Abstract

Background

The long-term impact of COVID-19 vaccination on post-acute COVID-19 symptoms and associated quality of life (QoL) changes remains incompletely described. This study aimed to explore the impact of the timing of COVID-19 priming and booster doses, on reporting long COVID symptoms and associated QoL changes.

Methods

Individuals who had PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 processed in government hospitals in Northern Israel between 15th March 2021 and 15th June 2022 were invited to answer serial online surveys collecting information on SARS-CoV-2 infection, vaccination status and post-acute symptoms every 3-4 months for two years. Participants were categorized into groups based on the number of doses received prior to infection. We compared these groups over time in terms of reporting post-COVID symptom clusters and QoL, using population-average and mixed-effects regression models, respectively.

Results

A total of 4809 individuals are enrolled and respond to up to five follow-up surveys. Of these, 1377 (28.61%) report a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, while 3432 (71.39%) report a negative result. After adjustment for potential confounders, receiving at least three COVID-19 vaccine doses prior to infection is associated with a 34% reduction in the likelihood of reporting at least one long COVID symptom cluster compared to being unvaccinated (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.66, p = 0.022). Pre-infection vaccination is also associated with higher quality of life (QoL) scores (β = 0.07, p < 0.001). The estimated vaccine effectiveness of three pre-infection doses against long COVID over a two-year period is 26.5% (95% CI: 10.8–39.4). This protective effect remains stable over time. In contrast, vaccination received after infection shows no association with long COVID symptoms or QoL outcomes.

Conclusions

Receiving at least three COVID-19 vaccine doses prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection provides a sustained protective effect against long COVID and its negative impact on quality of life for at least two years. The longer-term durability of this protection, the role of reinfection, and the influence of emerging viral variants remains to be investigated.

Plain language summary

Vaccination has played a key role in protecting people from COVID-19, but its impact on long-term symptoms or long COVID has been less clear. In this study, we followed over 4800 individuals in Northern Israel for up to two years to understand how COVID-19 vaccination affects the risk of developing long COVID and changes in quality of life. We found that individuals who received at least three vaccine doses before getting infected were less likely to report long COVID symptoms and had better quality of life. In contrast, vaccination after infection showed no benefit. These findings suggest that timely vaccination offers protection against long COVID, reinforcing the importance of staying up to date with COVID-19 boosters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Post-coronavirus disease (post-COVID) condition or long COVID is characterized by the onset of symptoms that last for at least 2 months, usually 3 months after diagnosis, and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis among individuals with a history of confirmed or probable severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection1. The symptoms include, but are not limited to, fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction, with functional impairment consequences2. Long COVID was reported to affect up to 30% of individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2, even 2 years post the initial infection3, although the most recent and precise estimates suggest a prevalence of 6–7% among adults, with low recovery rates4. The global incidence of long COVID was reported to be on an upward trajectory doubling annually from an estimated 65 million at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic to an estimated 400 million by the end of 20234. Estimating the global incidence of long COVID is a challenge due to the complexity and non-specificity of the condition: more than 200 unspecific symptoms affecting all systems of the body have been reported as attributable to long COVID5. Classification of long COVID symptoms into clusters has helped improve the specificity of case definitions6, although the pathogenesis of long COVID is still not fully elucidated. Pathophysiological changes such as micro-clotting and platelet activation have been described5,7. Hypotheses being investigated include persisting reservoirs of SARS-CoV-2 in tissues8,9, reactivation of latent pathogens such as Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and Human Herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6)10,11, immune dysregulation9 and autoimmunity12, with possibly more than one causal pathway involved13.

The effectiveness and impact of COVID-19 vaccination against infection, severe disease, and death have been extensively described14,15,16. COVID-19 vaccination plays a crucial role in preventing severe cases of disease and death from COVID-1917. The priming doses of the COVID-19 vaccine demonstrated high effectiveness in protecting against SARS-CoV-2 infection (at least with wild-type virus), hospitalizations, and deaths18. The effectiveness of the priming COVID-19 doses waned rapidly over time, further worsened by the emergence of new, more transmissible and immune-evasive SARS-CoV-2 variants19. In response to this decline, further doses of monovalent and bivalent vaccines were introduced as a measure to prolong immunity20,21,22. Recent studies of systematic reviews and meta-analyses suggest that, beyond protection against acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and its consequences, COVID-19 vaccines might offer protective effects against the onset and severity of long COVID with two and three doses reported to reduce the risk of long COVID by approximately 36% and 84%, respectively23,24.

The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against long COVID severity (as measured by impact on quality of life (QoL)), duration of protection, and optimal schedule for protection against long COVID, especially in highly infected populations, remains incompletely investigated. Accordingly, this study aims to determine how the timing and dosage of vaccination are associated with the presence of post-COVID symptoms and associated changes in QoL over a period of 2 years post-infection.

