Abstract

Background:

In benign tumors with potential for malignant transformation, sampling error during pre-operative biopsy can significantly change patient counseling and surgical planning. Sinonasal inverted papilloma (IP) is the most common benign soft tissue tumor of the sinuses, yet it can undergo malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma (IP-SCC), for which the planned surgery could be drastically different. Artificial intelligence (AI) could potentially help with this diagnostic challenge.

Methods:

CT images from 19 institutions were used to train the Google Cloud Vertex AI platform to distinguish between IP and IP-SCC. The model was evaluated on a holdout test dataset of images from patients whose data were not used for training or validation. Performance metrics of area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and F1 were used to assess the model.

Results:

Here we show CT image data from 958 patients and 41099 individual images that were labeled to train and validate the deep learning image classification model. The model demonstrated a 95.8 % sensitivity in correctly identifying IP-SCC cases from IP, while specificity was robust at 99.7 %. Overall, the model achieved an accuracy of 99.1%.

Conclusions:

A deep automated machine learning model, created from a publicly available artificial intelligence tool, using pre-operative CT imaging alone, identified malignant transformation of inverted papilloma with excellent accuracy.

Plain Language Summary

Planning for surgery to remove a tumor, and the preoperative counseling a surgeon gives to the patient, can be very different, depending on if that tumor is cancerous or non-cancerous. Unfortunately, it can be difficult to always know which it is before actually getting to the operating room. Here we show the utilization of a publicly available platform, Google Vertex AI, and pre-operative computed tomography (CT) imaging of patients from nineteen separate institutions, to identify cancerous transformation of a non-cancerous tumor with excellent accuracy in a specific tumor type. An automated machine learning (AutoML) model, created from a publicly available artificial intelligence tool, by physicians with little coding background, was able to differentiate between these types of tumors with better accuracy than previously published rates from experts. This tool could serve to better inform surgical planning for tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are dozens of benign tumor types that occur throughout the body that have the potential for malignant transformation. Adenomas, meningiomas, lipomas, fibromas, endometriomas, chordomas, and more are examples. When these tumors are adjacent to critical structures, the ability to know whether the tumor is truly benign or malignant before surgical resection, which may need to remove critical structures in order to actually save a patient’s life in the setting of cancer, is paramount. Inverted papilloma (IP) is the most common benign soft tissue tumor of the sinonasal cavity. With a 15% chance of recurrence after surgical resection and a 7-10% chance of conversion to malignancy (inverted papilloma associated squamous cell carcinoma, IP-SCC), this benign tumor has been treated with the respect and care typically afforded to cancer1. Early identification of malignant transformation is crucial, influencing both treatment strategy and patient counseling. However, accurate pre-operative diagnosis of IP-SCC presents a significant challenge. Conventional modalities such as in-office biopsies, computed tomography (CT) scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) yield valuable results, however, challenges persist, particularly for less-experienced radiologists and surgeons, in accurately diagnosing IP-SCC through these methods.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI)-based automated medical imaging diagnosis has revolutionized diagnostic accuracy, addressing concerns related to human error. By training diverse algorithms on annotated datasets, machine learning (ML) equips them to identify patterns and features relevant to various stages of medical conditions, thereby facilitating the automatic classification of previously unseen images.

Within all fields of medicine and surgery there is growing interest in harnessing the potential of AI to enhance diagnosis and management of different pathologies, and the question of differentiating IP from its malignant transformation is one that could carry significant clinical benefit.

Previously, AI-based diagnostic systems have demonstrated increasing accuracy in distinguishing between IP and IP-SCC when incorporating MRI with multiple demographic patient and tumor factors2,3,4, and differentiating IP from nasal polyps using endoscopic images5,6. Unfortunately, many communities around the world, and even within the United States, do not have direct access to such costly diagnostic tools as MRI and endoscopy. However, most communities now have access to CT.

Our study aims to harness AI technology via an automated machine learning (AutoML) algorithm to develop a prediction model to differentiate between IP and IP-SCC to increase the accurate diagnosis and treatment of these lesions.

Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of 19 institutions around the world, led by the IRB of Stanford University School of Medicine. Due to the nature of the study as a diagnostic review, the requirement for written informed consent was waived. Reporting follows the TRIPOD guidelines7.

