Abstract

Background:

Prior research has found altered levels of cytokines in people with eating disorders (EDs). This study is an update of a previous meta-analysis, including longitudinal analyses and machine learning heterogeneity analyses (MetaForest).

Methods:

This pre-registered (https://osf.io/g6d3f) systematic review and meta-analysis following PRISMA guidelines assessed studies from four databases (PubMed, Web of Science, MEDLINE, PsycINFO) reporting cytokine concentrations in people with EDs until 10th November 2024. Random-effects models were utilised for all meta-analyses.

Results:

Twenty-four new studies are incorporated, resulting in a total of 43 studies included in meta-analyses. Interleukin (IL)−6 and IL-15 are higher, and IL-7 lower, in anorexia nervosa (AN) compared with controls. When controlling for outliers, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-8, IL-10, interferon (IFN)-γ, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP) and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β are similar between AN and controls. Longitudinally, IL-6 is lower in AN at follow-up compared to baseline, although this may be an artefact of publication bias. TNF-α and IL-1β do not change longitudinally. There are largely no differences in IL-6 and TNF-α in bulimia nervosa (BN) and there are insufficient studies to perform meta-analyses for binge eating disorder or other EDs.

Conclusions:

In acute AN, concentrations of IL-6 and IL-15 are elevated and IL-7 is decreased, with preliminary but unconclusive evidence for small decreases in IL-6 over the course of weight restoration. Other cytokines considered to have broadly pro-inflammatory functions are not increased in AN. In BN, there is little evidence for increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines, but the evidence base is limited.

Plain language summary

This study looked at how certain immune system markers, called cytokines, are affected in people with eating disorders (EDs). Previous research suggested that people with EDs might have altered levels of these markers. In this study, 43 studies were analysed to compare cytokine levels in people with anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and other EDs. It was found that people with AN had higher levels of certain cytokines (IL-6 and IL-15) and lower levels of others (IL-7), when compared to healthy people. For bulimia nervosa, there was little evidence of altered cytokine levels. These findings are important because they may help improve understanding of the immune system’s role in EDs and suggest areas for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) including anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED), avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) and other specified feeding and eating disorder (OSFED), involve alterations in feeding and eating patterns and in some cases compensatory behaviours as an attempt to prevent weight gain or offset calorie intake. This group of disorders results in secondary consequences that impact physical systems within the body. One of these is the immune system; both the food restriction seen in EDs such as AN and patterns of overeating seen in binge-type EDs may lead to changes in the production and functioning of immune cells. Additionally, recent research has implicated the presence of autoimmune conditions as a risk factor for the development of an ED, and vice versa1.

Prior research has examined peripheral concentrations of cytokines in ED populations as indicators of changes in immune signalling. Cytokines are signalling proteins produced by immune cells, endothelial and epithelial cells, adipocytes and connective tissue, which can aid communication between cells in order to modulate the immune response. For example, by stimulating or slowing down the immune system or stimulating the movement of cells toward sites of infection or inflammation. They can have systemic as well as local effects and are pleiotropic in that a single cytokine can produce multiple biological functions. Common groups of cytokines include chemokines, which induce chemotaxis (cell migration); interleukins (IL), which act as chemical signals between white blood cells; interferons, which help the body resist viral infections and cancers; and the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) family, which have a wide range of effects on immune functioning, including in tissue modeling and remodelling, and neuronal development. They are often categorised as pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory2, although as aforementioned most cytokines exhibit pleiotropy and therefore may have either effects depending on factors such as the site of expression and/or cell target. Blood-borne cytokines are able to pass the blood-brain barrier to enter cerebrospinal fluid and interstitial fluid spaces of the brain3, although they are also produced in the brain by various cells such as neurons, astrocytes and microglia. Cytokines have been implicated in eating disorders due to their effects on appetite, body weight and eating behaviours, which may be mediated by their effects on brain areas such as the hypothalamus4.

Three meta-analyses have quantified differences in concentrations of cytokines between ED populations and healthy controls5,6,7, one of which examined only AN samples5. When comparing AN to healthy controls, these studies have found small-to-moderate sized increases in levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1ß, IL-6 and TNF-α5,6 and TNF-receptor-II5 in AN. In a meta-analysis of inflammatory markers in EDs as a broader group, it has also been found that levels of TNF-α, and IL-1β are elevated in comparison with healthy control individuals (HCs)7. This has led to propositions that increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines may be a factor implicated in the aetiology of AN8 and neuroinflammation is often cited as a possible aetiological factor in EDs (e.g9). However, this is not without debate, as several recent studies in both adolescents and adults with AN have failed to fully replicate these results and sources of this heterogeneity (moderators) are thus far unclear10,11,12,13,14.

This heterogeneity may be explained by differences in sample characteristics (e.g., age, illness duration) and study factors (e.g., controlling or not controlling for factors such as age, tobacco use, use of pharmacological medications)6. Most of the studies included in the 2015 and 2018 meta-analyses5,6 did not control for confounding clinical and lifestyle factors that may affect cytokine concentrations, such as age, menstruation, smoking status, medication usage, recent food intake, exercise, body fat, recent illness and concurrent medical (particularly inflammatory) or mental health diagnoses15,16,17,18,19,20. Since our last meta-analysis in 20186, several papers have been published that control for, or consider, such variables, which have had contrasting findings. Therefore, it is conceivable that the inclusion of newer studies controlling for such influences, or examining the effect of study quality, may modulate the overall effect sizes.

A prior meta-analysis found no changes after weight gain (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 17.5 kg/m2) in IL-6, TNF-α or IL-1β in people with AN followed longitudinally across three studies5. However, several studies with longitudinal designs over the course of weight restoration have since been published, enabling analyses with improved power. In conditions such as AN, it is possible that concentrations of cytokines are modified as dietary intake is reinstated8, and it has also been suggested that reductions in neuroinflammation may contribute to weight gain9.

This study aims to build upon a prior meta-analysis published by our group6, asking the following additional research questions: (i) Including new evidence, do cytokine concentrations differ between people diagnosed with an ED and healthy individuals?; (ii) Using machine learning approaches, are there any moderators that explain the observed heterogeneity between studies?; (iii) How do between-group effect sizes vary as a function of study quality or publication date?; (iv) In ED participants, do cytokine concentrations change as a function of weight gain and/or symptom improvement? Here we show that when including new studies, and controlling for outliers, a small-sized increase in IL-6 is found in acute AN which may decrease longitudinally. However, the findings for increases in other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, in AN, are less robust. Additionally, we show that across studies, concentrations of IL-15 are increased and IL-7 decreased in people with AN compared to controls.

Methods

The reporting of this systematic review was guided by the standards of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement21. The quality assessment of the studies was conducted according to a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottowa Scale (NOS22). The full quality appraisal of the studies can be found in the Supplementary Information and Supplemental Data 1.

The study protocol was prospectively registered on the Open Science Framework, which can be found at https://osf.io/g6d3f.

Literature search

Two reviewers (JLK and CB) independently searched four electronic databases (PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, MEDLINE and PsycINFO) from the date of the last review, 4th May 2018, until 10th November 2024. An identical search strategy from the previous review by Dalton et al.6 was replicated for this review. In short, searches included the following keywords, mapped to Medical Subject Heading with the Explode function where possible: eating disorder*, anorexia nervosa, bulimi* or binge eat* in combination with cytokine* chemokine*, inflammat*, interleukin, interferon, IFN, tumour necrosis factor, TNF, transforming growth factor or TGF. Searches were supplemented using the ascendancy approach (hand-searches of reference lists of relevant papers and reviews) and the descendancy approach (citation tracking in Google Scholar, Crossref).

