Abstract

Arsenic contaminants exist in different chemical forms with varying toxicity and mobility, making on-site analysis challenging. Here, a fluorogenic method is developed for the efficient detection of arsenite and arsenate ions using a portable platform directly in an aqueous phase. During sensing, the aggregation-induced emission (AIE) probe TPE-Cys/TPE-2Cys exhibits low fluorescence when dissolved, but reacts with the As(III) to form organic arsenic complexes with low solubility, inducing a turn-on fluorescence for quantitative analysis. Using a prior reduction strategy, the As(V) can be converted to As(III) and further analyzed in a sequential detection. Using a specialized laser-induced fluorescence instrument, this strategy allows on-site analysis of As(III) and As(V) species with sensitivity down to 0.14 ppb in environmental samples, showing that As(III) dominates while the As(V)/As(III) ratio varies in a constitutional equilibrium. The system has potential for the practical analysis of complex arsenic, revealing the dynamic arsenic transformations in the environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arsenic contamination of water resources is a major public health threat1,2, with approximately 230 million people currently suffering from arsenic poisoning3. Arsenic contaminants can accumulate in tissues such as the liver, kidneys and bones through respiratory, dietary or dermal exposure, leading to chronic and acute toxic arsenic poisoning4,5. They can disrupt the digestive and nervous systems, cause skin disorders, black foot, neuropathy, blood vessel damage, and increase the risk of heart disease6. As a group of human carcinogens, long-term exposure to arsenic can cause cancer of the liver, lung, kidney, and bladder7. Therefore, the detection and real-time analysis of arsenic species present in industrial effluents and natural waters is essential for public health and sustainable economic development.

In the natural aqueous environment, arsenic contaminants exist in various forms with different oxidation valences8, including mainly inorganic arsenite As(III), arsenate As(V), and organic arsenic (such as monomethylarsenic acid, dimethylarsenic acid, and trimethylarsenic acid)1,9,10. These arsenic species also combine with natural organic substances to form various composite structures11. The toxicity of the different forms of arsenic varies considerably: As(III) » As(V) > organic arsenic, and importantly, they can be rapidly transformed into each other12. For example, As(III) is easily oxidized to the As(V) by Fe3+ species, usually within 1–3 minutes13,14, whereas, under flooding conditions, As(V) can be converted to the more toxic trivalent As(III) with microbial activity15. In general, the equilibrium between As(III) and As(V) varies with the pH and oxygen content of the chemical environment16, while arsenite As(III) is 25–60 times more toxic than arsenate As(V) and is also much more mobile in natural environments17. Therefore, how to accurately analyze the chemical dynamic components of co-existing and variable arsenic in situ under complex conditions remains one of the key technical challenges to be solved.

Currently, a number of analytic methods have been proposed for arsenic detection in water, including atomic emission/absorption spectrometry18,19 and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry20,21,22. These measurements are mostly unable to accurately distinguish between arsenic species of different valence states, and often require complicated pre-treatment protocols for environmental samples, expensive instrumentation with limited portability, and professional operation, making them ineffective for on-site detection. Molecular fluorescence-based chemical sensing is a class of analytical methods that are highly sensitive to different metal valences/forms. In particular, fluorogenic sensing using aggregation-induced emission (AIE) sensors has emerged in recent years as a versatile and potent strategy for the on-site detection and analysis of a range of water contaminants23,24. AIE fluorophores with a flexible molecular backbone emits weakly when dissolved in good solvents in molecular form, but their luminescence is enhanced when aggregated in poor solvents or solid forms due to restricted intramolecular motion (RIM)25,26. This fluorogenic response can also be activated by many other molecular rigidification effects such as metal coordination, molecular encapsulation, physical adsorption and so on. Such AIE-based contaminant analysis has a high degree of anti-interference capability and sensitivity. It effectively avoids the problems of signal selectivity and background interference caused by heavy metal quenching fluorescence in traditional fluorescence analysis. In addition, specific target aggregation can be used as an additional concentration strategy in the detection process. These features make it effective for practical on-site analysis in remote locations.

