Abstract

Droughts and heatwaves are linked through different land-atmosphere coupling pathways. While high temperatures and depleted soil moisture (SM) characterize all drought-heatwave events, latent heat flux (LHF) reveals the dominant forcing mechanism driving these events. Our grid-based analysis of six drought-heatwave events since 2000 shows spatially inhomogeneous land-atmosphere coupling associated with surface flux partitioning. Atmospherically driven regimes, characterized by increased LHF following hot temperature anomalies, accounted for the majority of the 2022 East Asia event (64.8%). Land surface-driven regimes, exhibiting LHF deficits following dry SM anomalies, were most prevalent in the 2023 Central America event (45.4%). Using a medium-range forecast model, we reproduced both events and showed that the water-limited (2023 Central America) case exhibits a lead-time predictability improvement of about 2-3 days relative to the energy-limited (2022 East Asia) case. These results highlight the limits of domain-averaged coupling in the model and the potential to improve the model forecasted drought-heatwaves when incorporate regime-based characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Numerous studies have identified land–atmosphere (L–A) interactions as a key mechanism in shaping compound drought-heatwave events1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. These interactions operate through two pathways: ‘upward’ coupling, characterized by decreased soil moisture (SM), followed by reduced evapotranspiration, and increased sensible heat flux (SHF) and surface air temperature; and ‘downward’ coupling, characterized by increased surface air temperature, driving increased evapotranspiration, leading to decreased SM (refer to schematics in Fig. 9 of ref. 2; Fig. 6 of ref. 6; Fig. 2 of ref. 7; Fig. 2 of ref. 10). The direction of L–A coupling mechanism during compound drought-heatwave events is mainly determined by the surface water-energy balance2,12,13,14. When SM falls below a specific threshold called the critical SM, evapotranspiration is constrained by SM availability, placing the system in a water-limited condition. In this case, SM depletion follows the upward coupling pathway, leading to increased surface temperature and the subsequent heatwave amplification1,4,5,8,11,15,16. This process is the typical characteristic of SM drought, often triggered by precipitation deficits17. Conversely, when SM is above the critical SM, evapotranspiration is primarily governed by atmospheric conditions such as downward shortwave radiation, surface wind, vapor pressure deficit, and especially surface temperature. In this energy-limited regime, rising air temperatures accelerate SM decline, following a downward coupling pathway. Such interactions are a key source feature of heatwaves, often linked to anticyclonic circulation7,18. This downward coupling process has recently gained growing attention in the hydrometeorological community under the concept of ‘flash droughts’, which emphasize the rapid onset or intensification of drought—particularly SM decline—over much shorter timescales compared to the conventional ‘seasonal droughts’19,20,21,22,23,24,25.

While it is well established that evapotranspiration determines the dominant L–A coupling pathway in compound drought-heatwave events, past studies relying on data averaged over larger space and timescales have inherent limitations26. These studies primarily capture the prevailing coupling behavior but often overlook spatial variations and the temporal evolution of SM-evapotranspiration relationships. During a compound drought-heatwave event, these spatial differences can result in inhomogeneous L–A coupling regimes. Consequently, both upward and downward coupling can coexist within an event, influencing the event’s progression and overall characteristics. Therefore, understanding how inhomogeneous L–A coupling regimes shape compound drought-heatwave events is crucial for improving predictions and developing more effective mitigation strategies.

Here, we aim to advance the understanding of how variability in L–A coupling regimes shapes the overall characteristics of compound drought-heatwave events. To achieve this, we analyze six severe compound drought-heatwave cases observed over the Northern Hemisphere after the year 2000, using observationally-constrained data. These cases are (1) the 2003 Western Europe case1,3,27,28,29,30, (2) the 2010 Eastern Europe and Russia case3,29,30,31,32, (3) the 2012 contiguous United States case33,34,35,36,37,38, (4) the 2021 Pacific Northwest case39,40,41,42,43,44, (5) the 2022 East Asia case23,45,46,47, and (6) the 2023 Central America case48,49. These six cases were selected for their historical significance, as they represent some of the most impactful compound drought-heatwave cases in the 21st century, resulting in substantial human and economic losses. Furthermore, we investigate how L–A regime-dependent behaviors influence the forecast skill of compound drought-heatwave events using a state-of-the-art forecast model. Finally, we present a schematic illustration that highlights the connections between the overall characteristics of drought-heatwave events, L–A coupling regimes, and the underlying drivers of SM-evapotranspiration coupling.

Spatiotemporal characteristics of compound drought-heatwave events

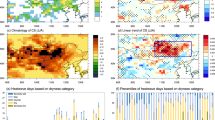

Figure 1a displays the spatial distribution of June-July-August (JJA) mean daily maximum surface air temperature (TMAX) anomalies (TMAXanom; the subscript ‘anom’ denotes the anomaly of the variable hereafter) during the six selected drought-heatwave cases. All anomalies are relative to the climatology over 1991–2020 or 2000–2020 in our observationally-based reference datasets (see “Data and methods” section). All cases were characterized by extremely hot conditions, with a 3-month mean TMAXanom sometimes exceeding 4 K across extensive regions. A large spatial extent of the areas where the TMAXanom exceeds two standard deviations (non-hatched areas in Fig. 1a) exists in all cases. The 2012 case had the smallest affected area among these cases, which covered approximately 1.2 million km2, comparable to the size of the Republic of South Africa (Supplementary Table 1). The 2010 case had the largest affected area of 3.5 million km2, surpassing the size of the Republic of India (Supplementary Table 1). Anomalous anticyclonic circulations indicated by positive 500-hPa geopotential height anomalies (GPHanom; black contours in Fig. 1a), although varying in intensity across cases, were simultaneously observed over those regions.

a JJA mean TMAXanom (K) based on ERA5-Land. Non-hatched areas indicate regions exceeding two standard deviations of TMAX based on the 30-year JJA record. Black contours represent JJA mean GPHanom (gpm) based on the ERA5 dataset, with contour values varying across panels. b JJA mean SManom (m3 m−3; color) based on the reference data. The dotted areas represent regions where the temporal correlation of SManom during JJA among the three different land surface analysis datasets is statistically significant (p < 0.05) for all dataset pairs (i.e., GLEAM and GLDAS; GLEAM and ERA5-Land; ERA5-Land and GLDAS). Overlaid gray shading shows JJA mean PRanom (mm day−1), displaying only positive precipitation anomalies. c Lead-lag time series of TMAXanom (magenta solid line), SManom (green solid lines), and LHFanom (cyan solid lines) within a 31-day time window, area-averaged over the non-hatched areas shown in (a). Each variable is standardized based on its mean and standard deviation during the 31-day time window. The abscissa indicates the days relative to the peak day of the heatwave (day 0; marked with a gray line). Light (bold) colored lines for SManom and LHFanom correspond to individual (reference) land surface analysis datasets.

