Abstract

The quest for agile quadrupedal robots is limited by handcrafted reward design in reinforcement learning. While animal motion capture provides 3D references, its cost prohibits scaling. Video learning provides an efficient alternative yet suffers from 2D limitations and joint tracking failures during explosive motions. We address this with a novel video-based framework. First, robust 2D pose estimation constructs a skeleton graph model, enabling Kalman-filter-based joint position fusion. Next, a spatial-temporal graph convolution network aggregates spatial pose features via graph convolutions and temporal dynamics through dilated convolutions, recovering 3D joint trajectories. These trajectories are mapped to the robot’s joint space to formulate generative imitation learning. Real-robot deployment demonstrates successful learning of complex motions: gallop (high-speed), tripod (fault-tolerant), bipedal (quadrupedally challenging), and backflip. The proposed framework significantly advances robotic locomotion capabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advancements in deep reinforcement learning have significantly improved the locomotion capabilities of quadrupedal robots. Quadrupedal robots have demonstrated impressive locomotion skills such as walking on uneven terrains1,2,3,4,5, soft terrains6, and even parkour7,8,9. However, their agility still cannot match that of animals. This is mainly due to the complexity of learning for aggressive motions. Reinforcement learning-based locomotion requires the design of many reward terms, which include linear and angular velocity tracking rewards, orientation rewards, joint velocity and acceleration rewards, smoothness rewards, foot clearance rewards, body height rewards, and so on. Tuning the weights for all the reward terms is extremely time-consuming, and an inappropriate tuning could lead to a failure in learning. Moreover, learning agile locomotion requires additional reward terms that can achieve the motion, which further complicates the reward design. Our work bypasses the need for complex reward function design by leveraging imitation learning, directly extracting motion priors from videos to avoid tedious hyperparameter tuning.

In contrast, imitating learning, which learns the reference motions from expert demonstrations, provides an alternative solution to learning agile locomotion skills10,11,12,13. Learning from animals saves the trouble of designing multiple rewards as these natural motions have already taken safety and energy efficiency implicitly into account. Consequently, imitation learning-based locomotion boils down to tracking reference motions. An intuitive approach to obtaining these reference motions is through motion capture systems. As such, several motion capture datasets13,14,15,16,17 have been collected to provide high-quality 3D joint trajectory data for learning. Although these datasets can facilitate learning from reference motions, acquiring them requires expensive specialized equipment and professional animal trainers. Training an animal to perform aggressive motions such as backflips may also take a significant amount of time. Moreover, these datasets are constrained in terms of data size, diversity of motion patterns, and indoor environments. Unlike conventional methods relying on costly motion capture devices, our work acquires diverse motion data from monocular videos, drastically reducing data collection costs and barriers.

Learning aggressive motions from internet video sources reduces the expense of motion capture systems, offering an economical imitation learning approach. The vast number of animal videos on the internet provides a diverse range of motions obtained in various indoor and outdoor environments, reducing the need for specialized data acquisition processes. Generating reference motions from videos requires extracting and tracking of 3D spatial positions of animal joints, and mapping of animal joint positions to the robot’s joint space.

Although learning from videos solves the insufficient dataset issue for imitation learning of aggressive motions, it also faces significant challenges. First of all, extracting joint positions from videos is challenging due to various factors such as occlusions by other objects and lighting conditions. It becomes more challenging when aggressive motions are considered. These aggressive motions can easily lead to motion blur, which makes the joint position detection extremely difficult. Aggressive motions also lead to dramatic changes in the pixel of the image, which introduces great challenges to tracking the joints. The second challenge is that monocular videos can only provide 2D information while 3D joint positions are required for quadrupedal locomotion, which is the key challenge of learning from videos. Methods extracting the pixel position of key points (joints) from videos have been proposed18,19,20,21. Recovering 3D motion from 2D videos is challenging for a single view. As such, multi-view 3D pose estimation methods have been developed to reconstruct 3D animal motion using multiple cameras22,23,24,25. Although these methods facilitate 3D pose estimation16, they require data collection in a controlled environment and with professional equipment, limiting their ability to utilize widely available monocular videos on the internet. Additionally, the frame rates of online videos are usually much slower than the control frequency of quadrupedal robots. Missing reference command of joint positions may lead to stability issues for quadrupedal locomotion. Consequently, learning aggressive motions from monocular vision remains challenging. By comparison, we propose a robust 2D pose estimation and tracking method (combining skeleton graphs and Kalman filtering) alongside a Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolution Network (STGNet), enabling precise 3D joint trajectory reconstruction from monocular videos and overcoming multi-view dependencies and trajectory discontinuities.

Here, we propose a three-step framework that enables quadrupedal robots to learn aggressive motions from monocular videos: (1) robust 2D pose estimation and tracking for aggressive motions in a video; (2) 3D pose estimation and reference motion generation; (3) generative imitation learning that can learn 3D reference motions generated from a video. DeepLabCut21 has been proposed for 2D pose estimation. However, its estimation performance drops significantly when dealing with fast motions in a video. We propose a robust 2D pose estimation and tracking for aggressive motions. First, we train a 2D pose estimation neural network using the DeepLabCut model. Then, an undirected skeleton graph model is constructed. With such a model, we will develop a Kalman filter approach to predict the pixel-level position of the joints. Finally, by associating the predicted and estimated positions, the final 2D pose estimation is obtained through the filter. By developing such a framework, fast motions can be extracted and tracked satisfactorily.

The second main featured component of our proposed framework is a Spatio-Temporal Graph convolution Network (STGNet) comprising a graph convolution network and a dilated temporal convolution network, which can recover the 3D pose estimation of the joints. A spatial-temporal skeleton graph is constructed from the 2D skeleton graph first. To reconstruct 3D motion sequences, the spatial pose motion feature of the spatial-temporal skeleton graph in each frame is aggregated through the graph convolution network, while the temporal motion feature is aggregated via the dilated temporal convolution network. STGNet is constructed using a residual structure, and the features are concatenated with the sliced feature from the branch. STGNet performs two regression tasks, one regressing the local positions of key joints while the other one estimating the trajectory of the root joint to obtain the global position of the root joint. By deriving the global positions of other joints from their local positions and the root joint’s global position, the proposed approach can effectively separate displacement motion from pose estimation.

Once 3D reference motions have been reconstructed from videos, we could use these motion priors to train quadrupedal robots to perform aggressive motions. The reconstructed motion data is mapped to the joint space of the quadrupedal robot. To facilitate the deployment of real robots, we also consider the real robot’s physical limitations by penalizing joint torques that exceed the limit. Finally, we formulate the locomotion problem as a generative imitation learning problem, which allows the robot to learn the reference motions while tracking omnidirectional velocity commands.

The proposed approach exhibits extraordinary advancements over existing imitation learning for quadrupedal robots17. Using open source motion capture data for initialization, the semi-supervised approach allows quadrupedal robots to learn aggressive motions, such as gallop, tripod locomotion, bipedal locomotion, and backflip, directly from videos without requiring prior knowledge of object shape, camera pose, or intrinsic parameters. This greatly facilitates learning of aggressive motions for which reference motion data is difficult to obtain. Our presented approach provides a general framework for learning aggressive motions from videos, even in the presence of motion blur.

Results

An overview of the results can be found in Movie S1 and Fig. 1. Our proposed framework enables a quadrupedal robot AlienGo to learn aggressive motions, including galloping, tripod locomotion, bipedal locomotion, and backflips from monocular videos. During inference, the robot can perform these motions without any prior information about the object shape, camera viewpoint transformation, or intrinsic parameters.

a gallop (b) tripod (c) bipedal, and (d) backflip locomotion that learns from corresponding monocular videos. The robot performs challenging locomotion stably. (Image source: YouTube. Dog running in slow motion; My 4 flipping dogs; Maisy the Little Dog practicing bipedal walking. rednote. Share my Dog).

