Abstract

Background

Contraceptive-induced menstrual changes (CIMCs) contribute substantially to women’s dissatisfaction with and discontinuation of contraceptives. We summarised evidence on the prevalence, health impact, treatment, and barriers to accessing treatment for CIMC in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods

Nine databases (MEDLINE, Embase, Emcare, PsycINFO, Global Health, Global Index Medicus, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Scopus) were systematically searched for studies published from January 1, 2000, to December 16, 2024. Eligible studies included reproductive-age women (15–49 years) using any modern contraceptive (excluding barrier and permanent methods) in LMICs. Findings were categorised according to the World Health Organization’s Belsey definitions of frequency and severity of CIMC-related bleeding. Quantitative data were summarised using descriptive statistics and qualitative data using thematic synthesis.

Results

Here we include 321 studies conducted in 44 countries. The prevalence of CIMCs range from 0–94% and vary by contraceptive type. Two-fifths (40.2%) of the prevalence reports did not define the type of CIMC experienced by participants. The most frequently reported health impact of CIMCs is contraceptive discontinuation leading to an unmet need for contraception. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the most frequently investigated treatment. No studies report on the barriers to accessing treatment for CIMCs in LMICs.

Conclusion

CIMC impacts contraceptive users in various ways depending on the contraceptive type and user’s perception of it, highlighting the importance of counselling. Primary research must use standardised definitions of CIMC to improve data quality. Investment in research and development of innovative therapeutics and novel approaches to reducing CIMC is needed to mitigate the unmet need for contraception in LMICs.

Plain language summary

Contraceptives are essential for preventing unplanned pregnancies. However, users may experience changes in their menstrual cycle which may cause dissatisfaction. This study mapped out the most recent research on menstrual changes caused by contraceptives–including how often it occurs, how it impacts users, how it is treated and what hinders treatment–in low and middle-income countries. Our results show that the frequency of menstrual changes caused by contraceptives differed by contraceptive type. These changes cause many women to stop contraceptives making them more likely to have unplanned pregnancies. This highlights the importance of counselling contraceptive users and the need to develop new contraceptive methods that have less influence on the menstrual cycle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contraceptive prevalence using any modern method in women (15–49 years) varies widely between countries, with the lowest rates in low-income countries (31%), followed by lower-middle-income countries (47%), and upper-middle-income countries (72%)1,2,3,4. There are significant health and financial consequences associated with unintended pregnancies, including higher rates of unsafe abortions, increased maternal and child morbidity and mortality, reduced workforce participation, and lower household incomes5,6,7. Adolescent pregnancies can be particularly harmful, leading to girls dropping out of school, lower educational attainment and poverty, in addition to high rates of pregnancy and birth complications8.

For most women, a normal menstrual cycle occurs every 21 to 35 days with bleeding lasting from 2–7 days9. Menstrual changes may include changes in the frequency, regularity of onset, duration of flow, and volume of blood from the normal menstrual cycle as classified by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system for nomenclature of normal and abnormal uterine bleeding10,11. Contraceptive-induced menstrual change (CIMC) is defined as any menstrual change experienced as a direct adverse effect of contraceptive use12. Many contraceptives influence the menstrual cycle and can allow for continued cyclic bleeding (i.e., normal bleeding patterns), or result in partial or complete suppression of the normal cycle13,14,15,16. Using a combined hormonal contraceptive allows for continued cyclic bleeding, though users may experience breakthrough bleeding (spotting or bleeding between periods), while long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) can cause menstrual bleeding to cease completely14.

Adherence to and continuation of modern contraceptive use is necessary to ensure their effectiveness in preventing pregnancy5. However, adverse effects of contraceptives are a major cause of discontinuation or poor compliance with contraceptive use, which increases contraceptive failure rates17. CIMCs have been shown to impact compliance and women’s willingness to use contraceptives17,18,19. A 2019 Cochrane review reported that 32% of women on short-acting hormonal contraceptives are likely to discontinue their use due to menstrual disturbances5. A retrospective analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data from 36 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) from 2005 to 2014 reported that 41% of women who last used a short-acting hormonal contraceptive and 40% who last used a LARC method discontinued use due to side effects and health concerns20.

Despite the suboptimal prevalence of modern contraceptive use in many LMICs, the prevalence of CIMC and its impact on contraceptive discontinuation in these settings have not been systematically synthesised. Also, the accessibility of treatment and management strategies for CIMC in LMICs is unknown. This review aimed to summarise the evidence on the prevalence and health impact of CIMC across LMICs; the current treatments used for its management globally; and the barriers to accessing these treatments in LMICs.

In this review, we find that the prevalence of CIMC ranges widely, varying by contraceptive type. A significant proportion of the prevalence reports do not specify the type of CIMC experienced. Contraceptive discontinuation leading to unmet need for contraception is the most frequently reported health impact of CIMC. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the most frequently investigated treatment for CIMC, and no studies report on barriers to accessing treatment for CIMCs in LMICs.

