantic (a), Indo-Pacific (c) and Southern Ocean (e) in the mean of 2051-2100 relative to mean of 2041–2050 in the MMM of the 8-model SSP534OS simulations. Annual mean Eulerian mean plus eddy-induced MOC climatology in the mean of 2041−2050 is shown in (a, c, e), respectively [contours in Sv, with a contour interval of 5 Sv in (a) and (e) but 2 Sv in (c), zero contours thickened and solid (dashed) contours indicating positive (negative) values]. b, d, f Changes in annual mean zonally integrated full-depth oceanic heat budget in the mean of 2051–2100 relative to the mean of 2041-2050: OHU (MMM: blue; inter-model spread: light blue), −∂(OHT)/∂y (MMM: red; inter-model spread: light red) where OHT means ocean heat transport and OHS (MMM: black; inter-model spread: gray) in the Atlantic (b), Indo-Pacific (d) and Southern Oceans (f) in the 8-model SSP534OS simulations. Inter-model spread is denoted by one standard derivation. The stipples in (a, c, e) refer to the regions where at least six of the eight models agree with the sign of the MMM. Curves in (b, d, f) are derived after a 5° running mean.

The impacts of AMOC weakening further extend to the basin boundary, modifying heat transport at basin boundaries, or equivalently, altering interbasin heat exchanges in SSP534OS MMM. During 2051-2100, the circulation anomaly drives an anomalous southward OHT by 70.96 ± 28.47 TW (\(\Delta {\overline{{{{\rm{OHT}}}}}}_{{v}^{{\prime} }}\), methods; 1TW = 1012W) at 30°S, as well as the interbasin heat exchanges between the Atlantic and Southern Ocean compared to the period from 2041 to 2050 (Fig. 4a). This \(\Delta {\overline{{{{\rm{OHT}}}}}}_{{v}^{{\prime} }}\) is slightly compensated by temperature-driven anomaly (\(\Delta {\overline{{{{\rm{OHT}}}}}}_{{\theta }^{{\prime} }}\)), while enhanced by the residual term attributed to other processes such as eddy-driven anomaly and diffusion process40,41. Therefore, \(\Delta {\overline{{{{\rm{OHT}}}}}}_{{v}^{{\prime} }}\) dominates the interbasin heat exchange between the Atlantic and Southern Ocean, accounting for about 72.59 ± 26.34 TW of heat export from the former basin to the latter. The changes in OHT exhibit the same sign and respond similarly in both GHGs increase3,35,41,42 and GHGs decrease scenarios. This suggests a hysteresis effect in interbasin heat exchanges between the Southern Ocean and the Atlantic, primarily driven by circulation anomalies. Note that our study is based on the MMM of eight models, each with an ocean component resolution of approximately 1 degree. These models consistently show negative northward changes in both \(\Delta {{{\rm{OHT}}}}\) and \(\Delta {\overline{{{{\rm{OHT}}}}}}_{{v}^{{\prime} }}\). Recent studies suggested that higher ocean resolution models tend to produce a more rapid decline in the AMOC, due to both mean-state changes and subpolar gyre-induced deep water formation43,44. This implies a stronger reduction in OHT in the Atlantic basin and greater interbasin heat exchanges at the basin boundary.

Changes in annual mean meridional OHT (∆OHT), the components due to ocean circulation alteration (\(\Delta {\overline{{OHT}}}_{{v}^{{\prime} }}\)) and ocean temperature alteration ((\(\Delta {\overline{{OHT}}}_{{\theta }^{{\prime} }}\)) and the residual term (Res) due to the effects of eddies, diffusion and the non-linearity resulting from ocean circulation and temperature changes across the boundaries between the Atlantic and the Southern Oceans (a) and between the Indo-Pacific and the Southern Oceans (b) in the mean of 2051–2100 relative to the mean of 2041-2050 in the 8-model SSP534OS simulations. c, d As in a, c and b, d but for changes in the SPEAR SSP534OS (red), SSP534OS_StrongAMOC (blue) and SSP534OS_EStrongAMOC (green). Results are illustrated as multi-model mean (MMM: dot) ± one standard deviation among models (bars) as well as for each model (colored cross) in (a, b). Results are illustrated as ensemble mean (dot) ± one standard deviation among ensemble members (bars) for each simulation in (c, d). Positive (negative) values indicate anomalous northward (southward) OHT.

