Abstract

Ray-inspired robots show promise in ocean exploration and monitoring because of their potential for efficient locomotion, maneuverability, and stability in aquatic environments. This review explores recent progress in ray-inspired robotics, focusing on trends in locomotion modes, actuation types, and control and sensing strategies. We identify current challenges and performance gaps, list useful metrics, and suggest promising research directions that could improve and expand the capabilities of batoid robots.

Similar content being viewed by others

Motivation and background

Ocean exploration, bio-inspired robots, and batoid rays

The world’s oceans are home to multitudes of species and play an important role in Earth’s climate, economy, and transportation systems. However, the oceans currently remain largely unexplored and unmapped, with only 26.1% of the ocean floor publicly mapped at a resolution of 400 × 400 m as of October 20241. Current ocean monitoring systems mainly include satellites, aircraft, buoys, surface craft, underwater gliders, and tethered underwater stations2. Many of these monitoring methods function at or near the ocean’s surface, limiting their ability to gather data about the status of the ocean far below the surface. Alternatively, uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUVs), autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), and remotely operated vehicles could be used to expand the range of underwater exploration and monitoring. Current systems can travel to depths thousands of meters below the surface and operate continuously with sensor payloads for over 24 h3,4,5,6.

However, many vehicles and robots still face limitations in efficiency, noise, and maneuverability that are important to maintain long-distance autonomous missions with minimal disturbances to the environment. In contrast, aquatic organisms have already been refined through natural selection to exhibit these characteristics. Taking inspiration from such organisms can create bio-inspired aquatic robots with better efficiency, lower noise, and greater maneuverability compared to conventional robotic systems7,8.

Existing bio-inspired aquatic robots draw inspiration from many sources, including aquatic organisms that swim with fins (tuna)9, flippers (turtles and seals)10,11, and jet-propulsion (jellyfish and squid)12,13,14,15,16. Among these organisms, batoid fishes (i.e., rays and skates) specifically present numerous desirable characteristics for robotic locomotion. For example, batoids are both fast and maneuverable. Rays can travel at ~2.2 body lengths per second (BLs−1)17, which is faster than conventional propeller-based UUVs that move at 1 to 1.5 BLs−1 3,4,5,6. Their two pectoral fins are controlled independently, allowing rays to turn in place or swim backward7,18. Manta rays also reach an estimated Froude propulsive efficiency of 89%, while providing a stable platform that can resist disturbances like waves19,20. Pelagic rays have been observed modifying their swimming behavior when waves pass over them from behind, harnessing the water’s forward momentum to increase their swimming speed. Benthic rays can hold their position underwater by maintaining contact with the seafloor to increase friction, minimizing the compensatory fin motions needed to stay in place21. Batoid-inspired robots could employ these behaviors to outperform conventional UUVs in strong currents. With wide pectoral fins connected to a stable central structure, batoids have a shape conducive to constructing AUVs with a central waterproofed hub for electronics and actuators. These hubs could house downward-facing sensors (such as sonar) better than slender-bodied conventional and bio-inspired AUVs because of their orientation and aspect ratio. Finally, the large size variation of biological rays (13.5 to 900 cm width)20,22 and diverse set of swimming modes indicate that ray-inspired robots can be effective in a wide range of AUV applications23.

Other bio-inspired robots using a single caudal fin reached higher normalized speeds (4.7 BLs−1 9 versus 2.22 BLs−1 24) and faster turning speeds (670° s−1 25 versus 72° s−1 24) than the highest-performing ray-inspired robots. However, batoid-inspired robots offer clear advantages in maneuverability, efficiency in open water, stability in chaotic fluid conditions, and potential to operate in both benthic and pelagic environments.

Key design considerations

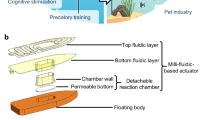

Much work has used batoids as inspiration for robots, but such robots vary depending on scale, application, or other key design considerations. One such consideration is the difference between undulatory and oscillatory locomotion. Undulatory locomotion is defined as finned propulsion with greater than one wave length per fin, as seen in Fig. 1ai. In contrast, oscillatory locomotion involves less than 0.5 wavelengths per fin, as seen in Fig. 1aii. Studies modeling batoid locomotion and relating phylogenetic trees to batoid shape support a correlation and potential benefit of varying aspect ratio relative to locomotion mode26,27.

