Abstract

Energy insecurity, or the inability to afford energy needs, affects most low-income households in the United States and leads to risky choices and additional insecurities including food and health. Although there are government programs designed to provide relief from energy insecurity, eligibility is usually determined by household income, and those with incomes close to the threshold face uncertainty or may be left out. In many cases, these households turn to energy-limiting behaviors as a strategy to lower their electric utility bills. Here we explore the relationship between energy insecurity and energy-limiting behaviors and investigate alternative solutions such as energy storage and rooftop solar. This analysis demonstrates that solar and energy storage can offset two-thirds of the bill savings that households could attain through severe energy-limiting behavior. These systems could complement existing energy assistance programs to provide long-term bill relief, enabling occupants to live in their homes with comfort and dignity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Numerous programs are designed to provide relief to individuals and families of low income who struggle to pay their electric utility bills due to high energy burden, or the percentage of their median income spent on utility bills. Eligibility for these programs is often determined by household income. Households with incomes slightly above the eligibility threshold may face energy insecurity or the inability to meet basic household energy needs, and may be forced to choose between paying for energy and other essentials such as food or medicine1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Managing energy insecurity may lead some to turn to unsafe energy-limiting behaviors, such as setting the thermostat in their homes to uncomfortable or even unsafe temperatures, which can dramatically cut energy use (note that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulates workplace thermostat setpoints between 68 and 78 degrees). Households may also reduce their appliance usage by limiting the number of loads in the clothes washer, dryer, or dishwasher, and limiting use of stovetops, ovens, and countertop appliances. These energy-limiting behaviors help struggling households afford their bills but may also prevent these households from being captured by energy burden metrics3,4,6,7,8,9.

Energy assistance programs in the United States, such as the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) and the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program, have been focused on addressing the material hardship households face when paying their utility bills, using household size and income thresholds as criteria for eligibility2,3,4,7. This financial hardship can emerge from the accumulation of utility bills, which leads to high energy burdens and debt, and in its most extreme cases to the disconnection of services by the provider because of lack of bill payment3,9,10,11. Yet, use of an income limit or economic-based indicators can bypass households that engage in behavioral strategies to reduce their energy burden but that nevertheless suffer from energy insecurity and energy poverty3,4,6,11,12,13.

When households are incapable of satisfying their energy needs, they experience energy insecurity6,7,10,11,14. Every four years, the U.S. Energy Information Administration conducts a nationally representative survey of American households regarding their energy characteristics, consumption, and expenditures, called the Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS). According to the 2020 results of that survey, 33.58 million households are reported to experience energy insecurity15. In response to energy insecurity, households engage in energy-limiting behaviors, reducing their use of energy to minimize the financial burden and meet other basic necessities, often at the expense of comfort or even safety3,4,6,7,11,12.

Energy-coping strategies can include prioritizing energy bills over other basic needs (e.g., food, transportation, health) or reducing the household’s use of certain energy services (e.g., heating, cooling, water heating, cooking)1,3,4,6,9,10,12. The RECS found that, in 2020, 24.6 million households prioritized paying for energy over food or medicine, 6.35 million could not afford to use air-conditioning equipment, and 4.93 million could not afford to use heating equipment15. With these behavioral strategies, other financial coping mechanisms also play a role, such as pursuing formal (government-based) and informal (network-based) assistance to pay energy bills and managing the bills through different strategies like carrying debt, skipping payments, or practicing bill balancing3,6,10.

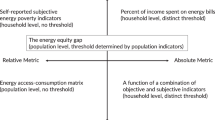

Studies have found that energy-insecure households commonly engage in several coping mechanisms simultaneously to address the energy burden. Carley et al. found that households use financial coping strategies while also engaging in unsafe and dangerous measures such as abstaining from grocery shopping, postponing doctor visits, or seeking warmth through methods other than central heating3. The study found that households with deficient infrastructure were more likely to use every coping strategy available, which aligns with the findings of Graff et al. that households with poor housing conditions are more likely to experience energy insecurity12. Cong et al. looked at the outdoor temperatures at which low-income and high-income households turned on their cooling systems and measured the difference in turning points. They found an energy equity gap: Low-income households are more likely to turn on their cooling systems at higher temperatures during the summer than high-income households, thereby facing heat-related risks4.

