Abstract

Maximizing evaporation performance is crucial for advancing interfacial steam generation (ISG) systems, yet the potential of Joule heating for this remains underexplored. Here, we present a high-performance interfacial evaporator that leverages Joule heating-based evaporation to achieve very high water evaporation rates. The system integrates thiol-functionalized glassy carbon sponge with ultra-low electrical resistance ( ~ 0.75 Ω) to maximize joule heating. Under 1 sun illumination and a 37 W power input, the evaporator achieves an evaporation rate of ~205 kg m⁻²h⁻¹, reaching surface temperatures of 97 °C at the air–water interface. With 3.5 wt% saltwater, joule heating alone produces 11.86 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ , and combined solar (1sun)-electrothermal heating increases this to ~18 kg m⁻²h⁻¹. This work showcases the role of high electrical power in interfacial evaporation, offering a pathway for rapid and high-performance steam generation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing global water crisis due to population growth and climate change calls for innovative and energy-efficient water purification technologies1,2. Existing seawater desalination technologies like reverse osmosis are extensively implemented across the globe but face challenges with high energy consumption, substantial operational expenses, and brine management problems, limiting their implementation in resource-poor areas3. Interfacial solar steam generation (ISSG) has attracted great attention as a new alternative which can achieve high-energy utilization by transferring heat to water interface rather than heating an entire bulk space. Nonetheless, while ISSG has such promise, in reality, its actual deployment is currently limited by dependence on weather, salt build-up, and low efficiency in terms of harvested water rates that restrict its continuous and large-scale use4. Addressing these limitations is vital for practical applications of these steam generators5.

To mitigate the intermittent nature of solar-driven evaporation, various strategies have been developed. These include thermal energy storage with phase change materials (PCMs) and Joule heating-assisted (JHA) ISSG systems, both of which provide supplemental energy sources beyond direct solar absorption6,7. Among these, JHA-ISSG has demonstrated much better performance, achieving extraordinary evaporation rates at low input voltages8,9. Joule heating enhances interfacial evaporation by directly converting electrical energy into heat, even in the absence of strong sunlight. The synergistic combination of photothermal and electrothermal heating has the potential to exceed the evaporation rate limits imposed by solar illumination alone, enabling continuous steam generation even in low-light conditions such as nighttime or cloudy weather. However, despite the promise of JHA-ISSG, reports focusing on maximizing steam generation performance through electrothermal heating remain limited.

In particular, most previous studies have not fully explored strategies to maximize the electrothermal heating performance for achieving enhanced interfacial evaporation rates. The evaporation performance of JHA-ISSG systems is largely governed by the intrinsic material properties, which must simultaneously provide high electrical conductivity for Joule heating, strong photothermal absorption, effective thermal insulation, and efficient water transport. To date, only a few JHA-ISSG devices have succeeded in achieving evaporation rates exceeding 20 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ under 1 sun illumination and low-voltage operation ( < 5 V), highlighting the need for materials and system designs capable of further maximizing evaporation performance10,11. In JHA-ISSG systems, the electrical resistance of the steam generator is a key determinant of Joule heating performance and overall electrothermal energy conversion. In this regard, carbonaceous materials, widely used as electrodes for electrochemical systems, are excellent candidates due to their high electrical conductivity, low resistance and intrinsic broadband light absorption making them highly effective for both photothermal and electrothermal energy conversion. For instance, in our previous work, a carbon cloth-based JHA-ISSG demonstrated excellent synergistic steam generation under 1 sun illumination and input voltages of 1–3 V12. However, its two-dimensional architecture limited the steam generation rate due to inefficient heat localization and water transport. These limitations highlight the need for novel system designs, particularly three-dimensional (3D) high-surface-area carbonaceous electrode-based steam generators that can simultaneously optimize photothermal and electrothermal heating to maximize evaporation performance.

In this study, a thiol-functionalized glassy carbon sponge (GSt)-based interfacial steam generator specifically designed to maximize electrothermal heating performance is proposed for enhanced steam generation performance. The GSt-based evaporator features a highly porous, thermally insulating, and conductive 3D architecture which simultaneously optimizes light absorption and Joule heating efficiency. Under 1 sun illumination and a 5 V (37 W) input voltage, the system achieves an unprecedented evaporation rate of 205 kg m⁻²h⁻¹, far surpassing previously reported JHA-ISSG devices. This exceptional performance is attributed to the low electrical resistance ( ~ 0.75 Ω) of the GSt-M structure, which enables rapid electrothermal heating, reaching 97 °C at the air–water interface, thereby accelerating water evaporation. The system also demonstrates exceptional standalone Joule heating performance (11.86 kg m⁻²h⁻¹) with 3.5 wt% salt solution and synergistic photothermal-electrothermal evaporation ( ~ 18 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ under 1 sun with an 11 W input), showcasing its robustness and all-day applicability. Overall, this work highlights the underexplored role of high electrical power in enhancing electrothermal interfacial evaporation and provides a pathway toward next-generation water purification technologies.

