Abstract

Montane forests are biodiversity hotspots that provide important ecosystem services, including temperature buffering for numerous species underneath forest canopies. In recent decades, montane forests have been under increasing pressure from small-and large-scale deforestation, yet associated spatio-temporal changes in temperature buffering capacity remain unclear. Here, we studied the changes in temperature buffering capacity due to forest loss from 2003 to 2022 in three montane forest ecosystems in Africa (Mount Kilimanjaro, Mount Bale, and the Taita Hills). We modeled the temperature buffering changes based on in situ microclimate measurements inside forests and in open areas, climate data, airborne laser scanning data, and satellite observations. We found that during the study period montane forests were lost at a rate of 2–9% across the study areas. This loss led to an annual average microclimate air temperature warming ranging from 2.0 ± 0.8 °C to 5.6 ± 2.1 °C across the three montane forests. The warming reduced the maximum air temperature buffering by an average of 3 ± 1.5 °C. Locally, the temperature buffering disappeared over time and transitioned to a mesoclimate amplification. Our findings demonstrate that microclimate buffering capacity was markedly diminished as a result of microclimate warming driven by recent forest loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropical montane forests are biodiversity hotspots that provide crucial ecosystem services, including temperature buffering and refugia for numerous species1,2. Forest canopies are important drivers of microclimate temperature buffering3 through mechanisms such as shading from direct solar radiation as well as reduced evapotranspiration and vertical mixing of air, leading to lower maximum temperatures and higher minimum temperatures compared to open habitats1,4,5,6. Other drivers, such as topography, soil, water balance, proximity to water bodies, and prevailing meteorological conditions, also have an important impact on temperature buffering1,4. These mechanisms regulate temperature fluctuations inside forest canopies; consequently, forest dwelling organisms experience microclimatic conditions that differ substantially from the macroclimate of open habitats1,2,6,7,8. The microclimate buffering capacity of forest canopies is, hence, critical for the survival of plant and animal species in montane forests2,9. Nonetheless, montane forests are threatened by deforestation, logging, fires, and climate extremes, putting their buffering capacity of montane forests and biodiversity at risk10,11. However, so far it is unknown how different scales of forest loss affect the microclimate buffering capacity of montane forests.

African montane forests have experienced among the highest rates of deforestation globally (0.48% per year) in recent decades12. Deforestation patterns across Africa are characterized by both small- and large-scale clearings13,14, with small-scale cropland expansion being the dominant (64%) driver of deforestation in Africa compared with large-scale commodity agriculture13,14. While small-scale tree loss can be expected to decrease the buffering capacity of montane forests15, large-scale clearings can lead to a total loss of buffering, where the temperature difference between the microclimate air temperature and macroclimate air temperature disappears4. As deforestation intensifies and more open spaces are created, microclimate air temperature near the ground may be amplified16 and exceed the macroclimate air temperature because of high radiation loads17, which may not be fully compensated by transpiration as tree cover is cleared.

In order to explore the impact of deforestation on macroclimate warming, previous studies have primarily relied on standard weather stations18,19, which are located in an open area outside forests and do not represent microclimate air temperature changes. Consequently, in situ microclimate measurements and global networks of such scarce measurements are needed3,20. Recent studies, based on in situ microclimate measurements, have investigated the buffering capacity of forest canopies compared to open habitats1,21 as well as the sensitivity of tropical forest microclimates to climate change21. Comparing the temperature difference between inside forest and adjacent open habitat using a paired comparison of in situ sensors in a space-for-time substitution approach (i.e., changes in space are assumed to be equivalent to changes in time as long as the paired sites share similar topographic and climatic conditions) can provide information on the potential or hypothetical impact of deforestation on temperature buffering in the lowlands. However, such an approach does not show the actual impact of deforestation and is less suitable in montane forests with high topographic and climatic gradients. Furthermore, compared to more extensively studied forest systems, such as tropical lowland forests and urban forests, there is a dearth of studies on microclimate buffering in montane forests. Consequently, information on the actual impacts of deforestation on temperature buffering is lacking, and it is unclear where and whether the buffering capacity of montane forests was reduced, completely lost, or shifted from buffering to macro or meso climate amplification.

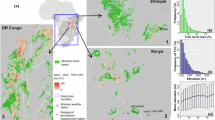

Here, we evaluated the actual impact of forest loss on the buffering capacity (i.e., an offset of micro- and mesoclimates) of montane forests (elevation 1200–3500 m a.s.l., see “Methods” for detailed definition) in Africa over the last two decades (2003–2022). Specifically, we estimated the magnitude of microclimate buffering change due to human-induced forest loss from the maximum air temperature offset between microclimate air temperature (Tmicro) at 15 cm above the ground and the Tmeso (refers in this manuscript to the gridded mesoclimate air temperature interpolated from weather stations at 1 km spatial resolution19) (Tmicro − Tmeso, hereafter Toffset), and mapped areas that experienced microclimate buffering decrease (i.e., Toffset was smaller after forest loss than before but Tmicro is still less than Tmeso by at least 1 °C), loss (Tmicro and Tmeso have similar magnitude), or mesoclimate amplification (Tmicro is greater than Tmeso by at least 1 °C). Moreover, we evaluated the sensitivity of Toffset to changes in canopy cover and height induced by forest loss from 2003 to 2022. Our analyses were conducted in three forested landscapes in the Eastern Afromontane Biodiversity Hotspot22,23 (Mount Bale in Ethiopia, Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, and the Taita Hills in Kenya) (Fig. 1). These study areas were considered as they represent different scales of forest loss (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Panel (a) Mount Bale (Ethiopia), (b) Mount Kilimanjaro (Tanzania), and (c) the Taita Hills (Kenya). The canopy height model in the background is for 2022 and was generated using a machine learning approach (see “Methods”). The canopy height is masked by the montane forest extent of a–c from a previous study19. Yellow polygons indicate protected areas from the World Database on Protected Areas56. The polygons in blue show the airborne laser scanning footprints in 2022 and 2015 for the Taita Hills and Mount Kilimanjaro, respectively.

