Abstract

Designing safe and reliable routes is the core of intelligent shipping. However, existing methods for industrial use are inadequate, primarily due to the lack of considering company preferences and ship maneuvering characteristics. To address these challenges, here we introduce a methodological framework that integrates maritime knowledge and autonomous maneuvering model. Based on historical maritime big data, the framework offers customized routes for companies with specific routing preferences. The autonomous maneuvering model then evaluates the safety and reliability of the routes by considering ship motion characteristics and ocean hydrodynamics. We validate its effectiveness on the world’s longest Green and Digital Shipping Corridor between Singapore and Rotterdam. Results demonstrate that our model can provide customized route design for companies and enhance safety for shipping. The framework could serve as a fundamental structure to build a fully digitalized platform for route customization and evaluation for global shipping, optimizing operational decision-making and safety assurance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

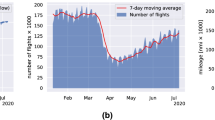

Maritime shipping accounts for over 80% of global trade volume, serving as a vital link in the global supply chain and a crucial component of the international economy1,2. In recent years, within the framework of Shipping 4.0, maritime transportation has been undergoing a digital technological revolution, with increasing attention being paid to intelligent shipping3. Among these advancements, route design plays a critical role in improving shipping efficiency and ensuring navigation safety. However, the globalization context poses great challenges to the current studies. On the one hand, traditional route design cannot meet the multifaceted demands of shipping companies for specific requirements, such as route preferences, navigation duration/speed, and ports of call. On the other hand, despite consistent efforts over the past decades, casualties and accidents in maritime transport remain prevalent, as highlighted in the annual reports on marine casualties by the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) from 20234. Specifically, 2560 reported incidents caused more than 800 cases with serious injuries and losses of human lives4. Consequently, ensuring safety at sea remains a priority in maritime transport research5,6,7. Moreover, due to the substantial size of container ships and the harsh environmental conditions, maneuvering these large vessels to complete predefined shipping tasks is challenging, posing great risks to the safety and reliability of maritime transport8.

The major advantages of intelligent shipping lies in utilizing techniques in automation science to minimize human error-induced accidents and enhance navigational safety9,10. To achieve intelligent shipping, one of the most essential components is safe and effective routing11. Conventionally, shipping routes are designated by fixed (or pre-determined) paths with optimal heuristic cost on a predefined grid, e.g., refs. 12,13,14. These grid-based methods are known to be ineffective due to the limitations in the searching directions and high computational cost15,16. Another commonly used method is to formulate an optimization model and design algorithms to iteratively obtain the optimal route. Some typical methods include meta-heuristic approaches, multi-objective optimization algorithms, and reinforcement learning, e.g., refs. 17,18,19. Moreover, the widespread use of the Automatic Identification System (AIS) opens up new opportunities to design voyage routes based on historical trajectory data. AIS-based methods use data mining techniques to formulate route libraries from historical data, which are then applied to practical route design, e.g., refs. 3,20,21.

However, although there has been substantial progress in route design, their practical application is constrained. This limitation arises from the lack of consideration for company preferences and coordination of ship maneuvering characteristics. On the one hand, previous studies typically focus on finding the shortest or least-cost paths, e.g., refs. 12,13,14,19,22, while cannot accommodate the specific needs of shipping companies in terms of route preferences, sailing channels, voyage duration, and ports of call, etc., to fulfill the business demands20. It should be noted that these preferences are hard to be incorporated into route planning methods through mathematical modeling. On the other hand, previous studies cannot ensure the navigation safety since the ship maneuvering characteristics are not considered, e.g., refs. 13,17,18,23,24. Some researchers have attempted to integrate maneuvering characteristics in route planning by conducting pre-simulated maneuvering testing25 and determining turning radius through speed profiles26. However, it should be noted that these studies lack adequate precision needed to accurately describe ship maneuverability under real navigational conditions. Due to the poor maneuvering capabilities of large container ships, crew members are unable to navigate waypoints that are not compatible with the maneuvering capabilities, e.g., turning behavior and acceleration bounds15,16. Furthermore, ships are subject to hydrodynamic responses from wind, waves, and currents during navigation, which increase the uncertainty and complexity of ship maneuvering27. This gap in research highlights the pressing need for approaches that meet both safety and operational efficiency standards. Regrettably, there is currently no related research that is able to design routes with coordination of actual ship maneuvering characteristics.

To incorporate company-specific preferences and ship maneuverability for modern shipping operations, the present study introduces a model-data dual driven framework that integrates maritime knowledge extracted from AIS data with an autonomous maneuvering model for smart shipping. The framework consists of three stages, as shown in Fig. 1.

-

In Stage 1, data preprocessing is carried out by conducting data cleaning, compression, and extraction to provide high-quality ship trajectories.

