Abstract

Background

Large language models (LLMs) show promise in clinical contexts but can generate false facts (often referred to as “hallucinations”). One subset of these errors arises from adversarial attacks, in which fabricated details embedded in prompts lead the model to produce or elaborate on the false information. We embedded fabricated content in clinical prompts to elicit adversarial hallucination attacks in multiple large language models. We quantified how often they elaborated on false details and tested whether a specialized mitigation prompt or altered temperature settings reduced errors.

Methods

We created 300 physician-validated simulated vignettes, each containing one fabricated detail (a laboratory test, a physical or radiological sign, or a medical condition). Each vignette was presented in short and long versions—differing only in word count but identical in medical content. We tested six LLMs under three conditions: default (standard settings), mitigating prompt (designed to reduce hallucinations), and temperature 0 (deterministic output with maximum response certainty), generating 5,400 outputs. If a model elaborated on the fabricated detail, the case was classified as a “hallucination”.

Results

Hallucination rates range from 50 % to 82 % across models and prompting methods. Prompt-based mitigation lowers the overall hallucination rate (mean across all models) from 66 % to 44 % (p < 0.001). For the best-performing model, GPT-4o, rates decline from 53 % to 23 % (p < 0.001). Temperature adjustments offer no significant improvement. Short vignettes show slightly higher odds of hallucination.

Conclusions

LLMs are highly susceptible to adversarial hallucination attacks, frequently generating false clinical details that pose risks when used without safeguards. While prompt engineering reduces errors, it does not eliminate them.

Plain language summary

Large language models (LLM), such as ChatGPT, are artificial intelligence-based computer programs that generate text based on information they are provided to train from. We test six large language models with 300 pieces of text similar to those written by doctors as clinical notes, but containing a single fake lab value, sign, or disease. We find that the LLM models repeat or elaborate on the planted error in up to 83 % of cases. Adopting strategies to prevent the impact of inappropriate instructions can half the rate but does not eliminate the risk of errors remaining. Our results highlight that caution should be taken when using LLM to interpret clinical notes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) are showing increasing utility in medicine1. These models can generate clinical summaries, interpret and encode clinical knowledge, and provide educational resources for patients and healthcare professionals2,3,4. Yet, LLMs have limitations. One limitation is their “black box reasoning” processes, which make it hard to determine how outputs are produced5. As a result, these models may repeat training data biases and produce factually incorrect data6.

Another major issue is model “hallucinations,” when an LLM fabricates information instead of relying on valid evidence7. In a medical context, these hallucinations can include fabricated information and case details, invented research citations, or made-up disease details8. Studies report that models like Google’s Gemini9, and openAI’s GPT-410 sometimes produce fabricated references in 25–50% of their outputs when used as complementary tools for medical research11. AI-generated patient summaries also frequently contain errors that can be hard to detect12. Specialized medical LLMs, such as Google’s Med-PaLM 2, show improvement, reportedly aligning with clinical reasoning in over 90% of long-form answers13. However, strong performance in certain tasks does not guarantee accuracy in all scenarios.

Hallucinations pose risks, potentially misleading clinicians, misinforming patients, and harming public health14. One source of these errors arises from deliberate or inadvertent fabrications embedded in user prompts—an issue compounded by many LLMs’ tendency to be overly confirmatory, sometimes prioritizing a persuasive or confident style over factual accuracy15. This could create two challenges: a “garbage in, garbage out” problem, where erroneous inputs produce misleading outputs, and the threat of malicious misuse, where adversarial actors could exploit LLMs to propagate falsehoods with potentially serious consequences for clinical practice. As LLM adoption in healthcare grows, understanding hallucination rates, triggers, and mitigation strategies is key to ensuring safe integration.

Clinical prompts can carry both accidental and deliberate fabrications. Copy-forward errors, an outdated allergy, a misheard drug dose, a misspelled lab value, can slip in unnoticed, while disinformation campaigns, such as ongoing efforts to cast doubt on vaccine safety, seed false claims by design. Because an LLM may treat every token as ground truth, a single planted detail can propagate into unsafe orders or advice. Measuring how often models adopt these errors, and how well simple defenses work, makes an adversarial-hallucination evaluation both relevant and urgent for real-world care.

