Abstract

Landslides regulate the height of mountains by releasing potential energy and reducing topographic relief. Yet, relief also limits the dimensions of small, frequent landslides in turn. But how local topography, lithology, and climate influence the size distribution and hazard of Earth’s largest terrestrial landslides remains unclear. Here we use Bayesian regression to estimate these effects on landslide volume, drawing on a worldwide sample of 411 cases, each involving > 1 km3. Nearly two third of their total volume is volcanic and sedimentary rocks within 50 km of active fault zones, clustered in actively uplifting mountain belts and on volcanic plateaus. Volumetric estimates vary most distinctly with dominant topographic setting, regardless of local relief, general rock type, or contemporary climate. These largely negligible effects indicate that volume scaling statistics fail to capture differing bulk lithological properties, let alone a detection bias due to climatic controls on land cover, weathering, or erosion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The idea that topographic relief cannot grow indefinitely and must be limited by material strength and erosion has posited mass wasting, especially landsliding, as a natural and ubiquitous constraint on mountain growth1. However, tectonic activity and local topography alter crustal stress fields, fracture patterns, and the arrangement of major rock-mass defects, which in turn may constrain the size of slope failure2. Both these concepts are intuitive and rooted in physics-based models of slope stability, but empirical tests have considered small landslides (usually involving less than 1 million m3) only, supporting the notion that fracture spacing in dissected bedrock determines the size of frequent slope failures3,4. How such structural or topographic controls play out for larger, and commensurately rarer, landslides remains unexplored, especially with variations in rock type and climate that affect weathering, erosion rates, and thus the longevity of landslide evidence. In general, the size scaling of landslides is modelled statistically as a power-law tail of a probability distribution fitted to mapped footprint areas of thousands to hundreds of thousand landslides that were triggered during a single earthquake or rainstorm in recent times5,6,7,8,9. The modes, or “roll-overs” of these fitted distributions—beyond which power-law scaling approximately sets in—might mark size-dependent changes in cohesive strength, soil moisture, topographic constraints on runout, detection bias, or a combination thereof4,10. Whether similar mechanistic interpretations are valid for very large landslides with volumes >>106 m3 is unknown because of fewer samples and more statistical noise. Nonetheless, models of how landslide volume scales with footprint area, for example, remain a foundation of estimating hillslope erosion, mass fluxes, geomorphic work, and hazard. While this scaling may differ between soil and bedrock landslides11, other possible influences beyond material types have been hardly explored. Overall, the large body of statistical landslide studies has mostly ignored the very large landslides that affect several square kilometres or involve at least hundreds of millions of cubic metres. Hence, we know very little about whether and how key controls on slope stability, such as topography, rock type, or climate affect the size of the largest terrestrial slope failures, each involving >1 km3. This size distribution is essential for estimating hazard and risk levels, and hence, our knowledge base about exceptionally large landslides remains curtailed.

Yet, large landslides leave distinct footprints on the surface of the Earth, several planets, and moons12,13. Unlike smaller, shallow landslides with short-lived geomorphic impacts, scars and deposits of large landslides can remain recognisable in the landscape for up to several million years14. Large landslides are effective processes of shallow lithospheric fragmentation15,16, reshape entire hillslopes by releasing potential energy in response to tectonic uplift, river and glacier erosion, and topography-induced stresses17, and form major point sources of sediment and biogeochemical fluxes18. Large slope failures can lower mountain peaks, shift drainage divides19, dam rivers20, and disturb the hydrological balance, sediment calibre, and transport capacity of streams21,22. The collapse of volcanic flanks can decompress magma chambers and promote eruptions23, while major coastal landslides can cause tsunamis with local run-up of hundreds of metres24. Catastrophic landslides can disturb ecosystems by driving biodiversity25, alter the species composition and genetic base of aquatic organisms through interruption of valley networks26, and foster the colonisation of islands by new species27. Gauging the magnitude and recurrence of all these impacts requires a solid knowledge of the size distribution of large landslides, as single catastrophic failures may involve volumes exceeding those of tens of thousands of smaller landslides triggered by individual rainstorms or earthquakes.

Widely reported preconditions for giant slope failure include high topographic relief17, mechanically weak rocks28, though mostly combined with hard-on-soft rock contacts29,30,31,32,33; low-strength layers34,35,36; weathered fault zones33,37; and unfavourably oriented rock-mass defects16,38,39. Still, more systematic appraisals of how these mostly topographic and lithological traits affect the size of Earth’s largest terrestrial landslides have been elusive. This knowledge gap has persisted because local topographic relief is tied to both geomorphic history and geological structure, while data collated from different inventories are few and often lump landslides of varying age, degree of preservation, and mapping protocol. The preservation, detection, and mapping of large landslides might depend on the contemporary climate that governs the amount and dynamics of ice, snow, and vegetation cover, and thus the types and rates of weathering and erosion that landslide evidence is exposed to. Hence, it is plausible, though untested, that topography, rock type, and climate influence the size distribution of the largest of slope failures. If so, we should be able to detect these influences in statistical model parameters similarly to what has been proposed for much smaller landslides4,10. Here, we use a Bayesian extreme-value model with a multi-level setup to overcome the limitations of small sample size, while acknowledging the often overlooked volumetric measurement uncertainties, as well as a possible climate-dependent mapping bias. We compare the derived median landslide volumes with those of a multi-level quantile regression that considers landslide footprint area and mean local relief as additional predictors. Both models estimate jointly and consistently the relative effects of local topographic setting, rock type, and climate on landslide volume, and incorporate the wealth of prior knowledge about landslide size scaling4.

Results

Global distribution

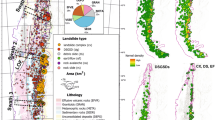

We learn our models on an inventory of 411 landslides with volumes >1 km3 that we simply term “landslides” here; these have been detected on all continents except for Australia and Antarctica (Supplementary Data 1). About half these landslides have been published in international peer-reviewed journals and monographs since a first global review of large terrestrial landslides17, whereas a fifth have been identified since, including those from a randomised search covering 10% of all land-surface area (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Data 1). More than 95% of this total known landslide volume resides in Cenozoic mountain belts, or only 1% of Earth’s surface with a local relief >300 m (Fig. 1; see Methods). The remainder is in tectonically rejuvenated orogens such as the Tien Shan of Central Asia39 or reactivated continental rift flanks with young volcanoes40,41. In terms of volume moved, rock slides and rock avalanches were the dominant (62%) landslide type42, followed by volcanic debris avalanches (30%), rockfalls and rock slide-earth flows (6%), and debris flows (1%; Supplementary Fig. 1). The largest reported terrestrial landslide with a recognisable deposit is the Las Cumbres debris avalanche in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt43, with an estimated volume of 60 km3 (Fig. 1). Reported volumes of older deposits especially can be vague, and range between 37 and 50 km3 for one of the world’s largest Pleistocene earth-block slides at Baga Bogd, Mongolia44; similarly, the Seymareh rock avalanche in Iran has published34,45 volume estimates between 20 and 44 km3.

a Map of binned abundance with respect to local relief. b Distribution of mean local relief (within 15 km of landslides; blue) and fraction of total volume by topographic setting (orange); ESC – escarpment or anticline, FAULT – fault-bounded mountain front, GLAC – glacial valley, FLUV – river valley, VOLC – volcanic edifice. c Mean local relief by dominant rock type: PLUT – plutonic, META – metamorphic, VOLC – volcanic, VOLC + SED – volcanic and sedimentary, SED – sedimentary. d Mean local relief by climate zone of Köppen-Geiger classification87: A – tropical, B – dry, C – temperate, D – continental, E – polar/mountain. Boxes span interquartile ranges; whiskers are maximum and minimum values; thick blue lines are medians; numbers show sample size.

