Abstract

Groundwater health is increasingly threatened by climate change, which alters precipitation patterns, leading to groundwater recharge shifts. These shifts impact subsurface microbial communities, crucial for maintaining ecosystem functions. In this decade-long study of carbonate aquifers, we analyzed 815 bacterial 16S rRNA gene datasets, 226 dissolved organic matter (DOM) profiles, 387 metabolomic datasets, and 174 seepage microbiomes. Our findings reveal distinct short- and long-term temporal patterns of groundwater microbiomes driven by environmental fluctuations. Microbiomes of hydrologically connected aquifers exhibit lower temporal stability due to stochastic processes and greater susceptibility to surface disturbances, yet demonstrate remarkable resilience. Conversely, more isolated aquifer microbiomes resist short-term changes, governed by deterministic processes, but exhibit reduced stability under prolonged stress. Variability in seepage-associated microorganisms, DOM, and metabolic diversity further drives microbiome dynamics. These findings highlight the dual vulnerability of groundwater systems to acute or chronic pressures and the need for sustainable management to mitigate hydroclimatic extremes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Groundwater, the largest global reservoir of accessible freshwater, is increasingly jeopardized by the dual pressures of anthropogenic activities and climate change, with widespread implications for water availability, quality, and ecosystem health1,2,3. Future climate scenarios predict profound shifts in groundwater recharge, driven predominantly by changing precipitation patterns and the intensification of hydroclimatic extremes2,3. These shifts threaten groundwater sustainability, particularly in vulnerable carbonate aquifers where water storage and flow dynamics are intricately linked to lithology and hydrological connectivity4,5. Understanding the resilience of groundwater ecosystems and their ability to maintain ecological functions under such pressures is critical for sustainable management strategies3,6.

Microbial communities are central to groundwater ecosystem health, playing pivotal roles in biogeochemical cycling, contaminant degradation, and ecosystem resilience7,8,9. Traditionally considered static due to the relatively constant conditions of subsurface environments, this view has persisted largely due to the lack of long-term observational studies. More recent studies challenge this notion by demonstrating that groundwater microbiomes exhibit a dynamic nature, driven by both short-term recharge events10,11,12 and longer-term environmental changes13. For instance, microbial immigration during recharge can trigger compositional shifts12,13, while prolonged droughts may alter microbial activity through changes in water chemistry14. Additionally, rain infiltration can mobilize soil microorganisms, transporting them to the groundwater via seepage15,16,17,18. These findings underscore the importance of hydrological connectivity as a key factor influencing microbial dispersal, assembly, and ecosystem resilience15,19,20,21.

Hydrological connectivity, shaped by aquifer configuration and permeability, flow dynamics, and recharge patterns, governs the flux of surface-derived inputs into groundwater and mediates microbial dispersal5,15,19,22,23. Hydrologically connected aquifers are particularly susceptible to surface-derived disturbances such as nutrient influxes, organic contaminants, and pathogens4,22,24. In contrast, more hydrologically isolated systems may exhibit greater stability11 but face stress under conditions of prolonged environmental change, such as reduced recharge during droughts14. These contrasting dynamics necessitate a framework for quantifying temporal stability (consistency), resistance (insensitivity to disturbance), and resilience (ability to recover) of groundwater microbiomes across gradients of hydrological connectivity9,21.

While previous studies have focused on microbiome compositional stability across ecosystems, functional stability is also a key indicator of ecosystem health13,25,26,27. To this end, we applied metabolomics techniques to probe system activity in our long-term study28. Untargeted liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS) can profile environmental meta-metabolomes, comprising metabolites released by microorganisms and anthropogenic activity. This approach is complemented by direct infusion–high-resolution mass spectrometry (DI-HRMS) resolving the full complexity of DOM without chromatographic bias29,30,31,32. This integrated information from both approaches, together with microbiome function analysis using PICRUSt2, resolves the impact of the organic chemical landscape on microbiome diversity33,34. This allowed us to explore groundwater microbiome stability, variability, and overall ecosystem health.

Our work builds on the growing recognition that climate change impacts not only groundwater recharge2 but also groundwater quality14, with downstream consequences for ecosystem functioning and biogeochemical cycles6,14. While previous studies have emphasized the role of surface inputs in shaping shallow groundwater microbiomes15,18,22, less is known about how microbial communities persist and evolve under more hydrologically isolated conditions. We extend this discussion by investigating how hydrological connectivity influences the stability and composition of groundwater microbiomes in carbonaceous sedimentary aquifers. Our study is situated in the Hainich Critical Zone Exploratory (CZE), a well-characterized field site in central Germany that provides a unique natural laboratory for studying groundwater systems along a hillslope23,35. Here, aquifers developed in alternating limestone and mudstone strata show pronounced differences in surface connectivity, recharge dynamics, and geochemical signatures—differences that cannot be explained by depth or permeability alone5. Some aquifers are tightly connected to the surface via outcropping intake zones, rapid recharge pathways, and oxygenated flow conditions, while others remain hydrologically isolated, hosting older, low-oxygen groundwater with limited surface-derived input5,36,37.

By leveraging a multi-well transect spanning crest to footslope positions, we assess microbiome variability along this natural connectivity gradient. This design enables us to explore how microbial communities are shaped by surface-derived dispersal, and geochemically dynamic versus stable environments caused by longer-term isolation, offering holistic insights into the factors governing microbiome stability and resilience in the subsurface.

Capitalizing on a decade-long groundwater survey comprising 815 bacterial 16S rRNA gene-sequence datasets (resolved at the level of amplicon sequence variants; ASVs) and accompanying hydrochemical analyses, 226 DOM analyses, and 387 metabolomic analyses combined with 174 seepage microbiome sequencing datasets, this study provides the most comprehensive assessment of groundwater microbiome variability and stability, and their potential drivers to date. To better assess the responses of precious groundwater resources to disturbances caused by increasing hydroclimatic extremes, this investigation addresses four key unknowns: (i) the extent to which microbiomes of hydrologically connected vs. more isolated groundwater exhibit similar temporal dynamics and stability, (ii) the means by which assembly mechanisms explain microbiome variability, (iii) the extent to which seepage-associated microorganisms contribute to microbiome variability, and (iv) the means by which alterations in groundwater metabolome/DOM explain microbiome variability. By integrating microbial, hydrochemical, and metabolomic datasets, this study reveals critical insights into the responses of groundwater ecosystems to environmental disturbances and hydroclimatic extremes. These findings have broad implications for predicting groundwater resilience and informing sustainable management strategies under future climate scenarios.

Results

Hydrological seasonality and long-term variability of groundwater microbiomes

Our 10-year time series revealed distinct and persistent regular patterns of variation in microbiome community similarity (Bray-Curtis) with alternating greater and lesser similarity over a 12-month period. These patterns demonstrated consistent periodicity, with distinct peaks in similarities approximately every 12 months and minima roughly 6 months after each peak. While these variations are on a 12-month cycle, we use the descriptive term ‘sinusoidal’ because groundwater systems can integrate a number of potentially seasonally varying signals and lag times. These sinusoidal patterns are observed in the similarity of shallow groundwater (<100 m depth) microbial communities over time across all wells, despite differences in groundwater hydrochemical parameters and microbiome composition among wells (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). The wells span a range of hydrological settings, including two with more hydrologically isolated conditions (H52 and H53) and others that are more connected to surface recharge (H14, H32, H41, H43, and H51). Notably, this behavior was not confined to a single bacterial phylum, as approximately half of the bacterial phyla detected displayed sinusoidal patterns (Supplementary Data 1).

a Temporal patterns in microbial community similarity across all groundwater samples per well. Blue points represent raw Bray-Curtis similarity values plotted against pairwise sampling time intervals. Regression lines (black dashed lines) and smoothing curves (red solid lines) are added to visualize both linear turnover and potential sinusoidal trends. Turnover rates (% year−1) are derived from regression slopes. Please note that y-axis is different across wells. b Temporal changes in groundwater microbial community diversity across individual wells. Each panel shows one well, with colors indicating bacterial classes whose relative abundances exceed 2%. The colors in the legend are arranged left to right, corresponding to the top-to-bottom order of taxa present in each stacked plot; however, not all taxa (and their associated colors) appear in every panel due to differences in community composition. The first six years of microbiome data at wells of H41, H43, and H52 were published in Yan et al.13 Sample size per well are as follows: H14, n = 89; H32, n = 125; H41, n = 117; H43, n = 118; H51, n = 119; H52, n = 124; H53, n = 123.

