Abstract

Deforestation from artisanal, small-scale gold mining is transforming large regions of the tropics, from lush rainforest to barren collections of tailings and ponds. Natural forest regeneration is slow due to dramatic soil changes, and existing reforestation strategies are failing. Here we combine remote sensing, electrical resistivity imaging, and measurements of soil properties to characterize post-mining areas in the Madre de Dios region, Peru. We find that the post-mining landscape has dramatically changed water infiltration dynamics, driving decreases in subsurface water availability and presenting a major barrier to revegetation. Mining tailings are extremely hydraulically conductive, allowing for 14.76 m day−1 infiltration relative to 0.074 m day−1 in primary forest soils, leading to lower average soil moisture and extreme temperatures (60 °C). Electrical resistivity imaging reveals a highly resistive, 1.5–2 m deep layer of dry sand across the mining landscape. Areas close to the water table (e.g., pond edges) show higher soil moisture, lower temperatures, and greater natural regeneration compared to topographically elevated tailings. Our results suggest that access to water should be prioritized when targeting reforestation sites, potentially requiring large-scale geomorphological reconfiguration. As gold mining is expected to expand, responsible practices and remediation strategies must account for the critical yet often overlooked role of water.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropical rainforests cover ~10% of Earth’s land surface but are of outsized environmental importance, both globally and regionally. They are home to 1/2–2/3 of Earth’s species1, remove and sequester 150–200 billion tons of biomass carbon2, and regulate continental-scale climate3. The Amazon rainforest alone is home to 47 million people, including 2.2 million Indigenous people from 400 different ethnic groups, many of whom rely on the forest for livelihoods. Yet the ecosystem services from the Amazon, like many tropical forests, have been left vulnerable by decades of unsustainable land-use practices, climate change, and socio-political turmoil. Artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) is an especially noteworthy land-use practice for its wide-ranging and pernicious environmental legacy.

Gold mining in the global tropics drives deforestation4,5,6, degrades soils through heavy-metal contamination, top-soil removal and nutrient leaching7,8,9, and damages rivers through increased erosion and sedimentation10,11. In tandem, ASGM poses a major risk to human health via exposure to toxins, particularly mercury (Hg)12,13, and is associated with a legacy of exploitation through human trafficking and violence towards local activists14,15. The main driver of this devastation is the Global North’s demand for increasing quantities of gold at lower prices16.

Given the growing footprint of ASGM in the tropics and the limited success of many interventions17, data-informed strategies for recovery are needed8. Generally, tropical reforestation methods have focused on agricultural or logged landscapes, but these approaches are inadequate for dealing with the degradation from surface mining8,18. Natural regeneration of ASGM areas on a large scale is slow and incomplete; for example, no regeneration of woody biomass was measurable in the first 3–4 years after abandonment of some mining sites in Guyana19, and secondary forests in Peruvian mining sites only reached 9–30% of the species richness of average primary forests20,21. Limited regeneration has been attributed to forest fragmentation (inhibiting natural seed dispersal) and degraded soils20. The challenges associated with the spatial extent and high levels of subsurface degradation from ASGM require creative solutions underpinned by deep understanding of the post-mining landscape.

In many settings, the aftermath of mining is a mosaic of mining ponds and tailings piles13. Post-mining revegetation on the mounds of remnant bare sand and gravel is often particularly limited21. The environmental transformation from mining dramatically alters when and where water is available for vegetation—yet little attention has been paid to how these hydrological changes affect the regrowth of forests across the post-mining landscape. In this work, we reveal how lack of access to water in the rooting zone is a barrier to reforestation in mining regions. We combine remote sensing, near-surface geophysics, and field measurements to assess the post-mining hydroscape and its relationship to patterns of natural reforestation. We find that vegetation regrowth is tied closely to subsurface water, and is limited by the sand and gravel-rich tailings which are characterized by rapid soil infiltration rates, high temperatures, and low moisture content in the rooting zone. This work sets a path forward for future targeted reforestation and calls for best practices in mining that limit hydrological disruption and the associated legacy of dry, barren tailings piles.

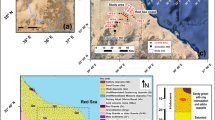

Our study focuses on the Madre de Dios (MdD) region of southeastern Peru bordering Brazil and Bolivia, a global “capital of biodiversity” that has been substantially altered by recent gold mining (Fig. 1). The MdD sits at the foothills of the Andes mountains, at the transition to the Amazon basin. Modern ASGM in this region began in the 1980s and expanded throughout the 2000s, causing 95,750 ha forest loss as of 2017 and leading to widespread expansion of lake environments (see “Methods” for more detail). Illegal mining is threatening protected areas, such as the Tambopata National Reserve and buffer zone as well as indigenous communities, and continues despite multiple military interventions.

a Regional map of the Madre de Dios watershed with zones of suction mining (yellow) and excavation mining (brown) from Caballero-Espejo et al.5 demarcated. b Locational map of the Madre de Dios region. Locational maps of electrical resistivity imaging (ERI) and hydraulic conductivity (HC) sampling sites for excavation mining sites (c) and suction mining sites (d). White inset boxes indicate areas of profiles in Fig. 3, and yellow dashed inset box demarcates area in Fig. 4 with 2024 base imagery (Imagery © Planet Labs PBC 2024. All rights reserved).

