Abstract

Soil erosion frequently occurs on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, including freeze-thaw, water, and wind erosion, seriously threatening ecological security and human well-being. However, comprehensive research on these three types of soil erosion in this region is still lacking so far. Here, we assessed the spatial-temporal patterns of freeze-thaw, water, and wind erosion on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau for the historical period (2001–2020) and the future period (2021–2100), based on conceptual erosion models, to fill this critical gap. We found that freeze-thaw, water, and wind erosion declined from 2001 to 2020. In contrast, freeze-thaw and water erosion are projected to increase significantly from 2021 to 2100, while wind erosion is expected to decrease markedly. Additionally, the area experiencing moderate and severe erosion is forecasted to expand under future climate scenarios. This research provides valuable scientific guidance for the planning and management of soil erosion prevention and control on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil, as the keystone of terrestrial ecosystems, underpins the sustainability of human civilization and the natural environment. It not only controls geochemical, hydrological, and biological cycles, but also provides essential ecosystem services to ensure human needs, such as provisioning (food, fresh water, raw materials, medicinal plants), regulating (clean air, flood control, water purification), supporting (primary productivity, soil formation, genetic resources), and cultural (aesthetic experience, recreation, heritage preservation) services1,2,3,4. Consequently, 13 of the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals are directly or indirectly linked to soil health5. Soil erosion is a natural geologic process that shapes the Earth’s surface through the actions of mass movement, wind, and water6,7. The Global Assessment of Soil Degradation Survey identified soil erosion as the primary cause of soil degradation worldwide1,3,6,7,8,9. Among the key drivers, water erosion (WAE) and wind erosion (WIE) affect 28% and 56% of the total degraded land, respectively10. Freeze-thaw erosion (FTE), the third most important form of soil erosion, impacts ~24% of the global land area and 55% of the total land area in the Northern Hemisphere11,12. Soil erosion can cause remarkable deterioration in soil quality and trigger a series of cascading negative effects such as declines in productivity, carbon storage, nutrient retention, and biodiversity, which can disrupt ecosystem balance4,13,14. In addition, soil erosion can lead to natural disasters such as floods, mudslides, sandstorms, siltation, and eutrophication of waterways, all of which pose serious threats to urban safety, human survival, and sustainable development1,4. Addressing soil erosion has become a priority in international policy frameworks, with the United Nations identifying it as a major global challenge of the 21st century4. Recent, Sustainable Development Goals reports have proposed the urgency of combating soil degradation, setting an ambitious target of achieving zero net soil degradation by 20303,6.

Soil erosion is a complex process shaped by a combination of natural factors and human activities4,15. In recent decades, climate change and human activities have played a critical role in accelerating soil erosion globally1,6,7. According to the Global Soil Partnership report, approximately seventy-five billion tonnes of soil are lost annually from arable land, incurring financial losses exceeding about four hundred billion dollars in agricultural production each year1,6,16,17. Alarmingly, critical knowledge gaps persist regarding soil erosion dynamics in high-altitude regions, including the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (QTP), as highlighted in the Sixth Assessment Report of the IPCC18. The QTP, the highest plateau in the world and an extensive cryospheric region19, features a unique climate, variable terrain, and complex substratum conditions that collectively drive diverse soil erosion processes, including FTE, WAE, and WIE. The QTP also contains the largest and most extensive area of frozen ground at low and middle altitudes globally, covering ~2.52 × 106 km2, and undergoes frequent freeze-thaw processes20,21,22. Specifically, temperature fluctuations between winter and spring, as well as between day and night, trigger repeated freeze-thaw cycles23. These processes disrupt the bonding and cementation among soil particles, alter soil stability, reduce soil strength, and diminish erosion resistance, thereby increasing soil detachment capacity24,25. Detached soil particles then become susceptible to transport by erosive agents such as wind and water, eventually resulting in soil erosion23,26,27. Additionally, the QTP is highly prone to desertification due to insufficient precipitation and frequent strong winds, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions, making it an important source of dust and contributing an average of 16% of the sand transported to East Asia28. The QTP is considered a major contributor to WAE worldwide18,29. Due to its young geological structure, poor soil quality, and slow soil formation, the region has a very limited capacity to recover from erosion29. Notably, the QTP serves as the source of major Asian rivers, a habitat for endemic species, and home to premium pastures, providing essential ecosystem services such as freshwater, food, carbon sequestration, oxygen release, nutrient cycling, cultural inheritance, and ecotourism at local, regional, and even global scales28,30. However, accelerating soil erosion in this region poses a substantial threat to the sustained supply of these ecosystem services.

Due to its high altitude with pronounced thermal and dynamic impacts, the QTP is particularly sensitive to global climate change, making it a critical indicator region for global climate change31. Since the 1980s, warming and wetting trends have been observed on the QTP18,32. Meanwhile, human activities, such as overgrazing and urbanization, have intensified in this region29,32,33. The interaction between climate change and human activities has led to about 75% of the QTP being recognized as an ecologically fragile area, experiencing moderate to severe degradation34. To restore the QTP’s degraded alpine ecosystem, a series of policy measures and government-led programs have been implemented, such as ecological restoration projects, grazing exclusion, the establishment of nature reserves, and forage production-based grazing and settlement, especially after 200032,35. The combined effects of climate warming and wetting, along with these measures and programs, have promoted vegetation greening, which in turn reduces soil erosion33,36. In the future, continued improvements in vegetation are expected to help control soil erosion18. Conversely, ongoing warming is expected to further accelerate surface erosion by enhancing freeze-thaw processes that release loose and erodible materials23. Additionally, the warming atmosphere, with its increased capacity to retain moisture, is forecasted to lead to more extreme rainfall events, intensifying the hydrological cycle and causing severe WAE29. Consequently, changes in climate and vegetation have heightened the uncertainty of soil erosion dynamics.

To systematically capture the status of soil erosion research on the QTP, we analyzed relevant articles published between January 2000 and September 2024 across multiple databases including Web of Science, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure using keywords such as “soil erosion on the QTP” and “land degradation on the QTP”. Among the collected articles, 91 were related to WAE, while only 23 and 35 focused on FTE and WIE, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The number of WAE articles gradually increased from 2001 to 2024, highlighting the dominance of WAE as a research hotspot, whereas FTE and WIE have not received sufficient attention (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Meanwhile, previous studies have mainly concentrated on a single type of soil erosion, with a predominant focus on local areas such as the Three-River Headwaters Region, Qilian Mountains, and Tibet (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Notably, only three articles conducted comprehensive assessments encompassing FTE, WAE, and WIE, all of which were situated in the Three-River Headwaters Region. Furthermore, most studies have primarily focused on changes in soil erosion during the historical period, with few considering soil erosion under future climate scenarios (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Given this, we found that comprehensive research on the spatial-temporal patterns of FTE, WAE, and WIE across the entire QTP for both historical and future periods has not yet been reported. Additionally, climate change and vegetation improvements could lead to substantial changes in soil erosion on the QTP. Previous studies have reported that warming and wetting trends are expected to continue in the future37, potentially accelerating WAE. However, the effects of these climate change trends and vegetation dynamics on FTE and WIE have not been reported to date. Assessing the risk of soil erosion is essential for clarifying regional soil erosion patterns and for implementing effective soil protection and control measures. Nevertheless, the risk of soil erosion on the QTP remains unclear, particularly under various climate scenarios. To address these issues, we employed three conceptual erosion models, including the Freeze-thaw Erosion Equation, the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE), and the Revised Wind Erosion Equation (RWEQ) to assess FTE, WAE, and WIE, respectively. This study defines the historical period as 2001–2020 and the future period as 2021–2100. We considered four Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenarios from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6), namely SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5, along with five global climate models (GCMs), i.e., BCC-CSM2-MR, MRI-ESM2-0, CESM2, IPSL-CM6A-LR, and MPI-ESM1-2-HR. The objectives of this study are to: (1) analyze the spatial-temporal patterns of FTE, WAE, and WIE on the QTP for the historical period and the future period under four SSP scenarios; (2) explore the impacts of climate change and vegetation dynamics on soil erosion variations; (3) delineate the spatial distribution zones of the three types of soil erosion; (4) assess soil erosion risk and identify priority areas for future erosion control. This research fills critical knowledge gaps, providing valuable scientific guidance for the planning and management of soil erosion prevention and control on the QTP.