We followed a data-driven approach to model Toffset, induced by forest loss, based on observations from in situ microclimate stations, mesoclimate data, airborne laser scanning, and Landsat Analysis Ready Data (ARD) (Methods). Deforestation from 2003 to 2022 was identified using Landsat timeseries24,25,26. To model Tmicro, input forest structure variables (canopy cover and height) were first predicted based on a machine learning approach using predictors from the Landsat ARD27. Reference forest structure data, for model training and validation, were obtained from airborne laser scanning acquisition in the study areas. The predicted forest structure data together with Tmeso, topographic data, and in situ microclimate measurements were then used to develop a generalized linear mixed Tmicro model. The change in Toffset, attributed to deforestation from 2003 to 2022, was finally estimated by removing the effect of the background climate variability signal18,19 with the aim to clarify the impact of recent forest loss on the buffering capacity of montane forests in Africa.

Results

Dominant reduction in microclimate buffering due to forest loss

From 2003 to 2022, forest loss evaluated at a spatial resolution of 30 m × 30 m was more widespread in Mount Bale than in Mount Kilimanjaro and the Taita Hills (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The classification accuracy of forest loss was relatively higher in Mount Bale (88% F1 score) than in Mount Kilimanjaro (77% F1 score) and the Taita Hills (78% F1 score). Montane forests, decreased by 9% in Mount Bale (92831 ± 11823 ha at 95% confidence interval (CI)), 4% (742 ± 177 ha at 95% CI) in the Taita Hills, and 2% (2838 ± 1354 ha at 95% CI) in Mount Kilimanjaro (Supplementary Table 2).

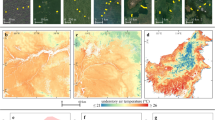

The overall impact of the forest loss on microclimate buffering was assessed by comparing the average Toffset of the pre- and post-forest loss condition for the three montane forests separately (Fig. 2). The average Toffset refers to the average Toffset of all areas affected by forest loss per montane region. The microclimate buffering capacity of areas that experienced forest loss in Mount Bale decreased on average by 2.3 ± 1.0 °C (i.e., from −3.6 ± 1.5 °C in 2003 before forest loss to −1.3 ± 1.7 °C in 2022 after forest loss) (Fig. 2a). In Mount Kilimanjaro and the Taita Hills, in areas affected by tree loss, microclimate buffering declined by 4.5 ± 2.3 °C (i.e., from −4.4 ± 2.6 °C in 2003 to 0.1 ± 1.9 °C in 2022) and 2.8 ± 1.3 °C (i.e., from −5.5 ± 1.9 °C in 2003 to −2.7 ± 1.6 °C in 2022), respectively (Fig. 2b, c). An example of a closer view of a map showing the spatial pattern of Toffset for the pre- and post-forest loss condition is provided in Supplementary Fig. 2a, and its location is indicated in a black box in Fig. 3.

Panels (a–c) show the probability density graphs of the temperature offset (Toffset) between microclimate (Tmicro) and mesoclimate (Tmeso) (i.e., Toffset = Tmicro – Tmeso) in 2003 (before forest loss) and 2022 (after forest loss) and the changes in Toffset caused by forest loss between the two years (ΔToffset = Toffset(2022) – Toffset(2003)) in Mount Bale (Ethiopia), Mount Kilimanjaro (Tanzania), and the Taita Hills (Kenya) respectively.

Panel (a) Mount Bale (Ethiopia), (b) Mount Kilimanjaro (Tanzania), and (c) the Taita Hills (Kenya). The background map with blue gradients shows the maximum air temperature offset between microclimate (Tmicro) and mesoclimate (Tmeso) for the montane forest extent in 2022 (Toffset = Tmicro – Tmeso). The purple, yellow, and black colors indicate three classes of microclimate buffering change: a decrease in microclimate buffering due to forest loss (still Tmicro < Tmeso by at least 1 °C), a loss of microclimate buffering (Tmicro ≈ Tmeso), and an amplification of mesoclimate (Tmicro > Tmeso by at least 1 °C), respectively. The magnitude of the change in Toffset from 2003 to 2022 (∆Toffset = Toffset (2022) – Toffset (2003)) for the three classes is provided in a probability density graph in each plot. The pie charts show the percentage of microclimate buffering change for the three classes. The black box in (a) shows the location for the close-up view in Supplementary Fig. 2a.

