Abstract

Terrestrial vegetation, particularly forests and savannas, is vital for regulating water and carbon cycles; however, its resilience to climate change remains largely unexplored in India. Our study projects that global warming will increase the likelihood of a shift from forest to savanna-like conditions in major Indian forest regions by the late 21st century. Between 2001 and 2020, India’s tree cover grids declined from 30% to 28%, yet we observed non-climate-driven compositional shifts, with forests increasing from 7.2% to 8.6% and savannas from 9.2% to 11.7%. Nearly half of India’s landscape exhibits forest-savanna alternative states (unistable savanna), controlled by low (high) precipitation variability and seasonality. We found expansion of the savanna by the end of the century, driven by the model-projected increase in precipitation variability. However, targeted human interventions could mitigate these effects. Hence, strategic forest conservation policies will be crucial in safeguarding India’s forest ecosystems against climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Forest ecosystems play a crucial role in global climate regulation as they are a major terrestrial carbon sink1,2. However, the forest’s ability to withstand and recover from natural and anthropogenic perturbations — known as resilience — is increasingly threatened by global warming and human activities3,4,5,6. Projected increases in hot and dry extremes due to climate change can lead to tree mortality and forest loss7,8,9. Simultaneously, anthropogenic perturbations like deforestation increase the stress on forest ecosystems, further reducing their resilience10,11,12,13.

Tree cover resilience has previously been studied using a non-linear dynamical systems approach where the tree cover is considered a response to climate conditions like precipitation14,15. While tree cover increases linearly with precipitation initially, for higher precipitation values, two alternative tree cover states may emerge for the same annual precipitation16,17,18. In this regime, regions with dominant dense forests (closed canopies) or savanna (open tree canopies with herbaceous layer underneath) may exist for the same type of climate. The spatiotemporal variability and seasonality of precipitation are known to modulate the tree cover distribution19,20,21,22,23. Understanding this relationship is critical for regions with heterogeneous hydroclimates like India, where rainfall is highly seasonal with substantial spatial variability24,25. A recent study for India also showed rainfall seasonality as the strongest driver of the spatial distribution of tree cover, followed by edaphic and topographic drivers26.

India has a high spatial variability in its hydroclimate and, consequently, its biodiversity. According to the India State of Forest Report 2021, forests cover approximately 713,789 km2 (21.71%) of the country’s geographical area27. While Indian forests have faced substantial deforestation in the past century28, in the past few decades, the country has also implemented stricter forest conservation laws and reforestation programs like the National Afforestation Programme scheme, the National Mission for a Green India (GIM), and the Forest Fire Prevention & Management Scheme (FFPM), and afforestation under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). These programs have continuously increased the area under forest cover in the country for the last decade29. The government plans to increase the forest area to 33% by 2030 by increasing tree cover on around five million hectares of designated forest and non-forest regions30. While the forest landscape in India is evolving under anthropogenic interventions, India has also experienced noticeable changes in its hydroclimate in recent decades31,32,33. The spatio-temporal variability of monsoon rain is argued to change with global warming32,34,35, which may affect the productivity of Indian vegetation, including India’s tree cover26,36.

In this study, we investigate the dynamics of India’s tree cover over the last two decades (2001–2020), its relationship with regional hydroclimate, and its end-of-the-century projections (2071–2100) in the SSP585 climate scenario. We do this using the approach of ‘space for time substitution37, where we assume that the spatial pattern of tree cover at present reflects the temporal trajectory any location would follow if perturbations happened in the future (for example, climate gradually became wetter or drier). We delineate two dominant tree cover states in India — savanna and forests. We first discuss the observed changes in the tree cover distribution in India from 2001 to 2020 and then examine the predictability of tree cover in India using mean annual precipitation (MAP), its variability, and its seasonality. Further, we examine the bimodality of forest-savanna distribution in India using a dynamical system approach and then discuss its future trajectory in India for 2071–2100.

Observed changes in India’s tree cover

Figure 1 shows the percentage of change in the tree cover grids over India and changes in the tree cover class from 2001 to 2020. We use a Gaussian mixture model (GMM) fitted on the tree cover frequency distribution over India for the year 2020 to identify dominant tree cover classes in India, following ref. 15. The GMM over India reveals a cutoff of 40% tree cover as a separation between savanna and forest (Fig. S1). Thus, throughout this study, the terms ‘savanna’ (10–40% tree cover) and ‘forest’ (>40% tree cover) are used in reference to these specific statistical classifications based on tree cover percentage. Similar classification of tree cover was found by ref. 26 using hierarchical clustering for India, with a median tree cover for forest class at ~57% and for savanna as 40%. Fig. S2 shows the distribution of tree cover over India for the savanna and forest classes for 2001 and 2020. There is a substantial tree cover grid loss in 2020 compared to 2001 (Fig. 1a). However, this loss is mainly in central India and might be because of the expansion of human-influenced land areas.

Meanwhile, many grids with no tree cover (NTC) grids have been changed to tree cover grids (TC) for the high tree cover regions such as the Himalayas and central-east forests (Fig. 1a). Of the grids that have gained tree cover, 44.10% have tree cover higher than 10% (Fig. 1a). Figure 1b shows the grid-wise changes in the tree cover class in India. From 2001 to 2020, many low tree cover (<10%, LTC) grids changed to savanna (S), and many savanna grids converted to forest (F) grids (LTC > S, S > F, Fig. 1b), especially in India’s high tree cover regions. The reversal is less, i.e., forest grids changing to savanna/low tree cover or savanna grids changing to low tree cover grids. These results are summarized in Fig. 1c. Approximately 30% of land grids had non-zero tree cover in 2001, which reduced to 27% in 2020. The remaining ~70% of India’s total land grids were barren land, water bodies, grasslands, or human-influenced grids such as cropland and built-up areas (Fig. 1c), which increased to ~73% in 2020.

Interestingly, the percentage of savanna and forest grids increased in 2020 compared to 2001 in many parts of India (Fig. 1c). Overall, from 2001 to 2020, out of the total grids over India that were categorized into tree cover grids, LTC grids reduced from 13.49% to 7.26% in 2020, savanna (S) increased from 9.21% to 11.27%, and forest grids (F) increased from 7.18% to 8.60%. This indicates a compositional shift in the country’s tree cover from 2001 to 2020, especially in regions with sparse tree cover. However, the savanna, which includes central India, the Western Ghats, and the low-elevation Himalayas, and the moderately to very dense forests of the north-east, the southern part of the Western Ghats, and high high-elevation Himalayan Forest, has increased.