Results

Spatial-temporal patterns of soil erosion

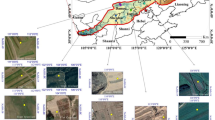

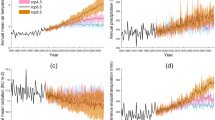

During the historical period, areas with high FTE values were primarily concentrated in the Yarlung Zangbo River Basin, Hengduan Mountains, and Qilian Mountains (Fig. 1a). The intensity of WAE gradually increased from northwest to southeast on the QTP, whereas WIE exhibited the opposite trend (Fig. 1b, c). From 2001 to 2020, FTE, WAE, and WIE showed decreasing trends, with respective rates of 1.38 × 10−5 a−1, 0.03 t ha−1 a−1, and 0.04 kg m−2 a−1 (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2a–c). Notably, FTE first decreased at a rate of 1.10 × 10−3 a−1 and then increased at a rate of 3.40 × 10−3 a−1 (P > 0.05), with the trend break occurring in 2013. Additionally, FTE increased significantly in the northwest, covering ~16.9% of the study area, whereas about 6.5% of the study area, mainly in the central part of the QTP, experienced significant decreases (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Regarding WAE, significant decreases dominated spatially, particularly in the northwest, where the area experiencing significant decreases was 12.27 times larger than that with significant increases (Supplementary Fig. 2b). In contrast, areas with significant increases in WIE were mainly located in the Qaidam Basin, Qilian Mountains, and western QTP, accounting for 13.6% of the study area, while those with significant decreases were concentrated in the southeast, representing 25.8% (Supplementary Fig. 2c).

Spatial patterns of (a) freeze-thaw erosion, (b) water erosion, and (c) wind erosion for the historical period. Spatial distributions of soil erosion under four Shared Socioeconomic Pathway scenarios: d freeze-thaw erosion, e water erosion, and f wind erosion under SSP1-2.6; g freeze-thaw erosion, h water erosion, and i wind erosion under SSP2-4.5; j freeze-thaw erosion, k water erosion, and l wind erosion under SSP3-7.0; m freeze-thaw erosion, n water erosion, and o wind erosion under SSP5-8.5.

Temporal changes of (a) freeze-thaw eroison, (b) water eroison, and (c) wind erosion from 2001 to 2020. Temporal dynamics of soil erosion during 2021–2100 under four Shared Socioeconomic Pathway scenarios: d freeze-thaw eroison, e water eroison, and f wind erosion under SSP1-2.6; g freeze-thaw eroison, h water eroison, and i wind erosion under SSP2-4.5; j freeze-thaw eroison, k water eroison, and l wind erosion under SSP3-7.0; m freeze-thaw eroison, n water eroison, and o wind erosion under SSP5-8.5. Statistical significance is marked with the asterisk (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). The shaded area represents the 95.0% confidence interval of the equation.

The spatial distributions of the three types of soil erosion on the QTP under four SSP scenarios are generally consistent with those observed during the historical period (Fig. 1d–o). FTE is projected to increase significantly under all SSP scenarios from SSP1-2.6 to SSP5-8.5 at rates of 1.39 × 10−4, 3.13 × 10−4, 3.88 × 10−4, and 5.13 × 10−4 a−1 (P < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 2d, g, j, m). The areas with significant increases in FTE are largest under SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5, covering 66.4% and 66.8% of the study area, respectively, followed by SSP2-4.5 (~22.3%) and SSP5-8.5 (~31.3%) (Supplementary Fig. 2d, g, j, m). WAE is also expected to increase significantly under future scenarios, with the highest rate under SSP5-8.5 (0.041 t ha−1 a−1), followed by SSP3-7.0 (0.028 t ha−1 a−1), SSP2-4.5 (0.022 t ha−1 a−1), and the lowest rate under SSP1-2.6 (0.011 t ha−1 a−1) (Fig. 2e, h, k, n). The spatial change in future WAE is characterized by a significant increase, with the areas of significant increase gradually expanding from southeast to northwest from SSP1-2.6 (~31.1%) to SSP5-8.5 (~90.6%) (Supplementary Fig. 2e, h, k, n). Conversely, WIE is predicted to decrease markedly under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5, with rates of 0.003, 0.007, 0.011, and 0.012 kg m−2 a−1 (P < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 2f, i, l, o). Under these scenarios, from SSP1-2.6 to SSP5-8.5, areas with significant decreases in WIE gradually expand from the Hengduan Mountains to the Qaidam Basin and Chang Tang Plateau, covering about 14.5%, 27.4%, 40.5%, and 44.5% of the study area, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2f, i, l, o). In contrast, significant increases in WIE are primarily concentrated in the central region, covering ~35.4%, 34.9%, 17.4%, and 36.9% of the study area under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5, respectively.

Spatial-temporal patterns of influencing factors

Key factors influencing FTE included slope, fractional vegetation cover, annual precipitation, air annual temperature range, and aspect (Supplementary Fig. 3a–e). The spatial distributions of slope, fractional vegetation cover, and annual precipitation increased from northwest to southeast, while the air annual temperature range increased from south to north. The QTP is characterized by complex topography, with steep slopes and a relatively uniform distribution of aspects. Random forest analysis revealed that these factors significantly influenced FTE, with their relative importance ranked from highest to lowest as slope > fractional vegetation cover > aspect > air annual temperature range > annual precipitation (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Collectively, these factors explained 91.36% of the FTE variation (P < 0.01). Furthermore, the key factors driving changes in WAE were identified as rainfall erosivity (R), soil erodibility, slope length-steepness, land cover and management (C), and support practices. Among these, the slope length-steepness factor, R factor, and support practices factor increased from northwest to southeast, while the C factor exhibited the opposite pattern (Supplementary Fig. 3f, g, i, j). Areas with low soil erodibility values were primarily distributed in the Qaidam Basin (Supplementary Fig. 3h). In terms of relative importance, the factors ranked in ascending order as slope length-steepness factor, C factor, soil erodibility factor, R factor, and support practices factor, collectively explaining 86.19% of the variation in WAE (Supplementary Fig. 4b). In contrast, WIE was markedly influenced by the weather factor (WF), soil erodible fraction, soil crust factor, surface roughness factor, and combined vegetation factor (COG) (P < 0.01), all of which exhibited similar spatial patterns, characterized by an increase from southeast to northwest (Supplementary Fig. 3k–o). The relative importance of these factors was ranked in ascending order as WF factor, soil crust factor, soil erodible fraction, COG factor, and surface roughness factor, collectively explaining 91.23% of the variation in WIE (Supplementary Fig. 4c).