The legacy of ASGM in this region varies based on the type of mining5. In the Huepetuhe area, ASGM is done using heavy machinery (excavation style) due to the large grain size of the material and the accessibility of the terrain for machinery. This type of mining leaves behind shallow (1.5–2 m) ponds and tall (10–50 m) tailing piles of mixed grain sizes from sand to cobbles (Fig. 2b, d). In other areas, particularly where mining has expanded since the late 2000s, most mining is done using high pressure water cannons to liquify sediments and suction pumps to transport them to inclined sluices (Fig. 2e). This approach is better suited to finer-grain-size deposits. In suction mining, topsoil is washed away into ponds and surrounding forests and rivers (leading to further forest and river degradation), leaving gold-bearing sand (from up to 10 s meters depth) to be processed. Suction mining requires large volumes of water, leading to a landscape of deep (2–7 m) mining ponds and sand in place of rainforest and clay-rich soils (Figs. 1c and 2a, c). While both mining styles deforest the landscape, topsoil can be preserved and later replaced during excavation but not typically during suction mining (Fig. 2d, f). These differences have implications for future land use, hydrological disruption, and biogeochemical cycling of mercury and other metals. Our study focuses on two suction mining sites in the La Pampa region (Balata and Azul) and one excavation mining site in the Huepetuhe region (Cinco Rebeldes). The sites are shown in Fig. 1 (see “Methods” for further site descriptions).

a Drone image of suction mining site with ponds and tailing piles (photo credit: A. J. West); b Aerial image of Cinco Rebeldes with tailing piles on left and ponds on right (image courtesy of Google Maps); c Suction mining site LP-6 (deforested in ~2016) and d Excavation mining site from top of tailings pile (mined in 2018) (photo credit: A. Atwood); e Example of suction mining process in Balata (photo credit: A.J. West, Sept. 2024); f Example of excavation mining with topsoil preservation at Cinco Rebeldes (photo credit: A. Atwood).

Results

Remote sensing

In the suction mining region of Balata, tailings piles (typically <10 m relief; Fig. 3) are produced via the sluicing process from the mining ponds and as a result are often relatively close to pond edges. Examples of elevation cross-sections from high-resolution topography (see “Methods”) show these piles are often steep-sided near the pond edge and have lower slopes away from the pond. Natural regeneration (vegetation regrowth from 2019 to 2023) in this area is located dominantly at pond edges, near pre-existing vegetation, or in low-lying areas (Fig. 3a, b). The elevated tailings have limited regrowth, except when they are close to pond edges or undisturbed primary forest (i.e., respective ends of the Z-Z′ line). These patterns are also evident at a landscape scale where natural regeneration pixels fall near either a forest edge (median distance: 7.1 m) or a pond (median distance: 16.1 m) (Fig. 4a). Bare earth pixels have a much wider distance distribution, where median distances from forest edge and pond are 34.3 m and 25.1 m, respectively (Fig. 4b).

a Maps (see Fig. 1 for locations in Balata) of cross-sectional lines showing ponds (blue), revegetation pre 2019 (pink) and revegetation post-2019 (red); b Cross-sectional profiles of LiDAR derived relief (brown) and satellite-derived NDVI of revegetation post 2019 (green).

Distribution of distances to nearest pond and forest for all natural regeneration pixels (n = 7.7 million) (a) and bare earth pixels (n = 7.2 million) (b) in yellow box from Fig. 1.

Electrical resistivity imaging (ERI)

Electrical resistivity can reflect subsurface properties, including material type and water content, with the latter having an inverse effect on resistivity (increased water content, lower resistivity)22. Across the suction mining areas, primary forest sites show minor lateral and vertical heterogeneity (e.g., Fig. 5b and SI Fig. 1) both within each profile as well as between profiles. Median resistivity ranges from 382 to 632 Ω-m with depth for all primary forest sites, with less electrically resistive soils found in former floodplain sites (i.e., AZ-4 and AZ-5, SI Fig. 1). Post-mining deforested sites all have the common structure of a highly resistive layer at the surface (down to 1.5–2 m depth) (median: 1381 Ω-m) underlain by a low-resistivity, homogenous layer (251 Ω-m) (Fig. 5a, b). A pit dug alongside sites LP-6 and 7 revealed a homogenous dry sand layer above the water table at 1.4 m, corresponding with the resistive to conductive change in the ERI (Fig. 5b). Seasonal differences in ERI profiles are negligible at all sites, consistent with minimal changes (<50 cm) in pond water level seasonally (SI Figs. 1 and 2).

1-dimensional electrical resistivity data distribution with depth from suction mining sites (a) and excavation mining sites (c) with median (dark line) and 5–95th quantile range shown for each land cover type sampled. Excavation mining sites include top and bottom of tailing piles. (b) and (d) show representative two-dimensional electrical resistivity imagery cross-sections with annotations. See SI Figs. 1 and 3 for all cross-sections. (b) includes image of soil pit showing dry sand until 1.4 m where sand is saturated.

Two deforested sites in Azul (AZ-2 and AZ-3) contained reforestation plots (planted trees). The ERI profiles from these locations reveal highly resistive surface layers, and photographs taken over 1.5 years show no visible tree growth. Measurements at sites of natural regeneration in Balata (LP-9) show the same structure as other deforested sites (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 1).

At the excavation mining sites, ERI results from the primary forest site show higher baseline resistivity than in the suction mining sites (Fig. 5c), consistent with the larger grain size and less clay-rich soils present closer to the foothills of the Andes Mountains. The ERI profiles show moderate lateral and vertical variability during both wet and dry seasons, similar to the forested suction mining sites. The deforested excavation mining sites show high variability throughout, in contrast to the suction mining sites (Fig. 5c). Two sites at the base (HU-1) and top (HU-2) (Fig. 5d) of tailings piles are strikingly different. At the base of the pile, resistivity is low below 1.5 m (median resistivity: 365 Ω-m) with a moderately resistive layer at the surface (<1.5 m; median resistivity: 1401 Ω-m). At the top of the tailings pile, resistivity is very high throughout the whole profile (median resistivity: 7809 Ω-m). The natural regeneration site has relatively high resistivity but with greater seasonality than seen in any other profile in the region, with a noted decrease in resistivity in the first 1–2 m during the wet season (SI Fig. 3).