2D pose extraction and tracking analysis

This section evaluates the performance of 2D pose estimation and tracking from monocular videos. The first step of 2D skeleton extraction involves annotating certain datasets to fine-tune the DeepLabCut model21. As depicted in Fig. S2, we visualize the results of 2D pose estimation, showing the red joints representing the right legs and distinguishing them from the left legs. During visualization, we connect the key points based on the real skeletal structure of the dog, forming the 2D skeleton graph.

Based on the 2D skeleton results, we find that there still are some inaccuracies in the estimation of key joints. Therefore, we implement our proposed joint tracking algorithm to reduce the occurrence of outliers. The joint trajectory tracking results without and with our proposed tracking approach are shown in Fig. 2d, e, respectively. As can be seen that without our tracking approach, the reconstructed joint trajectory is discontinuous. This discontinuous trajectory can be fatal for quadrupedal robots to learn. In contrast, our reconstructed motion trajectory (Fig. 2e) is smooth, which can provide a solid reference for 3D pose estimation and imitation learning.

a Images from the source video. b 2D pose estimation by DLC Superanimal quadruped model. c Refined skeleton with joints in pink and bones in white. d 2D pose visualization of joint position estimates directly from the DLC Superanimal quadruped model. The reconstructed trajectories are discontinuous and cannot be used for learning. e Joint trajectories are processed by our proposed method. It can be clearly seen that our reconstructed joint trajectories are significantly smoother compared to the DLC Superanimal quadruped model. f Visualization of the reconstructed joint trajectories. (Image source: YouTube. My 4 flipping dogs).

The purpose of proposing joint tracking is to enhance the reliability of 2D estimation. To validate the effectiveness of the tracking algorithm, we conduct three sets of comparative experiments using the video data, namely (a) non-joint tracking, (b) joint tracking based on position cost matrix, and (c) joint tracking with position and direction cost matrix. We calculate the mean per joint position error26 (MPJPE) in Eq. (1) as a tracking refinement evaluation index.

where Ns is the number of joint in the 2D skeleton S, \({J}_{f,S}^{f}(i)\) is the ith joint 2D pixel position estimated result of in the 2D skeleton S at frame f, \({J}_{gt,S}^{f}(i)\) is the joint i ground truth pixel position of in the 2D skeleton S at frame f. \({J}_{gt,S}^{f}(i)\) is obtained from the manually annotated dataset that is also used in finetuning the DeepLabCut21 model.

As shown in Table S1, it is observed that the tracked MPJPE is lower than that without tracking refinement, suggesting that tracking refinement enhances the accuracy of the 2D skeleton. The joint tracking method utilizing the position and direction cost matrix achieves a lower MPJPE compared to using only the position cost matrix, indicating that the former leads to improved joint estimation results in pixel dimensions. The result of the comparison27,28 on challenging subsets of the 2D pose estimation module is shown in Table S9.

To compare the trajectories before and after tracking refinement, we plot the skeleton results in Fig. 2a–c, where (a) shows the source images from the monocular video, (b) displays the 2D pose estimation result from the DLC superquad animal model, and (c) illustrates the result after fine-tuning DLC and joint tracking. Our approach accurately tracks the joint pixel positions in the video. The full tracked trajectory of all the joints using our approach is presented in Fig. 2f. It is evident that our joint tracking approach successfully recovers the 2D joint trajectory of the dog in the video, laying a solid foundation for 3D pose estimation.

3D pose estimation module analysis

This section evaluates the performance of 3D pose estimation from monocular videos. Utilizing the extracted 2D skeleton in pixel dimensions, we construct the 3D skeleton Graph GST, where the key points of animals serve as nodes and the physical connections represent edges.

In the 3D motion estimation module, our proposed skeleton graph convolutional network can reconstruct the 3D skeleton of quadrupeds from monocular videos. It needs open source motion capture data to warm up. In deployment, it avoid motion capture devices and can obtain various flexible motion data of quadrupeds.

Firstly, we qualitatively analyze the results of 3D skeleton reconstruction in Fig. 3. Keyframes from six videos are displayed at the top, with their corresponding 3D estimation results shown in the middle. The bottom section presents the retargeted result on the robot in PyBullet, where the reference 3D pose of the robot motion is depicted as points. It is evident that our algorithm can achieve accurate 3D motion estimation for backflips and bipedal actions without corresponding 3D ground truth in supervision data, even in cases where overlay occurs in the 2D skeleton.

From left to right are bipedal, backflip, trot, gallop, hurdle, and tripod motions. Top: video frames with 2D pose overlay. Middle: 3D reconstruction. Bottom: Retarget result on robot. (Image source: YouTube. See This Border Collie Walking On His Hind Legs; My 4 flipping dogs; Monkey; Dog running in slow motion; Lobo the Siberian Husky goes off script in the 24 inch class of agility competition. rednote. Share my Dog).

Next, we conduct ablation experiments to validate the effectiveness of STGNet in 3D pose estimation, comparing its performance with VideoPose3D29.

Ablation experiment of the STG module

To verify the effectiveness of the designed spatio-temporal graph convolution module, we adjust the number and size of STG modules and study their optimal stacking quantity. To achieve optimal performance of STGNet, we first investigate the impact of the number of stacked STG modules. According to Table S2, the 3D pose MPJPE performance of STGNet is best when the number of STG module stacks is four with a receptive field of 243 frames. Additionally, we vary the network width of the STG modules, dividing them into Large, middle, and small modules. In the case of stacking four modules, as shown in Table S3, the middle STG module achieves the best 3D pose estimation results.

Experiment of STGNet efficiency

To validate the effectiveness of our designed 3D pose estimation algorithm, we compare it with the VideoPose3D29, LiftPose3D30, SemGCN31, GLA-GCN32 algorithm to evaluate the accuracy of the model in 3D skeleton estimation. We observe that our model achieves a lower loss in 3D pose during the training process and a lower MPJPE on the validation dataset, demonstrating that STGNet is capable of extracting features more effectively from GST, leading to more accurate predictions in 3D pose estimation.

Imitated behavior analysis

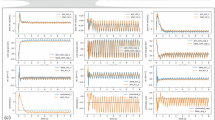

This section evaluates the performance of imitated behavior on AlienGo. To verify the effectiveness of the entire framework, the command tracking and the gait pattern are analyzed. Furthermore, we compare the extracted actions in the video with the actions learned by the robots to evaluate the similarity of the actions. The imitation source data is extracted from the monocular videos, and the training is formulated as an RL problem by optimizing and balancing task reward and style reward. Figure 4a–d shows the robot’s gait across different locomotion modes, such as gallop, tripod, bipedal, and backflip. The top figures illustrate the robot base and foot trajectories of each kind of motion, where the curve depicts the path of the foot. The robot’s base is depicted in pink, and the colored sphere indicates the foot’s contact with the ground. The gait and velocity changes are shown in the second and third lines, correspondingly.

Gait analysis of primary locomotion modes: Top row: Trajectory visualization of foot tips and robot base during (a) gallop, b tripod, c bipedal, and (d) continuous backflip motions. Middle row: Foot contact patterns showing ground engagement sequences for all limbs. Bottom row: Robot base velocity profiles. Command tracking on AlienGo robot: Ground contact patterns, angular velocity around vertical axis (ω), and linear velocity (vx, vy) tracking performance during (e) gallop, f tripod, and (g) bipedal motions.

Gallop gait feature

In the gallop motion, the robot achieves a mean movement speed of 2.5 m/s and a maximum speed of 3.45 m/s as illustrated in Fig. 4a. The maximum height during the gallop reaches 0.6 m and the airborne distance covers 1 m with the stepping frequency at 1.95 Hz, indicating that our model has successfully learned agile movement at high speeds.