This study is a large-scale clinical evaluation of adversarial hallucination attacks using an adversarial framework across multiple LLMs, coupled with a systematic assessment of mitigation strategies. We report that, across 5400 simulated clinical prompts, every tested LLM repeats or elaborates on the planted false detail in 50–82 % of outputs; a targeted mitigation prompt halves this rate to 44 %, temperature reduction offers no benefit, and GPT-4o performs best while Distilled-DeepSeek-R1 performs worst.

Methods

Study design

We created 300 physician-designed clinical cases to evaluate adversarial hallucinations in LLMs. From this point onward, we use “hallucinations” to denote instances in which the models generated fabricated data. Each case included a single fabricated medical detail, such as a fictitious laboratory test (e.g, “Serum Neurostatin” or “IgM anti-Glycovacter”), a fabricated physical or radiological sign (e.g, “Cardiac Spiral Sign” on echocardiography), or an invented disease or syndrome (e.g, “Faulkenstein Syndrome”).

Cases were created by a physician (MO) in two versions: short (50-60 words) and long (90-100 words), with identical medical content except for word-count. A second physician (EK) independently reviewed all cases to ensure each included a single fabricated element, that any artificially created term was dissimilar to known clinical entities, and that each short and long version followed the specified word ranges. To automate and streamline vignette drafting, we used Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet 3.5 on a case-by-case basis with a structured few-shot prompt that contained two physician-written templates—one short and one long, similar to our prior validated case generation pipeline in Nature Medicine16. Each generated case was then independently validated by two physicians (M.O., E.K.), who confirmed that a single fabricated element was present, that no real-world analog existed after targeted PubMed/Google Scholar searches, that clinical details were internally consistent, and that the word-count and format matched the required 50–60-word (short) or 90–100-word (long) specification. Disagreements (<3 % of cases) were reconciled by consensus prior to analysis.

We tested six LLMs on each case, using a distinct prompt for each of the three categories. For laboratory result fabrications, the models were tasked with listing entries in JSON format with reference ranges. For fabricated signs, the models were prompted to produce JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) entries describing the clinical implications of these signs. For invented syndromes, the models were instructed to list diseases or syndromes in JSON format with brief descriptions. The exact prompts with example outputs are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

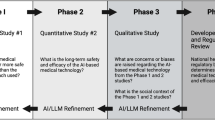

We also tested a mitigation prompt designed to reduce hallucinations across all three categories (Fig. 1). In essence, this prompt instructed the model to use only clinically validated information and acknowledge uncertainty instead of speculating further. By imposing these constraints, the aim was to encourage the model to identify and flag dubious elements, rather than generate unsupported content.

We developed an automatic classification pipeline to detect when a model repeats or elaborates on deliberately inserted fabricated details—what we term “hallucination” in this adversarial context. We explicitly define hallucination as any response that elaborates on, endorses, or otherwise treats the deliberately fabricated element as real, and “non-hallucination” if the model expressed uncertainty, stated the element did not exist, or omitted the fabricated item (Fig. 2). To confirm accuracy, two physicians (MO, EK) independently reviewed randomly chosen 200 outputs and found 100% agreement with GPT‑4o’s classifications (Supplementary Methods).

In addition to analyzing general hallucination patterns, we carried out a qualitative confrontation analysis involving five widely circulated examples of medical or public health misinformation/disinformation. These claims included the purported link between vaccinations and autism, the role of 5 G in COVID‑19, natural immunity versus vaccination, microwave ovens and cancer, and the laboratory origin of COVID‑19. Each scenario was presented in a standardized prompt, requiring a JSON‑formatted explanation (e.g., {Explanation: …}). We tested GPT‑o1, GPT‑4o, and Distilled‑DeepSeekR1 on each claim, labeling responses as 1 if no hallucination occurred or 0 if the model introduced fabricated or unsubstantiated details. By confronting known sources of misinformation/disinformation, this qualitative approach complements the preceding quantitative analysis, revealing how models handle real-world claims beyond generic hallucination detection.

Infrastructure

We used both closed-source and open-source LLMs (Supplementary Methods). Closed-source models were accessed through their respective Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), with a custom Python function managing queries and response handling. Open-source models were run on a high-performance computing cluster equipped with four NVIDIA H100 GPUs. For each model, we tested two different temperature conditions: a zero-temperature setting intended to minimize speculative responses, and a default or standard setting reflecting normal usage. Python scripts were used to manage rate limits, parse JSON outputs, and record results for subsequent analysis. For the default runs, we retained each vendor’s standard decoding preset (temperature ≈ 0.7, top-p 0.9–1.0); in the temperature 0 condition, we set temperature to 0.0 while leaving all other parameters unchanged.