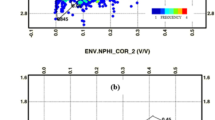

Hydraulic conductivity

We observed a two to three order of magnitude increase in hydraulic conductivity for mining soils compared to their undisturbed counterparts. Average field-saturated hydraulic conductivities (Kfs) were lowest in the primary forest (0.074 m day−1), followed by naturally regenerating forest (7.71 m day−1), and were highest in deforested mining regions (14.76 m day−1) (Fig. 6d). Similarly, unsaturated hydraulic conductivity (k) values increased in response to mining-induced land use changes, despite greater variability. The average k values for primary forest, natural regeneration, and deforested sites were 0.192 m day−1, 4.33 m day−1, and 29.29 m day−1, respectively (Fig. 6d). Notably, k values for new-growth ranged between those of primary and deforested sites, whereas Kfs values in new-growth sites did not approach those of primary forest values.

a Temperature sensor time series from different land covers. Three sensors (two from sand, one from the pond adjacent) were stolen from the sites during fall of 2023, while the clay loam site sensor was consumed by ants during the same period. b Drone-paired optical and thermal images showing systematically higher temperatures in deforested regions versus primary forest. Temperatures calculated from radiometric image for humidity 80%, surface emissivity 0.90, and reflected temperature 28.0 °C. c Soil moisture time series from different land covers; legend as for (a). d Field saturated hydraulic conductivity (Kfs) and unsaturated hydraulic conductivity (k) across sites. Los Amigos Field Station on the Madre de Dios River is included as a second control site characterized by primary forest.

Differences in Kfs values taken during the dry and wet seasons were minimal in deforested and naturally regenerating sites; however, primary forest values taken near foot and vehicular paths tended to be lower in the wet season, which we attribute to the compaction of wetted clay. Wet season k values were more varied than dry season values, and while measurements were not taken in visibly saturated surfaces during precipitation events, in mined sites the seasonal difference can be attributed to a departure from completely unsaturated conditions (such as water from recent rainfall events remaining in pores). In vegetated sites, dissimilar wet season k values could be due to site-specific differences in critical moisture thresholds23.

Temperature and soil moisture time series

Soil temperature sensor data (Fig. 6a) show elevated temperatures in sand at mining sites (median = 27.1 °C), with temperatures reaching as high as 63 °C. Slightly lower temperatures were recorded in the pond-adjacent site (median = 26.9 °C) but without the extreme temperatures (max = 35.9 °C). Compared to the mining sites, temperatures in the forested soils were lower (median = 24.5 °C (clay loam), 24 °C (clay), max = 35.9°C (clay loam), 26.4 °C (clay)). Thermal drone imagery (Fig. 6b) corroborates these patterns, with higher temperatures in barren soil, and lower temperatures in forests and around ponds.

Soil moisture in forested sites was relatively high (50–60%) but shows differing patterns between the clay loam and clay soil types. The clay site maintained elevated soil moisture (60%) throughout the wet season, with increased variability at the end of the dry season and beginning of the wet season (Sept–Jan), while the clay loam shows rapid increases and decreases between 50% and 60% throughout the year. In the deforested sites soil moisture was lower, generally between 10% and 40%. The sand sites show similar patterns to the clay loam site, with extreme, rapid swings. In the site adjacent to a pond, soil moisture stayed around 40%, and its pattern was more like the primary forest clay. Calculated drying rates also reflect these patterns: sand and the organic layer dried rapidly compared to the clay-rich soils and pond-adjacent sands (SI Figs. 4 and 5).

Discussion

Aside from successional revegetation around the primary forest in suction mining regions20,24 (Fig. 4a), regrowth was mostly limited to pond perimeters (Figs. 3a and Fig. 4a). The soils in these areas are characterized by sands with high moisture content that exhibit more regulated annual wetting cycles (Fig. 6c), because of proximity to the water table. When regeneration did occur outside these edges, it was generally in areas of low topographic relief, typically between the large tailing piles that characterize a majority of the bare surface, and where the subsurface water is more readily accessible (e.g., middle of Y-Y’ profile in Fig. 3b; LP-8 in SI Fig. 1).

Our ERI and soil analysis results confirm that the sandy tailings piles in suction mining areas act like a sieve through which water rapidly infiltrates to 1.5–2 m depth, at which point it reaches the water table. Hydraulic conductivity in the sand tailings is ~2 orders of magnitude higher than at forested sites, and soil moisture is low, decreasing rapidly after rain events with a drying rate five times higher than clay-rich soils (1.48% day−1 vs 0.3% day−1). In contrast, soils in the primary forest have low hydraulic conductivity, and no high-resistivity surface layer is seen in the ERI results. Here, soil moisture changes much less intra-annually, and soil temperatures do not reach the extremely high values found in the mining zones. In natural successional zones, such as along meandering riverbanks where vegetation resembles that of mining zones undergoing natural regeneration, the subsurface is more like that of primary forests. These areas are characterized by alternating layers of clay and sand with no high-resistivity surface layer as seen in the mining areas (SI Fig. 1).

Although the mining methods and resulting post-mining landscapes differ, the natural regeneration observed in excavation mining zones is comparable to that in suction mining sites. Natural regeneration was highest around the shallow ponds where plants could readily access water, although at Cinco Rebeldes these locations were often (but not always) colocated with areas of preserved topsoil. Despite their varying grain sizes (sand to cobble), the large tailings piles exhibited similar characteristics to the sandy tailings from suction mining, namely high hydraulic conductivity and high electrical resistivity. These tailing piles at Cinco Rebeldes also have extremely limited plant regrowth (Fig. 2b, d), in contrast to lower areas near ponds. This example illustrates how the combination of topsoil preservation and water table access can create favorable conditions for rapid regeneration, whereas the post-mining geomorphological reconfiguration of tailing piles can lead to extremely limited regrowth.

Other factors in addition to water availability may also influence vegetation regrowth and success of active replanting. Temperatures in deforested sites were higher on average than forested sites and reached much higher maximum temperatures. Such high temperatures can affect seed germination (Tmax~35–40 °C for moist tropical forests)25, photosynthesis (thought to fail at ~46.7 °C)26, and root function27. These effects can be complex but lead to overall increased plant stress at high temperatures27. At our pond-adjacent site, temperatures never reached the maxima seen at other deforested sites and remained below 35 °C. Thus, the landscape controls on soil moisture may be important not only in controlling water availability but for their moderating effect on local temperature. While we cannot distinguish the physiological roles of T vs. water limitation, these factors work together to restrict revegetation on “high, dry, and hot” tailings piles.