Similar sinusoidal patterns were also observed for hydrochemical properties of the groundwater (Supplementary Fig. 1c). The amplitudes of sinusoidal patterns in similarities of microbiome communities and hydrochemical parameters varied among wells. Distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) indicated that hydrological seasons (i.e., early summer, later summer, early winter, and later winter) statistically accounted for one to six percent of the microbiome variation (P < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 2), except in one of the more hydrologically isolated wells (e.g., H53).

The phylogenetic structure of groundwater microbiomes, reflecting evolutionary relationships among community members as measured by Unifrac similarity, exhibited weaker or no sinusoidal patterns compared to microbiome composition, which captures changes in presence and abundance of microbial taxa (Supplementary Fig. 3). Only one to three percent of the variation in phylogenetic structure at four wells (H32, H41, H43, and H52) was associated with hydrological seasons (dbRDA, P < 0.05). These findings suggest that various responses to changing hydrological seasons elicited by phylogenetically closely related microorganisms may offset seasonal effects.

Beyond sinusoidal patterns, all groundwater microbiomes showed long-term variability, as indicated by Mantel tests (P < 0.05; Fig. 1a). Microbial community similarity declined over time across all wells, with temporal turnover rates (i.e., the rate of community similarity change) ranging from 1.8% to 5.6% per year (Fig. 1a). While the phylogenetic structures of the microbiome compositions also exhibited long-term variability (Mantel tests, P < 0.05), their temporal turnover rates were lower (0.8–2.6% per year, Supplementary Fig. 3). These results suggest that roughly half of the turnover in groundwater microbiomes may be directed towards phylogenetically closely related microorganisms.

Contrasting temporal patterns of groundwater microbiomes

Groundwater microbiomes exhibited differing degrees of short-term variations, with mean Bray-Curtis dissimilarities between samples at one-month intervals ranging from 68% at well H14 to 25% at well H52, reflecting the strength of community composition fluctuations over time (Figs. 1b and 2a). In contrast, groundwater hydrochemical parameters, indicators of environmental changes, showed more consistent short-term variations, with mean Euclidean dissimilarities ranging from 14% to 26% (Supplementary Fig. 4). This disparity in short-term variations between hydrochemical parameters and microbiome compositions suggests varying levels of microbiome resistance to environmental changes, with greater short-term microbiome variation corresponding to lower resistance.

Pronounced short-term (1 month) variability was observed in microbiomes at wells in hydrologically connected aquifers (H14, H43, H41, and H51), while pronounced long-term (10 years) variability was detected in wells representing more hydrologically isolated groundwater (H52 and H53; Fig. 2b). Microbiomes with pronounced short-term variability yielded greater mean Shannon index values (5.2-5.9) and smaller fractions of core microorganisms (ASVs present ≥ 80% of collected well samples; 9-29%), compared to those with pronounced long-term variability, which exhibited lower Shannon indices (4.5-4.7) and larger core bacterial fractions (55–65%; Wilcoxon test, P < 0.01; Fig. 2c, d). Microbiomes at well H32 exhibited equally elevated short-term and long-term variability, with intermediate characteristics between hydrologically connected and more isolated groundwaters, which may reflect fluctuating hydrological connectivity at this site (Fig. 2).

a Short-term variation in groundwater microbiome diversity across wells, shown as on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities (%) between samples collected one month apart (15–44 days). Short red horizontal lines denote the mean dissimilarity per well. b Comparison of microbial community variation at short-term (1 month, blue) and long-term (10 years, green) time scales, expressed as proportions of total dissimilarity. Y axis values indicate the relative contribution of each time scale to the total observed variation. c Shannon diversity indices of groundwater microbial communities per well, with short red horizontal lines denoting the mean value. d Fraction of core microorganisms per well (ASVs present in ≥ 80% of samples). Colors represent dominant bacterial classes. e Relative contribution of groundwater microbial assembly processes per well. Blue hues represent deterministic processes (heterogeneous selection and homogeneous selection), while pink hues represent stochastic processes (dispersal limitation, horizontal dispersal, and drift and others). Since these analyses were conducted on a single site over time, the dispersal here was related to time rather than space. f Significant linear model between the relative abundance of (temporal) dispersal limitation (x-axis) and temporal stability of groundwater microbiome diversity (y-axis, using mean Bray-Curtis similarity). Sample sizes for comparison between hydrologically connected wells and more isolated wells in c): n = 443 vs 247.

Microbiomes in hydrologically connected groundwater exhibited lower resistance (i.e., the ability of a community to withstand short-term environmental changes) but higher resilience, as indicated by their lower temporal turnover rates (1.8–3.9% year−1) compared to more hydrologically isolated groundwater (5.2–5.6% year−1; Fig. 1a). Here, resilience refers to the ability of groundwater microbiomes to maintain community composition over time despite ongoing environmental change (as suggested by temporal variations in groundwater hydrochemical parameters across all wells; supplementary Fig. 1c). A low resilience is indicated by a high microbial community turnover rate. Temporal stability, measured by mean pairwise Bray-Curtis similarities, was significantly lower in microbiomes of more hydrologically connected groundwater (16–31%) than their more isolated counterparts (44-48%; Fig. 3a).

Temporal stability of a groundwater microbiome compositions, b predicted functional profiles of groundwater microbiomes inferred from 16S rRNA gene-sequences, c metabolome compositions, and d bulk DOM compositions across wells per Bray-Curtis similarity. Temporal stability is represented by mean Bray-Curtis similarity (%) between samples within each well (higher values indicate greater stability). Red horizontal lines denote the mean similarity per well. Sample sizes for comparison between hydrologically connected wells and more isolated wells are as follows: a n = 443 vs 247, b n = 443 vs 247, c n = 207 vs 122, d n = 121 vs 71.

Impact of seepage-associated microorganisms on groundwater microbiome variations

To appraise the extent of variability in groundwater microbiomes driven by soil-borne microorganisms transported with the seepage into the groundwater, we compared 16S rRNA gene datasets16 from soil seepage (23–60 cm depth) in local recharge areas with those from groundwater microbiomes. Seepage microbial diversity, dominated by Gammaproteobacteria (32%), Alphaproteobacteria (24%), and Parcubacteria (10%), differed significantly from that of groundwaters (Permutation tests, P = 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 5), which allows the use of microbial source tracking techniques.

SourceTracker analyses revealed that hydrologically connected groundwater harbored significantly higher fractions of seepage-associated microorganisms (2.4–8.9% of the total community) than did more hydrologically isolated groundwaters (0.2–1.7%; Wilcoxon tests, P < 0.001; Fig. 4a). Despite these variations across wells, however, seepage-associated microorganisms consistently statistically accounted for a mere four percent of groundwater microbiome variation (dbRDA; supplementary Fig. 2). These results suggest that low survival rates of seepage-associated microorganisms limit their contribution in shaping groundwater microbiome composition.

a Fraction of seepage-associated microorganisms across wells. Red horizontal lines denote mean values per well. b Temporal patterns of seepage-associated microbial diversity across the well. Stacked colors represent bacterial classes whose maximum fraction exceeds 1%; black lines delineate daily groundwater level fluctuations. Spearman correlation assessed the relationships between seepage-associated microbe fractions and groundwater level fluctuations. Sample sizes for comparison between hydrologically connected wells and more isolated wells in a: n = 443 vs 247. Sample sizes per well for Spearman correlations in b are as follows: H14, n = 82; H32, n = 123; H41, n = 111; H43, n = 73; H51, n = 114; H52, n = 117; H53, n = 96.

A significant correlation was observed between the proportion of seepage-associated microorganisms and groundwater level fluctuations at wells H14 and H41 (Fig. 4b), while a statistically significant, albeit weak, correlation between daily precipitation and groundwater levels was observed only at the shallowest well H14 (PPearson = 0.03; rPearson = 0.04; Supplementary Fig. 6). The fractions of seepage-associated microorganisms at wells H41 and H43 were significantly greater during groundwater recharge (rising water levels; 3.9% and 3.1%, respectively) than groundwater recession (falling water levels; 1.4% and 2%, respectively; Wilcoxon test, P < 0.01). Seepage-associated microbial diversity in groundwater was dominated by Alphaproteobacteria (mainly Caulobacter, Sphingobium), Gammaproteobacteria (mainly Polaromonas, Rhodoferax), and Parcubacteria (mainly Candidatus Adlerbacteria, Candidatus Nomurabacteria).