Tree cover as a function of hydroclimate (Observations and Projections)

Figure S3 shows the mean annual precipitation (MAP), its variability (shown as the coefficient of variation (COV), which is the ratio of the standard deviation of MAP to MAP), and seasonality (mean seasonality index, MSI) over India. While around 80% of India’s rain is received in the monsoon season (June to September), it is not spatially uniform, leading to a diverse hydroclimate across the country. The MAP varies from around 3000 mm/year in humid northeast and western coastal regions to less than 500 mm/year in arid north-western arid regions and peninsular non-coastal regions (Fig. S3). North India, the eastern coastal region, and central east India have an intermediate MAP (~1500 mm/year) and a subhumid climate. Precipitation variability and seasonality have a spatially asymmetric pattern to MAP, i.e., regions with high MAP generally have low COV and MSI and vice versa. Northeast and central-eastern regions have low variability and seasonality in rainfall because these regions receive rainfall even in non-monsoon months, forced by orography38. In addition, seasonality is also low in parts of north India and southern peninsular India, indicating the presence of rainfall in non-monsoon seasons (Fig. S3). These regions also receive rainfall from western disturbances and the northeastern monsoon39.

Studies have argued that tree cover in many regions of the world emerges in response to hydroclimate, especially the MAP14,15. Hence, we discuss the relationship between India’s tree cover and its hydroclimate. However, in addition to MAP, we also consider the role of COV and MSI to generate a holistic view of the hydroclimate. Figure S4 shows the variation of percentage tree cover with MAP for 2001 and 2020, with variability and seasonality. The upper panel in each Figure shows the distribution of MAP, along with the inter-quantile range. As expected, regions with low MAP have very low tree cover, which increases with MAP (Fig. S4). However, with increasing MAP, humidity, and seasonality, we still observe lower tree cover percentages, which are most apparent within the inter-quartile range of MAP (800–1700 mm/year), where most points are found. Ref. 26 examined a similar relationship between tree cover and climate over India using MAP and a metric for water deficit (a proxy for the combined effect of seasonality and variability of rainfall) and found a similar relationship between tree cover and MAP in India26. A spread in tree cover percentage in high rainfall regions indicates that multiple dominant tree cover modes can exist for the same climate condition.

While Fig. S4 shows that tree cover percentage varies non-linearly with climate, especially from intermediate to higher precipitation regimes, it doesn’t give much clarity about different regimes of tree cover that can exist for any MAP between 1000–2000 mm. To visualize the same, we show the frequency distribution of tree cover percentages for different MAP ranges in Fig. S5. We observe three major regimes of tree cover distributions. For low MAP values (0–1000 mm/year), there exist very low tree cover percentages (~0–10%), as was also apparent in Fig. S4. As MAP increases, a dominant tree cover of around 20% emerges, and at MAP of around 2000 mm/year, the dominant tree cover percentage moves to ~60%. These two dominant tree cover states are savannas and forests, also captured in Fig. S1. These results support the argument that in India, two distinct modes of tree cover distribution — savanna (sparse tree cover <40%), and forest (moderate and very dense forest, tree cover > 40%) — emerge in response to climate, consistent with reports of the Forest Survey of India (FSI)27 and previous literature15.

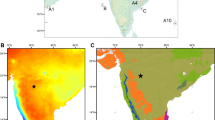

Given the above-discussed relationship between tree cover and MAP, the probability of states of tree cover can be estimated using hydroclimate. This estimated likelihood is often argued as a metric for vegetation resilience because it reflects the long-term stability of tree cover given hydroclimate14,15. If climatic controls strongly favor a given level of tree cover, then disturbances that temporarily reduce or increase tree cover (e.g., fire) are more likely to be followed by recovery to this equilibrium state once the disturbances are removed. In this sense, the likelihood represents the attractiveness and persistence of that state. We compute the likelihood of forest and savanna for the year 2001, using the generalized linear models (GLM), with MAP, COV, and MSI from 1971–2000 as predictors, and the results are shown in Fig. 2a, b. We tested the goodness of fit of this model using k-fold cross-validation. We found an average deviance R2 between 0.5–0.6, ordinary R2 of around 0.7–0.9, and log loss of around 0.2–0.3 for Savanna and Forests (see methods, Table S1, S2), which indicates a reasonably good fit. For forest and savanna, COV and MSI have a negative and positive coefficient in the model, respectively (Table S4), indicating an opposite effect of inter-annual precipitation variability on the two classes of tree cover. The humid regions like northeast and parts of southern India (high MAP, low COV, and low MSI) show dominant forest (Fig. 2c and S2a), and central-eastern regions, western ghats, and northern and peninsular India show dominant savanna (Fig. 2b and S2a). It is worth noting that parts of the western ghats, north, central-east, and northeast India have an equal likelihood of savanna and forest systems (Fig. 2), which, together with results from GMM, suggests that these two classes are alternative stable states. Next, using the model shown above, we diagnose the presence of non-climate-driven changes in tree cover from 2001 to 2020, as seen in Fig. 1. To do so, we compute the difference in 2020 tree cover predictions from the baseline 2001 model (discussed above, which uses 2001 tree cover and 1971–2000 hydroclimate) versus a new model fit onto 2020 tree cover observations using 1991–2020 MAP, COV, and MSI. The differences, shown in Fig. 2c, d, would indicate any change in tree cover explicitly caused by non-climate drivers. We find an increase in the likelihood of forests (~0.2 more than what was predicted from 2001 just by changing the hydroclimate) throughout the Himalayas, northeast India, east-central India, and parts of peninsular India. The same regions showed an increase in tree cover of more than 10% from 2001 to 2020 (NTC > TC, Fig. 1a), with many grids showing a change from savanna class to forest class (Fig. 1b). Central India shows an increase in the likelihood of the Savanna class (~0.2 more than what was predicted from 2001) for the same regions, which showed a low tree cover to savanna transition in observations (LTC > S, Fig. 1b). The changes in likelihoods indicate substantial non-climate-driven changes in tree cover from 2000 to 2020. These non-climate drivers can be fire and herbivory26, CO2 fertilization effect40,41,42, regrowth of natural forests, or the anthropogenic intervention-led changes to tree cover over India (Fig. 1 and S2). While ref. 26 hypothesized fire as a driver of tree cover, the lack of detectable fire events in Indian forests made it difficult to quantify its role robustly.

