Abstract

Background

Heart failure (HF) is a major global cause of death. Early risk prediction and intervention could mitigate disease progression. We aimed to improve HF prediction by integrating genome-wide association studies (GWAS)- and electronic health records (EHR)-derived risk scores.

Methods

We previously performed a large HF GWAS within the Global Biobank Meta-analysis Initiative to create a polygenic risk score (PRS). Three Michigan Medicine (MM) cohorts were used to develop the clinical risk score (ClinRS): 1) Primary Care Provider cohort (MM-PCP; N = 61,849), 2) Heart Failure cohort (MM-HF; N = 53,272), and 3) Michigan Genomics Initiative cohort (MM-MGI; N = 60,215). To extract information from high-dimensional EHR data, we leveraged natural language processing to generate 350 latent phenotypes representing EHR codes and used coefficients from LASSO regression on these phenotypes in a training set as weights to calculate ClinRS in a validation set. Using logistic regression, model performances were compared between baseline model and models with risk scores added: 1) PRS, 2) ClinRS, and 3) ClinRS+PRS. We further compared the proposed models with Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) HF risk score.

Results

PRS and ClinRS each predict HF outcomes significantly better than the baseline model, up to eight years prior to HF diagnosis. Including both PRS and ClinRS further improves prediction performance up to ten years prior to diagnosis, two years earlier than either score alone. Additionally, ClinRS significantly outperforms the ARIC model one year prior.

Conclusions

We demonstrate the additive power of integrating GWAS- and EHR-derived risk scores to predict HF cases prior to diagnosis. This standardizable and scalable risk predictor may enable physicians to provide earlier interventions to improve patient outcomes.

Plain language summary

Heart failure (HF) is a leading cause of death worldwide. Early identification of individuals at high risk could facilitate interventions to slow disease progression. In this study, we develop an approach to improve HF risk prediction by combining patient genetic information and clinical information from electronic health records (EHR). We create two risk scores: a polygenic risk score (PRS) based on genetic information, and a clinical risk score (ClinRS) based on patient EHR. We test how well these scores predict HF before diagnosis. Both PRS and ClinRS improve predictions individually and identify high-risk individuals up to eight years in advance. When used together, they provide greater accuracy, predicting HF up to ten years before diagnosis. We suggest that combining genetic and clinical information could help doctors detect HF earlier for better treatment and prevention strategies in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) affects an estimated 64 million patients worldwide, with a growing burden anticipated as the population ages1,2. Echocardiographic screenings in the general population have revealed that up to half of the individuals living with heart failure may be undiagnosed, hampering earlier access to mortality-reducing treatments3,4. Applying risk prediction tools enables earlier identification of diseases, thereby shifting the trajectory of disease progression towards prevention. Additionally, gaining a deeper understanding of the key risk factors for heart failure could shed insight into the mechanisms of disease progression and guide therapeutic management. We sought to evaluate the predictive accuracy of a modern risk assessment tool that incorporates diverse clinical and genetic data compared to genetic or clinical prediction models alone4,5,6.

Clinical prediction tools, such as the Framingham risk score (FRS) and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk score (also known as the pooled cohort equation [PCE]), are commonly used to predict cardiovascular disease (CVD). These have been widely applied for CVD management and updated over time to include a variety of demographic, laboratory, hemodynamic, and medical details7,8,9,10,11. Due to the heterogeneous nature of heart failure, the prediction of incident disease has been less well established. Extant HF risk scores include the Framingham Heart Study score12, Health ABC score13, and the ARIC HF risk score14. However, it is difficult to fully capture the risk based solely on clinical data, which could lead to incomplete assessment as it overlooks genetic information that contributes to disease risk15,16,17. Risk scores incorporating both diverse clinical data and well-powered genetic data are needed for a more precise prediction of heart failure risk.

Genome-wide polygenic risk scores (PRS) estimate an individual’s cumulative genetic risk for a given disease as a weighted sum of genetic effects estimated from GWAS for thousands to millions of genetic variants. Multiple studies have demonstrated that incorporating a PRS into disease risk prediction can enhance prediction accuracy and further improve early prevention6,18. Research in a Chinese population with HF with preserved ejection fraction demonstrated that a 69 variant PRS improved the prediction of 1-year CV death compared to clinical risk scores with or without blood biomarkers such as NT-proBNP19, but failed to assess clinical and genetic factors combined. Multiple efforts have been made to summarize genetic and clinical information for early identification of high-risk patients; however, integrating high-dimensional genome-wide association study (GWAS) and electronic health record (EHR) into heart failure prediction models has yet to be assessed20,21,22.

We explore approaches to enhance the prediction of heart failure events, leveraging both genetic and clinical data. We integrate recent insights on the genetic underpinnings of heart failure with an EHR-based clinical scoring system, referred to as the clinical risk score (ClinRS), to predict heart failure. The PRS was powered by the largest heart failure GWAS23 to date, while the clinical risk assessment borrowed natural language processing (NLP) techniques to capture co-occurrence patterns of medical events within the structured EHR data. From the proposed approaches above, we summarized 907,272 genetic variants into a PRS and 29,346 medical diagnosis codes into a ClinRS. We hypothesized that the additive power of integrating PRS and ClinRS would result in the most powerful heart failure prediction model. In this study, we describe the development of a ClinRS for heart failure, which is created from NLP-extracted medical code embeddings that are clinically meaningful. Together with the PRS, this score predicts heart failure better than the established ARIC-HF score up to 3 years before diagnosis.

Methods

To generate the most statistically powered genetic predictor, we meta-analyzed multiple biobank datasets within the Global Biobank Meta-analysis Initiative (GBMI) consortium to generate a heart failure GWAS23,24. The GBMI consortium aims to enhance GWAS power and improve disease risk prediction through international collaboration among biobanks across the world, and make all GWAS summary statistics open-access for researchers. The case count of the heart failure GWAS from GBMI is the largest to date, and the PRS generated from GBMI meta-analysis GWAS is shown to have higher accuracy in predicting future heart failure events23. The University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board approved research aims and access to the data sets (HUM00128472, HUM00143523, HUM00126227), and participants provided informed consent.

