Abstract

Background

Gliomas account for approximately 25.5% of all primary brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumors and 80.8% of malignant brain and CNS tumors. The prognosis varies considerably; patients with low-grade gliomas (LGGs) have 5-year survival rates of up to 80%, while patients with higher-grade gliomas (HGGs) often experience rates below 5%. Recurrence is a common challenge, occurring in 52% to 62% of patients with LGGs and 90% of patients with HGGs, complicating clinical management and treatment planning. Currently, no widely available models exist for reliably predicting early glioma recurrence, which is critical for optimizing patient outcomes. Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques have shown promise in predicting recurrence for various cancers, with those utilizing multimodal data sources showing increasing promise.

Methods

We developed a DL-based predictive model with attention mechanisms, gLioma recUrreNce Attention-based classifieR (LUNAR), to predict early vs. late glioma recurrence using clinical, mutation, and mRNA-expression data from patients with primary grade II-IV gliomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and, as an external validation set, the Glioma Longitudinal Analysis Consortium (GLASS).

Results

Our model outperforms traditional ML models and non-attention counterparts, achieving area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 82.84% and 82.54% on the TCGA and GLASS datasets, respectively.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate the potential of multimodal DL classifiers for predicting early glioma recurrence. By integrating clinical, mutational, and transcriptomic data from patients, LUNAR enables improved risk stratification. Its consistent performance across two independent datasets underscores its robustness.

Plain Language Summary

Gliomas are a type of brain tumor that often return after treatment, making them difficult to manage. Patients with low-grade gliomas tend to have better long-term survival, while high-grade gliomas are much more aggressive. Deep learning is a type of machine learning where computers utilize layered networks, known as neural networks, to recognize patterns in large datasets. We developed a deep learning model to predict which patients with glioma will have early recurrence. This model uses clinical data from patients with glioma, as well as information about patients’ genetic mutations and gene activity. The model was tested on two independent patient datasets and outperformed traditional prediction methods indicating its potential to enhance care and treatment planning for patients with glioma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gliomas represent ~25.5% of all primary brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumors and 80.8% of malignant brain and CNS tumors1. Gliomas are highly infiltrative tumors classified and graded based on molecular and genetic markers, degree of proliferation, and necrosis2. Regardless of grade, gliomas are frequently characterized by their developed resistance to surgical and chemoradiation treatment regimens3,4. The heterogeneity of glioma leads to wide variations in outcomes and prognosis, with 5-year survival rates of up to 80% for patients with low-grade gliomas (LGGs) and less than 5% for patients with higher-grade gliomas (HGGs)1. The invasive nature of these tumors lends itself to a high likelihood of cancer recurrence, with 52–62% of LGGs5,6,7 and 90% of HGGs8 recurring. The time to recurrence of glioma varies widely, ranging from as early as 6 months to as late as 15 years5. For all glioma types, early recurrence poses a substantial challenge to clinical management and treatment planning. Insight into a patient’s likelihood of early recurrence can profoundly impact patient outcomes by optimizing intervention selection and timing, limiting unnecessary testing and procedures, and minimizing treatment-related disability9,10,11,12. However, there are currently no widely available prediction models for assessing the risk of early glioma recurrence.

The numerous benefits of predicting cancer recurrence are not exclusive to glioma. As such, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) methods have been applied to recurrence prediction tasks in multiple cancer types. González-Castro et al.13 evaluated the capacity of five ML classifiers to predict 5-year breast cancer recurrence using electronic health records. Their extreme gradient boosting model achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.807. Kumar et al.14 utilized dual convolutional neural networks to predict prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy using tissue images and achieved an AUROC of 0.81. Piedimonte et al.15 developed two ML models and two neural networks to predict recurrence and time to recurrence in high-grade endometrial cancer and achieved a maximum AUROC of 71.8% using clinical data. In the case of glioma, Luo et al.16 successfully applied deep learning to predict glioma recurrence at multiple time points using clinical data and hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stained slide images. A recent systematic review has demonstrated that ML algorithms for glioma recurrence prediction tasks often rely on imaging data, specifically MRI scans or MRI-derived features17. HGG recurrence prediction and detection models had a pooled AUROC of 0.8617,18,19,20,21. Du et al.21 developed a decision tree model using clinical information, molecular genetics information, and MRI radiomics scores to predict the risk of glioblastoma recurrence within one year following total resection. Their model achieved a testing AUROC of 0.719 and external validation AUROCs of 0.810 and 0.702 on two independent cohorts.

Attention mechanisms have become increasingly prevalent across a wide range of DL applications22. Lan et al.23 developed DeepKEGG, which uses a biological hierarchy and self-attention model to predict the recurrence of breast, liver, bladder, and prostate cancer. They reported AUROCs ranging from 0.799 to 0.961. Ai et al.24 developed a recurrence prediction model for non-small cell lung cancer using self-attention and CT images. Wang et al.25 developed hepatocellular carcinoma early recurrence prediction models that utilized intra- and inter-phase attention on clinical data, CT images, or both. Their model achieved a prediction accuracy of 81.2% and an AUROC of 0.869.

While the existing models are valuable, there is a current lack of prediction models that incorporate both clinical and genomic data from primary tumors to predict future early glioma recurrence. Additionally, current models often rely on imaging data. However, this data is typically challenging to obtain, given the difficulty of collecting large consented data sets and the resources required for large-scale image annotation, delineation, and labeling26.

