Abstract

Background

Clear communication is essential for the effective uptake of public health interventions promoting protective behaviours for respiratory infection control. The emergence of novel infectious diseases, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic, has highlighted the need for rapid adaptation of established and new behavioural practices. However, there remains limited knowledge concerning effective strategies for disseminating risk-reduction information and predicting population responses.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis (PROSPERO: CRD42020198874) assessed the effectiveness of these interventions using behavioural science frameworks, including MINDSPACE contextual influencers and behaviour change techniques (BCTs), to identify key components and mechanisms of action (MoAs). Twenty-four full-text articles, comprising 36 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) across 11 countries, were included via electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Scopus) and other sources (grey literature, Google Scholar, and reference lists) searched to March 2022.

Results

Here, we show that interventions mainly target social distancing, mask wearing, hand washing, and various behavioural intentions and actual behaviours, using a median of three-arm study designs with passive comparators. Interventions include a median of two contextual influencers and four BCTs. Behaviour intention is the most frequently applied mechanism of action. Study quality is moderate. Narrative synthesis of 16 full-texts (26 RCTs) shows significant effects, while network meta-analysis of 16 full-texts (21 RCTs) indicates that prosocial messages, particularly those referencing loved ones, are effective in reducing the risk of respiratory infections (d = 0.09; 95% CrI=0.06–0.14; CINeMA: Low).

Conclusions

Although further research is needed, the review provides insight into designing public health messages that effectively improve protective behaviours for respiratory infection control.

Plain language summary

This study examined whether public health messages can encourage people to adopt protective behaviours, such as wearing masks, washing hands, and keeping distance, to reduce the spread of respiratory infections like COVID-19 and influenza. We reviewed and combined the results of 36 studies from 11 countries. To understand what works best, we used behavioural science tools that show how messages influence people’s decisions and actions. We found that messages appealing to social values, especially those about protecting loved ones, were more effective in encouraging safer behaviours. These findings highlight the importance of designing health messages that connect with people’s emotions and motivations. Clear and well-targeted communication can help the public respond more effectively in future outbreaks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic made plain that in the face of a novel viral infection causing severe respiratory disease, among other containment measures, the rapid adoption of population protective and physical social distancing behaviours was required1,2. As the waves of infection unfolded and vaccinations became available, it remained the case that behavioural interventions focused on personal protective behaviours (such as hand and respiratory hygiene, mask wearing, and social distancing) were still important to contain transmission3,4,5. Respiratory infection is, of course, not just the consequence of COVID, and into the future, containment strategies against influenza in particular will continue to be important.

Clear communication is essential for the development of public health advice messages that promote effective behavioural respiratory infection control. Understanding what influences the uptake of non-pharmaceutical interventions may help to inform the development of future effective public health advice messages1,6. For instance, simply advising people to adopt these behaviours has been found to be ineffective7. Consequently, in the context of both pandemics and seasonal epidemics, it becomes imperative to employ effective strategies for conveying vital health messages in a succinct and meaningful manner. These strategies should facilitate the adoption of protective behaviours by citizens while mitigating community ambivalence and panic8,9.

A promising key principle, which is based on social identity10, social influence11 and moral behaviour12, promotes care for others rather than individual self-interest13. These ‘protect each other’ messages highlight the benefits of protective behaviours for the wider social group and its most vulnerable members, including loved ones, with evidence of benefits in the COVID-1914 and other health contexts15. Prosocial behaviour is defined as behaviour that benefits others, whether or not it involves an overall cost to self, and includes a variety of important social behaviours such as helping, sharing, and cooperation16,17. The term “others” refers to specific individuals or groups of people, and in particular loved ones, vulnerable members (with weakened immune systems such as the elderly and chronically ill), health care professionals, co-workers, keyworkers, members of the public, and to some extent society as a whole18.

Studies have shown that people do consider the social impact of their behaviour during a pandemic, as many participants avoid putting others at risk for their personal benefit19. The existing literature illustrates that prosocial public health messages that highlight behaviours related to societal and communal benefits (e.g., “protect each other”), rather than focusing on behaviours that only benefit the self (e.g., “protect yourself”), can be a potential mechanism to communicate public health recommendations related to infectious diseases20,21,22,23.

Although the studies mentioned earlier provide some evidence for the effectiveness of prosocial messages in promoting adherence to personal protective behaviours, we still lack robust evidence about the magnitude of this effect24. As individuals are exposed to conflicting information and misinformation, this can decrease individuals’ perceptions of the severity of the disease and the necessity of adopting preventive behaviours, which in turn may lead to rejection of public health messaging. Therefore, there is a need to examine the extent to which prosocial messages to adhere to personal protective behaviours are effective across different contexts, for better future pandemic and epidemic preparedness. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to identify whether the prosocial messages have the potential to optimise the effect on population behaviour in relation to reducing transmission of respiratory infections. More specifically, we ask the following questions: (1) Are messages focusing on protecting others effective in changing a defined list of behavioural (intention) outcomes compared with other messages/controls?, (2) What actual behaviours or behaviour intentions (e.g., social distancing, hand washing, using hygiene products etc.) do messages about protecting others have positive effects on? (3) What populations do messages about protecting others have positive effects on?

A total of 36 randomized controlled trials conducted in 11 countries met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review (21 were included in the meta-analysis). The network meta-analysis shows that prosocial messages have a small but statistically significant effect on personal protective behavioural intentions (d = 0.09, 95% CrI 0.06–0.14). Self-focused messages show weaker and less consistent effects. Component network meta-analyses indicate that interventions incorporating information about health consequences (d = 0.12, 95% CrI 0.03–0.28) and avoidance or reduction of exposure to cues (d = 0.19, 95% CrI 0.06–0.32) are associated with small but statistically significant increases in protective behavioural intentions. Considering these results, prosocial and carefully designed communication strategies should be prioritized in future public health campaigns to strengthen behavioural intentions for respiratory infection control.

Methods

This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020198874)25. A detailed protocol of the review has been published18. We used established PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines statement for Network Meta-Analyses26 and also followed quantitative meta-analysis reporting standards by the APA27 and procedures outlined by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews28. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not required for this systematic review, as the study utilized exclusively previously published literature and did not involve the collection of primary data.

Search strategy and selection criteria

A search strategy (Supplementary Table S1) following PICOS was adapted (population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design), including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and relevant keywords and combining search terms using Boolean operators29,30. To identify controlled vocabulary terms for the databases, we first retrieved articles from each database that met the inclusion criteria for the review. We noted common text words and subject terms applied by the indexers and used them for a comprehensive search. To ensure we captured as many relevant records as possible, including older ones, we combined subject terms from the controlled vocabulary with a wide range of free-text terms31.

Original studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (a) were RCTs, non-randomised studies with concurrent controls, or controlled before-and-after studies; (b) measured potential changes in any behaviour relevant to reducing the transmission of respiratory infections (e.g., hand hygiene, social distancing, face masks); (c) included messages with prosocial content about protecting others17; (d) used communication via mass media, social media, or print media (such as leaflets and posters), or health professional advice via consultation; (e) included general population from any geographical region, with or without vulnerabilities, regardless of infection status; (f) included relevant comparisons involving no message, or an active control with messages focused on self-protection, or messages containing no motivational content and (g) were published in English (Supplementary Table S2). Studies such as animal experiments, abstracts, case reports, reviews, and systematic reviews were excluded.