Based on a series of interviews, Hernández explored the economic, physical, and behavioral dimensions of energy insecurity6. The study found that households experiencing energy insecurity face financial hardship from utility bills, encounter limited housing options, and engage in behavioral coping strategies to conserve energy as a result of the financial and housing challenges6. As part of the interviews, Hernández described a participant’s definition of catch-22, which happens when households that lack economic self-sufficiency cannot access safety net benefits6. A subsequent study by Simes et al. addressed the burdens imposed on individuals who experience energy insecurity and seek energy assistance services, coining the term vigilant conservation7. They found that participants experiencing energy insecurity and looking for assistance faced both cumulative and administrative burdens, that is, the burden to conserve, save, and be environmentally responsible and the burden to learn about the assistance programs and apply or reenroll, respectively1,7. This study adds to the limitations that energy assistance programs face in attempting to reach energy-insecure households, and even when they do, it proves difficult for applicants to benefit from them fully.

Overall, the limited research on energy insecurity has found that using a material hardship, such as an income or asset limit, approach to determine a household’s capacity to satisfy their energy needs fails to capture the full scope of energy-insecure households in the United States. Based on the inflection temperature and a sample of 4577 households, Cong et al. found 86 energy poor and 214 energy-insecure households, compared to only 141 energy-insecure households identified using the income-based energy poverty metric, showing how the use of the latter can exclude households that are energy poor4. Carley et al. showed that fewer people apply for government assistance programs than implement energy-limiting behavior strategies, which could result in lower utility bills, and consequently being excluded from the economic-based indicator at the expense of their financial and physical well-being3. Hernández’s three dimensions of energy insecurity showcased how behavioral coping strategies related to energy use result from households facing economic and physical challenges and can lead to many households not being eligible for (or being hidden from) energy assistance6. Even those that qualify for these assistance programs may be deterred from applying due to the associated administrative burden; the perception of limited programmatic resources combined with the assumption that others may be facing greater hardship; and unwillingness to disclose details of their financial situation or misinterpretation of eligibility requirements16,17.

Energy-limiting behavior can be an effective strategy to lower electric utility bills and thereby reduce the energy burden. In doing so, households may not appear to be energy burdened, or may even seem energy efficient; however, these metrics may fail to capture the everyday struggle of these households, who must choose which necessities to go without to afford their utility bills. In this work, we explore the relationship between energy insecurity and the energy-limiting behaviors of households that may slip through the programmatic net and not receive energy or bill assistance. We investigate the role that battery energy storage systems (BESS) and rooftop solar photovoltaics (PV) could play to alleviate some of the burdens of energy-insecure households if deployed as part of a bill assistance program. By directly supporting energy affordability and energy security, such an intervention would allow recipients to live safely and comfortably in their homes while also being able to afford necessities like food and medicine.

To investigate these relationships, we compare the simulated annual energy use and utility bills of a typical household, as informed by the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s 2020 Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS)15, to that same household employing severe energy-limiting behaviors. We then compare the energy and bill savings from these behavioral changes to the savings provided by adding a 7.5-kW rooftop solar array and a 13.5-kWh energy storage system, or a typical residential PV-BESS system18. Previous work by the authors explored targeted energy burden reduction measures based on household characteristics and climate region in terms of the measure’s cost-effectiveness19 and tailored rooftop solar and energy storage system sizing according to regional variations in policies, rate tariffs, and climate20. The work of Yozwiak et al. explores rooftop solar as a preventative strategy for energy insecurity using survey data of homes with and without solar regarding their experiences of energy insecurity during the winter months, with a survey sample weighted towards the most southern states21. This analysis builds upon these previous works to explore the impact of energy-limiting behavior as a non-traditional energy burden reduction measure, comparing it to a solar plus energy storage system as a control measure. By comparing the energy savings of extreme energy rationing to those of energy storage and rooftop solar interventions, this work quantifies the extent to which targeted, thoughtful programmatic interventions could remediate the need for energy-insecure households to ration their energy use. To this end, simulations are conducted for each of the five climate regions in the U.S., as well as two different time-of-use (TOU) rate structures, to explore whether these factors impact the bill savings of the energy-limiting behaviors or the renewable system. The results of the analysis show that severe energy-limiting behavior offered on average 42% energy and utility bill savings compared to 22% energy savings and 29% bill savings from renewable systems. These findings highlight the potential role that residential rooftop solar and behind-the-meter energy storage could play as long-term intervention strategies to minimize the extent to which households must engage in unsafe levels of energy-limiting behaviors.