Given the unmet need for early glioma recurrence prediction models and recent successful applications of attention mechanisms to disease-classification tasks, we use a DL-based predictive model, gLioma recUrreNce Attention-based classifieR (LUNAR), to predict early vs. late glioma recurrence using clinical, mutation, and mRNA-expression data from patients with primary grade II-IV gliomas from The Cancer Genome Atlas27 and the Glioma Longitudinal Analysis Consortium28. The model achieves AUROCs of 82.84% and 82.54% on the TCGA and GLASS datasets, respectively. Our findings highlight the potential of multimodal DL classifiers with attention mechanisms in predicting early glioma recurrence. By combining clinical, mutational, and transcriptomic data, LUNAR enhances early glioma recurrence prediction. Its stable performance across two independent datasets further demonstrates its robustness.

Methods

Datasets

We utilized publicly available datasets containing clinical and molecular information. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) has molecularly characterized tumors from over 11,000 patients across 33 cancer types, including multiple types of glioma27. To create a robust dataset of all TCGA primary diffuse gliomas, we downloaded clinical data, somatic mutations, and gene expression data for the LGG and Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) merged dataset, GBMLGG29, from cBioPortal (cbioportal.org)30,31 and the University of California, Santa Cruz Xena browser (xenabrowser.net)32,33. To minimize clinical data missingness, we supplemented the GBMLGG clinical data with data from the TCGA LGG34,35,36,37 and TCGA GBM38,39,40,41 datasets, as well as the TCGA Clinical Data Resource outcome and follow-up files42. As an independent validation dataset, we obtained data from the Glioma Longitudinal Analysis (GLASS) Consortium, a global collaboration dedicated to collecting and analyzing longitudinal genomic and molecular data from patients with glioma28. Using cBioPortal, we downloaded clinical data, somatic mutations, and gene expression data for primary tumors in the Diffuse Glioma GLASS dataset (version 2022-05-31)43,44.

Each dataset was limited to patients meeting the inclusion criteria outlined in Fig. 1. To restrict the inclusion of TCGA patients to those with disease progression only, we excluded patients with (1) no explicit recurrence indicator and (2) disease-free interval (DFI) event equal to zero (censored) or all new tumor event (NTE) types equal to Progression of Disease (Fig. 1). Explicit recurrence indicators included a recurrent tumor sample present in the dataset, NTE types of Recurrence or Locoregional Disease, and DFI event equal to one. Unlike the TCGA dataset, the GLASS dataset contains surgical timelines. As such, patients with recurrence were identified from recurrent tumor surgeries, eliminating the need for progression-only filtering. The GLASS and TCGA datasets contain tumor histology classifications that predate the 5th edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of CNS Tumors, which introduced substantial changes to glioma classification45. Per the 5th edition guidelines, adult-type diffuse gliomas are divided into three types: astrocytoma (IDH-mutant), oligodendroglioma (IDH-mutant and 1p19q codeleted), and glioblastoma (IDH-wildtype). To reflect the updated guidelines, we relabeled patients’ tumors according to IDH mutation and 1p19q codeletion status, using a modified version of the algorithm detailed by Gritsch et al.46 (Fig. 2). Additionally, the diagnosis of IDH-wildtype astrocytomas first requires the exclusion of (1) combined gain of chromosome 7 and loss of chromosome 10 (7+/10−), (2) EGFR amplification, and (3) TERT promoter mutations, any of which result in a classification of glioblastoma. The TCGA dataset contains clinical variables for the first and third criteria, allowing us to relabel multiple TCGA IDH-wildtype astrocytomas as glioblastomas. IDH-wildtype astrocytomas without 7+/10− or TERT promoter mutations were labeled as “astrocytoma-WT” to distinguish them from the relabeled IDH-mutant astrocytomas (Fig. 2). As GLASS does not have 7+/10− or TERT promoter mutation status, all IDH-wildtype astrocytomas were relabeled as “astrocytoma-WT.”

For GLASS patients, we defined time to recurrence (TTR) as the number of days elapsed between surgery for a patient’s primary tumor and the first surgery for a patient’s first recurrence. To calculate TTR for TCGA patients, we utilized patient status timelines (where status equaled Locoregional Disease or Recurrence) and treatment timelines (where regimen indication equaled Recurrence or anatomic treatment site equaled Distant Recurrence, Distant Site, or Local Recurrence) in addition to the clinical data files outlined above. We sorted TTR-applicable values into four tiers: (1) recurrence status start date, distant recurrence site treatment start date, local recurrence site treatment start date, and recurrence regimen indication start date; (2) DFI time; (3) locoregional disease status start date and days to NTE; and (4) days to NTE additional surgery. For each patient with at least one non-null TTR-applicable value, TTR was defined as the smallest value in the first non-empty tier, starting from Tier 1 (Supplementary Table S1). Patients without values in any of the four tiers were excluded from the study (Fig. 1). To classify patients as having had an early or late recurrence, we defined patients with \({TTR} < 0.5\left({{{\rm{median}}}}\left({{TTR}}_{{{{\rm{TCGA}}}}}\right)+{{{\rm{median}}}}\left({{TTR}}_{{{{\rm{GLASS}}}}}\right)\right)\) as early and patients with \({TTR}\ge 0.5\left({{{\rm{median}}}}\left({{TTR}}_{{{{\rm{TCGA}}}}}\right)+{{{\rm{median}}}}\left({{TTR}}_{{{{\rm{GLASS}}}}}\right)\right)\) as late. TCGA and GLASS had median values of 445 and 335 days, respectively, resulting in a cutoff of 390 days.