Eligibility criteria

Studies in any language of any study design that assessed cytokine concentrations in the serum, plasma or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of individuals with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)23,24 or International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD)25,26 diagnosis of ED were eligible for inclusion. Studies were included if they reported cross-sectional comparisons of cytokine concentrations between an ED group and HCs, or longitudinal assessments at a minimum of two time-points, with BMI or ED symptoms assessed at both time points.

Studies were excluded if: (i) they did not report group comparisons or longitudinal measurements of cytokine concentrations; (ii) participants had an organic cause for their disordered eating e.g., cancer, immunological conditions, genetic disorder, etc.; (iii) the sample was comprised of animals; iv) they measured cytokine production or genetic expression but did not assess cytokine concentrations; or v) there was significant reported or suspected study overlap between publications, defined as the same patient and or control group. Review articles, meta-analyses, conference proceedings/abstracts, book chapters, and unpublished theses were also not included.

Source selection

Titles and abstracts of publications were imported into Endnote, where duplicates were removed. During an initial screening stage, titles and abstracts were assessed against basic eligibility criteria and those deemed likely to be irrelevant (e.g., studies in animal samples, studies of other medical or psychiatric conditions, studies with ineligible study designs such as reviews) were discarded. Full-texts of the remaining articles were then assessed against the full eligibility criteria, with the reasons for study exclusion documented (Fig. 1). The search process was conducted independently by two reviewers (JLK and CB) and discrepancies in the eligibility assessment were discussed and resolved through discussion including a third reviewer (BD). The search results were then added to those obtained from the previous review by Dalton et al.6 (i.e., studies published before 4th May 2018).

Data extraction

Two reviewers (JLK and CB) conducted the data extraction process and the extracted data was checked by one reviewer (JLK). At this stage, the references of the eligible publications were uploaded into an electronic summary table used in the previous study6 and databases were combined for extraction. Extracted data included publication identifiers (study title, year, author list); sample characteristics, including sample size, demographics (e.g. mean ± standard deviation [SD] age), diagnostic criteria and clinical characteristics (e.g. mean ± SD illness duration, mean ± SD BMI), and medication status; parameters of interest, measurement methods, and concentrations of cytokines (mean ± SD), time interval between measurements (longitudinal studies, in weeks or days), content of intervention between measurements (longitudinal studies); potential confounds and control for confounds including presence/absence of smoking as an inclusion criteria, number of participants taking psychotropic medications (and types); main and additional study outcomes. Authors of potentially eligible publications were contacted where data were not reported (n = 13). In total, eight of these authors replied and provided data11,13,27,28,29,30,31,32.

For studies that reported AN subtype data separately, the means and standard deviations were pooled for the AN meta-analyses. Standard errors (SE) were converted to SDs using the formula SD = \(\sqrt{N}x{SE}\), where N represents the sample size.

Synthesis of results

Where studies were clinically homogeneous they were considered for pooling in a meta-analysis. Meta-analyses were performed for each cytokine where four or more studies were available for each ED separately. Where there were fewer than four studies for a given cytokine or raw data could not be obtained from authors, results were narratively synthesised.

Statistics and reproducibility

Individual meta-analyses for each cytokine were conducted in Stata 18.033 using the ‘metan’ command. The main outcome measure was cytokine concentrations (pg/ml or ng/ml). Random effects-models using the DerSimonian & Laird method34 were used for all meta-analyses to pool the standardised mean difference (SMD) of the studies relative to the study sample size. The SMD of each study reflects the size of effect between the comparator groups in each study (i.e., ED vs. HC, or ED baseline vs. follow-up) relative to the variability observed in the study. All longitudinal meta-analyses utilised the two available time-points, or where multiple time-points were available, utilised the follow-up time-point representing weight restoration or discharge from care. Statistical significance of the overall SMD was ascertained according to the p < 0.05 threshold.

Outliers were identified when the confidence intervals (CI) of the individual study SMD did not overlap with the CI of the pooled effect (i.e., where the upper CI bound of the individual study effect is smaller than the lower CI bound of the pooled effect, or the lower CI bound of the individual study effect is bigger than the upper CI bound of the pooled effect). Sensitivity analyses removing identified outliers were conducted and SMDs were re-estimated.

Publication bias was explored using the Egger’s test for small study effects and funnel plots (Figs. S1–S16). The Duval and Tweedie trim and fill method35 was used to identify smaller studies causing funnel plot asymmetry, adjust for this asymmetry, and re-estimate SMDs after adjusting for missing studies.

Cumulative meta-analysis

To explore how the effect sizes evolved over time for the cross-sectional comparisons of the main pro-inflammatory cytokines previously synthesised (IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β) between AN and HC, cumulative meta-analyses were performed using NOS study quality total score, and year of publication as ordering variables. This enables an examination of how the effect size changes when adding new studies, starting from a) the newest studies to the oldest studies, and b) the highest quality studies to the lowest quality studies. Cumulative meta-analyses were displayed as forest plots (Figs. S17–20) and were interpreted by visual inspection.

Between-study heterogeneity

Between-study heterogeneity was assessed with the Higgins I2 statistic, based on the Cochrane’s Q (chi-square) statistic, which represents the proportion of total variation across studies that is attributable to heterogeneity rather than chance. Heterogeneity was considered to be substantial if above 50%, and considerable if above 75%. Tau2, which estimates the amount of true variability between the SMDs of the included studies, was also reported.

Subgroup analyses were conducted with AN subtypes, where the study reported data for each subtype (i.e., AN-restricting type [-R] and AN-binge-eating/purging type [-BP]) individually. To further explore sources of heterogeneity, a random-effects MetaForest analysis was conducted in R version 4.4.2 (R Core Team, 2021). MetaForest is a machine-learning based exploratory approach to meta-analysis that mitigates overfitting and assesses the relative importance of potential moderators36. First, the approach ranks moderators in terms of their importance in predicting the effect size; and recursive preselection plots are generated. Using 100-fold replicated feature selection, moderators that reduced predictive performance (i.e., those with positive variable importance in fewer than 50% of replications) were excluded. The remaining moderators were then used to optimize the model (model tuning), consisting of 10,000 regression trees with random-effects weights, again with 100 replications to ensure robustness. The model’s predictive performance was evaluated using the “out-of-bag” measure (R2oob), which estimates the variance explained by the moderators in a new dataset. A negative R2oob value indicates that the model’s predictions do not improve over simply using the average effect size as a predictor, suggesting that the moderators do not have a significant association with the effect size. Positive values indicate that the moderators explain variance in new data, and the most important moderators were then entered into meta-regressions. Analyses were only performed where there were 10 or more studies available. Pre-specified theoretical and methodological moderators are listed in Table 1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

An additional 18 studies not included in the previous meta-analysis6 were identified, resulting in a total of 43 studies from 11 countries included in the meta-analysis11,12,13,27,28,29,30,31,32,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70. Of these, 40 were included in the cross-sectional meta-analyses comparing cytokine concentrations between AN and HCs, seven in the cross-sectional meta-analyses comparing BN with HCs, and 11 in the meta-analyses examining cytokine concentrations longitudinally in AN. The study and sample characteristics for studies included in the meta-analyses are included in Supplemental Data 2. Findings of studies not included in the meta-analyses, due to insufficient data reporting or insufficient number of studies for meta-analysis10,12,13,27,28,29,30,39,40,41,45,66,68,71,72,73,74(including cross-sectional comparisons between BED and HCs and recovered AN and HCs), are summarized in Supplemental Data 4 and the Supplementary Information.