Methods

Study design and participants

We recruited participants into a longitudinal cohort by inviting to join the study individuals aged 18 years and older who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), regardless of results, and whose test was processed at one of three government hospitals in Northern Israel, namely, Ziv Medical Centre, Tzafon Medical Centre (formerly Poriya Medical Centre), and Galilee Medical Centre between March 2021 and May 202225. It is important to note that while the tests were processed in the hospital, this does not mean all patients were hospitalized and in fact most were tested in the community, with their test transported to the hospital for analysis. The last invitation to participate in the survey was sent on 9th May 2022 and the last follow-up date was until March 2023. Following recruitment and the baseline data collection, participants were invited to fill out up to five serial surveys every 4–6 months collecting information about their health, QoL, and vaccination status. Once they consented, participants received messages via the Short Message Service containing a link to an online survey available in four commonly spoken languages in Israel: Hebrew, Arabic, Russian, and English. For each survey, participants received up to three reminders for survey completion if they did not respond to the first prompt.

Measurement tools

We adapted the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium COVID-19 follow-up tool26 to the Israeli context. Relevant sections of the survey tool collect data on socio-demographic characteristics, SARS-CoV-2 infection, co-morbidities, COVID-19 vaccination status, currently experienced symptoms, and health-related QoL (HRQoL). The tool combines several validated surveys and was approved by consensus of a wide range of global experts in clinical research, infectious disease, epidemiology, and public health medicine. We piloted the localized version with 5–10 individuals in each language in which the survey was available, to ensure accuracy, simplicity, clarity, and validity.

Data sources and variables

At initial recruitment, we collected information on socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity, income, and education level), comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and COPD), COVID-19 vaccination history, and details about any acute COVID-19 episode (infection, hospitalization, and intensive care unit admission).

We categorized SARS-CoV-2-infected participants into five exposure groups according to their vaccination statuses at the time of SARS-CoV-2 infection: (i) received 1 dose prior to infection, (ii) received 2 doses prior to infection, (iii) received 3 or more doses prior to infection, (iv) unvaccinated, and (v) vaccinated after infection. Vaccination status was recorded in each serial survey, and vaccination status was updated accordingly. Separately, we calculated the amount of time elapsed between the last dose of vaccine received and infection.

Outcome groups

In each survey, participants were asked to indicate from an extensive list of symptoms that they had experienced in the week prior to the survey. Identified symptoms were then grouped into three symptom clusters we previously described based on a systematic review of the literature and a meta-analysis6: (i) a cardiorespiratory symptom cluster comprising of fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain, muscle pain, headache, and palpitations; (ii) a systemic inflammatory symptom cluster including dizziness, gastrointestinal symptoms, muscle pain, muscle weakness, hair loss, and sleep disorders; and (iii) neurological symptoms cluster including anosmia, paresthesia, headache, neuropathies, dizziness, vision and balance problems, memory problems, and poor concentration. Participants who reported experiencing at least three symptoms from at least one of the three symptom clusters 60 days or more after the initial date of infection were classified as suffering from post-COVID condition. To avoid misclassifying prolonged acute symptoms with long COVID, we excluded from the analysis the surveys returned in the first 60 days from receipt of a positive PCR test for SARS-CoV-2.

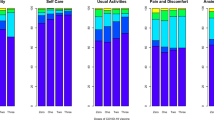

To measure HRQoL, we used the EQ-5D-5L, a widely used validated instrument for QoL measurement providing a composite QoL score based on 5 QoL dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each dimension was scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (High QoL) to 5 (low QoL)27. From the dimension scores, a composite utility index (UI) was computed according to country-specific weighted values provided by Euroqol, the instrument’s designer28. UI can vary from 1 (perfect QoL) to less than 0, implying that some health states may be worse than death. Participant’s QoL was measured each time they answered the survey.

Statistical analysis

We computed descriptive summary statistics for participant characteristics at baseline as follows: We summarized data for QoL into mean and standard deviations, and for categorical variables (ethnicity, age, income, sex, infection status, and post-COVID symptoms), we summarized data into proportions as percentages. Two-sided t tests were used to test the differences between group means and chi-square tests to compare proportions between groups. We computed the summary statistics for participants according to the number of vaccine doses received prior to infection and tabulated the results. We used the proportion of uninfected individuals with long COVID and their QoL as a comparison baseline in the descriptive analysis. Vaccine effectiveness (VE) was calculated by dividing the difference in the proportion of those reporting long COVID between unvaccinated and vaccinated, divided by the proportion of unvaccinated participants reporting long COVID (VE = (NVAR − VAR)/NVAR × 100), where NVAR is the attack rate among the unvaccinated and VAR is the attack rate among the vaccinated. Confidence intervals (CIs) around effectiveness were calculated using the Taylor series as recommended by the World Health Organization29.