Results and discussion

Joule heating-based steam generator and characterization

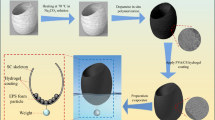

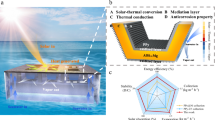

The schematic of the proposed steam generation device is illustrated in Fig. 1a. The device incorporates glassy carbon (GS) as the core material due to its unique combination of properties: broadband light absorption, intrinsically low thermal conductivity, and high electrical conductivity5. These features collectively enable efficient interfacial evaporation of water molecules at the air-water interface. The mechanical strength and chemical stability of glassy carbon ensure prolonged and practical utilization of the device, enhancing its applicability in all-day all-weather conditions.

a Schematic illustration of the joule heating assisted interfacial solar steam generation device. b, c SEM images of GS at different magnifications. d, e SEM images of GSt at different magnifications. f High-resolution XPS spectra of S2p in GSt. The raw data are shown in black, the fitted curve in red, and the background in green. Deconvoluted peaks are represented at 164.35 eV (dark blue) and 162.4 eV (teal). g XRD pattern of GS and GSt. h Raman spectra of GS and GSt.

Effective water transport is essential for achieving sustained and highly efficient SSG13. Among the various factors facilitating effective water transport, surface hydrophilicity plays a pivotal role14. A previous study reported that altering the surface properties of carbon-based materials through the introduction of thiol groups can transform their wetting characteristics from hydrophobic to hydrophilic15. This change is attributed to the incorporation of -SH functional groups, which bear similarities to sulfur analogs of hydroxyl or alcohol groups. Since pristine GS exhibits hydrophobic characteristics, a chemical modification process was employed to overcome this limitation, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Figure 1b–e presents Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images of both GS and GSt. The top view SEM images distinctly reveal the uniformity of the surfaces of GS and GSt, devoid of any discernible particles or contaminants. Notably, the carbon surfaces exhibit a multitude of macropores arranged in an ordered fashion. This macroporous structure is particularly well suited for efficient water transport. Capillary forces acting in the carbon framework draw water into the pores through surface tension, enabling continuous replenishment of water to the interface. As a result, water flows seamlessly and within the porous network. EDS selected area of GS in Supplementary Fig. 2 and GSt in Supplementary Fig. 3 show the uniform distribution of constituent elements, Carbon (C), Nitrogen (N), Oxygen (O), and Sulfur (S). Notably, the sulfur content in GSt increases from 0.48 wt % to 2.15 wt% after thiol functionalization. This demonstrates successful incorporation of -SH groups, which enhances water adsorption (Supplementary Figs. 2g and 3g). Figure 1f depicts the XPS spectrum of GS and GSt, showing the presence of Carbon, Oxygen, Nitrogen and additional Sulfur element in GSt which is assigned to thiol functionalization. Supplementary Fig. 4 shows the high-resolution spectra of C1s of GS and GSt which are deconvoluted into three different binding energies 284.5 eV, 286.3 eV 288.3 eV and 284.48 eV, 286.1 eV, and 288.4 eV respectively. The peak intensity at 284.5 and 284.48 eV are linked with sp2 hybridized C-C bond. The corresponding line position at 286.3 eV and 286.1 eV is assigned to the C-S bond, because the thiol characteristics peak comes from this binding energy due to sulfur atom on the carbon surface. The peak intensity at 288.4 eV and 288.3 eV is assigned to the carboxylic group. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows the high-resolution spectra of N1s spectrum which is deconvoluted into two different binding energies at 398. 1 eV, 402.2 eV for GS and 400.1 eV and 405.9 eV for GSt respectively. The peak intensity at 398.1 eV and 400.1 eV is assigned to the pyridine N and amine (-NH2) functional group respectively. This results from the reaction between thiol groups and certain nitrogen-containing compounds16. The peaks at 402.2 eV and 405.9 eV come from the various oxidized nitrogen species17. The N peak in the XPS spectrum of GSt is attributed to the thiol functionalization. The two distinct peaks in O1s spectra (Supplementary Fig. 6) correspond to the oxygen in the form of C = O and O-C-O components18. Figure 1f shows the high-resolution XPS peak of S2p of Gst. The absorbance peaks at 164.3 eV and 162.4 eV is due to the thiol functionalization (C-SH) onto the surface which corresponds to the S 2p1/2 and S 2p3/2, respectively. The effect of this chemical modification on surface wettability was assessed by contact angle (CA) measurements, as depicted in the Supplementary Fig. 7. GS exhibited a CA of roughly 130°, indicating its hydrophobic nature. Despite its porous structure, water molecules do not penetrate the GS surface. In contrast, GSt exhibits swift impregnation of water within a second, promptly wetting the surface. This underscores the surface modification induced by thiol functionalization makes the material to have superhydrophilicity in the material as also seen in Supplementary Fig. 8. The effect of thiol functionalization and hydrophilicity can be attributed to the interaction of –SH groups with water molecules via hydrogen bonding and dipole–dipole interactions. These polar interactions enhance the surface’s ability to adsorb water compared to the non-functionalized, non-polar carbon surface, which interacts only through weak van der Waals forces. This chemical modification is supported by the emergence of C–S bonds at ~286.1 eV in the C1s spectrum and S2p peaks at 162.4 and 164.3 eV in the XPS data, alongside the increase in sulfur content from 0.48 to 2.15 wt% observed in EDS. The enhanced water affinity leads to rapid and continuous water uptake into the porous GSt structure, promoting capillary-driven transport toward the evaporative interface.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was carried out to determine the crystal structure of GS, and GSt (Fig. 1g). The GS and GSt exhibit two Braggs diffraction peaks at an angle of 2Ө = 24.10o and 43.3o respectively. The first-order diffraction peak at 24.10o corresponds to the hkl index of the (002) plane, indicating a low graphitized amorphous carbon with an interlayer spacing of d002 = 1.88 Å. Similarly, the diffraction peak at 43.3o is assigned to the hkl index of (001) plane, representing the hexagonal graphite lattice with interlayer spacing of d100 = 1.12 Å19. It is observed that following functionalization, the intensity peak of Gst is reduced, confirming a reduction in Gst crystallinity structure. Raman spectroscopy is an important approach for the analysis of any disorder or surface modification in the sp2 carbon-carbon bonds. Carbon-based material commonly exhibits two primary peaks: D-band (1330 cm−1) and G-band (1580 cm−1). These peaks are associated with defects and graphitic structure, respectively, and the ratio of these two peaks is used to assess the efficacy of any chemical functionalization of the material. Figure 1h shows the Raman spectra of GS and GSt, in which two peaks are centered at 1351 cm−1 and 1593 cm−1, which are typical of graphitic carbon nanostructures. The peak at 1593 cm−1 (G band) corresponds to a graphite E2g mode and is connected to the vibration of sp2-bonded carbon atoms. The peak at 1351 cm-1 (D band) is associated with the vibrations of carbon atoms with dangling bonds in disordered graphite plane terminations. The intensity ratio (ID /IG) for GSt is 1.09, slightly greater than that of GS 1.0320,21. Upon thiol (-SH) functionalization on GS, the relative peak intensity of D band and G band is somewhat changed, demonstrating its structural modification.

