Abstract

Background

Evidence of the safety of some anti-seizure medicines (ASMs) during pregnancy remains uncertain.

Methods

We conducted a population-based cohort study of singleton pregnancies in Scotland conceived between 01/04/2010-02/07/2023. Exposure was ‘any ASM’ prescription issued 28 days prior to conception up to pregnancy end. Seven monotherapies were also examined: valproate, topiramate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, gabapentin and pregabalin. Unexposed comparators were matched to the exposed on gestational age and year of conception. Pregnancy loss, congenital condition and child development outcomes were compared by exposure status using conditional logistic regression to account for the matched study design.

Results

Here we show pregnancy loss (3175/11,011 pregnancies, 28.8% vs. 24,040/107,889 pregnancies, 22.3%), congenital conditions (230/8370 babies, 2.7% vs. 1693/82,085 babies, 2.1%) and developmental concerns (1270/4890 live births, 26.0% vs. 7658/48,883 live births, 15.7%) are more common following any ASM exposure in pregnancy compared with no ASM exposure in pregnancy. Valproate is strongly associated with pregnancy loss (adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.92, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.50-2.47), congenital conditions (aOR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.06-3.21) and developmental concerns (aOR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.01-2.03). Pregabalin, gabapentin and any ASM are also associated with pregnancy loss and developmental concerns.

Conclusions

Our findings corroborate the associated risks of valproate use and embryo malformations, support the use of lamotrigine and levetiracetam in pregnancy and raise concerns regarding gabapentinoid use in pregnancy.

Plain language summary

This study looked at the safety of taking anti-seizure medications (ASMs) during pregnancy. We studied over 900,000 pregnancies, comparing outcomes in those which did, and did not, receive ASMs. ASMs (especially valproate, pregabalin, and gabapentin) were linked to pregnancy loss and developmental concerns and (valproate) congenital conditions. Lamotrigine and levetiracetam appeared to be safer options. Our findings reinforce the known risks of valproate during pregnancy and raise concerns about pregabalin and gabapentin. Whilst our study demonstrates potential risks associated with taking some anti-seizure medications in pregnancy, there can also be risks associated with suddenly stopping these medicines, for example, worsening of seizure control. It is therefore important that women do not suddenly stop or change their medications without medical advice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anti-seizure medicines (ASMs) are a diverse group of medicines that are used to prevent seizures in patients with epilepsy1,2 and may also be prescribed for other indications, including bipolar disease, migraine and neurological pain disorders3,4,5,6,7,8. Several ASMs are confirmed or suspected to be teratogenic, that is, if taken during pregnancy, they may disrupt the development of the baby, potentially leading to structural congenital and/or developmental conditions.

Evidence of teratogenicity is most conclusive for valproate, which has long been associated with a wide range of adverse pregnancy outcomes, congenital and neurodevelopment conditions, including foetal loss; structural congenital conditions; delay in cognitive, motor and language development; and autism9,10,11. More recently, topiramate has also been associated with foetal growth restriction; structural congenital conditions; and neurodevelopmental disorders, including attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism and learning disabilities9,10,11. Consequently, measures to restrict the use of both valproate and topiramate during pregnancy have been recommended by the European Medicines Agency12,13 and the Food and Drug Administration14,15 and implemented in several countries, including the UK16,17.

Evidence on the safety of some of the other ASMs during pregnancy is less certain. There is substantial evidence that lamotrigine and levetiracetam show a reassuring safety profile with regards to major congenital conditions18,19; however, conclusive data on outcomes such as intrauterine growth restrictions or neurodevelopmental concerns remains relatively scarce, especially for newer ASMs and ASMs that are not as widely used as valproate, topiramate, levetiracetam, or lamotrigine20. Since pregnant women are rarely included in pre-licensing clinical trials, evidence is primarily obtained through post-marketing observational studies. Whilst such studies conducted in diverse settings are accumulating, many have limitations such as small sample sizes, short follow up times, unsuitable control groups and inadequate control for confounding that may affect the robustness and generalisability of findings21,22,23,24,25. Consequently, comprehensive real-world evidence on the safety of some ASMs (particularly the newer ASMs such as lamotrigine and levetiracetam) during pregnancy is still lacking26,27,28.

We aimed to use high-quality, population-based, patient-level data from Scotland to assess associations between maternal exposure to ASMs during pregnancy and pregnancy, baby and early childhood outcomes; specifically, pregnancy loss, structural congenital conditions and early childhood developmental concerns. In doing so, we intend to provide further evidence on the safety and potential risks of ASM use in pregnancy to inform clinical decision-making and guideline development.

We show that valproate taken during pregnancy adversely impacts pregnancy, baby and child outcomes, while newer ASMs, lamotrigine and levetiracetam, are relatively safe. Unexpectedly, we find associations between exposure to gabapentin and pregabalin and early childhood developmental concerns.

Methods

This retrospective population-based, matched cohort study was conducted according to a pre-specified study protocol and statistical analysis plan, which provides full details of data sources and methods29.

Ethical approvals

In line with Public Health Scotland’s (PHS) research governance requirements, we completed a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA; DP23240133) for this study. The DPIA confirmed that PHS’s primary legal basis for conducting this study was Article 6(1)(e) of the UK General Data Protection Regulation (Processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest), with articles 9(2)(i) (public health interest), 9(2)(h) (provision of health services) and 9(2)(j) (research and statistics) also relevant. This confirms that explicit consent is not required from the individuals whose data is used in the study. We used the decision tool provided by the NHS Health Research Authority (https://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/) to confirm that an NHS ethical review was not required30. The PHS Research Office waived the requirement for internal ethical review as our study only involved secondary analysis of existing administrative data (Log #PHS2024-25H015).

Setting and study design

This was a retrospective matched cohort study of singleton pregnancies (and the associated babies and resulting live births) to women in Scotland using linked, national administrative health data.

Data sources

The study was undertaken within PHS, which is Scotland’s national public health agency and part of the National Health Service (NHS). PHS has a statutory responsibility for collating national health datasets and producing official health statistics for Scotland. Local NHS services return summary records to PHS following delivery of elements of care, such as the provision of a prescription or discharge of an individual from hospital. PHS also receives statutory vital event records from the National Records of Scotland. All source records are subject to validation and have the individual’s unique patient identifier appended, allowing linkage across datasets (including intergenerational linkage of records relating to mothers and their biological children).

The specific datasets used for this study were the Scottish Linked Pregnancy and Baby Dataset (SLiPBD) which includes a record of all recognised pregnancies to women in Scotland and (where applicable) the resulting live births31; the Scottish Combined Medicines Database, which includes a record of prescriptions issued in the community and in hospital32,33; the Scottish Linked Congenital Conditions Dataset (SLiCCD) which includes a record of fetuses and infants diagnosed with a major congenital condition as defined by the European network of national congenital condition registers, EUROCAT34, with pregnancy outcome live birth, termination of pregnancy at any gestation, or spontaneous loss at 20 weeks gestation or over35,36; the Child Health Systems Programme: pre-school (CHSP Pre-School) which includes a record of child health reviews offered to all children at agreed ages between birth and school entry37; and Scottish Morbidity Records 01, 02 and 04 which include records of patients discharged from general, maternity and mental health inpatient or day case care, respectively38.