Methods

We conducted the scoping review following the six-stage process developed by Arksey and O’Malley and further described by Levac et al. 21,22,23. The findings of this review are reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist24 (Supplementary Data 1). We registered the protocol online on Open Science Framework, (registration identifier u5jr8) available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/U5JR8.

Statistics and reproducibility

Search strategy and selection criteria

The search strategy was formulated using the Participants/Population, Concept and Context (PCC) framework25. The participants/population were reproductive-age women (15–49 years) using any form of modern contraceptive (excluding barrier and permanent methods) as defined by the source articles. The concepts explored included the prevalence, health impact, treatment and barriers to accessing treatment. The context considered included studies in countries classified as low-income, lower-middle-income or upper-middle-income according to the 2022 World Bank classification of countries by income level26. For studies providing data on treatment options for CIMC, we included studies regardless of country. We included primary research using the following study designs: interventional trials (randomised and non-randomised trials); observational studies (prospective cohort, retrospective, cross-sectional, and case-control studies); qualitative studies; mixed methods studies; and review of primary research (only systematic reviews and meta-analysis). We did not limit by language of publication but used translation services for papers in a language other than English.

We excluded studies relating to menstrual changes not associated with contraceptive use; those exploring emergency contraceptives, barrier, or permanent methods only; or exploring menstrual suppression. Studies using the following study designs were excluded: case studies, case reports, case series; journal articles that do not present primary data (such as commentaries, letters to the editor, opinion articles); dissertations, conference abstracts, clinical guidelines, clinical trial protocols/registries; other review types (narrative, rapid, and scoping reviews). We also excluded studies where full text articles could not be retrieved.

We developed a search strategy in consultation with an information specialist (LR). We combined search terms relating to contraceptives and menstrual changes and LMICs using search terms related to prevalence, health impact, and barriers to accessing treatment (Supplementary Table S1). When searching for studies related to CIMC treatments, we excluded LMICs from the search terms. We searched nine databases (MEDLINE, Embase, Emcare, PsycINFO, and Global Health (via Ovid); Global Index Medicus; CINAHL via EBSCOhost; Web of Science; and Scopus) for studies published between January 1, 2000 and December 16, 2024 (date of search). We limited the search to studies published from 2000 onwards to ensure the review captured the most recent and relevant evidence. This timeframe reflects a period of significant innovation in contraceptive technologies, including the wider adoption of long-acting reversible contraceptives. While this approach may exclude some earlier seminal studies, our focus was on synthesising evidence aligned with current clinical practice and policy priorities27,28.

Study selection

Two reviewers (MM, JJ, FB, EL, AM, KM, PR or AA) independently screened each title and abstract. After retrieving full texts of potentially eligible studies, two reviewers (MM, LB, JJ, EL, KM, PR, FB, AM, JC) independently screened each article. Any discrepancies in eligibility assessment were resolved by discussion within the review team. All stages of the screening were managed using Covidence software29.

Data extraction and analysis

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Belsey criteria, changes in bleeding patterns with contraceptive use can be categorised as: amenorrhoea (no bleeding or spotting during a 90-day reference period), prolonged bleeding (bleeding or spotting episodes lasting more than 14 days during a 90-day reference period), frequent bleeding (more than 5 bleeding or spotting episodes during a 90-day reference period), infrequent bleeding (1 or 2 bleeding or spotting episodes during a 90-day reference period), and irregular bleeding (3–5 bleeding episodes and less than 3 bleeding or spotting-free intervals of 14 days or more during a 90-day reference period)30,31. These criteria were used for data analysis; however, when definitions were not specified data were categorised as defined by study authors.

A standardised data extraction template was developed in Covidence. The data extracted included characteristics of each study (study designs, country, year); type of contraceptive used, and the data reported (prevalence, health impact, treatment and/or barriers to accessing treatment of CIMCs). Data extraction was conducted independently by any two reviewers (MM, JJ, EL, KM, PR, TG, FB, JC). First, double data extraction was conducted for 82 (25.5%) studies and consensus reached; then single data extraction and cross-checking were done independently for the remaining studies. We employed an explanatory sequential synthesis method to integrate quantitative and qualitative findings. First, quantitative findings were synthesised using descriptive statistics (frequency and percentages) in Microsoft Excel to summarise key trends and patterns. Next, following previously published methods, two reviewers (MM and JC) conducted a thematic synthesis of qualitative findings. This involved line-by-line coding of the extracted data, which were organised into initial codes and iteratively refined to inductively generate and define overarching themes32. The qualitative findings were then used to elaborate on and contextualise the quantitative findings. Integration was conducted through a narrative approach, highlighting areas where qualitative insights clarified or explained trends and patterns observed in the quantitative data. To avoid duplication of data, systematic reviews were excluded from the main analysis. However, we reported the number of systematic reviews addressing each of the key concepts to provide an overview of the evidence base.