Beyond the hydrophilic traits, the water transport capability to the GSt device has crucial influence on the SSG performance. The reduction of heat loss, particularly conductive heat loss to bulk water, is essential for effective heat localization at the air-water interface22. For this purpose, the ISSG device incorporates a melamine sponge as a water transport medium and for structural support. The highly porous and interconnected structure of melamine sponge enables efficient capillary-driven water transport to the evaporative surface, while its intrinsic hydrophilicity ensures continuous and uniform wetting (Supplementary Fig. 9). Its low thermal conductivity helps confine heat near the evaporation interface, thereby enhancing energy efficiency. Furthermore, melamine sponge is abundant, cost-effective, and exhibits excellent thermal and chemical stability, tolerating temperatures up to 250 °C as demonstrated in previous JHA device studies11. These combined properties make melamine sponge an ideal choice for the present system, and are the key reasons it was selected for use in the GSt-M evaporator. Supplementary Fig. 10 illustrates the rapid water transport and wettability of GSt-M. The amalgamation of GSt and melamine sponge facilitates the swift transport of bulk water to the upper surface, providing exceptional water transport capability. The light absorption characteristics of GSt were assessed through UV-VIS-NIR spectroscopy. As depicted in the Supplementary Fig. 11. Notably, the proposed GSt’s exhibits notable broadband absorption rate over the solar irradiation spectrum, boasting over 95% in the 250–2500 nm wavelength range. In the context of sustained operation of a desalination system, GSt’s stability under extreme conditions holds paramount importance. To address this concern, GSt was subjected to various severe test conditions, including strong acidity (pH = 1), strong alkalinity (pH = 14), elevated temperature (150 °C), and extreme cold (−80 °C) environments, as depicted in the Supplementary Fig. 12. GSt exhibits consistent stability for all the test conditions, revealing no signs of defects or physical damage. This resilience of GSt’s demonstrates its suitability as photothermal material for ISSG-based solar desalination, ensuring its long-term high performance even under extreme operational conditions.