Predicted likelihoods for a Savanna and b Forest in 2001 using a generalized linear model (GLM) with tree cover observations of 2001 and climate variables (MAP, COV, MSI) from 1971–2000. The model fits the tree cover distribution reasonably well (tested using k-fold cross-validation, see tables S2 and S3). c and d show the non-climate-driven changes in tree cover from 2001 to 2020, estimated as the difference between predictions of 2020 using the model used in (a) and (b) by changing the hydro climate to 2020 and new models that fitted directly to 2020 tree cover observations using 1991–2020 MAP, COV, and MSI. Blue color indicates an increase in likelihood, red shows a decrease in likelihood.

While these results suggest positive effects of non-climate drivers, including anthropogenic interventions, they also raise the question of how these forest classes will look in the future due to climate change. To answer this, we estimate the likelihood of tree cover for future climate (2071–2100) using a multi-model mean of MAP, its COV, and MSI from CMIP6 model outputs for the SSP585 scenario. The results are shown in Fig. 3. The corresponding projected change in MAP (2071–2100 compared to 1971–2000), COV, and MSI is shown in Fig. S6. The likelihood of savanna tree cover (<40%) is projected to increase (while the likelihood of forest tree cover (>40%) is projected to decrease) in the parts of the western Himalaya, most of the eastern Himalayas, parts of central India, and the western ghats (Fig. 3). While MAP is projected to increase in these regions, the detrimental effects on forest cover are because the precipitation variability and seasonality will increase substantially, offsetting the effects of increased MAP (Fig. S6). There also exists an opposite response in some regions, specifically higher elevations of the western Himalayas, southern parts of the northeast region, and some parts of central India, where the likelihood of forests is projected to increase and that of savannas is projected to decrease due to climate change (Fig. 3).

Change in the likelihood of a savanna and b forest in the SSP585 scenario (2071–2100) compared to 2001 likelihoods shown in Fig. 2a, b. Blue color indicates an increase in likelihood, red shows a decrease in likelihood.

Our classification of tree cover does not distinguish between different phenological types within each tree cover class. For example, savannas in India are diverse and have been shown to contain three major tree cover types: Deciduous broadleaf savanna, Fine-leafed and spiny savanna, and Pine savanna36. Similarly, the low tree cover category, while indistinguishable from savanna based on tree cover alone18, contains diverse herbaceous vegetation like sparsely treed desert ecosystems, grasslands, etc. Multiple studies have shown the utility of each of these ecosystems in India’s biodiversity36,43,44,45. Studying the vegetation-climate relationship considering these diverse ecosystems within each broad category considered here is outside the scope of this study. Therefore, our estimates of changes in forest and savanna refer to changes in tree cover that cross the 40% statistical threshold inferred from the tree cover distribution.

While we use 40% tree cover as a threshold of transition between forest and savanna, studies in India and around the globe have argued for a range of 40–65% of tree cover as a threshold46,47. Hence, to test the robustness of our results, we also used 60% tree cover as a threshold of separation between forests and savanna to test the sensitivity of the conclusions. We find that the conclusions from GLM remain unchanged and are hence insensitive to the choice of cutoff between 40 and 60% (Figs. S7, S8).

Forest-savanna bimodality using potential landscape

Since some parts of the country have an equal likelihood of savanna and forest systems (Fig. 2), this points to the presence of alternative states of tree cover, where two states of tree cover are equally likely in response to climate. This is often analyzed using a dynamical system approach, which maps the probability density function of tree cover to a potential landscape (see methods). While a GLM-based approach discussed above presents a linear deterministic view of resilience, the dynamical systems approach can capture the non-linear response of tree cover to any perturbation. The landscape of 2020 and 2001 tree cover distribution in India using 1991–2020 and 1971–2000 MAP is shown in Fig. 4. Here, the presence of a basin in the landscape represents a stable state, and the system tends to remain in or return to these states when perturbed. For example, for a MAP of around 500, a tree cover of ~10% is most stable (Fig. 4). The presence of multiple basins in a landscape suggests the existence of alternative stable states. For example, in Fig. 4a, for a MAP of around 2000 mm, two stable tree covers exist, ~25% and ~60% (savanna and forest). The depth of a basin together represents the maximum perturbation (like a forest fire) the dynamical system (tree cover, in our case) can handle before it shifts to another basin. Hence, the deeper the basin, the more resilient the system is to small disturbances. In contrast, a system in a shallow basin is less resilient, as even a small perturbation could push it out of that state.

We found that the Indian tree cover has two basins for the entire range of MAP (Fig. 4). The minimum in the potential well corresponds to the maximum of the probability distribution of the tree cover for the corresponding MAP range. It indicates the stable tree cover in response to MAP. The maxima between any two basins represent the unstable equilibrium separating the two stable states. We show the stable and unstable regions separately in Fig. S9, only highlighting the center of the basin of attraction (black) and the ridge line of the unstable region (white) for clarity. The potential landscape for India’s tree cover distribution shows two stable tree cover basins, ~10–30% and ~60–80%, separated by an unstable equilibrium of 40–50%. This is also broadly consistent with our findings from GMM (Fig. S1) and the potential landscape of global tropical tree cover15. The relative depth of two basins for any MAP indicates the dominant tree cover percentage for that climate. At a lower precipitation range (<~1500 mm), the savanna is more resilient than the forest, as it has a wider and deeper basin (Fig. 4). However, with increased MAP (> ~ 1500 mm), both basins have almost equal depths, indicating alternative states where both savanna and forests are equally resilient. This contrasts with recent findings from ref. 48, which found no distinct separation between forest and savanna in Northeast India. However, the study used the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) as a proxy of tree cover to generate the state diagram, which measures vegetation greenness. It does not accurately reflect the dynamics of tree cover and can even misrepresent the extent of tree cover when the landscape is not flat or homogeneous49,50.