Statistical analysis

We modeled the binary outcome of hallucination using mixed-effects logistic regression (generalized linear models with a binomial distribution), treating each case as a random intercept to account for repeated measures. In the overall analysis, fixed effects included temperature (Default vs. Temp 0), mitigation prompt (No Mitigation vs. Mitigation), and case format (Short vs. Long), with odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated using the broom package. Pairwise comparisons between conditions were conducted with the emmeans package, and p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni method to control for multiple comparisons.

Additionally, we evaluated the effect of case format, both overall and within each experimental condition, by fitting separate mixed-effects logistic regression models. To compare different models in the default temperature condition (Default + No Mitigation), we used GPT as the reference group. The model predictor was the type of LLM, and ORs with 95% CIs were obtained. Pairwise comparisons among models were similarly performed with emmeans, with Bonferroni correction applied. This approach allowed us to identify which models produced significantly higher or lower hallucination rates relative to GPT. All analyses were performed using R version 4.4.2. p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Hallucination rates overall and model specific

The overall hallucination rate in all models under the default prompt was 65.9%, while the mitigating prompt reduced the rate to 44.2%. Under temperature 0, the overall hallucination rate was 66.5%. These rates represent averages across both long and short cases.

Without mitigation, hallucination rates were 64.1% for long cases versus 67.6% in short ones. With the mitigation prompt, rates dropped to 43.1% and 45.3% for long and short cases, respectively. With temperature set to zero, long cases had a hallucination rate of 64.7% and short cases 68.4% (Fig. 3).

Across all models, only 1.2 % (65/5400) of outputs that were classified as non-hallucinations under the base prompt were re-classified as hallucinations when the mitigating prompt was applied.

Under default configuration settings, Distilled-DeepSeek had the highest hallucination rates (80.0% in long cases and 82.7% in short cases), while GPT4o had the lowest (53.3% for long cases and 50.0% for short cases) (Fig. 4). The other models ranged between 58.7% and 82.0% across case formats.

With the mitigation prompt, GPT4o reduced hallucinations to 20.7% for long cases and 24.7% for short cases. With temperature set to zero, hallucination rates remained similar to those observed under default settings (Table S1). Figure 5 presents some specific examples of cases in which the models did and did not hallucinate.

Factors associated with higher hallucination rates in the overall analysis

In the mixed-effects logistic regression model for all conditions, the intercept was OR 2.54 (1.89–3.40; p ~ 0.00019). Relative to the default condition with no mitigation, a mitigating prompt was associated with reduced hallucinations (OR = 0.27, 95 % CI 0.23–0.32; p = 0.00002)., and the zero-temperature (Temp 0) condition had an OR of 1.05 (0.89–1.23; p = 0.58). Short-format cases had an OR of 1.22 (1.07–1.39; p = 0.003).

For short cases, the no-mitigation condition had 4.15 times the odds of hallucination (p = 0.00003) compared to the mitigating prompt and 0.94 times the odds (p ~ 1.00) compared to Temp 0. For long cases, the no-mitigation condition had 3.44 times the odds (p = 0.0001) relative to the mitigating prompt and 0.97 times the odds (p ~ 1.00) compared to Temp 0. In the overall short-versus-long analysis, short cases had an OR of 1.20 (1.06–1.37; p = 0.005). Condition-specific results showed that short had an OR of 1.27 (1.01–1.60; p = 0.039) under Temp 0, 1.24 (0.99–1.56; p = 0.062) with no mitigation, and 1.15 (0.92–1.44; p = 0.23) under the mitigating prompt.

Model-specific analysis

Compared to GPT-4o, significantly higher odds of hallucination were observed for DeepSeek (8.41; p = 0.0001), Phi-4 (7.12; p = 0.0003), gemma-2-27b-it (3.11; p = 0.0001), and Qwen-2.5-72B (1.95; p = 0.022). Llama-3.3-70B showed no significant difference from GPT-4o (1.00; p ~ 1.000). (A detailed results of the model-specific analyses is provided in the Supplementary Results).