Results

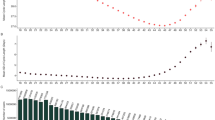

A total of 17,672 records from nine databases were retrieved (Fig. 1). After duplicates were removed 10,037 records were screened at title/abstract stage and 493 were included for full-text screening. Overall, 16 papers could not be retrieved, and 156 articles were excluded at full-text screening (Supplementary Data 2), leaving 321 unique studies for inclusion (Supplementary Data 3).

Characteristics of included studies

There were 42 (13.1%) studies published from 2000 to 2004; 61 (19.0%) from 2005 to 2009; 59 (18.4%) from 2010 to 2014; 57 (17.8%) from 2015 to 2019; and 102 (31.8%) from 2020 to the date of the search. Of the 321 included studies, two-thirds were observational studies (214 studies). This included prospective cohorts (119 studies, 37.1%), retrospective studies (48 studies, 15.0%), cross-sectional studies (44 studies, 13.7%), and a case-control study (3 study, 0.9%). Sixty-two interventional studies included randomised controlled trials (52 studies, 16.2%) and non-randomised trials (9 studies, 2.8%). The remaining studies were qualitative (19 studies, 5.9%), mixed-methods (11 studies, 3.4%), and systematic reviews (16 studies, 5.0%). Prevalence and health impact data were found across all types of study designs. Treatment data were only reported in systematic reviews, randomised trials, non-randomised trials, and prospective cohort studies (Supplementary Fig. S1). No studies were identified that reported on the barriers to treatment of contraception-induced menstrual irregularities. Of the 16 systematic reviews included, nine (56%) reported on treatment, four (25%) reported on health impact and three (19%) reported on the prevalence of CIMC.

The studies reporting data related to the prevalence and health impact of CIMC took place in 44 countries, of which 14 countries had only one study (Supplementary Fig. S2a, Supplementary Table S2). The largest number of studies took place in India (43 studies) and Nigeria (37 studies). In total, 56% (166/297) of prevalence and health impact studies were conducted in lower-middle-income countries, 37% (111/297) in upper-middle-income countries and 7% (20/297) in low-income countries (Supplementary Fig. S2b). For data related to CIMC treatment, 44% (16/36) of studies were conducted in lower-middle-income countries, 31% (11/36) in upper-middle-income countries and 25% (9/36) in high-income countries (Supplementary Fig. S3). There were no studies in low-income countries that reported on CIMC treatment.

Types of contraceptives in the included studies

The types of contraceptives used in the included studies are described in Supplementary Table S3. Implants and intrauterine devices were the most often reported contraceptives, each making up 28.2% (60 studies). Other types included progestin-only contraceptives (47 studies, 22.1%); combined hormonal contraceptive (29 studies, 13.6%); selective oestrogen receptor modulator (Ormeloxifene) (3 studies, 1.4%); and other unspecified contraceptives (14 studies, 6.6%).

Prevalence of contraceptive-induced menstrual changes

Of the 321 included studies, 220 primary studies reported data on the prevalence of CIMC, constituting 521 reports of menstrual changes (Table 1). The number of participants in these studies ranged from 20 to 9262. The overall prevalence of CIMC ranged widely from 0 to 94%, though many reports (233/580, 40.2%) did not define the type of menstrual change experienced. Infrequent bleeding was the least prevalent type of CIMC reported (0 to 60.9%). Studies with a follow-up period of at least one year (106 studies, 47.7%) reported lower prevalence ranges across all types of CIMC. Twenty studies (9.0% of all studies reporting prevalence) included at least 1000 participants and prevalence ranges were narrower. Supplementary Table S4 shows the prevalence by type of contraceptive used and type of CIMC reported. Prevalence varied by contraceptive type; CIMC was more common in users of intrauterine devices and least common in users of combined hormonal contraceptives.

Health impact of contraceptive-induced menstrual changes

We identified 125 primary studies that reported the health impact of CIMC. The number of participants included in these studies ranged from 10 to 9262 participants. Contraceptive discontinuation, reported by 98 (78.4%) studies, was the most frequently reported health impact. However, the proportion of contraceptive discontinuation attributable to CIMC varied across contraceptive types (Supplementary Table S5). Users of intrauterine devices had the highest proportion of discontinuation due to CIMC (up to 100%) and users of ormeloxifene had the lowest proportion of discontinuation (30% from one study) followed by combined hormonal contraceptives (up to 71.9%). The health impacts of CIMC reported by 27 qualitative and mixed-methods studies were synthesised into six themes described below and in Table 2.

