Abstract

Carbon neutrality targets rely on the flexible, fast-response characteristics of batteries, and the high energy density and clean byproduct of hydrogen. However, the potential role of battery and hydrogen circular economies in the carbon neutrality transition remains uncertain. In this study, a future clean power grid and its impact on the lifecycle carbon footprint of battery and hydrogen circular economies have been predicted. A database of the lifecycle carbon footprint is set up from raw material to recycling. Additionally, a carbon intensity map of lifecycle stages of batteries and hydrogen storage across climate regions in China is provided. The proposed zero-energy paradigm is economically feasible with the obtained levelized net present value ranging from 0.0119 US$ per kWhe (Kunming) to 0.0574 US$ per kWhe (Guangzhou). The findings aim to clarify the role of battery and hydrogen circular economies in the carbon neutrality transition and provide a comprehensive analysis of hydrogen and battery technologies for policy decision-makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

1.5 °C and 2 °C global temperature rise targets in Paris Agreement require the continuous exploitation of clean and sustainable energy resources and international collaborations with the promotion of advanced energy paradigms adaptive to different climate zones globally. Smart and sustainable cities pay more focus than ever before on heat exposure1, heat mitigation2, climate change adaption3 and energy resilience under climate risks4. Energy savings5, renewable energy6,7 and waste management8 are main streams for sustainable development. Renewable energy sources with intermittence and instability, and energy demands with stochasticity impose great challenges on high renewable penetration and utilisation in high efficiency9. Given the high gravimetric density and clean byproduct water of hydrogen and fast response of battery, electrochemical battery and hydrogen10 have been deployed as energy storage mediums for both short-term (such as daily) storage11 and long-term seasonal storage12. Electrification transition from diesel to renewable-battery can be widely deployed in transportations13,14, power supply15 and buildings16 with tech-economic feasibility17,18. Cross-scale macro-level (like integrated renewable-battery-hydrogen-building-grid models) and micro-level models (like PEMFC combined heat and power cogeneration model)19 are critical for accurate energy flexibility evaluation20, dynamic technical performance prediction, large-scale and economic performance analysis21.

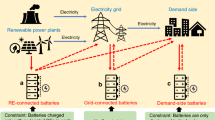

Furthermore, large-scale battery22 and manganese-hydrogen storages23 can be applied for fast power response24,25, high renewable penetration26, and grid power stabilisation23. Depending on different geographical locations of integrated battery storages, renewable-connected, grid-connected, and demand-side battery deployment strategies are included, while the design principle, operation control and techno-economic analysis are quite different. Unlike centralised battery storages only considering power supply characteristic with uniformity factors for capacity sizing27, the demand-side battery needs to simultaneously consider both power supply and energy demand characteristics. The provincial comparison in China indicates that, renewable-connected battery strategies are suitable in areas with abundant renewable resources, while the demand-side battery strategies are suitable in areas with limited renewables22.

Economic performance of battery and hydrogen-driven reliable and low-carbon energy systems has also attracted widespread interests worldwide. The comparison on different hydrogen production pathways in US indicates that the hybrid electricity-based production is much cheaper (2.02–2.88 US$ kg−1) than the fossil-based pathway (2.73–5.94 US$ kg−1)28. Compared to stationary fuel cells, the heavy-duty vehicle fuel cells can reduce levelized cost of energy (LCOE) by 13–20%, together with high renewable energy penetration (>80%) in local power grids29. The cost-effective battery storage in distributed residential solar customers can incentive the self-financed PV installation behaviours30. The energy return on investment is applied to assess the economic effectiveness on different energy transition scenarios with variations on renewable share, natural gas and oil depletions31. Global electrification with cross-continental trade can reduce the annual system cost of electricity by 5-52% in 2050, with the improvement in electricity demand coverage from 12% to 100%32. Economic analysis on renewable-to-hydrogen electrolysis process33 validates its commercial competitiveness with cost at 3.23 EUR kg−1 in both Germany and Texas, and it will be reduced to 2.50 EUR kg−1 in industrial-scale supply in the near future. Similarly, hydrogen production costs range from 2.6 US$ to 12.3 US$ kg−1, and there were already 20 states less than 4.0 US$ kg−1 with competitiveness over the fuel cost of gasoline vehicles34. Blue hydrogen is competitive when natural gas prices are below 15 EUR per MWh35.

Carbon emissions of battery and hydrogen have been studied, considering time-matching12. The rapid battery cost decline36 can accelerate the traffic electrification, and it is estimated that 40% of global traffic electrification can reduce CO2 emissions by 14% for US-based vessels. Green hydrogen based on solar-wind electrolysis plays critical roles in decarbonising coal chemical sector with net cost reductions37. An integrated life cycle assessment and geometallurgical approach can contribute to sustainable extraction of battery materials and promote the future low-carbon economy38. Recycled lithium-ion batteries can provide secondary source of raw materials for new battery production39, while challenges are proposed on challenges of various battery recycling technologies40. Grid Decarbonization requires storages in design and operations41. Combined policies are necessary for carbon mitigation targets, like electrification of light-duty vehicles and fuel consumption efficiency improvement of conventional vehicles42.

In academia, there is no existing research on carbon footprint quantification on battery and hydrogen circular economy, especially considering future clean power grid upgrade and complex operational stages (like power interactions between e-mobility and buildings, power-to-hydrogen and combined heat and power interactions between fuel cell electric vehicles and buildings, cascade electric vehicle (EV) battery reuse and retired battery recycling). Secondly, participation willingness of stakeholders and investors (e.g., renewable investors, owners of buildings, EVs, utility grid company, etc) in future battery and hydrogen circular economy has not been analysed. Furthermore, techno-economic-environmental superiority and inferiority of battery and hydrogen circular economy are not clear, hindering the future low-carbon transition on battery and hydrogen.

In this work, a generic method is proposed and applied to quantify the lifecycle carbon footprint of both battery and hydrogen circular economy with clear database throughout raw material mining, manufacturing, operation, reuse and recycling stages. Impact of power grid upgrade on lifecycle carbon footprint has been analysed and compared between battery and hydrogen circular economy. Secondly, the participation willingness of stakeholders and investors has been analysed from perspectives of levelized cost of energy storage (LCOES) and levelized net present value. Thirdly, lifecycle techno-economic-environmental comparison between battery and hydrogen circular economy was conducted. A carbon intensity map was provided with various life cycle analysis (LCA) stages across different climate regions in China, to help decision-makers initiate frontier policies on battery and hydrogen for the future low-carbon transition. Generally, traditional battery and hydrogen life cycle process is mainly divided into four phases: raw materials mining, manufacturing, operation and recycling phase, as shown in Fig. 1. During the raw material mining and manufacturing phase, battery and hydrogen-related components (like electrolyser, fuel cell, hydrogen tank, etc.) are produced in vehicles. The operation phase is complicated with multiple functions of vehicles, like daily travelling, energy carriers for power sharing, back-up power source for emergency, etc. Furthermore, cascade utilization technology on battery and hydrogen-related components can extend their service lifetime, improve material utilisation efficiency, and promote the sustainable development. Last but not the least, the retired components (e.g., battery with relative capacity less than 60%) will be recycled for material circular economy. Note that, the carbon footprint and lifecycle carbon intensity is rather difficult to be accurately quantified, especially in both operation, reuse and recycling phases.

Results

Regarding battery and hydrogen-driven integrative low-carbon systems, this study conducts frontier research on lifecycle techno-economic-environmental performance analysis. Lifecycle carbon intensity, net present value and levelized cost of energy storage have been analysed. It should be admitted that results are drawn without any prior explanation of how these are really drawn and what was asked to the stakeholders. The research results can provide frontier guidelines for clean power grid upgrade, low-carbon transition and economic investment.

Energy structures and carbon emission factor for clean power grid upgrade

The 2050 or 2060 carbon neutrality targets and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of United Nations necessitate immediate actions globally. Clean power grid upgrade with energy structure adjustment plays essential roles in widespread areas, like industry, building and transportation. This section is to predict both energy structures and carbon emission factors of future clean power grid based on historical database, to pave path for decarbonisation analysis on battery and hydrogen energy systems.