Projections of forest-savanna distributions for the end of the century

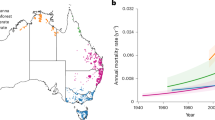

The landscape generated in Fig. 4 represents the tree cover response for the entire hydroclimate of India, which contains different variability and seasonality for the same MAP, as seen in Fig. S3. We observed from our previous analysis in Figs. 2, 3 that the variability of precipitation and its seasonality are critical for tree cover dynamics and may modulate the basins in the potential landscape. Figure S10a, b shows COV and MSI over India classified into four categories using 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles as thresholds. For further analysis, we divided the MAP of India into high and low variability (partitioned at the 50th percentile of COV, see methods) and high and low seasonality (partitioned at the 50th percentile of MSI, see methods) to examine their effects on the tree cover potential landscape. The results are shown in Fig. 5 as cross-sections of the potential landscapes at MAP values from 500 mm to 3000 mm with increments of 500 mm for 2020. We show results for two cases: grids having low variability with low seasonality and those with high variability and high seasonality. Interestingly, the tree cover has a different response to MAP for each case.

Potential of tree cover for different precipitation ranges for a low rainfall variability and b high rainfall variability with present climate conditions (1971–2000). c Distribution of MAP considering all grids of India (top row), only grids with low rainfall variability and seasonality (middle), and only grids with high rainfall variability and seasonality (bottom). Shaded regions indicate the distribution from the present MAP (1971–2000), and dashed lines indicate the distribution of future MAP (2071–2100). Vertical lines indicate the median values.

For regions with low rainfall variability and seasonality (Fig. 5a), the tree cover in India has two basins for the entire range of MAP, with dominant low (high) tree covers of ~20% (70%) for low (high) MAP. This comprises regions like north, northeast, eastern-central India, and many parts of peninsular India (Fig. S10a and b), which also contain major forests of India (Fig. S2). In addition, these are the regions where the observed increase in tree cover from 2001 to 2020 is maximum, with some regions showing an increase of more than 10% (Fig. 1, S2). For regions with high rainfall variability and seasonality (Fig. S10a, b), like western India, central India, and the northern part of peninsular India, the tree cover is unistable with a dominant low tree cover of around ~20% for the entire MAP range (Fig. 5b). While these regions are predominantly arid regions with very low tree cover, the high MAP corresponds to some parts of western peninsular India near the Western Ghats, which are also savanna-dominated (Fig. S2). In the potential landscape, the system can shift between states if subjected to a large enough disturbance, often referred to as a ‘tipping point.’ Hence, we may get a different response of tree cover bimodality in the future climate based on how variability and seasonality of rainfall change in any region, even if mean rainfall remains the same.

Hence, we show the corresponding MAP, COV, and MSI changes for the SSP585 scenario (2071–2100). Figure 5c shows the change in the distribution of MAP from 1971–2000 to 2071–2100 for all regions of India, regions with low variability and seasonality at present, and regions with high variability and seasonality at present. The vertical lines in the distributions mark the median values. The seasonality and variability of MAP will also change due to climate change. We show this in Fig. S10c, d as a change in COV and MSI from 1971–2000 to 2071–2100 with reference to the classified 1971–2000 COV and MSI in Fig. S10a, b using their 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles as thresholds. For regions with currently low variability and seasonality (using the 50th percentile as a threshold), the median MAP increases from ~1500 to ~2000 mm in 2071–2100 (Fig. 5c, middle row). This indicates that the tree cover can increase in these regions as the dominant tree cover type may shift from savanna to forest while staying bimodal (Fig. 5a). However, while at present, the variability and seasonality of MAP have an east-west asymmetry, with high values in the east and low values in the west, the climate models project an increase in COV all over India except for the northeast, the Himalayas, and some western parts of south India (Fig. S10). Together, high and very high COV values comprise around ~84% (an increase of ~34% from the 2001 classification) of the geographical area by the end of the century. Hence, the increase in tree cover due to the increase in MAP discussed above will only occur in regions where variability remains low. Since COV is projected to increase substantially throughout India, the future climate in India will likely become less conducive to stable, dense forests and more favorable to sparser, savanna-like vegetation.

This is consistent with our findings in Fig. 3, which showed a decrease in the likelihood of forests only for the western and eastern Himalayas and the western ghats. Similarly, seasonality is critical for tree cover. The seasonality is projected to have an east-west asymmetry with an increase in peninsular India (Fig. S10), suggesting that the region will be less conducive for forests and more favorable to savanna-like vegetation. The same regions were projected to have a reduction in tree cover using GLM (Fig. 3). Hence, variability and seasonality are more critical than MAP for tree cover dynamics in many parts of India. An increase in the variability and seasonality of precipitation in a warmer world can destabilize the forest state, potentially tipping the landscape from a bimodal forest-savanna system (Fig. 5a) toward a unistable state dominated by lower tree cover (Fig. 5b). It is important to note that these stressed conditions could also lead to other degraded vegetation states not fully captured by this model. However, as shown in Fig. 2, non-climatic drivers, like human interventions, can amplify or offset the adverse effects of climate change on forest ecosystems. Overall, global warming may make India’s hydroclimate less conducive to dense forests. However, the increase in the likelihood of forests from 2001 to 2020 due to non-climatic drivers indicates the potential of anthropogenic interventions to counter the detrimental effects of climate change. Attributing this increase in tree cover to different non-climate drivers can help build resilience of India’s tree cover in a warming world, which is left as a future extension of this study.

Conclusions

In this study, we examined the relationship between tree cover distribution in India and its regional hydroclimate to address two research gaps: (1) What is the effect of non-climatic drivers like anthropogenic interventions on tree cover distribution? (2) Based on observed tree cover distribution and tree cover-climate relationship, what will the end-of-century (2071–2100) tree-cover distribution look like in a climate change scenario in India?

Using the current tree cover distribution, we statistically delineate two dominant classes of tree cover in India: savanna (10–40% tree cover) and forest (>40% tree cover), and then estimate India’s tree cover change over the last twenty years (2001–2020). We found compositional shifts within the grids with tree cover – the low tree cover grids have decreased (13.49% > 7.26%), and the share of savanna and forest has increased. Next, we used a generalized linear model (GLM) to quantify the tree cover climate relationship, considering that tree cover occurs primarily in response to precipitation, its variability, and seasonality. We find that the likelihood of forests has increased in India throughout the Himalayas, parts of northeast India, east-central India, and the Western Ghats from 2001 to 2020. We argue that these changes are caused by non-climate drivers, including fire and herbivory, the CO2 fertilization effect, natural regrowth and recovery of existing forested areas, and anthropogenic interventions51. A detailed model-guided study is needed in the future to attribute these non-climate-driven tree-cover changes.