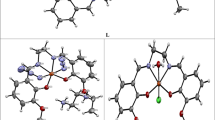

In this work, we report a fluorogenic sensing system for the sensitive and efficient simultaneous quantification of As(III) and As(V) components in aqueous phase. It utilized cystine-functionalized tetraphenylethene derivatives such as TPE-Cys, consisting of an AIE-active tetraphenylethylene core and N-acylated cysteine moieties (Fig. 1). During sensing, the prototypical TPE-Cys reacts with As(III) via a thiol-As(III) coordination reaction in a ‘click’ fashion to form the organic compound As(TPE-Cys)3, which spontaneously aggregates in the aqueous phase to induce turn-on fluorescence (Fig. 1a)18. In comparison, this probe reacts with the As(V) to form the disulfide complex (TPE-Cys-S-S-Cys-TPE), which has good solubility in water and maintains low emission (Fig. 1b). This system has been shown to detect As(III) in mixed tetrahydrofuran (THF)/water solvents, but has not been developed for direct on-site analysis of water samples18. In this work, the structural design of the probe, e.g. TPE-2Cys with additional cysteine moieties (Supplementary Fig. 2), as well as the environmental solvent properties (such as ionic strength and pH) were investigated to further enhance the aggregation-induced emission sensing performance. Importantly, we propose a strategy to measure the total arsenic by using L-ascorbic acid as a suitable reducing agent to rapidly transfer the As(V) to the As(III) (Fig. 1c). Fitted to a home-built laser-induced fluorescence analytical setup, this chemical sensing system demonstrates excellent performance for environmental water samples, providing selective and quantitative detection of trivalent arsenic and pentavalent arsenic with good sensitivity (down to 0.14 ppb). We studied the As(III)-thiol reaction-based fluorogenic process and also discussed the key issues for the on-site implementation of the fluorogenic As(III)/As(V) measurement system for natural groundwater samples, providing a solid basis for further field testing.

Results and Discussion

Determination of As(III)

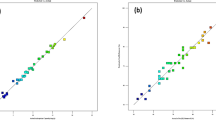

The probe TPE-Cys exhibited limited solubility in ultrapure water, with partial dissolution occurring at a concentration of 10 μM. The solubility of these probes increased when the carboxylic acid substituent underwent complete deprotonated in a slightly basic pH environment. The probe displayed enhanced fluorescence when the molecules were precipitated out in a mixed solution (Supplementary Fig. 3). Upon dissolution at 10 μM in an aqueous pH = 7.2 solution, the probe exhibited a faint fluorescence emission at 474 nm (black line, Fig. 2a), which was predominantly attributed to the unrestricted rotational motions of the Ph rings, resulting in the populated non-radiative decay of the photoexcited states. As expected, the addition of Arsenite solution lighted up a sky-blue fluorescence which peaked at 474 nm by 320 nm light excitation (Fig. 2a). The luminescence exhibited a gradual progression over the course of several minutes (Supplementary Fig. 4), rather than an immediate response. The light up process was clearly visualized under a hand-held ultraviolet (UV)-lamp (inset image of Fig. 2b). When the final concentration of the probe was fixed at 10 µM, a stoichiometric titration study showed that the fluorescence signal increased stepwise with the addition of As(III) ions. By plotting the intensity of the fluorescence at 474 nm against the equivalence ratio [As(III)]/[TPE-Cys], a linear relationship with R2 = 0.957 was established in the range of 0.08 ~ 9 µM for [As(III)] ions with a LOD (Limit of detection) of 5.78 ppb/77 nM (Fig. 2b). With a further increase of [As(III)] from <10 equiv. of [TPE-Cys], the fluorescence intensity reached a relatively steady plateau.

a Fluorescence spectra of 10-5 M TPE-Cys in 0–70 µM solution of As(III). b Plot of intensity at 474 nm in (a) as a function of As(III), n = 3. c UV–vis spectra of probes in the presence/absence of As(III). d Dynamic light scattering particle size distribution of probe TPE-Cys (10-5 M) with As(III) (10-5 M) and corresponding scanning electron microscope image. [TPE-Cys] = 10-5 M.

