Abstract

Agriculture is a major contributor to nutrient pollution that drives eutrophication in aquatic ecosystems. This study integrates hydrological modeling with farmer behavioral analysis to assess the effectiveness of two agricultural conservation practices—cover crops and reduced nitrogen fertilizer application—in reducing nitrate loss from fields in the Tar-Pamlico River Basin of North Carolina. Survey responses from 279 farmers revealed widespread reluctance to adopt conservation practices, particularly strict fertilizer reductions. A hydrological model showed that applying each practice to 25 percent of agricultural land could substantially reduce nitrate export, with cover crops showing greater effectiveness than reduced fertilizer use. However, an integrated socio-hydrological model, which incorporated behavioral responses from farmers, predicted much smaller reductions in nitrate loss due to limited voluntary adoption. Specifically, nitrate reductions were overestimated by a factor of 8 for cover crops and by a factor of 25 for reduced fertilizer application when behavioral responses were excluded. This result highlights a critical limitation of traditional modeling approaches and underscores the importance of integrating human decision-making into environmental policy analysis. By linking policy incentives with both biophysical and social responses, this study offers a more realistic framework for designing cost-effective and impactful agricultural conservation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Eutrophication has emerged as a global issue over the last century, primarily due to agriculture, a common major non-point source of nutrient pollution worldwide. Excessive fertilizer usage has exacerbated this problem, contributing significantly to nutrient runoff into water bodies1. High nutrient loading can lead to harmful algal blooms2, hypoxia3, and loss of biodiversity4, undermining the health of aquatic ecosystems and affecting water quality for recreation and wildlife5,6,7.

Implementing agricultural Best Management Practices (BMPs), such as the strategic use of cover crops and the reduction of chemical nitrogen (N) fertilization rates, offers a targeted approach to mitigating the threat of excess nutrients in watersheds8. Cover crops, planted during times when the soil might otherwise be bare, play a crucial role in improving soil structure, enhancing water infiltration, and increasing soil organic matter content9. This leads to reduced runoff and erosion, thereby limiting the flow of nutrients into adjacent water bodies. Moreover, some cover crop species capture residual nitrogen from previous crop fertilization, effectively reducing nitrate leaching into groundwater and surface waters10. Reducing the application rate of nitrogen fertilizers directly addresses a source of nutrient pollution11. Together, these BMPs have the potential to contribute significantly to reducing excessive nutrients in agriculturally dominated watersheds, thus improving water quality and supporting the health of aquatic ecosystems as we adapt to the impacts of climate change9,11,12.

Hydrological modeling using tools like the Soil and Water Assessment Tool Plus (SWAT + ) allows researchers to evaluate the nutrient loading impacts of agricultural BMPs across various scales, aiding policymakers in mitigating nutrient pollution and potentially improving ecosystem health1,13,14,15. However, traditional hydrological modeling studies often lack nuanced, data-driven methods for incorporating individual decision-making into policy analysis. Put simply, hydrological model simulations are sufficient for identifying the watershed impacts of specified land use changes but are ill-equipped to determine which specific land use changes will result from a given policy. This is especially relevant for agricultural BMPs, where both historical and current policies tend to encourage voluntary adoption rather than mandating specific practices. Integrating people’s perspectives—through behavioral modeling—into hydrological modeling is essential for aligning model outputs with real-world conditions. Such integration enhances the accuracy of simulations, effectively bridging the gap between biogeochemical process modeling and socio-economic dynamics16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

In response to the outlined challenges, this study will undertake a multifaceted approach that combines nitrate modeling with an evaluation of the effectiveness of cover crops and reduced nitrogen application rates in mitigating field-edge nitrate export. Recognizing the importance of socio-economic factors in the adoption and success of BMPs, this research will also integrate the human dimension through a farmer behavioral model. Finally, by comparing the outcomes of traditional hydrological modeling with those informed by a farmer behavioral model, this study aims to highlight the added value of embedding social dynamics into hydrological models. We contribute to an increasing literature that highlights the bias of performing policy analyses that fail to account for changes in human action23,24, but this work is novel in several ways. It is the first of its kind to integrate farmer behavioral modeling to a SWAT+ hydrological model, but more broadly it also differs in the depth of integration between hydrological and behavioral models. Similar integrative approaches should enhance the accuracy of model predictions and provide actionable insights for policymakers, ultimately contributing to more effective and sustainable watershed management strategies.