A comprehensive literature search of published and unpublished studies in electronic databases was conducted. The following electronic databases were searched from inception to January 2021 and updated in March 2022: Medline, EMBASE.com, PsycINFO, and Scopus. For unpublished studies, we conducted searches in databases of “grey” literature such as PsycEXTRA, Social Science Research Network (SSRN), OSF PREPRINTS database that includes BioHackrXiv, Cogprints, MediArXiv, SocArXiv, PsyArXiv and RePEc. We also conducted supplementary searches in Google Scholar, hand searched relevant journals, and backward and forward citation searching of included studies and relevant reviews. For each grey literature source, we developed tailored search strategies, adapted from those used in electronic databases, using combinations of controlled vocabulary (where available) and free-text terms aligned with our PICOS framework, combined with Boolean operators. For Google Scholar, which uses proprietary ranking algorithms and can retrieve extremely large numbers of results even with highly specific search criteria, we limited screening to the first 10 pages (100 results) sorted by relevance. We applied the same approach to OSF Preprints (including BioHackrXiv, Cogprints, MediArXiv, SocArXiv, PsyArXiv, and RePEc), which also return very large numbers of records similar to Google Scholar. This decision was guided by both methodological precedent and practical considerations. Empirical studies indicate that the most relevant and highest-quality results are concentrated within the first 100–200 hits, with subsequent pages yielding progressively less relevant material and a higher proportion of false positives32,33. Screening beyond this point is unlikely to substantially improve comprehensiveness but would considerably increase workload and introduce irrelevant results. Our approach is consistent with established guidance for systematic reviews using search engines, where restricting screening to top-ranked results is recognised as a practical and defensible strategy. For backward citation searching, we manually reviewed the reference lists of all studies sought for retrieval as well as of relevant systematic reviews to identify additional potentially eligible records. For forward citation searching, we used Google Scholar to identify more recent studies that had cited these articles.

All titles and abstracts retrieved from both published and unpublished studies through electronic searching were imported into the reference manager EndNote and subsequently uploaded to Covidence, a systematic review management tool recommended by Cochrane, to facilitate duplicate removal, screening, and study selection34. Duplicates were removed and double-screening was done on a proportion of the retrieved citations until the appropriate agreement (>95%) was achieved (450 studies; kappa = 0.969; 95% Cl 0.909–1.000). The remaining studies were screened by one reviewer (AG). The abstracts were included if they met the inclusion criteria. The same procedure was applied to determine the eligibility of studies on the basis of a review of the full texts. Differences in judgement were resolved through discussion and inclusion of a third researcher doing the rating, when required. The selection process was recorded and the PRISMA flow diagram was completed35.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from the included studies into a predefined spreadsheet, which covered the following areas: the study design; the communication message; characteristics of the recipient(s) of the communication (protect-others-message); characteristics of the “others” who will be protected due to the message; the manner in which the appeal to protect others is made; intervention features such as the primary outcome(s) and the results.

As primary outcomes, we considered any actual behaviour or behavioural intention relevant to reducing transmission of respiratory infections. Intentions are assumed to capture the motivational factors that influence behaviour. The stronger the intention to perform the behaviour, the more likely the behaviour will be performed36,37. Where more than one reported primary outcome is provided, we included all, reporting their measurements, metrics, methods of aggregations and time-points (when applicable).

Study characteristics were extracted by one reviewer (AG) and checked for accuracy by a second reviewer (VA). Outcome data were extracted independently by two reviewers (AG and VA). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (IV).

Quality assessment

Two researchers (AG and VA) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2)38. The percentage of studies with high, low, or some concerns against each criterion was established by consensus between the two assessors. No studies were excluded because of risk of bias.

Data analysis and synthesis

We carried out a systematic review to qualitatively extract the key MINDSPACE conceptual influencers and behaviour change techniques used in prosocial messaging interventions to adhere to personal protective behaviours and quantitatively assess their effectiveness in reducing transmission of respiratory infections.

A narrative synthesis was conducted for each of the personal protective behavioural intentions and actual behaviours. Reviewers’ own descriptions of results were grouped into “positive” effects (e.g., a significant difference between intervention and control groups, favouring the intervention group, was detected), “no difference” (e.g., a significant difference between groups was not detected), “negative” effects (e.g., a significant difference between groups, favouring the control group, was detected). A narratively synthesised section with the attributes of the target population (characteristics of the individuals, groups, sub-populations or populations) that are affected by messages about protecting others was also included.

We content analysed these messages to identify what drives the change in behaviour. Two of the most popular and widely used behavioural tools were chosen due to their relevance and applicability to health policy, the MINDSPACE checklist39,40,41 (stands for: Messenger, Incentives, Norms, Defaults, Salience, Priming, Affect, Commitments, and Ego; Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Note 1), and the Behaviour Change Techniques Taxonomy (BCTT; Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 2)42,43,44,45,46. The MINDSPACE checklist, developed by Dolan et al.39, operates on the premise that many behaviours are primarily driven by automatic, often unconscious psychological processes and can be influenced by the decision-making context41. The BCTT includes 93 techniques aimed at fostering behaviour change by targeting specific psychological processes, including beliefs, attitudes, goals, plans, emotions, habits, and more. There has not been an academic investigation of the degree of conceptual (or theoretical) overlap between MINDSPACE and the BCTT (see Vlaev and Dolan47 for initial analysis of how those nudges and techniques work through specific, and distinct, neuropsychological processes). Therefore, the possibility for unique insights to exist in each behavioural tool motivated us using both tools in our analysis. To address the challenges of inconsistent or ambiguous terminology in behaviour change intervention outcome measures, we utilized the “Mechanisms of Action” (MoA) Ontology48,49. This tool acts as a classification system that labels and defines MoAs and their interrelationships. MoAs describe the processes by which interventions influence target behaviours, such as beliefs, intentions, and behavioural opportunities (Supplementary Method; Supplementary Data 1).

We also calculated the effective ratio (ER) to assess the effect of each MINDSPACE contextual influencer and BCT for the USA and European countries. This measure indicates their potential contribution to the effectiveness of the intervention50. The intervention outcomes were classified as effective (indicating statistical significance in intervention(s) and control comparisons) and ineffective (outcome was not statistically significant). The ER is calculated as the number of effective results involving the MINDSPACE contextual influencer or BCT (i.e., interventions that were statistically significantly more effective than the control) divided by the number of ineffective results involving that same influencer or technique. The ER could not be calculated if only one study was available.

A network meta-analysis was conducted as most appropriate for comparing three or more interventions simultaneously in a single analysis by combining both direct and indirect evidence across a network of studies, calculating the standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% credible intervals (CrIs: the Bayesian alternative to 95% confidence intervals) using WinBUGS, a statistical software for Bayesian analysis. All analyses included 30,000 iterations as burn-in; once convergence was confirmed, these iterations were discarded and the model was run for a further 70,000 iterations.

It produces estimates of the relative effects between any pair of interventions in the network, and usually yields more precise estimates than a single direct or indirect estimate51. The simultaneous comparison of all interventions of interest in the same analysis enables the estimation of their relative ranking for a given outcome52. In particular, a class-effects model53 was conducted, including all the outcomes reported in RCTs (which met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis: adequate result information, consistency in outcome elements (e.g., consistent methods of aggregation, consistent specific measurements and metrics)) whilst accounting for dependencies where more than one outcome per RCT is included. In addition, random effects NMAs were calculated using WinBUGS for each outcome separately. A key NMA assumption is the consistency between direct and indirect evidence. Global tests for inconsistency were conducted for each outcome using a design x treatment interaction test54. When a global test identified potential inconsistency, tests for loop inconsistency were conducted for each evidence loop. Network geometry was explored and illustrated using network diagrams. Component network meta-analyses (CNMAs) were conducted to assess the effectiveness of intervention components55,56 categorised according to the BCTT and Mindspace components. Class effects were also used to account for multiple outcomes reported in RCTs.