Figure 2 demonstrates the energy structures and carbon emission factors of traditional coal-fired power grid, current power grid with mixed energy sources and future clean power grid, respectively. The traditional grid refers to the power grid fully supported by coal-fired power generation43; the current grid is based on the energy structure of the grid in 202043; and the future grid is based on the energy structure in 2060 as predicted in ref. 44. The traditional coal-fired power grid with 100% of coals shows the highest carbon emission factor (CEF). The transition from traditional coal-fired power grid to the current power grid with mixed energy sources can greatly reduce the CEF of power grid. For instance, in Beijing, the CEF decreases from 1002.9 g CO2,e kWhe−1 (100% coals, subscript e refers to electrical energy) to 861.0 g CO2,e kWhe−1 (89.12% thermal power, 6.62% wind, 3.66% solar, and 0.6% hydropower), and then further decreases to 158.3 g CO2,e kWhe−1 (57.9% solar, 22.54% wind, 7.92% hydropower and 11.64% thermal power).43 Furthermore, in the future clean power grid, the dominated energy sources are geographically dependent. Specifically, the dominated renewable energy sources are geographically dependent, i.e., solar energy (57.90%) in Beijing, wind (61.20%) in Hong Kong, solar and wind (89.95%) in Shanghai, nuclear in Guangzhou (58.79%), hydropower in Kunming (54.08%).

Impact of CEF of power grid on lifecycle carbon footprint

Figure 3 demonstrates the impact of power grid transformation from traditional to future clean power grid on battery carbon intensity. Clearly, with the transition from traditional coal-fired grid to current power grid with mixture of various energy resources, lifecycle battery carbon intensity can be slightly reduced, and the decreasing magnitude is geographically location-dependent. Furthermore, the transition towards the future clean power grid in 2060 will greatly reduce the lifecycle battery carbon intensity. For instance, in Guangzhou, the lifecycle battery carbon intensity decreases from 1064.63 g kWhe−1 (traditional power grid) to 580.02 g kWhe−1 (current power grid, by 45.5%) and then to 158.67 g kWhe−1 (future power grid in 2060, by 85.1%). The underlying mechanism is due to the decrease of the electricity grid carbon emission factor (i.e., how much carbon emission will be released when generation per kWh electricity) from 865.2 to 426.3 g CO2,e kWhe−1 and then to 44.7 g CO2,e kWhe−1. Specifically, the lifecycle carbon intensity of battery (i.e., how much carbon emission will be released throughout the whole lifecycle of battery) mainly includes both embodied carbon and operational carbon emissions45, and the decrease in CEF from traditional power grid to future power grid can effectively reduce carbon emissions from grid to EV charging process.

Regarding the hydrogen-based system, similar tendency can also be noticed but with more obvious decreasing magnitude. For instance, in Guangzhou, the lifecycle hydrogen carbon intensity decreases from 2463.19 g CO2,e kWhe−1 (traditional power grid) to 1250.43 g CO2,e kWhe−1 (current power grid, by 49.2%) and then to 196.00 g CO2,e kWhe−1 (future power grid in 2060, by 92.0%). The comparison between battery-based and hydrogen-based system indicates that, even with the update in future grid, the battery system still shows generally higher potentials than the hydrogen system (with only electricity generation) in carbon neutrality.

Lifecycle carbon intensity, net present value and levelized cost of energy storage for battery and hydrogen circular economy

Lifecycle carbon intensity of net zero-energy battery and net zero-energy hydrogen circular economy is studied. Two scenarios are studied, as demonstrated in Fig. 4.

-

(1)

Scenario I (Fig. 4a): this scenario combines the Vehicle-to-Building/Building-to-Vehicle (V2B/B2V) scenario with the cascade EV battery reuse for energy storage in buildings, when EV battery retires with the relative capacity dropped to 80% of their initial capacity.

-

(2)

Scenario II (FCEV-to-building & building-to-FCEV energy interaction system in Fig. 4b): In this scenario, the fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) will supply both power and heat to the building energy system and be partially refuelled by hydrogen generated by surplus renewable energy.

a Battery circular economy with Vehicle-to-Building (V2B)/Building-to-Vehicle (B2V) and cascade Electric Vehicle (EV) battery reuse; b Hydrogen circular economy with Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle (FCEV)-to-building & building-to-FCEV energy interaction. (Note: small-scale batteries in EVs are used for buildings.).

In this section, both net present value (NPV) and battery carbon intensity are analysed to illustrate the economic feasibility and zero-carbon pathway, respectively. Note that the NPVs of other scenarios are calculated based on the traditional scenario (Fig. 4a).

Lifecycle battery carbon intensity for different stages is summarised in Supplementary Table 1. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, the carbon intensity in grid accounts for the highest proportion at around 50% in all studied cities in different climates, and the meteorological parameters and climate information are in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 1. This is due to the high CEF of the current power grid, as shown in Fig. 2. Proportion of total electricity charged into batteries from renewables and power grid, and carbon intensity in renewables and power grid are listed in Supplementary Tables and 3. The parameter information of renewable equipment is given in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 2.

In order to study the participation willingness of stakeholders and investors, the economic performance of the integrated system is conducted, from perspectives of LCOES and levelized net present value. As shown in Supplementary Table 6, to invest the integrated system with maintenance and operation costs, the LCOES ranges from 0.0617 US$ per kWhe (Kunming) to 0.0645 US$ per kWhe (Shanghai). To run the integrated system, the obtained levelized net present value ranges from 0.0119 US$ per kWhe (Kunming) to 0.0574 US$ per kWhe (Guangzhou). This indicates the high profitability by investing and running the battery-driven multi-energy system with the V2B/B2V and cascade EV battery reuse. The grid prices in different climate cities in China are given in Supplementary Tables 7–18.

In the other hand, lifecycle carbon intensity of grey hydrogen indicates that, in the grey hydrogen-driven energy system, the carbon intensity is mainly from the grey hydrogen production at around 98% (as shown in Supplementary Table 19). Considering the mixed grey and green hydrogen in real applications, a net-zero energy paradigm with both renewable-driven electrolysis and pipeline delivered grey hydrogen is formulated. As listed in Supplementary Table 20, Kunming shows the lowest carbon intensity at 246.28 g CO2,e kWhe,h−1, while Hong Kong shows the highest carbon intensity at 1105. 22 g CO2,e kWhe,h−1 for combined heat/power generation (Note: ‘kWhe,h’ refers to per kWh of electricity and thermal energy for hydrogen-based cogeneration). The former is due to the lowest carbon emission factor of the grid at 152.7 g CO2,e kWhe−1 in Kunming (as shown in Fig. 2), and the latter is due to the lowest proportion of green hydrogen at 8.35% in Hong Kong (as shown in Supplementary Table 20).

The levelized NPV of the H2-driven energy system is shown in Supplementary Table 21. As shown in Supplementary Table 21, the green H2-driven energy system is economically feasible in Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Beijing (levelized NPV at 0.0378, 0.0818 and 0.0542 US$ kWhe,h−1, respectively), while it is economically infeasible in Kunming, Shanghai and Xi’an (levelized NPV at −0.0823, −0.0255 and −0.0389 US$ kWhe,h−1, respectively). Meanwhile, the grey H2-driven energy system is economically feasible only in Guangzhou. In terms of the mixed Green and Grey H2-driven energy system in the net-zero energy paradigm, it is economically feasible only in Guangzhou (the levelized NPV at 0.0258 US$ kWh−1, respectively), while it is economically infeasible in Beijing, Kunming, Shanghai, Xi’an and Hong Kong (the levelized NPV at −0.0153, −0.0569, −0.0586, −0.0324 and −0.1105 US$ kWhe,h−1, respectively).