Over the past two decades, annual precipitation and the WF factor showed decreasing trends, with rates of 0.28 mm a−1 and 0.27 kg m−1 a−1 (P > 0.05), respectively, while the R factor increased significantly at a rate of 1.53 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 a−1 (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). Areas with significant decreases in annual precipitation were concentrated in the central regions, accounting for about 11.19% of the study area (Supplementary Fig. 6a), whereas substantial increases in the R factor were observed in the eastern and western regions, encompassing 33.2% (Supplementary Fig. 6b). The WF factor exhibited significant increases in 25.1% of the study area, mainly in the north, while 28.0% of the area, primarily in the south, experienced significant decreases (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Fractional vegetation cover increased obviously at a rate of 0.01% a−1 (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Conversely, the C and COG factors decreased significantly at rates of 0.01 a−1 and 0.13 a−1 (P < 0.001), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7b, c). Areas with significant increases in fractional vegetation cover were mainly located in the eastern and northern regions, accounting for 22.6% of the study area. In contrast, areas with significant decreases, accounting for 10.6% of the study area, were primarily found in the Chang Tang Plateau (Supplementary Fig. 8a). At the grid scale, the C and COG factors were predominantly characterized by significant decreases (Supplementary Fig. 8b, c).

The spatial distributions of annual precipitation, the R factor, the WF factor, fractional vegetation cover, the C factor, and the COG factor on the QTP under four SSP scenarios are generally consistent with the patterns observed during the historical period (Supplementary Fig. 9, 10). Annual precipitation and the R factor are projected to increase significantly under future scenarios, with the rate of increase from highest to lowest being SSP5-8.5, SSP3-7.0, SSP2-4.5, and SSP1-2.6 (P < 0.001), whereas the WF factor is expected to exhibit the opposite pattern (Supplementary Fig. 5d–o). The areas with significant increases in both annual precipitation and the R factor are expected to gradually expand from southeast to northwest under four scenarios from SSP1-2.6 to SSP5-8.5 (Supplementary Fig. 6d, g, j, m, e, h, k, n). Conversely, the area percentages of significant decreases in the WF factor under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5 show a consistent increase, ranging from 25.1% to 44.4%, as areas with significant decreases gradually expand from the Hengduan Mountains to the Qaidam Basin and Chang Tang Plateau (Supplementary Fig. 6f, i, l, o). In addition, fractional vegetation cover increases observably under SSP1-2.6 (6.40 × 10−4% a−1), SSP2-4.5 (3.08 × 10−3 % a−1), and SSP3-7.0 (4.42 × 10−4 % a−1), while it decreases markedly under SSP5-8.5 (1.47 × 10−3% a−1) (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 7d, g, j, m). Comparing the four scenarios, the area percentages of significant increases and decreases in fractional vegetation cover are nearly equal under SSP1-2.6 (Supplementary Fig. 8d). Under SSP2-4.5 and SSP3-7.0, the areas with significant increases are 1.81 and 1.08 times larger than those with significant decreases, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8g, j). However, under SSP5-8.5, the area with significant decreases is 1.58 times greater than that with significant increases (Supplementary Fig. 8m). Notably, the C factor shows no significant changes under the various SSP scenarios (P > 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 7e, h, k, n), with the percentages of significant changes over time from SSP1-2.6 to SSP5-8.5 being only 7.9%, 9.6%, 9.3%, and 14.5%, respectively, and scattered throughout the study area (Supplementary Fig. 8e, h, k, n). Moreover, the COG factor decreases significantly under SSP1-2.6 and SSP2-4.5, at rates of 1.35 × 10−5 and 6.62 × 10−5 a−1, respectively (P < 0.001), while it increases markedly under SSP5-8.5 at a rate of 2.02 × 10−5 a−1 (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 7f, i, o). In contrast, the COG factor shows a decreasing trend under SSP3-7.0 (P > 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 7l). The area percentages showing significant decreases in the COG factor are greater than those with significant increases across all SSP scenarios (Supplementary Fig. 8f, i, l, o).

Drivers of soil erosion variation

At the spatial scale, the variations in FTE, WAE, and WIE for the historical and future periods are driven by climate change and vegetation dynamics (Supplementary Fig. 11). In contrast, temporal changes in FTE and WIE during these two periods were primarily influenced by climate change rather than vegetation dynamics (Fig. 3). Specifically, FTE showed a significant positive correlation with annual precipitation, while WIE exhibited a significant positive correlation with the WF factor in the historical period; similar results were observed across all scenarios. In contrast, variations in WAE were influenced by both R and C factors throughout the study period, especially under four SSP scenarios.

FTE freeze-thaw erosion, WAE water erosion, WIE wind erosion, AP annual precipitation, FVC fractional vegetation cover, R rainfall erosivity factor, C land cover and management factor, WF weather factor, COG combined vegetation factor. Statistical significance is marked with the asterisk (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Spatial-temporal pattern of soil erosion zone

During the historical period, the QTP was dominated by the FTE zone, while the WIE zone was mainly distributed in the Qaidam Basin and the southern foothills of the Eastern Himalayas (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). In contrast, the WAE zone was primarily located along the eastern and southern edges of the QTP. Under all future scenarios, the spatial patterns of soil erosion zones remain consistent with those during the historical period (Supplementary Fig. 12c–f). The FTE zone occupied the largest area, ranging from 85.5% to 87.5%, whereas the WAE and WIE zones accounted for smaller proportions, comprising 5.3%–6.8% and 6.9%–9.2% of the total area, respectively (Fig. 4a–e).

Area percentages of the three types of soil erosion for the historical period (a) and the future period under four scenarios: b SSP1-2.6, c SSP2-4.5, d SSP3-7.0, and e SSP5-8.5; area conversions among the three types of soil erosion for the historical period (f) and under different future scenarios: g SSP1-2.6, h SSP2−4.5, i SSP3-7.0, and j SSP5-8.5. FTE freeze-thaw erosion, WAE water erosion, WIE wind erosion.

From 2001 to 2020, the areas of the FTE and WAE zones expanded by 2.57 × 104 and 4.30 × 104 km2, respectively, primarily due to transitions from the WIE zone to these zones (Fig. 4f). Specifically, the transition from the WIE zone to the FTE zone occurred mainly in the northwest, while the transition from the WIE zone to the WAE zone was concentrated in the southern region (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). By 2100, under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5, the area of the FTE zone is expected to increase by 0.93%, 1.72%, 1.91%, and 1.97%, respectively, compared to 2020 (Fig. 4b, e). In contrast, from 2020 to 2100, the area of the WAE zone is predicted to decrease by 1.29% (SSP1-2.6), 1.19% (SSP2-4.5), 1.21% (SSP3-7.0), and 1.19% (SSP5-8.5). Additionally, under SSP1-2.6, the area of the WIE zone is projected to increase by 0.36%, particularly in the northwest (Supplementary Fig. 12c). Conversely, under SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5, the area of the WIE zone is expected to decrease by 0.53%, 0.70%, and 0.78%, respectively. Notably, the increase in the area of the FTE zone is primarily attributed to the conversion of 5.11 × 104 km2 from the WAE zone to the FTE zone under all SSP scenarios, followed by the conversion of the WIE zone to the FTE zone under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5 by 1.38 × 104, 1.86 × 104, 1.93 × 104, and 2.02 × 104 km2, respectively (Fig. 4g–j).

Soil erosion risk assessment

From 2001 to 2020, the area classified as moderate erosion was the largest, accounting for 55.55% to 55.67% of the total area, and was primarily distributed in the central QTP and the Qilian Mountains (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 13a, b). In contrast, slight and severe erosion accounted for 16.49% to 16.97% and 27.36% to 27.97% of the total area, respectively. Slight erosion was observed in the Qaidam Basin, the southern foothills of the Eastern Himalayas, and along the eastern and northern edges of the QTP. Severe erosion was primarily located in the Chang Tang Plateau, the Hengduan Mountains, and the western Qaidam Basin. The percentage of the area experiencing severe erosion increased by 0.60% from 2001 to 2020, mainly due to transitions from slight (0.48%) and moderate (0.12%) erosion (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 14a). Under four future scenarios, the spatial patterns of soil erosion risks are similar to those observed during the historical period (Supplementary Fig. 13c–f). By 2100, the area of moderate and severe erosion is projected to increase by 1.65%, 1.64%, 1.57%, and 1.49% under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5, respectively, compared to 2020 (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 14a). This increase is driven by the transition from slight erosion in the southeast (Fig. 5d–g and Supplementary Fig. 13c–f). Notably, during the historical period, FTE was the largest contributor to total soil erosion, accounting for 85.22%, while WAE and WIE contributed only 6.60% and 7.45%, respectively (Fig. 5b). Under four SSP scenarios, the contributions of the three types of soil erosion to total soil erosion remain similar to those during the historical period. Importantly, under all SSP scenarios, the contributions of FTE and WAE to total soil erosion increase, while the contribution of WIE shows the opposite pattern (Supplementary Fig. 14b).