To take time into account, a population-averaged model was constructed with long COVID as the binary outcome and vaccination status prior to infection as the primary exposure to determine the association between vaccination status and the likelihood of developing long COVID. Days between SARS-CoV-2 infection and answering the survey were used as the time variable. The exchangeable covariance matrix was used as it best captured the variance given the sample size and data limitations. Previous studies showed that vaccine immunogenicity did not change according to ethnicity among population groups in Israel30, we therefore did not include it in our final model. Age and gender were included as covariates in the final model to adjust for potential confounding.

Secondly, a linear mixed effects model was fitted to estimate the impact of COVID-19 vaccination on QoL in infected individuals. We chose linear mixed effects models to account for repeated measures in our data and assumed an unstructured covariance matrix due to unbalanced data panels. p Values were computed by maximum likelihood ratio tests, and p values <0.05 were considered significant. The EQ-5D index was the outcome, with time between infection and vaccination (days), and vaccination status (doses received prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection) as fixed effects in the model. Random intercepts for subject and random coefficients for time in days were included. We computed the crude and adjusted estimates for changes in mean UIs accounting for age and sex. To determine whether COVID vaccination mitigated the QoL changes among those with long COVID, we conducted a sub-analysis, as described above, but restricted it to participants who fit the criteria for post-COVID condition, as defined above. Data was managed using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using the lme4 package in R and Stata (version 17)31,32.

Informative loss to follow-up

During analysis, differential loss to follow-up was assessed by comparing baseline characteristics (age, sex, severity of initial infection, comorbidities) of those who remained in the study versus those who were lost to follow-up. We also tested for differences in mean age and proportions by sex and comorbidities between those who entered the cohort and those who completed the study.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committees of all three hospitals from which participants were recruited: Ziv Medical Centre (0007-21-ZIV), Tzafon Medical Centre (009-21-POR), and Galilee Medical Centre ethical committees (0018-21-NHR). The survey was anonymous, and invitations were sent by the hospitals: the research team had no access to participants’ identities. All participants had to sign an electronic consent form prior to accessing the survey.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the cohort

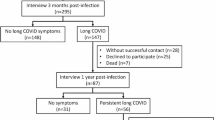

Of the 6101 individuals who responded to the survey, 169 were younger than 18 years, 123 had a single response within 60 days of infection, and 1863 did not give enough information to be included (i.e., missed vaccination status or infection status). We included 3946 (64.5% of the respondents) unique individuals who reported at least one PCR test result for SARS-CoV-2 and vaccination status. Of the 1377 who reported infection at any point, 348 were infected prior to vaccination, 123 had received 1 dose prior to infection, 215 had received 2 doses prior to infection, 311 had received 3+ doses prior to infection, and 380 were unvaccinated (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The mean number of surveys answered per participant was 1.4 (range 1–5), and the median follow-up time was 300 (interquartile range 328) days. The cohort comprised mainly community participants, with only 191 participants reporting a history of hospitalization following the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection. Of the hospitalized participants, 168 were unvaccinated and 23 had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine prior to infection. Overall, the mean age was 50.62 (SD, ±16.17) years, 59.66% of participants were female, and 75.09 % were of Jewish ethnicity at baseline, in line with the national average (Table 1). The socio-demographic characteristics of participants did not change substantially at different follow-up points (Supplementary Table 1).

Vaccination prior to infection and long COVID prevalence

Overall, 30.10% of unvaccinated infected individuals reported long COVID at any point compared with 22.10% of those who had received at least three doses. As an element of comparison, 11.10% of uninfected individuals at baseline reported symptoms compatible with our case definition of long COVID. The proportion of individuals vaccinated with 3+ doses prior to infection who reported long COVID was lower than the proportion of unvaccinated individuals who reported long COVID, as well as lower than the proportion of participants vaccinated with one or two doses who reported long COVID at all time points (Table 2).

Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination prior to infection on long COVID

Overall, VE of three doses pre-infection against reporting long COVID symptoms was 26.50% (95% CI 10.8%, 39.4%); VE for 1 and 2 doses were 8.30% (95% CI 0.77%, 15.75%), and 10.10% (95% CI 4.10%, 16.16%), respectively. Effectiveness for post-infection vaccination was −13.10% (95% CI −18.55%, −7.57%).