Contrasting assembly processes in groundwater microbiomes

Microbiome composition was driven primarily by stochastic processes (stochasticity: 67-82%) in hydrologically connected groundwaters and deterministic processes in more hydrologically isolated groundwaters (stochasticity: 38-42%; Fig. 2e). Temporal dispersal limitation (dispersal limitation over time at one site) ranged from 18% to 32% in hydrologically connected groundwaters and 14% to 15% in more hydrologically isolated groundwaters (Fig. 2e), indicative of more dynamic population structures in the former. This was supported by higher Shannon indices, smaller fractions of core community members, and increased seepage-associated microbial inputs in hydrologically connected groundwaters (Figs. 2c, d; 4a). Correlations between elevated temporal dispersal limitations and lower temporal stabilities in groundwater microbiomes were confirmed by a linear regression model (Fig. 2f).

Results of dbRDA analyses highlighted the importance of environmental selection, particularly homogeneous selection, in driving microbiome assembly in more hydrologically isolated groundwaters (Supplementary Data 2). Hydrochemical parameters statistically accounted for 45-46% and 12-30% of microbiome variation in more hydrologically isolated groundwaters and connected groundwaters, respectively. Groundwater level fluctuations yielded the greatest impacts, statistically accounting for 14-21% and 2-5% of microbiome variation in more hydrologically isolated and connected groundwaters, respectively (dbRDA, Supplementary Fig. 2).

Despite intermittent recharge, regression analyses revealed significant long-term declines in groundwater levels across all wells, ranging from 7 cm year−1 at well H14 to 126 cm year−1 at well H41 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Other hydrochemical parameters, such as temperature and nitrate, also varied over time. Although not all were directly correlated with groundwater levels, several showed indirect associations through their correlation with groundwater-level-sensitive parameters (Supplementary Fig. 7). These relationships indicate that shifts in groundwater levels, contributed to broader hydrochemical changes, significantly altering groundwater environments over time (Mantel test, P < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 1, 7).

Collectively, hydrochemical parameters, hydrological seasons and seepage-associated microbial input statistically accounted for 15–33% and 47–50% of microbiome variation in hydrologically connected and more isolated groundwaters, respectively (Supplementary Data 2).

Predicted functional profiles of groundwater microbiomes

PICRUSt2 identified 390 distinct MetaCyc metabolic pathways from 16S rRNA gene-sequence datasets. Much like the case for groundwater microbiome diversity, the predicted metabolic pathway compositions exhibited both sinusoidal patterns and long-term variability (except well H41 which exhibited only sinusoidal patterns; Fig. 5a). Compared to microbiome diversity metrics, the predicted metabolic pathway compositions exhibited higher temporal stability (mean Bray-Curtis similarity = 90-95%) and resilience (temporal turnover rates = 0.08-0.9% year-1; Figs. 2b and 5a).

a Temporal similarity of functional profiles predicted by PICRUSt2 using 16S rRNA gene-sequences; b Temporal similarity in groundwater metabolomes, shown alongside a subset of concurrently sampled groundwater microbiomes; c Temporal similarity of groundwater DOM compositions alongside a subset of concurrently sampled groundwater microbiomes. Bray-Curtis similarity (%) was used to assess temporal similarity in all panels. Points represent raw Bray-Curtis similarity values plotted against pairwise sampling time intervals. Regression lines and smoothing curves are added to visualize both linear turnover and potential sinusoidal trends. Mantel tests were conducted to assess correlations a between changes in predicted pathway and time; b between changes in microbiomes and metabolomes; c between changes in microbiomes and DOM. Sample sizes per well for mantel tests (a/b/c) are as follows: H14, n = 89/32/20; H32, n = 125/58/34; H41, n = 117/57/34; H43, n = 118/57/34; H51, n = 119/61/33; H52, n = 124/63/36; H53, n = 123/59/35.

Temporal patterns of groundwater dissolved organic matter

Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations ranged from below detection limit (<0.5 mg L−1) to 2.8 mg L−1, with higher concentrations detected in shallow wells H14, H43, and H32 (Supplementary Fig. 8). Variations in DOC statistically accounted for one to six percent of the microbiome variation in wells H41 and H43, which were most affected by hydrological seasons (dbRDA; Supplementary Fig. 2).

LC-HRMS-derived metabolomics revealed both long-term variability and, albeit weak, sinusoidal patterns in the organic landscape (Fig. 5b). Significant correlations were observed between variations in microbiome and metabolic compositions across all wells (Mantel test; Fig. 5b). Variations in metabolomes, indicated by Shannon indices and primary axes of Principal Coordinates Analyses (PCoA), statistically accounted for 11-16% and 39% of microbiome variation in hydrologically connected and more isolated groundwaters, respectively (dbRDA; Supplementary Fig. 2). Metabolome variation, together with hydrochemical parameters, hydrological seasons, and seepage-associated microbial input statistically accounted for 31-59% of microbiome variation, roughly 10% more than when metabolome variation was excluded (dbRDA; Supplementary Data 2). In addition, the temporal stability of metabolomes (34-45%) was more consistent across wells than that of groundwater microbiomes (per mean Bray-Curtis similarity; Fig. 3).

While bulk DOM compositions elucidated via DI-HRMS lacked significant correlation with microbiome variations (Mantel test; Fig. 5c), they exhibited greater resilience (lower turnover rates) and temporal stability (greater mean Bray-Curtis similarity: 79-84%; Figs. 3, 5c) than microbiomes.

Correlations between predicted microbial functions and DOM compound classes

To link DOM composition to microbial functions, we compared the compound classes inferred from DI-HRMS data to the predicted degradation pathways inferred from 16S rRNA gene-sequences (Supplementary Data 3). The relative abundances of most degradation pathways were significantly greater in microbiomes in hydrologically connected than their hydrologically more isolated counterparts (Wilcoxon test, P < 0.001), except for C1 compound utilization and polymeric compound degradation.

The relative abundances of two of the six DOM compound classes identified differed significantly between hydrologically connected and more isolated groundwaters (Fig. 6; Supplementary Fig. 9). Condensed aromatic structures, likely derived from Muschelkalk sediments and underlying Permian/Jurassic formations, terrestrial plant material, or microbial necromass38,39,40, were more abundant in hydrologically connected groundwaters (0.15–0.4% vs. 0.04–0.08%; Wilcoxon test, P < 0.01; Fig. 6). This suggests that higher levels of condensed aromatics corresponded to increased relative abundance of predicted degradation pathways for these compounds (Fig. 6). Conversely, relative abundances of peptide-like DOM, potentially sourced from extracellular enzymes and microbial necromass39, were significantly lower in hydrologically connected groundwaters (0.12–0.2% vs. 0.22–0.36%; Fig. 6). Yet, microbiomes in hydrologically connected groundwaters exhibited a greater relative abundance of predicted amino acid degradation pathways, even though their potential ability to synthesize them was not consistently lower (Fig. 6; Supplementary Fig. 10). This suggests that these communities recycle environmental proteins to a greater extent than their counterparts in more hydrologically isolated groundwater.

a Predicted degradation pathways inferred from 16S rRNA gene-sequences using PICRUSt2. b DOM compound classes derived from bulk DOM via DI-HRMS. Red horizontal lines denote the mean values across wells. Sample size for comparisons between hydrologically connected wells and more isolated wells are as follows: aromatic compound and amino acid degradation, n = 443 vs 247; condensed aromatic structure and peptide-like DOM compounds, n = 155 vs 71.

Between 2020 and 2021, a period of sustained elevation in the relative abundance of condensed aromatic structures and unsaturated hydrocarbons was identified at shallow wells H14 and H32 (and others; Supplementary Fig. 11). Mean relative abundances of condensed aromatics rose from 0.28% to 0.51% and from 0.2% to 0.42% (Wilcoxon test, P < 0.01), while unsaturated hydrocarbons increased from 2.9% to 3.7% and from 2.2% to 3.8% at wells H14 and H32, respectively (Wilcoxon test, P < 0.01). Following these increases, the relative abundance of predicted degradation pathways for aromatics and carboxylic acids at H14 and H32 rose significantly beginning in March 2021. The relative abundance of predicted aromatic degradation pathways increased from 0.4% to 1.6% at H14 and from 0.06% to 1% at H32 (Wilcoxon test, P < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 11). Similarly, predicted carboxylic acid degradation pathways increased from 0.3% to 0.7% and from 0.07% to 0.3% at wells H14 and H32, respectively (Wilcoxon test, P < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 11). Since March 2021, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria also rose significantly compared to previous levels, rising from 30.4% to 69.6% at H14 and from 15.7% to 34.7% at H32 (Wilcoxon test, P < 0.001; Fig. 1b). These results suggest delayed changes in microbial composition and function in response to changes in DOM in shallow groundwater wells.