Michigan Medicine EHR system and biobank

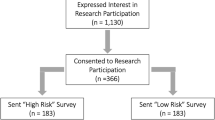

Three cohorts of Michigan Medicine (MM) patients were used in this study: (1) Primary Care Provider cohort (MM-PCP; N = 61,849), (2) Heart Failure cohort (MM-HF; N = 53,272), and (3) Michigan Genomics Initiative cohort (MM-MGI; N = 60,215) (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). All individuals in the three cohorts underwent at least one surgical procedure within the MM healthcare system. The EHR information utilized is International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes, both ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes, from the Epic EHR system implemented at Michigan Medicine. The data were recorded between 2000 and 2022, and the derivation and validation datasets had a median of 10 years of EHR data.

The MM-PCP cohort includes patients (i) with primary care providers within Michigan Medicine, (ii) who had received an anesthetic, (iii) whose most recent visit was in 2018 or later, and iv) who had at least five years of medical encounter history (difference between last and first encounter year ≥5) within Michigan Medicine. Exclusion criteria for this cohort include patients (i) recruited in the Michigan Genomics Initiative and (ii) predefined in the Heart Failure cohort to ensure that no samples overlap with datasets used to validate the clinical predictor. The MM-HF cohort was defined by a previously validated heart failure phenotyping algorithm4. The phenotyping algorithm incorporated ICD diagnosis codes, medication history, cardiac imaging, and clinical notes in the form of free text to assign the disease outcome for each individual. Clinical expert adjudication was performed on 279 individuals to serve as the gold-standard label for algorithm validation.

The Michigan Genomics Initiative (MGI) is an EHR-linked biobank hosted at the University of Michigan with genotype data linked to EHR information to facilitate biomedical research. With both genetic and clinical data available for all individuals in MM-MGI, we were able to validate the prediction models using genetic and/or clinical information. The MM-MGI cohort used in this study is from data freeze 4 (release date: July 2021)25.

The study cohorts were subset to individuals who self-reported as European American in the MM-HF and MM-MGI cohorts, to avoid having reduced performance of genetic predictors in non-white ancestries, thereby biasing the model evaluation towards favoring clinical predictors. The MM-HF and MM-MGI cohorts were comprised of 90% and 86% European American individuals, respectively.

We refer to the MM-PCP cohort as the code embedding derivation set, MM-HF cohort, excluding individuals in the MM-MGI cohort as the ClinRS weights derivation set, and the intersection of the MM-MGI and MM-HF cohort as the model validation set. The model validation set has no overlap with the code embedding and ClinRS weights derivation sets (Supplementary Fig. 1). First, the code embedding derivation set was used to learn EHR code patterns and build medical code embeddings for downstream analysis. Patients with a rich medical history and active records within the system were included for code co-occurrence pattern learning in the code embedding derivation set. Next, the labels curated in the MM-HF cohort served as the outcome in the ClinRS weights derivation set to obtain the weights to calculate ClinRS for heart failure cases prediction. The ClinRS weights derivation set consisted of 7120 individuals from MM-HF and excluded those from the MM-MGI. Last, the model validation set (independent from the ClinRS weights derivation set) was used to assess the prediction ability of PRS and ClinRS. The model validation set included 20,279 participants, who were drawn from the overlapping populations of the MM-MGI and MM-HF cohorts. All patients in the model validation set were assigned a label for heart failure outcome using a phenotyping, fully genotyped to calculate PRS, and had EHR data available to generate ClinRS (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Polygenic risk score (PRS)

The polygenic risk score was derived from the heart failure GWAS conducted by the Global Biobank Meta-analysis Initiative. GBMI is a global collaboration network of 23 biobanks across 4 continents and with over 2.2 million participants (as of April 2022)26. The summary statistics from nine of the GBMI heart failure contributing cohorts (BioMe, BioVU, Estonian Biobank, FinnGen, HUNT, Lifelines, Partners Biobank, UCLA Precision Health BioBank, and UK Biobank) were meta-analyzed, resulting in 974,174 individuals of European ancestry in the combined GWAS. These nine biobanks contributed a total of 51,274 heart failure cases and 922,900 healthy controls, defined by phenome-wide association study code (phecode)27 428.2 (heart failure, not otherwise specified)27,28. IRB and informed consent information for GBMI cohorts is described in Zhou et al. 24. The GBMI heart failure study has the highest heart failure case number in a published GWAS study to date. Advanced genotyping imputation reference panels were used in the participating cohorts, resulting in estimates of variation at additional genetic variants. These advancements in the GBMI heart failure GWAS improved the statistical power to more precisely identify the genetic risk associated with the outcome29,30. In this study, we used the GBMI European-ancestry meta-analysis GWAS to generate a heart failure PRS, which is the current best-performing heart failure PRS for European American individuals (Fig. 1)23.

Polygenic risk score (PRS) was generated (a) using the largest heart failure genome-wide association study (GWAS). b Heart failure GWAS were conducted in nine biobanks with a total of 974,174 individuals and meta-analyzed by the Global Biobank Meta-analysis Initiative. c The meta-analyzed summary statistics were further used to calculate individuals’ PRS and (d) a weighted average of the genotypic risk.

The weights used to create PRS were calculated with PRS-CS31, using European individuals from the 1000 Genome and UK Biobank combined cohort as the LD reference panel32,33. The meta-analyzed heart failure GWAS summary statistics from GBMI used in this study were independent from the validation set used in the analysis to compare the effect contribution between genetic and clinical information for predicting heart failure. PRS were calculated for individuals in the MM-MGI cohort. Possible population substructure was controlled by regressing the raw PRS on the top 10 principal components (PC) derived from the patient’s genotype file. The resulting residuals were inverse normalized to transform the final PRS score into a standard normal distribution.

Clinical risk score (ClinRS)

To extract clinical information from the EHR, we developed machine learning methods to efficiently summarize large-scale, structured, longitudinal EHR data into a clinical risk score, ClinRS, for heart failure. We treated medical diagnosis codes as ‘words’ in human language. Some temporal information is retained as ICD codes from the same day are concatenated into a ‘sentence.’ Using the concept of word embeddings, we capture semantic relationships between words and contextual information about words based on the idea that words with similar meanings tend to occur in similar contexts, also known as the distributional hypothesis34. To do this, we adapted NLP methods to capture the co-occurrence pattern among ICD code sentences in the high-dimensional medical records. The co-occurrence relationship among codes was then utilized to extract independent information and converted into low-dimensional numeric vectors resembling the context and semantics of medical events.