Results

To investigate the effect of energy-limiting behavior on household energy use and explore the role that residential energy storage and rooftop solar could play in providing utility bill relief to energy-insecure households, a series of economic optimizations were performed using the Graph-Based Optimization Modeling Language (GBOML). The simulated load profiles were devised to be representative of the average household in each climate region; however, the authors acknowledge that these profiles cannot be perfectly realistic. In light of this limitation, the household energy and bill savings from the PV-BESS and the energy-limiting behaviors are presented as percentages in Fig. 1, rather than in kWh and dollars. It is apparent from these results that energy-limiting behavior can substantially reduce both energy use and utility bills. The average energy and utility bill savings from the energy-limiting behavior modeled in this analysis were 42%, compared to 22% energy savings and 29% bill savings from the renewable system. The savings potential for both measures varies by climate region. The energy and bill savings of the measures approximately scale consistently between regions, except for the mixed-dry and hot-humid regions, where the energy savings potential of the renewable system increases more dramatically than the energy-limiting behavior. This is likely due to a combination of warmer climates reducing the heating demand of the household and therefore the savings potential of adjusting the household heating setpoint, as well as increasing the solar generation due to the higher irradiance in these regions.

Utility rate design can also affect the savings potential of both energy-limiting behaviors and renewable systems, depending on whether energy-shifting behavior, energy generation, and energy arbitrage opportunities align favorably with pricing signals. Simulations were performed for two representative TOU rate designs to reflect commonly available rate structures: a two-tier seasonal rate and a three-tier yearly rate. The variation of simulated energy and bill savings from the same measures due to differences in TOU rate structure was negligible; the average difference in energy savings was less than 1% and the average difference in bill savings was 3.1% from the renewable system and 1.63% from the energy-limiting behavior.

A substantial contribution to the savings from energy-limiting behavior is the result of adjusting the thermostat setpoint of the household +8 degrees for cooling and −10° for heating compared to the RECS average temperature setpoints. The impact of these adjustments can be seen in Fig. 2 for the very cold climate region. The outside temperature, set by Typical Meteorological Year 3 weather data for the location, is shown in yellow on these plots. The temperature setpoint range of each household can be seen in the green band of indoor temperatures, achieved by the heating (red, lower) or cooling (blue, upper) system. The increased range in allowable temperatures leads to fewer instances where the HVAC system is called upon to regulate the indoor temperature, dramatically reducing the HVAC load.

Cool ON and Heat ON, or whether the cooling or heating system is operating, are both binary. To represent this visually, these data were scaled and skewed to be simultaneously visible at the bottom of each plot. A flat or zero line represents days on which the heating or cooling system was never called upon; spikes on the plot represent individual days in which the HVAC system was called upon at least once; and horizontal bars represent a set of sequential days where the HVAC system was called upon each day.

These adjustments reduce annual HVAC demand considerably but also represent a substantial reduction in home comfort and can even be considered unsafe for vulnerable populations such as children, older people, and those with medical conditions. However, households facing energy insecurity without access to programmatic assistance may be forced to resort to such measures. Unlike the average household, whose indoor temperature is relatively consistent throughout the year, the comfort and safety of the energy-limited household are highly dependent on the day’s weather. This highlights that energy-insecure households are more vulnerable to extreme temperatures and are more likely to suffer adverse health impacts from heat waves and cold snaps because they cannot afford to pay more in utility bills.