Discussion

To address existing knowledge gaps, this study conducted a comprehensive analysis of the spatial-temporal patterns of FTE, WAE, and WIE across the QTP from 2001 to 2100. We further examined the effects of climate change and vegetation dynamics on variations in soil erosion. Notably, we delineated soil erosion zones and assessed erosion risk. Our findings provide insights into how future socioeconomic development will affect the three types of soil erosion on the QTP and identified priority areas for future erosion control. This preliminary evidence is intended to support efforts such as those led by the United Nations to assess soil erosion and inform decision-makers in developing regional strategies for soil conservation.

High FTE values are mainly observed in the Yarlung Zangbo River Basin, the Hengduan Mountains, and the Qilian Mountains. These areas are characterized by low air temperature and large annual temperature range, which result in frequent freeze-thaw cycles that weaken the soil resistance to erosion38. In contrast, WAE gradually increases from northwest to southeast on the QTP, consistent with the spatial distribution of annual precipitation. The southeast receives high annual precipitation and frequently experiences extreme rainfall events in summer, which enhance the potential for WAE. In comparison, the northwest is considerably drier and receives less precipitation39,40. It is also characterized by high wind speeds and a cold climate, along with extensive areas of sparse grassland, sandy land, and desert, all of which contribute to a high incidence of WIE. Meanwhile, the southeast benefits from abundant precipitation, which supports robust vegetation growth, including forest and dense grassland. This vegetation increases surface roughness, reduces wind speed, and enhances soil retention through root reinforcement, thereby resulting in lower WIE41.

Historical and future trends in FTE show a strong dependence on annual precipitation (Fig. 4). Increased precipitation elevates the moisture content in rock and soil. During the freezing process, the volume of liquid water expands by about 1.1 times when it turns into solid ice, which can disrupt soil and rock structures11. Increased precipitation can exacerbate this destruction. Simultaneously, during the melting process, the transport capacity of rainfall and meltwater for soil also intensifies with increasing precipitation42. Importantly, annual precipitation can affect key soil physical properties, such as by reducing soil aggregate stability, thereby increasing the potential for erosion42. Previous research has demonstrated that soil aggregate stability serves as a critical and direct indicator of erosion resistance36. The R and C factors are closely associated with climate change and vegetation conditions, respectively5. Specifically, the R factor is a precipitation-dependent variable43, where a high R value reflects high rainfall erosivity. In contrast, vegetation greening reduces the C factor5. Increases in both rainfall amount and intensity can exacerbate WAE44, whereas vegetation mitigates WAE by enhancing soil stability, intercepting rainfall, and reducing the kinetic energy of raindrops45. Our study found that the R and C factors play significant positive roles in the annual variation of WAE, aligning with the findings of Wang et al.5. However, Ying et al.18 reported that the R factor, which exerts positive feedback on WAE, could offset the benefits of vegetation improvement or a reduced C factor, thereby contradicting our findings. This discrepancy may stem from differences in the calculation method for the C factor, as well as variations in the data sources and spatial resolution of the fractional vegetation cover used in the formula. Over the past two decades, vegetation on the QTP has undergone substantial greening, driven by a warming and wetting climate and elevated atmospheric CO2 concentration (i.e., CO2 fertilization effect)18,46. Concurrently, a series of ecological restoration initiatives, such as the Grain for Green Program and the Returning Grazing Land to Grassland Project, have been implemented to improve vegetation conditions on the QTP32,41,47. As a result, the C factor declined significantly from 2001 to 2020 (P < 0.001), while the R factor increased markedly (P < 0.05). The opposing effects of the R and C factors on WAE largely counterbalance each other, resulting in no significant overall change in WAE. In the future period, the C factor is projected to remain relatively stable across all SSP scenarios, while the R factor is expected to gradually increase, leading to a corresponding rise in WAE. Furthermore, the WF factor plays a crucial role in the dynamics of WIE, exerting strong influence primarily through its effects on wind speed, precipitation, and temperature. Among these variables, wind speed is the dominant climatic driver of WIE. A higher WF value indicates a stronger potential for wind-induced erosion48. In this study, the WF factor exhibits a more pronounced influence on WIE than the vegetation factor, indicating that wind speed reduction is the primary driver behind the decline in estimated WIE rates. This is because reduced wind speed not only suppresses surface water evaporation, thereby increasing soil water content and reducing soil erodibility, but also weakens the wind’s mechanical force, which limits the direct displacement or removal of topsoil, particularly in areas with extensive bare land28,41,49,50.

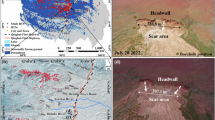

This study introduces an original algorithm to delineate soil erosion zones on the QTP and provides a comprehensive assessment of soil erosion risk. Climatic factors are identified as the primary external drivers of soil erosion on the QTP, shaping both the types and spatial distribution of erosion. Specifically, the Qaidam Basin and the southern foothills of the Eastern Himalayas are recognized as key zones for WIE. The Qaidam Basin is characterized by a dry, cold climate with strong winds, and about 65.0% of the area is covered by the Gobi, sandy crust, shifting sandy land, and wind-eroded landforms28. Conversely, the southern foothills of the Eastern Himalayas feature a subtropical monsoon climate with frequent strong winds. These areas are overlain by abundant loose Quaternary sediments, such as lacustrine, fluvial, and glacial meltwater deposits, that provide a plentiful source of material for WIE. In such regions, the application of straw checkerboard sand barrier may be effective in increasing surface roughness and thereby reducing WIE48. The eastern and southern edges of the QTP experience the most intense WAE, primarily due to abundant precipitation and shallow soils containing loose gravel deposits that are highly susceptible to erosion by rainfall and surface runoff. This region is also an important agricultural area, where croplands are directly impacted by precipitation and runoff, further exacerbating WAE. Notably, about two-thirds of the QTP experiences a mean annual air temperature below 0 °C, a freezing period lasting 7–8 months, and large annual and diurnal temperature fluctuations. These conditions promote frequent freeze-thaw cycles, making FTE the dominant type of erosion on the QTP. Under future climate warming, the frequency and intensity of freeze-thaw cycles are expected to increase across all four SSP scenarios, resulting in the expansion of FTE zones as areas previously dominated by WAE and WIE transition to FTE.