Discussion on energy structure and the levelized Net Present Value (NPV) in different regions indicates that the transition from traditional coal power grids to mixed and renewable energy sources greatly impacts both carbon emissions and economic feasibility. The system based on EV energy sharing and cascade battery utilization demonstrates a favourable net present value across various cities, indicating a high return on investment. In contrast, the economic feasibility of hydrogen energy systems is influenced by multiple factors, including the energy structure, energy demand, and renewable generation. Considering different energy structures in different cities, current research findings indicate that hydrogen energy systems are economically viable in Guangzhou, while they face economic challenges in other cities such as Beijing, Kunming, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Xi’an.

The comparison on battery and hydrogen circular economy was conducted in carbon intensity and levelized net present value under the net-zero energy paradigm (the detailed system design is in the Supplementary Tables 22 and 23, Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 and Supplementary Notes 3–4). Techno-economic-environmental feasibility has been analysed, i.e., NPV for economic performance, carbon intensity for both technical and environmental performances and carbon emissions for environmental performance. As demonstrated in Fig. 5, the carbon intensity of hydrogen circular economy is generally higher than that in the battery circular economy, and the economic performance of hydrogen circular economy is lower than that in the battery circular economy. Specifically, the LCA carbon intensity of battery circular economy is 278.37 (Xi’an), 193.84 (Shanghai), 138.64 (Kunming), 182.80 (Hong Kong), 195.08 (Guangzhou) and 252.38 g CO2,e kWhe−1 (Beijing), which is much lower than that in the hydrogen circular economy at 1632.24 (Xi’an), 1165.79 (Shanghai), 395.34 (Kunming), 1671.88 (Hong Kong), 944.78 (Guangzhou) and 1712.58 g CO2,e kWhe−1 (Beijing) for solely power generation and 984.91 (Xi’an), 728.81 (Shanghai), 246.28 (Kunming), 1105.22 (Hong Kong), 591.76 (Guangzhou) and 1021.04 g CO2,e kWhe,h−1 (Beijing) for combined heat/power cogeneration, respectively. In terms of the levelized net present value, the battery circular economy is more competitive than that in the hydrogen circular economy. For instance, the levelized NPV of battery circular economy is 0.0220 (Xi’an), 0.0364 (Shanghai), 0.0119 (Kunming), 0.0281 (Beijing), 0.0275 (Hong Kong) and 0.0574 $ kWhe−1 (Guangzhou), which is much higher than that in the hydrogen circular economy at −0.0537 (Xi’an), −0.0938 (Shanghai), −0.0914 (Kunming), −0.0256 (Beijing), −0.1672 (Hong Kong) and 0.0412 $ kWhe−1 (Guangzhou) for sole power generation and −0.0324 (Xi’an), −0.0586 (Shanghai), −0.0569 (Kunming), −0.0153 (Beijing), −0.1105 (Hong Kong) and 0.0258 $ kWhe,h−1 (Guangzhou) for heat/power cogeneration. In other words, due to the low energy conversion efficiency and high initial cost of hydrogen circular economy, the battery circular economy is more economically and environmentally competitive, and the economic-environmental feasibility of hydrogen circular economy is questionable.

(Note: A net-zero energy paradigm is applied. Scenario with V2B/B2V and cascade EV battery reuse in the battery circular economy; Scenario with FCEV-to-building & building-to-FCEV energy interaction in the hydrogen circular economy. CB, CH, NB and NH refer to carbon intensity of the battery system, carbon intensity of the hydrogen system, net present value (NPV) of the battery system, and NPV of the hydrogen system, respectively.).

To explore the constitution of carbon intensity for battery and hydrogen circular economy, and compare carbon emissions when using only renewable energy electricity, the carbon intensity map of various LCA stages is provided across different climate regions in China. As demonstrated in Fig. 6b, the LCA carbon emission of the green battery energy system is mainly from the operational stage, followed by the embodied carbon emission in battery raw materials, production and recycling processes. In terms of the green hydrogen-driven energy system in Fig. 6c, as the operational carbon emission is zero (renewable energy supply, clean water electrolysis and byproduct water in the fuel cell), the carbon emission mainly comes from embodied carbon in associated components (i.e., renewable systems, electrolyzer, compressor, H2 tank, fuel cells with their real-time depreciations). With respect to Fig. 6d, combined heat and power generation for the building energy system evidently improved the energy efficiency of hydrogen system. Furthermore, unlike the grey hydrogen-driven energy system, in the green hydrogen-driven energy system, the carbon emission is mainly from the integrated renewable systems, followed by the compressor and H2 tank. The electrolysis process shows the lowest carbon intensity.

a Location of cities in different climate regions in the China map. b The carbon intensity of various LCA stages within the green battery circular economy in the cities. c The carbon intensity of various LCA stages within the green hydrogen circular economy for solely power generation in the cities. d The carbon intensity of various LCA stages within the green hydrogen circular economy for combined heat/power generation in the cities. (Note: Both the green battery circular economy and the green hydrogen use green renewable energy from building distributed photovoltaic and wind turbine generation; the energy unit ‘kWh’ with subscripts ‘e’ and ‘h’ represent per kWh of electricity and heat energy, respectively.).

The comparison between the green battery circular economy and the green hydrogen circular economy indicates that, green hydrogen circular economy shows a much higher carbon intensity than that of the green battery circular economy for electricity supply. For instance, carbon intensity of green hydrogen circular economy is 271.40 g kWhe−1 (Xi’an), 174.92 g kWhe−1 (Shanghai), 123.51 g kWhe−1 (Hong Kong), 265.52 g kWhe−1 (Guangzhou), 250.04 g kWhe−1 (Kunming) and 164.18 g kWhe−1 (Beijing), which is much higher than that in the battery circular economy at 127.90 g kWhe−1 (Xi’an), 100.64 g kWhe−1 (Shanghai), 84.18 g kWhe−1 (Hong Kong), 127.81 g kWhe−1 (Guangzhou), 121.50 g kWhe−1 (Kunming) and 99.38 g kWhe−1 (Beijing). However, with combined heat and power generation, the carbon intensity of green hydrogen circular economy decreases and the comparison between green hydrogen/battery circular economy becomes case-dependent. Specifically, the carbon intensities of green hydrogen circular economy for combined heat/power supply are 81.65 and 97.88 g kWhe,h−1 in Hong Kong and Beijing, slightly lower than that of green battery circular economy at 84.18 and 99.38 g kWhe−1 in Hong Kong and Beijing, respectively. This is because of the relatively lower embodied carbon of green hydrogen circular economy than green battery circular economy, together with the relatively low carbon emission factor of renewable energy in Hong Kong, caused by high renewable energy endowment (as shown in Supplementary Table 24). In Guangzhou, Kunming, Shanghai and Xi’an, even with combined heat/power supply, the carbon emissions of hydrogen energy systems (166.31 g kWhe,h−1 in Guangzhou, 155.76 g kWhe,h−1 in Kunming, 109.35 g kWhe,h−1 in Shanghai, 163.77 g kWhe,h−1 in Xi’an) are still higher than those of battery systems. This is because the carbon emissions of hydrogen circular economy during operation (127.83 g kWhe,h−1 in Guangzhou, 105.81 g kWhe,h−1 in Kunming, 74.20 g kWhe,h−1 in Shanghai, 130.09 g kWhe,h−1 in Xi’an) are higher than those of battery systems (75.60 g kWhe−1 in Guangzhou, 69.42 g kWhe−1 in Kunming, 48.71 g kWhe−1 in Shanghai, 74.75 g kWhe−1 in Xi’an), due to the relatively lower energy efficiency of power-to-gas-to-heat/power process in hydrogen energy systems.