-

In Stage 2, maritime traffic knowledge is extracted from both global and local perspectives using an unsupervised hierarchical approach. Globally, this involves analyzing the overall distribution of trajectories, seasonal variations, and statistical characteristics. Locally, it includes examining vessel behavior, clustering trajectories, identifying movement patterns, and assessing traffic flow maps. Suitable routes are then extracted from the maritime traffic patterns based on the company’s specific port arrival requirements.

-

In Stage 3, an autonomous navigation model is established to test the reliability of the designed route. This model incorporates a ship nonlinear maneuvering model, guidance module, navigation module, and automatic control system. Autonomous maneuvering tests are then conducted, and the resulting maneuvering commands can be applied to ship autopilot or assist in manual operations during real-world navigation while reducing human errors and enhancing navigation safety.

In contrast to prior research, the model-data dual driven framework offers a more practical solution to maritime shipping by enhancing transportation safety and intelligence. The main contributions of our research are: (1) we introduce a knowledge-driven approach for shipping route design by integrating valuable information extracted from AIS data. This approach provides advantages over the previous works as it can facilitate customized route design for shipping companies with specific preferences including sailing channels, voyage duration, and ports of call. (2) We further provide an autonomous maneuvering digital model of a real ship to verify the shipping safety for the designed route by simulating the ship maneuvering. In contrast to previous studies, the model incorporates the motion characteristics of real ships, ocean hydrodynamics, and autonomous navigation system, providing enhanced safety assurances for maritime shipping. Results showcase that the approach demonstrates strong flexibility in customized route design for shipping companies with various preferences, as evidenced by the case study of the world’s longest digital corridor between Singapore and Rotterdam. We further demonstrate that the autonomous maneuvering model can effectively assess the ship maneuvering performance and collision risk before actual navigation. The generated control commands serve as a valuable reference for manual operations by the ship operators. This framework serves as a foundational step for future studies on developing more complex digital platforms for intelligent shipping. Our research can potentially provide inspiration for the industry on integrating both maritime big data and advanced automatic technology to facilitate route design, which is essential to enhance efficiency and safety assurance for maritime transport.

Results

The objective of this case study is to design two appropriate routes for China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO, the largest shipping company in China) to travel between Singapore and Rotterdam and evaluate the safety and reliability of the routes through maneuvering test. The dataset contains global AIS data for container ships covering the entire year of 2021. Readers can access the original dataset or the dataset that has been pre-processed by the authors through the repository link in “Data availability” statement.

Maritime knowledge mining between port Singapore and port Rotterdam

A maritime knowledge base that consists general information (distribution, season, voyage duration, and ship affiliations) and local information (movement patterns, traffic volume, and shipping behaviors) is formulated here, which will be the main support for route design.

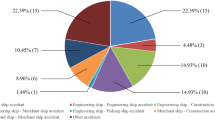

After the extraction of AIS data, a total of 520 trajectories are identified, shown in Fig. 2g. Notably, 516 trajectories passed through the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean region to traverse between Singapore and Rotterdam, with only 4 trajectories passing through the Cape of Good Hope in Africa, see Fig. 2g. For trajectories passing through Africa, we notice that they need to visit ports of call in the west side of Africa, including Lomé (Togo), Dakar (Senegal), Las Palmas (Spain), and Casablanca (Morocco). Moreover, statistical analysis on the ship flags shows that ships registered in Hong Kong (China) constitute the largest share at 18.1%, followed by those from Panama at 15.3%. Subsequently, ships from Denmark and the Netherlands account for 13.7% and 11.7%, respectively, see Fig. 2a. As for operation companies, we find that the majority of the operation companies on this route are Asian or European companies, see Fig. 2b. Specifically, COSCO emerges as the most active participant, accounting for 22.5% of ships. Maersk, a Danish shipping company, follows closely behind at 15.8%, while Nippon Yusen Kaisha from Japan ranks third at 7.7%. Hapag-Lloyd of Germany and Shoei Kisen Kaisha of Japan account for 5.7% and 5.5%, respectively. Two distinct peaks when COG and heading angle are around 100 degrees and 270 degrees are identified in Fig. 2c, e, which indicates ships traveling starting from Rotterdam and Singapore respectively. The majority of ships have a draught between 13 to 17 meters, indicating that the dataset primarily comprises large container ships, see Fig. 2d. Moreover, most ship trajectory points have speeds between 15 to 21 knots, indicating that the majority of points were sampled when ships were in normal sailing status, see Fig. 2f.

a, b show the distribution of flags and companies of all the trajectories traversing between Singapore and Rotterdam; c–f showcase the distribution of Course Over Ground (COG), draught, heading angle, and Speed Over Ground (SOG) of all the AIS messages; g denotes the visualized AIS messages between Singapore and Rotterdam; h, i showcase the distribution of voyage days and average voyage speed of all the trajectories.

