Abstract

XYθz nanopositioners are robots that can deliver precise translations along the X- and Y-axes and rotations about the Z-axis via elastic deformation of their compliant bodies. Although the performance of these robots is critical across a vast range of microscopy technologies, biomedical research and industrial applications, existing XYθz nanopositioners are unable to optimize their workspace, disturbance rejection capabilities, speed and positioning resolutions. This is because their stiffness ratios are limited to 0.5–248 and their mechanical bandwidths are restricted to 70 Hz when they can deflect more than 2 mm. Here we use a unique combination of kinematic analyses and evolutionary algorithms to determine our robot’s optimal geometry in which its structural topology is represented by Fourier basis functions. Our synthesis method has evolved an optimal XYθz nanopositioner that has stiffness ratios, mechanical bandwidth, workspace and positioning resolutions of 741–869, 123 Hz, 5.8 mm\(\times\)5.8 mm\(\times\)6° and 13 nm\(\times\)14 nm\(\times\)1.3 μrad, respectively. Our XYθz nanopositioner’s workspace to positioning resolutions ratio is 4.9–2.31\(\times\)1011 folds higher than existing similar robots, while its disturbance rejection capability is 1142–2.10\(\times\)1017 folds greater than those with a large workspace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanopositioners are high precision robots that are indispensable across numerous micro/nano-positioning applications1,2,3. In order to achieve high precision, it is essential for these robots to be made compliant so that they can deliver their motions via elastic deformations4,5,6. This is because such unique actuation methods can effectively allow the nanopositioners to eliminate backlash, dry friction and other types of mechanical tolerances7,8,9. By generating motions via elastic deformation, nanopositioners can therefore realize higher precision than other robots which generate motions via traditional mechanisms, stick-slip (friction-inertia) principles, inchworm actuation and ultrasonic methods3,5,9. Of the nanopositioners, those that can translate along their X- and Y-axes, and rotate about the Z-axis are especially important10,11,12,13. Such three degrees-of-freedom robots are generally known as XYθz nanopositioners, and their performance is critical across a vast range of microscopy technologies (e.g., scanning electron microscopes)3,14,15,16,17,18,19, biomedical research (e.g., cell manipulation)20,21,22,23,24 and industrial applications (e.g., micro/nanofabrication processes)10,11,12,13,25,26,27,28.

The performance of XYθz nanopositioners is highly dependent on their stiffness properties27,29,30,31. For instance, it will be ideal to minimize the actuating stiffness along the X- and Y-axes, and about the Z-axis of these nanopositioners13,32. When these actuating stiffness are minimized, the XYθz nanopositioners will be able to produce large deflections with minimal actuation efforts, and this can generally allow them to maximize their workspace31,33. Conversely, it will also be advantageous to maximize the off-axis stiffness of XYθz nanopositioners so that they can more effectively reject external wrenches in those axes13,27. Because these wrenches are undesirable inputs to the XYθz nanopositioners, they can be defined as the mechanical disturbances of these robots34. To optimize the overall workspace and disturbance rejection capabilities of XYθz nanopositioners, it is therefore highly desirable to maximize their stiffness ratios, i.e., the ratios of their off-axis to actuating stiffness35,36. Despite the importance of their stiffness properties, the stiffness ratios of existing XYθz nanopositioners are still limited to 0.5–24811,12,13,16,17,21,24,25,26,27,30,31,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, and it remains a great challenge to further increase them.

The mechanical bandwidth of the XYθz nanopositioners is another critical property that dictates their performance, and this parameter can be approximated by their fundamental natural frequency27,31,56. High bandwidth will be especially beneficial as it can allow the XYθz nanopositioners to realize fast dynamic responses13,27 and achieve fine positioning resolutions more easily (Supplementary Note S1A). However, higher bandwidth requires higher actuating stiffness, and this will in turn reduce the stiffness ratios and workspace of the XYθz nanopositioners13,27,33. For example, an XYθz nanopositioner with a workspace of 1.2 mm \(\times\) 1.2 mm \(\times\) 6° can achieve a bandwidth of 102 Hz27, whereas another XYθz nanopositioner can only achieve a bandwidth of 70 Hz when it can realize a larger workspace of 2.5 mm \(\times\) 2.5 mm \(\times\) 10°13. In general, it is difficult to exceed a mechanical bandwidth of 70 Hz when the XYθz nanopositioners can deflect more than 2 mm, i.e., their mechanical bandwidths are restricted to 20-70 Hz13,26,36,48,49,50,51,53. Existing large workspace XYθz nanopositioners, which can deflect more than 0.5 mm and 1°, can also at most achieve a mechanical bandwidth of 102 Hz13,17,26,27,36,37,48,49,50,51,53. The creation of optimal XYθz nanopositioners that can concurrently maximize their stiffness ratios and mechanical bandwidth remains an open challenge. Therefore, existing XYθz nanopositioners are unable to simultaneously optimize all of their key performance indexes, i.e., their workspace, disturbance rejection capabilities, mechanical bandwidth and positioning resolutions. These key performance indexes will be critical across all the applications that the XYθz nanopositioners are deployed for11,12,13,16,17,21,24,25,26,27,30,31,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55.

Here we use a unique combination of kinematic analyses and evolutionary algorithms to create an optimal XYθz nanopositioner that can maximize its stiffness ratios and mechanical bandwidth. By maximizing these critical robotic parameters, this nanopositioner will therefore be able to fully optimize its workspace, disturbance rejection capabilities, speed and positioning resolution as a whole. Before the evolutionary algorithms are executed, rigid-body replacement techniques are used to identify feasible parallel kinematic configurations for our robot5, i.e., to determine the required number of parallel compliant sub-chains to articulate a rigid end-effector. We have selected a parallel-kinematic configuration for our XYθz nanopositioner because this can allow it to possess superior disturbance rejection capabilities and dynamic response over those that have serial-kinematic configurations8,15. These kinematic analyses are critical in ensuring that our robot can possess the required three degrees-of-freedom motions. Subsequently, the structural topology of the robot’s sub-chains will be represented by Fourier basis functions and the Fourier coefficients of these functions will be optimized via evolutionary algorithms such that the XYθz nanopositioner can maximize its stiffness ratios. A notable advantage of using evolutionary algorithms is that such algorithms have the potential to search for the global optimal solution57. Likewise, a critical feature of our Fourier representation is that it encompasses all possible mathematical functions58. By formulating our evolutionary algorithms via Fourier representations, we can therefore potentially explore all feasible structural topologies for our compliant sub-chains and eventually identify the optimal topology that can far surpass all the existing XYθz nanopositioners. Once the sub-chains’ optimal topology is identified, our evolutionary algorithms will continue to evolve the shape and size of the optimal structural topology of the robot until our XYθz nanopositioner is able to maximize its stiffness ratios and mechanical bandwidth. We remark that our kinematic analyses and evolutionary algorithms are applicable not only to nanopositioners but they may also inspire a new generation of soft robots58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70, sensors71,72,73, adhesives74,75,76, energy harvesters77,78,79,80 and smart actuators58,81,82. This is possible because such soft devices and nanopositioners operate under similar working principles. It is noteworthy that there also exist structures that are optimized via representing their geometries with Fourier functions83. However, such structures are unable to attain multi-degrees-of-freedom motions83 because their optimization formulations lack the critical kinematic analyses that are presented here. As the optimization process of these structures83 is also not solved via global optimization solvers like our evolutionary algorithms, those solutions are also likely a local optima and not global ones. In general, our unique combination of kinematic analyses and evolutionary algorithms based on Fourier topological representation forms a synthesis method for compliant/soft robots that has never been investigated in the literature. By formulating our synthesis method to optimize the stiffness and dynamic properties of XYθz nanopositioners, such investigations are unique in the literature too.

Results

Evolutionary process

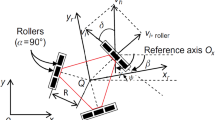

Based on rigid-body replacement techniques, we dictate our XYθz nanopositioner to be a monolithic structure, which has a rigid end-effector articulated by three parallel compliant sub-chains (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Note S1B). To distribute the payload equally among the sub-chains, we have constrained the sub-chains to have identical geometries26,27. Each sub-chain is further constrained to have symmetrical features so that the parasitic motions of the end-effector can be minimized13,26. While the sub-chains are initially arranged in a rotary symmetrical configuration, their orientations with respect to the end-effector can eventually be optimized in the later stages.

A The initial configuration of the proposed XYθz nanopositioner. It adopts a parallel-kinematic configuration whereby its rigid end-effector is articulated by three parallel compliant sub-chains that are arranged in a rotary symmetrical manner. B Topological optimization process for the compliant sub-chains of the XYθz nanopositioner. (i)-(v) show the evolutionary process and the optimal sub-chain topology is identified in (v). C The deformative characteristics of the optimal sub-chain are similar to the kinematics of a 7-bar linkage. Each sub-chain can be actuated via the pin-in-a-slot joint. D Dynamic optimization process for the optimal XYθz nanopositioner. (i)-(iii) show the evolutionary process and the optimal XYθz nanopositioner is illustrated in (iii). E A corresponding prototype that is constructed based on the design in D(iii). The sharp edges of this prototype have been smoothened to remove stress concentrations.