Additionally, sandy post-mining soils have decreased soil organic matter and cation exchange capacity as well as decreased soil structure9. As a result, adding fertilizer, transplanting with soil (versus bare root planting), and using biochar have increased survivorship during reforestation21,28. However, large-scale implementation remains prohibitively expensive. Moreover, growth reported in these prior studies was poor regardless of these treatments, suggesting nutrient depletion is not the sole limiting factor in reforestation success, with water being a major missing ingredient based on our results.

Our sites spanned a range in age following the end of mining activity, from >7 years (in Azul) to ~1 year (at some sites in Balata). At Azul, hydraulic conductivity values were overall lower than at Balata (Fig. 6d). We attribute these differences to more mature soil development and root growth at Azul, though the Azul and Balata sites also differ in distance from the active river channel and typical mining pond size. Some post-mining sites at Azul had k values similar to those of the primary forest, potentially due to accumulation of organic debris on the soil surface. Such evolution is similar to previously published changes in grain size in years post-mining in the MdD29 (see SI Table 1). In contrast, Kfs values remain higher than in the primary forest, and electrical resistivity profiles showed little evidence of subsurface conditions returning to those characteristic of the primary forest (Figs. 5 and 6)—emphasizing that even as surface conditions start to recover, the underlying substrate remains disturbed. Nonetheless, we speculate that, once initiated, the beginning stages of soil recovery and reduction in k values may facilitate further revegetation through moisture retention in the shallow rooting zone. Furthermore, once trees are established, we expect that they will be able to access the water at 1.5–2 m depth.

Our results suggest that the current post-mining landscape is inhospitable to both natural regeneration and reforestation due to geomorphic reconfiguration that has left parts of the landscape isolated from water, primarily because of the high hydraulic conductivity and elevated topography of tailing piles (see SI Fig. 6 for examples of reforestation). Small packets of hydrophilic gels can be deployed during reforestation to aid new transplants with retaining water during rain events. While effective, these are difficult to use at a large scale. Given the minimal natural regrowth21 and magnitude of the deforested zone, larger-scale engineered changes to post-mining landscapes may need to be considered to facilitate reforestation.

We specifically suggest lowering the elevation of tailing piles and backfilling ponds to improve revegetation success. Backfilling ponds has been proposed as a top recommendation for ASGM post-mining remediation, though primarily aiming to decrease standing water rather than to homogenize the terrain for more uniform surface depth to water table for revegetation8. Our results suggest that tailings redistribution and backfilling could enable more continuous access to the water table for seedlings, promoting increased growth and improved reforestation success. While backfilling can happen naturally through erosion, the timescales over which this might occur are likely to be untenable for present-day reforestation. In excavation zones, topsoil preservation and redistribution will also improve reforestation, as seen in part at Cinco Rebeldes and past work8. In suction mining zones, especially where illegal mining occurs, preservation of topsoil is likely difficult, but should be promoted locally to encourage rapid regeneration and to save costs on expensive fertilizer amendments for future reforestation efforts9,20. Developing guidelines and communicating with miners, especially at legal concessions, about the benefits of preserving topsoil, minimizing tailing pile elevations during mining activities, and immediately backfilling ponds may help reduce the need for post-mining remediation.

Heavy metal mobilization, especially mercury, is a major environmental concern associated with mine tailing piles and mining ponds. In prior work on MdD mining sites, Hg content has been found to be low (>0.1 mg kg−1) in sandy tailing piles and undisturbed forests28,30, regardless of mining style30, with undisturbed forests consistently having higher Hg content than tailing sands. This low Hg content in the tailing piles is due to the lack of clay, lowering cation exchange capacity and limiting Hg adsorption. In contrast, mining ponds have high measured total Hg and methylmercury (MeHg)13. These ponds frequently have clay-rich sediments with high affinity for Hg, and they host environments (e.g., anoxic bottom waters and sediments) that promote methylation and preservation of MeHg. Backfilling ponds to >0.75 m could limit pond water stratification31 and thus anoxia and MeHg production, while also promoting forest regrowth.

Another potential avenue for remediation would be sand removal via quarrying, depending on sand quality. Sand is an important and limited natural resource for construction in Peru as elsewhere in the world32, and the MdD already has multiple sand quarries. Assessing and potentially utilizing sand tailings from mining could provide economic benefits for the region while helping prepare the post-mining landscape for reforestation. Regardless of the specific approach, recovery following ASGM is likely to continue to struggle without serious attention to geomorphic and hydrologic conditions.

Materials and methods

Field sites in the MdD region

The MdD region has a mean annual temperature of 25.4 °C and mean annual precipitation of 2120 mm (between 1980 and 2022)20. Precipitation varies seasonally: during the dry season (Jun–Sep), average precipitation decreases to <100 mm month−1, while the wettest months (Dec–Feb) average >300 mm month−1. The MdD features diverse ecosystems, including premontane forests, floodplain forests, upland forests, and a complex of wetlands among cochas (oxbow lakes) and aguajales (palm wetlands), the latter named for the dominance of the palm species Mauritia flexuosa33. This region also contains important protected natural areas, such as Bahuaja Sonene National Park, Manu National Park, Alto Purús National Park, and the Tambopata National Reserve (RNT)34. The RNT and its buffer zone are part of our study area, where a dominance of tree species can be found within families such as Fabaceae, Moraceae, Annonaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Myristicaceae, Arecaceae, and Malvaceae. Along with aguajal forests where Mauritia flexuosa predominates, these families represent the different types of forests characteristic of the region, from floodplains to upland forests35. Natural regeneration at all sites includes typical pioneer species for the region including Ochroma pyramidale, Apeiba sp., Cecropia sp., and species from the Poaceae family, such as Arundo sp.