The objectives of this study are to: (1) simulate BMPs, specifically cover crops and reduced fertilizer application, using the SWAT+ model for the Tar-Pamlico watershed in coastal North Carolina, and (2) compare the impacts of different policies on the reduction of nitrate leaving agricultural fields, which is a large driver of ecosystem health, using the SWAT+ hydrological model and a socio-hydrological model that combines SWAT+ with a farmer behavioral model. We compared the outcomes of a baseline model with two different policies related to cover crops and reduced fertilizer application using both hydrological and socio-hydrological modeling approaches (Table 1).

Results and discussion

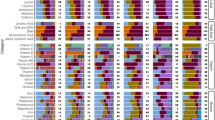

To build a farmer behavioral model, we estimated a mixed logit model on a data set of farmer survey responses to a discrete choice experiment (more details in Materials and Methods and Supplementary Information). Mixed logit models allow for preference heterogeneity on unobservable factors, allowing for a rich diversity of preferences for conservation contracts in a farmer population25. The model highlighted significant factors influencing farmers’ choices regarding conservation contracts (Fig. 1C and Table S1). The payment variable indicated that higher payments on average significantly increase the likelihood of farmers accepting conservation contracts (P < 0.001), underscoring the importance of financial incentives. Figure 1C presents standardized coefficient estimates, which are derived by multiplying the model coefficient by the standard deviation of the variable in question. A full set of coefficient estimates is presented in Supplementary Information.

We also observed a general hesitancy of farmers to agree to conservation contracts through a positive value in the alternative-specific constant (ASC) for the status-quo of no conservation contract (P = 0.003). As expected, the inclusion of each agricultural BMP had a negative impact on farmer desire for the contract, though only strict nitrogen application limits were statistically significant (P = 0.014). Model results revealed significant preference heterogeneity among farmers represented by large and significant standard deviation estimates of preference parameters for the ASC (P = 0.005) and for cover crops (P = 0.028). Results showed that the source of funding (state/federal agencies vs. private conservation groups) did not affect farmer willingness to agree to the contract.

Policy Simulations

To estimate the impact of conservation policies in our study area, we ran several SWAT+ simulations (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Our first, denoted Scenario 1, represents a baseline simulation for the current land use in the watershed. To establish this baseline, we used the annual average total nitrate loss from Hydrological Response Units (HRUs)-scale for the period of January 2003 to December 2019. Scenarios 2 and 3 represent the use of our hydrological model to simulate the effects of a 30% reduction in N-application and the use of winter wheat cover crop, respectively. Agricultural land represents 212 HRUs or 5,050 km2 in our model. For Scenarios 2 and 3 the 25% of agricultural land in the watershed that would yield the greatest NO3-N reductions from implementing the simulated BMP were identified (Supplementary Information). The scenarios then assumed that the specific BMP is applied to all land in these targeted HRUs. When performing a benefit-cost analysis of this policy action, we assumed that farmers are compensated for the BMP adoption at current cost share rates from the USDA’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP).

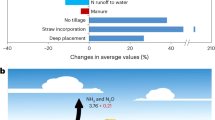

While both scenarios led to land management changes on 1,260 km² of agricultural land, annual average nitrate loss from all agricultural HRUs in Scenarios 2 and 3 were 1.03 × 107 and 9.74 × 106 kg NO3- -N, respectively (Table 2). Compared with annual average nitrate loss of 1.13 × 107 kg NO3- -N in the Baseline scenario, these represent significant decreases of 1.05 × 106 and 1.60 × 106 kg NO3- -N, using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Wilcoxon statistic = 0.0, p-value = 2.40e-09 for Scenario 2-Baseline comparison and Wilcoxon statistic = 0.0, p = 3.57e-08 for Scenario 3-Baseline comparison)26. The superior performance of the winter wheat cover crop in reducing nitrate loss is likely due to its ability to capture residual nitrogen27, which SWAT+ simulates through plant uptake and other nitrogen cycle processes. In comparison, reducing fertilizer application (Scenario 2), while effective overall, might not be as effective as the use of winter wheat cover crops in preventing nitrate leaching.

