Abstract

Background

The independent and interactive associations of abdominal obesity and fatty acids with the risk of microvascular diseases (MVDs) are still unclear.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study of 88,571 participants aged 40-69 years from the UK Biobank. Plasma fatty acids were quantified at baseline using high-throughput nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and were analyzed in quartiles, with the lowest quartile of each fatty acid subtype as the reference. Cox regression models were employed to assess the associations between fatty acid levels and incident MVDs, with adjustment for relevant covariates.

Results

Over a median follow-up of 13.7 years, higher levels of total polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), n-3 PUFAs, and n-6 PUFAs are associated with a significantly lower risk of MVDs. The hazard ratios (HRs) for the highest versus lowest quartile (Q4 vs. Q1) are 0.81 (95% CI: 0.75-0.87), 0.89 (95% CI: 0.83-0.96), and 0.85 (95% CI: 0.79-0.91), respectively. Conversely, higher levels of saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids are associated with a higher risk of MVDs. Furthermore, an antagonistic additive interaction is observed between n-3 PUFAs and abdominal obesity (RERI: −0.14, 95% CI: −0.25- −0.03).

Conclusion

Higher plasma PUFAs are associated with a lower risk of MVDs. Furthermore, the association between n-3 PUFAs and a lower risk of MVDs is more pronounced among individuals with abdominal obesity. These findings contribute to the limited prospective evidence on the associations between plasma-specific fatty acids and MVDs.

Plain language summary

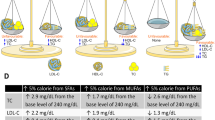

Microvascular diseases (like kidney or nerve issues from small blood vessel damage) are common, and obesity and fatty acids may affect their risks. We studied 88,571 people over 13.7 years to see how belly fat, also termed abdominal obesity (measured by the ratio of waist over hip circumference) and blood fatty acids relate to microvascular diseases risk. We found that higher levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids lowered microvascular diseases risk, while saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids raised it. For people with abdominal obesity, n-3 PUFAs were especially protective. These findings suggest that public health strategies should emphasize the intake of n-3 fatty acids and the management of belly fat, particularly for individuals at risk of microvascular diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microvascular diseases (MVDs), including neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy, are characterized by structural and functional abnormalities in small blood vessels, contributing to substantial global morbidity and mortality1,2,3. The rising prevalence of MVDs parallels the escalating burden of obesity and metabolic disorders, underscoring the need to identify modifiable risk factors4,5.

Abdominal obesity, quantified by waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), is a robust predictor of diabetic MVDs6,7. Epidemiological studies conducted on diabetic cohorts have consistently shown associations between WHR-defined abdominal obesity and the incidence of MVDs8,9,10. Moreover, emerging data from the UK Biobank indicated that WHR-defined central obesity, even in individuals with body mass index (BMI) in the standard range, elevates MVDs risk across glycemic strata11. Similarly, Singaporean studies have demonstrated sex-specific relationships between WHR and the severity of retinopathy in type 2 diabetes patients12. However, current evidence remains confined to diabetic or prediabetic subgroups, with limited generalizability to broader populations. To address this limitation, recent analyses of over 8,000 participants in the Southeast China cohort extended these observations, identifying standard-weight central obesity (defined by WHR) as an independent predictor of MVDs across glycemic strata13. Despite these advances, critical gaps were left in understanding the generalizability of the relationships between WHR-defined obesity metrics and the incident risks of MVDs across broader demographics.

Beyond adiposity metrics, metabolic intermediates like fatty acids may provide complementary insights into the modulation of microvascular risk. Fatty acids, pivotal mediators of metabolic and inflammatory pathways, are categorized into saturated (SFAs), monounsaturated (MUFAs), and polyunsaturated (PUFAs)14. While extensive research has explored the impact of fatty acids on cardiovascular diseases (CVD), their specific associations with MVDs remain less understood. Recent studies have increasingly focused on the role of fatty acid types in MVDs development, though evidence remains inconsistent. For example, a multinational cohort study of 11,140 individuals with type 2 diabetes reported no associations of SFAs, MUFAs, or PUFAs with microvascular complications after multivariable adjustment15. In contrast, a Chinese cohort study identified an inverse association between MUFAs and diabetic retinopathy severity in diabetic populations16. Meanwhile, emerging data suggest protective associations of PUFAs with diabetic nephropathy and diabetic retinopathy17,18,19,20. These discrepancies highlight the need for more research on the subtype-specific associations of fatty acids with MVDs. Notably, it is plausible that the association between plasma fatty acids and MVDs risk may be modified by the presence of abdominal obesity. However, evidence evaluating the interactions between these fatty acids and abdominal obesity in the context of MVDs risk within population-based cohorts remains limited.