a (i) Undulatory rays are generally more rounded and swim with greater than 1 wave present on the fin, (ii) while oscillatory rays are often more triangular and swim with less than 0.5 waves present along the fin. Disc width and length correspond to the width and length of the entire ray, excluding the tail, and span width and chord length correspond to the width and length of the fin. b (i) Many ray robots use pitching for propulsion, generally achieved using a flapping actuator and flexible fin material. (ii) Others use a bending actuator to achieve spanwise bending, and (iii) some robots use multiple actuators or harness material properties to achieve chordwise bending; some implement all three bending and pitching modalities. (i) The pitching diagram shows a side fin profile, (ii) spanwise bending shows a front fin profile, (iii) and chordwise bending shows a side profile. c (i) Ray robots require depth, velocity, and heading control accomplished by varying properties of wavelike actuation, such as frequency, amplitude, and phase offset. (ii) Sensing uses limited internal and external sensor types, including depth sensors, inertial measurement units (IMUs), gyroscopes, and optical sensors. d Various actuators include: (i) tissue engineered actuators (example in Fig. 4b); (ii) dielectric elastomer actuators (DEAs) (Fig. 5a and b); (iii) ionic polymer metal composites (IPMCs) (Fig. 5c); (iv) servos (Fig. 2); (v) hydraulically amplified, self-healing, electrostatic (HASEL) actuators (Fig. 5d); (vi) shape memory alloy (SMA) actuators (Fig. 4d); (vii) pneumatic and fluidic actuators (Fig. 4a, c); and (viii) tensegrity actuators (Fig. 3).

In nature, benthic batoids generally have smaller width-to-length aspect ratios, perform undulatory swimming (see Fig. 1ai), and are more efficient and controlled at slower speeds17,26. In contrast, pelagic batoids generally have larger aspect ratios and oscillate to swim (see Fig. 1aii), which improves lift and thus allows for higher speeds28. Some species like Gymnura micrura have intermediate morphologies with intermediate locomotion (between 0.5 and 1 wavelength per fin), and can shift between oscillations and undulations17. For robotic applications, tailoring both shape and locomotion mode could therefore potentially improve performance in the desired application.

For both oscillatory and undulatory locomotion, the type of bending involved in actuation is also relevant. Many batoid-inspired robots use a flexible pitching motion (Fig. 1bi), likely because of ease of construction. However, natural ray locomotion involves more bending than pitching, both in the spanwise direction (across the fin, Fig. 1bii) and chordwise direction (along the body, Fig. 1biii). While many ray robots have passive bending in these directions, few apply active bending in both spanwise and chordwise directions like natural rays do.

To achieve motion, ray-inspired robots use different actuator types, outlined in Fig. 1d. Servo motors (Fig. 1div) are the most common actuators and allow for simple and precise control of pectoral fins. However, servos can also be power intensive and have difficulty achieving spanwise bending of pectoral fins without the use of multiple actuators, bending mechanisms, or drivetrains that increase fin construction complexity. In addition to servo-based designs, many ray-inspired robots use other actuators that vary in scale and performance, including tissue-engineered actuators; dielectric elastomer actuators (DEAs); ionic polymer-metal composites (IPMCs); hydraulically amplified, self-healing, electrostatic (HASEL) actuators; shape memory alloys (SMAs); and pneumatic and fluidic actuators.

Because normalized speed is commonly reported for bio-inspired aquatic robots, this review will compare the performance of batoid-inspired robots based on this metric. However, we will use two different length scales to normalize the speed of batoid-inspired robots. We use body length (BL) as the length scale for robot descriptions and discussion of general field progression. For batoids and batoid robots, body length is equivalent to disc length (seen in Fig. 1ai). This scale uses body lengths per second (BLs−1) as the normalized speed, which is commonly reported in bio-inspired and batoid-inspired robot literature. To compare the performance of actuators and discuss general trends within batoid-inspired robotics, we define a characteristic length to calculate normalized speed and compare size regimes. Normalized speed in BLs−1 is useful to compare performance of many aquatic animals because of their long, streamlined shape. However, both fin width and length are relevant for flattened pectoral fin propulsion. Therefore, to better compare performance across current batoid robots, we use a characteristic length (CL) of \(\frac{1}{2}(W+L)\) to compare size regimes, and calculate normalized speeds using characteristic lengths per second (CLs−1).

Batoid-inspired robots face numerous common challenges in control, sensing, and navigation in underwater environments. To achieve robust control, most aquatic robots model their own kinematics and interactions with the surrounding fluid. However, current models only approximate the true forces involved and lose accuracy when the surrounding flow field becomes more complex29. AUVs often use acoustic or visual sensors to correct for such errors and enable local navigation, but typically, acoustic sensors have low resolution and visual sensors have limited range, especially in turbid conditions30. Bio-inspired sensors, such as electroreceptive or lateral line sensors, also show promise but have limited accuracy, sensitivity, and range. They also typically have high power consumption and large sizes30. Electromagnetic communication and GPS signals also have limited underwater travel distances. Lack of communication, along with unpredictable water currents, makes navigation and path planning a challenge. Various algorithms have been employed to overcome such challenges for general AUVs, but currently, algorithms still rely on assumptions about the AUV dynamics and surrounding environment, thus limiting their accuracy31,32,33.