Data preprocessing

For both datasets, the gene expression data were log2(x + 1) transformed and mean-normalized per gene across their respective repositories prior to download. From the mutation annotation data, we calculated the number of non-silent mutations per gene per patient. The resulting genomic features for each patient were mutation counts per gene and mRNA expression per gene. Clinical, gene expression, and mutation features were limited to those shared between the TCGA and GLASS datasets. The distributions of variant types comprising the mutation count data for TCGA and GLASS are available in Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2, respectively. Overlapping clinical features included patient age, sex, IDH/1p19q status, tumor type (relabeled), and tumor grade. To avoid unintentional exclusion of genes between datasets, we downloaded all currently approved protein-coding genes on the 22 autosomes from the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee BioMart Gene repository47 and mapped gene names in each expression and mutation data to their approved symbols by Entrez ID or gene symbol. To maximize retention, we checked alias symbols and former symbols for all genes without direct matches. After applying all the above criteria, each dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and testing sets using a 70/15/15 split stratified by outcome label and tumor grade.

The input data underwent preprocessing prior to modeling. Clinical features were binarily encoded (patient sex), ordinally encoded (tumor grade), and categorically encoded (IDH/1p19q status and tumor type). Genes with non-zero mutation counts in less than 2% of the TCGA training cohort were excluded from the mutation data to reduce sparsity and noise. This threshold was selected based on the distribution of mutation frequencies (Supplementary Fig. S3). Mutation counts were then log-transformed to stabilize variance. To correct for batch effects across different tissue source sites, a mean-only ComBat48 batch correction was applied independently to expression and mutation features for both datasets using their respective training sets and tissue source site annotations. Near-constant features were then removed using a variance threshold (1e−8). Further feature refinement was conducted by removing highly correlated genomic feature pairs (correlation ≥0.90) using a two-step approach. First, within each correlated pair involving a literature-derived glioma-associated gene and a gene without known glioma association, we retained the literature-derived gene. Second, for the remaining correlated pairs, we removed the feature involved in the largest number of high correlation relationships; in cases of ties, the feature with lower variance was removed. For the complete list of prioritized genes and additional details of the correlation analysis, see the Supplementary Methods. Two of the categorical encodings for IDH/1p19q status (IDH-mutant with codeletion and IDH-mutant without codeletion) were removed due to perfect (1.0) pairwise correlation with oligodendroglioma and astrocytoma tumor type, respectively. To reduce the number of expression features (16,756), we employed stability-based feature selection using bootstrapped univariate feature selection (Scikit-Learn49 SelectFpr, α = 0.05) on the TCGA training data, retaining expression features selected in at least 80% of bootstraps. By using a stability-based bootstrapping approach, we were able to identify expression features that were robust to sampling variability, making our modeling less prone to overfitting and more generalizable. Given the comparatively low number of clinical features and the sufficient reduction of mutation features during low-frequency removal, neither the clinical nor the mutation data required additional feature selection. As a result, our final feature set included eight clinical features, 121 expression features, and 110 mutation features. Finally, clinical (age), expression, and mutation features were scaled using standard scaling (zero mean, unit variance) for clinical and expression data, and MinMax scaling (range [0, 1]) for mutation data, with scaling parameters derived exclusively from the TCGA training set to avoid data leakage49. All preprocessing transformations, including batch corrections and scaling, were subsequently applied to the validation and test sets, as well as the GLASS sets.

Final patient cohort

The TCGA dataset comprised 191 patients who met all the criteria outlined in Fig. 1. Of the TCGA patients included, 82 (42.9%) had recurrence less than 390 days after initial treatment, and 109 (57.1%) had at least 390 days between initial treatment and recurrence (Table 1). The majority of patients with late recurrences had grade II (n = 52, 47.7%) or grade III (n = 52, 47.7%) gliomas. While grade IV gliomas represented only 4.6% (n = 5) of late recurrences, 30.5% of patients with early recurrence had grade IV gliomas. Similarly, IDH-mutant gliomas were dominant in the late recurrence group (n = 81, 74.3%), of which 29.6% (n = 24) were 1p19q codeleted. Conversely, IDH-wildtype gliomas were dominant in the early recurrence group (n = 49, 59.8%), with only 10.9% (n = 9) of gliomas IDH-mutant and 1p19q codeleted. Astrocytoma was the most common tumor histology (n = 81), followed by glioblastoma (n = 66), oligodendroglioma (n = 33), and “astrocytoma wildtype” (n = 11). Descriptive statistics for the TCGA training split (n = 133), validation split (n = 29), and testing split (n = 29) are available in Supplementary Tables S2–S4.

The GLASS dataset comprised 101 patients who met all the criteria outlined in Fig. 1. Of the GLASS patients included, 58 (57.4%) had recurrence less than 390 days after initial treatment, and 43 (42.6%) had at least 390 days between initial treatment and recurrence (Table 2). Grade IV gliomas dominated across recurrence groups, making up 69.8% (n = 30) of late recurrences and 96.6% (n = 56) of early recurrences. Grade II and III gliomas were underrepresented in both groups, but more common in late recurrence (14.0% and 16.3%, respectively) than early recurrence (0% and 3.4%, respectively). Similarly, IDH-wildtype gliomas were dominant across recurrence groups, with 72.1% (n = 31) of late recurring gliomas and 98.3% (n = 57) of early recurring gliomas. Glioblastoma was the most common tumor histology (n = 83), followed by astrocytoma (n = 11), “astrocytoma wildtype” (n = 5), and oligodendroglioma (n = 2). Descriptive statistics for the GLASS training split (n = 70), validation split (n = 15), and testing split (n = 16) are available in Supplementary Tables S5–S7.