Accordingly, this study addresses these gaps by investigating them in a large population-based cohort: (1) independent associations of WHR-defined abdominal obesity and plasma fatty acid subtypes with incident MVDs; and (2) interactions between abdominal obesity and fatty acid profiles in modulating microvascular risks. Overall, our findings provide insights into precision prevention strategies targeting adiposity and dietary lipid composition, thereby significantly informing public health strategies. Here, we found that higher n-3 PUFAs are associated with a lower risk of MVDs, particularly in abdominally obese individuals, whereas SFAs and MUFAs are associated with a higher risk of MVDs.

Methods

Data sources and variables

This study utilized data from the UK Biobank. A comprehensive list of all variables used, including their corresponding UK Biobank field IDs and descriptions, is provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Study populations

We used data from the UK Biobank (application number 90831), a large prospective cohort recruited over 500,000 participants aged 40-69 years between 2006 and 2010 from 22 assessment centers throughout the UK. More detailed descriptions of the UK Biobank have been reported previously21.

This study included 117,687 participants who had complete data on plasma fatty acids, waist circumference (WC), and hip circumference. We then excluded those with cancer (n = 11,340), CVD (n = 4811), MVDs (n = 947), and missing covariates (n = 12,018), leaving 88,571 participants to analyze the associations. Details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1.

The UK Biobank study was approved by the North West Multicentre Research Ethics Committee. All participants signed informed consent before participation.

Assessment of abdominal obesity

WHR was used as a proxy to define abdominal obesity. We classified participants as abdominally obese based on the cut-offs of WHR recommended by World Health Organization (>0.85 for women and >0.90 for men)22. All anthropometric measurements were performed by trained clinical staff following standardized protocols23.

Assessment of plasma fatty acids

Approximately 120,000 plasma samples were randomly selected from the baseline collection (2006–2010). These samples were analyzed in Nightingale Health’s blood biomarker analysis platform based on a high-throughput nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy between June 2019 and April 2020. The detailed protocols of the Nightingale Health NMR biomarker platform and quality control process have been described previously (https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/refer.cgi?id=3001)24,25. The primary exposures were specific plasma fatty acids, including SFAs, MUFAs, total PUFAs, n-3 PUFAs, and n-6 PUFAs, which were expressed as percentages of total plasma fatty acids (% TFA). The biological stability of the plasma biomarker has been validated in a repeat assessment (n = 5000) between 2012 and 2014. The correlation coefficient between plasma fatty acids measured at baseline and those measured at the repeat assessment ranged from 0.5 to 0.6 (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/refer.cgi?id=3003).

Ascertainment of MVDs

In this study, outcomes of interest were MVDs, including nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy, which were identified through linkage with hospital inpatient admission. Supplementary Table 1 provided the International Classification of Diseases codes (ICD-10) used to define MVDs. The time to event was calculated from the date of attending the assessment center to the occurrence of MVDs events (nephropathy, retinopathy, or neuropathy), death, loss of follow-up, or the end of follow-up (i.e., October 31, 2022), whichever came first.

Covariates

The following variables were considered as potential confounding factors based on published literature26,27. Age was calculated as the difference between the date of birth and the date of baseline assessment. Sociodemographic covariates were measured by touchscreen questionnaires or verbal interviews, including sex (female or male), ethnicity (white or others), and education level (no qualification, any other qualification, and university degree or above). Deprivation Index, a score representing the deprivation of the participant’s neighborhood as a reflection of their socioeconomic position, was calculated based on a participant’s postcode and analyzed as a continuous variable.

Lifestyle covariates were also measured by touchscreen questionnaires or verbal interviews. Diet score was assessed based on meeting at least two of three healthy dietary targets related to food types: (1) ≤3 servings/week of red meat and ≤1 serving/week of processed meat; (2) ≥2 servings/week of fish including at least one with oily fish; (3) ≥5 servings/day of fruits and vegetables28. Regular exercise was defined as engaging in ≥150 min/week of moderate activity or 75 min/week of vigorous activity per week (or an equivalent combination), or moderate activity at least 5 days a week or vigorous activity at least 3 days a week (≥10 min continuously at a time)29. Furthermore, alcohol intake (never, previous, current, and <3 times/week, and current and ≥3 times/week), and smoking status (never, previous, and current) were also included as covariates.

The blood biochemical data in the UK Biobank, including markers such as creatinine, were measured in its ISO 17025-accredited central laboratory using enzymatic methods on Beckman Coulter AU5800 analyzers. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from serum creatinine according to Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation30. To ensure accuracy and standardization, the original creatinine values (in µmol/L) were recalibrated to be traceable to standardized reference methods, as recommended by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration, by dividing by a factor of 88.4 to convert to mg/dL prior to the eGFR calculation. Hypertension was defined as systolic pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic pressure ≥90 mmHg, use of medications for blood pressure or self-reported or diagnosed by a doctor31. History of type 2 diabetes was identified using a previously developed algorithm for UK Biobank data, which incorporates self-reported diagnoses, medication use, age at diagnosis, ethnicity-specific cut-offs, and insulin usage to distinguish type 2 diabetes from other types32. Dyslipidemia was derived from the UK Biobank dataset of “first occurrences” (Field ID 130814) containing data obtained from primary care data, hospital inpatient records, death registers, and self-reported medical conditions.