Outcomes

The three outcomes of interest were pregnancy loss; congenital conditions; and early childhood developmental concerns. Pregnancy loss was defined as a pregnancy outcome other than live birth at any gestation, including spontaneous loss (miscarriage, stillbirth) and termination of pregnancy, as recorded in the national pregnancy and baby dataset, SLiPBD. Congenital conditions were any major structural congenital condition in a baby with no known associated/underlying genetic condition, as defined by the European network of national congenital condition registers, EUROCAT and recorded in the national congenital condition linked dataset, SLiCCD. Early childhood developmental concerns were defined as any concern (newly suspected or previously identified) recorded against any developmental domain (speech, language and communication; gross motor; fine motor; problem solving: personal/social; emotional/behavioural) at the 27–30 month assessment offered to all children. In Scotland, child health reviews are conducted by health visitors (specialist nurses) and include a structured discussion with parents to elicit any concerns, observation of the child and completion of a validated developmental assessment questionnaire, such as the Ages and Stages Questionnaire 3rd edition (ASQ-3)39,40. Questionnaires seek to identify delay in meeting expected developmental milestones and do not specifically screen for conditions such as autism or ADHD, which are typically diagnosed later in life41,42.

Cohorts

Three sets of cohorts were drawn from the national pregnancy and baby dataset, SLiPBD, to examine each outcome of interest. Pregnancy cohorts (used to examine the pregnancy loss outcome) included all singleton pregnancies with an estimated date of conception from 1 April 2010 until 2 July 2023. The estimated date of conception as recorded in SLiPBD is derived from information on source records providing the date of antenatal booking or end of pregnancy and the gestation in completed weeks at booking or the end of pregnancy. The gestation information is generally based on a first-trimester ultrasound scan, but in some situations may be based on the last menstrual period (in particular for pregnancies ending in termination) or imputed based on the pregnancy outcome type (in particular for pregnancies ending in miscarriage). Baby cohorts (used to examine the congenital conditions outcome) included fetuses and babies (hereafter ‘babies’ for brevity) from all singleton pregnancies with an estimated date of conception from 1 April 2010 until 2 April 2021. Live birth cohorts (used to examine the early childhood developmental concerns outcome) included live births from singleton pregnancies with an estimated date of conception from 1 April 2010 until 1 July 2020. The differing end dates for the three cohort sets were required to allow sufficient follow-up time to assess each outcome. Cohorts were followed until pregnancy end (pregnancy cohorts) or, for live births, the baby’s first birthday [allowing for pre- or post-natal diagnosis of a congenital condition] (baby cohorts) and age 32 months [the upper age limit for delivery of the 27–30 month review] (live birth cohorts).

Exposures

Exposure ‘in pregnancy’ was defined as a prescription for a specified ASM issued at any point from 28 days prior to the estimated date of conception up to pregnancy end date (pregnancy and live birth cohorts) or 19 weeks and 6 days (19+6 weeks) gestation (or pregnancy end date, if sooner) (baby cohorts). Prescriptions issued were restricted to those subsequently dispensed to minimise exposure misclassification. The typical duration of supply per ASM prescription recorded on the national prescribing dataset is at least 28 days, with an average lag of 4 days between the prescription being issued and it being dispensed. It is therefore highly likely that a woman prescribed an ASM in the 28 days prior to the estimated date of conception would still have a supply remaining at the point of conception. The exposure period ended at 19+6 weeks for baby cohorts as organogenesis is completed by that point, hence later exposures cannot cause structural congenital conditions43. Each cohort set included a cohort of pregnancies to women exposed to any ASM in pregnancy and an additional seven cohorts of pregnancies to women exposed to a single specified ASM in pregnancy (valproate, topiramate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, pregabalin and gabapentin). ‘Any ASM’ included all medicines included in the British National Formulary legacy section 4.8 (anti-epileptic medicines). In addition, valproate-containing products in section 4.2 (drugs used in psychoses and related disorders), identified through Virtual Therapeutic Moiety names, were also included (Supplementary Data 1). Monotherapies were selected based on their potential teratogenicity and/or common use44.

Matching

Exposed pregnancies were matched (with replacement) to ten unexposed equivalents in the general population based on (1) gestation and (2) year of conception45. Unexposed pregnancies (matched to pregnancies in any ASM or seven monotherapy exposed cohorts) were those with no known prescription for any ASM in the corresponding exposure period. Matching on gestation meant that exposed pregnancies were matched to unexposed pregnancies that had attained (at least) the gestational age at which the exposed pregnancy was first prescribed an ASM, thus avoiding immortal time bias. Matching by year of conception accounted for temporal trends.

Covariates

We used directed acyclic graphs to identify covariates for inclusion in adjusted models29. Potential confounders included indications for ASM use (maternal epilepsy; mental health conditions; migraine or chronic pain) and maternal age at conception, deprivation category based on residential postcode at antenatal booking, pre-pregnancy chronic comorbidity and alcohol and drug misuse. Comorbidities were chosen to reflect conditions that may affect women of reproductive age (Supplementary Data 2). Pregnancy complications such as pre-eclampsia were not included as they post-date ASM exposure. Indications for ASM use, chronic comorbidity and alcohol and drug misuse were identified using hospital in-patient and day case discharge records in the five years preceding the estimated date of conception up to 14 days after the pregnancy end date (Supplementary Data 3 and 4). An additional look-back based on prescription records was conducted for indications for ASM use, with date of dispensing from one year prior to conception up to the pregnancy end date (Supplementary Data 5). For models examining early child developmental concerns only, parity was also included as a potential confounder. For models examining early child developmental concerns only, baby sex, maternal BMI at antenatal booking and maternal smoking at antenatal booking were also included as additional covariates.

In supplementary analyses, maternal receipt of high-dose (5 mg per day) folic acid supplements was assessed as a potential effect modifier. Receipt of high-dose folic acid was derived from prescription records (preparations included under BNF legacy sub-section 9.1.2, ATC code B03BB01), with date of dispensing from 84 days prior to 69 days after the estimated date of conception (or pregnancy end date, if sooner). In Scotland, standard dose (400 mcg per day) folic acid supplements are provided directly by maternity services to women (or can be purchased over the counter at pharmacies) with no prescription required. We were therefore unable to tell whether women who did not receive high-dose supplements received a standard dose or no supplements.

Statistics and reproducibility

Primary analyses

For each cohort set and each exposure (any ASM and the seven monotherapies), the characteristics of exposed pregnancies, the total population of unexposed pregnancies and the sample of matched unexposed pregnancies were categorised and summarised using counts and percentages. In pregnancy cohorts, we examined outcomes in 118,900 pregnancies (any ASM exposed = 11,011 pregnancies, matched unexposed = 107,889 pregnancies); in baby cohorts, we examined outcomes in 90,455 babies (any ASM exposed = 8370 babies, matched unexposed = 82,085 babies); and in live birth cohorts, we examined outcomes in 53,773 live births (any ASM exposed = 4890 live births; 48,883 unexposed live births).