Furthermore, anomalous dry conditions were predominantly observed across all cases (Fig. 1b). The spatial patterns of dry surface SManom based on the reference data (see “Data and methods” section) were significantly anti-correlated with those of TMAXanom, with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.7 for most of the cases (Supplementary Table 1). This indicates that severe drought conditions generally coexisted with the extremely high temperatures during the same period. Notably, negative SManom was pronounced (≤0.05 m3 m−3) in the core regions of the heatwaves (i.e., the non-hatched areas in Fig. 1a), implying the potential role of L–A interactions in amplifying drought and heatwave conditions. Concurrently, these regions generally exhibited negative precipitation anomalies (PRanom), as indicated by the areas without overlaid gray shading in Fig. 1b.

The temporal evolution of heatwaves and droughts spanning 15 days before and after the peak day (day 0) is presented in Fig. 1c. Consistent patterns of TMAX and SM behavior emerge across all cases: TMAXanom increased from 15 days prior to the peak, reaching their maximum on day 0, before gradually decreasing (magenta line in Fig. 1c). Simultaneously, SManom was negatively coupled to the heatwave’s onset and decay phases, decreasing to their minimum around day 0 before beginning to recover (green line in Fig. 1c). The day of SManom minimum nearly coincided with the maximum TMAXanom day (i.e., day 0) in most cases, although peak days were defined only based on TMAXanom (see “Data and methods” section). On day 0, all cases experienced extremely hot and dry conditions, with \({{{{\rm{TMAX}}}}}_{{{{\rm{anom}}}}}^{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\) (the superscript p denotes the value of the variable at day 0 hereafter) ranging from 6.7 K to 11.7 K and \({{{{\rm{SM}}}}}_{{{{\rm{anom}}}}}^{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\) ranging from −0.074 to −0.058 m3 m−3 (Supplementary Table 2). During the 31-day time window, hot anomalies persisted from approximately 10 days before to 5 days after the peak for all cases, and dry SManom were evident throughout the entire 31-day period (raw SM anomalies, prior to standardization, are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). This highlights the dependence between drought and heatwave development, emphasizing not only their spatial coupling but also their temporal co-evolution. These findings were consistent across all three analyzed datasets: For nearly all cases (except for GLDAS data from +12 to +15 days in 2012 and from +13 to +14 days in 2022), standardized SManom from each dataset were within ±1 standardized anomaly of the reference data (see “Data and methods” section). Furthermore, statistically significant temporal correlations among all dataset pairs for JJA SManom were observed over >95% of the entire domains (dotted areas in Fig. 1b).

The consistency in the temporal evolution of TMAX and SM across all the cases is not seen in latent heat flux anomaly (LHFanom; cyan lines in Fig. 1c), with LHF in some cases closely aligned with the TMAX signal, and other cases closely aligned with the SM signal. For the case in 2022, LHFanom initially increased and peaked at 20.6 W m−2 on day 0, and the positive anomalies remained throughout the −15 to +5-day time window (Fig. 1c; see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). This case shows a dominant coupling of LHF with atmospheric demand (i.e., TMAX) rather than with SM. Conversely, in the 2023 case, LHFanom consistently decreased prior to day 0 (−24.1 W m−2 on day 0) and increased a day after the heatwave peak, indicating a strong coupling with SM (Fig. 1c; see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). While other cases did not exhibit as distinct coupling behaviors of LHF as the 2022 and 2023 cases, qualitative differences were still discernible. For instance, the temporal patterns of LHFanom in the 2003, 2010, and 2021 cases were somewhat coupled to TMAXanom, resembling the 2022 case. Conversely, in the 2012 case, LHFanom had a stronger correlation with SManom than with TMAXanom, as in the 2023 case. Although LHFanom demonstrated greater uncertainty across the three datasets compared to SM, these uncertainties did not significantly affect the interpretation of coupling behaviors.

Dominant land–atmosphere coupling regimes vary in an extreme event

The results in the previous section imply that there is a “dominant” coupling behavior for individual events. But can this dominance be quantitatively assessed? To address this, we investigate beyond spatial averages and instead focus on grid-by-grid analyses.

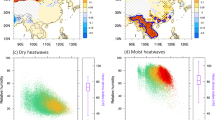

Figure 2 quantifies the grid-by-grid L–A coupling behaviors in each of the analyzed compound drought-heatwave cases based on temporal correlations (R) between SManom and LHFanom (abscissa) and between TMAXanom and LHFanom (ordinate) during the 31-day time window. The dots are colored when co-evolution of drought and heatwave is identified locally (i.e., R(SManom, TMAXanom) ≤ 0.5 with p < 0.05). We find that the dots have a string-shape distribution across this phase diagram, and such a feature is consistent among all events analyzed. This distribution suggests a negative correlation between R(TMAXanom, LHFanom) and R(SManom, LHFanom) when SManom and TMAXanom are significantly anti-correlated. We divide the phase diagram into seven domains, based on the ranges of the two quantified temporal correlations. Each domain represents a distinct L–A coupling behavior, termed Regime I–Regime VII.

Scatter plot illustrates the temporal correlation coefficients between SManom and LHFanom (R(SManom, LHFanom); abscissa) and TMAXanom and LHFanom (R(TMAXanom, LHFanom; ordinate). Temporal correlations were calculated within a 31-day time window (see lead-lag time series in Fig. 1c). Each dot represents a single grid cell within extreme heat regions (non-hatched areas in Fig. 1a), based on the reference data. Only grid cells with R(SManom, TMAXanom) < −0.5 and p < 0.05 are colored; other grid cells are shown as x-shape markers without shading. Dot colors indicate kernel density with a bandwidth of 0.1 (shaded), and contour lines represent a kernel density of 0.5 derived from GLDAS (blue), ERA5-Land (orange), and GLEAM (yellow). Contour lines were calculated based on the same criteria as the colored dots. Each subplot is divided into seven coupling regimes (Regime I–Regime VII) based on the two values of correlation coefficients, indicated as boxes. Percentage values at the bottom of each box region represent the proportion of grid cells within that regime relative to the total number of grid cells. The proportions of grid cells not included in the coupling regimes are represented as black labels in the bottom left. Gray labels indicate the percentage values of uncolored markers.

For example, Regime I (−1 < R(SManom, LHFanom) < −0.5 and 0.5 < R(TMAXanom, LHFanom) < 1) corresponds to areas of strong ‘downward’ coupling (i.e., energy-limited conditions), where an increase in TMAX enhances LHF, which in turn reduces SM (hereafter TMAX-LHF coupling). In contrast, Regime VII (0.5 < R(SManom, LHFanom) < 1 and −1 < R(TMAXanom, LHFanom) < −0.5) is the area of strong ‘upward’ coupling (i.e., water-limited conditions), where a decrease in SM and LHF leads to an increase in TMAX (hereafter SM-LHF coupling). Thus, the dominant L–A coupling that happened in a particular drought-heatwave case can be quantitatively indicated by its distribution of color dots in the seven regimes. Notably, all cases had at least some grid cells characterized by strong TMAX-LHF coupling (e.g., Regime I and Regime II), strong SM-LHF coupling (e.g., Regime VI and Regime VII), and coupling behaviors not clearly falling into either category (e.g., Regime III–V).