These challenges and developments in control, sensing, and navigation also apply to batoid-inspired robots. Control methods used for other bio-inspired robots can apply to batoid-inspired robots because both use a form of oscillatory motion for propulsion34. However, the flattened geometry and pectoral fin-based locomotion of batoid robots require specialized methods of control. While most research on ray robots has focused on improving actuation and not control, nature-inspired algorithms like central pattern generators (CPGs) have improved control of ray robots. CPGs generate a wavelike pattern for open-loop control of oscillatory or undulatory locomotion based on desired parameters like speed, pitch, and yaw (Fig. 1c)35,36. Other research has used neural networks and optimization algorithms to improve the performance of CPGs and applied these CPGs to achieve classical and fuzzy logic-based closed-loop control37,38.

While aquatic robots have implemented a variety of sensors, ray-inspired robots have incorporated only a small number. Sensors used include inertial measurement units (IMUs), gyroscopes, depth sensors, and cameras (Fig. 1c) to control depth, orientation, and speed, and to detect and track targets. Although such sensors have enabled closed-loop control, expanding the sensing capabilities and combining sensing modalities in ray-inspired robots could improve autonomy and robustness for real-world applications.

Because implementing autonomous navigation for aquatic robots poses many challenges, little work has focused specifically on navigation or path planning for ray-inspired robots. Future batoid robots with robust, 3-dimensional, closed-loop control could implement navigation algorithms like those developed for general aquatic robots, even though their locomotion methods differ.

Scope

To follow a previous review about batoid robots in 201139, this review seeks to describe recent developments in ray-inspired robots and discuss design aspects, components, and performance trends. We will compare actuator type and performance; discuss control and sensing; highlight larger trends in locomotion mode, shape, and actuators; and suggest future directions, including useful metrics to standardize reporting of ray robots. This extends upon numerous recent reviews about aquatic robots that briefly highlight batoid-inspired robots.

Actuation and mechanical design

Servo actuation

Servos are one of the most common actuators in ray-inspired robots. They are used to actuate fins in four different ways.

Single-servo flexible fin

The most common design incorporates a single driving servo along the leading edge of a flexible fin (Fig. 2a), which passively deforms underwater following the servo’s motion. By tuning the fin dimensions, material properties, and leading edge actuation behavior, both oscillatory motion and undulatory motion can be achieved.

a Robots actuated with a single-servo for each fin41, b robots using multiple aligned servos to achieve active chordwise bending47, c robots with complex mechanisms using multiple servos to achieve active chordwise and spanwise bending62, and d robots that use a drivetrain to achieve chordwise bending with two actuators56.

For example, one robot achieved oscillation using fins attached to the central body at both the leading and trailing proximal corners. A single servo actuated a thin carbon fiber rod spanning the fin’s medial chord length, driving both pitching and heaving motions. This robot achieved one of the highest normalized speeds of any batoid-inspired robot at 1.4 BLs−1 40. Other robots used a similar fin structure, but without the attachment to the robot body at the proximal trailing edge of the fin (see Fig. 2a). With this construction, researchers tuned the fin locomotion profile by varying the fins’ thickness and material properties to achieve two of the highest normalized speeds: 1.5 and 1.78 BLs−1 41,42. Single servo robots have also tuned their fin material, shape, and thickness to support undulatory motion. These undulatory robots were modeled after benthic rays, with fins connected to their body along the entire proximal edge (see Fig. 1ai). While slower than their counterparts with higher fin span-to-chord aspect ratios, these robots reached speeds of 0.35, 0.37 and 0.93 BLs−1 43,44,45. Both undulatory and oscillatory robots with single servo-driven flexible fins rely in part on passive fin deformation to generate forward thrust. The undulatory fins, however, might suffer from more deformation-driven energy losses than their oscillatory counterparts, leading to slower normalized speeds.

The simplicity of single-servo actuated fins allows for high speeds but low manipulability. Because the actuator rods lie only along the leading edge of the fin, robots cannot generate reverse waves to travel backwards or turn in place. Both undulatory and oscillatory robots of this type typically lack active spanwise bending, and may be more limited in efficiency and maneuverability19. Despite these drawbacks, single-servo ray robots offer many promising qualities. A simpler fin design can simplify manufacturing, and these robots have achieved higher speeds (up to 1.78 BLs−1)42 than many other ray-inspired robots. Therefore, implementing single servos shows promise as a cost-effective, efficient option for fast movement over long distances in open water.

Multiple aligned servos

In contrast to single-servo propulsion, many robots used multiple parallel servos aligned along the robot body to better emulate batoid fin locomotion profiles (Fig. 2b). Rods of varying lengths were attached to the parallel servos, creating a skeleton that spans the fin. Thin, elastic material connected these rods and formed the fin’s surface. This construction allows for actively controlled chordwise waves, in contrast to the passive waves created on single-servo robots with flexible fins. However, the smoothness of these actively driven waves can vary depending on the amount of slack in the spanning material, rod spacing, and wave speed.

An early example of a robot with this fin configuration implemented oscillatory motion to swim at 0.8 BLs−1 using three independently actuated rods spanned by a flexible material46,47. Other similar oscillatory robots used three48 or four49 independent rods per fin to achieve speeds of 0.96 and 0.50 BLs−1, respectively. While these robots were generally slower than many single-servo robots, most were more maneuverable and had more developed control.