Statistical and reproducibility

The baseline characteristics of participants, categorized by WHR, were presented as mean (standard deviation, SD) for continuous variables and frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables.

The independent associations of abdominal obesity and fatty acids with MVDs were tested using the Cox proportional hazards regression, with results presented as HRs and 95% CI. The proportional hazards assumption was verified by evaluating the Schoenfeld residuals. Participants without abdominal obesity and those in the lowest quartile (Q1) of each fatty acid were used as the reference groups, respectively. Model 1 was adjusted for age (continuous), sex (male/female), ethnicity (White/others), education level (no qualification/any other qualification/university degree or above), and deprivation index (continuous). Model 2 was additionally adjusted for dietary score (meeting <2 targets/≥2 targets), alcohol intake (never/previous/current, <3 times per week/current, ≥3 times per week), smoking status (never/previous/current), and physical activity (inactive/active), with the addition of abdominal obesity (yes/no; for fatty acid analyses only) in models where fatty acids were the exposure. Model 3 was adjusted as Model 2 plus eGFR (continuous), dyslipidemia (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), and type 2 diabetes (yes/no).

To explore whether WHR would modify the associations between plasma fatty acids and MVDs, stratification analyses by WHR were conducted to investigate the associations of fatty acids with incident MVDs. To quantify the additive interactions, each fatty acid was transformed into a binary variable based on its median value. The additive interaction was quantified by calculating the relative excess risk of interaction (RERI), attributable proportion due to the interaction (AP), and synergy index (SI), after adjustment with covariates in Model 3. The RERI represents the absolute risk attributable to additive interaction, and the absence of interaction is indicated by RERI = 0. Values of RERI > 0, AP > 0, and SI > 1 suggest a synergistic interaction, meaning the combined effects of abdominal obesity and fatty acids exceed the sum of their individual effects. The 95% confidence intervals for these metrics were estimated using the delta method33.

We also conducted several sensitivity analyses to ensure the robustness of our findings. Firstly, to further explore the relationship between plasma fatty acids and specific microvascular complications, we conducted analyses stratified by nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy. Secondly, we performed stratified analyses by sex and age to evaluate if these factors modify the relationship between plasma fatty acids and MVDs risk. Thirdly, we conducted further stratified analyses by BMI and WC to explore the potential confounding associations of general and abdominal obesity on the observed associations. Fourth, to assess whether the observed associations are attenuated by reverse causation, we excluded those cases occurring in the first two years of follow-up. Fifth, to address the potential residual confounding by fish oil supplementation, we further adjusted for the supplementation status from the baseline questionnaire. Sixth, considering that C-reactive protein (CRP) could be a potential confounder or a mediator, and the current main models treated CRP as a mediator and therefore did not adjust for it, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis adjusting for CRP as a confounder. Seventh, we performed analysis with imputing missing data of covariates using multiple imputations with a chained equation to test the robustness of the current findings. All analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), primarily utilizing the dplyr, interactionR, and survival packages. All tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

The baseline characteristics of the 88,571 participants, stratified by WHR, are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 55.8 (SD 8.1) years, and 47,459 (53.6%) of the participants were female. Of the participants, 42,017 (47.4%) met WHR criteria for abdominal obesity. Compared to individuals without abdominal obesity, those with abdominal obesity exhibited a higher deprivation index (−1.3 ± 3.1 vs. −1.6 ± 2.9, P < 0.001) and lower adherence to dietary targets (46.7% vs. 57.0%, meeting ≥2 targets, P < 0.001). Plasma fatty acids analysis revealed that participants without abdominal obesity had lower levels of SFAs at 33.7 (SD 1.7) and MUFAs at 22.5 (SD 2.3), but higher levels of PUFAs at 43.8 (SD 3.1), compared to those with abdominal obesity.

Association of abdominal obesity and plasma fatty acids with incident MVDs

During a median follow-up of 13.7 years, 6737 MVDs were recorded. Of these, 2692 occurred in participants without abdominal obesity at baseline, and 4045 occurred in those with abdominal obesity. The proportional hazards assumption was met by evaluation using the Schoenfeld residuals. The abdominal obesity was significantly associated with a higher risk of MVDs (HR:1.20, 95% CI 1.13–1.26), compared with those without abdominal obesity (Supplementary Table 2). The associations of fatty acids with incident MVDs events are shown in Table 2. Participants in the highest quartile (Q4) of SFAs had an 11% higher risk of MVDs (HR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.04–1.19), compared to the Q1 (Ptrend = 0.006). Similarly, Q4 of MUFAs was associated with a 17% higher risk of MVDs (HR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.09–1.26) (Ptrend < 0.001).