Based on the selected parallel-kinematic configuration, numerical simulations are then conducted to allow computers to generate the optimal structural topology, shape, size and orientation of the compliant sub-chains. During these optimization processes, we assume that our XYθz nanopositioner is made of aluminum (Methods Section), its end-effector is rigid, and each sub-chain is constrained within a footprint of 50 mm \(\times\) 60 mm with two fixed points. The out-of-plane thickness of the sub-chains (t) is also initially set to be 20 mm as this is a typical value reported by existing XYθz nanopositioners13,27. We begin the topological optimization by discretizing the footprint of the sub-chains into a mesh of finite elements (Fig. 1A). In this optimization process, our objective is to determine the optimal state of each finite element – either solid or void. To achieve this goal, we create a level-set function84 by using a 2D spatial Fourier series to generate different function values across a sub-chain. If the function value is positive or zero at the center of a finite element, that element will be assigned to become solid. Conversely, that finite element will be void if the function value is negative. Using such formulations, we can determine the states of all the finite elements in the mesh and generate a corresponding topology for the sub-chains once a given set of Fourier coefficients is specified. Different sub-chain topologies can also be generated by changing the Fourier coefficients. Based on this level-set method, an optimization process is performed to gradually evolve the Fourier coefficients so that we can eventually identify the optimal sub-chain topology, which can maximize the stiffness ratios of the XYθz nanopositioner (Supplementary Note S2A). This optimization process is solved by a genetic algorithm57 within 50 hours (Supplementary Note S2A), and the evolution of the sub-chain topology is illustrated in Fig. 1B. Throughout this evolutionary process, the stiffness properties of our XYθz nanopositioner are repeatedly evaluated by finite element analysis (Supplementary Note S2A). Additional constraints are also used during the optimization process to eliminate infeasible topologies that have disconnected solid components (Supplementary Note S2B). These constraints can also reduce the occurrence of unfavorable checkerboard connections for the generated topologies (Supplementary Note S2B). After the optimal topology is obtained via the optimization process (Fig. 1B(v)), the deformation characteristics of the sub-chains are further analyzed via finite element analysis. These analyses indicate that the deformation characteristics of the sub-chains are similar to the kinematics of a 7-bar linkage (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Note S2C), and thus the optimal topology of the sub-chains can be represented by this linkage configuration. Based on these kinematic insights, we deduce that each sub-chain can potentially be actuated via the pin-in-a-slot joint in Fig. 1C. Please see Supplementary Note S4A on how we can align and mount the actuators on the robot. Before the sub-chains are further optimized, the geometries of these links are made simpler while maintaining their optimal topology (Supplementary Fig. S7E and Supplementary Note S2C). Specifically, this simplification process is performed by analyzing the deformation characteristics of the sub-chains via our finite element analysis in Supplementary Note S2C. Based on these simulations, we identify all the solid elements that produce zero strains when the sub-chains deform and subsequently remove them. This is because these undeformed elements have no effects on the stiffness properties of our robot but their mass contributions will decrease the mechanical bandwidth of our robot. Due to these reasons, our robot will benefit by eliminating these redundant undeformed elements so that its stiffness properties and bandwidth can be further enhanced. From the topological perspective, the configuration of our nanopositioner remains the same after the redundant elements are removed. This is because the topology of the compliant structure refers to its overall connectivity (i.e., the number of holes and their locations)85 and removing the redundant elements still allow the topology of our sub-chains to remain similar to a seven-bar linkage.

Next, we aim to identify the highest stiffness ratios achievable by our XYθz nanopositioner when the shape and size of its links in the sub-chains are further optimized. These obtained stiffness ratios can be used as a guide to select appropriate stiffness constraints for our XYθz nanopositioner in the final dynamic optimization process. To perform this optimization process, the link curvatures in the sub-chains are represented by sine curves and straight lines, and different curvatures can be obtained by changing the parameters in these mathematical representations (Supplementary Note S3A). The link curvatures will be gradually evolved until the stiffness ratios of the XYθz nanopositioner are maximized (Supplementary Note S3A). This entire optimization process is solved by the genetic algorithm within 50 hours where t is set to be 20 mm. The evolutionary process is shown in Supplementary Fig. S9. Once the optimal configuration is obtained, additional simulations are conducted to further analyze the achievable workspace of this design (Supplementary Note S3A and Supplementary Note S4B). These workspace analyses are conducted based on the robot’s fatigue stress (approximated to be 159 MPa27) as well as its actuation capabilities. Since the orientation of the sub-chains is critical for such analyses, a series of configurations with different sub-chain orientations have been evaluated for our XYθz nanopositioner (Supplementary Note S3A). These analyses suggest that the XYθz nanopositioner can reach its maximum workspace even when we use three linear actuators that can only output 12 N each. Because there exist much stronger actuators that can produce 60–110 N, this implies that the actuating stiffness of our XYθz nanopositioner is unnecessarily low for realizing its full actuation capacity. Therefore, it will be possible to enlarge our robot’s t, and yet allow its actuating stiffness to be sufficiently low for full actuation capacity when stronger actuators are selected. It is highly advantageous to have a large t for the XYθz nanopositioner as this can further enhance its stiffness ratios. This is because the off-axis stiffness of the XYθz nanopositioner is proportional to t3 while its actuating stiffness is only linearly proportional to t.15 Based on these workspace analyses and other manufacturing constraints (Supplementary Note S3A), we determine that t can be increased to 90 mm for our XYθz nanopositioner and this robot will be able to realize its maximum workspace with three actuators that can each output 57 N. Assuming that the end-effector is rigid, the mean translational and rotational stiffness ratios of our XYθz nanopositioner in such a configuration are predicted in the simulations to be 2486 and 2330, respectively (Supplementary Note S3A). As the dynamic properties of the XYθz nanopositioner have not been optimized yet, this robot’s mechanical bandwidth is predicted in the simulations to be only ~70 Hz for this configuration (Supplementary Note S3A).

Using the stiffness ratios obtained in the previous optimization process as a guide, we proceed to the final dynamic optimization for our XYθz nanopositioner. Since the stiffness ratios are expected to decrease when the mechanical bandwidth of the XYθz nanopositioner is increased, we have constrained the stiffness ratios of our robot to be at least 1000 (assuming that the end-effector is rigid). These constraints are known to be viable since the previous optimization process had already shown that higher stiffness ratios can be obtained for our robot. In this final optimization process, we start with the optimal topology, and gradually evolve the curvature of the links in the sub-chains, t, and the sub-chains’ orientation until the mechanical bandwidth of our XYθz nanopositioner is maximized (Supplementary Note S3B). The range of t is constrained to be within 20-90 mm during this optimization process. Similar to the previous optimization process, the link curvatures in the sub-chains are again represented by sine curves and straight lines. During the optimization processes, the stiffness and dynamic properties of the XYθz nanopositioner as well as its workspace are repeatedly evaluated. This final optimization process is eventually solved by the genetic algorithm within 40 hours (Supplementary Note S3B). The evolution of the robot is illustrated in Fig. 1D, and the optimal XYθz nanopositioner has a final t value of 90 mm (Fig. 1D(iii)). While we have previously assumed the end-effector of the optimal XYθz nanopositioner to be rigid in the optimization processes so as to reduce computational time, it is noteworthy that this component has a finite stiffness in practice too. By accounting for the stiffness of the robot’s end-effector, our optimal XYθz nanopositioner is predicted by finite element analysis to have a mean translational stiffness ratio of 756, a mean rotational stiffness ratio of 974 and a mechanical bandwidth of 128 Hz (Supplementary Note S3B). Based on fatigue stress analysis and the actuation capabilities of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner, finite element analysis also predicted that the maximum achievable workspace of our robot is 5.8 mm \(\times\) 5.8 mm \(\times\) 6° when we use three actuators that can each output 80 N (Supplementary Note S3B). Our simulations, however, are unable to predict the achievable positioning resolution of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner as its capabilities to reject noises can only be evaluated via experimental means.

