Abstract

The Durban floods of 11–12 April 2022 is the worst flood disaster in South Africa’s history and raised questions about the role of climate change in the event. Meso-scale dynamics, involving processes that cannot be resolved at the spatial resolutions of current global climate models, played an important role in the heavy falls of rain. Here we report on the development of a convection-permitting conditional extreme event attribution modelling system, well-suited to explore the role of climate change in meso- and convective-scale extreme weather events. The African-based attribution system makes use of a computationally-efficient variable-resolution atmospheric model and runs on a local high-performance computer in South Africa. Similar systems can potentially be rolled out across the Global South (and North). The system relies on a km-scale perturbed-physics ensemble to describe the simulation/structural uncertainty associated with an extreme weather event in an anthropogenically-warmed world, compared to counterfactual cooler worlds where the effects of anthropogenic forcing are (partially) removed. Simulations reveal a pronounced role of climate change in the Durban floods. Average rainfall in the Durban region is simulated to have been at least 40% higher during the two days of the flood, relative to rainfall in a counterfactual cooler world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Durban floods of 11–12 April 2022 is South Africa’s worst flood disaster in terms of the impact on human life. The flood resulted in 544 mortalities1, displaced 42 0002 and directly impacted 140, 000 people1. The economic toll of this disaster has been vast, with an estimated cost in excess of US$3.6 billion1. The flooding occurred in association with heavy falls of rain, with several weather stations in the larger Durban area (Fig. 1) reporting more than 300 mm of rain in a 24-hour period3,4. To put this in perspective, average annual rainfall in Durban is about 1015 mm, with the average April total about 90 mm5. The extreme rainfall event resulted from a cut-off low-pressure system that initially formed as an upper-air trough over the Atlantic Ocean to the west of South Africa. The system moved from west to east across the South African plateau from 10 to 12 April4. As it approached the east coast, a meso-scale low formed to its east, over the Indian Ocean east of the KwaZulu-Natal Province (Fig. 1), late on 11 April4. The low deepened over the warm waters of the Agulhas current4 as it migrated southwards along the KwaZulu-Natal coast on 12 April. The Météo-France Regional Specialized Meteorological Centre (RSMC) La Réunion classified it as a subtropical low, named Issa, by midday on the 12th. The classification was made based on the storm structure and the gale force winds it induced6.

The study domain (left) shows the rivers that rise in the higher mountainous areas and transect the eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality, including the city of Durban, before they flow into the Indian Ocean. The eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality (light-red highlighted land-area in the right-bottom insert) is one of the 11 districts of the KwaZulu-Natal Province of South Africa (right-top insert), and the most affected by the April 2022 flood event. The red-marked latitude-longitude box in the right-bottom insert shows the study domain’s geographical location and is hereafter referred to as the larger Durban area (also see Methods).

The President of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa, visited communities impacted by the storm on the 13th of April 2022, and stated “This disaster is part of climate change. It is telling us that climate change is serious; it is here”7. Indeed, given the historical impact of storm Issa and the cut-off low from which it formed, the possible role of climate change in the Durban floods was widely discussed in South Africa3. An objective, modelling-based assessment of the role of climate change in the Durban floods is indeed the topic of this paper. Before exploring this further, however, it is essential to point out that the impact of the storm was the consequence of a complex combination of circumstances, not uncommon in the developing world. First and foremost, the city of Durban, like many other African cities, has struggled to meet the housing demand resulting in the substantial expansion of informal structures across the region. Building-based land use data from GEOTERRA Image8 showed an informal unregulated structure count in the city of more than 240, 000 dwellings in 2021. It is estimated that 23,500 buildings and more than 75,000 people are currently located in areas with a high likelihood of flooding9. At risk in particular are communities that settled below the flood lines of rivers such as the Umgeni, Mlazi and Mbokodweni that transect the larger Durban area (Fig. 1), or along the steep hill slopes of the region, where mudslides and landslides are not uncommon during periods of excessive rainfall10. These current realities all contribute to how flood hazard can compound into disasters11,12,13.

A very similar cut-off low induced flood event occurred in Durban in September 1987 (more than 600 mm of rain fell in four days in some locations14,15), leading to the deaths of 506 people16. In April 2019, a cut-off low caused about 160 mm of rain in a single day in some locations, and 73 people died in the subsequent flooding and mudslides17. Evidence of severe flooding in Durban goes back as far as 1856, when 303 mm of rain was recorded in a 24-hr period17. Despite these well-known risks, zoning regulations in terms of flood lines and mud-slide risks are not enforced in eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality (which includes Durban)3. Moreover, South Africa has a limited tradition or track-record of evacuating vulnerable communities under the threat of flood risks, and there are few demonstrable community-based flood early warning systems in place18. It may be said that, with or without climate change, South Africa should have been better prepared for the possibility of a mega-flood in Durban9,16. There is clearly high susceptibility to flooding impacts due to growing exposure and growing vulnerability.

Two studies have thus far commented on the role of climate change in the Durban floods. Considering the historical record of major flood events in Durban, an assessment was made that flood frequencies have likely doubled during the last century17. World Weather Attribution (WWA) published a report in May 2022, making the assessment that climate change has increased the intensity of rainfall that caused the 11–12 April 2022 Durban floods by a factor of 4–8%, and has made rainfall events of this magnitude twice as likely to occur, relative to pre-industrial conditions19. Specifically, the event was estimated to have had a return period of ~20 years in today’s anthropogenically-warmed climate, but would have had a return period of ~40 years in a pre-industrial world. The WWA report employed the standard probability-based methodology for extreme event attribution, namely to compare the statistics of a metric that characterizes the extreme event in question (in this case heavy falls of rain in KwaZulu–Natal) in today’s anthropogenically-warmed world to its statistics in a counterfactual cooler world that has not warmed anthropogenically20,21. Towards this comparison, a multi-model ensemble of global climate model (GCM) simulations, supplemented by an ensemble of regional climate model (RCM) simulations over Africa, was used. The usual choice for the cooler world in probability-based attribution studies is pre-industrial climate, and this is also the case for the WWA study. The WWA statistical analysis used as its metric two-day rainfall totals averaged over the KwaZulu-Natal Province, without considering specifically the changing attributes of cut-off low induced rainfall in a changing climate. This is despite heavy rainfall in the province also resulting from a wide variety of very different weather systems, such as tropical temperate troughs22, tropical cyclones23, tropical storms24 and meso-scale convective systems25. Moreover, at the resolution of the GCMs and RCMs used in the WWA report, ranging from about 50 to 200 km in the horizontal, deep convection occurring in meso-scale weather systems such as subtropical lows, squall lines and tropical cyclones can’t be resolved26,27,28. These processes thus need to be parameterized (treated statistically), which is regarded as a primary source of structural uncertainty in GCM and RCM simulations undertaken at these relatively low resolutions29. Specifically, the meso-scale surface low that formed off the coast of Durban and played an important role in the floods via the deep convection it induced4 is not sufficiently resolved at the spatial resolutions of the models used in the WWF report. The findings of the report are therefore open to question, and further explorations of the role of climate change in the event are needed.

An alternative approach to extreme event attribution is the conditional approach, also referred to as the storyline methodology for attribution20,21,30. This uses the technologies of numerical weather prediction to compare the attributes of the actual extreme weather system that caused the disaster to the attributes of the system in a counterfactual cooler world, in which (some) anthropogenic warming has not occurred20,21. This approach necessarily involves specifying the initial conditions of the atmosphere and ocean ahead of the occurrence of the extreme event, and additionally may prescribe boundary conditions during its evolution, such as the sea-surface temperatures and large-scale atmospheric circulation. This allows for the simulation of the weather system in today’s anthropogenically-warmed world. To obtain comparable simulations of the weather system in a counterfactual cooler world, some specification is needed of how either the sea-surface state or atmospheric state, or both, would have been different in the counterfactual cooler world20,21. The conditional approach has become popular to assess the impacts of climate change on weather systems that are not sufficiently resolved by GCMs in terms of their spatial structure or intensity, tropical cyclones being the primary example30,31,32.

