Abstract

Neuromorphic computing offers transformative potential for AI in resource-constrained environments by mimicking biological neural efficiency. This perspective article analyzes recent advances and future directions, advocating a system design approach that integrates specialized sensing (e.g., event-based cameras), brain-inspired algorithms (SNNs and SNN-ANN hybrids), and dedicated neuromorphic hardware. Using vision-based drone navigation (VDN) as an exemplar—drawing parallels with biological systems like Drosophila—we demonstrate how these components enable event-driven processing and overcome von Neumann architecture limitations through near-/in-memory computing. Key challenges include large-scale integration, benchmarking standardization, and algorithm-hardware co-design for emerging applications, which we discuss alongside current and future research directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The quest to create intelligent systems that can sense, learn, and reason has driven innovation for decades. Biological systems exemplify remarkable efficiency; for instance, the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), with about 100,000 neurons, operates on a power budget of just a few microwatts1. Despite this extremely limited energy consumption, it is capable of executing agile and complex maneuvers in dynamic environments. At the other end of the spectrum, modern artificial intelligence (AI) systems have achieved remarkable progress in performing complex cognitive and reasoning tasks—at times even surpassing biological systems in specific domains. Machine learning (ML), in particular, has played a pivotal role in narrowing the gap between artificial and biological intelligence by enabling machines to learn and generalize from large-scale data. However, these achievements often come with substantial computational and energy costs. State-of-the-art deep neural networks (DNNs) typically require hundreds of watts of power and exhibit high latency2, posing serious challenges for deployment in resource-constrained environments such as edge devices. In contrast, the human brain performs sensing, learning, and reasoning in an integrated and highly energy-efficient manner, with extremely low power consumption and latency. This disparity has spurred increasing interest in leveraging insights from biological neural computation. To address the limitations of current DNNs, various optimization strategies have been proposed, including quantization3, pruning4, and the design of compact, efficient network architectures5. Nevertheless, these techniques remain limited in their ability to match the brain in their performance, efficiency, and latency trade-offs. This leads to a critical research question: Can we take suitable bio-inspired cues and develop novel neuromorphic algorithms and hardware to mimic the performance and efficiency of the brain in present-day AI systems?

The DNNs of today are weakly inspired by the topology of the brain, that contains millions of ‘artificial neurons’, interconnected through billions of weights across several layers. However, there are several key differences - (i) standard feed-forward DNNs (hereafter referred to as Analog Neural Networks or ANNs to distinguish them from spike-based networks) perform computations using analog activations instead of binary activations, or more specifically, energy-efficient spike-based processing, as in the brain; (ii) the processing and storage units in traditional deep learning hardware such as GPUs, are usually separated, leading to large latency and energy penalty for moving data between processing unit and the memory, while the brain consists of co-located compute (neurons) and storage (synapses); and (iii) the biological network has intricate and recurrent three-dimensional connectivity, whereas the current silicon technology is mostly limited to a two-dimensional topology. In addition, sequential data processing with ANNs requires specialized architectures such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs)6 and long-short term memory networks (LSTMs)7,8, which contain explicit feedback connections and memory elements to keep track of temporal information. Such improved sequential processing capabilities come at the cost of higher number of parameters, high training complexity, and slow inference.

Neuromorphic computing, inspired by the architecture and operation of the brain, has emerged as a possible avenue to enhance the efficiency of the machine learning pipelines9. In recent years, Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs)10,11, sometimes referred to as the third generation of neural networks have shown promising potential towards realizing brain-like spike-based computing. SNNs perform sparse, and event-driven computations making them an attractive alternative to ANNs12. They are also inherently recurrent in nature due to the presence of intrinsic memory elements in spiking neurons making them suitable for real-world sequential tasks. A spiking neuron such as the leaky-integrate-and-fire (LIF) neuron consists of parameters such as the membrane potential and leak, that act as memory elements to retain data over time and provide a lightweight gating mechanism to forget past information, respectively. This temporal information-capturing ability of SNNs can effectively make them simpler and more efficient than standard sequential learning architectures like RNNs and LSTMs. In fact, it has been shown that a network of modified LIF neurons can perform at par with LSTMs even with lower parameters13.

To leverage the distinct properties of SNNs, targeting suitable tasks, selecting proper input representation, and developing learning algorithms geared explicitly for them are essential. In terms of input representations, for converting real-valued static inputs to spike trains, direct input encoding14,15,16 where the first layer of the neural network acts as a learnable spike encoder, has greatly improved the efficiency and enabled training of deep SNNs. However, SNNs are not optimal for usage with such static inputs as they inherently lack temporal information. In light of this, sensing technologies such as event-based cameras17 are of particular interest due to bio-plausible sensing and inherent compatibility with SNNs. Certain use cases might require a multi-modal sensing approach18 involving both frame- and event-based cameras to obtain appropriate inputs. In fact, a hybrid combination of SNN and ANN architectures can potentially simplify training and lead to improved performance18,19. Although there are other input modalities that can work well with the sequential processing in SNNs such as text20, speech21, and biomedical signals such as EEG22, ECG, etc., we limit our discussion to vision-based sensors.

Even with suitable inputs and learning algorithms, fully unlocking the potential of neuromorphic computing demands consideration of underlying hardware fabrics. Traditional computing architectures in machine learning often suffer inefficiencies due to the separation of memory and processing units—an issue exacerbated in Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), which require additional data structures such as membrane potentials, neuronal thresholds, and leak parameters. In addition, the ability to effectively perform event-driven computations on asynchronous inputs while leveraging sparsity is essential to realize the true potential of SNNs. Neuromorphic hardware development is therefore critical. Initially inspired by silicon neural models23 including silicon neurons24 and retinas25, the field has advanced through digital event-driven architectures26,27,28,29 and analog/digital in-memory computing approaches30,31,32,33. These overcome von Neumann bottlenecks while improving energy efficiency versus GPUs/DNN accelerators. However, challenges remain, especially related to the large and energy-intensive interface circuitry, such as data converters. Additionally, emerging hybrid architectures capable of integrating both ANN and SNN computations34,35,36 show promise in achieving versatile, application-specific performance. These developments are particularly critical in robotic vision tasks, enabling efficient processing for autonomous perception, object tracking, and real-time decision-making. In this paper, we comprehensively review algorithmic progress alongside recent hardware innovations, highlighting pathways toward optimized neuromorphic systems specifically designed for robotic vision.

Cognitive system design

A cognitive system is an artificial or computational system designed to simulate or mimic human cognitive processes such as perception, reasoning, learning, and decision-making. The design of such a system is heavily inspired by present-day biological systems operating with similar resources on real-world inputs. This includes mimicking a biological system not only in terms of accuracy but also match their low energy consumption and latency. Many modern-day deep learning systems offer exceptional performance on very complex tasks, such as language and video generation leveraging enormous compute and edge-cloud communication requirements. However, such combined processing between the edge and the cloud is non-existent in biological systems as they operate in a standalone fashion. As such, in this paper, we limit the scope of discussion mostly to the edge, where there is a need for real-world tasks to be accomplished with smaller and more intelligent models that can be both fast and efficient.

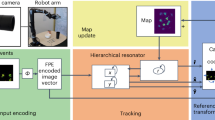

To analyze this, we consider vision-based drone navigation (VDN) as an exemplary application driver. Previous studies, such as37, have investigated neuromorphic perception and behavior, while38 has examined the use of bio-plausibility in guiding neuromorphic robotic systems. Nonetheless, the applications addressed in these studies are relatively simplistic, and the proposed models encounter challenges when scaling to more complex real-world scenarios. The VDN application draws inspiration from the seamless navigation capabilities of a fruit fly and encompasses a variety of facets; the need for a small and highly resource constrained system with the ability to operate standalone on real-world sequential inputs and carry out complex as well as simple sub-tasks in a fast and efficient manner. The drone must acquire a holistic scene understanding of the surrounding environment through underlying perception tasks, such optical flow estimation, depth estimation, semantic segmentation, object detection/tracking, etc. (depicted in the bottom row of Fig. 1). Note that some of these tasks such as optical flow, object detection and tracking etc. are sequential in nature, i.e., they need to take into account the temporal dependence across inputs for obtaining accurate predictions. Developing low-power algorithms to perform these tasks on board a drone platform with limited computing is a key challenge. With this goal in mind, there is a need to explore proper sensors (and correspondingly suitable input representations), appropriate network architectures, and suitable training methods while considering the associated challenges.