Experimental results

Based on the optimal XYθz nanopositioner in Fig. 1D(iii), a corresponding prototype with a t value of 90 mm and smoothened edges was constructed (Fig. 1E, and Methods Section). The performance of this prototype was evaluated via extensive characterizations. To examine the actuating stiffness of the prototype, we measured the required forces/torques to translate/rotate its end-effector to different linear/angular displacements (Supplementary Note S5A). In these experiments, we applied the X- and Y-axes forces, and Z-axis torques directly at the prototype’s end-effector (Supplementary Note S5A). The obtained experimental data were plotted in Fig. 2A(i)-(iii), where the x- and y-axes of the plots represented the linear/angular displacements of the end-effector and their corresponding applied forces/torques, respectively. Each data point in these experiments was evaluated with ten trials and the gradient of the best fit line in these plots represented the actuating stiffness of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner. The actuating stiffness along the X- and Y-axes were evaluated to be 3.86 \(\times\) 104 N m−1 and 3.77 \(\times\) 104 N m−1, respectively. The actuating stiffness about the Z-axis was also determined as 47.5 Nm rad−1. Similar experiments had also been conducted to determine the off-axis stiffness of the prototype (Supplementary Note S5B). In these experiments, each data point was evaluated with ten trials (Fig. 2B(i)-(iii)). Based on the gradient of the best fit lines in Fig. 2B(i)-(iii), the off-axis stiffness along the Z-axis was evaluated to be 2.86 \(\times\) 107 N m−1, while the off-axis stiffness about the X- and Y-axes were both determined to be 4.13 \(\times\) 104 Nm rad−1. Hence, the translational stiffness ratios of the prototype could be computed as (2.86 \(\times\) 107)/(3.86 \(\times\) 104) \(=\) 741 and (2.86 \(\times\) 107)/(3.77 \(\times\) 104) \(=\) 759. The mean translational stiffness ratio of our prototype could therefore be evaluated as 750. For the rotational stiffness ratios of the prototype, both of their values could be evaluated as (4.13 \(\times\) 104)/47.5 \(=\) 869, implying that the mean rotational stiffness ratio was also 869. These stiffness ratios showed an advancement over existing XYθz nanopositioners, which had stiffness ratios that were limited to 0.5–24811,12,13,16,17,21,24,25,26,27,30,31,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55. This implied that our optimal XYθz nanopositioner was much superior to existing XYθz nanopositioners in terms of its overall workspace and disturbance rejection capabilities13,27. Based on the off-axes stiffness of our robot (Fig. 2B), we computed that it would only deflect 35 nm along the Z-axis, and 24.2 nrad about the X- and Y-axes when corresponding unit wrenches of disturbances were applied in these axes. By multiplying all of these normalized deflections together, we could quantify the net off-axes compliance of our robot to be 35 nm N−1 \(\times\) 24.2 nrad N−1 m−1 \(\times\) 24.2 nrad N−1 m−1. Notably, the net off-axes compliance of our robot was 1,142–2.10\(\times\)1017 folds smaller than existing XYθz nanopositioners that could deflect more than 0.5 mm or 1°13,17,26,27,36,37,48,49,50,51,53,55 (Supplementary Table S1). This implied that the disturbance rejection capabilities of our robot were also 1,142–2.10\(\times\)1017 folds greater than these large workspace nanopositioners13,17,26,27,36,37,48,49,50,51,53,55.

A Evaluation of the prototype’s actuating stiffness. The plots in (i), (ii) and (iii) represented the data required for analyzing the prototype’s actuating stiffness along the X- and Y-axes, and about the Z-axis, respectively. Each data point in these plots was evaluated with ten trials, and the centroid and error bar of each point represented its corresponding mean and standard deviation. The gradient of the best fit line in these plots represented the corresponding actuating stiffness of the prototype. The actuating stiffness in (i), (ii) and (iii) were evaluated to be 3.86 \(\times\) 104 N m−1, 3.77 \(\times\) 104 N m−1 and 47.5 Nm rad−1, respectively. B Evaluation of the prototype’s off-axis stiffness. The plots in (i), (ii) and (iii) represented the data required for analyzing the prototype’s off-axis stiffness along the Z-axis, and about the X- and Y-axes, respectively. Each data point in these plots was evaluated with ten trials, and the centroid and error bar of each point represented its corresponding mean and standard deviation. The gradient of the best fit line in these plots represented the reciprocal of the prototype’s off-axis stiffness. The off-axis stiffness in (i), (ii) and (iii) could therefore be evaluated as 2.86 \(\times\) 107 N m−1, 4.13 \(\times\) 104 Nm rad−1 and 4.13 \(\times\) 104 Nm rad−1, respectively. C The frequency response of the prototype’s three lowest mode shapes. The Bode plots in (i), (ii) and (iii) represented the data required for analyzing the prototype’s mode shapes along the Y- and X-axes, and about the Z-axis, respectively. Each plot was obtained based on the average of ten impulse tests. Using these Bode plots, the resonance frequencies in (i) and (ii) could be identified as 123 Hz and 124 Hz, respectively. There were two resonance frequencies in (iii), and their values were 123 Hz and 223 Hz.

By using impulse tests (Supplementary Note S5C), we were also able to characterize the dynamic response of the prototype along its actuating Y- and X-axes (Fig. 2C(i)-(ii)), and about the actuating Z-axis (Fig. 2C(iii)). All of these impulse tests were repeated 10 times, and their average dynamic responses were represented in the form of Bode plots. These dynamic responses revealed the frequency response of the prototype’s three lowest mode shapes. The fundamental mode shape of the XYθz nanopositioner was along the actuating X- or Y-axes, and therefore the mechanical bandwidth of the prototype could be approximated to be 123–124 Hz by the resonance frequencies in Fig. 2C(i)-(ii). While the fundamental resonance frequency of the system was expected to be lower than its fundamental natural frequency, their differences would be small when the damping effects were negligible34. Since the resonance peaks in Fig. 2C(i)-(ii) were sharp, this suggested that the damping effects in these experiments were indeed small and therefore the obtained resonance frequency could be a good approximation for the XYθz nanopositioner’s mechanical bandwidth. In Fig. 2C(iii), there were two resonant peaks (123 Hz and 223 Hz) because the impulse torque to the system was introduced via an X-axis impulse force, which had an effective moment arm from the end-effector. Hence, the Bode plot in Fig. 2C(iii) had superimposed the frequency response of two mode shapes: (i) along the X-axis and (ii) about the Z-axis. Specifically, the first and second peaks in Fig. 2C(iii) represented the resonance frequencies of the translational X- and rotational Z-axes mode shapes, respectively. To support this hypothesis, additional impulse tests had been carried out (Supplementary Note S5D). In these experiments, we observed that when the moment arm between the end-effector and the impulse force was increased, the second peak became more prominent while the effects of the first peak remained relatively unchanged (Supplementary Note S5D and Supplementary Figs. S19, 20). Such observations supported the view that the second resonant peak in Fig. 2C(iii) was indeed induced by the prototype’s mode shape about the Z-axis because increasing the moment arm would only increase the magnitude of the impulse torque and enhance the effects of this rotational mode shape. Another supporting observation that the first peak in Fig. 2C(iii) represented the resonance of the translational X-axis mode shape was that this frequency almost coincided with the resonance frequency in Fig. 2C(ii). Because the predicted workspace of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner was large (5.8 mm \(\times\) 5.8 mm \(\times\) 6°), its high mechanical bandwidth of 123 Hz showed improvements over existing XYθz nanopositioners which could deflect more than 2 mm13,26,36,48,49,50,51,53. In general, such existing large workspace XYθz nanopositioners could achieve a mechanical bandwidth of 20–70 Hz13,26,36,48,49,50,51,53. Likewise, the optimal XYθz nanopositioner also demonstrated superior dynamic responses over all existing large workspace XYθz nanopositioners that could deflect more than 0.5 mm and 1° because their highest reported bandwidth was 102 Hz13,17,26,27,36,37,48,49,50,51,53. By having a higher mechanical bandwidth, our proposed robot could therefore realize higher speed than existing XYθz nanopositioners with large workspaces26,51.

In our experiments, we also validated that our XYθz nanopositioner could indeed realize its predicted workspace of 5.8 mm \(\times\) 5.8 mm \(\times\) 6° (Fig. 3, Supplementary Movie S1, and Methods Section). Because the deformation of our XYθz nanopositioner is always within its fatigue stress limit and there are no bifurcation points in its workspace, our robot does not have singularities across its entire workspace. Compared to the existing XYθz nanopositioners11,12,13,16,17,21,24,25,26,27,30,31,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, the workspace of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner was one of the largest in the literature (Supplementary Table S1). Overall, the experiments agreed with the simulation results, and their deviations were less than 11% (Supplementary Table S6). These minor errors in the experiments could be due to fabrication errors. Furthermore, we also evaluated that this optimal nanopositioner could achieve positioning resolutions of 13 nm \(\times\) 14 nm \(\times\) 1.3 μrad (Fig. 4A, and Methods Section). The positioning resolution of each axis was defined as the minimum step displacement that the end-effector could track, in which the noise of two such adjacent steps would not have notable overlaps. In general, the noise detected by our sensors in Fig. 4A was induced by external vibrations from the environment3,10,86,87. Our nanopositioner could achieve such fine resolutions because its high mechanical bandwidth had enabled us to easily design effective PID controllers to reject such noise under closed-loop position control schemes (Supplementary Note S1A). As the attained positioning resolutions were among the finest compared to all the existing XYθz nanopositioners that had large workspace (Supplementary Table S1), this indicated that our robot’s sensitivity to external vibrations was low. To further quantify the performance of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner, we defined a dimensionless index that computed the ratio of the nanopositioner’s workspace to positioning resolutions. This ratio could be calculated as (5.8 mm \(\times\) 5.8 mm \(\times\) 6°)/(13 nm \(\times\) 14 nm \(\times\) 1.3 µrad) \(=\) 1.49 \(\times\) 1016 for our optimal XYθz nanopositioner (after converting all the components in the workspace and positioning resolution to SI units). Because this ratio was 4.9–2.31\(\times\)1011 folds higher than those reported by existing similar devices11,12,13,16,17,21,24,25,26,27,30,31,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, this implies that the performance of our high precision robot was much superior over existing XYθz nanopositioners in these aspects (Supplementary Table S1).