Intermediate and undulatory batoid-inspired robots with multiple aligned servos swam at 0.2750 and 0.38 BLs−1 51, respectively. Circular undulatory robots with radially oriented servos reached speeds up to 0.18 BLs−1 52 and could move in multiple directions without turning because of their symmetrical shape. Similar to single-servo robots, undulatory multi-servo robots typically swam slower than oscillatory ones.

Other multiple aligned servo robots used two motors to pitch the front and rear of the fin at different phases53,54. Because fins on these robots were built with a flexible skeleton, differential pitching actively generated chordwise waves. Normalized speeds up to 1.0 BLs−1 were reached, which is faster than any other robot with multiple aligned servos, even though fewer servo motors were used54. This example highlights how the added complexity of multiple servos can limit robot speed. Despite this drawback, multi-servo ray robots benefit from more active fin manipulation, allowing for improved control and maneuverability. Furthermore, because robots with multiple aligned servos can control their wavenumber directly, both oscillation and undulation locomotion modes can be realized on the same robot.

Drivetrains and bending mechanisms

Batoid-inspired robots can also use drivetrains or bending mechanisms to achieve active chordwise and spanwise bending that is difficult to accomplish with rigid, fin-spanning rods (see Fig. 2d, c). Drivetrains allow a single motor to actuate a set locomotion pattern along the length of the fin, while bending mechanisms use kinematic devices to translate a servo’s rotational motion into active fin bending. Drivetrains have generated both oscillatory and undulatory motion55,56, and can integrate both spanwise and chordwise bending mechanisms56 without additional actuators. Though the motion profiles of drivetrains are typically nonadjustable, they can use fewer motors, thus improving efficiency and cost for large-scale implementation.

Bending mechanisms can be designed to support adjustable locomotion profiles that also better replicate fin motions seen in biological rays. Two such robots used aligned servos along their bodies to each actuate a multi-bar linkage bending mechanism, while allowing for variation of their fin motion profiles57,58. One of these robots swam at 0.97 BLs−1 and achieved rapid turning and diving rates58. Another bending mechanism uses two perpendicular servos: one that drives fin flapping and another that twists the fin along its spanwise axis59,60. This design has achieved speeds up to 0.96 BLs−1 59. Other robots used a servo that drove pitching rather than twisting, reaching speeds up to 0.17 BLs−1 61,62. This speed might be improved by using more flexible fin materials. Servos have also been integrated directly into bending mechanisms inside oscillatory ray-robot fins. This design was used by a robot that could both swim at 0.3 BLs−1 and walk underwater63. While slower than many other servo-actuated robots, this design could be used in amphibious scenarios because of its walking ability.

To summarize, bending mechanisms in batoid robot fins allow for normalized speeds comparable to but not as fast as single-servo robots. Using multiple servos can increase control and maneuverability. Though more limited in speed, the bending motion profiles more closely resemble natural ray motion, which might improve other metrics like efficiency.

Tensegrity and cable actuation

Tensegrity, a portmanteau of “tension” and “integrity”, describes structures held together by flexible cables connected to stiff beams. These structures can remain stationary or change shape when their flexible cables are contracted. In ray-robots, active tensegrity structures are integrated along the fin’s leading edge (see Fig. 1dviii) and their cables are typically actuated with servo-powered pulley systems. Tensegrity actuators offer high stiffness-to-mass ratios, large active deformation potentials, and low energetic costs39. Research on tensegrity actuators has ranged from design models39,64,65 to physical fins and whole robot prototypes.

An optimization tool created for designing tensegrity fins65 enabled researchers to design a tensegrity actuated batoid fin with sufficient manipulability. A follow-up study determined that multi-cable tensegrity designs had higher stiffness-to-mass ratios compared to those using single cables or strut-routed cables, influencing future cable routing strategies. It was also found that actuating the cables from a central structure near the fin base, rather than with actuators embedded in the fin, created lighter fins, thus decreasing energy costs and enabling faster fin movements66.

Further work developed a flexible fin from this tensegrity structure by integrating the tensegrity beam into the leading edge66. The flexible nature of the fin allowed passive undulations to travel along the fin’s chord length, following actuation of the leading edge67. While only a single fin was tested in a water tank, the fin achieved speeds of 2.5 fin lengths per second at an actuation frequency of 1.25 Hz for over 105 cycles67. Building from this work, other tensegrity robots (see Fig. 3a) reached speeds of 1.0 BLs−1 19 and 0.6 BLs−1 68. Both of these robots achieved normalized speeds comparable to servo-actuated robots, and potentially have enhanced swimming efficiencies because of the spanwise bending nature of tensegrity actuation.