(Top-left) Inputs and Sensing: Depiction of frame- and event-based inputs for multiple moving objects, demonstrating how traditional frame cameras capture analog intensity information while event cameras detect motion-induced intensity variations. The biological pathway shows the human eye, illustrating how biological systems perceive changes in intensity and color. The neuromorphic sensing section displays both frame-based cameras and event-based cameras working together to capture similar information. (Top-right) Neural Processing: The top biological networks section depicts neurons with synapses and interconnected neural pathways, representing the brain’s highly parallel and recurrent connections that perform computations within memory itself for exceptional efficiency. The central neuromorphic algorithms section shows various neuron types including ReLU and LIF (Leaky Integrate-and-Fire) neurons, alongside different network architectures: ANNs (Artificial Neural Networks), SNNs (Spiking Neural Networks), and Hybrid SNN-ANN configurations that combine the best of both approaches for optimal algorithmic accuracy and efficiency. The hardware section presents conventional processors (CPU, GPU, FPGA) alongside neuromorphic-specific architectures including NVM-based IMC (Non-Volatile Memory-based In-Memory Computing) and hybrid hardware solutions, utilizing device technologies such as RRAM and STT-MRAM that can efficiently implement synaptic memories and work with CPU/GPU architectures for improved efficiency and latency. (bottom) Practical implementation for vision-based drone navigation (VDN), showcasing four key vision tasks: optical flow, depth estimation, segmentation, and object detection.

Inputs and sensing

The design of an optimal cognitive system begins with effectively sensing raw information from the environment, i.e. the inputs. In the case of vision, traditionally, frame-based cameras have been the go-to for machine vision tasks. They sample intensity information across all pixels of the image sensor synchronously at a fixed and slow sampling rate, leading to a rich and dense representation of the observed visual information. Although useful for fine-grained detection and recognition tasks such as face recognition, image analyses, etc., frame-based data is sub-optimal for tasks relating to the VDN application. This is due to the lack of high-speed temporal information in frame-based data which is essential for fast motion scenarios. In addition, the rich intensity information, although useful, is not required for most tasks and incurs additional storage and compute overheads adding to the latency of the system. Keeping these in mind, the ideal desired characteristics of the inputs would be sparse and asynchronous data that captures the changes in the environment at extremely high temporal resolutions while being fairly efficient in terms of required computing. There has been an emergence and subsequent advancements in neuromorphic vision sensors termed as event-based cameras (DVS12817, DAVIS24039, SamsungDVS40, Prophesee Gen441, Sony HVS42 etc.) inspired by the retinal ganglion cells40 in the human eye. Event cameras generate an asynchronous and sparse stream of binary events by independently sampling the log-scale intensity (I) at every pixel element. A binary output event or spike is generated when the change exceeds a threshold (C):

Due to this fundamentally distinct mode of sensing, event-based cameras offer high temporal resolution (10us vs 3ms), low power consumption for sensing (10mW vs 3W), and high dynamic range (120dB vs 74dB) compared to frame-based cameras43. These properties naturally make them the sensors of choice for the exemplary VDN application. Note that, frame-based data still holds some value for enhancing accuracy in certain tasks18, thus a sensor fusion approach can be utilized to obtain elevated performance at the cost of efficiency when needed.

Learning algorithms and architectures

Having decided on the appropriate input representation for a particular application, the next important design step is the choice of a suitable network architecture and the related algorithms to train them (middle section of Fig. 1). While SNNs are inherently suited for the set of sequential tasks encountered in VDN (segmentation, optical flow or depth estimation, simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), etc.), over the past decade, ANNs have been widely used for such tasks. Note, however, that algorithmic progress in ANNs has also served as a foundation for developing corresponding neuromorphic algorithms using SNNs. As such, it is worth revisiting popular ANN-based approaches targeting VDN. Usually, these ANNs employ an encoder-decoder type backbone for such tasks, where the encoder layers transform the input into a suitable intermediate representation. These are followed by the decoder layers which transform the hidden layer embeddings into the desired output map (segmentation, optical flow or depth estimation, etc.). For both types of layers, various convolutional neural networks (CNNs)44,45,46 have been employed successfully over the years. Recently, transformer-based models have emerged for vision applications offering higher performance47,48,49 at the cost of increased model size and computational complexity. If we zoom in specifically towards robotic perception tasks using event-based cameras, ANN-based models offer decent performance50,51,52 but suffer in terms of energy consumption.

Most of the conventional ANNs either operate on static frame-based inputs44,46 or have to combine numerous events over a time window to obtain a merged representation50,51 where the temporal cues get lost. As a result, it becomes increasingly challenging to learn long-term temporal dependencies using these networks. However, for a neuromorphic agent to be successful, it is imperative to adapt to the ever-evolving sequential nature of the environment. Considering this, RNNs, LSTMs, and gated recurrent units (GRUs) have been utilized in conjunction with CNNs53,54 to facilitate sequential processing using explicit feedback and memory units. However, they lead to challenges such as high network complexity with a large parameter count, considerable energy consumption, and training difficulties. Another promising direction in this area is using event-based graph neural networks (GNNs) that can process events as evolving spatio-temporal graphs achieving several fold reduction in computational complexity and latency55,56 for tasks such as optical flow and object detection. Recently, such algorithmic progress has been accompanied by the development of GNN-based accelerators57,58.

Keeping the pros and cons of ANN-based processing for sequential tasks in mind, next, we focus on SNN-based neuromorphic algorithms which can play a vital role in achieving low-complexity models with superior temporal processing capabilities. SNNs represent a computationally simpler alternative to RNNs or LSTMs for VDN tasks. The simplicity in SNNs is achieved by utilizing a singular memory element termed as the membrane potential, compared to LSTMs that require several gates (input, output, forget gates) to capture temporal information. The membrane potential in a spiking neuron accumulates information over several timesteps, effectively and simplistically encoding temporal dependencies in the data, making SNNs well-suited for tasks that require sequential processing. In this respect, SNNs have been shown to achieve comparable accuracy LSTMs for speech recognition, but with 2 × fewer parameters13. The sparse SNN outputs also lead to 10.13 × and 11.14 × savings in multiplication operations compared to GRUs13, another recurrent architecture. However, it is important to note that deep SNNs, characterized by multiple layers and complex architectures, are often faced with challenges in the training process that affect their performance. Two main issues come into play: vanishing spikes and non-differentiable activation functions59,60. Vanishing spikes occur when the neuronal activations gradually die out in the deeper layers, hindering the flow of information through the network. Additionally, SNNs use the non-differentiable step activation to generate spikes, making traditional backpropagation techniques incompatible with gradient descent-based training. Over the past few years, there have been several advancements to overcome these limitations. Techniques such as ANN to SNN conversion61,62,63 and using learnable neuronal dynamics (thresholds and leaks)14,64 have essentially alleviated the vanishing spikes issue. On the other hand, various surrogate gradient-based approaches60,65,66,67,68,69 have emerged to solve the non-differentiable nature of the spiking activation function. Recent developments have further enhanced training strategies, including advanced training approaches like temporal pruning70, batch-normalization through time71, custom regularizers72 and modified neuron models73. Motivated by the above algorithmic progress, SNNs are becoming increasingly popular for VDN tasks. Note, there are other complex population-based SNN approaches74, or predictive or temporal coding based SNN models75,76,77. However, we focus mostly on SNNs with stateful membrane based temporal features of instantaneous spiking behavior as they have been shown to scale to more complex tasks (such as VDN), which have been challenging for the evolutionary or temporal methods.

Considering all of the above, it is evident that different kind of algorithms and architectures have their own pros and cons when paired with inputs and employed for a task. Thus, it is essential to carefully construct these pairings in order to obtain optimal efficiency and accuracy while staying within the limitations set by the edge. Let us consider two example tasks and their current optimal solutions from an edge implementation standpoint.