These experiments were conducted based on an open-loop control scheme. A Evaluation of the maximum X-axis translation achievable by the prototype. (i) and (ii) represented the extreme displacements of the prototype’s end-effector along the X-axis. B Evaluation of the maximum Y-axis translation achievable by the prototype. (i) and (ii) represented the extreme displacements of the prototype’s end-effector along the Y-axis. C Evaluation of the maximum Z-axis rotation achievable by the prototype. (i) and (ii) showed the extreme Z-axis angular displacements of the prototype.

A Positioning resolutions of the XYθz nanopositioner. (i) showed that the robot was able to track a series of step responses that continuously increment or decrement 13 nm along the X-axis. Likewise, (ii) and (iii) showed that the robot could track a series of step responses that continuously increment or decrement 14 nm along the Y-axis and 1.3 µrad about the Z-axis, respectively. B The end-effector of the robot was commanded to trace an “NTU” trajectory across different length scales in the XY plane. The letters “N”, “T” and “U” were in millimeters, micrometers and nanometers, respectively. When the robot was tracing the “N” letter, its end-effector’s orientation was rotated to –2° about the Z-axis. The orientation of the end-effector was rotated to +2° about the Z-axis when the robot was tracing the “T” and “U” letters. On the extreme right, the zoom-in of the “U” letter indicated the robot’s positioning resolution in this trajectory (~14 nm).

To further highlight the capabilities of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner, we had commanded its end-effector to trace an “NTU” trajectory across different length scales in the XY plane, where “NTU” represents the acronym of our research institute (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Movie S2, and Methods Section). The prototype’s end-effector was first rotated to \(-\)2° about the Z-axis when it traced out the millimeter-scale “N” letter. Subsequently, the end-effector was rotated to \(+\)2° about the Z-axis as it traced out the “T” letter in microscale and the “U” letter in nanoscale. The positioning resolution of this trajectory was evaluated to be ~14 nm (Fig. 4B). The demonstration in Fig. 4B and Supplementary Movie S2 showed that our optimal XYθz nanopositioner was able to track trajectories across nano- to millimeter length scales (please see the robot’s control scheme in the Methods Section). Of the existing XYθz nanopositioners11,12,13,16,17,21,24,25,26,27,30,31,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, only the robots in refs. 26,51,53 may have the potential to track trajectories across nano- to millimeter length scales. However, as the resolutions of these robots were limited to at least eighty nanometers26,51,53, they could only produce coarse motions in the nanoscale and thus unable to track the “U” letter in our demonstration. The abilities of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner would be especially favorable for high precision applications that require large workspace and fine resolutions.

Discussion

The proposed synthesis method and optimal XYθ z nanopositioner

Due to the conflicting nature between the stiffness ratios and bandwidth of XYθz nanopositioners, comparisons between different XYθz nanopositioners must be done in a holistic manner. As an example of such comparisons, we will discuss about the performance of our XYθz nanopositioner with Lum et al.’s robot because that robot has the highest achievable bandwidth among all the existing XYθz nanopositioners that can deflect more than 2 mm13. Because our XYθz nanopositioner has achieved stiffness ratios of 741–869 and bandwidth of 123 Hz, it is superior to the robot of Lum et al.13, which has stiffness ratios and bandwidth of 238-248 and 70 Hz, respectively. As a result, our XYθz nanopositioner has a much larger workspace (5.8 mm × 5.8 mm × 6°) and smaller net off-axes compliance (0.035 μm N−1 × 0.0242 μrad N−1 m−1 × 0.0242 μrad N−1 m−1 than Lum et al.’s robot (workspace: 2.5 mm × 2.5 mm × 10°, net off-axes compliance: 0.337 μm N−1 × 0.7 μrad N−1 m−1 × 0.7 μrad N−1 m−1)13. By having a much smaller net off-axes compliance, our proposed XYθz nanopositioner will be much superior in rejecting disturbances than Lum et al.’s robot13. Since the bandwidth of our XYθz nanopositioner is higher than that robot13, it can also realize faster dynamic responses13,27 and achieve finer positioning resolutions more easily (note: Lum et al.’s robot did not evaluate their positioning resolutions13). To have a holistic comparison between our robot and all the existing, macro-scale XYθz nanopositioners, we have summarized their key performance indexes in Supplementary Table S1.

In general, our optimal robot has greater disturbance rejection capabilities than most small workspace XYθz nanopositioners too11,12,16,21,24,30,31,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,47,52,54 (Supplementary Table S1). Although there exist XYθz nanopositioners that have lower net off-axes compliance than our optimal robot25,45,46 (Supplementary Table S1), their high stiffness configurations have also severely restricted their workspace. Specifically, they can at most realize a workspace of 123 μm \(\times\) 109 μm \(\times\) 0.0392°25,45,46, which is much smaller compared to those of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner (5.8 mm \(\times\) 5.8 mm \(\times\) 6°).

The topology of our XYθz nanopositioner has three sub-chains, each with a 7-bar linkage configuration. This topology is distinctly different from all the existing XYθz nanopositioners that have serial kinematic configurations37 as well as those with parallel kinematic configurations but with different number of sub-chains17,38,39,44,53. Furthermore, our topology is also distinctly different from all the existing XYθz nanopositioners that have three parallel sub-chains because they possess 3-legged prismatic-prismatic-revolute (3PPR)13,26,27,36,48,49,50,51, 3PRR25,30,42,45,46 or 3RRR11,12,16,21,24,31,40,41,43,47,52,54,55 configurations. Since the topology of a structure defines its overall connectivity85 and that the topology of our XYθz nanopositioner is unique, the resulting structure and shape of our nanopositioner must also be distinctly different from that of existing XYθz nanopositioners.

Although increasing the XYθz nanopositioners’ t can increase their stiffness ratios, this will also increase their actuating stiffness linearly15. Assuming that the actuation capabilities of the actuators remain the same after the nanopositioners’ t is increased, the workspace of these XYθz nanopositioners is expected to reduce linearly15. As such, the desired workspace that needs to be achieved imposes a limit on how much existing XYθz nanopositioners’ t can be increased. Hence, existing XYθz nanopositioners’ t cannot exceed 92.5 mm11,12,13,16,17,21,24,25,26,27,30,31,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55. Furthermore, solely increasing t does not guarantee that the XYθz nanopositioners can possess high stiffness ratios. For example, the XYθz nanopositioner of Navale et al.52 has the largest t among all the existing similar devices (92.5 mm) but it can only achieve stiffness ratios of 3.2–3.4 (Supplementary Table S1). In this study, because we have discovered the optimal topology and shape of our XYθz nanopositioner, we can realize higher stiffness ratios than all existing similar devices. In addition, we can also endow our robot with a large t of 90 mm while still allowing it to realize a very large workspace. The presented optimization processes are therefore critical steps to determine an optimal design for XYθz nanopositioners.

The size of our nanopositioner is sufficiently compact across a wide range of applications. In terms of size, the XYθz nanopositioners’ t is much less of a concern than their footprint area in the XY plane. This is because as long as the wafers, petri dishes or other apparatus can be placed on top or below of the nanopositioners’ end-effector along the Z-axis10,11,20,21,25,28,37, their thickness dimension will not prohibit their practicality. The footprint area of our robot can be computed as 9438 mm2 when we consider the area occupied by its three sub-chains (each has an area of 50 mm × 50 mm) and end-effector (1938 mm2). This footprint area is approximately two-fold smaller than most of the commercial XYθz nanopositioners from Physik Instrumente88 and SYMC89 since their footprint area is 22,500 mm2 (Table 1). Because these commercial products have been used across a wide range of applications pertaining to metrology, lithography, micromachining, nanoaligment and many other areas88,89, this implies that the size of our nanopositioner is sufficiently compact for these applications too. In addition, our nanopositioner has a smaller footprint area than a wide range of XYθz nanopositioners that have been deployed for various industrial applications10,11,25,28 and microscopy technologies21,37 (Table 1). While our footprint area is larger than Huang et al.’s robot20, which is deployed for microinjections, there are no fundamental size concerns that prohibit our nanopositioner from replacing thatrobot20. This is because many of the apparatus in Huang et al.’s robot20, like the micropipette and petri dish, can be placed on top of our nanopositioners’ end-effector (along the Z-axis). Our nanopositioner is also sufficiently compact to be compatible with general microscopes (Table 1), and this is a critical criterion for microinjection applications20. It will be beneficial to replace Huang et al.’s robot20 with our nanopositioner because that robot produces its motions via a traditional mechanism, which is actuated by DC brushless motors. In comparison, as our XYθz nanopositioner uses elastic deformation to realize its motions, it can achieve higher precision than Huang et al.’s robot20. Since microinjection applications generally involved manipulating fragile cells, having high precision/repeatability in motions will be very critical for such applications20.