Comparison with other studies

In order to ensure the reliability and thoroughness, main results of this study are compared with published research. The carbon emission and levelized cost of energy storage (LCOES) are compared in the battery circular economy with other studies in Supplementary Table 25. The comparison shows that the economic and environmental results of this study are close to those of other studies. For example, when the battery power source is from both the grid and renewable electricity, the results of other studies are between 263 and 330 g CO2 kWhe[−1 46, while the results of this study fall within this range at 139–278 g CO2 kWhe−1. When the battery power source is only from renewable electricity, the results of other studies are between 35 and 118 g CO2 kWhe−1 46,47, while the results of this study are between 84 and 128 g CO2 kWhe−1, highlighting the feasibility and reliability of research results from this study. In terms of LCOES, the results of other studies are between 0.088 and 0.359 US$ kWhe−147,48, while the results of this paper are between 0.062 and 0.065 US$ kWhe−1. The lower LCOES in this study is mainly due to the adoption of lower battery prices (125 US$ kWh−1)49 in China and the implementation of battery reuse strategies.

Similarly, the hydrogen energy systems have been compared with already published studies. Supplementary Table 26 compares the levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) and levelized carbon emission of hydrogen (LCEOH) in the integrated hydrogen circular economy of this study with results from other research. The calculated LCOH and LCEOH, as intermediate variables in this study, align with the conclusions from other studies. For instance, the LCEOH of electrolysed hydrogen with grid power in this study and ref. 43 are 9.6–52.0 and 27.4–44.3 kg CO2,e kg H2−1, respectively. In addition, the LCEOH of electrolysed hydrogen with renewable energy in this study is 2.2–5.3 kg CO2,e kg H2−1 with combined PV and wind power, which is within a reasonable error margin compared to that of ref. 43 at 2.1–6.8 kg CO2,e kg H2−1 with PV power and 0.6–3.0 kg CO2,e kg H2−1 with wind power. Furthermore, the LCOH of grid-power-electrolysed hydrogen across China are 3.8–7.9 and 3.3–7.0 US$ kg H2−1 from this study and China hydrogen alliance50, respectively, with a slight error at 12.9–15.2%. These comparison results demonstrate the validity of the data and model used in this study. It should be noted that the levelized cost and carbon emission of heat/electricity discharged to the building energy system are not compared due to the lack of comparable research.

Discussion

In this study, motivator or driver roles of battery and hydrogen circular economy in carbon neutrality in China have been dialectically and systematically analysed. A power grid model is developed and applied to predict the future power grid upgrade from the traditional coal-fired to the mixed clean energy-based, with respect to energy structure constitutions and carbon emission factors. Energy paradigm transformations towards distribution, interaction and sustainability has been explored, with power interactions between e-mobility and buildings, power-to-hydrogen and combined heat and power interactions between fuel cell electric vehicles and buildings, cascade electric vehicle (EV) battery reuse and retired battery recycling. A generic method is proposed and applied to quantify the lifecycle carbon footprint of both battery and hydrogen circular economy with clear database throughout raw material mining, manufacturing, operation, reuse and recycling stages. Impact of power grid upgrade on lifecycle carbon footprint has been analysed and compared between battery and hydrogen circular economy. Techno-economic-environmental comparison between battery and hydrogen circular economy is provided in carbon intensity and levelized net present value, and then generalized and scalable in five climate regions with different solar-wind energy resources in China. There are some findings from research results:

-

1.

Based on the historical database in power grid upgrade from the traditional coal-fired to the current power grid with mixed energy sources, the developed power grid model can predict the future clean power grid upgrade with quantifiable energy structure constitutions and carbon emission factors (CEF). Meanwhile, the dominated renewable energy sources are geographically dependent.

-

2.

The transition from traditional coal-fired grid to future clean power grid with mixture of various energy resources leads to the decrease in both lifecycle carbon intensity of battery and hydrogen energy system, and more obvious decrease can be noticed in the hydrogen energy system (e.g., in Guangzhou, the lifecycle hydrogen carbon intensity decreases from 2463.19 g CO2,e kWhe−1 (traditional power grid) to 1250.43 g CO2,e kWhe−1 (current power grid, by 49.2%) and then to 196.00 g CO2,e kWhe−1 (future power grid in 2060, by 92.0%). Meanwhile, the lifecycle battery carbon intensity decreases from 1064.63 g kWhe−1 (traditional power grid) to 580.02 g kWhe−1 (current power grid, by 45.5%) and then to 158.67 g kWhe−1 (future power grid in 2060, by 85.1%).

-

3.

The participation willingness of stakeholders and investors has been analysed from perspectives of LCOES and levelized net present value. The proposed zero-energy paradigm with the V2B/B2V and cascade EV battery reuse is economically feasible across different climates in China with the obtained levelized net present value ranging from 0.0119 US$ per kWhe (Kunming) to 0.0574 US$ per kWhe (Guangzhou). In terms of the mixed Green and Grey H2-driven energy system in the net-zero energy paradigm, it is economically feasible only in Guangzhou (levelized net present value at 0.0258 US$ kWhe,h−1, respectively).

-

4.

Techno-economic-environmental comparison between battery and hydrogen integrative energy systems indicates that, the carbon intensity and economic performance of battery-driven integrative energy system is generally better than that in the hydrogen-driven integrative energy system (e.g., in Guangzhou, the lifecycle carbon intensity and NPV are 591.76 g CO2,e kWhe,h−1 and 0.0258 US$ kWhe,h−1 for the hydrogen-driven cogeneration system and 195.08 g kWhe−1 and 0.0574 US$ kWhe−1 for the battery-driven integrative energy system), respectively.

-

5.

Carbon intensity map of various lifecycle stages across different climate regions in China indicates that lifecycle carbon emission of green battery circular economy is mainly from the operational stage. In the green hydrogen-driven energy system, the carbon emission is mainly from the integrated renewable systems, followed by the compressor and H2 tank, while the electrolysis process shows the lowest carbon intensity. Furthermore, the comparison between battery and the green hydrogen circular economy indicates that the green hydrogen circular economy for sole power generation shows much higher carbon intensity than that of the battery circular economy. However, with combined heat and power supply, the green hydrogen circular economy demonstrates lower carbon intensity than the green battery circular economy in Beijing and Hong Kong, due to the low embodied carbon emissions of green hydrogen circular economy and the relative higher renewable generation potential in these cities.

The conclusions of this paper clarify the motivator or driver roles of battery and hydrogen circular economy in carbon neutrality in China. The developed power grid model can be applied to analyse the upgrade from the traditional coal-fired to the future clean power grid, with respect to energy structure constitutions and carbon emission factors. Techno-economic-environmental comparison between battery and hydrogen circular economy can help decision-makers to initiate frontier policies with comprehensive considerations on carbon intensity and levelized net present value. Research methods and models can be generalized and scalable in different climates in China.

Another important aspect is how the conclusions of this paper can guide stakeholders and engage investors. The successful implementation of these advanced energy systems relies heavily on the active participation and support of various stakeholders, including renewable energy providers, building owners, electric vehicle (EV) owners, utility grid companies, and policymakers. Understanding their perspectives and willingness to participate is crucial for the practical deployment of these technologies.

The economic feasibility of the proposed systems has been explored from the perspective of levelized net present value (NPV) and levelized cost of energy storage (LCOES). Case studies from different cities in China have been presented to illustrate the potential benefits and challenges of attracting stakeholders and investors. These case studies provide insights into the practical implementation of the proposed systems. In addition, potential scenarios for future developments and the role of stakeholders in driving the transition to low-carbon energy systems have been discussed.

However, there are still limitations in this paper. Firstly, impact of tax reduction exemption incentives on investment behaviours of stakeholders has not been analysed, like production tax credit (PTC) and investment tax credit (ITC). Secondly, only the reuse and recycling of battery energy systems have been analysed, while the domestic reuse and recycling of hydrogen energy systems have not been studied. Therefore, future work will focus on (1) impact of tax reduction exemption incentives on investment behaviours of stakeholders; (2) the domestic reuse and recycling of hydrogen energy systems for decarbonisation.

Methods

Overview

This paper originally develops several calculation models as shown in Fig. 7.

Cross-scale macro-level models in this study refer to models’ integration of different units from the macro scale (like integrated renewable-battery-hydrogen-building-grid models), and the micro-level models in this study refer to detailed physical model of specific components, like proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) combined heat and power cogeneration model, battery degradation model, fuel cell degradation model and so on. Note that both cross-scale macro-level models and micro-level models in this paper are constructed by TRNSYS 18. The descriptions of all models established in this study are as follows:

-

1.