Earth’s largest landslides form clusters, and more than 60% of all mapped deposits (and total volume) are within 50 km of at least one another, especially in the Karakoram37, Himalayas46, Northern Chile29, Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt47, Central Andes33, and Kamchatka48. Many of these clusters include numerous smaller landslides, though each of these covers several km2 still. About a quarter of the total non-volcanic landslide volume is in deposits residing in the same valley (sometimes forming pairs), such as the Flims and Tamins landslides in the Rhine valley, Switzerland49; the Bonneville and Red Bluff landslides in the Columbia River valley, USA50; and the Karakudjur River landslides, Kyrgyzstan39. Many of these locations are sparsely populated such that we can exclude a reporting bias in this clustering. Instead, conditions favouring large-scale slope failure are not limited to single hillslopes, but can instead involve several nearby locations. Many landslides dot the Rañileuvú Valley, Central Andes of Argentina33; the Yeso Valley, Central Andes of Chile33; the Azapa Canyon, Atacama Desert of Chile29; and the upper Indus River, Karakoram, Pakistan20. Overlapping deposits of multiple debris avalanches from single volcanoes show that conditions leading to flank collapse may be regained even after prior large-scale failure51. Such reactivated or repeated instabilities are also common away from volcanoes39, though rarely with volumes >1 km3. One exception is the 15 km3 Caquilluco rock-avalanche complex in Peru52, which contains deposits of several landslides that happened between ~600 and 110 ka.

Topographic setting

We chose a multi-level Generalised Pareto distribution (GPD) to model landslide volumes above a fixed threshold of 1 km3, while taking into account often ignored measurement uncertainties (see Methods). We obtained a heavy-tailed fit (shape parameter k > 0 being >95% probable), with the 10% largest deposits holding more than half of the total volume. Hence, we use median volume to characterise this and all other distributions. To capture the landscape context of each landslide, we distinguished between five dominant topographic settings: (1) large, mostly free-standing volcanic edifices with subdued surrounding topography; (2) active fault-bounded mountain range fronts with low-order drainage basins; (3) river valleys with mostly rectilinear hillslopes; (4) trough-shaped glacial valleys with distinct ice-shaped landforms; and (5) low-relief escarpments without any major faults or substantial seismic activity. We find that including these topographic settings in our GPD model alters the size scaling of landslides credibly (meaning here that non-zero differences between topographic settings have a > 95% posterior probability), and well beyond both data and model uncertainties (Fig. 2). This multi-level model also outperforms a simple GPD fit to all landslide data without acknowledging their topographic setting. The posterior estimates of scale parameter σ mark the landslide sizes beyond which inverse power-law scaling sets in, and vary credibly across the topographic groups. The shape parameter k, which is the inverse of the power-law exponent in landslide scaling studies4, remains indistinguishable between the different topographic settings instead (Fig. 2c). Volcanoes and low-relief escarpments had the highest and lowest median landslide volumes (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables 1-3), and also the largest and lowest fractions of the total volume, respectively (Fig. 1b).

a Bayesian multi-level fit of generalised Pareto distribution (GPD); lines are posterior medians and shades are 95% highest density intervals (HDIs), in which predictions occur with 0.95 probability; p is the exceedance probability. b Samples from the joint posterior distributions of shape parameter kj and scale parameter σj of the GPD colour-coded by topographic setting j. c Posterior estimates of kj; white circles are group-level medians and horizontal black bars are group-level 95% HDIs; pooled median (95% HDI) indicated by vertical (dashed) line(s) refers to estimate across all topographic settings. d Posterior estimates of σj.

Topographic setting also credibly alters the relationship between landslide volume and area. For a given area, median volumes are highest in deeply incised river valleys, and lowest at volcanoes rising above plains without major obstacles to runout (Fig. 3). From the corresponding ratios of volume to area, we infer that landslide deposits were more than five times thicker on average in river valleys than on volcanoes; narrow valleys are more likely to confine the runout and footprint areas of landslides. We also observe that volumetric estimates relying on landslide area become more uncertain for larger failures (Fig. 3). This loss of predictive accuracy has gone unrecognised in geometric scaling studies on smaller landslides. Again, the multi-level model that acknowledges different topographic settings outperforms the simpler volume-area model that does not (Supplementary Table 4). Hence, landslide volume-area relationships that rely on lumped data from different study areas11 likely underestimate volumes in river valleys and overestimate volumes at volcanoes, especially.

a Lines show posterior estimates of multi-level regression of median landslide volume conditional on landslide area with intercept αj, slope βj, and Laplace-distributed noise varying per topographic setting j; shades are 95% credible intervals of the posterior predictive distributions that broaden with landslide area. Asterisks refer to standardised data with zero means and unit standard deviations. b Posterior intercepts αj refer to standardised data, and are thus median volumes for mean (log-transformed) landslide areas in each setting; red vertical line is zero (all other symbols and colour codes as in Fig. 2). c Posterior estimates of slope βj.

We emphasise that this discriminatory effect of dominant topographic setting cannot be captured by mean local relief alone, which hardly predicts median landslide volume: regression slopes across all topographic settings are indistinguishable from zero with 95% posterior probability (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Dominant rock type

Steep topography and high erosion rates often expose a narrow range of rock types. Landslides in deeply incised valleys mainly involved metamorphic and plutonic rocks20,33,39, whereas in low relief (<500 m) failures originated almost exclusively from volcanoes51, or in sedimentary rocks featuring weak mudstones38, clays31, marls53 or tuffs30 capped by more competent, often volcanic, rocks. Such landslides abound on the basaltic plateaus of Oregon30 and Patagonia32, and the Caspian Sea coast, Kazakhstan31, where local relief is only 100–200 m (see Methods). Sedimentary and volcanic rocks have been the source of nearly three quarters of the total landslide volume (Fig. 1c).