Instead of yield stress, here we use fatigue or endurance stress as a requirement to determine the achievable workspace of XYθz nanopositioners because such stress constraints will be much more conservative15. Since the maximum von Mises stress of our prototype did not exceed the approximated fatigue stress at all times (Supplementary Note S3B and Supplementary Note S4B), this implies that the prototype will be able to deliver 108 cycles of precise motions15 as long as it is operating within the reported workspace of 5.8 mm \(\times\) 5.8 mm \(\times\) 6°. Based on finite element analysis, our robot will not buckle upon actuation too (Supplementary Note S4B). Such predictions agree with our experimental results as we did not observe buckling during actuation. In this first study, we did not check for buckling as a potential failure mode during the synthesis process and we wish to do so in our future work. However, when buckling is considered during the synthesis process, we remark that the computation time in our optimization processes will inevitably increase.

A potential method to further increase the workspace of our XYθz nanopositioner is to construct it with more durable materials such as steel or titanium, and this can potentially be explored in the future. Titanium is an especially promising candidate as this material also has a very low density90, implying that the prototype can be made lighter to achieve higher mechanical bandwidth. For this first study, we have fabricated our prototype based on aluminum because it is a material that can be easily machined.

Under closed-loop position control scheme, the forward-loop bandwidth of XYθz nanopositioners is dependent on the bandwidth of their actuators and mechanical structure34. In general, the formers’ bandwidth is much higher than those of the latter, especially for nanopositioners with a large workspace. Due to this reason, the mechanical bandwidth of the XYθz nanopositioners will dictate the upper bound of the forward-loop bandwidth and hence this parameter is much more critical than the actuators’ bandwidth. The typical bandwidth of the actuators is in the range of 103–106 Hz91,92,93, while the highest mechanical bandwidth of XYθz nanopositioners with large workspace is 123 Hz, i.e., our nanopositioner (Supplementary Table S1). In our configuration, our voice coil actuators (LVCM-051-064-03 @ Moticont) have a bandwidth of 3,615 Hz and they are also much higher than the mechanical bandwidth of our nanopositioner. For the positioning resolution experiments and “NTU” trajectory showcase, we have implemented closed-loop position control on our nanopositioner according to its mode shapes. It is highly advantageous to implement such mode shape control because this can allow us to fully decouple the motions of the prototype’s end-effector according to its actuating axes51. As the first study, we only use simple PID controllers for such closed-loop control. Therefore, it may be possible to obtain even finer resolutions for our prototype if more sophisticated controllers such as model predictive controllers94 can be adopted in the future. It is noteworthy that the actual positioning resolutions of an XYθz nanopositioner are usually much coarser than their theoretical counterparts88,89. Their theoretical positioning resolutions can be computed by excluding the noise induced from the environment. These theoretical positioning resolutions are based on either the positioning resolutions of the robots’ metrology system or the minimum displacements achievable by the actuators’ force resolution. Of these two positioning resolutions, whichever is coarser will dictate the robots’ theoretical positioning resolutions. In our case, the positioning resolutions of our metrology system are coarser than those derived via the force resolution of our actuators (Supplementary Note S4B). Hence, this implies that the theoretical positioning resolutions of our XYθz nanopositioner are 0\(.1\,{{{\rm{nm}}}}\,\times \,0.1\,{{{\rm{nm}}}}\,\times \,9.70\,{{{\rm{\mu }}}}{{{\rm{rad}}}}\) (Methods Section).

While the proposed XYθz nanopositioner shows great promise, its current metrology setup is relatively preliminary (Methods Section), and it can be improved in various aspects. For instance, the current metrology system uses plane mirrors for its laser interferometer systems and this has limited the range in which we can implement precise orientation control for our XYθz nanopositioner. A potential solution that can mitigate this limitation is to replace the plane mirrors with retroreflectors as this can potentially enable us to apply precise orientation control across the entire workspace26,51. Indeed, we have suggested one of such feasible metrology systems in Supplementary Note S6A and we aim to implement this prospective solution in the future. For this first study of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner, we have also placed the plane mirrors on top of the end-effector for easy characterization purposes (Supplementary Fig. S21). In the future, we also aim to redesign the metrology setup such that the retroreflectors can be placed under the end-effector, allowing the end-effector to be able to carry biological samples21, wafers25, or cell arrays22 for their targeted applications. Once the metrology setup of our XYθz nanopositioner has been redesigned, it can potentially be deployed to advance a wide range of applications pertaining to microscopy technologies3,14,15,16,17,18,19, biomedical research20,21,22,23,24 and industrial processes10,11,12,13,25,26,27,28. For instance, our robot can potentially be automated as an inverted microscope and generate images of its samples with far greater range, finer resolution, and at greater speeds than those possible now (Supplementary Note S6B(I)). Likewise, biologists could also use our robot to increase the success rate of cell microinjections with much higher throughput (Supplementary Note S6B(II)). Our optimal XYθz nanopositioner also has great prospects in enhancing nano-imprinting applications, allowing such processes to be much more accurate as well as to enable the nanofeatures on their wafers to be far more refined while achieving a much higher throughput (Supplementary Note S6B(III)). On a similar note, our optimal XYθz nanopositioner can potentially also handle larger wafers, produce more refined nanofeatures, and increase the fabrication throughout for integrated circuits (Supplementary Note S6B(III)). Although we have only highlighted the benefits of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner with selected examples, similar arguments can be made across a vast range of analogous applications in these related areas. Our optimal XYθz nanopositioner also has the potential to enable high-precision applications that were previously unattainable. However, it is beyond the scope of this work to investigate such applications and we aim to explore this possibility in our future work.

While our XYθz nanopositioner’s positioning resolutions did not achieve sub-nanometer resolutions, it is feasible to create another version of it that can do so. To create such a robot, we must relax the constraint on the stiffness ratios during the third optimization process in our synthesis method. By reducing the requirements on the robot’s stiffness ratios, our robot can obtain higher actuating stiffness which will increase its mechanical bandwidth. When it has a higher mechanical bandwidth, our robot will be easier to achieve much finer positioning resolutions (Supplementary Note S1A), potentially in the sub-nanometer range. We aim to explore such investigations in the future.

In general, topological optimization problems are formulated in such a way that their solutions are independent of the finite element mesh84,85,95. However, such practices cannot be applied here because the performance of our XYθz nanopositioner is found to be highly dependent on the size of its compliant components, and thinner and longer components in the sub-chains can generally make the nanopositioner much more compliant. Due to this observation, it is therefore essential to perform additional shape and size optimizations after the optimal structural topology of the sub-chains is identified. Moving forward, we will explore using splines to represent the curvatures of the linkages in the sub-chains as such formulations can potentially expand the search space during the shape and size optimization processes96,97.

A notable advantage of using a genetic algorithm is that this search-and-find solver has higher chances of identifying the global optimal solution compared to gradient-based methods57. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that there also exist other global optimization solvers such as particle swarm98 and ant colony99 algorithms that can potentially achieve the same purpose. In the future, we aim to explore the feasibility of using such global solvers for our optimization processes. To reduce computational time, we have neglected the nanopositioner’s end-effector stiffness during the optimization processes. In order to achieve more accurate simulations in the evolutionary processes, we aim to fully account for such parameters in the future with high performance computing.