Dataset

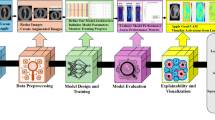

Patients with pathology-proven diagnoses of either IP or IP-SCC were retrospectively identified from 19 academic centers, totaling 958 cases (878 IP and 80 IP-SCC). From these, 41,099 CT scan slices were extracted, encompassing axial, coronal, and sagittal planes (Fig. 1). These images were labeled based on pathology results (meaning final pathology based on complete tumor resection) and used to train a two-dimensional (2D) image classification model using the Google Cloud Vertex AI AutoML platform. The dataset included a broad range of scanner types, Slice thicknesses ranged from 0.5 mm to 1 mm, with voxel sizes of approximately 0.5–0.6 mm × 0.5–0.6 mm, and imaging protocols varied, reflecting real-world heterogeneity. No image resizing or segmentation was performed to preserve original imaging characteristics and improve generalizability across diverse scan types.

Image processing

The extracted CT scans were anonymized and stored as de-identified Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) files, which were subsequently converted to JPEG format prior to model training. All images were used in their raw form, with no preprocessing steps applied for artifact removal, noise reduction, or intensity normalization. No windowing was performed; the original intensity values were preserved. Additionally, there was no manual segmentation or annotation of tumor regions—full-frame slices, including both tumor and normal anatomy, were utilized. Labels were applied at the scan (exam) level based on final pathology-confirmed diagnoses of IP or IP-SCC.

To simulate real-world conditions, all axial, coronal, and sagittal slices from the full sinus CT scans—spanning from the mandible to the skull base — were included, regardless of whether a tumor was visible in a specific slice. The dataset encompassed considerable heterogeneity in scanner types, voxel sizes, imaging protocols, and slice thicknesses across 19 academic institutions. Images were not resized manually; instead, Vertex AI AutoML automatically standardized image dimensions internally during training. No data augmentation techniques (e.g., rotation, flipping, or contrast adjustment) were applied. This approach preserved the real-world variability of CT imaging and allowed the model to learn under practical clinical conditions.

Model training

The model was developed using the Google Cloud Vertex AI AutoML Vision platform for image classification. JPEG-formatted CT slices were labeled based on final pathology-confirmed diagnoses of IP or IP-SCC. All labeled images were uploaded to the AutoML platform, which automatically performed a random split of the dataset into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) subsets prior to model training (Table 1). This ensured that each image was used exclusively in one subset, preventing overlap between training, validation, and testing phases.

Model architecture selection and hyperparameter optimization were performed automatically through the platform’s proprietary neural architecture search. Training was configured for a maximum of 16 node hours, with a target prediction latency of 200–300 milliseconds. Input images were used in their original resolution without resizing. Image standardization and pre-processing were managed internally by the platform, allowing the model to accommodate variability in image dimensions and voxel intensity.

The dataset was imbalanced (878 IP vs. 80 IP-SCC cases), and Vertex AI AutoML does not support manual implementation of class weighting or resampling. The model was trained on that portion of the dataset without manual adjustments.

Metadata, including training configuration and evaluation metrics, was retained within the Vertex AI environment (Project ID: cogent-sweep-424404-f4) for reproducibility.

Statistical analysis

Model performance was evaluated using metrics automatically generated by the Google Cloud Vertex AI AutoML image classification platform. These included area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC), sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, precision (positive predictive value), negative predictive value (NPV), and the F1 score (harmonic mean of precision and recall). Confusion matrices were used to derive true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives from test set predictions. No manual statistical testing was performed, as the model was evaluated entirely using the internal validation and test sets managed by the AutoML framework. Reporting follows the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) guidelines7.

Results

Patient cohort

The study involved a cohort comprising 958 patients. 878 individuals had benign IP and 80 had IP-SCC. Demographic details of the patients are presented in Table 2.

In this study cohort, a comprehensive collection of 41,099 CT scan cuts was analyzed. This encompassed 35,216 images representing benign IP and 5,883 images depicting IP-SCC. The trained model demonstrated strong performance, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) of 99.8%. Precision of 99.2% was observed at a confidence threshold 0.5 (Fig. 2). The model exhibited a sensitivity rate of 95.8% in correctly differentiating IP-SCC cases from IP, while specificity remained high at 99.7%. (Fig. 3). Overall, the model achieved an accuracy of 99.1%, with an F1 Score of 97%, underscoring its efficacy in discerning between IP and IP-SCC. With such strong results, care was taken to double and triple check against over-fitting of the model, but the results held up to this scrutiny.