Optical flow

Consider the task of optical flow estimation, which involves determining the movement of pixel intensities over time in the visual field of the sensor. This task is inherently sequential and demands that the underlying sensing and algorithms capture temporal dependencies78,79. In terms of sensors, event-based cameras turn out to be suitable for capturing high-speed motion information. In terms of algorithms, traditional ANNs50,51 require that the high-speed event bins be stacked in the channel dimension before being input to the neural network. Conversely, a fully SNN model has the potential to capture temporal information effectively, leading to improved performance. A recent work, Adaptive-SpikeNet64, operates directly on a sequence of input event bins from an event-based camera and uses a full-SNN architecture with layerwise learnable neuronal dynamics of leaky-integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons to address the vanishing spikes issue, enabling spike retention across the entire network. Effectively capturing temporal information not only improves application accuracy, measure in terms of average endpoint error (AEE), but also allows for smaller models, making it suitable for edge computing. Adaptive-SpikeNet showed 20% lower error compared to a full-ANN model of similar size, on the MVSEC dataset80. Experiments also showed that a smaller Adaptive-SpikeNetNano model, with 0.27 million parameters (48 times lower), showed a similar error rate as the larger full-ANN model, resulting in approximately 10 times lower energy consumption. These findings underscore the effectiveness of SNNs over ANNs for sequential tasks such as optical flow estimation, which depend heavily on temporal information and inputs such as events that contain limited spatial or texture information.

Simultaneously, efforts have been made to explore hybrid SNN-ANN architectures to address spike vanishing and leverage the ease of training in ANNs. Such hybrid architectures18,19,81 aim to harness the complementary benefits of SNNs and ANNs, offering improved performance with modest energy improvements. One of the initial works, titled Spike-FlowNet19, consists of an SNN encoder coupled with an ANN decoder to process event inputs and predict optical flow. This approach yielded similar performance compared to the fully-ANN baseline (Ev-FlowNet)50 while offering a modest, 1.21 × lower energy consumption. However, Adaptive-Spikenet64 discussed earlier with its fully-SNN architecture outperforms this method due to both works operating on events that contain limited spatial information. Thus, the usage of ANN layers in Spike-FlowNet19 is detrimental to both the performance and efficiency of the model. Additionally, there have been efforts to combine input information from frame-based cameras and event-based cameras into a sensor-fusion model where using an SNN-ANN hybrid proves to be beneficial. For instance, Fusion-FlowNet18 uses events over time as inputs to an SNN encoder and grayscale frames over channels as inputs to an ANN encoder. Sensor fusion enables superior feature extraction, leading to improved performance and allowing for model size reduction. In fact, Fusion-FlowNet with 7.55 million parameters (half of fully-ANN) achieves 40% lower error than fully-ANN while also obtaining an energy reduction of 1.87 times. The architectures for these approaches are illustrated in Fig. 2, and their performance is compared in Fig. 3. It is evident that Fusion-FlowNet18, an SNN-ANN hybrid operating on a fusion of frame and event inputs, is adept at capturing both temporal and spatial information, thereby attaining the lowest AEE. When working with event-only inputs due to their low energy sensing, fully-SNN architectures from Adaptive-SpikeNet64 result in lower AEE values compared to fully-ANN50 and SNN-ANN hybrid19 approaches. All these approaches serve as stepping stones towards developing architectures that can attain brain-like intelligence and efficiency.

a Outputs from frame-based, event-based, and sensor-fused frame+event cameras. b U-Net160 based Encoder-Residual-Decoder architectures for Fully-ANN, Fully-SNN and Hybrid SNN-ANN topologies, employed for optical flow estimation. The red block depicts the output accumulator for aggregating SNN outputs over time. c Sensor-fused hybrid SNN-ANN architecture using both event and frame modalities for estimating optical flow. (Adapted with permission from Fusion-FlowNet18. Copyright 2022, IEEE). The architecture consists of SNN and ANN encoder blocks to handle event and frame inputs respectively.

SOTA baselines (EvFlow-Net50, Spike-FlowNet19 and Fusion-FlowNet18 have their average endpoint error (AEE) depicted on the left. The right side compares the AEE between fully-ANN and fully-SNN architectures with decreasing model sizes. (Data taken with permission from Adaptive-SpikeNet64. Copyright 2023, IEEE).

Speed-based object detection

For a much simpler task of object detection, where an object needs to be detected and tracked over time, event cameras demonstrate higher potential due to their ability to capture clean information for fast-moving objects. In comparison to full-ANN and hybrid models, a full-SNN model is, in fact, most suited for such an application since the inherent dynamics of the spiking neurons can be used to filter out events based on their speed. This is showcased by authors of DOTIE82 with an extremely lightweight and robust implementation by utilizing a single layer SNN with LIF neurons to separate objects based on their speed followed by a clustering method to obtain a bounding box around the object. This method can also detect the large number of background events caused by camera movement. These events can be grouped into a speed category that matches the background motion, allowing them to be filtered out and thereby acting as an alternative to traditional egomotion correction methods. Figure 4 showcases the lightweight speed-based object detection using the DOTIE framework.

A single-layer SNN utilizing its inherent leak to filter out events moving at a speed greater than a specified value. These speed-separated events are then clustered to obtain a bounding box for object detection. (Adapted with permission from DOTIE82. Copyright 2023, IEEE).

While the above approaches have been detailed for certain specific tasks, their fundamental principles are generic and can be applied to a range of other perception tasks across various applications. In the context of the example VDN, brain-inspired AI algorithms like SNNs and hybrid SNN-ANNs, coupled with sensors such as event-based cameras, offer promising solutions for performing real-world sequential tasks at the edge.

Hardware for cognitive systems

SNNs and hybrid ANN-SNN architectures mimic biological neuronal behaviors, effectively handling sequential tasks with sparse, event-driven inputs. However, efficiently implementing these architectures on conventional von Neumann hardware remains challenging because of the data movement overhead. Figure 5 illustrates several representative neuromorphic hardware architectures, highlighting key differences in dataflow, memory integration, and compute organization across von Neumann and non-von Neumann systems.

(Top) Simplified architecture of a CPU, a GPU, and a custom multi-chip accelerator. CPUs and GPUs follow von Neumann architecture, where computation is separate from memory. On the other hand, a large number of custom hardware accelerators follow a 2-D mesh-like hierarchical design with memory and computation units distributed across the whole fabric. (Top right) The design of a SpiNNaker28 node is shown where each node uses a packet router to communicate spikes using a routing table. Multiple such nodes can be connected to make a massively parallel computing system. (Bottom left) Truenorth26 uses a 2-D mesh network of neurosynaptic cores that have crossbar-like connectivity where input spikes are mapped at the rows, each column represents an output neuron, and the crosspoint represents the synaptic connections. (Bottom right) A generalized representation of a hierarchical in-memory computing core. Each core in the figure consists of multiple compute blocks, and each compute block contains multiple in-memory computing arrays arranged in a crossbar format. An analog in-memory computing array is depicted in the figure with digital-to-analog converters (DACs) at the row periphery and a shared analog-to-digital Converter (ADC) at the column periphery.

In-memory computing (IMC) techniques address this challenge by performing computations within or near memory arrays, dramatically reducing data movement31,32,33,83,84,85,86,87,88. Embedded non-volatile memory (NVM) technologies—including RRAM, PCM, STT-MRAM, and FeFET—further offer promising support for IMC by providing higher density, lower power, and inherent neuronal and synaptic emulation capabilities83,85,87,88,89,90,91. Nevertheless, NVM technologies pose challenges such as device non-linearities, high write currents and limited write endurance, particularly during on-device training which requires frequent weight updates.

A critical hardware bottleneck common to analog IMC architectures is the overhead introduced by analog-to-digital converters (ADCs). To mitigate this, researchers propose ADC-less92,93 or analog-domain accumulation33,94 approaches, which reduce domain conversion overheads but face challenges in maintaining the accuracy given the non-ideal nature of analog computations. Employing hardware-aware training methods—such as hardware-in-the-loop training can help overcome these limitations95.

Hybrid ANN-SNN networks inherently demand innovative hardware solutions, given their contrasting computational requirements: event-driven asynchronous spike processing for SNNs and parallel, synchronous processing for ANNs. ADC dependence can be reduced by strategically partitioning the network into event-driven SNN components and highly parallel IMC ANN components. Furthermore, techniques like mixed-signal neurons, which accumulate in the analog domain but fire digitally33,96, can minimize the need for domain conversion.