Statistics and reproducibility

To assess the reliability of our training and testing splits, we evaluated distributions of clinical variables across the training and testing sets for both TCGA (n train = 133, n test = 29) and GLASS (n train = 70, n test = 16). For categorical clinical variables, we used Chi-square tests of independence to identify differences in frequency distributions, except in cases where expected cell counts were less than five in a 2 × 2 contingency table, in which case we applied Fisher’s exact test. For patient age and TTR, we used the Mann–Whitney U test, a non-parametric test that does not assume normality. All statistical tests were two-sided, and significance was assessed using α = 0.05. Missing values for race and ethnicity (TCGA-only) were excluded pairwise for each comparison. The results for TCGA and GLASS are provided in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Because these tests were conducted to confirm comparability rather than test hypotheses, p-values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. We found that no clinical variables differed significantly between training and testing cohorts (all p > 0.05).

LUNAR

We developed gLioma recUrreNce Attention-based classifieR (LUNAR) using clinical, gene expression, and mutation data from patients with glioma to predict early and late recurrence. The PyTorch50 framework for LUNAR is outlined in Fig. 3. Expression and mutation features are first processed through a gene weighting module (GeneSelector), which applies a learnable element-wise gate (sigmoid-weighted mask) and encourages sparse gene selection via L1 regularization. Clinical features do not pass through a GeneSelector layer. Next, all modalities are processed through modality-specific encoders (ModalityEncoder), each comprised of three fully connected layers with layer normalization, ReLU activation, and dropout. Then, multi-head self-attention layers capture intra-modal relationships for each modality type. To capture inter-modal or cross-modal relationships, self-attention outputs for each possible pairing of modalities (clinical-expression, clinical-mutation, expression-mutation) are passed to bidirectional cross-modality attention (cross-attention) layers. The resulting cross-modal embeddings are averaged per modality and fused using a learned query attention pooling module (LearnedQueryAttention). The pooled representation is normalized and passed to a final fully-connected classifier (OutputClassifier), followed by a Sigmoid output layer. A detailed overview of the attention mechanisms employed by LUNAR is available in the Supplementary Methods.

LUNAR accepts tabular clinical, expression, and mutation count data as input. Gene selection is applied to expression and mutation data through learnable masks, and each modality type is encoded via modality-specific neural networks. Modality embeddings are passed to a self-attention layer. Self-attention outputs for every modality pairing are passed to bi-directional cross-attention layers, after which they are averaged by modality. A learnable query attention pooling module fuses the outputs into a single representation. The fused embedding is processed through fully connected layers and a Sigmoid output layer.

While TCGA and GLASS both describe grade II-IV glioma, they differ in population distribution and gene expression normalization technique. To mitigate domain shift between TCGA and GLASS, we incorporated a CORAL (CORrelation ALignment)51,52 loss during training, computed between expression and mutation embeddings from unlabeled GLASS training samples and the corresponding TCGA training data. CORAL minimizes the Frobenius norm between the covariance matrices of source (TCGA) and target (GLASS) embeddings, encouraging the model to learn domain-invariant representations and increasing overall generalizability. Labels from GLASS training data and validation data are not seen at any point in the training process. The total loss function combined binary cross-entropy with class weighting, a sparsity-promoting gene regularization term, and the CORAL alignment loss. Optimization was performed using Adam with a cyclical learning rate schedule. Finetuning of ModalityEncoder and OutputClassifier hidden dimensions, dropout rates, and learning rate were selected based on TCGA validation loss. Final model performance was measured on both the TCGA and GLASS test splits. LUNAR was not retrained on labeled GLASS data prior to evaluation. Details of the training configuration, computational resources, and model hyperparameters are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

To assess LUNAR’s performance, we benchmarked LUNAR against traditional classifiers used as baselines in prior cancer recurrence studies13,53. These models include linear support vector classifier (SVC), logistic regression, k-nearest neighbors (KNN), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and multi-layer perceptron (MLP)49,54. To assess the importance of attention on predictive performance, we conducted an ablation analysis with three additional models: LUNAR with only cross-attention (LUNAR-CAtt), LUNAR with only self-attention (LUNAR-SAtt), and LUNAR with neither cross- nor self-attention (LUNAR-Natt). All ML models used for baseline comparison were trained on the TCGA training set using the same selected features provided to LUNAR. For each model, we calculated the AUROC, the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC), accuracy, balanced accuracy, precision, recall (sensitivity), specificity, F1-score, true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives.