Steam generation performance of GSt-M

Figure 2a illustrates the experimental setup employed for evaluating the evaporation performance of GSt-M evaporator. Copper tape, silver paste, and copper wires were strategically utilized to minimize external resistance during the supply of input power. As described in the method section, a specialized power supply was utilized for maximum input power in this experiment. In Fig. 2b, the evaporation rate of the GSt-M device under 1 sun illumination at input voltages (1-5 V) is presented. Under 1 sun illumination, the GSt-M device exhibits an evaporation performance of 2.66 kg m⁻²h⁻¹. With the introduction of additional input voltages (1 V-2 V), the evaporation rate experiences a substantial enhancement, increasing by 3.9 times to 8.84 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ and 12 times to 32.36 kg m⁻²h⁻¹, respectively. Further escalation of the input voltage leads to even more notable results, with the GSt-M device achieving evaporation rates of 78.2 kg m⁻²h⁻¹, 136.5 kg m⁻²h⁻¹, and 205 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ at 3 V, 4 V, and 5 V, respectively. These evaporation rates represent the highest reported in the literature to date (Supplementary Table 1). The steam generation process is vividly captured in Supplementary Movie 1 & 2, showcasing the unexpected steam generation capability of the device. These results are primarily attributed to the rapid heating enabled by the high input power delivered to the GSt-M device. This is evidenced by the attainment of steady-state surface temperatures reaching 93.9 °C and 95.9 °C within just 5 min of constant 1 sun illumination at input voltages of 4 V and 5 V, respectively. Tests above 5 V were not conducted, as the surface temperature plateaued near the boiling point (~98 °C). Furthermore, experiments with input voltages >3 V for long term operation necessitate a constant water supply in the bulk solution, affecting the suitability of the proposed GSt-M for joule heating-assisted ISSG devices in desalination applications. For a more comprehensive evaluation of the GSt-M’s evaporation performance, the evaporation rates of a purely electrothermal-based conditions were also investigated (Fig. 2d). At 1–2 V, surface temperatures of 45.3 °C and 76.5 °C yield moderate evaporation rates. At ≥3 V, however, Joule heating dominates, rapidly elevating the interface temperature and driving enhanced evaporation. Photothermal heating contributes noticeably only at low voltages, accounting for ~39.8% of the total evaporation at 1 V and ~29.9% at 2 V. Above this threshold, its contribution falls to 9% at 3 V and becomes nearly negligible at 4 V (0.66%) and 5 V (0.10%). This diminishing contribution is primarily due to the rapid and intense heat generation from Joule heating, which raises the surface temperature beyond 90 °C, thereby overshadowing the relatively slower photothermal heating response of the GSt material. Finally, Supplementary Fig. 13 presents the cyclic performance of GSt, confirming its ability to sustain repeated steam generation cycles.

a Optical images of the experimental setup used for evaporation performance testing. b Evaporation rates of the GSt-M device under different input voltages, with and without 1 sun illumination; error bars represent the standard error. c Surface temperature variations under similar conditions, with steady state surface temperature highlighted (black oval). d Infrared thermal images showing the surface temperatures of GSt after 10 min at different input voltages, with solar illumination (green box) and without solar illumination (red box).

Evaluation of GSt-M steam generation performance

The outstanding performance of the GSt-M device stems from the synergetic effect of photothermal and joule heating mechanisms, together enabling remarkable steam generation capabilities. This behavior is primarily facilitated by the inherently low thermal conductivities of GSt (0.20 W m−1 K−1) and melamine sponge (0.035 W m−1 K−1), which ensure effective thermal management and localized heat retention at the surface interface. This was visualized by the temporal evolution of surface temperature resulting from the photothermal heating of GSt under 1 sun illumination as methodically depicted in Supplementary Fig. 14. Initially, upon exposure to 1 sun illumination, the surface temperature experiences a rapid increase, reaching 35 °C (Supplementary Fig. 15). Subsequently, a consistent and controlled rise in temperature ensues, eventually peaking and stabilizing at 54 °C after a continuous 30 min exposure to 1 sun illumination (Supplementary Fig. 16). To probe the contribution of Joule heating, I–V measurements were performed under dry and immersed conditions (Fig. 3a). In both cases, the proposed GSt-M device exhibits linear responses with nearly identical electrical resistances (dry: 0.76 Ω, immersed in DI water: 0.75 Ω). This very low resistance value aligns with previous report showcasing high steam generation performance11. For instance, a MPC/cloth-F evaporator was reported with a resistance of 7.96 Ω, and stated the necessity of having resistance of the evaporator of similar range order to achieve high evaporation rates.

where V represents the input voltage in Volts and R denotes the resistance in ohms.

a Current–voltage (I–V) curves of the GSt-M device measured under input voltages ranging from 1 to 5 V. b Evaporation performance of the device as a function of input voltage and corresponding input power. Black squares indicate input power, red symbols represent evaporation rates without solar illumination, and blue symbols represent rates under 1 sun illumination. c Infrared thermal images showing surface temperatures of GSt after 2 min at different input voltages (1–5 V), without photothermal heating (left) and with photothermal heating (right).

