Abstract

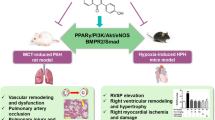

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) is a rare form of pulmonary hypertension arising from EIF2AK4 gene mutations or mitomycin C (MMC) administration. The lack of effective PVOD therapies is compounded by a limited understanding of the mechanisms driving vascular remodeling in PVOD. Here we show that administration of MMC in rats mediates activation of protein kinase R (PKR) and the integrated stress response (ISR), which leads to the release of the endothelial adhesion molecule vascular endothelial (VE) cadherin (VE-Cad) in complex with RAD51 to the circulation, disruption of endothelial barrier and vascular remodeling. Pharmacological inhibition of PKR or ISR attenuates VE-Cad depletion, elevation of vascular permeability and vascular remodeling instigated by MMC, suggesting potential clinical intervention for PVOD. Finally, the severity of PVOD phenotypes was increased by a heterozygous BMPR2 mutation that truncates the carboxyl tail of the receptor BMPR2, underscoring the role of deregulated bone morphogenetic protein signaling in the development of PVOD.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data supporting the findings in this study are included in the main article and its associated files. All RNA-seq data can be found under the accession number GSE229404 in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Montani, D. et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur. Respir. J. 47, 1518–1534 (2016).

Shackelford, G. D., Sacks, E. J., Mullins, J. D. & McAlister, W. H. Pulmonary venoocclusive disease: case report and review of the literature. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 128, 643–648 (1977).

Eyries, M. et al. EIF2AK4 mutations cause pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, a recessive form of pulmonary hypertension. Nat. Genet. 46, 65–69 (2014).

Best, D. H. et al. EIF2AK4 mutations in pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis. Chest 145, 231–236 (2014).

Morrell, N. W. et al. Targeting BMP signalling in cardiovascular disease and anaemia. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 13, 106–120 (2016).

Morrell, N. W. et al. Genetics and genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 53, 1801899 (2019).

Aldred, M. A., Morrell, N. W. & Guignabert, C. New mutations and pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension: progress and puzzles in disease pathogenesis. Circ. Res. 130, 1365–1381 (2022).

Oriaku, I. et al. A novel BMPR2 mutation with widely disparate heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension clinical phenotype. Pulm. Circ. 10, 2045894020931315 (2020).

Runo, J. R. et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease caused by an inherited mutation in bone morphogenetic protein receptor II. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 167, 889–894 (2003).

Ranchoux, B. et al. Chemotherapy-induced pulmonary hypertension: role of alkylating agents. Am. J. Pathol. 185, 356–371 (2015).

Perros, F. et al. Mitomycin-induced pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: evidence from human disease and animal models. Circulation 132, 834–847 (2015).

Doll, D. C., Ringenberg, Q. S. & Yarbro, J. W. Vascular toxicity associated with antineoplastic agents. J. Clin. Oncol. 4, 1405–1417 (1986).

Manaud, G. et al. Comparison of human and experimental pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 63, 118–131 (2020).

Chen, Z., Zhang, J., Wei, D., Chen, J. & Yang, J. GCN2 regulates ATF3–p38 MAPK signaling transduction in pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 26, 677–689 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Mitomycin C induces pulmonary vascular endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition and pulmonary veno-occlusive disease via Smad3-dependent pathway in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 178, 217–235 (2021).

Vattulainen-Collanus, S. et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling is required for RAD51-mediated maintenance of genome integrity in vascular endothelial cells. Commun. Biol. 1, 149 (2018).

Costa-Mattioli, M. & Walter, P. The integrated stress response: from mechanism to disease. Science 368, eaat5314 (2020).

Donnelly, N., Gorman, A. M., Gupta, S. & Samali, A. The eIF2α kinases: their structures and functions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 70, 3493–3511 (2013).

Ueda, H. et al. Association of the T-cell regulatory gene CTLA4 with susceptibility to autoimmune disease. Nature 423, 506–511 (2003).

Vestweber, D. VE-cadherin: the major endothelial adhesion molecule controlling cellular junctions and blood vessel formation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 223–232 (2008).

Lampugnani, M. G., Dejana, E. & Giampietro, C. Corrigendum: vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin, endothelial adherens junctions, and vascular disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 9, a029322 (2017).