First, we treated 29,346 EHR diagnosis ICD codes as ‘words’ and concatenated all codes documented in a patient’s whole medical history into an ‘article’ using the MM-PCP cohort. After we created the article from all patients, we adapted an NLP technique to obtain numeric vector representations that captured the semantic meaning and context of medical codes (Supplementary Methods)35,36,37. These vector representations were subsequently validated to be clinically meaningful, in the sense that they captured the concept of each code and showed high concordance with expert manually curated phenotypic grouping labels27. We refer to these representations as medical code embeddings hereon.

We leveraged the medical code embeddings to create ClinRS, which is a linear combination of (i) ClinRS weights from the ClinRS weights derivation set (MM-HF, excluding MM-MGI) and (ii) patient latent phenotypes in the model validation set (intersection of MM-MGI and MM-HF, entirely independent from the derivation set). To create ClinRS weights, we first generated patient-level latent phenotypes that combine code embeddings and patients’ code utilization (Supplementary Methods). We then regressed heart failure outcome on latent phenotypes, and the regression coefficients were utilized as weights for the calculation of the ClinRS.

To summarize the multi-dimensional patient-level latent phenotypes into a single risk score, we applied the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) for feature selection with 10-fold validation for shrinkage parameter tuning38. The LASSO leverages the L1 penalty on the regression coefficients to eliminate non-important variables, avoid overfitting, and achieve better prediction. Next, the coefficients yielded from the LASSO model were used as weights (effect sizes) to calculate a weighted sum of patients’ clinical risk. In the ClinRS weights derivation set (individuals in MM-HF excluding MM-MGI), the patients’ latent phenotypes were calculated using EHR records one year prior to heart failure diagnosis (Supplementary Fig. 1). The heart failure outcome was regressed on 350 latent phenotypes and adjusted for age, sex, and healthcare utilization using logistic regression with L1 regularization. Three patient characteristics known to be strong predictors of the outcome (age, sex, and healthcare utilization) were forced into the model with no shrinkage. Patients’ healthcare utilizations were summarized by the number of months of encounters recorded in the EHR. Lastly, the trained ClinRS weights were combined with patient-level latent phenotypes in the validation set to create the final ClinRS (Supplementary Methods). With these steps, we successfully reduced the data dimension from 29,346 unique ICD codes to 350 latent phenotypes, then to a single risk score (Fig. 2).

a Michigan Medicine EHR dataset of 61,894 patients with 29,346 unique codes was used to (b) learn code co-occurrence patterns, and the information was further used to (c) generate patients’ latent phenotypes using medical code embeddings and diagnosis codes in the patients’ EHR. d Next, we regressed heart failure outcome on patients’ latent phenotypes to derive the weights of ClinRS.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analysis was performed using R v4.0.3. First, we validated whether the medical code embeddings generated in the MM-PCP cohort (N = 61,849) were clinically meaningful and suitable for generating a ClinRS, and whether the embeddings could capture the information hidden in the complex EHR dataset. We used the cosine distance between a pair of codes to classify whether a code pair shared the same expert manually curated phenotypic grouping, phecode (i.e., have similar clinical concept) and calculated the concept-AUC. Concept-AUC is the AUC for identifying code pairs in the same phecode group, which was used to aid grid search for optimal NLP-derived medical code embeddings based on existing clinical concept ontology (Supplementary Methods).

We conducted analyses within a cohort of 20,279 individuals in the model validation set (intersection of MM-MGI and MM-HF) with at least one year of medical history prior to a heart failure diagnosis in the Michigan Medicine health system (Supplementary Fig. 1). Ten different datasets with time point cutoffs, one year apart from one year to ten years prior to disease diagnosis, were applied to the analysis. Individuals with no medical history prior to the time point cutoff were removed from the corresponding analysis.

We fit four logistic regression models to predict whether patients have a heart failure diagnosis, and further evaluated the accuracy among models with different risk predictor(s) for all 10 time points, one to ten years prior to disease diagnosis. The baseline model included patients’ demographic information (age at diagnosis and sex), and three additional models with the risk score added: (i) PRS, (ii) ClinRS, and (iii) PRS + ClinRS were created to compare the improvement in model accuracy from the baseline model. In the PRS and PRS + ClinRS models, the top ten PCs derived from patients’ genotype data were adjusted to account for the population structure39.

We further compared model performance with the existing HF risk score from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study14. The components of the ARIC HF risk score include demographic information, vital signs, smoking history, medication history, disease diagnosis, and biomarker (N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP]). Two versions of the ARIC HF risk score were published: (1) a model without NT-proBNP and (2) a model that included NT-proBNP as a predictor. In this study, we were only able to implement the model without incorporating NT-proBNP, as most of the patients do not have this biomarker available in our dataset. Missing information was imputed as zero for the predictors in the ARIC risk score calculation to keep the sample size in the testing set consistent across different risk score models.

Model performances were compared using 10-fold cross-validation area under the receiver operating characteristics (AUC), and the precision-recall AUC calculated using the R package PRROC. We summarized the AUCs of seven models: baseline (age and sex), PRS, ClinRS, ClinRS + PRS model, ARIC HF risk score, ARIC + PRS, and ClinRS + ARIC + PRS, each built from 10 time points. The analysis was performed using European ancestry samples only.