Regardless, we observe that dominant rock type hardly affects the size distribution or volume-area scaling of Earth’s largest landslides, at least much less than does topographic setting (Fig. 4a–c, Supplementary Table 2). Only landslides involving volcanic rocks stand out credibly such that their deposits are thinnest on average (Supplementary Fig. 4), and largest for a fixed mean local relief (Supplementary Fig. 5). Nearly half of the volume of all landslides derived from volcanic edifices or basaltic tablelands, and volcanic debris avalanches alone have moved about a third (Fig. 1c). These are some of the largest terrestrial landslides, likely because of deeper, bowl-shaped scars and longer hillslopes compared to slope failures elsewhere54. However, the local relief of landslide sites in volcanics is lowest compared to other rock types, and thus discloses little about failure volume directly (Fig. 1b). Similarly, landslides from volcanoes and active fault-bounded range fronts have the highest posterior median volumes (2.8 +0.7/– 0.7 km3 and 2.3 +1.0/– 0.7 km3, respectively), despite a lower local relief compared to fluvial and glacial valleys (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 2). One mechanistic property that volcanoes and fault-bounded range fronts might share is the spacing of major rock-mass defects such as first-order faults or basal décollements. Besides generating large earthquakes with sufficient transient stresses, fault zones are prone to mechanical and geochemical rock-mass weakening, thus preparing likely shear surfaces for giant slope failure. Nearly two third of the total landslide volume is within 50 km of major active fault zones such as the Raikot Fault in the Karakoram20,55; the Alpine Fault, New Zealand56; or the North Anatolian Fault zone, Turkey57 (Supplementary Data 1). In contrast, escarpments without major faults have had the smallest landslides (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Contemporary climate and mapping bias

The distribution of our global landslide sample is likely biased by studies focused on mountainous and volcanic terrain (Fig. 1a). The Tropics, for example, cover 35% of the global landmass, but host only 5% of the reported total landslide volume. In contrast, one fourth of this volume is in arid areas, where sparse vegetation cover reveals more geomorphic evidence. A persistent arid climate may aid to conserve such evidence, and the oldest dated, topographically distinct landslide dates to ~8 Ma at Miñimiñi in the extremely dry parts of northern Chile14. However, we do recognise deposits older than 100 ka in both arid and humid climate zones (Supplementary Data 1). We find that grouping our data by contemporary climate zone hardly affects landslide size distribution and volume-area scaling, as the posterior parameter estimates are largely indistinguishable between climate zones (Fig. 4d, e, Supplementary Figs. 6, 7). Simpler, pooled models that disregard any groups perform equally well than multi-level models grouped by contemporary climate zones (Supplementary Table 4). We infer negligible effects of mean precipitation rates; temperature; snow, ice, or vegetation cover; or commensurate erosion and reworking, at least where these are attributable to contemporary climate. We stress that this negligible role of climate concerns only the size distribution and volume-area scaling. We do not expect that contemporary climate has any mechanistic effect (as cause or trigger), as most landslides occurred well before 1900, and likely during different climates.

Discussion

The abundance of terrestrial landslides in Cenozoic mountain belts17,38,58 supports the notion that high topographic relief and surface uplift20,33 are conducive to large slope failure (Fig. 1a, b). Landslides are prolific in tectonically young or rejuvenated areas, where they might be an effective erosional tool for adapting topography to geology59 (Fig. 5), and rapidly growing volcanic edifices and fault-bounded mountain fronts. In contrast, valleys in older, seismically less active mountain belts may offer only limited volumes of potentially unstable rock masses and rarer triggers60. While pre-Cenozoic mountain belts do have slope failures involving many millions of cubic metres61, only areas with Neogene and younger tectonic rejuvenation feature landslides39. Regardless, the effect of topographic setting on their size distribution and volume-area scaling is unrivalled, whereas dominant rock type and contemporary climate have few, if any, discernible effects. In terms of landslide size, the surrounding topographic setting is more informative than local relief (Figs. 2, 3, Supplementary Fig. 2). Mean local relief alone, if expressed as a local elevation difference17, is a poor predictor of landslide size (Supplementary Figs. 3, 5, 7, Supplementary Table 3). In this regard, our GPD multi-level models also outperform simpler models that make no distinction between topographic settings (Supplementary Table 4).

Tectonically active mountain ranges (Time 1) have landslides in high relief (H), where differing stability thresholds of sedimentary and crystalline rock masses (blue dashed lines) are exceeded (Time 2). Ongoing erosion at balanced uplift reduces H and removes softer sedimentary and volcanic rocks, thus limiting the volumes of landslides. For as long as soft rocks surround the crystalline cores of the mountains, landslides can form in lower topographic relief (Time 3). Lowering of mountain topography below the slope stability threshold of sedimentary rocks and dissection of tablelands into remnant topography limits the size of landslides by reducing the volume of potentially unstable rocks above base level, and trimming major sliding planes (Time 4). Landslides in pre-Cenozoic mountains mostly respond to tectonic rejuvenation and volcanic activity.

The largest landslides occurred on volcanoes or along range-bounding fault zones adjacent to forelands with little topographic obstacles to runout (Fig. 2c). In contrast, more confined mountain valleys may limit the size of slope failure through divide spacing and reaming of major rock-mass discontinuities before they might form extensive failure planes (Fig. 5). Further dissection leads to competing valley incision, narrower divide spacing, and increasingly organised and efficient drainage, which all might reduce the potential for landslides if relief remains moderate. Exceptions confirm this rule, especially where some moving masses overcame major obstacles, such as ridges or interfluves, in their flow path. For example, part of the 1.9 km3 Haldi rock avalanche, Karakoram, swashed over a ~ 500 m high bedrock spur into an adjacent valley55. Other landslides, such as the 27 km3 Green Lake rockslide in Fiordland, New Zealand56, instead undermined and displaced several kilometres of drainage divide. Future work may wish to test whether there is a general relationship between the age of the mountain range and landslide size limits as proposed in Fig. 5, for example by using the relationship between landslide size distribution and proxies of topographic youth, such as exhumation62 or surface uplift rates63. In any case, the conspicuous clustering of many landslides shows that causes and triggers extend beyond the scale of individual unstable hillslopes.

One caveat is that landslide volumes offer lumped estimates of landslide size only. Morphological evidence alone may not warrant that all landslides in our database detached rapidly. Some failures, and especially those in low-relief settings, might have resulted from prolonged, gradual or repeated failure instead; their volume could have accumulated from multiple, but separate smaller failures or failure phases. Starting with minor displacements, incipient cracks in mechanically strong, brittle cap rocks would raise infiltration, groundwater percolation, undrained loading of shear zones, and pore water pressures along more weak and less competent underlying sedimentary rocks that act as aquifers64,65. The rare landslide deposit outcrops that indicate shallow basal décollements and low-angle listric failure planes, however, could equally well support the notion of rapid movement during lateral spreads. Clearer evidence involves breccias and pervasive fragmentation that are diagnostic of rock and debris avalanches15, especially in volcanic settings and along fault-bounded range fronts. There, recurring seismic and volcanic triggers pair up with topographically unconfined runout paths to allow for Earth’s largest terrestrial landslides.