Next, we use a non-linear dynamical systems approach to show that most of the tree cover in India is primarily a bimodal forest-savanna system for any given climate condition. Previous studies found similar distributions in many regions of the world16,17. Next, we partition the generated potential landscape into areas with high and low MAP variability and seasonality and find that alternative states primarily exist in the regions with low MAP variability and seasonality. In contrast, the regions with high variability and seasonality showed more stable savanna landscapes. Hence, bimodality for Indian tree cover distribution is modulated not only by MAP but also strongly by its variability and seasonality.

CMIP6 climate model simulations for the SSP585 scenario suggest that by the end of the 21st century, the hydroclimate in many parts of India may become less favorable for maintaining dense forests. This suggests that the stable forest state may transition toward a unstable, savanna-like system. It is important to note that these stressed conditions could also lead to other degraded vegetation states not fully captured by this model. However, anthropogenic interventions may also help offset the adverse effects of climate change on forest ecosystems in India. Hence, forest conservation-related policies need to be planned considering the impacts of future climate and its relationship with India’s tree cover.

However, ecological responses have also been shown to exert an effect on tree cover distribution, for example, the CO2 fertilization effect may increase the likelihood of forests more than savanna52,53, and increased forest fires in a warmer world may promote more savanna than forests54,55. Savannas play a unique role in the global carbon cycle as they can have multiple cycles of vegetation growth within a year, accelerated by grazing, insects, and wildlife, aided by the storage of soil organic carbon36,56. Our study only considers the tree cover climate relationship and overlooks the savanna and forest-specific ecological responses, and socio-economic utility57,58. The forest-climate feedback is also set to change in response to changes in tree cover. Forest evapotranspiration is known to contribute moisture to terrestrial rainfall through moisture recycling59,60, which can feed back to the response of tree cover to climate change. Hence, forest-related policies in India should be guided by model-guided assessments which consider tree cover-climate relationship, ecological functions of forests and savanna, and their socio-economic benefits51.

Data and methods

Data

We used the MOD44B Version 6.1 Vegetation Continuous Fields (VCF) product61 for the annual percent tree cover at 500 meters (m) resolution. To account only for the natural vegetation cover, we removed all the grids that are not forests or savannas (e.g., barren lands, water bodies, and human-modified grids such as urban and built-up lands, cropland). For this, we use the MCD12Q1 International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) product for the land-cover class. The data provides global land cover maps at annual timesteps and 500-m spatial resolution for 2001-present. The MCD12Q1 product is created using the supervised classification of MODIS reflectance data62,63. For the present climate, we used precipitation from CRU-TS (Climatic Research Unit gridded Time Series) V4.07 on a 0.5° latitude by 0.5° longitude grid, which provides an interpolation of monthly climate anomalies derived from extensive networks of weather station observations from the period 1901–202264. Although global climatic patterns are reasonably well represented in a resolution of 0.5°, tree cover gradients may considerably vary along a 55 km distance (or 0.5°), particularly in heterogeneous landscapes like India, where map degradation through aggregation or resampling techniques could cause loss of tree cover information. Therefore, we kept the resolution of the tree cover dataset at 500 m and used all climate datasets at this resolution by using the same value of climate data for all 500 m tree cover grids within a 0.5° x 0.5° climate grid.

Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) Earth System Model (ESM) outputs were used to calculate the projected resilience and stability under the SSP585 scenario65. Table S3 shows the list of ESMs used in the study. All the model outputs were regridded to 0.5° x 0.5. Figure S11a compares the climatological precipitation of CRU and ESMs for 1971–2014 using historical simulations. The multi-model means (MMM) of the ESMs used in the study represent India’s average climatological precipitation well, with slight underestimation in the monsoon period and overestimation in the non-monsoon period. We also compare historical model runs and the CRU dataset using a Taylor diagram66 for 1971–2014 (Fig. S11b). Taylor’s diagram also shows a good correlation between the models and CRU in simulating the monthly precipitation. Overall, the multi-model ensemble means of precipitation from climate models considered in this study can reasonably reproduce India’s precipitation.

MAP, COV, and MSI calculation

MAP is calculated as the total precipitation in a year for each grid, averaging from 1971 to 2000 for the first period and 1991 to 2020 for the second period. The MAP variability is computed as the ratio of standard deviation to the mean of annual precipitation for both periods, the coefficient of variation (COV). MSI represents how rainfall is clustered in a few months over a year. The MSI is calculated as:

Where R is the total annual precipitation for a particular year, \({X}_{i}\) is the monthly precipitation for the month i. The mean seasonality index is calculated as the seasonality index averaged over n number of years67,68.

Regions with high and low variability and seasonality are classified based on the percentile of COV and MSI for the period 1971–2000. The very low, low, high, and very high variability/seasonality regions are classified as all the grids having the COV/MSI less than 25%, 25–50%, 50–75%, and >75% percentile, respectively. While calculating the stability landscape for low COV and low MSI, we consider all the grids that are classified as low and very low COV and MSI. Similarly, while calculating the stability landscape for high COV and high MSI, we consider all the grids that are classified as high and very high COV and MSI.

Tree-cover classification

Many studies have shown that three states of tree cover exist, i.e., low tree cover, savanna, and forests15,17,69,70. For example, ref. 15 showed using the expectation-maximization on a Gaussian mixture distribution that the separation between these three modes occurred at 5% and 60% tree cover levels. Using the same approach, we check the best fit for the GMM to compare different tree-cover states in India (Fig. S1). We identify the cutoff level of 10% and 40% thus defining the tree cover classes broadly as 1) Low tree cover (<10%), 2) Savanna (10–40%), and 3) Forest (<40%).

Studies have also pointed out bias in tree cover distribution generated using the MODIS VCF product71,72,73,74. However, the bias seems most prominent in very low tree cover regimes with high robustness of MODIS VFC data in regions with higher tree cover74. Despite its limitations, it is worth noting that MODIS VCF tree cover offers long-term data, which is critical when trying to understand terrestrial vegetation’s climate drivers. Consequently, it has been extensively used to study the resilience of tree cover across the globe59,60,70,75,76. The reliability of MODIS VCF-derived tree cover distribution for application over India is reinforced by recent analysis from ref. 26, which validated it using field-based datasets over India. The study validated the satellite-derived tree cover using field observations from ref. 77 at four different climate types using multiple species of trees and found consistent representation by MODIS VFC for savannas. In addition, we also compared the MODIS tree cover data with Landsat 8 TCC78 (tree canopy cover) data for the year 2015 (Fig. S12) over India, and it shows a reasonable agreement (correlation = 0.8), which supports the reliability of MODIS VCF tree cover over India.

