Abstract

Carbon dioxide removal is crucial for moderating the rapid pace of power sector transformation, while electrification can reduce the emission intensity of the carbon removal process. Here, we use a multisector model to explore the impact of varying levels of CO2 removal (1 to 10 gigatonnes CO2 per year) on the electricity sector by 2050 under 1.5 °C and 2 °C future warming. Our results show that under high CO2 removal pathways, up to 5% of electricity consumption could be dedicated to removing CO2. Limited CO2 removal by 2050 could increase asset stranding costs by US$165-225 billion in fossil-intensive countries like China, the US, and India. Also, a 15% additional mitigation of committed emissions in the power sector would be needed under constrained CO2 removal pathways. While a high CO2 removal future is key to alleviating the burden of power sector transformation, it carries the risk of increased committed emissions. Careful planning is required to balance a less disruptive transformation without compromising climate targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Paris Agreement aims to limit global warming to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, with an aspirational goal of limiting the increase to 1.5 °C by 21001,2. Central to achieving these targets is the concept of the remaining carbon budget (RCB), which refers to the maximum amount of anthropogenic net carbon dioxide (CO2) that can be emitted while keeping global warming below a given limit with a given probability3. Current estimates indicate that the RCB for a 50% chance of keeping warming to 1.5 °C will be exhausted within the next 5 years4,5, highlighting the urgent need for rapid and unprecedented decarbonization across all sectors. The electricity sector, in particular, plays a critical role in this transition. Decarbonizing the electricity sector is crucial for achieving the Paris Agreement goal, as it is responsible for about 40% of current global emissions6. However, the sector has the potential to transition rapidly through diverse low-carbon technologies, enabling substantial CO₂ reductions across multiple sectors via clean electrification7. It is essential not only for decarbonizing other sectors reliant on fossil fuel-generated electricity but also for providing the green electricity needed to produce green hydrogen and its derivatives, which are crucial for the deep decarbonization of hard-to-abate sectors like heavy industry and aviation8,9.

However, the rapid decarbonization of the electricity sector could present a highly disruptive transition. Technically, the expansion of the grid to accommodate high shares of variable renewable energy10, the development of large-scale storage solutions to manage the variability of wind and solar power7,11, and the extraction of critical minerals required for renewable technologies12,13 all pose major transition challenges. Socio-economically, the shift away from fossil fuels could lead to substantial job losses in the fossil fuel industry14,15. In addition, there is also the issue of stranded assets. Stranded assets refer to investments in fossil fuel infrastructure that may become obsolete or uneconomical as the world transitions to cleaner energy sources16. According to the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), unburned fossil fuels and stranded fossil fuel infrastructure are projected to have a discounted global value of approximately USD 1–4 trillion from 2015 to 2050 in scenarios that aim to limit global warming to around 2 °C. The estimated value increases further for pathways targeting a 1.5 °C warming limit2.

Given these challenges, a critical question arises: is it possible to achieve the Paris Agreement’s climate targets without incurring the negative socio-economic and technical consequences associated with rapid electricity sector decarbonization? The answer may lie in carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies. CDR technologies will play a pivotal role in mitigating climate change by removing CO2 from the atmosphere and can offset emissions to achieve specific climate targets. Example of these CDR approaches include Direct Air Capture with Carbon Storage (DACCS), Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), afforestation, biochar, and enhanced weathering17. CDR can slow the rate of decarbonization needed in the short term by offsetting emissions later18,19, thus acting as backstop technologies to cut emissions in a cost-effective manner20. For example, if the availability of future CDR could reach at least 8 gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2/year by 2050, instead of just 1 GtCO2/year, the cost of achieving net zero emissions by 2050 could be lowered, from US$2700/tCO2 to <US$1500/tCO221. A similar study18 also reveals that China and the rest of the world could get to net zero by 2060 at a marginal cost of over US$800/tCO2 in the absence of DAC, but its availability would reduce this cost to between US$200 and 400/tCO2.

Based on these characteristics and roles, CDR technologies could address one of the major issues associated with rapid and deep decarbonization: stranded assets. Despite the potential of CDR to mitigate the premature retirement of existing power plants, quantitative studies that investigate the impact of these technologies on stranded assets in the power sector remain limited. Existing literature has primarily focused on quantifying the capacity and cost of stranded assets resulting from decarbonization efforts aligned with the Paris Agreement. Several studies14,16,22,23,24,25,26 have explored the implications of these stranded assets for climate goals across various regions, examining economic impacts, sectoral transitions, and policy responses. While previous research has highlighted critical aspects of power sector decarbonization, a critical gap remains—we need to better understand how CDR interacts with and complements efforts to decarbonize electricity generation. The feasibility of achieving the necessary scale of CDR—up to 10 GtCO2 removal per year by mid-century27—faces substantial technical, socio-economic, environmental, and political barriers28,29, necessitating a deeper examination of their role in the power sector transformation. While previous research has only begun exploring the connection between CDR deployment and stranded assets in the power sector30, our study builds on this prior work in several ways.

First, considering the varying potential outcomes for the future success of CDR, we deploy various future scales of novel CDR technologies, ranging from 1 to 10 GtCO₂ by 2050, to assess their impact on the electricity sector transformation and stranded asset risks. Secondly, we evaluate CDR deployment under both 1.5 and 2 °C warming targets, providing new insights into how these technologies could help minimize disruption to the electricity sector transition under different climate ambition levels. Also, most global analyses provide valuable insights for policymakers but often overlook regional differences and sectoral transformational requirements needed across different countries and regions. This study offers a global analysis while highlighting how different regions and countries respond to varying levels of CDR deployment in their electricity sectors. Furthermore, different countries may prioritize different types of CDR technologies based on their unique resources. Countries with abundant land and biomass may favor BECCS and biochar, while those with suitable geological sites but limited land may prefer DACCS21. Recent studies have suggested that co-deploying various CDR types may have fewer negative impacts compared to relying on a single technology31,32. We also examine six different CDR types—afforestation/reforestation (AR), BECCS, biochar, enhanced rock weathering (ERW), DACCS, and direct ocean capture and carbon storage (DOCCS)—to assess how their full availability might affect global and regional electricity sector transformations compared to scenarios with fewer available options. Additionally, we consider the concept of committed emissions, which refer to the future CO2 emissions associated with existing and planned power plants33. While CDR technologies could reduce the need for aggressive electricity sector transformations and mitigate stranded assets, they might also allow for higher committed emissions from power plants than if these technologies were absent. We quantify this trade-off by assessing the committed emissions tied to different CDR success rates under various climate targets, providing a comprehensive view of their potential impact on the power sector. Finally, we examine the crucial relationship between CDR pathways and the electricity sector, recognizing that certain CDR technologies can largely influence both the demand and supply dynamics of the sector—an interaction often overlooked in existing literature, where these systems are typically analyzed in isolation. For example, DACCS can substantially increase electricity demand due to its energy-intensive processes, whereas BECCS uniquely contributes to electricity supply while simultaneously capturing CO₂ emissions. Table 1 provides a general summary of the scenarios explored in this study.