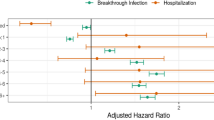

Association between COVID-19 vaccination prior to infection and long COVID outcomes

Compared to those who were unvaccinated, receiving 1 or 2 doses of vaccine pre-infection was not significantly associated with reduced long COVID reporting. However, receiving 3 doses was significantly associated with a 34% reduction in the odds of long COVID, after adjusting for age and sex (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.47–0.94, p = 0.022, Fig. 2a and Table 3). There was no difference in the proportions of reporting long COVID among those unvaccinated and those vaccinated post infection (aOR = 1.05, 95% CI: 0.75–1.47, p = 0.776). The relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and reporting of long COVID did not change over the follow-up period (p value > 0.1). In addition, there were no significant changes in the association between vaccination and long COVID after adjusting for sex and age. The timing of the last pre-infection COVID-19 vaccine dose, whether within 6 months or >6 months prior to infection, was not associated with the frequency of long COVID reporting (OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.71–1.40, p = 0.899). Never-hospitalized individuals demonstrated reduced odds of reporting post-COVID symptom clusters (aOR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.48–0.99, p = 0.044) compared to the unvaccinated (Supplementary Table 2).

Association between timing and number of COVID-19 vaccine doses with long COVID and quality of life (QoL) outcomes. Crude—(vaccinated after-(n = 380), 1-dose—(n = 123), 2-doses—(n = 215), 3 or more doses—(n = 311)). Adjusted—(vaccinated after—(n = 196), 1-dose—(n = 62), 2-doses—(n = 96), 3 or more doses—(n = 144)). a Shows the odds ratios (ORs) of reporting long COVID symptoms across vaccination groups compared to an unvaccinated reference group (not shown). Black points represent crude ORs and red points represent adjusted ORs, both with 95% confidence intervals. Individuals vaccinated with two or more doses prior to infection had lower odds of reporting long COVID symptoms compared to those unvaccinated. A dose–response pattern was observed, with the lowest odds among those who received three doses before infection. b Represents the estimated adjusted mean changes in EQ-5D QoL scores among individuals who reported post-COVID condition, stratified by vaccination status. Bar heights represent the adjusted mean change in QoL compared to the unvaccinated, with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals. Asterisks above bars indicate pairwise statistical comparisons using p values (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01). Individuals vaccinated with two or three doses before infection reported significantly better QoL than those vaccinated after infection or with only one dose. c Represents the estimated adjusted change in QoL scores for the entire cohort, regardless of symptom presence. Again, vaccination prior to infection (especially with two or more doses) was associated with significantly improved QoL outcomes. p Values indicate significance levels for each group compared to the unvaccinated group.

COVID-19 vaccination and QoL outcomes

Among participants with no history of COVID-19 infection, the baseline mean UI (QoL) was 0.88, establishing a reference for evaluating the impact of vaccination on long-term QoL. Infected participants who received three doses of vaccine pre-infection reported a UI at 0.86 or above throughout the study, closely aligning with the baseline levels of uninfected individuals (Table 2). Overall UI score for those infected and unvaccinated was 0.79, and 0.77 for those vaccinated after infection (Table 2). Overall UI for those who received one and two doses pre-infection was 0.82 and 0.84, respectively.

Compared to being unvaccinated, and after taking age and gender into account, having received two doses of COVID-19 vaccine prior to infection was associated with an increase of 0.06 points (p < 0.05) and three doses with an increase of 0.07 points (p < 0.001) on the UI scale, respectively (Table 4). This protective effect did not change over the period of the study, with the time variable remaining non-significant in the adjusted model (p = 0.690, Table 4). Vaccination post-infection was not associated with any changes in QoL (Table 4). Among never-hospitalized individuals, receipt of three vaccine doses prior to infection was associated with a modest but statistically significant improvement in QoL scores (p = 0.048, Supplementary Table 3).

Association between COVID-19 vaccination and QoL outcomes among participants with long COVID

Among individuals who reported long COVID, and after adjusting for sex, age, and time since infection, vaccination with COVID-19 vaccine prior to infection (1, 2, or 3 doses) was associated with an increase in QoL on the UI scale of 0.25, 0.16, and 0.22 (p = 0.001 or less), respectively, compared to those unvaccinated (Table 4). This association did not change over time (Table 4). Additionally, vaccination post infection had no effect on QoL (Table 4).