Given the uncertainty around the low tree cover class and robustness of MODIS tree cover for savanna and forests, we exclude the low tree cover class (tree cover <10%) from this study and only consider savanna and forests for further analysis. This is consistent with previous studies, which have used only tree cover >10% from MODIS VCF for delineating tree cover classes over the Amazon rainforest76. Studies have also shown that a clear separation between low tree cover and savanna is difficult to delineate just by frequency distributions because of the linear response of tree cover to hydroclimate and its dependence on edaphic factors in this region18. However, our choice of removing low tree cover grids from the analysis does not affect our study conclusions because the prediction model (discussed below) was independently fit on each tree cover class.

Likelihood estimation of each tree cover state

The likelihood of tree cover can be estimated from the hydroclimate and is often argued as a measure of tree cover resilience. This study’s framework is based on ecological resilience, which is defined as the magnitude of disturbance that can be absorbed before a system transitions to a different state. In line with this concept, the relationship between tree cover and precipitation in many regions worldwide is argued to exhibit a threshold behavior10,79.

To estimate the likelihood of tree cover, we modeled the distribution of tree cover states as a function of climate variables (MAP, COV, and MSI) using the generalized linear models (GLM) with binomial distribution and the logit link function (\(f\left(\mu \right)\)) as:

The logit function maps z (tree cover) as a sigmoid function of \({x}_{1}\), \({x}_{2}\) and, \({x}_{3}\) (MAP, COV, and MSI, respectively). The sigmoid function is written as

The probability for each state is assigned according to this model, which gives the probability of existence (likelihood) and can be inferred as its resilience. This approach calculates the likelihoods independently for each vegetation type: forest and savanna. We test the goodness of fit for this model using k-fold cross-validation (k = 5). We compute the following metrics on each fold to test the goodness of fit and take their average across all five folds.

Deviance R2

It evaluates model fit by measuring the reduction in deviance (a measure of unexplained variation) from a null model to the fitted model. The Null Deviance is the deviance of a model that only includes the intercept.

Ordinary R2

Ordinary R2, also known as the coefficient of determination, is a standard goodness-of-fit metric in linear regression. It quantifies the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the independent variables, ranging from 0 to 1.

Where, \(S{S}_{{residual}}\) is the sum of squared residuals (unexplained variation), and \(S{S}_{{total}}\) is the total sum of squares (total variation around the mean).

Log loss

Log loss, also called cross-entropy loss or logistic loss, measures the performance of classification models that output probabilities, such as logistic regression used in this study. It penalizes predictions that deviate from actual labels, with greater penalties for confident but incorrect predictions. For binary classification, as in our case, the equation is:

where N is the number of samples, \({y}_{i}\) is the true binary label (0 or 1), and \({p}_{i}\) is the predicted probability of the positive class.

We found an average deviance R2 of around 0.5–0.6, ordinary R2 of around 0.7–0.9, and log_loss of around 0.2–0.3 for Savanna and Forests, which indicates a reasonably good fit. These metrics are shown in Tables S2, S3 for the savanna and the forests, respectively.

Construction of potential landscape

To construct the potential landscape from the tree cover and climate variables, we employ a recently developed approach that uses the Langevin equation (a stochastic differential equation (SDE) that describes the time evolution of a stochastic process) to model a dynamical system80. It provides a trajectory-based description of the system and can be written as:

where \(U\left(z\right)\) is called the potential function, z is the state variable, which can be any large-scale climate variable considered as a dynamical system (tree cover in our case), and \(\eta (t)\) is the stochastic term often considered as a Gaussian white noise or a Wiener process. If a system is governed by the equation above, then its corresponding Fokker-Planck equation, which describes the time evolution of a probability density function of the variable

has a solution that links the probability density function of the variable (p(z)) to a potential function (U(z))81.

Hence, the potential landscape can be constructed using tree cover distribution as follows:

Where \({p}_{d}\) is an empirically derived probability density function (PDF). We computed the empirical PDF of tree cover distribution for varying precipitation using satellite observations of tree cover and used Eq. (9) to calculate an approximate potential landscape by Gaussian smoothing. This potential landscape can then be used to infer the response of tree cover to changes in precipitation over time. The validity of using spatial PDF lies in the central assumption of ergodicity: under stationary stochastic processes, spatial ensemble averages equal temporal averages. Specifically, the current spatial distribution of tree cover across environmental gradients reflects the long-term temporal trajectory any single location would follow under similar perturbations, called ‘space-for-time substitution’37. As we are only interested in qualitative estimation of potential to study relative changes, we scale the potential to the noise level (\(U/{\sigma }^{2}\)). Following ref. 15, we estimated the probability density using Kernel density estimation, with a standard bandwidth of \(h=1.06s/{n}^{(\frac{1}{5})}\) (s = standard deviation of data, and n is the number of data points).

Data availability

All the data used in this study are properly cited and publicly available. MODIS tree cover data is available at https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-mod44b-006. MODIS land cover data is available at https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-mcd12q1-006. CRU dataset is available at https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/. CMIP6 data is available at https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/. The data to reproduce the main figures of this manuscript can be accessed from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30636614.v1.

References

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2021. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 1917–2005 (2022).

Bonan, G. B. Forests and Climate Change: Forcings, Feedbacks, and the Climate Benefits of Forests. https://www.science.org.

Xu, C. et al. Increasing impacts of extreme droughts on vegetation productivity under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 948–953 (2019).

Müller, L. M. & Bahn, M. ichael Drought legacies and ecosystem responses to subsequent drought. Glob. Chang Biol. 28, 5086–5103 (2022).

Smith, T., Traxl, D. & Boers, N. Empirical evidence for recent global shifts in vegetation resilience. Nat. Clim. Chang 12, 477–484 (2022).

Peterson, G., Allen, C. R. & Holling, C. S. Ecological Resilience, Biodiversity, and Scale. https://doi.org/10.1007/s100219900002

Allen, C. D. et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Ecol. Manag. 259, 660–684 (2010).