Cytokines included in the cross-sectional meta-analyses between AN and HC were TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-4, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-15, IFN-γ, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP). Cytokines included in the cross-sectional meta-analyses between BN and HC were IL-6 and TNF-α. Longitudinally in AN, cytokines available for meta-analysis included TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. Other cytokines were also measured in eligible studies, however sufficient data were not available to perform meta-analyses. Across studies, 31 studies measured cytokine concentrations peripherally in serum, 12 in plasma, and none in CSF.

The mean and SD age of participants with EDs and HCs was 21.7 ± 8.1 (n = 32 studies) and 21.4 ± 6.7 (n = 27 studies) years, respectively. All studies included only female participants. The mean BMI of the AN participants was 15.7 ± 2.3 kg/m2 (n = 34 studies), of BN participants was 31.7 ± 10.4 kg/m2 (n = 4 studies; 22.0 ± 3.1 kg/m2 when excluding one study with a specifically bariatric population66), and of HCs was 21.2 ± 3.0 kg/m2 (n = 29 studies). Diagnosis was based on the DSM-V (n = 14), DSM-IV (n = 28) or DSM-III (n = 1). Mean illness duration for ED participants, reported in 16 studies, was 5.2 ± 7.2 years. Medication usage of people in the ED groups was reported in 32 studies, and in 20 studies participants were confirmed medication-free as part of assessment or eligibility procedures. In the remaining 12 studies, medications used included anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, sedatives, neuroleptics and anxiolytics.

For the longitudinal studies in AN, the mean BMI at baseline was 15.6 ± 1.9 kg/m2 (n = 8 studies) and at follow-up was 18.4 ± 2.0 kg/m2 (n = 7 studies). The interval between baseline and follow-up assessments used in the meta-analyses ranged from 2−12 months. The intervention used across studies included inpatient weight restoration treatment (n = 5), specialist ED treatment (n = 1), unspecified weight gain treatment (n = 1) and with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT; n = 1), CBT alone (n = 1), and CBT with pharmacological therapy (n = 1). In one study, treatment was unspecified.

Quality assessment of included studies

The rating of studies depends on three characteristics: the selection of study groups, the comparability of groups and the ascertainment of the outcome. Of the included studies, 26 were good quality, 24 were fair quality and three were poor quality (see Supplementary Information for the full description of the quality assessment). A detailed overview of the variables controlled for in individual studies is provided in Supplemental Data 3.

Cross-sectional meta-analysis results

The results of the cross-sectional meta-analyses comparing participants with AN to HC, and participants with BN to HC, are displayed in Table 2.

Anorexia nervosa

Tumour-necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)

Across 30 studies with a total of 1636 participants (AN n = 872; HC n = 764), six found elevated levels of TNF-α and none reported reduced levels (Fig. 2). Across all studies there was a small difference in TNF-α concentrations between AN and HCs whereby AN had elevated levels (SMD = 0.27; 95% CI 0.01, 0.54; p = 0.040). Heterogeneity estimates were high (I2 = 84%; Table 2) and although there was no evidence of publication bias from the Egger’s test, there was clear funnel plot asymmetry with several studies showing an abnormally high SMD (Fig. S1). Subsequently six outliers were identified12,32,40,57,60,69. After removing these outliers, the effect size became marginal and non-significant (SMD = 0.06; 95% CI –0.10, 0.22; z = 0.71; p = 0.475) and the I2 heterogeneity estimate reduced to 47.26%.

N = 30 studies were included (AN n = 872, HC n = 764). Zero (black line) is the line of no effect, and studies to the right of zero indicate an elevation of TNF-α in AN compared to HCs. The red dotted line indicates the overall effect size. When removing outliers12,32,40,60,69 the SMD reduced to 0.06 and became non-significant (p = 0.475). Error bars reflect 95% CIs. SMD = standardized mean difference; CI = confidence intervals.

Sensitivity and moderator analyses

When removing studies where >10% of the sample was using psychotropic medication11,12,38,47,59,64, the SMD increased to 0.41 (p = 0.011). Heterogeneity tests remained consistent (I2 = 85%; Egger’s test z = 0.99, p = 0.322).

A total of 15 studies reported AN subtype data for TNF-α, which indicated no subgroup difference between the AN-R (AN-R n = 264; HC n = 315) and AN-BP (AN-BP n = 40; HC n = 182) meta-analyses (p = 0.690; Fig. S21). When including only these studies, neither meta-analyses showed significant differences between the individual subgroups (i.e., AN-R or AN-BP) and HCs.

Cumulative meta-analyses were conducted using year and NOS total study quality score as sorting variables in a descending fashion. A visual inspection highlighted that newer studies were associated with lower SMDs between AN and HC for TNF-α (Fig. S17), although the pattern for the NOS score was less clear (Fig. S18).

To further investigate sources of heterogeneity, an exploratory random-effects MetaForest analysis was conducted after removing study outliers. The analysis identified eight potential moderators (age of the AN sample, age of the HC sample, percentage of the sample using medication, age group, percentage of the sample who were smokers, sample type (serum/plasma), study quality score and year of publication; plots shown in Figs. S22–24), however none showed significant associations when entered into meta-regressions (Table S1). The full details can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

Across 25 studies including a total of 1596 participants (AN n = 822, HC n = 774), nine exhibited elevated levels and two exhibited reduced levels of IL-6 in AN (Fig. 3). The pooled mean concentrations of IL-6 were significantly higher in AN compared to HC with a small effect (SMD = 0.36; 95% CI 0.11, 0.61; p = 0.005; Table 2; Fig. 2). This analysis showed high heterogeneity (I2 = 82%) and the Egger’s test for small study effects was significant. Five studies were identified as outliers following an inspection of the 95% CIs11,12,32,40,60 and the funnel plot (Fig. S2). When removing these studies the SMD was slightly lower but remained significant (SMD = 0.32; p = 0.001); the I2 statistic lowered to 65.1% and the Egger’s test was no longer significant (z = 1.98, p = 0.050).

N = 25 studies were included (AN n = 822, HC n = 774). Zero (black line) is the line of no effect, and points to the right of zero indicate an elevation of IL-6 in AN compared to HCs. The red dotted line indicates the overall effect size. When removing outliers11,12,32,40,60 the SMD reduced to 0.32 but remained significant (p = 0.001). Error bars reflect 95% CIs. SMD standardized mean difference, CI confidence intervals.

Sensitivity and moderator analyses

When removing studies where >10% of the sample were using psychotropic medication11,12,38,47,59,64, the SMD increased to 0.50 and remained significant (p < 0.001), although heterogeneity remained high (I2 = 82%) and the Egger’s test was significant (z = 2.33; p = 0.020).

A total of 15 studies reported AN subtype data, which indicated no subgroup difference between the AN-R (AN-R n = 370; HC n = 433) and AN-BP (AN-BP n = 36; HC n = 180) meta-analyses (p = 0.790; Fig. S25). With this fewer number of included studies, neither meta-analysis showed significant differences between the individual subgroups (i.e., AN-R or AN-BP) and HCs.