Placer gold deposits in this region come from gold-rich rocks in the mountain headwaters from which ancient riverbeds carried gold-laden sediments and deposited them in the MdD basin. Modern gold mining in this region first began in the 1980s in the Huepetuhe area. It later expanded to other mining areas such as La Pampa around 2004, and further accelerated due to the increase in the price of gold in response to the 2008 global economic crisis36. From 1985 to 2010, an estimated 31,165 ha of mining-driven deforestation occurred in the MdD region5. Following construction on the Interoceanica Highway in 2006, a much wider area became readily accessible, increasing the extent of ASGM and subsequent deforestation to 64,586 ha from 2010 to 20175. As of 2017, ASGM was responsible for a total of 95,750 ha forest loss (Fig. 1a). Artificial wetlands produced by mining in MdD account for 8% of the degraded area associated with ASGM, and lake environments increased by 670% in heavily mined watersheds between the mid 1980s and mid 2010s13. Protected areas, such as the Tambopata National Reserve and buffer zone as well as indigenous communities, are increasingly under threat from illegal ASGM-related deforestation37,38. From 2021 to 2024, ~15% of all mining activity in the MdD has illegally taken place in native communities39.

Azul (suction mining)

The Azul region is located adjacent to Balata but inside the Tambopata National Reserve along the edge of the Rio Malinowski (Fig. 1c). Illegal mining in Azul occurred in 2014 and 2015 before being stopped by the army and park rangers, and it restarted in a limited area in December 2022. The region is actively being reforested by the Peruvian National Park agency, SERNANP.

Balata (suction mining)

Balata is located in the La Pampa region (Fig. 1c), one of the fastest growing and infamous mining areas in the MdD corridor4. While much of the mining in MdD is in the legal mining corridor, Balata is in the Tambopata Reserve Buffer Zone where mining is illegal. Mining began in La Pampa in 2004 and moved into the Balata area starting in 20125. Mining in Balata progressed rapidly until 2019 when the military intervention “Operation Mercury” stopped unauthorized mining40. However, after the national political unrest of late 2022–early 2023, mining returned despite continued military presence and was ongoing by the end of this study period (March 2024). There are sites of active reforestation near the military base in Balata and at a mining concession working with a local NGO, Center for Amazonian Scientific Innovation (CINCIA).

Cinco Rebeldes (excavation mining)

Cinco Rebeldes is a legal mining concession at the edge of the Huepetuhe mining region near the Pukiri River (Fig. 1b). The concession has been mined since 2000. The mined landscape consists of networks of shallow ponds (1.5–2 m) surrounded by regenerating vegetation and large, dominantly unvegetated tailing piles (Fig. 2b, d). At Cinco Rebeldes, the concession owner preserves the topsoil when excavating to promote natural regrowth post-mining (Fig. 2f). Tailing piles (~10–50 m high) remain largely untouched post-mining (Fig. 2b).

Los Amigos (control)

Los Amigos Biological Station (12°34′9″S 70°6′0.40″W) is a research station located on terra firme along the MdD river. This site was used as an additional undisturbed control site for hydrologic conductivity measurements in July 2023.

LiDAR acquisition and processing

Digital elevation models from uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) provide a way to extract high-resolution elevation data from remote regions like the MdD41,42. Elevations were determined from digital terrain models (DTMs) built from Lidar data collected using a DJI Zenmuse L1, comprised of a Livox lidar module, a 20 megapixel, 1” CMOS RGB camera, and a gyroscopic IMU, mounted on a DJI Matrice 300 RTK equipped with in-built real-time kinematic (RTK) GPS. The L1 Livox lidar uses a 905 nm laser with a scan rate of 80–240 kHz, supporting 3 returns and yielding a quoted at 3 cm accuracy at 100 m. Data were collected via 25 surveys conducted between July 9, 2023 and July 12, 2023 over Balata.

All surveys were conducted at a height of 120 m above the ground surface. Point densities for all UAV-based lidar scans ranged from 37.6 to 156.9 pt m−2 before ground classification and 1.9–23.9 pt m−2 after ground classification. IMU errors varied by flight and were typically in the range of 0.00019–0.0002 rad roll, 0.00018–0.00023 rad pitch, and 0.0007–0.0011 rad yaw, with nominal horizontal accuracy of ~5 cm.

RTK positioning was determined using an Emlid Reach RS2+ Multiband RTK GNSS receiver. During each data collection session, ~21 min of stationary data were collected, yielding a root-mean-squared-errors of ~0.0016 m in the X and Y, and 0.0003 in the Z.

Lidar data were combined with the corrected UAV GPS data to generate point clouds using the proprietary DJI Terra software. After export of the Terra point clouds as las files, ground points were classified through identification of Lidar last returns following point cloud cleaning in Agisoft Metashape. Ground-classified point clouds were used to build DTMs in Metashape. Vegetation canopy heights were determined by the difference between the DTM and the corresponding digital surface model derived from lidar first returns.

Mapping revegetation

Revegetation over the Balata area was mapped using data collected by high-resolution optoelectrical satellite imagery. A cloud-free Maxar WorldView-2 image of Balata (1.8 m ground sampling distance multispectral) provided baseline data from June 2019, soon after mining in this region was halted by Operation Mercury40. An overlapping Planet Labs SkySat image from July 2023 (0.81 m ground sampling distance multispectral; surface reflectance calibrated) provided data to capture revegetation over the 4 years following 2019. The two images were co-registered manually using 10 fixed points clearly identifiable in RGB images. The lidar dataset was co-registered with the images using distinct features visible in the RGB images corresponding to sharp elevation gradients identifiable in the lidar DTM, such as pond edges and islands. Co-registration was done in qGIS using the Georeferencer plug-in tool.

Water (primarily pond area) was identified in the 2019 imagery using a Normalized Difference Water Index optimized for WV-2 imagery, based on the “coastal” and “NIR-2” bands (bands 1 and 8, respectively)43. A threshold NDWI value of 0.1 was used to define a water mask, based on match to pond perimeters identifiable in optical images. Vegetated areas in 2019 and 2023 were determined using the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) with WV-2 Bands 7 (near infrared) and 5 (red), and SkySat bands 3 and 4, respectively. A threshold value of 0.25 was used to define vegetated pixels, based on match to optically visible vegetation which clearly contrasts with unvegetated mining areas. Areas of revegetation between 2019 and 2023 were determined by differencing the NDVI-derived vegetated area maps of these respective years.