Hysteresis in interbasin heat exchanges is also evident between the Southern Ocean and Indo-Pacific. Signals of AMOC weakening can propagate across the basin via wave processes45,46, extending into the Indo-Pacific basin in the form of a geostrophic transport response47. Consequently, this leads to anomalous ocean circulations in that region26,47. In SSP534OS MMM, we observe a formation of an anomalous clockwise meridional overturning circulation in the Indo-Pacific basin, characterized by anomalous northward flow near the surface and southward flow in the deep ocean (Fig. 3c). This anomalous circulation is a persistent response to previous GHGs increasing, acting to partially compensate for the prolonged AMOC weakening42. The circulation changes trigger anomalous northward \(\Delta {\overline{{{{\rm{OHT}}}}}}_{{v}^{{\prime} }}\) at the boundary between the Southern Ocean and Indo-Pacific, reaching up to 119.77 ± 51.60 TW, while the \(\Delta {\overline{{{{\rm{OHT}}}}}}_{{\theta }^{{\prime} }}\) is only −3.37 ± 13.84 TW (Fig. 4b). Therefore, the Indo-Pacific imports anomalous heat by 114.86 ± 45.42 TW from the Southern Ocean, which overwhelms the imported heat from the Atlantic to Southern Ocean.

Connecting the Atlantic and Indo-pacific, the Southern Ocean is influenced by both interbasin heat exchanges and regional changes associated with the wind-driven MOC. In the late 21st century, reduced GHGs weakens the westerly wind in the southern hemisphere (Supplementary Fig. 8), which further modulate the wind-driven Deacon cell in ocean interior. This effect is partially compensated by eddy-induced MOC changes35,48, resulting in a weakening of the residual MOC (Fig. 3e). The weakening of the residual MOC reduces the northward OHT, leading to an overall heat transport divergence over the Southern Ocean (Fig. 3f). As a result, although OHU suggests a slight positive anomaly between 55°S–70°S, the OHS shows a robust decreasing over the Southern Ocean.

To further quantify the contributions of interbasin ocean heat exchanges and regional heat uptake in determining the heat storage anomaly in each ocean basin, we conduct a basin-integrated ocean heat budget analysis (see “Methods”). Our finding indicates that the OHU exerts slight changes in the Atlantic at a rate of 0.60 \(\pm\) 33.36 TW (Fig. 5), due to a compensation between the positive anomalies in the subpolar North Atlantic and negative anomalies in the south. The long term mean interbasin heat exchange at the basin boundaries are also reduced (Fig.5 vs Supplementary Fig. 9), therefore the Atlantic is importing 20.78 \(\pm\) 32.42 TW heat from the Arctic while exporting 72.59 \(\pm\) 26.34 TW heat to the Southern Ocean. In general, the OHS over the Atlantic basin is primarily governed by the interbasin exchanges, resulting in a net decrease of 51.72 \(\pm\) 43.12 TW.

Ocean basins defined in this study for the basin integration: the Arctic Ocean (light red, 60°N–90°N), Atlantic Ocean (light brown, 30°S–60°N), the Indo-Pacific (light blue, 30°S–60°N) and the Southern Ocean (light green, 90°S–30°S).Changes in annual mean regional-integrated net energy flux at the top of atmosphere (vectors, orange), atmospheric energy transport at 30°S and 60°N (vectors, purple), annual mean basin-integrated ocean heat uptake (vectors, red), interbasin heat exchanges (vectors, blue) and annual mean basin-integrated ocean heat storage (black) in individual ocean basin in the mean of 2051–2100 relative to the mean of 2041–2050 in the 8-model SSP534OS simulations. The numbers are presented in the form of multi-model mean \(\pm\) one standard deviation among the 8 models in the unit of TW (1TW = 1012W).

