Abstract

The importance of sea-ice loss on the Arctic amplification of near-surface warming remains contentious, as Arctic amplification emerges even in model experiments with disabled surface-albedo feedback. Here we show that the characteristics and underlying dynamics of Arctic amplification may change greatly in a future ice-free climate using a series of climate model experiments. Our analysis indicates that although Arctic amplification continues over the 22nd century, it weakens markedly with a less distinct seasonality in a future ice-free climate. These changes are found to occur because the strength and seasonality of Arctic amplification in the current climate are attributed mainly to a tight coupling between cold-season lapse-rate feedback and sunlit-season surface-albedo feedback. The substantial differences in the characteristics of simulated Arctic amplification between the current and future ice-free climate therefore suggest that the presence of Arctic sea ice is an essential component of the current Arctic amplification regime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Observations indicate that near-surface warming resulting from increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases is greatly amplified in the Arctic in comparison to the global mean1,2,3,4,5,6. This phenomenon, termed as Arctic amplification (AA) or polar temperature amplification7,8,9,10,11, has substantial implications on Arctic ecosystems12, via potential methane release due to permafrost thawing, availability of new shipping routes associated with Arctic sea-ice shrinkage, and perturbed jet streams due to a reduced meridional surface temperature gradient11,13,14. It is also an important issue how the nature of AA affects cold winters over East Asia15. Although a majority of model simulations underestimate AA over the satellite era4,5,6 due in part to smaller internal climate variability than in observations over the tropics and/or the Arctic5,6,16, AA and its seasonality, characterized by a maximum during the cold season (October to February) and a minimum during summer (June to August), are qualitatively reproduced3,4,5,6,17,18. Given the marked contrast in the surface albedo between sea-ice-covered and open ocean areas, Arctic sea-ice loss and resulting increases in absorbed solar radiation by the Arctic Ocean have been suggested as a key process for AA3,11,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. However, it has been debated as to whether sea-ice loss and related surface-albedo feedback are necessary for inducing AA3,18,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35.

AA peaks in the cold season when the surface albedo feedback is mostly inactive due to the lack of incoming solar radiation. This mismatch in timing, along with the influence of winter air temperature on summer sea-ice extent36, might indicate that AA is driven by other factors such as longwave feedback processes (e.g., temperature (Planck plus lapse-rate), water vapour, and cloud feedbacks)7,30,37,38,39,40,41 and/or enhanced poleward energy transport from lower latitudes28,29,32,42 rather than sea-ice loss. In fact, lapse-rate feedback, which is associated with vertically non-uniform atmospheric warming, has been proposed as the primary contributor to AA30,39,41. The mechanism is that enhanced surface warming relative to that in the free troposphere leads to a positive lapse-rate feedback in the Arctic, whereas in the tropics/at lower latitudes, negative lapse-rate feedback acts to dampen the near-surface temperature response to external forcing30,41,43. Note that reanalyses show the Arctic lapse rate to have decreased significantly in all seasons except summer44. The mismatch in seasonality between AA and surface albedo feedback, however, has been attributed in large part to sea ice-related seasonal energy transfer. Due to enhanced summer ice melt, energy is taken up by the Arctic Ocean during summer (causing little AA in this season) and released primarily during autumn and winter contributing to AA during these seasons25,26,45.

Considering that AA occurs in simple aquaplanet configurations as well as in more realistic configurations but without surface albedo feedback28,29,32,46, sea-ice loss and related surface-albedo feedback may not be prerequisite for AA. However, some previous studies have suggested that longwave feedback processes and/or poleward energy transport might not be independent of sea-ice loss and related surface-albedo feedback3,18,25,26,46,47. For instance, results based on reanalysis data indicated that positive cold-season lapse-rate and cloud feedbacks strengthen over regions with large sea-ice retreat3. In agreement with this interconnected nature, the positive annual-mean lapse-rate feedback in the polar regions weakened in a model simulation when annual-mean surface-albedo feedback is disabled46; moreover, the sign of annual-mean lapse-rate feedback in the polar regions changed from positive to negative in response to a reduced ice albedo47. We also note that a reduced meridional surface temperature gradient due to AA results in a reduced poleward dry static energy transport18,43,48,49, although sub-Arctic warming and moistening may lead to an enhanced poleward moist heat transport in summer42,49,50.

The interconnectedness of lapse-rate and/or cloud feedbacks with Arctic sea-ice loss-related surface-albedo feedback makes it challenging to confidently determine the role of Arctic sea-ice loss in AA. In addition, due to the possibility that poleward energy transports could play a major role in AA42, it is unclear whether the strength and seasonality of AA may considerably change as the Arctic shifts to an ice-free mean state. In this study, we attempt to address these questions by analysing a series of coupled and targeted atmosphere-only time-slice climate-model simulations. Our analysis suggests that the characteristics and underlying dynamics of AA in the current climate may change greatly in a future ice-free climate because Arctic sea ice is an essential component of the current AA regime.

Results

Characteristics of Arctic amplification in the current climate

We begin by examining the characteristics of AA in the current climate using simulation output for the 50 ensemble members comprising the CESM2 LE SMBB subset51 (Methods). Figure 1a shows the monthly evolution of AA, defined here as the ratio of Arctic (70°N-90°N)-mean to global-mean surface air temperature change between 1951–1970 and 1991–2010 (Methods). Although there is a large inter-ensemble spread, implying the influence of internal variability, the simulated AA exhibits a distinct seasonality characterized by a maximum in late fall/early winter and a minimum in summer, which have been documented in previous studies4,25,26,45. Sea-ice loss-related surface-albedo feedback is expected to induce enhanced warming. However, the ratio is close to 1 during summer (June to August), indicating little AA. For the same period, we also computed the ratios using reconstructed and reanalysis data sets (Methods). Although the cold season (October-to-February) ratios computed from three reconstructed data sets are noticeably smaller than the median values of the CESM2 LE SMBB subset, the observations mostly fall within the range of the CESM2 LE. Moreover, the cold season ratios for all reconstructed datasets are smaller than those for the ERA5 reanalysis dataset, suggesting observational uncertainties (Supplementary Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the CESM2 LE and reconstructed/reanalysis datasets broadly agree on the seasonality of AA.

a Monthly evolution of AA, defined as the ratio of Arctic (70°N-90°N)-mean to global-mean surface air temperature (SAT) change between 1951–1970 and 1991–2010, in the CESM2 LE SMBB subset. The box covers the inter-quartile range with the line inside the box representing the median value across the 50 ensemble members and whiskers denoting the maximum and minimum values. Also presented are the ratios computed from HadCRUT5, GISTEMP v4, Berkeley Earth (high-resolution, beta version), and ERA5. b Spatial distribution of the ensemble-mean change in TOA downward longwave radiative flux related to lapse-rate feedback in November, with red contours denoting corresponding SAT changes (unit: K). Hatching denotes regions where less than 35 out of 50 ensemble members agree on the sign of change. c Similar to (b), but for the ensemble-mean stability over the period 1951–1970 estimated as the difference between the potential temperature at 850 hPa and 1000 hPa. d Same as in (b), but for the ensemble-mean changes in sea ice concentration. e Same as in (b), but for the ensemble-mean changes in surface turbulent heat fluxes.