Yet, even these landslides are small compared to their submarine and extraterrestrial cousins. The total volume of the largest hitherto detected terrestrial landslides (1860 km3) is several times smaller than that of individual submarine landslides66,67; some of these off Hawaii68 may have moved more than 5000 km3. Large submarine and extraterrestrial landslides generally have larger source areas than topographically confined terrestrial landslides. Large landslides on Mars, for example, detached from hillslopes that are several kilometres higher and at least an order of magnitude longer than on Earth, as higher topography is necessary to attain critical shear stress under lower gravity13. Yet Earth’s volcanic debris avalanches are more similar to submarine and extraterrestrial avalanches in terms of size and mobility, as their runout is rarely limited by major topographic obstacles. Compared to submarine landslides, terrestrial ones occur in more geologically diverse materials with less extensive discontinuities that limit their size. Submarine landslides detach mainly from gently inclined continental margin slopes (~1°–5°) capped by weak sedimentary and methane hydrate layers that form potential sliding planes66,69,70, whereas steeper submarine canyons give rise to smaller failures. While our database focuses on landslides with a recognisable topographic footprint, geological evidence of failures involving 2000–3000 km3 dated to >20 Ma, such as the Heart Mountain detachment71,72 or the Markagunt gravity slide73 in the western United States, show that Earth has terrestrial landslides of sizes similar to those on ocean floors or on Mars13. The apparent difference in the size range of the largest landslides between Earth and Mars may also reflect different preserving conditions on Mars that allow the topographic footprint to remain detectable for several billion years; thus, longer time series should also capture more landslides of larger magnitude13.

In summary, we find that grouping landslides by their topographic setting brings out the strongest contrast in their size distributions and median volumes, at least if compared to the effects of dominant rock type or contemporary climate as alternative categories, and regardless of volumetric uncertainties that are rarely reported. We conclude that knowledge about the specific placement of large-scale slope failure with respect to landforms such as volcanoes, mountain fronts, or valleys is more informative for estimating (and distinguishing) landslide size than a single quantitative measure such as mean local relief1. Although varying rock-mass strength is widely regarded as important for making hillslopes susceptible to large-scale failures, the dominant rock-type group involved hardly affects their size distribution and volume-area scaling, except for volcanic settings. This finding challenges the notion that parameters of power-law fits to landslide size data reveal information about material properties such as cohesive strength or internal fiction4. Similarly, contemporary climatic setting has a negligible effect on landslide size statistics despite any commensurable differences in the rates of vegetation cover, snow and ice cover, weathering, or erosion that may have altered geomorphic evidence and thus detectability. Hence, we can rule out any major detection or mapping bias arising from contemporary climatic conditions. We conclude that future bulk volumetric and area estimates of Earth’s largest terrestrial slope failures might benefit most from a closer consideration of topographic setting and material properties that go beyond nominal rock types and include instead lithological contrasts, defects, and discontinuities.

Methods

Mapping

We compiled a global inventory of the largest terrestrial landslides, focusing only on rapid to extremely rapid42 slope failures involving >1 km3 of material or affecting >10 km2 of terrain. Our choice of this arbitrary size threshold reflects a compromise between a large enough sample size and a justified use of an extreme-value model for estimating size scaling properties. We considered landslide volumes to within 25% of our size threshold to account for uncertain estimates, and assumed volumetric errors in all data (see below), although these errors are rarely reported. We focus on landslides with evidence of catastrophic motion and a detectable topographic imprint. Determining from geomorphic evidence whether a landslide involved a distinct catastrophic failure relies on a suite of diagnostic evidence30,37,42, including hummocky and sharp-lipped flow lobes of coarse rock fragments; run-up or swash against topographic obstacles or hillslopes; traces of extensive movement upstream; toreva blocks; molards; or lateral levees. In case of stacked or overlapping landslide deposits of likely differing ages, we only mapped the one that was the uppermost in the stratigraphy, the geomorphically most distinct, and had the highest surface roughness, given that the failure dimensions exceeded our size threshold. We only considered landslides for which we could associate the source area with a commensurately large deposit, and ignored surrounding or superimposed failures affecting smaller portions of the main headscarp or those that reworked parts of the deposit. We also excluded slow-moving hillslope-scale failures with landforms such as ridge-top depressions and counter-slope scarps diagnostic of deep-seated gravitational slope deformation62,74,75,76, or landslides with vague outlines or those indicating prolonged phases of slow failure. We collected information from some 140 publications, including landslide catalogues and case studies (Supplementary Data 1). Few previous global compilations of large landslides focused on volcanoes51,77 or the ocean floor66, while regional catalogues covered parts of the Andes29,33,78,79; the European Alps75,80; Anatolia57; Central Asia39,81; the Mexican Volcanic Belt47; and Kamchatka48. Some inventories included coastal areas, plateaus, or hilly areas30,31,32. We complemented these published data with landslides from our own mapping. We used a worldwide search grid to obtain a systematic and geographically unbiased sample, including also regions with few or no reported landslides. We used ESRI ArcGIS Pro to place 2000 randomly distributed search points on the land surface except for Antarctica and glaciated regions, and grouped these points by four bins of local topographic relief (0–200 m; 201–1000 m; 1001–2500 m; and 2500–5080 m; defined as the maximum elevation range in 5 km radius, see below), and weighted the number of points per bin by the number of published landslides in this bin. Thus, we allocated more search points to areas with more reported landslides. About 75% of the land surface is in the 0–200 m relief bin, such that we doubled the number of search points in this bin to reduce a bias towards low-relief areas. Each of us searched independently for evidence of landslides in a 50 km radius around each point, thus covering about 10% of the global land surface. We used satellite imagery from Maxar (mostly QuickBird-2, GeoEye-1, and WorldView2-4 satellites) with a maximum resolution of 0.6 m, and shaded relief based on 24-m WorldDEM4Ortho data, both provided by the ESRITM World Imagery service (https://services.arcgisonline.com/arcgis/rest/services). We mapped landslides from oblique views in Google Earth ProTM, recording location, total affected area, vertical drop H, runout L, and apparent mobility82 H/L of each landslide using a set of common criteria (Supplementary Data 1). We discerned rock avalanches, rockslides, rock slides-earthflows, volcanic debris avalanches, and debris flows on the assumption that all deposits indicated catastrophic emplacement (Supplementary Fig. 1). Few landslide deposits in our inventory have a vague or curiously stacked deposit morphology that may indicate multiple slope failures. We excluded any landslides without distinct lateral scarps, but part of larger complexes of multiple adjacent or superimposed failures that are hard to distinguish from each other. Examples of such complexes include valley-flank collapses that line hundreds of kilometres of the quebradas of coastal Peru and Chile83 or basaltic plateaus in eastern Patagonia84. About half of the 411 landslides in our database were published since a first global review of large terrestrial landslides17, while a fifth was identified since or previously unpublished (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1).