The fluorescence sensing process was accompanied by the formation of micro/nano-sized aggregates. By examining the UV–vis adsorption spectra of the TPE-Cys solution before and after the addition of As(III), we can see that there was an obvious trailing phenomenon in the range of 400–700 nm without any obvious change in the peak shape, which may be a result of Mie scattering of nanoaggregates formed by the reaction of As(III) with the probe (Fig. 2c). In addition, dynamic light scattering (DLS) characterization of the mixture ([TPE-Cys] = 10 μM, [As(III)] = 10 μM) gave an effective diameter size (Eff. d.) = ∼96.4 nm with a polydispersion index (PDI) of 0.31 (Fig. 2d). When the mixture was rapidly dried out on a dry silicon wafer, micro/nano-sized aggregates were observed to be partially fused together by scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 2d), which correlated with the DLS result. These colloidal aggregates showed good colloidal stability within hours and fluoresced steadily, which is suitable for robust quantification measurement in fluorescence analysis.

Interestingly, the sensor system can distinguish between trivalent and pentavalent arsenic species. Under similar conditions, the addition of arsenate As(V) didn’t lead to a increase in fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 5). It was shown that the As(V) reacted with the probe, but was likely oxidised to form an S-S bridged dimer (TPE-Cys-S-S-Cys-TPE) (Fig. 1b)18. This dimer component is similar to the probe in solution and is likely to remain dispersed in aqueous solutions, thus not affecting the overall fluorescence response in the measurement. In a controlled experiment with both As(III) and As(V), the mixture showed increasing fluorescence, reaching a relatively stable plateau after ~40 min (Supplementary Fig. 6). In this case, both As(V) and As(III) species reacted with the Cys moiety. The As(V) first led to the formation of the dimer, which then underwent exchange equilibrium to give the final As(TPE-Cys)3 complex (Fig. 1a).

Determination of [As(III) + As(V)]

In view of the selective chemistry between the probe and As(III) and As(V) species, an investigation was conducted into a number of reducing agents with the potential to convert As(V) to As(III) prior to measurement in aqueous solutions11,27. Ascorbic acid was identified as an effective reducing agent, suitable for the quantification of total arsenic [As(III) + As(V)]28. By employing this prior reducing strategy, a quantitative relationship between fluorescence intensity and concentrations of total arsenic solutions was established in the laboratory (Fig. 3). In the optimized protocol, the reducing agent was added to the sample solution at a final concentration of 100 µM. Subsequently, an aliquot of the TPE-Cys probe solution (final concentration of 10 μM) was added. Following a gentle shaking, the fluorescence emission spectrum was recorded, demonstrating a pronounced emission response at Ex/Em = 320/474 nm. By plotting the intensity of the fluorescence maximum against the equivalence ratio [total arsenic]/[TPE-Cys], a linear relationship with R2 = 0.990 was established in the range of LDR (Linear dynamic range) = 0.1 ~ 9 µM (Fig. 3b). It is notable that the linear relationship and molar ratio of arsenic ions to cysteine groups at 1:3 near the plateau indicates that the sensing process is closely related to the stoichiometric coordination reaction-driven assembly. The limit of detection (LOD) was calculated to be 4.65 ppb/62 nM, which meets the 10 ppb alarming limit for drinking water set by the World Health Organization (WHO)29. Compared with earlier reports30,31,32,33, TPE-Cys has a lower detection limit and an appropriate linear range (Supplementary Table 1). It is noteworthy that the use of the ascorbate reducing agent also facilitated the measurement process, with the fluorescence response reaching a steady state within minutes. The probe TPE-Cys has almost no fluorescence response to As(V) without the addition of the reducing agent ascorbic acid (Supplementary Fig. 5). In the absence of ascorbate in the arsenic solution, the probe was unable to achieve an instantaneous fluorescence response during the detection of trivalent arsenic, necessitating a prolonged signal stabilization period (approximately 30 min, Supplementary Fig. 4).

With reference to the above protocols, we carried out experiments for the quantitative detection of As(III) and As(V) based on the fluorescence difference in the presence and absence of reducing reagent. The As(V) content was obtained indirectly by substitution of the fluorescence curves and linear fitting of As(III) and [As(V) + As(III)], as in a proof-of-concept study using a series of arsenic samples (Table 1). These samples were prepared by diluting a standard solution of Na3AsO3 (100 µM) and left for months. Therefore, part of the As(III) species were oxidized to As(V) by the oxygen in the air. As shown, the ratio of trivalent arsenic to pentavalent arsenic, As(III)/As(V), remained relatively stable in the range of 0.40–0.71 as the total arsenic concentration increased (Table 1). It is reasonable that the increasing ratio of As(III) in the mixture is probably due to the limited access of oxygen oxidation at high As(III) concentrations. In this sense, this method provides a quick and efficient way to check the quality of variable arsenic samples.