Furthermore, we analyze the trajectory patterns based on the departure season. The results show that there are more routes scheduled during the Summer and Autumn seasons, numbering 136 and 139 respectively, and 129 routes in Spring, while the fewest routes (116 trajectories) occur during the winter. As for distribution on the voyage duration, we observe small variance across the four seasons, ranging from 26.6 days in Spring to 26.0 days in Autumn. Analysis of the box plots reveals that the median voyage duration for all seasons is lower than the mean value, indicating a negatively skewed distribution where the majority of voyages fall below the mean value, see Fig. 2h. Regarding the average speed, the seasonal differences are also small, with the fastest average speed occurring in Spring at 16.5 knots and the slowest in Winter at 15.9 knots. However, we note a contrasting pattern with voyage duration. The median voyage speed consistently exceeds the mean value, suggesting a positively skewed distribution where the majority of voyages occur above the mean value, see Fig. 2i. We attribute this phenomenon to longer voyages during Spring, during which ships predominantly maintain high-speed sailing, resulting in higher average speeds. Conversely, in Winter, where voyages are shorter, ships spend less time sailing at high speeds, leading to lower average speeds.

To extract the movement patterns, shipping behaviors, and traffic flow of routes between Singapore and Rotterdam, the trajectories are segmented into three local trajectory sets for knowledge mining, see Fig. 3a–c. There are two reasons for choosing these three segments. First, they exhibit distinct differences pertaining to movement patterns in the trajectory sets. Second, we observe that the ships only make port calls along these segments. Here we present the analysis of the first trajectory set shown in Fig. 3a. More results on other local trajectory sets can be found in Supplementary Note 2 (Section 2).

For trajectories starting from Singapore, ships operated by COSCO, Maersk, and NYK show similar movement patterns, where most of the ships head directly towards the Suez Canal, with only a few stops at the Colombo port, see the blue lines in Fig. 4a, b. However, ships from Hapag-Lloyd show different patterns. These ships stop at various ports in this region, including Mumbai (India), Mundra (India), and Dubai (United Arab Emirates). For trajectories departing from Rotterdam, a large number of ships from COSCO and NYK sail directly towards Sri Lanka, with a small number stop at Dubai, see red lines in Fig. 4a, b. However, the behavior of ships from Maersk changes notably in this segment, with many ships stop in Salalah (Oman) and Dubai. Similarly, there is an obvious difference in the behavior of ships operated by Hapag-Lloyd, with no ship making stops in this area. Typical movement patterns for these companies are summarized in Table 1. Furthermore, the major traffic nodes identified in trajectory set 1 contains a total of 11 nodes, each representing geographical location information, see Fig. 3d, e and Table 2. We notice that Node 9 has the highest traffic volume of 158. This suggests that most trajectories pass directly through Node 9 into the Suez Canal, while the rest trajectories enter the Suez Canal via Node 8 and Node 10. Moreover, the busiest port in trajectory set 1 is Salalah port (Node 8), with the highest traffic volume of 22, followed by Dubai (19), Dwarka (16), and Mumbai (5).

a Shipping routes for the major companies, where the blue lines denote the routes starting from Singapore while the red lines are those starting from Rotterdam. From left to right, these are COSCO (China Ocean Shipping Company), Maersk, NYK (Nippon Yusen Kaisha), and Hapag-Lloyd; b the extracted movement patterns of these companies from the actual trajectories. Blue lines represent trajectories departing from Singapore, while red lines represent trajectories departing from Rotterdam.

Figure 5 shows the clustering results of the trajectory segment around Indian Ocean. The results shows that the differences between shipping behaviors mainly lie in different port calls or turning points, see Fig. 5a. In the direction from Singapore to Rotterdam (first row), five distinct trajectory sets are identified. Each set is characterized by variations in the chosen turning points around Socotra Island. In the direction from Rotterdam to Singapore (second row), differences between trajectories arise not only from the turning points but also from variations in ports of call. For instance, vessels in Cluster 1 make a stop in Dubai, while vessels in Cluster 2 stop in Salalah. The proposed method also showcases better performance for trajectory clustering compared to HDBSCAN28, DBTCAN29, and IDBSCAN30, see Fig. 5b. We observe that DBTCAN and IDBSCAN tend to classify a large number of trajectories as noise, whereas HDBSCAN struggles to differentiate among the trajectory clusters effectively. The summarized details on the shipping behaviors can be found in Table 3. More results on other local trajectory sets can be found in Supplementary Note 2 (Section 2).

a Clustering results of the shipping behaviors, where the first row shows the clusters of ships departing from Singapore, and the second row shows the clusters of ships departing from Rotterdam; b clustering comparison between different methods, where HDBSCAN, DBSCAN and DBTCAN stands for “Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise”, “Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise”, and “Density-Based Trajectory Clustering of Applications with Noise”, respectively.