Increased economic burden

This included increased economic burden on families due to healthcare costs incurred by unanticipated visits to the hospital and increased need to purchase sanitary products33,34. Women also reported that CIMC impeded their ability to work and earn a living due to difficulty in moving around when bleeding is heavy34,35.

Interference with regular activities

Women reported difficulty in completing everyday household tasks or attend work or school due to fatigue and discomfort from heavy menstrual bleeding36. Women reported need for constant washing, which is particularly challenging for those with limited access to water37. Prolonged and irregular bleeding patterns prevented engagement in religious practices like prayers or handling religious books38,39,40,41.

Experiences of social stigma, shame and exclusion: Women reported experiencing stigma and exclusion due to sociocultural norms and religious beliefs that perceive menstruation as unclean38,42. Some women reported experiencing feelings of shame when their family notice the excessive laundry or when they accidentally bleed in the place of prayer42. Women reported not feeling good about themselves when they were bleeding heavily or for prolonged periods of time37.

Unmet need for contraception

Many women discontinued a contraceptive method due to menstrual irregularity43,44,45. Heavy and prolonged menstrual flow was the most often reported reason for discontinuing contraceptives, with fewer women discontinuing because of amenorrhoea33,35,42,46. When women discontinued a type of contraceptive, they were often reluctant to start or delay starting another contraceptive method, thus increasing the likelihood of unplanned pregnancy35,47. This was also the most frequently reported impact of CIMC from quantitative studies.

Psychological impact

Women reported experiencing psychological stress due to fear of the menstrual side effects of contraceptives, including fear of being pregnant when amenorrhea and fear of expulsion of intrauterine device due to heavy bleeding48. They reported being self-conscious and worried about the possibility of staining their clothes, which was considered shameful42. There were women who had feelings of guilt because they could not contribute to their household tasks such as cooking or tending to livestock because of heavy bleeding42.

Contributes to marital problems

Women reported having problems with their partners due to sexual abstinence because of persistent bleeding34,38. This resulted in sexual dissatisfaction and increased verbal and physical abuse by their partners34,38,42. Some were concerned that because prolonged bleeding prevented them from having sex, their partners will seek sexual satisfaction elsewhere, making them vulnerable to sexually transmitted disease38.

Health concerns: Six studies reported health concerns due to CIMCs35,39,40,49,50,51. There were concerns that heavy bleeding could lead to health issues such as anaemia and exacerbate pre-existing medical conditions35. In particular, women with limited access to quality and nutritious foods worried that the combination of poor nutrition and increased menstrual bleeding would be detrimental to their health49.

Treatment of contraceptive-induced menstrual changes

We identified 36 primary studies reporting on the treatment of CIMC. There were 22 individual drugs reported in the studies identified, 14 of which were only reported by one study (Supplementary Table S6). The most frequently investigated drugs for the treatment of CIMC were non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (18 studies) followed by the antifibrinolytic drug tranexamic acid (9 studies). Other drugs reported were antiprogesterones (5 studies), antibiotics (3 studies), oestrogen (4 studies), combined progestin and oestrogen (3 studies), dietary supplements (3 studies), vitamins (2 studies); and one study each reported the use of an antidiuretic hormone, a selective oestrogen receptor modulator, and a selective progesterone receptor modulator.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not required as no primary data collection was undertaken.

Discussion

This scoping review is the first to map the evidence on the prevalence, health impact, treatment, and barriers to accessing treatment of CIMC across LMICs. We identified 321 studies that reported on one or more of these concepts. The prevalence of the different types of menstrual changes ranged widely across contraceptive types. The most commonly reported health impact or consequence of CIMC was contraceptive discontinuation, which can worsen the unmet need for contraception. There were a limited number of studies that investigated drugs used for the treatment of CIMC. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were the most frequently reported drugs used for the treatment of CIMC. No studies were identified that reported the barriers to accessing treatment for CIMC. The findings build on the existing literature and expand our understanding of the prevalence, health impact, and treatment of CIMC in LMICs. Significant research gaps identified include many primary studies not using standardised definitions for CIMC and short follow-up periods.

We identified many studies that reported the prevalence of CIMC; however, these studies varied widely in the number of participants included (20–9262), the duration of follow-up (1 month to 10 years), and the types of contraceptives used by the participants. Sub-analyses of studies using standard definitions and measurements of CIMC with at least 12 months of follow-up in LMICs yielded less variable prevalence estimates. This highlights the importance of using standardised definitions and measurements of CIMC in primary studies to improve comparison between studies and optimise CIMC data31. Optimising data will support counselling and guide decision making regarding contraceptive choice31.