For each cohort set and each exposure, we explored the association between exposure and outcome using univariable and multivariable conditional logistic regression models46. Pregnancies were dropped if data for the outcomes were missing. To ensure independence within the matched exposed/unexposed sets that were analysed in conditional logistic regression, if the same unexposed pregnancy was included more than once in the ten matched unexposed equivalents for any one exposed pregnancy, the unexposed equivalent was only retained once in that matched set, with duplicates dropped. Similarly, if sequential pregnancies to the same woman were included within a matched set, only one pregnancy was retained. Where exposure status was discordant between sequential pregnancies within a set, the exposed pregnancy was retained.

Multivariable models were adjusted for potential confounders and covariates, as listed above. Where there were fewer than five outcome events per independent parameter in any model (across exposed and matched unexposed groups combined), categories of potential confounders and covariates were collapsed or the variables removed from the models, with priority given to maternal conditions indicating ASM use, maternal age and, where applicable, baby sex. Unadjusted results were presented where there continued to be too few outcome events47. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals were reported. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Data management and analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.248.

Supplementary analyses

We performed up to four separate supplementary analyses for pregnancy, baby and live birth cohorts, as specified a priori in our protocol29. Firstly we replicated primary analyses using a propensity score approach49. Logistic regression was used to produce weighted propensity scores, which were based on the potential confounders and covariates listed above (excluding baby sex as that cannot influence maternal ASM exposure). The exposed were matched (with replacement) on a 1:1 ratio to the unexposed, based on (1) gestation and (2) propensity score. Calliper width was set at 0.10. The balance of potential confounders and covariates included in propensity scores was assessed using plots50. Potential confounders or covariates were individually added to conditional logistic regression models (in addition to the propensity score) where insufficiently balanced across exposed/unexposed groups. A standardised mean difference of more than 0.05 was chosen as the threshold to also include the individual covariate in the propensity-matched model.

Secondly, we restricted all cohorts (exposed and unexposed) to pregnancies to women with epilepsy.

Thirdly, we included maternal high-dose folic acid in models and an interaction term between maternal high-dose folic acid and ASM exposure, to assess whether receipt of high-dose folic acid (compared to no or standard dose) modified the association between ASM exposure and outcomes. Adjusted stratum-specific estimates for the association between ASM exposure and outcomes in those with and separately, without high-dose folic acid were calculated where significant evidence of interaction was observed (p < 0.10).

Finally, we restricted baby cohorts (examining congenital conditions) to babies from pregnancies that reached at least 12+0 weeks gestation, as congenital condition status is often unknown for pregnancies that end in an early loss.

We conducted an additional off-protocol supplementary analysis in response to reviewer comments. For this analysis, we modelled the OR of termination of pregnancy and, separately, spontaneous loss compared to live birth in pregnancy cohorts using conditional multinomial logistic regression51.

Results

Study population

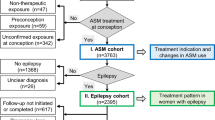

There were 923,440 singleton pregnancies in Scotland with estimated date of conception between 1 April 2010 and 2 July 2023 (‘pregnancy cohorts’ used to assess the pregnancy loss outcome) (Fig. 1). There were 769,366 babies from singleton pregnancies with estimated date of conception between 1 April 2010 and 2 April 2021 (‘baby cohorts’ used to assess the congenital conditions outcome). There were 535,301 live births from singleton pregnancies with estimated date of conception between 1 April 2010 and 1 July 2020 (‘live births cohorts’ used to assess the early childhood developmental concerns outcome). A total of 12,413 (1.3%) pregnancies and 85,545 live births (16.0%) were excluded from pregnancy and live birth cohorts, respectively, as information on outcome was missing.

Exposure

Of 911,027 singleton pregnancies with known outcome in the pregnancy cohort, 11,011 (1.2%) were exposed to any ASM, that is the woman was prescribed at least one ASM at any point during pregnancy (i.e. between 28 days prior to conception and the end of pregnancy) (Fig. 1). Prescribing of any ASM during pregnancy increased over the study period (Fig. 2). For most pregnancies exposed to any ASM during pregnancy (6,910/11,011, 62.8%), the woman’s first exposure during ‘pregnancy’ was in the 28-day period prior to conception (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Among the seven monotherapies examined (where the woman received the stated ASM and no other ASM, during pregnancy), gabapentin accounted for the highest number of exposed pregnancies (2624/911,027, 0.3%), followed by pregabalin (2337/911,027, 0.3%), lamotrigine (1976/911,027, 0.2%), levetiracetam (1086/911,027, 0.1%), carbamazepine (610/911,027, 0.07%), topiramate (391/911,027, 0.04%) and valproate (365/911,027, 0.04%) (Supplementary Data 6). Secular trends in exposure to specific monotherapies during pregnancy varied, for example, exposure to valproate became less common while exposure to pregabalin became more common over time (Fig. 2).

Covariates

Among the 11,011 pregnancies exposed to any ASM in the pregnancy cohort, 9297 (84.4%) had a recorded indication(s) for ASM use, with 6918 (62.8%) having a mental health condition recorded; 5763 (52.3%) migraine or a pain condition; and 2617 (23.8%) epilepsy (Supplementary Data 7). Recorded indication for use varied between pregnancies exposed to different ASM monotherapies (Supplementary Data 6). Mental health conditions were the most commonly recorded indication for women exposed to pregabalin (1984/2337, 84.9%), gabapentin (1984/2624, 75.6%), valproate (191/365, 52.3%), lamotrigine (1034/1976, 52.3%) and carbamazepine (245/610, 40.2%). Migraine or pain conditions were the most commonly recorded indication for women exposed to topiramate (291/391, 74.4%) (and were also commonly recorded for women exposed to pregabalin and gabapentin); and epilepsy was the most commonly recorded indication for women exposed to levetiracetam (561/1086, 51.7%). As would be expected, the relevant conditions were much less commonly recorded in pregnancies unexposed to ASMs. For example, among the 107,889 unexposed pregnancies matched to those exposed to any ASM in the pregnancy cohort, 32,502 (30.1%) had an indication(s) for ASM use recorded and only 373 (0.3%) were reported to have epilepsy (Supplementary Data 7).

Several other confounders and covariates also varied between exposed and unexposed groups. Compared to pregnancies in the matched unexposed sample, pregnancies exposed to any ASM were mostly to women who lived in areas of greater deprivation and to women who were more likely to be obese, smoke, use drugs or alcohol, have a pre-pregnancy comorbidity and have had a previous delivery (Supplementary Data 7).

A similar distribution of confounders and covariates was observed in baby and live birth cohorts. As expected, information on baby sex and maternal BMI, smoking and parity was most complete in the live birth cohort, as this information is generally only recorded for pregnancies ending in a delivery (Supplementary Data 8).