Depending on the intensity of forest loss across a 30 m × 30 m spatial grid and the comparison of Tmicro and Tmeso after forest loss, a detailed investigation of the shift in microclimate buffering caused by forest loss revealed three spatial patterns of Toffset change across the three montane forests, i.e., reduction, Tmicro is still < Tmeso by at least 1 °C; loss, Tmicro ≈ Tmeso; and amplification, Tmicro > Tmeso by at least 1 °C after forest loss.

In all three montane forests, reduction in microclimate buffering due to forest loss was more dominant than microclimate buffering loss and mesoclimate amplification (Fig. 3a–c). In Mount Bale, 55% of the total areas affected by forest loss experienced microclimate buffering reduction (Tmicro increased by 2.0 ± 0.8 °C), 36% microclimate buffering loss (Tmicro increased by 2.5 ± 1.0 °C), and the remaining 9% exhibited amplification (Tmicro increased by 3.9 ± 1.1 °C) (Fig. 3a). In the Taita Hills, 86% experienced a reduction in microclimate buffering (Tmicro increased by 2.7 ± 1.3 °C), 13% a loss (Tmicro increased by 3.1 ± 1.6 °C), and 1% an amplification (Tmicro increased by 3.8 ± 0.7 °C) (Fig. 3c). Mount Kilimanjaro showed relatively proportional changes in microclimate buffering, with areas that experienced microclimate buffering reduction accounting for 40% (Tmicro increased by 4.3 ± 1.9 °C), loss 28% (Tmicro increased by 4.3 ± 2.5 °C), and amplification 32% (Tmicro increased by 5.6 ± 2.1 °C) (Fig. 3b).

Differential sensitivity of microclimate buffering change to canopy cover loss among montane forests

The impact of changes in forest structure, induced by forest loss, on the magnitude of microclimate buffering shifts is presented in Fig. 4a–c. The impacts of canopy cover loss on microclimate buffering change varied across the three montane forests. Based on generalized additive modeling, canopy cover change explained 21% (P < 0.001) of the microclimate buffering change in Mount Bale, 45% (P < 0.001) in Mount Kilimanjaro, and 41% (P < 0.001) in the Taita Hills, respectively.

Panel (a–c) show the sensitivity of the change in maximum air temperature offset between microclimate air temperature (Tmicro) and mesoclimate air temperature (Tmeso) (Toffset = Tmicro – Tmeso; ΔToffset = Toffset(2022) – Toffset(2003)) to canopy cover loss from 2003 to 2022 in Mount Bale (Ethiopia), Mount Kilimanjaro (Tanzania), and the Taita Hills (Kenya) respectively. A cubic spline regression is fitted (red lines) with a 95% confidence interval (blue shading) based on generalized additive modeling.

Discussion

This study provides evidence on the impact of forest loss on microclimate buffering from 2003 to 2022 in three montane forests (Mount Kilimanjaro, Mount Bale, and the Taita Hills) in the Eastern Afromontane Biodiversity Hotspot. Our results show that, in areas affected by forest loss, microclimate buffering declined across the study area. Our study suggests that controlling small-scale forest loss, especially in areas affected by deforestation, is important not only because of its impact on reducing the microclimate buffering capacity of forests but also because of its potential to grow into large-scale forest loss through cropland and grazing land expansion (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). In particular, large-scale forest loss should be avoided as it causes the total loss of microclimate buffering and can lead to further microclimate warming that exceeds the mesoclimate temperature through amplification, which is detrimental to biodiversity9,28 both in the source area of forest loss and in nearby stable forests through the edge effect29.

Our study showed an average microclimate buffering capacity reduction of 2.3–4.5 °C across three montane forests due to actual forest loss. These values are within the range of previous maximum temperature offsets based on in situ measurements in tropical forests, which are mostly inferred from paired comparisons of stable forest and adjacent open habitat or disturbed forest in a space-for-time substitution approach1,15. Evidence shows that smaller changes in forest structure from selective logging can reduce the buffering capacity of tropical forests by up to 1.5 °C15. Another study has contested this notion by reporting a thermally buffered tropical forest despite logging30. Compared to selective logging, where the dominant land use remains the same, deforestation, which induces land use transformation from forest to cropland or open grassland, is expected to have a greater impact on microclimate buffering due to considerable changes in forest structure. Particularly in areas of intense forest loss, higher microclimate warming is expected as we have demonstrated in areas that have lost their buffering capacity (i.e., up to ~4 °C warming) and have transformed to mesoclimate amplification (i.e., up to ~6 °C warming on average).

Our mesoclimate amplification result in open habitats following intense forest loss (i.e., higher Tmicro than Tmeso) is supported by in situ measurements of microclimate and standardized weather stations in our study area (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), as well as in previous studies17,21. In open habitats, Tmicro is often higher than Tmeso during the daytime and vice versa at nighttime (Supplementary Fig. 4). Such an amplification effect is likely related to the high radiation load and less air mixing from reduced windspeed caused by friction near the ground, which is not compensated by evaporative cooling because of loss of tree cover from forest loss17. Associated with the amplification, the temperature increase and dryness together result in an increasing risk of fire even inside the wet montane forests of Mount Kilimanjaro31. In addition, our results showed a differential sensitivity of microclimate buffering change to canopy cover loss among the three study areas. Such differences can be related to variations in geographic location, topography (e.g., elevation, slope, and aspect), and forest structure32,33. For example, after partial loss of forest cover, the vertical crown density of the remaining forest patches can vary among montane forests. This, in turn, affects how much light reaches the understory, thereby causing variations in microclimate buffering change15,33,34.