Biologically plausible neuron models, essential for realistic neural emulation, require complex transcendental computations (exponential, sigmoid, tanh) often implemented using memory-intensive look-up tables (LUTs). Solutions like ROM-embedded RAM97,98 can efficiently store LUTs within memory to reduce external accesses, as demonstrated in architectures such as SPARE86. Apart from neuron models, there is a growing interest in developing bio-plausible network and circuit architectures as demonstrated by the locally dense globally sparse connectivity of87 or the dendritic architectures proposed by D’Agostino et al.99. Looking ahead, there is a clear imperative to explore highly bio-plausible models and architectures with their diverse applications in the fields of neuroscience, medical simulations, robotics, brain-computer interfacing (BCI), etc.

Asynchronous event-driven processing, inherent to SNNs, naturally exploits temporal and spatial data sparsity, enabling highly efficient, low-power computation. Numerous SNN accelerators have explored asynchronicity at various levels26,27,28,30,100,101. While early designs favored a globally asynchronous, locally synchronous (GALS) approach26,28, recent trends show a rising preference for fully asynchronous designs101,102,103,104, capable of executing tasks within an ultra-low power budget.

ANN-SNN hybrid designs: must reconcile the asynchronous, sparse spike processing of SNNs with parallel ANN computations. The ongoing exploration of hybrid accelerators28,34,35,36,101,105,106,107,108 represents a noteworthy stride in this direction. These hybrid accelerators can offer a unique synergy by combining the energy-efficient event-driven processing of SNNs with the high accuracy pattern recognition capabilities of ANNs. For instance106, proposes a generalized framework to support the design and computation of hybrid neural networks at a wide range of scales and domains. In this 2020 study107, researchers from IBM propose spiking neural units (SNUs) merging both ANNs and SNNs and offering unique temporal dynamics and energy efficiency using in-memory computation. Meanwhile108, presents a system hierarchy for brain-inspired computing that unifies diverse programs and network models, facilitating versatile tasks and converging conventional computing and neuromorphic hardware. Recent large-scale SNN accelerators like Tianjic105, SpiNNaker28,109, and Loihi 2101 also support both ANNs and SNNs.

Furthermore, the researchers in refs. 34,35 develop tailored accelerators for the implementation of hybrid networks featuring on-chip training mechanisms. Aligning with the VDN application discussed earlier, authors in ref. 36 introduce a design specifically for real-time target detection and tracking, employing a hybrid SNN-ANN network. They implement high-speed object-tracking using an SNN at lower accuracy and increase the overall system accuracy by using information from a slower but high-accuracy ANN. Moreover, they use both RRAM IMC and SRAM NMC in their design. This design holds the potential to serve as an optimal hardware approach for the resource-constrained VDN application. Advancing hybrid systems demands clear algorithm-hardware co-design strategies focusing on computational substrates, workload partitioning, strategic memory and compute integration, and event-driven input handling to achieve substantial efficiency improvements over existing computing paradigms.

Algorithm-hardware co-design

While previous sections independently discussed advances in neuromorphic algorithms and hardware, integrating both aspects through algorithm-hardware co-design is increasingly critical110. In this context, co-design specifically refers to developing algorithms while explicitly considering the constraints, capabilities, and non-idealities of the target hardware. This integration occurs predominantly during model training and algorithmic optimization stages rather than solely during hardware design. Such a strategy ensures that neural network models are explicitly adapted to leverage hardware-specific strengths (e.g., sparsity exploitation, reduced precision computations) and mitigate weaknesses (e.g., analog hardware non-linearities, limited ADC precision).

Recent research in SNNs exemplifies this approach, incorporating hardware constraints directly into training algorithms. For example, researchers have proposed hardware-aware dataflow optimization111 and mapping strategies83. Additionally, authors in ref. 93 used quantization-aware training techniques that entirely eliminate the power and area hungry ADCs in analog IMC designs. Furthermore, designing algorithms concurrently with hardware has led to demonstrated gains in energy efficiency and accuracy35,102,103. For instance35, proposes a hybrid ANN-SNN training accelerator where they increase the sparsity during ANN training using the corresponding SNN and design hardware to leverage that sparsity.

Thus, by integrating hardware information directly into the model development process rather than treating it as an independent design activity, co-design ensures neuromorphic systems more effectively emulate biological neural processing capabilities. Such a holistic approach during the training phase is essential for achieving optimal energy efficiency, model accuracy, and practical applicability in diverse real-world scenarios.

Benchmarking cognitive systems

The increasing relevance of SNNs in diverse domains has underscored the critical need for robust benchmarking to objectively evaluate and compare the performance of different algorithms, hardware architectures and system-level implementations. Furthermore, benchmarking helps in identifying optimization opportunities, establishing standards, and ensuring real-world applicability and timely adoption of SNN-based solutions112,113. However, benchmarking neuromorphic systems presents unique challenges due to the high sensitivity of performance metrics to design choices such as network architecture, hardware architecture, and mapping strategies. The interplay among these factors creates a vast design space, making direct numerical comparisons difficult without standardized experimental conditions. Consequently, we refrain from presenting simplified benchmarking tables and instead refer readers to recent systematic benchmarking studies throughout this section. We advocate for the development of standardized evaluation methodologies to fairly and rigorously assess cognitive system designs across neuromorphic and conventional platforms.

Algorithm-level benchmarks

Efforts in this direction include the development of specialized datasets and evaluation methodologies for the spiking domain114,115,116,117,118,119. For instance114, introduced a spike-based version of the MNIST dataset to benchmark visual recognition tasks in the spike domain, while115 proposed a dynamic hand gesture recognition dataset tailored for benchmarking event-driven and spike-based vision systems. However, vision tasks alone are insufficient for benchmarking cognitive systems. To this end116, provided neuromorphic datasets for tasks such as pedestrian detection, action recognition, and fall detection, promoting the use of event-driven sensing in safety-critical applications.117 further developed a benchmark for evaluating various input coding scheme from a robotics perspective. Additionally118, introduced a synthetic flying dataset that includes high-rate ground truth annotations (including pose, optical flow, depth etc.) corresponding to high-speed motion in both indoor and outdoor environments. Similarly119, presented a synthetic dataset with pose and velocity ground truths for objects undergoing rapid motion, specifically focusing on high-speed event-based object detection.

Hardware performance benchmarking

Unlike ANNs, the performance of SNNs is tightly coupled with the characteristics of the computing substrate. Authors in ref. 120 explored this by benchmarking three parallel hardware platforms for a robotic path planning application. Specifically, they compared (i) NEST121 running on a CPU, (ii) SpiNNaker28 as a representative neuromorphic hardware platform, and (iii) GPUs programmed using the GPU enhanced neuronal networks (GeNN) framework122. They found that GPUs achieved the lowest simulation times, while SpiNNaker offered better energy efficiency under certain conditions, illustrating the trade-offs between performance and energy consumption for SNN-based cognitive systems. Similarly123, proposed a benchmark for spatio-temporal tactile pattern recognition and also compared the performance of a standard (analog) classifier algorithm implemented on NVIDIA Jetson GPU and a spike-based model implemented on Intel Loihi.124 also presents a comparison between executing SNNs on traditional (Intel-Xeon W-2123 CPU) vs. neuromorphic hardware (Intel Loihi) platforms, highlighting the performance benefits of using neuromorphic hardware for bio-inspired networks. These works mark an important step towards hardware-aware benchmarking. For a comprehensive benchmarking of neuromorphic integrated circuits, we refer readers to100.

Principles and pitfalls of benchmarking neuromorphic systems

As emphasized by Davies112, adopting superficial or ill-defined benchmarks risks impeding, rather than accelerating, progress. Metrics such as “synaptic operations per second” can be misleading if detached from real-world workloads. Furthermore, benchmarks modeled directly after standard deep learning (e.g., CIFAR-10, ImageNet) may not align with the incremental and continual learning characteristic of neuromorphic systems. The community must prioritize benchmarks that (i) promote biologically plausible learning (e.g., one-shot learning, online learning), (ii) capture temporal aspects of cognition, (iii) span a wide range of problem scales and evaluation metrics, and (iv) provide a method for comparing conventional solutions with neuromorphic solutions.