(Left) Precision–Recall Curve showing the model’s ability to balance precision and recall across all thresholds. The high values across the curve demonstrate excellent classification performance. (Right) Precision and Recall vs. Confidence Threshold illustrating how precision and recall change with increasing model confidence. The model achieves optimal performance at a confidence threshold around 0.5, where both precision and recall remain near peak values.

Confusion matrix heatmap of test classification performance for the trained model. The model correctly classified 99.7% of inverted papilloma (IP) cases and 95.8% of inverted papilloma with squamous cell carcinoma (IP-SCC) cases. Misclassification rates were low, with 0.3% of IP cases incorrectly labeled as IP-SCC, and 4.2% of IP-SCC cases misclassified as IP. These results demonstrate the model’s strong diagnostic accuracy.

Discussion

In this multi-institutional study, we developed and validated an AutoML model using preoperative CT images to distinguish between IP and inverted IP-SCC. The model demonstrated excellent performance, achieving an AUC of 99.8%, with high sensitivity (95.8%), specificity (99.7%), precision (99.2%), and an overall accuracy of 99.1%. These findings support the feasibility of using an accessible AI tool to aid in the noninvasive diagnosis of sinonasal tumors, potentially improving surgical planning and patient care, especially in settings where biopsy or advanced imaging may be limited.

The findings of our study align with the growing body of research that underscores the potential of AI in enhancing diagnostic accuracy of tumor diagnosis, but with the recent advent and rapid evolution of AutoML, this accuracy and prediction capability now far surpasses anything seen prior8,9,10,11.

Several key studies laid the groundwork for the current investigation. One study provided evidence for the value of human experts using MRI-based radiomics in distinguishing IP from IP-SCC, achieving a high AUC with a combined model of radiomic and morphological features12. However, in that study, the predictive value of different parameters was able to reach the high level found in this study only when sacrificing either sensitivity or specificity, but the predictive capability could not accommodate both. Following that, another study explored the use of traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to differentiate IP from IP-SCC based on MRI images. However, their sensitivity and specificity were lower than the previously reported human expert capability, and also lower than what this study achieved with only CT images3. An investigation then ensued to compare the previously used traditional deep learning model with an AutoML using a much smaller and different dataset than used herein for this study (an MRI data set from only two institutions). A comparison of human expert physician (radiology and otolaryngology) assessment of that same data set, which demonstrated a sensitivity of 78%, specificity of 100%, and overall accuracy of 89% to the AutoML which, with that smaller MRI dataset demonstrated a sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 92% and overall accuracy of 84%, revealed how important “experience” is for success to both humans and AI algorithms. The human experts had the benefit of years of reading thousands of prior imaging exams and applying that knowledge to the new dataset, whereas the AutoML only had the extremely small number of images to learn from ref.12.

With the knowledge gained from those studies and the recognition that a larger dataset would allow for greater accuracy, our study builds on these findings by utilizing an international, multi-institutional dataset of CT images, encompassing a wide range of imaging parameters and conditions. This diverse dataset contributes to the generalizability of our AI model, which demonstrated an AUC of 99.8%, precision and recall rates of 99.2%, and an overall accuracy rate of 99.1%. These metrics surpass that of the previous studies, indicating the potential for this approach to provide superior diagnostic performance. It is important to note that while this model can distinguish IP from IP-SCC, it is not “predicting” transformation, a step further which we could hope to aspire to in the future.

One of the significant strengths of our study is its international multicenter nature, involving 19 institutions from around the world and the large number of CT images with varying dimensions, thicknesses, and voxel sizes. This variability mirrors real-world clinical conditions more closely than studies that rely on standardized or homogeneous datasets. The ability of our AI model to maintain high accuracy despite differences in image quality and parameters is particularly noteworthy. In real-life clinical settings, images are often taken using different machines and protocols, leading to variability in image characteristics. As a result, our model’s high performance across such a diverse dataset suggests that it is well-suited for real-world application and could potentially reduce the need for invasive procedures like biopsies and bring high-level diagnostic accuracy to communities currently lacking in this ability.