Electrical resistivity data collection

Electrical resistivity allows observation of subsurface structure and moisture retention differences between primary forests, deforested sites and sites with natural regeneration, as well as differences between wet and dry seasons. We collected resistivity data over 46-m survey lengths to capture subsurface variation in water content at sites in both suction mining zones and the excavation mining concession (SI Table 2). Examples of electrical resistivity site photos are presented in SI Fig. 7. In the suction mining zones, we collected data at four sites in Azul and eight sites in Balata in July 2022 and five sites in Azul (four repeat) and five sites in Balata (four repeat) in March 2024 (SI Table 2). The Balata sites that were not repeated from 2022 were either inaccessible (LP-3, LP-4, LP-5) or heavily changed from mining activity (LP-2), and a new similar site was selected (LP-9). In the excavation mining concession at Huepetuhe, we collected data at five sites in 2022 and 2024. Sites at all three locations were selected to cover the range of forest types: primary forest, natural regeneration in a deforested mining zone, and deforested.

We used a Syscal Pro electrical resistivity meter from Iris Instruments and a combined Dipole-Dipole and Wenner Schlumberger array with 2-m spacing for high signal-to-noise ratio and lateral and vertical resolution of the near surface44. Reciprocal measurements were also made at 1⁄3 density for error quantification45,46,47. While ideally contact resistances should be as low as possible, in the extremely dry sands of the ASGM regions it could be extremely difficult to reduce contact resistance. Contact resistances often started between 100 and 500 kΩ, and by utilizing clay-rich cat litter and salt water, we managed to reduce them to a threshold of under 50 kΩ, often between 20 and 40 kΩ (Supplementary Table 1). High contact resistances were not an issue in the primary forest, where clay-rich soils had resistances between 0.12 and 15 kΩ generally.

Electrical resistivity data processing and inversions

Initial measurements were filtered to remove negative apparent resistivity measurements and erroneously high data points from both normal and reciprocal surveys, leaving >90% of data for each inversion model. We inverted 2D resistivity models using the open-source software ResiPy in the Python API48. Inversion models were produced with a regularized inversion with linear filtering and weight parameters a and b, which were derived from a power-law error model where absolute reciprocal error is a function of resistance. R-squared values of the error reciprocal model are reported in SI Table 2 for all inversions. We used a quadrilateral mesh given the limited topographic changes across survey lines. A sensitivity map scaled by cell area, produced during the inversion process, was used to extract points that are not artifacts of the inversion model but represent the field results, using a threshold of >0.001. Inversion RMS misfit and inversion iterations to converge are reported in SI Table 2. Examples of percent error distributions are presented is SI Fig. 8.

Hydraulic conductivity

A total of 54 hydraulic conductivity experiments were performed at 40 sites across the study areas during both the dry season (July 2023) and wet season (March 2024), with repeat measurements taken at 14 of those sites (SI Table 3). Sites were chosen across a gradient of vegetation and soil types, typically near ERI survey sites: primary forests with clay-rich soils, post-mining new-growth forests characterized by organic material overlying structured sandy soil, and deforested mining regions dominated by unstructured sands. For hydraulic measurements, soil character (and general classification as clay vs. clay-loam vs. sand) was assessed visually in relation to data from prior studies in the region that measured grain size distributions (SI Table 1).

The Guelph Permeameter (GP) method (Soil Moisture Corp., Santa Barbara, CA) was used to estimate in-situ field-saturated hydraulic conductivities (Kfs) at the study sites (SI Table 4)49. At each site, we augured a small borehole into the vadose zone, which was ponded at a constant head for the duration of the experiment38. The GP reservoir level was measured at a consistent time interval until a steady state of fall was achieved, after which the following equation was used to calculate Kfs (cm s−1)50:

where C (dimensionless) is the shape factor, Qs (cm3 s−1) is the steady-state discharge, H (cm) is the wellhead, \(a\) (cm) is the well radius, and \({\alpha }^{* }\) (cm−1) is the soil capillarity parameter. C and \({\alpha }^{* }\) were chosen for each site based on their soil categorization51,52, while Qs was calculated as:

where Rs (cm s−1) is the steady-state rate of fall in the reservoir over the observed time interval, and A (cm2) is the reservoir cross-sectional area (35.22 cm2).

Paired unsaturated hydraulic conductivity (k) values were obtained using a mini disk tension infiltrometer (METER Group, USA)53. Measurements of reservoir volume were recorded at a constant time interval when possible, after which the cumulative infiltration (I) over time was fit to the following function40:

C1 (m s−1) and C2 (m s−0.5) are parameters of hydraulic conductivity and soil sorptivity respectively, and the former was used to calculate k using the following equations:

and

where n and \(\alpha\) are the dimensionless van Genuchten parameters54 chosen according to soil texture class (assessed as described above), ho (cm) is the suction applied to the surface (1 cm), and ro (cm) is the apparatus radius (2.25 cm).

Temperature, soil moisture, and water level sensors

We measured in situ soil temperature and volumetric moisture content using a TEROS-12 sensor (Meter) at each hydraulic conductivity site. Additionally, seven TMS-4 dataloggers55 (TOMST, Czech Republic) were deployed across the suction mining study region: four in deforested sand sites, one in a deforested sand site adjacent to a pond and two at primary forest sites (one in clay-rich soil, one in the organic layer) for continuous time series measurement at −6 cm depth and temperature at +15 cm, +2 cm and −6 cm depths (SI Table 5). In the deforested sites, the data loggers were tucked under shrubs to avoid detection and theft, which was an issue working in this region. For time series measurements, soil moisture was converted from “counts” (the data output from the logger) to volumetric water content using the TMS software and soil composition (assessed as described above). Soil moisture drying rates were computed for each site in Python by first smoothing the soil moisture data using a rolling window size of 100. We then found peaks in soil moisture indicative of rain events using the scipy function find_peaks with a distance = 50 sampling points. The subsequent end to a drying period was found using the scipy function argrelextrema, which is used to find the following low extreme after a peak index. We then computed drying rates using the difference in soil moisture between the peak and subsequent soil moisture low. We measured changes in pond water level height over time using a Hobo Level Logger (UL20L) deployed in the pond directly next to the ERI site LP-8. We also deployed a Solinst Barologger nearby to correct for changes in atmospheric pressure.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data used in this manuscript are available in the following CUAHSI Hydroshare repository with the permanent https://doi.org/10.4211/hs.05a0490e971f491fa64c62cbde499a6a. These data are shared under the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY.