Convection-permitting climate models33, also known as km-scale models, have the ability to resolve the circulation- and thermodynamics of meso-scale weather systems, such as the subtropical low that played an important role in the Durban floods. There is much hope that km-scale global climate change modelling will remove many of the structural uncertainties of GCMs, for example by resolving rather than parameterizing deep convection34. For now, however, such simulations remain largely limited to regional domains due to computational constraints35. Km-scale modelling also has the potential to add substantial value to extreme event attribution, although its application in probability-based approaches is unlikely in the foreseeable future, also due to computational restrictions. However, km-scale modelling is widely applied in numerical weather prediction centres across the world for forecasting over regional domains36; setting up conditional extreme event attribution systems, focused on exploring the role of climate change in specific high-impact weather events, is computationally feasible. Only a handful of km-scale conditional extreme event attribution modelling studies, focusing on mesoscale weather systems such as tropical cyclones, meso-scale lows and thunderstorms, have been undertaken to date31,37,38,39. We have developed a km-scale conditional extreme event attribution simulation system, based on a variable-resolution global atmospheric model that can be integrated in stretched-grid mode over an area of interest, and applied it to the case of the Durban floods of 11–12 April 2022. The simulations were performed on an African high-performance computing system, and this paper reports on our findings.

Results

The devastating floods of 11–12 April 2022 in South Africa’s larger Durban area (Fig. 1) followed heavy falls of rain that occurred along the south and central coast of the KwaZulu-Natal Province4. The coastal strip from just to the north of Durban, southwards to the northern coastal areas of the Eastern Cape Province (Fig. 1), received more than 200 mm of rainfall in the 48-hour period of 11–12 April 2022 (Fig. 2a). At the Agricultural Research Council (ARC) weather stations Southbroom and Port Shepstone located to the south of Durban, 515 mm and 454 mm of rain was recorded, respectively, during this period. Several weather stations of the South African Weather Service (SAWS) located in the Durban region consistently reported 1-day rainfall totals above 300 mm for the period 11 April at 06 GMT to 12 April 2022 at 06 GMT4. Moreover, the heavy rainfall of 11–12 April was preceded by about 100 mm of rain during the period 8–10 April3 over the same region, which contributed to soil moisture approaching saturation levels when the cut-off low induced rainfall began on 11 April3.

a Two-day observed rainfall (mm) from ARC weather stations for 11 April at 00 GMT to 13 April 00 GMT, interpolated onto a 0.01° latitude-longitude grid; b corresponding rainfall totals from the ensemble median of the CCAM 3.8 km resolution simulations, interpolated onto a 0.05° latitude-longitude grid; c mean-sea-level pressure showing the position and intensity of the meso-scale low in ERA5 reanalysis data on 12 April 2022 at 12 GMT and d corresponding position and intensity of the meso-scale low in the CCAM control simulation. The red dot shows the location of Durban.

The median of the 64-member perturbed physics Conformal-Cubic Atmospheric Model (CCAM) ensemble (see Methods) realistically portrays the spatial pattern of high rainfall totals that occurred along the KwaZulu-Natal south coast on 11–12 April, including the rainfall maximum that was recorded around the border region of the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal Provinces (Fig. 2a, b). Rainfall totals in the CCAM ensemble median are lower along the KwaZulu-Natal south coast in comparison to the ARC observations.

For the larger Durban region, which includes the catchment area of rivers transecting eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality (Fig. 1), the area-averaged rainfall for the ARC station data over the two-day period is 137 mm. For the CCAM ensemble median it is 92 mm (10th percentile 77 mm, 90th percentile 119 mm, maximum value 161 mm). These numbers equate to an underestimation of average two-day rainfall totals of 44%, 33% and 13%, by the 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles, respectively. For the case of the observed rainfall maximum (515 mm) at the Southbroom weather station, this falls within the upper range of the CCAM simulated rainfall totals (552 mm) averaged over ~ 25 km2 grid-boxes (see Methods). It may be noted that the two-day rainfall recorded at Southbroom equates to more than 50% of the annual average rainfall at Durban5 – a staggering statistic. The underestimation of rainfall totals and extremes in the CCAM ensemble should be interpreted in this context. Although most ensemble members underestimate both the observed two-day rainfall totals averaged over the Durban area, and the maximum rainfall recorded at individual ensembles over these two days, the 90th percentile of the ensemble approaches these values, and the observations are spanned by the overall range of the ensemble.

The circulation system responsible for the rainfall over the Durban region on 11–12 April 2022 was a cut-off low and its associated surface meso-scale low that formed late on 11 April 20224. The Météo-France RSMC at La Réunion estimated the center of the surface-low to be located at 30.8 °S and 31.6 °E by 12 GMT on 12 April, with a central pressure of 997 hPa6. In ERA5 reanalysis data (see Methods), with approximately 31 km resolution in the horizontal, the low is estimated to have had a central pressure of about 1004 hPa (Fig. 2c) and closely represents the Météo-France RSMC estimated position. In the CCAM control simulation, the central pressure of the system is about 992 hPa (Fig. 2d), and it ranges between 991 hPa (10th percentile) and 1003 hPa (90th percentile) across the ensemble.

We refer to the CCAM simulations of the actual April 2022 high-impact weather in Durban as the 2022 warmer world simulations, given the anthropogenic warming that has occurred globally by 2022 (see Methods). To perform simulations of the relative intensity of the Durban rainfall of 11–12 April 2022 for a counterfactual cooler world (see Methods), multi-decadal trends (1979-2021) in April sea-surface temperature and a number of atmospheric thermodynamic and circulation variables were removed from the atmospheric and sea-surface initial state of 11 April at 00 GMT. We distinguish specifically between a set of simulations in which temperature and circulation trends were removed from the initial state, and a set where atmospheric trends in moisture were additionally removed (see Methods). A corresponding set of simulations was also performed where trends were added rather than removed from the initial state, to generate future warmer world simulations (see Methods). The future warmer world simulations are performed to help distinguish between the role of anthropogenic forcing and the chaotic nature of the atmosphere when considering the evolution of the weather system in question in a cooler world constructed from detrended initial states20 (also see Methods). The assumption of persisting historical trends into the future limits the interpretation of the future warmer world simulations as an estimate of how the weather system may respond to continued anthropogenic forcing (see Methods).

Some key features of the oceanic and atmospheric trends present in the ERA5 reanalysis data (see Methods) over the period are shown in Fig. 3. Sea-level pressure trends reveal a distinct pattern of increasing sea-level pressure south of South Africa and suggest more frequent ridging of high-pressure systems over the South African eastern interior, east coast and adjacent Indian Ocean (Fig. 3a). Such a trend would induce stronger southerly and easterly flow across the eastern parts of South Africa, and across the Indian Ocean to the east. The decreasing trends in April temperatures at 850 hPa across eastern South Africa (Fig. 3b) are consistent with a persistent increase in cold-air advection from the south, which in the reanalysis overwhelms the local warming effects of increasing greenhouse concentrations over the 1979-2021 period. Note that in terms of annual temperatures, ERA5 data shows increasing trends over southern Africa, consistent with the regional effects of global warming. The April trend of cooling at 850 hPa is thus counterintuitive if not for the observed trend in sea-level pressure and associated increase in cold-air advection. Mixing ratios over and to the east of the KwaZulu-Natal coast show positive trends (Fig. 3c), likely in response to the increased advection of oceanic moisture from the southeast, in combination with enhanced evaporation above the Agulhas current. That is, sea-surface temperatures in the narrow Agulhas current region along the east coast of KwaZulu-Natal exhibit pronounced increasing trends (Fig. 3d), consistent with the observed warming of the Agulhas current40,41. Moreover, the increases in SSTs off the South African east coast, and decreases in temperature at 850 hPa, effectively imply a steeper environmental lapse rate, conducive to more frequent atmospheric instability and convection.