Sensitivity analysis removing circulatory system diagnosis codes

To further verify the validity of ClinRS, additional analyses were conducted to examine the robustness of the co-occurrence patterns captured by the unsupervised NLP algorithm. We created a ClinRS without circulatory system information (ClinRS-NoCirc) by excluding ICD diagnosis codes belonging to ICD-9 Seventh Chapter (390–459) and ICD-10 Chapter IX (I00–I99): Diseases of the Circulatory System. The ClinRS without a circulatory system was further used in model prediction to evaluate the ability of the proposed method. The goal of the sensitivity analysis was to predict disease outcome (heart failure) without directly associated diagnosis information (circulatory system diagnosis codes). We excluded 1340 circulatory system diagnosis codes (459 from ICD-9 and 881 from ICD-10) and used the rest of the 28,006 codes to create patient-level latent phenotypes and applied the newly derived latent phenotypes with ClinRS weights derived previously to generate ClinRS-NoCirc.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

In this study, we utilized three independent datasets (Supplementary Fig. 1) at Michigan Medicine to achieve two main goals: (1) obtain medical code embeddings using NLP techniques in EHR data and (2) improve heart failure prediction using PRS and ClinRS. First, we used the MM-PCP cohort with a total of 61,849 individuals and 159,273,800 diagnosis coding records from 2000 to 2022 to learn the medical code co-occurrence patterns and to extract medical code embeddings representing the clinical meaning of each code. The medical code embeddings trained from MM-PCP were validated using phenotype grouping labels to evaluate whether vector representations derived from an unsupervised NLP method are clustered in similar ways compared to expert, manually curated code grouping (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Next, we built two risk scores, PRS and ClinRS, in the model validation set (intersection of MM-MGI and MM-HF) to predict future heart failure cases. The PRS was calculated using heart failure GWAS summary statistics, meta-analyzed from nine biobanks in GBMI (independent from Michigan Medicine)23. We chose the European ancestry GWAS summary statistics (51,274 cases and 922,900 controls) as the base of our PRS to match the European ancestry of MM cohorts due to its superior performance in the European ancestry individuals in the original publication. From these summary statistics, a total of 907,272 genetic variants were integrated into a polygenic risk score.

The ClinRS calculation required two steps: (i) create patient-level latent phenotypes and (ii) derive weights (effect sizes) to calculate ClinRS. We generated medical code embeddings for 29,346 medical codes from MM-PCP, and then used the medical code embeddings to create 350 latent phenotypes for each patient in MM-HF. To derive weights for the ClinRS, we regressed heart failure outcome on latent phenotypes in the ClinRS weights derivation set (MM-HF, excluding MM-MGI) and extracted the effect sizes as ClinRS weights. The ClinRS weights derivation set had a heart failure incidence of 330 out of 7120 patients (4.6%), whereas in the model validation set, we observed 576 (2.8%) heart failure cases out of 20,279 patients (Supplementary Fig. 1). Our method integrated 29,346 medical diagnosis codes into a single clinical risk score (ClinRS). We further calculated the ARIC heart failure risk score to compare the prediction performance of the proposed model with the existing risk score. Details of the ARIC HF risk score were described in the statistical analysis section.

NLP extracted medical code embeddings are clinically meaningful

A smaller time window size t and inclusion of more features d in a code embedding yielded higher accuracy on identifying code pairs in the same phecode group. We found that diagnosis codes recorded on the same day (t = 1) provided the most information about code relationships. By holding constant embedding dimension d while varying time window size t, the highest concept-AUC was consistently found from co-occurrence matrices constructed based on codes that appeared within 1 day (Supplementary Fig. 2). In general, the higher the embedding dimension d, the higher the concept-AUC was observed. The medical code embeddings generated from a time window t = 1 day with embedding dimension d = 350 yielded the highest concept-AUC of 0.78 in the MM-PCP (Supplementary Fig. 2).

The accuracy attenuated linearly when the window size increased. For example, concept-AUC with embedding dimension d = 350 decreased to 0.76 for codes that co-occurred within 1 week (7 days), and dropped to the lowest of 0.73 for codes that co-occurred within 2 months (60 days). One possible explanation could be that diagnostic codes were often all billed on the same day, e.g., on the last day of hospitalization. Additionally, expanding the time window for code co-occurrence calculation could potentially introduce noise since diagnosis codes recorded on different days may not be related to the same medical event.

We also found that the concept-AUC plateaued with up to embedding dimensions of 300–500, depending on the time-window. This finding is similar to previous reports40,41,42,43,44. This result supports the notion that the medical code embeddings derived through unsupervised learning were clinically meaningful and validated by an expert, manually curated phenotypic grouping. The medical code embeddings corresponding to the above-chosen tuning parameters were further used to calculate patient-level latent phenotype in this analysis.

In addition to numerically evaluating the semantic resemblance of vector representations using concept-AUCs, we further assessed the semantic relationship graphically using a heatmap of the cosine similarity scores (Supplementary Fig. 3). In this study, we used ICD-9 Second Chapter (140–239): Neoplasms as an example to discern how the similarity patterns were formulated among each cancer code. Cancer codes were selected to demonstrate the similarity patterns of code pairs due to their distinct organ system-specific sub-chapter within the cancer codes. For example, codes from cancer of digestive organs (ICD: 150–159) and cancer of respiratory organs (ICD: 160–165) are both cancer codes, but for different organs and were therefore expected to have different patterns and concepts.

As anticipated, we observed that the same ICD-9 diagnosis codes and/or nearby codes (off-diagonal line in Supplementary Fig. 3) had higher cosine values between their embeddings, indicated by the darker color on the off-diagonal line and the band surrounding it. Furthermore, clear distinctions crossing different sub-chapters were found. These results suggest the contextual representations were clinically meaningful since related types of cancers from the same organ system had more similar contexts and patterns of co-occurred comorbidities, treatments, or procedures. Conversely, lower cosine scores were found in code pairs between different sub-chapters of cancer diagnosis ICD-9 codes.

PRS and ClinRS each predict heart failure cases up to eight years in advance

We assessed the accuracy of using genetic and clinical information, individually, in predicting future heart failure. Our evaluation metric was 10-fold cross-validated AUC. We analyzed the performance of each risk score built from ten different time intervals, ranging from one year to ten years prior to the diagnosis of heart failure. To simplify, we refer to these ten intervals as ten time points. Sample size in each time interval decreased from one year to ten years prior to disease diagnosis, ranging from 20,279 (576 cases) to 10,391 (332 cases) participants, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). We thus had sufficient power to fit an accurate model, given that the number of predictors, including demographic information, two risk scores, and PCs derived from genotype data, was less than fifteen.