Discussion

The results of this analysis quantify the substantial impact that energy-limiting behaviors can have on reducing household energy use and utility bills. The behaviors modeled in this analysis resulted in an average energy and bill savings of 42%, dramatically reducing the likelihood that such a household would be captured by high energy burden or high energy use intensity thresholds designed to target households in need of programmatic assistance. Although they appear on paper as energy-efficient, these households struggling to pay their utility and living expenses are likely to fall through some of the traditional programmatic nets designed to provide much-needed relief. Without assistance, energy-limiting households face a considerable toll in managing their utility bills. Extreme temperature setpoints jeopardize the health and safety of the occupants, creating environments of excess moisture prone to mold growth and poor air quality. Uncomfortable indoor temperatures can disrupt sleep patterns and make it difficult for adults to work remotely and for children to complete their homework. Rationing appliance usage and constantly weighing the costs to operate with the benefits of use creates a tremendous cycle of stress for households already managing financial hardship.

Residential rooftop solar and behind-the-meter energy storage were investigated as potential mechanisms to alleviate the need for these households to engage in energy-limiting behaviors by providing energy and bill savings in their stead. A typical 7.5-kW solar array and a 13.5-kWh energy storage system were simulated to provide an average of 29% bill savings and 22% energy savings. Such a system is therefore likely to offset approximately two-thirds of the utility bill reduction that households could achieve through severe energy-limiting behavior, depending on the climate region. While a system is therefore unlikely to be capable of completely alleviating a household’s stress related to bill management, providing access to an alternative bill savings mechanism that does not require the household to ration or substantially curtail their energy use could enable struggling households to live in their homes with comfort and dignity. Note that achieving this outcome is not anticipated to result in substantial bill savings post-intervention, which is the typical metric of a successful energy program. Rather, the objective is to cover the cost of comfort, safety, and dignity that are so often sacrificed by energy-insecure households. This may be one reason why recent studies such as22 have begun to show that anticipated savings from energy efficiency and weatherization programs fall short of projections. This is also consistent with recent studies of the impact of rooftop solar and energy storage adoption on increasing household energy demand, for the same reason23,24.

Connecting financially burdened households with energy and bill assistance is difficult. It is all the more challenging when a subset of those in need of such assistance do not appear to have high utility bills. It is therefore necessary that programs recognize this limitation and take measures to design programs capable of both identifying these gaps and ensuring that eligibility criteria do not exclude them. There may be many ways to better identify energy-limiting households; however, one potential approach is to allow for self-identification of need with little or minimally invasive requirements to substantiate that claim. Eligibility criteria can be adjusted to accommodate case-by-case assessments of meeting income cutoffs, as strict thresholds for eligibility may inherently limit a program’s ability to provide relief.

Traditional bill assistance programs can be incredibly valuable to those acutely struggling to pay their utility bills. However, their impact is temporary, as bill assistance does not address the factors that contribute to its need. Programs designed to address a particular contributor to unaffordable utility bills, such as the WAP, are better equipped to provide long-term benefits to households. The factors that contribute to energy insecurity are numerous; therefore, no single program (e.g., WAP) is effectively designed to provide assistance for all those in need. The authors recommend that program designers, utilities, regulators, and advocates look beyond traditional bill relief mechanisms and leverage the substantial, long-term value that renewable energy systems such as rooftop solar and energy storage can provide to energy-insecure households, the electric grid, and national decarbonization goals.