Conditioning the cut-off low and meso-scale surface low to the counterfactual cooler world (see Methods) includes the removal of circulation trends from the observed atmospheric initial state on 11 April. For some parts of the world, substantial uncertainty exists in terms of projected changes in regional circulation under anthropogenic warming, given the confounding impacts of pronounced multi-decadal variability42. In the Southern Hemisphere, however, there is strong evidence of the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) exhibiting a strong positive trend since 1950, particularly in the austral summer and autumn43. This is regarded as one of the most prominent signals of anthropogenic climate change that can already be detected in the Southern Hemisphere, with the stratospheric ozone depletion being the prominent driver of summer trends, and the enhanced greenhouse effect the prominent driver of trends in autumn44. The strengthening SAM occurs in association with the poleward displacement of the Southern Hemisphere westerlies, and a strengthening of the subtropical high-pressure cells around 40 °S45. The latter occurs in association with observed Hadley Cell expansion over the last four decades, which in turn has been attributed to warming of the tropical upper troposphere in response to increasing CO2 concentrations46 as well as to stratospheric cooling (induced by depleted ozone)47. In this paper we assume that the ERA5 trends of increasing sea-level pressure south of South Africa in April, with a ridging pattern over the South African east coast, is the regional manifestation of the hemispheric-scale positive trend in SAM and polar expansion of the Hadley Cell, which in turn are both anthropogenically forced. These hemispheric trends implying a strengthening of the high-pressure systems south of South Africa have been extensively demonstrated48, for the autumn, winter and spring seasons, within the context of the stronger high-pressure systems inhibiting frontal rainfall over South Africa’s winter rainfall region (southwestern Cape). The changes in the regional circulation have in turn been assessed to be associated with stronger post-frontal ridging of the high-pressure systems and enhanced southeasterly flow over the South African east coast48, entirely consistent with our findings in Fig. 3a. Moreover, the anthropogenic forcing of trends in SAM and the Hadley Cell circulation have been linked to these regional changes48, rather than natural multi-decadal variability.

To further explore the sea-level pressure trend in Fig. 3a we have explored the tendencies within the shorter periods of 1979-2000 and 2001-2021 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Sea-level pressure strengthened south of South Africa during both these periods, with a clear ridging pattern over the South African east coast. Both the 1979-2000 and 2001-2021 trends are consistent with stronger southeasterly flow over the KwaZulu-Natal coast and would promote more northerly locations of low-pressure systems (north of strengthening ridging highs), consistent with the 1979-2021 trend. The consistency of this signal even over shorter (~20 year) periods, in the presence of inter-annual and decadal variability, further argues for it being of anthropogenic forcing origin. Trends in sea-level pressure in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase Six (CMIP6) multi-model ensemble49 may provide further insights into the role of anthropogenic forcing in the ERA5 trends. These are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 for an ensemble average of 36 CMIP6 models (see Supplementary Note 1), for the 43-year-long periods of 1979–2021, 1858–1900 (the last 43 years of the 1850–1900 period, used in the IPCC AR6 to approximate pre-industrial conditions), 2024-2026 (centered around 2045 as relevant to the construction of a future warm world in this paper, see Methods) and 2056-2098. The CMIP6 historical simulations and projections under shared socio-economic pathway 3-7.0 (SSP3-7.0) were used to undertake this analysis. Model agreement is shown in shades. For the pre-industrial period, when anthropogenic forcing of climate was still relatively weak, there is no model coherency in terms of the direction of change of the ensemble average. This is to be expected for a climate-system that is semi-stationary apart from the occurrence of possible multi-decadal variability with a periodicity of ~ 40 years, randomly distributed across the ensemble of models. For the period 1979-2021 the picture changes completely: more than 2/3rds of the models agree on increasing sea-level pressure (strengthening Atlantic Ocean High) south of South Africa, with about 60% of models in agreement of increasing sea-level pressure inducing stronger southeasterly flow over eastern South Africa. For the period 2024-2066 a similar pattern of increasing sea-level pressure remains in place. For the end-of-century period 2056-2098, the strongest trends are projected to occur southeast of South Africa, inducive of stronger easterly flow over the South African east coast. The above results strongly support the notion that the trend of increasing sea-level pressure south of South Africa for the period 1979-2021, with enhanced southeasterly flow over the South African east coast, is a consequence of anthropogenic forcing (compare Supplementary Fig. 2b to Supplementary Fig. 2a). We can also consider projected changes in sea-level pressure from the ensemble average of GCMs relative to the pre-industrial climatology for April (Supplementary Fig. 3a). There is very strong model agreement (more than 80%) of increasing sea-level pressure south of South Africa, strengthening from 1979-2021 (Supplementary Fig. 3b) to 2024-2066 (Supplementary Fig. 3c) to 2056-2098 (Supplementary Fig. 3d). This further supports the notion that rising sea-level pressure south of South Africa in April is an anthropogenically-induced climate change signal.

The CCAM ensemble spread in the location of the low at 12 GMT on 12 April 2022 (36 hours into the simulation) is shown in Fig. 4 (black dots). Several members closely represent the observed position of the low, about 100 km southeast of Durban, as estimated by the Météo- France RSMC (green dot). However, the spread of the ensemble in terms of the center of the low reveals considerable variation in the location where it potentially could have been located. The majority of ensemble members are indicative of a low closer to the coast than was observed, and in a number of cases the low is simulated to have made landfall. Should landfall of the subtropical low indeed have occurred, the heavy falls of rain and associated flooding could have been worse. The position of the low exhibits a markedly more southerly location in the detrended simulations (blue markings in Fig. 4), and a marked more northerly location in the simulations where trends were added to the April 2022 initial state (red markings in Fig. 4). This pattern is consistent with increasingly stronger ridging over the east coast of South Africa, from the counterfactual cooler world, to the 2022 warmer world to the future warmer world simulations, which would result in a persistent northward displacement of low pressures forming north of the strengthening highs. Note that on 11–12 April, a high-pressure system with center southeast of South Africa indeed contributed to easterly flow over southern Africa4. One of the few regional climate modelling studies focused on landfalling tropical cyclones in southern Africa in a changing climate similarly projected a northward displacement of tropical cyclone tracks in the Mozambique Channel in an anthropogenically-warmed world, due to the strengthening of anti-cyclonic circulation over the southwest Indian Ocean50.

The Météo-France RSMC estimated position of the low is shown by the green dot for 12 GMT on 12 April 2022, and the corresponding simulated positions of the low in the CCAM ensemble by black dots. The simulated positions of the lows in the 1979 cooler world (future warmer world), obtained by removing (adding) atmospheric and SST trends from (to) the 11 April 2022 00 GMT initial state, are indicated by blue (red) dots.

Sea-level pressure averaged across the eastern southern African domain and adjacent Indian Ocean (34 °S to 26 °S, 28 °E to 38 °E) shown in Fig. 4 is statistically different and higher for the 2022 warmer world compared to the 1979 cooler world (Fig. 5a), and correspondingly is also statistically different and higher for a future warmer world compared to the 2022 warmer world. This is consistent with the general strengthening of the subtropical high-pressure belt over and to the south of southern Africa in an anthropogenically-warmed world51 and specifically the sea-level pressure trends for April depicted in Fig. 3a. The surface-pressure in the surface low is statistically different (see Methods) and consistently higher for the 2022 warmer world compared to the 1979 cooler world, and similarly, for the future warmer world, sea-level pressure in the center of the low is statistically different and higher compared to the 2022 warmer world (Fig. 5b).