Our results showed that both PRS and ClinRS models performed significantly better than the baseline model (which only included age and sex) up to eight years prior to heart failure diagnosis (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 2). The results were statistically significant, as determined by non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals (CI). This indicates that each risk score can individually predict heart failure diagnosis better than baseline. The highest AUC was observed in the ClinRS model (0.85 [95% CI: 0.83–0.87]) one year prior to diagnosis, followed by the PRS model (0.76 [0.74–0.83]), which was significantly higher compared to the baseline model with an AUC of 0.70 (0.68–0.72). Overall, ARIC performed similarly to ClinRS; both showed significantly better performance up to 8 years prior to HF diagnosis, compared to the baseline model. Additionally, we observed that at one year prior to HF diagnosis, ClinRS had significantly better performance on predicting HF cases, compared to ARIC. Similarly, one year prior to HF diagnosis ClinRS + PRS (AUC: 0.78 [0.75–0.79]) had significantly better performance than ARIC + PRS (AUC: 0.87 [0.85–0.88]) As expected, the benefits of risk scores derived from clinical information, ClinRS and ARIC, prediction were attenuated by censoring EHR data with increasing time thresholds prior to the event and decreasing sample size. However, better performance in ClinRS and ARIC was still observed until eight years prior to the disease diagnosis. On the other hand, model performances using genetic information were stable across all time points, which yielded significantly higher performance than the baseline model from 1 year to 8 years prior to the disease diagnosis. For example, in a cohort with at least 8 years of medical history within Michigan Medicine, the PRS and ClinRS models yielded an AUC of 0.76 (0.74–0.78) and 0.77 (0.74–0.79), respectively, significantly higher compared to the baseline model with an AUC of 0.71 (0.68–0.73).

Five models were compared at each time point: baseline (age and sex), Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities heart failure risk score (ARIC), polygenic risk score (PRS), clinical risk score (ClinRS), and PRS + ClinRS. Numbers at the bottom of the plot indicate the sample size for each time point. Results showed that ARIC, PRS, and ClinRS, separately, can predict heart failure outcomes 8 years in advance, and adding both risk predictors to the model can predict the disease 10 years in advance. Additionally, ClinRS performed significantly better than ARIC in predicting heart failure events in one year. At 10 years prior to diagnosis, there were 332 cases and 10,059 controls. Case and control counts for all years are in Supplementary Table 2. Error bars represent a 95% confidence interval.

In models given data from nine years prior to disease diagnosis, no significant difference was observed among PRS (AUC: 0.77 [0.74–0.79]), ClinRS (AUC: 0.76 [0.74–0.79]), ARIC (AUC: 0.77 [0.75–0.80]), and baseline (AUC: 0.72 [0.69–0.75]) models. This lack of significant difference between PRS, ClinRS, ARIC, and the baseline model from data 9 years before the diagnosis could potentially be attributed to the smaller sample size. The limited information provided by the EHR data 9 and 10 years prior to the disease diagnosis may have also contributed to the lack of significantly increased prediction, as it may not have provided enough information for complex prediction tasks.

We also calculated the precision-recall AUC, which is better for unbalanced datasets (3–4% cases). We observe similar trends as the 10-fold CV AUC (Fig. 3) although a slightly lower scale overall which is to be expected as the PR-AUC focuses on the model’s ability to identify positive cases which are rare in the validation set (Supplementary Fig. 4). Considering the confusion matrix based on the optimal F1 score, we show that ClinRS significantly improves the precision over the baseline and ARIC models with comparable recall (Supplementary Table 3).

Integrating PRS and ClinRS enhances heart failure prediction

In addition to evaluating the risk score separately, we further studied the additive power of including both risk scores together in the heart failure prediction model. Consistently across all ten time points, the highest accuracy was found in the PRS + ClinRS model (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 2). Significantly higher AUC was continuously found in the PRS + ClinRS model, even at 10 years prior to disease diagnosis with an AUC of 0.79 (0.77–0.82), compared to the baseline model (AUC: 0.72 [0.69–0.75]). Compared to the single risk predictor models that predicted heart failure 8 years prior to disease diagnosis, the model including both predictors predicted disease two years earlier than using either single risk predictor alone.

As expected, we observed that the prediction accuracy of the PRS+ClinRS model outperformed single risk score models throughout the entire 1–10-year time horizons. By using both clinical and genetic risk scores to predict which individuals have a high risk of future heart failure, the combined score identified the highest proportion (28%) of individuals who had heart failure (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Robust results after removing circulatory system diagnosis codes

To examine the robustness of ClinRS and address concerns regarding overfitting, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by removing all circulatory system diagnosis codes to create ClinRS-NoCirc. The model performances of the ClinRS-NoCirc as the clinical risk predictor compared to the ClinRS model were largely consistent (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 4), which demonstrated the success of our efforts to build a risk score that leveraged the high-dimensional EHR records and summarized underlying patterns to reveal disease associations. Notably, the models using ClinRS-NoCirc for predicting future heart failure events yielded significantly higher accuracy than baseline models, up to 6 years in advance of disease diagnosis. We observed an AUC of 0.77 (0.75–0.80) from ClinRS-NoCirc model at 6 years prior to disease diagnosis, which was significantly higher than baseline model at 6 years in advance of heart failure diagnosis (AUC: 0.72 [0.69–0.74], Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 2). Although the results derived from ClinRS-NoCirc could not predict the outcome as many years in advance as the ClinRS model, the additive power of integrating genetic and clinical information in disease risk prediction remains evident through ClinRS-NoCirc. By including both PRS and ClinRS-NoCirc in the heart failure prediction model, we were still able to distinguish patients with a high risk of heart failure a decade in advance of the disease diagnosis. The heart failure prediction model with PRS and ClinRS-NoCirs predictors showed a significantly higher AUC of 0.78 (0.76–0.81) at 10 years prior to heart failure diagnosis, compared to the baseline model with an AUC of 0.72 (0.69–0.75).

We demonstrated that even without circulatory codes, ClinRS captured the co-occurrence patterns through indirect associations. The disease groups most similar to circulatory codes are diseases of the respiratory system, followed by diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (Supplementary Fig. 7). Six of the top 10 codes with the highest average cosine similarity value with circulatory codes are within the respiratory system codes (Supplementary Table 5).