Results

Model performance

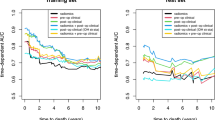

Across both evaluation sets, LUNAR and its ablated variants outperformed all baseline models in AUROC, AUPRC, accuracy, and precision. In the TCGA testing set, LUNAR achieved an AUROC of 82.84%, AUPRC of 76.59%, accuracy of 72.41%, and precision of 75.0%. LUNAR also performed highest in specificity (88.24%; tied across LUNARs), F1 (60.0%), and true negatives (n = 15; tied across LUNARs), and lowest in false positives (n = 2; tied across LUNARs). KNN and linear SVC tied for best recall (58.33%), false negatives (n = 5), and true positives (n = 7). However, KNN and linear SVC showed substantially worse performance, respectively, in AUROC (53.68%, 51.47%), AUPRC (45.53%, 51.06%), accuracy (44.83%, 51.72%), precision (38.89%, 43.75%), specificity (35.29%, 47.06%), F1 (46.67%, 50.0%), true negatives (n = 6, n = 8), and false positives (n = 11, n = 9). In the GLASS testing set, LUNAR achieved an AUROC of 82.54% (surpassed in this singular metric by LUNAR-NAtt; AUROC = 84.13%), AUPRC of 87.66%, accuracy of 75.0%, and precision of 69.23%. LUNAR also performed highest in recall (100.0%), F1 (81.82%), and true positives (n = 9), and lowest in false negatives (n = 0). LUNAR-NAtt and LUNAR-SAtt tied with LUNAR for top performance in accuracy, precision, recall, F1, false negatives, and true positives. Logistic regression, MLP, and linear SVC achieved the best scores for specificity (100.0%), true negatives (n = 7), and false positives (n = 0); however, they each made zero positive predictions (true positives = 0), indicating that these models have no predictive capability. As such, logistic regression, MLP, and linear SVC achieved precision, recall, and F1 scores of 0.0%. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and precision-recall (PR) curves are shown in Fig. 4. Full performance metrics and bar plots comparing AUROC and AUPRC across classifiers and datasets are available in Supplementary Tables S8, S9 and Supplementary Fig. S4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and precision-recall (PR) curves comparing LUNAR and the traditional baseline models’ performance on the TCGA (a, b) and GLASS (c, d) datasets. NAtt no attention, CAtt cross-attention only, SAtt self-attention only. *Indicates that a given model predicted one class only (no discriminative power).

Feature importance

We evaluated feature importance from two perspectives. First, to assess the impact of each feature on LUNAR’s predictions, we utilized SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) DeepExplainer (Supplementary Methods)55. A summary plot showing the 20 most important features to LUNAR when making predictions on the TCGA testing set is presented in Fig. 5. While CORAL domain adaptation was used to align TCGA and GLASS distributions during model training, SHAP explanations do not inherit this correction. The SHAP explainer relies on background samples drawn from TCGA only, without rotating across batches or domains, interpreting LUNAR exclusively in the context of TCGA distributions. However, our second perspective relied on fusion weights extracted from the LearnedQueryAttention (LQA) module of LUNAR (Fig. 3), thus enabling us to evaluate the relative contribution of each modality to the fused representations for patients in both the TCGA and GLASS testing sets (Supplementary Fig. S5).

The 20 most influential features according to DeepExplainer. Positive SHAP values (dots to the right) indicate an increase in the model’s prediction (towards an early prediction), while negative values (dots to the left) indicate a decrease (towards a late prediction). Note that for categorical features, red = Yes and blue = No, and the data points shown are post-processing and transformation. See the Methods and Fig. 2 for further details on the label Astrocytoma wildtype.

Median per-feature SHAP importance in the TCGA testing set was highest for clinical features (0.0262), followed by expression features (0.0019) and mutation features (0.0001), suggesting that clinical features have the greatest local contribution on average to LUNAR recurrence predictions. Conversely, median LQA attention weights were highest for mutation embeddings (TCGA = 0.353, GLASS = 0.346), followed by expression embeddings (TCGA = 0.339, GLASS = 0.340) and clinical embeddings (TCGA = 0.309, GLASS = 0.313), suggesting mutation embeddings are most important to LUNAR when fusing modalities (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Discussion

LUNAR, an attention-based multi-modal DL model, outperformed baseline comparators in predicting glioma recurrence in both the TCGA and GLASS datasets. According to SHAP (Fig. 5), LUNAR tended to output early recurrence predictions for patients with IDH-wildtype tumors and late recurrence predictions for patients with IDH-mutant tumors (or non-zero IDH1 mutation counts). Similarly, LUNAR trended towards early predictions for gliomas labeled as glioblastoma or astrocytoma wildtype, and towards late predictions for gliomas labeled as astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma. These patterns align with established literature, which has shown that mutations in IDH1/2 and 1p19q co-deletion (required for oligodendroglioma classification) are associated with an increased response to treatment and longer overall survival, and are more common in LGG1,56,57. The LUNAR SHAP results also reveal that as patient age increased, model predictions were pushed increasingly towards early recurrence. This pattern is consistent with findings that increased age is significantly associated with worse glioma outcomes across tumor grades58,59,60.

Multiple genomic features of high SHAP importance have established associations with glioma. For example, SHAP importance indicates that LUNAR was influenced towards early recurrence predictions in the presence of elevated expression of SCN9A, IGF2BP2, and SLC26A2. SCN9A encodes a voltage-gated sodium channel (Nav1.7) that functions in nociception signal transduction. A recent study by Bahcheli et al.61 found that high SCN9A expression was associated with poor prognosis in glioblastoma and was enriched in aggressive glioblastoma subtypes in TCGA (GBM), GLASS, and two additional datasets. Additionally, the authors demonstrated that SCN9A knockdown significantly reduced the viability of glioblastoma cells and inhibited tumor sphere formation in patient-derived glioblastoma cells, while substantially extending the survival of glioblastoma-bearing mice. IGF2BP2 encodes an mRNA-binding protein involved in metabolism and posttranscriptional regulation of RNAs62. Liu et al.63 found expression levels of IGF2BP2 (also known as Imp2) were up-regulated in LGG and HGG groups compared to normal brain tissues, and higher in HGG than LGG. Furthermore, knockdown of IGF2BP2 decreased expression of long noncoding RNAs and tight junction-associated proteins, resulting in increased blood-tumor barrier permeability and increased apoptosis of glioma cells caused by doxorubicin. Studies have shown that IGF2BP2 is highly expressed in glioma cells and tissues, promotes glioma progression through activation of the PI3k/Akt signaling pathway, and, when silenced, results in reduced survival of glioblastoma cells and etoposide-resistant cells64,65. SLC26A2, a diastrophic dysplasia sulfate transporter, was identified in a genome-wide loss-of-function screen as a novel mediator of TRAIL resistance that is aberrantly expressed in multiple human tumors66. Evaluating multiple public gene expression datasets, the authors found a significant increase in SLC26A2 expression in tumor tissues and that elevated expression correlated with metastasis or worsened prognosis in numerous tumor types, including three glioblastoma datasets and one oligodendroglioma dataset.