In cumulative meta-analyses, both forest plots indicated that higher quality studies and newer studies had overall lower SMDs between AN and HC (Figs. S19 and S20).

After removing study outliers, an exploratory random effects MetaForest analysis identified the following moderators as the most important in explaining the effect size: study year, NOS score, study region, age group, percentage of sample using medication, fasting status, mean age, BMI, and illness duration of the AN sample, and mean age and BMI of the HC sample (Supplementary Information; plots shown in Figs. S26–28). These moderators were entered into meta-regressions (Table S2). Only study region was significant, with studies conducted in North America showing a greater difference between AN and HC compared to studies in Europe (B = 0.78; SE = 0.29; z = 2.72; p = 0.007; 95% CI 0.22, 1.34).

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β)

Across 14 studies with a collective sample size of 598 participants (AN n = 354, HC n = 244), there was a non-significant moderate-sized increase in pooled concentrations of IL-1β between AN and HC groups (SMD = 0.53, 95% CI -0.06, 1.12; p = 0.080; I2 = 91%; Table 2; Fig. 4). From exploring the heterogeneity (95% CIs) and the funnel plot whereby two studies had abnormally high SMDs and one low (Fig. S3), three studies were identified as outliers40,60,64. The effect size was smaller and remained non-significant after removing these studies (SMD = 0.23; 95% CI –0.04, 0.50; z = 1.67; p = 0.095; I2 = 44%).

N = 14 studies were included (AN n = 354, HC n = 224). Zero (black line) is the line of no effect, and points to the right of zero indicate an elevation of IL-1β in AN compared to HCs. The red dotted line indicates the overall effect size. When removing outliers40,60,64 the SMD reduced to 0.23 and remained non-significant (p = 0.095). Error bars reflect 95% CIs. SMD standardized mean difference, CI confidence intervals.

Sensitivity and moderator analyses

There were three studies where >10% of the sample were using psychotropic medication11,59,64. When removing these studies, the SMD increased substantially to 0.79 and became significant (p = 0.026), although heterogeneity estimates were similar (I2 = 90%).

Subgroup analyses according to AN subtype were not possible, as few studies reported data per subtype. An exploratory random effects MetaForest analysis provided no evidence for associations between the entered moderators and the SMD for IL-1β (Supplementary Information; Fig. S29).

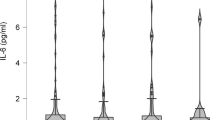

Other cytokines available for meta-analysis

Eight additional cytokines had at least four studies available and thus were meta-analysed (IL-4, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-15, IFN-γ, MCP and TGF-β; Fig. S30 and S31, Table 2). Only concentrations of IL-15 and IL-7 were significantly different between AN and HC, whereby IL-15 was higher in the AN group with a moderate effect size (SMD = 0.67; 95% CI 0.07, 1.26; p = 0.029; I2 = 83%) and IL-7 was lower in AN with a moderate effect size (SMD = -0.58, 95% CI -1.07, -0.09; p = 0.020; I2 = 76%). Concentrations of IL-4, IL-8, IL-10, IFN-γ, MCP and TGF-β were not significantly different between AN and HCs.

One study was identified as an outlier in the meta-analyses of IL-10 and IFN-γ27, and the removal of this study reduced the SMDs to –0.04 (95% CI –0.28, 0.20; p = 0.761; I2 = 32%) and –0.11 (95% CI –0.51, 0.28; p = 0.571; I2 = 59%), respectively. One outlier was identified in the IL-8 meta-analysis32, and the removal of this study increased the SMD to 0.13 (95% CI –0.40, 0.67; p = 0.626). Two studies40,60 were identified as outliers in the TGF-β meta-analysis, and the removal of these lowered the SMD to –0.14 (95% CI –0.11, 0.84; p = 0.783).

According to I2, estimated heterogeneity was high in the meta-analyses of IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-15, IFN-γ and TGF-β. The trim and fill method resulted in two imputed studies in both the IL-4 and MCP analyses (Figs. S32 and S33); adjusting for these imputed studies altered the SMDs to –0.09 and –0.10, respectively (both still non-significant). Funnel plots for meta-analyses are included in the Supplementary Information (Figs. S4–11).

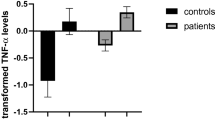

Bulimia nervosa

Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

The meta-analyses of the studies (n = 5) in BN populations indicated higher concentrations of IL-6 in participants with BN (n = 163) compared with HCs (n = 115), although this was not significant (Table 2; Fig. 5). One study66 was deemed an outlier, which is likely due to the higher mean BMI of the sample (41.1 kg/m2). Removing this study from the IL-6 meta-analysis reduced the pooled SMD to 0.30 (95% CI -0.25, 0.86; p = 0.287; I2 = 65%).

Zero (black line) is the line of no effect, and points to the right of zero indicate an elevation of the cytokine in BN compared to HCs. When removing a study outlier66, effect sizes reduced to 0.30 and 0.72, respectively; both analyses were then non-significant. Error bars reflect 95% CIs. CI confidence intervals, IL interleukin, SMD standardized mean difference, TNF-α tumour necrosis factor-alpha.

Tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)

There were significantly higher concentrations of TNF-α in participants with BN compared with HCs (Table 2; Fig. 5) across five studies (BN n = 145, HC n = 123). The heterogeneity estimates were considerably high for both analyses. The funnel plot indicated asymmetry (Fig. S13) which was confirmed by a significant Egger’s test for small study effects (z = 4.91, p < 0.001). The same study66 was deemed an outlier and removing this study reduced the overall effect size (SMD = 0.72) rendering the difference between groups non-significant (95% CI -0.14, 1.58; p = 0.101) and slightly reducing the I2 heterogeneity statistic to 84%. After removing this study the Egger’s test was no longer significant (z = 1.30, p = 0.192).

Longitudinal meta-analyses in AN

There were sufficient data to meta-analyse differences between baseline and follow-up in individuals with AN undergoing weight restoration for the cytokines IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α. All meta-analyses utilised the two available time-points, or where multiple time-points were available, utilised the follow-up time-point representing weight restoration or discharge from care. Insufficient studies were available to investigate longer-term follow-ups. Forest plots for the analyses can be seen in Figs. S34–36 and full results of the analyses can be seen in Table 3.

As sensitivity analyses, studies were removed from analyses where either ≤10% weight gain occurred, where participants didn’t reach at least 80% ideal body weight, or where the follow-up group mean BMI was ≤17 kg/m2, depending on what data was reported in the study. There were insufficient studies to explore moderators or conduct subgroup analyses.

Tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)

The meta-analysis of TNF-α included 267 AN participants at baseline and 240 at follow-up (mean BMI increase 2.85 kg/m2, reported by eight studies) from nine studies, finding no significant difference between time-points (SMD = -0.05, 95% CI -0.22, 0.13; p = 0.617 I2 = 0%; Table 3; Fig. S34). The follow-up period across studies ranged from 7.3−32.2 weeks (M ± SD = 14.1 ± 8.3 weeks). The trim and fill procedure imputed two missing studies (Fig. S37), increasing the SMD to –0.07 (95% CI –0.24, 0.10). The estimated SMD remained similar when removing three studies28,65,70 where weight increase was insufficient (SMD = –0.04; 95% CI –0.23, 0.15; z = -0.43; p = 0.670).

Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

Across eight studies with 279 AN participants at baseline and 239 participants at follow-up collectively (mean BMI increase 2.87 kg/m2, reported by six studies), concentrations of IL-6 were significantly higher at baseline than follow-up with a small effect size (SMD = 0.21; 95% CI 0.01, 0.42; p = 0.042; I2 = 22%; Table 3; Fig. S35). The follow-up period across studies ranged from 7.3−52 weeks (M ± SD = 16.8 ± 14.7 weeks). The Egger’s test for small study effects was significant (Table 3) and the trim and fill procedure identified three missing studies (Fig. S38). When imputing these studies, the re-estimated SMD lowered to 0.10 and was non-significant (95% CI –0.13, 0.32). Additionally, when removing two studies where the BMI at follow-up was insufficient28,70, the SMD reduced to 0.19 and again was non-significant (95% CI –0.05, 0.43; z = 1.52; p = 0.129).

Interleukin-1β

Five studies with 125 AN participants at baseline and 104 participants at follow-up (mean BMI increase 2.40 kg/m2, reported by four studies) were available for the meta-analysis of IL-1β concentrations. The follow-up period across studies ranged from 9.7 to 19.6 weeks (M ± SD = 13.3 ± 4.3 weeks). There was no significant difference between the baseline and follow-up time-points in IL-1β concentrations (SMD = 0.003; 95% CI -0.37, 0.37; p = 0.988; I2 = 39%; Table 3; Fig. S36). After removing two studies where there was insufficient weight increase28,70, the SMD increased to –0.10 but remained non-significant (95% CI –0.68, 0.48; z = -0.34; p = 0.733).

Discussion

This updated systematic review examined cytokine concentrations in people with AN and people with BN compared with controls, and in AN across multiple time-points (largely, after weight restoration treatment). A total of 53 studies were included, 43 of which were entered into meta-analyses with a combined total of 2,533 participants. Cross-sectionally, in people with AN, concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α were significantly higher with a small effect size, although differences in TNF-α became smaller and non-significant when removing study outliers. These analyses did not differ according to AN subtype, but when removing studies where > 10% of the sample were taking psychotropic medication, the effect size increased for IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1ß (the latter becoming significant, with elevated levels in AN). Cumulative meta-analysis plots visually indicated that higher quality and more recently published studies produced smaller effect sizes. Concentrations of IL-15 were moderately higher in AN, and concentrations of IL-7 were moderately lower, compared with controls. Several other cytokines (IL-1β, IL-4, IL-8, IL-10, IFN-γ, MCP and TGF-β) were not significantly different between AN and controls. For the cross-sectional analyses of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, machine learning was used to explore sources of heterogeneity, although it did not identify any consistently important moderator. Longitudinally, meta-analyses were performed to examine differences in concentrations of IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β from baseline to follow-up in AN, finding significant but small decreases over time only for IL-6, although this may be due to publication bias as this finding was no longer significant when adjusting for funnel plot asymmetry.

In BN, sufficient data were available for IL-6 and TNF-α, whereby TNF-α was significantly higher than controls with a large effect size, although critically this effect size substantially decreased and became non-significant when removing a study outlier.

The findings of this updated review broadly align with and extend the results of Dalton, et al.6. However, they also indicate the absence of a systemic inflammatory profile in AN, given that the majority of pro-inflammatory cytokines did not show elevations, and meta-analyses of other proteins that are indicative of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein, show decreases in AN75. Nevertheless, it is apparent that concentrations of IL-6 may be slightly elevated in the acute stages of AN and may decrease longitudinally. Interestingly, the pleiotropic functions of IL-6 include both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects. Secreted by macrophages in response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), it is known to mediate fever and the acute phase immune response, but also has inhibitory effects on TNF76,77. Relevant to AN, IL-6 has also been found to stimulate energy mobilization78 and as a myokine is elevated up to one hundred times basal rate during exercise in response to muscle contraction79. Therefore, the factors contributing to increased IL-6 in acute AN could be manifold both as a result of the behavioural symptoms associated with AN and the adaptation of the body to starvation.

Across the longitudinal studies, the average BMI increase ranged from 2.40 kg/m2 to 2.87 kg/m2, although in approximately half of studies in each analysis, the follow-up BMI did not surpass 18.5 kg/m2. Therefore, it is possible that changes from baseline to follow-up may have been more pronounced with more consistent weight restoration. With further longitudinal studies including multiple time-points, future meta-analyses could explore the temporal dynamics of cytokine concentrations according to different BMI thresholds. Additionally, there was considerable variability in the time interval between baseline and follow-up (7.3−52 weeks across all studies), which may have contributed to our findings. The current evidence may signal that there is an absence of a substantial change in cytokine levels longitudinally, although more research is required.

Additionally, concentrations of IL-15 and IL-7 showed moderately-sized increases and decreases, respectively, in the acute stages of AN. Furthermore, one study included in this meta-analysis in adolescents with AN found elevated IL-15 at baseline, discharge (weight restoration) and after a 1 year follow-up11. IL-15 induces the proliferation of natural killer cells in the innate immune system80 but has both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects depending on its expression and site of action. It has been suggested that increases in IL-15 have a pathophysiological role in AN, specifically pertaining to its anabolic role in maintaining muscle mass in the case of acute illness and starvation11. This adaptation hypothesis would however not explain the elevated concentrations seen after weight restoration and after long-term follow-up in the aforementioned study11. Although, it could be related to exercise levels as IL-15 is upregulated after acute and chronic exercise81. IL-15 also modulates serotonergic transmission82 and synaptic GABAergic transmission in the hippocampus, impairing short- and long-term episodic memory83, and thus may be involved in the mood and memory disturbances often seen in AN. IL-7 has essential roles in providing survival and growth signals for different immune cells, and low levels can produce immune deficiencies due to lymphopenia84, which is seen in AN and is thought to be a result of malnutrition85,86. Indeed, reduced levels of IL-7 are not observed in constitutional thinness where individuals are underweight without a change in eating behaviour72, and in AN, a longitudinal study has found increases in IL-7 with weight gain29.

It is notable that in the 7 years since the previous meta-analysis was published28, to the best of our knowledge only two new studies published in BN samples were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analyses, despite calls for more such studies in this population and in people with BED. The results including these new studies were broadly aligned with the previous meta-analysis, when removing one study that constituted a clear outlier. Overall, the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 were similar between people with BN and controls. Moreover, one additional study found a decrease in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in BN compared to BMI-matched controls66. In BED, there were insufficient studies to perform meta-analyses. A single study found a decrease in IL-10 in people with BED, although this was also found in individuals with obesity who did not have BED27. In another study, TNF-α was found to be elevated in BED compared to non-BED controls with a similar BMI71, although IL-671 and IL-1ß27 were similar between BED and controls. Therefore, decreases in IL-10 in BN and increases in TNF-α in BED may be BMI-independent findings in these populations, although more research is necessary.

This study was a well-controlled and pre-registered systematic review and meta-analysis of cytokine concentrations including the most studies of any meta-analysis published thus far, to the authors' knowledge. Authors were contacted where data were unavailable in publications, enabling the inclusion of eight additional studies. We were able to expand on the previous meta-analysis both by (a) including new studies of cytokines that have previously been meta-analysed; (b) meta-analysing several new cytokines that have not been previously examined, to the best of our knowledge; (c) examining changes in pro-inflammatory cytokines longitudinally in people with AN; and (d) utilising various approaches, including machine learning, to examine potential sources of heterogeneity. For transparency, these moderator analyses employing machine learning were decided for after pre-registration.