For each outcome, including personal protective behavioural intentions and subgroup outcomes like social distancing intentions, hand washing intentions, mask wearing intentions, and diverse-behavioural intentions, we evaluated the confidence in the body of evidence derived from NMA using the Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis (CINeMA) application57,58, which is broadly based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. The GRADE methodology considers four levels of evidence: high quality, moderate quality, low quality, and very low quality. High quality indicates that the true effect closely aligns with the NMA estimates, while moderate quality suggests a likelihood that the actual effect is similar to the NMA estimates but could differ substantially. Low quality implies a possibility that the true effect differs significantly from the NMA estimates, and very low quality indicates a high likelihood of substantial differences. We determined the certainty of the evidence using the online CINeMA software (https://cinema.ispm.ch), which assesses criteria such as within-study bias, reporting bias, indirectness, imprecision, heterogeneity, and incoherence. If any concerns, whether minor or major, are identified, the certainty of the evidence is downgraded. Although CINeMA is a valuable tool for assessing the certainty of evidence in NMAs, its direct applicability to CNMAs may be limited due to differences in analytical approach and scope of assessment. Thus, the CINeMA has not been used for our CNMAs.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

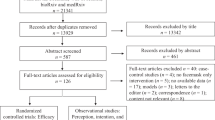

The search strategy yielded 6108 studies. After screening the titles and abstracts, 49 studies were selected for full-text screening. A total of 24 full-texts met the inclusion criteria (20 were published16,24,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76, while 4 were pre-prints)14,77,78,79. Eight of them included more than one randomised controlled trial study (RCT), yielding 36 RCTs in total. No studies with other designs (such as quasi-experimental studies) fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The majority of RCTs (32/36) targeted COVID-19, while 4 RCTs targeted multiple respiratory infections, including (but not limited to) influenza. The characteristics of included RCTs are described in more detail in Supplementary Data 2 and 3. Sixteen (21 RCTs)Study1,14,24,62,63,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,74,76,78,79 of the 24 full-texts (36 RCTs) provided sufficient information to be included in the final quantitative analysis (Fig. 1).

Effectiveness of prosocial messages

Twenty-six RCTs from high-income countries (USA, Denmark, UK, Japan, Germany, Turkey) reported positive effects regarding the included messages focusing on “protect-others” principle16,24,60Study1,61,62,63,66,68Study1,69,70,71,72,73,75,76,78, one RCT (from USA) reported negative effects59 and nine RCTs (from USA, Italy, France and multiple countries: Spain, Chile, Colombia) reported no differenceStudy3,14,60,64,65,67,68,74,77,79. None were in low or middle-income countries. Seventeen of the RCTs reporting positive effects regarding the included messages focusing on the “protect-others” principle were conducted in the USA, five in Europe, and four in Asia (see Supplementary Results 1). The main outcomes that positively affected by the messages focusing on protecting others were social distancing intentions (e.g., motivation to adhere to physical distancing, persuasiveness to self-isolate, avoid social gathering, stay home and keep a physical distance with others), mask wearing intentions, hand washing intentions, diverse-behavioural intentions (intentions that could not be categorized into specific groups, such as contact-avoidance intentions, protective behaviour willingness) and actual behaviours (see Supplementary Results 2).

Behavioural Tools and Mechanisms of Action (MoA) ontology evidence

Six of the nine MINDSPACE contextual influencers were identified across 102 intervention arms. On average, each intervention arm adopted 2.52 MINDSPACE contextual influencers. The four most common MINDSPACE contextual influencers were “Messenger” (n = 33; 32%), “Salience” (n = 96; 94%), “Affect” (n = 42; 41%), “Ego” (n = 43; 42%) (Supplementary Table S4; Supplementary Note 3). The most often applied contextual influencers across the 74 intervention groups focused on protecting others were “Salience” (n = 53; 72%) and “Ego” (n = 32; 43%). “Affect” was also present, however, less frequently (n = 20; 27%).

Twenty-eight of the 93 BCTs were identified across 102 intervention arms. On average, each intervention arm adopted 4.03 behaviour change techniques. The seven most common BCTs identified were “Instruction on how to perform a behaviour” (n = 96; 94%), “Information about health consequences” (n = 84; 82%), “Salience of consequences” (n = 69; 68%), “Information about social and environmental consequences” (n = 28; 27%), “Credible source” (n = 34; 33%), “Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour” (n = 26; 26%) and “Prompts/cues” (n = 18; 18%) (Supplementary Table S5; Supplementary Note 4). Twenty-five of the 28 BCTs identified across the 74 intervention arms focused on protecting others, with the following as the most frequently applied: “Instruction on how to perform a behaviour” (n = 54; 73%), “Information about health consequences” (n = 51; 69%), “Salience of consequences” (n = 44; 60%), “Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour” (n = 19; 26%), “Information about social and environmental consequences” (n = 18; 24%) and “Credible source” (n = 14; 19%).

MoA Ontology applied to 21 of the 24 full-text papers, covering 30 MoA subcategories. On average, each study adopted 3.48 MoAs, with “Behavioural intention” being the most common, followed by “Belief about one’s social environment” and “Mental disposition” (Supplementary Table S6; Supplementary Note 5; Supplementary Table S7).

Cross-country analysis

Due to the lack of data and the inability to perform a meta-analysis to assess the impact of each MINDSPACE contextual influencer and BCT across the USA and European countries, we calculated the Effective Ratio (ER) to strengthen our narrative analysis. In RCTs conducted in the USA, we evaluate the impact of five MINDSPACE contextual influencers (Fig. 2) and nine BCTs (Fig. 3). The most common MoAs were “Behavioural intention” and “Belief about message” followed by “Belief about consequences of behaviour” and “Willingness to comply”. In RCTs conducted in European countries, we evaluate the impact of four MINDSPACE contextual influencers (Fig. 2) and four BCTs (Fig. 3). The most common MoA was “Behavioural intention”, followed by “Motivation”, “Emotion process”, “Evaluative belief about behaviour” and “Belief about control over behaviour”. In RCTs conducted in Japan and Turkey, ER values could not be estimated for either MINDSPACE contextual influencers or BCTs, as there were no ineffective results.

USA: The highest ER was observed for interventions focusing on “Norms” (ER = 6), followed by “Affect” (ER = 3.33), “Salience” (ER = 2.27), “Ego” (ER = 2) and “Messenger” (ER = 0.57). For four MINDSPACE contextual influencers, ER values could not be estimated due to the absence of ineffective results. European countries: The highest ER was observed for interventions focusing on “Salience” (ER = 7.5), followed by “Affect” (ER = 6), “Ego” (ER = 6) and “Norms” (ER = 1). For five MINDSPACE contextual influencers, ER values could not be estimated due to the absence of ineffective results.

USA: The highest ER in interventions pertained to “Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour” (ER = 8), followed by “Salience of consequences” (ER = 4.5), “Information about health consequences” (ER = 4.25), “Instruction on how to perform a behaviour” (ER = 3), “Information about others’ approval” (ER = 2), “Information about social and environmental consequences” (ER = 1.5), “Credible source” (ER = 1.25), “Social support (practical)” (ER = 1) and “Prompts/cues” (ER = 0.29). For six BCTs, ER values could not be estimated due to the absence of effective results. European countries: The highest ER in interventions pertained to “Instruction on how to perform a behaviour” (ER = 9), followed by “Salience of consequences” (ER = 4.5), “Information about health consequences” (ER = 4) and “Prompts/cues” (ER = 1). For 19 BCTs, ER values could not be estimated due to the absence of effective results.