In the Indo-Pacific basin, a total of 147.92 \(\pm\) 36.28 TW heat is released to the atmosphere in the form of negative surface heat fluxes. However, the majority of the heat release does not originate locally but rather comes from the Southern Ocean through interbasin heat exchanges. Due to the anomalous ocean circulations, the Indo-Pacific imports 114.86 \(\pm\) 45.42 TW of heat from the Southern Ocean and 0.97 \(\pm\) 5.12 TW from the Arctic. It is worth noting that the meridional atmospheric heat transport at 30°S and 60°N is 8.45 \(\pm\) 40.45 TW and 6.54 \(\pm \,\)31.72 TW, respectively. These values are substantially smaller compared to the OHU anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 10, see “Methods”), therefore most of the released heat from the ocean surface is further emitted to the space, explaining the strong reduction in the rate of TOA incoming energy at low-middle latitudes (Fig. 5). In summary, both OHU and interbasin heat exchanges exhibit strong anomalies, yet their impacts are counteractive. This results in a mild OHS decrease at a rate of 32.14 \(\pm\) 51.77 TW in the Indo-Pacific. As a result, OHC in the Indo-Pacific persistently increases throughout the 21st century although the increasing rate is declined with GHGs decline (Supplementary Fig. 11b).

The Southern Ocean plays a crucial role as a primary source of reduction in global TOA incoming energy in response to mitigation efforts in the late 21st century. About 66.62 \(\pm\) 33.51 TW heat is locally released to the atmosphere via negative OHU. Meanwhile, the Southern Ocean imports heat from the Atlantic and exports heat to the Indo-Pacific, resulting in a net energy export of 42.26 ± 38.22 TW at the basin boundary. Both the interbasin heat exchanges and changes in OHU contribute positively to the decrease of OHS over the Southern Ocean, leading to a remarkable reduction of 108.36 ± 60.90 TW (Fig. 5), along with a subsurface cooling in the upper 800 m over the basin (Supplementary Fig. 7a).

Role of the weakened AMOC in altering global heat anomalies

To further clarify the impact of the AMOC weakening on the hysteresis of regional ocean heat anomaly under mitigation efforts, we conduct two additional simulations with SPEAR. These simulations, named SSP534OS_StrongAMOC and SSP534OS_EStrongAMOC, involve the removal of freshwater by 0.1 Sv and 0.2 Sv over the subpolar North Atlantic21, respectively. This action consequently increases upper ocean salinity and density, artificially promoting the AMOC recovery in response to GHGs decrease. In both SSP534OS_StrongAMOC and SSP534OS_EStrongAMOC, the AMOC demonstrates a rapid recovery since 2041 (Supplementary Fig. 6).

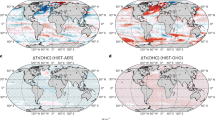

We observe that the AMOC state largely determines the differences of responses in energy balance in these runs (Fig. 6). At the TOA, energy fluxes exhibit downward positive anomalies with AMOC recovery instead of negative anomalies in SSP534OS above the North Atlantic region (Fig. 6a. vs Fig. 6b, c). Besides, at the ocean surface, the OHU enhancement is notably reduced and eastward shifted in the SSP534OS_StrongAMOC and SSP534OS_EStrongAMOC in the North Atlantic, particularly over the Labrador Sea where the OHU shows a weakening rather than an enhancement compared to the SSP534OS (Fig. 6d. vs Fig. 6e, f). Similarly, in the Tropical and South Atlantic regions, the negative OHU anomaly observed in the SSP534OS is replaced by positive anomaly due to the AMOC recovery. Unlike the changes in OHU, Tr(OHC) is increased over the subpolar North Atlantic regions in these two sensitivity runs (Fig. 6g vs Fig. 6h, l). This indicates that the enhanced northward OHT carried by the recovered AMOC outweighs the surface heat release, leading to positive heat storage anomalies in those areas. The differences between the SSP534OS, and the SSP534OS_StrongAMOC /SSP534OS_EStrongAMOC further confirm that the prolonged enhancement of OHU and decline of Tr(OHC) in the Atlantic basin in SSP534OS are attributed to the persistent weakening of the AMOC.

Changes in annual mean net energy flux at the top of the atmosphere (a), ocean heat uptake (d) and full-depth ocean heat content trend (g) in the mean of 2051-2100 relative to the mean of 2041-2050 in the ensemble mean of SPEAR SSP534OS simulations. b, e, h As in (a, b), (d, e), (g, h) but for changes in ensemble mean of SSP534OS_StrongAMOC. c, f, i As in (a, c), (d, f), (g, i) but for changes in ensemble mean of SSP534OS_EStrongAMOC. The stipples in each panel refer to the regions where at least two-thirds of the ensemble members agree with the sign of the ensemble mean.