Given that the median value of monthly AA peaks in November in the CESM2 LE SMBB subset (Fig. 1a), spatial distribution of the physical processes relevant to the amplified Arctic warming is examined focusing on November. Figure 1b indicates distinct increase in the ensemble-mean top-of-atmosphere (TOA) downward longwave radiative flux related to lapse-rate feedback, estimated using a radiative kernel method (Methods), over the Arctic Ocean and surrounding continents; the magnitude is however spatially non-uniform, with the largest values found over the regions with pronounced near-surface warming. A bottom-heavy warming, which induces positive cold-season lapse-rate feedback, may result from a suppressed vertical mixing caused by a very stable atmospheric condition52. To explore this possible causality, the strength of atmospheric stability is estimated by taking the difference between the potential temperature climatology at 850 hPa and 1000 hPa (i.e., Θ850 – Θ1000). Figure 1c indeed indicates that a stable condition is prevalent in the Arctic lower troposphere; however, there is a pronounced mismatch in spatial pattern between the stability and changes in both surface air temperature and lapse-rate feedback-related TOA downward longwave radiative flux. In contrast, changes in sea-ice concentration (Fig. 1d) and ocean-to-atmosphere turbulent heat flux (Fig. 1e) are more closely spatially linked to enhanced near-surface warming and strongly positive lapse-rate feedback over those regions, as discussed in previous studies3,43,45,53,54.

Although sea-ice retreat-related surface-albedo feedback is unlikely to exert a substantial influence on the Arctic TOA radiative budget during the cold season due to the lack of insolation, a large temperature difference between the warm ocean surface and the much colder overlying atmosphere implies that sea-ice retreat may play an important role via an ice insulation effect22,25,45,54. A comparison of the ensemble-mean sea-ice concentration changes with those for ocean-to-atmosphere turbulent heat flux, ocean-to-atmosphere water-vapour flux, and column-integrated cloud water path indicates a striking spatial correspondence (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d). A large amount of ocean-to-atmosphere turbulent heat and water-vapour fluxes in the sea-ice retreat regions contributes to amplified near-surface warming (Fig. 1b, d, e) and increased cloud optical thickness (Supplementary Fig. 2d, h, l, p), which may in turn act to delay the freezing of sea water through increased downward longwave radiative flux. The resulting near-surface warming amplification contributes to a bottom-heavy warming structure in the cold season3.

Interconnectedness of feedback processes in the Arctic

Previous studies indicated that a mismatch in the monthly evolution between Arctic-mean surface-albedo feedback and corresponding surface air temperature change arises from seasonal energy transfer. More specifically, a large fraction of increased downward shortwave radiative flux resulting from sea-ice loss is stored in the Arctic Ocean during the sunlit season (April to September) and then released to the atmosphere in subsequent fall and winter25,26,45. Given that while energy is used for melting in the sunlit season, refreezing of sea water involves ocean-to-atmosphere heat release in the cold season, the seasonal energy transfer also operates via sea ice changes. This suggests that the surface albedo feedback in the sunlit season is one of the key factors determining the strength of cold-season positive lapse-rate feedback3,43 via Arctic Ocean-mediated seasonal energy transfer45. This possible interconnection is further explored by analysing inter-ensemble relationships, using output from the CESM2 LE SMBB subset, among the following variables: Arctic-mean, seasonal-mean changes in downward shortwave radiative flux at the TOA associated with surface albedo feedback, net radiative plus turbulent heat flux at the surface, and downward longwave radiative flux at the TOA linked to lapse-rate feedback (A radiative kernel method is used to estimate TOA radiative flux changes associated, respectively, with surface-albedo feedback and lapse-rate feedback). Figure 2a shows that increased TOA downward shortwave radiative flux, averaged over the months from April to September, associated with sea-ice loss-related surface-albedo feedback contributes to corresponding increases in net downward flux at the surface (i.e., increased heat uptake by the ocean). As shown in Fig. 2b, the increases in heat uptake over the months from April to September are followed by increases in heat release from October to February, although r2 value is not high (~0.45); the increases in heat release, in turn, are accompanied by increases in TOA downward longwave radiative flux linked to lapse-rate feedback over the same season (Fig. 2c). Therefore, these results support the argument that the positive cold-season lapse-rate feedback is tightly connected to the sunlit-season surface-albedo feedback (Fig. 2d) via heat uptake/release and seasonal energy transfer in the Arctic Ocean3,43,45. Specifically, an increase of 1 W m−2 in the April-to-September surface-albedo feedback-related TOA downward radiative flux is related to an increase of 0.386 W m−2 in the October-to-February lapse-rate feedback-related TOA downward radiative flux. A rough estimation (Methods) further indicates that ~39 ± 10% of the October-to-February near-surface warming is due to the April-to-September surface-albedo feedback via the October-to-February lapse-rate feedback. We note, however, that cold-season longwave feedback processes, including the lapse-rate feedback, can enhance or pre-condition sea-ice retreat (Supplementary Fig. 3).

a Inter-ensemble relationship of the Arctic-mean sunlit season (April-to-September)-mean net downward flux change at the surface between 1951–1970 and 1991–2010 with the corresponding TOA downward shortwave radiative flux change related to surface albedo feedback. Each dot represents an ensemble member of the CESM2 LE SMBB subset. The regression slope and r2 values are presented in the upper-left corner. b Same as in (a), but for relationship between cold season (October-to-February)-mean net upward flux change at the surface and sunlit season-mean net downward flux change at the surface. c Same as in (a), but for relationship between cold season-mean lapse-rate feedback-related TOA downward longwave radiative flux change and cold season-mean net upward flux change at the surface. d Same as in (a), but for relationship between cold season-mean lapse-rate feedback-related TOA downward longwave radiative flux change and sunlit season-mean surface albedo feedback-related TOA downward shortwave radiative flux change. In (a–d), units are in W m−2. Note that in (a, c, d), TOA radiative flux changes are estimated using a radiative kernel method.