The spatially prevailing coupling regime varies across the six cases. In the 2022 case, Regime I (Regime II) accounted for 48.48% (19.89%) of the total grid cells, representing the dominant role of TMAX-LHF coupling in this compound drought-heatwave event. In contrast, the 2023 case exhibited a dominance of SM-LHF coupling behavior, accounting for 37.81% (9.31%) of the total grid cells in Regime VII (Regime VI). This finding supports the area-averaging result and further represents the distinct LHF coupling behaviors between the 2022 and 2023 cases (Fig. 1c). The 2003 case had a similar coupling behavior to the 2022 case, with the dominance of TMAX-LHF coupling. However, unlike 2022, the 2003 proportion of grid cells in Regime II (21.21%) was not only higher than that in Regime I (16.74%), but the total proportion summed over Regime III to Regime VII was also higher (32.23%) compared to 2022 (11.91%), indicating a less pronounced TMAX-LHF coupling behavior. Similarly, the 2012 case showed a weaker SM-LHF coupling dominance (11.99% of Regime VI and 11.1% of Regime VII) compared to the 2023 case, where most grid cells were classified into Regime VII. The 2021 case presented unique characteristics, as grid cells categorized into Regime II through Regime VI were more prevalent compared to those in Regime I or Regime VII, with Regime IV being the most dominant (14.55%). This indicates that no clearly dominant LHF coupling behavior was observed within the 31-day time window of this compound drought-heatwave event. Instead, the distribution suggests the possibility that a temporal transition in coupling behavior occurred during this period. In other words, L–A coupling behavior may have shifted from TMAX-LHF coupling to SM-LHF coupling over time in these “intermediate” regimes (see “Discussion” section). The 2010 case covered the largest geographic area (Supplementary Table 1), and different sections of the vast region seemed to display different coupling behaviors. It was characterized by both SM-LHF and TMAX-LHF coupling regimes (24.25% of Regime I and 11.51% of Regime VII), while the proportion of grid cells classified into the intermediate regimes (Regime III to Regime V) was relatively small, with a total of only 8.53% of the grid cells. These spatially varying dominant coupling regimes explain the non-monotonic temporal evolution of LHF in several cases (Fig. 1c) results from the area-averaging of coupling behaviors within the analyzed region. The above reference data-based interpretations of the distinct spatial dominance of L–A coupling behaviors across each case were generally consistent with the results derived from GLDAS, ERA5-Land, and GLEAM data (depicted as red, blue, and yellow contours in Fig. 2). However, an exception was noted for the 2021 case, where GLEAM data had a more pronounced SM-LHF coupling compared to the other datasets.

Meanwhile, the uncolored markers (R(SManom, TMAXanom) > −0.5 or p > 0.05) tended to cluster in the top-right quadrant of the phase diagram. This suggests that LHFanom had simultaneous positive correlations with both SManom and TMAXanom in regions without significant coupling between drought and heatwave (i.e., no co-evolution of drought and heatwave). We have found that the temporal variability of TMAXanom does not substantially differ between the weakly and strongly coupled regions (dashed vs. solid magenta lines in Supplementary Fig. 2a), but the variability of SManom is relatively lower in the weakly coupled regions compared to the strongly coupled regions (dashed vs. solid green lines in Supplementary Fig. 2b). Considering that the onset and decay phases of heatwaves (i.e., temporal variability of TMAXanom) were clearly observed regardless of the strength of the L–A coupling, the weak L–A coupling in these regions can be attributed to the temporal variability of SManom. Therefore, the lower TMAX-SM correlation (i.e., weak L–A coupling) in these regions primarily reflects the reduced temporal variability in SM.

Partitioning of surface energy fluxes links to drought-heatwave interactions

To examine how the different dominant L–A coupling regimes are associated with the local drought-heatwave interactions, we analyzed evaporative fraction (EF = LHF/(LHF + SHF); see “Data and methods” section) on the heatwave peak day (EFp) across the different coupling regimes in each extreme case. In all cases, EFp was higher in Regime I than Regime VII (values in the upper left corner of Fig. 3). The clear decreasing trends of EFp from Regime I to Regime VII were also observed (Supplementary Fig. 3). Therefore, \({{{{\rm{LHF}}}}}_{{{{\rm{anom}}}}}^{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\) was lower and \({{{{\rm{SHF}}}}}_{{{{\rm{anom}}}}}^{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\) was higher in Regime VI and Regime VII compared to Regime I and Regime II (Supplementary Table 3). These indicate that drought-heatwave interactions transition from being dominated by downward coupling processes (heatwave to drought) with more energy-limited conditions towards being dominated by upward coupling processes (drought to heatwave) with more water-limited conditions.

Scatter plot showing SM and EF on day 0 (SMp and EFp) for Regime I (top) and Regime VII (bottom) based on the reference data. The dots represent SMp and EFp of each grid point over the respective regime. Dot colors indicate kernel density bandwidths of 0.1 (SMp) and 5.0 (EFp). Yellow diamond markers indicate the mean values of SMp and EFp for each regime. The quantitative values corresponding to these markers are displayed in the upper left corner of each subplot.

In addition, Fig. 3 clearly shows that, in Regime I (upper panels), EF is mostly independent of SM (R(SM, EF)~0), likely because SM values in this regime exceed the critical SM threshold separating water-limited conditions from energy-limited conditions. In contrast, in Regime VII, EF becomes sensitive to changes in SM (i.e., R(SM, EF)~1), indicating SM values are below a critical threshold (bottom panel of Fig. 3) representing a water-limited condition. The quantitative values of R(SM, EF) for each regime, as well as the clear increasing trend of R(SM, EF) from Regime I to Regime VII, are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. Accompanied by the simultaneous decreases in SM and EF from Regime I to Regime VII, these results reveal the full picture of the association between L–A coupling regimes and critical SM: The spatial heterogeneity of SM and critical SM played as a key factor in determining surface energy partitioning across different regimes, eventually influencing the dominance of upward or downward coupling during compound drought-heatwave events.

Compound drought-heatwaves in the water-limitation condition show higher predictability

Next, we assess the model’s ability to predict the spatial pattern of coupling regimes using the medium-range forecasts (~+10-day) of the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) System for High-resolution prediction on Earth-to-Local Domains (SHiELD). The forecast skill for compound drought-heatwave events under different conditions is also evaluated (see “Data and methods” section). We focus on the two representative cases, the 2022 East Asia and the 2023 Central America cases, which exhibited distinct dominant coupling behaviors (i.e., TMAX-LHF and SM-LHF coupling, respectively).