Beard, R. S. Jr. et al. Non-muscle Mlck is required for β-catenin- and FoxO1-dependent downregulation of Cldn5 in IL-1β-mediated barrier dysfunction in brain endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 127, 1840–1853 (2014).

Alam, M. S. Proximity ligation assay (PLA). Methods Mol. Biol. 2422, 191–201 (2022).

Giannotta, M., Trani, M. & Dejana, E. VE-cadherin and endothelial adherens junctions: active guardians of vascular integrity. Dev. Cell 26, 441–454 (2013).

Gugnoni, M. et al. Cadherin-6 promotes EMT and cancer metastasis by restraining autophagy. Oncogene 36, 667–677 (2017).

Lamark, T. & Johansen, T. Mechanisms of selective autophagy. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 37, 143–169 (2021).

Herren, B., Levkau, B., Raines, E. W. & Ross, R. Cleavage of β-catenin and plakoglobin and shedding of VE-cadherin during endothelial apoptosis: evidence for a role for caspases and metalloproteinases. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 1589–1601 (1998).

Pakos-Zebrucka, K. et al. The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep. 17, 1374–1395 (2016).

Romano, P. R. et al. Autophosphorylation in the activation loop is required for full kinase activity in vivo of human and yeast eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinases PKR and GCN2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 2282–2297 (1998).

Singh, M. & Patel, R. C. Increased interaction between PACT molecules in response to stress signals is required for PKR activation. J. Cell. Biochem. 113, 2754–2764 (2012).

Kumar, R. et al. TGF-β activation by bone marrow-derived thrombospondin-1 causes Schistosoma- and hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Nat. Commun. 8, 15494 (2017).

Jammi, N. V., Whitby, L. R. & Beal, P. A. Small molecule inhibitors of the RNA-dependent protein kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 308, 50–57 (2003).

Zyryanova, A. F. et al. ISRIB blunts the integrated stress response by allosterically antagonising the inhibitory effect of phosphorylated eIF2 on eIF2B. Mol. Cell 81, 88–103 (2021).

Rabouw, H. H. et al. Small molecule ISRIB suppresses the integrated stress response within a defined window of activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 2097–2102 (2019).

Zhang, T. et al. Small-molecule integrated stress response inhibitor reduces susceptibility to postinfarct atrial fibrillation in rats via the inhibition of integrated stress responses. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 378, 197–206 (2021).

Anand, A. A. & Walter, P. Structural insights into ISRIB, a memory-enhancing inhibitor of the integrated stress response. FEBS J. 287, 239–245 (2020).

Soubrier, F. et al. Genetics and genomics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62, D13–D21 (2013).

Austin, E. D. & Loyd, J. E. The genetics of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ. Res. 115, 189–202 (2014).

Machado, R. D. et al. Mutations of the TGF-β type II receptor BMPR2 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hum. Mutat. 27, 121–132 (2006).

Long, L. et al. Selective enhancement of endothelial BMPR-II with BMP9 reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat. Med. 21, 777–785 (2015).

Schoof, M. et al. eIF2B conformation and assembly state regulate the integrated stress response. eLife 10, e65703 (2021).

Tian, W. et al. Phenotypically silent bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 mutations predispose rats to inflammation-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension by enhancing the risk for neointimal transformation. Circulation 140, 1409–1425 (2019).

Gal-Ben-Ari, S., Barrera, I., Ehrlich, M. & Rosenblum, K. PKR: a kinase to remember. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11, 480 (2018).

Hon, S. M., Alpizar-Rivas, R. M. & Farber, H. W. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Cardiol. Clin. 40, 45–54 (2022).

Navarro, P. et al. Catenin-dependent and -independent functions of vascular endothelial cadherin. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30965–30972 (1995).

Bonilla, B., Hengel, S. R., Grundy, M. K. & Bernstein, K. A. RAD51 gene family structure and function. Annu. Rev. Genet. 54, 25–46 (2020).

Okimoto, S. et al. hCAS/CSE1L regulates RAD51 distribution and focus formation for homologous recombinational repair. Genes Cells 20, 681–694 (2015).

Plo, I. et al. AKT1 inhibits homologous recombination by inducing cytoplasmic retention of BRCA1 and RAD51. Cancer Res. 68, 9404–9412 (2008).

Chou, A. et al. Inhibition of the integrated stress response reverses cognitive deficits after traumatic brain injury. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E6420–E6426 (2017).