Landslide characteristics

We obtained several major topographic and geological, and climatic characteristics (Supplementary Data 1), taking parameters such as volume, area, headscarp elevation, drop height, runout, and mobility mostly from the original sources, and computed these metrics for all landslides. Where possible, we estimated volumes by reconstructing the pre-failure topography. We note that 25, or about one third, of the landslides that we detected during the random search have well-defined, bowl-shaped source areas. For these cases, we estimated the failure volumes by joining as straight lines the contours across the source area, based on 30 m SRTM global elevation data global digital elevation data (https://topex.ucsd.edu/WWW_html/srtm30_plus.html). We multiplied these volume estimates by a factor of 1.25 to allow for volumetric bulking17,20,37. For 49 other cases, we were unable to delineate scarp areas sufficiently well, but the landslide deposits largely overlapped the sliding planes, such that we estimated landslide thickness from a series of topographic profiles, and a half-ellipsoid approximation42. For rock avalanches fully evacuating material from the scarp we used a cut-and-fill method for calculations source areas and deposits, whereas for rockslides obscuring the sliding plane we also estimated the depth from the cross-section and used the half-ellipsoid approximation42. For deposits on floodplains, valley fills, or volcanic ring plains, we estimated the deposit volume rising above the valley floor. To this end, we joined contours that remained undisturbed by slope failure to reconstruct the pre-failure topography. This method likely returns a minimum volume estimate as post-failure sedimentation may have buried parts of the deposit. For river-blocking landslides, we estimated the deposit thickness by interpolating the river longitudinal profile between unaffected upstream and downstream locations: a dammed profile has a distinct knickpoint that scales in size with the average thickness of the dam. Where available, we recorded both source and deposit volume for each landslide. In all scenarios we assumed relative volumetric errors to be of the order of ±25% per unit standard deviation. We estimated mean local relief as the maximum elevation gain over a 5 km distance (to be consistent with previous work17) within 15 km of each landslide centroid from the SRTM30 data in World Equidistant Cylindrical projection. We also assigned to each landslide one of five topographic settings surrounding the site, i.e., volcanic edifices, fault-bounded mountain fronts, escarpments, river valleys, and glacial valleys. The dominant lithology concerns the main rock group rocks forming the source area of each landslide, and taken from the original literature (i.e., for 80% of our inventory data). For cases that we identified through our own mapping, we assigned the dominant lithology using the Global Lithological Map database (GLiM85), and cross-checked this information with national geological maps, such as the National Geological Map Database of the United States (https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/ngmdb/ngmdb_home.html). While published studies mostly resolve the main material involved in landslides at the level of individual rock types, we can establish consistent data for our mapped landslides only by lumping information about the dominant lithology (in terms of its area intersecting with the source area) into five groups, i.e., plutonic, metamorphic, sedimentary, volcanic, and volcanic-sedimentary. Given that the landslides considered here each cover >10 km2, our approach avoids local inaccuracies in regional-scale geological data. We further recorded the distance from active faults, defined as being capable of producing moderate to large earthquakes and having geologic evidence of recent deformation, historic earthquake activity, or measurable geodetic strain accumulation, from the Global Active Faults database86. Finally, we assigned one of five contemporary climate zones to each landslide according to the Köppen-Geiger classification87. We use these climate zones as a proxy of average vegetation, cloud, snow, and ice cover. We assume that, to first order, more vegetation hides more geomorphic evidence of landslides, while also altering the potential for reworking this evidence by erosion or deposition. Snow and ice might similarly conceal evidence, but are likely more effective in also in removing it.

Landslide size and scaling models

We used Bayesian inference to learn the volumetric distribution of landslides, drawing on extreme-value theory for peak-over-threshold observations. Using an arbitrary threshold fixed at u = 0.75 km3 (that allows for 25% uncertainty in reported volumetric estimates within our nominal lower size limit of 1 km3), we fit to i = 1,…, n reported landslide volumes a GPD, which in its heavy-tailed case has probability density88:

Here y > u is landslide volume above threshold u; and σ > 0 is the scale, and k > 0 is the shape parameter. In extreme-value theory, the GPD approximates the expected distribution of sample observations truncated at a sufficiently high u. The scale σ marks the sample sizes beyond which inverse power-law scaling sets in, while shape k is the inverse of the power-law scaling exponent used in numerous landslide statistical studies4. Both parameters express a statistical expectation of how extreme landslides sizes are distributed, regardless of any underlying physics. Given the largely unreported uncertainties regarding landslide volumes (as high as ±50% for individual cases), we included in our GPD model a measurement model that assumes that the real, but unobserved, landslide volumes yu are lognormal distributed with location mu and scale su > 0, and that both reported and our own estimated volumes yobs are prone to some fixed measurement noise τ > 0:

The lognormal model reflects our theoretical expectation of encountering multiplicative errors in landslide volumes, as they are often practically obtained by multiplying areas with mean thicknesses. We estimated mu and su directly from the data, and found that values of τ < 5 km3 in a properly re-normalised Gaussian distribution hardly changed our overall results. Such fixed measurement noise adds higher volumetric uncertainty to the more numerous smaller landslides that dominate our parameter estimates. To simulate also independently the effect of volumetric error estimates in our data, we replicated model runs numerous times, each time with randomly generated point-wise relative Gaussian errors of up to +/− 25%. Again, this randomisation hardly altered the main outcomes of our models. We use a multi-level model, which lets both k and σ vary with j = 1, …, J group labels in the data, while also providing a pooled estimate across all data, and thus obviating the problem of low sample size and potential overfitting (i.e., too confident parameter estimates) for each group. We choose physically plausible groups that characterise different (a) topographic settings surrounding the landslide sites, (b) dominant lithologies, and (c) contemporary climate zones, and set up a multi-level model for each of these three categorical variables. The GPD can be cast as an exponential-gamma mixture model88, hence we model the spread of kj (and σj) between these groups with a Gamma distribution of shape αk > 0 and rate βk > 0 (of shape αs > 0 and rate βs > 0); all these hyper-parameters are learned independently from the data, and specified by half-Gaussian priors89 to ensure positive parameter values:

These hyper-prior distributions capture the range of reported12 scaling exponents for landslide volumes, i.e., 1/3 <k < 1; yj[i] means the ith landslide belonging to group j. The median of the GPD is defined as

such that we can obtain the group-wise median landslide volumes directly from the posterior parameter estimates of kj and σj. To estimate the median volume also conditional on its total affected (footprint) area yi, or instead the local mean relief Hi, we ran a separate set of Bayesian multi-level models using a median regression. This specific form of (fixed) quantile regression is based on a symmetric Laplace (or double-exponential) distribution90 that is invariant to log-transformed data:

where κ is a scale parameter. We model the conditional median landslide volume as a linear combination of intercept a, and predictor x (either area yi, or local mean relief Hi) weighted by slope b. We use the same J group levels of topographic setting, dominant rock type, and climate zone, and let intercepts aj and slopes bj vary per group j. We also let the rate parameter of the double-exponential likelihood κj scale with x, thus acknowledging that the spread of reported volumetric estimates may vary commensurately for a given landslide size or mean local relief:

We used weakly informative, zero-centred Student-t distributed priors with three degrees of freedom on hyper-parameters aj, bj, cj, and dj. We standardise the input data such that the group-level regression intercepts aj are the estimated median volumes for mean inputs, i.e., the average (log-transformed) landslide area, or the average local relief, per group. Analytical solutions of both the Bayesian GPD and median regression models are intractable. Hence, we numerically approximated the posterior joint distributions using the R package brms89, which calls the probabilistic programming language STAN91 and offers median regression. We implemented the GPD models in STAN directly and ran the simulations in the free statistical programming environment R (https://cran.r-project.org/). All models ran a no-U-turn sampling scheme in four separate chains of 2000 samples each (including 500 warmup iterations) that we checked for convergence before running posterior predictive checks with the data.