Discussion

Our study showed a clear protective effect of pre-infection vaccination on reporting of long COVID symptoms and associated losses of QoL: individuals who received three doses of a COVID-19 vaccine prior to infection were 34% less likely to report long COVID symptoms after infection compared to unvaccinated individuals over the 2-year follow-up period of our study. This is consistent with findings from the Norwegian cohort and other parts of Europe, where reported long COVID was 36% lower (Norway) among those who received at least 2 doses of a COVID-19 vaccine33,34. VE of three pre-infection doses against long COVID up to 2 years post infection was 26.5%. While the CI around this estimate (10–40%) is relatively wide, our findings suggest a modest but significant effect. Individuals vaccinated with two or three doses of COVID-19 vaccine pre-infection also reported a higher QoL compared to those unvaccinated. In addition, our sub-analysis restricted to individuals with long COVID suggests that, even when vaccination does not prevent long COVID, it mitigates its impact as indicated by the higher QoL among individuals with long COVID who were vaccinated pre-infection, compared to unvaccinated individuals with long COVID. It is important to note that because we focus on those infected and do not account for those uninfected whose infection was prevented by the vaccine (who by definition cannot have long COVID), the overall effect of vaccination in mitigating long COVID may be larger than reported in this study. Importantly, time was not a significant factor in this association, suggesting the duration of protection of receiving at least three doses of vaccine is at least 2 years. Furthermore, the interval between the last pre-infection vaccine dose and infection did not significantly affect the likelihood of developing long COVID. These results also have public health significance, namely that the number of doses received was more important than when they were received, provided doses were given prior to infection. Secondly, vaccination after infection did not demonstrate a significant effect in our cohort. This finding aligns with recent reports suggesting that the protective effect of COVID-19 vaccines against the development of long COVID in previously infected individuals is minimal, if present at all35. Furthermore, individuals who were vaccinated after infection may represent a population who already had long COVID symptoms or severe disease before vaccination, and this highlights the importance of vaccination according to schedule at the earliest opportunity. Among never-hospitalized individuals, COVID-19 vaccination was associated with reduced long COVID symptom reporting and modest improvements in QoL, highlighting its role in mitigating long-term sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection beyond acute disease prevention.

While there is literature on the protective effect of COVID-19 vaccines against long COVID, to the best of our knowledge, our study reports new and policy-relevant information on real-world effectiveness, duration of protection, and scheduling of COVID-19 vaccines against long COVID in adults. We found modest effectiveness of the BNT162b2 vaccine, which was consistently statistically significant at each reporting time point among individuals with three or more doses, suggesting enhanced protection against long COVID. This suggests the long duration of protection against severe disease and death conferred by three or more doses of COVID-19 vaccines reported by earlier studies20,36,37,38 extends to long COVID. Vaccination with one or two doses prior to infection did not show a consistent protective effect against long COVID in this study, possibly as a result of waning immunity, viral mutations, or timing of immune priming relative to infection39,40, reinforcing the need for at least one booster dose to confer a robust protective effect against long COVID.

In our study, time elapsed did not modify the protective effect against developing long COVID or a loss in QoL, over the duration of the study (up to 24 months). This is inconsistent with the literature that suggests protection provided by the original vaccination series wanes fast but protection against severe disease can be prolonged through the administration of booster doses35, highlighting the importance of the timing and scheduling of booster doses. Reports indicate that, for prior SAR-CoV-2-infected individuals, additional doses too close to infection with boosters were associated with a muted immune response against SARS-CoV-2, whereas among uninfected individuals, redosing with boosters after 60 days effectively elicited a strong immune response41,42, which further highlights the importance of not only optimizing the timing but also considering the infection status of the target populations for COVID-19 vaccination.

The higher QoL among vaccinated individuals combined with the lower prevalence of long COVID at different time points suggests that QoL is maintained among vaccinated individuals at least partly by preventing long COVID. The dose-dependent improvements in QoL observed in this study are also noteworthy, with at least three doses required to prevent long COVID, and at least three doses being associated with a higher increase in QoL than two doses. Vaccination was associated with a sustained QoL that did not decrease over time and was close to that of individuals who did not report infection at baseline. Our sub-analysis restricted to individuals reporting long COVID suggests that, while COVID-19 vaccines cannot prevent long COVID entirely, pre-infection vaccination may also mitigate the QoL impact of long COVID over at least 18–24 months—in other words, where vaccination does not prevent long COVID, it can at least decrease its negative impact on QoL. These findings are consistent with findings from a healthcare worker cohort in Saudi Arabia showing that COVID-19 vaccination, particularly with booster doses, mitigates the severity of post-COVID symptoms and helps restore QoL among those experiencing lingering effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection43. Consistent findings were reported by a systematic review and meta-analysis involving 13 studies and included 10 million participants in the meta-analysis, where the prevalence of post-COVID symptoms was lower in vaccinated individuals (9.5%) compared to the unvaccinated (14.6%), with a notable decrease in activity-limiting symptoms44. In this study, differences in QoL scores between vaccination groups were small; because there are no established minimally clinically important differences (MCID) in QoL for SARS-CoV-2 or other viral conditions, it is hard to interpret these changes with certainty. However, the increases in QoL we observed were consistent, statistically significant, and dose-dependent. It is worth noting that for some conditions, such as in oncology and chronic pain management, the minimal clinically important differences for EQ-5D index are estimated to be 0.06–0.08 and 0.03–0.05, respectively45,46. The increases seen with vaccination in this study are similar, suggesting they are not below what would be considered a minimum MCID.