Consequently, the input power experiences an exponential increase with input voltage and a subsequent increase in joule heating which can be defined as

Where; H is the amount of heat generated in Joules and t is the elapsed time the input voltage is applied in seconds. For example, at an input voltage of 5 V, the GSt-M device generates an input power of approximately 37 W (Supplementary Table 2). It should be noted that the goal of this work is maximizing joule heating-based performance, and therefore, an extremely high input power was utilized (Supplementary Note 1). The performance was also evaluated with a more conventional power supply for more robust performance evaluation (Supplementary Table 3).

The key advantage of the GSt-M device lies in its ability to sustain high input power and subsequent joule heating for long periods of time without structural-degradation. Infrared (IR) imaging was employed to evaluate this effect. Surface temperature increases rapidly with increasing input voltages (Fig. 3c). The surface temperature of GSt reaches 93.5 °C, 160 °C, and 170 °C within 120 seconds at input voltages of 3 V, 4 V, and 5 V, respectively. With increasing input voltages, the heating rate of surface temperature also increases, which may be attributed to enahnced electrical conductivity of GSt at high voltages. A similar trend is observed when photothermal heating under solar illumination is combined with joule heating at different input voltages. Within a minute, the surface temperature rapidly increases to 49 °C and 180 °C at input voltages of 1 V and 5 V, respectively. The thermal images further confirm nearly uniform heat distribution across the GSt surface, enabling heat localization at the evaporation interface. At voltages below 2.5 V, the rate of surface temperature increase is higher with the addition of 1 sun solar illumination. These differences are also evident in the final steady-state surface temperatures. The results highlight that the input power plays a crucial role in rapid and substantial heat generation, driving the synergetic electrothermal and photothermal-based evaporation. Supplementary Note 2 showcases the energy conversion efficiencies of GSt-M. The extraordinary evaporation rates are obtained utilizing the high input power but it also affects the energy conversion efficiencies of GSt-M device (Supplementary Table 2). For example, at an input voltage of 5 V, the GSt-M device achieves a high evaporation rate exceeding 200 kg m⁻²h⁻¹; however, the efficiency drops below 40%. This drop is primarily due to conductive heat losses through the metallic wires and connectors, which increase with thermal gradients and lead to non-evaporative dissipation. In addition, conductive loss to bulk water, convective and radiative losses also contribute to the inefficiency.

Radiation loss is governed by the Stefan–Boltzmann law and can be expressed as:

where ε is the surface emissivity, σ is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant, A is the surface area, Ts is the surface temperature, and Ta is the ambient temperature. Radiation losses increase at surface temperatures exceeding 90 °C. Similarly, convective heat loss can be described by:

where h is the convective heat transfer coefficient, which depends on ambient conditions. Collectively, these three loss mechanisms conduction, convection, and radiation are estimated to account for additional 15%, ultimately affecting the overall energy conversion efficiency despite the high evaporation output. Therefore, while such high evaporation performance highlights the extreme thermal robustness of the GSt-M device, sustained operation under ultra-high input power is not energy-efficient or sustainable for practical long-term applications. For such applications, a low input power shall be much more efficient and advisable. Nonetheless, the intrinsic thermal stability and structural integrity of GSt-M make it suitable for short-term, high-temperature processes such as rapid steam generation, surface sterilization, and thermal disinfection applications where material durability and thermal tolerance are more critical than overall efficiency.