a Box-whisker plots are shown for the range of average sea-level pressure (hPa) over eastern southern Africa and adjacent Indian Ocean (34 °S to 26 °S, 28 °E to 38 °E) at 12 GMT on 12 April 2022 in the CCAM ensemble simulations for a 1979 cooler world constructed from detrended sea-level pressure, SSTs, atmospheric temperature and moisture (CM ave), detrended sea-level pressure, SSTs and atmospheric temperatures only (C ave), the 2022 warmer world (T), a future warm world constructed from trended sea-level pressure, SSTs and atmospheric temperatures (W ave) and a future warm world constructed from trended sea-level pressure, SSTs and atmospheric temperature and moisture (WM ave). b is the same, but for the intensity of the low in hPa. The central pressure of the low as estimated by the Météo-France RSMC at La Réunion is indicated by a cross and for the ERA5 simulation by a closed dot, in the box-whisker plot for the 2022 warmer world (T), for 12 April at 12 GMT. The lines in the boxes represent the 25th percentile (Q1), the median (Q2) and the 75th percentile (Q3) for the specific simulation set. The end of the arms in these plots are Q1–1.5IQR and Q3 + 1.5IQR, where IQR = Q3–Q1, and values above or below these thresholds are marked with open dots. The CM ave (CM min), C ave (C min), W ave (W min) and WM ave (WM min) simulations are significantly different from the T (T min) simulations at a 95% confidence interval as per the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

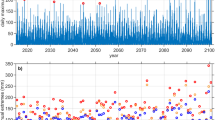

Rainfall totals are simulated to have been higher along the KwaZulu-Natal coast during 11 and 12 April in the median of the CCAM ensemble for the 2022 warmer world, compared to a 1979 cooler world constructed with detrended temperatures and sea-level pressure (Fig. 6a), and the projected increase in precipitation is even higher relative to a 1979 cooler world constructed by also detrending moisture (Fig. 6b). Over the larger Durban region (Fig. 1), average rainfall totals for the 2022 warmer world are simulated to have ranged between 70 mm (10th percentile) and 130 mm (90th percentile) over the 48-hour period of 11 and 12 April (Fig. 7a). Average totals as high as 161 mm are simulated, spanning the observed average total (as measured by the ARC weather stations) of 137 mm. The median of the simulated area-averaged rainfall is 98 mm for 11 and 12 April for the 2022 warmer world, which represents a 40% increase over the corresponding 70 mm for the counterfactual cooler world constructed with detrended 1979-2021 sea-level pressure, SSTs and atmospheric temperatures, and a 104% increase over the 48 mm for the 1979 cooler world with sea-level pressure, temperature and moisture detrended. In terms of the maximum rainfall amount recorded across model grid-boxes in the larger Durban region, this is simulated to have ranged between 280 mm (10th percentile) and 390 mm (90th percentile), with a median value of 330 mm in the 2022 warmer world (Fig. 7b). Grid-box rainfall is simulated to have been as high as 550 mm, spanning the observed (point) weather station recorded maximum of 515 mm (noting that the grid-box average rainfall is for areas of ~25 km2, not directly comparable to point-based observations). For the future warmer world (see Methods), further large increases in average precipitation for the larger Durban area are simulated with respect to the 2022 warmer world. Area-averaged rainfall is 190 mm as per the ensemble median (118% increase) for a future warmer world constructed from added sea-level pressure, SSTs and atmospheric temperature trends, and 220 mm (152% increase) when moisture trends are additionally added (Fig. 7a). Substantially larger grid-box maxima are also simulated.

Projected changes in 2-day rainfall totals (mm) are shown for 11–12 April 2022 as per the median of the CCAM ensemble for the 2022 warmer world, relative to the counterfactual cooler world obtained through detrending 1979–2021 a sea-level pressure, SSTs and atmospheric temperature and b sea-level pressure, SSTs, atmospheric temperature and atmospheric moisture. c, d are the same but obtained from simulations for a future warmer world versus the 2022 warmer world, with the future warmer world constructed from adding rather than subtracting the trends.

a Box-whisker plots for rainfall averaged over the larger Durban region (30.28 °S to 29.2 °S and 29.77 °E to 31.2 °E) for 11–12 April in the CCAM ensemble for a 1979 cooler world constructed from detrended sea-level pressure, SSTs and atmospheric temperature and moisture (CM ave), detrended sea-level pressure, SSTs and atmospheric temperatures only (C ave), the 2022 warmer world (T), a future warmer world constructed from trended sea-level pressure, SSTs and atmospheric temperatures (W ave) and a future warmer world constructed from trended sea-level pressure, SSTs and atmospheric temperature and moisture (WM ave). The two-day rainfall averaged over the larger Durban region in the ARC weather station data is indicated by the solid square in the plot for the 2022 warmer world (T). b is the same as a, but for the maximum rainfall recorded in the larger Durban region for the two-day period across the model grid-boxes. The two-day rainfall totals recorded by the Southbroom (closed dot) and Port Shepstone (cross) ARC weather stations are shown in the plot for maximum rainfall for the 2022 warmer world (T max). The lines in the boxes represent the 25th percentile (Q1), the median (Q2) and the 75th percentile (Q3) for the specific simulation set. The end of the arms in these plots are Q1–1.5IQR and Q3 + 1.5IQR, where IQR = Q3-Q1, and values above or below these thresholds are marked with open dots. The CM ave (CM max), C ave (C max), W ave (W max) and WM ave (WM max) simulations are significantly different from the T (T max) simulations at a 95% confidence interval as per the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Rainfall totals are projected to be lower over the southern part of the Eastern Cape Province coastline, for the 2022 warmer world compared to the 1979 cooler worlds. This is likely attributable to the simulated northward displacement of the low-pressure system in the 2022 warmer world (Fig. 4). This northward displacement of the low-pressure system likely also contributed to the higher rainfall totals over the KwaZulu-Natal coast and northern part of the Eastern Cape coast (Fig. 6a, b). In fact, on the southern flank of the low, an associated low-level jet was substantially stronger in the 2022 warmer world, compared to the 1979 cooler world (Fig. 8a, b). This jet was likely fueled by enhanced moisture availability from increased sensible and latent heat fluxes above the relatively warm Agulhas current in the 2022 warmer world (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, the higher SSTs above the Agulhas current, in conjunction with the cooling at 850 hPa, implies stronger low-level instability in the 2022 warmer world compared to the 1979 cooler world. Note that the factual (observed) low-pressure system and associated low-level jet migrated southwards along the KwaZulu-Natal coast between its formation late on the 11th of April until its weakening late on the 13th of April4. The even higher rainfall totals in the future warmer world correspond to a further northward displacement in the low-pressure system (Fig. 4) and associated strengthening of the low-level jet (Fig. 8c, d). The added trends in terms of increasing SSTs over the Agulhas current region, and cooling at 850 hPa would also contribute to increased low-level instability in the future warmer world atmosphere.

Projected changes in the zonal component of the wind (m/s) are shown for 12 April 2022 at 12 GMT as per the median of the CCAM ensemble for the 2022 warmer world relative to the counterfactual cooler world obtained through detrending 1979–2021 a sea-level pressure, SSTs and atmospheric temperature and b sea-level pressure, SSTs, atmospheric temperature and atmospheric moisture. c, d are the same but obtained from simulations for a future warmer world versus the 2022 warmer world, with the future warmer world constructed from adding rather than subtracting the trends.

Discussion

The Durban flood of 11–12 April 2022 is the worst flood disaster in South Africa’s history, with 544 people having lost their lives. Along the coastal strip south of Durban more than 200 mm of rainfall was recorded. In the larger Durban region, including the inland catchment area of the major rivers, area-averaged rainfall was 137 mm over the two-day period. Individual weather stations recorded two-day rainfall totals as high as 515 mm (more than half of the average annual rainfall of Durban). By the night of 11 April, major rivers transecting the larger Durban region such as the Umgeni were in flood. The rainfall was caused by an upper-air cut-off low-pressure system that moved from west to east across the South African interior, and a mesoscale surface-low that formed east of its axis, late on 11 April. The surface low likely developed because of the conservation of absolute vorticity as the cut-off low moved from the South African plateau towards the coast, rather than, as has been suggested4, in response to high SSTs. Such surface-lows commonly develop over the oceanic areas along the Eastern Cape coast and KwaZulu-Natal coast, to the east of approaching cut-off lows52. The southeasterly winds occurring to the south of the centers of these lows are a primary cause of heavy falls of rain occurring in response to cut-off lows52,53,54.