Knowledge-based route design between Singapore and Rotterdam

The objective of this case study is to design two customized routes for COSCO to travel between Singapore and Rotterdam and evaluate the safety of the routes through maneuvering test. Specific requirements posed by COSCO company are shown by Table 4. When considering route 1, observations from COSCO’s movement patterns indicate that their routes in the Mediterranean region only include stops at Athens and Valencia. We find that there are no routes that fulfill the docking requirements, necessitating the exploration of new routes from the knowledge base. When considering route 2, trajectories that meet the requirements can be directly found in the movement patterns provided in Supplementary Note 2 (Section 2). The particulars of the designed routes are presented in Table 5 and Fig. 6b, c.

Maneuvering test of the designed routes

Here we present the maneuvering test results for both routes. The maneuvering test is conducted on a Mariner class ship31 with a length of 160.93 meters and a width of 20.17 meters. The particulars of the ship and parameter settings on the navigation system are shown in Supplementary Note 2 (Section 3). It is worth noting that the case study presented in this paper serves to demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed system architecture, and it is not limited to the parameters outlined above. In practical applications, the system described in this paper can be adapted to other ships based on the technical parameters provided by the shipping companies. The voyage for Route No. 1 is divided into three segments to more accurately simulate the shipping process. The first segment begins from Singapore and docks at the Port of Colombo, see Fig. 7a. The second segment starts from the Port of Colombo and docks at the Port of Malta, see Fig. 7b. The third segment departs from the Port of Malta and reaches the final destination at the Port of Rotterdam, see Fig. 7c. The voyage for Route No. 2 is divided into two segments. The first segment begins from port of Rotterdam to port of Athens (see Fig. 8a), while the second segment starts from port of Athens to port of Singapore (see Fig. 8b).

a Ship trajectory of segment 1; (a1) Zoom-in of ship leaving port of Singapore; (a2) Zoom-in of ship entering port of Colombo; (a3) Maneuvering commands and tracking logs of the ship; b Ship trajectory of segment 2; (b1) Zoom-in of ship navigating through the Little Bitter Lake; (b2) Zoom-in of ship entering port of Malta; (b3) Maneuvering commands and tracking logs of the ship; c Ship trajectory of segment 3; (c1) Zoom-in of ship navigating Strait of Messina; (c2) Zoom-in of ship entering port of Rotterdam; (c3) Maneuvering commands and tracking logs of the ship.

a Ship trajectory of segment 1; (a1) Zoom-in of ship turning at Cherbourg; (a2) Zoom-in of ship navigating through the Straits of Kythira; (a3) Maneuvering commands and tracking logs of the ship; b Ship trajectory of segment 2; (b1) Zoom-in of ship navigating through the Little Bitter Lake; (b2) Zoom-in of ship entering port of Singapore; (b3) Maneuvering commands and tracking logs of the ship.

For the voyage between Singapore and Colombo, the ship successfully completes this segment of the voyage, see Fig. 7a. However, we observe large tracking errors during the ship’s turning maneuvers, see Fig. 7a1–a2. This is primarily due to the poor maneuverability of large container ships, which leads to more challenging to control the ship. Furthermore, the dense distribution of turning waypoints leads to frequent and large changes in the course command signal, especially in the beginning and end of the voyage, see the course changes in Fig. 7a3. For the voyage between Colombo to Malta, the ships safely navigate through the narrow waterways such as the Little Bitter Lake within the Suez Canal, see Fig. 7b1–b2. The commands generated by the model ensure the safe and reliable completion of this part of the voyage. Furthermore, there are fluctuations in the course command between the 9-th and 10-th days of the voyage (see Fig. 7b3), which indicates that the ship is entering the Suez Canal, where the dense distribution of turning waypoints is required because of the narrow channel in the river. Compared to results of previous segments, there are more fluctuations in the course command and rudder command in this part of voyage, see Fig. 7c3. This is because the ship passes through multiple ports along this route, which contains more turning waypoints. Overall, the commands generated by our model enable the ship to navigate this segment safely and reliably, indicating that these commands can be effectively used for ship navigation in real-world scenarios.

Similar results can be seen in Fig. 8. Figure 8a shows the trajectory and command results for the ship’s journey from the Port of Rotterdam to the Port of Athens, demonstrating that the vessel successfully follows this segment of the route. We also observe noticeable tracking errors at certain turning points, such as the turn in the waters above Cherbourg, as highlighted in Fig. 8a1. Figure 8b presents the vessel’s route from the Port of Athens to the Port of Singapore. This route is more challenging, as it passes through the narrow Suez Canal. As shown in Fig. 8b1–b2, the vessel successfully navigates through the Suez Canal and Little Bitter Lake, safely completing these segments. In Fig. 8a3, b3, we observe that various signals are synchronized. When the vessel makes a turn, the course command, rudder command, and speed signals change simultaneously. Additionally, the rudder angle is strictly controlled within the maximum threshold of 40 degrees.