Populations’ characteristics affected by prosocial messages

Demographic characteristics appear to influence how individuals respond to prosocial public health messages encouraging protective behaviours. While seventeen studies either found no significant effects or did not include demographic analysis, six studies identified key predictors of responsiveness, namely age, gender, employment status, political orientation, race, education, and health condition. In particular, older adults, women, individuals in poorer health, more religious individuals, and those with liberal political views were more responsive, showing greater intention to adhere to protective behaviours.

Age emerged as a consistent predictor across multiple studies. Older individuals were more likely to report intentions to engage in protective behaviours such as handwashing, mask-wearing, and social distancing. Browning et al.78 and Capraro and Barcelo62 both found that older age was associated with stronger intentions to follow COVID-19 prevention guidelines (e.g., wearing face coverings). Similarly, Everett et al.14 and Hacquin et al.79 found that older adults were more inclined to adopt behaviours like handwashing and distancing compared to younger individuals. These findings suggest that older populations are more susceptible to prosocial messaging aimed at reducing transmission, possibly due to higher perceived risk and community responsibility. No studies in our review reported older age as a negative predictor.

Gender also played a role, with women generally reporting stronger behavioural intentions and greater responsiveness to messaging compared to men. Pink et al.60 found that women increased their intention to comply after viewing prosocial messages more than men. Hacquin et al.79 and Everett et al.14 similarly identified women as more likely to engage in handwashing and other protective behaviours. However, Capraro and Barcelo62 found that this gender difference reduced when mask-wearing became mandatory, suggesting external regulations may override gender-based behavioural patterns.

Health status influenced message effectiveness, particularly among individuals in poorer health or at higher risk of infection. Falco and Zaccagni61 found that these individuals were more likely to be influenced by messages emphasizing the protection of others, such as family members. Conversely, those in good health or who frequently left their homes were less impacted by such messages.

Political orientation was a consistent factor influencing behavioural intentions. Individuals who identified as more liberal or left-leaning tended to show greater behavioural intentions following exposure to prosocial messages (Capraro and Barcelo62; Pink et al.60). In contrast, those who identified as conservative or right-leaning were generally less responsive, reporting lower behavioural intentions and a reduced sense of personal responsibility to prevent the spread of disease (Everett et al.14).

Religiosity was also associated with behavioural intentions. Religious individuals reported stronger intentions to engage in protective behaviours. According to Everett et al.14, religiosity was linked to greater perceived responsibility and motivation to follow public health guidance, suggesting that religious values may align with collective-oriented health behaviours.

Employment status, though less frequently studied, appeared to play a role in behavioural intentions. Browning et al.78 found that individuals in less secure employment were more likely to report higher intentions to engage in COVID-19 preventive behaviours. This suggests that perceived vulnerability or instability may heighten sensitivity to public health messaging.

The role of education in behavioural intentions was more complex. Hacquin et al.79 reported that individuals with lower education levels tended to show greater responsiveness to prosocial messaging and higher intentions to follow protective behaviours such as handwashing. However, in some instances, higher education levels were associated with lower behavioural intentions, indicating a nuanced relationship.

Ethnicity also seems to be a recurring factor. Browning et al.78 reported that individuals identifying as White or White/Indigenous demonstrated lower intentions to engage in preventive behaviours. Similarly, Everett et al.14 found that White-identifying individuals reported weaker behavioural intentions and felt less personally responsible for preventing disease transmission.

Risk of bias

Agreement between the two independent raters in coding the risk of bias criteria was high (91,7%). Overall, we noted a high level of some concerns, which was the result of insufficient reporting of an appropriate analysis used to estimate the effect of assignment to the intervention. An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis that includes all randomised participants was lacking, resulting in some concerns in all studies. Further, some of the studies did not publish a protocol or register the studies on trial registries, making it difficult to assess reporting bias, and this led to downgrading of the evidence quality for the large majority of the included intervention types. The studies were assessed as low risk of bias for the domains “bias arising from the randomisation process”, “bias due to missing outcome data” and “bias in measurement of the outcome”. Only one study assessed as high risk of bias due to missing outcome data (Fig. 4; Supplementary Data 4).

Network meta-analysis

Twenty-one RCTs with behavioural intention outcomes (social distancing, mask wearing, handwashing and diverse-behavioural intentions) were considered for quantitative analyses. None of the studies with actual behaviour outcomes met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Nineteen RCTs (n = 30 intervention arms (prosocial messages focused on public and loved ones; self-focused messages); n = 19 comparator groups) were included in the class-effects model, including multiple behavioural intention outcomes except for the handwashing intentions outcome, due to inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence. There was a small increase in personal protective behavioural intentions for each intervention group (prosocial messages and self-focused messages) compared to the control group (no message, baseline message or self-protection message), based on effect estimates of standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CrI. Although the effects of all three intervention messages were small compared to the control and closely comparable to each other, prosocial messages focused on loved ones showed a slightly higher effect size (d = 0.09, 95% CrI 0.06 to 0.14, CINeMA: Low). Additionally, the 95% Crl for the comparison between prosocial messages focused on loved ones versus control did not cross 0, indicating that a positive association between prosocial messages focused on loved ones compared to the control group exists in the population of interest. There was relatively low heterogeneity (SD = 0.07, 95% CrI 0.04 to 0.11), therefore, there was limited variability between studies in the analysis. The mean value of the total residual deviance (69.52) was similar to the number of data points (65) in the analysis, which indicates a reasonable fit (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S6).

Subgroup Network Meta-analyses by behavioural intention outcomes

There was no inconsistency identified between direct and indirect evidence for social distancing intentions (design-by-treatment interaction model: χ2(6) = 3.704, p = 0.717), mask wearing intentions (design-by-treatment interaction model: χ2(4) = 4.585, p = 0.333), diverse-behavioural interventions (design-by-treatment interaction model: χ2(3) = 0.140, p = 0.987). However, there was evidence of inconsistency for handwashing intentions (design-by-treatment interaction model: χ2(3) = 9.115, p = 0.028). Local testing of evidence loops identified a statistically significant difference between direct and indirect evidence for the comparison between prosocial public messages and prosocial loved ones messages (d = 0.618, 95% CrI 0.04 to 1.19; p = 0.03).

Effects on social distancing intentions

Thirteen RCTs were included in the random-effects NMA. There was a small increase in social distancing intentions for each intervention group compared to the control group. While the effects were small, the prosocial message focused on loved ones showed a slightly higher effect size (d = 0.10, 95% CrI 0.04 to 0.16, CINeMA: Moderate) than the prosocial message focused on the public. There was insufficient data to estimate an effect for the self-focused message (Supplementary Table S8; Supplementary Figs. S2, S7).

Effects on mask wearing intentions

Four RCTs were included in the random-effects NMA. Each intervention group showed a small increase in mask-wearing intentions compared to the control group. Only prosocial messages focused on the public, however, demonstrated a slightly higher, statistically significant effect size (d = 0.16, 95% CrI 0.04 to 0.30, CINeMA: Moderate) (Supplementary Table S9; Supplementary Figs. S3, S8).

Effects on handwashing intentions

Seven RCTs were included in the random-effects NMA. There was a small, however non-statistically significant increase in handwashing intentions for each intervention group compared to the control group, with a slightly higher effect to be observed for prosocial messages focused on loved ones (d = 0.20, 95% CrI −0.15 to 0.52, CINeMA: Low) (Supplementary Table S10; Supplementary Fig. S4; Supplementary Fig. S9).