One main advantage of both GPD and quantile models is that they offer predictive posterior distributions of volume for each individual landslide, while drawing on its topographic, lithological or climatic group context as well as the entire sample size. We estimated the difference between expected log predictive densities92 of each group-level model to identify the most suitable, and also compared these models with simpler (“pooled”) variants fitted to all data without any group levels. We used 95% highest density intervals (HDIs) of the posterior estimates of the group-level predictors to check for credibly non-zero deviations from a pooled model conditioned on all data. A 95% HDI expresses the numerical range of a model estimate (i.e., any parameter, or any given landslide volume) with a 95% posterior credibility. Given the data and the prior knowledge specified, we believe that the desired model estimate is within that range with 0.95 probability.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All landslide data (Supplementary Data 1) needed to reproduce the results of this study are contained in a comma-separated (CSV) file that is publicly available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15908067). The 30-m SRTM global digital elevation data form the basis of all our topographic measurements, and are also freely available (https://topex.ucsd.edu/WWW_html/srtm30_plus.html). The GLIM data on major lithological groups are publicly available in gridded format in the PANGEA database (https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.788537), while data on active fault zones are listed in an open repository (https://github.com/GEMScienceTools/gem-global-active-faults). An updated version of the current climatological data according to the Köppen-Geiger classification is also available in gridded format (https://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at/). All other landslide-case specific information is contained in the references listed in our landslide catalogue.

Code availability

We provide an R HTML Notebook in the Supplementary Material to document the entire workflow and code needed to reproduce the results of this study. This document was generated using the freely available software environment R (https://cran.r-project.org/) version 4.4.3 (2025-02-28), and the free desktop version of the RStudio/Posit IDE (https://posit.co/downloads/) version 2025.05.1 + 513.

References

Schmidt, K. & Montgomery, D. Limits to relief. Science 270, 617–620 (1995).

Clarke, B. A. & Burbank, D. W. Bedrock fracturing, threshold hillslopes, and limits to the magnitude of bedrock landslides. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 297, 577–586 (2010).

Li, G. K. & Moon, S. Topographic stress control on bedrock landslide size. Nat. Geosci. 14, 307–313 (2021).

Tebbens, S. W. Landslide scaling: a review. Earth Space Sci. 7, e2019EA000662 (2019).

Parker, R. et al. Mass wasting triggered by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake is greater than orogenic growth. Nat. Geosci. 4, 449–452 (2011).

Gorum, T. et al. Complex rupture mechanism and topography control symmetry of mass-wasting pattern, 2010 Haiti earthquake. Geomorphology 184, 127–138 (2013).

Saito, H., Korup, O., Uchida, T., Hazashi, S. & Oguchi, T. Rainfall conditions, typhoon frequency, and contemporary landslide erosion in Japan. Geology 42, 999–1002 (2014).

Xu, C., Shyu, J. B. H. & Xu, X. W. Landslides triggered by the 12 January 2010 Mw 7.0 Port-au-Prince, Haiti, earthquake: visual interpretation, inventory compiling and spatial distribution statistical analysis. Nat. Haz. Earth Sys. Sci. 14, 1789–1818 (2014).

Roback, K. et al. The size, distribution, and mobility of landslides caused by the 2015 Mw7.8 Gorkha earthquake, Nepal. Geomorphology 301, 121–138 (2018).

Tanyas, H., van Westen, C. J., Allstadt, K. E. & Jibson, R. W. Factors controlling landslide frequency-area distributions. Earth Surf. Proc. Landf. 44, 900–917 (2019).

Larsen, I. J., Montgomery, D. R. & Korup, O. Landslide erosion controlled by hillslope material. Nat. Geosci. 3, 247–251 (2010).

Korup, O. Landslides in the Earth system. Landslides: Types, Mechanisms and Modeling, eds. Clague, J. J. & Stead, D. 10–23 (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Crosta, G. B., Frattini, P., Valbuzzi, E. & De Blasio, F. V. Introducing a new inventory of large Martian landslides. Earth Space Sci. 5, 89–119 (2018).

Pinto, L., Hérail, G., Sepúlveda, S. A. & Krop, P. A Neogene giant landslide in Tarapaca, northern Chile: a signal of instability of the westernmost Altiplano and palaeoseismicity effects. Geomorphology 102, 532–541 (2008).

Weidinger, J. T. et al. Giant rockslide from the inside. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 389, 62–73 (2014).

Davies, T. R. H. Mountain process geomorphology: conceptual progress in the Southern Alps. Shulmeister J. (Ed.), Landscape and Quaternary Environmental Change in New Zealand, Atlantis Advances in Quaternary Science, vol. 3, 205–233 (Atlantis Press, 2017).

Korup, O. et al. Giant landslides, topography, and erosion. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 261, 578–589 (2007).

Korup, O. Earth’s portfolio of extreme sediment transport events. Earth-Sci. Rev. 112, 115–125 (2012).

Dahlquist, M. P., West, J. & Li, G. Landslide-driven drainage divide migration. Geology 46, 403–406 (2018).

Hewitt, K. Disturbance regime landscapes: mountain drainage systems interrupted by large rockslides. Progr. Phys. Geogr. 30, 365–393 (2006).

Korup, O., Strom, A. L. & Weidinger, J. T. Fluvial response to large rock-slope failures: Examples from the Himalayas, the Tien Shan, and the Southern Alps in New Zealand. Geomorphology 78, 3–21 (2006).

Fan, X. et al. Transient water and sediment storage of the decaying landslide dams induced by the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, China. Geomorphology 171–72, 58–68 (2012).

Hunt, J. E., Cassidy, M. & Talling, P. J. Multi-stage volcanic island flank collapses with coeval explosive caldera-forming eruptions. Sci. Rep. 8, 1146 (2018).

Higman, B. et al. The 2015 landslide and tsunami in Taan Fiord, Alaska. Sci. Rep. 8, 12993 (2018).