As shown in Table 2, higher levels of total PUFAs, n-3 PUFAs, and n-6 PUFAs were conversely associated with a lower risk of MVDs. The total PUFAs in the Q4 was associated with a 19% risk reduction (HR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.75–0.87; Ptrend < 0.001), while n-3 and n-6 PUFAs showed 11% (HR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.83–0.96; Ptrend = 0.003) and 15% (HR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.79–0.91; Ptrend = 0.001) reductions, respectively.

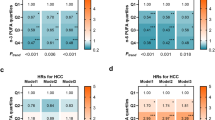

Stratification analyses by abdominal obesity

To further explore the relationship between plasma fatty acids and MVDs, we conducted stratified analyses based on WHR (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 4). The associations between MUFAs and MVDs seemed more evident among participants without abdominal obesity (HR: 1.24, 95% CI: 1.10–1.39) than among those with abdominal obesity (HR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.00–1.25). In contrast, the protective associations of total PUFAs (HR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.72–0.88) and n-3 PUFAs (HR: 0.86, 95% CI: 0.78–0.94) appeared more pronounced among participants with abdominal obesity, although no significant multiplicative interaction was observed.

Stratification was based on waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), with abdominal obesity defined as WHR > 0.85 for women and WHR > 0.90 for men. The study included 46,554 participants without abdominal obesity and 42,017 participants with abdominal obesity. Panels display hazard ratios (HRs) for MVDs across quartiles of a SFAs, b MUFAs, c total PUFAs, d n-3 PUFAs, and e n-6 PUFAs. Points indicate HRs derived from Cox proportional hazards models, and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The regression analysis was adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation index, education level, dietary score, alcohol, smoking status, physical activity, eGFR, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes.

Additive interaction of fatty acids and abdominal obesity on MVDs risk

We further assessed additive interactions between fatty acids and abdominal obesity on the risk of MVDs (Table 3). An antagonistic additive association was observed for n-3 PUFAs (RERI: −0.14, 95% CI: −0.25 to −0.03; AP: −0.12, 95% CI: −0.22 to −0.03; SI: 0.49, 95%CI: 0.31–0.79), indicating that the protective association of n-3 PUFAs with incident MVDs appeared more pronounced among participants with abdominal obesity. No additive interactions were detected for SFAs, MUFAs, total PUFAs, or n-6 PUFAs.

Sensitivity analyses

To ensure the robustness of our results, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, SFAs and MUFAs showed positive associations with nephropathy and neuropathy, whereas inverse associations were observed for total PUFAs and n-6 PUFAs with both conditions, and for n-3 PUFAs with nephropathy alone. No fatty acid subtype was significantly associated with retinopathy (Supplementary Data 2). Second, stratified analyses by sex and age showed that while the inverse associations of MUFAs, total PUFAs, and n-6 PUFAs with risks of MVDs were significantly modified by age (Pinteraction < 0.005) and the association of total PUFAs with MVDs differed by sex (Pinteraction = 0.03), sensitivity analyses replacing WHR with BMI and WC revealed no significant modification of the relationships between these fatty acids and microvascular risks (Supplementary Data 3). Furthermore, the primary findings were not substantially altered by excluding the first two years of follow-up (Supplementary Table 5), additionally adjustment for fish oil supplementation (Supplementary Table 6), or CRP (Supplementary Table 7), and performing a complete-case analysis without imputing missing covariate data (Supplementary Table 8).

Discussion

This UK Biobank cohort study demonstrated that elevated plasma SFAs and MUFAs were independently associated with an increased risk of MVDs, whereas total PUFAs were protective. Notably, an antagonistic additive interaction between n-3 PUFAs and abdominal obesity was observed in relation to MVDs risk. These findings highlight the importance of integrating abdominal adiposity management with dietary fatty acid modulation in strategies for the prevention of MVDs.

Unlike previous studies, this population-based cohort investigated plasma fatty acid levels and their associations with microvascular complications in the general population34,35. Our findings demonstrate that elevated plasma SFAs are significantly associated with higher risks of both neuropathy and nephropathy (Supplementary Data 2). However, regarding retinopathy, our results indicated that SFAs did not have a significant association, which was inconsistent with previous findings in specific subgroups36,37. This discrepancy may reflect the heterogeneity in metabolic status, disease progression, and mechanisms of microvascular damage across different populations. For example, diabetic patients, due to their chronic hyperglycemia, may be more sensitive to the metabolic abnormalities of SFAs, thereby increasing the risk of retinopathy38. In contrast, in the general population, SFAs may primarily affect the microvasculature of the nerves and kidneys through other pathways, such as inflammation or endothelial dysfunction, with a weaker impact on the retina39.