Additional work has shown further potential using multiple parallel beams. Strategically changing the cable pretension of the beams in such a fin could tune the natural frequency of the fin to the desired actuation frequency. Although changing the tension in the cables also changed the span length of the fin structure by up to 7%, the natural frequency also changed by 43%. Therefore, a small change in span length could allow for a wider tunable range for fin actuation. Reducing the tension in the rear tensegrity beams also minimized back-to-front undulations, which improved locomotion by preventing forward wave propagation64. Therefore, tensegrity-actuated batoid robots show promise with fast speeds using spanwise bending, but single tensegrity fins are more commonly designed than complete robots. This discrepancy could be because tensegrity fins require more components and complex control mechanisms than servo-actuated robots.

In contrast to tensegrity structures, cable-actuated robots alone are simple to construct while retaining some positives of tensegrity robots. Recent work used two antagonistic cables as one actuator, so the entire actuator bent toward the direction of the shortened cable while the other cable lengthened. A fin undulated similarly to benthic rays by arranging five of these actuators along the chord of a stingray-inspired fin69. Another cable-actuated robot connected rigid airfoil cross-sections with cables to allow for spanwise and chordwise bending. This robot swam at 0.82 BLs−1, comparable to the fastest tensegrity robots70. Overall, although tensegrity and cable-based actuation add complexity to the systems, these actuators serve as a promising avenue to achieve both spanwise (Fig. 3b) and chordwise bending by mimicking natural ray swimming to achieve higher efficiencies.

Pneumatic and fluidic actuation

Instead of servos, many batoid-inspired robots use air or fluid pressure to actuate along the leading edge of the fin, multiple locations along the chord, or built-in soft robotic pads that allow active spanwise and chordwise bending. Pneumatic robots generally exhibit flexibility and compliance because of the air compressibility, but are also usually tethered to an external fluid supply that limits the robots’ potential reach.

Early designs incorporated a soft, tube-like actuator along the leading edge of the robot fin. This actuator had a wall dividing the actuator, creating two separate cavities with varied air pressure to bend the tube. One 15 cm length robot swam at 0.67 BLs−1, demonstrating the fastest instance of a pneumatically powered robot71. While relatively slow, this robot showed how pneumatic actuation can be effective at small scales. Another robot used a pneumatic actuator to bend a flexible rib embedded in the leading edge of a cast silicone fin (Fig. 4a). The actuator contracted when its internal air pressure increased, storing energy in the bent flexible rib while bending the leading edge of the fin upward. After the actuator relaxed, the flexible rib moved downward toward its initial state, completing a fin oscillation for every contraction cycle. This actuator was implemented in multiple iterations of a robot, which achieved speeds up to 0.5 to 0.6 BLs−1 with the addition of a passive flexible trailing edge72.

a Pneumatic McKibben actuators120 and b tissue engineered robots75 both can be powered by contracting artificial or real muscles that store energy in a semi-rigid frame used to drive locomotion. c Robots using fluidic pads74 and d SMA actuators84 both exhibit slower actuation frequencies because of fluid and temperature system `inertia’.

Other pneumatic robots used more than one actuator per fin, such as one constructed by Urai et al. that had ten pneumatic fingers to drive slow undulatory motion at 0.08 BLs−1. Each finger contained six tendon-actuated joints, actuated by pneumatic pistons, which allowed the fingers to actuate adaptively when in contact with an obstacle73. More recently, soft robotic pads allow bending in both spanwise and chordwise directions (see Fig. 4c)74. These pads cover the majority of each fin, with passive flexible flaps on the trailing edges. Initially, durability issues prevented repeated use of the pad at higher fluid pressures, but wrapping the pad in fiber helped mitigate these issues. By changing the locations of the fabric, the pad could also be built to flex in different directions. An untethered robot using these pads swam up to 0.34 BLs−1 at 0.25 Hz with a maximum propulsive efficiency of 21%74.

Nevertheless, the majority of such robots require tethering, which is the most substantial challenge for pneumatic and fluidic batoid robots. Many use cases require traversing large distances, making tethered robots difficult to use. Therefore, while the soft robotic pad robot may have a lower normalized speed than other pneumatic and fluidic ray-inspired robots, the ability to move without a tether may make this design style more promising for some future applications. Another challenge for larger pneumatic and fluidic robots is increase in time that larger fluid volumes take to pump, which can slow actuation frequency and limit robot speeds at larger sizes74. However, the ability to achieve spanwise and chordwise bending motion could improve swimming efficiency.

Tissue actuation

Another method takes further inspiration from biology by incorporating living muscle cells as the actuators of batoid-inspired robots using electrical or light stimulation. However, because muscle cells require specific laboratory conditions to remain viable, tissue-engineered robots are constrained to swimming inside cell media and limited in size, orders of magnitude smaller than other ray-inspired robots. The biology of the muscle cells also limits actuation frequency and range of motion, although this could potentially be addressed in the future to be more comparable to muscles in biological rays.

One example of a tissue-engineered robot (Fig. 4b) used a ring of mammalian cardiomyocytes (built at a single cm scale) stimulated by four sets of external opposing plate electrodes in a circular 100 mm Petri dish. The cardiomyocyte ring deformed a polydimethylsiloxane skeleton, which stored and released energy upon muscle relaxation75. This cycle drove fin flapping to result in forward motion at 0.0054 to 0.0078 BLs−1, a low speed compared to other types of ray robots75.