Geertsema, M. & Pojar, J. J. Influence of landslides on biophysical diversity — a perspective from British Columbia. Geomorphology 89, 55–69 (2007).

Mackay, B. H., Roering, J. J. & Lamb, M. P. Landslide-dammed paleolake perturbs marine sedimentation and drives genetic change in anadromous fish. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 108, 18905–18909 (2011).

García-Olivares, V. et al. Evidence for mega-landslides as drivers of island colonization. J. Biogeogr. 44, 1053–1064 (2017).

Strom, A. L. Rock avalanches of the Ardon River valley at the southern foot of the Rocky Range, Northern Caucasus, North Osetia. Landslides 1, 237–241 (2004).

Crosta, G. B., Hermanns, R. L., Frattini, P. & Valbuzzi, E. Large slope instabilities in Northern Chile: inventory, characterization and possible triggerings. In Proc. 3rd World Landslide Forum, 2–6 June 2014, Bejing. Volume 3: Targeted Landslides, 175–181 (WLF, 2014).

Safran, E. B., Anderson, S. W., Mills-Novoa, M., House, P. K. & Ely, L. Controls on large landslide distribution and implications for the geomorphic evolution of the southern interior Columbia River basin. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 123, 1851–1862 (2011).

Pánek, T., Korup, O., Minár, J. & Hradecký, J. Giant landslides and highstands of the Caspian Sea. Geology 44, 939–1942 (2016).

Pánek, T., Korup, O., Lenart, J., Hradecký, J. & Břežný, M. Giant landslides in the foreland of the Patagonian Ice Sheet. Quatern. Sci. Rev. 194, 39–54 (2018).

Antinao, J. L. & Gosse, J. Large rockslides in the southern central Andes of Chile (32-34.5°S): tectonic control and significance for quaternary landscape evolution. Geomorphology 104, 117–133 (2009).

Roberts, J. N. & Evans, S. G. The gigantic Seymareh (Saidmarreh) rock avalanche, Zagros Fold–Thrust Belt, Iran. J. Geol. Soc. 170, 685–700 (2013).

Cui, Y. et al. 36Cl exposure dating of the Mahu Giant landslide (Sichuan Province, China). Eng. Geol. 285, 106039 (2021).

Nilforoushan, A., Khamehchiyan, M. & Nikudel, M. R. Investigation of the probable trigger factor for large landslides in north of Dehdasht, Iran. Nat. Haz. 105, 1891–1921 (2021).

Hewitt, K. Catastrophic rock slope failures and late Quaternary developments in the Nanga Parbat–Haramosh Massif, Upper Indus basin, northern Pakistan. Quatern. Sci. Rev. 28, 1055–1069 (2009).

Beetham, R. D., McSaveney, M. J. & Read, S. A. L. Four extremely large landslides in New Zealand. Rybar, J., Stemberk, J. & Wagner, P. (Eds.). In Proc. 1st European Conference on Landslides. 97–102 (2002).

Strom, A. & Abdrakhmatov, K. Rockslides and Rock Avalanches of Central Asia. Rockslides and Rock Avalanches of Central Asia. (Elsevier Inc., 2018).

Delcamp, A., Kervyn, M., Banbakkar, M., Kwelwa, S. & Peter, D. Large volcanic landslide and debris avalanche deposit at Meru, Tanzania. Landslides 14, 833–847 (2017).

Dewitte, O. et al. Constraining landslide timing in a data-scarce context: from recent to very old processes in the tropical environment of the North Tanganyika-Kivu Rift region. Landslides 18, 161–177 (2021).

Cruden, D. M. & Varnes, D. J. Landslide types and processes. In: Turner A. K., Schuster R. L. (Eds.), Landslides investigation and mitigation. Transportation Research Board, US National Research Council. Special Report 247, Washington, DC, pp. 36–75 (1996).

Carrasco-Núñez, G. et al. Multiple edifice-collapse events in the Eastern Mexican Volcanic Belt: The role of sloping substrate and implications for hazard assessment. J. Volcan. Geotherm. Res. 158, 151–176 (2006).

Philip, H. & Ritz, J. F. Gigantic paleolandslide associated with active faulting along the Bogd fault (Gobi–Altay, Mongolia). Geology 27, 211–214 (1999).

Harrison, J. V. & Falcon, N. L. The Saidmarreh landslip, Southwest Iran. Geogr. J. 89, 42–47 (1937).

Blöthe, J. H., Korup, O. & Schwanghart, W. 2015. Large landslides lie low: excess topography in the Himalaya-Karakoram ranges. Geology 43, 523–526 (2015).

Capra, L., Macias, J. L., Scott, K. M., Abrams, M. & Garduno-Monroy, V. H. Debris avalanches and debris flows transformed from collapses in the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, Mexico — behavior, and implications for hazard assessment. J. Volcan. Geotherm. Res. 113, 81–110 (2002).

Ponomareva, V. V., Melekestsev, I. V. & Dirksen, O. V. Sector collapses and large landslides on Late Pleistocene–Holocene volcanoes, Kamchatka, Russia. J. Volcan. Geotherm. Res. 158, 117–138 (2006).

Ivy-Ochs, S., von Poschinger, A., Synal, H. A. & Maisch, M. Surface exposure dating of the Flims landslide, Graubünden, Switzerland. Geomorphology 103, 104–112 (2009).

Pierson, T. C., Evarts, R. C. & Bard, J. A. Landslides in the western Columbia Gorge, Skamania County, Washington. U. S. Geol. Surv. Numb. Ser. 3358, 22 (2016).

Roverato, M., Dufresne, A. & Procter, J. Volcanic Debris Avalanches: from collapse to hazard. (Springer, 2021).

Zerathe, S. et al. Toward the feldspar alternative for cosmogenic 10Be exposure dating. Quatern. Geochron. 41, 83–96 (2017).

Pánek, T. et al. Moraines and marls: Giant landslides of the Lago Pueyrredón valley in Patagonia, Argentina. Quatern. Sci. Rev. 248, 106598 (2020).

Dufresne, A., Siebert, l. & Bernard, B. Distribution and Geometric Parameters of Volcanic Debris Avalanche Deposits. In Roverato, M., Dufresne, A. & Proter, J. (Eds.), Volcanic debris avalanches (Springer, 2021).

Hewitt, K. Large, Topography-Constrained Rockslide Complexes in the Karakoram Himalaya, Northern Pakistan. In: Margottini, C., Canuti, P., Sassa, K. (eds) Landslide Science and Practice. 335–346 (Springer, 2013).

Hancox, G. T. & Perrin, N. D. Green Lake Landslide and other giant and very large postglacial landslides in Fiordland, New Zealand. Quatern. Sci. Rev. 28, 1020–1036 (2009).

Gorum, T. Tectonic, topographic and rock-type influences on large landslides at the northern margin of the Anatolian Plateau. Landslides 16, 333–346 (2019).