Frias, E. S. et al. Aberrant cortical spine dynamics after concussive injury are reversed by integrated stress response inhibition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2209427119 (2022).

Zhu, P. J. et al. Activation of the ISR mediates the behavioral and neurophysiological abnormalities in Down syndrome. Science 366, 843–849 (2019).

Krukowski, K. et al. Small molecule cognitive enhancer reverses age-related memory decline in mice. eLife 9, e62048 (2020).

Nguyen, H. G. et al. Development of a stress response therapy targeting aggressive prostate cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaar2036 (2018).

Zeng, Q. et al. Clinical characteristics and survival of Chinese patients diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension who carry BMPR2 or EIF2KAK4 variants. BMC Pulm. Med. 20, 150 (2020).

Montani, D. et al. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: clinical, functional, radiologic, and hemodynamic characteristics and outcome of 24 cases confirmed by histology. Medicine 87, 220–233 (2008).

Carraro, V. et al. Amino acid availability controls TRB3 transcription in liver through the GCN2/eIF2α/ATF4 pathway. PLoS ONE 5, e15716 (2010).

Chan, M. C. et al. Molecular basis for antagonism between PDGF and the TGFβ family of signalling pathways by control of miR-24 expression. EMBO J. 29, 559–573 (2010).

Fischer, A. H., Jacobson, K. A., Rose, J. & Zeller, R. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue and cell sections. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot4986 (2008).

Xie, L. W. & Wang, J. Evaluating three elastic-fiber staining methods for detecting visceral pleural invasion in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Clin. Lab. https://doi.org/10.7754/Clin.Lab.2020.200851 (2021).

Rhodes, C. J. et al. Whole-blood RNA profiles associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension and clinical outcome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 202, 586–594 (2020).

Beeton, C., Garcia, A. & Chandy, K. G. Drawing blood from rats through the saphenous vein and by cardiac puncture. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/266 (2007).

Galie, N. et al. Guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. The Task Force on Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 25, 2243–2278 (2004).

Stacher, E. et al. Modern age pathology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 186, 261–272 (2012).

Flomerfelt, F. A. & Gress, R. E. Analysis of cell proliferation and homeostasis using EdU labeling. Methods Mol. Biol. 1323, 211–220 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank R.M. Tuder, A. Gandjeva (University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus) and the PHBI for providing human lung samples and the UK National Cohort of Idiopathic and Heritable PAH for providing human plasma samples. We thank D. Jorgens and R. Zalpuri at the University of California Berkeley Electron Microscope Laboratory for their advice and assistance in experiment planning, electron microscopy sample preparation and data collection. Other microscopy data were acquired at the Center for Advanced Light Microscopy—CVRI Microscopy Core on microscopes. We also thank X. Jiang (San Yat-Sen University), S. Vattulainen-Collanus (Blueprint Genetics), T.A. Desai (UCSF and Brown University), A. Arvind (UCB), S. Gupta (UCSB), S. Dhami (Santa Clara University) and Y. Yao (Tsinghua University) for technical advice and support. We thank K. Ebnet (University of Münster) for the gift of GST-VE-Cad fusion constructs; K. Atabai, B. Wang and G. Huang (UCSF) for sharing reagents; and members of Hata laboratory for critical discussion. Grant funding was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL132058, R01HL153915 and R01HL164581) and the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (28IR-0047) to A.H.; by the American Heart Association (19CDA34730030), the Cardiovascular Medical Research Fund and a United Therapeutics Jenesis Innovative Research Award to R.K.; and by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL135872 and P01HL152961) to B.B.G. N.W.M. is supported by a Programme Grant from the British Heart Foundation (RG/19/3/34265) and a Personal Chair Award (CH/09/001/25945). The UK National Cohort of Idiopathic and Heritable PAH is supported by the British Heart Foundation (SP/12/12/29836), the BHF Cambridge Centre of Cardiovascular Research Excellence and the UK Medical Research Council (MR/K020919/1). The PHBI is supported by the Cardiovascular Medical Research and Education Fund and R24HL123767.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows. Study conception and design: A.P. and A.H. Execution of experiments: A.P., R.K., M.W., C.O.L., J.Z., P.G., Z.Z. and B.N.K. Data analysis: A.P., R.K., M.W., C.O.L., J.Z., P.G., Z.Z. and B.N.K. Interpretation of results: A.P., R.K., M.W., C.O.L., S.G., C.M.T., N.W.M., B.B.G., G.L. and A.H. Primary draft paper preparation: A.P. and A.H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cardiovascular Research thanks Lena Claesson-Welsh, Rienk Nieuwland, Paul Yu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Overexpression of Rad51 prevents MMC-mediated DNA damage, and MMC does not induce apoptosis.