In the top figure of Fig. 4a, we can observe the gallop action, corresponding to the gait in the middle figure. The robot’s gallop motion in period commences with all four feet on the ground for a very brief moment at a minimum velocity (Yellow). Subsequently, the front feet lift off the ground as the speed increases (Orange). Following this, the robot propels into the air, reaching a considerable height, and attaining maximum speed within the period (Red). Afterward, the front legs of the robot touch the ground again, initiating a decline in the robot’s speed (Purple). This completes one full motion cycle of the robot.

Tripod gait feature

The robot demonstrates stable performance in the tripod action. It is crucial to maintain balance when one leg of the robot is broken to achieve fault-tolerant locomotion33. In our test, it is highlighted that the robot’s maximum velocity is maintained at 1.495 m/s.

In the top figure of Fig. 4b, we can observe that the robot can follow a circular trajectory and achieve a mean speed of 0.75 m/s with the stepping frequency at 2.62 Hz as illustrated in Fig. 4b. In the tripod motion, the movements of the robot’s rear left (RL) and rear right (RR) feet resemble a trot, with the two hind feet alternating contact with the ground. Within one motion cycle, the robot’s actions begin with both rear feet on the ground and the front feet off the ground, initiating an increase in the robot’s speed (Yellow). Next, as the FL foot touches the ground and the RR foot lifts off, the robot’s speed reaches a maximum value, then slightly decreases (Orange). Subsequently, with only the FL foot on the ground and the RR and RL feet in an airborne state, the robot’s velocity gradually decreases to a minimum value (Red). In the final stage of one period, only the RR foot is on the ground, while the RL and FL feet lift off with an increase in the robot’s velocity (Purple).

Bipedal gait feature

In bipedal motion, as shown in Fig. 4c, the robot’s speed stabilizes at around 0.45 m/s with the stepping frequency at 3.3 Hz.

During one cycle, the gait of the robot’s rear legs remains consistent. Initially, both feet make contact with the ground (Green), then the robot’s rear legs exert force, causing both feet to leave the ground and enter an airborne phase (Dark blue). Subsequently, the robot lands again, repeating the bipedal motion. The robot’s forward speed exhibits minor fluctuations, but overall, the speed remains stable around the target value.

It is worth mentioning that we also demonstrate the transitions of the robot from bipedal to quadrupedal and from quadrupedal to bipedal, which is also challenging for quadrupedal robots34.

The robot is in a bipedal motion state (Yellow). Subsequently, the robot’s speed starts to increase, corresponding to the action of the robot’s front legs moving forward and downward (Orange). When the robot’s speed reaches its maximum value, the front legs make contact with the ground, leading to a rapid speed decrease (Red). Following this, the front legs FL and FR leave the ground, accompanied by an increase in the robot’s speed (Purple). The robot then reaches a standing state, jumps into the air, and the duration of airtime is longer than when the robot is stably walking bipedally (Blue).

Backflip gait feature

Notably, as illustrated in the top image of Fig. 4d, our robot is capable of executing consecutive backflips. Throughout a backflip sequence, the robot begins in a quadrupedal position with its speed at a minimum (Yellow). Subsequently, the front and rear legs alternate in applying force to lift off the ground, resulting in a speed increase up to a peak (Orange). Upon reaching this stage, the robot becomes airborne, with its center of mass following a parabolic trajectory. The robot’s speed initially decreases to a minimum near 0 m/s and then rises once more to a second peak (Red). Following this, the front and rear legs alternate in landing, returning the robot to a quadrupedal stance while the speed decreases to a minimum (Purple), completing one cycle of motion. The robot’s stepping frequency is 1.15 Hz.

Command tracking feature

In addition to mastering agile locomotion skills, the ability to accurately track commands is a crucial metric for evaluating the efficacy of a learning controller. In this section, we analyze the performance of linear velocity tracking and angular velocity tracking for three distinct locomotion modes: gallop, tripod, and bipedal.

To assess the policy’s command tracking capability, the robot receives commands in the form of step signals for forward velocity Vx, lateral velocity Vy, and angular velocity ω. The step response curves for gallop, tripod, and bipedal motion are depicted in Fig. 4e–g, respectively. The robot demonstrates good tracking of angular velocity and linear velocity, indicating that our controller effectively imitates actions while exhibiting good command-tracking performance. The fluctuations in the steady-state value around the command value are expected, as quadruped robots adhere to specific gaits during movement, leading to periodic variations in robot velocity and angular velocity over time.

Result in similarity

To assess whether the robot has successfully learned the reference actions, we conduct model testing and calculate the values of \({r}_{t}^{S}({{\boldsymbol{s}}}_{t},{{\boldsymbol{s}}}_{t+1})\) to evaluate the similarity between the reference actions and the robot’s imitated actions. The data we collect covers different actions (jump, trot, gallop, tripod, bipedal, backflip). Based on the trained policy, we record the similarity data of the robot interacting in 4096 environments for 100 steps. Each type of action has a total of 409,600 data points recorded. The probability density distribution, median, and interquartile range are visualized in Fig. S1.

According to Table S4, it is evident that the motion of the robot exhibits a high similarity with the reference data obtained from single-camera-based 3D quadruped pose estimation. This indicates that the imitation algorithm accurately learns and replicates the motion of quadruped animals. By analyzing statistical properties such as the median and quartiles, we can gain further insights into the consistency and stability of the robot’s locomotion. Maximum velocity metrics were obtained under idealized simulation conditions; actual hardware performance may vary due to terrain dynamics and actuator limitations.

From Fig. 1 and Movie S1, it is seen that the robot is capable of learning dynamic movements such as continuous backflips, challenging bipedal, and tripod locomotion for fault-tolerant control, as well as agile quadruped locomotion. The robot performs lifelike animal movements.

Motion imitation on real robots

The proposed framework is deployed on the robot AlienGo, which has twelve joints, including hip, thigh, and calf joints on each limb. The torque limitation for the four calf joints is 55 N ⋅ m, while for the other joints, it is 45 N ⋅ m. The mass of AlienGo is 23.24 kg. Based on the reconstructed 3D motions, in the motion imitation module, we set up four types of locomotion skills:

-

Agile quadruped motion: galloping, which can test the performance of the approach in the presence of high-speed motions.

-

Fault-tolerant locomotion: tripod, which is to validate the framework for fault-tolerant locomotion.

-

Challenging movements: bipedal, which tests the approach for highly challenging motions.

-

High explosive movements: backflip, which can validate the approach for highly explosive motions.

In the real-world legged robot experiments, we deploy the trained policies on AlienGo and record the joint data during the experiment. We analyze the robot’s actions, real animal movements, and the robot’s joints together, focusing on the joint torques of the robot. This is important as highly explosive movements require large joint torques, and it is crucial to ensure that the joint torques are within the torque limit.

Gallop

We included gallop as one of the real-world experiments to achieve agile and rapid quadrupedal motion. The robot’s galloping performance is showcased in Movie S2.

In Fig. 5A1, B1, we compare the galloping motion of a real dog in a video with the gallop action imitated by AlienGo. During the yellow period, the robot’s front feet leave the ground, leaving only the rear feet in contact, while the calf joints of the two rear legs exert force, enabling the robot to ascend in height and shift in the direction of motion. In the orange period, the robot is in the air, as can be observed in Fig. 5B1 where the robot exhibits a significant height off the ground. In the pink period, the robot’s front feet make contact with the ground, accompanied by rapid changes in calf joint angles and torques. In the purple period, the robot’s front feet remain in contact with the ground, exerting continuous force, while both rear feet make contact with the ground. It can be found that the motion in the source video clip and the robot’s imitation gallop results exhibit similar patterns of foot-ground contact.