From a modeling perspective, our approach to representing the range of potential future outcomes for CDR differs from those commonly seen in existing IAM studies. Unlike most previous studies where CDR is endogenously deployed19,34,35, we explicitly set caps on the amount of negative emissions available for deployment in each modeling period. The problem with endogenously deployed CDR is that it offers a cost-effective approach to reaching climate targets by lowering the carbon price36, which in turn reduces the pace of emission reductions. This allows residual emissions to be offset later at a cheaper mitigation cost18,19,20. This approach can lead to the perpetuation of fossil fuels and higher levels of residual emissions21, causing the 1.5 °C carbon budget to be overshot for several decades before returning to safer levels towards the end of the century. Our approach avoids this situation by forcing emission reductions and removals to be pursued separately without one undermining the other, as advocated in recent studies37,38. This method allows us to assess the implications of varying CDR levels on power sector transformation under different climate targets.

Our analysis reveals that different levels of CDR deployment can influence electricity sector transformation pathways. With respect to electricity demand and supply, we find that CDR technologies (excluding BECCS and AR), consume electricity, potentially using 1–4% of global electricity by 2050, while BECCS uniquely contributes 2–4% to electricity supply. Regional impacts vary considerably, with some areas leveraging BECCS for electricity generation while others dedicate substantial renewable capacity to power CDR processes. Limited CDR deployment (1 GtCO2 by 2050) requires up to $9 trillion in additional renewables and nuclear investment compared to scenarios with higher CDR deployment (10 GtCO2). While greater CDR availability can reduce stranded assets by up to 25% and save approximately US$500 billion in stranding costs, it also leads to 12%-15% higher committed emissions by extending the lifespan of emissions-intensive infrastructure.

Results and discussion

CDR deployment

Understanding the complex interaction between CDR pathways and the global electric power system requires examining the roles and contributions of various CDR approaches in achieving climate mitigation goals. Figure 1a illustrates the development and distribution of CDR methods across different modeled scenarios. Land use change (LUC) plays a crucial role, especially in the LOW scenario, which relies solely on LUC for negative emissions until the last decade (2040–2050) when DACCS emerges. In scenarios where a broader portfolio of novel CDR technologies is adopted, the burden of negative emissions is partially shifted away from LUC, with its contribution to total CDR decreasing by 25–40% and 40–60% under the MODERATE and HIGH scenarios, respectively, relative to the LOW scenario by 2050, as these new technologies become more mature and cost-effective39. Although DACCS deployment is relatively delayed, it becomes a principal CDR approach under the 1.5 °C pathway, with gross removals reaching 3.3 GtCO2/yr by 2050 in the HIGH scenario. The 2 °C pathway’s less stringent requirements may allow for a further delay in DACCS deployment, likely towards the end of the century, providing time for technological advancements and cost reductions. Due to cost-effectiveness, high-temperature electric-powered DACCS systems are deployed at a much lower scale compared to natural gas-based systems across all scenarios. Despite the limited deployment of the fully electric system, its energy-intensive nature poses major implications for electricity demands. BECCS deployment is expected to begin relatively early, around 2030. Under the HIGH scenario for both 1.5 and 2 °C pathways, BECCS would become the predominant source of negative emissions by 2050, delivering 4.6 and 2.9 GtCO2/yr, respectively. The 1.5 and 2 °C pathways show notable differences in BECCS deployment across sectors. In the 1.5 °C pathway, BECCS-electricity dominates over BECCS-liquids, reflecting a prioritization of deep decarbonization in the power sector and an emphasis on electrification as a key mitigation strategy. Conversely, the 2 °C pathway has a higher share of BECCS-liquids relative to BECCS-electricity, indicating a reduced emphasis on electrification and sector coupling. While BECCS and DACCS are expected to be the most widely deployed forms of novel CDR, enhanced weathering and biochar also play important roles in providing negative emissions under the HIGH scenario. In the 1.5 °C pathway, gross removals from enhanced weathering and biochar could reach 1.8 and 0.5 GtCO2/yr by 2050, respectively.

a Negative emissions by different CDR methods across modeled scenarios. Positive values represent net positive emissions, reflecting the balance between carbon sinks (photosynthetic processes in forests and savannas, and non-photosynthetic sequestration in soils and water bodies) and carbon sources (emissions from deforestation, fires, and forest degradation). b Regional variations in the share of different CDR methods in 2050 under the most ambitious and optimistic CDR scenario (1.5°C_HIGH). Here, in panel b, our analysis focuses exclusively on the 1.5 °C_HIGH scenario, as it represents the most extensive deployment of CDR technologies among all scenarios considered in this study. For a comprehensive overview of regional negative emissions in 2050 across all scenarios, see Supplementary Fig. 2. BECCS bioenergy with carbon capture and storage. BECCS technologies capture a pre-defined fraction of CO2 that would be emitted into the atmosphere while producing electricity, hydrogen, or refined liquids. Here, the CO2 removed from the atmosphere by bioenergy crops during photosynthesis is not counted to avoid double counting. EW refers to enhanced weathering, and DOCCS refers to direct ocean capture and carbon storage. We deploy three different archetypes for direct air capture (DAC), i.e., electricity-consuming DAC (elec), natural gas-consuming DAC (NG), and low-temperature heatpump DAC. All DAC systems are coupled with carbon capture and storage (DACCS). LUC refers to land use change and it represents the difference between positive and negative emissions from land use. Australia and New Zealand are combined as one region and called Australia_NZ; FTA refers to Free Trade Association; South America is divided into 2 i.e., South America Northern (with suffix as N) and Southern America Southern (with suffix as S). Central America denotes countries in Central America and the Caribbean.

The regional variations in the distribution and contribution of various CDR approaches are mainly driven by resource availability and climate targets. Figure 1b shows the percent share of various CDR approaches in each country/region by 2050 under the most ambitious and optimistic CDR scenario (1.5 C_HIGH). Canada, Russia, Eastern Europe, and Southern/Western Africa will continue to rely heavily on LUC by 2050. The US, Australia_New Zealand, and several parts of South and Central America are expected to lean towards DACCS, while BECCS is anticipated to be the dominant source of negative emissions in several regions across Asia, Europe, and Eastern/Northern Africa. Enhanced weathering will play a key role in South and Southeast Asia, and biochar deployment will make substantial contributions in India, Indonesia, and many parts of Africa due to favorable climatic conditions31.