Desalination test

The steam generation capacity of the GSt-M device, utilizing Joule heating, emphasizes its sustainability as a reliable solution for continuous freshwater production, irrespective of weather conditions. Figure 4a showcases the performance of the fabricated GSt-M device in evaporating saltwater. It is crucial to emphasize that, to ensure a consistent evaluation of evaporation performance across different power supply configurations, the desalination performance assessments were conducted under varied input power levels. Specifically, for the solar desalination experiments, a conventional DC power supply was employed, and the corresponding input power values used are detailed in Supplementary Table 3. Furthermore, we opted for low input power settings in solar desalination experiments to guarantee sustainable operations in diverse weather conditions, thereby reducing the necessity for frequent salt cleanup. Additionally, in solar desalination, our aim is to minimize the impact of electrothermal heating and emphasize photothermal heating for sustainable solar-driven desalination. Notably, for a 3.5 wt% salt solution, the GSt-M maintains a steady steam generation performance, achieving a high evaporation rate of 18 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ with a 11 W input power. It is worth highlighting that the GSt-M demonstrates efficient steam generation even at lower input power levels. The evaporation rates of 4.54 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ at ~0.4 W and 8.9 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ at ~2 W demonstrate the versatile and energy-efficient saltwater evaporation performance of the system. To assess its suitability as an all-day device, the Joule heating-assisted electrothermal performance of GSt was also examined. In the absence of photothermal heating, the GSt-M device can manage to evaporate saltwater at a rate of 11.86 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ at input voltage of 10 W. It implies that a solar still module employing the proposed GSt-M can operate efficiently without excessive reliance on intense solar radiation and weather conditions. In addition, the use of solar panels enables the use of green and energy source to achieve a completely renewable all-day desalination. Furthermore, the evaporation performance was also evaluated for salt water with different salinities, as shown in Fig. 4b. The GSt-M device demonstrates high steam generation performances even under highly saline conditions, including saltwater concentrations up to 20 wt%. Salt rejection is a critical challenge in practical interfacial solar steam generation (ISSG) systems where rapid saltwater influx and negative pressure at the air–water interface often lead to salt crystallization and surface fouling. The GSt-M device-maintained salt rejection for a long period in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution under 1 sun illumination, as evidenced by the absence of visible salt accumulation in Supplementary Fig. 17. This behavior is attributed to the porous and highly wettable structure of the GSt material, along with the superhydrophilic nature of both the GSt and the melamine sponge substrate. At higher concentrations such as 20 wt%, visible salt accumulation initiates within the first hour of operation due to accelerated crystallization at the air–water interface, which adversely affects long-term performance. Future work shall be focused on limiting salt accumulation through the development of gravity-assisted siphon driven systems capable of continuous salt removal, thereby enabling sustained performance across a wide range of salinities.

a Evaporation performance of the GSt-M device with and without 1 sun illumination at different input power levels for 3.5 wt% saltwater. b Evaporation rates under 1 sun illumination and 11 W input for saltwater solutions with various salinity. c Optical images of a conventional solar still and a GSt-M-integrated solar still (highlighted by the red dotted box) at 0 and 60 minutes of operation, showing evaporation performance under Joule heating (11 W) and photothermal heating (1 kW m⁻²).

To assess the practical applicability of the GSt-M device, an indoor test was conducted using a GSt-M module-based solar still prototype (Supplementary Fig. 18). Remarkably, within 5 min, water condensation was observed on the glass panel of the still, even though only a small module with a surface area of 5 cm² was used (Supplementary Fig. 19). For further assessment all-day applicability, the device was tested in pure joule heating mode (11 W) and under combined joule-photothermal heating (1 sun), and the results were compared with conventional bulk water solar still with only photothermal heating (1sun) as shown in Fig. 4c. In contrast to conventional bulk water heating solar still, the joule heating and photothermal heating of GSt generated enough steam to yield measurable condensed water samples. The condensed water samples were measured, and GSt at 11 W input wattage and 1 sun illumination could generate 0.8−1 mL/hr. GSt at 11 W could also generate clean water at a rate of 0.4 mL/hr with no condensed water samples obtained in bulk water based solar still. The temporal variation of bulk water temperature, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 20, provides valuable insights into the heating processes. During joule heating, the water temperature ranges from 25.8 °C to 49.9 °C. When the combined effect of photothermal and joule heating is applied, this range extends further, reaching temperatures between 25.8 °C and 59.9 °C. These findings further demonstrate the capability of GSt-M to elevate water temperatures, even during cloudy or off-sunshine hours. In contrast, the conventional solar still achieves a maximum water temperature of only 31.5 °C after 1 h of constant 1 sun illumination. Supplementary Fig. 21 illustrates the quality of the collected freshwater, evaluated using ICP-OES. Compared to seawater, the concentrations of all four primary ions (Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+) of the desalinated fresh water are reduced, meeting the World Health Organization (WHO) standards for ion concentrations in drinking water. These results demonstrate that the GSt-M device can reliably produce freshwater under both solar and hybrid solar–electrical operation, even in conditions of low or intermittent sunlight. For real-world deployment, the GSt-M is best suited for low-to-moderate power operation, where its indestructible material architecture offers long-term operational stability and improved energy efficiency. The fabrication of the GSt-M device is scalable and based on simple solution-based processes involving commercially available materials. This allows for the construction of large-area systems through modular assembly. Arrays of GSt-M units can be integrated in series or parallel configurations, depending on the application scale, supporting both decentralized, off-grid purification setups and integration into larger, centralized desalination infrastructures. Furthermore, the open-pore architecture, compatibility with hybrid solar–electrical inputs, and potential for passive or gravity-driven brine management enhance the adaptability of GSt-M for use in resource-limited or remote environments.