The connection of cold-season lapse-rate feedback with sea-ice loss is further examined by comparing vertical distributions of composite-mean atmospheric temperature change among land grid points, ocean grid points with sea-ice concentration decrease smaller than 15%, and ocean grid points with sea-ice concentration decrease greater than 15% (Supplementary Fig. 4). For summer months, in terms of both magnitude and vertical distribution, the temperature changes between 1951–1970 and 1991–2010 are very similar among the three cases: nearly uniform free tropospheric warming is contrasted with relatively weaker warming near the surface, resulting in an indistinct but negative lapse-rate feedback. The vertical distributions are also generally similar among the three cases for the cold season, characterized by a bottom-heavy warming structure. The magnitude of warming in the free troposphere appears to be largely insensitive to sea-ice loss. However, near-surface warming is greatly enhanced over regions with large sea-ice retreat, with a temperature increase of approximately 5 K in January, consistent with a reanalysis-based analysis in a previous study3. Although we chose the threshold of 15% following ref. 3, using a different threshold does not qualitatively affect our conclusion. This insensitivity may not be surprising, given that the sea ice boundary is traditionally taken at SIC = 15%55.

Decomposition of Arctic-mean near-surface warming and lapse-rate feedback-related radiative flux change

Climate model studies indicating that AA is simulated even with disabled surface albedo feedback28,29,32,46 imply that factors other than sea-ice loss may play a major role in AA. The interconnection between sea-ice loss and cold-season lapse-rate feedback documented in some previous studies3,43 and also presented in the previous subsection raises a question: can the magnitude and seasonality of AA in fully coupled model simulations be fully accounted for by local longwave feedback processes, such as lapse-rate feedback, and/or poleward energy transport from lower latitudes? As it is challenging to confidently determine the roles of these processes from coupled model simulation output, we analysed a series of CMIP6 atmosphere-only time-slice experiments56 along with corresponding fully coupled simulations, i.e., piControl and abrupt-4×CO2, for the CESM2 model (Methods).

In response to an abrupt quadrupling of atmospheric CO2 concentrations (i.e., abrupt-4×CO2 minus piControl), the coupled model simulations exhibit a pronounced seasonal contrast in Arctic-mean near-surface warming, characterized by a maximum during winter and a minimum during summer (Fig. 3a, black line). This distinct seasonality is well captured by the atmosphere-only time-slice experiments (i.e., a4SSTice-4×CO2 minus piSST; Fig. 3a, red line) designed to replicate the change from coupled model simulations. Having confirmed that atmosphere-only model simulations approximately reproduce the total changes, we attempt to decompose the total changes into the ice and non-ice source components (Methods). The non-ice source induces a seasonally non-uniform surface air temperature change with relatively large warming occurring from October to December (Fig. 3a, blue line), but fails to explain the marked seasonality, along with the substantially amplified cold-season warming, evident in the coupled model simulations. In contrast, the ice source component accounts for most of the prominent seasonality (Fig. 3a, dashed line in purple).

a Monthly evolution of Arctic (70°N-90°N)-mean SAT changes in the CESM2 coupled model simulation forced by abrupt CO2 quadrupling from a pre-industrial level (black line) and related atmosphere-only time-slice simulations with CAM6 (other lines). The solid line in red denotes the SAT changes arising from both the ice and non-ice sources in atmosphere-only model simulation in which the monthly varying SST and sea ice concentration changes were simultaneously prescribed along with a quadrupling of CO2 concentration (AMIP_Total). The solid line in blue and dashed line in purple, respectively, represent the non-ice and ice source components, estimated from atmosphere-only model simulations, with shading denoting uncertainty resulting from differences in the boundary conditions between piSST and a4SSTice. b Same as in (a), but for lapse-rate feedback-related changes in downward longwave radiative flux at the top of the atmosphere.

The impacts of both the ice and non-ice sources on Arctic lapse-rate feedback are also analysed using the coupled and atmosphere-only time-slice experiments. Arctic-mean changes in the TOA downward longwave radiative flux linked to lapse-rate feedback exhibit a distinct seasonality in the coupled simulations (i.e., abrupt-4×CO2 minus piControl; Fig. 3b, black line), which is approximately reproduced by atmosphere-only time-slice simulations (i.e., a4SSTice-4×CO2 minus piSST; Fig. 3b, red line). The non-ice source component also exhibits the slightly negative values during the summer season evident in both coupled (abrupt-4×CO2 minus piControl) and atmosphere-only (a4SSTice-4×CO2 minus piSST) simulations (Fig. 3b, blue line); however, it fails to replicate the large increases in TOA downward longwave radiative flux in the cold season. In comparison, the ice source component explains a large fraction (74-92%) of the increases in the cold season, albeit with positive, rather than negative, values in the summer season (Fig. 3b, dashed line in purple).

The influence of sea-ice loss on cold-season lapse-rate feedback is additionally explored by comparing the vertical structure of Arctic-mean temperature change between the coupled and atmosphere-only time-slice simulations (Supplementary Fig. 5). The vertical warming structures seen in the coupled model simulations forced by an abrupt CO2 quadrupling (black lines) are broadly reproduced by the atmosphere-only model simulations (i.e., a4SSTice-4×CO2 minus piSST, green lines). A comparison of these total changes with the temperature changes due to the non-ice (blue line) and ice sources (red lines) indicates that while the warming in the free troposphere is largely linked to the non-ice source, amplified near-surface warming in the cold season is distinctly related to sea-ice loss and associated SST warming in the Arctic. These results therefore suggest that sea-ice loss and related ocean-to-atmosphere heat transport are an important factor for driving bottom-heavy warming profile and thereby positive lapse-rate feedback in the cold season, supporting the argument of previous studies3,43.