Code availability

All code used in this work comes from previously developed, open-source code as cited in the text. Please refer to the original code for latest version and implementation.

References

Groombridge, B. & Jenkins, M. World Atlas of Biodiversity: Earth’s Living Resources in the 21st Century (University of California Press, 2002).

Marengo, J. A. et al. Changes in climate and land use over the Amazon region: current and future variability and trends. Front. Earth Sci. 6, 228 (2018).

Nobre, C. A. et al. Land-use and climate change risks in the Amazon and the need of a novel sustainable development paradigm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10759–10768 (2016).

Asner, G. P. & Tupayachi, R. Accelerated losses of protected forests from gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 094004 (2017).

Caballero Espejo, J. et al. Deforestation and forest degradation due to gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon: a 34-year perspective. Remote Sens. 10, 1903 (2018).

Ngom, N. M. et al. Artisanal exploitation of mineral resources: remote sensing observations of environmental consequences, social and ethical aspects. Surv. Geophys. 44, 225–247 (2023).

Sheoran, V., Sheoran, A. & Poonia, P. Soil reclamation of abandoned mine land by revegetation: a review. Int. J. Soil Sediment Water 3, 13 (2010).

Timsina, S. et al. Tropical surface gold mining: a review of ecological impacts and restoration strategies. Land Degrad. Dev. 33, 3661–3674 (2022).

Román-Dañobeytia, F. et al. Reforestation with four native tree species after abandoned gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon. Ecol. Eng. 85, 39–46 (2015).

Lobo, F., Costa, M., Novo, E. & Telmer, K. Distribution of artisanal and small-scale gold mining in the Tapajós River Basin (Brazilian Amazon) over the past 40 Years and relationship with water siltation. Remote Sens. 8, 579 (2016).

Dethier, E. N. et al. A global rise in alluvial mining increases sediment load in tropical rivers. Nature 620, 787–793 (2023).

Martinelli, L. A., Ferreira, J. R., Forsberg, B. R. & Victoria, R. L. Mercury contamination in the Amazon: a gold rush consequence. Ambio 17, 252–254 (1988).

Gerson, J. R. et al. Artificial lake expansion amplifies mercury pollution from gold mining. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd4953 (2020).

Cortés-McPherson, D. Digging into the Mining Subculture: The Dynamics of Trafficking in Persons in the Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining of Peru’s Madre de Dios. in Illegal Mining: Organized Crime, Corruption, and Ecocide in a Resource-Scarce World (eds Zabyelina, Y. & van Uhm, D.) 359–386 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46327-4_13.

Cavazuti, L., McFadden, C., Monahan, K., Salam, Y. & Schapiro, R. Paradise Lost: Inside Peru’s emergency zone. NBC News (2022).

Seccatore, J., Veiga, M., Origliasso, C., Marin, T. & De Tomi, G. An estimation of the artisanal small-scale production of gold in the world. Sci. Total Environ. 496, 662–667 (2014).

Achina-Obeng, R. & Aram, S. A. Informal artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) in Ghana: assessing environmental impacts, reasons for engagement, and mitigation strategies. Resour. Policy 78, 102907 (2022).

Woodbury, D. J. et al. Filling a void: analysis of early tropical soil and vegetative recovery under leguminous, post-coal mine reforestation plantations in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land Degrad. Dev. 31, 473–487 (2020).

Kalamandeen, M. et al. Limited biomass recovery from gold mining in Amazonian forests. J. Appl. Ecol. 57, 1730–1740 (2020).

Garate-Quispe, J. et al. Influence of distance from forest edges on spontaneous vegetation succession following small-scale gold mining in the southeast Peruvian Amazon. Diversity 15, 793 (2023).

Chambi-Legoas, R. et al. Natural regeneration after gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon: implications for restoration of tropical forests. Front. For. Glob. Change 4, 65 (2021).

Binley, A. et al. The emergence of hydrogeophysics for improved understanding of subsurface processes over multiple scales. Water Resour. Res. 51, 3837–3866 (2015).

Lichner, L., Orfánus, T., Nováková, K., Šír, M. & Tesař, M. The impact of vegetation on hydraulic conductivity of sandy soil. Soil and Water Res., 2, 59–66 (2007).

Garate-Quispe, J. et al. Resilience of aboveground biomass of secondary forests following the abandonment of gold mining activity in the Southeastern Peruvian Amazon. Diversity 16, 233 (2024).

Dürr, C., Dickie, J. B., Yang, X.-Y. & Pritchard, H. W. Ranges of critical temperature and water potential values for the germination of species worldwide: contribution to a seed trait database. Agric. For. Meteorol. 200, 222–232 (2015).

Slot, M. et al. Leaf heat tolerance of 147 tropical forest species varies with elevation and leaf functional traits, but not with phylogeny. Plant Cell Environ. 44, 2414–2427 (2021).

Yaffar, D. et al. Tropical root responses to global changes: a synthesis. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17420 (2024).

Román-Dañobeytia, F. et al. Survival and early growth of 51 tropical tree species in areas degraded by artisanal gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon. Ecol. Eng. 159, 106097 (2021).

Alarcón-Aguirre, G. et al. Vegetation dynamics in lands degraded by gold mining in the southeastern Peruvian Amazon. Trees For. People 11, 100369 (2023).

Velásquez Ramírez, M. G. et al. Mercury in soils impacted by alluvial gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon. J. Environ. Manag. 288, 112364 (2021).

Holgerson, M. A., et al. Classifying mixing regimes in ponds and shallow lakes. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2022WR032522 (2022).

U. N. Environment Programme. Sand and Sustainability: 10 Strategic Recommendations to Avert a Crisis | UNEP - UN Environment Programme. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/sand-and-sustainability-10-strategic-recommendations-avert-crisis (2022).

USAID. Tejida y entrelazada: La compleja cadena de valor del sector minero en Madre de Dios| Proyecto Prevenir de USAID. (2021).