Sensing performance in the presence of interferences

In order to explore this method for aqueous environmental samples, this sensor system was next evaluated in the presence of interfering factors, including various metal cations and anions commonly encountered in practical water analysis. The AIE sensor was tested in a range of pH solutions (Supplementary Fig. 7). The maximum fluorescence response was maintained at a relatively stable level from slightly acidic to slightly basic aqueous solutions, indicating a robust quantification method. Since trivalent/pentavalent arsenic species are present in aqueous solution as anions, we investigated the selectivity and interference of the probe to common anionic components in water. As shown, the system only showed obvious fluorescence response only to trivalent arsenic [AsO33-], and other anions (including Cl-, I-, HCO3-, NO3-, Br-, SO42-, CH3COO-, PO43-, H2PO4-, HPO42-, AsO43-,) cannot light the probe (Fig. 4a, b). Furthermore, the probe system retained the sensitive and stable response to trivalent arsenic ([AsO33-] = 10 μM) without being affected by the presence of other anions (30 μM) (Fig. 4c). These results suggest that this system may be effective for water samples with high concentrations of halogen salts, which are commonly encountered in environmental water analysis. The sensitivity of TPE-Cys (10 μM) to different metal ions was then measured in aqueous phosphate solution at pH = 7.2. Since arsenic exists in the form of anionic arsenate or arsenite, the cationic shielding agent EGTA (glycol diethyl ether diamine tetraacetic acid) was used to shield cationic metal ions that can bind to the cysteine moiety. As shown, metal ions (10 μM) including Cu2+, Ni2+, Co2+, Ca2+, Fe3+, Cr3+, Al3+, Pb2+, Mn2+, K+, Na+, Fe2+, Mg2+, Zn2+ and Cd2+ could not activate the AIE fluorescence in the presence of the shielding agent, as compared to the blank group (Fig. 4d). Importantly, the fluorescence response of the probe (10 μM) to As(III) (10 μM) in the presence of EGTA (30 μM) was not affected by the presence of these cationic metal ions (30 μM), including in particular Fe3+, Cu2+, Ni2+ and Co2+, which are conventionally interfering ions in environmental samples (Fig. 4f).

a Fluorescence spectra of probe TPE-Cys in solution of different anions (Cl-, I-, HCO3-, NO3-, Br-, SO42-, CH3COO-, PO43-, H2PO4-, HPO42-, AsO43-). b Comparison of peak fluorescence intensity of metal salt solution at 474 nm with TPE-Cys aqueous solution as unit. c Comparison of I/Iblk fluorescence intensity between the probe and a mixture of As(III) (10 µM) and other anion concentrations of 30 µM (Black bar, interfering anions; Red bar, interfering anions mixed with As(III)). d Fluorescence spectra of the probe TPE-Cys in solutions of different metal ions (Cu2+, Ni2+, Co2+, Ca2+, Fe3+; Cr3+, Al3+, Pb2+, Mn2+, K+, Na+, Fe2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Cd2+). e Comparison of peak fluorescence intensity of salt solution at 474 nm with TPE-Cys aqueous solution as unit. f Comparison of I/IBLK fluorescence intensity between the probe and As(III) (10 µM) and other metal ion concentrations of 30 µM (black bar, interfering metal ions; red bar, interfering metal cations mixed with As(III)).