Electricity generation

The interactions between CDR pathways and the electricity sector will determine how the scale of CO₂ removal impacts the sector’s composition (in terms of electricity production) and the broader decarbonization effort. While most CDR approaches typically increase electricity demand, BECCS offers a way to remove CO₂ while also contributing to energy supply, including electricity. Figure 2a shows the transformation in global electricity supply under varying CDR scenarios for the 1.5 and 2 °C climate pathways. With minimal CDR deployment and no BECCS contribution, the LOW scenario requires the highest level of electricity generation, predominantly from renewables and nuclear energy. Under the 1.5 °C pathway, the LOW scenario sees an almost complete phase-out of unabated fossil fuels by 2050, with renewables and nuclear energy increasing nearly seven-fold and a relatively higher deployment of long-duration energy storage, such as hydrogen, for renewable energy balancing. The MODERATE and HIGH scenarios offer greater flexibility in transforming the electricity mix by allowing continued use of fossil fuels, particularly gas (with and without CCS). In these scenarios, BECCS helps share the emission reduction burden, enabling the electricity system to leverage gas as a transition fuel due to its cost-effectiveness and lower emissions intensity compared to coal and oil40. Our results indicate a 47–56% increase in electricity generation from gas (mainly with CCS) by 2050 relative to 2020 under the MODERATE and HIGH scenarios. Electricity generation from BECCS is projected to account for 2–4% of the total generation in 2050. The integration of BECCS and overall greater CDR deployment could displace generation from nuclear and renewables by 5–15% compared to the LOW scenario.

a Global electricity generation across scenarios. Scenarios with limited CDR availability have substantial increases in zero-carbon electricity generation. By 2050, unabated coal, biomass, and refined liquids electricity generation will be almost completely phased out under 1.5 °C_LOW. CCS: carbon capture and storage. b Regional variation in BECCS-electricity. c Regional share of BECCS in total electricity generation. By 2050, China, the US, and India are projected to dominate global electricity generation from BECCS in absolute terms, while the proportional contribution of BECCS to regional electricity generation is expected to be highest in Mexico, India, and parts of Central and Southern America. Panels b and c exclusively depict the 1.5 °C_HIGH scenario, as it shows the highest demand for BECCS and BECCS-derived electricity. For a comparative analysis of alternative scenarios (see Supplementary Fig. 4b and c).

The potential role of BECCS in meeting future electricity demands while contributing to negative emissions carries important regional implications. Under the most ambitious climate target and optimistic CDR assumptions, China, the US, and India are projected to lead in electricity generation from BECCS by 2050, with outputs ranging from 1.0 to 2.2 EJ/yr (Fig. 2b). By 2050, BECCS is projected to contribute 5–10% of total electricity generation in India, Mexico, and parts of Central and Southern America, indicating a notable dependence on this technology in these regions (Fig. 2c). This highlights BECCS’s potential importance in their decarbonization strategies, driven by factors such as biomass resource availability and existing bioenergy infrastructure. However, large-scale BECCS deployment may pose trade-offs and sustainability challenges surrounding issues such as land-use competition, biodiversity impacts, and water resource management for these regions41,42,43.

Consumption in final energy

Most CDR approaches, such as DACCS, will inevitably interact with the electricity system primarily as consumers of energy, highlighting that while these technologies offer potential solutions for mitigating climate change, they also introduce additional energy demands that must be met. Figure 3a shows how the scale of CDR deployment could influence electricity consumption across end-use sectors under two distinct climate pathways. The 1.5 °C_LOW scenario projects that ~99% of electricity consumption will be dedicated to end-use sectors, with <1% allocated to CDR processes by 2050. In comparison, the 1.5 °C_HIGH scenario indicates that about 5% of electricity will be used for CDR, leading to a reduction in the share of electricity consumption for end-use sectors. While electricity consumption for CDR typically increases with higher deployment under the 1.5 °C pathway, the 2 °C pathway diverges. In the 2 °C_LOW scenario, the share of electricity consumption for CDR is slightly higher than in the MODERATE and HIGH scenarios, likely due to the reduced reliance on energy-intensive technologies like DACCS in favor of other CDR options. In the MODERATE scenario, DACCS has a minimal role in negative emissions, leading to almost no electricity consumption for CDR by 2050. Conversely, in the LOW scenario, DACCS remains the primary technology, making some level of electricity consumption inevitable.

a Percentage share of electricity consumption for end-use sectors versus CDR by 2050. b Share of CDR in electricity consumption by region. The electricity demand for CDR is predominantly attributable to DACCS technology, with the highest demand observed under the 1.5 °C_HIGH scenario. Notably, the regions with the highest DACCS deployment, such as the US and China (Supplementary Fig. 8b), do not necessarily allocate disproportionately large shares of their electricity to CO2 removal. South America and Australia appear more susceptible to higher relative electricity consumption for this purpose.

The large-scale deployment of CDR technologies needed to meet climate targets at national and regional levels will notably impact electricity consumption in various countries and regions, as shown in Fig. 3b. In scenarios relying heavily on energy-intensive CDR approaches (1.5 °C_MODERATE and HIGH), several parts of South America and Australia/New Zealand will see a substantial portion (about 10–20%) of their electricity consumption dedicated to CDR processes. These regions may be well-positioned to utilize their abundant renewable energy resources to support CDR deployment while minimizing additional emissions44,45. Meanwhile, the 2 °C_MODERATE pathway, which assumes minimal overall CDR electricity consumption, sees zero electricity consumption for CDR in several countries across Africa, Europe, and Southern Asia.

Electricity prices

The rapid energy transition is projected to increase electricity prices due to the higher initial costs of integrating renewable energy sources and the anticipated rise in carbon pricing mechanisms, which make fossil fuel-based energy generation more expensive. Figure 4a shows the impact of varying CDR deployment levels on global electricity prices under 1.5 and 2 °C pathways. Achieving the 1.5 °C target with limited CDR necessitates a swifter and more profound decarbonization of the power sector, resulting in higher electricity prices for consumers. The 1.5 °C scenarios generally show higher initial price increases compared to 2 °C scenarios. This trajectory suggests that aggressive climate mitigation strategies required for the 1.5 °C target may incur higher near-term costs. The 1.5 °C_LOW scenario, which anticipates the most abrupt energy transition, shows the largest price increase by 2050, diverging sharply from other scenarios. The 1.5 °C_HIGH scenario starts with a relatively high price increase in 2025 and ends with the largest price decrease in 2050. This is because the anticipated mid-century deployment of CDR technologies at a multi-gigatonne scale (under 1.5 °C_HIGH) could potentially lead to some long-term reductions in electricity prices. The electricity supply sector consistently experiences slightly higher price increases across all scenarios when compared to the demand sectors.

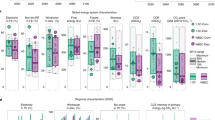

a Global electricity prices by sector. b Percentage change in electricity prices by 2050 relative to 2020 levels across regions and scenarios. The interquartile ranges of our scenario results are represented by the box, covering the 25th to 75th percentiles. The 50th percentile is depicted as the midpoint of the box. The whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values within ±1.5 times the interquartile range. Outliers in some regions are shown as circles.

Regional differences in current electricity mixes, resource potential, technological capacities, and transition requirements manifest as divergent regional price impacts, particularly in scenarios pushing the boundaries of rapid change or limited technology availability. Figure 4b shows the percent change in electricity prices by 2050 relative to 2020 across different regions and scenarios. The 1.5 °C_LOW scenario, sees some of the highest percentage increases in electricity prices across regions. South Africa and India, in particular, experience a 35–45% increase in electricity prices under this scenario, primarily due to the high costs associated with rapidly phasing out their coal-heavy power system. The HIGH scenarios (both under 1.5 and 2 °C) help mitigate price shocks across countries/regions. Canada, the Middle East, and some parts of South America and Africa are expected to witness decreased electricity prices of about 5–20% under these optimistic scenarios.