Conclusion

In this study, a robust and high-performance interfacial steam generator (GSt-M) is reported that is designed and utilized to maximize joule heating-based evaporation performance. For this, glassy carbon sponge (GS), a robust electrode material is utilized after thiol functionalization to modify its surface wettability from hydrophobic to hydrophilic and then coupled with melamine sponge for thermal localization and rapid water transport. The photothermal capability of GSt coupled with its joule heating capability achieved a water evaporation rate of ~205 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ under 1 sun illumination with extremely high input power of 37 W for short time experiments.. This performance is attributed to the low electrical resistance of GSt (~0.75 Ω) which generates heat with surface temperature reaching as high as 97 °C within minutes. The proposed GSt-M device can generate steam at high evaporation rates rapidly, demonstrating the synergetic photothermal and electrothermal capability of GSt. For checking the feasibility of all-day solar desalination application, the evaporation rates of GSt of salt water were evaluated with and without joule heating. The GSt-M device achieves an evaporation rate of ~18 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ under 1 sun illumination and 11 W input voltage. In addition, an excellent evaporation rate of 11.86 kg m⁻²h⁻¹ is achieved without photothermal heating, showcasing the all-day capability of GSt-M device. Furthermore, it is also verified that GSt-M can desalinate water effectively to produce clean water with reasonable salt rejection in low concentration of salt-water. GSt was found to be extremely stable in most harsh chemical conditions and exhibits high thermal stability, demonstrating its applicability in practical sea-water desalination. In future work, large attention shall be focused on the scaling up and optimization of GSt-M in solar stills for efficient clean water generation with low-input power supply.

Methods

Fabrication of thiol functionalized glassy carbon foam (GSt)

Glassy carbon foam (GS) with a thickness of 0.5 cm and pore size of 200–300 µm, and melamine sponge were purchased from Alfa Aesar Co., Ltd. (South Korea). Sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄), nitric acid (HNO₃), dimethylformamide (DMF), and thiourea (all analytical grade) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (South Korea) and used without further purification. Commercial copper tape and silver paste were sourced from Coupang corporation. (South Korea). To prepare the thiol-functionalized glassy carbon foam (GSt), square samples of GS (2 × 2 cm²) were first oxidized by immersion in a mixed acid solution of 10 mL HNO₃ and 30 mL H₂SO₄ for 4 h at room temperature. The oxidized foams were rinsed thoroughly with deionized water and then transferred to a solution containing 0.38 g thiourea in 50 mL N,N-Dimethylformamide. The mixture was heated at 90 °C for 3 h to complete the surface functionalization. After reaction, the resulting GSt samples were washed repeatedly with deionized water and dried under ambient conditions prior to use.

The surface characteristics of pristine GS and GSt were assessed by employing a high-resolution field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, JSM 7800 F Prime, JEOL, Ltd., Japan). The elemental compositions of both GS and GSt were investigated using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, PHI 5000 VersaProbe III). Additionally, the molecular structures of these materials were examined by employing an X-ray diffractometer (D8 Advance DSVINCI, Bruker USA). The hydrophobicity of the test surfaces was gauged by measuring water contact angles using a SmartDrop instrument (Femtofab, Korea). Furthermore, the optical characterization of GS-t was characterized by using a UV-Vis-NIR spectrometer (V-670, JASCO INC., Japan).

Steam generation performance tests

The evaporation performance of the GSt-M device was evaluated using a AAA solar simulator (PEC L−101, Korea) under controlled conditions (24–26 °C, 40–50% relative humidity) and a constant solar intensity of 1 kW m⁻². The GSt sample (2 × 2 cm², exposed area <1 cm²) was placed atop a melamine sponge floating on bulk water in a beaker, providing thermal insulation and water transport. Mass loss of water over time was measured using an electronic analytical balance. Surface temperature was recorded using an IR thermal camera (FLIR C3, USA). Joule heating was provided using either a high output current custom DC power supply (Ametek/Sorensen XFR 60-20) or a conventional lab supply (SMART RDP-305). Electrical contacts were established using copper tape, silver paste, and copper wires. For solar desalination, simulated seawater solutions (3.5–20 wt%) were tested under similar conditions. Evaporation rates were recorded across different input voltages (1–5 V) under 1 sun illumination.