(a) PMVECs (5 × 103 cells) transfected with empty vector (mock) or Rad51 expression plasmid (Rad51) were subjected to the comet assay. The bar graph indicates the levels of DNA damage as a percentage of nuclei with damaged DNA out of total nuclei as mean ± SEM. Approximately one hundred nuclei per condition were examined. n = 5 independent samples. (b) PMVECs (1 × 106 cells) were transfected with empty vector (mock) or Rad51 expression plasmid (+Rad51), followed by vehicle or MMC treatment for 14 h. Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot of VE-Cad, Rad51, γH2AX, and β-actin (control). (c) PMVECs were treated with vehicle (Veh), MMC for 14 h or 0.4 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 2 h, followed by fluorescence staining of Annexin V (green) and DAPI (blue). Annexin V-positive cells’ fraction (%) is shown as mean ± SEM. Scale bar=10 mm Approximately one hundred cells per condition were examined. A similar result was obtained by flow cytometric analysis of FITC-Annexin V staining. The number of Annexin V-positive cells is shown as mean ± SEM. About 300 cells and 1.5 × 106 cells per condition were analyzed by fluorescent staining and flow cytometry. Because of the autofluorescence of PMVECs, the signals of unstained PMVECs were used to set the gate for FITC-Annexin V-positive cells. A green rectangle indicates Annexin V-positive cells. Data are analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (c, d); two-way ANOVA With Tukey’s post-hoc test (a).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Transfer of VE-Cad and Rad51 to PMVECs damaged by MMC and transcriptional activation of ATF4 target genes in MMC-treated PMVECs.

(a) The levels of intracellular VE-Cad, Rad51, and β-actin (loading control) protein in the MMC-treated PMVECs (recipient cells; 1 × 106 cells) after the incubation with the CM from PMVECs (1 × 106 cells) treated with vehicle (CMveh) or MMC (CMMMC) for 14 h were examined by immunoblot analysis. (b) IF staining of PMVECs treated with CMveh or CMMMC (5 × 103 cells) with an anti-VE-Cad antibody (green). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar=10 mm. (c) CM was collected from PMVECs following two h of MMC treatment and was immediately reintroduced to the donor cells’ CM after MMC was removed from the CMMMC (-MMC, indicated in red), or it was added without removing MMC ( + MMC, indicated in blue). Duplicate samples were used. Non-specific IgG (IgG) was used as a negative control for IP. Subsequently, following a 14 h incubation period, the VRC amount in the donor cells was evaluated. (d) RNA-seq data (MMC 0 h vs 4 h) is plotted on a volcano map. X-axis and Y-axis indicate p-value (-Log10) and fold change (FC) (Log2). Annotated red dots indicate known ATF4 targets. n = 3 independent RNA samples per condition. Data are analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (c).

Extended Data Fig. 3 The analysis of apoptotic cells by Annexin V staining and PH phenotypes in Schistosomia-induced PH (Sch-PH).

(a) Schematic description of the experimental procedure. Lung samples of WT rats treated with vehicle or MMC were harvested on days 8, 16, and 24. IF staining of the apoptosis marker Annexin V (green) and CD31(red) for vascular endothelial cells. Hoechst (blue) is showing nuclei. Annexin V and CD31 stain images were merged and displayed in the “Merge” row. The intensity of the Annexin V signal in the CD31-positive endothelial layer was quantitated by ImageJ and shown as mean ± SEM. n = 4–7 independent samples per condition. White asterisks indicate pulmonary arteries. Scale bar= 10 μm. (b) Right ventricular (RV) systolic pressure (RVSP) and RV to left ventricular (LV)+septum weight ratio (RV/LV + S) were measured in control, Sch-PH, and CH-PH mice and shown as mean ± SEM. n = 5 independent samples per group. (c) The RVSP and RV/LV + S ratio in a vehicle or MCT-administered rats were measured and shown as mean ± SEM. n = 7–10 independent samples per group. Data are analyzed by two-sided unpaired student’s t-test (b, c); one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (a).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Characterization of heterozygous BMPR2 mutant rats.