Emerging frameworks and benchmark suites

The recent NeuroBench113 framework is an important step towards addressing some of the above limitations and standardizing the evaluation of neuromorphic computing. NeuroBench introduces a framework addressing both hardware-independent (algorithm track) and hardware-dependent (system track) evaluations. The current NeuroBench benchmarks include tasks for continual learning, event-based vision, sensorimotor prediction and time-series forecasting and system-level implementations for audio and optimization domains. Additionally, frameworks such as SpikeSim125 and126 signify a concerted effort to benchmark the performance, energy efficiency, latency, and area of IMC-based SNN architectures, with126 focusing on device-level variability, system-level performance, and energy efficiency for NVMs. However, SNN benchmarking efforts are still in their early stages and have yet to reach the level of maturity, breadth, and community adoption seen in standardized suites like MLPerf for conventional deep learning.

Benchmarking ANN-SNN hybrid systems

With the rise of ANN-SNN hybrid systems, benchmarking faces new challenges. Hybrid systems integrate the dense, parallel computation of ANNs with the temporal and sparse processing of SNNs, creating difficulty in unifying the performance metrics across both domains. Moreover, encoding overheads, latency-accuracy trade-offs, and energy modeling become non-trivial when combining fundamentally different computing paradigms. Existing benchmarks often fail to capture these nuances. Future benchmark suites must explicitly address these issues to enable fair and insightful comparisons between hybrid, purely spiking, and conventional systems.

Future directions

Looking forward, we believe there is remarkable value in exploring different SNN-ANN hybrids for event-based applications. A promising approach, as proposed in ref. 127, could be to use the first layer as SNN (to capture the temporal dependencies) and implement the rest of the layers as ANN. However, these hybrid methods are still incipient, and further exploration is required to materialize their full potential. Furthermore, innovation towards developing hybrid architectures from the ground up that can effectively leverage the temporal dimension of SNNs as well as achieve harmonious fusion with ANNs is pivotal. Some efforts in this direction could include neural architecture search (NAS), aiming to obtain specific SNN-ANN hybrid model configurations suited for sequential tasks. In addition to architectural explorations, there is a need to consider emerging learning paradigms in the context of VDN tasks. In what follows, we shed light on some promising research directions along these lines.

Autonomous drones need to adapt to evolving conditions during operation. Therefore, we believe exploring active and continual learning methods with SNNs holds value. This is a challenging problem in general for ANNs as well, however, it is worthwhile to investigate it within the realm of SNNs and SNN-ANN hybrids. One option could be to have the base model trained with backpropagation, while the network is updated using a local learning rule such as spike-timing-dependent-plasticity (STDP)128,129. Other potential approaches could include leveraging self-supervised learning using SNN-ANN hybrids for test-time training130. Furthermore, exploring reinforcement learning with SNN-ANN hybrids could be interesting. While some approaches have been tried with just SNNs for Atari games131, further exploration is required to investigate the suitability of hybrid architectures for complex control tasks132,133. In this context, existing challenges include developing large-scale SNN-oriented reinforcement learning algorithms, designing proper reward functions to capture the spike-domain nature of processing, etc.

In order to achieve improved robustness and efficiency, it might be interesting to explore more bio-plausible spiking activation models134,135. In terms of learning, alternatives to backpropagation might be investigated with SNNs as well as SNN-ANN hybrids, such as the forward-forward method136, equilibrium propagation137, local learning approaches based on target propagation138. Another aspect of SNN training that is still under-explored is learning with a lesser amount of labeled data. To that end, investigating both novel network paradigms such as liquid neural networks139 as well as self-supervised learning approaches140 under the umbrella of neuromorphic algorithms holds immense potential. For example, a local learning rule was derived in ref. 141 combining Hebbian plasticity with a predictive form of plasticity, leading to invariant representations in deep neural network models.

Research on embodied AI has been exploding in the ANN domain142 due to the prevalence of robots in various household and industrial applications. The difference in viewpoint between existing datasets and an embodied agent creates unique challenges in applying off-the-shelf pre-trained algorithms for such tasks. Moreover, it remains to be seen how these approaches can be effectively incorporated into a cognitive pipeline with the SNNs, ANNs, and Hybrid architectures as ground pillars. With the proliferation of autonomous drones and the demand for low-power algorithms, this could be a direction worth pursuing. Further, a truly intelligent agent should be able to combine information from various sources and make appropriate decisions on the fly. As a result, it is important to explore large scale multimodal neuromorphic models incorporating event cameras, audio sensors, lidars, tactile sensors, etc. It is an open question of how to develop multi-modal architectures that can effectively fuse these diverse sources of data to perform autonomous intelligence. On top of that, since intelligent agents have to perform complex tasks in real-time, it might be useful to have some physical knowledge embedded in their learning, both for interpretability and reliability. In this context, physics-informed neural networks (PINNs)143,144 have been gaining popularity in recent times. However, such approaches are still in their nascent stage and the marriage between these networks and neuromorphic algorithms can be promising. In addition, with emerging applications where distributed intelligence plays a key role (e.g., a swarm of drones145), exploring and employing the right kind of learning algorithms, neural network architectures, and communication techniques is essential. Furthermore, as robots become more pervasive in our day-to-day lives, human-robot interactions will become critical. To that end, human-in-the-loop learning146 for future neuromorphic systems might be a promising avenue to explore.

The growing interest in SNN-ANN hybrid models presents exciting opportunities, yet their success relies on hardware that can efficiently integrate synchronous ANN and event-driven SNN computations. While early efforts toward developing platforms capable of supporting hybrid networks have emerged101,105, research in this direction is still limited. A synergistic evolution of algorithms and hardware will be key to realizing efficient and scalable hybrid systems35,36.

Although non-volatile memories (NVMs) like RRAM and PCM hold promise beyond their use as digital memories147, their use as analog synaptic devices presents challenges such as non-linear and asymmetric conductance updates, limited dynamic range, device variability, and retention-endurance trade-offs148,149. While in-memory computing has shown promise for mitigating memory bottlenecks, most implementations target dense workloads. Event-driven IMC architectures tailored for SNNs could greatly enhance the energy efficiency of hybrid systems150. Further improvements can be achieved by reducing reliance on energy-hungry ADCs151 and expanding analog computation beyond memory arrays to entire neuronal operations, provided precision and noise are addressed through hardware-in-the-loop training33,94,152. Supporting both backpropagation and local SNN learning on hardware is also essential for enabling online adaptation in resource-constrained environments.

Emerging approaches such as 3D integration and chiplet-based architectures offer promising pathways for scalable neuromorphic design. 3D stacking reduces interconnect latency and improves density, critical for maintaining temporal precision in SNNs153,154,155. Chiplet-based designs enable flexible integration of heterogeneous components, including analog IMC and digital logic156,157, beneficial for hybrid ANN-SNN platforms. However, these systems demand specialized EDA tools to handle the thermal and power complexities introduced by such heterogeneous, tightly coupled designs.

During scaling, communication becomes a dominant energy and latency bottleneck for systems designed for both ANNs and SNNs. Additionally, hybrid systems demand communication protocols capable of dynamically adapting to both spike-based and dense traffic patterns. The development of cross-domain Networks-on-Chip (NoCs) and scheduling mechanisms that can seamlessly switch between the varying ANN and SNN communication requirements will be crucial for scaling hybrid accelerators. Finally, progress in compiler and mapping toolchains is essential, as current frameworks lack support for the heterogeneous nature of hybrid networks158,159. Future compilers should automate partitioning, scheduling, and code generation across heterogeneous hardware substrate.

Addressing these challenges will require a co-design approach that spans devices, circuits, architecture, and algorithms. In addition, enabling widespread real-world deployment will require addressing practical concerns such as cost-effective and accessible hardware fabrics, ease of programmability and integration, and mature software toolchains. A holistic solution could unlock the potential of SNN-ANN hybrids, paving the way for energy-efficient, scalable, and adaptable neuromorphic systems for future AI workloads.