Temporal evolution of Arctic amplification

The occurrence of AA in aquaplanet model simulations32 indicates that longwave feedback processes and/or poleward energy transport from lower latitudes play an important role in warming the Arctic. The suggested interconnection between sea-ice loss and cold-season lapse-rate feedback, the latter of which is proposed as the main contributor to AA30,41, however, implies that Arctic sea ice may be an important element of the current AA regime. We note that this hypothesis aligns with the suppressed seasonal contrast in the non-ice source-induced Arctic warming shown in Fig. 3a. These contrasting perspectives cause uncertainty as to whether the strength and seasonality of AA may change as the Arctic shifts to an ice-free climate. In this subsection, this question is addressed by analysing the 10-member CESM2 LE SMBB extended simulations57 (Methods).

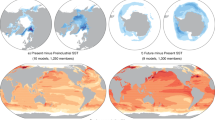

The ratio of the Arctic-mean to global-mean surface air temperature change between the first and last 20-year segments of given multiple 60-year periods is computed for each ensemble member over the period 1951–2290 (Supplementary Fig. 6 indicates that qualitatively similar results are obtained regardless of how to quantify the AA index). Although the temporal evolution is not linear (e.g., temporary increase in the AA index from 2031 to 2091, which appears to be related, in part, to cold-season sea-ice decrease and resulting heat release) and exhibits substantial inter-ensemble spread, the ratio of annual-mean temperature changes (i.e., the degree of AA) decreases from ~3 for the period 1951–2010 to ~1 for the period 2231–2290 (Fig. 4a). This overall weakening of AA over time, despite continuing global warming (Supplementary Fig. 7a), is accompanied by dramatic decreases in Arctic sea-ice extent to nearly ice-free conditions (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). In addition, the seasonality of AA is projected to undergo a considerable change over time. In the current climate, in terms of ensemble mean, amplified Arctic warming peaks in late fall/early winter, but becomes a minimum in summer (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 8a–c). Although this seasonal contrast exists throughout the 21st century, it virtually disappears in year-round ice-free conditions (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 8d-f). Meanwhile, Fig. 4b shows that the simulated Arctic-mean boreal summer warming is weaker than the corresponding global mean in the 23rd century. The related spatial distribution (Supplementary Fig. 8e) indicates that a suppressed warming in comparison to the global mean is observed over Greenland, while the ratio is greater than 1 over much of the Arctic Ocean.

a Ratio of the Arctic-mean annual-mean SAT change to global-mean annual-mean SAT change in the 10-member CESM2 LE extended simulations, with the x-axis representing the first year of various 60-year periods. The SAT changes are computed by subtracting the first 20-year average from the last 20-year average over a given 60-year period. The box covers the inter-quartile range with the line inside the box representing the median value across the ensemble members and whiskers denoting the maximum and minimum values. b Ensemble-mean ratio of the corresponding Arctic-mean monthly-mean SAT change to global-mean monthly-mean SAT change. In (b), the y-axis denotes month from January to December. Stippling denotes cases where the ensemble-mean ratio minus 1 is smaller than two standard deviations across the ensemble members. Regions with the ensemble-mean ratio smaller than 1 are also stippled. Note non-linear colour scales.

Temporal evolution of physical processes linked to Arctic amplification

To determine whether the dramatic changes in the characteristics of AA in nearly ice-free conditions are indeed linked to sea-ice evolution, the temporal evolution of the underlying physical processes is analysed (Fig. 5). Arctic-mean changes in TOA downward longwave radiative flux linked to lapse-rate feedback, normalized by corresponding global-mean near-surface warming, exhibit a distinct seasonality in the current climate, consistent with that for AA; however, the pronounced seasonal contrast, characterized by strongly positive values in the cold season and negative values in summer, disappears in future ice-free conditions (Fig. 5a). The seasonality in AA in the current climate and its disappearance in future ice-free conditions might be linked to changes in the characteristics of poleward energy transport. Considering that amplified warming over the Arctic leads to a decrease in poleward dry static energy transport18,43,48,49, we focus on poleward moisture transport, which can be estimated approximately as the Arctic-mean difference between precipitation and evaporation at the surface58. Although a large amount of moisture is transported to the Arctic in the current climate, enhanced transport in the early fall is inconsistent with the seasonality of AA (Fig. 5b vs. Fig. 4b). Unlike the lapse-rate feedback, poleward moisture transport does not seem to weaken in future ice-free conditions but is more pronounced in the cold season (Fig. 5b). This enhanced poleward moisture transport in future ice-free climates contributes to warming in the Arctic; however, the cold-season AA is much weaker in comparison to that in the current climate (Fig. 4b).

a Arctic-mean ensemble-mean lapse-rate feedback-related monthly-mean TOA downward longwave radiative flux changes normalized by corresponding global-mean SAT changes in the 10-member CESM2 LE extended simulations. Changes in radiative flux and temperature are computed by subtracting the first 20-year average from the last 20-year average over a given 60-year period. Stippling denotes regions where the magnitude of the ensemble mean is greater than two standard deviations across the ensemble members. b Same as in (a), but for poleward moisture transport changes across 70°N latitude circle normalized by the corresponding global-mean SAT changes. c Same as in (a), but for surface albedo feedback. d Same as in (a), but for Arctic-mean net downward flux changes at the surface normalized by corresponding global-mean SAT changes. In (a–d), the y-axis denotes month from January to December.

As the Arctic shifts to ice-free conditions over time (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d), the peak of ensemble-mean Arctic surface-albedo feedback is projected to shift from summer in the current climate to earlier months (i.e., spring) in the future along with considerable weakening of its strength after the first half of the 22nd century (Fig. 5c). These changes are expected to affect the characteristics of heat uptake/release at the ocean surface. A comparison of Arctic-mean changes in the net surface heat flux normalized by the corresponding global-mean warming with those in the surface albedo feedback indeed indicates that temporal evolution of the heat uptake in the sunlit season and heat release in the cold season is governed in large part by that of the surface albedo feedback (Fig. 5c, d).