(a) The top 2 panels show BMPR2 gene sequencing results of E503fs (∆2/+) rat and Q495fs (∆26/+) rat, where the bases shown in red or in the red rectangle are mutations introduced. Blue letters show the protein sequence after the mutation. Asterisks indicate stop codons. (b) WT or Mut cells were treated with increasing concentrations of BMP4 for 2 h, and total cell lysates from 1 × 106 cells were subjected to immunoblot with anti-phospho-Smad1/5/8 (p-Smad1/5/8), anti-total Smad1 (t-Smad1), anti-GAPDH (loading control), and anti-BMPR2(CTD) antibody. (c) WT or Mut cells (1 × 106 cells) were treated with 100 pM of BMP4 for the indicated time (h), and total cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot with anti-p-Smad1/5/8, anti-t-Smad1, anti-GAPDH (loading control), and anti-BMPR2(CTD) antibody. Total RNAs isolated from the same cells were subjected to qRT-PCR of BMP-Smad1/5/8 target genes, Id3 and Smad6. Levels of Id3 and Smad6 mRNAs relative to GAPDH are shown by mean ± SEM. n = 3. Data are analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (c).

Extended Data Fig. 5 ISRIB does not affect the p-eIF2α amount, PH phenotypes in males and females are indistinguishable, physiological measurements of WT and Mut rats and lack of vascular remodeling and ISR activation in the heart and liver after MMC treatment.

(a) Lung lysates from vehicle-, MMC-, or MMC + ISRIB-treated WT and Mut rats were subjected to immunoblot analysis of p-eIF2α, t-eIF2α, and β-actin (loading control) in triplicate. n = 3 independent samples per condition. (b) p-eIF2α /t-eIF2α ratio is shown as mean ± SEM. n = 3 independent samples per condition. (c) RVSP and RV/LV + S ratio in female (orange) and male (blue) WT and Mut rats were measured 24 days after the administration of the vehicle of MMC and shown as mean ± SEM. M and F stand male and female. n = 3–5 independent samples per condition. The two-way analysis of variance was performed. (d) lung weight, lung weight/body weight ratio, % body weight change, liver weight/body weight ratio, heart weight/body weight ratio, and kidney weight/body weight ratio of WT or Mut rats subjected to ISRIB (24-days treatment) are shown as mean ± SEM. n = 4–44 independent samples per group. (e) Heart and liver were harvested from WT rats 24 days after injecting vehicle (saline) or MMC (3 mg/kg), followed by H&E staining. Arrows indicate vessels. Scale bar=10 μm. (f) Immunoblot analysis of ATF4, cardiac troponin T (cTnT; loading control for the heart), and β-actin (loading control for liver) using heart and liver lysates harvested from WT and Mut rats 24 days after the treatment with the vehicle of MMC. n = 3 independent samples per group. (g) Heart and liver lysates from WT rats treated with vehicle (24d) or MMC (8d or 24d) were subjected to anti-puromycin immunoblot and anti-GAPDH blot (loading control). The relative levels of puromycin-labeled proteins normalized by GAPDH were quantitated and shown as mean ± SEM. n = 4 independent samples. (h) Pulmonary vasculature of WT and Mut rats treated with vehicle or MMC with or without ISRIB was cast by Microfil on day 24 (d24), and holistic images of a lobe are shown as black and white images. Scale bar= 0.5 cm. The number of branches and junctions (per cm2) of distal pulmonary vessels was counted and shown as mean ± SEM. n = 3 independent samples per group. Data are analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (b, c, d, g, h).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Examining the pulmonary vascular permeability in vivo, the amount of Rad51 and VE-Cad in the plasma of WT and Mut rats after MMC treatment, ATF4 recruitment to the PKR gene upon MMC treatment is diminished by ISRIB, and administration of C16 prevents reduction of the distal pulmonary vessel density mediated by MMC.