Another strength of this study that contributes to its wide applicability is the diverse dataset provided by the multi-institutional nature of the study. This diversity enhanced the model’s ability to generalize across different patient populations and imaging conditions. Also, the use of a large dataset with over 41,000 CT scan slices provides a solid foundation for training and validating the AI model, reducing the likelihood of overfitting and improving the model’s reliability. There has been significant study and discussion on the need for deep and diverse data sets that draw from populations around the world, if we are to hope to develop AI algorithms that are truly representative and thus accurate for all patients13. It is only in recent years that researchers have discovered that information long held as true and applied across all populations in medicine only hold true for the majority population included in prior studies, for example, myocardial infarction symptoms differing between male and female populations14. If we are to hope and expect that AI will do a better job than humans in prediction, whether in radiology or other domains, we must acknowledge that such an outcome depends on scientists feeding the highest level of data possible into these algorithms, which is heavily dependent on how truly representative that data is. The international collaboration of our study is a major strength of this research, as it allows for this diversity of included data, and our algorithm is more accurate and widely useful because of it.

Our study highlights the transformative potential of using AutoML in developing AI models. The transition to AutoML marks a pivotal shift in methodology, as evidenced by a recent comparative analysis involving Google Vertex AI (AutoML) and the traditional All-Net neural network15. Using the same dataset from two institutions, the AutoML model exhibited an overall accuracy rate surpassing that of the traditional All-Net model without the need for specialized graduate-level education in artificial intelligence. The AutoML models demanded no code, allowing us to test numerous algorithms simultaneously within a brief timeframe. This capability enabled us to swiftly pinpoint promising model algorithm classes for further development, a process that is typically time-intensive in traditional machine learning. Moreover, the user-friendly nature of AutoML makes it accessible to healthcare practitioners without extensive programming skills, paving the way for wider adoption in clinical settings.

In addition to its technical simplicity, AutoML holds clinical promise. Given the risk of sampling error in IP with focal malignant transformation, a noninvasive, full-volume imaging assessment via AI may detect malignancy that limited biopsies could miss. AutoML can therefore serve as a valuable adjunct to surgical planning. One of the key goals of integrating AI into clinical workflows is to reduce the number of steps toward diagnosis and treatment. By decreasing reliance on invasive procedures such as biopsies—particularly when technically difficult, risky, or inaccessible—AutoML may help streamline prediction.

Despite the strong performance metrics of the model, certain limitations merit discussion. Although the model achieved a high sensitivity of 95.8%, approximately 4.2% of IP-SCC cases were misclassified as benign IP, representing false negatives. This is a critical concern in clinical practice, where missing a malignant tumor could delay oncologic referral or alter surgical management. To address this, future work will explore strategies such as ensemble learning, integration of additional modalities (e.g., MRI, clinical history, genomics), and cost-sensitive training approaches that prioritize recall for malignant cases. Additionally, incorporating a mechanism into the AutoML pipeline to favor malignant classification in cases of diagnostic uncertainty may further reduce the false negative rate. This study represents a step toward addressing these challenges, with the ultimate goal of increasing the precision, safety, and clinical utility of AI-based diagnostic tools.

Another important consideration for clinical translation is model interpretability. As a “black box” deep learning system, Google Vertex AI AutoML does not provide saliency maps, feature attribution, or attention visualizations, limiting insight into the features driving predictions. It also does not allow us to know if specific potential confounding variables such as tumor size, calcification, etc. were the factors being used in diagnosis. Nonetheless, the model demonstrated strong performance (sensitivity 95.8%, specificity 99.7%, AUC 99.8%), suggesting it learned truly meaningful radiologic patterns, and superceded prior human interpretation studies of this type of tumor – even with the human study utilizing MRI, an examination traditionally thought to bring much greater detail and information about soft tissue structures. Likely features associated with malignancy include bone erosion, irregular or infiltrative borders, heterogeneous enhancement, and extension beyond the sinonasal cavity—patterns that may be subtle or overlooked by the human eye. While this autonomy enables robust classification, the lack of transparency and lack of head-to-head comparison of human interpretation may limit clinician trust. Future work will incorporate explainable AI (XAI) tools, such as Grad-CAM, to improve understanding of model outputs and better align them with clinical reasoning, as well as conducting prospective reader studies comparing radiologist and AI performance on the same dataset.

This study has several other limitations, including its retrospective design and potential selection bias. The use of Google Vertex AI AutoML introduces additional constraints typical of no-code platforms—limited control over model architecture, hyperparameters, and source code—as well as reduced algorithmic transparency and customization. Furthermore, manual implementation of class weighting or resampling was not supported, resulting in model training on an imbalanced dataset (878 IP vs. 80 IP-SCC cases), which may have biased predictions toward the majority class. Although AutoML may internally address class imbalance through proprietary optimization processes, these mechanisms are not user-accessible or transparently documented. Future efforts will focus on balancing the dataset, applying weighted loss functions, and restructuring data using patient-level splitting to improve generalizability and reduce bias. Additionally, this study employed internal validation using a randomly split multi-institutional dataset; however, external validation on an independent cohort was not performed. Future studies are needed to validate the model’s generalizability across entirely separate patient populations and clinical settings.