In contrast to the hydrological model simulations, Scenarios 4 and 5 used a socio-hydrological model. As in Scenarios 2 and 3, the socio-hydrological models identified the same 25% of agricultural land that resulted in the greatest nitrate export reductions from the target BMP. Rather than assuming growers will apply BMPs to all agricultural lands, the socio-hydrological model uses simulations based on our farmer behavioral model to predict the proportion of farmers who would agree to conservation contracts at the given compensation rate provided by EQIP in the targeted HRUs (Materials and Methods and Supplementary Information). These simulations revealed low enrollment (3.75% of farmers) for strict nitrogen restrictions, indicating reluctance towards committing to reducing fertilizer application. In contrast, cover crop adoption showed higher willingness (26.2% of farmers in our simulation), though the actual new acreage increase was more modest (14.5% of acreage), since about half of these farmers had already used cover crops on the same fields in the previous year, as indicated by their prior survey responses. Understanding these behavioral insights is crucial for designing effective environmental policies and simulating realistic agricultural management scenarios.

Scenario 4 (reduced N fertilization) led to management changes on only 50 km² of agricultural land and resulted in an annual average reduction of 42,000 kg NO3-N relative to the Baseline scenario. While Scenarios 2 and 4 evaluated the same basic policy, the hydrological model predicts that the policy will reduce agricultural nitrate export by 9.27% while the socio-hydrological model finds only a 0.37% reduction. While less extreme, model results revealed a similar trend with cover crops. Scenario 5 results in the conversion of 180 km² and a nitrate reduction of 187,000 kg NO3- -N. As with reduced N application, the socio-hydrological model predicts a much smaller cover crop impact of 1.65% nitrate reduction compared to the 14.1% reduction in the hydrological model.

We summarize the effectiveness and financial implications of each policy in Fig. 1B, which illustrates the impact of various policy scenarios on the total budget spent and the change in annual average nitrate export per area across all HRUs where the BMPs were implemented. Scenario 2 resulted in a cost of $15.5 million and total benefits equal to $21.9 million using an estimated benefit of $20.90 per kg of nitrate from Ribaudo et al.28, which translates to a predicted benefit-cost ratio of 1.41. Scenario 3 was estimated to cost $23.3 million, which was a higher price driven by the higher EQIP compensation rate for adopting cover crops. Coincidentally, the higher per-acre nitrate reduction from this policy resulted in a nearly identical benefit-cost ratio, of 1.44. Likewise, the socio-hydrological model did not substantially alter the benefit-cost ratios (ranging from 1.12 to 1.57), suggesting that failing to account for farmer preferences is less likely to lead to misperceptions in the efficiency of a policy and more likely to produce erroneous expectations in the scale of the change. This is in part, however, due to our similar targeting approach across models. Since all scenarios target only the top 25% of agricultural HRUs based on BMP effectiveness, they are in effect holding the efficiency of the policies relatively constant across hydrological and socio-hydrological models. model. By contrast, a model that held the scope of adoption constant would yield a reduced estimate of the policy’s effectiveness in the socio-hydrological model. In contrast to the $50 compensation per acre for reduced N application ad $75 compensation per acre for cover crops, our farmer behavioral model indicates that achieving adoption rates in Scenarios 4 and 5 that match the hydrological model adoption rates would require per acre payments of $339 and $264, respectively. Such payments would reduce the benefit-cost ratios to 0.32 and 0.27 for reduced N application and cover crop policies, respectively (see SI Section 8 for a discussion of survey and policy scenario limitations).