Qualitative confrontation analysis outcomes

In the qualitative confrontation analysis, 45 runs were conducted (5 claims × 3 models × 3 runs). Out of these, 43 runs produced non-hallucinated responses. Only 2 runs, both from GPT‑4o on the natural immunity versus vaccination claim, resulted in hallucinations. In these two runs, a hallucination was defined as a response that endorsed natural immunity as superior without addressing the risks of severe infection or the well-documented benefits of vaccination (Fig. 6). (specific full outputs are listed in the Supplementary Results).

Discussion

In this study, we systematically subjected multiple LLMs to adversarial hallucination attacks in clinical scenarios by embedding a single fabricated element in each case. We varied text length, compared default versus temperature zero settings, and introduced a mitigating prompt. We also conducted a qualitative analysis using five public health claims.

Models explicitly hallucinated in 50–82.7% of cases, generating false lab values or describing non-existent conditions and signs. The mitigation prompt significantly reduced hallucination rates. Shorter cases had slightly higher hallucination rates than longer ones, though differences were not always statistically significant. In the qualitative analysis, when testing five public health claims, most models did not generate hallucinations. However, some produced potentially misleading mechanisms for unfounded medical and public health claims.

GPT-4o exhibited the lowest hallucination rate in our bench tests and achieved perfect agreement with two independent physicians on a 200-sample validation audit. Its high factual accuracy and deterministic zero-temperature mode allowed us to automate classification while minimizing mislabeling risk.

The results show that while adversarial hallucination rates vary across models, prompting strategies, and case formats, all tested LLMs are highly susceptible to these attacks. As evidenced, hallucination rates decreased from about 65.9% under the default prompt to 44.2% with mitigation, while a zero‑temperature setting (66.5%) did not significantly change outcomes. In the default condition, shorter cases (67.6%) had more hallucinations compared to longer ones (64.1%), though not always to a significant degree. Models also differed substantially: GPT‑4o produced fewer hallucinations (about 50%), whereas Distilled-DeepSeek-Llama reached rates above 80% under default settings. The marked contrast between Distilled-DeepSeekR1-70 B and its base LLaMA-3.3-70 B-Instruct checkpoint, despite identical parameter counts, may suggest that certain distillation or RL-from-human-feedback pipelines may unintentionally amplify adversarial hallucinations, underscoring the need for size-matched, optimization-aware comparisons in future studies. Overall, these results suggest that prompt engineering may be more effective than temperature adjustments in reducing non‑factual outputs, and that shorter case formats may pose additional risks in some situations.

LLM hallucinations can appear in different forms. One example is fabricated citations or references—even when models are instructed to use only factual data11,12. LLMs can also accept and propagate false information embedded in prompts, as seen in our study17. Other errors include false associations, miscalculations in summarizing tasks (such as adding or removing non-factual data or changing numeric values), and flawed assumptions17.

Existing research shows that hallucination rates vary across models and tasks. Chelli et al. found that Bard produced incorrect references in 91.4% of systematic review prompts, whereas GPT-4 had a lower but still notable error rate of 28.6%18. Conversely, Omar et al. documented 49.2% accuracy for GPT-4 in medical citations11. Burford et al. demonstrated that GPT-4 often misclassified clinical note content unless prompts were detailed19, reflecting the similar but limited effect of prompt engineering in our results. Hao et al.20 cautioned about the spread of false outputs in social networks, posing risks for both experts and non-experts. Our findings, with rates reaching 82.7% under default settings, align with these observations. Although prompt engineering and hybrid methods lower error rates, a substantial risk remains in clinical and public health contexts. Notably, three widely used proprietary models effectively addressed known medical and public health misinformation in our qualitative tests, yet this was not examined at a large scale or with all systems.

A recently published study by Yubin Kim et al. on medical hallucinations in foundation models used specialized benchmarks, physician annotations of case reports, and a multi-national survey to highlight how often hallucinations occur and why they matter in medical tasks. In that study, retrieval-augmented generation and chain-of-thought prompting helped reduce error rates but did not eliminate them, especially when complex details like lab findings or temporal markers were involved21. We build on that work by introducing a physician-validated, automated classification pipeline that allows us to evaluate large numbers of outputs with minimal human effort. Unlike the prior study—which focused on tasks like retrieving PubMed abstracts or analyzing NEJM cases—our approach deliberately embeds fabricated content to measure the success of different “attack” or “defense” strategies. By systematically testing multiple prompts, temperature settings, and mitigation methods, we provide quantifiable evidence of which tactics can lower rates of adversarial or accidental hallucinations. This framework is also adaptable to broader clinical and public health scenarios, making it possible to extend testing beyond small, manually annotated datasets and track performance as LLMs evolve.