A1–A4 Source video clips of gallop, bipedal, tripod, and backflip motions. B1–B4 Real robot motion imitation performance. C1–C4 Gait analysis: temporal foot contact patterns for front left (FL, red), front right (FR, orange), rear left (RL, blue), and rear right (RR, green) legs. Joint angle analysis of calf (D1, D3, D4) and thigh (D2) joints. Due to high motion symmetry, gallop (D1), bipedal (D2), and backflip (D4) display data only for FR (orange) and RL (blue) legs. Tripod motion (D3) includes all four calf joints, contact legs are annotated with color-matched boxes. E1–E4 Temporal joint torque analysis, following the same limb selection scheme as (D). (Image source: YouTube. Dog running in slow motion; My 4 flipping dogs; Maisy the Little Dog practicing bipedal walking. rednote. Share my Dog).

Tripod

Tripedal motion is important for fault-tolerant locomotion, enabling a quadrupedal robot to function effectively even when one leg malfunctions. The robot’s tripod imitation performance is showcased in Movie S3.

A comparison is made between the foot-ground contact in the original video and that during imitation learning experiments on the real robot, with different colored boxes representing different feet that contact the ground. We visualize the joint angles and joint torques of the four limbs because the motion of the four limbs does not exhibit high similarity. During the yellow period, the two rear feet of the robot are on the ground, while the broken front leg remains retracted, and the left front foot is in the air. The foot contact with the ground is highlighted in boxes in Fig. 5A3, B3. Subsequently, during the orange period, the robot’s front left foot is on the ground, with the contact area near the body’s central axis, while the left rear feet remain grounded, and the rear right leg moves forward. In the blue period, the rear feet of the robot are both off the ground, and the front left foot remains on the ground. It can be observed that the robot is performing a trot-like movement with the two rear legs moving alternately. Finally, during the purple period, the robot’s rear right leg is on the ground, and an increase in torque can be observed in the rear right calf in (E3), while the rear left and front left feet remain in the air.

From the source video clip, real robot motion imitation results, and the analysis of joint torques and angles, we can conclude that the proposed framework can effectively learn the motion patterns of quadrupedal animals from the corresponding video. Additionally, the joint torques of the robot remain within safe ranges.

Bipedal

The robot’s bipedal imitation performance is showcased in Movie S4. The corresponding source video clip for the bipedal action is shown in Fig. 5A2, while the imitation performance of AlienGo is depicted in (B2). These images sequentially demonstrate the process of transitioning from a quadrupedal to a bipedal stance, showcasing the action of rising from four legs to two. In (C2), (D2), and (E2), analyses of the foot contact, thigh joint angle, and torque for this action are presented. In the yellow phase, the robot is in a quadrupedal stance, awaiting input commands. Upon receiving a signal to move forward, the front legs exert force, causing the body to press down, followed by the rear legs exerting force, as indicated in the orange and pink phases. Subsequently, the robot lifts off the ground, accompanied by forward motion as depicted in the blue region, then lands with the rear legs bearing the impact force while the torque on the front legs remains at a lower value.

Backflip

As for the action backflip, we recorded the hardware data of the quadruped robot. The robot’s backflip imitation performance is showcased in Movie S5.

First, we analyzed the data of a single backflip. Because the left and right leg data of the backflip action are relatively symmetrical, the calf joint is an important joint that exerts force and is impacted during the backflip, the torque and angle information of the calf joints of the front right (FR) leg and the rear left (RL) leg can be seen in Fig. 5.

More real-world robot experiments are shown in Fig. S7. We conduct collision tests with a sponge to validate the stability of the tripod motion in the presence of disturbances. This is illustrated in the top of Fig. S7. Additionally, we train the robot to learn the action of the front left leg limp by learning from different dog limp video clips and successfully deploy it on the robot, as shown in the second line. In the bipedal motion, the back legs exert force to perform the bipedal motion cycle shown in the third line. The observation results of gallop locomotion from different vision angles are shown in the fourth line. What’s more, we also successfully deploy the continuous backflip on AlienGo, as shown at the bottom.

Discussion

To address reinforcement learning challenges for highly aggressive motions, this paper proposes a three-step framework that enables quadrupedal robots to learn challenging maneuvers from monocular videos and reduces the need for reference motion data from motion capture systems. To enable learning from videos, 3D motion needs to be reconstructed. Existing methods can extract 2D motions from a video. However, they can only consider videos without motion blur. For high-speed motions, the dramatic change of the pixel positions prevents the smooth extraction of motions. To address this challenge, we proposed a robust 2D pose estimation method that allows the extraction of smooth motions from a video. The validation results show that our approach can extract smooth motions from a video even when the animal is performing highly aggressive motions such as backflip.

To address the challenge of recovering the 3D motions from monocular videos, we proposed a framework: STGNet. STGNet uses a spatial graph convolutional network to aggregate the spatial dimensions in pixels and a temporal network to capture the temporal dimensions of motions across video frames over time. STGNet successfully reconstructed the 3D motions of animals in 2D monocular videos, which facilitated generative imitation learning.

The proposed framework was validated with videos of animals performing highly aggressive maneuvers such as gallop, tripedal and bipedal locomotion, and backflip. Despite the high-speed nature of these motions, the quadrupedal robot could successfully perform these maneuvers, reducing the need for reference motion data from motion capture systems. The quadrupedal robot can achieve agile motions while following reference velocity tracking commands. The maximum speed for the gallop motion imitation can reach up to 3.45 m/s, which strongly demonstrates the performance of the proposal framework.

The proposed framework has many important applications. The proposed framework allows quadrupedal robots to learn aggressive motions and skills from a vast number of web videos, reducing the need for motion capture systems, which significantly facilitates the imitation learning for robots. Collecting data from motion capture systems requires expensive professional equipment and even animal trainers, which is extremely time-consuming and costly. The vast number of web videos provides an abundant resource of motion types, which facilitates the learning of various motion skills. Such a framework would significantly advance the study of legged robots, including quadrupedal and humanoid robots, ultimately accelerating embodied artificial intelligence.

The proposed 2D pose estimation could also be used to study the locomotion properties of animals through videos, which facilitates motor control studies. Furthermore, it can also be used to track user-defined body parts for analyzing animal behaviors, which is often required in neuroscience studies21. The technique of reconstructing 3D motion from videos is also applicable to creating motions for digital persons or animals in a virtual world.

The three-step method we proposed enables quadruped robots to learn animal movements from monocular videos. This is very meaningful in improving the robot’s locomotion ability, but there are also several limitations, including cross-species morphological scalability and failure cases in 3D motion estimation.

Our framework can generalize across species but requires adjustments for bone structure variations, which requires that joint-point selection must be adapted to match target morphology, such as canine and human gaits. The method has successfully been deployed on quadruped robots, suggesting potential humanoid adaptation. The human pose estimation results shown in Fig. S3 validate this extensibility.

While our method incorporates robust data augmentation during training, performance may degrade under non-frontal camera angles, and wrong 2D skeleton input will affect the 3D estimation results.

Methods

Framework overview

To address the challenges mentioned in the introduction, our work introduces a framework for quadrupedal robots to learn agile locomotion skills from monocular videos. An overview of our proposed framework is given in Fig. 6. Through our proposed 3D motion reconstruction technique, the robot replicates motions observed in videos, enabling it to exhibit a range of locomotion skills. The motion reconstruction module processes animal motion videos to extract the spatial-temporal skeleton in both pixel and 3D dimensions. Through the utilization of the proposed 3D motion reconstruction technique, the robot mimics motions extracted from videos and acquires a variety of locomotion skills. Subsequently, the animal motion data is retargeted into the robot’s joint space, allowing the robot to imitate these motions using a generative imitation learning algorithm.

We divide the system into two steps: The 3D motion estimation module captures monocular videos of animals and generates a spatial-temporal skeleton motion graph in three dimensions. The motion imitation module adapts the animal motion data to the robot’s joint space and trains the robot to master these dynamic movements, enabling proficient performance in its environment. a Perception pipeline for animal 2D pose estimation and joint tracking. b 3D pose estimation module and structure of STGNet. c Control and deployment pipeline for imitating multiple video-extracted motions, such as backflip and bipedal movements.