Although the results of our study are promising, there are several limitations and opportunities for improvement in future work. First, while the publicly available TCGA and GLASS datasets are highly valuable community resources, our sample size was relatively small after restricting to patients with recurrence events and all three data types. As such, the importance of rigorous and comprehensive clinical annotations cannot be overstated. Second, to create a harmonized model applicable to both TCGA and GLASS, we had to restrict our clinical feature space to features present in both datasets with similar value sets. As a result, potentially relevant clinical features, such as Karnofsky performance score and extent of tumor resection, could not be included as inputs to the model. Additionally, the treatment information provided for each dataset lacked sufficient details on treatment periods, which prevented the inclusion of adjuvant treatment as a feature in our model.

As a potential limitation to generalizability, our primary dataset had limited racial diversity, with 92.1% of patients identified as white. To minimize the possibility of overfitting to site- or population-specific data points, we validated our model on a separate non-overlapping dataset (GLASS). While LUNAR demonstrated strong generalization to the GLASS dataset, additional external validation will be essential to fully assess the model’s robustness and generalizability. Future evaluation on datasets from other institutions and patient populations, especially those with greater demographic diversity and differing environmental exposures, will help determine LUNAR’s reliability. Such validation is key to ensuring our model’s predictive capabilities extend beyond the cohorts assessed in our study.

From a modeling perspective, the framework carries several architectural and practical limitations. First, the model is structurally dependent on the availability of all three modalities—clinical, expression, and mutation—which may not be routinely available in clinical settings. While the goal of this study was to take maximum advantage of high-fidelity multi-modal data, future applications would require either sufficient resources to obtain all three data types or reengineering for partial-modality scenarios. Second, although the learned query attention mechanism provides interpretability in terms of modality-level contributions, it does not offer fine-grained feature-level attribution or guarantee causal importance. Lastly, while LUNAR’s performance was superior to the baseline models, our results indicate that the model’s predictive power could still be improved. Incorporating sufficiently detailed treatment information, altering the architecture to accommodate missing modalities (yielding more training samples), or utilizing contrastive learning pretraining are potential considerations for future enhancements. Despite these limitations, our preliminary results suggest the feasibility of DL-based predictive models for cancer recurrence prediction.

Conclusion

The TCGA and GLASS data repositories have become invaluable resources for genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic research, considerably advancing our understanding of glioma. LUNAR outperformed traditional ML models on both TCGA and GLASS datasets, both with and without attention, underscoring the potential of DL for meaningful pattern recognition in high-dimensional clinical and genomic datasets. By demonstrating the value of integrating clinical and genomic data within an attention-based framework, LUNAR provides a foundation and proof-of-concept that can guide and accelerate future development of predictive glioma models suitable for clinical integration, with the ultimate goal of improving clinical decision-making and outcomes for patients with glioma.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available and open access. The relevant files from each dataset used in this study are available on GitHub at https://github.com/TranslationalBioinformaticsLab/LUNAR (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16339523)67. TCGA GBMLGG expression data (Xena), mutation data (cBioPortal), and clinical data (Xena and cBioPortal) are available at https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?cohort=TCGA%20lower%20grade%20glioma%20and%20glioblastoma%20(GBMLGG) and http://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=lgggbm_tcga_pub. Additional patient and sample clinical data from TCGA LGG and TCGA GBM are available from Xena and cBioPortal at https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?cohort=TCGA%20Lower%20Grade%20Glioma%20(LGG), https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?cohort=TCGA%20Glioblastoma%20(GBM), http://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=lgg_tcga, and http://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=gbm_tcga. Patient treatment and status timelines from TCGA LGG and TCGA GBM are available from cBioPortal at http://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=lgg_tcga_pan_can_atlas_2018 and http://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=gbm_tcga_pan_can_atlas_2018. The TCGA Clinical Data Resource outcome and follow-up files are available at https://gdc.cancer.gov/about-data/publications/pancanatlas. Expression, mutation, and clinical data for the GLASS dataset are available from cBioPortal at http://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=difg_glass. Source data for all figures are included in the GitHub repository67. LUNAR results and baseline model results corresponding to Fig. 4 and Supplementary S4 are available in Supplementary Data 1. LUNAR SHAP values for the TCGA testing set corresponding to Fig. 5 are available in Supplementary Data 2. The TCGA somatic mutations and GLASS somatic mutations files corresponding to Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2 are available in Supplementary Data 3 and Supplementary Data 4, respectively. Mutation frequencies in the TCGA training set corresponding to Supplementary Fig. S3 are available in Supplementary Data 5. Attention weights retrieved from LearnedQueryAttention during the evaluation of the TCGA and GLASS testing sets are available in Supplementary Data 6.

Code availability

The models and code used for preprocessing and analysis are available on GitHub at https://github.com/TranslationalBioinformaticsLab/LUNAR (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16339523)67. All code is written in Python 3.9.16. The software utilized for this project includes PyTorch (2.5.1)50, Pandas (2.3.0)68, NumPy (1.26.3)69, SciPy (1.13.1)70, Scikit-Learn (1.6.1)49, XGBoost (2.1.4)54, Matplotlib (3.9.4)71, and SHAP (0.48.0)55.

References

Ostrom, Q. T. et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016. Neuro Oncol. 21, v1–v100 (2019).