Discussion

Designing safe and reliable routes is of paramount significance for maritime transportation. In this paper, our aim is to present the prospective combination of maritime knowledge and autonomous maneuvering model to facilitate intelligent shipping, providing insights for shipping route design and safety assurance for maritime transport.

Our results demonstrate the framework’s potential to inspire knowledge-based route designs in the shipping industry, offering valuable insights for future global maritime operations. Notably, our maritime knowledge extraction framework efficiently retrieves both general characteristics and detailed insights into movement patterns and shipping behaviors from AIS data. The results indicate that shipping behaviors along the same route can vary due to factors such as season, company preferences, flag state, and vessel size. Furthermore, based on the extracted maritime knowledge, shipping route is successfully designed by considering the diverse needs of shipping companies, including departure seasons, channels, voyage duration, and port of calls. These results highlight the potential of our study to provide professionally customized route designs for shipping companies. In the future, the framework could serve as an initial step toward establishing a global maritime transportation knowledge base, facilitating customized route design between ports worldwide for any institute.

The results on the autonomous maneuvering test also provide promising inspiration to enhance safety for the maritime transportation industry. The autonomous maneuvering model collectively considers the nonlinear hydrodynamic effects and physical characteristics of ship motions. We find that the designed route can be carefully evaluated pertaining to the ship maneuvering performance and collision risk using the autonomous maneuvering model. The maneuvering commands generated during the test can be applied to ship autopilots or assist in manual operations during real-world navigation. These results highlight the effectiveness of our route testing framework in enabling pre-voyage safety assessments, providing valuable insights for route decision-makers. The framework could serve as a fundamental structure for developing more sophisticated digital platforms for navigation safety testing.

In the future, our work could be extended in several key directions to further enhance its impact on the maritime industry. First, the development of a comprehensive global maritime knowledge base for route customization, incorporating diverse factors such as seasonal variations, vessel characteristics, and regional regulations, could serve as a valuable resource for both shipping companies and governments. Also, the quantitative indicators for route assessment could be further studied. Our current model needs thorough theoretical research and a deeper understanding of how companies assess route satisfaction. Additionally, the autonomous maneuvering framework could be further expanded using physical engine technique like Mixed Reality (MR), which provides precise semi-physical models for ships, weather dynamics, sea states, and traffic conditions. By integrating this framework with a fully digitalized platform, shipping companies could simulate and evaluate routes under various conditions, optimizing both safety and efficiency. Ultimately, these advancements would not only improve operational decision-making but also contribute to the development of intelligent and autonomous maritime transportation systems.

Conclusion

In this study, we explored the integration of maritime knowledge extraction and autonomous maneuvering models to advance intelligent route planning and enhance safety in maritime transportation. By analyzing AIS data, we developed a framework capable of extracting critical insights into shipping behaviors and operational patterns, which can be used to tailor routes based on company preferences and environmental conditions. The autonomous maneuvering model further supports pre-voyage safety assessments, allowing for comprehensive evaluation of routes in terms of maneuverability and collision risk. Based on our findings, the following key conclusions can be drawn:

-

The maritime knowledge extraction framework in this study demonstrates strong capability to extract valuable insights from AIS data, capturing both general movement patterns and specific shipping behaviors. These insights form a foundation for intelligent route design in the maritime industry, offering data-driven guidance for more efficient global operations.

-

The framework enables route customization according to company preferences, considering factors such as departure seasons, port calls, and voyage duration. This approach highlights the potential for creating a global maritime knowledge base that facilitates tailored route design to meet the diverse needs of shipping companies.

-

The autonomous maneuvering model enhances route safety by evaluating ship maneuvering performance at pre-voyage stage, with practical applications for autopilot systems or manual navigation. Future advancements, such as integrating MR techniques, could further optimize route safety and efficiency, advancing the development of intelligent maritime transportation systems.

Methods

In the following paragraph, we present the general functional modules of the methodology, including the data preprocessing, unsupervised hierarchical approach for maritime knowledge extraction, and autonomous maneuvering model. The implementation details can be found in Supplementary Note 1 (Sections 1–3).

Data preprocessing

The data preprocessing methods in this paper covers data cleaning, trajectory extraction and splitting strategies, as well as spatial-temporal trajectory compression. Following the methods in refs. 29,32, the cleaning of AIS data involves the removal of erroneous data and messages representing stationary states, e.g., abnormal latitude and longitude values, speed, and course angle. Then, following studies in ref. 33, we divide the trajectories into segments when the time interval between two consecutive points exceeds a threshold value. This threshold is determined by calculating the average variations in sampling time intervals for all trajectories. Finally, we can extract the all the trajectories starting from the area of Singapore or Rotterdam.