Choat, B. et al. Triggers of tree mortality under drought. Nature 558, 531–539 (2018).

McDowell, N. G. & Allen, C. D. Darcy’s law predicts widespread forest mortality under climate warming. Nat. Clim. Chang 5, 669–672 (2015).

Staal, A. et al. Feedback between drought and deforestation in the Amazon. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 044024 (2020).

Boysen, L. R. et al. Global climate response to idealized deforestation in CMIP6 models. Biogeosciences 17, 5615–5638 (2020).

Nobre, C. A., Sellers, P. J. & Shukla, J. Amazonian deforestation and regional climate change. J. Clim. 4, 957–988 (1991).

Li, Y. et al. Future increases in Amazonia water stress from CO2 physiology and deforestation. Nat. Water 1, 769–777 (2023).

Holmgren, M., Hirota, M., Van Nes, E. H. & Scheffer, M. Effects of interannual climate variability on tropical tree cover. Nat. Clim. Chang 3, 755–758 (2013).

Hirota, M., Holmgren, M., Van Nes, E. H. & Scheffer, M. Global resilience of tropical forest and savanna to critical transitions. Science (1979) 334, 232–235 (2011).

Staal, A. et al. Hysteresis of tropical forests in the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 11, 4978 (2020).

Staal, A., Dekker, S. C., Xu, C. & van Nes, E. H. Bistability, spatial interaction, and the distribution of tropical forests and savannas. Ecosystems 19, 1080–1091 (2016).

Sankaran, M. et al. Determinants of woody cover in African savannas. Nature 438, 846–849 (2005).

Gu, L., Pallardy, S. G., Hosman, K. P. & Sun, Y. Impacts of precipitation variability on plant species and community water stress in a temperate deciduous forest in the central US. Agric. Meteorol. 217, 120–136 (2016).

Giardina, F. et al. Tall Amazonian forests are less sensitive to precipitation variability. Nat. Geosci. 11, 405–409 (2018).

Xu, X. et al. Tree cover shows strong sensitivity to precipitation variability across the global tropics. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 27, 450–460 (2018).

Guo, Q. et al. Spatial variations in aboveground net primary productivity along a climate gradient in Eurasian temperate grassland: Effects of mean annual precipitation and its seasonal distribution. Glob. Chang Biol. 18, 3624–3631 (2012).

Suarez, M. L. & Kitzberger, T. Differential effects of climate variability on forest dynamics along a precipitation gradient in northern Patagonia. J. Ecol. 98, 1023–1034 (2010).

Li, J. & Wang, B. How predictable is the anomaly pattern of the Indian summer rainfall? Clim. Dyn. 46, 2847–2861 (2016).

Gadgil, S. The Indian monsoon and its variability. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 31, 429–467 (2003).

Gopalakrishna, T. et al. The distribution and drivers of tree cover in savannas and forests across India. Commun Earth Environ 5, 399 (2024).

FSI. India State of Forest Report 2021. https://fsi.nic.in/forest-report-2021-details (2021).

Sudhakar Reddy, C. et al. Quantification and monitoring of deforestation in India over eight decades (1930–2013). Biodivers. Conserv 25, 93–116 (2016).

PIB Delhi. National afforestation programmes to improve the forest cover. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1795073 (2022).

PIB Delhi. National afforestation programme. PIB Delhi. https://www.pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1596332 (2019).

Katzenberger, A., Schewe, J., Pongratz, J. & Levermann, A. Robust increase of Indian monsoon rainfall and its variability under future warming in CMIP6 models. Earth System Dyn. 12, 367–386 (2021).

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896 (2021).

Ghosh, S., Das, D., Kao, S.-C. & Ganguly, A. R. Lack of uniform trends but increasing spatial variability in observed Indian rainfall extremes. Nat. Clim. Chang 2, 86–91 (2012).

Annamalai, H., Hafner, J., Sooraj, K. P. & Pillai, P. Global warming shifts the monsoon circulation, drying South Asia. J. Clim. 26, 2701–2718 (2013).

Rajesh, P. V., Goswami, B. N., Choudhury, B. A. & Zahan, Y. Large Sensitivity of Simulated Indian Summer Monsoon Rainfall (ISMR) to Global Warming: Implications of ISMR Projections. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 126, e2020JD033511 (2021).

Ratnam, J., Tomlinson, K. W., Rasquinha, D. N. & Sankaran, M. Savannahs of Asia: Antiquity, biogeography, and an uncertain future. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 371, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0305 (2016).

Blois, J. L., Williams, J. W., Fitzpatrick, M. C., Jackson, S. T. & Ferrier, S. Space can substitute for time in predicting climate-change effects on biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 9374–9379 (2013).

Zahan, Y., Mahanta, R., Rajesh, P. V. & Goswami, B. N. Impact of climate change on North-East India (NEI) summer monsoon rainfall. Clim. Change 164, 2 (2021).

Rajeevan, M., Unnikrishnan, C. K., Bhate, J., Niranjan Kumar, K. & Sreekala, P. P. Northeast monsoon over India: Variability and prediction. Meteorol. Appl. 19, 226–236 (2012).

Pan, Y. et al. Contrasting responses of woody and grassland ecosystems to increased CO2 as water supply varies. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 315–323 (2022).

Norby, R. J. et al. Enhanced woody biomass production in a mature temperate forest under elevated CO2. Nat. Clim. Chang 14, 983–988 (2024).

Davis, E. C., Sohngen, B. & Lewis, D. J. The effect of carbon fertilization on naturally regenerated and planted US forests. Nat. Commun. 13, 5490 (2022).

Madhusudan, M. D. & Vanak, A. T. Mapping the distribution and extent of India’s semi-arid open natural ecosystems. J. Biogeogr. 50, 1377–1387 (2023).

Lahiri, S., Roy, A. & Fleischman, F. Grassland conservation and restoration in India: a governance crisis. Restor. Ecol. 31, https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13858 (2023).

Lahiri, S. & Reddy, S. India’s grasslands are not “wastelands”. Science (1979) 387, 726–727 (2025).

Pletcher, E., Staver, C. & Schwartz, N. B. The environmental drivers of tree cover and forest–savanna mosaics in Southeast Asia. Ecography 2022, e06280 (2022).

Staver, A. C., Archibald, S. & Levin, S. A. The global extent and determinants of savanna and forest as alternative biome states. Science (1979) 334, 230–232 (2011).