We utilize an actuator net to bridge the gap between simulation and reality, ensuring that the robots exhibit stable performance in real-world experiments.

2D pose estimation module

2D pose detection

The 3D pose estimation module faces significant challenges when dealing with high-speed or explosive motions in certain public datasets, which may lack comprehensive coverage of such scenarios. Additionally, accurately reconstructing 3D poses from 2D RGB videos, which are inherently limited in their lack of depth information, poses a formidable obstacle. We propose a method to estimate the 3D skeleton pose of quadruped animals from monocular videos, as shown in the 3D motion estimation module in Fig. 6.

The joint structure of robots does not correspond to that of real quadruped animals, as shown in Fig. S4, where the knee joint direction in the hind legs of robots and dogs is opposite. To meet the requirement of accurately mapping the skeleton to the robot, the estimated joints should align with those of the robot. Initially, we annotate joint data in videos to fine-tune the popular 2D pose estimation method, the DLC model21,35, to extract the 2D skeleton from the videos. This process enables the refined DLC model to estimate the newly selected joints more accurately, making them correspond better with and be more precise for the robot’s joints. Subsequently, we only utilize the hip and foot joints as corresponding joints between the robot and the dog, while the knee joint’s pose is solved through inverse kinematics and joint position constraints. The DLC superquad model has been trained on a large dataset of images containing quadruped animals, resulting in a well-pretrained model that can be fine-tuned for a specific task. We select the joints to estimate the pose of the quadruped animal in pixels, which include the hip, thigh, and calf joints in each leg, as well as the back end, spine, neck, head, and nose joints that serve as the backbone, as shown in the left picture of Fig. S4, the points represent the annotated joints, and the edges between them indicate physical connections on real quadruped animals. The fine-tuned model can estimate the self-defined joints and Fig. S4 provides a visual representation of the annotated joints and their corresponding robot joints.

After fine-tuning the DLC model, we can extract the desired pixel position of quadruped joints from the video. Utilizing the physical connections between the animal’s bones, we create an undirected skeleton graph where the extracted key points serve as nodes and the physical connections act as edges. This skeleton graph is denoted as \({\bf{G}}=\left\{{\bf{V}},{\bf{E}}\right\}\), with V representing the pixel positions of N joints, denoted as vi ∈ V, and \({\bf{E}}=\{{v}_{i}{v}_{j}| (i,j)\in H\}\), where H signifies the naturally connected quadruped animal joints.

By leveraging the physical connections among the animals, we establish an adjacency matrix \({\bf{A}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times N}\), with binary elements. The value of aij ∈ A being 1 indicates the presence of an edge connecting (vi, vj), while a value of 0 signifies the absence of a physical connection between (vi, vj).

At this stage, we obtain the joint position sequenc \({{\bf{J}}}_{i}^{f},i=1,2,\ldots ,N\) and a 2D skeleton graph sequence \({{\bf{G}}}^{f}=\left\{{{\bf{V}}}^{f},{{\bf{E}}}^{f}\right\}\) in temporal order, where f denotes the frame.

Joint tracking

In scenarios involving occlusion and rapid motions, the video-derived joint positions of the animal may become interchanged, leading to imprecise or low-confidence detection outcomes. This has brought significant challenges to track the joints in videos with high-speed motions.

To tackle this challenge, we devise an outlier refinement and joint tracking methodology to bolster the data’s reliability. As depicted in Fig. 6a, the framework showcases the process of animal pose estimation and tracking, utilizing a monocular video as input and employing DLC pose estimation to derive the initial 2D skeleton across a temporal sequence. The outlier refinement stage is then employed to eliminate outliers within the dataset. Subsequently, joint tracking is implemented on the joint sequence to capture the trajectories of each joint and refine the skeleton sequence.

Outliers refinement

Initially, these drastic changes in values are categorized as outliers, indicating significant shifts in position between two frames or joint angles exceeding predefined limits. The outliers are consolidated into a set. Subsequently, interpolation is carried out utilizing the normal joint positions across time to substitute the outlier values.

Joint position prediction

In our work, the proposed joint tracking framework is shown in Fig. 6a. The coordinates of joints in pixels are the state variables of interest. We assume that the joint movement follows a variable acceleration motion profile. Therefore, we set up a state transition model Eq. (2) for the tracking target joints in the video. Based on Eq. (2), we can get the joint state at frame f as Jf predicted from Jf−1, and at the same time, we have the joint position at frame f in the estimated joint sequence \({{\bf{J}}}_{o}^{f}\) as observation from Eq. (3).

where at frame f, Ff represents the state transition matrix, wf signifies the process noise, with a mean value of zero, a covariance of Qf, and follows a multivariate normal distribution. vf stands for the observation noise, which follows a zero mean Gaussian white noise with a covariance of Rf. Hf denotes the observation model from the true state space to the observation space, which is an identity matrix in this case. The observation state \({{\bf{J}}}_{o}^{f}\) corresponds to the true state Jf of the animal. Based on the above model, we conduct Kalman filtering prediction using Eqs. (5) and (6). Each joint is represented by a state vector \([{p}_{x},{p}_{y},{v}_{x},{v}_{y},{a}_{x},{a}_{y},{\dot{a}}_{x},{\dot{a}}_{y}]\).

where Pf∣f−1 is the prediction error covariance matrix. To derive the trajectory of each joint, we begin by considering the joint position in the first frame as the trajectory’s initial point T. Subsequently, utilizing Eq. (2), we estimate the predicted state \({\hat{{\bf{J}}}}^{f| f-1}\) at the next frame f, with the 2D pose estimation detection in frame f serving as the observed state \({{\bf{J}}}_{o}^{f}\).

Data association

Given that there are N selected joint positions in each quadruped, we need to establish a one-to-one correspondence between the predicted states of the N joints and the observation states of the current frame f based on data association. To achieve this, we construct a cost matrix C that represents the matching cost between the ith joint state observation and the jth trajectory prediction. The position of the same joint in the prediction and observation values in frame f should be close to each other, hence, the cost calculation considers the position distance as indicated in Eq. (9). Additionally, given the continuous nature of animal motion within the fixed camera field of view due to joint velocity constraints, we introduce the velocity direction difference in the cost matrix. This addition aims to mitigate Kalman filter tracking results that deviate from the actual motion scenario. The cosine distance is used to quantify the velocity direction difference, as shown in Eq. (10). Furthermore, we incorporate the joint detection confidence cost denoted as \(-\sigma {{\bf{J}}}_{conf}^{T}\) in Eq. (7), where σ represents the proportionality factor of joint detection confidence cost, and \({{\bf{J}}}_{conf}^{T}\) is a matrix with confidence values of joints on the diagonal and zeros elsewhere. This element accentuates the preference for associating joints in 2D pose estimation with high confidence levels. The cost matrix C and cost between \({{\bf{J}}}_{o}^{f}(i)\) and \({\hat{{\bf{J}}}}^{f| f-1}(j)\) are shown in Eqs. (7) - (10).

with

where \({{\bf{T}}}_{j}^{f-1}\) represents the jth joint state at frame f − 1 in trajectories, and cosd represents the cosine distance. The prediction and observation of the joint key points are assigned using the Hungarian algorithm36 to minimize the total cost.

Joint position update

Following the data assignment process, the matched prediction and observation pairs can be updated using the Kalman filter update equations as shown in Eqs. (11), (12) and (13) to estimate joint positions.

where Kf is the Kalman gain, \({\hat{{\bf{J}}}}^{f}\) is the updated joint state at frame f, and Pf is the updated posterior estimation error covariance matrix.