We applied a km-scale perturbed-physics ensemble to compare the rainfall that occurred in association with the cut-off low and mesoscale low to what would have occurred in a counterfactual cooler world where some anthropogenic warming has not occurred. The cooler world was constructed by detrending the atmospheric and sea-surface temperature initial states used in the model simulations using trends calculated over the period 1979-2021 (see Methods). At 3.8 km resolution, the observed intensity of the mesoscale low is well resolved by the ensemble, as opposed to being underestimated in ERA5 reanalysis data. Along the coast and in the larger Durban area the median of the ensemble underestimates rainfall totals, but both the average and maximum observed rainfall are spanned by the range of the ensemble.

As is typical for cut-off lows present in the upper-air over the eastern interior of South Africa, a high-pressure system was present at the surface, with its center southeast of South Africa, and with easterly flow to its north55. The meso-scale surface low formed north of the high-pressure system, with a strong southeasterly low-level jet to the south of the low4. Pronounced trends are present in the April sea-level pressure field indicative of more pronounced ridging of surface high-pressure systems, with associated trends in temperature and low-level moisture, for the period 1979-2021. This change in the regional circulation is consistent with anthropogenic-induced hemispheric changes in the Southern Hemisphere, specifically the multi-decadal positive trend in SAM and the expansion of the Hadley Cell43,46,47,48. CMIP6 models consistently show coherency in projecting strengthening high-pressure systems south of South Africa and associated increasing easterly flow over eastern South Africa in April for today’s anthropogenically-warmed world compared to pre-industrial climate, with this pattern persisting and strengthening under low-mitigation futures.

When the 1979-2021 thermodynamic and circulation trends are removed from the initial oceanic and atmospheric state to produce a counterfactual cooler world (see Methods), the surface low-pressure system and its low-level jet are simulated to consistently form further to the south. This, in combination with increased moisture availability above a warmer Agulhas current, were important contributing factors to rainfall totals over the larger Durban area simulated to be 40–107% higher for the 2022 warmer world, compared to the 1979 cooler world. The perturbed physics ensemble is thus indicative of anthropogenic forcing having made the 2022 floods substantially worse than in a counterfactual cooler world obtained by removing 1979–2021 climatological trends. When trends are added to generate a future warmer world, the surface low consistently occurs further to the north and further increases of two-day rainfall totals are simulated for the larger Durban area. This finding, obtained by applying the trend ‘in the opposite direction’ compared to when generating the counterfactual cooler world, and obtaining a rainfall response in the same direction (that is, further increases in rainfall) confirms the robustness of the anthropogenic signal detected in the 2022 warmer world simulations. Our assessment is that the increased moisture availability over the KwaZulu-Natal coast in April is likely the result of systematic anthropogenic trends in terms of increased advection of oceanic moisture from the southeast (the consequence of systematic trends in dynamic circulation), in combination with enhanced evaporation above the Agulhas current and the thermodynamics of a warming regional atmosphere. This suggests a systematic anthropogenic influence on the formation of cut-off low induced low-pressure systems along the KwaZulu-Natal coast in today’s warmer world, in terms of both their northward displacement and increased moisture availability.

In the report by WWA19, rainfall totals associated with the Durban floods were estimated to have been only 4–8% higher, compared to a pre-industrial world. The GCM ensembles typically used for probability-based extreme event attribution, and the RCM ensembles additionally used in the WWA report19, are integrated at spatial resolutions where they can at best only partially resolve the circulation dynamics of mesoscale processes, and cannot resolve the deep convection occurring in association with these systems26,27,28. The WWA report was produced as an operational product, and was widely publicized56, but has to date not been peer-reviewed. Its findings are questioned by the results described in this paper. More generally, WWA seems to apply the same probability-based approach to extreme event attribution, based on large ensembles of relatively low-resolution GCM ensembles that represent pre-industrial conditions and today’s anthropogenically-warmed world, to weather events ranging from heatwaves57 and droughts58 to cut-off lows59 and meso-scale lows19. It is questionable if this approach is suitable to make attribution statements where meso-scale weather events were prominent in the severe weather event of interest. For example, it has been assessed that low-resolution GCM ensembles are inadequate for attribution assessments of Australian east-coast lows28.

The conditional approach to extreme weather event attribution also has some disadvantages. First and foremost, the assumption is made that the weather system would have occurred in the counterfactual cooler word, which is not necessarily the case32. Secondly, the trends introduced to the observed initial SST and atmospheric state can create imbalances in physical relationships and generate initial states that are physically implausible to occur (e.g. in terms of atmospheric stability profiles). Thirdly, since conditional extreme event attribution assumes the formation of the weather system that catalyzed the extreme event in a cooler world, it can thus not make statements about the changing probability of the occurrence of extreme events in warmer worlds. Our results are also model-dependent, but in principle it should be possible to generate multi-model ensembles of km-scale perturbed physics conditional extreme event attribution simulations. An advantage of our approach is that at the km-scale the simulations fully resolve the mesoscale weather system responsible for the Durban floods, whilst at the same time the dynamics of the severe convective rainfall that led to the flooding are at least partially resolved. The simulations were performed on a high-performance computer in Africa, and the attribution system was designed in Africa, implying that an African-based attribution modelling system has been developed. Using a flexible and computationally efficient stretched-grid variable-resolution modelling approach, there is the potential for similar systems to be deployed on relatively small high-performance computers in the Global South, at least until the time that global multi-model km-scale modelling systems become available through initiatives such as Earth Virtualization Engines (EVE, 2023)60.

Our findings suggest a pronounced role of climate change in making the rainfall event that led to the Durban floods of 11 and 12 April 2022 more intense. Other studies point to a detectable increase in the frequency of extreme rainfall events in Durban as a consequence of climate change17,19. There is thus a clear need for urgent adaptation action to build resilience against increasing flood risk. However, climate change adaptation options in rapidly growing African cities is a challenging and complex issue in its own right, and suggesting such options falls largely out of the scope of this paper. Several scholars have in fact been reflecting on how the disaster unfolded in Durban in April 202211,13. We would like to provide only two broad-scale perspectives in this regard. The first is that tens of thousands of people in the larger Durban region remain living below flood lines and against steep hill slopes where mud slides may occur during periods of excessive rainfall. It is not realistic to expect that this exposure and vulnerability will be removed overnight, and consequently there is a clear need for a step-up in disaster management in this region. Specifically, there is a need to develop operational procedures through which thousands, or even tens of thousands of people can be evacuated out of harms’ way as part of Early Warning Systems informed by reliable short-range weather forecasting. There is no tradition in South Africa for the evacuation of several thousands of people in only a few days in response to flood risk, but clearly there is a need for the urgent development of such operations. The second perspective is that there is clearly a need to build resilience to flood risk in the larger Durban region in response to increasing risks due to climate change. This may involve convincing and supporting communities to relocate to safer locations, an expensive and complex issue for any city in which growth is fast and informal.

Methods

The model used for the conditional extreme event attribution simulations is a variable-resolution global atmospheric model, the conformal-cubic atmospheric model (CCAM) of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO)61,62. CCAM solves a set of nonhydrostatic equations in a pressure-based sigma coordinate63 with a semi-implicit semi-Lagrangian solution procedure61,64, on a reversibly-staggered grid64. Physical parameterizations for convection, cloud microphysics and boundary layer turbulent mixing are scale-aware. CCAM runs coupled to a dynamic land-surface model65,66. A stretched (Schmidt factor 6.25) C384 grid was used to obtain 3.8 km horizontal resolution on the high-resolution panel, with 35 levels in the vertical. The high-resolution panel is centered at Durban (latitude 29.9 °S and longitude 31.0 °E) and covers an area of about (1500 km)2, before the resolution gradually decreases away from the area of interest. The simulations were performed on the Lengau cluster of the Centre for High-Performance Computing in South Africa.

The conditional extreme event attribution methodology employed here follows that of the pioneering studies of attribution of landfalling North Atlantic hurricanes31,32. In this approach to attribution, the weather system that caused the disaster of interest is effectively inserted into a counterfactual cooler world, in which (some) anthropogenic warming has not occurred. The attributes of the weather system in the counterfactual cooler world are then compared to the attributes in today’s (factual) anthropogenically-warmed world. The extent to which initial and/or boundary conditions are prescribed for the conditioning of the weather system in a cooler world varies across different studies, in some cases involving only SSTs, but potentially also atmospheric temperatures, moisture and circulation20,21. Note that the conditional approach to attribution assumes that the weather system that caused the disaster in today’s anthropogenically-warmed world, also would have occurred in a counterfactual cooler world.