Battery degradation model: simulate the dynamic degradation of the battery under multi-directional Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) interactions (Fig. 7c).

-

2.

Fuel cell degradation model: simulate the dynamic degradation of the battery under multi-directional V2X interactions (Fig. 7d).

-

3.

EV-based building-to-building energy sharing model: simulate the energy sharing and interaction among renewable systems, EVs and buildings within the district community (Fig. 7a).

-

4.

FCEV-based building-to-building energy sharing model: simulate the energy sharing and interaction among renewable systems, FCEVs and buildings within the district community (Fig. 7b).

-

5.

Battery carbon intensity calculation model: calculate the environmental impact of batteries over the lifecycle (Fig. 7e).

-

6.

Hydrogen equipment carbon intensity calculation model: calculate the environmental impact of hydrogen equipment over the lifecycle (Fig. 7e).

-

7.

NPV and LCOES calculation models: calculate the system economic performance and levelized cost of energy storage over the lifecycle (Fig. 7e).

Battery degradation model

Battery degradation is affected by many factors, such as number of cycles, charge and discharge rates, depth of discharge and operating temperature. The degradation model in this study is based on the relationship between the relative capacity (RC) of the battery, the number of cycles (CycleNum) and the depth of discharge (DoD), as shown in Eq. (1). Note that the main challenge of battery degradation model lies in the limited testing database under the discontinuous DoD (DoD at 1, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.3, 0.2 and 0.151), while the continuous DoD happens in reality and modelling processes.

The coefficients k1, k2, k3 and k4 are obtained by fitting original data from ref. 52 and are listed in Supplementary Table 27.

Based on the previously model development approach by the author of this study53, the dynamic RC under battery operation is obtained by the following steps. As more details on modelling has been described in ref. 53, here we briefly introduce the main steps to avoid the repetition:

The first step is to obtain the change in the number of cycles according to fractional state of charge (FSOC), which is shown in Eq. (2).

where \({E}_{t\to t+{{{\rm{\tau }}}}}\) refers to the energy received and released by the battery within a time step. Capt refers to the dynamic capacity of the battery. FSOCt+τ refers to the FSOC of the next time step, and FSOCt refers to the FSOC of the current time step. DoD1or2 indicates the two DoDs that appear in Supplementary Table 27 closest to the current DoD.

The second step is to calculate the number of cycles in the next time step (including DoD1 and DoD2 curves), shown in Eq. (3)

where CumCycleNumt refers to the number of cycles of the current time step.

In the third step, the RC under DoD1 and DoD2 are calculated according to the Eq. (1), and obtain RCDoD1,t+τ and RCDoD2,t+τ.

In the fourth step, the actual RC is calculated via linear interpolation by the Eq. (4).

Fuel cell degradation model

The degradation of fuel cells impacts the efficiency of both electricity and heat generation. In this study, a dynamic model54,55 that describes the degradation rate of fuel cells during operation, as well as the variation of thermal and electrical efficiency with decaying is presented.

where Rdeg and kp represent the degradation ratio and the acceleration coefficient. n1 and n2 denote the number of load-changing cycles and start-stop cycles, respectively. t1 and t2 are the duration of idling and high power out, respectively. P1 − P4 are the weight values of each working condition, as shown in Supplementary Table 28 in detail.

The electricity power of FCEV (Pele) after degradation (Rdeg) is defined as:

The total heat power of the FCEV after degradation (Pheat) is defined as56:

where the \(I\) and Vcell denote the current and voltage of the single cell, and the Ncell is the number of cells within the fuel cell stack. Rdeg represents the degradation ratio of the fuel cell and the Etn is the thermoneutral voltage of hydrogen at the standard condition.

E-mobility based building-to-building energy sharing model

The model57 develops a network of energy interaction between different types of buildings via electric vehicles. The model includes three types of buildings, a high-rise office building, a high-rise hotel, and 30 residential buildings. Thermophysical properties of these buildings are designed similar following the Chinese building design code58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68 in different cities. In order to achieve low-carbon buildings, building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs), solar thermal collectors and on-site wind turbines are designed for each building. The EV can be charged by the building’s on-site renewable energy to enhance renewable energy self-consumption or penetration, and be discharged to cover demand shortage. grid-to-vehicle (G2V) represents the mandatory charging of EVs. In addition, when the relative capacity of EV batteries drops to 80%, it will be reused as static batteries to store renewable electricity for the building energy system, and recycled after the relative capacity drops to 60%.

FCEV-based building-to-building energy sharing model

In the reference case, FCEVs are only responsible for transportation, with no energy interaction with buildings. By comparison, within the hydrogen circular economy framework, FCEV facilitate temporal and spatial energy sharing and interaction among three types of buildings through V2B&B2V processes. Moreover, surplus renewable energy within buildings is utilized for hydrogen production, and the produced hydrogen is allocated to 60 FCEVs owned by the building occupants. In addition, when the pressure level in hydrogen tank (HTK) reaches 0.75, the surplus hydrogen will be available for sale to the FCEVs from outside. Conversely, FCEVs provide power and heat to buildings during peak periods in the grid.

The daily operational schedule for FCEVs is illustrated in Note S5. It is assumed that there are 60 FCEV owners within the building cluster who exhibit strong motivation and willingness to participate in V2B&B2V processes. Among them, FCEVs 1–48 are private cars, while FCEVs 49–60 are shuttle buses.

Battery carbon intensity calculation model

To quantify the carbon emissions of batteries throughout the life cycle, the carbon intensity (CI) has been proposed as shown by Eq. (8):

where Edis refers to the total energy discharged by the battery, CEtot refers to the total carbon emission that calculated by Eq. (9):

The specific calculations of CEraw, CEmanu, CErecyc, CEope, and CERE are as follows:

In raw materials phase, CEraw is calculated by Eq. (10):

where the subscripts ini, repl, and tend, respectively, represent the initial batteries, the new batteries replaced during operation, and the batteries at the end of the simulation. CEFraw refers to the carbon emission factor of the raw materials phase at 51 kg CO2,e per kWh69.

In manufacturing phase, CEmanu is calculated by Eq. (11):

where the subscripts ini, repl, and tend, respectively, represent the initial batteries, the new batteries replaced during operation, and the batteries at the end of the simulation. CEFraw refers to the carbon emission factor of the raw materials phase at 34 kg CO2,e per kWh.

During the operation phase, decarbonisation amount by storing excess renewable energy in the battery is calculated by Eq. (12):

where the Pgrid,ch,i(t) refers to the grid energy charged to the battery, and PRE,ch,i(t) refers to the renewable energy charged to the battery. The CEFgrid is calculated by Eq. (13):

where Ei represents the proportion of different energy types, as shown in Fig. 2. CEFi represents the carbon emission factors of different energy types as shown in Supplementary Table 2943. The Ei in China in 2060 is projected based on the contributions of five key power generation technologies: thermal power, hydroelectric power, nuclear power, wind power, and solar power44. The proportion of each technology within the energy structure for each province is determined by the share of these technologies as recorded in ref. 43. This approach demonstrates the provincial difference of the energy structure transformation in China over four decades, facilitating a deeper understanding of the regional shifts and technological advancements driving the country’s transition towards a low-carbon energy system.

In the recycling phase, the carbon emission factor of recycling (CEFrecyc) is 69.8 kg CO2,e kWh−1 for Li-ion batteries69. The carbon emission (CErecyc) at the recycling phase can be expressed by Eq. (14):

where Caprecyc,i refer to the recycled battery capacity of the ith battery.

The embodied carbon of renewable energy equipment can be defined as the carbon emission generated during manufacturing, transportation, operation, maintenance and recycling of renewable energy equipment.