In summary, compared with previous studies, our results offer additional insights into microclimate buffering changes induced by forest loss in three ways. First, we provide the buffering change based on actual forest loss rather than hypothetical forest disturbance inferred by comparing stable forest with adjacent open habitat or disturbed forest. Second, we provide details on how different intensities of forest loss affect microclimate buffering through identifying areas that: (1) are still buffering but with reduced capacity because of small-scale forest loss, (2) have completely lost their buffering capacity, and (3) have transformed into mesoclimate amplification because of intense forest loss. Finally, unlike previous studies, which have either mostly focused on lowland forests or have mixed results for montane forests with those for lowlands, we provide results on microclimate buffering reductions exclusively for montane forests that are part of the Eastern Afromontane Biodiversity Hotspot.

Implications

The response of microclimate buffering to different forest loss intensities has important implications for the survival and distribution of species. Following a reduction in microclimate buffering capacity, animal and plant species could respond differently depending on their thermal tolerance and adaptive capacity. Some could shift their distribution vertically along the elevation gradient or horizontally toward colder areas in the nearby stable forests. For example, some understory plant species can shift their distributions toward more thermophilic species35. Other species may adapt to the increased microclimate temperature and remain there without shifting their range of occurrence28. In the worst case, (endemic) species may be unable to shift their distributions or adapt to changing environmental conditions, ultimately placing them on a trajectory toward extinction36.

When microclimate buffering is completely lost and transformed into amplification because of intense forest loss, the anomalous microclimate warming may even reach a critical thermal maximum and some animal species can lose their locomotory ability (e.g., some Pristimantis frogs) to escape the novel thermal conditions, leading to their death and gradual extinction9. In particular, as the microclimate warming (~2–6 °C on average) induced by forest loss surpasses the critical thermal maximum threshold (~2 °C) reported in previous studies for some tropical forest amphibian and reptile species9,28, its impact on biodiversity loss can be critical10,37.

Previous studies in tropical forests reported that the effects of forest loss are not limited to the actual site of forest loss but also extend 20 m into adjacent stable forests through edge effects29. Hence, the impact from the reduction in microclimate buffering likely extends into the forest interior29. As climate change has been shown to induce further warming in intact tropical forests38, the microclimate buffering capacity of stable forests may be further reduced by the combined impacts of climate change and edge effects induced by forest loss.

In areas where microclimate buffering capacity is threatened, conservation and restoration efforts are urgently needed. Various microclimate management strategies can be implemented to restore the lost microclimate and maintain biodiversity and ecosystem services. In areas where the microclimate buffering capacity has been reduced by small-scale forest loss, the implementation of forest conservation strategies, for example through preventing further loss of forest and allowing the forest to regenerate naturally, can rapidly restore the microclimate30,39. In contrast, in areas that have lost microclimate buffering capacity due to intense forest loss, a reforestation strategy may be important to restore the lost microclimate. In addition, as a proactive measure, it is very important to identify and protect intact forests that serve as micro-refuge from deforestation, as well as conserving taller trees with multi-layered crowns because of their greater impact on microclimate15,32,33. This requires the implementation of a robust conservation strategy that includes: (1) legal protection of forests; (2) the empowerment of indigenous groups through, for example, awareness raising on the impacts of forest loss on microclimate and biodiversity; and (3) implementing a continuous cover forestry to preserve a continuous canopy and forest floor, thereby reducing extreme temperature and moisture fluctuations to decrease impacts on forest microclimate.

Limitations and uncertainty

Our analysis has limitations and uncertainties related to data, methodology, and scale of the study. The number of microclimate stations is too small to implement machine learning approaches, which can have better power and flexibility in terms of scaling the microclimate modeling over a larger region in the tropics than employing generalized additive mixed models. Furthermore, the lack of longer in situ microclimate timeseries that spans the study period (2003 to 2022) limits further improvement of the Tmicro model as well as accurate evaluation of the temporal transferability of the Tmicro model. In this regard, it is very important to extend the global network of microclimate monitoring stations in montane biodiversity hotspots. Initiatives, such as the Kili-project with networks of climate stations in remote forest areas of Mount Kilimanjaro40, and the Microclimate Ecology & Biogeography network (MEB), formerly known as SoilTemp20, which provides a platform for storing and sharing microclimate timeseries and biodiversity data, holds great potential to fill this gap in the future.

Based on an independent test conducted on a new site in Kenya (Supplementary Fig. 8), the accuracy limitations of our microclimate model (root-mean-square error of 1.5 °C) do not allow reliable detection of Toffset changes below 1.5 °C. Hence, caution should be made in applying this method to monitor smaller Toffset changes induced, for example, by selective logging15. Nevertheless, in our study, the average Toffset changes (i.e., 2.0–4.5 °C) are larger than the error margin. In order to robustly evaluate the uncertainty of the microclimate model, data from multiple sites, including Mount Bale and Mount Kilimanjaro, is needed in the future.