Conclusion

This article highlights the promise of neuromorphic computing for advancing artificial intelligence, especially in resource-constrained domains such as robotics and edge devices. Vision-based drone navigation (VDN) serves as a representative application to assess current neuromorphic approaches and to identify future research opportunities. Although current neuromorphic implementations have achieved encouraging results in VDN, several challenges remain in scaling these systems to more complex and diverse tasks. This article underscores the transformative potential of neuromorphic computing in advancing artificial intelligence, particularly in resource-constrained environments such as robotics and edge devices. Vision-based drone navigation (VDN) is considered as an exemplary application driver to evaluate current methods and discuss potential future research. While current implementations have demonstrated promising results for the VDN task, there remain notable challenges in scaling these systems for broader, more complex applications. The integration of bio-inspired algorithms with specialized neuromorphic hardware offers a pathway toward achieving brain-like efficiency, low latency, and adaptive capabilities that surpass traditional von Neumann architectures. To fully realize this potential, future research should prioritize the co-design of algorithms and hardware, the development of scalable large-scale neural networks, and the establishment of standardized benchmarks for evaluation. While neuromorphic systems have not yet demonstrated clear superiority over conventional machine learning in mainstream applications, ongoing progress in both hardware and algorithms suggests that they could play a pivotal role in bridging the gap between biological intelligence and artificial systems. Ultimately, continued interdisciplinary efforts are essential to realize the long-term goal of creating truly brain-inspired, autonomous, and intelligent machines.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Fiorino, A. et al. Parallelized, real-time, metabolic-rate measurements from individual drosophila. Sci. Rep. 8, 14452 (2018).

Li, D., Chen, X., Becchi, M. & Zong, Z. Evaluating the energy efficiency of deep convolutional neural networks on cpus and gpus. In 2016 IEEE international conferences on big data and cloud computing (BDCloud), social computing and networking (SocialCom), sustainable computing and communications (SustainCom)(BDCloud-SocialCom-SustainCom), 477–484 (IEEE, 2016).

Gholami, A. et al. A survey of quantization methods for efficient neural network inference. Low-power computer vision. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 291–326 (2022).

Liang, T., Glossner, J., Wang, L., Shi, S. & Zhang, X. Pruning and quantization for deep neural network acceleration: A survey. Neurocomputing 461, 370–403 (2021).

Howard, A. et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 1314–1324 (2019).

Jordan, M. I. Serial order: A parallel distributed processing approach. In Advances in psychology, 121, 471–495 (Elsevier, 1997).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Graves, A., Mohamed, A.-r. & Hinton, G. Speech recognition with deep recurrent neural networks. In 2013 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing, 6645–6649 (Ieee, 2013).

Mead, C. Neuromorphic engineering: In memory of misha mahowald. Neural Comput. 35, 343–383 (2023).

Maass, W. Networks of spiking neurons: the third generation of neural network models. Neural Netw. 10, 1659–1671 (1997). This seminal paper introduces spiking neurons as the third generation of neural network models, highlighting their superior computational power and biological realism.

Roy, K., Jaiswal, A. & Panda, P. Towards spike-based machine intelligence with neuromorphic computing. Nature 575, 607–617 (2019).

Frenkel, C. Sparsity provides a competitive advantage. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 742–743 (2021).

Ponghiran, W. & Roy, K. Spiking neural networks with improved inherent recurrence dynamics for sequential learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 36, 8001–8008 (2022).

Rathi, N. & Roy, K. Diet-snn: A low-latency spiking neural network with direct input encoding and leakage and threshold optimization. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems (2021).

Zheng, H., Wu, Y., Deng, L., Hu, Y. & Li, G. Going deeper with directly-trained larger spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 35, 11062–11070 (2021).

Chowdhury, S. S., Rathi, N. & Roy, K. One timestep is all you need: Training spiking neural networks with ultra low latency. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.05929 (2021).

Lichtsteiner, P., Posch, C. & Delbruck, T. A 128 × 128 120 db 15μs latency asynchronous temporal contrast vision sensor. IEEE J. Solid-state Circuits 43, 566–576 (2008).

Lee, C., Kosta, A. K. & Roy, K. Fusion-flownet: Energy-efficient optical flow estimation using sensor fusion and deep fused spiking-analog network architectures. In 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 6504–6510 (IEEE, 2022). A hybrid spiking architecture that achieves energyefficient optical flow estimation through event-frame sensor fusion.

Lee, C. et al. Spike-flownet: event-based optical flow estimation with energy-efficient hybrid neural networks. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 366–382 (Springer, 2020).

Zhu, R.-J., Zhao, Q., Li, G. & Eshraghian, J. SpikeGPT: Generative pre-trained language model with spiking neural networks. Transactions on Machine Learning Research https://openreview.net/forum?id=gcf1anBL9e (2024).

Yin, B., Corradi, F. & Bohté, S. M. Accurate and efficient time-domain classification with adaptive spiking recurrent neural networks. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 905–913 (2021).

Luo, Y. et al. Eeg-based emotion classification using spiking neural networks. IEEE Access 8, 46007–46016 (2020).

Mead, C. Neuromorphic electronic systems. Proc. IEEE 78, 1629–1636 (1990).

Mahowald, M. & Douglas, R. A silicon neuron. Nature 354, 515–518 (1991).

Mahowald, M. & Mead, C. The silicon retina. An Analog VLSI System for Stereoscopic Vision 4–65 (1994). This pioneering work introduces the silicon retina, an analog VLSI system that emulates biological visual processing for low-power, high-speed vision.

Akopyan, F. et al. Truenorth: Design and tool flow of a 65 mw 1 million neuron programmable neurosynaptic chip. IEEE Trans. Computer-aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 34, 1537–1557 (2015).

Davies, M. et al. Loihi: A neuromorphic manycore processor with on-chip learning. Ieee Micro. 38, 82–99 (2018).

Furber, S. B., Galluppi, F., Temple, S. & Plana, L. A. The spinnaker project. Proc. IEEE 102, 652–665 (2014).

Benjamin, B. V. et al. Neurogrid: A mixed-analog-digital multichip system for large-scale neural simulations. Proc. IEEE 102, 699–716 (2014). This work presents a mixed-analog-digital multichip system that uses analog circuits for energy-efficient neuron/synapse emulation and digital routing for communication, enabling real-time simulation of millionneuron networks at 1,000 × lower power than conventional approaches.

Moradi, S., Qiao, N., Stefanini, F. & Indiveri, G. A scalable multicore architecture with heterogeneous memory structures for dynamic neuromorphic asynchronous processors (dynaps). IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 12, 106–122 (2017).

Agrawal, A. et al. Impulse: A 65-nm digital compute-in-memory macro with fused weights and membrane potential for spike-based sequential learning tasks. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Lett. 4, 137–140 (2021).

Sharma, D., Negi, S., Dutta, T., Agrawal, A. & Roy, K. Spidr: A reconfigurable digital compute-in-memory spiking neural network accelerator for event-based perception. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.02854 (2024).

Kim, S. et al. Neuro-cim: A 310.4 tops/w neuromorphic computing-in-memory processor with low wl/bl activity and digital-analog mixed-mode neuron firing. In 2022 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits (VLSI Technology and Circuits), 38–39 (IEEE, 2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Aa 22nm 0.43 pj/sop sparsity-aware in-memory neuromorphic computing system with hybrid spiking and artificial neural network and configurable topology. In 2023 IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference (CICC), 1–2 (IEEE, 2023).

Kim, S. et al. C-dnn: A 24.5-85.8 tops/w complementary-deep-neural-network processor with heterogeneous cnn/snn core architecture and forward-gradient-based sparsity generation. In 2023 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), 334–336 (IEEE, 2023).

Chang, M. et al. A 73.53 tops/w 14.74 tops heterogeneous rram in-memory and sram near-memory soc for hybrid frame and event-based target tracking. In 2023 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), 426–428 (IEEE, 2023).

Bartolozzi, C., Indiveri, G. & Donati, E. Embodied neuromorphic intelligence. Nat. Commun. 13, 1024 (2022).

Pham, M. D., D’Angiulli, A., Dehnavi, M. M. & Chhabra, R. From brain models to robotic embodied cognition: How does biological plausibility inform neuromorphic systems? Brain Sci. 13, 1316 (2023).

Brandli, C., Berner, R., Yang, M., Liu, S.-C. & Delbruck, T. A 240 × 180 130 db 3 μs latency global shutter spatiotemporal vision sensor. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 49, 2333–2341 (2014).

Son, B. et al. 4.1 a 640 × 480 dynamic vision sensor with a 9μm pixel and 300meps address-event representation. In 2017 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), 66–67 (2017).