The exact mechanisms by which COVID-19 vaccination improves QoL and reduces long COVID risk are not fully understood. However, it has been reported that COVID-19 vaccines are effective in preventing severe COVID-19, which contributes to reduced risk of developing long COVID34. By attenuating the severity of the acute phase of COVID-19, vaccines may reduce the likelihood of long-lasting effects on physical and mental health47. Furthermore, vaccines may impact long COVID risk by limiting immune dysregulation and reducing systemic inflammation, two factors associated with long COVID. Studies on cytokine profiles in long COVID patients revealed elevated levels of pro-inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, indicating ongoing immune activation48. Vaccination has been shown to slow down these inflammatory responses, possibly by decreasing the likelihood of cytokine-driven symptoms49. Another proposed mechanism is that vaccines may promote endothelial stability, as COVID-19 has been associated with endothelial dysfunction and microvascular damage, which could lead to persistent fatigue and brain fog50. By reducing viral-induced endothelial injury, vaccination may protect against such sequelae, contributing to improved QoL and lower long COVID risk51. These mechanisms, while still under investigation, suggest that the benefits of vaccination extend beyond initial infection prevention, offering a layer of protection against chronic, post-acute complications. Thus, vaccination may not only reduce the acute burden of COVID-19 but also help alleviate the long-term health impacts associated with the virus, especially for those at higher risk for long COVID52. Continued research into these immunological and physiological pathways will be essential to fully understand the vaccine’s role in preventing long COVID and enhancing post-infection QoL. It is important to know that, regardless of the mechanism of action, and while vaccination can prevent the onset of long COVID and mitigate its impact on QoL, its effectiveness is modest, and vaccination cannot be considered the ultimate solution against long COVID. The best way to prevent long COVID is to avoid SARS-CoV-2 infection, against which the effectiveness of current vaccines is also limited. Regular boosting increases VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection21, and therefore the risk of long COVID.

The longitudinal design of this cohort study, following individuals for over 2 years post-infection, is a key strength, allowing us to assess the sustained impact of vaccination on QoL and long COVID over a timeframe longer than most studies on the topic. The use of the EQ-5D-5L tool provides a validated and comprehensive measure of health-related QoL, and the application of multiple survey waves enhanced the reliability of our findings. Instead of focusing on individual symptoms, we adopted a cluster of post-COVID symptoms to define long COVID. This approach improves specificity and helps mitigate the risk of misclassification. This approach aligns with the evolving understanding of long COVID and allows for a more precise analysis of the relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and long COVID. Nevertheless, the proportion of our participants reporting long COVID, at the higher end of what meta-analyses suggest, as well as the relatively high proportion of uninfected individuals who report long COVID-compatible symptoms, suggest our case definition may still be oversensitive and highlight the difficulty in classifying long COVID. While we checked for non-informative loss to follow-up and did not find major changes to the socio-demographic characteristics of participants over time (Supplementary Tables 1 and 4), we cannot exclude that participants who were lost to follow-up may have different health outcomes compared to those who completed the study. While we adjusted for potential confounders such as age and sex, confounding due to other variables not included in the study could have occurred. Notably, we did not have information on variants, and could not, in this study, determine whether the effect of vaccination differed according to variant of infection. In addition, it is possible that those who are fully vaccinated also took other preventive measures not measured in this study, such as social distancing or mask wearing, which could have impacted the initial viral load and therefore the severity of the acute infection, itself a predictor of long COVID. Another key limitation of this study is that most individuals today have been infected multiple times and have received multiple COVID-19 vaccinations in between, creating a complex interplay and a number of vaccine–infection combinations we could not address with our sample. Current evidence suggests that long COVID risk may increase with each re-infection53; we could not test whether vaccinations administered between infections effectively mitigate this added risk. We also could not ascertain whether doses beyond three conferred any additional benefit in terms of strength or duration of effect. As COVID-19 transitions to an endemic disease, with periodic re-infections becoming more common, understanding how additional vaccine doses influence long COVID risk will be crucial. Furthermore, since this study relied on self-reported data on symptoms and QoL, the findings may be subject to recall bias. Additionally, individuals lost to follow-up may have had different health outcomes compared to those who completed the study. Finally, almost all our participants have received the monovalent BNT162b2 vaccine, and we do not know whether the findings are generalizable to other vaccines.