We also observe differences of interbasin heat exchanges in these runs, which again is due to different AMOC states. In SSP534OS_StrongAMOC, we observe a significant decline in circulation-driven heat export from the Atlantic to the Southern Ocean compared to SSP534OS (Fig. 4c). In SSP534OS_EStrongAMOC, characterized by a stronger AMOC recovery, the Atlantic is even importing heat rather than exporting it to the Southern Ocean. Temperature-driven interbasin heat exchanges remain relatively smaller in either simulation, highlighting the dominant role of circulation changes, or more straightforward, the AMOC weakening, in explaining of heat exchanges between the Atlantic and Southern Ocean in the late 21st century in SSP534OS. At the boundary between the Indo-Pacific and Southern Ocean, the heat export from the Southern Ocean to the Indo-Pacific basin is decreased along with a recovered AMOC (Fig. 4d). Although the changes are relatively weaker, they are statistically significant in t-test between SSP534OS and SSP534OS_StrongAMOC (P = 0.06), and between SSP534OS and SSP534OS_EStrongAMOC (P < 0.01), thus identifying the significant role of AMOC weakening in contributing to the hysteresis of interbasin heat exchanges.

Discussion

In this study we assess how the global energy budget would be modified in response to theoretical reductions in greenhouse gases in the late 21st century. Along with the global mean cooling trend, we find that significant regional variations in ocean heat uptake and storage would occur and are linked to ocean dynamics. In the North Atlantic, enhanced OHU persists alongside prolonged AMOC weakening, which reduces northward ocean heat transport and leads to heat redistribution within the Atlantic basin. Circulation anomalies also dominate OHT changes, resulting in hysteresis in interbasin heat exchanges at the basin boundary, prescribed as heat export from the Atlantic to the Southern Ocean and heat import to the Indo-Pacific from the Southern Ocean. The latter further contributes to strongest OHS decrease in the Southern Ocean with the concurrent negative OHU driven by GHGs decline. Consequently, the Southern Ocean serves as the heat exchanger in global oceans. On the contrary, the hysteresis in interbasin heat exchanges, prescribed as heat importing from the Southern Ocean largely compensates for the negative OHU in the Indo-Pacific, resulting in a mild decrease in OHS along with pronounced ocean heat content increase through the late 21st century. Our results highlight the hysteresis of regional OHU, heat transport and OHS and identify the crucial role of prolonged AMOC weakening in it. These findings are crucial for society, given their roles in modulating thermal changes and thus potential impacts on regional sea level rise and monsoon systems.

Additionally, the prolonged weakening of the AMOC also contributes to the irreversibility of the ocean’s response to GHGs concentration. This irreversibility implies that even if GHG concentrations return to previous level due to mitigation efforts, the mean state of some regional climates may differ from their earlier conditions15,16,20,22,23,29,49. For example, the interbasin heat exchanges between the Southern Ocean and Atlantic/Indo-Pacific show significant anomalies during 2081-2090 compared to 2041-2050, even though CO2 concentration are similar in both decades (Supplementary Fig. 5). This irreversibility is linked to prolonged circulations anomalies, which weaken the mean ocean heat transport in individual ocean basins. As a result, poleward OHT could be weaker in the future compared to historical levels, even with the same CO2 concentration.

However, ocean circulation changes exhibit large inter-model discrepancies in response to GHGs changes50. In the North Atlantic, variations in the AMOC contribute to considerable uncertainty in simulated warming and changes in the hydrological cycle51. Besides, the AMOC’s response to GHGs changes is time-dependent: it shows a deceleration on multi-decadal timescale but may recovery after about one or several centuries, whether under a stabilization scenario52 or in an abrupt CO2 increase experiment53. The slow AMOC recovery is accompanied with reversed changes in OHU in the North Atlantic and a meridional shift in the tropical rainfall belt54. Therefore, it is crucial to reduce discrepancies in the timescale and magnitude of AMOC variations in response to sustained GHG levels for more accurate future projections.