For PVs, the embodied carbon emission per kWp is shown in Eq. (15)70:

For wind turbine, the embodied carbon per kW can be calculated by Eq. (16):

where ECEWT, unit refers to the embodied carbon emission of the wind turbine with a unit of kg CO2,e kW−1, and PWT, rated refers to the rated power of the wind turbine. Equation (16) is obtained by fitting the data from refs. 71,72,73,74,75,76,77. Note that, the embodied carbon of wind turbines decreases with the increase of rated power.

Therefore, the carbon emission from building integrated renewable systems, CERE, is calculated in Eq. (17):

where ERE,ch and ERE refer to the renewable energy charged to the battery and the renewable energy generated by PVs and wind turbines. PPV is the peak power of the PV panel at the standard condition. ECEPV,unit refers to the embodied carbon emission of PVs per kWp. ECEWT,unit refers to the embodied carbon emission of the wind turbine per kW, and PWT,rated refers to the rated power of the wind turbine.

Hydrogen equipment carbon intensity calculation model

To quantify the carbon emissions of hydrogen equipment throughout the life cycle, the carbon intensity of hydrogen circular economy (CIHydrogen), green hydrogen circular economy (CIGreen hydrogen) and grey hydrogen circular economy (CIGrey hydrogen) has been proposed as shown by Eqs. (18)–(20):

where \({E}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}{{\rm{,dis}}}}\) refers to the total electricity and heat energy discharged by the fuel cell during V2B process. \({M}_{{{\rm{Green}}},{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2},{{\rm{Cons}}}}\), \({M}_{{{\rm{Grey}}},{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2},{{\rm{Cons}}}}\) and \({M}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}}\) are the mass of self-generated green hydrogen, imported grey hydrogen from hydrogen station with electrolyzer powered by grid electricity, and the mass of total consumed hydrogen. CETot and CEGreen refer to the carbon emission of integrated hydrogen a green hydrogen system that calculated by Eqs. (21)–(23):

The specific calculations of CEFC, CEEC, \({{CE}}_{{{\rm{Grey}}}{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}}\), CERE, and CEHTK&Compression are as follows:

For fuel cells, CEFC is calculated by Eq. (24):

where the CEFC Material mining&manufacture, CEFC Recycle represent the carbon emissions of fuel cell during material mining and manufacture stage, and recycle stage, at 35.4 kg CO2,e kW−1 78 and 11.9 kg CO2,e kW−1 79, respectively.

For electrolyzer cells, CEEC is calculated by Eq. (25):

where the CEEC Material mining&manufacture, CEEC Recycle represent the carbon emissions of electrolyzer during material mining and manufacture stage, and recycle stage, at 28.0 kg CO2,e per kW80 and 21.8 kg CO2,e per kW80, respectively.

In the Hydrogen storage and compression stage, CEHTK&Compression is calculated by Eq. (26):

where the CEHTK Material mining&manufacture refers to the carbon emissions of material mining and manufacture for hydrogen tank (HTK) (Note that the end of life of hydrogen tank is considered to be directly disposal due to lack of recycling data). PCompression is the power of hydrogen compressor during H2 refuelling. The CEFRE is the carbon emission factor of the RE electricity as shown in Fig. 2.

For the process of RE-based H2 generation, the carbon emission of green hydrogen generation based on RE energy can be expressed by Eq. (27):

where PElectro refer to the input power of electrolyzer.

The carbon emission from building integrated renewable systems, \({CE}F\)RE, is calculated in Eq. (28):

where ERE refer to the renewable energy charged to the building and electrolysers. PPV is the peak power of the PV panel at the standard condition. ECEPV,unit refers to the embodied carbon emission of PVs per kWp. ECEWT,unit,i refers to the embodied carbon emission of the wind turbine per kW, and Prated,i refers to the rated power of the wind turbine.

The levelized carbon emissions of hydrogen (LCEOH) based on on-site renewable energy is calculated in Eq. (29):

The carbon emission of grey hydrogen in the hydrogen circular economy (\({{CE}}_{{\mbox{Grey}}{{\mbox{H}}}_{2}}\)) is calculated with Eq. (30):

where CEEC station and CEHTK station denote the carbon emissions of electrolyzer and hydrogen storage tank in hydrogen station. PElectro station is the dynamic electrolysis power in the hydrogen station. ECompression is the energy for refuelling per kilogram hydrogen into fuel cell electric vehicle (at 1.47 kWh kg H2−1 81).

NPV and LCOES calculation model

NPV is an absolute measure of the difference between the present value of cash inflows and the present value of cash outflows over a specific period of time. The NPV is adopted to assist to make decisions on whether the investment activity is economically feasible or not. The levelized costs of energy storage (LCOES) refers to the average cost of providing each kilowatt-hour of electricity storage and discharge services over the entire lifecycle of an energy storage system, serving as a comprehensive method for evaluating the overall economics of energy storage solutions. For battery systems, NPV is defined by Eq. (31):

LCOES is defined by Eq. (32):

where \({\Delta}\)Cimp,save refers to the cost saved by replacing grid electricity with renewable energy. \({\Delta}\)Crecyc refers to the cost of recycling EV batteries with RC at 80% and second-life batteries with RC at 60% (57 US$ kWh−1)82. \({\Delta}\)Crepl,new (125 US$ kWh−1)49, \({\Delta}\)Cremanu (40 US$ kWh−1)83, and \({\Delta}\)Crepur (35 US$ kWh−1)84 refers to the replacement, remanufacturing and repurposing cost for EV batteries and secondary-life batteries. For BIPV and wind turbine, the annual CO&M is 5% of the initial cost. For lithium-ion batteries, the annual CO&M is 0.5% of the initial cost. \({\Delta}\)ICRE and \({\Delta}\)ICbat are initial investment costs of renewable system (Solar PV, BIPVs and wind turbines) and batteries. Note that if the secondary-life battery reuse strategy is not adopted, \({\Delta}\)Crepl,new and \({\Delta}\)Crepur will be 0 due to the lack of purchase of new batteries and repurposing of retired batteries. Edis refers to the discharged energy from batteries.

For hydrogen systems, the price of electrolyzer and fuel cell is calculated by Eqs. (33–36)

PriceEC,recycle, material denotes the material cost of electrolyzer recycling, at 38.0 US$ per kW79, EEC,recycle, energy use is the energy consumption of electrolyzer recycling, at 38.9 kWh per kW79 Pricecoal base is the coal baseline electricity price in China, at 0.0514 US$ per kWh85. PriceEC,initial is the initial cost of buying electrolyzer, at 243.0 US$ per kW79.

The price of fuel cell

PriceFC,recycle, material denotes the material cost of fuel cell recycling, at 6.0 US$ per kW79, EFC,recycle, energy use is the energy consumption of fuel cell recycling, at 10.8 kWh per kW79. PriceFC, initial is the initial cost of buying fuel cell, at 96.5 US$ per kW17. NPV is defined by Eqs. (37–43):

where \({\Delta}\)CGrid, \({\Delta}{C}_{{{\mbox{H}}}_{2}}\), \({\Delta}\)CEC. \({\Delta}\)CHTK, \({\Delta}\)CFCEV, \({\Delta}\)CSB denote the benefits of hydrogen circular system compared with reference case, in terms of grid import cost, H2 cost, electrolyzer cost, hydrogen storage tank cost, FCEV degradation cost, and static battery cost, respectively. PImp, Grid, Circular and PImp, Grid, Ref case represents the electricity power imported from the grid in the hydrogen circular case and reference case, respectively. PriceGrid and \({{Price}}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}}\) represent the trading price of grid power and H2 in hydrogen station (it’s assumed the hydrogen price is all 4.28 US$ kg−1 across China). \({M}_{{{\rm{Imp}}},{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2},{{\rm{Circular}}}}\) and \({M}_{{{\rm{Exp}}},{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2},{{\rm{Circular}}}}\) represent the total mass of hydrogen imported from outside H2 station and exported to the outside FCEV in hydrogen circular case, unit in kg. \({M}_{{{\rm{Imp}}},{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2},{{\rm{Ref case}}}}\) and \(M_{{{\rm{Exp}}},{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2},{{\rm{Ref}}}\,{{{\rm{case}}}}}\) represent the total mass of hydrogen imported from outside H2 station and exported to the outside FCEV in reference case. PriceHTK and PriceSB are the price of hydrogen storage tank, at 600 US$ kg−1 H286 and 182 US$ per kWh49,82. \({{Deg}}_{{{\rm{FCEV}}},{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2},{{\rm{Circular}}}}\), DegFCEV, Ref case, \({{Deg}}_{{{\rm{SB}}},{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2},{{\rm{Circular}}}}\), and DegSB, Ref case are the degradation rate of fuel cell and static battery in the hydrogen circular case and reference case, respectively. CapacityEC, CapacityFC, CapacityHTK, and CapacitySB are the capacity of electrolyzer, fuel cell, hydrogen tank, and static battery, respectively.