Applicability of our synthesis method for other soft, deformable devices

As this is the first study of our proposed design methodology, we have focused on the full synthesis process and characterization of our presented XYθz nanopositioner. It is notable that our centimeter-scale XYθz nanopositioner is designed for a vast range of real-world applications pertaining to microscopy technologies3,14,15,16,17,18,19, biomedical research20,21,22,23,24 and industrial applications10,11,12,13,25,26,27,28. This is because it is designed to be able to carry wafers, petri dishes and other apparatus, which is a critical requirement to deploy our nanopositioner. Our presented synthesis method, however, has great potential to create other types of nanopositioners with high performances too. For example, we aim to investigate the feasibility of using our unique synthesis method to create XY and XYZ nanopositioners that can be deployed for scanning probe microscopy like atomic force microscopy (AFM)86,100,101,102,103 and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM)104,105,106 in the future. Because such applications require sub-nanometer resolutions86,103,104,105, it is necessary for such nanopositioners to have a high mechanical bandwidth so that they can reject environmental noise more effectively under closed-loop position control schemes (Supplementary Note S1A). However, to attain high mechanical bandwidth, these nanopositioners may have to compromise on their workspace13,27,33. The tradeoff between their mechanical bandwidth and workspace is therefore a critical design consideration for such nanopositioners in the future. Similarly, our design methodology shows great promise in synthesizing optimal XYZθz nanopositioners that are used for nano-scratching, which is a type of micro/nano manufacturing process that can synthesize graphene-based sensors, quantum dots, and nanofluidic channels107,108,109,110,111,112. As our design methodology can concurrently optimize the stiffness and dynamic properties of the XYZθz nanopositioners, it has great potential to endow such robots with larger workspace, finer positioning resolutions, and greater speed and disturbance rejection capabilities107,108,109,110,111,112. Consequently, such optimal robots would have great potential to augment nano-scratching processes by increasing their allowable workpiece sizes, achieve finer manufacturing features at higher speeds and reduce their overall manufacturing errors107,108,109,110,111,112. Using similar deductions, our design methodology also shows great prospects in synthesizing optimal θxθyZ nanopositioners with higher performances than existing similar devices. As our design methodology can generally optimize the stiffness and dynamic properties of nanopositioners, it has great potential to enhance the workspace, disturbance rejection capabilities, speed and positioning resolutions of θxθyZ nanopositioners too113,114. In general, θxθyZ nanopositioners can be used together with XYθz nanopositioners to execute nano-imprinting fabrication processes (Supplementary Note S6B(III))113,114. When the performance θxθyZ nanopositioners are optimized, they can likewise handle larger workpieces, complete their nano-imprinting processes at higher speeds and with finer manufacturing features and less fabrication errors (Supplementary Note S6B(III))113,114.

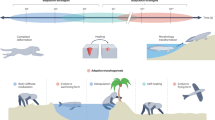

The proposed synthesis method can potentially also inspire a new generation of soft robots58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70, sensors71,72,73, adhesives74,75,76, energy harvesters77,78,79,80, and smart actuators81,82 that are more competent than those available now. As an example, our synthesis method can potentially inspire roboticists to create small-scale soft robots with multiple parallel appendages, which can enable dexterous locomotive gaits (Supplementary Note S6C(I)). It can also inspire optimal grippers that can use their soft fingers to grasp a much wider range of objects with far higher payload than those achievable by existing similar devices (Supplementary Note S6C(I)). Moreover, our presented synthesis method can potentially create optimal untethered microgrippers, which are magnetically-actuated, to concurrently realize dexterous locomotion and robust grasping performances with their soft appendages (Supplementary Note S6C(I))59,66,67. It may also generate unique configurations of flapping wing robots such that these centimeter-scale soft robots can realize aerial gaits which far surpass those available now (Supplementary Note S6C(I))68,69,70. In general, soft robots are created by hyperelastic polymers with active compliance115. Although such materials are detrimental for high precision applications due to their inherent hysteresis (material viscosity), their hyperelastic properties are ideal for soft robotic applications that require large deformations. The effects of hysteresis are not accounted for in this first study but they can be investigated in the future when we use our unique synthesis method to construct such soft robots. Using our evolutionary algorithms, materials scientists can potentially also enhance the overall sensitivity, sensing range and bandwidth of their soft tactile sensors as well as to prospectively create synthetic gecko fibers that can generate much higher dry adhesion (Supplementary Note S6C(II)). Computer scientists can potentially use our kinematic analyses and evolutionary algorithms to synthesize piezoelectric energy harvesters, which have higher degrees-of-freedom and that they can harvest energy much more efficiently across a wider spectrum of frequencies (Supplementary Note S6C(III)). Likewise, our synthesis method can pave the way for computer scientists to create higher degrees-of-freedom, dielectric elastomer actuators that can actively produce much larger deformations across a wider spectrum of actuation frequencies than existing similar devices (Supplementary Note S6C(III)).

In summary, we have presented a synthesis method, which is based on a unique combination of kinematic analyses, evolutionary algorithms and Fourier topological representations to automatically generate an optimal XYθz nanopositioner that has ultrahigh performance. As our robot’s topology is unique, the resulting structure and shape of our nanopositioner are therefore distinctly different from that of existing XYθz nanopositioners. A critical feature of this nanopositioner is that it has higher stiffness ratios and mechanical bandwidth than existing similar devices, especially those with a large workspace (Supplementary Table S1). Hence, this XYθz nanopositioner is able to optimize its workspace, disturbance rejection capabilities, speed and positioning resolutions as a whole. For instance, the robot can concurrently achieve a very large workspace of 5.8 mm \(\times\) 5.8 mm \(\times\) 6° and fine positioning resolutions of 13 nm \(\times\) 14 nm \(\times\) 1.3 µrad. The workspace to positioning resolution ratio of our optimal XYθz nanopositioner is 4.9–2.31\(\times\)1011 folds higher than existing similar robots (Supplementary Table S1). Likewise, our optimal XYθz nanopositioner is also 1,142–2.10\(\times\)1017 folds more effective in rejecting mechanical disturbances than those with a large workspace (Supplementary Table S1). We envision that the proposed XYθz nanopositioner will be highly valuable across a vast range of applications pertaining to microscopy technologies3,14,15,16,17,18,19, biomedical research20,21,22,23,24 and industrial applications10,11,12,13,25,26,27,28. Our unique combination of kinematic analyses and evolutionary algorithms may also inspire future soft robots58,59,60,61,62,63, sensors71,72,73, adhesives74,75,76, energy harvesters77,78,79,80 and actuators81,82 to be more competent.

Methods

Fabrication and material properties of the prototype

Before the prototype is constructed, the sharp edges of the optimal design are smoothened to remove stress concentration regions. Wire-EDM techniques are then used for fabricating the prototype, which is made of aluminum-7075. The Young’s modulus and Poisson ratio of this material are reported to be 71 GPa and 0.33, respectively. To articulate the end-effector of the prototype, three voice coil actuators were connected to their respective sub-chains (Supplementary Note S4A). Each of these linear actuators was able to output a continuous force of 85.4 N and achieve a stroke of 12.7 mm. In theory, these actuators would be sufficient for the prototype to realize its desired workspace since the required actuating force predicted by finite element analysis was only 80 N. As the continuous force of an actuator indicates how much force it can generate over an indefinite period of time116,117, this implies that the actuators will not be overheated and they will always be stable as long as our robot operates within its workspace.

Control strategy

During the workspace experiments, the robot was controlled based on open-loop schemes. By using the linear actuators to activate a desired mode shape of our prototype, we could actuate its end-effector to two extreme displacements achievable in each actuating axis, and these motions were repeated four times while being recorded by a camera (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Movie S1). After finding the difference between the extreme displacements of all the actuating axes, we could therefore determine the achievable workspace of our prototype to be 5.8 mm × 5.8 mm × 6°.

When closed-loop position control was implemented for the positioning resolution tests, a metrology system that was based on two laser interferometer systems was set up to provide translational and rotational displacement feedback for the robot (Supplementary Fig. S21). This metrology system consisted of two plane mirrors, a single-beam interferometer (RENISHAW RLD 10-A3P, translational resolution: 0.8 nm, sampling rate: 25 MHz) and a triple-beam plane-mirror interferometer (SIOS SP 2000-TR, translational resolution: 0.1 nm, rotational resolution: 0.002 arcsec, sampling rate: 40 MHz). For easy characterization purposes, the plane mirrors were mounted on the end-effector of the prototype. The single-beam interferometer and one of the plane mirrors provided the displacement feedback along the Y-axis for the robot (Supplementary Fig. S21). On the other hand, the robot’s displacement feedback along the X-axis and about the Z-axis were provided by the triple-beam interferometer and the other plane mirror (Supplementary Fig. S21). Based on the plane mirror configuration, the achievable range of feedback about the Z-axis was ±1.5 arcmin for the robot. In the future, we may also explore using fiber-brag-gratings (FBG) displacement sensors for our robot118,119. Although FBG are contact-based displacement sensors118,119, their sub-picometer resolution can be beneficial for high-precision applications that require impedance control. Similarly, we can potentially explore using pattern-based visual measurements for our robot in the future since they can also provide nanometer position feedback120,121.

Characterization of positioning resolutions

To evaluate the prototype’s positioning resolution along the X-axis, the end-effector of the prototype was commanded to track a series of step responses that continuously increment or decrement 13 nm along this axis (Fig. 4A(i)). Likewise, the prototype’s positioning resolutions along the Y-axis and about the Z-axis were characterized by commanding its end-effector to track a series of step responses that continuously increment or decrement 14 nm along the Y-axis and 1.3 µrad about the Z-axis, respectively (Fig. 4A(ii)-(iii)). Although the prototype could achieve a 2% settling time of 0.02 s, the duration between each step change in these experiments was specified to be 2 s to ensure that there was sufficient time to observe the prototype’s noise rejection capabilities.