Methods

Climate model simulations

To investigate the changes in global heat during the late 21st century, we conducted simulations using the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) SPEAR model28. The resolution is approximately 0.5 degree for the atmosphere and land components, and about 1 degree for the sea ice and ocean components with refinement to 1/3 degree near the equator. The atmosphere component has 33 vertical layers, while the ocean component comprises 75 vertical layers. The simulations incorporate two distinct scenarios: SSP5-8.5 and SSP5-3.4OS. SSP5-8.5 is characterized by a substantial increase in GHGs emissions from 2015-2100, representing climate change driven by GHGs-induced global warming. In contrast, SSP5-3.4OS shares a similar forcing trajectory with SSP5-8.5 until 2040. However, after this point, there is a rapid decline in CO2 and CH4 concentrations with strong mitigation efforts, achieving net-zero CO2 emissions therefore a CO2 concentration peak at 550 ppm around 2060, with further reductions in CO2 concentrations thereafter. At the end of 21st century, the CO2 concentration is about 1130 ppm and 500 ppm in SSP5-8.5 and SSP5-3.4OS respectively. To reduce the uncertainty arising from the internal variability, we conducted 30 ensemble simulations, each with different perturbations at the initial conditions for both scenarios. Different from previous studies conducting idealized CO2 concentrations increasing and decreasing experiments16,22,23,25,29,33, SSP585 and SSP534OS scenarios are generated based on assumption about various human developments, therefore is more valuable for future climate projections.

Two additional simulations stemming from SSP5-3.4OS, namely SSP534OS_StrongAMOC and SSP534OS_EStrongAMOC21 (“E” stands for extremely), were conducted using the SPEAR model to explore the role of AMOC changes on global heat anomalies. In these simulations, we remove freshwater from the North Atlantic subpolar gyre region and Nordic Seas (50°N–80°N) at rates of 0.1 Sv and 0.2 Sv, respectively. The removal of surface freshwater increases the surface salinity and density, therefore enhancing the North Atlantic deep-water formation and consequently strengthening the AMOC. For each simulation, 9 ensemble members were used from 2041 to 2100. At the end of the simulation, the AMOC recovers to the early 21st century level in SSP534OS_StrongAMOC. Conversely, in SSP534OS_EStrongAMOC, the AMOC exhibits a more robust recovery with an overshooting of about 2 Sv.

In addition to the simulations performed with SPEAR, we used SSP534OS simulation from 7 CMIP6 models (CanESM5, CNRM-ESM2-1, FGOALS-g3, GISS-E2-1-G, MRI-ESM2-0, NorEMS2-LM, UKESM1-0-LL; Supplementary Table. 1), where the required variables for the ocean heat budget analysis are available. We analyzed the SSP534OS simulations from both the 7 CMIP6 models and the SPEAR model. For each model, we conduct the monthly output of the variables for ocean circulations, energy fluxes and heat budget terms. We initially interpolate all variables on 1 degree \(\times\) 1 degree latitude-longitude grid and calculate the changes over the period 2051–2100 relative to 2041–2050 in the ensemble mean. Subsequently, we computed the multi-model mean and the inter-model spread expressed as one standard deviation.

Ocean heat budget analysis

In the present study, we conduct a heat budget analysis that links the meridional heat transport convergence/divergence, OHU and OHS11,26,35,48. Specifically, the zonal-integrated full-depth oceanic heat budget in each ocean basin is

where \(\rho\)0 is seawater density, Cp is the specific heat of sea water, \(\theta\) is potential temperature of sea water, -H denotes the depth of ocean bottom. SHF denotes net surface heat flux. \(\nabla\) and v are three-dimensional gradient operator and velocity. D denotes diffusion and other subgrid processes. West and East indicate the longitudes of the western and eastern boundaries of individual ocean basin at a specific latitude.

Based on Eq. (1), we define OHC as

and OHC tendency as the OHS:

and OHU as

and meridional ocean heat transport as

Therefore we rewrite the zonal-integrated full-depth oceanic heat budget of Eq. (1) as

The heat budget suggests that the OHS is determined by the OHU at the ocean surface and the meridional OHT gradient, as well as the meridional OHT convergence and divergence.

Specifically, we analyze the changes in the OHS, OHU and \(\frac{\partial }{\partial y}{OHT}\) during the mean of 2051–2100 relative to the mean of 2041–2050 as

where \(\Delta\) denotes the changes between the two periods. \(\Delta {OHS}\) also refers to the changes in the OHC trend [\(\Delta {Tr}\left({OHC}\right)\)] as

where \({Tr}\left({OHC}\right)\) refers to the OHC trend during 2051-2100 in each simulation. Tr(OHCcontrol) reflects a temperature drift in the control run, which may not necessarily be zero and is calculated in the 100-year control-run in each simulation.

Similarly, we also conduct the basin-integrated full-depth oceanic heat budget in each ocean basin26,35, which is defined as

where {.} indicates the basin integration. OHTnorth and OHTsouth denote the northward ocean heat transport across the northern and southern boundary respectively, which refers to the interbasin heat exchanges.