The levelized cost of hydrogen (LCOH) from renewable energy is calculated in Eq. (44):

Data availability

The authors declare that the data used as model inputs supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplemental Information files. In addition, all data and calculation tables have been uploaded to https://zenodo.org/records/14964882.

Code availability

TRNSYS code and models used to generate the results reported in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Georgescu, M., Broadbent, A. M. & Krayenhoff, E. S. Quantifying the decrease in heat exposure through adaptation and mitigation in twenty-first-century US cities. Nat. Cities 1, 42–50 (2024).

Haddad, S. et al. Quantifying the energy impact of heat mitigation technologies at the urban scale. Nat. Cities 1, 62–72 (2024).

Zhou, Y. Climate change adaptation with energy resilience in energy districts—a state-of-the-art review. Energy Build. 279, 112649 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. Resilience of renewable power systems under climate risks. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 1, 53–66 (2024).

Adilkhanova, I., Santamouris, M. & Yun, G. Y. Green roofs save energy in cities and fight regional climate change. Nature Cities (2024).

DeRolph, C. R., McManamay, R. A., Morton, A. M. & Nair, S. S. City energysheds and renewable energy in the United States. Nat. Sustain. 2, 412–420 (2019).

Sterl, S. et al. Smart renewable electricity portfolios in West Africa. Nat. Sustain. 3, 710–719 (2020).

Lu, M., Zhou, C., Wang, C., Jackson, R. B. & Kempes, C. P. Worldwide scaling of waste generation in urban systems. Nat. Cities 1, 126–135 (2024).

Dowling, J. A. et al. Role of long-duration energy storage in variable renewable electricity systems. Joule 4, 1907–1928 (2020).

Zhou, Y. Transition towards carbon-neutral districts based on storage techniques and spatiotemporal energy sharing with electrification and hydrogenation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 162, 112444 (2022).

Xu, C. et al. Electric vehicle batteries alone could satisfy short-term grid storage demand by as early as 2030. Nat. Commun. 14, 119 (2023).

Giovanniello, M. A., Cybulsky, A. N., Schittekatte, T. & Mallapragada, D. S. The influence of additionality and time-matching requirements on the emissions from grid-connected hydrogen production. Nat. Energy 9, 197–207 (2024).

Popovich, N. D., Rajagopal, D., Tasar, E. & Phadke, A. Economic, environmental and grid-resilience benefits of converting diesel trains to battery-electric. Nat. Energy 6, 1017–1025 (2021).

Zhang, C., Zhao, X., Sacchi, R. & You, F. Trade-off between critical metal requirement and transportation decarbonization in automotive electrification. Nat. Commun. 14, 1616 (2023).

Luderer, G. et al. Impact of declining renewable energy costs on electrification in low-emission scenarios. Nat. Energy 7, 32–42 (2022).

Langevin, J. et al. US building energy efficiency and flexibility as an electric grid resource. Joule 5, 2102–2128 (2021).

Zhang, X. & Zhou, Y. Waste-to-energy (W2E) for renewable-battery-FCEV-building multi-energy systems with combined thermal/power, absorption chiller and demand-side flexibility in subtropical climates. Energy Build. 307, 113949 (2024).

Zhou, L., Song, A. & Zhou, Y. Electrification and hydrogenation on a PV-battery-hydrogen energy flexible community for carbon–neutral transformation with transient aging and collaboration operation. Energy Convers. Manag. 300, 117984 (2024).

Gao, B. & Zhou, Y. In-field experimental study and multivariable analysis on a PEMFC combined heat and power cogeneration for climate-adaptive buildings with Taguchi method. Energy Convers. Manag. 301, 118003 (2024).

Liu, R. et al. A cross-scale framework for evaluating flexibility values of battery and fuel cell electric vehicles. Nat. Commun. 15, 280 (2024).

Zhou, Y. & Zheng, S. A co-simulated material-component-system-district framework for climate-adaption and sustainability transition. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 192, 114184 (2024).

Peng, L., Mauzerall, D. L., Zhong, Y. D. & He, G. Heterogeneous effects of battery storage deployment strategies on decarbonization of provincial power systems in China. Nat. Commun. 14, 4858 (2023).

Chen, W. et al. A manganese–hydrogen battery with potential for grid-scale energy storage. Nat. Energy 3, 428–435 (2018).

Neumann, F., Zeyen, E., Victoria, M. & Brown, T. The potential role of a hydrogen network in Europe. Joule 7, 1793–1817 (2023).

Li, M. M., Weller, J. M., Reed, D. M., Sprenkle, V. L. & Li, G. Thermally activated batteries and their prospects for grid-scale energy storage. Joule 7, 619–623 (2023).

Yekini Suberu, M., Wazir Mustafa, M. & Bashir, N. Energy storage systems for renewable energy power sector integration and mitigation of intermittency. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 35, 499–514 (2014).

Peters, I. M. et al. The role of batteries in meeting the PV terawatt challenge. Joule 5, 1353–1370 (2021).

Bracci, J. M., Sherwin, E. D., Boness, N. L. & Brandt, A. R. A cost comparison of various hourly-reliable and net-zero hydrogen production pathways in the United States. Nat. Commun. 14, 7391 (2023).

Hunter, C. A. et al. Techno-economic analysis of long-duration energy storage and flexible power generation technologies to support high-variable renewable energy grids. Joule 5, 2077–2101 (2021).

Comello, S. & Reichelstein, S. The emergence of cost effective battery storage. Nat. Commun. 10, 2038 (2019).

Sahin, H., Solomon, A. A., Aghahosseini, A. & Breyer, C. Systemwide energy return on investment in a sustainable transition towards net zero power systems. Nat. Commun. 15, 208 (2024).

Yang, H., Deshmukh, R. & Suh, S. Global transcontinental power pools for low-carbon electricity. Nat. Commun. 14, 8350 (2023).

Glenk, G. & Reichelstein, S. Economics of converting renewable power to hydrogen. Nat. Energy 4, 216–222 (2019).

Guerra, O. J., Eichman, J., Kurtz, J. & Hodge, B.-M. Cost competitiveness of electrolytic hydrogen. Joule 3, 2425–2443 (2019).

Ueckerdt, F. et al. On the cost competitiveness of blue and green hydrogen. Joule 8, 104–128 (2024).

Kersey, J., Popovich, N. D. & Phadke, A. A. Rapid battery cost declines accelerate the prospects of all-electric interregional container shipping. Nat. Energy 7, 664–674 (2022).

Guo, Y., Peng, L., Tian, J. & Mauzerall, D. L. Deploying green hydrogen to decarbonize China’s coal chemical sector. Nat. Commun. 14, 8104 (2023).

Pell, R. et al. Towards sustainable extraction of technology materials through integrated approaches. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 665–679 (2021).

Harper, G. et al. Recycling lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles. Nature 575, 75–86 (2019).

Chen, M. et al. Recycling end-of-life electric vehicle lithium-ion batteries. Joule 3, 2622–2646 (2019).

Ziegler, M. S. et al. Storage requirements and costs of shaping renewable energy toward grid decarbonization. Joule 3, 2134–2153 (2019).

Milovanoff, A., Posen, I. D. & MacLean, H. L. Electrification of light-duty vehicle fleet alone will not meet mitigation targets. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 1102–1107 (2020).