There are several limitations associated with the study design and conduct of the study. Firstly, because of the nature of cytokine data, data distributions across samples often showed skewedness, and therefore authors publish median rather than mean averages for their samples. Where this occurred, authors were contacted for mean and standard deviation values for samples to enable inclusion in the meta-analysis. One acknowledgement of this approach is that meta-analyses of cytokines including such studies may be inherently biased, although an advantage of including these studies is that the analyses have increased power. Likewise, removing study outliers may introduce bias into results as it is possible that extreme results may constitute real biological anomalies. Therefore, we opted to report results before and after removing outliers. Finally, the results of the cumulative meta-analyses were interpreted visually, therefore the conclusions drawn from these analyses should be taken with caution.

Other limitations relating to the included studies themselves pertain mostly to a lack of data reporting, as aforementioned. Not all studies, for example, reported the fasting status of their sample, or the age range of their sample, meaning that several moderators had missing data. Therefore, the predictive capability of the machine learning approach to moderator identification, and the follow-up meta-regressions, was limited. There was also a paucity of longitudinal studies reporting cytokine concentrations after long-term follow-ups or prospectively over the longer-term course of the illness, meaning that it was not possible to examine trajectories over illness stages (e.g., in the case of longstanding, protracted, or severe-enduring illness). Likewise, we could unfortunately not perform subgroup analyses by BMI category, sex or psychotropic medication status as data were not reported in the studies. It is likely that these are important moderators given that cytokine levels fluctuate according to weight87, menstrual cycle stage and sex88,89, and psychotropic medication usage18.

Conclusions and future directions

Overall, it can be concluded that increases in IL-6 in the acute stages of AN are more robust than increases in TNF-α, and increases in IL-15 and decreases in IL-7 are apparent in AN compared with controls. Concentrations of IL-6 decrease longitudinally in people with AN, which may be associated with weight recovery, although this may also be due to publication bias and thus needs further investigation. When considering the effects of outliers, other cytokines (IL-1β, IL-4, IL-8, IL-10, IFN-γ, MCP, TGF-β and TNF-α) were not altered in AN. There were no differences between people with BN and healthy controls in IL-6 and TNF-α. Heterogeneity was generally high across analyses, the source of which remains unclear, although there appears to be a trend whereby higher quality and more recent studies showed smaller differences.

Notably, not all studies reported key data that enabled more in-depth moderator or subgroup analyses examining key variables known to influence immune functioning, such as smoking status19, use of psychotropic medications18, time of sampling (circadian rhythms)90,91,92, and fasting status/dietary habits93. The present study found an increase in differences between AN and HC in IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1ß when samples with a high usage of psychotropic medication were excluded, likely as the usage of medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) is associated with lower levels of IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1ß94. Therefore it is particularly important that studies report data according to whether individuals are or are not taking psychotropic medication, or consider this as an exclusion criterion. With this in mind, in Table 4 we have listed further recommendations to enable standardised reporting across studies to enable future high-quality and well-powered meta-analyses, individual participant data meta-analyses, and detailed moderator analyses of cytokine and other biological data in ED populations.

We reiterate from our previous publication6 that studies in ED diagnoses under-represented in this field of research, such as people with BN, BED, ARFID, and atypical AN, are needed. Studies should also carefully consider eligibility criteria for the research to minimise the confounding influence of comorbid illness (e.g., recent infection or inflammatory/autoimmune conditions) or lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, alcohol misuse), as well as methodological factors, and transparently report key variables relating to their samples (Table 4).

As a final remark, alterations in the concentration of other immune molecules such as immunoglobulins and C-reactive protein have also been suggested to be associated with AN and other EDs. For example, immunoglobulin G (IgG) seems to play a role as α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH)-binding protein in the blood, and its levels have been found to be low in patients with AN at hospital admission but to increase alongside weight recovery95. Alterations in IgG autoantibodies directed to ghrelin and leptin might also be involved in the development of EDs96. Additionally, immunoglobulin A (IgA) concentrations have been found elevated in the saliva of patients with AN97. As aforementioned, C-reactive protein has been found to be decreased in AN75. Thus, for a comprehensive understanding of changes in immune molecules within patients with EDs, the complex relationships between cytokines, IgG, IgA, C-reactive protein and other molecular and cellular immune markers should be considered. Principal component analyses or machine learning approaches might help identifying subtypes with shared immunological profiles. The identification of such subtypes in future research might be more meaningful for the development of individually tailored biological treatments for people with EDs than a comparison of mean cytokine levels.

Data availability

The source data for Figs. 2, 3 and 4 are in Supplemental Data 5 (sheets 1, 2 and 3, respectively). The source data for Fig. 5 is in Supplemental Data 5, sheet 5. The source data for Figs. S30 and S31 is in Supplemental Data 5, sheet 4. The source data for Figs. S34, S35 and S36 is in Supplementary Data 5 (sheets 6, 7 and 8, respectively). All other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hedman, A. et al. Bidirectional relationship between eating disorders and autoimmune diseases. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 60, 803–812 (2019).

Himmerich, H., Patsalos, O., Lichtblau, N., Ibrahim, M. A. & Dalton, B. Cytokine research in depression: principles, challenges, and open questions. Front. Psychiatry 10, 423189 (2019).

Banks, W. A., Kastin, A. J. & Broadwell, R. D. Passage of cytokines across the blood-brain barrier. Neuroimmunomodulation 2, 241–248 (1995).

Wong, S. & Pinkney, J. Role of cytokines in regulating feeding behaviour. Curr. Drug Targets 5, 251–263 (2004).

Solmi, M. et al. Inflammatory cytokines and anorexia nervosa: a meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology 51, 237–252 (2015).

Dalton, B. et al. A meta-analysis of cytokine concentrations in eating disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 103, 252–264 (2018).

Dani, C. et al. A transdiagnostic and diagnostic-specific approach on inflammatory biomarkers in eating disorders: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 340, 116115 (2024).

Brooks, S., Dahl, K., Dudley-Jones, R. & Schiöth, H. A neuroinflammatory compulsivity model of anorexia nervosa (NICAN). Neurosci. Biobehav. Revi. 159, 105580 (2024).

Rantala, M. J., Luoto, S., Krama, T. & Krams, I. Eating disorders: an evolutionary psychoneuroimmunological approach. Front. Psychol. 10, 2200 (2019).

Breithaupt, L. et al. Identification of state markers in anorexia nervosa: replication and extension of inflammation-associated biomarkers using multiplex profiling. Biol. Psychiatr. Glob. Open Sci. 4, 11 (2024).

Käver, L. et al. Cytokine and microbiome changes in adolescents with anorexia nervosa at admission, discharge, and one-year follow-up. Nutrients 16, 1596 (2024).

Keeler, J. L. et al. Reduced MIP-1β as a trait marker and reduced IL-7 and IL-12 as state markers of anorexia nervosa. J. Pers. Med. 11, 814 (2021).

Nilsson, I. A. K. et al. Aberrant inflammatory profile in acute but not recovered anorexia nervosa. Brain Behav. Immun. 88, 718–724 (2020).

Specht, H. E. et al. Lower serum levels of IL-1β and IL-6 cytokines in adolescents with anorexia nervosa and their association with gut microbiota in a longitudinal study. Front Psychiatry 13, 920665 (2022).