ClinRS insights

We dissected the composition of ClinRS for heart failure prediction to understand the risk and protective factors associated with disease outcome using the ClinRS weights (Supplementary Fig. 8). The diagnoses prioritized in the ClinRS score can generally be classified by (1) organ system (cardiac versus non-cardiac) and (2) etiology (potential causal mechanism, associated comorbidity, or unclear link). As expected, seven out of the top 10 risk factors for heart failure in ClinRS were cardiac diagnoses, exhibiting potential causal mechanisms; for example, ICD-9 codes associated with acute myocardial infarction (Supplementary Table 6). Additional potential causal diagnoses for HF diagnoses, including: (i) stenosis, mitral and aortic valves (ICD: 396.0), (ii) acute myocarditis (ICD: 422.0), and iii) defect, acquired cardiac septal (ICD: 429.71), were highly prioritized by the ClinRS algorithm. Also, ClinRS incorporates many associated-cardiac diagnoses, including (i) malfunction, cardiac pacemaker (ICD: 996.01) and (ii) mechanical complication of automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD: 996.04). These codes are likely to co-occur in patients with heart failure but may have limited utility in predicting new or previously undiagnosed cases; although it is noteworthy that all diagnoses included in ClinRS were documented prior to the heart failure diagnosis. Diagnoses identified by ClinRS, including: (i) Marfan syndrome (ICD: 759.82, 754.82)45, (ii) alcohol abuse (ICD: 303.01, 790.3, 980.0)46, and (iii) viral infection (ICD: 74.8)47, may reflect non-cardiac, causal mechanisms of heart failure pathogenesis. Notably, non-cardiac-related diagnoses, unclear link with a protective effect against heart failure, in the ClinRS score included a cluster of pregnancy-related conditions (ICD: 765.14, 765.25, 656.43, 678, etc.) and another cluster of ophthalmologic diagnoses (ICD: 371.03, 370.03, 370.63, 374.23, 370.35, etc.). No causal or mechanistic relationship should be inferred. This correlation likely results from the lower-risk baseline population (childbearing females) for pregnancy-related conditions and more focused, clinical ophthalmologic assessment being less likely to diagnose heart failure, for the ophthalmologic conditions.

Discussion

This study sought to improve the accuracy of heart failure prediction by integrating high-dimensional genetic data with clinical information to further heart failure prevention initiatives. Genetic risk was summarized by a PRS, calculated from the largest-to-date heart failure GWAS23, and clinical risk was summarized by a ClinRS, an EHR-based risk score. The combined PRS and ClinRS score prediction model identified patients with a high risk of heart failure a decade in advance of the disease diagnosis (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2). Specifically, the PRS + ClinRS prediction model showed a significantly higher AUC at 10 years prior to heart failure diagnosis with an AUC of 0.79 (0.77–0.82) compared to the baseline model with an AUC of 0.72 (0.69–0.74). In contrast, models relying on a single risk score can only identify heart failure cases 8 years in advance. By integrating genetic and clinical information, we identify heart failure cases two years earlier. These findings reveal the power of integrating PRS and ClinRS to enhance disease prediction and the potential to inform heart failure prevention efforts. More broadly, this study highlights the methods and opportunities to curate ClinRS for other complex diseases and integrate with PRS to improve disease prediction accuracy.

Incorporating high-dimensional and longitudinal EHR data presents unique challenges. We successfully developed a risk score summarizing the clinical information despite the complexity of EHR data, and we validated its utility in an independent dataset from an EHR-linked biobank cohort. This study treated structured EHR diagnosis codes as human language and converted the diagnosis codes into articles. This enabled learning the coding patterns for patient records with any dimensionality and longitudinal history. By focusing on co-occurrence patterns of medical codes within a specified time window, we were able to utilize data from all individuals regardless of the length of healthcare utilization. In addition, by applying NLP to transform codes to medical code embeddings, we successfully reduced the high-dimensional EHR dataset into low-dimensional features. The results present an avenue to incorporate other domains of structured EHR datasets, such as medical procedures and laboratory tests, to create a clinical risk score that could more comprehensively capture the risk of having the disease.

The integration of PRS and ClinRS in predictive modeling demonstrated significant improvement over single-source models. We previously developed a heart failure GWAS with the largest number of cases to date to build heart failure risk prediction models23. We successfully reduced high-dimensional GWAS into a single predictor—PRS. Furthermore, we implemented adapted NLP techniques to capture latent phenotypes in EHR data and summarized them into a predictor—ClinRS. Our analysis showed that PRS and ClinRS independently outperformed baseline demographic models, and when combined, the additive prediction model yielded superior accuracy. This result demonstrated the additive predictive power of leveraging genetic and clinical information in risk prediction. The complementarity of PRS and clinical information has been recently shown in a similar approach to generate an EHR-based phenotype risk score (PheRS) in other common diseases48.

In alignment with our findings, Mujwara et al. used a coronary artery disease PRS (CAD-PRS) to reclassify high genetic risk patients from those in the borderline or intermediate of the PCE clinical risk pool21. Their work showed that using the combined PCE and CAD-PRS for risk screening to initiate early preventive treatment could avert 50 ASCVD events over 10 years per 10,000 individuals screened and lead to substantial cost savings per averted event. It is promising that we may achieve more accurate predictions using PRS and ClinRS. Such strategies could then inform guidelines for patient care to aid in the earlier initiation of prevention treatment.

Addressing incomplete EHR data remains a key challenge in clinical risk modeling. Our sensitivity analysis demonstrated that even after removing all circulatory system diagnosis codes, high prediction accuracy was maintained by incorporating ClinRS and PRS. That is, despite partially missing clinical information from the EHR system, we were still able to reach high prediction accuracy one decade prior to disease diagnosis by incorporating ClinRS (without circulatory system diagnosis code) and PRS in the full model (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Table 4). This suggests that pre-trained medical code embeddings can compensate for missing clinical information to allow for robust risk prediction with partial records, which is beneficial for patients with shorter medical histories49. Furthermore, the prediction ability of applying medical code embeddings to fill in the missing information from incomplete EHR records showed that ClinRS could be a more scalable approach compared to traditional risk score calculation. Calculating a traditional risk score with clinical information and biomarkers in a large population requires tremendous resources, and it could lead to underdiagnosis in a population with less access to healthcare. While using pretrained medical code embeddings, we would be able to borrow information from other patients with similar medical condition patterns to predict risk for patients with fewer healthcare visits or missing medical records.

Traditional risk scores, such as the ARIC heart failure risk score, rely on expert-selected risk predictors14. The predictors used in calculating the ARIC HF risk score are labor-intensive, requiring surveys of patients’ health outcomes, measuring biomarkers to identify diabetes patients, and adjudicating coronary heart disease status from electrocardiography by a clinician. In a non-cohort study setting, patients may not have the full set of predictors available in their health records, which could lead to underperformance of the disease prediction. Hence, it is important to develop a method that could perform equally well with or without missing information.