A centralized, phased, and holistic approach to energy assistance that builds from the strengths of both LIHEAP and WAP may be an effective strategy to address these systemic issues. The initial phase of such a program can be designed to target the acute symptoms of energy insecurity or energy poverty; this would be in the form of immediate, easily accessible bill relief. The second phase could focus on addressing the cause of energy insecurity or poverty for that household; this could include a home energy audit to identify energy inefficiencies and problems with building envelope integrity, followed by a prescriptive approach to address these concerns. More robust, but still minimally burdensome, eligibility checks that recognize the masking effect of energy-limiting behaviors could be employed before proceeding with this work, traditionally performed by the WAP. The energy audit offering should be accessible to anyone who seeks initial assistance. This ensures that even those who do not receive weatherization assistance can benefit from the lessons learned and targeted information afforded by the energy audit. The final stage of the program could then be designed to help households explore other energy-saving measures, such as rooftop solar and energy storage, as well as available funding mechanisms. Some of the most critical obstacles preventing programmatic assistance from reaching those in need are that households do not know they exist, do not believe they are eligible, or do not trust those running the program or the promises being made. This approach would strive to address these key challenges at every stage of program design and implementation.

Methods

This paper aims to investigate the extent to which energy-limiting behavior can mask energy burden and whether residential rooftop solar and behind-the-meter energy storage could provide comparable energy and bill savings, enabling occupants of energy-limiting households to live more comfortably in their homes. To achieve this, the simulated annual energy use and electric utility charges for an average household are compared to those of a severely energy-limiting load profile. This energy-limiting profile was created to serve as a model of reasonably extreme behavior, or an upper limit to behavior-driven energy savings, to provide an anchor for policy and programmatic discussions. The savings provided by the energy-limiting behaviors are then compared to those from a 7.5-kW rooftop solar array and a 13.5-kWh energy storage system, operated to provide TOU bill savings while holding 20% of its capacity in reserve in case of an outage. This charge-discharge strategy uses the battery for energy arbitrage, charging when prices are low and discharging when prices are high. The battery can also be charged by the rooftop solar array, increasing the on-site consumption of renewable energy generation and providing additional savings. The system is assumed to operate under a net metering agreement where excess solar generation can be exported to the utility to offset the monthly utility bills. Note that not every state guarantees net metering arrangements for rooftop solar. Some states offer reduced savings potential by compensating exported electricity at less than the retail rate. Conversely, some have begun to extend net metering to energy storage systems, increasing potential savings. A more detailed discussion of state-specific policies and tariffs and their impact on the benefits of solar and storage adoption can be found in the authors’ previous work20.

A series of case studies was structured to capture the potential variation in energy and bill savings for households across the U.S. Solar irradiance, heating and cooling demand, and electric utility rates differ substantially between climate regions. Five case studies were performed to capture the differences in heating and cooling demand as well as solar irradiance, one for each climate region in the U.S. The cities selected to represent the five climate regions were (1) Portland, Oregon: marine, (2) New York, New York: cold/very cold, (3) San Diego, California: mixed-dry/hot-dry, (4) Cincinnati, Ohio: mixed humid/hot-cold, and (5) Orlando, Florida: hot humid.

To account for differences in electric utility rates, each case study was simulated for two representative TOU rates (Table 1). TOU rate structures were chosen for this analysis for two reasons: (1) the time-varying rate provides the opportunity for bill savings for those with PV and BESS systems, and (2) utilities are increasingly using TOU rates to encourage the shifting of energy use to times of reduced grid stress. The rates were created to capture two common TOU structures: (1) a seasonally varying rate with peak- and off-peak windows and (2) a consistent yearly rate with a peak-, mid-, and off-peak window. A review of the time-variable rates presented in the Federal Energy Management Program’s dataset informed the peak- and off-peak windows of the seasonally varying rates25. The windows for the yearly rate were based on Portland General Electric’s time-of-day rate26. To mitigate variation between case studies and inevitable rate changes in subsequent years, these representative rates were not scaled to actual utility prices for the individual case studies; rather, a ratio of 1:3 was used for the seasonal rate, meaning that the peak price was three times the off-peak price, and a ratio of 0.6:1:3 was used for the yearly rate. Resulting volumetric energy charge savings (or per-kWh savings) are reported in percentages for comparability across the cases.