Assessing soil erosion risk is fundamental to understanding the regional soil erosion status and identifying priority areas for implementing effective control and mitigation measures51. We found that the spatial distribution of moderate and severe erosion closely aligns with the FTE zone, which can be attributed to FTE contributing the most to total soil erosion. Under four SSP scenarios, the contributions of FTE and WAE to total soil erosion increase, while the contribution of WIE decreases. These trends reflect substantial temporal variations among the three types of soil erosion: FTE and WAE increase significantly, while WIE decreases markedly (P < 0.001). Vegetation greening offers a viable strategy for controlling soil erosion and restoring degraded ecosystems52, primarily by enhancing soil aggregate stability and increasing resistance to erosion36. Plant root systems act as natural insulators and protect the topsoil by reducing wind velocity and anchoring soil, thereby effectively mitigating WIE41,53. Additionally, vegetation greening can alter surface biophysical properties, such as reducing albedo and aerodynamic or surface resistance, which helps mitigate regional land surface warming54. In turn, this may reduce the possibility of FTE occurring, as land surface temperature is a key driver of FTE55. In comparison, vegetation reduces WAE by enhancing soil protection, intercepting rainfall, and diminishing the kinetic energy of raindrops, ultimately reducing rainfall erosivity5. Climate warming presents an additional challenge, as it accelerates permafrost degradation on the QTP, potentially exacerbating soil erosion through prolonged thawing periods and more frequent freeze-thaw cycles37,55. However, vegetation greening can effectively enhance permafrost stability in degraded grassland56. In general, ecological restoration programs serve as an effective means to promote vegetation greening57. We propose that ecological restoration projects, such as the Grain for Green Program, the Natural Forest Protection Project, and the Returning Grazing Land to Grassland Project, should be implemented in the Chang Tang Plateau, the Hengduan Mountains, and the western Qaidam Basin, where soil erosion is severe due to steep slope, abundant precipitation, or high air temperature. In particular, the southeast should be prioritized for future erosion control efforts, as it exhibits the most concentrated transition from slight to moderate and severe erosion. Moreover, soil erosion on the QTP is closely related to livestock density and intensive grazing activities58. Overgrazing has caused severe grassland degradation59 and accelerated soil erosion58, posing a serious threat to the balance of the livestock-soil-grass ecosystem and reducing grassland productivity. This has led to unprecedented losses in biodiversity and natural habitat60,61. Hence, we propose coordinating grassland ecological protection with the sustainable development of livestock husbandry. This approach involves regularly assessing and adjusting the grazing capacity of pastures based on local conditions, establishing a grass-animal balance, and implementing rotational grazing through scientifically delineated pasture zones62.

This study still has certain limitations and areas for improvement: (1) although the simulation results were validated using WAE and WIE rates derived from Caesium−137 (137Cs) data, providing strong support for their reliability, the limited availability of such data led to a mismatch between the simulation and observation periods, particularly for WIE. This mismatch is likely a key reason for the relatively low consistency between the simulated and observed results. To further enhance the reliability of the validation process, it is essential to conduct extensive field investigations on the QTP using the 137Cs tracing technique in the future to quantify WAE and WIE rates across different regions of the plateau; (2) there may be correlations and feedback mechanisms among different types of soil erosion processes. However, these interrelationships were not explored in this study, and further research is needed to quantify and model such cross-process interactions; (3) given the current lack of comprehensive research on soil erosion, this study can serve as a reference model, and extending similar research to a global scale would facilitate the development of more precise global soil erosion prevention and control strategies, thereby better supporting ecological security and human well-being.

Materials and methods

Study area

The QTP is located in the middle of Asia and southwest China (73.31–104.78°E, 26.00–39.78°N), covering an area of about 2.56 × 106 km2, with an average altitude above 4000 m18,30,33. It occupies ~26.64% of China’s total land area and spans six provinces/autonomous regions: Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai, Gansu, Yunnan, and Sichuan29. The QTP is surrounded by several major mountain ranges, including the Kunlun, Himalayas, Hengduan, Tanggula, and Qilian Mountains (Supplementary Fig. 15), resulting in complex terrain and diverse landscapes63. It is considered a vital ecological security barrier for China and Asia64. The region experiences a continental plateau climate, characterized by high solar radiation, low temperature, and limited precipitation64,65. Vegetation exhibits distinct zonal distributions across the QTP, transitioning from forest to alpine grassland and eventually to alpine desert from southeast to northwest. Alpine grassland is the dominant vegetation type, covering over 60% of the total area8,28,65. Moreover, the dominant soil types include meadow soil, chernozems soil, gray cinnamon soil, gray desert soil, and chestnut soil29.

Data sources and processing

Sources and detailed descriptions of the data, including climate variables, soil properties, topography, and vegetation characteristics for the historical period (2001–2020), are provided in Supplementary Table 1. The latest CMIP6 provides multiple GCMs under different SSP scenarios37. In this study, to consider a series of possible futures, four scenarios were selected from Tier-1 of ScenarioMIP: SSP1-2.6 (SSP1-RCP2.6, global sustainability), SSP2-4.5 (SSP2-RCP4.5, middle of the road), SSP3-7.0 (SSP3-RCP7.0, regional rivalry), and SSP5-8.5 (SSP5-RCP8.5, fossil-fueled development). These four scenarios have been widely used in previous studies37,62,66, particularly in the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)67. Monthly values of five variables including wind speed, precipitation, air temperature, potential evapotranspiration, and fractional vegetation cover were obtained from five GCMs with well-resolved resolution including CESM2 (USA, 1.25 × 0.94°), MPI-ESM1-2-HR (Germany, 0.94 × 0.94°), IPSL-CM6A-LR (France, 1.27 × 2.5°), MRI-ESM2-0 (Japan, 1.13 × 1.13°), and BCC-CSM2- MR (China, 1.13 × 1.13°) for the period 2006–2100. These data were downloaded from the Earth System Grid Federation (https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6). Wind speed values were replaced with the mean value of the corresponding variable from the other three GCMs, as it is not available in BCC-CSM2-MR and CESM2. Since potential evapotranspiration is not available in BCC-CSM2-MR, CESM2, and IPSL-CM6A-LR, it was replaced with the mean value from MPI-ESM1-2-HR and MRI-ESM2-0. Similarly, the fractional vegetation cover was calculated using the mean value from CESM2, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, and MRI-ESM2-0, given that this variable was not provided by the other three GCMs. Compared to observations, CMIP6 projections generally exhibit systematic biases, and thus, the Delta downscaling method was applied to bias-correct the projections under four SSP scenarios for the future period (2021–2100). Moreover, the period from 2006 to 2015 was chosen as the baseline period, with wind speed, precipitation, and air temperature data derived from the China Meteorological Forcing Dataset (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/8028b944-daaa-4511-8769-965612652c49). Potential evapotranspiration and fractional vegetation cover data were obtained from the 1-km Monthly Potential Evapotranspiration Dataset for China (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/8b11da09-1a40-4014-bd3d-2b86e6dccad4) and the China Regional 250 m Fractional Vegetation Cover Dataset (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/f3bae344-9d4b-4df6-82a0-81499c0f90f7), respectively.

Where \({V}_{{future}}\) is the bias-corrected air temperature, wind speed, potential evapotranspiration, and fractional vegetation cover during the future period; \({P}_{{future}}\) is the bias-corrected precipitation during the future period; \({V}_{{baseline},{obs}}\) is the observed air temperature, wind speed, potential evapotranspiration, and fractional vegetation cover during the baseline period; \({P}_{{baseline},{obs}}\) is the observed precipitation during the baseline period; \({V}_{{future},{GCM}}\) is the projected air temperature, wind speed, potential evapotranspiration, and fractional vegetation cover during the future period based on GCMs outputs; \({P}_{{future},{GCM}}\) is the projected precipitation during the future period based on GCMs outputs; \({V}_{{baseline},{GCM}}\) is the projected air temperature, wind speed, potential evapotranspiration, and fractional vegetation cover during the baseline period based on GCMs outputs; and \({P}_{{baseline},{GCM}}\) is the projected precipitation during the baseline period based on GCMs outputs.

As inputs for the Freeze-thaw Erosion Equation, the RUSLE, and the RWEQ, topographic conditions and soil properties were assumed to remain invariant over time. Future vegetation and climate data, including fractional vegetation cover, air temperature, precipitation, wind speed, and potential evapotranspiration, for the period 2021-2100, were used to predict FTE, WAE, and WIE. All data were resampled to a spatial resolution of 500 m × 500 m.