Overall, the 10-day SHiELD forecasts reasonably represented the distinct coupling behaviors of the 2022 and 2023 cases (Fig. 4). Similar to the results from the observationally-constrained datasets, negative correlations between TMAX and SM were shown in most forecast runs starting from different lead times (Fig. 4a, b). Note that this result is based on actual values rather than anomalies (see “Data and methods” section). Importantly, the forecasted temporal evolution of LHF reflected the distinct coupling regimes of each case; in 2022, the LHF forecasts were correlated with the forecasted TMAX (Fig. 4a), while in 2023, they were correlated with the forecasted SM (Fig. 4b). These characteristics were also generally consistent across all forecast runs starting from different lead times.

a, b Lead-lag time series of TMAX (K; left), SM (m3 m−3; middle), and LHF (W m−2; right) within a 31-day time window, area-averaged over the non-hatched areas shown in Fig. 1a. The raw (non-standardized) values for each variable are shown on the ordinate, and the abscissa indicates the days relative to the peak day of the heatwave (day 0). Each solid line represents forecast results of the lead times from +1 to +10 days, with a darker orange color indicating longer lead times. c, d Sankey diagrams of land–atmosphere coupling regimes. Each block represents a specific land–atmosphere coupling regime, as the gray blocks represent areas that are not classified into Regime I–Regime VII. Percentages within the blocks indicate the proportion of grid numbers in each regime to the total number of grid points in the non-hatched areas shown in Fig. 1a. The three columns from left to right represent results derived from the reference data, +1-day forecast of SHiELD, and +10-day forecast of SHiELD. Links between blocks visually illustrate the differences of regimes between columns, with only changes greater than 1% displayed. e, f The forecast skill (temporal correlation coefficient between SHiELD and the reference data; ordinate) during JJA for TMAX (orange bars) and SM (green bars) at different lead times (abscissa). Error bars denote the 25th and 75th percentiles of the forecast skills across the domain. The left panel (a, c, e) represents the results for the 2022 case, while the right panel (b, d, f) represents the results for the 2023 case.

We further examine the variation for the proportion of coupling regimes derived from the reference data, +1-day, and +10-day lead times (Fig. 4c, d). In 2022, the TMAX-LHF coupling (Regimes I and II) remained dominant throughout the forecast lead times, accounting for 68.37% in the reference data, 52.36% at +1-day, and 51.39% at +10-day lead times (Fig. 4c). In contrast, in 2023, the SM-LHF coupling (Regimes VI and VII) consistently maintained dominance, covering 47.12% in the reference data, 48.55% at +1-day, and 55.56% at +10-day lead times (Fig. 4d). The spatial distributions of each regime were also highly consistent among the reference, +1-day, and +10-day lead times in both 2022 and 2023 cases (Supplementary Fig. 5). The differences among the three columns (reference data, +1-day forecast, and +10-day forecast) primarily occurred within adjacent coupling regimes (e.g., transitions between Regimes I and II in 2022, or between Regimes VI and VII in 2023). Other major differences were observed between coupling regimes and regions where L–A coupling was not significantly detected (links connected to gray blocks in Fig. 4c, d, excluding links between gray blocks).

The temporal correlation coefficients between the SHiELD forecasts and the reference data during JJA (simply referred to as “forecast skill” hereafter) for TMAXanom and SManom are represented in Fig. 4e, f. In the 2023 case, SM variations played a critical role in driving TMAX. Therefore, since SM has a longer memory than atmospheric variables, its persistence contributed to better forecast skill for both SM and TMAX within the medium-range time scale (Fig. 4f). Conversely, in the 2022 case, TMAX variations were not primarily controlled by SM. As a result, the model exhibited a more rapid decline in forecast skill of TMAX and SM with increasing lead time (Fig. 4e). Compared to 2022, the 2023 forecast skill was superior from a +4-day lead time for TMAX and a +6-day lead time for SM, and the advantage in forecast skill increased at longer lead times. This result reveals the impact of long memory of land surface conditions in water-limited conditions, even within 10-day forecast lead times10,11,50,51. To further assess the robustness of this finding, we extended the forecast skill analysis to 5-year (2019–2023) JJA within the fixed domains defined by the 2022 East Asia and 2023 Central America cases (Supplementary Fig. 6). For each of the 5 years, we reclassified grid cells within the fixed domain to Regimes I–VII. By focusing on grid cells classified as Regime I (East Asia) and Regime VII (Central America) across 2019–2023, we found that SHiELD forecast skill at a 10-day lead time was systematically higher in Central America than in East Asia for both TMAX and SM, confirming that the enhanced predictability in water-limited regimes is a robust and general feature.

Discussion

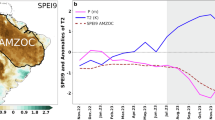

The concurrent evolution of droughts and heatwaves can be characterized by the dominance of upward or downward land–atmosphere coupling. This has mostly been studied using data averaged over larger space and timescales in the past. This study provides a perspective on understanding compound drought-heatwave events by quantitatively separating upward and downward coupling mechanisms across the domain affected by compound drought-heatwave events. By examining six historically impactful events, a quantitative analysis with phase diagrams revealed that each case, and even each region within a single case, exhibited significantly distinct coupling behaviors. This notable spatial variability of land–atmosphere coupling behavior stemmed from the distinct partitioning of surface fluxes. We further show that such regime-specific coupling can influence forecast skill, even on medium-range timescales. Figure 5 demonstrates how these findings are linked to each other:

a Scatter plot of temporal correlations between SManom-LHFanom (abscissa) and TMAXanom-LHFanom (ordinate) for all six cases, with the analysis domain and criteria identical to Fig. 2. Each point is colored by EFp values. The scatter plot is divided into three regions: blue box for Regime I–Regime II, gray box for Regime III–Regime V, and red box for Regime VI–Regime VII. The embedded time series represents the all-case-averaged temporal evolution of standardized TMAXanom (magenta lines), SManom (green lines), and LHFanom (cyan lines) for Regime I–Regime II (upper right) and Regime VI–Regime VII (bottom left). The time series were derived following the same method and scale as Fig. 1c. The grid points with the highest kernel density for each case are indicated as yellow stars. b Conceptual schematic diagrams of dominant coupling regimes. The upper (bottom) panel corresponds to the TMAX-LHF (SM-LHF) coupling dominant regime. Cyan arrows represent LHF, and orange arrows represent SHF, with arrow length denoting relative magnitude. The adjacent x-y plots illustrate the relationship between SMp and EFp in each regime, while the adjacent bar plot shows the +10-day forecast skill of TMAX and SM for the 2022 and 2023 cases. CSM denotes the critical SM. Blue and red arrows indicate upward and downward coupling, respectively.

Spatial differences in coupling regimes are closely associated with EF, which quantifies the partitioning of surface energy fluxes between LHF and SHF. In regions dominated by TMAX-LHF coupling, EF was significantly higher (blue dots in Fig. 5a), reflecting downward coupling where high temperatures led to the decline of SM by excessive evapotranspiration (indicated as upper subset in Fig. 5b). Conversely, SM-LHF coupling regimes were characterized by lower EF values (red dots in Fig. 5a), indicative of upward coupling where dry surface conditions amplifies the heatwave intensity by increasing SHF (indicated as bottom subset in Fig. 5b). In TMAX-LHF coupling dominant regimes, weak temporal correlations between SM and EF were observed, suggesting that the critical SM was generally below the SM variations (upper schematic x-y plot in Fig. 5b). In contrast, in SM-LHF dominant regimes, there was a significant positive correlation between soil moisture and EF, implying the critical SM mostly exceeded the SM variations (bottom schematic x-y plot in Fig. 5b). GFDL SHiELD’s medium-range forecast for compound drought-heatwave events was closely associated through regime-specific L–A coupling, with LHF playing a critical role in linking the land and atmosphere (upper and bottom schematic flowcharts in Fig. 5b). Importantly, higher forecast skill was observed in the 2023 case than the 2022 case due to the longer soil moisture memory (bar plot in Fig. 5b).