We followed specifically the methodology of one of the first conditional extreme event attribution studies, which was focused on the heavy falls of rain caused by Hurricane Harvey in Texas32, to numerically set up the counterfactual cooler world. This involves making use of ERA5 reanalysis data67 to calculate trends over the period 1979-2021 (taking note of the greater reliability of reanalysis data for the remote sensing era, starting in 1979). These trends are then removed from the initial atmospheric and SST state from which the actual observed extreme event evolved, to effectively insert the weather system into a counterfactual cooler world. The use of reanalysis data likely facilitates the most realistic depiction of anthropogenically-induced trends in regional climate in recent decades, as opposed to relying on GCM simulations. An alternative approach is indeed to make use of GCM projections to calculate the systematic change between variables in today’s warmer world and a counterfactual cooler world (most studies select a pre-industrial world), and to use these changes to modify the initial and boundary conditions for simulation of the weather system in the counterfactual cooler world31. If the conditioning also involves circulation variables, the question arises whether observed multi-decadal trends (or projected multi-decadal changes) in circulation at regional scales are indeed signatures of regional climate change, or alternatively the consequence of multi-decadal climate variability. Most conditional extreme event attribution studies avoid this question by conditioning the counterfactual cooler-world simulations to only SSTs and atmospheric temperature and moisture, given the relative certainty of climate change inducing trends or changes in atmospheric thermodynamics42. However, this approach runs the risk of introducing physical inconsistencies by not also prescribing anthropogenically induced changes in circulation that are consistent with the changes in thermodynamics. Where the counterfactual cooler world is also conditioned on circulation changes32, such as in our methodology, it is important to demonstrate that these changes are likely anthropogenically induced (see Results). Moreover, we have shown that the circulation trends in the ERA5 reanalysis data and the CMIP6 ensemble average are qualitatively similar, with both data sets indicative of increasing sea-level pressure south of South Africa and associated enhanced easterly flow over eastern southern Africa (see Results and Supplementary Information). We consequently do not expect qualitatively different findings if the attribution simulations should be undertaken with trends as present in the CMIP6 ensemble average (as opposed to ERA5 derived trends). Note that in our experiments we have detrended specifically the April monthly averages for the variables of atmospheric temperature and mixing ratio, sea-surface temperature and sea-level pressure, given that the extreme event occurred in this month.

Our conditional extreme event attribution modelling system applied to explore the role of climate change in the extreme weather that resulted in the Durban floods is based a 64-member perturbed physics ensemble. The value of perturbed physics ensembles as a modelling framework for extreme event attribution simulations has been demonstrated in the context of North Atlantic hurricanes, in terms of exploring the attributes of the weather system under consideration in terms of its thermodynamics and dynamics in cooler and warmer worlds32. The simulations of the actual event in today’s factual warmer world were initialized (a cold-start) on 11 April 2022 at 00 GMT from ERA5 reanalysis data. We note that in this regard, with 31 km resolution in the horizontal ERA5 is the highest resolution global reanalysis data set, and deemed the most suitable to initialize the km-scale model. Moreover, the ERA5 data is of sufficiently high-resolution to describe the initial state of the synoptic-scale cut-off low, noting that at the time of model initialization the meso-scale surface low has not yet formed. The simulations were for a 48-hr period, spanning the entire duration of heavy rainfall over the larger Durban area4, running ‘freely’ from the point of initialization on the stretched C384 grid. That is, the simulations were in ‘numerical weather prediction mode’, rather than nudged within the reanalysis data. We refer to these simulations as the 2022 warmer world, today’s factual warmer world or today’s anthropogenically-warmed-world simulations, noting the considerable global warming trend since 1979. In the ERA5 reanalysis, annual global surface air temperature increased by about 0.8 °C during the period 1979–202143.

It would have been beneficial to have available a km-scale model climatology over the area of interest, to contextualize whether the underestimation of rainfall totals by most ensemble members (see Results) is part of a negative model bias (systematic underestimation) in terms of simulated rainfall totals over KwaZulu-Natal. Such simulations would also enable the estimation of the statistical distribution of extreme events in the model’s present-day climatology, which in turn would enable estimating how rare the extreme event (as represented by the perturbed physics ensemble) is, relative to the underpinning model climatology. However, km-scale model climatologies are computationally expensive to obtain, with only a single such climatology published for an African domain33. Moreover, none of the existing attribution studies undertaken at the km-scale31,37,38,39 made use of model biases in their analysis, likely due to computational restrictions. It may also be noted that model biases are expected to impact on the model simulations of both cooler and warmer worlds, with the effects of biases implicitly assumed to cancel when calculating the climate change signal as in Fig. 6. This assumption is commonly made when calculating the projected climate change signal for simulated future climates relative to present-day or pre-industrial climates.

To obtain the counterfactual cooler world simulations, trends identified for the period 1979-2021 for the month of April were subtracted from the 11 April 2022 00 GMT initial state. Using the detrended initial state, we proceeded to repeat the 64-member perturbed physics ensemble of simulations. These simulations we refer to as the 1979 cooler world, or counterfactual cooler world, simulations. Greenhouse gas, ozone and aerosol concentrations in these simulations are for April 1979 as used in the historical-period simulations of CMIP6. We performed two variations of this experiment. In the first, sea-surface temperatures, sea-level pressure, atmospheric temperature and atmospheric moisture were detrended and the trends subtracted from the observed initial state of 11 April 2022 at 00 GMT, as obtained from the ERA5 data. In the second experiment sea-level pressure and atmospheric and sea-surface temperatures were detrended, but atmospheric moisture was kept in its observed (11 April 2022 at 00 GMT) state. Both sets of 1979 cooler world simulations can be compared to the 2022 warmer world simulations, in terms of the statistics of heavy rainfall, and the dynamics and thermodynamics of the weather system that caused the heavy falls of rain. A comparison of the two cooler-world experiments allows for an exploration of the role of trends in atmospheric moisture in the occurrence of heavy falls of rain in the 2022 warmer world.

Correspondingly and finally, ‘future warmer world’ perturbed physics ensemble simulations were also performed, by repeating the two experiments described above, but with the trends added to (not subtracted from) the 11 April 2022 00 GMT observed initial state. Adding a further 0.8 °C of global warming to the 2022 initial state results in a global warming level of about 2 °C, corresponding to the 2040 s under Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 3-7.0 (SSP 3-7.0)68; these simulations were consequently performed with radiative forcing (e.g. greenhouse gas, ozone and aerosol concentrations) for the year 2045. Adding historical trends to an atmospheric initial state to produce a future warmer world relies on the additional assumption that these trends will persist into the future. For example, if trends of steepening atmospheric lapse rates have occurred in the historical past, simply persisting these into the future may lead to setting up unrealistic initial states, in that these may be convectively unstable. This may result in rapid and unrealistic outbreaks of convection at model initialization. The future warmer world experiments should thus be seen as a sensitivity experiment, further exploring the effects of a warming atmosphere on the extreme event in question, yet subject to the possible physical inconsistencies of simply extrapolating historical trends into the future. There is, however, an important reason for this type of experiment to be performed: extreme event attribution using the conditional approach aims to simulate extreme weather events with ensembles constructed using approaches reminiscent of those of short-range weather forecasting. Given that the atmosphere is chaotic, changing the initial state to generate a cooler world may lead to a difference in outcome of more mundane weather, purely because of the perturbation in initial conditions20 (the starting point in an extreme event). This may lead to the spurious conclusion that climate change played a key role in the observed (factual) outcome of the event. To safeguard against this effect, it is important to also apply the perturbation in the opposite direction, and to check if the observed event becomes even more extreme in a future warmer world20. This approach was followed in attribution simulations for hurricanes Sandy and Harvey32,69.