Li, J., Wei, Y.-M., Liu, L., Li, X. & Yan R. The carbon footprint and cost of coal-based hydrogen production with and without carbon capture and storage technology in China. J. Clean. Prod. 362, 132514 (2022).

Zhu, W.-K., Wang, C.-y, Wang, L.-s, Wu, X.-h & Yue, Q. Analysis of energy-saving and environmental benefits from power structure adjustment in China: a comparative study from 2020 to 2060. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 31, 750–761 (2022).

Song, A., Dan, Z., Zheng, S. & Zhou, Y. An electricity-driven mobility circular economy with lifecycle carbon footprints for climate-adaptive carbon neutrality transformation. Nat. Commun. 15, 5905 (2024).

Han, X. et al. Comparative life cycle greenhouse gas emissions assessment of battery energy storage technologies for grid applications. J. Clean. Prod. 392, 136251 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Comparative techno-economic analysis of large-scale renewable energy storage technologies. Energy AI 14, 100282 (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. Comparative techno-economic evaluation of energy storage technology: a multi-time scales scenario-based study in China. J. Energy Storage 89, 111800 (2024).

Deshwal, D., Sangwan, P. & Dahiya, N. Economic analysis of lithium ion battery recycling in India. Wirel. Personal. Commun. 124, 3263–3286 (2022).

CHA. China Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Industry Handbook (2022).

Song, A. & Zhou, Y. A hierarchical control with thermal and electrical synergies on battery cycling ageing and energy flexibility in a multi-energy sharing network. Renew. Energy 212, 1020–1037 (2023).

Yan G., Liu D., Li J., Mu G. A cost accounting method of the Li-ion battery energy storage system for frequency regulation considering the effect of life degradation. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 3, 1–9 (2018).

Zhou Y., Cao S., Hensen J. L. M., Hasan A. Heuristic battery-protective strategy for energy management of an interactive renewables–buildings–vehicles energy sharing network with high energy flexibility. Energy Convers. Manag. 214, 112891 (2020).

Pei, P., Chang, Q. & Tang, T. A quick evaluating method for automotive fuel cell lifetime. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 33, 3829–3836 (2008).

Takahashi, T. et al. Accelerated durability testing of fuel cell stacks for commercial automotive applications: a case study. J. Electrochem. Soc. 169, 044523 (2022).

Shi W, Zhu J, Han M, Sun Z, Guo Y. Operating limitation and degradation modeling of micro solid oxide fuel cell-combined heat and power system. Applied Energy 252, 113444 (2019).

Tian, X., Zhou, Y., Morris, B. & You, F. Sustainable design of Cornell University campus energy systems toward climate neutrality and 100% renewables. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 161, 112383 (2022).

MOHURD. Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Residential Buildings in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone (JGJ 134-2010) (2010).

MOHURD. Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Residential Buildings in Hot Summer and Warm Winter Zone (JGJ 75-2012) (2012).

MOHURD. Design Code for Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning of Civil Buildings (GB 50736-2012) (2012).

MOHURD. Building Lighting Design Standard of China (GB 50034-2013) (2013).

MOHURD. Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings (GB 50189-2015) (2016).

MOHURD. Code for Thermal Design of Civil Building (GB 50176-2016) (2016).

MOHURD. Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Residential Buildings in Severe Cold and Cold Zones (JGJ 26-2018) (2018).

MOHURD. Technical Standard for Residential Outdoor Air System (JGJ/T 440-2018) (2018).

MOHURD. Standard for Design of Building Water Supply and Drainage (GB 50015-2019) (2019).

MOHURD. Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings in Guangdong Province (DBJ 15-51-2020) (2020).

MOHURD. General Code for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Application in Buildings (GB 55015-2021) (2021).

Ciez, R. E. & Whitacre, J. F. Examining different recycling processes for lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Sustain. 2, 148–156 (2019).

Li, G. et al. Life-cycle assessment of a low-concentration PV module for building south wall integration in China. Appl. Energy 215, 174–185 (2018).

Vargas, A. V. et al. Life cycle assessment: a case study of two wind turbines used in Mexico. Appl. Therm. Eng. 75, 1210–1216 (2015).

Smoucha, E. A., Fitzpatrick, K., Buckingham, S. & Knox, O. G. Life cycle analysis of the embodied carbon emissions from 14 wind turbines with rated powers between 50Kw and 3.4 Mw. J. Fundam. Renew. Energy Appl. 6, 1000211 (2016).

Yang, J. & Chen, B. Integrated evaluation of embodied energy, greenhouse gas emission and economic performance of a typical wind farm in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 27, 559–568 (2013).

Chen, G. Q., Yang, Q. & Zhao, Y. H. Renewability of wind power in China: a case study of nonrenewable energy cost and greenhouse gas emission by a plant in Guangxi. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15, 2322–2329 (2011).

Xie, J.-b., Fu, J.-x., Liu, S.-y. & Hwang, W.-s. Assessments of carbon footprint and energy analysis of three wind farms. J. Cleaner Prod. 254, 120159 (2020).

Ji, S. & Chen, B. Carbon footprint accounting of a typical wind farm in China. Appl. Energy 180, 416–423 (2016).

Savino, M. M., Manzini, R., Della Selva, V. & Accorsi, R. A new model for environmental and economic evaluation of renewable energy systems: the case of wind turbines. Appl. Energy 189, 739–752 (2017).

Miotti, M., Supran, G. J., Kim, E. J. & Trancik, J. E. Personal vehicles evaluated against climate change mitigation targets. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 10795–10804 (2016).

Uekert, T., Wikoff, H. M. & Badgett, A. Electrolyzer and fuel cell recycling for a circular hydrogen economy. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 8, 2300449 (2023).

Raimundo, R. C. et al. A sustainable alkaline membrane fuel cell (SAMFC) stack characterization, model validation and optimal operation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45, 5723–5733 (2020).

US Department of Energy. Energy requirements for hydrogen gas compression and liquefaction as related to vehicle storage needs. (2009).

Lander, L. et al. Financial viability of electric vehicle lithium-ion battery recycling. iScience 24, 102787 (2021).

Murdock, B. E., Toghill, K. E. & Tapia‐Ruiz, N. A perspective on the sustainability of cathode materials used in lithium‐ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2102028 (2021).

Neubauer, J., Smith, K., Wood, E. & Pesaran, A. Identifying and Overcoming Critical Barriers to Widespread Second Use of Pev Batteries (2015).

Zhou, Y. Energy sharing and trading on a novel spatiotemporal energy network in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Appl. Energy 318, 119131 (2022).

Shin, H. K. & Ha, S. K. A review on the cost analysis of hydrogen gas storage tanks for fuel cell vehicles. Energies 16, 5233 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (52408137), Guangdong Provincial Natural Science Foundation General Project (2414050003253, 2024A1515011609), Yangcheng Scholars Leading Talent Training Project (2024312133). This research is also supported by The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou) startup grant (G0101000059). This work was supported in part by the Project of Hetao Shenzhen-Hong Kong Science and Technology Innovation Cooperation Zone (HZQB-KCZYB-2020083).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.Z.; methodology: Y.Z., A.S. and X.Z.; software: A.S. and X.Z.; formal analysis: A.S., X.Z. and Y.Z.; writing: Y.Z., A.S., X.Z. and Z.D.; visualization: A.S., X.Z. and Z.D.; supervision: Y.Z.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Mengyu Li, Rhythm Singh, and Yinyan Liu for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Miranda Vinay]. Peer review reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, A., Zhang, X., Dan, Z. et al. Lifecycle carbon intensity with embodied emissions of battery and hydrogen-driven integrative low-carbon systems. Commun Eng 4, 84 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00411-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00411-8

This article is cited by

-

Optimizing CHP-based multi-carrier energy networks with advanced energy storage solutions

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Hybrid forecasting and optimization framework for residential photovoltaic-battery systems: Integrating data-driven prediction with multi-strategy scenario analysis

Building Simulation (2025)