When interpreting the results, the spatial resolution of our study (30 m × 30 m) should be taken in to account. At smaller scales (<30 m), higher microclimate warming and buffering offset can be expected, but at larger scales where the microclimate can be studied (~100 m)17, the effects can be smaller than reported in our study, except in areas with extensive clearings. Furthermore, our study captures the local impacts of forest loss on microclimate buffering but the non-local impacts through changes in precipitation and cloud cover, which can have different magnitude on opposing sides of a mountain, were not captured in our analysis. However, previous studies in tropics have shown that forest loss reduces precipitation and cloud cover41,42. Hence, the non-local effect is likely to amplify the impacts of forest loss on microclimate buffering but with differences in the magnitude of its impact on the windward and leeward side of a mountain.

Methods

Study areas

This study was conducted in three biodiverse montane forests in Africa: Mount Bale in Ethiopia, Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, and the Taita Hills in Kenya (Fig. 1). The extent of the montane forests was extracted from the African montane forest distribution map, which was prepared based on tree cover (≥ 30%), elevation (1200–3500 m a.s.l.), and local elevation range (>300 m)19. The three montane forests were selected for two reasons. First, they all belong to the Eastern Afromontane Biodiversity Hotspot22,23, which is characterized by high species diversity and endemism. Mount Bale contains the most extensive remaining natural forest in Ethiopia and the largest contiguous montane Erica (e.g., Erica trimera and Erica arborea) belts in Africa43. Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest mountain in Africa, comprises around 3000 species of vascular plants, including the tallest trees in Africa44,45,46. The Taita Hills contain 1530 vascular plant species46,47 and the last remaining primary montane forest47. Second, these three montane forests together represent different: (a) intensities of tree loss (i.e., ranging from small- to large-scale clearings) (Supplementary Table 1), (b) causes of tree loss (i.e., deforestation47,48 for small-scale agriculture or grazing, forest loss due to fire, logging for timber and fuelwood extraction in Mount Bale) (Supplementary Fig. 2b) and the Taita Hills, and regulated tree harvesting in plantation forestry in Mount Kilimanjaro), and (c) elevation gradient (1200–3500 m a.s.l.) (i.e., lower to upper montane forest) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Forest loss detection in the three montane forests in Africa

Forest loss locations from 2003 to 2022 for the three montane forests were identified using a combined approach based on the Global Forest Change (GFC) product and a spectral mixture model applied to the Normalized Difference Fraction Index (NDFI) from the Landsat Collection 2 time series surface reflectance product as in our previous study19,26. Because the GFC product records forest cover gains only until 2012, the combined approach that uses NDFI trend from 2003 to 2022 was applied to filter and remove pixels that underwent forest cover gains during this period19. This approach helps to identify forest loss pixels that have not recovered their tree covers from 2003 to 2022. Sample-based accuracy and area uncertainty at 95% CI were assessed against reference high- resolution imagery from Google, following recommended practice in the literature49, for the three montane forests separately. Accuracy was evaluated using omission error, commission error, and F1 score (Supplementary Table 2).

Canopy height and cover modeling and validation

We modeled canopy height (CH) for the years 2003 and 2022 using a machine learning approach that combined predictor variables from Landsat ARD at 30 m × 30 m spatial resolution and reference CH data from airborne laser scanning. These CH estimates served as input to microclimate modeling (see next section). The ARD were provided by the Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) team (GLAD ARD), which provides spatially and temporally consistent normalized Landsat surface reflectance data for change detection27. This step was necessary because no available CH products were available covering the study areas for the target years (2003 and 2022). Initially, a total of 21 GLAD ARD predictors including median composite of surface reflectance in the visible, near-infrared, and shortwave-infrared spectrum, vegetation indices, and phenology metrics were used as predictor variables (Supplementary Table 3). The 2022 CH model derived from airborne laser scanning26 over the Taita Hills (Kenya) was used as reference data. The reference CH model was binned at 5 m intervals (i.e., 0–5 m, 5–10 m, …, 40–45 m, and 45–50 m) to generate a total of 8997 stratified random samples (i.e., 1000 random samples from each bin except the last two bins, which have a lower number of samples). Variable selection was done based on the predictive performance of variables at new spatial locations using spatial forward feature selection and spatial cross-validation50 (Supplementary Table 3). To do this, “CreateSpacetimeFolds” and “ffs” functions and random forest (RF) model were used from the “CAST” (the ‘caret’ Applications for Spatial-Temporal Models) R package. The spatial cross-validation (CV), unlike random k-fold CV, considers the location of and distance between the training and validation data points. In the validation process, it avoids using subsets of data point locations already used for model training. This is done by training the model repeatedly through leaving the data from one spatial fold (i.e., a group of data points located close to each) or location out and utilizing the held back data for model validation, thereby reducing model over-fitting issues arising from spatial-autocorrelation. Furthermore, the spatial forward feature selection process identifies and removes predictors that cause over-fitting based on their spatial CV performance50. We used 70% of the reference sample data for model training and internal cross-validation and the remaining 30% for external validation. The RF regression was performed using 500 decision trees and five samples per nodes. A summary of the model performance is provided in Supplementary Table 4.