Hovius, N. H., Stark, C. P., Tutton, M. A. & Abbott, L. D. Landslide-driven drainage network evolution in a pre-steady-state mountain belt: Finisterre Mountains, Papua New Guinea. Geology 26, 1071–1074 (1998).

Meng, Q. R., Hu, J. M., Wang, E. & Qu, H. J. Late Cenozoic denudation by large-magnitude landslides in eastern edge of Tibetan Plateau. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 411, 252–267 (2006).

Jarman, D. & Harrison, S. Rock slope failure in the British mountains. Geomorphology 340, 202–233 (2019).

Kuhn, D. et al. Anatomy of a mega-rock slide at Forkastningsfjellet, Spitsbergen and its implications for landslide hazard and risk considerations. Norweg. J. Geol. 99, 41–61 (2019).

Agliardi, F., Crosta, G. B., Frattini, P. & Malusà, M. Giant non–catastrophic landslides and the long–term exhumation of the European Alps. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 365, 263–274 (2013).

Korup, O. & Schlunegger, F. Rock-type control on erosion-induced uplift, eastern Swiss Alps. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 278, 278–285 (2009).

Agliardi, F., Scuderi, M. M., Fusi, N. & Collettini, C. Slow-to-fast transition of giant creeping rockslides modulated by undrained loading in basal shear zones. Nat. Comm. 11, 1352 (2020).

Aslan, G., De Michelle, M., Raucoules, D., Bernardie, S. & Cakir, Z. Transient motion of the largest landslide on earth, modulated by hydrological forces. Sci. Rep. 11, 10407 (2021).

Hampton, M. A., Lee, H. J. & Locat, J. Submarine landslides. Rev. Geophys. 34, 33–59 (1996).

Gee, M. J. R., Uy, H. S., Warren, J., Morley, C. K. & Lambiase, J. J. The Brunei slide: a giant submarine landslide on the North Wets Borneo margin revealed by 3D seismic data. Mar. Geol. 246, 9–23 (2007).

Moore, J. G., Normark, W. R. & Holcomb, R. T. Giant Hawaiian landslides. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 22, 119–144 (1994).

Masson, D. G., Harbitz, C. B., Wynn, R. B., Pedersen, G. & Løvholt, F. Submarine landslides: processes, triggers and hazard prediction. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 364, 2009–2039 (2006).

Gatter, R., Clare, M. A., Kuhlmann, J. & Huhn, K. Characterisation of weak layers, physical controls on their global distribution and their role in submarine landslide formation. Earth-Sci. Rev. 223, 103845 (2021).

Aharonov, E. & Anders, M. H. Hot water: a solution to the Heart Mountain detachment problem? Geology 34, 165–168 (2006).

Mitchell, T. M. et al. Catastrophic emplacement of giant landslides aided by thermal decomposition: Heart Mountain, Wyoming. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 411, 199–207 (2015).

Hacker, D. B., Biek, R. F. & Rowley, P. D. Catastrophic emplacement of the gigantic Markagunt gravity slide, southwest Utah (USA): Implications for hazards associated with sector collapse of volcanic fields. Geology 42, 943–946 (2014).

Perkins, J. P., Reid, M. E. & Schmidt, K. M. Control of landslide volume and hazard by glacial stratigraphic architecture, northwest Washington State, USA. Geology 45, 1139–1142 (2017).

Crosta, G., Frattini, P. & Agliardi, F. Deep seated gravitational slope deformations in the European Alps. Tectonophys 605, 13–33 (2013).

Agliardi, F., Crosta, G. & Zanchi, A. 2001. Structural constraints on deep-seated slope deformation kinematics. Eng. Geol. 59, 83–102 (2001).

Blahůt, J. et al. A comprehensive global database of giant landslides on volcanic islands. Landslides 16, 2045–2052 (2019).

Penna, I. M., Hermanns, R. L., Niedermann, S. & Folguera, L. Multiple slope failures associated with neotectonic activity in the Southern Central Andes (37°–37°30′S), Patagonia, Argentina. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 123, 1880–1895 (2011).

Moreiras, S. M. & Sepúlveda, S. A. Megalandslides in the Andes of Central Chile and Argentina (32°−34°s) and potential hazards. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Pub. 399, 329–344 (2015).

Prager, C., Zangerl, C., Patzelt, G. & Brandner, R. Age distribution of fossil landslides in the Tyrol (Austria) and its surrounding areas. Nat. Haz. Earth Sys. Sci. 8, 377–407 (2008).

Shroder, J. F., Weihs, B. J. & Schettler, M. J. Mass movement in northeast Afghanistan. Phys. Chem. Earth 36, 1267–1286 (2011).

Legros, F. The mobility of long-runout landslides. Eng. Geol. 63, 301–331 (2002).

Delgado, F., Zerathe, S., Schwartz, S., Mathieux, B. & Benavente, C. Inventory of large landslides along the Central Western Andes (ca. 15°–20° S): Landslide distribution patterns and insights on controlling factors. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 116, 103824 (2022).

Schönfeldt, E., Winocur, D., Pánek, T. & Korup, O. Deep learning reveals one of Earth’s largest landslide terrains in Patagonia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 593, 117642 (2022).

Hartmann, J. & Moosdorf, N. The new global lithological map database GLiM: A representation of rock properties at the Earth surface. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 13, Q12004 (20212).

Styron, R. & Pagani, M. The GEM global active faults database. Earthqu. Spectra 36, 160–180 (2020).

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C. H., Rudolf, B. & Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteor. Zeit 15, 259–263 (2006).

Katz, R. W., Parlange, M. B. & Naveau, P. Statistics of extremes in hydrology. Adv. Water Resour. 25, 1287–1304 (2002).

Bürkner, P. C. BRMS: an R Package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 80, 1–28 (2017).

Yang, Y., Wang, H. J. & He, X. Posterior inference in Bayesian quantile regression with asymmetric laplace likelihood. Int. Stat. Rev. 84, 327–344 (2016).

Carpenter, B. et al. Stan: a probabilistic programming language. J. Stat. Softw. 76, 1–32 (2017).

Vehtari, A., Gelman, A. & Gabry, J. Practical Bayesian model evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Stat. Comp. 27, 1413–1432 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Johannes Amos Comenius Programme (P JAC), project No. CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004605. We thank Tolga Görum for providing data on the location of the largest landslides in Anatolia. All landslide data and computer codes for the model analyses will be made available on a public repository.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.K. and T.P. conceived and designed the study. O.K., T.P., and M.B. collected, compiled, and analysed the data. O.K., T.P., and M.B. contributed materials/analysis tools. O.K., T.P., and M.B. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Dual publication

We confirm that the results/data/figures in this manuscript have not been published elsewhere, nor are they under consideration by another publisher.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Kochappi Sajinkumar and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Korup, O., Pánek, T. & Břežný, M. Size estimates of Earth’s largest terrestrial landslides informed by topographic setting. Commun Earth Environ 6, 629 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02614-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02614-5