Conclusion

This study provides robust evidence supporting the positive effects of COVID-19 vaccination on reducing the risk of long COVID and associated losses in QoL. It confirms existing data on the positive impact of vaccination on long COVID and adds useful and policy-relevant information to the literature regarding the timing and dosage of COVID-19 vaccines to mitigate the effects of long COVID. Our findings underscore the importance of completing the full vaccination course, including booster doses, to mitigate the long-term health impacts of SARS-CoV-2 infection. It also makes it clear that, while vaccination helps mitigate the long COVID burden, its effectiveness is limited, and as such, vaccination cannot be considered by itself to be the ultimate solution against long COVID. As COVID-19 continues to evolve, ensuring widespread access and uptake of booster vaccinations remains a key public health priority to preserve the QoL and prevent long COVID. Future research should explore the mechanisms through which vaccination influences post-COVID outcomes, refining the case definition of long COVID further and introducing more objective measures, the impact of other COVID-19 vaccines, especially among people with underlying conditions, and a focus on exploration of re-infections with evolving virus variants and the long-term robustness of vaccine-induced protection.

Data availability

The data and codes are not publicly available to respect patient privacy, but will be made available upon reasonable request and as guided by the ethics review committee. Interested researchers should contact michael.edelstein@biu.ac.il to inquire about access. Source data for Fig. 2 can be accessed from https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EAM2WB.

References

World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 condition (long COVID). https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition (2022).

Soriano, J. B., Murthy, S., Marshall, J. C., Relan, P. & Diaz, J. V. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, e102–e107 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. Global prevalence of post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) condition or long COVID: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Infect. Dis. 226, 1593–1607 (2022).

Al-Aly, Z., Xie, Y. & Bowe, B. Long COVID: science, research and policy. Nat. Med. 30, 2148–2164 (2024).

Davis, H. E., McCorkell, L., Vogel, J. M. & Topol, E. J. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 133–146 (2023).

Kuodi, P., Gorelik, Y., Gausi, B., Bernstine, T. & Edelstein, M. Characterisation of post-COVID syndromes by symptom cluster and time period up to 12 months post-infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 134, 1–7 (2023).

Iwasaki, A. & Putrino, D. Why we need a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of long COVID. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 393–395 (2023).

Swank, Z. et al. Persistent circulating SARS-CoV-2 spike is associated with post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, e487–e490 (2023).

Proal, A. D. & VanElzakker, M. B. Long COVID or post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): an overview of biological factors that may contribute to persistent symptoms. Front. Microbiol. 12, 698169 (2021).

Zubchenko, S., Kril, I., Nadizhko, O., Matsyura, O. & Chopyak, V. Herpesvirus infections and post-COVID-19 manifestations: a pilot observational study. Rheumatol. Int. 42, 1523–1530 (2022).

Peluso, M. J. et al. Chronic viral coinfections differentially affect the likelihood of developing long COVID. J. Clin. Invest. 133, e163669 (2023).

Wallukat, G. et al. Functional autoantibodies against G-protein coupled receptors in patients with persistent Long-COVID-19 symptoms. J. Transl. Autoimmun. 4, 100100 (2021).

Peluso, M. J. & Deeks, S. G. Mechanisms of long COVID and the path toward therapeutics. Cell 187, 5500–5529 (2024).

Zheng, C. et al. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 114, 252–260 (2022).

Marra, A. R. et al. Short-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in immunocompromised patients: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 84, 297–310 (2022).

Andrews, N. et al. COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 1532–1546 (2022).

Haque, A. & Pant, A. B. Mitigating COVID-19 in the face of emerging virus variants, breakthrough infections and vaccine hesitancy. J. Autoimmun. 127, 102792 (2022).

Huang, Y.-Z. & Kuan, C.-C. Vaccination to reduce severe COVID-19 and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 26, 1770–1776 (2022).

Levin, E. G. et al. Waning immune humoral response to BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine over 6 months. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, e84 (2021).

Bar-On, Y. M. et al. Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against COVID-19 in Israel. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1393–1400 (2021).

Arbel, R. et al. Effectiveness of a bivalent mRNA vaccine booster dose to prevent severe COVID-19 outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 914–921 (2023).

Chalkias, S. et al. A bivalent Omicron-containing booster vaccine against COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1279–1291 (2022).

Byambasuren, O., Stehlik, P., Clark, J., Alcorn, K. & Glasziou, P. Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on long COVID: systematic review. BMJ Med. 2, e000385 (2023).

Watanabe, A., Iwagami, M., Yasuhara, J., Takagi, H. & Kuno, T. Protective effect of COVID-19 vaccination against long COVID syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 41, 1783–1790 (2023).

Kuodi, P. et al. Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and health-related quality of life up to 18 months post-SARS-CoV-2 infection in Israel. Sci. Rep. 13, 15801 (2023).

Sigfrid, L. et al. What is the recovery rate and risk of long-term consequences from COVID-19?—a harmonised, global observational study protocol. BMJ Open 11, e043887 (2021).

Herdman, M. et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 20, 1727–1736 (2011).

Devlin, N. & Parkin, D. in EQ-5D Value Sets: Inventory, Comparative Review and User Guide 39–52 (Springer, 2007).