Pregnancy loss

Primary analyses

The prevalence of any loss (spontaneous or termination of pregnancy) among singleton pregnancies in the pregnancy cohort was 28.8% (3175/11,011) among the any ASM-exposed versus 22.3% (24,040/107,889) in the matched unexposed pregnancies (Supplementary Data 9). The prevalence of pregnancy loss among pregnancies exposed to specific ASM monotherapies ranged from 19.9% (216/1086) among those exposed to levetiracetam to 36.3% (849/2337) for pregabalin (Supplementary Data 9). Termination of pregnancy was the most common type of pregnancy loss across all exposed and unexposed groups (Supplementary Data 10).

The crude OR for pregnancy loss among any ASM-exposed pregnancies compared to the matched unexposed pregnancies was 1.44 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.38–1.51) (Fig. 3). After accounting for confounders, the adjusted OR (aOR) was 1.31 (95% CI: 1.24–1.38). By monotherapy, four statistically significant associations between ASM exposure and pregnancy loss were observed after adjustment: for valproate (aOR: 1.92, 95% CI: 1.50–2.47); pregabalin (aOR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.30–1.58); gabapentin (aOR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.21–1.46); and topiramate (aOR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.01–1.63).

1 CI confidence interval. 2 ASM anti-seizure medicine. 3 Adjusted model includes: maternal exposure to ASM, maternal epilepsy, maternal mental health conditions, maternal migraine or pain conditions, maternal age at conception, maternal Scottish index of multiple deprivation (SIMD), maternal drug or alcohol use and maternal comorbidities.

Singleton pregnancies conceived in Scotland between 1 April 2010 and 2 July 2023 (pregnancy cohort). Odds ratios from conditional logistic regression. The total sample sizes for each ASM exposure group (n in exposed cohort and n in matched unexposed groups) are shown in the right-hand columns. The number with pregnancy loss outcomes in the exposed and unexposed groups can be found in Supplementary Data 9.

Supplementary analyses

Findings generated from the propensity score approach were similar to primary analyses (Supplementary Data 11 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

In analyses restricted to pregnancies to women reported to have epilepsy, only valproate continued to be associated with higher odds of pregnancy loss (aOR: 2.14, 95% CI: 1.41–3.25) (Supplementary Data 12 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Exposure to any ASM, carbamazepine, lamotrigine and levetiracetam was associated with decreased odds of pregnancy loss.

In analyses incorporating high-dose folic acid, supplementation was observed to modify the association between any ASM, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, levetiracetam and gabapentin exposure and pregnancy loss (Supplementary Data 13). Receipt of high-dose folic acid attenuated the odds of pregnancy loss, except among the gabapentin exposed (Supplementary Data 14 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

In additional analyses examining termination of pregnancy and spontaneous loss (compared to live birth) separately, results were similar to the primary analyses. However, they were less certain (in particular for spontaneous loss) due to the smaller numbers involved when modelling these outcomes separately (compared to together as a single composite outcome) (Supplementary Data 15 and Supplementary Fig. 5). In adjusted analyses, exposure to Any ASM, gabapentin and pregabalin remained significantly associated with an increased odds of both termination of pregnancy and spontaneous loss. Exposure to valproate and topiramate remained significantly associated with termination of pregnancy, but not spontaneous loss.

Congenital conditions

Primary analyses

The prevalence of major structural (non-genetic) congenital conditions among babies from singleton pregnancies exposed to any ASM in the baby cohort was 2.7% (230/8370) versus 2.1% (1693/82,085) in the matched unexposed babies (Supplementary Data 9). The prevalence of congenital conditions among babies from pregnancies exposed to specific ASM monotherapies ranged from 2.1% (44/2103) among those exposed to gabapentin to 4.8% (17/354) for valproate (Supplementary Data 9). Congenital heart disease was the most common congenital condition type across exposed and unexposed groups (Supplementary Data 16).

The crude OR for congenital conditions among any ASM-exposed babies compared to the matched unexposed babies was 1.34 (95% CI: 1.17–1.54) (Fig. 4); the adjusted OR was 1.11 (95% CI: 0.93–1.32). Only exposure to valproate monotherapy was found to be significantly associated with congenital conditions after adjustment (aOR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.06–3.21).

1 CI confidence interval. 2 ASM anti-seizure medicine. 3 Adjusted model includes: maternal exposure to ASM, maternal epilepsy, maternal mental health conditions, maternal migraine or pain conditions, maternal age at conception, maternal Scottish index of multiple deprivation (SIMD), maternal drug or alcohol use and maternal comorbidities. 4 Adjusted model includes: maternal exposure to ASM, maternal epilepsy, maternal mental health conditions, maternal migraine or pain conditions, maternal age at conception (collapsed), maternal Scottish index of multiple deprivation (SIMD), maternal drug or alcohol use and maternal comorbidities.

Babies from singleton pregnancies conceived in Scotland between 1 April 2010 and 2 April 2021 (baby cohort). Odds ratios from conditional logistic regression. The total sample sizes for each ASM exposure group (n in exposed cohort and n in matched unexposed groups) are shown in the right-hand columns. The number with congenital condition outcomes in the exposed and unexposed groups can be found in Supplementary Data 9.

Supplementary analyses

No statistically significant associations were observed using the propensity score approach (Supplementary Data 11 and Supplementary Fig. 6).

In analyses restricted to babies of women reported to have epilepsy, exposure to any ASM (aOR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.17–1.98) was associated with congenital conditions (Supplementary Data 12 and Supplementary Fig. 7). Results for monotherapies were uncertain and in some cases adjusted odds ratios could not be calculated, due to the relatively small number of women with epilepsy exposed to specific ASMs.

Analyses restricted to babies from singleton pregnancies reaching at least 12+0 weeks gestation gave very similar results to our primary analyses, with only valproate associated with congenital conditions (aOR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.07–3.22) (Supplementary Data 17 and Supplementary Fig. 8).

Exposure to high-dose folic acid did not modify the association between any ASM or ASM monotherapy and congenital conditions (Supplementary Data 13).

Early childhood developmental concerns

Primary analyses

The prevalence of early childhood developmental concerns (identified at the 27–30 month assessment) among live-born babies from singleton pregnancies exposed to any ASM in the live birth cohort was 26.0% (1270/4890) versus 15.7% (7658/48,883) in the matched unexposed live births (Supplementary Data 9). Concerns, by monotherapy, ranged from 21.5% (37/172) among those exposed to topiramate to 28.8% (57/198) for valproate (Supplementary Data 9). Speech, language and communication were the most common developmental domain with a reported concern across all exposed and unexposed groups (Supplementary Data 18).

The crude OR for early childhood developmental concerns among any ASM-exposed live births compared to the matched unexposed live births was 1.90 (95% CI: 1.78–2.04) (Fig. 5). The adjusted OR was 1.31 (95% CI: 1.20–1.43). By monotherapy, three statistically significant associations between ASM exposure and developmental concerns were observed after adjustment: for valproate (aOR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.01–2.03); pregabalin (aOR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.10–1.58); and gabapentin (aOR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.02–1.39).