Effects on diverse-behavioural intentions

Nine RCTs were included in the random-effects NMA. There was a small increase in diverse-behavioural intentions for each intervention group compared to the control group. While the effects were small, the prosocial message focused on loved ones showed a slightly higher effect size (d = 0.17, 95% CrI 0.04 to 0.31, CINeMA: Low) than the prosocial message focused on the public. (Supplementary Table S11; Supplementary Figs. S5, S10) The estimated effect for the self-focused message was not statistically significant.

Component network meta-analyses (CNMA) with Mindspace contextual influencers

Handwashing intention outcomes were excluded due to the inconsistency identified. The CNMA model had a reasonable fit (total residual deviance=57.96 from 59 data points) and low heterogeneity (SD = 0.05, 95% CrI 0.01 to 0.10). Although limited evidence, a small, non-statistically significant increase in personal protective behavioural intentions for interventions that incorporated the “salience” (d = 0.06, 95% CrI −0.04 to 0.16), “affect” (d = 0.06, 95% CrI −0.04 to 0.15) and “ego” (d = 0.05, 95% CrI −0.05 to 0.14) compared to interventions that did not include these contextual influencers was found (Table 2). To reduce potential heterogeneity, separate CNMA for self-focused messages was conducted (Supplementary Table S12 and Supplementary Note 6).

Component network meta-analyses with BCTs

Handwashing intention outcomes were excluded due to the inconsistency identified. The CNMA model had a reasonable fit (total residual deviance = 56.53 from 59 data points)) and low heterogeneity (SD = 0.03, 95% CrI 0.01 to 0.07). A small increase in personal protective behavioural intentions for interventions that incorporated the “information about health consequences” (d = 0.12; 95% Crl 0.03 to 0.28) and the “avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour” (d = 0.19, 95% CrI 0.06, 0.32) compared to interventions that did not include these BCTs was found (Table 3). Separate CNMA for self-focused messages was conducted (Supplementary Table S13 and Supplementary Note 7).

Discussion

Our systematic review supports the premise that public health messages focused on “protect-others” may help to improve respiratory infection control and may be more effective than self-interested messages. We identified 24 full-text articles, comprising 36 RCTs, conducted across 11 countries. Interventions were typically delivered online. An average of three-arm study designs with passive comparators were typically used. The overall quality of included studies was moderate, with only one study rated as ‘high risk of bias’. In particular, 26 of the 36 RCTs found a significant effect of protect-others messages on outcomes such as social distancing intention, mask wearing intention, hand washing intention, diverse-behavioural intentions and actual behaviours.

The NMA results from 21 RCTs support our finding that prosocial messages have a small positive effect on personal protective behavioural intentions. Both types of prosocial messages showed a statistically significant effect on social distancing and diverse behavioural intentions, with messages highlighting loved ones showing slightly higher effectiveness, whereas only prosocial messages focusing on the public produced a statistically significant effect on mask-wearing intentions. None of the message types produced significant changes in handwashing intentions. Notably, while self-focused messages demonstrated a small but statistically significant effect on overall personal protective behavioural intentions in the combined analysis, they did not produce significant effects when outcomes, such as mask-wearing, handwashing, and diverse-behavioural intentions, were analysed separately. This suggests that the influence of self-focused messages may be more diffuse and less behaviour-specific. Thus, their standalone use may offer limited impact and could be deprioritised in future public health campaigns in favour of more targeted or emotionally resonant messaging strategies, such as those based on prosocial appeals. Numerous correlational studies indicate that intentions are associated with behaviour. In particular, current evidence suggests that intentions get translated into action approximately one-half of the time37,80,81,82. For example, Sheeran83 conducted a meta-analysis that encompassed a total of 422 studies from ten previous meta-analyses. The outcome of this analysis revealed a substantial sample-weighted average correlation between intentions measured at one time-point and measures of behaviour taken at a subsequent time-point (r+= 0.53). It is essential to interpret these findings with caution, as reliance on intention measures without robust behavioural follow-up may lead to overly optimistic conclusions about message effectiveness. This highlights the need for interventions that go beyond motivation alone, by fostering enabling environments, incorporating reinforcement strategies, and addressing structural barriers to effectively bridge the intention–behaviour gap.

The systematic review also suggested some demographic characteristics to be predictors of protective behavioural intentions regarding respiratory infections. Women, older people, those having less secure employment, more religious people, liberals or politically left-leaning, and those who are in worse health conditions intend to enact protective behaviours. Moreover, the studies included in our analysis were conducted in high-income countries. Caution is therefore warranted when considering their applicability beyond these settings, highlighting the need for further investigation into the effectiveness of prosocial public health messaging interventions in middle- and low-income countries. Tailoring messages to local contexts and rigorously evaluating their impact in such settings should be an important focus for future research.

This review also examined which MINDSPACE contextual influencers and behaviour change techniques (BCTs) might underlie message effectiveness. Although many effective RCTs included contextual influencers such as “salience,” “affect,” and “ego” according to our narrative synthesis, the CNMA results did not support these findings. None of the contextual influencers were associated with statistically significant effects, although these three showed positive trends. Existing literature suggests that messages which increase the salience of risk can positively influence behaviours such as social distancing and mask-wearing24. Moreover, people are more likely to notice and respond to stimuli that are novel (e.g., messages in flashing lights), accessible, simple (e.g., a snappy slogan), and relevant (e.g., introduced at key moments such as the onset of a disease outbreak)84. For example, digital platforms like Instagram Stories have been shown to effectively disseminate public health messages, engaging diverse audiences and enhancing message memorability85. In addition, ego influences behaviour because individuals are motivated to act in ways that reinforce a positive and consistent self-concept (e.g., seeing themselves as responsible or protective of others). Research shows that appeals to self-image and the desire for social approval can effectively motivate action84,86.

Affect strongly influences decision-making by bypassing deliberative processes and triggering rapid, intuitive responses62,69. Emotional messaging, delivered through images, metaphors, or relatable framing, can increase both engagement and retention84,87. For example, infectious-disease communications that evoke empathy for vulnerable groups have been shown to encourage protective intentions such as self-isolation and social distancing72.

Similarly, although the narrative synthesis identified six BCTs (instruction on how to perform a behaviour, information about health consequences, salience of consequences, information about social and environmental consequences, credible source, and avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour) as potentially important predictors of outcomes, the CNMA provided only partial support for these findings. Specifically, interventions incorporating “information about health consequences” and “avoidance/reducing exposure to cues” were associated with small but statistically significant increases in personal protective behavioural intentions. Theories suggest that associative (such as antecedents), reflective motivational (such as natural consequences and comparison of outcomes) and self-regulatory processes (such as shaping knowledge) BCTs are relevant to successful behaviour change88. In particular, motivation BCTs support behaviour change by strengthening individuals’ intentions and making beliefs or feelings about the behaviour more favourable. Self-regulatory BCTs help individuals manage their thoughts, emotions, and behaviours to achieve goals, enabling them to act on their intentions within changing environments. Associative BCTs, by contrast, can trigger behaviours automatically, without conscious motivation or self-regulation, either aligning with existing goals or operating independently of them89.

Investigating the MoAs through which interventions have their effects on behaviour is key for optimising their outcomes. The most frequently applied MoA through which the BCTs affected population behaviour was “behaviour intention”. Identifying MoAs is crucial to understanding how the interventions change population behaviour.

However, while these elements may enhance the appeal and engagement of public health messages, the current evidence base does not allow for firm conclusions about their effectiveness. Their inclusion should therefore be regarded as exploratory, and further research is needed to determine whether, and under what conditions, these contextual features enhance behavioural impact.