MINAN. Madre de Dios: estadísticas ambientales, Diciembre 2019 | SINIA Ministerio del Ambiente-MINAN. https://sinia.minam.gob.pe/documentos/madre-dios-estadisticas-ambientales-diciembre-2019 (2019).

Martínez-Sovero, G. A. et al. Fenología de las especies arbóreas de la Reserva Nacional Tambopata. Perú. Rev. Mex. de Cienc. For. 12, 107–127 (2021).

Swenson, J. J., Carter, C. E., Domec, J.-C. & Delgado, C. I. Gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon: global prices, deforestation, and mercury imports. PLoS ONE 6, e18875 (2011).

Scullion, J. J., Vogt, K. A., Sienkiewicz, A., Gmur, S. J. & Trujillo, C. Assessing the influence of land-cover change and conflicting land-use authorizations on ecosystem conversion on the forest frontier of Madre de Dios, Peru. Biol. Conserv. 171, 247–258 (2014).

Nicolau, A. P., Herndon, K., Flores-Anderson, A. & Griffin, R. A spatial pattern analysis of forest loss in the Madre de Dios region, Peru. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 124045 (2019).

MAAP #208: Gold mining in the southern Peruvian Amazon, summary 2021-2024. MAAP https://www.maaproject.org/2024/mining-peru/ (2024).

Dethier, E. N. et al. Operation mercury: impacts of national-level armed forces intervention and anticorruption strategy on artisanal gold mining and water quality in the Peruvian Amazon. Conserv. Lett. 16, e12978 (2023).

Martin, H. K., Edmonds, D. A., Yanites, B. J. & Niemi, N. A. Quantifying landscape change following catastrophic dam failures in Edenville and Sanford, Michigan, USA. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 49, 2767–2778 (2024).

MacDonell, C. J., Williams, R. D., Maniatis, G., Roberts, K. & Naylor, M. Consumer-grade UAV solid-state LiDAR accurately quantifies topography in a vegetated fluvial environment. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 48, 2211–2229 (2023).

Xie, C., Huang, X., Zeng, W. & Fang, X. A novel water index for urban high-resolution eight-band WorldView-2 imagery. Int. J. Digit. Earth 9, 925–941 (2016).

Heenan, J. et al. Electrical resistivity imaging for long-term autonomous monitoring of hydrocarbon degradation: Lessons from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Geophysics 80, B1–B11, https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2013-0468.1 (2014).

Slater, L., Binley, A. M., Daily, W. & Johnson, R. Cross-hole electrical imaging of a controlled saline tracer injection. J. Appl. Geophys. 44, 85–102 (2000).

Koestel, J., Kemna, A., Javaux, M., Binley, A. & Vereecken, H. Quantitative imaging of solute transport in an unsaturated and undisturbed soil monolith with 3-D ERT and TDR. Water Resour. Res. 44, 12 (2008).

Binley, A. & Kemna, A. DC resistivity and induced polarization methods. In Hydrogeophysics 129–156 (Springer, 2005).

Blanchy, G., Saneiyan, S., Boyd, J., McLachlan, P. & Binley, A. ResIPy, an intuitive open source software for complex geoelectrical inversion/modeling. Comput. Geosci. 137, 104423 (2020).

Salverda, A. P. & Dane, J. H. An examination of the Guelph permeameter for measuring the soil’s hydraulic properties. Geoderma 57, 405–421 (1993).

Bagarello, V., Iovino, M. & Reynolds, W. D. Measuring hydraulic conductivity in a cracking clay soil using the Guelph permeameter. Trans. ASAE 42, 957–964 (1999).

Zhang, R. Determination of soil sorptivity and hydraulic conductivity from the disk infiltrometer. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 61, 1024–1030 (1997).

Reynolds, W. D. & Elrick, D. E. A method for simultaneous in situ measurement in the vadose zone of field-saturated hydraulic conductivity, sorptivity and the conductivity-pressure head relationship. Groundw. Monit. Remediat.6, 84–95 (1986).

Dohnal, M., Dusek, J. & Vogel, T. Improving hydraulic conductivity estimates from minidisk infiltrometer measurements for soils with wide pore-size distributions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 74, 804–811 (2010).

Carsel, R. F. & Parrish, R. S. Developing joint probability distributions of soil water retention characteristics. Water Resour. Res. 24, 755–769 (1988).

Wild, J. et al. Climate at ecologically relevant scales: a new temperature and soil moisture logger for long-term microclimate measurement. Agric. For. Meteorol. 268, 40–47 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Plunkett, F. Macedo, J. M. Cadillo, and Y. Figueroa for field assistance. We are also grateful to C. Vega, J. Araujo, R. Garcia, M. Silman, C. Ascorra, and L. Fernandez at the Centro de Innovación Científica Amazónica (CINCIA) for their logistical support, insight, and assistance with field locations. We thank SERFOR and SERNANP for permitting and access to field sites, and SERNANP for additional logistical support in the field, as well as Sr. Barrios, J. Barrios, and the team at Cinco Rebeldes for access and fieldwork assistance. We extend special thanks to the people in MdD who supported transportation, lodging, and logistics throughout the project. This research was supported by the Rolex-National Geographic and Rolex Perpetual Planet Amazon Expedition. Access to SkySat imagery was provided through a collaboration between Arizona State University and Planet Labs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.A., A.J.W., H.C.Q., J.A.A.; Fieldwork: A.A., A.J.W., S.R., D.C.R., H.C.Q., J.A.A.; data analysis: A.A. (electrical resistivity, remote sensing), A.J.W. (remote sensing), C.C. (remote sensing), S.R. (hydraulic conductivity). Writing: A.A. with contribution from all authors. Editing: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks John Webb and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Joshua Dean and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Atwood, A., Ramesh, S., Amaya, J.A. et al. Landscape controls on water availability limit revegetation after artisanal gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon. Commun Earth Environ 6, 419 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02332-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02332-y

This article is cited by

-

Environmental impacts of toxic elements on crop-grazing soils in areas surrounding artisanal mining in the Brazilian Amazon

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2026)