If the cost value between the ith joint state observation and jth trajectory prediction exceeds the threshold, it is considered that the observation has a significant error, indicating that the 2D pose estimation joint position is inaccurate. In such cases, only the predicted value is utilized as the final estimation, which is then added to the joint trajectory without being updated with the observation.

The updated result \({\hat{{\bf{J}}}}^{f}\) will be added to the trajectory Tf, facilitating joint position estimation is optimization through joint tracking. The pseudo code for this process is depicted in Algorithm 1.

3D skeleton estimation module

In this research, we introduce a 3D skeleton estimation technique that forms the foundation of the 3D pose estimation module. Due to the absence of depth information in the 2D skeleton sequence, we design a 3D skeleton graph that integrates spatial dimensions in pixels and temporal dimensions across video frames to capture motion progression over time.

Skeleton graph construction

Based on the 2D skeleton sequence \({G}^{f}=\left\{{V}^{f},{E}^{f}\right\}\), we construct a spatio-temporal undirected graph GST in Eq. (14), where the 2D-pixel spatial positions of skeleton keypoints serve as nodes V, and the connections in the sequence act as edges E consisting of \({E}_{s}^{f}\) and \({E}_{t}^{f}\). \({E}_{s}^{f}\) defines the set of intra-skeleton connections at frame f, and \({E}_{t}^{f}\) represents the set of edges between the same nodes in the temporal domain.

where T represents the duration of input videos.

Spatio-temporal graph convolution network

To effectively extract and fuse spatiotemporal motion cues, we propose a Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (STGNet) framework operating on the spatiotemporal skeleton graph GST. This approach explicitly models bone connectivity through edge features within skeletal topology graphs, replacing isolated joint coordinates to encode biomechanical constraints, while utilizing sliding temporal convolution kernels to aggregate cross-frame motion dynamics and address motion continuity loss inherent in single-frame observations. Utilizing the graph GST as input, our STGNet employs dilated temporal convolution for efficient long-range motion aggregation and graph convolution for spatial feature modeling. The network consists of Spatio-Temporal Graph (STG) modules, as shown in Fig. S5. The layer configurations and hyperparameters of STGNet are shown in Tables S7 and S8.

The STG module enables the network to aggregate features within the skeleton and inter-frame features effectively. Given an intermediate feature map \({\boldsymbol{F}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{C\times V\times T}\) as input, the STG module initially aggregates spatial information of the feature map through the graph convolution, producing a spatial context descriptor FGCN by combining features of nodes within the same frame. In contrast to graph convolution, temporal convolution focuses on aggregating features across temporally adjacent frames. By employing a dilated convolution, the module fuses features of the same joints from temporally adjacent frames, generating a temporal context descriptor FTCN. This approach allows for an expanded temporal receptive field of the network while maintaining efficiency with fewer parameters. The FGCN37 and FTCN can be implemented with the following formula:

where \({{\mathbf{\Lambda }}}^{ii}=\sum _{j}({A}^{ij}+{I}^{ij})\). The symbol W represents the weight matrix, which is constructed by stacking weight vectors corresponding to multiple output channels.

The STG module is constructed using a residual structure inspired by the ResNet architecture38. The residuals are sliced as the size of FTCN. Following batch normalization and activation layers, the feature is concatenated with the sliced feature from the branch. The formulation of the STG module can be expressed as:

STGNet is a contract based on the stacked STG module, the structure of which can be observed in Fig. S5. At the beginning of STGNet, a batch normalization layer is utilized to reduce the model’s sensitivity to initial values. The spatial and temporal receptive field of STGNet can be adjusted by stacking varying numbers of STG modules. Increasing the number of stacked STG modules expands the aggregation of spatial features from the current node to more distant skeletal connections. Similarly, temporal features aggregate more features from the same node further in time from the current frame. By integrating four STG modules in STGNet, we achieve a comprehensive aggregation of motion features within the inner skeleton and across frames, thus enhancing the understanding of quadruped motion patterns.

For the dataset, we combine motion capture data from AI4Animation14 with synthetic datasets from Digdogs16. To process these three-dimensional data, we utilize four virtual cameras to transform it into two-dimensional pixel coordinates. The three-dimensional data serves as the ground truth for training the 3D pose estimation network on two-dimensional pixel data.

The network in Fig. 6(b) consists of two regression tasks, one for regressing the local positions of key joints, and the other for estimating the trajectory of the root joint. The first task involves 3D pose estimation, with the hip joint serving as the root joint to determine the local 3D positions of other joints relative to it. The second task focuses on root trajectory estimation to predict the global position of the hip joint. By deriving the global positions of other joints from their local positions and the root joint’s global position, this approach effectively separates displacement motion from pose estimation.

Semi-supervised approach

However, we find that both the above motion capture datasets and synthetic datasets lack challenging actions, such as tripod, bipedal, and backflip, which are necessary for robot operations under motor failures or extreme working environments. To estimate these actions, we adopt the method in ref. 29 by using a semi-supervised method.

The supervised stream utilizes motion data with 3D ground-truth annotations, while the unsupervised stream processes unlabeled 2D skeleton data. Specifically, the unsupervised branch: (1) estimates 3D poses from 2D inputs, (2) reprojects them to 2D space, (3) computes losses via 2D MPJPE and mean bone length in pixel space (Fig. S6). This motion capture data supports training exclusively and is excluded from the deployment pipeline. We fine-tune DeepLabCut21 on labeled 2D data as detailed in the Section 2D Pose Estimation Module. The model undergoes warm-up training: 10 epochs on 10% subsampled data. STGNet extracts spatio-temporal features from animal 2D skeletons (obtained via DeepLabCut) to predict 3D poses, with the rest of the data as the unsupervised data. Predicted 3D poses are projected to 2D image space using virtual cameras as described in Eq. (27) in Section Implementation detail, generating estimated 2D keypoints derived from 3D predictions.

As the depth of the target increases, the spatial distance represented by each pixel also increases. Even with an accurate estimation of the 2D skeleton in pixel space, errors in 3D motion estimation are inevitable. Therefore, we designed weights for the root joint of the temporal skeleton graph with the purpose of giving higher weights to closer joints in the camera coordinate. This weighting is intended to increase the accuracy of the near-camera skeleton estimation.

We optimize a loss function based on Mean Per Joint Position Error (MPJPE) as follows:

where Ns represents the number of joints in the 3D skeleton S. \({J}_{f,S}^{f}(i)\) denotes the estimated 3D position of joint i in the local space of skeleton S at frame f, while \({J}_{gt,S}^{f}(i)\) indicates the ground truth position of joint i relative to the root joint in the 3D skeleton S at frame f. Additionally, \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{trj}(f,S)\) is utilized for regressing the root joint Jr trajectory as follows:

For the unlabeled data, we adopt the bone loss in Eq. (20).

where Nb represents the number of bones in skeleton S. \({E}_{f,S}^{f}(i)\) denotes the estimated length of the ith bone, while \({E}_{gt,S}^{f}(i)\) represents the ground truth length of the ith bone. The set E represents the edges of the 3D skeleton. If supervised learning is used, λb is set as zero.

In the 3D motion estimation module, we utilize the fine-tuned DLC to extract the pixel position of animal joints. Subsequently, we refine the joint trajectories through joint tracking to generate a spatio-temporal graph of animal motions. We then propose a skeleton graph convolutional network to reconstruct the 3D skeleton of quadrupeds from monocular videos. This approach reduces the need for motion capture devices and enables the capture of diverse and flexible motion data of quadrupeds. The motion data obtained can be used by quadruped robots as reference data to learn various locomotion skills.

Motion imitation module

In the 3D motion estimation module, we extracted the three-dimensional joint information of the animals from the video. In this section, we will introduce the content of action imitation learning based on the above data.

The motion imitation module’s target is to make the robot learn advanced locomotion skills, including walking, trotting, and galloping, to realize smooth gait switch at different speeds, realize tripod locomotion to achieve fault-tolerant locomotion, and imitate bipedal and backflip locomotion to enable flexible and challenging movements.