After extracting all the trajectories needed, we start the process of data compression. Spatial trajectories often consist of a large number of points, especially when sampled frequently. This can lead to inefficiencies in storage, processing, and visualization. However, the traditional Douglas-Peucker34 (DP) algorithm may inadvertently discard important temporal information such as velocity changes and time intervals between points, which are crucial for understanding the dynamics and behavior of ships. We introduce the Spatial-Temporal Compression35 (STC) method to add temporal correlations between spatial points. The criterion of this approach assesses distances between pairs of temporally synchronized positions, one from the original trajectory and the other from the trajectory projection split by time intervals. This fundamental shift showcases the spatiotemporal nature of a moving ship trajectory, providing a more accurate representation of its characteristics. One of the advantages of STC is its ability to adaptively filter trajectory points. It retains more points in dense parts of the trajectory to preserve the shape, while in sparse parts it shows similar results compared to DP, an example of the comparison can be found in Supplementary Note 1 (Section 1). The actual application results of STC are illustrated in Supplementary Note 2 (Section 2).

Unsupervised hierarchical approach for maritime knowledge mining

The knowledge extraction method in this article consists of trajectory similarity measurements, clustering algorithm, and traffic knowledge extraction. Similarity measurements enable the identification of trajectories that exhibit similar movement patterns, behaviors, or characteristics. In this research, we apply the Soft Dynamic Time Warping36 (soft DTW) for similarity measurement. By introducing a differentiable penalty function that penalizes deviations from the optimal alignment path, soft DTW provides a smoother and more flexible alignment between sequences37.

In order to appropriately cluster the trajectory, we introduce an Improved Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (IHDBSCAN) algorithm. First, we determine the optimal value of eps using a k-distance curve and the Kneedle function38, leveraging guidance from related studies on dimensionality and neighbor distances. With eps established, we then determine min_cluster_size by iterating over a range of values and analyzing the number of clusters generated by HDBSCAN39. If the cluster count stabilizes over consecutive iterations, the maximum value within this stable range is chosen as min_cluster_size. This approach improves parameter selection efficiency, with termination of iterations when a single cluster dominates. For more details on the description of IHDBSCAN, please refer to Supplementary Note 1 (Section 1.2). The comparative clustering results of IHDBSCAN and other state-of-the-arts using our datasets can be found in Supplementary Note 2 (Section 2), which shows a clear advantage on the clustering performance.

Traffic flow analysis in maritime transportation involves studying the movement of ships within waterways, ports, and maritime corridors40. In this paper, we extend the method framework proposed in ref. 41 and introduce an algorithm called characteristic-point based traffic knowledge extraction (CPTKE). The first step is to extract the characteristic points from the trajectory data by setting thresholds on sampling time intervals and heading angle changes. During ship operations, heading angles may experience fluctuations due to emergency situations or environmental disturbances. This can lead to some points being incorrectly identified as characteristic points. Hence, two auxiliary variables \({d}_{\min }\) and \({d}_{\max }\) are introduced for correction. If the distance between two points is less than \({d}_{\min }\), we consider these two points as indistinguishable and retain only the first point. \({d}_{\max }\) represents the maximum distance between two characteristic points. We can adjust these distances to determine the precision of the extraction process, see Fig. 9a–d. Then, the traffic nodes can be identified by clustering the characteristic points using IHDBSCAN, see Fig. 9e, f. An example is shown in Fig. 9g–i. Once all the nodes have been found by CPTKE, we can use the trajectory data to compute the traffic flow. First, the traffic volume within each cluster is determined by counting the CPs in each cluster. Next, the method examines interactions between pairs of clusters by checking if any trajectories pass through both clusters. When a trajectory intersects two clusters, it indicates a flow between them, and this interaction is recorded. Details on the CPTKE can be found in Supplementary Note 1 (Section 1).

a Original trajectory; b dmax = 2 CRS, dmin = 1 CRS, course change = 45 deg, time interval = 12 h; c dmax = 8 CRS, dmin = 1 CRS, course change = 45 deg, time interval = 12 h; d dmax = 20 CRS, dmin = 1 CRS, course change = 45 deg, time interval = 12 h; the ports of call along the trajectory has been successfully identified in (d); e the CPs of 133 ships docked near the port of Athens; f the characteristic points of 178 ships started from ports around Singapore; g original trajectory points; h characteristic points; i nodes extracted from (h). CRS means the unit under Geographic Coordinate Systems (WGS84), and CP stands for characteristic points.

Route design

Route design is conducted through maritime knowledge that summarizes both general characteristics and detailed insights of the movement patterns and shipping behaviors from AIS data. In contrast to traditional research, the method can provide customized routes for shipping companies based on historical trajectories and vessel information to meet these requirements. We first examine the historical trajectories of the company to ascertain if any meet the specified requirements. If suitable trajectories are identified, they are directly considered as design routes. In cases where historical trajectories do not meet the requirements, we employ the following approach to find the trajectories: Based on the results of general information, we identify potential routes meeting criteria such as seasonal considerations, sailing directions, voyage days, and company preferences. Subsequently, utilizing the movement patterns and shipping behaviors, we refine the selection to find trajectories satisfying the specific port call requirements.