Consistent with our findings, a 2018 scoping review of data from all countries, which included only 100 English-language studies, reported substantial variation in how women respond to CIMC52. They found that the health impact of CIMC may be influenced by individual and social factors52,53. For example, existing social stigma, socio-cultural norms, and religious beliefs surrounding menstruation may influence how women perceive CIMC12,54. Our review identified a range of economic, psychological, social, and relational impacts on individuals in LMICs. This was particularly the case with heavier, longer or irregular bleeding which increases discomfort, washing, and consciousness of staining clothes; and inhibits participation in regular activities such as work, religious practices, and sex35,38,39,42. CIMC reduces the quality of life of individuals and exacerbates menstrual hygiene management issues (period poverty), including access to water, sanitation, and hygiene facilities, particularly in low-resource settings12,55. Contraceptive discontinuation due to CIMC was the most frequently reported health impact of CIMC. Contraceptive discontinuation significantly contributes to an unmet need for contraception to address unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions, which are more prevalent in lower-resource settings56,57,58.

The health impact of CIMC varies depending on personal beliefs, attitudes towards menstruation, and cultural context59. For example, amenorrhoea associated with contraceptive use may be viewed as a benefit by some and a problem for others33,48,60. Thus, appropriate counselling of clients by healthcare workers could reduce contraceptive dissatisfaction and discontinuation, and decrease the unmet need for contraception41,56,61. Previous studies have suggested a link between the quality of care received at contraceptive initiation and contraceptive continuation rates41,62. Healthcare providers could better support contraceptive users by obtaining more information regarding their client’s perceptions of menstruation and contraception, warning them about side effects and reassuring them about health concerns63,64.

Although we identified 22 drugs for the treatment of CIMC, the number of studies that investigated these drugs was limited, highlighting a significant research gap. Some of the drugs we identified were also included in a 2013 Cochrane review on medical treatments of bleeding irregularities associated with the use of progestin-only contraceptives65. The review concluded that, although promising, there was insufficient evidence to recommend their routine use65. Currently, none of the researched treatment options for CIMC are recommended for long-term clinical use65. Some have suggested that method switching could be employed for the management of CIMC66. Nevertheless, the need to use one drug to treat the side effects of another drug can cause users to abandon contraceptive use altogether. This poses a concern and limits the contraceptive options of many women of reproductive age who may be dissatisfied with the menstrual changes experienced. Research and development into new and innovative contraceptives with negligible effects on the menstrual cycle and/or new therapeutics that can be used for the long-term management of CIMC is therefore paramount12.

We did not identify any studies that reported barriers to accessing treatment in LMICs. This may be because these drugs are commonly used for the management of other conditions and are already widely available and accessible. It is also possible that there are studies that report barriers to accessing these treatment options outside the context of CIMC. More research is needed to elucidate the most effective interventions and strategies to address CIMC. It is also important to explore users’ satisfaction with using these medications to mitigate the side effects of contraceptive use.

Almost half of the included studies did not define the type of menstrual change experienced, which is vital when describing the impact of different contraceptives on the menstrual cycle. For example, for combined hormonal contraceptives, the oestrogen content helps to stabilise bleeding patterns, although breakthrough bleeding occurs in up to 30% of users for the first three to four cycles66,67. Breakthrough bleeding is, however, still reported in up to 10% of users after 12 months of use66. Therefore, defining the type of menstrual change experienced by participants and having longer follow-ups may reduce variations and provide more useful prevalence data. Furthermore, as the data on CIMC relies mainly on self-reporting, the context in which the questions are asked and individual perceptions of CIMC may influence findings. There is, therefore a need for uniformity in how CIMC is measured. Using standardised and validated measures can improve the reliability and quality of data; therefore, future primary research needs to ensure that standard definitions of CIMC are used30,31.

Our review has several strengths. First, we used the Arksey and O’Malley Framework to guide the conduct of the review and the PRISMA ScR checklist to report the findings21,22. Second, two reviewers independently performed data screening and extraction ensuring the integrity of the process. Third, we did not have language limitations ensuring that studies from non-English speaking countries were captured. Lastly, our review focused on LMICs, which have the largest health impact of unmet need for contraception56,57,58.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this review. We did not critically appraise the methodological quality of the included studies. However, this is not a requirement for scoping reviews as our aim was to map and describe the breadth of evidence on CIMC in low and middle-income countries. Furthermore, as our review focuses on descriptive synthesis rather than clinical outcomes, study quality is unlikely to significantly impact on conclusions.

Conclusion

Our review found that CIMC is a major contributor to contraceptive dissatisfaction and discontinuation. However, CIMC has not been the focus of research amidst efforts to improve the uptake of modern contraception12. There is need for research focused on strategies to reduce the health impact of CIMC in low- and middle-income countries. This may include new approaches to contraceptive counselling and new and innovative contraceptives that might reduce CIMC and improve contraceptive satisfaction among clients.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed in this review are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Contraceptive prevalence, any modern method (% of married women ages 15−49 years), https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.CONM.ZS.