And changes in the basin-integrated full-depth oceanic heat budget over the mean of 2051–2100 relative to 2041–2050 is

which indicates that changes in the OHS in each basin is determined by the regional OHU and also the interbasin exchanges at the basin boundaries.

To reveal the role of ocean circulation anomalies in modifying the \(\Delta {OHT}\), we further decompose the changes in \(\Delta {OHT}\) into the component driven by ocean circulation anomalies (\(\Delta {\overline{{OHT}}}_{{v}^{{\prime} }}\)), temperature anomalies (\(\Delta {\overline{{OHT}}}_{{\theta }^{{\prime} }}\)) and residual term (\({Res}\)):

\(\Delta {\overline{{OHT}}}_{{v}^{{\prime} }}\) is calculated as

where \(v{\prime}\) denotes the changes in Eulerian-mean velocity and \(\bar{{\theta }_{0}}\) denotes the climatological ocean temperature in the mean of 2041-2050. \(\Delta {\overline{{OHT}}}_{{\theta }^{{\prime} }}\) is calculated as

where \({\theta }^{{\prime} }\) denotes changes in ocean temperature and \(\bar{{v}_{0}}\) denotes the climatological ocean velocity in the mean of 2041–2050.

Atmospheric heat transport

We also analyze the changes meridional atmospheric heat transport (AHT; Supplementary Fig. 10). Compared with the net energy fluxes at the TOA and the net heat fluxes at the surface, changes in atmospheric heat storage are neglectable with small heat capacity of air parcel, therefore we define the AHT at a certain latitude \(\alpha\) as the difference between the integrated net downward energy fluxes at the TOA (FTOA) and integrated net downward heat fluxes at the surface (FSUR) which is calculated as

FTOA and FSUR are integration of net downward energy fluxes at the TOA and net downward heat fluxes at the surface in a polar cap up to a certain latitude \(\alpha\), and are calculated as

where \(\phi\), \(\lambda\) and r denote latitude, longitude and the Earth’s radius. \({{Energy}}_{{TOA}}\) and \({{Energy}}_{{surface}}\) denote net downward energy flux at the TOA and net downward heat flux at the ocean/land surface, respectively. Note here, to ensure the transport is zero at the poles, the global mean energy imbalance is removed from the integration55.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

CMIP6 model data is available at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/. The data of SPEAR simulation is available at https://www.gfdl.noaa.gov/spear/.

Code availability

Figures are generated via the NCAR Command Language (NCL, Version 6.5.0) [Software]. (2018). Boulder, Colorado: UCAR/NCAR/CISL/TDD (https://doi.org/10.5065/D6WD3XH5). The data and codes used to generate Figs.1–4 and Fig. 6 are available via Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/13955518.

References

Frölicher, T. L. et al. Dominance of the Southern Ocean in anthropogenic carbon and heat uptake in CMIP5 models. J. Clim. 28, 862–886 (2015).

Zanna, L., Khatiwala, S., Gregory, J. M., Ison, J. & Heimbach, P. Global reconstruction of historical ocean heat storage and transport. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1126–1131 (2019).

Garuba, O. A. & Klinger, B. A. Ocean heat uptake and interbasin transport of the passive and redistributive components of surface heating. J. Clim. 29, 7507–7027 (2016).

Rhein, M., et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds. Stocker, T. F. et al.) 255–316 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Irving, D. B., Wijffels, S. & Church, J. A. Anthropogenic aerosols, greenhouse gases, and the uptake, transport, and storage of excess heat in the climate system. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 4894–4903 (2019).

Cheng, L. et al. Improved estimates of ocean heat content from 1960 to 2015. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601545 (2017).

Murakami, H., Levin, E., Delworth, T. L., Gudgel, R. & Hsu, P. C. Dominant effect of relative tropical Atlantic warming on major hurricane occurrence. Science 362, 794–799 (2018).

Vermeer, M. & Rahmstorf, S. Global sea level linked to global temperature. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21527–21532 (2009).

Slangen, A. B. et al. Anthropogenic forcing dominates global mean sea-level rise since 1970. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 701–705 (2016).

Shi, J. R., Xie, S. P. & Talley, L. D. Evolving relative importance of the Southern Ocean and North Atlantic in anthropogenic ocean heat uptake. J. Clim. 31, 7459–7479 (2018).