In contrast to the consistent observational data linking dietary intake of MUFAs to a lower risk of CVD and mortality40,41, the present study found that higher plasma levels of MUFAs were associated with a higher risk of MVDs in the general population. One possible explanation for this paradox lies in the dietary sources of MUFAs. Emerging evidence critically distinguishes plant-derived MUFAs (MUFA-Ps, e.g., from olive oil and nuts) from animal-derived MUFAs (MUFA-As, e.g., from red meat, full-fat dairy). MUFA-Ps are associated with a lower risk of coronary heart disease, particularly when substituting saturated fats or refined carbohydrates, whereas MUFA-As show no such benefit and may even increase risk30. This interpretation is further supported by our supplementary data on weekly food consumption (Supplementary Table 3). Specifically, participants in the highest plasma MUFAs quartile reported higher consumption of red and processed meats and lower intake of fruits and vegetables than those in the Q1, which may provide evidence for the need to differentiate between dietary sources of MUFAs when evaluating their associations with vascular outcomes. Therefore, our findings challenge the simplistic view of MUFAs as a uniformly beneficial nutrient. We suggest that in a general population, elevated plasma MUFAs likely serves as a biomarker of a diet high in animal fats and low in plant foods, explaining its association with higher MVDs risk. This underscores that the health impact of fatty acids cannot be evaluated in isolation but must be considered within the context of overall dietary patterns and specific food sources.

Previous studies have mostly focused on the independent associations between fatty acids and subtypes of MVDs, without considering the potential modifying effects of obesity status on these associations42,43. Given the clinical importance of understanding exposure effects across different risk strata, we specifically investigated potential effects between fatty acids and abdominal obesity on MVDs risk. In the present study, we observed a significant inverse association between plasma n-3 PUFAs levels and the overall risk of MVDs. Participants in the Q4 of n-3 PUFAs had an 11% lower risk of MVDs compared to those in the Q1 (HR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.83–0.96). Further analysis revealed tissue-specific associations: n-3 PUFAs were inversely associated with nephropathy (Q4 vs. Q1: HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.73–0.90), whereas no significant associations were observed for neuropathy or retinopathy. This finding aligns with a recent pooled analysis of 19 cohorts, which indicated that higher levels of marine-derived n-3 PUFAs were associated with a reduced risk of chronic kidney disease and a slower decline in renal function44. However, consensus on the renoprotective effects of n-3 PUFAs remains elusive. For instance, some studies have reported no clear protective effects of n-3 fatty acids on renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes45. A 36-month cohort study of patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy also found that dietary n-3 PUFAs intake was not associated with a renoprotective benefit46. These seemingly contradictory results suggest that the observed associations of n-3 PUFAs may be influenced by various factors, including population characteristics, disease stage, and the form of intervention. Although our study did not find significant associations between n-3 PUFAs and retinopathy or neuropathy, this does not entirely preclude their potential role. The development of microvascular complications is tissue-specific, and different organs may exhibit fundamental differences in their response to fatty acid metabolism. The kidney, as a highly perfused organ, might be more sensitive to the potential anti-inflammatory and endothelial actions of n-3 PUFAs, which may underlie the stronger association observed. Furthermore, plasma n-3 PUFAs levels reflect the combined outcome of long-term dietary intake and endogenous metabolism, and their associations may be modulated by other dietary components, genetic background, and the stage of complications.

Mechanistically, n-3 PUFAs possess multiple biological effects, including lipid regulation, blood pressure reduction, antithrombotic effects, anti-inflammatory, and cardiovascular protective actions47. These properties are particularly important in the context of obesity, as chronic low-grade inflammation associated with obesity is a significant risk factor for metabolic CVDs48. Studies have shown that n-3 PUFAs, through their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, can reduce cardiac autonomic sympathetic nerve activity in rats, thereby lowering cardiovascular risk49. In vitro and human studies further indicate that ω-3 PUFAs help reduce levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, which are typically elevated in obesity50. Overall, numerous prospective studies and meta-analyses suggest that n-3 PUFAs supplementation may significantly reduce coronary heart disease risk by 15–25%, with the specific magnitude varying according to study population and design51.