Dugué, B., Leppänen, E. & Gräsbeck, R. Preanalytical factors and the measurement of cytokines in human subjects. Int. J. Clin. Laboratory Res. 26, 99–105 (1996).

Goebel, M. U., Mills, P. J., Irwin, M. R. & Ziegler, M. G. Interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α production after acute psychological stress, exercise, and infused isoproterenol: differential effects and pathways. Biopsychosocial. Sci. Med. 62, 591–598 (2000).

Haack, M. et al. Plasma levels of cytokines and soluble cytokine receptors in psychiatric patients upon hospital admission: effects of confounding factors and diagnosis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 33, 407–418 (1999).

Munzer, A. et al. Impact of antidepressants on cytokine production of depressed patients in vitro. Toxins 5, 2227–2240 (2013).

Rom, O., Avezov, K., Aizenbud, D. & Reznick, A. Z. Cigarette smoking and inflammation revisited. Resp. Physiol. Neurobiol. 187, 5–10 (2013).

Zhang, Y. et al. Peripheral cytokine levels across psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 125, 110740 (2023).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj 372, n71 (2021).

Wells, G. A. et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) For Assessing The Quality Of Nonrandomised Studies In Meta-Analyses. https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (2000).

American Psychiatric Association. Nominate Candidates for APA's 2025 National Board of Trustees Election Cycle. https://www.psychiatry.org/ (1990).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR (TM)) 5th edn, Vol. 1120 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification Of Mental And Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions And Diagnostic Guidelines. Vol. 1 (World Health Organization, 1992).

World Health Organization. ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (World Health Organization, 2022).

Caroleo, M. et al. Brain-behavior-immune interaction: serum cytokines and growth factors in patients with eating disorders at extremes of the body mass index (BMI) spectrum. Nutrients 11, 1995 (2019).

Dalton, B. et al. Inflammatory markers in anorexia nervosa: an exploratory study. Nutrients 10, 1573 (2018).

Dalton, B. et al. A longitudinal analysis of cytokines in anorexia nervosa. Brain Behav. Immun. 85, 88–95 (2020).

Roubalova, R. et al. Altered serum immunological and biochemical parameters and microbiota composition in patients with an during realimentation. Front Nutr. 8, 680870 (2021).

Ruiz-Guerrero, F. et al. Oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways in female eating disorders and borderline personality disorders with emotional dysregulation as linking factors with impulsivity and trauma. Psychoneuroendocrinology 158, 106383 (2023).

Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M. et al. Expression of immune-related proteins and their association with neuropeptides in adolescent patients with anorexia nervosa. Neuropeptides 91, 102214 (2022).

Stata Statistical Software: Release 18 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, 2023).

DerSimonian, R. & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clin. Trials 7, 177–188 (1986).

Duval, S. & Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56, 455–463 (2000).

van Lissa, C. J. Package ‘metaforest’. https://cjvanlissa.r-universe.dev/builds (2024).

Agnello, E. et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha and oxidative stress as maintaining factors in the evolution of anorexia nervosa. Eat. Weight Dis. Bulimia Obesity 17, e194–e199 (2012).

Ahrén-Moonga, J. et al. Levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 in severely ill patients with eating disorders. Neuropsychobiology 63, 8–14 (2010).

Allende. et al. Immunodeficiency associated with anorexia nervosa is secondary and improves after refeeding. Immunology 94, 543–551 (1998).

Amerio, A. et al. Dysfunction of inflammatory pathways and their relationship with anti-hypothalamic autoantibodies in patients with anorexia nervosa. Nutrients 15, 2199 (2023).

Brambilla, F., Bellodi, L., Brunetta, M. & Perna, G. Plasma concentrations of interleukin-1β, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology 23, 439–447 (1998).

Brambilla, F., Monti, D. & Franceschi, C. Plasma concentrations of interleukin-1-beta, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and of their soluble receptors and receptor antagonist in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 103, 107–114 (2001).

Campanile, A. A., Eckel, L. A. & Keel, P. K. Elevated interleukin-6 in women with binge-eating spectrum disorders. Int. J. Eat Disord. 57, 1510–1517 (2024).

Caso, J. R. et al. Dysfunction of inflammatory pathways in adolescent female patients with anorexia nervosa. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 96, 109727 (2020).

Corcos, M. et al. Cytokines and anorexia nervosa. Biopsychosocial Sci. Med. 63, 502–504 (2001).

Dolezalova, R. et al. Changes of endocrine function of adipose tissue in anorexia nervosa: comparison of circulating levels versus subcutaneous mRNA expression. Clin. Endocrinol. 67, 674–678 (2007).

Elegido, A. et al. Adipokines, cortisol and cytokine alterations in recent onset anorexia nervosa. A case-control study. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. (Engl Ed) 66, 571–578 (2019).

Gabriel, T. et al. Association of gut-specific non-inflammatory T lymphocytes with chronic anorexia nervosa and constitutional thinness. Eur. Eat Disord. Rev. 31, 76–86 (2023).

Jiskra, J. et al. Serum leptin levels and soluble leptin receptors in female patients with anorexia nervosa. Casopis. Lekaru. Ceskych. 139, 660–663 (2000).

Karczewska-Kupczewska, M. et al. Circulating interleukin 6 and soluble forms of its receptors in relation to resting energy expenditure in women with anorexia nervosa. Clin. Endocrinol. 79, 812–816 (2013).

Karczewska-Kupczewska, M. et al. Hyperinsulinemia acutely increases serum macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 concentration in anorexia nervosa and obesity. Clin. Endocrinol. 76, 46–50 (2012).

Keeler, J. L. et al. Longitudinal changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) but not cytokines contribute to hippocampal recovery in anorexia nervosa above increases in body mass index. Psychol Med. 54, 2242–2253 (2024).

Křížová, J. et al. Adiponectin and resistin gene polymorphisms in patients with anorexia nervosa and obesity and its influence on metabolic phenotype. Physiol. Res. 57, 539–546 (2008).

Krizova, J. et al. Soluble leptin receptor levels in patients with anorexia nervosa. Endocrine Res. 28, 199–205 (2002).

Misra, M. et al. Uncoupling of cardiovascular risk markers in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J. Pediatrics 149, 763–769.e761 (2006).

Nagata, T., Yamada, H., Iketani, T. & Kiriike, N. Relationship between plasma concentrations of cytokines, ratio of CD4 and CD8, lymphocyte proliferative responses, and depressive and anxiety state in bulimia nervosa. J. Psychosomatic Res. 60, 99–103 (2006).

Nakai, Y., Hamagaki, S., Takagi, R., Taniguchi, A. & Kurimoto, F. Plasma concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and soluble TNF receptors in patients with anorexia nervosa. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84, 1226–1228 (1999).

Nakai, Y., Hamagaki, S., Takagi, R., Taniguchi, A. & Kurimoto, F. Plasma concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and soluble TNF receptors in patients with bulimia nervosa. Clin. Endocrinol. 53, 383–388 (2000).

Nogueira, J. et al. Specific adipocytokines profiles in patients with hyperactive and/or binge/purge form of anorexia nervosa. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 840–844 (2010).

Ostrowska, Z. et al. Selected pro-inflammatory cytokines, bone metabolism, osteoprotegerin, and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand in girls with anorexia nervosa. Endokrynol. Pol. 66, 313–321 (2015).