Hightower, A. W., Orenstein, W. A. & Martin, S. M. Recommendations for the use of Taylor series confidence intervals for estimates of vaccine efficacy. Bull. World Health Organ. 66, 99 (1988).

Jabal, K. A. et al. Impact of age, ethnicity, sex and prior infection status on immunogenicity following a single dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: real-world evidence from healthcare workers, Israel, December 2020 to January 2021. Euro Surveill. 26, 2100096 (2021).

Bates, D., Maechler, M. & Bolker, B. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 0.999999-0 (R Project, 2012).

StataCorp LP. Stata Data Analysis and Statistical Software. Special Edition Release (StataCorp LP, 2007).

Trinh, N. T. H. et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines to prevent long COVID: data from Norway. Lancet Respir. Med. 12, e33–e34 (2024).

Català, M. et al. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines to prevent long COVID symptoms: staggered cohort study of data from the UK, Spain, and Estonia. Lancet Respir. Med. 12, 225–236 (2024).

Šmíd, M. et al. Post-vaccination, post-infection and hybrid immunity against severe cases of COVID-19 and long COVID after infection with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants, Czechia, December 2021 to August 2023. Euro Surveill. 29, 2300690 (2024).

Romero-Ibarguengoitia, M. E. et al. Association of vaccine status, reinfections, and risk factors with Long COVID syndrome. Sci. Rep. 14, 2817 (2024).

Abu Hamdh, B. & Nazzal, Z. A prospective cohort study assessing the relationship between long-COVID symptom incidence in COVID-19 patients and COVID-19 vaccination. Sci. Rep. 13, 4896 (2023).

MacCallum-Bridges, C. et al. The impact of COVID-19 vaccination prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection on prevalence of long COVID among a population-based probability sample of Michiganders, 2020–2022. Ann. Epidemiol. 92, 17–24 (2024).

Goldberg, Y. et al. Protection and waning of natural and hybrid immunity to SARS-CoV-2. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 2201–2212 (2022).

Romeiser, J. L. & Schoeneck, K. COVID-19 booster vaccination status and long COVID in the United States: a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Vaccines 12, 688 (2024).

Buckner, C. M. et al. Interval between prior SARS-CoV-2 infection and booster vaccination impacts magnitude and quality of antibody and B cell responses. Cell 185, 4333–4346 (2022).

Dedroogh, S. et al. Impact of timing and combination of different BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1-S COVID-19 basic and booster vaccinations on humoral immunogenicity and reactogenicity in adults. Sci. Rep. 13, 9036 (2023).

AlBahrani, S. et al. Self-reported long COVID-19 symptoms are rare among vaccinated healthcare workers. J. Infect. Public Health 16, 1276–1280 (2023).

Man, M. A. et al. Impact of pre-infection COVID-19 vaccination on the incidence and severity of post-COVID syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines 12, 189 (2024).

Pickard, A. S., Neary, M. P. & Cella, D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 5, 1–8 (2007).

Coretti, S., Ruggeri, M. & McNamee, P. The minimum clinically important difference for EQ-5D index: a critical review. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 14, 221–233 (2014).

Kim, Y., Bae, S., Chang, H. H. & Kim, S. W. Characteristics of long COVID and the impact of COVID-19 vaccination on long COVID 2 years following COVID-19 infection: prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 14, 854 (2024).

Blomberg, B. et al. Long COVID in a prospective cohort of home-isolated patients. Nat. Med. 27, 1607–1613 (2021).

Speiser, D. E. & Bachmann, M. F. COVID-19: mechanisms of vaccination and immunity. Vaccines 8, 404 (2020).

Charfeddine, S. et al. Long COVID-19 syndrome: is it related to microcirculation and endothelial dysfunction? Insights from the TUN-EndCOV study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 745758 (2021).

Libby, P. & Lüscher, T. COVID-19 is, in the end, an endothelial disease. Eur. Heart J. 41, 3038–3044 (2020).

Jara, A. et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in children and adolescents: a large-scale observational study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 21, 100487 (2023).

Bosworth, M. L. et al. Risk of new-onset long COVID following reinfection with SARS-CoV-2: a community-based cohort study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 10, ofad493 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.E. and P.K. conceptualized the study; P.K. conducted statistical analysis and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. H.S., H.Z., O.W., K.B.W., K.A.J., A.A.D., S.N., D.G., and A.C. reviewed and edited different versions of the draft manuscript; P.K. and O.W. curated the data; M.E. and D.G. provided supervision of the conduct of the study. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Peter Cheung and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuodi, P., Shibli, H., Zayyad, H. et al. Optimizing the schedule of BNT162b2 COVID-19 against long COVID and associated quality of life losses. Commun Med 5, 462 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01160-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01160-7