Capacity additions and investment costs

To drive down the power sector’s emissions towards zero levels by mid-century, any new generation capacity added globally over the coming decades must be dominated by low or zero-carbon technologies. Fossil fuel-based additions, unless fitted with CCS, would create long-lived, emissions-intensive capital stocks incompatible with long-term climate goals33. As shown in Fig. 5a, the 1.5 °C_LOW and 1.5 °C_MODERATE scenarios require continuous capacity expansion throughout the modeled period to meet the inflexibility and higher reserve margins necessary for stringent mitigation efforts. Meanwhile, the 1.5 °C_HIGH scenario follows a pattern similar to the 2 °C CDR scenarios, with peak capacity additions occurring between 2036 and 2040. Decarbonizing electricity supply while meeting projected global demand with LOW CDR requires cumulative capacity additions which are about 5–10% higher than the MODERATE scenario and 7–22% above the HIGH scenario. Capacity additions for unabated coal will cease completely after 2035 under LOW and after 2040 under MODERATE and HIGH in the 1.5 °C pathway. Capacity additions for fossil fuel with CCS are projected to reach 1450–2800 GW by 2050 across all scenarios. Wind and solar capacity additions are expected to increase substantially across all scenarios, accounting for 64–66% of total capacity additions over the modeled period. Cumulative BECCS capacity under the MODERATE and HIGH scenarios could reach 160–380 GW, offsetting some of the need for renewables and nuclear capacity relative to the BECCS-exclusive LOW scenario. Figure 5a also quantifies the capital requirements for deploying new capacity under the modeled scenarios. We find that the full deployment of CDR options could reduce cumulative investment costs by up to 10% and 18% compared to the MODERATE and LOW scenarios, respectively. Investment in solar and wind capacity is projected to reach a cumulative of US$ 17–25 trillion by 2050, representing 45–50% of total investment costs. Nuclear and BECCS, being more expensive, will have disproportionately higher shares of investment costs relative to their shares in capacity additions. The HIGH scenario may require up to US$ 1.3 trillion more investments in BECCS compared to the MODERATE scenario.

a Global capacity additions and investment costs across scenarios. The bars depict cumulative capacity additions and costs aggregated over five-year model intervals. Stringent requirements under 1.5 °C_LOW and MODERATE scenarios necessitate increasing global capacity additions over the entire 30-year period, whereas the remaining scenarios reach peak additions in the middle of the modeled period. b Regional cumulative capacity additions and investment costs over the 30-year period under the most ambitious climate target and optimistic CDR assumptions (1.5 °C_HIGH). CCS carbon capture and storage. CCS here includes both fossil fuel-based capacity that is equipped with CCS as well as bioenergy CCS.

The regional variations in cumulative capacity additions and related costs under 1.5 °C_HIGH are shown in Fig. 5b. China’s cumulative capacity additions for renewables and nuclear will account for ~23% of the world’s total. This translates into an investment cost of about US$ 7.5 trillion, roughly equivalent to 42% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 202246. The US, India, and Europe also see substantial investments in renewables and nuclear power, cumulating to US$ 3–3.5 trillion. China takes the lead again in investments in bioenergy and CCS technologies, followed by India, the US, and the Middle East. Driven primarily by its biomass resource availability47,48, India’s projected capacity investments notably favor BECCS, potentially accounting for about 25% of its total investment costs. Meanwhile, the Middle East’s sustained reliance on gas necessitates substantial investments in fossil CCS technologies, projected to account for about 40% of the region’s total capacity investments.

Stranded capacity and costs

Climate policies aimed at deep decarbonization pose a major risk of rendering high-emission power sector assets, such as fossil fuel-based plants, economically unprofitable or obsolete before the end of their natural operational lifetimes49,50. Figure 6a shows that between 1140 and 2200 GW of existing power plants could become stranded from 2016 to 2050. The HIGH scenario reduces stranded asset capacity by up to 15% and 25% compared to the MODERATE and LOW scenarios, respectively. Conventional coal-fired power plants account for ~55–70% of the total stranded capacity across modeled scenarios. In absolute terms, the LOW scenario experiences the highest stranding of coal assets, with about 40–130 GW more capacity stranded compared to the MODERATE and HIGH scenarios. Interestingly, the HIGH scenario projects a larger share of coal in its total stranded capacity, as the share of gas is reduced, allowing gas to continue being used as a transition fuel. In contrast, the LOW and MODERATE scenarios, especially under 1.5 °C, require the earlier stranding of all emission-intensive assets, including gas-fired plants. The MODERATE and HIGH scenarios foresee earlier stranding of conventional bioenergy assets due to the potential for retrofitting these plants with CCS technology. Transitioning conventional bioenergy plants to BECCS facilities aligns these assets with stringent climate mitigation goals, incentivizing the early stranding of these plants to facilitate their conversion. The premature retirement of conventional power plants from 2016 to 2050 cumulates to stranding costs of about US$3.6 to 6.8 trillion across modeled scenarios (Fig. 6a). The HIGH scenario could offset stranding costs by 5–10% and 17–20% relative to the MODERATE and LOW scenarios, respectively. Notably, the share of stranding costs for coal power plants is disproportionately larger relative to their share of stranded capacity. This could be attributed to the relatively higher capital expenditures associated with coal power plants and their slower depreciation rates, which stem from their longer assumed operational lifespans51. This observation highlights substantial economic challenges associated with the potential phase-out of conventional coal power plants compared to gas and oil in the context of deep decarbonization.

a Global stranded capacity and stranding costs across scenarios. The bars depict cumulative stranded capacity and costs aggregated over 5-year model intervals. The HIGH CDR pathway could save up to US$ 1.3 trillion in stranding costs over the next three decades compared to the LOW CDR scenario. b Regional cumulative stranded assets and stranding costs over the 30-year period under the most ambitious climate target and optimistic CDR assumptions (1.5 °C_HIGH). Countries and regions with a higher dependence on coal will incur disproportionately higher stranding costs compared to those that rely more on gas and oil.

As countries and regions adopt increasingly ambitious climate policies, such as carbon pricing mechanisms, emissions performance standards, or outright phase-out plans, the economic and regulatory environment for emission-intensive power generation could become highly unfavorable. Figure 6b present the regional variations in potential stranded assets and associated costs by 2050 under the 1.5 °C_HIGH scenario. China’s projected premature retirements reach a cumulative total of 480 GW by 2050, resulting in stranding costs of about US$ 1.9 trillion. Existing coal assets account for 98% of the total stranded capacity, equivalent to ~40% of the country’s current coal capacity52. The US and India are ranked second and third, respectively, in terms of the most at-risk countries for stranded assets, with nearly identical cumulative stranded capacities. However, India’s stranding costs are approximately 35% higher than those of the US due to the differing composition of their stranded assets. In India, about 95% of the stranded capacity is coal-based, while in the US, coal accounts for only 55%. Due to coal’s relatively higher stranding costs compared to gas and oil, India will incur much greater stranding costs, despite the US having a slightly higher overall stranded capacity. Other countries, such as South Africa and Indonesia, would also experience high potential stranding costs due to their coal-heavy power sectors. In contrast, Russia and the Middle East would see disproportionately lower stranding costs, primarily from gas and oil assets.