To evaluate the spatio-temporal transferability of the model (i.e., if the model can be used reliably in another location and time period), independent validation of the CH prediction was tested using the 2014 reference CH model from airborne laser scanning over Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania (Supplementary Fig. 5a) and the 2022 CH model from Mbololo (independent of the training areas) in the Taita Hills, Kenya (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Furthermore, the accuracy of the CH model was compared with global CH products, which showed better performance (R2 improved by 6–22%), using reference CH from airborne laser scanning (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c). A similar machine learning approach was used to model canopy cover using several predictors (e.g., surface reflectance and vegetation indices) from Landsat ARD. The selected predictors and model performance are presented in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6.

Microclimate air temperature modeling and validation

Tmicro modeling at 30 m spatial resolution was done by applying environmental variables and a generalized additive mixture (GAM) model (Eq. 1) using the “gamm” function from the “mgcv” R package. In situ Tmicro data measured at 15 cm above the ground from TMS4 loggers in the Taita Hills51 were used as a response variable to build the model (see Supplementary Fig. 7 for the distribution of the sensors). To avoid over heating by the sun, the TMS4 loggers were shielded with a white plastic reflector. A total of 148 monthly average maximum Tmicro measurements (from 37 TMS4 loggers) between April 2021 and March 2022 were used. Initially, candidate environmental predictors that can strongly affect Tmicro were identified from literature4,52 and tested in the GAM model, with TMS4 logger sensor ID used as a random effect term to account for the non-independence of data from the same site (Eq. 1). These are the monthly average maximum Tmeso, forest structure (canopy cover and height), and topography (elevation, slope, aspect, and topographic position index), which were all standardized to a common scale (i.e., 0–1). In decreasing order of influence in the model, the best-performing model (lowest Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion) was obtained using CH, Tmeso, topographic position index (TPI), aspect (A), and elevation (E) as linear terms (Supplementary Table 7).

The CH described in the previous section was used as the CH data source for the GAM model. Tmeso data over montane forests in Africa at 1 km resolution, which have a good accuracy against in situ measurements (RMSE = 0.82–0.97; R2 = 0.89–0.96), were obtained from our previous study19. These Tmeso data were prepared using a RF ensemble learning approach based on in situ weather stations (up to 498 stations) and predictors (land surface temperature, normalized difference vegetation index, albedo, latitude, and longitude) from Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) onboard Terra and Aqua satellites. The choice of these Tmeso data over other available products (e.g., ERA5-Land with ~9 km spatial resolution) was because of their relatively higher spatial resolution (1 km) and better accuracy in montane forests in Africa when tested against in situ measurements19. The Tmeso data were resampled to 30 m using bilinear interpolation to match the spatial resolution with the other variables (i.e., CH, topographic position index, aspect, and elevation). The remaining variables (i.e., topographic position index, aspect, and elevation) were extracted from the NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission 30 m digital elevation model53. The sensitivity of the GAM microclimate model to CH model uncertainty was tested by running the model using CH data from airborne laser scanning in the Taita Hills (Kenya), which showed minor changes (i.e., R2 changed by only ~2%).

We assumed that the spatio-temporal transferability of the CH model, its stronger influence on Tmicro model, and the wide canopy height ranges (5–45 m; Fig. 1), would support the extendibility of the Tmicro model derived from the Taita Hills to other montane forests in nearby region, including Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Bale. To demonstrate this, the accuracy of the GAM microclimate model was independently tested (RMSE = 1.5) using Tmicro data from in situ TMS4 sensors from another indigenous closed canopy forest site in the Kasigau montane forest in Kenya, located 40 km southeast of the Taita Hills (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Estimating microclimate buffering change induced by forest loss

Microclimate buffering is defined in this study as the air temperature offset (Toffset) between Tmicro and Tmeso (Eqs. 2 and 3). The change in Toffset (ΔToffset) (from 2003 to 2022) consists of a combined signal from forest cover change (ΔToffset(fcc)) and the background climate change signal (ΔToffset(cc)). Hence, ΔToffset(fcc) was calculated by subtracting the ΔToffset(cc) from the total ΔToffset using a similar approach as in previous studies18,19 (Eqs. 4–6). In this approach, the ΔToffset(cc) was calculated from the ΔToffset in nearby stable forests located within 5 km of the forest loss pixels. Only stable pixels (i.e., pixels with no tree loss or gain recorded from 2003 to 2022 within the elevation range of the forest loss pixels were considered by identifying the elevation range within the forest loss pixels and excluding the reference stable pixels outside this range. Furthermore, an inverse distance weighting was used to minimize the influence of the distance of the stable forest pixels on the ΔToffset(cc) estimation18,19.

A simplified flow chart that shows the overall methodology is provided in Supplementary Fig. 9. In this study, we used R version 4.2.2 for data analysis and QGIS version 3.30.2 for map composition.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data used for the analysis are available online and from the authors at the below address. Landsat Analysis Ready Data (ARD) from the Global Land Analysis & Discovery (GLAD) laboratory in the Department of Geographical Sciences at the University of Maryland at https://glad.umd.edu/; Global Forest Change data from https://glad.earthengine.app/view/global-forest-change; NASA SRTM DEM at 30 m spatial resolution from https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/NASA_NASADEM_HGT_001; and mesoclimate air temperature data at 1 km resolution from https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1278988554. Microclimate air temperature measurements from TMS4 loggers (eduardo.maeda@helsinki.fi, janne.heiskanen@helsinki.fi, petri.pellikka@helsinki.fi, and temesgen.abera@geo.uni-marburg.de) as well as forest structure data from airborne laser scanning in Taita Hills (janne.heiskanen@helsinki.fi) and Kilimanjaro (woellaus@staff.uni-marburg.de) are available up on reasonable request from the authors. The data that supports the findings of this study are stored in an open-access repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1725871755.