Sensing analysis of groundwater samples

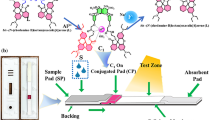

As shown above, the sensing system for both As(III) and As(V) is quite unique and has the advantages of low detection limit, wide linear detection range, good selectivity and strong anti-interference ability. Considering the requirements of environmental water analysis in terms of portability, reliability and convenience, we envisioned to integrate this fluorescence sensing system into a homemade fibre-based portable fluorescence platform. The platform consists of a conventional LIFs (Laser-induced Fluorescence Setup), designed to fit the sensor system and allow sensitive and convenient analysis of natural samples (Supplementary Fig. 3). The homemade device is mainly divided into three parts: (1) the underwater detector consisting of an optical module, a liquid chamber and a pump, (2) the spectral analysis module, (3) the drive control and data processing module (Supplementary Fig. 3). During the detection process, the underwater detector operates in a completely sealed state with the aid of an electric pump. This design allows the detector to enter groundwater wells for groundwater testing. The titration calibration was performed using this portable fluorescence platform and showed a good linear relationship of R2 = 0.99 in the range of 0–400 ppb for As(III) (Supplementary Fig. 9). The fluorescence intensity of the probe solution without As species was repeatedly tested 10 times to obtain the mean value k and the standard deviations. As a result, the LOD of the probe was obtained by the formula LOD = 3 s/k, as 0.14 ppb, by using the specific sensor system.

The workflow is illustrated in Fig. 5. Two aliquots of water samples were pumped from the natural water sources and filtered through a 450 nm filter membrane. One water sample was directly subjected to the sensor system consisting of the shielding EGTA agent and the probing TPE-Cys solution, which was then measured to indicate the [As(III)] in the sample. In parallel, the other sample was first treated with the reducing agent (sodium ascorbate) for 2 min and then mixed with the sensing aliquot consisting of the shielding EGTA agent and the probe. Fluorescence was then measured and compared to the calibration curves. The total analysis of both samples would give information on As(III) and As(III) + As(V), which can be used to deduce the As(V) concentration in the absence of other types of arsenic ions.

Prior to analysis, the natural water samples were filtered in order to remove insoluble particles. The water sample was initially treated with the shielding agent EGTA, after which it was divided into two portions. Subsequently, one of the samples was then combined with the reducing agent. Each solution sample was combined with a 1 mM probe solution, resulting in a test solution with a total volume of 5 mL in the detector. The fluorescence intensities of the solutions were recorded, thereby allowing the concentrations of As(III) and As(V) to be determined.

The fluorescence sensor protocol was then employed for the quantification of As(III) and As(V) in natural groundwater samples (Table 2). The groundwater sampling sites are from a conventional smelter in southwest China with a geologically high heavy metal background area. The arsenic smelter was in operation from 1992 to 2003. The depth of groundwater sampling was approximately 15 metres. Table 2 presents a summary of the arsenic component values from three different environmental samples obtained through the current fluorescence analysis method, and by atomic fluorescence spectrometry (AFS) analysis. The [As(III) + As(V)] values obtained using the novel fluorescence method demonstrated a robust correlation with the conventional AFS results (203.9 vs 210.0 ppb, 353.3 vs 357.0 ppb, 384.9 vs 400.5 ppb), thereby substantiating the satisfactory accuracy of the method. To be noted, a comprehensive metal analysis revealed the presence of Zn2+, Ni2+, Cd2+ and Pd2+ as the predominant ions, in addition to arsenic, with varying concentrations observed across the three different samples. Furthermore, the AIE-based method yielded results for both [As(V)] and [As(III)], indicating that the ratio of As(V)/As(III) in the three environmental samples was approximately 47.2%, 15.6%, and 15.4%. The distinctly different As(III)/As(V) ratios suggest the existence of a complex arsenic dynamic within natural systems, which may be amenable to modulation by a range of oxidative chemical components. In the quantitative measurement, the recovery ratio of natural samples was found to be 97.1%, 98.9%, and 96.1%, with a relative standard deviation (RSD) of 8.3%, 4.4%, and 6.6% for the three sites, respectively. These results suggest that the current fluorescent methods are effective for practical analysis.

Conclusions

In complex environments, arsenite and arsenate are capable of undergoing conversion processes to one another. Moreover, arsenite is markedly more toxic and mobile than arsenate. In this study, a fluorescence sensing system was developed for the on-site quantitative sensing of As(III) and As(V) in an aqueous phase using a portable fluorescence platform. The use of the L-ascorbic acid agent and the incorporation of suitable buffering and shielding reagents in the protocol enable this cascade sensing system to demonstrate excellent performance for environmental samples. This enables the selective and quantitative detection of both As(III) and As(V) with high sensitivity down to 4.65 ppb. In a proof-of-concept study, the protocol was employed to analyze underground water samples on-site, providing both As(III) and As(V) values that correlated with the AFS measurement. This method allows for the accurate analysis of the dynamic equilibrium between As(III) and As(V), revealing that As(III) is the predominant form while the As(V)/As(III) ratio varies in accordance with the chemical environment for underground samples. These findings suggest that the current sensing system has potential for the analysis of complex arsenic forms, and may facilitate the elucidation of the dynamic arsenic network within the environmental context.