Notably, we also identified a significant antagonistic additive interaction between n-3 PUFAs and abdominal obesity on the risk of MVDs (RERI: −0.14, 95% CI: −0.25 to −0.03). This suggests that higher n-3 PUFAs levels may partially offset the microvascular risks associated with obesity among individuals with abdominal obesity. This finding holds important clinical implications, indicating that increasing n-3 PUFAs levels might help alleviate the burden of microvascular complications in abdominally obese individuals. The protective mechanisms of n-3 PUFAs may involve their anti-inflammatory properties, improvement of endothelial function, regulation of lipid metabolism, and inhibition of oxidative stress, among others52. In the development of microvascular complications such as diabetic nephropathy, chronic low-grade inflammation and endothelial dysfunction are key pathological processes53,54. N-3 PUFAs can promote inflammation resolution and improve vascular reactivity through metabolites like resolvins and protectins, thereby exerting protective effects55,56. It is noteworthy that the protective effects of n-3 PUFAs was more pronounced in the abdominally obese group in our study, possibly because this subgroup generally exhibits a stronger inflammatory state and more severe metabolic disturbances, allowing n-3 PUFAs to exert a greater modulating effect in this high-risk subset.

When interpreting our findings, a critical consideration is the differential relationship between dietary intake and circulating plasma levels across fatty acid subtypes. This has direct bearing on the translation of our results into dietary guidance. Plasma phospholipid levels of long-chain n-3 PUFAs are considered robust biomarkers of their dietary intake, as endogenous synthesis is limited in humans57,58. This biological rationale strengthens the inference that higher plasma n-3 PUFAs, associated with lower MVDs risk, reflect beneficial dietary intake, thereby supporting the inclusion of fatty fish or n-3 supplements. In contrast, the interpretation of plasma SFAs and MUFAs is more complex. Their circulating concentrations are not only influenced by diet but are also significantly affected by endogenous metabolic processes59. Notably, de novo lipogenesis, the synthesis of SFAs and MUFAs from carbohydrates, is upregulated in conditions of excess energy intake and insulin resistance60. Consequently, elevated plasma SFAs and MUFAs levels may serve as an integrated marker of both direct dietary intake and, perhaps more importantly, an underlying dysmetabolic state driven by excessive carbohydrate consumption and abdominal obesity. Therefore, while our data robustly link plasma fatty acid profiles to MVDs risk, deriving specific intake recommendations for SFAs and MUFAs is less straightforward. These findings underscore the importance of focusing on overall dietary patterns to improve metabolic health, rather than focusing solely on isolated nutrient targets. This supports the specific recommendation of diets rich in PUFAs, particularly n-3 PUFAs from foods like fatty fish, especially for individuals with abdominal obesity.

Our current study boasts several strengths. For example, the fatty acids data were derived from plasma rather than relying on estimated intakes from dietary questionnaires, thereby enhancing the accuracy of exposure assessment. Furthermore, the prospective population-based study design reduces the likelihood of complications arising from reverse causality, coupled with a large sample size, an extended follow-up duration, and comprehensive information on potential confounding variables. The robustness of our findings was further supported by the consistency of associations across multiple sensitivity analyses. However, several study limitations warrant cautious interpretation of the findings. First, the residual confounding from unmeasured lifestyle factors (e.g., detailed dietary patterns) still existed, although multiple covariates including lifestyle and diet score were adjusted in the association analyses. Second, the generalizability may also vary across ethnicities, as the cohort study of UK Biobank was predominantly comprised of White ethnicity. Third, the single-timepoint fatty acid measurements may introduce exposure assessment error and restrict our ability to evaluate dietary variations or metabolic changes during the follow-up period. However, repeat measurements in a subset of participants showed moderate correlations (0.5–0.6) between measurements taken years apart, indicating stable dietary habits. Future studies are needed to explore the influence of the long-term dynamics of fatty acid profiles on MVDs.

Conclusions

This study found that SFAs and MUFAs were associated with a higher risk of MVDs, whereas total PUFAs (particularly n-3 PUFAs) exhibited protective associations. Notably, higher n-3 PUFAs level demonstrated an antagonistic interaction with abdominal obesity, attenuating obesity-related MVDs risk. These findings underscore the importance of integrating abdominal adiposity control and modulation of dietary fatty acid composition into prevention strategies for MVDs.

Data availability

The UK Biobank data are protected by privacy regulations and governance policies. Access to the raw data requires an application submitted directly to the UK Biobank (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk). The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The source data for Fig. 1 are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

References

Liu, B. Y., Li, L., Cui, H. X., Zhao, Q. B. & Chen, S. F. Analysis of the global burden of CKD-T2DM in young and middle-aged adults in 204 countries and territories from 2000 to 2019: a systematic study of the global burden of disease in 2019. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 217, 111884 (2024).

Hasankhani, M. B., Mirzaei, H. & Karamoozian, A. Global trend analysis of diabetes mellitus incidence, mortality, and mortality-to-incidence ratio from 1990 to 2019. Sci. Rep. 13, 21908 (2023).

Liu, Y. J. et al. Relationship of microvascular complications and healthy lifestyle with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in women compared with men with type 2 diabetes. Clin. Nutr. 43, 1033–1040 (2024).

Bae, J. P., Nelson, D. R., Boye, K. S. & Mather, K. J. Prevalence of complications and comorbidities associated with obesity: a health insurance claims analysis. BMC Public Health 25, 273 (2025).