Freeze-thaw erosion estimation

FTE occurs mainly in cold, high-latitude, and high-altitude regions11,42. In this study, the formula from the Soil and Water Conservation Survey in the First National Census for Water Resources was used to determine the lower altitude limit of the FTE region on the QTP. Specifically, the −2.5 °C isotherm of the annual mean air temperature was selected as the lower limit of the permafrost region68. The lowest boundary of the FTE region was defined as 200 m below the altitude corresponding to an annual mean air temperature of −2.5 °C. The calculation is as follows:

where \(H\) is the altitude of the lower boundary of the FTE region (m), \(X\) is the latitude (°E), \(Y\) is the longitude (°N). In this study, based on data from 78 meteorological stations on the QTP from 1956 to 2017, we found that the annual mean air temperature at the Toole weather station was −2.5 °C. Accordingly, an altitude of 3189.3 m was defined as the lowest boundary of the FTE region. Notably, glaciers and lakes were excluded from the FTE region.

Where \(A\) is the air annual temperature range (°C), \(X\) is the latitude (°E), \(Y\) is the longitude (°N), \(H\) is the altitude (m). Aspect and slope were calculated based on the Spatial Analyst Tool in ArcGIS 10.8.

FTE is a complex process closely related to climate, vegetation, and topography42,68. Therefore, this study selected five factors, including air annual temperature range, fractional vegetation cover, annual precipitation, aspect, and slope, as the key variables influencing FTE. The evaluation index system for FTE sensitivity was constructed based on these factors, in combination with the study by Wang et al.38. The FTE intensity index was derived through the weighted summation of multiple factors influencing FTE. The calculation is as follows:

where \(I\) is the FTE intensity index, \({I}_{i}\) is the value of the \(i\) factor, \({W}_{i}\) is the weight of the \(i\) factor. Therefore, we established a system to evaluate the sensitivity of FTE on the QTP (Supplementary Table 2).

Water erosion estimation

WAE mainly occurs through the detachment of soil caused by raindrops or surface runoff69,70,71. The RUSLE is widely used globally for WAE assessments, integrating information on land use/cover types, climate conditions, soil properties, topography, and cropping systems69,70,71. The equations are expressed as follows:

where \(R\) is the rainfall erosivity factor (MJ mm ha−1 h−1 a−1); \(K\) is the soil erodibility factor (t ha h MJ−1 ha−1 mm−1); \({LS}\) is the slope length-steepness factor (dimensionless); \(P\) is the support practices factor (dimensionless); \(C\) is the land cover and management factor (dimensionless); \({S}_{a}\), \({S}_{i}\), \({C}_{l}\), and \({OM}\) are the sand, silt, clay content, and soil organic matter content (%), respectively; \(L\) is the slope length factor; \(S\) is the slope steepness factor; \(\theta\) is the slope (%); \(f\) is the fractional vegetation cover (%); AP is the annual precipitation (mm); A is the percentile slope gradient.

Wind erosion estimation

WIE is influenced by wind speed, vegetation, soil properties, topography, and agricultural activities72. The RWEQ fully accounts for the impacts of climatic conditions, vegetation, and soil properties on WIE and has been widely applied in long-term scale studies of WIE28,73. Therefore, this model was employed in this study to simulate WIE. The calculation is as follows:

Where \(z\) is downwind distance (m), taken as 50 m; \(S\) is the critical plot length (m); \({Q}_{\max }\) is the maximum sediment transmission capacity (kg m−1); \({WF}\) is the weather factor (kg m−1); \({EF}\) is the soil erodible fraction (dimensionless); \({SCF}\) is the soil crust factor (dimensionless); \({COG}\) is the combined vegetation factor (dimensionless); \({K}^{{\prime} }\) is the surface roughness factor (dimensionless); \({u}_{2}\) and \({u}_{10}\) are the mean monthly wind speed at the height of 2 m and 10 m, respectively; \({ETP}\) is the monthly potential evapotranspiration (mm), \(P\) is the monthly precipitation (mm); \(d\) is the number of days in the month; \({S}_{a}\), \({S}_{i}\), \({C}_{l}\), \({OM}\), and \({CC}\) are the sand, silt, clay content, soil organic matter, and calcium carbonate content (%), respectively; \(\theta\) is the slope (%); \(f\) is the fractional vegetation cover (%).

Accuracy verification

137Cs is an anthropogenic radioisotope that has been effectively utilized to quantitatively monitor soil erosion and deposition rates worldwide74,75,76. We collected measured 137Cs data for WAE and WIE on the QTP from previous studies by Wei et al.77 and Yan et al.78 (Supplementary Table 3), which were used to establish linear regressions with the corresponding simulated values. We found that the simulated values of WAE and WIE based on the RUSLE and RWEQ models were highly consistent with the measured 137Cs values (WAE: R2 = 0.839, P < 0.001, WIE: R2 = 0.634, P < 0.001), indicating that the simulation results for these two models on the QTP are reliable.

Soil erosion zone and risk assessment

The discrepancies in units and orders of magnitude among FTE, WAE, and WIE make it necessary to integrate them into a comprehensive index with a limited range of values. In this section, the three types of soil erosion were standardized to range from 0 to 1 using the minimum-maximum normalization method. The “ifelse” function in R 4.2.1 was employed to delineate the erosion zones. The calculation is as follows:

where \(F{TE}\), \({WAE}\), \({WIE}\) represent normalize FTE, WAE, and WIE, respectively.

Additionally, we averaged the three normalized soil erosion values and applied the Natural Breakpoint Method in the Reclassify Tool of ArcGIS 10.8 to classify soil erosion risk into three categories: slight (0–0.108), moderate (0.108–0.252), and severe (>0.252). Notably, we summed the three normalized soil erosion values to assess the total soil erosion.

Statistical analysis

Curve fitting was used to detect temporal variations in soil erosion, and the slope of the linear fitting was employed to analyze the soil loss rate, with significance determined using a t-test. The random forest model has been shown to be the most accurate algorithm compared to various other machine learning algorithms79,80. It was applied to analyze the relationship between soil erosion and its influencing factors, helping to identify the importance of each factor in soil erosion changes. In this model, the R2 value indicates the overall explanation degree of the factors influencing soil erosion variation. Additionally, the contemporary changes in annual precipitation and fractional vegetation cover in the Freeze-thaw Erosion Equation were analyzed, as these two factors are temporal variables that reflect climate change and vegetation conditions, respectively. Similarly, we analyzed the annual variations of the R and C factors in the RUSLE, as well as the WF and COG factors in the RWEQ. Among these, the R and WF factors represent climate change, while the C and COG factors reflect vegetation conditions. The partial correlation coefficient (Pearson’s) between soil erosion and the corresponding climatic variable or vegetation index was calculated to represent the influence of climate change/vegetation dynamics on soil erosion variation. Moreover, the unary linear regression was used to analyze the long-term trends in soil erosion at each pixel using MATLAB platform (version R2023b)48,81,82. The change trends in soil erosion were classified into three types: significant increase (P < 0.05), non-significant change (P > 0.05), and significant decrease (P < 0.05). The conversions of soil erosion types and risk classes between the historical and future periods were quantified using a Sankey diagram. The area percentages of the three types of soil erosion in the soil erosion zones on the QTP were presented using ternary plots. The lollipop chart displayed the changes in the area of soil erosion risk classes and the contribution rates of each soil erosion type to total soil erosion under future SSP scenarios. All figures were generated using the packages of “ggplot2,” “ggtern,” and “ggsankeyfier” in R 4.2.1 or ArcGIS 10.8.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study were described explicitly in Supplementary Table 1 and in the Data Sources and Processing section. The data are publicly available from the following resources. Meteorology data, including air temperature, precipitation, and wind speed from 2001 to 2018, were obtained from the China Meteorological Forcing Dataset available at the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/8028b944-daaa-4511-8769-965612652c49). Date for air temperature, precipitation, and wind speed from 2019 to 2020 were downloaded from the 1-km Monthly Mean Temperature Dataset for China (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/en/data/71ab4677-b66c-4fd1-a004-b2a541c4d5bf), the 1-km Monthly Precipitation Dataset for China (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/en/data/faae7605-a0f2-4d18-b28f-5cee413766a2), and the Homogeneous Grid Dataset of Chinese Land Surface Observation (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/99dd84e2-288d-4db8-b098-8118b3b0c17a), respectively, all of which were collected from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center. In addition, the potential evapotranspiration data from 2001 to 2020 was derived from the 1-km Monthly Potential Evapotranspiration Dataset for China (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/8b11da09-1a40-4014-bd3d-2b86e6dccad4), available at the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center. Soil property data was collected from the Harmonized World Soil Database v1.2 (https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-maps-and-databases/harmonized-world-soil-database-v12/en/), provided by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Datasets for the digital elevation model and fractional vegetation cover were obtained from the SRTM DEM data on the Tibetan Plateau (2012) (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/23e32e3e-8104-4798-b7a1-325df8fd1a95) and the China Regional 250 m Fractional Vegetation Cover Dataset (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/f3bae344-9d4b-4df6-82a0-81499c0f90f7), respectively, both available from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center. Future projection data derived from CMIP6 was obtained from the Earth System Grid Federation (https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6).