(a) The permeability of pulmonary vasculature was assessed by injecting Evans Blue dye in WT and Mut rats administered with vehicle or MMC with or without ISRIB or C16. The lung was harvested on day 24, and the image was taken after the lung became translucent. Scale bar=0.5 cm. (b) The relative intensity of EB staining of the lung in WT and Mut rats was quantitated by ImageJ and shown as mean ± SEM. n = 4 independent samples. (c) The amount of VE-Cad and Rad51 in the plasma of WT and Mut rats after MMC treatment (24d) were measured by ELISA and plotted as mean ± SEM. n = 9 independent samples per group. (d) ChIP assay was performed in PMVECs (1 × 106 cells) treated with vehicle, MMC, or MMC + ISRIB for four h with anti-ATF4 antibody, followed by PCR amplification of intron 1 of the PKR gene that contains three ATF4 consensus binding motifs. The result is shown as fold enrichment over the input sample as mean ± SEM. n = 6 independent samples. (e) The pulmonary vessels in WT rats treated with vehicle or MMC with or without C16 were cast with Microfil. After harvesting the lung, the image of the lobe was taken and presented after converting it to the black and white image. Distal pulmonary vessels in the area indicated by the orange box are magnified and shown below. Scale bar=0.5 cm. The number of branches and junctions (per cm2) of distal pulmonary vessels was counted and shown as mean ± SEM. n = 3 independent samples per group. Data are analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (b, c, d, e).

Extended Data Fig. 7 The pulmonary vascular phenotypes of two lines of BMPR2 mutant rats following MMC treatment are indistinguishable.

Representative H&E images of pulmonary vasculature exhibit similar phenotypes in E503fs (∆2/+) and Q495fs (∆26/+) rats 24 days after vehicle or MMC administration. Scale bar=10 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 8 PVOD phenotypes are evident as early as eight days after MMC administration, and delayed treatment with ISRIB attenuates ISR activation and vascular phenotypes.

(a) RVSP and RV/LV + S ratio in WT rats was measured eight days after the administration of vehicle or MMC and shown as mean ± SEM. n = 6 independent samples. (b) To examine the morphology of the pulmonary arteries (PAs) and veins (PVs), lungs were harvested from WT rats eight days after administering vehicle or MMC and subjected to H&E staining. An asterisk indicates the location of the vessels. Scale bar=10 mm. (c) WT rats administered with vehicle or MMC with or without 16-day (16d) or 8-day (8d) treatment with ISRIB were harvested on day 24, and the lung weight/body weight ratio was examined. n = 5–11 per condition. (d) The lung lysates of vehicle- or MMC-treated WT rats with or without 16-day or 8-day treatment with ISRIB were subjected to immunoblot of indicated proteins. β-actin is loading control. Quantitation of these blots is shown in Fig. 8e. n = 2–3 per condition. Data are analyzed by two-sided unpaired student’s t-test (a); one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (c).

Extended Data Fig. 9 ISRIB promotes the proliferation of vascular endothelial cells in the MMC-treated rats.

Scheme of delayed ISRIB treatment and EdU staining (16d and 8d treatment). WT rats were administered with vehicle or MMC on day 0 and treated with ISRIB starting on day 8 for 8 days (8d) or 16 days (16d). The EdU staining (green) was performed on day 8 (d8) or day 24 (d24). The lung section was co-stained with the endothelial marker CD31 (red) and Hoechst (blue for nuclei staining). The EdU and CD31 stain images were merged and shown in the “Merge” row. The intensity of the EdU signal in the CD31-positive vascular endothelial layer was quantitated by ImageJ and shown as mean + SEM. n = 7–14 independent samples per condition. White asterisks indicate pulmonary arteries. Scale bar= 10 μm. Data are analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Release of VE-Cad and Rad51 into the plasma in patients with PVOD.

Human patients with PVOD, IPAH, and PAH with BMPR2 mutations (PAH-BR2Mut) and non-PAH control individuals (n = 10 per group) were subjected to immunoblot with anti-VE-Cad, anti-Rad51, and anti-Transferrin (loading control) antibody. #1–10 indicate plasma samples from ten individuals. The relative amounts of VE-Cad and Rad51 normalized by transferrin are quantitated and shown as mean ± SEM. n = 10 independent samples per condition. Data are analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–8.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 7

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 8

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Unprocessed western blots.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prabhakar, A., Kumar, R., Wadhwa, M. et al. Reversal of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease phenotypes by inhibition of the integrated stress response. Nat Cardiovasc Res 3, 799–818 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44161-024-00495-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44161-024-00495-z