In addition, for the elements that did not demonstrate evidence of effectiveness, this should not be taken to mean they are ineffective in all contexts. Instead, the findings suggest that in the reviewed studies, these components may not have been implemented in ways that were sufficiently strong, salient, or contextually tailored to produce meaningful behavioural change. Their limited impact may reflect issues of message design, delivery context, or audience relevance. Future research should investigate whether these components can be rendered more effective through co-design with target populations, tailored framing, repeated exposure, or integration into multi-component interventions that address multiple motivational pathways.

Our electronic search included four databases of published papers, several databases of “grey” literature. Our hand search involved the use of search engines such as Google Scholar, relevant journals and backward and forward citation searching. We re-ran the same search after a year to include new studies of interest.

Data extraction was initially performed by one reviewer and independently verified by a second. Outcome data were extracted independently by two reviewers, with any discrepancies resolved through discussion with a third reviewer, thereby minimising errors and reducing the risk of bias. All abstracts, regardless of the language of the original studies, were initially screened for eligibility, as all were written in English. However, none of the studies in languages other than English met the inclusion criteria during the screening process.

This review used an empirically developed MINDSPACE checklist and a taxonomy of intervention techniques to code contextual influencers and BCTs, respectively, present in prosocial public health messaging interventions targeting personal protective behavioural intentions and actual behaviours. The MoAs Ontology was also used to identify the MoAs through which the BCTs can affect behaviour. Two coders independently coded all studies for contextual influencers and BCTs, and three coders independently coded the MoAs, which represents a significant strength of the review.

However, it is possible that several MINDSPACE contextual influencers, BCTs, and MoAs were not captured due to inadequate descriptions of interventions. Our analyses were based on the information presented in the published papers and any supplementary materials, though attempts were made to contact study authors for more detailed descriptions. Furthermore, since most interventions targeted multiple behaviours without clearly distinguishing which contextual influencers and BCTs were intended to affect specific behaviours, it was not possible to assess the extent of overlap between MINDSPACE elements and BCTs in this review.

Several additional limitations should be noted. The majority of included studies were one-off interventions, with only two studies conducting longer-term follow-ups. As a result, we were unable to assess whether prosocial public health messaging interventions have effects that extend beyond the immediate post-intervention period. Although the systematic review indicated that certain demographic characteristics may predict protective behavioural intentions in the context of respiratory infections, future research is needed to explore how the “protect others” principle influences behavioural responses across more diverse populations.

As expected, given the diversity of included studies, there was considerable methodological and statistical heterogeneity. Studies employed inconsistent methods of outcome aggregation, used varying metrics, and assessed outcomes at different time points, which limited direct comparability. To address these challenges, we applied the GRADE and CINeMA frameworks to systematically assess—and, where appropriate, downgrade—the certainty of evidence based on factors such as within-study bias, publication bias, indirectness, imprecision, heterogeneity, and incoherence. The use of these tools enhanced the methodological rigour of our review and strengthened the reliability of the NMAs.

Not all eligible studies could be included in the NMAs due to poorly reported results. The small number of studies with adequate data also prevented subgroup analyses (e.g., by population type or outcome assessment), which would have provided a deeper understanding of intervention effectiveness.

In addition, only six studies were designed to examine actual behaviours as their primary outcomes16,59,61,73,75,76. The majority measured intentions to engage in preventive procedures, limiting our ability to assess whether intentions translated into action (behaviour – intention gap37,73,90,91). As a result, a limitation of the network meta-analysis (NMA) presented here is that only studies reporting behavioural intentions could be included, as none provided actual behavioural outcomes in sufficient detail. Although intention is a well-established precursor to behaviour, empirical evidence indicates that intentions translate into action only about half of the time Falco and Zaccagni61, suggesting that a substantial proportion of individuals may not follow through on their intended behaviours. This limitation should be considered when interpreting the effectiveness of prosocial messaging interventions, as reliance on intention-only data may overestimate their real-world behavioural impact. To address this, a narrative synthesis was conducted for each of the personal protective behavioural intentions and actual behaviours. Narrative synthesis goes beyond the act of simply describing the main features of included studies and enables summaries of knowledge related to a specific review question92. However, as noted, gaps between intention and action continue to be a challenge. Future work should prioritise interventions explicitly designed to evaluate behavioural outcomes in order to more accurately assess the impact of prosocial messaging strategies.

Furthermore, most of the included studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022), a period marked by unprecedented uncertainty, rapidly changing policies, and heightened public awareness. As a result, behaviours and messaging observed during this time may not fully reflect more stable, post-acute contexts, which could limit the generalizability of certain findings.

Finally, as all studies included in our analysis were conducted in high-income countries, caution is warranted when generalising the findings to other contexts. Future research should prioritise the evaluation of prosocial messaging interventions in middle- and low-income settings, where cultural, social, and structural factors may influence behavioural responses differently.

Our findings hold meaningful implications for public policymakers and communication experts, particularly regarding how best to communicate complex, uncertain, and sometimes conflicting health information. Strengthening the design of public health messages is vital for improving respiratory infection control and fostering protective behaviours. Evidence from this review suggests that framing messages around social responsibility, especially by highlighting the impact on loved ones (friends, family, and vulnerable community members), can be especially persuasive.

Effective risk communication involves raising public awareness not only about personal consequences but also the broader implications for others’ health. Tailoring prosocial messages requires a nuanced understanding of individual differences in perceived susceptibility, emotional response, and message preference. Framing interventions to help people avoid or reduce exposure to behavioural cues have shown promise in supporting risk-reducing behaviours (Table 4).

Data availability

This systematic review and meta-analysis is based on data extracted from publicly available studies. The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, its supplementary information file and supplementary data files. The characteristics of all included studies are provided in Supplementary Data 2 and 3. The source data for Fig. 1 (PRISMA flow chart) can be found in the Supplementary Information. The source data for Figs. 2 and 3 (ERs of MINDSPACE contextual influencers and behaviour change techniques, respectively) can be found in Supplementary Data 5. The source data for Fig. 4 (risk of bias) can be found in Supplementary Data 4. The source data for Table 1 (network meta-analysis) can be found in Supplementary Data 6. The source data for Tables 2 and 3 (CNMA of MINDSPACE contextual influencers and behaviour change techniques, respectively) can be found in Supplementary Data 6.

References

Holford, D. L., Juanchich, M. & Sirota, M. Ambiguity and unintended inferences about risk messages for COVID-19. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 28, 486–508 (2022).

Morstead, T., Zheng, J., Sin, N. L., King, D. B. & DeLongis, A. Adherence to recommended preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of empathy and perceived health threat. Ann. Behav. Med. 56, 381–392 (2022).

Kim, D. & Lee, Y. J. Vaccination strategies and transmission of COVID-19: Evidence across advanced countries. J. Health Econ. 82, 102589 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Despite vaccination, China needs non-pharmaceutical interventions to prevent widespread outbreaks of COVID-19 in 2021. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1009–1020 (2021).

Perski, O. et al. Interventions to increase personal protective behaviours to limit the spread of respiratory viruses: A rapid evidence review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Health Psychol. 27, 215–264 (2022).

Teasdale, E., Santer, M., Geraghty, A. W., Little, P. & Yardley, L. Public perceptions of non-pharmaceutical interventions for reducing transmission of respiratory infection: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Public Health 14, 589 (2014).

Bish, A. & Michie, S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: a review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 15, 797–824 (2010).

Contreras, G. W. & MEP, M. Getting ready for the next pandemic COVID-19: Why we need to be more prepared and less scared. J. Emerg. Manag. 18, 87–89 (2020).