Data availability

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

References

Lewis, N. S. Research opportunities to advance solar energy utilization. Science 351, aad1920 (2016).

Xu, Y. et al. Robust and multifunctional natural polyphenolic composites for water remediation. Mater. Horiz. 9, 2496–2517 (2022).

Selvam, A., Jain, G., Chaudhuri, R. G., Mandal, M. K. & Chakrabarti, S. Avant-garde solar–thermal nanostructures: nascent strategy into effective photothermal desalination. Sol. RRL 6, 2200321 (2022).

Wu, X., Chen, G. Y., Owens, G., Chu, D. & Xu, H. Photothermal materials: a key platform enabling highly efficient water evaporation driven by solar energy. Mater. Today Energy 12, 277–296 (2019).

Uskoković, V. A historical review of glassy carbon: synthesis, structure, properties and applications. Carbon Trends 5, 100116 (2021).

Cheng, P. et al. Advanced phase change hydrogel integrating metal-organic framework for self-powered thermal management. Nano Energy 105, 108009 (2023).

Xue, C. et al. Enhanced interfacial solar driven water evaporation performance of Ti mesh through growing TiO2 nanotube and applying voltage. Sep. Purif. Technol. 314, 123633 (2023).

Su, J., Chang, Q., Xue, C., Yang, J. & Hu, S. Sponge-supported reduced graphene oxides enable synergetic photothermal and electrothermal conversion for water purification coupling hydrogen peroxide production. Sol. RRL 6, 2200767 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. All-weather-available electrothermal and solar–thermal wood-derived porous carbon-based steam generators for highly efficient water purification. Mater. Chem. Front. 6, 306–315 (2022).

Zhao, X. et al. All-weather-available, continuous steam generation based on the synergistic photo-thermal and electro-thermal conversion by MXene-based aerogels. Mater. Horiz. 7, 855–865 (2020).

Liu, F. et al. Electrically powered artificial black body for low-voltage high-speed interfacial evaporation. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 22992–23000 (2022).

Pandit, T. P., Wilson, H. M. & Lee, S. J. Joule-heating assisted heliotropic solar steam generator for all-day, all-weather solar desalination. Desalination 573, 117185 (2024).

Chen, T. et al. Highly anisotropic corncob as an efficient solar steam-generation device with heat localization and rapid water transportation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 50397–50405 (2020).

Yu, K. et al. Superhydrophilic and highly elastic monolithic sponge for efficient solar-driven radioactive wastewater treatment under one sun. J. Hazard. Mater. 392, 122350 (2020).

Kuyuldar, E. et al. Monodisperse thiourea functionalized graphene oxide-based PtRu nanocatalysts for alcohol oxidation. Sci. Rep. 10, 7811 (2020).

Varodi, C. et al. Nitrogen and sulfur co-doped graphene as efficient electrode material for L-cysteine detection. Chemosensors 9, 146 (2021).

Ayiania, M. et al. Deconvoluting the XPS spectra for nitrogen-doped chars: an analysis from first principles. Carbon 162, 528–544 (2020).

Gupta, S. P. et al. Ultra-high energy stored into multi-layered functional porous carbon tubes enabled by high-rate intercalated pseudocapacitance. Carbon 192, 153–161 (2022).

Li, Z. Q., Lu, C. J., Xia, Z. P., Zhou, Y. & Luo, Z. X-ray diffraction patterns of graphite and turbostratic carbon. Carbon 45, 1686–1695 (2007).

Mao, J., Wang, Y., Zhu, J., Yu, J. & Hu, Z. Thiol functionalized carbon nanotubes: Synthesis by sulfur chemistry and their multi-purpose applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 447, 235–243 (2018).

Chen, N. et al. Porous carbon nanowire array for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 11, 4772 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Graphene oxide-based efficient and scalable solar desalination under one sun with a confined 2D water path. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 13953–13958 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Korean government for the financial support through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (MSIT) (RS-2024-00341278). H.M.W. thanks Brain Korea (BK21) for financial support through a BK21 research fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M.W. conceptualized the device, designed and fabricated the experiments, performed formal analysis, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. T.P. carried out the experiments and investigations, performed formal analysis, and wrote the original draft. S.R.A.R. contributed to device conceptualization, conducted investigations, and participated in drafting the manuscript. A.T. conducted experiments and contributed to the original draft writing. H.W.L. carried out investigations and provided experimental resources. S.J.L. acquired funding, provided resources, supervised the project, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Manabu Fujii] and [Philip Coatsworth].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, H.M., Pandit, T.P., A.R, S.R. et al. Engineering electrothermally enhanced interfacial evaporation for high-performance solar desalination. Commun Eng 4, 166 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00498-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00498-z