In all experiments, the Clausius Clapeyron equation was used to check that unrealistic supersaturated moisture values were not generated from the trend-adjusted temperature and/or moisture fields. Similarly, the generation of negative values of moisture was not allowed. In the above approach to generating initial state fields, the model geopotential (mass) field was not detrended, and similarly neither was the momentum (the horizontal and vertical wind components). Although the adjusted moisture fields can be kept physically consistent with the temperature fields, adding trends to an atmospheric initial state likely results in physical imbalances. In numerical weather prediction, physical imbalances in the initial conditions are resolved by geostrophic adjustment processes to provide a balanced state after some hours. Experimental design should thus allow for sufficient integration time for such balances to be restored, in this specific approach to extreme event attribution. In the case of the experiments undertaken here, given that intense rainfall only started to occur about 9 hours after model initialization, and the meso-scale low formed only about 21 hours later4, we argue that initializing on the 11th at 00Z offers a suitable time for the required adjustment processes to occur.

Our methodology is an example of the conditional approach to attribution with the simulations performed at km-scale (convection-permitting) spatial resolutions. Undertaking the simulations at the km-scale is particularly important if the weather system that caused the extreme weather is meso-scale or smaller and is characterized by nonhydrostatic atmospheric dynamics. In such cases, convection-permitting simulations are likely more capable to resolve the relevant dynamics and thermodynamics, as well as the role of climate change in altering these processes, compared to relatively low-resolution GCM or RCM simulations (whether these are undertaken within the probabilistic or conditional framework). With the increasing international focus on km-scale climate modelling and increases in computational power, studies exploring km-scale modelling for extreme event attribution are starting to emerge within the conditional approach38,39, but remain for now out of the (computational) reach of the probabilistic approach.

The particular set of perturbed physics parameterizations used to generate the 64-member ensemble simulations were selected to strengthen the exploration of the role of convection in the weather event. Given the scale-aware convection scheme used in CCAM (which is based on an earlier mass-flux scheme70), we selected parameters that describe the role of different convective cloud processes in the dynamics of the weather event, as well as different cloud microphysical schemes and boundary layer processes (Table 1).

Area-averaged rainfall totals are calculated for the larger Durban region shown in Fig. 1, covering the area 30.28 °S to 29.2 °S and 29.77 °E to 31.2 °E. Towards these calculations the CCAM data was interpolated to a latitude-longitude grid of 0.05° resolution. The CCAM rainfall maximum for each ensemble member over the larger Durban area, as shown in Fig. 7b, was calculated across these grid-boxes, for which the surface areas equate to ~25 km2. Average sea-level pressure is calculated for a larger domain covering eastern southern Africa and the adjacent Indian Ocean (34 °S to 27 °S and 28 °E to 38 °E). The ARC creates operational rainfall surfaces at a 0.01° spatial resolution for rainfall as recorded by their network of automatic weather stations. For the two-day period of 11 and 12 April 2022, the hourly rainfall values per station were accumulated and the resulting rainfall totals were interpolated using the operational methodology71 to obtain the rainfall map in Fig. 2a.

Data availability

The model output and observational data underpinning Figs. 2–8 are available via Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.7845314. The CMIP6 data used to construct the figures in the SI section is available via the EGFS. For Fig. 1 (geographical study area) we used data from South Africa SRTM 30 Meter digital elevation model available at https://rcmrd.africageoportal.com. Data on the river network is from the Global RiverATLAS https://www.hydrosheds.org/hydroatlas. Data displayed on the South Africa Country, Province, District and Municipalities Boundaries is available from the South Africa (ZAF) Administrative Boundary Common Operational Database (COD-AB) at https://za.africageoportal.com.

Code availability

No custom code was developed as part of this paper.

References

EM-DAT, CRED / UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium, https://doc.emdat.be/docs/data-structure-and-content/emdat-public-table/. Accessed: March 2024.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (iDMC). http://www.internal-displacement.org/. Accessed 24 March 2024.

Schulze, R. & Hattingh, M. What did cause the April KZN floods?. Water Wheel 21, 24–27 (2022).

Thoithi, W., Blamey, R. & Reason, C. Floods over East Coast South Africa: Interactions between a mesoscale convective system and a coastal Meso-Low. Atmosphere 14, 78 (2023).

Zepner, L., Karrasch, P., Wiemann, F. & Bernard, L. ClimateCharts.net – an interactive climate analysis web platform. Int. J. Digital Earth 14, 338–356 (2022).

Météo-France. Tropical Cyclone forecast warning (South-west Indian Ocean). A warning number 1/11/20212022. http://www.meteo.fr/temps/domtom/La_Reunion/webcmrs9.0/anglais/activiteope/bulletins/cmrs/CMRSA_202204121200_ISSA.pdf (2022).

The Guardian newspaper. Available at: https://theguardian.com 1995 to present. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/14/south-african-police-disperse-crowd-calling-for-aid-after-flooding (2022).

GEOTERRA Image, https://geoterraimage.com (2024).

CSIR.’eThekwini Municipality Climate Risk Profile’, in GreenBook MetroView. https://ethekwini-riskprofile.greenbook.co.za (2023).

MacRobert, C. How geology put a South African city at risk of landslides’. The Conversation, 21 April 2022. https://theconversation.com/how-geology-put-a-south-african-city-at-risk-of-landslides-181627.

Sutherland, C., Roberts, D. & Douwes, J. Constructing resilience at three different scales: The 100 Resilient Cities programme, Durban’s Resilience Journey and everyday resilience in the Palmiet Rehabilitation. Hum. Geogr. 12, 33–49 (2019).

Kellman, I. Disaster by choice: How our actions turn natural hazards into catastrophes. Oxford University Press (2020).

Sutherland, C. The direct and indirect climate change impacts, loss and damages in selected at-risk communities in Durban as a result of the April 2022 floods, Centre for Environmental Rights. https://cer.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/CER-Report-Sutherland-FINAL-28-Feb-2024.pdf (2024).

Bell, F. G. Floods and landslides in Natal and notably the Greater Durban Region, September 1987: A retrospective view. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 31, 59–74 (1994).

Singleton, A. T. & Reason, C. J. C. Variability in the characteristics of cut-off low pressure systems over subtropical southern Africa. Int. J. Climatol. 27, 295–310 (2007).

Engelbrecht, F. A., Le Roux, A., Vogel, C. H. & Mbiyozo, A.-N. ‘Is climate change to blame for KwaZulu-Natal’s flood damage?’ ISS Today, Institute for Security Studies. Accessed at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/is-climate-change-to-blame-for-kwazulu-natals-flood-damage (2022).

Grab, S. W. & Nash, D. J. A new flood chronology for KwaZulu-Natal (1836–2022): the April 2022 Durban floods in historical context. South Afr. Geographical J. 106, 476–497 (2023).

Engelbrecht, F. A. & Vogel, C. H. When early warning is not enough. One Earth 4, 1055–1058 (2021).

Pinto, I. et al. Climate change exacerbated rainfall causing devastating flooding in Eastern South Africa. World Weather Attribution. Available at: https://www.ss.org/climate-change-exacerbated-rainfall-causing-devastating-flooding-in-eastern-south-africa/ (2022).

Shepherd, T. G. A common framework for approaches to extreme event attribution. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2, 28–38 (2016).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1513–1766 (2021).

Hart, N. C., Reason, C. J. C. & Fauchereau, N. Tropical–extratropical interactions over Southern Africa: three cases of heavy summer season rainfall. Monthly Weather Rev. 138, 2608–2623 (2010).

Malherbe, J., Engelbrecht, F. A., Landman, W. A. & Engelbrecht, C. J. Tropical systems from the southwest Indian Ocean making landfall over the Limpopo River Basin, southern Africa: a historical perspective. Int. J. Climatol. 32, 1018–1032 (2012).

Mpungose, N., Thoithi, W., Blamey, R. C. & Reason, C. J. C. Extreme rainfall events in southeastern Africa during the summer. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 150, 185–201 (2022).