As in any retrospective study, limitations regarding potential selection bias and lack of ability to control for confounders exist. However, having each institution simply include all patients with IP or IP-SCC tumors seen within the prior ten years, if all necessary imaging and data points were available, protected against selection bias as much as possible.

In addition to technical limitations, practical barriers to implementation also warrant consideration. Hosting and running models on commercial cloud-based platforms such as Google Vertex AI incurs recurring infrastructure costs, including compute resources, storage, and maintenance. These expenses pose significant challenges for widespread transmission and adoption. Moreover, reliance on proprietary infrastructure may hinder scalability and long-term sustainability.

Although our initial goal was to develop a free and globally accessible diagnostic tool, the current deployment model presents financial constraints that limit broader availability. We are actively engaging with platform representatives to explore alternative solutions, such as cost-sharing arrangements or open-access hosting options, to enhance accessibility. We may eventually need to try and replicate this model with the help of our computer science and artificial intelligence expert colleagues in academia with institutional hosting support.

Future work may include a formal cost-benefit analysis comparing cloud-based deployment with on-premises or open-source alternatives. Additionally, exploring hybrid deployment models—such as edge computing or federated learning—may offer cost-effective and scalable solutions for expanding access while maintaining robust performance.

Ultimately, our goal is to advance the field of medical AI by improving diagnostic accuracy, reducing procedural invasiveness, and democratizing access to advanced technology. While AutoML represents a significant step forward, its implementation in clinical practice must be carefully managed, considering both its advantages and constraints. Future research should focus on reducing class imbalance, enhancing model interpretability, validating performance in prospective clinical trials, and incorporating multimodal data—such as genomics, proteomics, clinical history, and MRI—to further improve diagnostic precision. In addition, developing cost-effective deployment strategies and evaluating real-world implementation in diverse healthcare settings will be essential to ensure accessibility, scalability, and clinical adoption.

Finally, although using AutoML models in the clinical setting can introduce apprehension and hesitancy in physicians, it is imperative that physicians without engineering or technical coding background begin familiarizing themselves with these types of widely available tools, as they will only improve in accuracy over time, and those unfamiliar or unwilling to adapt will find themselves and their patients at a significant diagnostic disadvantage16.

Conclusion

A deep AML model, created from a publicly available AI tool using pre-operative CT imaging alone, identified malignant transformation of inverted papilloma with excellent accuracy. By leveraging a large, international, multi-center dataset and embracing the inherent variability in clinical imaging, we have developed a model that is reliable, widely applicable, and highly accurate. This work paves the way for broader clinical adoption of AI-based diagnostic tools across all medical specialties, potentially transforming patient care by reducing the reliance on invasive procedures and enhancing early detection and treatment planning.

Data availability

The Data Sharing agreement between institutions that provided patient images and data prohibits the sharing of the datasets and images outside our institution.

References

Kuan, E. C. et al. International consensus statement on allergy and rhinology: sinonasal tumors. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 14, 149–608 (2024).

Gu, J. et al. MRI radiomics-based machine learning model integrated with clinic-radiological features for preoperative differentiation of sinonasal inverted papilloma and malignant sinonasal tumors. Front Oncol. 12, 1003639 (2022).

Liu, G. S. et al. Deep learning classification of inverted papilloma malignant transformation using 3D convolutional neural networks and magnetic resonance imaging. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 12, 1025–1033 (2022).

Ramkumar, S. et al. MRI-based texture analysis to differentiate sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma from inverted papilloma. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 38, 1019–1025 (2017).

Girdler, B. et al. Feasibility of a deep learning-based algorithm for automated detection and classification of nasal polyps and inverted papillomas on nasal endoscopic images. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 11, 1637-1646 (2021).

Tai, J. et al. Deep learning model for differentiating nasal cavity masses based on nasal endoscopy images. BMC Med. Inform. Decis Mak. 24, 145 (2024).

Collins, G. S. et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD Statement. 2015. BMC Med 13.