Discussion

Our decade-long study of groundwater microbiomes unveiled hydrological seasonality and long-term variability, challenging the traditional view of groundwater microbiomes as static enteties7,36,41. Trends of continuous change in groundwater microbiomes were previously reported by Yan et al.13 from the same study sites, but sinusoidal patterns emerged only with this 10-year analysis. These patterns follow local seasonal hydrological changes, with hydrochemical parameters exhibiting annual sinusoidal patterns corresponding to groundwater level variations driven by meteoric recharge5 (Supplementary Fig. 1, 6, 7). Similar periodic groundwater level fluctuations have been observed in other shallow aquifers (<100 m depth), especially in karst systems10,11,12. Sinusoidal patterns in subsurface microbiomes were never reported, however, even though shifts resulting from environmental changes were reported12,22,42, perhaps owing to shorter study periods and/or lower observation frequencies. Annual sinusoidal patterns, driven by seasonal factors (e.g., day length, temperature, nutrient availability), are common in long-term studies of marine and lake environments, particularly marine surface layers26,27,43,44.

Sinusoidal patterns in subsurface microbiome diversity may arise from specific microorganisms being periodically favored by fluctuating environmental conditions, such as redox potential and/or groundwater levels11,13. Microorganisms benefitting from high groundwater levels include those remobilized from rock surfaces in the vadose zone, as local carbonate rocks and planktonic groundwater communities share up to 40% species diversity45. This fraction might be even higher in porous aquifers46, rendering them important seeding banks for groundwater microbiomes21. In addition to enhancing microbiome stability by increasing homogeneous selection (e.g., well H41; Fig. 2e), the sinusoidal patterns characterized in this study drastically improve predictions of microbiome change47,48.

The Hainich CZE provides an ideal setting to study microbiome stability in carbonate-rock aquifers of varying hydrological connectivity. Our extended in-depth characterization of seven selected wells considered several distinct microbiomes along the groundwater monitoring transect49, revealing contrasting temporal patterns and stability in groundwater microbiomes over a mere 6 km. The microbiomes of more isolated groundwaters with high temporal stability (e.g., wells H52 and H53) are influenced largely by deterministic processes, while those in hydrologically connected groundwaters are shaped by stochastic processes (and as such exhibit lower temporal stability). In well H32, an intermediate aquifer system, groundwater microbiomes exhibited both elevated short- and long-term variability, reflecting sporadic hydrological connectivity likely resulting from complex flows in fractured sedimentary bedrock aquifers5.

Our results corroborate the findings of recent groundwater studies in other geological settings11,50,51, suggesting that hydrological connectivity reduces the temporal stability of groundwater microbiomes by increasing the role of temporal dispersal limitation via microbial immigration. Thus, hydrological connectivity lowers the resistance of the groundwater microbiome while increasing its resilience. Furthermore, microbial immigration during recurrent groundwater recharge events represents intermittent disturbances that promote resilience and create opportunities for coexistence by preventing competitive exclusion, thereby promoting diversity52.

In near-surface aquifers, seepage-associated microbial input is a key contributor of microbial immigration, increasing the importance of temporal dispersal limitation in microbiome assembly20,22. Our findings suggest that 0.2–8.9% of the total groundwater microbiome is seepage-borne, likely derived during periodic groundwater recharge or single hydrological extreme events (particularly relevant in karst systems). Recurrent immigration events over thousands of years may have enhanced the persistence of these invaders (e.g., Sphingobium and Rhodoferax) in the groundwater microbiome, contributing to their important role in carbon, nitrogen, and iron cycling15,53, as up to 12.5% of groundwater core ASVs have been identified as being seepage-associated. These estimates are based on pooled seepage communities and may smooth over temporal fluctuations in microbial inputs, which is an approach commonly used to account for spatiotemporal variability and to ensure broad taxonomic representation14,54. As these invasive taxa survive and partake in community coalescence, they compete with resident taxa for resources, and closely related species compete for similar resources55. Such competition between species oftentimes results in divergence in niches, including increased host specificity of episymbiotic microorgansisms (e.g., Patescibacteria), to reduce competition costs56.

The predicted functional profiles of all seven groundwater microbiomes exhibited remarkable temporal stability and resilience despite notable variations in community composition. While not all predicted functions are necessarily expressed, key biogeochemical functions such as nitrification, annammox and carbon fixation have been confirmed for selected time points through metatranscriptomic and activity-based studies at the same field site53,57,58,59. This high temporal stability and resilience of predicted functional profiles also aligns with findings from a groundwater study that used GeoChip to directly detect functional genes and reported high functional redundancy in these ecosystems11. Functional redundancy, i.e., multiple microbial taxa performing overlapping ecological roles, ensures ecosystem stability amid species turnover60. The observed resiliencies in predicted functional profiles suggest that, despite environmental fluctuations, these microbial communities might retain the capacity to adapt while maintaining their functional integrity8,21. Significant correlations were observed between microbiome and metabolome changes, pointing to a form of functional redundancy achieved through metabolic diversity. Such a mechanism enables different microbial taxa to produce varied metabolites that fulfill similar ecological functions61. Metabolome compositions exhibited greater temporal consistency across wells than microbiomes. This stands to reason as not all detected metabolites are microorganism-related, which in and of itself highlights the influence of additional controlling factors29,31. The lower temporal stability of groundwater metabolomes compared to corresponding microbiomes’ elevated predicted functional profiles corroborates earlier findings, which reported substantial metabolome variability at the same site30.

Distinct temporal patterns were observed in groundwater metabolome and DOM compositions, largely attributable to differences in analytical methods that preferentially target different compound classes14,30. The high temporal stability of DOM across wells may result from its composition, which consists of lignin-degradation products and polyphenolic leachates from plant matter in topsoil36,62,63 (Supplementary Fig. 9). These compounds resist microbial degradation, contributing to their persistence in the environment36,62,63. Despite comprising less than 5% of total DOM, the microorganism-associated DOM fraction likely plays an important role in subsurface organic matter cycling. Its influence on spatial and temporal variation in microbiome composition and function36,64,65 was particularly evident in the shallowest well (e.g., H14, H32). The contrasting dynamics observed between DOM and metabolomes emphasize the value of integrating diverse analytical approaches29,33.

This long-term study shows that contrasting hydrogeological conditions render the Hainich CZE an ideal setting to elucidate the various mechanisms driving groundwater microbiome stability and vulnerability in carbonate-rock aquifers. Highly karstified regions, rich with extensive fractures and conduits, are globally crucial for drinking water as they facilitate rapid groundwater flow and abundant water storage (in contrast to less permeable, dense carbonate rocks)4. As a result, microbiomes in these systems are more strongly shaped by stochastic processes and are more susceptible to disturbances from surface-derived inputs (e.g., organic contaminants, pathogens)22,65,66,67. These vulnerabilities underscore the need for effective surface management to protect groundwater quality in hydrologically connected groundwaters (e.g., karst aquifers)24.

Hydroclimatic extremes, such as heavy precipitation and drought, can exacerbate groundwater vulnerability, particularly in highly connected systems. During the study period, both an extreme flood event (2013)68 and a severe drought (2018)69 were recorded. In 2013, groundwater levels peaked across all hydrologically connected wells, marking the highest levels in the 10-year monitoring period (Supplementary Fig. 6). Weak but significant correlations between precipitation and groundwater levels (Supplementary Fig. 6), and between seepage-associated microorganisms and groundwater levels at the shallowest well (H14, Fig. 4b), suggest that heavy rainfall can transiently alter microbiomes by introducing surface-derived taxa. Rising groundwater levels may also mobilize microorganisms attached to the rock matrix or residing in the vadose zone45,70. These findings align with earlier reports of pathogen influx during recharge events, especially in karst aquifers22,71.

In contrast to this rapid response to intense precipitation, the effects of drought were more delayed. Only well H14 reached its lowest level during the 2018 drought, while most other wells reached minima between 2019 and 2021, likely due to sustained low precipitation. Although immediate microbiome shifts were not observed after the 2018 drought69, previous studies have shown that such extremes can enhance the infiltration of surface-derived organic molecules (e.g., xenobiotics) by bypassing microbial processing14. Supporting this, we detected significant post-2018 changes in predicted microbial degradation pathways and in microbiome composition at the shallowest wells (H14 and H32; Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 12). These results suggest that prolonged droughts may lead to delayed but cumulated shifts in microbiome function72, likely driven by gradual changes in DOM6,65.