Conclusion

This study develops a socio-hydrological model by integrating hydrological modeling (engineering framework) with farmers’ behavioral responses (econometric framework) to manage nutrient loading in coastal watersheds, offering important policy insights. In the Tar-Pamlico watershed, the SWAT+ model effectively simulated nitrate loss from agricultural fields, demonstrating that a 30% reduction in fertilizer application and the use of a winter wheat cover crop significantly reduced nitrate export. The study developed a farmer behavioral model, revealing a general reluctance to adopt BMPs, with financial incentives as a crucial determinant. The socio-hydrological models, which account for farmer preferences, highlighted the overestimation of nitrate reductions (by factors of 8 for cover crops and 25 for reduced fertilizer applications, respectively) with the traditional hydrological modeling approach. Through this novel engineering-economics integrated framework, we underscore the importance of flexible, targeted policies for optimizing BMP adoption and cost efficiency. This study emphasizes the need for socio-economic integration in environmental modeling to develop more effective and sustainable watershed management strategies in the face of ongoing climate change.

The Tar-Pamlico basin, characterized by extensive agricultural activity and diverse land uses, provides a complex environment for implementing nitrate reduction policies. The varying results observed across scenarios can be attributed to the inherent differences in traditional hydrological and socio-hydrological models. It is noteworthy that the conclusions of this integrative work amount to a retelling of an old story in a novel way. This result shares the same theme of many other integrative research, specifically that models built on only natural or human dimensions will be biased. However, previous work often highlights how policy simulations erroneously assume status-quo behavior and ignore dynamic and nonlinear changes in behavior in response to policy changes. This current work highlights how standard policy simulations in hydrological modeling unrealistically ignore status quo behavior by presuming that a policy can achieve large land use changes when, under current conditions, farmers are not making those changes.

Overall, these findings underscore the importance of integrating socio-hydrological models into policy design, as they offer a more nuanced understanding of the interactions between human and natural systems. This approach is especially valuable in agri-environmental policy, where historical strategies have tended to avoid mandates and regulations in favor of voluntary incentive programs—programs that farmers can choose to adopt or reject at their own discretion. Understanding the preferences, constraints, and incentives that influence farmers’ decisions to adopt conservation practices is vital for designing effective environmental policies. These behavioral insights serve as foundational components for simulating policies within hydrological models, ensuring that such models reflect realistic agricultural management scenarios.

Materials and methods

Study Area

We applied the socio-hydrological modeling framework to the Tar-Pamlico watershed (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Information), a coastal watershed in eastern North Carolina covering 16,576 km2 and with a population of 470,000. This watershed, characterized by its diverse land use, including agriculture (27.9%), forests (33.9%), and wetlands (31.9%), supports a variety of crops with soybeans (40%), corn (19%), and cotton (19%) the predominate agricultural crops. The Tar-Pamlico watershed plays a significant role in nutrient discharges to the Pamlico estuary, an area currently facing challenges with algae blooms attributed to excessive nitrate levels29,30,31,32,33,34.

Hydrological model (engineering framework)

SWAT+ provides comprehensive modeling of watershed and sub-watershed dynamics, serving as a critical tool for decision-making in water resource management, agricultural planning, and environmental conservation. It offers insights into the effects of land management practices on water quality and agricultural productivity by simulating complex environmental processes. SWAT+ uses a semi-distributed hydrological framework and enhanced spatial flexibility, allowing detailed analyses of plant yield, denitrification rates, and nitrate loss in groundwater, surface water, and lateral flows. This capability supports policy development and planning, enabling evaluations of the impacts of land use changes on ecosystem health35.

In this study, we employed the SWAT+ model developed by Tapas et al.1, which was specifically optimized to simulate monthly flow and nitrate loads in the Tar-Pamlico River basin. The simulation period extended from January 2001 through December 2019, including a two-year warm-up. The model was then calibrated from January 2003 through December 2011 and validated from January 2012 through December 2019 for monthly flow and nitrate loads at Washington, NC. In addition, we cross-validated the model’s performance for monthly flow at Greenville and Tarboro, NC (January 2003 through December 2019). Tapas et al.1 employed a soft calibration procedure36 for key variables—including plant yield, denitrification, and nitrate export—at the HRU scale, thereby establishing an ideal platform for implementing and assessing various agricultural BMPs and their impacts on nutrient loss from agricultural fields. Further details regarding the SWAT+ model1 can be found in Supplementary Information.