Li, J., Liu, W., Li, H., Ye, X. & Qin, J.-J. Changes of metabolic syndrome status alter the risks of cardiovascular diseases, stroke and all cause mortality. Sci. Rep. 15, 5448 (2025).

Streng, K. W. et al. Waist-to-hip ratio and mortality in heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 20, 1269–1277 (2018).

Carmienke, S. et al. General and abdominal obesity parameters and their combination in relation to mortality: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 67, 573–585 (2013).

Guo, N. J. et al. Causal relationships of lifestyle behaviours and body fat distribution on diabetic microvascular complications: a Mendelian randomization study. Front. Genet. 15, 1381322 (2024).

Huang, Y. K. et al. Association of BMI and waist circumference with diabetic microvascular complications: a prospective cohort study from the UK Biobank and Mendelian randomization analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 205, 110975 (2023).

Chen, J. H. et al. Investigating the causal association of generalized and abdominal obesity with microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes: a community-based prospective study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 26, 2796–2810 (2024).

Zhong, P. et al. Normal-weight central obesity and risk of cardiovascular and microvascular events in adults with prediabetes or diabetes: Chinese and British cohorts. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 39, e3707 (2023).

Man, R. E. et al. Differential association of generalized and abdominal obesity with diabetic retinopathy in asian patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 134, 251–257 (2016).

Lin, W. et al. Relationship between insulin-sensitive obesity and retinal microvascular abnormalities. Ann. Palliat. Med. 10, 1031–1041 (2021).

Shetty, S. S. & Kumari, S. Fatty acids and their role in type-2 diabetes (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 22, 706 (2021).

Harris, K. et al. Plasma fatty acids and the risk of vascular disease and mortality outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes: results from the ADVANCE study. Diabetologia 63, 1637–1647 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Deciphering the role of oleic acid in diabetic retinopathy: an empirical analysis of monounsaturated fatty acids. Nutr. Metab. 21, 97 (2024).

Won, J. C. et al. gamma-Linolenic acid versus alpha-lipoic acid for treating painful diabetic neuropathy in adults: a 12-week, double-placebo, randomized, noninferiority trial. Diabetes Metab. J. 44, 542–554 (2020).

Li, J. S. et al. Association of n-6 PUFAs with the risk of diabetic retinopathy in diabetic patients. Endocr. Connect 9, 1191–1201 (2020).

Lin, S. P., Chen, C. M., Wang, K. L., Wu, K. L. & Li, S. C. Association of dietary fish and n-3 unsaturated fatty acid consumption with diabetic nephropathy from a district hospital in Northern Taiwan. Nutrients 14, 2148 (2022).

dos Santos, A. L. T. et al. Low linolenic and linoleic acid consumption are associated with chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Plos ONE 13, e0195249 (2018).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779 (2015).

World Health Organization: Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation (2011).

Sanchez-Lastra, M. A. et al. Joint associations of device-measured physical activity and abdominal obesity with incident cardiovascular disease: a prospective cohort study. Brit. J. Sport Med. 58, 196–203 (2024).

Liu, Z. N., Huang, H. K., Xie, J. R., Xu, Y. Y. & Xu, C. F. Circulating fatty acids and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic liver disease mortality in the UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 15, 3707 (2024).

Julkunen, H. et al. Atlas of plasma NMR biomarkers for health and disease in 118,461 individuals from the UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 14, 604 (2023).

Liu, Z., Huang, H., Xie, J., Xu, Y. & Xu, C. Circulating fatty acids and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic liver disease mortality in the UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 15, 3707 (2024).

Zhuang, P. et al. Circulating fatty acids, genetic risk, and incident coronary artery disease: a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf9037 (2023).

Sanchez-Lastra, M. A., Ding, D., Dalene, K. E., Ekelund, U. & Tarp, J. Physical activity and mortality across levels of adiposity: a prospective cohort study from the UK Biobank. Mayo Clin. Proc. 96, 105–119 (2021).

Liu, Y. J. et al. Microvascular burden and long-term risk of stroke and dementia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Affect. Disord. 354, 68–74 (2024).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150, 604–612 (2009).

Sanchez-Lastra, M. A. et al. Joint associations of device-measured physical activity and abdominal obesity with incident cardiovascular disease: a prospective cohort study. Br. J. Sports Med. 58, 196–203 (2024).

Eastwood, S. V. et al. Algorithms for the capture and adjudication of prevalent and incident diabetes in UK Biobank. PLoS ONE 11, e0162388 (2016).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Knol, M. J. A tutorial on interaction. Epidemiol. Methods 3, 33–72 (2014).

Liu, B. Y. et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and diabetic microvascular complications: a Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1406382 (2024).