Finateu, T. et al. 5.10 a 1280 × 720 back-illuminated stacked temporal contrast event-based vision sensor with 4.86 μm pixels, 1.066 geps readout, programmable event-rate controller and compressive data-formatting pipeline. In 2020 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference-(ISSCC), 112–114 (IEEE, 2020).

Kodama, K. et al. 1.22 μm 35.6 mpixel rgb hybrid event-based vision sensor with 4.88 μm-pitch event pixels and up to 10k event frame rate by adaptive control on event sparsity. In 2023 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), 92–94 (IEEE, 2023).

Gallego, G. et al. Event-based vision: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 154–180 (2020).

Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R. & Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 28 (2015).

Avola, D. et al. Ms-faster r-cnn: Multi-stream backbone for improved faster r-cnn object detection and aerial tracking from uav images. Remote Sens. 13, 1670 (2021).

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.02767 (2018).

Touvron, H. et al. Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In International conference on machine learning, 10347–10357 (PMLR, 2021).

Carion, N. et al. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In European conference on computer vision, 213–229 (Springer, 2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 10012–10022 (2021).

Zhu, A., Yuan, L., Chaney, K. & Daniilidis, K. Ev-flownet: Self-supervised optical flow estimation for event-based cameras. In Proceedings of Robotics: Science and Systems (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 2018).

Zhu, A. Z., Yuan, L., Chaney, K. & Daniilidis, K. Unsupervised event-based learning of optical flow, depth, and egomotion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 989–997 (2019).

Alonso, I. & Murillo, A. C. Ev-segnet: Semantic segmentation for event-based cameras. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 0–0 (2019).

Hodge, V. J., Hawkins, R. & Alexander, R. Deep reinforcement learning for drone navigation using sensor data. Neural Comput. Appl. 33, 2015–2033 (2021).

Andersen, K. F., Pham, H. X., Ugurlu, H. I. & Kayacan, E. Event-based navigation for autonomous drone racing with sparse gated recurrent network. In 2022 European Control Conference (ECC), 1342–1348 (IEEE, 2022).

Dalgaty, T. et al. Hugnet: Hemi-spherical update graph neural network applied to low-latency event-based optical flow. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 3953–3962 (2023).

Schaefer, S., Gehrig, D. & Scaramuzza, D. Aegnn: Asynchronous event-based graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 12371–12381 (2022).

Yang, Y., Kneip, A. & Frenkel, C. Evgnn: An event-driven graph neural network accelerator for edge vision. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Artif. Intell. 2, 37–50 (2025).

Jeziorek, K., Wzorek, P., Blachut, K., Pinna, A. & Kryjak, T. Embedded graph convolutional networks for real-time event data processing on soc fpgas. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.07318 (2024).

Rathi, N., Srinivasan, G., Panda, P. & Roy, K. Enabling deep spiking neural networks with hybrid conversion and spike timing dependent backpropagation. In International Conference on Learning Representations https://openreview.net/forum?id=B1xSperKvH (2020).

Neftci, E. O., Mostafa, H. & Zenke, F. Surrogate gradient learning in spiking neural networks. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 36, 61–63 (2019).

Cao, Y., Chen, Y. & Khosla, D. Spiking deep convolutional neural networks for energy-efficient object recognition. Int. J. Computer Vis. 113, 54–66 (2015).

Diehl, P. U. et al. Fast-classifying, high-accuracy spiking deep networks through weight and threshold balancing. In 2015 International joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN), 1–8 (ieee, 2015).

Sengupta, A., Ye, Y., Wang, R., Liu, C. & Roy, K. Going deeper in spiking neural networks: Vgg and residual architectures. Front. Neurosci. 13, 95 (2019).

Kosta, A. K. & Roy, K. Adaptive-spikenet: event-based optical flow estimation using spiking neural networks with learnable neuronal dynamics. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 6021–6027 (IEEE, 2023). This work introduces a fully-spiking neural network with learnable neuronal dynamics to address the spike vanishing problem, enabling efficient and accurate event-based optical flow estimation that outperforms similarly sized ANNs in both accuracy and energy efficiency.

Huh, D. & Sejnowski, T. J. Gradient descent for spiking neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 1433–1443 (2018).

Lee, C., Sarwar, S. S., Panda, P., Srinivasan, G. & Roy, K. Enabling spike-based backpropagation for training deep neural network architectures. Front. Neurosci. 14 (2020).

Zenke, F. & Ganguli, S. Superspike: Supervised learning in multilayer spiking neural networks. Neural Comput. 30, 1514–1541 (2018).

Shrestha, S. B. & Orchard, G. Slayer: Spike layer error reassignment in time. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 1412–1421 (2018).

Wu, Y., Deng, L., Li, G., Zhu, J. & Shi, L. Spatio-temporal backpropagation for training high-performance spiking neural networks. Front. Neurosci. 12, 331 (2018).

Chowdhury, S. S., Rathi, N. & Roy, K. Towards ultra low latency spiking neural networks for vision and sequential tasks using temporal pruning. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 709–726 (Springer, 2022). A comprehensive overview of neuromorphic computing, outlining how spike-based architectures can enable energy-efficient machine intelligence.

Kim, Y. & Panda, P. Revisiting batch normalization for training low-latency deep spiking neural networks from scratch. Front. Neurosci. 15, 773954 (2021).

Datta, G., Liu, Z. & Beerel, P. A. Hoyer regularizer is all you need for ultra low-latency spiking neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.10170 (2022).

Suetake, K., Ikegawa, S.-i, Saiin, R. & Sawada, Y. S3nn: Time step reduction of spiking surrogate gradients for training energy efficient single-step spiking neural networks. Neural Netw. 159, 208–219 (2023).

Shen, S. et al. Evolutionary spiking neural networks: a survey. J. Membrane Comput. 1–12 (2024).

Kim, J., Kim, H., Huh, S., Lee, J. & Choi, K. Deep neural networks with weighted spikes. Neurocomputing 311, 373–386 (2018).

Park, S., Kim, S., Choe, H. & Yoon, S. Fast and efficient information transmission with burst spikes in deep spiking neural networks. In 2019 56th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), 1–6 (IEEE, 2019).

Park, S., Kim, S., Na, B. & Yoon, S. T2fsnn: Deep spiking neural networks with time-to-first-spike coding. In 2020 57th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), 1–6 (2020).

Schnider, Y. et al. Neuromorphic optical flow and real-time implementation with event cameras. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 4129–4138 (2023).

Liu, M. & Delbruck, T. Edflow: Event driven optical flow camera with keypoint detection and adaptive block matching. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 32, 5776–5789 (2022).

Zhu, A. Z. et al. The multivehicle stereo event camera dataset: An event camera dataset for 3d perception. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 3, 2032–2039 (2018).

Aydin, A., Gehrig, M., Gehrig, D. & Scaramuzza, D. A hybrid ann-snn architecture for low-power and low-latency visual perception. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 5701–5711 (2024).

Nagaraj, M., Liyanagedera, C. M. & Roy, K. Dotie-detecting objects through temporal isolation of events using a spiking architecture. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 4858–4864 (IEEE, 2023).

Ankit, A., Sengupta, A., Panda, P. & Roy, K. Resparc: A reconfigurable and energy-efficient architecture with memristive crossbars for deep spiking neural networks. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Design Automation Conference 2017, 1–6 (2017).

Yan, B. et al. Rram-based spiking nonvolatile computing-in-memory processing engine with precision-configurable in situ nonlinear activation. In 2019 Symposium on VLSI Technology, T86–T87 (IEEE, 2019).

Wan, W. et al. 33.1 a 74 tmacs/w cmos-rram neurosynaptic core with dynamically reconfigurable dataflow and in-situ transposable weights for probabilistic graphical models. In 2020 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference-(ISSCC), 498–500 (IEEE, 2020).

Agrawal, A., Ankit, A. & Roy, K. Spare: Spiking neural network acceleration using rom-embedded rams as in-memory-computation primitives. IEEE Trans. Computers 68, 1190–1200 (2018).

Dalgaty, T. et al. Mosaic: in-memory computing and routing for small-world spike-based neuromorphic systems. Nat. Commun. 15, 142 (2024).

Bohnstingl, T., Pantazi, A. & Eleftheriou, E. Accelerating spiking neural networks using memristive crossbar arrays. In 2020 27th IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS), 1–4 (IEEE, 2020).