Alkema, L., Kantorova, V., Menozzi, C. & Biddlecom, A. National, regional, and global rates and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning between 1990 and 2015: a systematic and comprehensive analysis. Lancet 381, 1642–1652 (2013).

Ba, D. M., Ssentongo, P., Agbese, E. & Kjerulff, K. H. Prevalence and predictors of contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in 17 sub-Saharan African countries: a large population-based study. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 21, 26–32 (2019).

Ponce de Leon, R. G. et al. Contraceptive use in Latin America and the Caribbean with a focus on long-acting reversible contraceptives: prevalence and inequalities in 23 countries. Lancet Glob. Health 7, e227–e235 (2019).

Mack, N. et al. Strategies to improve adherence and continuation of shorter-term hormonal methods of contraception. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004317.pub5 (2019).

Canning, D. & Schultz, T. P. The economic consequences of reproductive health and family planning. Lancet 380, 165–171 (2012).

Yazdkhasti, M., Pourreza, A., Pirak, A. & Abdi, F. Unintended pregnancy and its adverse social and economic consequences on health system: a narrative review article. Iran. J. Public Health 44, 12–21 (2015).

Sidibé, S. et al. Trends in contraceptive use, unmet need and associated factors of modern contraceptive use among urban adolescents and young women in Guinea. BMC Public Health 20, 1840 (2020).

Ussher, J. M., Chrisler, J. C. & Perz, J. Routledge International Handbook of Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health. (Routledge, 2019).

Munro, M. G., Critchley, H. O. & Fraser, I. S. The FIGO systems for nomenclature and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: who needs them?. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 207, 259–265 (2012).

Munro, M. G., Critchley, H. O. D. & Fraser, I. S.FIGO Menstrual Disorders Committee The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 143, 393–408 (2018).

Hoppes, E. et al. Global research and learning agenda for building evidence on contraceptive-induced menstrual changes for research, product development, policies, and programs. Gates Open Res. 6, 49 (2022).

Hillard, P. A. Menstrual suppression: current perspectives. Int. J. Women’s. Health 6, 631–637 (2014).

DeMaria, A. L., Sundstrom, B., Meier, S. & Wiseley, A. The myth of menstruation: how menstrual regulation and suppression impact contraceptive choice. BMC Women’s. Health 19, 125 (2019).

Villavicencio, J. & Allen, R. H. Unscheduled bleeding and contraceptive choice: increasing satisfaction and continuation rates. Open Access J. Contracept. 7, 43–52 (2016).

Stubblefield, P. G. Menstrual impact of contraception. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 170, 1513–1522 (1994).

Dardano, K. L. & Burkman, R. T. Contraceptive compliance. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 27, 933–941 (2000).

Sznajder, K. K., Tomaszewski, K. S., Burke, A. E. & Trent, M. Incidence of discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraception among adolescent and young adult women served by an urban primary care clinic. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 30, 53–57 (2017).

Williamson, L. M., Parkes, A., Wight, D., Petticrew, M. & Hart, G. J. Limits to modern contraceptive use among young women in developing countries: a systematic review of qualitative research. Reprod. Health 6, 3 (2009).

Bellizzi, S., Mannava, P., Nagai, M. & Sobel, H. Reasons for discontinuation of contraception among women with a current unintended pregnancy in 36 low and middle-income countries. Contraception 101, 26–33 (2020).

Arksey, H. & O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32 (2005).

Peters, M. D. et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Health. 13, 141–146 (2015).

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H. & O’Brien, K. K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 5, 1–9 (2010).

Tricco, A. C. et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473 (2018).

Peters, M. D. et al. Scoping reviews. JBI Man. Evid. Synth. 10, 10-46658 (2020).

World Bank. The world by income and region, https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

Jahanfar, S. et al. Assessing the impact of hormonal contraceptive use on menstrual health among women of reproductive age–a systematic review. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 29, 193–223 (2024).

Teal, S. & Edelman, A. Contraception selection, effectiveness, and adverse effects: a review. JAMA. 326, 2507–2518 (2021).

Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia, www.covidence.org.

Belsey, E. M. & d’Arcangues, C. The analysis of vaginal bleeding patterns induced by fertility regulating methods. Contraception 34, 253–260 (1986).

Creinin, M. D., Vieira, C. S., Westhoff, C. L. & Mansour, D. J. A. Recommendations for standardization of bleeding data analyses in contraceptive studies. Contraception 112, 14–22 (2022).

Thomas, J. & Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8, 45 (2008).

Qiu, M. et al. Contraceptive implant discontinuation in huambo and luanda, angola: a qualitative exploration of motives. Matern. Child Health J. 21, 1763–1771 (2017).

Ntimani, J. M. & Randa, M. B. Experiences of women on the use of Implanon NXT in Gauteng province, South Africa: a qualitative study. Health SA Gesondheid 29, a2237 (2024).