Methods

Chemicals and instruments

The probe TPE-Cys was synthesized according to a modified protocol in the supporting information (Supplementary Fig. 1)18. The probe TPE-2Cys was synthesized according to the synthetic route in the supporting information (Supplementary Fig. 2). The optofibre-based portable fluorescence platform used in this work was designed and assembled in the laboratory (c.f., Supplementary Fig. 3 for more information) and was used in our previous publications34,35,36.

Preparation of sodium arsenite and sodium arsenite mother liquor

(1) 20.0 mg of arsenic trioxide was weighed and dissolved in a 100 mL beaker, 5 mL of 0.1 M sodium hydroxide was added to dissolve the arsenic trioxide completely, 0.1 M HCl was added to make the pH = 7, the solution was transferred to a 100 mL graduated flask and 1 mM sodium arsenite mother liquor was prepared. (2) 0.042 g of sodium arsenate was weighed and then completely dissolved in deionised water by ultrasonication. The mother liquor of 1 mM sodium arsenate was prepared in a volumetric flask with a fixed volume of 100 mL. The above solution can be used to dilute the mother liquor to the required concentration according to the needs of the subsequent experiments.

Conventional procedure for the quantification of As(III)

(1) Standard curve of ion concentration versus fluorescence intensity. Following the mixing of 1.78 mL deionized water with 0.20 mL sodium arsenite solution of varying concentrations, the addition of 0.02 mL TPE-Cys standard solution (1 mM), agitation, and a 30-minute standing period, the mixture was then examined in the fluorescence spectrometer. The fluorescence peak intensities corresponding to the concentrations of sodium arsenite were plotted on the ion concentration-fluorescence intensity standard curve, with the X and Y axes, respectively. (2) Sample testing: 1.78 mL of water was thoroughly mixed with 0.20 mL of the sample solution, and 0.02 mL of the TPE-Cys (1 mM) standard solution was added. The fluorescence intensity of the sample was then checked under the same test conditions as in (1).

Conventional procedure for the quantification of total arsenic

(1) A standard curve of ion concentration versus fluorescence intensity was constructed. A reducing agent (L-ascorbic acid, 1 mM) was introduced to the mother liquor of sodium arsenite employed in the aforementioned experiment, resulting in the reduction of As(V) in the solution to As(III). Subsequently, 1.78 mL of deionised water was combined with 0.20 mL of arsenic solutions at varying concentrations, and 0.02 mL of a TPE-Cys solution (1 mM) was introduced. Following oscillation and mixing, test after balancing for 1 min, excitation/emission slit parameters were modified in order to record the fluorescence spectrum. The fluorescence peak intensities corresponding to the concentrations of total arsenic were plotted on the ion concentration-fluorescence intensity standard curve, with the X and Y axes, respectively, representing these variables. (2) Sample testing: 1.78 mL of deionised water was combined with 0.20 mL of the sample solution and 0.02 mL of the TPE-Cys (1 mM) standard solution. The fluorescence intensity of the sample was then evaluated under the identical test conditions as those employed in (1).

Tests to evaluate the sensing performance in the presence of interferences

In the experiment, 1 mM probe TPE-Cys solution was combined with a certain concentration of metal ions (Cu2+, Ni2+, Co2+, Ca2+, Fe3+, Cr3+, Al3+, Pb2+, Mn2+, K+, Na+, Fe2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Hg2+, Cd2+, As5+). After mixing and balancing the salt solution for 1 min, the selectivity of the probe is reflected based on the change in fluorescence intensity of the probe at 474 nm. Similarly for anion selectivity, a 10 µM probe TPE-Cys solution is combined with a certain concentration of anions (Cl-, I-, HCO3-, NO3-, Br-, SO42-, CH3COO-, PO43-, H2PO4-, HPO42-, AsO43-) The salt solution was mixed and the selectivity of the probe was reflected according to the change of fluorescence intensity of the probe at 474 nm. In the interference experiment, we first added 20 µL of 1 mM probe into a certain concentration of different metal salt solutions (30 µM) to test the fluorescence intensity of their mixtures, and then added a final concentration of 10 µM of trivalent arsenic water solution to them, and then tested the fluorescence intensity of their mixtures.