While microbiomes in highly connected aquifers respond rapidly to hydrological extremes, those in more hydrologically isolated groundwaters (e.g., dense limestone formations) are typically shaped by deterministic processes and tend to resist short-term disturbances73,74. However, our data show that even in these systems, long-term environmental changes—especially declining groundwater levels—can erode microbiome stability over time. Groundwater level fluctuations explained 14–21% of the microbiome variation in these isolated aquifers (dbRDA; P < 0.001).

Hydrochemical parameters, including key electron acceptors such as dissolved oxygen, nitrate and sulfate, exhibited direct or indirect significant correlations with groundwater level changes (Supplementary Fig. 7). In these more hydrologically isolated systems, which are considered anoxic environments (dissolved oxygen <0.25 mg L−1), redox-active compounds accounted for a notable portion of microbiome variation: nitrate (3–9%), sulfate (4%) and oxygen (2–5%) (dbRDA; P < 0.05). Ammonium, both a nitrogen source and electron donor, explained 7–13% of the variation, consistent with the activity of chemolithoautotrophs like Nitrospiria and Brocadia53,57,75,76. An additional driver of community turnover may be the high relative abundance of Patescibacteria (mean 36–41%), which represents the Candidate Phyla Radiation (CPR). CPR organisms are known to influence host dynamics through parasitism77 and contribute to biogeochemical cycling through metabolic cooperation and resource exchange with other microbial taxa15,18,78.

Together, these findings underscore the sensitivity of groundwater microbiomes to both abrupt and gradual environmental changes. Highly connected aquifers are particularly vulnerable to short-term perturbations such as floods, while isolated systems may undergo slow but profound shifts in response to long-term hydrological decline—highlighting the diverse pathways through which hydroclimatic extremes can shape subsurface microbial ecosystems.

Conclusion

Overall, this study demonstrates that both hydrologically connected and more isolated groundwater ecosystems in carbonate aquifers respond to hydrological fluctuations in distinct yet consequential ways. As hydroclimatic extremes become more frequent and intense, understanding the stability and adaptability of subsurface microbial communities is critical for predicting shifts in ecosystem function. Our findings underscore the importance of long-term monitoring and integrated hydroecological research to inform sustainable groundwater management in the face of accelerating environmental changes.

Methods

Study sites and sampling

The study site is located in the Hainich CZE in central Germany, a well-instrumented field site to investigate the links between surface and subsurface processes along a 5.4 km hillslope transect. Detailed site information and sampling procedures can be found in Kohlhepp et al.23, Küsel et al.35, and Lehmann and Totsche5. Briefly, the CZE features a geological setting of alternating thin–bedded limestone and mudstone, characteristic of Upper Muschelkalk formation of the Germanic Triassic. These marine carbonates are widespread across central Europe and represent a common aquifer system. The low-mountain hillslope setting harbors a sequence of structurally and hydrogeologically distinct aquifers that differ in their connectivity to surface recharge zones, providing a natural laboratory to study gradients in hydrological isolation.

In this study, we sampled seven groundwater monitoring wells (Supplementary Fig. 1a), encompassing a range of topographic positions, lithologies, and aquiferdepths5,23,35. The aquifers accessed by these wells exhibit pronounced contrasts in oxygen availability and redox potential: wells H14, H32, H41, and H51 are oxic (redox potentials ~400 mV), H43 is suboxic (<1 mg L−1 dissolved oxygen), and H52 and H53 are anoxic (<0.25 mg L−1 dissolved oxygen; redox potentials ~200 mV). These redox patterns reflect the underlying hydrogeological conditions and degree of isolation.

Wells tapping into the limestone-dominated Trochitenkalk formation (e.g., H14, H41), the regional main aquifer, represent groundwaters with strong surface connectivity, receiving direct recharge via outcropping intake areas and rapid flow paths that bypass low-permeability overburden5,23,35. In contrast, the footslope wells H52 and H53 penetrate thinner-bedded, less fractured mudstone formations with minimal surface input and older carbon sources (~4500–12,000 years vs. ~1000 years at more connected wells)5,36,37. Despite similar depths, these compartments vary in recharge dynamics, geochemistry, and microbiological characteristics.

The wells are situated across areas of mixed land usage (forest, pasture, and cropland), but land use was not included as a direct variable in this study, as prior research at the site has shown that recharge patterns, rather than surface use, are the dominant drivers of groundwater biogeochemistry5. Importantly, the shallowest well (H14), located at the upper slope, is situated within the preferential recharge zone and exemplifies a highly dynamic, surface-connected groundwater environment.

This natural gradient in hydrological connectivity allows for a comparative analysis of microbiome composition and stability across contrasting groundwater environments—from oxygenated, surface-connected systems to long-term anoxic aquifers more isolated from recent surface inputs.

The groundwater microbiomes and hydrochemical parameters were sampled mostly every 28 days, with some variation between 21 and 35 days, from February 2013 to November 2021, resulting in approximately 13 samples per year per well. Since December 2021, the sampling interval has been extended to every 42 days. In total, 815 samples were collected, with a few sampling gaps, and the detailed sampling schedule is provided in Supplementary Fig. 12. Additionally, 387 untargeted groundwater metabolomics samples (collected at approximately monthly intervals) and 226 DOM samples (collected every three months) were obtained between July 2014 and February 2023, despite sampling gaps. The detailed sample schedules can also be found in Supplementary Fig. 12.

Once the physico–chemical parameters of pumped groundwater stabilized, groundwater was collected from each well using a submersible pump (MPI, Grundfos) and placed into sterilized bottles. These samples included 5–10 L for microbiological analysis, duplicate 10 L samples for DOM analysis, triplicate 5 L samples for metabolomics, and 100 mL for DOC concentration measurements. Groundwaters from which to isolate genomic DNA were processed through 0.2 µm filters (PES or polycarbonate from Supor, Pall Corporation and Merck–Millipore, respectively) via vacuum pumping, and filters were stored at –80 °C prior to DNA extraction. Acidified filtered groundwaters (0.7 µm filters, pH = 2 with HCl) were stored at 4 °C in the dark until further DOM processing, while raw groundwaters were stored in the dark and chilled until further metabolomics analyses. Other groundwaters were filtered through 0.7 µm filters and stored at 4 °C in the dark until further DOC quantification.

Groundwater hydrochemical parameters including groundwater levels, temperature, pH, specific electrical conductivity (EC25; reference T: 25 °C), dissolved oxygen content, redox potential (ORP), acidity (neutralizing capacity), alkalinity (neutralizing capacity), total inorganic carbon (TIC), and ion concentrations were measured as described by Lehmann and Totsche5 and Kohlhepp et al.23. Element concentration including Ca, K, Mg, Na, and S were measured with ICP-MS (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry; 8900 Triple Quadrupole ICP-MS, Agilent, Germany), while major anions Cl- was measured by IC (ion chromatography; Dionex IC20, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). DOC concentration was quantified as non-purgeable organic carbon on a vario TOC cube (Elementar Analysensysteme, Germany) with a detection limit of 0.5 mg L−1.

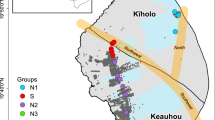

The sampling details for the 174 seepage samples collected between June 2016 and February 2018 in this study can be found in Hermann et al.16 and Lehmann et al79. (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Data 4). Seepage sites were sampled regularly (biweekly) and on an event-basis (weekly). Seepage volumes ranging from 100 to 500 mL were filtered through 0.2 µm filters (PES; Supor, Pall Corporation) using a vacuum pump, and filters were stored at –80 °C prior to DNA extraction.

DNA extraction and amplicon sequencing

Groundwater and seepage genomic DNA were extracted using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) per manufacturer’s instructions, and extractions were stored at –20 °C prior to PCR amplification. PCR amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA gene (V3–V4 region) was performed on an Illumina Miseq platform using v3 chemistry with primers Bakt_0341F and Bakt_0785R80. Most samples (see list in Supplementary Data 5) were sequenced in–house following the two–step PCR library preparation procedures described by Krüger et al.17. Amplicon libraries for some samples were generated using the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, MA), following methods detailed by Kumar et al.81. All remaining samples were processed at LGC Genomics (Berlin, Germany), as previously described82.