The poleward ocean heat transport has a significant effect on the lapse-rate and the ice-albedo feedback59. Therefore, the projected changes in the strength and seasonality of AA over time might be linked more closely to changes in poleward oceanic heat transport. To examine this possibility, ensemble-mean Arctic Ocean-mean changes in subsurface potential temperature are compared among the following three periods: 1951–2010 (current climate), 2071–2130 (nearly ice-free summer condition), and 2211–2270 (nearly ice-free condition in all seasons). In the current climate, subsurface ocean warming is confined in the top 200 m layer (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Note that pronounced warming in the top 50 m layer occurring in the late summer/early fall, which is accompanied by the annual minima of near-surface atmospheric warming, is broadly concurrent with enhanced downward surface heat flux linked to sea-ice loss60. A qualitatively similar seasonality in the top 50 m layer warming is found over the period 2071–2130 (Supplementary Fig. 9b); however, in this case, large year-round warming below 200 m depth accompanies the changes in the surface layer. The simulated year-round warming in the Arctic Ocean mid-depth appears to be related to the influx of the warmed Atlantic water61. In contrast to a similar year-round warming below 200 m depth to that over the period 2071–2130, the warming in the top 50 m layer considerably weakens for the period 2211–2270 when the Arctic is nearly sea-ice free in all seasons (Supplementary Fig. 9c). Hence, it is unlikely that the projected changes in the strength and seasonality of AA can be attributed mainly to changes in poleward oceanic heat transport. Nonetheless, given large inter-model spread in the projection of poleward heat transport, further study is needed to confirm this conclusion.

Summary and discussion

Despite the fact that AA is one of the most robust features of both observed and model-simulated climate change, the Arctic regions exhibit large inter-model spread in near-surface warming resulting from imposed external forcing25,45, suggesting uncertainties in the underlying mechanisms3,11,18,26,28,29,30,32,33,35,41. In particular, the importance of Arctic sea-ice loss and associated surface-albedo feedback in AA has been debated in spite of their substantial influence on the Arctic TOA radiation budget. This is because AA emerges in climate model experiments with disabled surface-albedo feedback28,29,32, which implies a major role of longwave feedback processes and/or poleward energy transport from lower latitudes. Indeed, previous studies have shown that opposing signs of the lapse-rate feedback between the Arctic and the tropics are the key factor driving AA30,39,41. However, the distinctly positive cold-season lapse-rate feedback in the Arctic is unlikely to be independent of sea-ice loss and related surface-albedo feedback during the sunlit-season3,18,25,26,31,32,33,34,35,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47, complicating the picture.

To enhance the understanding of the physical processes responsible for AA with a particular focus on the role of sea-ice loss, we have analysed a series of coupled and targeted atmosphere-only time-slice climate-model simulations. In agreement with previous studies3,25,26,43,45, we found that a bottom-heavy warming structure and resulting positive lapse-rate feedback in the cold season are closely linked to sea-ice loss-related ocean heat uptake in the sunlit-season and subsequent heat release in the cold season. In particular, analyses of the atmosphere-only time-slice experiments, which were designed to replicate the corresponding coupled model simulations, indicate that the strength and seasonality of AA may greatly weaken in the absence of Arctic sea-ice loss. In line with this interconnected nature, a subset of the CESM2 LE experiment members covering the time period from current to future year-round ice-free conditions indicates that the prominent seasonality evident in the current climate, characterized by a maximum in the cold season and a minimum in summer, disappears in an ice-free climate with marked weakening of both annual- and cold season-mean AA, supporting previous studies26,45.

Although our analysis demonstrates the importance of Arctic sea-ice loss and related surface-albedo feedback, it does not mean that other processes play a minor role in AA. In line with the presence of AA in climate model simulations with disabled surface-albedo feedback28,29,32, the CESM2 LE extended simulations indicate that in nearly ice-free future climate, greenhouse gas forcing-induced warming is still greater over the Arctic in comparison to the global average (Fig. 4), suggesting longwave feedback processes and/or poleward energy transport as drivers. In addition, a previous study showed that AA develops rapidly in response to imposed abrupt CO2 quadrupling before Arctic sea ice responds to the forcing62. The model-projected disappearance of seasonality, along with marked weakening of AA, however, suggests that Arctic sea ice is an indispensable component of the current AA regime.

Methods

CESM2 Large Ensemble

AA and underlying physical processes are examined by analysing output from the Community Earth System Model version 2 Large Ensemble (CESM2 LE) simulations forced by the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 6 (CMIP6)63 historical protocol over the period 1850–2014 and Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) forcing scenario SSP3-7.0, the strongest forcing scenario after SSP5-8.5, over the period 2015–210051. The CESM2 LE consists of two 50-member subsets: while the ensemble members in the first subset were forced by the CMIP6 biomass burning emissions, those in the second subset were integrated with a smoothed version of the biomass burning dataset over the period 1990–2020 (hereafter referred to as the SMBB subset)51. Note that except for biomass burning emissions, the same external forcing was applied to the 100 ensemble members with different initial conditions. Ref. 51 provides detailed information on the CESM2 LE initialization procedure.

For 10 ensemble members of the CESM2 LE SMBB subset, the future climate change projections under the SSP3-7.0 forcing scenario were extended beyond the year 2100 (until 2500) with a reduction of fossil and industrial CO2 emissions to zero by 2250 (ref. 57). Temporal evolution of the simulated global-mean, annual-mean surface air temperature indicates a continued global warming over the period 1850–2300 in response to imposed greenhouse gas forcing (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Interestingly, despite the decrease in atmospheric CO2 concentration after 2250, the simulated global warming appears to persist. The Arctic region (70°N-90°N) also exhibits a distinct surface warming until ~2300, but the warming nearly saturates in the post-2300 period (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Along with this prominent surface warming, the Arctic is projected to undergo a rapid September sea-ice decrease during the first half of the 21st century and become nearly ice-free afterwards (Supplementary Fig. 7d). In March, when the climatological-mean Arctic sea-ice extent exhibits its maximum in the current climate, it is projected to decrease more slowly, but the Arctic will be completely ice free also in this month in the second half of the 22nd century in the CESM2 LE extended simulations (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Hence, these multi-realization extended simulations covering a future ice-free climate state provide an excellent opportunity to robustly explore the role of sea-ice retreat and related surface-albedo feedback in AA. In this study, we used output from the 50-member SMBB subset to analyse the characteristics of AA in the current climate, and output from the 10-member extended simulations to explore the evolution of AA as the Arctic shifts to an ice-free climate. Considering decreasing CO2 concentrations and nearly constant Arctic-mean surface air temperature after 2300, the post-2300 period is excluded from our analysis.

Measure of Arctic amplification

In this study, we quantify AA by computing the ratio of Arctic (70°N-90°N)-mean surface air temperature change between given two 20-year periods to the corresponding global-mean change. The magnitude of AA varies depending on how the Arctic is defined4; however, using a different Arctic boundary does not qualitatively affect our conclusion. To assess whether the CESM2 LE reasonably simulates AA and its seasonality, we also computed the ratios using reconstructed and reanalysis data sets: HadCRUT5.0.2.064, GISTEMP v465,66, Berkeley Earth (high-resolution beta version, https://berkeleyearth.org/high-resolution-data-access-page/), and ERA567.