Gashaye, K. T. et al. Reasons for modern contraceptives choice and long-acting reversible contraceptives early removal in Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia; qualitative approach. BMC Women’s. Health 23, 273 (2023).

Harrington, E. K. et al. Priorities for contraceptive method and service delivery attributes among adolescent girls and young women in Kenya: a qualitative study. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 01-13, https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2024.1360390 (2024).

Hyttel, M., Rasanathan, J. J. K., Tellier, M. & Taremwa, W. Use of injectable hormonal contraceptives: diverging perspectives of women and men, service providers and policymakers in Uganda. Reprod. Health Matters 20, 148–157 (2012).

Jain, A., Reichenbach, L., Ehsan, I. & Rob, U. Side effects affected my daily activities a lot”: a qualitative exploration of the impact of contraceptive side effects in Bangladesh. Open Access J. Contraception 8, 45–52 (2017).

Brunie, A. et al. Making Removals Part of Informed Choice: A Mixed-Method Study of Client Experiences With Removal of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives in Senegal. Global Health Sci. Practice 10, https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-22-00123 (2022).

Mukanga, B., Mwila, N., Nyirenda, H. T. & Daka, V. Perspectives on the side effects of hormonal contraceptives among women of reproductive age in Kitwe district of Zambia: a qualitative explorative study. BMC Womens Health 23, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02561-3 (2023).

Jain, A. K., Obare, F., RamaRao, S. & Askew, I. Reducing unmet need by supporting women with met need. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 39, 133–141 (2013).

Bradley, J. E., Alam, M. E., Shabnam, F. & Beattie, T. S. Blood, men and tears: keeping IUDs in place in Bangladesh. Cult. Health Sex. 11, 543–558 (2009).

Ferreira, J. M., Nunes, F. R., Modesto, W., Goncalves, M. P. & Bahamondes, L. Reasons for Brazilian women to switch from different contraceptives to long-acting reversible contraceptives. Contraception 89, 17–21 (2014).

Obsa, M. S. et al. Lived experience of women who underwent early removal of long-acting family planning methods in Bedesa Town, Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia: a phenomenological study. Int. J. Women’s. Health 13, 645–652 (2021).

Chin-Quee, D. et al. How much do side effects contribute to discontinuation? A longitudinal study of IUD and implant users in Senegal. Front. Glob. Women’s. Health 2, 804135 (2021).

Tolley, E., Loza, S., Kafafi, L. & Cummings, S. The impact of menstrual side effects on contraceptive discontinuation: findings from a longitudinal study in Cairo, Egypt. Int. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 31, 15–23 (2005).

Zimmerman, L. A. et al. Association between experience of specific side-effects and contraceptive switching and discontinuation in Uganda: results from a longitudinal study. Reprod. Health 18, 1–12 (2021).

Schrumpf, L. A. et al. Side effect concerns and their impact on women’s uptake of modern family planning methods in rural Ghana: a mixed methods study. BMC Women’s. Health 20, 1–8 (2020).

Callahan, R. L. et al. Potential user interest in new long-acting contraceptives: results from a mixed methods study in Burkina Faso and Uganda. PLoS One 14, e0217333 (2019).

Olaifa, B. T., Okonta, H. I., Mpinda, J. B. & Govender, I. Reasons given by women for discontinuing the use of progestogen implants at Koster Hospital, North West province. South Afr. Fam. Pract. 64, a5471 (2022).

Puri, M. C. et al. Exploring reasons for discontinuing use of immediate post-partum intrauterine device in Nepal: a qualitative study. Reprod. Health 17, 1–6 (2020).

Polis, C. B., Hussain, R. & Berry, A. There might be blood: a scoping review on women’s responses to contraceptive-induced menstrual bleeding changes. Reprod. Health 15, 1–17 (2018).

d’Arcangues, C., Jackson, E., Brache, V. & Piaggio, G. Women’s views and experiences of their vaginal bleeding patterns: An international perspective from Norplant users. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 16, 9–17 (2011).

Plesons, M. et al. The state of adolescent menstrual health in low- and middle-income countries and suggestions for future action and research. Reprod. Health 18, 31 (2021).

Schmitt, M. L., Wood, O. R., Clatworthy, D., Rashid, S. F. & Sommer, M. Innovative strategies for providing menstruation-supportive water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities: learning from refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Confl. Health 15, 10 (2021).

Jain, A. K. & Winfrey, W. Contribution of contraceptive discontinuation to unintended births in 36 developing countries. Stud. Fam. Plann 48, 269–278 (2017).

Bearak, J. et al. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990–2019. Lancet Glob. Health 8, e1152–e1161 (2020).