We primarily focused on the regimes where upward or downward coupling behaviors were clearly observed. However, regimes where LHF was not significantly correlated with either SM or TMAX were also observed across all cases (gray box in Fig. 5a). Notably, these regimes (e.g., Regime III–Regime V), which were most prominent in the 2021 case, represent an “intermediate regime” in which coupling signals are weak or negligible. This characteristic can be interpreted as evidence of a temporal transition between coupling behaviors during the evolution of compound drought-heatwave events. Conceptually, in the early stages of a compound drought-heatwave, SM exceeds the critical SM, resulting in TMAX-LHF coupling. As SM decreases below the critical SM, the coupling behavior shifts to SM-LHF coupling. Such transitions between regimes have been emphasized on the climate time scale and reported to influence the fidelity of climate models in projecting land surface temperature15,16,52. However, our findings highlight that similar transitions can occur within a 31-day time scale during compound drought-heatwave evolution14,25,32,46. Our additional analysis using 15-day windows, e.g., 15 days before the peak (days −15 to 0) and 15 days after the peak (days 0 to +15), shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, further supports this interpretation. The results in 2021 show that the proportion of transitional regimes (Regime III–Regime V) decreases in the split-window analysis, with more grid cells shifting into “extreme” L–A coupling regimes (i.e., Regime I or Regime VII), in contrast to the result using 31-day window (Fig. 2). This suggests that transitions in L–A coupling behavior often occur near the peak stage of compound drought-heatwave events, which can be fully captured when using a longer temporal window. Thus, the accurate representation of these transitions in subseasonal time scale numerical weather prediction models is critical for improving the predictability of heatwaves and flash droughts.

While this study emphasizes the importance of regime-dependent L–A coupling in compound drought-heatwave events, significant challenges remain: A deeper understanding of the physical and dynamical mechanisms governing these coupling regimes is necessary, as our classification was based primarily on the statistical relationship between SM and LHF (or EF) rather than on explicit process-based diagnostics53,54. The scarcity of observational datasets limits the robustness of regime classification and validation, as most studies—including this study— heavily rely on gridded land model-based analysis datasets (see “Data and methods” section). Although remote sensing and in-situ observations are increasingly being utilized10, their coverage and consistency remain insufficient. Further advancements in high-resolution numerical modeling are also required to better capture the spatial heterogeneity of coupling behaviors55, including improved representations of land surface processes such as vegetation dynamics and stomatal feedback during the onset and decay phases of compound events56. Upper-level circulation and precipitation also remain crucial factors influencing the evolution of drought-heatwave interactions7,8. Our regime-based approach is a useful flag for diagnosing and addressing these challenges. For example, phase diagrams revealed substantial uncertainties in land surface analysis datasets for the 2021 event, where ‘intermediate’ regimes were dominant (red, blue, and yellow contour lines in Fig. 2). How can we mitigate these uncertainties and integrate them to improve numerical models?

Our additional analyses further reveal that L–A coupling regimes exhibit systematic associations with background climatic conditions. For each case, we calculated 20-year daily climatological means on the peak day for grid cells defined as different L–A coupling regimes. Specifically, regime-dependent climatological means of TMAX, SM, potential ET (PET), and PR demonstrate a clear trend, with water-limited regimes characterized by higher climatological TMAX and PET and lower SM and PR (Supplementary Fig. 8). In addition, although interannual variability is evident, the dominant coupling regimes remained largely stable within the analyzed areas over 2000–2023, particularly in regions with strong water- or energy-limited conditions such as 2022 East Asia case and 2023 Central America case (Supplementary Fig. 9). These findings highlight that the proposed regimes are not only mechanistically distinct but also regionally consistent, largely reflecting the influence of local aridity and climatic background. We note, however, that longer-term shifts in coupling regimes may occur under significant climatic changes, as suggested by a recent study52.

The co-evolution of severe droughts and heatwaves has been interpreted as the result of L–A feedback, accompanying synergetic interaction between downward and upward L–A coupling6. However, our findings demonstrate that the two coupling regimes cannot spatiotemporally coexist. The L–A feedback amplifying droughts and heatwaves requires a temporal transition from downward to upward coupling regimes in a certain region32. We found that grids exhibiting the synergetic drought-heatwave interactions were spatially less dominant than grids characterized by one-way coupling in many cases (Fig. 2). This implies that conventional approaches relying on event domain-averaging can underestimate the role of L–A feedback in compound drought-heatwave events. Thus, efforts leveraging this quantitative approach will be essential in refining our understanding of drought-heatwave interaction within diverse L–A coupling regimes and improving forecast skill for compound drought-heatwave events52.

Data and methods

Analysis dataset: TMAX

TMAX was chosen as a key variable due to its critical role in defining heatwaves and its strong coupling with surface hydrological processes4,5,9,10. The TMAX data used in this study was obtained from the Copernicus Climate Data Store (CDS) through the ERA5-Land57 Daily Statistics dataset. ERA5-Land is a reanalysis product with a horizontal resolution of approximately 9 km, specifically developed for land applications to provide accurate and high-resolution datasets of near-surface variables. The dataset offers a suite of daily aggregated statistics derived from hourly reanalysis data. For this study, TMAX was computed as the highest temperature recorded within a 24-h period based on the hourly dataset, defined from 0 Z to 0 Z. We extracted TMAX values from mid-May to mid-September over the regions of interest to account for the temporal window required for the lead-lag analysis (see “Lead-lag time series for drought-heatwave events” section for details). The 30-year (1991–2020) climatological baseline was used to calculate the anomaly. The data was interpolated to a consistent grid to match other land surface datasets used in this study.

Analysis dataset: land surface variables

Land surface analysis datasets have the advantage of providing homogeneous, long-term gridded land surface characteristics. However, land surface variables (e.g., SM, LHF, and SHF) are known to have larger uncertainties compared to other datasets for near-surface meteorological variables, such as TMAX58,59,60. Ideally, in-situ-based observations would be used to address this issue, but their relatively limited spatiotemporal coverage restricts the scope of analysis. Thus, we utilized three different land surface analysis datasets, which are extensively used in the hydrometeorological community, to ensure a robust analysis of these variables. The first dataset is GLDAS61, which provides 3-hourly data generated by the Noah Land Surface Model (Noah-LSM) at a horizontal resolution of 0.25°. For this study, the 3-h outputs (00, 03, 06,…, 21 UTC) were averaged to derive daily values. The second dataset is ERA5-Land57, a reanalysis product (c.f., same source to the TMAX). ERA5-Land offers high-resolution hourly data (~9 km) specifically tailored for land surface applications. It is produced by replaying the land component of the ERA5 climate reanalysis at an enhanced resolution with advanced land-surface physics. The land model used in ERA5-Land is the Hydrology-Tiled ECMWF Scheme for Surface Exchanges over Land (H-TESSEL). Daily values for ERA5-Land were calculated using the +24-h integration from each initialization date, representing the accumulated fluxes over a 24-h period, which were then divided by 86,400 s. Lastly, we used the GLEAM dataset62, which provides pre-computed daily estimates of land surface water and energy fluxes at a resolution of 0.1°. GLEAM is a set of algorithms dedicated to estimating terrestrial evaporation and SM contents in surface and root zone from satellite data. It extensively relies on satellite observations to derive evaporation components, making it distinct from model-only-driven products.