Another tissue-engineered robot used rat cardiomyocytes stimulated by light rather than voltage potentials76 to mimic the undulatory motions of benthic rays, sequentially contracting to form a traveling wave. The robot traveled at an average rate of 0.09 BLs−1 over 250 mm, and was able to turn at a rate of 2° s−1 by changing the intensity of light asymmetrically76.

With the emergence of tissue engineering for biohybrid robots, future research can work toward creating free-swimming robots using biological muscle actuators. Compared to other batoid-inspired robots, tissue-engineered robots were much smaller and achieved slower swimming speeds, but still remained untethered during free swimming. Despite slower speeds, their velocities were still close to those of animals at comparable scales76. However, a remaining challenge is to develop tissue actuators that can survive outside of laboratory conditions and potentially operate at larger scales.

IPMC actuation

IPMC actuation is another method of soft actuation applied in ray-inspired robots. These actuators function using an ion-exchange membrane sandwiched by thin rare metal electrodes. Voltage applied across the electrodes causes hydrated cations to move towards the anode, simultaneously expanding the anode side and contracting the cathode side to bend the structure (Fig. 1diii)77. A previous review discussed IPMC-actuated ray-inspired fins prior to 201178, which include an undulatory counterbalanced fin that swam at 0.241 BLs−1 77, multi-modal robot that swam at 0.053 BLs−1 79 (see Fig. 5c), and oscillatory robot at 0.067 BLs−1 80.

While this research showed that IPMCs could be used for different modes of actuation, IPMC has not been commonly used in ray-inspired robots. Nonetheless, one recent tethered robot combined multiple long IPMC actuators and shape memory properties to shift between oscillatory and undulatory motion81. Although no swimming speeds were reported, this robot demonstrated how combining multiple types of actuation could lead to more versatile robots.

Therefore, IPMCs offer a functional mode of actuation at smaller scales, although robots using these actuators are generally slower compared to other batoid-inspired robots.

SMA actuation

SMA actuators work by laying SMA wires on an elastic substrate. When current is run through the wires, the SMA heats, changes shape, and bends the fin (see Fig. 1dvi). These systems produce a relatively high force output using simple construction, but also rely on cooling to return to their initial state which limits actuation frequency82.

The first SMA actuator-driven ray robot was designed in 200283, with improvements made in 2009 to achieve speeds of 0.43 BLs−1 by using an SMA actuator on the leading edge of the fin to generate oscillatory locomotion (see Fig. 4d)84. A similar project achieved a normalized speed of 0.36 BLs−1, and also used tuning of fin materials to achieve both oscillatory and undulatory locomotion82. Limited actuation frequencies resulted in relatively low normalized speeds, but SMA-actuated robots may be useful at smaller scales or incorporated into other forms of actuation81.

DEA actuation

More recent development of smaller-scale ray robots has focused on DEAs, which involve a dielectric elastomer sandwiched by two flexible electrodes (see Fig. 1dii)85. When a voltage is applied to the electrodes, the Maxwell stress attracts the two electrodes and expands the elastomer85, which translates to flapping motion using dielectric elastomer minimum energy structures (DEMES)85. DEMES are built by pre-stretching the elastomer and excising an elliptical shape, which forms a bent minimum-energy structure when the stretching force is released. When a high voltage is applied, the elastomer expands toward an unbent configuration to allow repeated bending85.

In 2020, researchers implemented DEA locomotion by modifying DEMES for aquatic environments. Because bare electrodes short circuit in saltwater and additional insulation decreases flexibility and performance, each electrode was sandwiched between two layers of dielectric elastomer and grounded using the surrounding water. A small-scale (55 mm length, 8.4 g) tethered robot built with these actuators achieved 30° of spanwise bending actuation to swim at 0.71 BLs−1 using a simple manta-like flapping motion, faster than SMA or IPMC-actuated robots at similar scales85.

A soft deep-sea robot using a similar DEMES actuator was deployed successfully in the Marianas Trench at a depth of 10,900 m (see Fig. 5a)86. This robot was built with decentralized electronics and a dielectric elastomer (DE) designed for high-pressure, low-temperature environments86. While swimming speed decreased with increasing depth, even at a depth of 8 m, the robot swam at only 0.34 BLs−1 using a simple oscillatory flapping motion. Nevertheless, this demonstrates the potential to use DEAs in free-swimming robots and in extreme environments where other actuators might fail.

Furthermore, two robots used a single DEMES in the center of a manta-inspired flexible structure for actuation to achieve speeds of ~287 and 0.58 BLs−1 88, but both were tethered and relatively small (~587 and 15 cm88 in length, respectively). The body structure also did not have a central hub for electronics or incite turning. However, because the robots had larger DEMES relative to body size, these robots showed high speeds at small scales.