Autonomous maneuvering model

To evaluate if the route is safe and reliable for real-world navigation, we design an autonomous maneuvering model to build a semi-physical model for a real ship. This model consists of four modules: nonlinear maneuvering model, navigation module, guidance module, and control module. Nonlinear maneuvering module simulates the kinematics and dynamics of the ship during the motion, considering factors such as rigid body kinetics, hydrodynamics, propulsion, hydrodynamics of the ocean and environmental disturbances. The navigation module estimates the information of ship position, velocity, and course during the navigation. It integrates measurement data from Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), inertial measurement units (IMUs), and gyros. Guidance module refers to the continuous computation of the desired position, velocity, and acceleration signals. Finally, the control module receives the desired signals from guidance module and calculates control actions to steer the ship. It adjusts the control inputs using actuators such as rudders and thrusters to ensure precise navigation and adherence to the waypoints. Detailed formulation can be found in Supplementary Note 1 (Section 2).

Data availability

Original AIS data are available in the Github repository42. The map data used in Figs. 4a and 5 are made with Natural Earth. Sources of the maps in Figs. 2g, 3, 4b, 6b, c, 7–9 are provided by Esri, DeLorme, HERE, TomTom, Intermap, increment P Corp, GEBCO, USGS, FAO, NPS, NRCAN, GeoBase, IGN, Kadaster NL, Ordnance Survey, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), swisstopo, MapmyIndia, and the GIS user community.

Code availability

All the source codes for reproducing the results of this article can be fully accessed by the Github link42.

References

Luo, Z. et al. Shipping-related pollution decreased but mortality increased in Chinese port cities. Nat. Cities 1, 295–304 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Health and climate impacts of ocean-going vessels in East Asia. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1037–1041 (2016).

Li, H. & Yang, Z. Incorporation of AIS data-based machine learning into unsupervised route planning for maritime autonomous surface ships. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 176, 103171 (2023).

European Maritime Safety Agency. EMSA facts and figures 2023. https://www.emsa.europa.eu/publications/item/5176-emsa-facts-figures-2023.html (2024).

Zhao, Y., Ma, Y., Zhu, G., Hu, S. & Yan, X. Stable training via elastic adaptive deep reinforcement learning for autonomous navigation of intelligent vehicles. Commun. Eng. 3, 37 (2024).

Volkov, D. L. et al. Florida Current transport observations reveal four decades of steady state. Nat. Commun. 15, 7780 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Emissions and health impacts from global shipping embodied in US–China bilateral trade. Nat. Sustain. 2, 1027–1033 (2019).

Wang, X.-T. et al. Trade-linked shipping CO2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 945–951 (2021).

Feng, S. et al. Dense reinforcement learning for safety validation of autonomous vehicles. Nature 615, 620–627 (2023).

Cao, Z. et al. Continuous improvement of self-driving cars using dynamic confidence-aware reinforcement learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 145–158 (2023).

Gu, Y. & Wallace, S. W. Operational benefits of autonomous vessels in logistics—a case of autonomous water-taxis in Bergen. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 154, 102456 (2021).

Kim, S. et al. Development of a ship route decision-making algorithm based on a real number grid method. Appl. Ocean Res. 101, 102230 (2020).

Charalambopoulos, N., Xidias, E. & Nearchou, A. Efficient ship weather routing using probabilistic roadmaps. Ocean Eng. 273, 114031 (2023).

Zvyagina, T. & Zvyagin, P. A model of multi-objective route optimization for a vessel in drifting ice. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 218, 108147 (2022).

Song, R., Liu, Y. & Bucknall, R. Smoothed A* algorithm for practical unmanned surface vehicle path planning. Appl. Ocean Res. 83, 9–20 (2019).

Zhao, L., Bai, Y. & Paik, J. K. Achieving optimal-dynamic path planning for unmanned surface vehicles: a rational multi-objective approach and a sensory-vector re-planner. Ocean Eng. 286, 115433 (2023).

Ma, D., Zhou, S., Han, Y., Ma, W. & Huang, H. Multi-objective ship weather routing method based on the improved NSGA-III algorithm. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 38, 100570 (2024).

Szlapczynski, R., Szlapczynska, J. & Vettor, R. Ship weather routing featuring w-MOEA/D and uncertainty handling. Appl. Soft Comput. 138, 110142 (2023).

Ma, W. et al. Ship route planning based on intelligent mapping swarm optimization. Comput. Ind. Eng. 176, 108920 (2023).