In the “NTU” trajectory showcase, the millimeter-scale “N” letter was traced out by the robot based on an open-loop control scheme and this motion was recorded by a camera (Supplementary Fig. S21 and Supplementary Movie S2). When the robot was tracing the micro- and nanoscale letters, it implemented a closed-loop position control scheme based on the feedback obtained by the aforementioned metrology system (Supplementary Fig. S21). A closed-loop control scheme could not be executed for the entire trajectory because the robot’s end-effector had to be rotated from \(-\)2° to \(+\)2° about the Z-axis when it transited from the millimeter-scale “N” letter to the microscale “T” letter. Such rotations were too large for our current metrology system to measure since it only possessed a simple plane mirror configuration. Indeed, our metrology system had to be rotated by +2° about the Z-axis in this experiment so that the displacement of the end-effector could be measured when the robot was tracing out the microscale “T” letter and the nanoscale “U” letter (Supplementary Fig. S22).

Data availability

All the data in this study is reported in the paper. Additional data may be requested from the corresponding author.

References

McClintock, H., Temel, F. Z., Doshi, N., Koh, J.-s & Wood, R. J. The milliDelta: A high-bandwidth, high-precision, millimeter-scale Delta robot. Sci. Robot. 3, eaar3018 (2018).

Eigler, D. M. & Schweizer, E. K. Positioning single atoms with a scanning tunnelling microscope. Nature 344, 524–526 (1990).

Ru, C., Liu, X. & Sun, Y. Nanopositioning Technologies: Fundamentals and Applications. (Springer, 2016).

Song, Y., Panas, R. M., Chizari, S., Shaw, L. A. & Jackson, J. A. et al. Additively manufacturable micro-mechanical logic gates. Nat. Commun. 10, 882 (2019).

Howell, L. L. Compliant mechanisms. (Wiley, 2001).

Teo, T. J., Yang, G. & Chen, I.-M. A large deflection and high payload flexure-based parallel manipulator for UV nanoimprint lithography: Part I. Modeling and analyses. Precis. Eng. 38, 861–871 (2014).

Suzuki, H. & Wood, R. J. Origami-inspired miniature manipulator for teleoperated microsurgery. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 437–446 (2020).

Wu, Z. & Xu, Q. Survey oN Recent Designs Of Compliant Micro-/nano-positioning Stages. Actuators 7, 5 (2018).

Smith, S. T. Flexures: elements of elastic mechanisms. (CRC Press, 2000).

Lee, C.-W. & Kim, S.-W. An ultraprecision stage for alignment of wafers in advanced microlithography. Precis. Eng. 21, 113–122 (1997).

Ryu, J. W., Gweon, D.-G. & Moon, K. S. Optimal design of a flexure hinge based XYφ wafer stage. Precis. Eng. 21, 18–28 (1997).

Yi, B.-J., Chung, G. B., Na, H. Y., Kim, W. K. & Suh, I. H. Design and experiment of a 3-dof parallel micromechanism utilizing flexure hinges. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 19, 604–612 (2003).

Lum, G. Z. et al. An XYθzflexure mechanism with optimal stiffness properties. in IEEE International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics, 1103–1110 (2017).

Bertazzo, S. et al. Nano-analytical electron microscopy reveals fundamental insights into human cardiovascular tissue calcification. Nat. Mater. 12, 576–583 (2013).

Teo, T. J., Yang, G. & Chen, I.-M. Compliant manipulators: Handbook of manufacturing engineering and technology. (Springer, 2014).

Yong, Y. K. & Lu, T.-F. Kinetostatic modeling of 3-RRR compliant micro-motion stages with flexure hinges. Mech. Mach. Theory 44, 1156–1175 (2009).

AbuZaiter, A., Hikmat, O. F., Nafea, M. & Ali, M. S. M. Design and fabrication of a novel XYθz monolithic micro-positioning stage driven by NiTi shape-memory-alloy actuators. Smart Mater. Struct. 25, 105004 (2016).

Xu, C. S. et al. An open-access volume electron microscopy atlas of whole cells and tissues. Nature 599, 147–151 (2021).

Hoffman, D. P. et al. Correlative three-dimensional super-resolution and block-face electron microscopy of whole vitreously frozen cells. Science 367, eaaz5357 (2020).

Huang, H. B., Sun, D., Mills, J. K. & Cheng, S. H. Robotic cell injection system with position and force control: toward automatic batch biomanipulation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 25, 727–737 (2009).

Kim, H.-Y., Ahn, D.-H. & Gweon, D.-G. Development of a novel 3-degrees of freedom flexure based positioning system. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 055114 (2012).

Chi, Z., Xu, Q. & Zhu, L. A review of recent advances in robotic cell microinjection. IEEE Access 8, 8520–8532 (2020).

Xu, Q. Micromachines for biological micromanipulation. (Springer, 2018).

Wang, R. & Zhang, X. A planar 3-DOF nanopositioning platform with large magnification. Precis. Eng. 46, 221–231 (2016).

Lee, C., Lee, J. W., Ryu, S. G. & Oh, J. H. Optimum design of a large area, flexure based XYθ mask alignment stage for a 12-inch wafer using grey relation analysis. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 58, 109–119 (2019).

Al-Jodah, A. et al. Development and control of a large range XYΘ micropositioning stage. Mechatronics 66, 102343 (2020).

Lum, G. Z., Teo, T. J., Yeo, S. H., Yang, G. & Sitti, M. Structural optimization for flexure-based parallel mechanisms – Towards achieving optimal dynamic and stiffness properties. Precis. Eng. 42, 195–207 (2015).

Choi, K.-B. & Lee, J. J. Passive compliant wafer stage for single-step nano-imprint lithography. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 76, 075106 (2005).

Lin, Y. T. & Lee, J. J. Structural synthesis of compliant translational mechanisms. in Proceedings of the 12th IFToMM World Congress, 1–5 (2007)

Bhagat, U. et al. Design and analysis of a novel flexure-based 3-DOF mechanism. Mech. Mach. Theory 74, 173–187 (2014).

Wang, R. & Zhang, X. Optimal design of a planar parallel 3-DOF nanopositioner with multi-objective. Mech. Mach. Theory 112, 61–83 (2017).

Kim, C. J., Moon, Y.-M. & Kota, S. A building block approach to the conceptual synthesis of compliant mechanisms utilizing compliance and stiffness ellipsoids. J. Mech. Des. 130, 022308 (2008).

Pinskier, J. et al. Topology optimization of stiffness constrained flexure-hinges for precision and range maximization. Mech. Mach. Theory 150, 103874 (2020).

Ogata, K. Modern control engineering. 5 edn (Prentice Hall, 2010).

Pham, M. T., Teo, T. J. & Yeo, S. H. Synthesis of multiple degrees-of-freedom spatial-motion compliant parallel mechanisms with desired stiffness and dynamics characteristics. Precis. Eng. 47, 131–139 (2017).

Lum, G. Z., Teo, T. J., Yang, G., Yeo, S. H. & Sitti, M. Integrating mechanism synthesis and topological optimization technique for stiffness-oriented design of a three degrees-of-freedom flexure-based parallel mechanism. Precis. Eng. 39, 125–133 (2015).

Kim, H. & Gweon, D.-G. Development of a compact and long range XYθz nano-positioning stage. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 085102 (2012).

Park, J., Lee, H., Kim, H., Kim, H. & Gweon, D. Note: Development of a compact aperture-type XYθz positioning stage. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 87, 036112 (2016).

Yang, Y., Wu, G. & Wei, Y. Design, modeling, and control of a monolithic compliant x-y-θ microstage using a double-rocker mechanism. Precis. Eng. 71, 209–231 (2021).

Gan, J., Zhang, X., Li, H. & Wu, H. Full closed-loop controls of micro/nano positioning system with nonlinear hysteresis using micro-vision system. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 257, 125–133 (2017).

Wang, R. & Zhang, X. Parameters optimization and experiment of a planar parallel 3-DOF nanopositioning system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 65, 2388–2397 (2018).

Chu, C.-L., Chen, H.-C. & Sie, M.-H. Development of a XYθz 3-DOF nanopositioning stage with linear displacement amplification device. In MATEC Web of Conferences, Vol. 123 00006 (2017).

Lu, T. F., Handley, D. C., Kuan Yong, Y. & Eales, C. A three‐DOF compliant micromotion stage with flexure hinges. Ind. Robot.: Int. J. 31, 355–361 (2004).