BMP Simulation

We simulated two commonly used BMPs in watershed modeling (Fig. 2): cover crops and reduced fertilizer application rates37,38. Winter wheat was the cover crop, which is commonly used in the Tar-Pamlico Basin39. We simulated planting of the cover crop 14 days after harvesting the main summer cash crop. The cover crop was terminated prior to planting the summer crop the following spring. We applied a 30% reduction in nitrogen fertilizer use to simulate policies related to nitrogen application restrictions.

Farmers’ behavioral model (econometrics framework)

We conducted a survey (Supplementary Information) among farmers in the Tar-Pamlico River basin and other coastal areas in eastern North Carolina to gauge farmers’ interest in voluntary conservation programs. By incorporating scenarios that reflect aspects of existing and hypothetical agricultural working land support programs (i.e., Environmental Quality Incentives Program, or EQIP), the survey sought to capture farmers’ perspectives on and likely response to potential policies and economic incentives. The survey asked farmers about their specific farming practices, environmental concerns, and the potential impact of policy changes on these practices (more details in Supplementary Information). The survey incorporated a choice experiment to gauge farmers’ preferences for various hypothetical voluntary conservation contracts aimed at reducing nutrient export (Supplementary Information). The response rate was 16%, and we received in total 76 responses providing enough data to include them in the construction of the farmer behavioral model. Our farmer behavioral model is built on a Random Utility Maximization (RUM) framework and farmer preferences for conservation contracts were modeled using a mixed logit model (Supplementary Information). To counteract hypothetical bias in our survey responses, we used a certainty recoding approach40,41,42.

Estimation of farmer willingness to accept (WTA)

Using the results of our mixed logit model, we simulated farmer-specific preference parameters for the respondents (Supplementary Information). For each set of preference parameters, we used Hanemann’s compensating variation formula42 to estimate WTA for a specific conservation contract. The WTA represents the minimum amount a farmer would accept to adopt the contract and is derived from estimated utility differences between the contract, status-quo of no contract, and the estimated marginal utility of income (Supplementary Information).

Simulation of Agri-environmental Policy (Socio-hydrological model integration)

Integrating the SWAT+ and farmer behavioral models is a crucial step toward achieving a comprehensive understanding of watershed dynamics and agricultural decision-making processes43. By combining the insights gained from the farmer behavioral model (econometric framework) with the SWAT+ hydrological model (engineering framework), we developed an integrated framework (Fig. 2) that bridges the gap between policy interventions and on-the-ground agricultural practices44. By analyzing farmers’ willingness to adopt the target practices based on the incentives offered using current standard EQIP cost share rates, we estimated the extent of land conversion for cover crops and reduced fertilizer application. This integration allowed us to assess the effectiveness of incentive programs in promoting sustainable agricultural practices and inform policymaking for environmental conservation45.

Table 1 outlines five distinct scenarios simulated in this study. Scenario 1 serves as the baseline, involving no implementation of additional BMPs. In addition to Scenario 1, we conducted a trial run by separately implementing the two BMPs on all HRUs to identify the top-performing HRUs, defined as an HRU that experienced the largest estimated difference in nitrate loss between Scenario 1 and our run with the target BMP applied to all HRUs. Using the findings from these trials, we identified the HRUs where the practice was most effective, representing the top 25% of agricultural acreage in the watershed in terms of nitrate reduction, for each BMP. From an engineering perspective, these HRUs are considered the most ideal areas for BMP implementation to minimize the watershed’s nitrate export46. Scenarios 2 and 3 explored the impacts of a 30% reduction in N-fertilizer application rates and the use of cover crops, respectively, on the target 25% of agricultural land. These scenarios provided conservation contracts at current EQIP rates ($50 per acre for nutrient application reduction, $75 per acre for cover crops) and simulated perfect adoption and land use change within the targeted HRUs.