Various studies have utilized indices such as root zone SM and other drought-related metrics to represent drought conditions. However, considering the focus of this study on medium-range forecasts, the evolution of drought-heatwave events within a 31-day time window, and representing L–A interactions, surface SM (0–10 cm for GLDAS and GLEAM and 0–7 cm for ERA5-Land) was chosen as the representative variable for drought conditions, and it is simply referred to as ‘SM’ throughout this study. Given that this study focuses more on daily variations rather than absolute soil moisture values, differences in soil layer depth between datasets were considered negligible. We confirmed that applying a linear interpolation between the first (0–7 cm) and s (7–28 cm) soil layers in ERA5-Land to estimate SM at 0–10 cm did not result in any significant differences in the interpretation of the results. Since both evapotranspiration and LHF effectively represent the physical relationship between land and atmosphere, numerous previous studies (refer to the “Introduction” section) have primarily used LHF as the key parameter for L–A interactions. This study also adopts LHF instead of evapotranspiration as a main land surface variable to maintain consistency with established research. For ERA5-Land, lakes were assigned a constant value of SM = 0, while flux variables such as LHF and SHF contained non-missing values. To address this inconsistency, a mask file was created to identify all grid points where SM remained constant at 0 throughout the entire period. These points were then treated as missing for all variables. In the GLEAM dataset, SM and flux variables had differing sets of missing points. All missing data locations identified across different variables in the GLEAM dataset were combined and uniformly applied to ensure consistency. In our analysis, we present both the averaging of the three datasets, which were referred to as ‘reference data’ in this study, and the individual results from each dataset to account for uncertainties and provide a comprehensive assessment. Unless otherwise specified, the quantitative values presented in the main text represent the average value (i.e., reference data) as a representative value. When averaging GLDAS, ERA5-Land, and GLEAM datasets, calculations were performed at grid points where at least one dataset provided a non-missing value. This approach ensured that even grid points with sparse data availability contributed to the averaging. Given that GLDAS data are only available from 2000 onward, the climatological baseline for all datasets was set to the 2000–2020 period. To ensure consistency across datasets, all data were interpolated to match the spatial resolution of GLDAS (i.e., 0. 25°).

In this study, the relative dominance of L–A coupling processes was determined by the EF, defined as the ratio of LHF to the total surface energy flux (LHF + SHF)10. All EF calculations were based on actual values rather than anomalies. Similarly, when examining the temporal correlation between SM and EF, we used actual SM values instead of SManom. The EF values were multiplied by 100 to represent the values as percentages.

Analysis dataset: atmospheric variables

In addition to the previously mentioned datasets, we incorporated atmospheric variables to enhance our analysis. For GPH, we utilized the ERA5 dataset63, which offers global atmospheric data at a horizontal resolution of approximately 31 km. Daily averages of GPH data were computed from the 6-hourly temporal resolution to align with this study’s temporal framework. The climatological baseline spans from 1991 to 2020. For PR analysis, we employed the Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) Final Run dataset64. The IMERG Final Run data are available at a spatial resolution of 0.1°. We utilized the daily mean precipitation values for our analysis. The climatological period for precipitation was set from 2000 to 2020, consistent with the available data range. These datasets were also interpolated into a consistent grid to match other land surface datasets used in this study.

Lead-lag time series for drought-heatwave events

The 31-day-time-window-based lead-lag time series for drought-heatwave events was derived using area-averaged data that represents the temporal evolution of key variables during the events. To derive this time series, extreme heatwave areas where the JJA mean TMAX for each event exceeded two standard deviations of the JJA mean TMAX for the climatological (1991–2020) period were first identified. For each grid point within these identified areas, the date of the TMAX peak was recorded as the peak day (day 0). SM, LHF, and other relevant variables were then aligned relative to this peak day across all grid points. The aligned values were averaged across the selected extreme heatwave areas to produce an area-averaged lead-lag time series spanning 15 days before and 15 days after the peak day. This alignment allowed for the identification of the temporal evolution of SM, LHF, and TMAX during the onset, peak, and decay phases of the heatwave events. Although the primary analysis period focused on JJA, TMAX, and land surface data from mid-May to mid-September were included to ensure that variables spanning 15 days before and after each peak day (e.g., May 17 for a June 1 peak or September 15 for an August 31 peak) were adequately captured. All variables were temporally smoothed using a 5-day moving average before deriving the lead-lag time series. Sensitivity tests using alternative time windows (e.g., 21 days, covering 10 days before to 10 days after the peak, and 41 days, covering 20 days before to 20 days after the peak) confirmed that the key findings remained consistent. Similarly, applying different smoothing windows (3-day or 7-day moving averages) did not lead to significant changes in the overall results. The standardized anomalies of TMAX, SM, and LHF (shown in Fig. 1c) were obtained by standardizing the raw anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 1) within a 31-day window so that each variable has zero mean and unit standard deviation.

System for High-resolution prediction on Earth-to-Local Domains (SHiELD)

The SHiELD, developed by the GFDL, is a state-of-the-art unified modeling system designed to forecast multi-scale weather phenomena65,66. SHiELD leverages the nonhydrostatic Finite-Volume Cubed-Sphere (FV3) Dynamical Core67,68,69, which enables simulations across a wide range of spatial and temporal scales, from mesoscale events at 3 km resolution over a few hours to global seasonal forecasts at 25 km resolution. This flexibility makes SHiELD an essential tool for studying complex atmospheric processes. In this study, we utilized the global 13-km resolution SHiELD configuration, which serves as the flagship version for real-time forecasts and is actively developed and assessed65,66,70,71,72,73. This configuration is initialized at 00 UTC and 12 UTC using National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) Global Forecast System (GFS) analysis data and integrates over a 10-day forecast window. Significant updates are included in the physics parameterizations, which were originally adapted from the GFS framework to enhance forecast skill in SHiELD, e.g., the Noah land surface model74, the GFDL cloud microphysics scheme version 3, which is fully integrated with FV371,72, the scale-aware TKE-EDMF planetary boundary layer scheme75, and the scale-aware deep and shallow convection parameterization76. Additionally, SHiELD incorporates a mixed-layer ocean model, critically aiding the representation of ocean-atmosphere interactions for simulating phenomena like tropical cyclones and the Madden-Julian Oscillation65. SHiELD currently focuses on deterministic forecasting but is being developed to include ensemble capabilities, which are expected to significantly enhance its performance for subseasonal prediction applications.

To analyze the predictability of L–A coupling in compound drought-heatwave events, raw output from SHiELD simulations initialized at 00 UTC was processed into daily values. The raw data from SHiELD consisted of 241 timesteps per initialization, starting at the initialization time (+00 h) and forecasting hourly from +01 to +240 h. To ensure the data consistently averaged over +00 to +23 h for each day, the final step (+240) was excluded. The lead-lag time series for SHiELD was derived using the same method as the analysis dataset, and the grid-by-grid TMAX peak day (i.e., day 0) and analysis area was defined based on the reference data. To be consistent with the analysis dataset, valid forecast data spanning all lead times from May 17 to September 15 were required for the lead-lag time series analysis. Therefore, we utilized forecast outputs initialized at 00 UTC daily from May 8 to September 15.