This method is feasible to implement within the EHR, assuming collaboration with EHR vendors. Notably, the ClinRS would be a dynamic score that improves over time—new diagnosis codes can be added, word embeddings can be updated, and the score can be iteratively re-calculated. The longer a patient is in the system and the larger the system, the more precise the risk estimates would become. This data-driven approach may find at-risk individuals who have not had testing for blood biomarkers such as NT-proBNP. However, a Randomized Controlled Trial is necessary to demonstrate clinical utility and improved outcomes if physicians are notified of a patient’s increased risk of heart failure via the EHR.

This study demonstrates how a large-scale EHR-linked biobank can be used to create a standardizable and scalable risk predictor. By applying the NLP method to extract the co-occurrence patterns among patients’ healthcare utilization, we successfully built a risk score, ClinRS, with high performance in predicting HF cases. Moreover, ClinRS used an unsupervised approach to select predictors, and yielded a significantly higher prediction accuracy at one year prior to HF diagnosis compared to ARIC—pre-selected risk predictors by experts.

Despite its strengths, this study has limitations. Heart failure is known to have separate subtypes with distinct treatments and phenotypic symptoms caused by different mechanisms, environmental exposures, or genetic risk factors23. In the future, ClinRS for heart failure subtypes should be developed and validated in cohorts with larger sample sizes. It would also be useful to assess the predictive performance of ClinRS in a prospective study of individuals without cardiovascular-related conditions. Moreover, the curation of ClinRS and the utility of integrating genetic and clinical information for disease risk prediction need to be benchmarked in other complex diseases. This study solely utilized the diagnosis information derived from EHR data; however, leveraging other domains of structured and unstructured EHR data (e.g., procedure, medication, clinical notes, etc.) to assist disease prediction is needed to fully understand the additive power of integrating genetic and clinical data. Furthermore, we did not recalibrate ARIC for the current cohort, and we used the version of ARIC without NT-proBNP since that biomarker was not available. While we used LASSO for dimensionality reduction, future work could test the use of alternative techniques such as auto-encoder50.

Furthermore, an EHR-based study may be limited by low transferability across different healthcare systems due to the heterogeneity of EHR data. Methodology in language models could potentially be borrowed to improve the transferability of medical code embeddings and the derived latent phenotypes. Applying transfer learning techniques could also produce a more generalizable ClinRS to be applied across different healthcare systems. Lastly, due to the limited sample size of people of diverse ancestral backgrounds, we were only able to perform analysis in MGI Biobank individuals with genetic ancestry similar to that of Europeans from a reference population. In the future, models validated in diverse populations are needed.

In conclusion, the amalgamation of GWAS- and EHR-derived risk scores predicted heart failure cases 10 years prior to diagnosis. These findings highlight how the application of natural language processing to complex datasets, such as medical records and the incorporation of genetic information, may enhance the identification of patients with a higher susceptibility to heart failure. Application of this approach at scale may enable physicians to implement preventive measures at a much earlier stage, potentially up to 8 years before a would-be diagnosis, which may prevent the onset of heart failure.

Data availability

The data used in this manuscript were from Michigan Medicine, and it is not publicly available due to legal and privacy limitations. The source data for Fig. 3 are in Supplementary Data 1. The GWAS used for creating the PRS (a meta-analysis without data from Michigan Genomics Initiative) can be accessed upon request to the corresponding author. The all-biobank meta-analysis results are available for downloading at https://www.globalbiobankmeta.org/resources. PRS weights estimated using all-biobank multi-ancestry meta-analysis and leave-UKBB-out multi-ancestry meta-analyses are in the PGS Catalog with study ID PGP000262.

Code availability

Code developed to extract the medical code embedding is publicly available at https://github.com/The-Shi-Lab/CodeEmbedding51.

References

Groenewegen, A., Rutten, F. H., Mosterd, A. & Hoes, A. W. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 22, 1342–1356 (2020).

Savarese, G. & Lund, L. H. Global public health burden of heart failure. Card. Fail. Rev. 3, 7–11 (2017).

van Riet, E. E. S. et al. Epidemiology of heart failure: the prevalence of heart failure and ventricular dysfunction in older adults over time. A systematic review. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 18, 242–252 (2016).

Mathis, M. R. et al. Early detection of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction using perioperative data among Noncardiac surgical patients: a machine-learning approach. Anesth. Analg. 130, 1188–1200 (2020).

Povysil, G. et al. Assessing the role of rare genetic variation in patients with heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 6, 379–386 (2021).

Douville, N. J. et al. Use of a polygenic risk score improves prediction of myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 13, e002817 (2020).

Kannel, W. B., McGee, D. & Gordon, T. A general cardiovascular risk profile: the Framingham Study. Am. J. Cardiol. 38, 46–51 (1976).

Lauer, M. S., Anderson, K. M., Kannel, W. B. & Levy, D. The impact of obesity on left ventricular mass and geometry. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 266, 231–236 (1991).

Wilson, P. W. et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 97, 1837–1847 (1998).

Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Executive summary of the Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 285, 2486–2497 (2001).

Goff, D. C. et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 129, S49–S73 (2014).

Kannel, W. B. et al. Profile for estimating risk of heart failure. Arch. Intern. Med. 159, 1197–1204 (1999).

Butler, J. et al. Incident heart failure prediction in the elderly: the health ABC heart failure score. Circ. Heart Fail. 1, 125–133 (2008).

Agarwal, S. K. et al. Prediction of incident heart failure in general practice: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circ. Heart Fail. 5, 422–429 (2012).

Lambert, S. A., Abraham, G. & Inouye, M. Towards clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Hum. Mol. Genet. 28, R133–R142 (2019).

Santos, R. D. Screening and management of familial hypercholesterolemia. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 34, 526–530 (2019).

Nordestgaard, B. G. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: new insights from epidemiology, genetics, and biology. Circ. Res. 118, 547–563 (2016).

Polygenic Risk Score Task Force of the International Common Disease Alliance Responsible use of polygenic risk scores in the clinic: potential benefits, risks and gaps. Nat. Med. 27, 1876–1884 (2021).