Scenarios 4 and 5 also examined the effects of reduced N-fertilizer application and cover crops, respectively, but these were based on a socio-hydrological model that incorporates the farmer behavior model. Parameter estimates from the farmer behavioral model generated farmer-specific WTA estimates for the target conservation contracts. In the simulation of farmer acceptance of these contracts, we assumed that any farmer whose estimated WTA is at or below the offered per-acre compensation of the contract will prefer the offered contract to the status quo and accept the new contract. Any farmer whose estimated WTA exceeds the offered payment in the contract prefers the status quo and will not accept the new contract. This approach allowed us to predict the proportion of farmers who will accept the conservation contracts offered and, consequently, what percentage of targeted HRUs will be converted. As with Scenarios 2 and 3, the policy is targeted at only the most productive quarter of HRUs, so all HRUs that are not targeted will not be converted to the BMP in question.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Information and through publicly accessible databases, with specific datasets accessible via the US Geological Survey (USGS), National Land Cover Database (NLCD), and Soil Survey Geographic Database (SSURGO). Links and details are provided in the Supplementary Information.

References

Tapas, M. R. et al. A methodological framework for assessing sea level rise impacts on nitrate loading in coastal agricultural watersheds using SWAT + : A case study of the Tar-Pamlico River basin, North Carolina, USA. Science of The Total Environment, 175523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175523 (2024a).

Wurtsbaugh, W. A., Paerl, H. W., & Dodds, W. K. Nutrients, eutrophication and harmful algal blooms along the freshwater to marine continuum. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 6, e1373 (2019).

Howarth, R. et al. Coupled biogeochemical cycles: eutrophication and hypoxia in temperate estuaries and coastal marine ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 9, 18–26 (2011).

Hautier, Y., Niklaus, P. A. & Hector, A. Competition for light causes plant biodiversity loss after eutrophication. Science 324, 636–638 (2009).

Kapsalis, V. C., & Kalavrouziotis, I. K. Eutrophication—A worldwide water quality issue. Chemical Lake Restoration: Technologies, Innovations and Economic Perspectives, 1–21 (2021).

Mishra, G. J., Kumar, A. U., Tapas, M. R., Oggu, P. & Jayakumar, K. V. Evaluating hydrological alterations and recommending minimum flow release from the Ujjani dam to improve the Bhima River ecosystem health. Water Sci. Technol. 88, 763–777 (2023).

Mankar, T. S., Mane, S., Mali, S. T. & Tapas, M. R. Analysis and development of watershed for ruikhed village. Maharashtra-A Case Study Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 7, 2265–2270 (2020).

Kreiling, R. M., Thoms, M. C. & Richardson, W. B. Beyond the edge: linking agricultural landscapes, stream networks, and best management practices. J. Environ. Qual. 47, 42–53 (2018).

Dabney, S. M., Delgado, J. A. & Reeves, D. W. Using winter cover crops to improve soil and water quality. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 32, 1221–1250 (2001).

Wendling, M. et al. Influence of root and leaf traits on the uptake of nutrients in cover crops. Plant Soil 409, 419–434 (2016).

Shibu, M. E., Leffelaar, P. A., Van Keulen, H. & Aggarwal, P. K. LINTUL3, a simulation model for nitrogen-limited situations: application to rice. Eur. J. Agron. 32, 255–271 (2010).

Prabha, J. A. & Tapas, M. R. Event-based rainfall-runoff modeling using HEC-HMS. IOSR. J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 17, 41–59 (2020).

Wendell, A.-K. et al. A spatio-temporal analysis of environmental fate and transport processes of pesticides and their transformation products in agricultural landscapes dominated by subsurface drainage with SWAT + . Science of The Total Environment, 173629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173629 (2024).

Inseeyong, N., Hu, H., Chuenchum, P., Yu, B., & Xu, M. Staged SWAT calibration with bias-corrected precipitation product for enhancing flow data continuity in tributaries of the Mekong River. Science of The Total Environment, 173291 (2024).