Smith, J. A. & Judd, J. COVID-19: Vulnerability and the power of privilege in a pandemic. Health Promotion J. Aust. 31, 158–160 (2020).

Moran, M. B. & Sussman, S. Translating the link between social identity and health behavior into effective health communication strategies: An experimental application using antismoking advertisements. Health Commun. 29, 1057–1066 (2014).

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D. & Platow, M. J. The new psychology of leadership: Identity, influence and power. (Psychology Press, 2010).

Haidt, J. The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. (Vintage, 2012).

Bonell, C. et al. Harnessing behavioural science in public health campaigns to maintain ‘social distancing’in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: key principles. Epidemiol. Community Health 74, 617–619 (2020).

Everett, J. A., Colombatto, C., Chituc, V., Brady, W. J. & Crockett, M. The effectiveness of moral messages on public health behavioral intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/9yqs8 (2020).

Shen, L. Targeting smokers with empathy appeal antismoking public service announcements: a field experiment. J. Health Commun. 20, 573–580 (2015).

Grant, A. M. & Hofmann, D. A. It’s not all about me: Motivating hand hygiene among health care professionals by focusing on patients. Psychol. Sci. 22, 1494–1499 (2011).

Penner, L. A., Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A. & Schroeder, D. A. Prosocial behavior: Multilevel perspectives. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 56, 365–392 (2005).

Grimani, A. et al. Effect of prosocial public health messages for population behaviour change in relation to respiratory infections: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 11, e044763 (2021).

Campos-Mercade, P., Meier, A. N., Schneider, F. H. & Wengström, E. Prosociality predicts health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Econ. 195, 104367 (2021).

Balbo, L., Jeannot, F. & Estarague, J. Promouvoir les comportements de santé pro-sociaux : l’association du cadrage du message et de la distance sociale. Décisions Marketing 85, 13–27 (2017).

Curtis, V. et al. How to Set up Government-Led National Hygiene Communication Campaigns to Combat COVID-19: A Strategic Blueprint. BMJ Glob. Health 5, e002780 (2020).

Ghio, D. et al. What influences people’s responses to public health messages for managing risks and preventing disease during public health crises? A rapid review of the evidence and recommendations. BMJ Open 11, e048750 (2020).

Li, M., Taylor, E. G., Atkins, K. E., Chapman, G. B. & Galvani, A. P. Stimulating influenza vaccination via prosocial motives. PloS One 11, e0159780 (2016).

Bokemper, S. E., Huber, G. A., James, E. K., Gerber, A. S. & Omer, S. B. Testing persuasive messaging to encourage COVID-19 risk reduction. PLoS One 17, e0264782 (2022).

Grimani, A. et al. The effect of communication strategies for population behaviour change in relation to infectious disease: a systematic review, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020198874 (2020).

Hutton, B. et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann. Intern. Med. 162, 777–784 (2015).

Appelbaum, M. et al. Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. Am. Psychol. 73, 3–25 (2018).

Cumpston, M. S., McKenzie, J. E., Welch, V. A. & Brennan, S. E. Strengthening systematic reviews in public health: guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd edition. J. Public Health https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdac036 (2022).

Huang, M., Névéol, A. & Lu, Z. Recommending MeSH terms for annotating biomedical articles. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 18, 660–667 (2011).

Methley, A. M., Campbell, S., Chew-Graham, C., McNally, R. & Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 14, 579 (2014).

Higgins, J. P. et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. (John Wiley & Sons, Chichester (UK), 2019).

Haddaway, N. R., Collins, A. M., Coughlin, D. & Kirk, S. The Role of Google Scholar in Evidence Reviews and Its Applicability to Grey Literature Searching. PLoS One 10, e0138237 (2015).

Roe, D. et al. Which components or attributes of biodiversity influence which dimensions of poverty? Environ. Evid. 3, 3 (2014).

Covidence, https://community.cochrane.org/help/tools-and-software/covidence.

Moher, D. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 4, (2015).

Bagozzi, R. P. The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Soc. Psychol. Q. 55, 178–204 (1992).

Conner, M. & Norman, P. Understanding the intention-behavior gap: The role of intention strength. J. Front. Psychol. 13, 4249 (2022).

Sterne, J. A. et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366, l4898 (2019).

Dolan, P. et al. Influencing behaviour: The mindspace way. J. Econ. Psychol. 33, 264–277 (2012).

Thaler, R. H. & Sunstein, C. R. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. (Penguin, 2009).

Vlaev, I., King, D., Dolan, P. & Darzi, A. The theory and practice of “nudging”: changing health behaviors. Public Adm. Rev. 76, 550–561 (2016).

Michie, S., Atkins, L. & West, R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. (Silverback Publishing, 2014).

Michie, S., Van Stralen, M. M. & West, R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 6, 42 (2011).

Michie, S. et al. Behaviour change techniques: the development and evaluation of a taxonomic method for reporting and describing behaviour change interventions (a suite of five studies involving consensus methods, randomised controlled trials and analysis of qualitative data). Health Technol. Assess. 19, 1–188 (2015).

Armitage, C. J. et al. Investigating which behaviour change techniques work for whom in which contexts delivered by what means: Proposal for an international collaboratory of Centres for Understanding Behaviour Change (CUBiC). Br. J. Health Psychol. 26, 1–14 (2021).

Michie, S. et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 46, 81–95 (2013).

Vlaev, I. & Dolan, P. Action change theory: A reinforcement learning perspective on behavior change. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 19, 69–95 (2015).

Michie, S. et al. The Human Behaviour-Change Project: harnessing the power of artificial intelligence and machine learning for evidence synthesis and interpretation. Implement Sci. 12, 121 (2017).

Michie, S. et al. Representation of behaviour change interventions and their evaluation: Development of the Upper Level of the Behaviour Change Intervention Ontology. Wellcome Open Res. 5, 123 (2020).

Martin, J., Chater, A. & Lorencatto, F. Effective behaviour change techniques in the prevention and management of childhood obesity. Int. J. Obes. 37, 1287–1294 (2013).

Rouse, B., Chaimani, A. & Li, T. Network meta-analysis: an introduction for clinicians. Intern. Emerg. Med. 12, 103–111 (2017).

Chaimani, A., Caldwell, D. M., Li, T., Higgins, J. P. & Salanti, G. Undertaking network meta-analyses. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. (eds Higgins, J. P. et al.) (John Wiley & Sons, 2019).

Dias, S., Ades, A. E., Welton, N. J., Jansen, J. P. & Sutton, A. J. Network meta-analysis for decision-making. (John Wiley & Sons, 2018).

Jackson, D., Barrett, J. K., Rice, S., White, I. R. & Higgins, J. P. A design-by-treatment interaction model for network meta-analysis with random inconsistency effects. Stat. Med. 33, 3639–3654 (2014).

Welton, N. J., Caldwell, D., Adamopoulos, E. & Vedhara, K. Mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis of complex interventions: psychological interventions in coronary heart disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 169, 1158–1165 (2009).

Freeman, S. C. et al. Component network meta-analysis identifies the most effective components of psychological preparation for adults undergoing surgery under general anesthesia. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 98, 105–116 (2018).

Nikolakopoulou, A. et al. CINeMA: An approach for assessing confidence in the results of a network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 17, e1003082 (2020).

Papakonstantinou, T., Nikolakopoulou, A., Higgins, J. P. T., Egger, M. & Salanti, G. CINeMA: Software for semiautomated assessment of the confidence in the results of network meta-analysis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 16, e1080 (2020).