Zhu, W.-L. et al. Redundantly piezo-actuated XYθz compliant mechanism for nano-positioning featuring simple kinematics, bi-directional motion and enlarged workspace. Smart Mater. Struct. 25, 125002 (2016).

Guo, Z. et al. Design and control methodology of a 3-DOF flexure-based mechanism for micro/nano-positioning. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 32, 93–105 (2015).

Cai, K., Tian, Y., Wang, F., Zhang, D. & Shirinzadeh, B. Development of a piezo-driven 3-DOF stage with T-shape flexible hinge mechanism. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 37, 125–138 (2016).

Jin, M. & Zhang, X. A new topology optimization method for planar compliant parallel mechanisms. Mech. Mach. Theory 95, 42–58 (2016).

Lum, G. Z., Teo, T. J., Yang, G., Yeo, S. H. & Sitti, M. in IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics 247-254 (2013).

Zhang, C., Yu, H., Yang, M., Chen, S. & Yang, G. Nonlinear kinetostatic modeling and analysis of a large range 3-PPR planar compliant parallel mechanism. Precis. Eng. 74, 264–277 (2022).

Yu, H. et al. The design and kinetostatic modeling of 3PPR planar compliant parallel mechanism based on compliance matrix method. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 90, 045102 (2019).

Al-Jodah, A., Shirinzadeh, B., Ghafarian, M., Das, T. K. & Pinskier, J. Design, modeling, and control of a large range 3-DOF micropositioning stage. Mech. Mach. Theory 156, 104159 (2021).

Navale, R., Patil, A. K., Minase, J. & Pandhare, A. Development of a novel three degree of freedom XYθz micro-motion stage. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 14, 1758–1774 (2021).

Yang, M., Sun, M., Wu, Z., Li, J. & Long, Y. Design of a redundant actuated 4-PPR planar 3-DOF compliant nanopositioning stage. Precis. Eng. 82, 68–79 (2023).

Tian, Y., Shirinzadeh, B. & Zhang, D. Design and dynamics of a 3-DOF flexure-based parallel mechanism for micro/nano manipulation. Microelectron. Eng. 87, 230–241 (2010).

Dong, H., Liu, P., Lu, S., Yan, P. & Sun, Q. Long-travel 3-PRR parallel platform based on biomimetic variable-diameter helical flexible hinges. Micromachines 15, 338 (2024).

Townsend, W. T. & Salisbury, J. K. in IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. 1390-1395 (IEEE Computer Society).

Booker, L. B., Goldberg, D. E. & Holland, J. H. Classifier systems and genetic algorithms. Artif. Intell. 40, 235–282 (1989).

Lum, G. Z. et al. Shape-programmable magnetic soft matter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E6007–E6015 (2016).

Xu, C., Yang, Z. & Lum, G. Z. Small-scale magnetic actuators with optimal six degrees-of-freedom. Adv. Mater. 33, e2100170 (2021).

Ng, C. S. X. et al. Locomotion of miniature soft robots. Adv. Mater. 33, e2003558 (2021).

Zhou, A. et al. Magnetic soft millirobots 3D printed by circulating vat photopolymerization to manipulate droplets containing hazardous agents for in vitro diagnostics. Adv. Mater. 34, e2200061 (2022).

Hong, Y. et al. Boundary curvature guided programmable shape-morphing kirigami sheets. Nat. Commun. 13, 530 (2022).

Jones, T. J., Jambon-Puillet, E., Marthelot, J. & Brun, P. T. Bubble casting soft robotics. Nature 599, 229–233 (2021).

Hu, W., Lum, G. Z., Mastrangeli, M. & Sitti, M. Small-scale soft-bodied robot with multimodal locomotion. Nature 554, 81–85 (2018).

Yang, Z., Xu, C., Lee, J. X. & Lum, G. Z. Magnetic miniature soft robot with reprogrammable drug‐dispensing functionalities: toward advanced targeted combination therapy. Adv. Mater. 48, 2408750 (2024).

Xu, T., Zhang, J., Salehizadeh, M., Onaizah, O. & Diller, E. Millimeter-scale flexible robots with programmable three-dimensional magnetization and motions. Sci. Robot. 4, eaav4494 (2019).

Diller, E. & Sitti, M. Three‐dimensional programmable assembly by untethered magnetic robotic micro‐grippers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 4397–4404 (2014).

Ma, K. Y., Chirarattananon, P., Fuller, S. B. & Wood, R. J. Controlled flight of a biologically inspired, insect-scale robot. Science 340, 603–607 (2013).

Chen, Y. et al. Controlled flight of a microrobot powered by soft artificial muscles. Nature 575, 324–329 (2019).

Hines, L., Campolo, D. & Sitti, M. Liftoff of a motor-driven, flapping-wing microaerial vehicle capable of resonance. IEEE Trans. Robot. 30, 220–232 (2013).

Lu, Y. et al. Stretchable graphene–hydrogel interfaces for wearable and implantable bioelectronics. Nat. Electron. 7, 51–65 (2024).

Lv, Z. et al. Strain-driven auto-detachable patterning of flexible electrodes. Adv. Mater. 34, 2202877 (2022).

Amjadi, M., Kyung, K.-U., Park, I. & Sitti, M. Stretchable, Skin-mountable, and wearable strain sensors and their potential applications: a review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 1678–1698 (2016).

Wang, D. et al. Sensing-triggered stiffness-tunable smart adhesives. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf4051 (2023).

Son, D., Liimatainen, V. & Sitti, M. Machine learning-based and experimentally validated optimal adhesive fibril designs. Small 17, 2102867 (2021).

Ruotolo, W., Brouwer, D. & Cutkosky, M. R. From grasping to manipulation with gecko-inspired adhesives on a multifinger gripper. Sci. Robot. 6, eabi9773 (2021).

Zhou, X. et al. 3D printed auxetic structure-assisted piezoelectric energy harvesting and sensing. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301159 (2023).

Schlinquer, T., Homayouni-Amlashi, A., Rakotondrabe, M. & Ousaid, A. M. Design of piezoelectric actuators by optimizing the electrodes topology. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 6, 72–79 (2021).

Guzmán, D. G., Silva, E. C. N. & Rubio, W. M. Topology optimization of piezoelectric sensor and actuator layers for active vibration control. Smart Mater. Struct. 29, 085009 (2020).

Kim, S.-W. et al. Determination of the appropriate piezoelectric materials for various types of piezoelectric energy harvesters with high output power. Nano Energy 57, 581–591 (2019).

Tan, M. W. M., Bark, H., Thangavel, G., Gong, X. & Lee, P. S. Photothermal modulated dielectric elastomer actuator for resilient soft robots. Nat. Commun. 13, 6769 (2022).

Chen, B., Wang, N., Zhang, X. & Chen, W. Design of dielectric elastomer actuators using topology optimization on electrodes. Smart Mater. Struct. 29, 075029 (2020).

Gomes, A. A. & Suleman, A. Application of spectral level set methodology in topology optimization. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 31, 430–443 (2006).

Wang, M. Y., Wang, X. & Guo, D. A level set method for structural topology optimization. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 192, 227–246 (2003).

Bendsoe, M. P. & Sigmund, O. Topology optimization: theory, methods, and applications. (Springer, 2003).

Garcia, R. Nanomechanical mapping of soft materials with the atomic force microscope: methods, theory and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 5850–5884 (2020).

Tian, Y., Shirinzadeh, B. & Zhang, D. A flexure-based mechanism and control methodology for ultra-precision turning operation. Precis. Eng. 33, 160–166 (2009).

P-517*P-527 Multi – Axis Piezo Scanner, https://www.physikinstrumente.com/en/products/nanopositioning-piezo-flexure-stages/multi-axis-piezo-flexure-stages/p-517-p-527-multi-axis-piezo-scanner-201500 (1996).

NNS-XY100RZ2-01 High resolution nano-positioner, https://www.symc-tec.com/product/443.html (2019).

Pham, M. T., Teo, T. J., Yeo, S. H., Wang, P. & Nai, M. L. S. A 3-D printed Ti-6Al-4V 3-DOF compliant parallel mechanism for high precision manipulation. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 22, 2359–2368 (2017).

Hubbard, N. B., Culpepper, M. L. & Howell, L. L. Actuators for micropositioners and nanopositioners. Appl. Mech. Rev. 59, 324-334 (2006)

Schitter, G., Rijkée, W. F. & Phan, N. in 2008 47th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control. 5176-5181 (IEEE).

Polit, S. & Dong, J. Development of a high-bandwidth XY nanopositioning stage for high-rate micro-/nanomanufacturing. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 16, 724–733 (2010).

Camacho, E. F. & Alba, C. B. Model predictive control. (Springer science & business media, 2007).

Xie, Y. M. & Steven, G. P. Evolutionary structural optimization. (Springer, 1997).

Tai, K. & Akhtar, S. Structural topology optimization using a genetic algorithm with a morphological geometric representation scheme. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 30, 113–127 (2005).