Radak, M., Lafta, H. Y. & Fallahi, H. Machine learning and deep learning techniques for breast cancer diagnosis and classification: a comprehensive review of medical imaging studies. J. Cancer Res Clin. Oncol. 149, 10473–10491 (2023).

Bajaj, A. S. & Chouhan, U. A review of various machine learning techniques for brain tumor detection from MRI images. Curr. Med Imaging 16, 937–945 (2020).

Misera, L., Müller-Franzes, G., Truhn, D. & Kather, J. N. Weakly Supervised Deep Learning in Radiology. Radiology 312, e232085 (2024).

Mese, I., Inan, N. G., Kocadagli, O., Salmaslioglu, A. & Yildirim, D. ChatGPT-assisted deep learning model for thyroid nodule analysis: beyond artifical intelligence. Med. Ultrason. 25, 375–383 (2023).

Yan, C. H. et al. Imaging predictors for malignant transformation of inverted papilloma. Laryngoscope 129, 777–782 (2019).

Baumgart, D. C. An intriguing vision for transatlantic collaborative health data use and artificial intelligence development. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 19 (2024).

Shi, H. et al. Sex Differences in Prodromal Symptoms and Individual Responses to Acute Coronary Syndrome. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 35, 545–549 (2020).

Hosseinzadeh, F. et al. Comparative analysis of traditional machine learning and automated machine learning: advancing inverted papilloma versus associated squamous cell carcinoma diagnosis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 14, 1957–1960 (2024).

AI-generated content enhanced computer-aided diagnosis model for thyroid nodules: a ChatGPT-style assistant, arXiv, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.02401 (2024).

Acknowledgements

N.D.A.: consultant/advisory board for: 3-D Matrix, Acclarent, Optinose J.A.A:. consultant for Medtronic and Optinose, equity and consultant GlycoMira, speaker for Glaxo Smith Kline, advisory board Sanofi. R.C.: consultant for Optinose, Sanofi/Regeneron and Lyra Therapeutics. M.T.C:. consultant for SoundHealth, Korust Co. P.G.C.: consultant for Medtronic, speaker for Optinose and GlaxoSmithKline, research funding from Aerin Medical C.D.: consultant for Myelin Healthcare. T.S.E.: research support from Sanofi-Aventis US LLC and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. M.F.: consultant for Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca. M.G.: consultant for: Medtronic, Stryker. D.A.G.: consultant for Pocket Naloxone, P.H.H.: consultant for: Medtronic, Stryker; Equity in SoundHealth, J.V.N.: consultant for: Aerin Medical, SoundHealth; Equity in SpirAir Inc, J.N.P.: consultant/advisory board for: 3-D Matrix, Acclarent, Optinose, A.J.P.: consultant for Medtronic, Tissium, Fusetec, speaker’s bureau Sequiris, GSK, Sanofi, equity in Chitogel, J.R.: consultant for Storz, Spirair, Equity in SoundHealth, Z.M.P.: consultant/advisory board for: Medtronic, Dianosic, Optinose, Mediflix, ConsumerMedical; Equity in Olfera Therapeutics, SoundHealth, Wyndly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.H. contributed to data collection, data curation, data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. G.L. contributed to data collection, data curation and editing and revising the manuscript. E.T., A.M., A.Y., D.K., M.F., L.L., S.A.H., N.A., J.A.A., K.A., N.B., M.C., R.C., M.T.C., P.G.C., D.Y.C., C.R.C., N.C., C.M.C., J.M.D., A.D.S., C.D., D.D., S.E., T.S.E., J.B.F., M.G., C.G., S.G., J.W.G., D.A.G., R.J.H., A.H., P.H.H., A.M.I., N.D.K,. M.A.K., D.K.L., A.L., L.H.L., R.L., C.h.M., C.o.M., E.D.M., J.V.N., E.P.H., J.N.P., V.C.P., A.J.P., J.R., P.S., R.S., M.S., E.S., A.S., A.T., J.H.T., S.X.W., S.K.W., B.A.W., P.J.W. contributed to data collection, data curation and editing and revising the manuscript. Z.M.P. contributed to conceptualization of study design, data curation and editing and revising the manuscript. All authors take responsibility for the accuracy of the data presented herein.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Jessica Maldonado-Mendoza, Joana Cristo Santos and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosseinzadeh, F., Liu, G., Tsai, E. et al. Utilizing a publicly accessible automated machine learning platform to enable diagnosis before tumor surgery. Commun Med 5, 419 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01134-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01134-9