Tian, S. F. et al. Fish oil, plasma n-3 PUFAs, and risk of macro- and microvascular complications among individuals with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 110, e1687–e1696 (2024).

Sasaki, M. et al. Associations between fatty acid intake and diabetic retinopathy in a Japanese population. Sci. Rep. 13, 12903 (2023).

Sasaki, M. et al. The associations of dietary intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids with diabetic retinopathy in well-controlled diabetes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56, 7473–7479 (2015).

Li, Y. W. et al. Diabetic vascular diseases: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct. Tar. Ther. 8, 152 (2023).

Rao, H. S., Jalali, J. A., Johnston, T. P. & Koulen, P. Emerging roles of dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia in diabetic retinopathy: molecular mechanisms and clinical perspectives. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 620045 (2021).

Estruch, R. et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, e34 (2018).

Guasch-Ferré, M. et al. Dietary fat intake and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in a population at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 102, 1563–1573 (2015).

Elbarbary, N. S., Ismail, E. A. R. & Mohamed, S. A. Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation improves early-stage diabetic nephropathy and subclinical atherosclerosis in pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 42, 2372–2380 (2023).

Rumora, A. E., Kim, B. & Feldman, E. L. A role for fatty acids in peripheral neuropathy associated with type 2 diabetes and prediabetes. Antioxid. Redox Sign. 37, 560–577 (2022).

Ong, K. L. et al. Association of omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids with incident chronic kidney disease: pooled analysis of 19 cohorts. BMJ 380, e072909 (2023).

de Boer, I. H. et al. Effect of vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on kidney function in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 322, 1899–1909 (2019).

Nakamura, N. et al. Dietary intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids and diabetic nephropathy: cohort analysis of the tsugaru study. In Vivo 37, 1890–1893 (2023).

Fassett, R. G., Gobe, G. C., Peake, J. M. & Coombes, J. S. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of kidney disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 56, 728–742 (2010).

Hariharan, R. et al. The dietary inflammatory index, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors and diseases. Obes. Rev. 23, e13349 (2022).

Wei, S. G., Yu, Y., Zhang, Z. H. & Felder, R. B. Proinflammatory cytokines upregulate sympathoexcitatory mechanisms in the subfornical organ of the rat. Hypertension 65, 1126–1133 (2015).

Kalupahana, N. S., Claycombe, K. J. & Moustaid-Moussa, N. n-3 Fatty acids alleviate adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance: mechanistic insights. Adv. Nutr. 2, 304–316 (2011).

Djuricic, I. & Calder, P. C. Beneficial outcomes of omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on human health: an update for 2021. Nutrients 13, 2421 (2021).

Shahidi, F. & Ambigaipalan, P. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Their Health Benefits. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 9, 345–381 (2018).

Donate-Correa, J. et al. Inflammatory targets in diabetic nephropathy. J. Clin. Med. 9, 458 (2020).

Yang, J. & Liu, Z. S. Mechanistic pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction in diabetic nephropathy and retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 816400 (2022).

Zhang, M. J. & Spite, M. Resolvins: Anti-inflammatory and proresolving mediators derived from omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 32, 203–228 (2012).

Serhan, C. N. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature 510, 92–101 (2014).

Serra-Majem, L., Nissensohn, M., Overby, N. C. & Fekete, K. Dietary methods and biomarkers of omega 3 fatty acids: a systematic review. Brit. J. Nutr. 107, S64–S76 (2012).

Marangoni, F. & Poli, A. n-3 fatty acids: functional differences between food intake, oral supplementation and drug treatments. Int. J. Cardiol. 170, S12–S15 (2013).

Annevelink, C. E., Sapp, P. A., Petersen, K. S., Shearer, G. C. & Kris-Etherton, P. M. Diet-derived and diet-related endogenously produced palmitic acid: effects on metabolic regulation and cardiovascular disease risk. J. Clin. Lipidol. 17, 577–586 (2023).

Yu, E. A., Hu, P. J. & Mehta, S. Plasma fatty acids in de novo lipogenesis pathway are associated with diabetogenic indicators among adults: NHANES 2003-2004. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 108, 622–632 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants and professionals contributing to the UK Biobank. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 82173519, 82473721, and 81500330) as well as the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFC2503605).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ruidie Shi and Lan Yu contributed equally to this work, wrote the manuscript and researched the data. Ruidie Shi, Lan Yu, Shengnan Liu, and Guangbin Sun were involved in data management and analysis. Dongfang Zhang, Xinyue Li, Qiang Zhang, Xiaolong Xing, Xumei Zhang, and Xueli Yang provided expert knowledge on microvascular diseases and methodology. All authors edited, reviewed, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Xueli Yang is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, R., Yu, L., Liu, S. et al. Associations of abdominal obesity and plasma fatty acids with microvascular diseases. Commun Med 6, 73 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01333-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01333-4