1 CI confidence interval. 2 ASM anti-seizure medicine. 3 Adjusted model includes: maternal exposure to ASM, maternal epilepsy, maternal mental health conditions, maternal migraine or pain conditions, maternal age at conception, maternal Scottish index of multiple deprivation (SIMD), maternal drug or alcohol use, maternal comorbidities, baby’s sex, maternal smoking, maternal BMI and parity.

Live births from singleton pregnancies conceived in Scotland between 1 April 2010 and 1 July 2020 (live birth cohort). Odds ratios from conditional logistic regression. The total sample sizes for each ASM exposure group (n in exposed cohort and n in matched unexposed groups) are shown in the right-hand columns. The number with early childhood developmental concerns in the exposed and unexposed groups can be found in Supplementary Data 9.

Supplementary analyses

Findings were similar when using a propensity score approach (Supplementary Data 11 and Supplementary Fig. 9).

In analyses restricted to live births to women reported to have epilepsy, exposure to any ASM remained associated with early childhood developmental concerns (aOR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.09–1.44). Results for ASM monotherapies were uncertain however, pregabalin exposure also remained associated with developmental concerns (aOR: 3.08, 95% CI: 1.50–6.33) (Supplementary Data 12 and Supplementary Fig. 10).

High-dose folic acid was observed to modify the association between any ASM and carbamazepine exposure and early childhood development concerns (Supplementary Data 13). Receipt of high-dose folic acid attenuated the odds of developmental concerns (Supplementary Data 14 and Supplementary Fig. 11).

Discussion

This population-based study used high quality data collected in routine care across Scotland to assess associations between exposure to ASMs during pregnancy and three important clinical outcomes: pregnancy loss (spontaneous and due to termination of pregnancy); structural, non-genetic, congenital conditions identified in fetuses/babies; and concerns about early child development identified in live born babies (recorded at the 27–30 month assessment offered to all children). Our results confirm statistically significant associations between exposure to valproate during pregnancy and all adverse outcomes examined. Our findings contribute to the accumulating evidence that exposure to lamotrigine and levetiracetam during pregnancy is not associated with adverse pregnancy or child outcomes. Unexpectedly, we found no evidence of an association between topiramate exposure and congenital conditions or early childhood developmental concerns. We did, however, find evidence of an association between exposure to gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin) and both pregnancy loss and early childhood developmental concerns.

In primary analyses (including all pregnancies exposed to an ASM), we found an association between any ASM and several ASM monotherapies and any pregnancy loss. As previously stated in our per-protocol analyses we examined any pregnancy loss as our outcome of interest. We chose this approach as spontaneous loss (in particular, early miscarriage) and termination of pregnancy act as competing risks, making the results of modelling specific types of pregnancy loss in isolation difficult to interpret. This approach does mean that any associations found between ASM exposure and pregnancy loss may reflect associations with spontaneous loss (reflecting biological risk) and/or women’s decisions to continue or terminate a pregnancy (mainly reflecting reproductive choices). However in the additional supplementary analyses undertaken in response to reviewer comments, we generally observed that associations between ASM exposure and any pregnancy loss seen in our primary analyses reflected an association with both spontaneous loss and termination of pregnancy.

Existing evidence on ASM exposure and pregnancy loss is inconsistent, reflecting methodological differences between studies. A UK study found no evidence linking ASM exposure and spontaneous loss52; however, a study from India did suggest a possible association with spontaneous loss53. A multi-centre prospective cohort study found an association between pregabalin exposure and all pregnancy loss, however, this has not been consistently confirmed in other studies54.

In our per-protocol supplementary analyses restricted to pregnancies to women with epilepsy, we did not find evidence of an association between ASM exposure and pregnancy loss, apart from for valproate. In fact, the chance of pregnancy loss was significantly reduced in pregnancies to women with epilepsy who were exposed to any ASM, carbamazepine, lamotrigine and levetiracetam when compared to matched unexposed pregnancies to women with (untreated) epilepsy. In addition, we found that receipt of high dose (5 mg per day) folic acid around the time of conception (compared to receipt of none or standard [400 mcg per day] dose) generally attenuated the association between ASM exposure and pregnancy loss. These supplementary results may reflect a low rate of termination of pregnancy among planned (compared to all) pregnancies, as it is likely that women with epilepsy who are on ASM treatment (compared to all women receiving an ASM for any indication) are more likely to receive preconception counselling and hence plan their pregnancies. Receipt of high-dose folic acid also suggests pregnancy planning and engagement with healthcare.

In primary analyses, we only found an association between exposure to valproate during pregnancy and the detection of a major structural congenital condition in the baby. This finding aligns with well-established evidence on the teratogenicity of valproate9,18,55,56. Existing evidence also suggests an association between topiramate and congenital conditions19,55,56,57,58, hence not finding this association in our study was unexpected. Our lack of an association may reflect inadequate statistical power to detect a relatively modest association due to small numbers of pregnancies exposed to topiramate and the relative rarity of the congenital condition outcome. It may also reflect a dose effect. Migraine was the most commonly recorded condition indicating topiramate use in our study population, with epilepsy uncommonly recorded. This differs to previous studies, which mostly studied women with epilepsy55,56,57. The dose of topiramate used for migraine (usually 50–100 mg per day, maximum 200 mg) is lower than that used for epilepsy (usually 100–200 mg per day, maximum 500 mg) and there is evidence that the teratogenicity of topiramate is dose dependent57.

In primary analyses, we found an association between exposure to any ASM, valproate, gabapentin and pregabalin during pregnancy and concerns about children’s development identified at reviews offered by specialist nurses to all children at 27–30 months of age as part of Scotland’s child health programme. Existing evidence on ASM exposure during pregnancy and resulting developmental outcomes in exposed children tends to reflect neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism, ADHD and intellectual disability diagnosed later in childhood41,42, rather than early ‘concerns’ (reflecting potentially transient delay in reaching expected milestones and/or parent or nurse concerns) examined in our study. Our findings align with existing evidence supporting an association between valproate exposure and neurodevelopmental conditions42,59 and no association between lamotrigine and these outcomes11. Existing evidence relating to topiramate or carbamazepine and neurodevelopmental conditions is mixed, with some studies demonstrating a relationship between exposure and intellectual disability and autism59 and others showing inconsistent or no evidence of association11,42.

The most unexpected findings in our study are those showing an association between exposure to gabapentin or pregabalin during pregnancy and concerns about the resulting children’s development. Studies reporting on associations between gabapentin and/or pregabalin and developmental outcomes are still comparatively rare and the available evidence is, thus far, inconclusive. A study using data from 2005 to 2016 from Nordic countries did not find any association between pregabalin exposure and autism spectrum disorders or intellectual disability at age 4–7 years41; likewise, a French study did not observe an association between exposure to either gabapentin or pregabalin and neurodevelopmental disorders or visits to speech therapists60. In contrast, a recent systematic review—collating studies from 14 different countries— identified an increased risk of specific neurodevelopmental outcomes, including ADHD, after pregabalin exposure during pregnancy61. Differences between study findings may reflect methodological differences, including exposure and outcome definitions, follow-up time and adjustments for confounding, including maternal characteristics (such as smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity) and indication for prescribing (epilepsy vs pain conditions).