Code availability

The custom code used to delineate soil erosion zones is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28874369.

References

Borrelli, P. et al. An assessment of the global impact of 21st century land use change on soil erosion. Nat. Commun. 8, 2013 (2017).

Borrelli, P. et al. Policy implications of multiple concurrent soil erosion processes in European farmland. Nat. Sustain. 6, 103–112 (2023).

Prăvălie, R. Exploring the multiple land degradation pathways across the planet. Earth Sci. Rev. 220, 103689 (2021).

Lang, Y. Q., Yang, X. H. & Cai, H. Y. Quantifying anthropogenic soil erosion at a regional scale-The case of Jiangxi Province, China. Catena 226, 107081 (2023).

Wang, H., Zhao, W. W., Li, C. J. & Pereira, P. Vegetation greening partly offsets the water erosion risk in China from 1999 to 2018. Geoderma 401, 115319 (2021).

Ma, X. F., Zhao, C. Y. & Zhu, J. T. Aggravated risk of soil erosion with global warming–A global meta-analysis. Catena 200, 105129 (2021).

Smith, P. et al. Status of the World’s Soils. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 49, 73–104 (2024).

Wang, Y. F. et al. Effects of soil erosion-deposition on corn yields in the Chinese Mollisol region. Catena 240, 108001 (2024).

Yuan, C. & Fan, H. M. Response mechanism of black soil structure to compound erosion forces in sloping farmland, Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 240, 106103 (2024).

Gholami, H. et al. An explainable integrated machine learning model for mapping soil erosion by wind and water in a catchment with three desiccated lakes. Aeolian Res. 67, 100924 (2024).

Guo, B., Zhang, F. F., Yang, G. & Jiang, L. Improved method of freeze–thaw erosion for the Three-River Source Region in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Geomat Nat. Haz. Risk 8, 1678–1694 (2017).

Demidov, V. V., Ostroumov, V. Y., Nikitishena, I. A. & Lichko, V. I. Seasonal freezing and soil erosion during snowmelt. Eurasian Soil Sci. 28, 78–87 (1995).

Ma, R., Tian, Z. Y., Zhao, Y., Wu, Y. H. & Liang, Y. Response of soil quality degradation to cultivation and soil erosion: a case study in a Mollisol region of Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 242, 106159 (2024).

Borrelli, P. et al. Land use and climate change impacts on global soil erosion by water (2015-2070). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 21994–22001 (2020).

Ma, T. L. et al. Response of soil erosion to vegetation and terrace changes in a small watershed on the Loess Plateau over the past 85 years. Geoderma 443, 116837 (2024).

Crosson, P. Soil erosion estimates and costs. Science 269, 461–464 (1995).

GSP. Global Soil Partnership Endorses Guidelines on Sustainable Soil Management. https://www.fao.org/global-soil-partnership/resources/highlights/detail/en/c/416516/ (2017).

Ying, L. X. et al. Climate change impairs the effects of vegetation improvement on soil erosion control in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Catena 241, 108062 (2024).

Ran, Y. H., Li, X., Che, T., Wang, B. Q. & Cheng, G. D. Current state and past changes in frozen ground at the Third Pole: a research synthesis. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 13, 632–641 (2022).

Zou, D. F. et al. A new map of permafrost distribution on the Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere 11, 2527–2542 (2017).

Peng, Q., Jia, B. H., Lai, X., Wang, L. H. & Huang, Q. F. Characteristics of near-surface soil freeze-thaw status using high resolution CLM5. 0 simulations on the Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 24, e1168 (2023).

Peng, Q., Jia, B. H., Lai, X., Wang, L. H. & Huang, Q. F. Increasing gross primary productivity under soil warming and wetting on the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 024021 (2024).

Zhang, F. et al. Controls on seasonal erosion behavior and potential increase in sediment evacuation in the warming Tibetan Plateau. Catena 209, 105797 (2022).

Liu, H. Y., Yang, Y., Zhang, K. L. & Sun, C. L. Soil erosion as affected by freeze-thaw regime and initial soil moisture content. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 81, 459–467 (2017).

Liu, J. J., Zhang, K. D., Shi, W. B. & Yan, J. X. Effects of freeze-thaw on the detachment capacity of soils with different textures on the Loess Plateau, China. J. Hydrol. 644, 132082 (2024).

Wang, T. et al. Effects of freeze-thaw on soil erosion processes and sediment selectivity under simulated rainfall. J. Arid Land 9, 234–243 (2017).

Sun, L. B. et al. Effect of freeze-thaw processes on soil water transport of farmland in a semi-arid area. Agric. Water Manage. 252, 106876 (2021).

Teng, Y. M. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics and drivers of wind erosion on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Ecol. Indic. 123, 107340 (2021).

Zhao, W. T. et al. Water erosion changes on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and its response to climate variability and human activities during 1982–2015. Catena 229, 107207 (2023).

Dong, S. K. Revitalizing the grassland on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Grassl. Res. 2, 241–250 (2023).

Zhao, L. et al. Changing climate and the permafrost environment on the Qinghai–Tibet (Xizang) plateau. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 31, 396–405 (2020).

Wang, Y. F. et al. Grassland changes and adaptive management on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 668–683 (2022).

Zhao, Z. X. & Dai, E. F. Vegetation cover dynamics and its constraint effect on ecosystem services on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau under ecological restoration projects. J. Environ. Manage. 356, 120535 (2024).

Zhou, W. et al. Grassland productivity increase was dominated by climate in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau from 1982 to 2020. J. Clean. Prod. 434, 140144 (2024).

Huang, B. B. et al. Ecological restoration is crucial in mitigating carbon loss caused by permafrost thawing on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 341 (2024).

Ma, R. T. et al. Vegetation restoration enhances soil erosion resistance through decreasing the net repulsive force between soil particles. Catena 226, 107085 (2023).

Zhang, G. F. et al. Qinghai-Tibet Plateau permafrost at risk in the late 21st century. Earth’s Future 10, e2022EF002652 (2022).

Wang, L. Y., Xiao, Y., Jiang, L. & Ouyang, Z. Y. Assessment and analysis of the freeze-thaw erosion sensitivity on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Glaciol. Geocryol.39, 61–69 (2017).

Ding, Z. Y., Ha, Y. & Zhong, Z. Summer extreme precipitation patterns and synoptic-scale circulation precursors over the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. China Earth Sci. 67, 1625–1638 (2024).