Due to decadal climate variability, the temporal evolution of AA might vary when the AA index is quantified in a different way. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, however, qualitatively consistent temporal evolution is obtained regardless of how to determine the AA index.

CMIP6 time-slice experiments

Previous studies showed that AA simulated from coupled models integrated with imposed greenhouse gas forcing is linked, in large part, to opposing signs in the lapse-rate feedback between the Arctic and the tropics17,30,41,52. The positive lapse-rate feedback over the Arctic, however, may not be independent of sea-ice loss and related surface-albedo feedback3,43,46,47. As this possible interconnection has a profound implication for AA in an ice-free climate, a set of CMIP6 atmosphere-only time-slice experiments56 (conducted with CAM6, with fixed SSTs and sea ice from CESM2) is analysed in conjunction with relevant coupled simulations forced by an abrupt quadrupling of CO2 concentrations (conducted with CESM2). The CMIP6 Cloud Feedback Model Intercomparison Project56 designed these atmosphere-only time-slice experiments to replicate the corresponding piControl and abrupt-4×CO2 simulations. We used the following 30-year atmosphere-only time-slice experiments to decompose the changes in top-of-atmosphere (TOA) longwave radiative flux associated with lapse-rate feedback in coupled model simulations into flux changes due to (1) non-ice source and (2) ice source: piSST, piSST-4×CO2, a4SST, a4SSTice, and a4SSTice-4×CO2. In piSST, monthly and annually varying SSTs and sea ice along with atmospheric constituents are taken from a 30-year subsection of the corresponding piControl simulation, with the time period corresponding to the years 111–140 of abrupt-4×CO2 experiment. The piSST-4×CO2 is identical to piSST, but with a quadrupling of CO2. The a4SST experiment is identical to piSST, except that monthly and annually varying non-polar region SSTs are taken from the years 111–140 of the corresponding abrupt-4×CO2. The a4SSTice is also identical to piSST, but in this experiment both SSTs and sea ice are taken from abrupt-4×CO2. The a4SSTice-4×CO2 is the same as a4SSTice, but with CO2 concentrations being quadrupled. The relationship between the coupled and atmosphere-only time slice simulations is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 10.

The total change in TOA longwave radiative flux resulting from both the non-ice and ice sources is computed by subtracting piSST from a4SSTice-4×CO2. Regarding the non-ice component, assuming additivity, we used piSST, a4SST, piSST-4×CO2, a4SSTice, and a4SSTice-4×CO2: (a4SST – piSST) + (piSST-4×CO2 – piSST)/2 + (a4SSTice-4×CO2 – a4SSTice)/2, in which the first term represents the extra-Arctic SST contribution whereas the second and third term the CO2 contribution. Given differences in the boundary conditions between piSST and a4SSTice, the non-ice component is also estimated by adding (piSST-4×CO2 – piSST) or (a4SSTice-4×CO2 – a4SSTice) to (a4SST – piSST). Then, the ice-component is estimated by subtracting the non-ice component from the total change. We note that the results might vary depending on climate models due to inter-model discrepancy in future Arctic changes as well as the lapse-rate and surface-albedo feedbacks68.

Radiative kernel method

To estimate the changes in TOA radiative flux associated with temperature (i.e., Planck plus lapse-rate) feedback and surface albedo feedback, we employed a technique using radiative kernels, which are produced by computing the change in TOA radiative flux R caused by a small perturbation of a given climate variable x in a radiative transfer model with all other variables fixed (i.e., \(\partial R/\partial x\))69,70,71. For example, the change in TOA radiative flux due to temperature feedback can be estimated at each grid point by multiplying temperature kernel (\({K}_{T}=\partial R/\partial T\)) at a given pressure level with the corresponding temperature change \(\Delta T\) and then by vertically integrating the product (i.e., \({K}_{T}\times \Delta T\)) from the surface to the tropopause. The change in TOA radiative flux associated with the Planck feedback is estimated in the same way, except for assuming vertically uniform warming equal to change in surface air temperature. The difference in the TOA radiative flux change between the temperature and Planck feedbacks represents change in TOA radiative flux linked to lapse-rate feedback. In case of the change in TOA radiative flux due to surface albedo feedback, the radiative kernel for surface albedo (\({K}_{\alpha }=\partial R/\partial \alpha\)) is multiplied by change in surface albedo \((\Delta \alpha )\). In this study, we used radiative kernels constructed by ref. 72.

A change in Arctic-mean surface air temperature (ΔSAT) resulting from the Arctic-mean change in TOA radiative flux related to a given feedback process (ΔR) can be roughly estimated by dividing the Arctic-mean TOA radiative flux change by Arctic-mean Planck feedback (λPL) (i.e., \(\Delta {SAT}\approx -\frac{\Delta R}{{\lambda }_{{PL}}}\))30,41. Using this approach, we crudely estimate to what extent the sunlit-season surface-albedo feedback may contribute to cold-season near-surface warming via lapse-rate feedback in Fig. 2d. First, the Arctic-mean October-to-February-mean TOA downward longwave flux change related to Arctic-mean April-to-September-mean TOA downward shortwave flux change is estimated for each ensemble member by multiplying April-to-September-mean shortwave flux change by the regression slope presented in the top left corner. Next, the resultant Arctic-mean October-to-February-mean surface air temperature change is roughly estimated by dividing the computed longwave flux change by –λPL. Then, the ratio of the estimated to the simulated Arctic-mean October-to-February-mean surface air temperature change is computed for each ensemble member. Finally, the ensemble mean and associated inter-ensemble standard deviation are computed for the ratio.

Data availability

The CESM2 Large Ensemble output is available at https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/projects/community-projects/LENS2/data-sets.html, the CMIP6 coupled and atmosphere-only time-slice simulation output at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/, the HadCRUT5.0.2.0 data set at https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadcrut5/, GISTEMPv4 at https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/, the Berkeley Earth High-resolution data set (beta version) at https://berkeleyearth.org/high-resolution-data-access-page/, and the ERA5 data set at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu. The CESM2 LE extension simulation data will be available on the IBS Center for Climate Physics (ICCP) Climate Data website. The data for replicating the main figures in this study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17096013.