Blamey, R. C. & Reason, C. J. C. Mesoscale convective complexes over southern Africa. J. Clim. 25, 753–766 (2012).

Prein, A. F. et al. A review on regional convection-permitting climate modeling: Demonstrations, prospects, and challenges. Rev. Geophys. 53, 323–361 (2015).

Lucas-Picher, P. et al. Convection-permitting modeling with regional climate models: Latest developments and next steps. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Clim. Change 12, e731 (2021).

Lane, T. P. et al. Attribution of extreme events to climate change in the Australian region-A review. Weather and Climate Extremes 100622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2023.100622 (2023).

Sherwood, S. C., Bony, S. & Dufresne, J.-L. Spread in model climate sensitivity traced to atmospheric convective mixing. Nature 505, 37–42 (2014).

Reed, K. A. & Wehner, M. F. Real-time attribution of the influence of climate change on extreme weather events: a storyline case study of Hurricane Ian rainfall. Environ. Res.: Clim. 2, 043001 (2023).

Patricola, C. M. & Wehner, M. F. Anthropogenic influences on major tropical cyclone events. Nature 563, 339–346 (2018).

Wang, S. S., Zhao, L., Yoon, J. H., Klotzbach, P. & Gillies, R. R. Quantitative attribution of climate effects on Hurricane Harvey’s extreme rainfall in Texas. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 054014 (2018).

Kendon, E. J., Prein, A. F., Senior, C. A. & Stirling, A. Challenges and outlook for convection-permitting climate modelling. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 379, 20190547 (2021).

Palmer, T. We still need a climate ‘CERN’. Phys. World 37, 15 (2024).

Coppola, E. et al. A first-of-its-kind multi-model convection permitting ensemble for investigating convective phenomena over Europe and the Mediterranean. Clim. Dyn. 55, 3–34 (2020).

Clark, P., Roberts, N., Lean, H., Ballard, S. P. & Charlton-Perez, C. Convection-permitting models: a step-change in rainfall forecasting. Meteorological Appl. 23, 165–181 (2016).

Attema, J. J., Loriaux, J. M. & Lenderink, G. Extreme precipitation response to climate perturbations in an atmospheric mesoscale model. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 014003 (2014).

Matte, D. et al. On the potentials and limitations of attributing a small-scale climate event. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099481 (2022).

Martín, M. L. et al. Major role of marine heatwave and anthropogenic climate change on a Giant hail Event in Spain. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107632 (2024).

Rouault, M., Dieppois, B., Tim, N., Hünicke, B. and Zorita, E. Southern Africa climate over the recent decades: description, variability and trends. In Sustainability of Southern African Ecosystems under Global Change: Science for Management and Policy Interventions 149-168 (2024). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Rouault, M., Penven, P. & Pohl, B. Warming in the Agulhas Current system since the 1980’s. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L12809 (2009).

Shepherd, T. G. Atmospheric circulation as a source of uncertainty in climate change projections. Nat. Geosci. 7, 703–708 (2014).

Gulev, S. K. et al. Changing State of the Climate System. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J.B.R., Maycock, T.K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 287–422 (2021).

Eyring, V. et al. Human Influence on the Climate System. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 423–552 (2021).

Fogt, R. L. & Marshall, G. J. The Southern Annular Mode: variability, trends, and climate impacts across the Southern Hemisphere. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Clim. Change 11, e652 (2020).

Lu, J., Deser, C. & Reichler, T. Cause of the widening of the tropical belt since 1958. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L03803–L03805 (2009).

Gerber, E. P. & Son, S.-W. Quantifying the summertime response of the Austral jet stream and Hadley cell to stratospheric ozone and greenhouse gases. J. Clim. 27, 5538–5559 (2014).

Burls, N. J. et al. The Cape Town “day zero” drought and Hadley cell expansion. Npj Climate and Atmospheric Science 2 (2019).

Tebaldi, C. et al. Climate model projections from the Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) of CMIP6. Earth Syst. Dynam. 12, 253–293 (2021).

Malherbe, J., Engelbrecht, F. A. & Landman, W. A. Projected changes in tropical cyclone climatology and landfall in the Southwest Indian Ocean region under enhanced anthropogenic forcing. Clim. Dyn. 40, 1267–1286 (2013).

Engelbrecht, F. A., McGregor, J. L. & Engelbrecht, C. J. Dynamics of the conformal-cubic atmospheric model projected climate-change signal over southern Africa. Int. J. Climatol. 29, 1013–1033 (2009).

Molekwa, S., Engelbrecht, C. J. & Rautenbach, C. D. Attributes of cut-off low induced rainfall over the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 118, 307–318 (2014).

Taljaard, J. J. Cut-off lows in the South African region. South African Weather Bureau Technical Paper No 14, 153 (1985). South African Weather Service, Pretoria, South Africa.

Singleton, A. T. & Reason, C. J. C. Numerical simulations of a severe rainfall event over the Eastern Cape coast of South Africa: sensitivity to sea surface temperature and topography. Tellus A: Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 58, 335–367 (2006).

Engelbrecht, C. J., Landman, W. A., Engelbrecht, F. A. & Malherbe, J. A synoptic decomposition of rainfall over the Cape south coast of South Africa. Clim. Dyn. 44, 2589–2607 (2015).

CNN. Climate change doubled chance of South African floods that killed 435 people, analysis shows’. https://edition.cnn.com/2022/05/13/africa/south-africa-floods-climate-intl/index.html (2023). Accessed: March 2024.

Philip, S. et al. Extreme April heat in Spain, Portugal, Morocco & Algeria almost impossible without climate change (2023). Imperial College London. https://doi.org/10.25561/103833.

Kimutai, J. et al. Human-induced climate change increased drought severity in Horn of Africa (2023). Imperial College London. https://doi.org/10.25561/103482.

Kreienkamp, F. et al. Rapid attribution of heavy rainfall events leading to the severe flooding in Western Europe during July 2021 (2021). World Weather Attribution.

EVE. The Berlin Summit for EVE: Toward closing the climate information gap. https://mpimet.mpg.de/en/communication/news/the-berlin-summit-for-eve-toward-closing-the-climate-information-gap (2023).

McGregor, J. L. C-CAM: Geometric aspects and dynamical formulation. CSIRO Atmospheric Research Technical Paper No. 70 (2025). Available from https://www.cmar.csiro.au/e-print/open/mcgregor_2005a.pdf.

McGregor, J. L. and Dix, M. R. An Updated Description of the Conformal-Cubic Atmospheric Model. In High Resolution Numerical Modelling of the Atmosphere and Ocean, [Hamilton, K., Ohfuchi, W. (eds)]. Springer, New York, 51-75 (2008).

Engelbrecht, F. A., McGregor, J. L. & Rautenbach, C. J. deW. On the development of a new nonhydrostatic atmospheric model in South Africa. South Afr. J. Sci. 103, 127–134 (2007).

McGregor, J. L. Geostrophic adjustment for reversibly staggered grids. Monthly Weather Rev. 133, 1119–1128 (2005). (2005).

Kowalczyk, E. A. et al. The CSIRO Atmosphere Biosphere Land Exchange (CABLE) model for use in climate models and as an offline model. CSIRO Mar. Atmos. Res. Pap. 13, 42 (2006).

CSIRO. ‘Conformal Cubic Atmospheric Model’, CCAM documentation pages. https://research.csiro.au/ccam (2024).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Lee, J. Y. et al. Future global climate: scenario-based projections and near-term information. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J.B.R., Maycock, T.K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 553-672 (2021).

Lackmann, G. M. Hurricane Sandy before 1900 and after 2100. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 547–559 (2015).

McGregor, J. L. A new convection scheme using a simple closure. In “Current issues in the parameterization of convection”, BMRC Research Report 93, 33-36. https://research.csiro.au/ccam/wp-content/uploads/sites/520/2024/01/1377337417.pdf (2003).

Malherbe, J., Dieppois, B., Maluleke, P., Van Staden, M. & Pillay, D. L. South African droughts and decadal variability. Nat. Hazards 80, 657–681 (2016).

Acknowledgements