The 2020 RECS, which combines a nationally representative household energy survey dataset with corresponding heating, cooling, and end-use data from energy suppliers, was used to inform the modeling parameters of both the base representative and energy-limiting case in this analysis27. A representative household load profile was simulated based on the average RECS response to heating and cooling temperature setpoints as well as the usage frequency of the following end-use loads: clothes washer and dryer, dishwasher, oven, and cooktop. The temperature setpoints were used to model the heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) load of a normally insulated house with central air conditioning and electric resistance heating, using the power system simulation software GridLAB-D for each climate region to capture the variation in HVAC demand28. Note that the R-values, or insulation ratings, associated with the normal thermal integrity profile in GridLAB-D are Rroof: 30.0, Rwall: 11.0, Rfloor: 19.0, Rdoors: 3.0, Rwindows: 1/0.6, air change per hour: 1.0. The end-use load profile of the representative household was created using ResStock timeseries data for end-use loads29. The ResStock end-use dataset is based on empirical submeter data from six different sources and calibrated using numerous surveys, studies, and advanced metering infrastructure data to accurately reflect real-world home energy use patterns30. These data are organized by end use, at 15-min resolution, and include clothes washer, clothes dryer, dishwasher, water heater, indoor lighting, range oven, refrigerator, and plug loads. Individual end-use load profiles that most closely aligned with the average frequency of use reported in the RECS data, shown in Table 2, were selected from the available ResStock data to make these load profiles. For the water heater, indoor lighting, plug, and refrigerator loads, where usage frequency is either not relevant or unavailable, relatively average load profiles were selected. The specific end-use load profiles are described in the Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 3 shows a snapshot of this load profile for the representative household in the Mixed-Humid climate for a week in May. This stack plot shows that the HVAC system (steel blue) was used sparingly at the beginning of this week, and then consistently in the latter half of the week, suggesting comfortable spring temperatures transitioning to warmer summer temperatures. The household also appears to have done laundry early in the week (turquoise and brown) and made a handful of home-cooked meals (red), which required them to run the dishwasher (teal). Refrigerator (gray/blue), plug loads (green), and lighting (yellow) are relatively consistent, while showers, laundry, and dishwasher use appear as relatively small or large spikes in water heater load (dark blue).

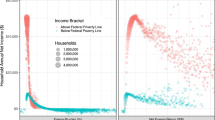

The base case household load profile was created by summing the individual end-use ResStock load profiles that aligned with the average RECS responses for weekly appliance use. The energy-limiting end use load profile was created by scaling those average end use loads based on the average responses from income brackets that show evidence of energy-limiting behavior, corresponding to the minimum RECS response, which is observed as a dip in the upward trajectories of the RECS data plotted in Fig. 4. For the 2020 RECS data, respondents of annual income brackets between $9999 and $14,999 appear to show energy-limiting behavior that opposes the trend of increasing consumption by income, as seen in Fig. 4. Across the different appliance end uses, the energy-limiting income brackets averaged approximately one fewer use per week compared to the average across all income brackets. For example, average dryer use was reported to be 4.09 times per week across all income brackets, but was as low as 3.1 for households with incomes between $12,500 and $19,999. The load profile scaling for the dryer was therefore calculated to be as in Eq. (1).

The ResStock end-use load profiles do not necessarily conform to a strict usage-per-week schedule; instead, these datasets are more reflective of the variable nature of home energy use. Therefore, to simulate energy-limiting behavior, this direct scaling method was chosen to ensure the reductions in energy use were proportional to the difference in RECS responses without imposing unrealistically regimented load profiles. Table 2 presents those values, the income bracket associated with the lowest average response, and the energy-limiting to average response ratio. The temperature setpoint adjustment associated with severe energy-limiting behavior was modeled to be +8 degrees for cooling and −10° for heating, associated with the lowest and highest statistically significant RECS response for thermostat setpoint, respectively. These setpoints represent a worst-case energy-limiting profile as a benchmark for the greatest energy savings an energy-insecure household is likely to obtain through energy rationing.