Code availability

Figures are generated using the NCAR Command Language (NCL, Version 6.6.2, https://doi.org/10.5065/D6WD3XH5). The codes used to generate the main figures in this study are freely available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17096013.

References

Serreze, M. C. & Francis, J. A. The Arctic amplification debate. Climatic Change 76, 241–264 (2006).

Graversen, R. G., Mauritsen, T., Tjernström, M., Källén, E. & Svensson, G. Vertical structure of recent Arctic warming. Nature 451, 53–56 (2008).

Jenkins, M. T. & Dai, A. Arctic climate feedbacks in ERA5 reanalysis: Seasonal and spatial variations and the impact of sea-ice loss. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099263 (2022).

Rantanen, M. et al. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 168 (2022).

Chylek, P. et al. Annual mean Arctic amplification 1970-2020: Observed and simulated by CMIP6 climate models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099371 (2022).

Sweeney, A. J., Fu, Q., Po-Chedley, S., Wang, H. & Wang, M. Internal variability increased Arctic amplification during 1980–2022. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL106060 (2023).

Manabe, S. & Wetherald, R. T. The effects of doubling the CO2 concentration on the climate of a general circulation model. J. Atmos. Sci. 32, 3–15 (1975).

Hansen, J. et al. Efficacy of climate forcings. J. Geophys. Res. 110, D18104 (2005).

Holland, M. M. & Bitz, C. M. Polar amplification of climate change in coupled models. Clim. Dyn. 21, 221–232 (2003).

Screen, J. A., Bracegirdle, T. J. & Simmonds, I. Polar climate change as manifest in atmospheric circulation. Curr. Clim. Change Reps. 4, 383–395 (2018).

Smith, D. M. et al. The Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP) contribution to CMIP6: Investigating the causes and consequences of polar amplification. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1139–1164 (2019).

Post, E. et al. Ecological consequences of sea-ice decline. Science 341, 519–524 (2013).

Smith, D. M. et al. Robust but weak winter atmospheric circulation response to future Arctic sea ice loss. Nat. Commun. 13, 727 (2022).

Luo, D. et al. Arctic amplification-induced intensification of planetary wave modulational instability: A simplified theory of enhanced large-scale waviness. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 150, 2888–2905 (2024).

Zhuo, W., Yao, Y., Luo, D., Simmonds, I. & Huang, F. The key atmospheric drivers linking regional Arctic amplification with East Asian cold extremes. Atmos. Res. 283, 106557 (2023).

Jahfer, S., Ha, K.-J., Chung, E.-S., Franzke, C. L. E. & Sharma, S. Unveiling the role of tropical Pacific on the emergence of ice-free Arctic projections. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 044033 (2024).

Goosse, H. et al. Quantifying climate feedbacks in polar regions. Nat. Commun. 9, 1919 (2018).

Previdi, M., Smith, K. L. & Polvani, L. M. Arctic amplification of climate change: a review of underlying mechanisms. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 093003 (2021).

Hall, A. The role of surface albedo feedback in climate. J. Clim. 17, 1550–1568 (2004).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. Increasing fall-winter energy loss from the Arctic Ocean and its role in Arctic temperature amplification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L16707 (2010).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. The central role of diminishing sea ice in recent Arctic temperature amplification. Nature 464, 1334–1337 (2010).

Deser, C., Tomas, R., Alexander, M. & Lawrence, D. The seasonal atmospheric response to projected Arctic sea ice loss in the late twenty-first century. J. Clim. 23, 333–351 (2010).

Crook, J. A., Forster, P. M. & Stuber, N. Spatial patterns of modeled climate feedback and contributions to temperature response and polar amplification. J. Clim. 24, 3575–3592 (2011).

Screen, J. A., Deser, C. & Simmonds, I. Local and remote controls on observed Arctic warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L10709 (2012).

Boeke, R. C. & Taylor, P. C. Seasonal energy exchange in sea ice retreat regions contributes to differences in projected Arctic warming. Nat. Commun. 9, 5017 (2018).

Dai, A., Luo, D., Song, M. & Liu, J. Arctic amplification is caused by sea-ice loss under increasing CO2. Nat. Commun. 10, 121 (2019).

Liang, Y.-C., Polvani, L. M. & Mitevski, I. Arctic amplification, and its seasonal migration, over a wide range of abrupt CO2 forcing. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 14 (2022).

Alexeev, V. A., Langen, P. L. & Bates, J. R. Polar amplification of surface warming on an aquaplanet in “ghost forcing” experiments without sea ice feedbacks. Clim. Dyn. 24, 655–666 (2005).

Graversen, R. G. & Wang, M. Polar amplification in a coupled climate model with locked albedo. Clim. Dyn. 33, 629–643 (2009).

Pithan, F. & Mauritsen, T. Arctic amplification dominated by temperature feedbacks in contemporary climate models. Nat. Geosci. 7, 181–184 (2014).

Laîné, A., Yoshimori, M. & Abe-Ouchi, A. Surface Arctic amplification factors in CMIP5 models: Land and oceanic surfaces and seasonality. J. Clim. 29, 3297–3316 (2016).

Russotto, R. D. & Biasutti, M. Polar amplification as an inherent response of a circulating atmosphere: Results from the TRACMIP aquaplanets. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086771 (2020).

Henderson, G. R. et al. Local and remote atmospheric circulation drivers of Arctic change: A review. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 709896 (2021).

Taylor, P. C. et al. A decomposition of feedback contributions to polar warming amplification. J. Clim. 26, 7023–7043 (2013).

Taylor, P. C. et al. Process drivers, inter-model spread, and the path forward: A review of amplified Arctic warming. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 758361 (2022).

Docquier, D. et al. Drivers of summer Arctic sea-ice extent at interannual time scale in CMIP6 large ensembles revealed by information flow. Sci. Rep. 14, 24236 (2024).

Vavrus, S. The impact of cloud feedbacks on Arctic climate under greenhouse forcing. J. Clim. 17, 603–615 (2004).

Winton, M. Amplified Arctic climate change: What does surface albedo feedback have to do with it?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L03701 (2006).

Payne, A. E., Jansen, M. F. & Cronin, T. W. Conceptual model analysis of the influence of temperature feedbacks on polar amplification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 9561–9570 (2015).

Lee, S., Gong, T., Feldstein, S. B., Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. Revisiting the cause of the 1989-2009 Arctic surface warming using the surface energy budget: Downward infrared radiation dominates the surface fluxes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 10,654–10,661 (2017).