Bearak, J. M. et al. Country-specific estimates of unintended pregnancy and abortion incidence: a global comparative analysis of levels in 2015–2019. BMJ Glob. health 7, e007151 (2022).

Nappi, R. E. et al. Women’s attitudes about combined hormonal contraception (CHC) - induced menstrual bleeding changes-influence of personality traits in an Italian clinical sample. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 39, 2189971 (2023).

Mackenzie, A. C. L. et al. Women’s perspectives on contraceptive-induced Amenorrhea in Burkina Faso and Uganda. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 46, 247–262 (2020).

Puri, M. C., Huber-Krum, S., Canning, D., Guo, M. & Shah, I. H. Does family planning counseling reduce unmet need for modern contraception among postpartum women: evidence from a stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial in Nepal. PLoS One 16, e0249106 (2021).

Danna, K. et al. Leveraging the client-provider interaction to address contraceptive discontinuation: a scoping review of the evidence that links them. Glob. Health Sci. Pr. 9, 948–963 (2021).

Dehlendorf, C., Krajewski, C. & Borrero, S. Contraceptive counseling: best practices to ensure quality communication and enable effective contraceptive use. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 57, 659–673 (2014).

Ali, M. M., Cleland, J. G., Shah, I. H. & Organization, W. H. Causes and consequences of contraceptive discontinuation: evidence from 60 demographic and health surveys. (2012).

Abdel-Aleem, H., d’Arcangues, C., Vogelsong, K. M., Gaffield, M. L. & Gülmezoglu, A. M. Treatment of vaginal bleeding irregularities induced by progestin only contraceptives. Cochrane Database System. Rev. (2013).

Foran, T. The management of irregular bleeding in women using contraception. Aust. Fam. Physician 46, 717–720 (2017).

Schrager, S. Abnormal uterine bleeding associated with hormonal contraception. Am. Fam. Physician 65, 2073–2080 (2002).

Chebet, J. J. et al. Every method seems to have its problems”- Perspectives on side effects of hormonal contraceptives in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. BMC Women’s. Health 15, 97 (2015).

Schwarz, J. et al. So that’s why I’m scared of these methods”: locating contraceptive side effects in embodied life circumstances in Burundi and eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Soc. Sci. Med. 220, 264–272 (2019).

Onyango, G. O., Ayodo, G., Smith-Diamond, N. & Wawire, S. Perceptions of contraceptives as factors in birth outcomes and menstruation patterns in a rural community in Siaya county, Western Kenya. J. Global Health Rep. 4, https://doi.org/10.29392/001c.13690 (2020).

Aamir, F., Mahesh, A. & Karim, S. A. To Evaluate the Compliance of Postpartum Intrauterine Contraceptive Device at Jinnah Medical College Hospital. Annals Abbasi Shaheed Hospital Karachi Medical Dental College 23, 79–85 (2018).

Hlongwa, M., Mutambo, C. & Hlongwana, K. ‘in fact, that’s when I stopped using contraception’: a qualitative study exploring women’s experiences of using contraceptive methods in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMJ Open 13, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063034 (2023).

Imbuki, K., Todd, C. S., Stibich, M. A., Shaffer, D. N. & Sinei, S. K. Factors influencing contraceptive choice and discontinuation among HIV-positive women in Kericho, Kenya. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 14, 98–109 (2010).

Suleiman, B. U., Garba, A. Z., Makarfi, U. A., Hauwa, M. N. & Muhammad, A. A. The use of levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system at Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Zaria. Niger. J. Basic Clin. Sci. 14, 30–33 (2017).

Duby, Z. et al. I will find the best method that will work for me”: navigating contraceptive journeys amongst South African adolescent girls and young women. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 9, 39 (2024).

Cartwright, A. F. et al. Contraceptive continuation and experiences obtaining implant and iud removal among women randomized to use injectable contraception, levonorgestrel implant, and copper IUD in South Africa and Zambia. Studies Family Planning, https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12222 (2023).

Abiyo, J. et al. I have come to remove it because of heavy bleeding”: a mixed-methods study on early contraceptive implant removal and the underlying factors in eastern Uganda. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 9, 17 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This review was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-038938). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M., A.R.A.M., A.A., L.B., J.S., P.L., A.M.G. and J.P.V. contributed to the conception and design of the review. A.R.A.M., A.A., A.M.G. and J.P.V. contributed to the acquisition of funds. M.M., A.R.A.M. and L.R. developed the search strategy. M.M., A.R.A.M., J.J., F.B., E.L., J.C., K.M., T.R.G., P.R., A.A., and L.B. performed the study selection and data extraction. M.M. and J.C. performed the data analysis. M.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, revision of drafts and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Michael T. Mbizvo and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Makama, M., McDougall, A.R.A., Jung, J. et al. Contraceptive-induced menstrual changes in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic scoping review. Commun Med 6, 43 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01297-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01297-5