Mesfin, F. B. & Al-Dhahir, M. A. Gliomas. In: StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2024).

Wen, P. Y. et al. Glioblastoma in adults: a Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) and European Society of Neuro-Oncology (EANO) consensus review on current management and future directions. Neuro Oncol. 22, 1073–1113 (2020).

Whitfield, B. T. & Huse, J. T. Classification of adult-type diffuse gliomas: impact of the World Health Organization 2021 update. Brain Pathol. 32, e13062 (2022).

Fukuya, Y. et al. Tumor recurrence patterns after surgical resection of intracranial low-grade gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 144, 519–528 (2019).

Shaw, E. G. et al. Recurrence following neurosurgeon-determined gross-total resection of adult supratentorial low-grade glioma: results of a prospective clinical trial: clinical article. J. Neurosurg. 109, 835–841 (2008).

Sanai, N., Chang, S. & Berger, M. S. Low-grade gliomas in adults: a review. J. Neurosurg. 115, 948–965 (2011).

Weller, M., Cloughesy, T., Perry, J. R. & Wick, W. Standards of care for treatment of recurrent glioblastoma—are we there yet?. Neuro Oncol. 15, 4–27 (2013).

Lorenzo, G. et al. Patient-specific, mechanistic models of tumor growth incorporating artificial intelligence and big data. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 26, 529–560 (2024).

Yankeelov, T. E., Quaranta, V., Evans, K. J. & Rericha, E. C. Towards a science of tumor forecasting for clinical oncology. Cancer Res. 75, 918–923 (2015).

Brady-Nicholls, R. et al. Prostate-specific antigen dynamics predict individual responses to intermittent androgen deprivation. Nat. Commun. 11, 1750 (2020).

Rockne, R. C. et al. The 2019 mathematical oncology roadmap. Phys. Biol. 16, 041005 (2019).

González-Castro, L. et al. Machine learning algorithms to predict breast cancer recurrence using structured and unstructured sources from electronic health records. Cancers 15, 2741 (2023).

Kumar, N. et al. Convolutional neural networks for prostate cancer recurrence prediction. In: Medical Imaging 2017: Digital Pathology. 10140, 106–117 (SPIE, 2017).

Piedimonte, S. et al. Predicting recurrence and recurrence-free survival in high-grade endometrial cancer using machine learning. J. Surg. Oncol. 126, 1096–1103 (2022).

Luo, C., Yang, J., Liu, Z. & Jing, D. Predicting the recurrence and overall survival of patients with glioma based on histopathological images using deep learning. Front Neurol. 14, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1100933 (2023).

Mohammadzadeh, I. et al. Can we rely on machine learning algorithms as a trustworthy predictor for recurrence in high-grade glioma? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 249, 108762 (2025).

Bacchi, S. et al. Deep learning in the detection of high-grade glioma recurrence using multiple MRI sequences: a pilot study. J. Clin. Neurosci. 70, 11–13 (2019).

Ren, J. et al. Multimodality MRI radiomics based on machine learning for identifying true tumor recurrence and treatment-related effects in patients with postoperative glioma. Neurol. Ther. 12, 1729–1743 (2023).

Rathore, S. et al. Radiomic signature of infiltration in peritumoral edema predicts subsequent recurrence in glioblastoma: implications for personalized radiotherapy planning. J. Med. Imaging 5, 021219 (2018).

Du, P. et al. The application of decision tree model based on clinicopathological risk factors and pre-operative MRI radiomics for predicting short-term recurrence of glioblastoma after total resection: a retrospective cohort study. Am. J. Cancer Res. 13, 3449–3462 (2023).

Golovanevsky, M., Eickhoff, C. & Singh, R. Multimodal attention-based deep learning for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 29, 2014–2022 (2022).

Lan, W. et al. DeepKEGG: a multi-omics data integration framework with biological insights for cancer recurrence prediction and biomarker discovery. Brief. Bioinform. 25, bbae185 (2024).

Ai, Y., Li, Y., Jain, R. K. & Chen, Y. W. A self-attention based fusion model of radiomics and deep features for early recurrence prediction in NSCLC. In IEEE 12th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics ((GCCE)) 833–837 (IEEE, 2023).

Wang, W. et al. Phase attention model for prediction of early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma with multi-phase CT images and clinical data. Front. Radio. 2, 856460 (2022).

Jacobs, F. et al. Opportunities and challenges of synthetic data generation in oncology. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 7, e2300045 (2023).

Hoadley, K. A. et al. Cell-of-origin patterns dominate the molecular classification of 10,000 tumors from 33 types of cancer. Cell 173, 291–304.e6 (2018).

The GLASS Consortium. Glioma through the looking GLASS: molecular evolution of diffuse gliomas and the Glioma Longitudinal Analysis Consortium. Neuro Oncol. 20, 873–884 (2018).

Ceccarelli, M. et al. Molecular profiling reveals biologically discrete subsets and pathways of progression in diffuse glioma. Cell 164, 550–563 (2016).

Cerami, E. et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2, 401–404 (2012).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Consortium. Merged Cohort of LGG and GBM (TCGA, Cell 2016). https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=lgggbm_tcga_pub.

Goldman, M. J. et al. Visualizing and interpreting cancer genomics data via the Xena platform. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 675–678 (2020).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Consortium. TCGA lower grade glioma and glioblastoma (GBMLGG). https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?cohort=TCGA%20lower%20grade%20glioma%20and%20glioblastoma%20(GBMLGG) (2016).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2481–2498 (2015).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Consortium. Brain Lower Grade Glioma (TCGA, Firehose Legacy). https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=lgg_tcga (2016).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Consortium. Brain Lower Grade Glioma (TCGA, PanCancer Atlas). https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=lgg_tcga_pan_can_atlas_2018 (2018).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Consortium. TCGA Lower Grade Glioma (LGG). https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?cohort=TCGA%20Lower%20Grade%20Glioma%20(LGG) (2016).