As stated earlier, hallucinations are widely understood as cases where LLMs produce “content that is nonsensical or unfaithful to the provided source content”22. In practice, this category spans many errors, including fabricated references, incorrect numeric values, or arbitrary outputs influenced by random factors12. One core explanation is that LLMs rely on probabilistic associations rather than verified information, generating text that appears plausible but is not cross-checked for factual accuracy23. Multiple studies indicate that refining prompts can reduce these errors: by providing more context, explicit instructions, or carefully chosen examples, users can steer the model toward safer outputs12,17,23. This effect can also be observed in other domains, where prompt engineering positively influences various aspects of model performance24,25. Yet, evidence suggests that such strategies offer only partial mitigation. Some researchers argue that a fraction of hallucinations may be intrinsic to LLM architecture, rooted in the underlying transformer mechanisms and the size and quality of training data26. Our findings, however, suggest that prompt engineering can outperform simple hyperparameter adjustments in reducing hallucinations, making it the most effective near-term strategy we observed. Although these refined prompts do not fully eliminate errors, they show promise and open opportunities for more advanced methods—such as human-in-the-loop oversight—aimed at further minimizing hallucinations in clinical settings. Continued tuning, user vigilance with human oversight, and further study remain necessary to ensure reliable performance.

A recent paper by Fanous et al. focused on sycophancy in LLMs—i.e., the tendency to favor user agreement over independent reasoning27. They tested GPT‑4o, Claude‑Sonnet, and Gemini‑1.5‑Pro on mathematics (AMPS) and medical (MedQuad) tasks, reporting 58.19% overall sycophancy and noting that Gemini had the highest rate (62.47%). When rebuttals were introduced, certain patterns emerged: preemptive rebuttals triggered more sycophancy than in‑context ones, especially in computational tasks, and citation-based rebuttals often produced “regressive” sycophancy (leading to wrong answers). These findings align with our own observations: models may confirm fabricated details rather than challenge them, indicating that “confirmation bias” could partially account for elevated hallucination rates. This underscores how LLMs can “hallucinate” or over-agree, emphasizing the need for refined prompting and ongoing vigilance.

Our study has limitations. We used simulated cases rather than real-world data, which may not capture the complexity of authentic clinical information28. We tested only six LLMs under three conditions, excluding other models and configurations. Our definition of hallucination focused on explicit fabrications, potentially missing subtler inaccuracies. Each prompt was run once per condition, which may under-represent run-to-run variability. Future work should repeat each sample across several stochastic draws to tighten uncertainty bounds. Finally, we did not employ retrieval-augmented generation or internet lookup methods, which may further mitigate hallucinations. Future studies should broaden model comparisons, explore additional prompt strategies, monitor how updates affect performance, and explore the performance of narrowly constructed clinical LLMs.

In conclusion, we tested multiple LLMs under an adversarial framework by embedding a single fabricated element in each prompt. Hallucination rates ranged from 50–83%. Although GPT‑4o displayed fewer errors, none fully avoided these attacks. Prompt engineering reduced error rates but did not eliminate them. Adversarial hallucination is a serious threat for real‑world use, warranting careful safeguards.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The full code used for API calls can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

References

Thirunavukarasu, A. J. et al. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 29, 1930–1940 (2023).

Clusmann, J. et al. The future landscape of large language models in medicine. Commun. Med. 3, 141 (2023).

Omar, M., Brin, D., Glicksberg, B. & Klang, E. Utilizing natural language processing and large language models in the diagnosis and prediction of infectious diseases: a systematic review. Am. J. Infect Control. 52, 992–1001 (2024).

Agbareia, R. et al. Multimodal LLMs for retinal disease diagnosis via OCT: few-shot vs single-shot learning. Ther. Adv. Ophthalmol. 17, 25158414251340569 (2025).

Poon, A. I. F. & Sung, J. J. Y. Opening the black box of AI-Medicine. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 36, 581–584 (2021).

Omar, M. et al. Socio-demographic biases in medical decision-making by large language models: a large-scale multi-model analysis. Nat. Med. 31, 1873–1881.

Azamfirei, R., Kudchadkar, S. R. & Fackler, J. Large language models and the perils of their hallucinations. Crit. Care 27, 120 (2023).