Committed emissions

The continued operation of fossil fuel-based power plants over their typical lifetimes would result in a substantial amount of committed emissions53, posing challenges to both near- and long-term climate goals. By accounting for the expected lifetimes and utilization rates of existing fossil fuel-based power plants, we estimate their anticipated committed emissions under normal operations, comparing these projections against modeled emissions under varying CDR deployment scenarios consistent with the 1.5 and 2 °C climate pathways. Figure 7 shows that the continued operation of existing power plants over their full remaining lifetimes would result in approximately 495 GtCO2 in the coming decades, with about 75% of these emissions attributed to coal assets. For a 50% likelihood of limiting global warming to 2 °C54,55, these committed emissions would consume approximately 43% of the remaining carbon budget (2020 onwards) and nearly exhaust the budget for 1.5 °C. Premature retirement or retrofitting of existing infrastructure before the end of its expected lifetime could help mitigate committed emissions and align the power sector with decarbonization targets. Our results show that the 1.5 and 2 °C pathways require up to 55% and 40% reductions in committed emissions, respectively, compared to the REF scenario. Large-scale CDR deployment by mid-century could offset committed emissions from long-lived assets, reducing the need for aggressive premature retirements. As a result, scenarios with higher CDR expectations allow for longer operational lifetimes of emissions-intensive assets, leading to higher committed emissions compared to limited CDR deployment scenarios. Relative to scenarios with greater CDR deployment, the LOW scenario requires committed emissions reductions of 8–12% under 2 °C and 5–15% under 1.5 °C pathways. Coal asset retirement will drive 35–55% of emissions reductions across scenarios due to coal’s high emissions intensity and substantial share in global power generation.

Global committed emissions from existing power plants in a reference scenario (REF) compared to the modeled scenarios. Under the 1.5 °C pathway, committed emissions are projected to decrease by 221, 250, and 263 GtCO2 in the HIGH, MODERATE, and LOW scenarios, respectively. Meanwhile, the 2 °C pathway sees reductions of 154, 169, and 195 GtCO2 in the same CDR scenarios. Regional variations in committed emissions. Other Asia represents all Asian countries including Australia and New Zealand and excluding China and India. LAC represents Latin America and the Caribbean, i.e., South America, Central America, and countries in the Caribbean. The horizontal lines represent the committed emission of modelled scenarios relative to the REFERENCE scenario.

Figure 7 also compares the baseline committed emissions (REF) for various countries/regions to the modeled scenarios. China leads in committed emissions from operational power plants at 216 GtCO2, accounting for approximately 40% of the global total. Given that about 97% of China’s commitments originate from coal, achieving climate goals will require reductions of approximately 60–100 GtCO2 through extensive stranding of coal assets. The US, Europe, and India collectively account for one-third of global committed emissions. Despite India having the lowest committed emissions among these three regions, it requires the largest reductions across modeled scenarios, particularly under the most ambitious 1.5 °C_LOW scenario. India’s higher proportion of emissions from coal generators, along with its limited potential for CDR under the LOW scenario (no BECCS), requires a relatively more aggressive approach to asset stranding. The Middle East, Latin America, and Caribbean (LAC) regions, dominated by natural gas infrastructure, jointly account for about 25% of global gas-based committed emissions. The Middle East exhibits the lowest required emissions reductions among all regions, primarily due to its limited dependence on coal-fired power generation.

CO2 prices

The marginal abatement cost of carbon, or carbon price, represents the cost of reducing the final unit of emissions needed to meet a climate target2. Figure 8 shows the marginal abatement cost of varying CDR levels consistent with limiting warming to below 1.5 and 2 °C by 2100. By 2050, the carbon price under the 1.5 °C_LOW scenario will be almost thrice the amount under 1.5 °C_HIGH. Scenarios with constrained CDR availability necessitate accelerated deployment of alternative mitigation strategies, particularly rapid clean energy transitions, to achieve emissions targets. While this approach reduces long-term CDR requirements, it faces critical near-term economic barriers due to the higher relative costs of low-carbon technologies compared to conventional carbon-intensive alternatives. Conversely, pathways incorporating extensive CDR deployment offer greater temporal flexibility in decarbonization efforts, as future carbon removal can offset delayed emission reductions. This fundamental trade-off between immediate decarbonization and future CDR utilization largely explains the elevated marginal costs associated with scenarios severely limiting CDR deployment.

The pathways targeting warming below 2 °C have relatively lower costs owing to less stringent emission reduction requirements. Additionally, scenarios that assume low CDR availability exhibit higher marginal abatement costs of carbon compared to the HIGH and MODERATE CDR scenarios, particularly under the 1.5 °C pathway.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive global analysis of how varying levels of CDR deployment could impact the transformation of the electric power sector under 1.5 and 2 °C climate pathways. Our findings indicate that most CDR approaches typically interact with the electricity system as energy consumers, potentially accounting for 1–4% of global electricity demand by 2050. In contrast, BECCS offers a way to remove CO2 while contributing ~2–4% to the electricity supply. Limiting novel CDR deployment to about 1 GtCO2 by 2050, without BECCS, necessitates up to $9 trillion more investment in renewables and nuclear compared to a pathway with up to 10 GtCO2 of CDR from a diverse portfolio, including BECCS. The aggressive scaling of renewables and nuclear under the LOW CDR scenario results in higher electricity prices for consumers, especially under the 1.5 °C climate pathway.

More importantly, our findings indicate that large-scale CDR deployment can alleviate some economic challenges of rapid decarbonization by reducing stranded assets in the power sector. The HIGH CDR scenario could decrease stranded asset capacity by up to 25% compared to the LOW scenario, saving approximately half a trillion US dollars in stranding costs. However, this benefit comes with a trade-off: greater CDR availability extends the operational lifetimes of emissions-intensive assets, increasing projected committed emissions from the power sector. The high CDR pathway could result in about 15% higher committed emissions under the 1.5 °C target and 12% higher under the 2 °C target, compared to the constrained CDR scenario. This raises important considerations for policymakers regarding the balance between relying on CDR deployment as an emission-offsetting strategy and prioritizing more aggressive premature retirements of emissions-intensive assets. While CDR technologies offer a potential solution for achieving climate targets more gradually, their feasibility at the necessary scale remains uncertain due to substantial technical, socio-economic, environmental, and political barriers28,56,57,58.

Regionally, CDR deployment levels shape electricity systems in markedly different ways. In optimistic CDR scenarios (HIGH CDR), regions like Mexico, India, and some parts of Central and South America will see substantial shares of their electricity supply derived from BECCS. Conversely, regions such as Brazil, Argentina, and Australia/New Zealand will need to utilize their renewable energy resources to support a considerable portion of their electricity consumption dedicated to CDR processes. Despite optimistic CDR deployment, the scale and speed of power sector transformation required under both climate targets remain substantial across all regions. Major economies like China, the U.S., and India face multi-trillion-dollar investment requirements, primarily in expanding renewable and nuclear capacity. These countries are most at risk for stranded assets, translating into stranding costs of up to US$0.5–2 trillion by mid-century, even under the most optimistic CDR assumptions. Generally, regions with higher coal dependence face much higher stranding costs compared to regions relying more on gas and oil, particularly under the HIGH scenario, which further delays gas stranding.