To derive L–A coupling regimes and forecast skills for SHiELD forecasts, anomaly correlations need to be calculated. However, since SHiELD is a relatively recently developed modeling system, a climatological record over 20 years is not available. Therefore, anomalies of forecasted TMAX and land surface variables were calculated based on the climatology values of the analysis datasets for the evaluation of coupling regime representation of SHiELD. While this approach introduces a limitation by including the model’s systematic biases, we considered this issue not to be significant, as the main analyses in this study rely on the model forecast data itself rather than anomalies. Additionally, although a variety of datasets were utilized to ensure robustness against uncertainties in the land surface analysis datasets, limitations still exist. Considering these, when evaluating the predictability of land surface variables, we focused on temporal correlation rather than absolute comparisons (e.g., bias, root mean square errors).

Data availability

GLDAS dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.5067/E7TYRXPJKWOQ. ERA5-Land post-processed daily statistics dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.e9c9c792. GLEAM dataset is available at https://www.gleam.eu/. ERA5 dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47. IMERG dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.5067/GPM/IMERGDF/DAY/07.

Code availability

Source code for GFDL SHiELD is available at https://github.com/NOAA-GFDL/SHiELD_build. Other custom codes are direct implementations of statistical methods and techniques that are described in the “Data and methods” section.

References

Fischer, E. M., Seneviratne, S. I., Lüthi, D. & Schär, C. Contribution of land-atmosphere coupling to recent European summer heat waves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, 2006GL029068 (2007).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Investigating soil moisture-climate interactions in a changing climate: a review. Earth Sci. Rev. 99, 125–161 (2010).

Miralles, D. G., Teuling, A. J., Van Heerwaarden, C. C. & Vilà-Guerau de Arellano, J. Mega-heatwave temperatures due to combined soil desiccation and atmospheric heat accumulation. Nat. Geosci. 7, 345–349 (2014).

Benson, D. O. & Dirmeyer, P. A. Characterizing the relationship between temperature and soil moisture extremes and their role in the exacerbation of heat waves over the contiguous United States. J. Clim. 34, 2175–2187 (2021).

Dirmeyer, P. A., Balsamo, G., Blyth, E. M., Morrison, R. & Cooper, H. M. Land-atmosphere interactions exacerbated the drought and heatwave over Northern Europe during summer 2018. AGU Adv. 2, e2020AV000283 (2021).

Hao, Z. et al. Compound droughts and hot extremes: characteristics, drivers, changes, and impacts. Earth Sci. Rev. 235, 104241 (2022).

Domeisen, D. I. et al. Prediction and projection of heatwaves. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 36–50 (2023).

Yoon, D. et al. Role of land-atmosphere Interaction in the 2016 Northeast Asia heat wave: impact of soil moisture initialization. JGR Atmos. 128, e2022JD037718 (2023).

Hsu, H., Dirmeyer, P. A. & Seo, E. Exploring the mechanisms of the soil moisture-air temperature hypersensitive coupling regime. Water Resour. Res. 60, e2023WR036490 (2024).

Seo, E., Dirmeyer, P. A., Barlage, M., Wei, H. & Ek, M. Evaluation of land-atmosphere coupling processes and climatological bias in the UFS global coupled model. J. Hydrometeorol. 25, 161–175 (2024).

Yoon, D., Chen, J.-H. & Seo, E. Contribution of land-atmosphere coupling in 2022 CONUS compound drought-heatwave events and implications for forecasting. Weather Clim. Extremes 46, 100722 (2024).

Budyko, M. I. & Miller, D. H. Climate and life. (1974).

Hobbins, M. T. et al. The evaporative demand drought index. Part I: linking drought evolution to variations in evaporative demand. J. Hydrometeorol. 17, 1745–1761 (2016).

Pendergrass, A. G. et al. Flash droughts present a new challenge for subseasonal-to-seasonal prediction. Nat. Clim. Changl 10, 191–199 (2020).

Duan, S. Q., Findell, K. L. & Wright, J. S. Three regimes of temperature distribution change over dry land, moist land, and oceanic surfaces. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090997 (2020).

Duan, S. Q., Findell, K. L. & Fueglistaler, S. A. Coherent mechanistic patterns of tropical land hydroclimate changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102285 (2023).

Mo, K. C. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Precipitation deficit flash droughts over the United States. J. Hydrometeorol. 17, 1169–1184 (2016).

Black, E., Blackburn, M., Harrison, G., Hoskins, B. & Methven, J. Factors contributing to the summer 2003 European heatwave. Weather 59, 217–223 (2004).

Mo, K. C. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Heat wave flash droughts in decline. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 2823–2829 (2015).

Otkin, J. A. et al. Flash droughts: A review and assessment of the challenges imposed by rapid-onset droughts in the United States. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, 911–919 (2018).

Koster, R. D., Schubert, S. D., Wang, H., Mahanama, S. P. & DeAngelis, A. M. Flash drought as captured by reanalysis data: disentangling the contributions of precipitation deficit and excess evapotranspiration. J. Hydrometeorol. 20, 1241–1258 (2019).

Christian, J. I. et al. Global distribution, trends, and drivers of flash drought occurrence. Nat. Commun. 12, 6330 (2021).

Wang, Y. & Yuan, X. High temperature accelerates onset speed of the 2022 unprecedented flash drought over the Yangtze River Basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105375 (2023).

Yuan, X. et al. A global transition to flash droughts under climate change. Science 380, 187–191 (2023).

Lovino, M. A., Pierrestegui, M. J., Müller, O. V., Müller, G. V. & Berbery, E. H. The prevalent life cycle of agricultural flash droughts. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 73 (2024).

Findell, K. L. et al. Accurate assessment of land-atmosphere coupling in climate models requires high-frequency data output. Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 1869–1883 (2024).

Zaitchik, B. F., Macalady, A. K., Bonneau, L. R. & Smith, R. B. Europe’s 2003 heat wave: a satellite view of impacts and land-atmosphere feedbacks. Int. J. Climatol. 26, 743–769 (2006).

García-Herrera, R., Díaz, J., Trigo, R. M., Luterbacher, J. & Fischer, E. M. A review of the European summer heat wave of 2003. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 267–306 (2010).

Barriopedro, D., Fischer, E. M., Luterbacher, J., Trigo, R. M. & García-Herrera, R. The hot summer of 2010: redrawing the temperature record map of Europe. Science 332, 220–224 (2011).

Stefanon, M., D’Andrea, F. & Drobinski, P. Heatwave classification over Europe and the Mediterranean region. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 014023 (2012).

Hauser, M., Orth, R. & Seneviratne, S. I. Role of soil moisture versus recent climate change for the 2010 heat wave in western Russia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2819–2826 (2016).

Christian, J. I., Basara, J. B., Hunt, E. D., Otkin, J. A. & Xiao, X. Flash drought development and cascading impacts associated with the 2010 Russian heatwave. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094078 (2020).