Wang, L. H. et al. Rainfall erosivity index for monitoring global soil erosion. Catena 234, 107593 (2024).

Lin, X. D., Wu, T., Kong, L. Q. & Ouyang, Z. Y. Wind erosion changes from ecological restoration and climatic drivers on the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 23, 100420 (2024).

Zhang, J. G., Liu, S. Z. & Yang, S. Q. The classification and assessment of freeze-thaw erosion in Tibet. J. Geogr. Sci. 17, 165–174 (2007).

Patriche, C. V. Applying RUSLE for soil erosion estimation in Romania under current and future climate scenarios. Geoderma Reg. 34, e00687 (2023).

Fenta, A. A. et al. Spatial distribution and temporal trends of rainfall and erosivity in the Eastern Africa region. Hydrol. Process. 31, 4555–4567 (2017).

Piao, S. L. et al. Characteristics, drivers and feedbacks of global greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 14–27 (2020).

Liu, W., Mo, X. G., Liu, S. X. & Lu, C. H. Impacts of climate change on grassland fractional vegetation cover variation on the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 939, 173320 (2024).

Yu, Q., Lu, H. W., Yao, T. C., Xue, Y. X. & Feng, W. Enhancing sustainability of vegetation ecosystems through ecological engineering: a case study in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Environ. Manage. 325, 116576 (2023).

Sun, R. H. et al. Global wind erosion reduction driven by changing climate and land use. Earth’s Future 12, e2024EF004930 (2024).

Chappell, A. et al. Minimising soil organic carbon erosion by wind is critical for land degradation neutrality. Environ. Sci. Policy 93, 43–52 (2019).

Zhang, G. F. et al. Impact of near-surface wind speed variability on wind erosion in the eastern agro-pastoral transitional zone of Northern China, 1982–2016. Agric. For. Meteorol. 271, 102–115 (2019).

Gilani, H., Ahmad, A., Younes, I. & Abbas, S. Impact assessment of land cover and land use changes on soil erosion changes (2005-2015) in Pakistan. Land Degrad. Dev. 33, 204–217 (2022).

Berendse, F., Ruijven, J. V., Jongejans, E. & Keesstra, S. Loss of plant species diversity reduces soil erosion resistance. Ecosystems 18, 881–888 (2015).

Starke, J., Ehlers, T. A. & Schaller, M. Latitudinal effect of vegetation on erosion rates identified along western South America. Science 367, 1358–1361 (2020).

Li, Y. T. et al. Biophysical impacts of earth greening can substantially mitigate regional land surface temperature warming. Nat. Commun. 14, 121 (2023).

Li, J. L. et al. Impacts of climate change and freeze-thaw cycles on water and sediment fluxes in the headwater region of the Yangtze River, Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Catena 227, 107112 (2023).

Jia, Y. L. et al. Improved permafrost stability by revegetation in extremely degraded grassland of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Geoderma 430, 116350 (2023).

Fan, X. L., Qu, Y., Zhang, J. & Bai, E. China’s vegetation restoration programs accelerated vegetation greening on the Loess Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 350, 109994 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Livestock grazing significantly accelerates soil erosion more than climate change in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: evidenced from 137Cs and 210Pbex measurements. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 285, 106643 (2019).

Dong, S. K., Shang, Z. H., Gao, J. X. & Boone, R. B. Enhancing sustainability of grassland ecosystems through ecological restoration and grazing management in an era of climate change on Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 287, 106684 (2020).

Filazzola, A. et al. The effects of livestock grazing on biodiversity are multi-trophic: a meta-analysis. Ecol. Lett. 23, 1298–1309 (2020).

Liu, L. K. et al. Effect of grazing intensity on alpine meadow soil quality in the eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Ecol. Indic. 141, 109111 (2022).

Wang, X. M. et al. Unintended consequences of combating desertification in China. Nat. Commun. 14, 1139 (2023).

Wang, H. H. et al. Short-term fluctuations of ecosystem services beneath long-term trends. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 203, 107454 (2024).

Yang, Y., Yu, C. L., Liu, M. X. & Wei, H. J. Uncovering the coupling relationships and key factors linking ecosystem services to human well-being through system dynamics: a case study in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 166, 112408 (2024).

Wang, Y. F. et al. Vegetation structural shift tells environmental changes on the Tibetan Plateau over 40 years. Sci. Bull. 68, 1928–1937 (2023).

Pereira, H. M. et al. Global trends and scenarios for terrestrial biodiversity and ecosystem services from 1900 to 2050. Science 384, 458–465 (2024).

IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.).

Fan, J. R., Xu, F. B., Zhang, X. Y., Zhang, X. X. & Liang, B. Evaluating the sensitivity and influential factors of freeze-thaw erosion in Tibet, China. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 992842 (2022).

Dou, X. et al. Risk assessment of soil erosion in Central Asia under global warming. Catena 212, 106056 (2022).

Han, Y., Zhao, W. W., Zhou, A. & Pereira, P. Water and wind erosion response to ecological restoration measures in China’s drylands. Geoderma 435, 116514 (2023).

Das, S., Jain, M. K. & Gupta, V. An assessment of anticipated future changes in water erosion dynamics under climate and land use change scenarios in South Asia. J. Hydrol. 637, 131341 (2024).

Liu, X. F. et al. An improvement of the Revised Wind Erosion Equation by considering the effect of non-photosynthetic vegetation. Geoderma 445, 116880 (2024).

Xu, L. X. et al. An ecosystem services zoning framework for the permafrost regions of China. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 10, 92–98 (2019).

Li, Y. F. et al. Characterizing soil losses in China using data of 137Cs inventories and erosion plots. Catena 203, 105296 (2021).

Shen, Y. L. et al. Predicting soil erosion and deposition on sloping farmland with different shapes in northeast China by using 137Cs. Catena 229, 107238 (2023).

Zhang, X. C. J. & Busteed, P. R. Accuracy and sensitivity of soil erosion estimation using 137Cs technology: a statistical perspective. Geoderma 444, 116863 (2024).

Wei, M. M., Fu, S. H. & Liu, B. Y. Quantitative research of water erosion on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Adv. Earth Sci.36, 740–752 (2021).

Yan, P., Dong, G. R., Zhang, X. B. & Zhang, Y. Y. Preliminary results of using 137Cs to study wind erosion in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Arid Environ. 47, 443–452 (2001).

Logan, T. M., Zaitchik, B., Guikema, S. & Nisbet, A. Night and day: the influence and relative importance of urban characteristics on remotely sensed land surface temperature. Remote Sens. Environ. 247, 111861 (2020).

Wang, Q., Wang, X. N., Zhou, Y., Liu, D. Y. & Wang, H. T. The dominant factors and influence of urban characteristics on land surface temperature using random forest algorithm. Sustain. Cities Soc. 79, 103722 (2022).

A, D., Zhao, W. J., Qu, X. Y., Jing, R. & Xiong, K. Spatio-temporal variation of vegetation coverage and its response to climate change in North China plain in the last 33 years. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 53, 103–117 (2016).

Tian, Q. L. et al. Potential risk of soil erosion on the Tibetan Plateau during 1990–2020: impact of climate change and human activities. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110669 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFF0809102), the “Light of the West” Cross-team Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (xbzg-zdsys-202214), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A2062), and the Science and Technology Program of Gansu Province (23ZDFA017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, software, and investigation, P.J.W., J.J.D., and S.Y.C.; funding acquisition and supervision, S.Y.C.; validation and writing—original draft, P.J.W.; visualization, P.J.W.; writing—review and editing, P.J.W., J.J.D., A.B., H.Y.Z., S.J.W., T.H.W., and S.Y.C.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Jannes Stolte and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, P., Du, J., Bahadur, A. et al. Soil erosion and risk assessment on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Commun Earth Environ 6, 365 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02355-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02355-5