Future research can enhance our understanding of the challenges and opportunities linked to the rapid decarbonization of the power sector required under the Paris Agreement and the integration of novel CDR technologies. Key research directions could include: (1) Advancing integrated assessment models to capture the complex socio-economic impacts of power sector decarbonization, such as job displacement, economic development, and inequities among affected populations. (2) Exploring policy frameworks, support mechanisms, and international cooperation strategies to facilitate a just and equitable transition, particularly for the Global South. (3) Quantifying the implications of varying degrees of government commitment and willingness to asset stranding, especially considering that countries in the Global South, which have recently acquired carbon-intensive assets, may be less willing to strand their assets than those in the Global North.

Methods

The primary objective of this study is to examine the impact of CDR reliance on the transformation of the electric power sector, with a particular focus on stranded assets and committed emissions linked to the technologies within this sector. To achieve this, we employed a modified version of the global change assessment model (GCAM)31. This enhanced model incorporates five novel CDR approaches, and it allows users to set separate and explicit targets for the amount of CO2 to be removed at any given time21.

Model description

GCAM is one of the leading integrated assessment models (IAMs) in climate change research. GCAM has been extensively used to investigate the interconnections between the global economy, energy systems, land use, and the environment59. It is a market equilibrium model with a global scope, operating from 1990 to 2100 in 5-year time steps. GCAM can analyze how changes in factors such as population, income, or technology costs may impact crop production, energy demand, land use changes, and water withdrawals60. It can also explore how variations in one region’s energy demand influence energy, water, and land use in other regions. The core of GCAM represents the entire world but is constructed with varying levels of resolution for different systems. In the current release version, the energy-economy system is divided into 32 global regions, land use is subdivided into over 300 subregions, and water resources are tracked across 233 basins worldwide60. GCAM is calibrated to 2015 historical data. Over the past two decades, GCAM has been utilized in virtually every major climate, energy, and economics assessment, highlighting its significance in climate change mitigation research60.

For a detailed model description, including modeling equations and parameters, refer to Supplementary Notes 1 and;2 and Supplementary Methods 1–7.

Scenario formulation

In this study, we model three different levels of future CDR reliance under two climate targets. CDR technologies are broadly categorized into land-based (conventional) CDR, such as afforestation/reforestation (AR) and novel (technological) CDR, which includes BECCS, DACCS, DOCCS, biochar, and enhanced weathering (EW). Existing studies indicate that current global CDR totals approximately 2 GtCO2/yr, with 99.9% derived from conventional CDR61. However, conventional CDR approaches face challenges related to additionality, permanence, and reversibility28. Consequently, novel CDR methods are expected to play a more substantial role in offsetting residual emissions as they become more cost-effective and technologically mature39. The success of future negative emissions from novel CDR technologies remains uncertain from a technical standpoint28,58, and there are environmental and sustainability concerns associated with these methods21,62. Against this backdrop, we model three possible pathways for future CDR efforts.

-

1.

HIGH CDR Scenario: In this scenario, we assume that near-term emissions reductions will be insufficient, necessitating large-scale CDR by the mid-term to counterbalance residual emissions, achieve net zero, and eventually sustain net negative emissions to return temperatures to safe levels after a temporary overshoot. This scenario deploys five novel CDR technologies without any annual removal limits.

-

2.

MODERATE CDR Scenario: Here, we assume that challenges to the deployment of several novel CDR approaches with lower Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) and mitigation potential will persist. The focus will be on BECCS and DACCS, the two most researched novel CDR methods, which have TRLs of about 6 and mitigation potentials of up to 11 and 40 GtCO2/yr, respectively2. To limit negative impacts, their combined deployment is capped at 5 GtCO2/yr of negative emissions by 2050.

-

3.

LOW CDR Scenario: This scenario assumes that novel CDR technologies will not meet expectations, and the focus will shift to decarbonization. Due to sustainability issues such as land competition associated with BECCS62, the emphasis will be on DACCS, which is expected to provide not more than 1 GtCO2/yr of negative emissions by 2050. This will mainly offset residual emissions from recalcitrant sectors such as aviation, shipping, and agriculture. In all three scenarios, negative emissions from conventional CDR are deployed endogenously.

All three CDR scenarios are modeled under two climate pathways: 1.5 °C (high overshoot) and 2 °C. These pathways align with scenarios assessed by the IPCC in its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). According to these scenarios, the 5–95th percentile range for the net zero years for 1.5 °C (high overshoot) is between 2045 and 2070 (with a 50th percentile of 2055–2060), while for 2 °C, it is from 2055 onwards (with a 50th percentile of 2070–2075). Additionally, for 1.5 °C (high overshoot), the 5th–95th percentile for total net CO2 emissions from 2020 to the year of net zero is 530–930 GtCO2, and for 2 °C, it is 640–1160 GtCO22. Consistent with these existing pathways, we model a 1.5 °C target where CO2 emissions peak before 2025 and decline linearly to net zero before 2055, with a total carbon budget of 780 GtCO2. For the below 2 °C target, CO2 emissions also peak before 2025 but decline linearly to net zero before 2070, with a total carbon budget of 1095 GtCO2.

One other important aspect of modeling CDR targets is that, in some of the previous studies where different CDR scenarios were limited, the authors used fewer CDR options as against several CDR options to represent LOW vs. HIGH CDR scenarios without actually specifying exact targets63. In addition, some studies also used limits on CCS and biomass as a way of reducing DACCS and BECCS in LOW CDR scenarios31,64,65,66. This approach is not ideal since limiting CCS affects other technologies that are not BECCS/DACCS, such as fossil fuel CCS and also limiting biomass affects other services such as biofuel in transport. In our approach, the way we set our caps ensures that we achieve a specific CDR target for each scenario without affecting other services directly, such as CCS and biomass, as some of the previous studies did. This approach aligns with our research objective of analyzing how CDR technologies and their availability impact the power sector, and, conversely, how the power sector influences the CDR industry.

It is important to note that we do not directly constrain emissions from land use change; instead, we apply the same pricing to these emissions as we do to emissions from fossil fuels and industry. This method enhances the role of conventional CDR in offsetting residual emissions, particularly in scenarios where novel CDR methods do not achieve sufficient negative emissions. It also aids in reducing deforestation rates by enabling a quick shift from net positive land use change (LUC) emissions to net negative LUC emissions by as early as 2025. Furthermore, in all our modeled pathways, we do not directly constrain non-CO2 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, such as methane, nitrous oxides, and fluorinated gases. Instead, the model reduces these emissions by applying marginal abatement cost (MAC) curves. The emission intensities of these non-CO2 gases decrease as GHG prices rise, with these prices linked to carbon prices through global warming potential (GWP) values using a 100-year time horizon (GWP-100)39,67.