Tran, T. N. D. et al. Comparison of SWAT and SWAT + : Review and Recommendations. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts (Vol. 2023, pp. H31O-H31672).

Veisi, H., Jackson-Smith, D. & Arrueta, L. Alignment of stakeholder and scientist understandings and expectations in a participatory modeling project. Environ. Sci. Policy 134, 57–66 (2022).

Sharma, N. N., Tapas, M. R., & Kumar, A. U. (2022). Drought Monitoring Indices. Meteorology and Climatology, 53.

Howard, G., Zhang, W., Valcu-Lisman, A. & Gassman, P. W. Evaluating the tradeoff between cost effectiveness and participation in agricultural conservation programs. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 106, 712–738 (2024).

Behboudian, M., Anamaghi, S., Mahjouri, N. & Kerachian, R. Enhancing the resilience of ecosystem services under extreme events in socio-hydrological systems: a spatio-temporal analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 397, 136437 (2023).

De Bruijn, J. A. et al. GEB v0. 1: a large-scale agent-based socio-hydrological model–simulating 10 million individual farming households in a fully distributed hydrological model. Geoscientific Model Dev. 16, 2437–2454 (2023).

Tapas, M. R., Kumar, U., Mogili, S. & Jayakumar, K. V. Development of multivariate integrated drought monitoring index (MIDMI) for Warangal region of Telangana, India. J. Water Clim. Change 13, 1612–1630 (2022a).

Tapas, M., Etheridge, J. R., Howard, G., Lakshmi, V. V., & Tran, T. N. D. (2022b, December). Development of a Socio-Hydrological Model for a Coastal Watershed: Using Stakeholders’ Perceptions. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts (Vol. 2022, pp. H22O-H20996).

Castilla-Rho, J. C. Groundwater modeling with stakeholders: finding the complexity that matters. Ground Water 55, 5 (2017).

Di Baldassarre, G. et al. Sociohydrology: scientific challenges in addressing the sustainable development goals. Water Resour. Res.8, 6327–6355 (2019).

Train, K. E. Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge university press (2009).

Wilcoxon, F., Katti, S. & Wilcox, R. A. Critical values and probability levels for the Wilcoxon rank sum test and the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Sel. tables Math. Stat. 1, 171–259 (1970).

McCracken, D. V., Corak, S. J., Smith, M. S., Frye, W. W. & Blevins, R. L. Residual effects of nitrogen fertilization and winter cover cropping on nitrogen availability. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 53, 1459–1464 (1989).

Ribaudo, M. O., Heimlich, R. & Peters, M. Nitrogen sources and Gulf hypoxia: potential for environmental credit trading. Ecol. Econ. 52, 159–168 (2005).

NCDEQ North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality. (2014). Tar-Pamlico Basin Plan. North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality. https://www.deq.nc.gov/about/divisions/water-resources/water-planning/basin-planning/river-basin-plans/tar-pamlico# 2014Tar-PamlicoBasinPlan-4040

Tapas, M. (2024b). Integrative analysis of policy changes for a coastal watershed: implications for agriculture and ecosystem health. East Carolina University. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10342/13413

Tapas, M. R. How do satellite precipitation products affect water quality simulations? A comparative analysis of rainfall datasets for river flow and riverine nitrate load in an agricultural watershed. Nitrogen 4, 1015–1030 (2024c).

Tapas, M. R., Etheridge, R., Le, M. H., Hinckley, B. & Lakshmi, V. Evaluating combinations of rainfall datasets and optimization techniques for improved hydrological predictions using the SWAT+ model. J. Hydrol.: Regional Stud. 57, 102134 (2024).

Tran, T. N. D., Tapas, M.R., Do, S.K., Etheridge, R., Lakshmi, V. Investigating the impacts of climate change on hydroclimatic extremes in the Tar-Pamlico River basin. North Carolina. J. Environ. Manage 363, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121375.

Yin, D. et al. Effects of sea-level rise and river flow variation on estuarine salinity in a changing climate: insights from the Pamlico River Estuary, USA. In 2024 Ocean Sciences Meeting. AGU (2024).