Finally, the most recent work with DEA ray-inspired robots focused on improving control rather than swimming speed. Instead of using DEMES, two stacked traditional DEAs were contained in a flexible tube within a flexible fin (see Fig. 5b), allowing for increased bending (up to 48°) by activating opposing DEAs89. Using bidirectional flapping, the robot achieved a swimming speed of 0.76 BLs−1 and turning speed of 17.1° s−1 89, demonstrating that DEAs can be used to build more maneuverable robots with simpler manufacturing methods, compared to pre-stretching.

So far, these robots have only implemented oscillatory locomotion, but increasing the number of actuators could allow for undulation in the future. However, DEAs do require high voltages (from 2.685 to 10 kV87), which has limited most DEA robots to tethered applications. DEA-actuated robots are also limited in size (5 to 11.5 cm in length), with the larger two examples having the slowest speeds (0.5888 and 0.34 BLs−1 86). Nevertheless, DEAs have shown consistent performance in variable pressures, temperatures, and salinities, demonstrating great potential in variable or extreme environments86,87.

Electrohydraulic (HASEL) actuation

Recently developed HASEL actuators (see Fig. 1dv) work by sandwiching one part of a fluid packet between two electrodes and applying a voltage across the electrodes. The fluid is pushed into the remaining pocket, which expands the membrane outward and causes contraction along the length of the actuator24 (see Fig. 5d). HASEL actuators require high voltage and produce relatively low forces, but allow fast and repeatable contractions that mimic natural muscles90. By using a liquid dielectric, HASEL actuators can also allow for self-healing from electrical damage90. Previously, a HASEL manta-inspired robot (5.05 cm long) achieved a swimming speed of 2.22 BLs−1 and a turning speed of 96.4° s−1, by attaching the actuators to a rigid arm with a passively flexible fin and using a novel encapsulation method to improve aquatic performance24. Although this robot was tethered, its high speed and maneuverability is promising for the development of future HASEL-actuated ray robots.

Ray robot control and sensing

The control of ray-inspired robots is challenging, especially when spanwise and chordwise bending are both incorporated. Most work has thus focused on actuation methods and only use open-loop control to generate a motion profile and perform turns. However, some researchers have developed closed-loop control of ray-inspired robots based on depth, velocity, and angular velocity measurements, which have been refined through different algorithms to optimize control. Additional work has focused on sensing, using optic flow or other visual sensing to increase autonomy.

Open-loop control

Motion profile generation varies in complexity because actuators have different levels of precision to track motion profiles. Most studies that involve one actuator per fin have used either a square wave or sinusoidal oscillator to elicit propulsion. One example of a square-wave input is a HASEL-actuated robot24, which implements an open-loop control scheme used in many soft-robotic actuators because complex actuation dynamics limit the ability to use more precise actuation. In contrast, many single-servo robots are easier to model and use sine wave oscillators for motion generation41.

Actuation beyond the use of a single oscillator is mostly limited to robots that use multi-servo actuators on each fin. Their motion profiles are designed to align closely with natural ray locomotion and generally allow more maneuverability. While single-servo actuated robots can achieve speed control and some level of pitch and yaw control, the use of multiple actuators allows for more direct control.

Velocity control depends on maximum tip speed, which varies with fin stroke amplitude and frequency91. Therefore, both single- and multiple-actuator fins can control this parameter. In contrast, yaw is accomplished using differential amplitudes and a chordwise phase difference between the two fins92. While amplitude difference alone can achieve yaw rotation, such rotation is relatively slow and accompanied by a body tilt and spiral descent92.

Using a switching approach, single-actuator robots can achieve yaw rotation at a slow pace. However, yaw control based on differential chordwise phase can perform faster yaw rotation by inverting the phase along one fin, thus reversing the direction of propulsion on that side92. While this method can overshoot, quicker yaw rotation is accomplished. Depth or pitch control is commonly achieved using tail fins36 or buoyancy control systems46,63, which use pumps to change the volume of internal water or air to modulate buoyancy.

Typically, CPG networks can be implemented to achieve motion profiles necessary for speed, pitch, and yaw control by varying oscillations in chordwise bending. A CPG network is an open-loop control scheme based on biological neural networks for oscillatory animal movement93, and operates by taking the desired amplitude, offset, frequency, and phase difference between each actuator as inputs to a dynamical system, and return a joint angle at each time step in order to control motor motion93. CPGs offer multiple advantages, including direct relationships between inputs and outputs (such as velocity and attitude)35. As a dynamical system, the output oscillation can respond smoothly to both continuous and instantaneous changes in input to return to a nominal state after disturbances91. Furthermore, the ability to vary the periodic oscillating function continuously allows increased robustness and capability for multi-modal locomotion93.