Once the base case representative load profiles were created for each climate region, GBOML was used to economically optimize the electricity dispatch of the households in each case study, at the hourly resolution31. The economically optimized dispatch strategy would be akin to a household selecting a ‘time of use bill management’ or similar setting on their battery management system. Normalized irradiance data were collected from simulations of a 1-kW PV array in each of the five climate regions using the System Advisor Model32; these data were scaled to the PV capacity of 7.5 kW to give the electricity generated at each timestep. Figure 5 depicts the relationships between the parameters used to create the model (black text in the figure) and variables used during optimization (blue text). Two variables in the model are intrinsic to their node: (1) the state of charge of the battery and (2) the price paid for utility electricity. Every other variable in the model is exchanged between nodes during the simulation, to be optimized according to the model’s objective.

The objective function used to simulate the economic dispatch of the system is simply to minimize the price paid for electricity:

where

according to two hyperedge interconnection constraints that must be maintained at each time step, \(\left(t\right)\): (1) to balance the energy flow in the system and (2) to allow excess PV generation to be exported to the grid for compensation, consistent with a net metering agreement. Those constraints are:

and

Three simulations were performed for each case. The first (base case) simulation was performed to determine the energy use and utility charges for an average house with no system. The second simulation was performed to determine the energy use and utility charges for an average house whose occupants engaged in energy-limiting behaviors. The third was performed for the average house if it had a 7.5-kW PV array and a 13.5-kWh BESS to reduce its energy use and provide savings on utility charges. A visual description of this methodology is presented in Fig. 6.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, its supplementary information, and the accompanying datahub page: https://doi.org/10.25584/256846333. The dataset includes the scripts used to process the ResStock data (.py), perform the GridLAB-D simulations (.glm), perform the GBOML simulations (.py and .txt), process the results (.py), and any files required for inclusion (.csv).

References

Adams, J. A., Carley, S. & Konisky, D. M. Utility assistance and pricing structures for energy impoverished households: a review of the literature. Electr. J. 37, 107368 (2024).

Brown, M. A., Soni, A., Lapsa, M. V., Southworth, K. & Cox, M. High energy burden and low-income energy affordability: conclusions from a literature review. Prog. Energy 2, 42003 (2020).

Carley, S., Graff, M., Konisky, D. M. & Memmott, T. Behavioral and financial coping strategies among energy-insecure households. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2205356119 (2022).

Cong, S., Nock, D., Qiu, Y. L. & Xing, B. Unveiling hidden energy poverty using the energy equity gap. Nat. Commun. 13, 2456 (2022). vol.

Graff, M., Konisky, D. M., Carley, S. & Memmott, T. Climate change and energy insecurity: a growing need for policy intervention. Environ. Justice 15, 76–82 (2022).

Hernández, D. Understanding ‘energy insecurity’ and why it matters to health. Soc. Sci. Med. 167, 1–10 (2016).

Simes, M., Rahman, T. & Hernández, D. Vigilant conservation: how energy insecure households navigate cumulative and administrative burdens. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 101, 103092 (2023).

Agbim, C., Araya, F., Faust, K. M. & Harmon, D. Subjective versus objective energy burden:a look at drivers of different metrics and regional variation of energy poor populations. Energy Policy 144, 111616 (2020).

Hernández, D. & Laird, J. Surviving a shut-off: U.S. households at greatest risk of utility disconnections and how they cope. Am. Behav. Sci. 66, 856–880 (2022).

Baker, S. H., Carley, S. & Konisky, D. M. Energy insecurity and the urgent need for utility disconnection protections. Energy Policy 159, 112663 (2021).

Huang, L. & Nock, D. Estimating the income-related inequality aversion to energy limiting behavior in the United States. Energy Econ. 136, 107716 (2024).

Graff, M., Carley, S., Konisky, D. M. & Memmott, T. Which households are energy insecure? An empirical analysis of race, housing conditions, and energy burdens in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 79, 102114 (2021).

Harker Steele, A. J. & Bergstrom, J. C. Brr! It’s cold in here” measures of household energy insecurity for the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 72, 101863 (2021).

Cong, S., Ku, A. L., Nock, D., Ng, C. & Qiu, Y. L. Comfort or cash? Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on energy insecurity and energy limiting behavior in households. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 113, 103528 (2024).