SWAT + IO Document. Input/output file documentation, version 2016 modified on November 16, 2020 according to REV 60.5. (2020). Retrieved from https://swatplus.gitbook.io/io-docs.

Etheridge, J. R. et al. Reducing uncertainty in the calibration and validation of the INCA-N model by using soft data. Hydrol. Res. 45, 73–88 (2014).

Lu, Y. C., Watkins, K. B., Teasdale, J. R. & Abdul-Baki, A. A. Cover crops in sustainable food production. Food Rev. Int. 16, 121–157 (2000).

Sainju, U. M., Whitehead, W. F. & Singh, B. P. Cover crops and nitrogen fertilization effects on soil aggregation and carbon and nitrogen pools. Can. J. Soil Sci. 83, 155–165 (2003).

Cowger, C. & Weisz, R. Winter wheat blends (mixtures) produce a yield advantage in North Carolina. Agron. J. 100, 169–177 (2008).

Champ, P. A., Moore, R. & Bishop, R. C. A comparison of approaches to mitigate hypothetical bias. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 38, 166–180 (2009).

Beck, M. J., Fifer, S. & Rose, J. M. Can you ever be certain? Reducing hypothetical bias in stated choice experiments via respondent reported choice certainty. Transportation Res. Part B: Methodol. 89, 149–167 (2016).

Hanemann, W. M. Welfare evaluations in contingent valuation experiments with discrete responses. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 66, 332–341 (1984).

Liu, Y., Gupta, H., Springer, E. & Wagener, T. Linking science with environmental decision making: Experiences from an integrated modeling approach to supporting sustainable water resources management. Environ. Model. Softw. 23, 846–858 (2008).

Du, E. et al. Exploring spatial heterogeneity and temporal dynamics of human-hydrological interactions in large river basins with intensive agriculture: A tightly coupled, fully integrated modeling approach. J. Hydrol. 591, 125313 (2020).

Cheng, G., & Li, X. Integrated research methods in watershed science. Sci. China Earth Sci. 58, 1159–1168 (2015).

Sheshukov, A. Y., Douglas-Mankin, K. R., Sinnathamby, S. & Daggupati, P. Pasture BMP effectiveness using an HRU-based subarea approach in SWAT. J. Environ. Manag. 166, 276–284 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible with support from the Center for Sustainable Energy and Environmental Engineering, the Integrated Coastal Sciences Program at East Carolina University, and the Coastal Studies Institute. Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation [Grant Numbers: 2009185 and 2052889]. We would like to thank all the farmers who gave their valuable time in filling out the survey. Additionally, we would like to thank Dr. Venkat Lakshmi, Duc Tran, Brian Hinkley, Dr. David Griffith, Kate Lamkin, Colin Finlay, Jullie Miller, Zeke Holloman, and Dr. Natasha Bell for their contributions to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R.T., G.H., R.E., and A.L.P. designed research; M.R.T., G.H., R.E., and M.M. performed research; M.R.T., G.H., and R.E. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; M.R.T. and G.H. analyzed data; and M.R.T. and G.H. wrote the paper with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Liuyue He, C. Dionisio Pérez-Blanco and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Wenfeng Liu and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tapas, M.R., Howard, G., Etheridge, R. et al. Integrating human decision-making into a hydrological model to accurately estimate the impacts of agricultural policies. Commun Earth Environ 6, 412 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02325-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02325-x

This article is cited by

-

Climate change impacts on in-stream carbon cycling dynamics in the Miho River Watershed, South Korea

Environmental Earth Sciences (2025)

-

A Comprehensive Evaluation of Hydro-Geomorphometric Traits for Prioritising Flood Hazard Potential Watersheds in the Western Ghats of India

Earth Systems and Environment (2025)

-

Effective Removal of Arsenic (III) From Aqueous Solution and Salt Lake Water Using Novel Calcium Alginate/Modified Biochar Aerogel Spheres

Earth Systems and Environment (2025)