Developmental concerns identified at the 27–30-month child health review are strongly associated with maternal health and sociodemographic factors40. These factors were particularly common among the women exposed to gabapentinoids during pregnancy that were included in our study (compared to pregnancies/women exposed to other ASM monotherapies). For example, women exposed to gabapentinoids had higher rates of mental health or pain conditions (rather than epilepsy), indicating ASM use and higher rates of smoking, drug and alcohol misuse and other pre-pregnancy comorbidities. As would therefore be expected, in our primary analyses, adjustment for confounding and covariates noticeably attenuated the crude association between gabapentinoid exposure and developmental concerns. Nevertheless, associations remained after adjustment in primary analyses and these were also found in planned supplementary analyses using propensity scores (rather than individual covariates) to adjust for potential confounding. The results of further supplementary analyses restricted to pregnancies to women with epilepsy were uncertain due to small numbers of women with epilepsy exposed to these medicines; however, an association between pregabalin exposure during pregnancy and early childhood developmental concerns was also found in this group. We cannot exclude residual confounding as a potential explanation for the observed association between gabapentinoids and developmental concerns. Nevertheless, gabapentinoids are known to cross the placental and blood-brain barrier and may inhibit the release of neurotransmitters62,63. In addition, it has been demonstrated in murine models that gabapentin may interfere with neurogenesis during foetal brain development64. The observed associations with child development may therefore be biologically plausible. As exposure to these medicines is increasing in Scotland and many other countries65, with evidence that in some settings they are starting to be prescribed off-label for common conditions such as chronic back pain, depression and fibromyalgia66,67,68 in addition to their licenced conditions, including epilepsy and neuropathic pain, further research on the safety of gabapentinoids in pregnancy is urgently needed.

We found no evidence that receipt of high-dose folic acid around the time of conception (compared to no or standard dose) modified the association between ASM exposure and congenital conditions and evidence that it attenuated the association with developmental concerns for any ASM and carbamazepine only. These results may reflect inadequate power to detect interactions and/or relatively little benefit of high, compared to standard, dose supplementation. Folate deficiency during pregnancy is associated with a range of structural congenital conditions69 and ASMs can reduce folate levels70. Folic acid supplementation just before and in early pregnancy is therefore recommended for women taking ASMs although there is an ongoing debate about the incremental benefit of high compared to standard dose18,71. There is little direct evidence on the protective effect of different doses of folic acid supplementation, but our findings broadly align with the results of a Norwegian study that found a reduced chance of autistic traits in children exposed to ASMs during pregnancy, where the mother also received (mainly high dose) folic acid72. Given this ongoing uncertainty, further research on the benefits and safety of different doses of folic acid supplements for women taking ASMs is needed.

Our study has several strengths. We used high-quality, population-based administrative health data to include all recognised pregnancies to women in Scotland over a 13-year period and ascertain exposure to a wide range of antiseizure medicines and pregnancy, baby and child outcomes. The administrative health datasets used have nationwide coverage and as services—including antenatal care and prescriptions—are free at the point of care for all residents, data completeness is high. Similarly, as records are generated through direct clinical care and data is subject to validation and regular quality checks, data quality is high73. Furthermore, in line with our pre-published protocol, we applied a range of analytical methods to account for potential confounding and conducted numerous supplementary analyses.

Inevitably, some limitations remain. In particular, whilst stringent efforts have been made to control for confounding, we cannot exclude the possibility that some residual confounding remains. For example, we did not identify an indication for ASM use among 16% of pregnancies exposed to an ASM, despite using hospital discharges and prescribing data to ascertain relevant conditions. Our hospital data did not include outpatient appointments, so we may have missed milder indications or comorbidities. In addition, we used a pragmatic exposure definition, which did not incorporate ASM duration or dose. Some exposure misclassification may have occurred (for example, a pregnancy being classified as exposed to an ASM when it was not) for reasons including inaccuracy in the estimated date of conception or a woman delaying or not taking her prescribed medication. To mitigate this as far as possible, we aligned our exposure periods with international standards where available and only ‘counted’ prescriptions that were subsequently dispensed. Any remaining exposure misclassification (in particular that relating to women not taking their dispensed medication) would be expected to bias findings towards the null, suggesting that the associations we observed were, if anything, underestimated. However, we assessed multiple exposures and outcomes, increasing the likelihood of chance findings.

In our per-protocol analyses, we examined associations between ASM exposure and any pregnancy loss, with termination of pregnancy and spontaneous loss modelled together as a composite outcome due to competing risk between these types of pregnancy loss and the loss of precision seen when modelling smaller numbers of different types of loss separately. We modelled these outcomes separately in additional supplementary analyses to attempt to disentangle the effects of ASM exposure on spontaneous loss as opposed to reproductive choices, but the results from multinomial modelling should be interpreted with caution due to the persistent issue of competing risk. Finally, since Scotland is a relatively small country, some of the exposure groups within the cohorts are comparatively small and sample sizes may have not been sufficient to detect rare outcomes.

Conclusions

This study contributes robust population-based real-world evidence on the safety of ASMs in pregnancy. Valproate adversely impacts pregnancy, baby and child outcomes—corroborating longstanding evidence of teratogenicity—while newer ASMs, lamotrigine and levetiracetam, are relatively safe. Unexpectedly, we find associations between exposure to gabapentin and pregabalin and early childhood developmental concerns. Given the increasing use of gabapentinoids among pregnant women in Scotland and other countries, further research on the safety of these medicines in pregnancy is urgently needed.

Data availability

Patient-level data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to data protection and confidentiality requirements. Public Health Scotland is the data holder for the data used in this study. Public Health Scotland currently intends to retain all the datasets used in this study indefinitely as a public good in line with the organisational data retention policy. Data can be made available to approved researchers for analysis after securing relevant permissions from the data holders via the Public Benefit and Privacy Panel for Health and Social Care. Enquiries regarding data availability should be directed to Research Data Scotland at: https://www.researchdata.scot/accessing-data/. Timelines involved in securing access to data vary according to the complexity of the request. An overview of the process is provided at: https://www.researchdata.scot/accessing-data/data-access-overview/. All source numbers for Fig. 1 are presented within the figure. The source data for Fig. 2 can be requested by emailing phs.cardriss@phs.scot. For Figs. 3–5, the sample size, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are provided within each figure, with additional data on the number of outcome events available in Supplementary Data 9.

Code availability

Metadata and code are available on GitHub at: https://github.com/Public-Health-Scotland/ASM-pregnancy-population-study-public74.

References

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Epilepsy (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, accessed 31 March 2025); https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summaries/epilepsy/.

Kanner, A. M. & Bicchi, M. M. Antiseizure medications for adults with epilepsy: a review. JAMA 327, 1269–1281 (2022).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: assessment and management (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, accessed 31 March 2025); https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185 (2023).