Ostrowska, Z. et al. TGF-β1, bone metabolism, osteoprotegerin, and soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand in girls with anorexia nervosa. Endokrynol. Pol. 67, 493–500 (2016).

Pomeroy, C. et al. Role of interleukin-6 and transforming growth factor-β in anorexia nervosa. Biol. Psychiatry 36, 836–839 (1994).

Roczniak, W. et al. Serum interleukin 15 in anorexia nervosa: comparison to normal weight and obese girls. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 21, 203–211 (2020).

Ruiz Guerrero, F. et al. Low levels of proinflammatory cytokines in a transdiagnostic sample of young male and female early onset eating disorders without any previous treatment: a case control study. Psychiatry Res. 310, 114449 (2022).

Shimizu, T. et al. Factors involved in the regulation of plasma leptin levels in children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Pediatrics Int. 47, 154–158 (2005).

Tabasi, M. et al. Socio-demographic characteristics, biochemical and cytokine levels in bulimia nervosa candidates for sleeve gastrectomy. Arch. Iran Med. 23, 23–30 (2020).

Terra, X. et al. Adipocytokine levels in women with anorexia nervosa. Relationship with weight restoration and disease duration. Int. J. Eating Disord. 46, 855–861 (2013).

Vaisman, N. et al. Changes in cytokine production and impaired hematopoiesis in patients with anorexia nervosa: the effect of refeeding. Cytokine 26, 255–261 (2004).

Víctor, V. M. et al. Involvement of leucocyte/endothelial cell interactions in anorexia nervosa. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 45, 670–678 (2015).

Yasuhara, D. et al. High mobility group box 1 and refeeding-resistance in anorexia nervosa. Mol. Psychiatr. 12, 976–977 (2007).

Caldas, N. D. et al. Binge eating disorder, frequency of depression, and systemic inflammatory state in individuals with obesity-a cross sectional study. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 66, 489–497 (2022).

Germain, N. et al. Interleukin-7 plasma levels in human differentiate anorexia nervosa, constitutional thinness and healthy obesity. PLoS ONE 11, e0161890 (2016).

Monteleone, P. et al. Immunoendocrine findings in patients with eating disorders. Neuropsychobiology 40, 115–120 (1999).

Solis, B. et al. The effect of fermented milk on interferon production in malnourished children and in anorexia nervosa patients undergoing nutritional care. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 56, S27–S33 (2002).

Xu, C. et al. C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in people with eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 181, 653−662 (2024).

Schindler, R. et al. Correlations and interactions in the production of interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in human blood mononuclear cells: IL-6 suppresses IL-1 and TNF. Blood 75, 40−7 (1990).

Matthys, P., Mitera, T., Heremans, H., Van Damme, J. & Billiau, A. Anti-gamma interferon and anti-interleukin-6 antibodies affect staphylococcal enterotoxin B-induced weight loss, hypoglycemia, and cytokine release in D-galactosamine-sensitized and unsensitized mice. Infect. Immun. 63, 1158–1164 (1995).

Kistner, T. M., Pedersen, B. K. & Lieberman, D. E. Interleukin 6 as an energy allocator in muscle tissue. Nat. Metab. 4, 170–179 (2022).

Muñoz-Cánoves, P., Scheele, C., Pedersen, B. K. & Serrano, A. L. Interleukin-6 myokine signaling in skeletal muscle: a double-edged sword?. FEBS J. 280, 4131–4148 (2013).

Carson, W. E. et al. Interleukin (IL) 15 is a novel cytokine that activates human natural killer cells via components of the IL-2 receptor. J. Exp. Med. 180, 1395–1403 (1994).

Khalafi, M. et al. Interleukin-15 responses to acute and chronic exercise in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 14, 1288537 (2024).

Wu, X. et al. Interleukin-15 affects serotonin system and exerts antidepressive effects through IL15Rα receptor. Psychoneuroendocrinology 36, 266–278 (2011).

Di Castro, M. A. et al. Interleukin-15 alters hippocampal synaptic transmission and impairs episodic memory formation in mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 115, 652–666 (2024).

Winer, H. et al. IL-7: comprehensive review. Cytokine 160, 156049 (2022).

Bowers, T. K. & Eckert, E. Leukopenia in anorexia nervosa: Lack of increased risk of infection. Arch. Int. Med. 138, 1520–1523 (1978).

Saito, H., Nomura, K., Hotta, M. & Takano, K. Malnutrition induces dissociated changes in lymphocyte count and subset proportion in patients with anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eating Disord. 40, 575–579 (2007).

Larsson, A. et al. The body mass index (BMI) is significantly correlated with levels of cytokines and chemokines in cerebrospinal fluid. Cytokine 76, 514–518 (2015).

Oertelt-Prigione, S. The influence of sex and gender on the immune response. Autoimmun. Rev. 11, A479–A485 (2012).

O’Brien, S. M. et al. Impact of gender and menstrual cycle phase on plasma cytokine concentrations. Neuroimmunomodulation 14, 84–90 (2007).

Nilsonne, G., Lekander, M., Åkerstedt, T., Axelsson, J. & Ingre, M. Diurnal variation of circulating interleukin-6 in humans: a meta-analysis. PloS ONE 11, e0165799 (2016).

Zeng, Y., Guo, Z., Wu, M., Chen, F. & Chen, L. Circadian rhythm regulates the function of immune cells and participates in the development of tumors. Cell Death Discovery 10, 199 (2024).

Zielinski, M. R. & Gibbons, A. J. Neuroinflammation, sleep, and circadian rhythms. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 853096 (2022).

D’Esposito, V. et al. Lifestyle and dietary habits affect plasma levels of specific cytokines in healthy subjects. Front. Nutr. 9, 913176 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Effects of SSRIs on peripheral inflammatory markers in patients with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 79, 24–38 (2019).

Seitz, J. et al. Long-term dynamics of serum α-MSH and α-MSH-binding immunoglobulins with a link to gut microbiota composition in patients with anorexia nervosa. Neuroendocrinology 114, 907–920 (2024).

Fetissov, S. O. & Déchelotte, P. The putative role of neuropeptide autoantibodies in anorexia nervosa. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutrition Metab. Care 11, 428–434 (2008).

Paszynska, E., Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M., Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M. & Slopien, A. Salivary alpha-amylase, secretory IgA and free cortisol as neurobiological components of the stress response in the acute phase of anorexia nervosa. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 17, 266–273 (2016).

Acknowledgements

JLK acknowledges financial support from a Medical Research Council (MRC) funded Doctoral Training Partnership stipend for commencing this project (ref: MR/N 013700/1). This study represents independent research part funded by the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the MRC, NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L.K. contributed to the conceptualization and management of the study, the database searches, the data extraction, management and curation, the formal analysis, the interpretation of results, the writing of the protocol and manuscript, and the manuscript submission; C.B. contributed to the database searches, the data extraction, management and curation, the interpretation of results, and the writing of the manuscript; H.H., J.T., B.C. and U.S. contributed to the review and editing of the final manuscript; B.D. contributed to the conceptualization and supervision of the study, the data curation, the interpretation of results and the review and editing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Francesco Bevione, Magnus Sjögren and Abbas F. Almulla for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Keeler, J.L., Bovenberg, C., Himmerich, H. et al. Cytokine concentrations in people with eating disorders: A comprehensive updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Commun Med 5, 408 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01122-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01122-z

This article is cited by

-

Endometriosis and eating disorders: epidemiology, shared neurobiology, and clinical implications

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2026)