Molecular composition of DOM

A detailed description of the methods used to elucidate the molecular compositions of DOM is given in Schroeter et al.14 Briefly, DOM was extracted from acidified filtered groundwater via solid phase extraction with PPL (styrene–divinylbenzene polymer) Bond Elut cartridges (Agilent Technologies) following the protocols of Dittmar et al.83. After extraction on PPL columns, the methanol DOM extracts were stored at −80 °C until the DI-HRMS analyses, which followed within a year. DI-HRMS analyses were conducted on an Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with a mass resolution of 555,000 ± 9000 at m/z = 251. The electrospray ionization (ESI) was run in negative mode with an ESI needle voltage of 2.65 kV. For each sample, 100 scans of m/z 100–1000 were acquired and averaged. Quality controls and molecular formula assignments were processed using DOMAssignR (https://github.com/simonschroeter/DOMAssignR). Spectra were further normalized to sum all peak intensities. All the DOM extracts prepared throughout ten years of observations were analyzed in batches over the course of the study. An in-house groundwater DOM extract was used as a standard with the analysis of each batch to evaluate the stability of measurement. An evaluation of these standards is available in Schroeter et al.14. We focused on DOM compound classes most likely to serve as substrates for microorganisms, including carbohydrates, condensed aromatic structures, lignins, lipids, peptide-like compounds, and unsaturated hydrocarbons. Identification of DOM compound classes was based on their elemental N content and hydrogen/carbon and/or oxygen/carbon elemental ratios (Supplementary Data 6) according to Liu et al.84 and Antony et al.85.

Untargeted metabolomics

Sample extraction and analyses are described in detail in Zerfaß et al.30 Briefly, 5 L of filtered (GF/C, 1.5 µm, VWR) groundwater was subjected to solid phase extraction (SPE) in Strata–X 33 µm polymeric reversed phase cartridges (Phenomenex). Eluates (1:1 methanol:acetonitril) were dried (vacuum, nitrogen stream), and the organic residue was re-dissolved in 100 µl of 1:1 THF:methanol. Extracts (1 µl) were then analyzed by LC–HRMS (liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry) on a Dionex UltiMate 3000 chromatography system coupled to a Q–Exactive Plus orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), m/z-range 100–1500, alternating acquisition in positive and negative mode. For this study, only positive-mode data were extracted.

To assure system suitability in the long-term sampling experiment, the LC-HRMS system was maintained with a weekly MS source cleaning, mass calibration, and consistency-check by injection of a standard (containing Fluorophenylalanine, P-Fluorobenzoic acid, Decanoic acid D-19) for which retention times and peak apex intensities were recorded. All samples were taken in environmental replicates and injected in triplicate analytical replicates, and each set of analytical replicates was processed in randomized sequence. For operational reasons, the time between sampling and LC-HRMS injection varied; meanwhile, the THF:methanol-dissolved extracts were kept at −20 °C, for a median storage time of 94 days (25/75% quantile 33 and 560 days; min/max 7 and 959 days). Data processing for peak picking and feature assignment was carried out in XCMS as described in the stated reference. For Bray-Curtis similarity tests (details in succeeding section), replicate means were calculated, and peak areas were normalized by the sum of all feature peak areas.

Bioinformatics and statistical analyses

Most bioinformatics and/or statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.2.286 at a significance level of α = 0.05. After correcting the orientation of mixed-orientation reads and removing primers with Cutadapt87 (v 4.1), R package “dada2”88 (v1.26) was employed for quality filtering, denoising, inferring amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), and removing chimeras. Reads were truncated to 265 bp (forward reads) or 235 bp (reverse reads), excluding those with more than two expected errors and those truncated when the quality score was equal to or less than two. ASVs were generated by applying the DADA2 core algorithm and combining forward and reverse reads, and those that could not be aligned to the SILVA reference database89 (v138.1) using Mothur (v1.46.1) were removed. After removing chimeric sequences, taxonomy was assigned to the remaining ASVs based on the SILVA taxonomy reference database v138.1. Further downstream sequence analysis was conducted using the R package “phyloseq”90 (v1.42), and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using FastTree91 (v2.1) after aligning genes with Muscle92 (v5) and trimming the alignment with trimAl93 (v1.4).

Recharge and recession phases (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Data 5) were defined by observed changes in daily groundwater levels. The recession phase was characterized by a sustained decline in groundwater levels for more than five consecutive days, ending in a minimum level or (for well H14) a notable rise to or above the maximum level for that phase. The recharge phase was defined in the opposite manner. We considered one hydrological year (between 1 May and 30 Apr) comprising four seasons: hydrological early summer (May to Jul), late summer (Aug to Oct), early winter (Nov to Jan), and late winter (Feb to Apr). To visualize the heterogeneity of groundwater environments, principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted with 15 hydrochemical parameters, including water level, water temperature, specific electrical conductivity, pH values, dissolved oxygen concentration, redox potential, acidity, alkalinity, total inorganic carbon, element and ion concentration (Cl–, S, Ca, K, Na, and Mg). Pearson and Spearman correlations from Hmisc (Rpackage v5.1-1) were used to determine significant correlations.

Temporal stability, referring to the consistency of a microbiome’s composition and function over time21,94, was assessed using the mean pairwise Bray-Curtis similarity of groundwater microbiome composition and their predicted functional profiles. Resistance, defined as a community’s ability to withstand environmental changes21, was evaluated by comparing the short-term variability between groundwater hydrochemical parameters and microbiome compositions. Short-term variability was calculated using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity for microbiome sample pairs and Euclidean dissimilarity for hydrochemical parameters, using samples collected from the same well with sampling intervals of 15 to 44 days. Resilience, referring to the ability of groundwater microbiomes to maintain their composition and predicted functional profiles over time despite ongoing environmental changes21,26, was estimated based on the temporal turnover rates. The resilience was calculated as the slope of the regression model describing changes in similarity (Bray-Curtis) over increasing time intervals for both community composition and predicted functional profiles. Hydrological seasonality in groundwater microbiome composition was identified by applying a moving average filter to pairwise Bray-Curtis similarities grouped into monthly intervals (e.g., a time interval of 1 month: 15–44 days; a time interval of 2 months: 45–74 days) aligned with other studies in aquatic systems26,94,95.

The same method was applied to groundwater DOM and metabolomes using Bray-Curtis similarity, groundwater microbiome compositions at the phylogenetic level using UniFrac similarity, and environmental parameters using Euclidean similarity. The Bray-Curtis similarity (dissimilarty) and UniFrac similarity (dissimilarity) mentioned in this manuscript were based on relative abundance, while the Euclidean similarity (dissimilarity) was calculated after normalizing the aforementioned 15 hydrochemical parameters to exclude the effect(s) of absolute abundance (values) differences. Variation assigned to short-term or long-term variability is represented as the proportion of the respective variability in one-decade variability. We first evaluated the 10-year variability of microbiome compositions using the regression model of raw pairwise Bray-Curtis similarity, at which time long-term variability is then calculated by subtracting the aforementioned short-term variability from the 10-year variability.

To elucidate the impact of surface-subsurface connectivity in the temporal stability of groundwater microbial communities, we tracked changes in contribution of seepage-associated microorganisms to the groundwater microbiome via SourceTracker96 (Rpackage v1.0.1 under R version 4.0.0). All seepage samples were pooled and treated as the source, while groundwater samples were treated as the sink. Pooling the seepage samples helps to integrate spatial and temporal variability in the source microbiomes and compensates for differences in sampling sizes between seepage and groundwater. It also accounts for variation in microbial survival and travel times driven by local hydrological heterogeneity and precipitation patterns. Analyses were performed on rarefied ASV (rarefaction depth of 1000 reads) abundances using default settings (α = 0.001, β1 and β2: 0.01).

In this study, we define core species as bacterial ASVs present in >80% of the groundwater samples collected in every well. Distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity was carried out to assess and validate whether selected environmental parameters (e.g., hydrological seasons, incidence of seepage-associated microorganisms) significantly impact groundwater microbiome composition (Rpackage vegan; adjusted R2 was used). The significance of dbRDA tests was reported by permutation tests of “anova.cca”. The metabolic functions of groundwater microbial communities were predicted by PICRUSt2 software based on taxonomy annotations from 16S rRNA gene sequences34. We employed inferred community assembly mechanisms using a phylogenetic bin-based null model (iCAMP, Rpackage v1.6.5) to evaluate the contribution of ecological processes on groundwater microbiome assembly97. All analyses were performed using recommended default settings with 48 bins and confidence for null model significant tests.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Raw amplicon sequencing data reads for all studied samples have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive, either previously13,15,16,36,45,49,57,59,98,99,100 or along with this study (details in the Supplementary Data 5). Raw DOM data from DI-HRMS were deposited under https://doi.org/10.17617/3.2TZM6C, while raw metabolome data from LC-HRMS were deposited via the Metabolights repository101 under MTBLS3450, MTBLS8433, and MTBLS11375. Groundwater hydrochemical parameters are provided as Supplementary Data 5. Supplementary Data 1-6 are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29716199.