U.S. Energy Information Administration. 2020 Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS). (U.S. Department of Energy, Washington, 2022).

Carrión, D. & Hernández, D. Heatwaves and hardship: Shortcomings and solutions for enhancing the low income home energy assistance program to mitigate extreme heat and energy insecurity. Electr. J. 37, 107440 (2024).

Graff, M. & Pirog, M. Red tape is not so hot: asset tests impact participation in the low-income home energy assistance program. Energy Policy 129, 749–764 (2019).

Barbose, G., Elmallah, S. & Gorman, W. Behind-the-Meter Solar+Storage: Market Data and Trends. (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 2021).

Kerby, J., Hardy, T., Twitchell, J., O’Neil, R. & Tarekegne, B. A targeted approach to energy burden reduction measures: comparing the effects of energy storage, rooftop solar, weatherization, and energy efficiency upgrades. Energy Policy 184, 113867 (2024).

Kerby, J. & Tarekegne, B. A guide to residential energy storage and rooftop solar: State net metering policies and utility rate tariff structures. Renew. Energy Focus 49, 100566 (2024).

Yozwiak, M. et al. The effect of residential solar on energy insecurity among low- to moderate-income households. Nat. Energy 10, 569–580 (2025).

Papineau, M., Rivers, N. & Yassin, K. Household benefits from energy efficiency retrofits: implications for net zero housing policy. Energy Econ. 143, 108245 (2025). vol.

Qui, Y., Kahn, M. E. & Xing, B. Quantifying the rebound effects of residential solar panel adoption. J. Env. Econ. Manag. 96, 310–341 (2019).

Deng, G. & Newton, P. Assessing the impact of solar PV on domestic electricity consumption: exploring the prospect of rebound effects. Energy Policy 110, 313–324 (2017).

Federal Energy Management Program. Demand Response and Time-Variable Pricing Programs Search. (U.S. Department of Energy, 2024).

Portland General Electric. “Time of Day,” Portland, 2024.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. 2020 Residential Energy Consumption Survey: Consumption and Expenditures Technical Documentation Summary. (U.S. Department of Energy, Washington, DC, 2023).

Chassin, D. P., Schneider, K. & Gerkensmeyer, C. GridLAB-D: an open-source power systems modeling and simulation environment. 2008 IEEE/PES Transmission and Distribution Conference and Exposition, 1–5 https://doi.org/10.1109/TDC.2008.4517260 (2008).

Wilson, E. J. H. et al. End Use Load Profiles for the U.S. Building Stock. (National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, CO, 2022).

Wilson, E. J. H. et al. End-Use Load Profiles for the U.S. Building Stock: Methodology and Results of Model Calibration, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification. (National Renewable Energy Lab., Golden, CO, 2022b).

Miftari, B., Berger, M., Djelassi, H. & Ernst, D. GBOML: graph-based optimization modeling language. J. Open Source Softw. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.04158 (2022).

National Renewable Energy Laboratory. System Advisor Model (SAM). Version 2022.11.29. (Golden, CO, 2023).

Kerby, J., Rucavado Rojas, D. & Tarekegne, B. Dataset For: Rooftop Solar and Energy Storage Programs Can Remediate Energy-limiting Behaviors of Energy Insecure Households. (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, 2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the funding from the Office of Electricity, U.S. Department of Energy. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory is operated for the DOE by Battelle Memorial Institute under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, and writing of the original draft. D.R.R. contributed to the writing of the original draft. B.T. contributed to the conceptualization, supervision, and review and editing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Diederik Coppitters, Maya Papineau and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Martina Grecequet. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kerby, J., Rojas, D.R. & Tarekegne, B. Rooftop solar and energy storage programs can remediate energy-limiting behaviors of energy insecure households in the United States. Commun Earth Environ 6, 621 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02517-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02517-5

This article is cited by

-

The role of thermostats and human behaviour in residential temperature settings in the USA

Nature Energy (2026)

-

Rooftop solar and energy storage programs can remediate energy-limiting behaviors of energy insecure households in the United States

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)