Sarania, B., Guttal, V. & Tamma, K. The absence of alternative stable states in the vegetation cover of northeastern India. R. Soc. Open Sci 9, 211778 (2022).

Matsushita, B., Yang, W., Chen, J., Onda, Y. & Qiu, G. Sensitivity of the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) to Topographic Effects: A Case Study in High-Density Cypress Forest. Sensors 7, 2636–2651 (2007).

Mizen, A. et al. The use of Enhanced Vegetation Index for assessing access to different types of green space in epidemiological studies. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 34, 753–760 (2024).

Di Sacco, A. et al. Ten golden rules for reforestation to optimize carbon sequestration, biodiversity recovery and livelihood benefits. Glob. Chang Biol. 27, 1328–1348 (2021).

Chaturvedi, R. K. et al. Impact of climate change on Indian forests: A dynamic vegetation modeling approach. Mitig. Adapt Strateg Glob. Chang 16, 119–142 (2011).

Kumar, D., Pfeiffer, M., Gaillard, C., Langan, L. & Scheiter, S. Climate change and elevated CO2 favor forest over savanna under different future scenarios in South Asia. Biogeosciences 18, 2957–2979 (2021).

Hirota, M., Nobre, C., Oyama, M. D. & Bustamante, M. M. C. The climatic sensitivity of the forest, savanna and forest-savanna transition in tropical South America. N. Phytol. 187, 707–719 (2010).

Balch, J. K. et al. Warming weakens the night-time barrier to global fire. Nature 602, 442–448 (2022).

Dobson, A. et al. Savannas are vital but overlooked carbon sinks. Science 375, 392 (2022).

Roy, A. & Fleischman, F. The evolution of forest restoration in India: The journey from precolonial to India’s 75th year of Independence. Land Degradation and Development 33, 1527–1540 (2022).

Coleman, E. A. et al. Limited effects of tree planting on forest canopy cover and rural livelihoods in Northern India. Nat. Sustain 4, 997–1004 (2021).

Staal, A. et al. Forest-rainfall cascades buffer against drought across the Amazon. Nat. Clim. Chang 8, 539–543 (2018).

Zemp, D. C. et al. Self-amplified Amazon forest loss due to vegetation-atmosphere feedbacks. Nat. Commun. 8, 14681 (2017).

DiMiceli, C., Sohlberg, R., & Townshend, J. MODIS/Terra Vegetation Continuous Fields Yearly L3 Global 250m SIN Grid V061 [Data set]. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center. Accessed 2024-08-19 (2022).

Friedl, M. A. et al. MODIS Collection 5 global land cover: Algorithm refinements and characterization of new datasets. Remote Sens Environ. 114, 168–182 (2010).

Friedl, M. A. et al. Global Land Cover Mapping from MODIS: Algorithms and Early Results. www.elsevier.com/locate/rse (2002).

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci. Data 7, 109 (2020).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Taylor, K. E. Summarizing multiple aspects of model performance in a single diagram. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 106, 7183–7192 (2001).

Walsh, R. P. D. & Lawler, D. M. Rainfall seasonality: description, spatial patterns and change through time. Weather 36, 201–208 (1981).

Rai, P. & Dimri, A. P. Changes in rainfall seasonality pattern over India. Meteorol. Appl. 27, e1823 (2020).

Aleman, J. C. & Staver, A. C. Spatial patterns in the global distributions of savanna and forest. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 27, 792–803 (2018).

Flores, B. M. et al. Critical transitions in the Amazon forest system. Nature 626, 555–564 (2024).

Gerard, F. et al. MODIS VCF should not be used to detect discontinuities in tree cover due to binning bias. A comment on Hanan et al. (2014) and Staver and Hansen (2015). Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 26, 854–859 (2017).

Adzhar, R. et al. MODIS Vegetation Continuous Fields tree cover needs calibrating in tropical savannas. Biogeosciences 19, 1377–1394 (2022).

Hanan, N. P., Tredennick, A. T., Prihodko, L., Bucini, G. & Dohn, J. Analysis of stable states in global savannas: Is the CART pulling the horse?. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 23, 259–263 (2014).

Staver, A. C. & Hansen, M. C. Analysis of stable states in global savannas: Is the CART pulling the horse? - a comment. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 24, 985–987 (2015).

Kelley, D. I. et al. Fire, environmental and anthropogenic controls on pantropical tree cover. Commun Earth Environ. 5, 714 (2024).

Ciemer, C. et al. Higher resilience to climatic disturbances in tropical vegetation exposed to more variable rainfall. Nat. Geosci. 12, 174–179 (2019).

Nerlekar, A. N. et al. Exponential rise in the discovery of endemic plants underscores the need to conserve the Indian savannas. Biotropica 54, 405–417 (2022).

Sexton, J. O. et al. Global, 30-m resolution continuous fields of tree cover: Landsat-based rescaling of MODIS vegetation continuous fields with lidar-based estimates of error. Int J. Digit Earth 6, 427–448 (2013).

Flores, B. M. & Staal, A. Feedback in tropical forests of the Anthropocene. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 5041–5061 (2022).

Livina, V. N., Kwasniok, F. & Lenton, T. M. Climate of the Past Potential Analysis Reveals Changing Number of Climate States during the Last 60 Kyr. Clim. Past 6 www.clim-past.net/6/77/2010/ (2010).

Gardiner, C. W. Handbook of stochastic methods for physics, chemistry and the natural sciences. (Springer, Berlin, 2003).

Acknowledgements

The work is financially supported by the Department of Science and Technology Swarnajayanti Fellowship Scheme through project no. DST/ SJF/ E&ASA-01/2018-19; SB/SJF/2019-20/11, and Strategic Programs, Large Initiatives and Coordinated Action Enabler (SPLICE), and Climate Change Program through project no. DST/CCP/CoE/140/2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.D., T.C., and S.G. conceived the idea and designed the problem. N.D. developed the codes and performed the analysis. All the authors analyzed the results. N.D. and T.C. wrote the manuscript. S.G. reviewed and edited the manuscript. S.G. acquired the funding to support the analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Trisha Gopalakrishna and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jinfeng Chang, Aliénor Lavergne, and Mengjie Wang. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dubey, N., Chauhan, T.A. & Ghosh, S. Forest-savanna stability in India under human interventions and changing climate. Commun Earth Environ 7, 58 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03076-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03076-5