Han, Y. et al. A novel polygenic risk score improves prognostic prediction of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the Chinese Han population. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 30, 1382–1390 (2023).

Surakka, I. et al. Sex-specific survival bias and interaction modeling in coronary artery disease risk prediction. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 16, e003542 (2023).

Mujwara, D. et al. Integrating a polygenic risk score for coronary artery disease as a risk-enhancing factor in the pooled cohort equation: a cost-effectiveness analysis study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e025236 (2022).

Sinha, A. et al. Risk-based approach for the prediction and prevention of heart failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 14, e007761 (2021).

Wu, K.-H. H. et al. Polygenic Risk Score from a Multi-Ancestry GWAS Uncovers Susceptibility of Heart Failure https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.06.21267389 (2021).

Zhou, W. et al. Global Biobank Meta-analysis Initiative: powering genetic discovery across human disease. Cell Genom. 2, 100192 (2022).

Zawistowski, M. et al. The Michigan Genomics Initiative: A Biobank Linking Genotypes and Electronic Clinical Records in Michigan Medicine Patients https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.15.21267864 (2021).

Zhou, W. et al. Global Biobank Meta-Analysis Initiative: Powering Genetic Discovery across Human Diseases https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.19.21266436 (2021)

Denny, J. C. et al. PheWAS: demonstrating the feasibility of a phenome-wide scan to discover gene–disease associations. Bioinformatics 26, 1205–1210 (2010).

Wei, W.-Q. et al. Evaluating phecodes, clinical classification software, and ICD-9-CM codes for phenome-wide association studies in the electronic health record. PLoS ONE 12, e0175508 (2017).

Graham, S. E. et al. The power of genetic diversity in genome-wide association studies of lipids. Nature 600, 675–679 (2021).

Hong, E. P. & Park, J. W. Sample size and statistical power calculation in genetic association studies. Genom. Inf. 10, 117 (2012).

Ge, T., Chen, C.-Y., Ni, Y., Feng, Y.-C. A. & Smoller, J. W. Polygenic prediction via Bayesian regression and continuous shrinkage priors. Nat. Commun. 10, 1776 (2019).

The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018).

Harris, Z. S. Distributional structure. Word 10, 146–162 (1954).

Mikolov, T., Sutskever, I., Chen, K., Corrado, G. S. & Dean, J. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Burges, C. J., Bottou, L. Welling, M., Ghahramani, Z. & Weinberger, K. Q.) Vol. 26 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2013).

Hong, C. et al. Clinical knowledge extraction via sparse embedding regression (KESER) with multi-center large scale electronic health record data. NPJ Digit. Med. 4, 151 (2021).

Levy, O. & Goldberg, Y. Neural word embedding as implicit matrix factorization. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 27 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2014).

Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Methodology) 58, 267–288 (1996).

Choi, S. W., Mak, T. S. H. & O’Reilly, P. F. A guide to performing Polygenic Risk Score analyses. Nat. Protoc. 15, 2759 (2020).

Choi, Y., Chiu, C. Y.-I. & Sontag, D. Learning low-dimensional representations of medical concepts. AMIA Jt. Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2016, 41–50 (2016).

De Vine, L., Zuccon, G., Koopman, B., Sitbon, L. & Bruza, P. Medical semantic similarity with a neural language model. In Proc. of the 23rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management 1819–1822 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2014).

Finlayson, S. G., LePendu, P. & Shah, N. H. Building the graph of medicine from millions of clinical narratives. Sci. Data 1, 140032 (2014).

Levy, O., Goldberg, Y. & Dagan, I. Improving distributional similarity with lessons learned from word embeddings. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 3, 211–225 (2015).

Beam, A. L. et al. Clinical concept embeddings learned from massive sources of multimodal medical data. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 25, 295–306 (2020).

Stuart, A. G. & Williams, A. Marfan’s syndrome and the heart. Arch. Dis. Child. 92, 351–356 (2007).

Djoussé, L. & Gaziano, J. M. Alcohol consumption and heart failure: a systematic review. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 10, 117–120 (2008).

Tam, P. E. Coxsackievirus myocarditis: interplay between virus and host in the pathogenesis of heart disease. Viral Immunol. 19, 133–146 (2006).

Detrois, K.E., Hartonen, T., Teder-Laving, M. et al. Cross-biobank generalizability and accuracy of electronic health record-based predictors compared to polygenic scores. Nat. Genet. 57, 2136–2145 (2025).

Yu, S. et al. Enabling phenotypic big data with PheNorm. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 25, 54–60 (2018).

Liou, C.-Y., Cheng, W.-C., Liou, J.-W. & Liou, D.-R. Autoencoder for words. Neurocomputing 139, 84–96 (2014).

Yidan Zhang, shubo-z & Jiacong Du. The-Shi-Lab/CodeEmbedding: code embedding. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17138965 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all contributors to GBMI and the biobank participants who provided their data for biomedical research. The authors acknowledge the participants, recruitment teams and project managers of the Global Biobank Meta-analysis Initiative for providing data aggregation, management, and distribution services in support of the research reported in this publication (particularly Sinéad Chapman and Bethany Klunder). The authors would like to acknowledge Da-Wei Lin (University of Michigan) for the help with central illustration in Figs. 1 and 2. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants T32-GM070449 (K.H.W.) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, K08-DK131346 (N.J.D.) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, K01-HL141701 (M.R.M.) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, R35-HL135824 (C.J.W.) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and R01-GM139926 (X.S.) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101110878 (B.N.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S. and C.J.W. conceived the study and designed the experiments. K.H.W. and J.D. performed data analysis. N.J.D. and M.R.M. collected clinical data. B.N.W., X.Y., S.E.G., I.S., J.B., L.Z., C.J.W. and X.S. performed data interpretation. I.S., W.E.H., B.N.W. and X.S. contributed to data and project management. K.H.W., J.D. and B.N.W. contributed to manuscript writing and figure preparation. All authors contributed to discussions, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.H.W., S.E.G. and C.J.W. work at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. N.J.D. received funding from the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research (Mentored Research Training Grant). The remaining authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Zichen Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, KH.H., Wolford, B.N., Du, J. et al. Integrating large scale genetic and clinical information to predict cases of heart failure. Commun Med 5, 493 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01198-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01198-7