Code availability

All relevant R functions used in this study are referred to in the Methods section. R codes used for data analysis are available up on request.

References

De Frenne, P. et al. Global buffering of temperatures under forest canopies. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 744–749 (2019).

Lenoir, J., Hattab, T. & Pierre, G. Climatic microrefugia under anthropogenic climate change: implications for species redistribution. Ecography 40, 253–266 (2017).

Kemppinen, J. et al. Microclimate, an important part of ecology and biogeography. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 33, e13834 (2024).

De Frenne, P. et al. Forest microclimates and climate change: Importance, drivers and future research agenda. Glob. Chang. Biol. 27, 2279–2297 (2021).

Potter, K. A., Arthur Woods, H. & Pincebourde, S. Microclimatic challenges in global change biology. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 2932–2939 (2013).

Aalto, I. J., Maeda, E. E., Heiskanen, J., Aalto, E. K. & Pellikka, P. K. E. Strong influence of trees outside forest in regulating microclimate of intensively modified Afromontane landscapes. Biogeosciences 19, 4227–4247 (2022).

Davis, K. T., Dobrowski, S. Z., Holden, Z. A., Higuera, P. E. & Abatzoglou, J. T. Microclimatic buffering in forests of the future: the role of local water balance. Ecography 42, 1–11 (2019).

Bramer, I. et al. Advances in monitoring and modelling climate at ecologically relevant scales. Adv. Ecol. Res. 58, 101–161 (2018).

González-del-Pliego, P. et al. Thermal tolerance and the importance of microhabitats for Andean frogs in the context of land use and climate change. J. Anim. Ecol. 89, 2451–2460 (2020).

Newbold, T. et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 520, 45–50 (2015).

Alroy, J. Effects of habitat disturbance on tropical forest biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 114, 6056–6061 (2017).

He, X. et al. Accelerating global mountain forest loss threatens biodiversity hotspots. One Earth 6, 303–315 (2023).

Masolele, R. N. et al. Mapping the diversity of land uses following deforestation across Africa. Sci. Rep. 14, 1681 (2024).

Curtis, P. G., Slay, C. M., Harris, N. L., Tyukavina, A. & Hansen, M. C. Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Science 361, 1108–1111 (2018).

Santos, E. G. et al. Structural changes caused by selective logging undermine the thermal buffering capacity of tropical forests. Agric. For. Meteorol. 348, 109912 (2024).

Gril, E. et al. Using airborne LiDAR to map forest microclimate temperature buffering or amplification. Remote Sens. Environ. 298, 113820 (2023).

Geiger, R., Aron, R. H. & Todhunter, P. The Climate Near the Ground (Rowman & Littlefield, 2003).

Alkama, R. & Cescatti, A. Biophysical climate impacts of recent changes in global forest cover. Science 351, 600–604 (2016).

Abera, T. A. et al. Deforestation amplifies climate change effects on warming and cloud level rise in African montane forests. Nat. Commun. 15, 6992 (2024).

Lembrechts, J. J. et al. SoilTemp: a global database of near-surface temperature. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 6616–6629 (2020).

Gril, E. et al. Slope and equilibrium: a parsimonious and flexible approach to model microclimate. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 885–897 (2023).

Mittermeier, R. A. et al. Hotspots Revisited: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Ecoregions (CEMEX, 2004).

Mairal, M. et al. Geographic barriers and Pleistocene climate change shaped patterns of genetic variation in the Eastern Afromontane biodiversity hotspot. Sci. Rep. 7, 45749 (2017).

Hansen, M. C. et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 342, 850–853 (2013).

Souza, C. M., Roberts, D. A. & Cochrane, M. A. Combining spectral and spatial information to map canopy damage from selective logging and forest fires. Remote Sens. Environ. 98, 329–343 (2005).

Abera, T., Pellikka, P., Johansson, T., Mwamodenyi, J. & Heiskanen, J. Towards tree-based systems disturbance monitoring of tropical mosaic landscape using a time series ensemble learning approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 299, 113876 (2023).

Potapov, P. et al. Landsat analysis ready data for global land cover and land cover change mapping. Remote Sens. 12, 426 (2020).

Frishkoff, L. O., Hadly, E. A. & Daily, G. C. Thermal niche predicts tolerance to habitat conversion in tropical amphibians and reptiles. Glob. Chang. Biol. 21, 3901–3916 (2015).

Ewers, R. M. & Banks-Leite, C. Fragmentation impairs the microclimate buffering effect of tropical forests. PLoS ONE 8, e58093 (2013).

Senior, R. A., Hill, J. K., Benedick, S. & Edwards, D. P. Tropical forests are thermally buffered despite intensive selective logging. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 1267–1278 (2018).

Hemp, A. The impact of fire on diversity, structure, and composition of the vegetation on Mt. Kilimanjaro. in Land Use Change and Mountain Biodiversity (eds. Spehn, E., Körner, C. & Liberman, M.) 51–68 (CRC Press, 2006).