Code availability

The codes for amplicon sequencing raw data processing, statistical evaluations, and plotting of figures is available via Github at https://github.com/Hewang11111/GWmicrobiome.

References

Gleeson, T., Wada, Y., Bierkens, M. F. P. & Van Beek, L. P. H. Water balance of global aquifers revealed by groundwater footprint. Nature 488, 197–200 (2012).

Rodell, M. et al. Emerging trends in global freshwater availability. Nature 557, 651–659 (2018).

Cuthbert, M. O. et al. Observed controls on resilience of groundwater to climate variability in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature 572, 230–234 (2019).

Ford, D. & Williams, P. Karst Hydrogeology and Geomorphology. John Wiley Sons (2007).

Lehmann, R. & Totsche, K. U. Multi-directional flow dynamics shape groundwater quality in sloping bedrock strata. J. Hydrol. 580, 124291 (2020).

Retter, A., Karwautz, C. & Griebler, C. Groundwater microbial communities in times of climate Change. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 41, 509–538 (2021).

Griebler, C. & Lueders, T. Microbial biodiversity in groundwater ecosystems. Freshw. Biol. 54, 649–677 (2009).

Griffiths, B. S. & Philippot, L. Insights into the resistance and resilience of the soil microbial community. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 112–129 (2013).

Philippot, L., Griffiths, B. S. & Langenheder, S. Microbial Community Resilience across Ecosystems and Multiple Disturbances. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 85, e00026–20 (2021).

Lin, X. et al. Spatial and temporal dynamics of the microbial community in the Hanford unconfined aquifer. ISME J. 6, 1665–1676 (2012).

Zelaya, A. J. et al. High spatiotemporal variability of bacterial diversity over short time scales with unique hydrochemical associations within a shallow aquifer. Water Res. 164, 114917 (2019).

Zhou, Y., Kellermann, C. & Griebler, C. Spatio-temporal patterns of microbial communities in a hydrologically dynamic pristine aquifer. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 81, 230–242 (2012).

Yan, L. et al. Groundwater bacterial communities evolve over time in response to recharge. Water Res. 201, 117290 (2021).

Schroeter, S. A. et al. Hydroclimatic extremes threaten groundwater quality and stability. Nat. Commun. 16, 720 (2025).

Herrmann, M. et al. Predominance of Cand. Patescibacteria in groundwater is caused by their preferential mobilization from soils and flourishing under oligotrophic conditions. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1407 (2019).

Herrmann, M., Lehmann, K., Totsche, K. U. & Küsel, K. Seepage-mediated export of bacteria from soil is taxon-specific and driven by seasonal infiltration regimes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 187, 109192 (2023).

Krüger, M. et al. Drought and rewetting events enhance nitrate leaching and seepage-mediated translocation of microbes from beech forest soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 154, 108153 (2021).

Chaudhari, N. M., Pérez-Carrascal, O. M., Overholt, W. A., Totsche, K. U. & Küsel, K. Genome streamlining in Parcubacteria transitioning from soil to groundwater. Environ. Microbiome 19, 41 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Huang, C., Zhang, W., Chen, J. & Wang, L. The concept, approach, and future research of hydrological connectivity and its assessment at multiscales. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 52724–52743 (2021).

Zhong, S. et al. Ecological differentiation and assembly processes of abundant and rare bacterial subcommunities in karst groundwater. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1111383 (2023).

Shade, A. et al. Fundamentals of microbial community resistance and resilience. Front. Microbiol. 3, 417 (2012).

Chik, A. H. S. et al. Evaluation of groundwater bacterial community composition to inform waterborne pathogen vulnerability assessments. Sci. Total Environ. 743, 140472 (2020).

Kohlhepp, B. et al. Aquifer configuration and geostructural links control the groundwater quality in thin-bedded carbonate–siliciclastic alternations of the Hainich CZE, central Germany. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 6091–6116 (2017).

Campanale, C., Losacco, D., Triozzi, M., Massarelli, C. & Uricchio, V. F. An overall perspective for the study of emerging contaminants in karst aquifers. Resources 11, 105 (2022).

Hose, G. C. et al. Assessing groundwater ecosystem health, status, and services. In Groundwater Ecology and Evolution 501–524 (Academic Press, London, 2023).

Fuhrman, J. A., Cram, J. A. & Needham, D. M. Marine microbial community dynamics and their ecological interpretation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 133–146 (2015).

Aguilar, P. & Sommaruga, R. The balance between deterministic and stochastic processes in structuring lake bacterioplankton community over time. Mol. Ecol. 29, 3117–3130 (2020).

Riekeberg, E. & Powers, R. New frontiers in metabolomics: from measurement to insight. F1000Research 6, 1148 (2017).

Pemberton, J. A. et al. Untargeted characterisation of dissolved organic matter contributions to rivers from anthropogenic point sources using direct-infusion and high-performance liquid chromatography/Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 34, e8618 (2020).

Zerfaß, C. et al. Groundwater metabolome responds to recharge in fractured sedimentary strata. Water Res. 223, 118998 (2022).

Zerfaß, C., Lehmann, R., Ueberschaar, N., Totsche, K. U. & Pohnert, G. Current-use and legacy contaminants evidence dissolved organic matter transfer and dynamics across a fractured-rock groundwater recharge area. bioRxiv 2024-06 (2024).

Grasset, C., Groeneveld, M., Tranvik, L. J., Robertson, L. P. & Hawkes, J. A. Hydrophilic species are the most biodegradable components of freshwater dissolved organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 13463–13472 (2023).

Catalá, T. S., Shorte, S. & Dittmar, T. Marine dissolved organic matter: a vast and unexplored molecular space. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 105, 7225–7239 (2021).

Douglas, G. M. et al. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 669–673 (2020).

Küsel, K. et al. How deep can surface signals be traced in the critical zone? Merging biodiversity with biogeochemistry research in a central German Muschelkalk landscape. Front. Earth Sci. 4, 32 (2016).

Benk, S. A. et al. Fueling diversity in the subsurface: Composition and age of dissolved organic matter in the critical zone. Front. Earth Sci. 7, 296 (2019).

Nowak, M. E. et al. Carbon isotopes of dissolved inorganic carbon reflect utilization of different carbon sources by microbial communities in two limestone aquifer assemblages. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 4283–4300 (2017).

Schwab, V. F. et al. 14C-free carbon Is a major contributor to cellular biomass in geochemically distinct groundwater of shallow sedimentary bedrock aquifers. Water Resour. Res. 55, 2104–2121 (2019).

Geesink, P., Taubert, M., Jehmlich, N., Von Bergen, M. & Küsel, K. Bacterial necromass is rapidly metabolized by heterotrophic bacteria and supports multiple trophic levels of the groundwater microbiome. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e00437–22 (2022).

Mead, R. N. et al. Insights into dissolved organic matter complexity in rainwater from continental and coastal storms by ultrahigh resolution Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 4829–4838 (2013).

Farnleitner, A. H. et al. Bacterial dynamics in spring water of alpine karst aquifers indicates the presence of stable autochthonous microbial endokarst communities. Environ. Microbiol. 7, 1248–1259 (2005).

Villeneuve, K., Violette, M. & Lazar, C. S. From recharge, to groundwater, to discharge areas in aquifer systems in Quebec (Canada): Shaping of microbial diversity and community structure by environmental factors. Genes 14, 1 (2022).

Chow, C.-E. T. et al. Temporal variability and coherence of euphotic zone bacterial communities over a decade in the Southern California Bight. ISME J. 7, 2259–2273 (2013).

Cram, J. A. et al. Seasonal and interannual variability of the marine bacterioplankton community throughout the water column over ten years. ISME J. 9, 563–580 (2015).

Sharma, A. et al. Iron coatings on carbonate rocks shape the attached bacterial aquifer community. Sci. Total Environ. 917, 170384 (2024).