Rathi, N. et al. Exploring neuromorphic computing based on spiking neural networks: Algorithms to hardware. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–49 (2023).

Chakraborty, I., Jaiswal, A., Saha, A., Gupta, S. & Roy, K. Pathways to efficient neuromorphic computing with non-volatile memory technologies. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 021308 (2020).

Tuma, T., Pantazi, A., Le Gallo, M., Sebastian, A. & Eleftheriou, E. Stochastic phase-change neurons. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 693–699 (2016).

Saxena, U. & Roy, K. Partial-sum quantization for near adc-less compute-in-memory accelerators. In 2023 IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design (ISLPED), 1–6 (IEEE, 2023).

Apolinario, M. P., Kosta, A. K., Saxena, U. & Roy, K. Hardware/software co-design with adc-less in-memory computing hardware for spiking neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computing (2023).

Chen, P., Wu, M., Ma, Y., Ye, L. & Huang, R. Rimac: An array-level adc/dac-free reram-based in-memory dnn processor with analog cache and computation. In Proceedings of the 28th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference, 228–233 (2023).

Chakraborty, I., Ali, M. F., Kim, D. E., Ankit, A. & Roy, K. Geniex: A generalized approach to emulating non-ideality in memristive xbars using neural networks. In 2020 57th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), 1–6 (IEEE, 2020).

Indiveri, G. et al. Neuromorphic silicon neuron circuits. Front. Neurosci. 5, 73 (2011).

Lee, D. & Roy, K. Area efficient rom-embedded sram cache. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 21, 1583–1595 (2012).

Lee, D., Fong, X. & Roy, K. R-mram: A rom-embedded stt mram cache. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 34, 1256–1258 (2013).

D’Agostino, S. et al. Denram: neuromorphic dendritic architecture with rram for efficient temporal processing with delays. Nat. Commun. 15, 3446 (2024).

Basu, A., Deng, L., Frenkel, C. & Zhang, X. Spiking neural network integrated circuits: A review of trends and future directions. In 2022 IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference (CICC), 1–8 (IEEE, 2022).

Orchard, G. et al. Efficient neuromorphic signal processing with loihi 2. In 2021 IEEE Workshop on Signal Processing Systems (SiPS), 254–259 (IEEE, 2021).

Frenkel, C. & Indiveri, G. Reckon: A 28nm sub-mm2 task-agnostic spiking recurrent neural network processor enabling on-chip learning over second-long timescales. In 2022 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), 65, 1–3 (IEEE, 2022).

Huo, D. et al. Anp-g: A 28nm 1.04 pj/sop sub-mm2 spiking and back-propagation hybrid neural network asynchronous olfactory processor enabling few-shot class-incremental on-chip learning. In 2023 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits (VLSI Technology and Circuits), 1–2 (IEEE, 2023).

Zhang, J. et al. 22.6 anp-i: A 28nm 1.5 pj/sop asynchronous spiking neural network processor enabling sub-o. 1 μj/sample on-chip learning for edge-ai applications. In 2023 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), 21–23 (IEEE, 2023).

Deng, L. et al. Tianjic: A unified and scalable chip bridging spike-based and continuous neural computation. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 55, 2228–2246 (2020).

Zhao, R. et al. A framework for the general design and computation of hybrid neural networks. Nat. Commun. 13, 3427 (2022).

Woźniak, S., Pantazi, A., Bohnstingl, T. & Eleftheriou, E. Deep learning incorporating biologically inspired neural dynamics and in-memory computing. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 325–336 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. A system hierarchy for brain-inspired computing. Nature 586, 378–384 (2020).

Painkras, E. et al. Spinnaker: A 1-w 18-core system-on-chip for massively-parallel neural network simulation. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 48, 1943–1953 (2013).

Manohar, R. Hardware/software co-design for neuromorphic systems. In 2022 IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference (CICC), 01–05 (IEEE, 2022).

Narayanan, S., Taht, K., Balasubramonian, R., Giacomin, E. & Gaillardon, P.-E. Spinalflow: An architecture and dataflow tailored for spiking neural networks. In 2020 ACM/IEEE 47th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA), 349–362 (IEEE, 2020).

Davies, M. Benchmarks for progress in neuromorphic computing. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 386–388 (2019).

Yik, J. et al. The neurobench framework for benchmarking neuromorphic computing algorithms and systems. Nat. Commun. 16, 1545 (2025).

Liu, Q., Pineda-Garcia, G., Stromatias, E., Serrano-Gotarredona, T. & Furber, S. B. Benchmarking spike-based visual recognition: a dataset and evaluation. Front. Neurosci. 10, 496 (2016).

Amir, A. et al. A low power, fully event-based gesture recognition system. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 7243–7252 (2017).

Miao, S. et al. Neuromorphic vision datasets for pedestrian detection, action recognition, and fall detection. Front. Neurorobotics 13, 38 (2019).

Dupeyroux, J., Stroobants, S. & De Croon, G. C. A toolbox for neuromorphic perception in robotics. In 2022 8th International Conference on Event-Based Control, Communication, and Signal Processing (EBCCSP), 1–7 (IEEE, 2022).

Joshi, A., Ponghiran, W., Kosta, A., Nagaraj, M. & Roy, K. Fedora: A flying event dataset for reactive behavior. In 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 5859–5866 (IEEE, 2024).

Kosta, A. K. et al. Toffe–temporally-binned object flow from events for high-speed and energy-efficient object detection and tracking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12482 (2025).

Steffen, L. et al. Benchmarking highly parallel hardware for spiking neural networks in robotics. Front. Neurosci. 15, 667011 (2021).

Gewaltig, M.-O. & Diesmann, M. Nest (neural simulation tool). Scholarpedia 2, 1430 (2007).

Yavuz, E., Turner, J. & Nowotny, T. Genn: a code generation framework for accelerated brain simulations. Sci. Rep. 6, 18854 (2016).

Müller-Cleve, S. F. et al. Braille letter reading: A benchmark for spatio-temporal pattern recognition on neuromorphic hardware. Front. Neurosci. 16, 951164 (2022).

Parker, L., Chance, F. & Cardwell, S. Benchmarking a bio-inspired snn on a neuromorphic system. In Proceedings of the 2022 Annual Neuro-Inspired Computational Elements Conference, 63–66 (2022).

Moitra, A. et al. Spikesim: An end-to-end compute-in-memory hardware evaluation tool for benchmarking spiking neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems (2023).

Das, D. & Fong, X. A unified evaluation framework for spiking neural network hardware accelerators based on emerging non-volatile memory devices. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.19139 (2024).

Negi, S., Sharma, D., Kosta, A. K. & Roy, K. Best of both worlds: Hybrid snn-ann architecture for event-based optical flow estimation. In 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2696–2703 (2024).

Stewart, K. M. & Neftci, E. O. Meta-learning spiking neural networks with surrogate gradient descent. Neuromorphic Comput. Eng. 2, 044002 (2022).

Schmidgall, S. & Hays, J. Meta-spikepropamine: learning to learn with synaptic plasticity in spiking neural networks. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1183321 (2023).

Wang, R. et al. Test-time training on video streams. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 26, 1–29 (2025).

Patel, D., Hazan, H., Saunders, D. J., Siegelmann, H. T. & Kozma, R. Improved robustness of reinforcement learning policies upon conversion to spiking neuronal network platforms applied to atari breakout game. Neural Netw. 120, 108–115 (2019).

Naya, K., Kutsuzawa, K., Owaki, D. & Hayashibe, M. Spiking neural network discovers energy-efficient hexapod motion in deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Access 9, 150345–150354 (2021).

Tang, G., Kumar, N., Yoo, R. & Michmizos, K. Deep reinforcement learning with population-coded spiking neural network for continuous control. In Conference on Robot Learning, 2016–2029 (PMLR, 2021).

Hodgkin, A. L. & Huxley, A. F. Currents carried by sodium and potassium ions through the membrane of the giant axon of loligo. J. Physiol. 116, 449–472 (1952).

Izhikevich, E. M. Simple model of spiking neurons. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 14, 1569–1572 (2003).

Hinton, G. The forward-forward algorithm: Some preliminary investigations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.13345 (2022).

Scellier, B. & Bengio, Y. Equilibrium propagation: Bridging the gap between energy-based models and backpropagation. Front. Computational Neurosci. 11, 24 (2017).