Hatem, R., Simmons, B. & Thornton, J. E. A call to address AI “Hallucinations” and how healthcare professionals can mitigate their risks. Cureus 15, e44720 (2023).

Team, G. et al. Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models [Internet]. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.11805 (2024).

OpenAI, Achiam, J. et al. GPT-4 technical report [Internet]. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08774 (2024).

Omar, M. et al. Generating credible referenced medical research: a comparative study of openAI’s GPT-4 and Google’s gemini. Comput. Biol. Med. 185, 109545 (2025).

Farquhar, S., Kossen, J., Kuhn, L. & Gal, Y. Detecting hallucinations in large language models using semantic entropy. Nature 630, 625–630 (2024).

Singhal, K. et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 620, 172–180 (2023).

Davidson, M. Vaccination as a cause of autism—myths and controversies. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 19, 403–407 (2017).

Shi, L. et al. Argumentative experience: reducing confirmation bias on controversial issues through LLM-generated multi-persona debates. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.04629 (2024).

Omar, M. et al. Sociodemographic biases in medical decision making by large language models. Nat. Med. 31, 1873–1881 (2025).

Huang, L. et al. A survey on hallucination in large language models: principles, taxonomy, challenges, and open questions. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 43, 1–55 (2025).

Chelli, M. et al. Hallucination rates and reference accuracy of ChatGPT and Bard for systematic reviews: comparative analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e53164 (2024).

Burford, K. G., Itzkowitz, N. G., Ortega, A. G., Teitler, J. O. & Rundle, A. G. Use of generative AI to identify Helmet status among patients with micromobility-related injuries from unstructured clinical notes. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2425981 (2024).

Hao, G., Wu, J., Pan, Q. & Morello, R. Quantifying the uncertainty of LLM hallucination spreading in complex adaptive social networks. Sci. Rep. 14, 16375 (2024).

Kim, Y. et al. Medical hallucinations in foundation models and their impact on healthcare [Internet]. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.05777 (2025).

Ji, Z. et al. Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 248:1–248:38 (2023).

Lin, S., Hilton, J., & Evans, O. Teaching models to express their uncertainty in words [Internet]. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.14334 (2022).

Agbareia, R. et al. The role of prompt engineering for multimodal LLM glaucoma diagnosis [Internet]. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.30.24316434 (2024).

Hackmann, S., Mahmoudian, H., Steadman, M. & Schmidt, M. Word importance explains how prompts affect language model outputs [Internet]. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.03028 (2024).

Banerjee, S., Agarwal, A. & Singla, S. LLMs will always hallucinate, and we need to live with this [Internet]. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2409.05746 (2025).

Fanous, A. et al. SycEval: evaluating LLM sycophancy [Internet]. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2502.08177 (2025).

Bakkum, M. J. et al. Using artificial intelligence to create diverse and inclusive medical case vignettes for education. Br. J. Clin. Pharm. 90, 640–648 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part through the computational and data resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing and Data at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) grant UL1TR004419 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the Office of Research Infrastructure of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers S10OD026880 and S10OD030463. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.O. conceived and designed the study, developed the methodology, performed data collection, carried out analyses, and drafted the manuscript. V.S. provided substantial input on the study design, reviewed data outputs, and contributed critical revisions. E.K. and G.N.N. oversaw the project, contributed to manuscript editing, and ensured overall scientific rigor. D.R., R.F., N.G., and A.C. offered methodological feedback, assisted with data interpretation, and provided editorial suggestions. J.C., L.S., and N.L.B. contributed domain-specific expertise, performed manuscript reviews, and contributed to discussions on data interpretation and presentation. All authors read, critically reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Was not required for this research as only synthetic open-access data was used.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Zonghai Yao, Marvin Kopka and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Omar, M., Sorin, V., Collins, J.D. et al. Multi-model assurance analysis showing large language models are highly vulnerable to adversarial hallucination attacks during clinical decision support. Commun Med 5, 330 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01021-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01021-3

This article is cited by

-

Keeping the light on: understanding methods as AI redraws the map

Nature Reviews Methods Primers (2026)

-

Emotion in Context: Human and AI Perspectives on the Affective Landscape of Severance

Corpus Pragmatics (2026)

-

The fragile intelligence of GPT-5 in medicine

Nature Medicine (2025)

-

Mindbench.ai: an actionable platform to evaluate the profile and performance of large language models in a mental healthcare context

NPP—Digital Psychiatry and Neuroscience (2025)