Banker, S. & Park, J. Evaluating prosocial COVID-19 messaging frames: Evidence from a field study on Facebook. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 15, 1037–1043 (2020).

Pink, S. et al. The effects of short messages encouraging prevention behaviors early in the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 18, e0284354 (2023).

Falco, P. & Zaccagni, S. Promoting social distancing in a pandemic: Beyond good intentions. PLoS One 16, e0260457 (2021).

Capraro, V. & Barcelo, H. The effect of messaging and gender on intentions to wear a face covering to slow down COVID-19 transmission. J. Behav. Econ. Policy 4, 45–55 (2020).

Ceylan, M. & Hayran, C. Message Framing Effects on Individuals’ Social Distancing and Helping Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol. 12, 579164 (2021).

Favero, N. & Pedersen, M. J. How to encourage “Togetherness by Keeping Apart” amid COVID-19? The ineffectiveness of prosocial and empathy appeals. J. Behav. Public Adm. 3, 1–18 (2020).

Frias-Navarro, D., Pascual-Soler, M., Berrios-Riquelme, J., Gomez-Frias, R. & Caamaño-Rocha, L. COVID–19. Effect of Moral Messages to Persuade the Population to Stay at Home in Spain, Chile, and Colombia. Span. J. Psychol. 24, e42 (2021).

Gillman, A. S., Iles, I. A., Klein, W. M. & Ferrer, R. A. Increasing Receptivity to COVID-19 Public Health Messages with Self-Affirmation and Self vs. Other Framing. Health Commun. 38, 1942–1953 (2022).

Heffner, J., Vives, M. L. & FeldmanHall, O. Emotional responses to prosocial messages increase willingness to self-isolate during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pers. Individ Dif. 170, 110420 (2021).

Jordan, J., Yoeli, E. & Rand, D. Don’t get it or don’t spread it: Comparing self-interested versus prosocial motivations for COVID-19 prevention behaviors. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–17 (2021).

Luttrell, A. & Petty, R. E. Evaluations of self-focused versus other-focused arguments for social distancing: An extension of moral matching effects. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 12, 946–954 (2021).

Miller, S., Yardley, L. & Little, P. & team, P. Development of an intervention to reduce transmission of respiratory infections and pandemic flu: measuring and predicting hand-washing intentions. Psychol. Health Med 17, 59–81 (2012).

Miyajima, T. & Murakami, F. Self-interested framed and prosocially framed messaging can equally promote COVID-19 prevention intention: A replication and extension of Jordan et al.’s study (2020) in the Japanese context. Front. Psychol. 12, 1341 (2021).

Pfattheicher, S., Nockur, L., Böhm, R., Sassenrath, C. & Petersen, M. B. The Emotional Path to Action: Empathy Promotes Physical Distancing and Wearing of Face Masks During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Sci. 31, 1363–1373 (2020).

Sasaki, S., Kurokawa, H. & Ohtake, F. Effective but fragile? Responses to repeated nudge-based messages for preventing the spread of COVID-19 infection. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 72, 371–408 (2021).

Utych, S. M. & Fowler, L. Age-based messaging strategies for communication about COVID-19. J. Behav. Public Adm. 3, 1–14 (2020).

Varma, M. M., Chen, D., Lin, X., Aknin, L. B. & Hu, X. Prosocial behavior promotes positive emotion during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emotion 23, 538–553 (2022).

Yardley, L., Miller, S., Schlotz, W. & Little, P. Evaluation of a Web-based intervention to promote hand hygiene: exploratory randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 13, e1963 (2011).

Barari, S. et al. Evaluating COVID-19 public health messaging in Italy: self-reported compliance and growing mental health concerns. MedRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.27.20042820 (2020).

Browning, A., Moss, M. E. & Berkman, E. Leveraging Evidence-Based Messaging to Prevent the Spread of COVID-19. PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/thm2w (2021).

Hacquin, A. S., Mercier, H. & Chevallier, C. Improving preventive health behaviors in the COVID-19 crisis: a messaging intervention in a large nationally representative sample. PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/nyvmg (2020).

Sheeran, P. & Webb, T. L. The intention–behavior gap. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 10, 503–518 (2016).

Manski, C. F. The use of intentions data to predict behavior: A best-case analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 85, 934–940 (1990).

Shmueli, L. Predicting intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine among the general population using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. BMC Public Health 21, 804 (2021).

Sheeran, P. Intention—behavior relations: a conceptual and empirical review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 12, 1–36 (2002).

Smith, H. S. et al. A Review of the MINDSPACE Framework for Nudging Health Promotion During Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Popul Health Manag 25, 487–500 (2022).

Dreibelbis, R., Kroeger, A., Hossain, K., Venkatesh, M. & Ram, P. K. Behavior change without behavior change communication: nudging handwashing among primary school students in Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. public health 13, 129 (2016).

Zahid, N. M., Khan, J. & Tao, M. Exploring mindful consumption, ego involvement, and social norms influencing second-hand clothing purchase. Curr. Psychol. 42, 13960–13974 (2023).

Kite, J., Foley, B. C., Grunseit, A. C. & Freeman, B. Please like me: Facebook and public health communication. PloS one 11, e0162765 (2016).

Black, N. et al. Behaviour change techniques associated with smoking cessation in intervention and comparator groups of randomized controlled trials: A systematic review and meta-regression. Addiction 115, 2008–2020 (2020).

Dixon, D. & Johnston, M. MAP: A mnemonic for mapping BCTs to three routes to behaviour change. Br. J. Health Psychol. 25, 1086–1101 (2020).

Faries, M. D. Why We Don’t “Just Do It”: Understanding the Intention-Behavior Gap in Lifestyle Medicine. Am. J. lifestyle Med. 10, 322–329 (2016).

Sniehotta, F. F., Scholz, U. & Schwarzer, R. Bridging the intention–behaviour gap: Planning, self-efficacy, and action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical exercise. J. Psychol. health 20, 143–160 (2005).

Lisy, K. & Porritt, K. Narrative synthesis: considerations and challenges. JBI Evid. Implement. 14, 201 (2016).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj 372, n71 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Fiona Beyer for her expertise in developing the search strategy, as well as Paulina Schenk, for her contribution to the identification of mechanisms of action. The authors gratefully acknowledge Louise Tanner and Ryan Kenny for their time and consultation regarding the meta-analysis. This study/project is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) [Policy Research Unit in Behavioural Science (project reference PR-PRU-1217-20501)]. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G. is the corresponding author and the primary author of the study, conceived the study, contributed to the development of the search strategy, developed the inclusion and exclusion criteria and data extraction criteria, was involved in the conceptualization of the research questions and conducted the systematic review (behavioural coding and analyses of the results) and meta-analysis. V.A. contributed to the development of the search strategy, was involved in the behavioural coding of the papers and in the meta-analyses, and provided written feedback on the manuscript. N.M. contributed to the Network Meta-analysis and provided written feedback on the manuscript. C.B. conceived the study, contributed to the development of the selection criteria and data extraction criteria, was involved in the conceptualization of the research questions and provided written feedback on the manuscript. S.M. conceived the study and provided written feedback on the manuscript. M.K. contributed to the development of the selection criteria and data extraction criteria and provided written feedback on the manuscript. I.V. conceived the study, contributed to the development of the selection criteria and data extraction criteria, was involved in the conceptualization of the research question and revised the manuscript critically and contributed to it intellectually. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Tracy Epton and Rayane El-Khoury for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grimani, A., Antonopoulou, V., Meader, N. et al. Motivational effectiveness of prosocial public health messaging to reduce respiratory infection risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Commun Med 6, 42 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01296-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01296-6