Sensing analysis of groundwater samples

The contents of As(III) and As(V) in water samples were determined by probe TPE-Cys. The groundwater comes from a conventional smelter in southwest China with a geologically high heavy metal background area. The samples contains many kinds of metal ions. Firstly, a certain amount of cationic shielding agent is added to the water sample to shield the interference of other metal ions. Then the fluorescence intensity was measured by adding 50 µL of 10-3 M probe TPE-Cys solution and configuring a total volume of 5 mL test solution. After adding the reducing agent L-ascorbic acid to the water sample, balance for 1 min, fluorescence detection was performed. The actual concentration of As(III) was obtained by substituting the fluorescence intensity of the solution without reducing agent into the above linear equation, and the total amount of arsenic was obtained by substituting the fluorescence intensity of the solution with reducing agent into the above linear equation. The arsenic pentavalent content is obtained indirectly by subtracting the actual arsenic trivalent content from the total arsenic content. The total arsenic content was compared with the arsenic concentration determined by AFS method, and the recovery rate was obtained.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The source data underlying the graphs and charts in the main figures are uploaded as Supplementary Data 1.

References

Oremland, R. S. & Stolz, J. F. The ecology of arsenic. Science 300, 939–944 (2003).

Podgorski, J. & Berg, M. Global threat of arsenic in groundwater. Science 368, 845-850

Bhattacharyya, R. et al. High arsenic groundwater: Mobilization, metabolism and mitigation-an overview in the Bengal Delta Plain. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 253, 347–355 (2003).

Ashraf, S. et al. Definition and chemical prologue of heavy metals: Past, present and future Scenarios. ACS. Symposium. Series. 1456, 25–48 (2023).

Kiran, R. B. & Sharma, R. Effect of heavy metals: an overview. Mater. Today. Proc. 51, 880–885 (2022).

Mohan, D. & Pittman, C. U. Arsenic removal from water/wastewater using adsorbents. J. Hazard. Mater. 142, 1–53 (2007).

Yoshida, T., Yamauchi, H. & Fan, S. G. Chronic health effects in people exposed to arsenic via the drinking water: dose-response relationships in review. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 198, 243–252 (2004).

Kaur, H., Kumar, R., Babu, J. N. & Mittal, S. Advances in arsenic biosensor development-A comprehensive review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 63, 533–545 (2015).

Devi, P. et al. Progress in the materials for optical detection of arsenic in water. Trends Analyt. Chem. 110, 97–115 (2019).

Wallis, I. et al. The river-groundwater interface as a hotspot for arsenic release. Nat. Geosci. 13, 288–295 (2020).

Bhat, A., Hara, T. O., Tian, F. & Singh, B. Review of analytical techniques for arsenic detection and determination in drinking water. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2, 171–195 (2023).

Vahter, M. Mechanisms of arsenic biotransformation. Toxicology 181, 211–217 (2002).

Tong, M. et al. Electrochemically induced oxidative precipitation of Fe(II) for As(III) oxidation and removal in synthetic groundwater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 5145–5153 (2014).

Fang, Y. et al. Highly efficient in-situ purification of Fe(II)-rich high-arsenic groundwater under anoxic conditions: Promotion mechanisms of PMS on oxidation and adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 453, 139915 (2023).

Priyadarshni, N., Nath, P., Nagahanumaiah & Chanda, N. Arsenic release from flooded paddy soils is influenced by speciation, Eh, pH, and iron dissolution. Chemosphere 83, 925–932 (2011).

Jadhav, S. V. et al. Arsenic and fluoride contaminated groundwaters: A review of current technologies for contaminants removal. J Environ. Manage. 162, 306–325 (2015).

Zhu, N. et al. Investigating photo-driven arsenics’ behavior and their glucose metabolite toxicity by the typical metallic oxides in ambient PM2.5. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 191, 110162 (2020).

Baglan, M. & Atılgan, S. Selective and sensitive turn-on fluorescent sensing of arsenite based on cysteine fused tetraphenylethene with AIE characteristics in aqueous media. Chem. Commun. 49, 5325–5327 (2013).