To realize this objective, we first map the reconstructed motion data to the robot joint pose space. Subsequently, this dataset is used as the reference in imitation learning algorithm. The resulting imitated policy is essentially a locomotion controller that tracks omnidirectional velocity commands and models a versatile repertoire of skills by imitating the animal behaviors extracted by previous steps. The resulting locomotion policy πL generates joint-level actions to control the robots.

Motion retargeting

Our motion retargeting approach addresses morphological discrepancies between animals and robots through constrained inverse kinematics optimization. By establishing keypoint correspondences between source keypoints \({\hat{{\bf{x}}}}_{i}(t)\) on the subject (e.g., animal) and target keypoints xi(qt) on the robot and minimizing both positional errors and biomechanical constraints, we formulate the problem as a spatiotemporal optimization:

Here, W is a diagonal weight matrix that prioritizes regularization for specific joints (e.g., higher weights for mechanically sensitive joints), and \(\bar{{\bf{q}}}\) is the nominal joint positions of the robot. For kinematic adaptation, we employ a biomechanically grounded scaling model:

to maintain dynamical equivalence while compensating for morphological differences, where \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{b}}}\) (biological joint length) and \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{r}}}\) (robotic counterpart) are normalized morphological parameters, α=0.85 serves as the kinematic fidelity coefficient (dimensionless) and β=1.2 acts as the torque compensation factor (dimensionless).

State space

The input to the low-level policy \({{\boldsymbol{o}}}_{t}^{L}\) consists of proprioception \({{\boldsymbol{o}}}_{t}^{p}\) and commanded velocity \({{\boldsymbol{v}}}_{t}^{cmd}\), as shown in Fig. 6. \({{\boldsymbol{o}}}_{t}^{p}\) contains base angular velocity in the robot’s frame \({{\boldsymbol{\omega }}}_{t}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\), projected gravity \({{\boldsymbol{g}}}_{t}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\), joint angles \({{\boldsymbol{q}}}_{t}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{12}\), joint velocities \({\dot{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_{t}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{12}\), and the action of the last step \({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{t-1}^{L}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{12}\). As the base linear velocity \({{\boldsymbol{v}}}_{t}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) cannot be directly acquired on the real robot while is easily accessible in the simulation, we consider vt, in addition to \({{\boldsymbol{o}}}_{t}^{p}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{v}}}_{t}^{cmd}\), as part of the privileged states that serve as input to the critic net.

Action space

The action of locomotion policy \({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{t}^{L}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{12}\) is the desired offset of the joint angle added on a time-invariant nominal pose \(\mathop{q}\limits^{\circ }\), i.e., \({{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{t}^{L}={{\boldsymbol{q}}}_{t}^{* }\) - \(\mathop{q}\limits^{\circ }\). The final desired angle \({{\boldsymbol{q}}}_{t}^{* }\) is tracked by the torque generated by the joint-level PD controller, i.e., \({\boldsymbol{\tau }}={{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{p}\cdot ({{\boldsymbol{q}}}_{t}^{* }-{{\boldsymbol{q}}}_{t})+{{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{d}\cdot (-{\dot{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}_{t})\). To mitigate the reality gap in real-world deployment, this motor actuation module is replaced by an actuator network trained with data collected from real machines, following the steps in39 and our previous work40.

Reward function

Tracking-based imitation minimizes the error between the reference and the simulated motion13, but it encounters challenges in integrating diverse motions into a cohesive strategy. Here, we adopt the Adversarial Motion Priors (AMP)41,42, a generative imitation learning, which employs GAN-style training to optimize a ‘style’ performance from a set of motion demonstrations \({\mathcal{M}}\).

The procedure of AMP is interpreted as the learning agent yielding the states and actions that the discriminator cannot reliably distinguish from the real data. The reward engineering of AMP consists of a style component \({r}_{t}^{S}\), a task component \({r}_{t}^{T}\) and a regularization component \({r}_{t}^{R}\) with respective weights α:

The task-specific reward \({r}_{t}^{T}\) encourages the robot to track command linear and angular velocity. The style reward \({r}_{t}^{S}\) encourages the similarity between the reference and the agent motion. Next, a neural network-based discriminator \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{\psi }\), parameterized by ψ, is trained to predict whether a state transition (st, st+1) is sampled from a “real” expert reference or a “fake” agent. The training objective for the discriminator41 is as follows:

where βgp is a coefficient specified manually as 10. This function guides the discriminator to predict a score of 1 and -1 for samples collected from the reference dataset \({\mathcal{M}}\) and policy πL, respectively. The final term guarantees stable training by penalizing nonzero gradients on samples from the dataset \({\mathcal{M}}\). The style reward is then defined by:

The regularization \({r}_{t}^{R}\) reward allows the robot to achieve better smoothness. The detailed reward terms can be found in Table S6. We introduce a torque limit reward to encourage high-impact actions by penalizing values close to the physical torque limits. Additionally, the feet’s air time reward is utilized to incentivize the robot to move more effectively in the air, particularly during jumps, gallops, and backflips.

Domain randomization

The domain randomization43 is adopted to reduce the domain gap, which includes dynamics parameter randomization, motor domain randomization, and payload randomization. This aims to expose the learning agent to a broader distribution of conditions, thus increasing the robustness of the learned policy and improving its generalization capabilities to unseen dynamics and sensory characteristics of the real world. The domain randomization we used is shown in Table 1.

Implementation detail

The real-world experiment is conducted on the quadrupedal robot AlienGo, which has twelve joints, with hip, thigh, and calf joints on each limb. The torque limitation for the four calf joints is 55 N ⋅ m, while for the other joints, it is 45 N ⋅ m. The mass of AlienGo is 23.24 kg. The proposed learning framework was implemented using PyTorch44. The hardware setup includes NVIDIA A100 80G GPU, 128 cores Intel Xeon Platinum 8370C CPU, and Ubuntu 22.04.3 LTS system. The locomotion control policy runs at 50 Hz.

As previously mentioned, publicly available datasets are limited in both size and variety. Therefore, we leverage data from two datasets, AI4Animation14 and Digidogs16. Both datasets provide motion data for different joints of a dog. However, they differ in their dataset structures and the number of key joints provided. To address this, we standardized the data from both datasets to a uniform format. We selected 17 key joints as a skeleton, including five joints in the backbone and three joints on each limb. The AI4Animation dataset only provides 3D data, while our 3D motion reconstruction algorithm requires pixel data as input and 3D motion data as supervision. To address this issue, we introduce m virtual cameras \(\{{C}_{j},j=1,2,\ldots ,m\}\) with known intrinsic \(\{{{\boldsymbol{K}}}_{{\boldsymbol{j}}}\}\) and extrinsic parameters \(\{{{\boldsymbol{E}}}_{{\boldsymbol{j}}}\}\). Using the virtual cameras, we project the data into a 2D-pixel space.

We define the 3D joints coordinate at world frame f as \({{\boldsymbol{P}}}_{3d}^{f}\), and the projected pixel coordinate as \({{\boldsymbol{P}}}_{2d}^{f}\). As for a certain joint i, \({{\boldsymbol{P}}}_{3d}^{f}(i)\) with position as \([{x}_{i}^{f},{y}_{i}^{f},{z}_{i}^{f}]\). We follow Eq. (27) to project the 3D points onto the image coordinate system of each virtual camera Cj.

\({{\boldsymbol{P}}}_{2d}^{f}\) is further filtered by only including the data points that falls within the field of view of each virtual camera pixel coordinate. Before proceeding with network training and inference, we first normalize the input data to ensure that pixel coordinates are scaled to [0,1].