Estimating stranded assets in the electric power sector

We follow Ou et al.23 to evaluate yearly capacity additions, premature retirements, and related capital expenditures in the electric power sector. In this process, GCAM tracks the capital stock, technological specifications, and vintage of electrical power plants throughout the entire lifespan of each technology. Two different mechanisms can bring about the retirement of electrical power plants. That is, power plants retiring naturally or profit-induced retirement. When power plants reach the end of their designed operational lifespan they retire naturally. On the other hand, a power plant can be pre-maturely retired when its continued operation becomes financially unviable, resulting in stranded assets and this falls under profit-induced retirement (as defined in Eq. (1)).

where \({G}_{{{T}},{{V}},{{r}}}(t)\) denotes electricity generation for technology \({{T}}\) and vintage \({{V}}\) in region \({{r}}\) during modeling period \(t\). \({f}_{{{T}},{{V}},{{r}}}^{{N}}(t)\) and \({f}_{{{T}},{{V}},{{r}}}^{{P}}(t)\) are the fraction of natural and profit-induced retirement in modeling period \(t\).

The Plutus package in R68 was employed to analyze capacity and capital stock turnover in the power sector, following a three-stage process23. Under each scenario, the package extracts technology- and vintage-specific electricity generation from each country’s output. Next, the natural retirement fraction \({f}_{{{T}},{{V}},{{r}}}^{{{N}}}(t)\) for each new fleet’s vintage is estimated. Finally, Plutus compares the scenario electricity generation output with the projected natural retirement trajectory from Step 2 to determine premature retirement and stranded assets. Stranded assets are calculated by multiplying premature retirement by the corresponding technology’s capital cost.

Estimating committed emissions

Our calculation of current committed emissions is based on currently operating power plants. In this context, committed emissions are those emissions that will continue to occur over the remaining operational life of a fossil fuel-based power generator53. Our calculation for committed emissions of existing coal, oil, and gas plants follows Eq. (2)49, where F represents CO2 emissions measured in tCO2 yr−1 and it is expressed as the product of plant capacity C (in GW) and utilization rate E/C (in %) and carbon intensity of electricity generated F/E (in g kWh−1). E is the electricity output (GWh yr−1). Constant utilization rates and emission factors are used in our calculations as shown in Table 2.

The various capacities of existing coal, oil, and gas power plants are obtained from Global Energy Monitor (https://globalenergymonitor.org/).

Data availability

Additional input files for power sector—CDR analysis are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14898105.

Code availability

GCAM is an open-source community model. The version of GCAM used in this study with all additional input files necessary for power sector-CDR analysis is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14898105.

References

IPCC. Climate change 2014: synthesis report. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds, Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R. K. & Meyer, L. A.) (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2014).

IPCC. Climate change 2022: mitigation of climate change. In Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds P. R. Shukla, P. R. et al.). (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 4811–4900 (2022).

Lamboll, R. D. et al. Assessing the size and uncertainty of remaining carbon budgets. Nat. Clim. Chang. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01848-5 (2023).

Forster, P. M. et al. Indicators of Global Climate Change 2022: annual update of large-scale indicators of the state of the climate system and human influence. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 2295–2327 (2023).

IEA. Global Energy-related CO2 Emissions by Sector. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/global-energy-related-co2-emissions-by-sector (IEA, 2020).

Ampah, J. D. et al. The overarching role of electric vehicles, power‑to‑hydrogen, and pumped hydro storage technologies in maximizing renewable energy integration and power generation in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Energy Storage 67, 107602 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Deployment of hydrogen in hard-to-abate transport sectors under limited carbon dioxide removal (CDR): implications on global energy-land-water system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 184, 113578 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. A perspective on the overarching role of hydrogen, ammonia, and methanol carbon-neutral fuels towards net zero emission in the next three decades. Energies 16, 280 (2022).

Heptonstall, P. J. & Gross, R. J. K. A systematic review of the costs and impacts of integrating variable renewables into power grids. Nat. Energy 6, 72–83 (2021).

Alexopoulos, D., Vokas, G. A. & Psomopoulos, C. Pumped hydro energy storage schemes to support high RES penetration in the electric power system of Greece. in 020051 (Athens, Greece, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0033445.

Arda, I., Eric, D. van H. & Donald, H. Critical Materials and Sustainability Transition (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2023).

Viebahn, P. et al. Assessing the need for critical minerals to shift the German energy system towards a high proportion of renewables. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 49, 655–671 (2015).

Auger, T., Trüby, J., Balcombe, P. & Staffell, I. The future of coal investment, trade, and stranded assets. Joule 5, 1462–1484 (2021).

Carley, S. & Konisky, D. M. The justice and equity implications of the clean energy transition. Nat. Energy 5, 569–577 (2020).

Binsted, M. et al. Stranded asset implications of the Paris Agreement in Latin America and the Caribbean. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 044026 (2020).

UNEP. Emissions Gap Report 2023 http://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2023 (UNEP, 2023).

Fuhrman, J. et al. The role of negative emissions in meeting China’s 2060 carbon neutrality goal. Oxf. Open Clim. Change 1, kgab004 (2021).

Fuhrman, J. et al. Food–energy–water implications of negative emissions technologies in a +1.5 °C future. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 920–927 (2020).

Realmonte, G. et al. An inter-model assessment of the role of direct air capture in deep mitigation pathways. Nat. Commun. 10, 3277 (2019).

Ampah, J. D. et al. Prioritizing non-carbon dioxide removal mitigation strategies could reduce the negative impacts associated with large-scale reliance on negative emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c06866 (2024).

Iyer, G. et al. Measuring progress from nationally determined contributions to mid-century strategies. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 871–874 (2017).

Ou, Y. et al. State-by-state energy–water–land–health impacts of the US net-zero emissions goal. Energy Clim. Change 4, 100117 (2023).

Lu, Y., Cohen, F., Smith, S. M. & Pfeiffer, A. Plant conversions and abatement technologies cannot prevent stranding of power plant assets in 2 °C scenarios. Nat. Commun. 13, 806 (2022).

von Dulong, A. Concentration of asset owners exposed to power sector stranded assets may trigger climate policy resistance. Nat. Commun. 14, 6442 (2023).

Afrane, S. et al. Deployment of carbon removal technologies could reduce the rapid and potentially disruptive pace of decarbonization in South Africa’s climate ambitions. J. Clean. Prod. 464, 142753 (2024).

Goldberg, D. S., Nawaz, S., Lavin, J. & Slagle, A. L. Upscaling DAC hubs with wind energy and CO2 mineral storage: considerations for large-scale carbon removal from the atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c03492 (2023).

Anderson, K. et al. Controversies of carbon dioxide removal. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1–7 https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-023-00493-y (2023).

Adun, H., Ampah, J. D., Bamisile, O. & Hu, Y. The synergistic role of carbon dioxide removal and emission reductions in achieving the Paris Agreement goal. Sustain. Prod. Consum. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2024.01.004 (2024).