Mallya, G., Zhao, L., Song, X. C., Niyogi, D. & Govindaraju, R. S. 2012 Midwest Drought in the United States. J. Hydrol. Eng. 18, 737–745 (2013).

Hoerling, M. et al. Causes and predictability of the 2012 Great Plains drought. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 95, 269–282 (2014).

Rippey, B. R. The US drought of 2012. Weather Clim. Extremes 10, 57–64 (2015).

Zhang, L., Jiao, W., Zhang, H., Huang, C. & Tong, Q. Studying drought phenomena in the Continental United States in 2011 and 2012 using various drought indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 190, 96–106 (2017).

Basara, J. B. et al. The evolution, propagation, and spread of flash drought in the Central United States during 2012. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 084025 (2019).

Kam, J., Kim, S. & Roundy, J. K. Did a skillful prediction of near-surface temperatures help or hinder forecasting of the 2012 US drought?. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 034044 (2021).

Bartusek, S., Kornhuber, K. & Ting, M. 2021 North American heatwave amplified by climate change-driven nonlinear interactions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 1143–1150 (2022).

Lin, H., Mo, R. & Vitart, F. The 2021 Western North American heatwave and its subseasonal predictions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097036 (2022).

McKinnon, K. A. & Simpson, I. R. How unexpected was the 2021 Pacific Northwest Heatwave?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100380 (2022).

Schumacher, D. L., Hauser, M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Drivers and Mechanisms of the 2021 Pacific Northwest Heatwave. Earth’s. Future 10, e2022EF002967 (2022).

White, R. H. et al. The unprecedented Pacific Northwest heatwave of June 2021. Nat. Commun. 14, 727 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Increased impact of heat domes on 2021-like heat extremes in North America under global warming. Nat. Commun. 14, 1690 (2023).

Ma, F. & Yuan, X. When will the unprecedented 2022 summer heat waves in Yangtze River Basin become normal in a warming climate?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101946 (2023).

Ni, Y. et al. Shift of soil moisture-temperature coupling exacerbated 2022 compound hot-dry event in eastern China. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 014059 (2024).

Yang, L. & Wei, J. How severe was the 2022 Flash Drought in the Yangtze River Basin?. Remote Sens. 16, 4122 (2024).

Schreck III, C. J. et al. A rapid response process for evaluating causes of extreme temperature events in the United States: the 2023 Texas/Louisiana heat wave as a prototype. Environ. Res. Clim. 3, 045017 (2024).

Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. et al. Extreme terrestrial heat in 2023. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 244–246 (2024).

Richter, J. H. et al. Quantifying sources of subseasonal prediction skill in CESM2. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 59 (2024).

Lim, Y., Molod, A. M., Koster, R. D. & Santanello, J. A. The role of land-atmosphere coupling in subseasonal surface air temperature prediction across the contiguous United States. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 29, 3435–3445 (2025).

Hsu, H. & Dirmeyer, P. A. Soil moisture-evaporation coupling shifts into new gears under increasing CO2. Nat. Commun. 14, 1162 (2023).

Zhou, S., Yu, B., Huang, Y. & Wang, G. The complementary relationship and generation of the Budyko functions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 1781–1790 (2015).

Fu, Z. et al. Global critical soil moisture thresholds of plant water stress. Nat. Commun. 15, 4826 (2024).

Lee, J. & Hohenegger, C. Weaker land-atmosphere coupling in global storm-resolving simulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2314265121 (2024).

Teuling, A. J. et al. Contrasting response of European forest and grassland energy exchange to heatwaves. Nat. Geosci. 3, 722–727 (2010).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Albergel, C. et al. Evaluation of remotely sensed and modelled soil moisture products using global ground-based in situ observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 118, 215–226 (2012).

Xia, Y. et al. Evaluation of multi-model simulated soil moisture in NLDAS-2. J. Hydrol. 512, 107–125 (2014).

Dorigo, W. A. et al. Evaluation of the ESA CCI soil moisture product using ground-based observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 162, 380–395 (2015).

Rodell, M. et al. The Global Land Data Assimilation System https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-85-3-381 (2004).

Miralles, D. G. et al. GLEAM4: global land evaporation and soil moisture dataset at 0.1 resolution from 1980 to near present. Sci. Data 12, 416 (2025).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Huffman, G. J. et al. Integrated multi-satellite retrievals for the global precipitation measurement (gpm) mission (imerg). In: Satellite Precipitation Measurement. 343–353 (Springer, 2020).

Harris, L. et al. GFDL SHiELD: a unified system for weather-to-seasonal prediction. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2020MS002223 (2020).

Zhou, L. et al. Bridging the gap between global weather prediction and global storm-resolving simulation: introducing the GFDL 6.5-km SHiELD. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 16, e2024MS004430 (2024).

Putman, W. M. & Lin, S.-J. Finite-volume transport on various cubed-sphere grids. J. Comput. Phys. 227, 55–78 (2007).

Lin, S.-J. A. “Vertically Lagrangian” finite-volume dynamical core for global models. Mon. Weather Rev. 132, 2293–2307 (2004).

Harris, L. M. & Lin, S.-J. A two-way nested global-regional dynamical core on the cubed-sphere grid. Mon. Weather Rev. 141, 283–306 (2013).

Chen, J.-H. et al. Advancements in hurricane prediction with NOAA’s next-generation forecast system. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 4495–4501 (2019).

Zhou, L. et al. Improving global weather prediction in GFDL SHiELD through an upgraded GFDL cloud microphysics scheme. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 14, e2021MS002971 (2022).

Zhou, L. & Harris, L. Integrated dynamics-physics coupling for weather to climate models: GFDL SHiELD with in-line microphysics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100519 (2022).

Chen, J.-H., Zhou, L., Magnusson, L., McTaggart-Cowan, R. & Köhler, M. Tropical cyclone forecasts in the DIMOSIC Project—medium-range forecast models with common initial conditions. Earth Space Sci. 10, e2023EA002821 (2023).

Ek, M. B. et al. Implementation of Noah land surface model advances in the National Centers for Environmental Prediction operational mesoscale Eta model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 8851 (2003.

Han, J. & Bretherton, C. S. TKE-based moist eddy-diffusivity mass-flux (EDMF) parameterization for vertical turbulent mixing. Weather Forecast. 34, 869–886 (2019).

Han, J. et al. Updates in the NCEP GFS Cumulus Convection Schemes With Scale And Aerosol Awareness. Weather Forecast. 32, 2005–2017 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Drs. Mingyu Park and Marc Prange are acknowledged for their comments and suggestions on an internal review of the manuscript. This report was prepared by Donghyuck Yoon under award NA18OAR4320123 and NA23OAR4320198 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, and the NOAA Research Global-Nest Initiative. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce. We acknowledge GFDL resources made available for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.H.Y.: Writing - review & editing, Writing - original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. J.H.C.: Writing - review & editing, Writing - original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Data curation. H.H.: Writing - review & editing, Writing - original draft, Conceptualization. K.L.F.: Writing - review & editing, Writing - original draft, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Chao He and ChenRui Diao. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoon, D., Chen, JH., Hsu, H. et al. Variations in land-atmosphere coupling during drought-heatwave events. Commun Earth Environ 7, 1 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02977-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02977-9