Terschanski, J. et al. The role of vegetation structural diversity in regulating the microclimate of human-modified tropical ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 360, 121128 (2024).

Jucker, T. et al. Canopy structure and topography jointly constrain the microclimate of human-modified tropical landscapes. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 5243–5258 (2018).

Starck, I. et al. Slow recovery of microclimate temperature buffering capacity after clear-cuts in boreal forests. Agric. For. Meteorol. 363, 110434 (2025).

Stevens, J. T., Safford, H. D., Harrison, S. & Latimer, A. M. Forest disturbance accelerates thermophilization of understory plant communities. J. Ecol. 103, 1253–1263 (2015).

Hollenbeck, E. C. & Sax, D. F. Experimental evidence of climate change extinction risk in Neotropical montane epiphytes. Nat Commun 15, 6045 (2024).

Nogués-Bravo, D., Rodríguez, J., Hortal, J., Batra, P. & Araújo, M. B. Climate change, humans, and the extinction of the woolly mammoth. PLoS Biol 6, e79 (2008).

Trew, B. T. et al. Novel temperatures are already widespread beneath the world’s tropical forest canopies. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 753–759 (2024).

Mollinari, M. M., Peres, C. A. & Edwards, D. P. Rapid recovery of thermal environment after selective logging in the Amazon. Agric. For. Meteorol. 278, 107637 (2019).

Hemp, A. & Hemp, J. Weather or not—global climate databases: Reliable on tropical mountains?. PLoS ONE 19, e0299363 (2024).

Smith, C., Baker, J. C. A. & Spracklen, D. V. Tropical deforestation causes large reductions in observed precipitation. Nature 615, 270–275 (2023).

Hua, W., Zhou, L., Dai, A., Chen, H. & Liu, Y. Important non-local effects of deforestation on cloud cover changes in CMIP6 models. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 094047 (2023).

Miehe, S. & Miehe, G. Ericaceous Forests and Heathlands in the Bale Mountains of South Ethiopia: Ecology and Man’s Impact, 206p (Warnke, 1994).

Hemp, A. et al. Africa’s highest mountain harbours Africa’s tallest trees. Biodivers. Conserv. 26, 103–113 (2017).

Hemp, A. Vegetation of Kilimanjaro: hidden endemics and missing bamboo. Afr. J. Ecol. 44, 305–328 (2006).

Watuma, B. M. et al. An annotated checklist of the vascular plants of Taita Hills, Eastern Arc Mountain. PK 191, 1–158 (2022).

Pellikka, P. K. E. et al. Agricultural expansion and its consequences in the Taita Hills, Kenya. in Earth Surf. Process Vol. 16, 165–179 (Elsevier, 2013).

Teucher, M. et al. Behind the fog: Forest degradation despite logging bans in an East African cloud forest. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 22, e01024 (2020).

Olofsson, P. et al. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote Sens. Environ. 148, 42–57 (2014).

Meyer, H., Reudenbach, C., Hengl, T., Katurji, M. & Nauss, T. Improving performance of spatio-temporal machine learning models using forward feature selection and target-oriented validation. Environ. Model. Softw. 101, 1–9 (2018).

Abera, T., Heiskanen, J., Maeda, E., Odongo, V. & Pellikka, P. Impacts of land cover and management change on top-of-canopy and below-canopy temperatures in Southeastern Kenya. Sci. Total Environ. 874, 162560 (2023).

Maclean, I. M. D. et al. On the measurement of microclimate. Methods Ecol. Evol. 12, 1397–1410 (2021).

Farr, T. G. et al. The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev. Geophys. 45, 2005RG000183 (2007).

Abera, T. A. Data to support ‘Deforestation amplifies climate change effects on warming and cloud level rise in African montane forest’ (Version 1) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12789885 (2024).

Abera, T. A. Data to Support the Manuscript ‘Deforestation Reduces Microclimate Buffering of African Montane Forests’ (Version 1) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17258717 (2025).

UNEP-WCMC and IUCN (2025). Protected Planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), May 2025, Cambridge, UK: UNEP-WCMC and IUCN. Available at: www.protectedplanet.net.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by postdoctoral funding from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (AvH) (Ref 3.3-1228176-FIN-HFST-P) and the German Research Foundation (DFG), (AB 1073/1-1), Temesgen Abera, Ph.D. in Germany.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.A.A., E.E.M., and D.Z. conceptualize the study. T.A.A. and E.E.M. designed the methodology. J.H. and S.W. processed airborne laser scanning data. E.E.M., P.K.E.P., J.H., and T.A.A. collected TMS4 data. B.T.H. and M.A.M. collected field verification data from Ethiopia. T.A.A. performed the analysis and wrote the initial manuscript. D.Z., E.E.M., J.H., A.H., S.A., P.K.E.P., B.T.H., A.M., and M.A.M., contributed to the scientific discussion. D.Z. supervised the study. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Tina Christmann, Jorge Cueva-Ortiz and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Yi Jiao and Mengjie Wang. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abera, T.A., Maeda, E.E., Heiskanen, J. et al. Deforestation reduces microclimate buffering of African montane forests. Commun Earth Environ 6, 877 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02950-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02950-6