Lehman, R. M., Colwell, F. S. & Bala, G. A. Attached and unattached microbial communities in a simulated basalt aquifer under fracture- and porous-flow conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 2799–2809 (2001).

Fuhrman, J. A. et al. Annually reoccurring bacterial communities are predictable from ocean conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 13104–13109 (2006).

Gilbert, J. A. et al. Defining seasonal marine microbial community dynamics. ISME J. 6, 298–308 (2012).

Yan, L. et al. Environmental selection shapes the formation of near-surface groundwater microbiomes. Water Res. 170, 115341 (2020).

Ning, D. et al. Environmental stress mediates groundwater microbial community assembly. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 490–501 (2024).

Merino, N. et al. Subsurface microbial communities as a tool for characterizing regional-scale groundwater flow. Sci. Total Environ. 842, 156768 (2022).

Roxburgh, S. H., Shea, K. & Wilson, J. B. The intermediate disturbance hypothesis: Patch dynamics and mechanisms of species coexistence. Ecology 85, 359–371 (2004).

Wegner, C.-E. et al. Biogeochemical regimes in shallow aquifers reflect the metabolic coupling of the elements nitrogen, sulfur, and carbon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85, e02346–18 (2019).

Fillinger, L., Hug, K. & Griebler, C. Aquifer recharge viewed through the lens of microbial community ecology: Initial disturbance response, and impacts of species sorting versus mass effects on microbial community assembly in groundwater during riverbank filtration. Water Res. 189, 116631 (2021).

Liu, X. & Salles, J. F. Lose-lose consequences of bacterial community-driven invasions in soil. Microbiome 12, 57 (2024).

Reif, J., Reifová, R., Skoracka, A. & Kuczyński, L. Competition-driven niche segregation on a landscape scale: Evidence for escaping from syntopy towards allotopy in two coexisting sibling passerine species. J. Anim. Ecol. 87, 774–789 (2018).

Kumar, S. et al. Nitrogen Loss from Pristine Carbonate-Rock Aquifers of the Hainich Critical Zone Exploratory (Germany) Is Primarily Driven by Chemolithoautotrophic Anammox Processes. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1951 (2017).

Overholt, W. A. et al. Carbon fixation rates in groundwater similar to those in oligotrophic marine systems. Nat. Geosci. 15, 561–567 (2022).

Krüger, M. et al. Differential contribution of nitrifying prokaryotes to groundwater nitrification. ISME J. 17, 1601–1611 (2023).

Allison, S. D. & Martiny, J. B. H. Resistance, resilience, and redundancy in microbial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 11512–11519 (2008).

Shaffer, J. P. et al. Standardized multi-omics of Earth’s microbiomes reveals microbial and metabolite diversity. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 2128–2150 (2022).

Hu, A. et al. Microbial and environmental processes shape the link between organic matter functional traits and composition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 10504–10516 (2022).

Sumranwanich, T. et al. Evaluating lignin degradation under limited oxygen conditions by bacterial isolates from forest soil. Sci. Rep. 14, 13350 (2024).

Osterholz, H. et al. Terrigenous dissolved organic matter persists in the energy-limited deep groundwaters of the Fennoscandian Shield. Nat. Commun. 13, 4837 (2022).

Shen, Y., Chapelle, F. H., Strom, E. W. & Benner, R. Origins and bioavailability of dissolved organic matter in groundwater. Biogeochemistry 122, 61–78 (2015).

Lapworth, D. J., Baran, N., Stuart, M. E. & Ward, R. S. Emerging organic contaminants in groundwater: A review of sources, fate and occurrence. Environ. Pollut. 163, 287–303 (2012).

Musgrove, M., Jurgens, B. C. & Opsahl, S. P. Karst groundwater vulnerability determined by modeled age and residence time tracers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL102853 (2023).

Grams, C. M., Binder, H., Pfahl, S., Piaget, N. & Wernli, H. Atmospheric processes triggering the central European floods in June 2013. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1691–1702 (2014).

Hari, V., Rakovec, O., Markonis, Y., Hanel, M. & Kumar, R. Increased future occurrences of the exceptional 2018–2019 Central European drought under global warming. Sci. Rep. 10, 12207 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Attachment, re-mobilization, and inactivation of bacteriophage MS2 during bank filtration following simulation of a high virus load and an extreme rain event. J. Contam. Hydrol. 246, 103960 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Dynamics of pathogens and fecal indicators during riverbank filtration in times of high and low river levels. Water Res. 209, 117961 (2022).

Rohwer, R. R. et al. Two decades of bacterial ecology and evolution in a freshwater lake. Nat. Microbiol. 10, 246–257 (2025).

Mehrshad, M. et al. Energy efficiency and biological interactions define the core microbiome of deep oligotrophic groundwater. Nat. Commun. 12, 4253 (2021).

Soares, A. et al. A global perspective on bacterial diversity in the terrestrial deep subsurface. Microbiology 169, 001172 (2023).

Herrmann, M. et al. Large fractions of CO2-fixing microorganisms in pristine limestone aquifers appear to be involved in the oxidation of reduced sulfur and nitrogen compounds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 2384–2394 (2015).

Taubert, M. et al. Bolstering fitness via CO2 fixation and organic carbon uptake: mixotrophs in modern groundwater. ISME J. 16, 1153–1162 (2022).

Moreira, D., Zivanovic, Y., López-Archilla, A. I., Iniesto, M. & López-García, P. Reductive evolution and unique predatory mode in the CPR bacterium Vampirococcus lugosii. Nat. Commun. 12, 2454 (2021).

Wang, J., Zhong, H., Chen, Q. & Ni, J. Adaption mechanism and ecological role of CPR bacteria in brackish-saline groundwater. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 10, 141 (2024).

Lehmann, K., Lehmann, R. & Totsche, K. U. Event-driven dynamics of the total mobile inventory in undisturbed soil account for significant fluxes of particulate organic carbon. Sci. Total Environ. 756, 143774 (2021).

Klindworth, A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e1–e1 (2013).

Kumar, S. et al. Thiosulfate- and hydrogen-driven autotrophic denitrification by a microbial consortium enriched from groundwater of an oligotrophic limestone aquifer. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94, fiy141 (2018).

Rughöft, S. et al. Community composition and abundance of bacterial, archaeal and nitrifying populations in savanna soils on contrasting bedrock material in Kruger National Park, South Africa. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1638 (2016).

Dittmar, T., Koch, B., Hertkorn, N. & Kattner, G. A simple and efficient method for the solid-phase extraction of dissolved organic matter (SPE-DOM) from seawater. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 6, 230–235 (2008).

Liu, Y., Lim, C. K., Shen, Z., Lee, P. K. H. & Nah, T. Effects of pH and light exposure on the survival of bacteria and their ability to biodegrade organic compounds in clouds: implications for microbial activity in acidic cloud water. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 1731–1747 (2023).

Antony, R. et al. Origin and sources of dissolved organic matter in snow on the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 6151–6159 (2014).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (R foundation for statistical Computing, 2022).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS ONE 8, e61217 (2013).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree: Computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1641–1650 (2009).

Edgar, R. C. High-accuracy alignment ensembles enable unbiased assessments of sequence homology and phylogeny. Nat. Commun. 13, 6968 (2022).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Yeh, Y.-C. & Fuhrman, J. A. Contrasting diversity patterns of prokaryotes and protists over time and depth at the San-Pedro Ocean Time series. ISME Commun. 2, 36 (2022).

Ferrera, I. et al. Seasonal and interannual variability of the free-living and particle-associated bacteria of a coastal microbiome. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 16, e13299 (2024).

Knights, D. et al. Bayesian community-wide culture-independent microbial source tracking. Nat. Methods 8, 761–763 (2011).

Ning, D. et al. A quantitative framework reveals ecological drivers of grassland microbial community assembly in response to warming. Nat. Commun. 11, 4717 (2020).

Herrmann, M. et al. Complex food webs coincide with high genetic potential for chemolithoautotrophy in fractured bedrock groundwater. Water Res. 170, 115306 (2020).

Lazar, C. S. et al. The endolithic bacterial diversity of shallow bedrock ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 679, 35–44 (2019).

Schwab, V. F. et al. Functional diversity of microbial communities in pristine aquifers inferred by PLFA-and sequencing-based approaches. Biogeosciences 14, 2697–2714 (2017).

Yurekten, O. et al. MetaboLights: open data repository for metabolomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D640–D646 (2024).

Acknowledgements