Brennan, C. W. et al. The Somatic Genomic Landscape of Glioblastoma. Cell 155, 462–477 (2013).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Consortium. Glioblastoma Multiforme (TCGA, Firehose Legacy). https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=gbm_tcga (2016).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Consortium. Glioblastoma Multiforme (TCGA, PanCancer Atlas). https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=gbm_tcga_pan_can_atlas_2018 (2018).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Consortium. TCGA Glioblastoma (GBM). https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?cohort=TCGA%20Glioblastoma%20(GBM) (2016).

Liu, J. et al. An integrated TCGA pan-cancer clinical data resource to drive high-quality survival outcome analytics. Cell 173, 400–416.e11 (2018).

Varn, F. S. et al. Glioma progression is shaped by genetic evolution and microenvironment interactions. Cell 185, 2184–2199.e16 (2022).

GLASS Consortium. Diffuse Glioma (GLASS Consortium) https://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=difg_glass (2022).

Louis, D. N. et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 23, 1231–1251 (2021).

Gritsch, S., Batchelor, T. T. & Gonzalez Castro, L. N. Diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic implications of the 2021 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system. Cancer 128, 47–58 (2022).

Seal, R. L. et al. Genenames.org: the HGNC resources in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D1003–D1009 (2023).

Johnson, W. E., Li, C. & Rabinovic, A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 8, 118–127 (2007).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Paszke, A. et al. PyTorch: an imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32, 8024–8035 (Curran Associates, Inc.; 2019). https://papers.neurips.cc/paper/9015-pytorch-an-imperative-style-high-performance-deep-learning-library.pdf.

Sun, B., Feng, J. & Saenko, K. Correlation alignment for unsupervised domain adaptation. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1612.01939 (2016).

Sun, B. & Saenko, K. Deep CORAL: correlation alignment for deep domain adaptation. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1607.01719 (2016).

Zuo, D. et al. Machine learning-based models for the prediction of breast cancer recurrence risk. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 23, 276 (2023).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 785–794 (ACM, 2016).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee S. I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (eds, Guyon, I., Luxburg, U., Bengio, S. et al.) 4765–4774 (Curran Associates, Inc.; 2018).

Yan, H. et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 765–773 (2009).

Leeper, H. E. et al. IDH mutation, 1p19q codeletion and ATRX loss in WHO grade II gliomas. Oncotarget 6, 30295–30305 (2015).

Krigers, A., Demetz, M., Thomé, C. & Freyschlag, C. F. Age is associated with unfavorable neuropathological and radiological features and poor outcome in patients with WHO grade 2 and 3 gliomas. Sci. Rep. 11, 17380 (2021).

Johnson, M. et al. Advanced age in humans and mouse models of glioblastoma show decreased survival from extratumoral influence. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 4973–4989 (2023).

Colopi, A. et al. Impact of age and gender on glioblastoma onset, progression, and management. Mech. Ageing Dev. 211, 111801 (2023).

Bahcheli, A. T. et al. Pan-cancer ion transport signature reveals functional regulators of glioblastoma aggression. EMBO J. 43, 196–224 (2024).

Dai, N. The diverse functions of IMP2/IGF2BP2 in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 31, 670–679 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. IGF2BP2 stabilized FBXL19-AS1 regulates the blood-tumour barrier permeability by negatively regulating ZNF765 by STAU1-mediated mRNA decay. RNA Biol. 17, 1777–1788 (2020).

Mu, Q. et al. Imp2 regulates GBM progression by activating IGF2/PI3K/Akt pathway. Cancer Biol. Ther. 16, 623–633 (2015).

Han, J. et al. IGF2BP2 induces U251 glioblastoma cell chemoresistance by inhibiting FOXO1-mediated PID1 expression through stabilizing lncRNA DANCR. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 659228 (2022).

Dimberg, L. Y. et al. A genome-wide loss-of-function screen identifies SLC26A2 as a novel mediator of TRAIL resistance. Mol. Cancer Res. 15, 382–394 (2017).

jessicapatricoski. TranslationalBioinformaticsLab/LUNAR: Version v1.1. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.16339523 (2025).

The pandas development team. pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.15597513 (2025).

Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank Brown University’s Center for Computation and Visualization for the computational resources and Dr. J. Nicholas Fisk for their valuable feedback on this work. We would like to dedicate this study to Dr. Alexander Brodsky, who passed away in November 2024. A devoted cancer researcher and esteemed colleague at the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Brown University, Dr. Brodsky’s contributions and unwavering dedication to science will always be remembered.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.P.C. and E.D.U.; Data preprocessing, modeling, and data analysis: J.P.C. under the advisement of E.D.U.; Funding acquisition: E.D.U. and J.L.W.; Methodology: J.P.C., R.S., S.N., J.L.W. and E.D.U.; Software: J.P.C.; Validation: J.P.C. and E.D.U.; Writing-Original Draft: J.P.C. and E.D.U.; Writing-review and editing: J.P.C., R.S., S.N., J.L.W. and E.D.U.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Anahita Fathi Kazerooni and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Patricoski-Chavez, J.A., Nagpal, S., Singh, R. et al. A deep learning model to predict glioma recurrence using integrated genomic and clinical data. Commun Med 5, 359 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01083-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01083-3