Ma, X., Liu, W., Allen, R. J., Huang, G. & Li, X. Dependence of regional ocean heat uptake on anthropogenic warming scenarios. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc0303 (2020).

Wu, P., Wood, R., Ridley, J. & Lowe, J. Temporary acceleration of the hydrological cycle in response to a CO2 rampdown. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37 (2010).

Kug, J. S. et al. Hysteresis of the intertropical convergence zone to CO2 forcing. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 47–53 (2022).

Cao, L., Bala, G. & Caldeira, K. Why is there a short‐term increase in global precipitation in response to diminished CO2 forcing? Geophys. Res. Lett. 38 (2011).

Oh, H. et al. Contrasting hysteresis behaviors of Northern hemisphere land monsoon precipitation to CO2 pathways. Earth’s Future 10, e2021EF002623 (2022).

Song, S. Y. et al. Asymmetrical response of summer rainfall in East Asia to CO2 forcing. Sci. Bull. 67, 213–222 (2022).

Garbe, J., Albrecht, T., Levermann, A., Donges, J. F. & Winkelmann, R. The hysteresis of the Antarctic ice sheet. Nature 585, 538–544 (2020).

Frölicher, T. L. & Joos, F. Reversible and irreversible impacts of greenhouse gas emissions in multi-century projections with the NCAR global coupled carbon cycle-climate model. Clim. Dyn. 35, 1439–1459 (2010).

Jiang, J. et al. Response of ocean acidification to atmospheric carbon dioxide removal. J. Environ. Sci. 140, 79–90 (2023).

Wu, P., Ridley, J., Pardaens, A., Levine, R. & Lowe, J. The reversibility of CO 2 induced climate change. Clim. Dyn. 45, 745–754 (2015).

Delworth, T. L., Cooke, W. F., Naik, V., Paynter, D. & Zhang, L. A weakened AMOC may prolong greenhouse gas–induced Mediterranean drying even with significant and rapid climate change mitigation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2116655119 (2022).

An, S. I. et al. Global cooling hiatus driven by an AMOC overshoot in a carbon dioxide removal scenario. Earth’s Future 9, e2021EF002165 (2021).

Oh, J. H., An, S. I., Shin, J. & Kug, J. S. Centennial memory of the Arctic Ocean for future Arctic climate recovery in response to a carbon dioxide removal. Earth’s Future 10, e2022EF002804 (2022).

Sgubin, G., Swingedouw, D., Drijfhout, S., Hagemann, S. & Robertson, E. Multimodel analysis on the response of the AMOC under an increase of radiative forcing and its symmetrical reversal. Clim. Dyn. 45, 1429–1450 (2015).

Wu, P., Jackson, L., Pardaens, A. & Schaller, N. (2011). Extended warming of the northern high latitudes due to an overshoot of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L24704 (2011).

Li, S. & Liu, W. (2022). Impacts of Arctic sea ice loss on global ocean circulations and interbasin ocean heat exchanges. Clim. Dyn. 59, 2701–2716 (2022).

Chen, C., Liu, W. & Wang, G. Understanding the uncertainty in the 21st century dynamic sea level projections: The role of the AMOC. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 210–217 (2019).

Delworth, T. L. et al. SPEAR: The next generation GFDL modeling system for seasonal to multidecadal prediction and projection. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001895 (2020).

Song, S. Y. et al. (2023). Climate sensitivity controls global precipitation hysteresis in a changing CO2 pathway. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 156 (2013).

Donohoe, A., Armour, K. C., Pendergrass, A. G. & Battisti, D. S. Shortwave and longwave radiative contributions to global warming under increasing CO2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 16700–16705 (2014).

Hausmann, U., Czaja, A. & Marshall, J. Mechanisms controlling the SST air-sea heat flux feedback and its dependence on spatial scale. Clim. Dyn. 48, 1297–1307 (2017).

Zhang, L. & Cooke, W. Simulated changes of the Southern Ocean air-sea heat flux feedback in a warmer climate. Clim. Dyn. 56, 1–16 (2021).

Oh, J. H. et al. Emergent climate change patterns originating from deep ocean warming in climate mitigation scenarios. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 260–266 (2024).

Jackson, L. C., Schaller, N., Smith, R. S., Palmer, M. D. & Vellinga, M. Response of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation to a reversal of greenhouse gas increases. Clim. Dyn. 42, 3323–3336 (2014).