Stuecker, M. F. et al. Polar amplification dominated by local forcing and feedbacks. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 1076–1081 (2018).

Hahn, L. C., Armour, K. C., Battisti, D. S., Donohoe, A. & Fajber, R. Seasonal changes in atmospheric heat transport to the Arctic under increased CO2. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105156 (2023).

Feldl, N., Po-Chedley, S., Singh, H. K. A., Hay, S. & Kushner, P. J. Sea ice and atmospheric circulation shape the high-latitude lapse rate feedback. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 3, 41 (2020).

Simmonds, I. & Li, M. Trends and variability in polar sea ice, global atmospheric circulations and baroclinicity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1504, 167–186 (2021).

Chung, E.-S. et al. Cold-season Arctic amplification driven by Arctic Ocean-mediated seasonal energy transfer. Earths Future 9, e2020EF001898 (2021).

Graversen, R. G., Langen, P. L. & Mauritsen, T. Polar amplification in CCSM4: Contributions from the lapse rate and surface albedo feedbacks. J. Clim. 27, 4433–4450 (2014).

Feldl, N., Bordoni, S. & Merlis, T. M. Coupled high-latitude climate feedbacks and their impact on atmospheric heat transport. J. Clim. 30, 189–201 (2017).

Hwang, Y. T., Frierson, D. M. W. & Kay, J. E. Coupling between Arctic feedbacks and changes in poleward energy transport. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L17704 (2011).

Graversen, R. G. & Langen, P. L. On the role of the atmospheric energy transport in 2×CO2-induced polar amplification in CESM1. J. Clim 32, 3941–3956 (2019).

Fajber, R., Donohoe, A., Ragen, S., Armour, K. C. & Kushner, P. J. Atmospheric heat transport is governed by meridional gradients in surface evaporation in modern-day earth-like climates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2217202120 (2023).

Rodgers, K. B. et al. Ubiquity of human-induced changes in climate variability. Earth. Syst. Dyn. 12, 1393–1411 (2021).

Bintanja, R., Graversen, R. G. & Hazeleger, W. Arctic winter warming amplified by the thermal inversion and consequent low infrared cooling to space. Nat. Geosci. 4, 758–761 (2011).

Boeke, R. C., Taylor, P. C. & Sejas, S. A. On the nature of the Arctic’s positive lapse-rate feedback. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091109 (2021).

Jenkins, M. & Dai, A. The impact of sea-ice loss on Arctic climate feedbacks and their role for Arctic amplification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094599 (2021).

Simmonds, I. Comparing and contrasting the behaviour of Arctic and Antarctic sea ice over the 35-year period 1979-2013. Ann. Glaciol. 56, 18–28 (2015).

Webb, M. J. et al. The Cloud Feedback Model Intercomparison Project (CFMIP) contribution to CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 359–384 (2017).

Lee, S.-S. et al. Multi-centennial climate change in a warming world beyond 2100. Earth. Syst. Dyn. 16, 1427–1451 (2025).

Bintanja, R. & Selten, F. M. Future increases in Arctic precipitation linked to local evaporation and sea-ice retreat. Nature 509, 479–482 (2014).

Eiselt, K.-U. & Graversen, R. G. On the control of Northern Hemispheric feedbacks by AMOC: Evidence from CMIP and slab ocean modeling. J. Clim. 36, 6777–6795 (2023).

Han, J.-S., Park, H.-S. & Chung, E.-S. Projections of central Arctic summer sea surface temperatures in CMIP6. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 124047 (2023).

Khosravi, N. et al. The Arctic Ocean in CMIP6 models: Biases and projected changes in temperature and salinity. Earth’s Future 10, e2021EF002282 (2022).

Previdi, M., Janoski, T. P., Chiodo, G., Smith, K. L. & Polvani, L. M. Arctic amplification: A rapid response to radiative forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089933 (2020).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Morice, C. P. et al. An updated assessment of near-surface temperature change from 1850: the HadCRUT5 data set. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2019JD032361 (2021).

GISTEMP Team. GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP), version 4. NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Dataset accessed 2024-12-24 at https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/ (2024)

Lenssen, N. et al. A NASA GISTEMPv4 observational uncertainty ensemble. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2023JD040179 (2024).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Eiselt, K.-U. & Graversen, R. G. Change in climate sensitivity and its dependence on the lapse-rate feedback in 4×CO2 climate model experiments. J. Clim. 35, 2919–2932 (2022).

Soden, B. J. & Held, I. M. An assessment of climate feedbacks in coupled ocean-atmosphere models. J. Clim. 19, 3354–3360 (2006).

Soden, B. J. et al. Quantifying climate feedbacks using radiative kernels. J. Clim. 21, 3504–3520 (2008).

Shell, K. M., Kiehl, J. T. & Shields, C. A. Using the radiative kernel technique to calculate climate feedbacks in NCAR’s Community Atmosphere Model. J. Clim. 21, 2269–2282 (2008).

Pendergrass, A. G., Conley, A. & Vitt, F. M. Surface and top-of-atmosphere radiative feedback kernels for CESM-CAM5. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 317–324 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank three anonymous reviewers and the editor for their constructive and valuable comments, which led to an improved version of the manuscript. We acknowledge the CESM2 Large Ensemble Community Project and supercomputing resources provided by the IBS Center for Climate Physics. We are also grateful to National Center for Atmospheric Research for providing CMIP6 simulation output. E.-S.C., S.-J.K., J.-H.K., and S.-Y.J. were supported by Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI) grant funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (KOPRI PE25010). K.-J.H. and S.-S.L. were supported by the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) under IBS-R028-D1. K.-J.H. was also supported by the Global—Learning & Academic Research Institution for Master’s, PhD students, and Postdocs (LAMP) Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (No. RS-2023-00301938). M.F.S. was supported by the National Science Foundation award AGS-2141728. This is IPRC publication 1646 and SOEST contribution 12006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.-S.C. and S.-J.K. designed the study. E-S.C. performed the analysis and produced figures. S.-J.K., K.-J.H., M.F.S., S.-S.L., J.-H.K., S.-Y.J., and T.B. provided feedback on the analyses, interpretation of the results, and the figures. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and the improvement of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Rune Graversen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, ES., Kim, SJ., Ha, KJ. et al. The role of sea ice in present and future Arctic amplification. Commun Earth Environ 6, 910 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02834-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02834-9