Sadegh, A. A., Gehr, N. L. & Finnerup, N. B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled head-to-head trials of recommended drugs for neuropathic pain. PAIN Rep. 9, e1138 (2024).

Baftiu, A. et al. Changes in utilisation of antiepileptic drugs in epilepsy and non-epilepsy disorders—a pharmacoepidemiological study and clinical implications. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 72, 1245–1254 (2016).

Ali, S. et al. Indications and prescribing patterns of antiseizure medications in children in New Zealand. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 65, 1247–1255 (2023).

Knezevic, C. E. & Marzinke, M. A. Clinical use and monitoring of antiepileptic drugs. J. Appl. Lab Med. 3, 115–127 (2018).

Macfarlane, A. & Greenhalgh, T. Sodium valproate in pregnancy: what are the risks and should we use a shared decision-making approach? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 200 (2018).

Veroniki, A. A. et al. Comparative safety of anti-epileptic drugs during pregnancy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of congenital malformations and prenatal outcomes. BMC Med. 15, 95 (2017).

Veroniki, A. A. et al. Comparative safety of antiepileptic drugs for neurological development in children exposed during pregnancy and breast feeding: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open 7, e017248 (2017).

Hernández-Díaz, S. et al. Risk of autism after prenatal topiramate, valproate, or lamotrigine exposure. New Eng. J. Med. 390, 1069–1079 (2024).

European Medicines Agency. Valproate and related substances–referral (European Medicines Agency, accessed 31 March 2025); https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/valproate-related-substances-0 (2018).

European Medicines Agency. Topiramate-referral (European Medicines Agency, accessed 31 March 2025); https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/topiramate (2023).

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Risk of oral clefts in children born to mothers taking Topamax (topiramate) (U.S. Food & Drug Administration, accessed 7 April 2025); FDADrugSafetyCommunication:Riskoforalcleftsinchildrenborn740tomotherstakingTopamax(topiramate)|FDA (2011).

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Valproate Anti-seizure Products Contraindicated for Migraine Prevention in Pregnant Women due to Decreased IQ Scores in Exposed Children (U.S. Food & Drug Administration, accessed 7 April 2025); https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-valproate-anti-seizure-products-contraindicated-migraine-prevention (2013).

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Topiramate (Topamax): introduction of new safety measures, including a Pregnancy Prevention Programme (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, accessed 31 March 2025); https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/topiramate-topamax-introduction-of-new-safety-measures-including-a-pregnancy-prevention-programme (2024).

Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency. New valproate safety measures apply from 31 January (Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency, accessed 31 March 2025); https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-valproate-safety-measures-apply-from-31-january (2024).

Hope, O. A. & Harris, K. M. Management of epilepsy during pregnancy and lactation. BMJ 382, e074630 (2023).

Hernandez-Diaz, S. et al. Use of antiseizure medications early in pregnancy and the risk of major malformations in the newborn. Neurology 105, e213786 (2025).

Tomson, T., Sha, L. & Chen, L. Management of epilepsy in pregnancy: what we still need to learn. Epilepsy Behav. Rep. 24, 100624 (2023).

Giannakou, K. Perinatal epidemiology: issues, challenges, and potential solutions. Obstet. Med. 14, 77–82 (2021).

Margulis, A. V., Kawai, A. T., Anthony, M. S. & Rivero-Ferrer, E. Perinatal pharmacoepidemiology: how often are key methodological elements reported in publications? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 31, 61–71 (2022).

Grzeskowiak, L. E., Gilbert, A. L. & Morrison, J. L. Investigating outcomes associated with medication use during pregnancy: a review of methodological challenges and observational study designs. Reprod. Toxicol. 33, 280–289 (2012).

Lupattelli, A., Wood, M. E. & Nordeng, H. Analyzing missing data in perinatal pharmacoepidemiology research: methodological considerations to limit the risk of bias. Clin. Ther. 41, 2477–2487 (2019).

Wood, M. E., Lapane, K. L., van Gelder, M. M. H. J., Rai, D. & Nordeng, H. M. E. Making fair comparisons in pregnancy medication safety studies: an overview of advanced methods for confounding control. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 27, 140–147 (2018).

Kaplan, Y. Lamotrigine and pregnancy: the discrepancies regarding the oral clefts and dose-dependent risk of malformations. BMJ 353, i1965 (2016).

Peron, A. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after prenatal exposure to lamotrigine monotherapy in women with epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 24, 103 (2024).

Alsfouk, B. A. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children exposed prenatally to levetiracetam. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 13, 20420986221088419 (2022).

Public Health Scotland. Medicines in pregnancy: Scotland-wide cohort study protocol (Public Health Scotland, accessed 31 March 2025); https://publichealthscotland.scot/publications/medicines-in-pregnancy-scotland-wide-cohort-study-protocol (2025).

NHS Health Research Authority. Do I need NHS REC review? (NHS Health Research Authority, accessed 31 March 2025); https://hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/.

Lindsay, L. et al. Data resource profile: Scottish linked pregnancy and baby dataset (SLiPBD). Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 9, 2390 (2024).

Alvarez-Madrazo, S., McTaggart, S., Nangle, C., Nicholson, E. & Bennie, M. Data resource profile: the Scottish National prescribing information system (PIS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 714–715f (2016).

Mueller, T. et al. Data resource profile: the hospital electronic prescribing and medicines administration (HEPMA) national data collection in Scotland. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 8, 2182 (2023).

European Commission. European platform on rare disease registration (EU RD Platform) (European Commission, accessed 31 March 2025); https://eu-rd-platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/_en.

EUROCAT. EUROCAT Guide 1.5 Chapter 3.3 (EUROCAT, accessed 8 August 2025).

Public Health Scotland. Congenital conditions in Scotland-2000 to 2021 (Public Health Scotland, accessed 4 September 2025); CongenitalconditionsinScotland-2000to2021-CongenitalconditionsinScotland-Publications-PublicHealthScotland (2023).

Public Health Scotland. Pre-school system-Child health programme (Public Health Scotland, accessed 4 September 2025); Pre-school system-Child health programme-Child health data and intelligence-Early years and young people- Population health-Public Health Scotland https://Pre-schoolsystem-Childhealthprogramme-Childhealthdataandintelligence-Earlyyearsandyoungpeople-Populationhealth-PublicHealthScotland (2025).

Public Health Scotland. SMR Data Manual-National Data Catalogue (Public Health Scotland, accessed 4 September 2025); SMRDataManual-NationalDataCatalogue-Healthintelligenceanddatamanagement-Resourcesandtools-PublicHealthScotland (2025).

Scottish Government. The Scottish Child Health Programme: Guidance on the 27-30 month child health review (Scottish Government, accessed 31 March 2025); https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-child-health-programme-guidance-27-30-month-child-health-review/pages/9/ (2012).

Public Health Scotland. Early child development statistics-Scotland 2022 to 2023 (Public Health Scotland, accessed 8 August 2025); Earlychilddevelopmentstatistics-Scotland2022to2023-Earlychilddevelopment-Publications-PublicHealthScotland (2024).