Li, S., Liu, W., Allen, R. J., Shi, J. R. & Li, L. (2023). Ocean heat uptake and interbasin redistribution driven by anthropogenic aerosols and greenhouse gases. Nat. Geosci. 16, 695–703 (2023).

Couldrey, M. P. et al. What causes the spread of model projections of ocean dynamic sea-level change in response to greenhouse gas forcing? Clim. Dyn. 56, 155–187 (2021).

Huguenin, M. F., Holmes, R. M. & England, M. H. Drivers and distribution of global ocean heat uptake over the last half century. Nat. Commun. 13, 4921 (2022).

Wang, C. & Zhang, L. Multidecadal ocean temperature and salinity variability in the tropical North Atlantic: Linking with the AMO, AMOC, and subtropical cell. J. Clim. 26, 6137–6162 (2013).

Zhang, R. Anticorrelated multidecadal variations between surface and subsurface tropical North Atlantic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34 (2007)

Yang, H., Li, Q., Wang, K., Sun, Y. & Sun, D. Decomposing the meridional heat transport in the climate system. Clim. Dyn. 44, 2751–2768 (2015).

Mecking, J. V. & Drijfhout, S. S. The decrease in ocean heat transport in response to global warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 1229–1236 (2023).

Sun, S., Thompson, A. F., Xie, S. P. & Long, S. M. Indo-Pacific warming induced by a weakening of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. J. Clim. 35, 815–832 (2022).

Roberts, M. J. et al. Sensitivity of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation to model resolution in CMIP6 HighResMIP simulations and implications for future changes. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS002014 (2020).

Hewitt, H. T. et al. Resolving and parameterizing the ocean mesoscale in earth system models. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 6, 137–152 (2020).

Sévellec, F. & Fedorov, A. V. The leading, interdecadal eigenmode of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation in a realistic ocean model. J. Clim 26, 2160–2183 (2013).

Newsom, E. R. & Thompson, A. F. Reassessing the role of the Indo-Pacific in the ocean’s global overturning circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 12422–12431 (2018).

Sun, S., Thompson, A. F. & Eisenman, I. (2020). Transient overturning compensation between Atlantic and Indo-Pacific basins. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 50, 2151–2172 (2020).

Liu, W., Lu, J., Xie, S. P. & Fedorov, A. Southern Ocean heat uptake, redistribution, and storage in a warming climate: the role of meridional overturning circulation. J. Clim. 31, 4727–4743 (2018).

Held, I. M. et al. Probing the fast and slow components of global warming by returning abruptly to preindustrial forcing. J. Clim. 23, 2418–2427 (2010).

Weijer, W., Cheng, W., Garuba, O. A., Hu, A. & Nadiga, B. T. CMIP6 models predict significant 21st century decline of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086075 (2020).

Bellomo, K., Angeloni, M., Corti, S. & von Hardenberg, J. Future climate change shaped by inter-model differences in Atlantic meridional overturning circulation response. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–10 (2021).

Cheng, W., Chiang, J. C. & Zhang, D. Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) in CMIP5 models: RCP and historical simulations. J. Clim. 26, 7187–7197 (2013).

Bonan, D. B., Thompson, A. F., Newsom, E. R., Sun, S. & Rugenstein, M. Transient and equilibrium responses of the Atlantic overturning circulation to warming in coupled climate models: The role of temperature and salinity. J. Clim. 35, 5173–5193 (2022).

Liu, W., Li, S., Li, C., Rugenstein, M., & Thomas, A. P. Contrasting fast and slow intertropical convergence zone migrations linked to delayed Southern Ocean warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 732–739 (2024).

Feldl, N., Po-Chedley, S., Singh, H. K., Hay, S. & Kushner, P. J. Sea ice and atmospheric circulation shape the high-latitude lapse rate feedback. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 3, 41 (2020).

Acknowledgements

S.L. is supported under award NA23OAR4320198 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. designed the research, conducted analysis, performed the visualization, and wrote the manuscript. S.L., L.Z., T.L.D., W.F.C., S.S., and Q.G. convinced the study and improved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Federico Fabiano, Hemant Khatri and Fabio Boeira Dias for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Viviane V. Menezes and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Zhang, L., Delworth, T.L. et al. Mitigation-driven global heat imbalance in the late 21st century. Commun Earth Environ 5, 651 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01849-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01849-y