Pradhan, S. et al. Effects of direct air capture technology availability on stranded assets and committed emissions in the power sector. Front. Clim. 3, 660787 (2021).

Fuhrman, J. et al. Diverse carbon dioxide removal approaches could reduce impacts on the energy–water–land system. Nat. Clim. Chang. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01604-9 (2023).

Ampah, J. D. et al. Does China’s pathway to carbon neutrality require the integration of land-based biological negative emission solutions with geochemical and chemical alternatives? Sustain. Prod. Consum. 45, 27–41 (2024).

Pfeiffer, A., Hepburn, C., Vogt-Schilb, A. & Caldecott, B. Committed emissions from existing and planned power plants and asset stranding required to meet the Paris Agreement. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 054019 (2018).

Iyer, G. et al. Ratcheting of climate pledges needed to limit peak global warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 1129–1135 (2022).

Fuhrman, J. et al. The role of direct air capture and negative emissions technologies in the shared socioeconomic pathways towards +1.5 °C and +2 °C futures. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 114012 (2021).

Morrow, D. R., Apeaning, R. & Guard, G. GCAM-CDR v1.0: enhancing the representation of carbon dioxide removal technologies and policies in an integrated assessment model. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 1105–1118 (2023).

McLaren, D. P., Tyfield, D. P., Willis, R., Szerszynski, B. & Markusson, N. O. Beyond “net-zero”: a case for separate targets for emissions reduction and negative emissions. Front. Clim. 1, 4 (2019).

Höglund, R., Mitchell-Larson, E. & Delerce, S. How to Scale Carbon Removal without Undermining Emission Cuts https://carbongap.org/how-to-scale-carbon-removal-without-undermining-emission-cuts/ (2023).

Zhao, X., Mignone, B. K., Wise, M. A. & McJeon, H. C. Trade-offs in land-based carbon removal measures under 1.5 °C and 2 °C futures. Nat. Commun. 15, 2297 (2024).

McJeon, H. et al. Limited impact on decadal-scale climate change from increased use of natural gas. Nature 514, 482–485 (2014).

Heck, V., Gerten, D., Lucht, W. & Popp, A. Biomass-based negative emissions difficult to reconcile with planetary boundaries. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 151–155 (2018).

Creutzig, F. Economic and ecological views on climate change mitigation with bioenergy and negative emissions. GCB Bioenergy 8, 4–10 (2016).

Afrane, S. et al. Role of negative emission technologies in South Africa’s pathway to net zero emissions by 2050. Energy Sustain. Dev. 79, 101401 (2024).

Escamilla-García, P. E., Fernández-Rodríguez, E., Jiménez-Castañeda, M. E., Jiménez-González, C. O. & Morales-Castro, J. A. A review of the progress and potential of energy generation from renewable sources in Latin America. Lat. Am. Res. Rev. 58, 383–402 (2023).

Neill, A. The Viability of Small Scale Renewable Power Generation in Rural Australia (The University of Queensland, 2016). https://doi.org/10.14264/413762.

WBG. GDP (Current US$)—China. World Bank Open Data https://data.worldbank.org (2022).

Joshi, P., Sharma, N. & Manab Sarma, P. Assessment of biomass potential and current status of bio-fuels and bioenergy production in India. Curr. Biochem. Eng. 3, 4–15 (2016).

Hiloidhari, M., Das, D. & Baruah, D. C. Bioenergy potential from crop residue biomass in India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 32, 504–512 (2014).

González-Mahecha, E., Lecuyer, O., Hallack, M., Bazilian, M. & Vogt-Schilb, A. Committed emissions and the risk of stranded assets from power plants in Latin America and the Caribbean. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 124096 (2019).

Stranded Assets and the Environment: Risk, Resilience and Opportunity (Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, London; New York, 2018).

Farnoosh, A. Power generation from coal, oil, gas, and biofuels. In The Palgrave Handbook of International Energy Economics (eds. Hafner, M. & Luciani, G.) 111–130 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022).

Statista. Global Coal Power Capacity By Major Country 2023 https://www.statista.com/statistics/530569/installed-capacity-of-coal-power-plants-in-selected-countries/ (Statista, 2024).

Davis, S. J., Caldeira, K. & Matthews, H. D. Future CO2 emissions and climate change from existing energy infrastructure. Science 329, 1330–1333 (2010).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2023. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 5301–5369 (2023).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. in Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Zakkour, P., Kemper, J. & Dixon, T. Incentivising and accounting for negative emission technologies. Energy Procedia 63, 6824–6833 (2014).

Honegger, M. & Reiner, D. The political economy of negative emissions technologies: consequences for international policy design. Clim. Policy 18, 306–321 (2018).

Fuss, S. et al. Negative emissions—Part 2: costs, potentials and side effects. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063002 (2018).

Bond-Lamberty, B. et al. JGCRI/Gcam-Core: GCAM 6.0 https://zenodo.org/record/6619287 (2022) https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.6619287.

Bond-Lamberty, B. et al. JGCRI/gcam-core: GCAM 5.4 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5093192 (2021).

Smith, S. M. et al. The State of Carbon Dioxide Removal, 1st edn (2023).

Deprez, A. et al. Sustainability limits needed for CO2 removal. Science 383, 484–486 (2024).

Kim, H. et al. Provincial-scale assessment of direct air capture to meet China’s climate neutrality goal under limited bioenergy supply. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 114021 (2024).

Calvin, K. et al. Trade-offs of different land and bioenergy policies on the path to achieving climate targets. Clim. Change 123, 691–704 (2014).

Grant, N., Gambhir, A., Mittal, S., Greig, C. & Köberle, A. C. Enhancing the realism of decarbonisation scenarios with practicable regional constraints on CO2 storage capacity. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 120, 103766 (2022).

Kim, H. et al. Integrated assessment modeling of Korea’s 2050 carbon neutrality technology pathways. Energy Clim. Change 3, 100075 (2022).

Fuhrman, J. et al. Ambitious efforts on residual emissions can reduce CO2 removal and lower peak temperatures in a net-zero future. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 064012 (2024).

Zhao, M. et al. plutus: an R package to calculate electricity investments and stranded assets from the Global Change Analysis Model (GCAM). JOSS 6, 3212 (2021).

Davis, S. J. & Socolow, R. H. Commitment accounting of CO2 emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 084018 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFE0113100), for supporting the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M., P.Y., J.C., S.A., and H.Z. conceived and designed the research. S.A. and J.D.A. designed and developed the scenarios. S.A. led the modeling and wrote the first draft of the paper. S.A., J.D.A., and H.A. co-led parts of the assessment and contributed to the analysis of data. G.M., J.C., and P.Y. supervised the research. All authors provided feedback throughout the work and contributed to the writing of the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Jonghwan Kwon, Habiba Ahut Daggash, and Nadejda Victor reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Heike Langenberg, Aliénor Lavergne. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Afrane, S., Ampah, J.D., Adun, H. et al. Targeted carbon dioxide removal measures are essential for the cost and energy transformation of the electricity sector by 2050. Commun Earth Environ 6, 227 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02190-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02190-8

This article is cited by

-

Decarbonization and axiomatized myths

Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy (2025)