Dudukina, E. et al. Prenatal exposure to pregabalin, birth outcomes and neurodevelopment—a population-based cohort study in four Nordic countries. Drug Saf. 46, 661–675 (2023).

Bjørk, M. et al. Association of prenatal exposure to antiseizure medication with risk of autism and intellectual disability. JAMA Neurology 79, 672 (2022).

DeSilva, M. et al. Congenital anomalies: case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine 34, 6015–6026 (2016).

Public Health Scotland. Anti-Seizure Medicines in Pregnancy (Public Health Scotland, accessed 7 April 2025); https://publichealthscotland.scot/publications/anti-seizure-medicines-in-pregnancy/anti-seizure-medicines-in-pregnancy-1-april-2025/ (2025).

Ho, D., Imai, K., King, G. & Stuart, E. A. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J. Stat. Softw. 42, 1–28 (2011).

Therneau, T. A Package for survival analysis in R (Therneau, T., accessed 28 April 2025); https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival.

Vittinghoff, E. & McCulloch, C. E. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am. J. Epidemiol. 165, 710–718 (2007).

R Core Team. The R Project for Statistical Computing (R Core Team, accessed 31 March 2025); https://www.R-project.org/.

Austin, P. C. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav. Res. 46, 399–424 (2011).

Greifer, N. cobalt: Covariate Balance Tables and Plots (Greifer, N., accessed 28 April 2025); https://ngreifer.github.io/cobalt/.

Elff, M. mclogit: Multinomial Logit models, with or without random effects or overdispersion (Elff, M., accessed 8 August 2025); CRAN: Package mclogit https://CRAN:Packagemclogit.

Forbes, H. et al. First-trimester use of antiseizure medications and the risk of miscarriage: a population-based cohort study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 95, 693–703 (2024).

Trivedi, M., Jose, M., Philip, R. M., Sarma, P. S. & Thomas, S. V. Spontaneous fetal loss in women with epilepsy: prospective data from pregnancy registry in India. Epilepsy Res. 146, 50–53 (2018).

Winterfeld, U. et al. Pregnancy outcome following maternal exposure to pregabalin may call for concern. Neurology 86, 2251–2257 (2016).

Bromley, R. et al. Monotherapy treatment of epilepsy in pregnancy: congenital malformation outcomes in the child. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8, CD010224 (2023).

Battino, D. et al. Risk of major congenital malformations and exposure to antiseizure medication monotherapy. JAMA Neurology 81, 481–489 (2024).

Cohen, J. et al. Comparative safety of antiseizure medication monotherapy for major malformations. Ann. Neurol. 93, 551–562 (2022).

Lin, K., He, M. & Ding, Z. Postmarketing safety surveillance of topiramate: a signal detection and analysis study based on the FDA adverse event reporting system database. J. Evid. Based Med. 17, 795–807 (2024).

Madley-Dowd, P. et al. Antiseizure medication use during pregnancy and children’s neurodevelopmental outcomes. Nat. Commun. 15, 9640 (2024).

Blotière, P. et al. Risk of early neurodevelopmental outcomes associated with prenatal exposure to the antiepileptic drugs most commonly used during pregnancy: a French nationwide population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 10, e034829 (2020).

Beau, A., Mo, J., Moisset, X., Bénévent, J. & Damase-Michel, C. Systematic review of gabapentinoid use during pregnancy and its impact on pregnancy and childhood outcomes: a ConcePTION study. Therapies 80, 378–416 (2024).

Furugen, A. et al. Involvement of l-type amino acid transporter 1 in the transport of gabapentin into human placental choriocarcinoma cells. Reprod. Toxicol. 67, 48–55 (2017).

Chincholkar, M. Gabapentinoids: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and considerations for clinical practice. Br. J. Pain 14, 104–114 (2020).

Alsanie, W. F. et al. Prenatal exposure to gabapentin alters the development of ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 923113 (2022).

Cohen, J. et al. Prevalence trends and individual patterns of antiepileptic drug use in pregnancy 2006-2016: a study in the five Nordic countries, United States, and Australia. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 29, 913–922 (2020).

Benassayag Kaduri, N., Dressler, R., Abu Ahmad, W. & Rotshild, V. Trends in pregabalin use and prescribing patterns in the adult population: a 10-year pharmacoepidemiologic study. CNS Drugs 38, 153–162 (2024).

Schaffer, A. L., Busingye, D., Chidwick, K., Brett, J. & Blogg, S. Pregabalin prescribing patterns in Australian general practice, 2012–2018: a cross-sectional study. BJGP Open 5, (2021).

Torrance, N. et al. Trends in gabapentinoid prescribing, co-prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines, and associated deaths in Scotland. Br. J. Anaesth. 125, 159–167 (2020).

Greenberg, J. A., Bell, S. J., Guan, Y. & Yu, Y. Folic acid supplementation and pregnancy: more than just neural tube defect prevention. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 4, 52–59 (2011).

Linnebank, M. et al. Antiepileptic drugs interact with folate and vitamin B12 serum levels. Ann. Neurol. 69, 352–359 (2011).

Bjørk, M. et al. Pregnancy, folic acid, and antiseizure medication. Clin. Epileptol. 36, 203–211 (2023).

Bjørk, M. et al. Association of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy with the risk of autistic traits in children exposed to antiepileptic drugs in utero. JAMA Neurol. 75, 160–168 (2018).

Public Health Scotland. National Data Catalogue (Public Health Scotland, accessed 31 March 2025) https://publichealthscotland.scot/resources-and-tools/health-intelligence-and-data-management/national-data-catalogue/.

Moore, E., Miller, M. & Stark, V. Pregnancy, baby and childhood outcomes from using anti-seizure medication during pregnancy, https://github.com/Public-Health-Scotland/ASM-pregnancy-population-study-public: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17550908 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all individuals and organisations that contributed to this study. In particular, we acknowledge the contributions of our colleagues at Public Health Scotland, Chris Robertson, Clara Calvert, Laurie Berrie, Bob Taylor and Carole Day, whose support in team meetings and/or feedback greatly improved this work. We sincerely thank members of the Scottish Government Teratogenic Medicines Advisory Group for their critical review and offer of insights and suggestions. We also thank Katherine Donegan, formerly of the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency, for suggesting supplementary analyses. Financial support for this study was provided by the Scottish Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B., R.W. and S.M. conceived the study. R.W., M.B., T.M., A.K. and S.M. designed the study. R.W., T.M. and E.M. drafted the protocol, which was updated by R.M. E.M., M.M. and V.S. prepared the data. E.M. and M.M. performed the statistical analyses. T.M. and R.M. wrote the first draft and all authors contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript. R.W. and M.B. gave final approval for the version to be published. R.W. acts as guarantor for the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moore, E., Millar, M., Merrick, R. et al. Pregnancy, baby, and childhood outcomes from using anti-seizure medication during pregnancy. Commun Med 6, 28 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01285-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01285-9