The proposed learning framework is utilized for training locomotion controllers on the legged robot AlienGo in the physics simulator45. Our framework successfully trains robust locomotion controllers for individual robots using various monocular video-extracted motion data. As depicted in Fig. S8, the policy gradually learns to maximize the designed rewards with different imitation data styles and robots, demonstrating the algorithm’s generalization capability and the effectiveness of the three-dimensional motion estimation algorithm in obtaining data.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

Code availability

The code to reproduce the learning experiments can be found at https://github.com/arclab-hku/Imitation_from_video.git.

References

Lee, J., Hwangbo, J., Wellhausen, L., Koltun, V. & Hutter, M. Learning quadrupedal locomotion over challenging terrain. Sci. Robot. 5, abc5986 (2020).

Kumar, A., Fu, Z., Pathak, D. & Malik, J. Rma: Rapid motor adaptation for legged robots. arXiv:2107.04034 (2021).

Margolis, G. B. & Agrawal, P. Walk these ways: Tuning robot control for generalization with multiplicity of behavior. In Conference on Robot Learning, 22–31 (PMLR, 2023).

Nahrendra, I. M. A., Yu, B. & Myung, H. Dreamwaq: Learning robust quadrupedal locomotion with implicit terrain imagination via deep reinforcement learning. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 5078–5084 (IEEE, 2023).

Jenelten, F., He, J., Farshidian, F. & Hutter, M. Dtc: deep tracking control. Sci. Robot. 9, eadh5401 (2024).

Choi, S. et al. Learning quadrupedal locomotion on deformable terrain. Sci. Robot. 8, eade2256 (2023).

Zhuang, Z. et al. Robot parkour learning. In Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL) (2023).

Cheng, X., Shi, K., Agarwal, A. & Pathak, D. Extreme parkour with legged robots. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pp. 11443–11450 (2024).

Hoeller, D., Rudin, N., Sako, D. & Hutter, M. Anymal parkour: Learning agile navigation for quadrupedal robots. Sci. Robot. 9, eadi7566 (2024).

Schaal, S., Ijspeert, A. & Billard, A. Computational approaches to motor learning by imitation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 358, 537–547 (2003).

Kober, J. & Peters, J. Imitation and reinforcement learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 17, 55–62 (2010).

Sergey Levine, T. D., Chelsea, F. & Abbeel, P. End-to-end training of deep visuomotor policies. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 1–40 (2016).

Bin Peng, X. et al. Learning agile robotic locomotion skills by imitating animals. Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS), Virtual Event/Corvalis, 12–16 (2020).

Zhang, H., Starke, S., Komura, T. & Saito, J. Mode-adaptive neural networks for quadruped motion control. ACM Trans. Graph. 37, 1–11 (2018).

Kearney, S., Li, W., Parsons, M., Kim, K. I. & Cosker, D. Rgbd-dog: Predicting canine pose from rgbd sensors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 8336–8345 (2020).

Shooter, M., Malleson, C. & Hilton, A. Digidogs: Single-view 3d pose estimation of dogs using synthetic training data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV) Workshops, pp. 80–89 (2024).

Han, L. et al. Lifelike agility and play in quadrupedal robots using reinforcement learning and generative pre-trained models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 787–798 (2024).

Khosla, A., Jayadevaprakash, N., Yao, B. & Fei-Fei, L. Novel dataset for fine-grained image categorization. In First Workshop on Fine-Grained Visual Categorization, IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (Colorado Springs, CO, 2011).

Cao, J. et al. Cross-domain adaptation for animal pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pp. 9498–9507 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. Apt-36k: A large-scale benchmark for animal pose estimation and tracking. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 17301–17313 (2022).

Mathis, A. et al. Deeplabcut: markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1281–1289 (2018).

Nath, T. et al. Using deeplabcut for 3d markerless pose estimation across species and behaviors. bioRxiv (2018).

Joska, D. et al. Acinoset: A 3d pose estimation dataset and baseline models for cheetahs in the wild. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 13901–13908 (2021).

Bala, P. et al. Automated markerless pose estimation in freely moving macaques with OpenMonkeyStudio. Nat. Commun. 11, 4560 (2020).

Zhang, L., Dunn, T., Marshall, J., Olveczky, B. & Linderman, S. Animal pose estimation from video data with a hierarchical von Mises-Fisher-Gaussian model. In Banerjee, A. & Fukumizu, K. (eds.) Proceedings of The 24th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, vol. 130 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 2800–2808 (PMLR, 2021).

Ionescu, C., Papava, D., Olaru, V. & Sminchisescu, C. Human3.6m: large scale datasets and predictive methods for 3d human sensing in natural environments. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 36, 1325–1339 (2014).

Khanam, R. & Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv:2410.17725 (2024).

Ultralytics. Dog-pose dataset - ultralytics yolo documentation https://docs.ultralytics.com/datasets/pose/dog-pose/ (2025).

Pavllo, D., Feichtenhofer, C., Grangier, D. & Auli, M. 3d human pose estimation in video with temporal convolutions and semi-supervised training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 7753–7762 (2019).

Gosztolai, A. et al. LiftPose3D, a deep learning-based approach for transforming two-dimensional to three-dimensional poses in laboratory animals. Nat. Methods 18, 975–981 (2021).

Zhao, L., Peng, X., Tian, Y., Kapadia, M. & Metaxas, D. N. Semantic graph convolutional networks for 3d human pose regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 3425–3435 (2019).

Yu, B. X. et al. Gla-gcn: Global-local adaptive graph convolutional network for 3d human pose estimation from monocular video. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 8818–8829 (2023).

Luo, Z., Xiao, E. & Lu, P. Ft-net: Learning failure recovery and fault-tolerant locomotion for quadruped robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 8, 8414–8421 (2023).

Xiao, E., Dong, Y., Lam, J. & Lu, P. Learning stable bipedal locomotion skills for quadrupedal robots on challenging terrains with automatic fall recovery. npj Robot 3, 22 (2025).

Ye, S. et al. Superanimal pretrained pose estimation models for behavioral analysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 5165 (2024).

Kuhn, H. W. The Hungarian method for the assignment problem. Nav. Res. Logist. Q. 2, 83–97 (1955).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv:1609.02907 (2016).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 770–778 (2016).

Hwangbo, J. et al. Learning agile and dynamic motor skills for legged robots. Sci. Robot. 4, eaau5872 (2019).

Luo, Z. et al. Moral: Learning morphologically adaptive locomotion controller for quadrupedal robots on challenging terrains. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 9, 4019–4026 (2024).

Peng, X. B., Ma, Z., Abbeel, P., Levine, S. & Kanazawa, A. Amp: adversarial motion priors for stylized physics-based character control. ACM Trans. Graph. (ToG) 40, 1–20 (2021).

Escontrela, A. et al. Adversarial motion priors make good substitutes for complex reward functions. In 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), pp. 25–32 (IEEE, 2022).

Tobin, J. et al. Domain randomization for transferring deep neural networks from simulation to the real world. In 2017 IEEE/RSJ international conference on intelligent robots and systems (IROS), pp. 23–30 (2017).

Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: an imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Advances in neural information processing systems, 32 (2019).

Makoviychuk, V. et al. Isaac gym: High performance gpu-based physics simulation for robot learning. arXiv: 2108.10470 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by General Research Fund under Grant 17204222, and in part by the Seed Fund for Collaborative Research and General Funding Scheme-HKU-TCL Joint Research Center for Artificial Intelligence.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.L. proposed the initial idea of the research. L.Z. and Z.L. implemented all the software modules. The experiments were designed and performed by L.Z. and Z.L. with the assistance of Y.H. and J.Z. The manuscript was written by L.Z., Z.L., P.L. and Y.C.; P.L. provided the funding and supervised the research. Y.L. provided comments and suggestions in the writing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, L., Luo, Z., Han, Y. et al. Learning aggressive animal locomotion skills for quadrupedal robots solely from monocular videos. npj Robot 3, 32 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00048-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00048-x