Cai, J., Chen, G., Lützen, M. & Rytter, N. G. M. A practical AIS-based route library for voyage planning at the pre-fixture stage. Ocean Eng. 236, 109478 (2021).

Kim, J. S., Park, H. J., Shin, W., Park, D. & Han, S. W. WAY: estimation of vessel destination in worldwide AIS trajectory. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 59, 5961–5977 (2023).

Liu, C., Ma, Y., Cao, C. & Yan, X. Ship route planning in the pirate area via hybrid probabilistic roadmap algorithm within the context of the Maritime Silk Road. Ocean Coast. Manag. 238, 106585 (2023).

Gao, Y. & Sun, Z. Tramp ship routing and speed optimization with tidal berth time windows. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 178, 103268 (2023).

Lu, S., Cheng, X., Liu, J., Li, S. & Yasukawa, H. Maneuvering modeling of a twin-propeller twin-rudder inland container vessel based on integrated CFD and empirical methods. Appl. Ocean Res. 126, 103261 (2022).

Wang, L., Zhang, Z., Zhu, Q. & Ma, S. Ship route planning based on double-cycling genetic algorithm considering ship maneuverability constraint. IEEE Access 8, 190746–190759 (2020).

Akdağ, M., Pedersen, T. A., Fossen, T. I. & Johansen, T. A. A decision support system for autonomous ship trajectory planning. Ocean Eng. 292, 116562 (2024).

Johansen, T. et al. Development and testing of a risk-based control system for autonomous ships. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 234, 109195 (2023).

Murray, B. & Perera, L. P. An AIS-based deep learning framework for regional ship behavior prediction. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 215, 107819 (2021).

Yang, J., Liu, Y., Ma, L. & Ji, C. Maritime traffic flow clustering analysis by density based trajectory clustering with noise. Ocean Eng. 249, 111001 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Spatio-temporal vessel trajectory clustering based on data mapping and density. IEEE Access 6, 58939–58954 (2018).

Perez, T., Smogeli, O., Fossen, T. & Sorensen, A. J. An overview of the marine systems simulator (MSS): a simulink toolbox for marine control systems. Model. Identif. Control 27, 259–275 (2006).

Mao, S. et al. An automatic identification system (AIS) database for maritime trajectory prediction and data mining. in Proceedings of ELM-2016 241–257 (Springer, 2018).

Graser, A. Movingpandas: efficient structures for movement data in python. GIForum 1, 54–68 (2019).

Douglas, D. H. & Peucker, T. K. Algorithms for the reduction of the number of points required to represent a digitized line or its caricature. Cartographica Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Geovisualization 10, 112–122 (1973).

Meratnia, N. & de By, R. A. Spatiotemporal compression techniques for moving point objects. in Advances in Database Technology-EDBT 2004: 9th International Conference on Extending Database Technology, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, March 14-18 765–782 (Springer, 2004).

Cuturi, M. & Blondel, M. Soft-dtw: a differentiable loss function for time-series. in International Conference on Machine Learning 894–903 (PMLR, 2017).

Nath, A. G., Sharma, A., Udmale, S. S. & Singh, S. K. An early classification approach for improving structural rotor fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 70, 1–13 (2021).

Sahu, P., Singh, B. K. & Nirala, N. Optimized k-nearest neighbors for classification of prosthetic hand movements using electromyography signal. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 133, 108390 (2024).

McInnes, L. et al. hdbscan: Hierarchical density based clustering. J. Open Source Softw. 2, 205 (2017).

Liang, M. et al. Fine-grained vessel traffic flow prediction with a spatio-temporal multigraph convolutional network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 23694–23707 (2022).

Adrienko, N. & Adrienko, G. Spatial generalization and aggregation of massive movement data. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 17, 205–219 (2010).

Zhao, L. Maritime knowledge extraction and ship maneuvering test. https://github.com/LiangZhao13/Maritime-knowledge-extraction-and-ship-maneuvering-test.git (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by Singapore MOE AcRF Tier 1 Grant (Grant number: RG75/23), Singapore Energy Consortium (SEC) Core Project (Grant number: SEC-Core2024-34), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 72101046), and China Scholarship Council (Grant number: 202306320340).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z., R.Y., and L.Z. conceived the conceptual ideas and project design. M.Z. provided the original dataset. L.Z. implemented the methods, developed the algorithm code, conducted the experiments, and analyzed the results. L.Z., M.Z., and R.Y. wrote the original manuscript draft. R.Y., Y.B., and M.Z. supervised the work, provided the research environment with funding support and revised the manuscript. L.L., Y.B., and M.X. reviewed the initial manuscript and provided improvement suggestions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Jialun Liu and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Pengfei Liu and Anastasiia Vasylchenkova.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, L., Xu, M., Liu, L. et al. Intelligent shipping: integrating autonomous maneuvering and maritime knowledge in the Singapore-Rotterdam Corridor. Commun Eng 4, 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00346-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00346-0