Carter, S., Clough, R., Fisher, A., Gibson, B. & Russell, B. Atomic spectrometry update: review of advances in the analysis of metals, chemicals and materials. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 37, 2207–2281 (2022).

Deng, X. O. et al. Sensitive Determination of Arsenic by photochemical vapor generation with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry: Synergistic effect from Antimony and Cadmium. Anal. Chem. 96, 652–660 (2024).

Pal, S. K., Akhtar, N. & Ghosh, S. K. Determination of arsenic in water using fluorescent ZnO quantum dots. Anal. Methods. 8, 445–452 (2016).

Kayal, S. & Halder, M. A ZnS quantum dot-based super selective fluorescent chemosensor for soluble ppb-level total arsenic [As(III) + As(V)] in aqueous media: direct assay utilizing aggregation-enhanced emission (AEE) for analytical application. Analyst. 144, 3710–3715 (2019).

Tang, B. Z. et al. Environmental science of aggregation-induced luminescence. China: China Science Publishing & Media Ltd, 2023. (in Chinese).

Ren, K. et al. Aggregation-induced emission(AIE)for next-generation biosensing and imaging: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 271, 117067 (2025).

Feng, G. X. et al. Functionality and versatility of aggregation-induced emission luminogens. Appl. Phys. Rev. 4, 021307 (2017).

Xie, Y. J. & Li, Z. Development of aggregated sate chemistry accelerated by aggregation-induced emission. Natl. Sci. Rev. 8, nwaa199 (2021).

Stanic, A., Jovanic, S., Marjanovic, N. & Suturovic, Z. The use of L-ascorbic acid in speciation of arsenic compounds in drinking water. Acta Per Tech 40, 165–175 (2009).

Oksuiz, N., Sacmaci, S., Sacmaci, M. & Ulgen, A. A new fluorescence reagent: Synthesis, characterization and application for speciation of arsenic (III)/(V) species in tea samples. Food Chem 270, 579–584 (2019).

Song, R. et al. Highly selective and sensitive detection of arsenite ions(III) using a novel tetraphenylimidazole-based probe. Anal. Met. 13, 5011–5016 (2021).

Nandi, S., Sahana, A. & Das, D. Pyridine based fluorescence probe: ssimultaneous Detection and removal of arsenate from real samples with living cell imaging properties. J. Fluoresc. 25, 1191–1201 (2015).

Aatif, A. M. & Ashok, K. S. K. Dual anion colorimetric and fluorometric sensing of arsenite and cyanide ions involving MLCT and CHEF pathways. J. Mol. Struct. 1250, 131677 (2022).

Yang, B. et al. A turn-on response fluorescent probe based on triphenylamine derivative for detection of AsO43- in water samples and cells. Spectrochim. Acta - A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 331, 125814 (2025).

Tian, X. et al. Design and synthesis of a molecule with aggregation-induced emission effects and its application in the detection of arsenite in groundwater. J. Mater. 15, 3669–3672 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. LIFs-Based fluorescent analysis of Silver ions in water using AIE gen-embedded PVA hydrogel. Luminescence 39, e70017 (2024).

Zhu, X. Q. et al. Study of groundwater heavy metal In-situ fluorescence detection device. Adv. Laser and Optoelectron 60, 2130001 (2023). (in Chinese).

Wu, S. J. et al. Fluorogenic detection of mercury ion in aqueous environment using hydrogel-based AIE sensing films. Aggregate 4, e287 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFC1807302), and Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20220530160403008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.F. and S.W. performed the fluorescence measurements and analysis and optimised the sensing protocol. Q.B. and S.W. designed and carried out the synthesis of TPE-Cys/TPE-2Cys. T.G. and P.Z. assembled the special optical fibre-based fluorescence sensing system. L.F. and S.D. performed the field analysis in the wild field. Z.Z. and S.X. supervised the work. L.F. and S.X. wrote the paper. All authors approved the submission of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Manal Ali, Chihiro Yoshimura and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Manabu Fujii] and [Rosamund Daw]. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, L., Bian, Q., Wu, S. et al. On-site quantitative analysis of As(III) and As(V) in aqueous phase using portable laser-induced fluorescence platform. Commun Eng 4, 137 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00473-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00473-8