For ray locomotion, CPGs present specific advantages. Generation of a wavelike motion profile with phase offsets enables both undulation and oscillation through chordwise bending, and the relative simplicity allows discretization and implementation with a microcontroller for free swimming93. Because of these benefits, many researchers have developed, implemented, and improved CPG network open-loop control for ray-inspired robots46,47,94. Additional work further developed and implemented CPG control on an oscillatory manta-based robot using depth, yaw, and velocity as inputs35. A similar system achieved closed-loop control91 that was later optimized38, and other studies demonstrated CPG-based control of an undulatory robot95.

Another ray-inspired robot used CPG-based control to achieve both flapping and gliding in a ray-inspired robot96. In nature, oscillatory rays often glide with a positive dihedral (fins angled upward, rather than horizontally) while turning18,97, between strokes19, or passing through waves21. Gliding with a positive dihedral provides passive stability in roll21, minimizing the effects of disturbances like waves to potentially stabilize rays during turning. Additionally, gliding while turning or between active strokes might improve efficiency because of decreased muscle use. Therefore, adding gliding to robotic motion profiles could increase passive stability and improve efficiency.

Closed-loop control

While much progress has been made in open-loop control, few robots have implemented closed-loop control, which is particularly difficult because the flexible nature of the fins and complexity of the hydrodynamic environment make ray-inspired robots strongly coupled nonlinear systems36. While some modeling has been done on such systems, these models reflect more natural batoid anatomy and have not yet been applied to robot control27,98,99,100.

One popular method for ray robot control is fuzzy control, which avoids the difficulty of modeling such systems by decomposing input variables into separate regimes and using fuzzy logic rules to generate control outputs. One robot achieved response times as fast as 2 s for an angular heading disturbance of 48° through fuzzy yaw control91. Later work further improved fuzzy depth control by implementing Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy control neural networks. This control method involved a neural network that was trained using locomotion data drawn from robot testing. Then, the trained network used sensory input to generate required actuation angles and phase differences. These numbers served as inputs for a CPG, thus allowing closed-loop control37,101.

In addition, other closed-loop methods have been used. An example is shown in one robot, which switched between controlling yaw by varying phase difference and amplitude to achieve fast turning with minimal overshoot92. Another robot used a dynamic controller that input proportional, velocity, and differential, in addition to a fuzzy controller, to vary controller parameters.

Sensing

Current work on ray-inspired robots has focused mainly on propulsion rather than sensing. Consequently, few batoid robots have implemented sensors, and those that do typically only use depth sensors, gyroscopes, and IMUs36,91,92. Other batoid robots have incorporated laser distance sensors to measure robot pose relative to the sides and bottom of testing tanks36,101. These four types of sensors give information on position (depth and distance to walls), velocity, and angular velocity, which can be integrated to determine angular position. Batoid robots have used these sensory inputs for closed-loop control, i.e., heading (yaw), depth, and velocity. As discussed in the previous section, these desired control outputs are achieved by controlling flapping frequency, flapping amplitude, and phase offset between actuators for CPG-based motion.

Other work has used cameras not only for pose estimation but also path tracking. One study used a gimbaled camera to estimate the position of a simulated oscillating ray robot by measuring optic flow102. Another robot implemented a color-based binocular camera system that was adjusted for underwater operation to detect and track targets. Using the target position, the robot achieved tracking using multiple control modes. The system used a nonsingular, terminal, sliding mode controller based on conventional AUV dynamics models to output the desired yaw moment based on the angular offset of the target. For distance control, the robot used a proportional-integral-derivative controller to output the speed required to follow the target. The robot then converted desired yaw moment and speed into flapping amplitude and phase offsets using a fuzzy inference system103. This exemplifies how ray-inspired robots equipped with advanced sensing can perform increasingly autonomous actions. The addition of a higher quantity and diversity of sensors beyond cameras could allow for increased navigation robustness and better allow batoid-inspired robots to independently navigate ocean environments.

As batoid robots are deployed, the type of sensors used are important to how such robots can effectively monitor ocean environments. While not yet used in the field, one robot was fitted with a camera and lights for the purpose of exploring the seafloor, demonstrating another use for cameras on batoid robots63. Temperature, salinity, chemical, or other types of sensors equipped on future batoid robots in the field could provide additional environmental data.

Discussion

Field progression

Since the most recent review paper on ray robots78, batoid-inspired robots have gained popularity. While some robots have demonstrated faster speeds, maximum normalized speeds have not increased substantially (Fig. 6) because much focus has sought to implement novel actuators, improve control algorithms, or emulate natural ray motion, instead of outperforming previous swimming speeds. For example, one paper discussed how the constructed robot fixed errors with imbalance and improved control, while maintaining a similar speed46,104. Of the 47 robotic rays we reviewed, most were untethered (Table 1); however, many pneumatic, HASEL, and DEA robots remain tethered to supply fluid or obtain necessary high voltages. While tethered robots have many applications, some uses for batoid-inspired robots might require free swimming, which is a promising area of future research using more recent actuator classes.

Oscillatory and undulatory locomotion

Both oscillatory and undulatory locomotion patterns involve spanwise and chordwise displacements — however, more waves are present along the fin’s chord length in undulatory motion compared to oscillatory motion. Rays have been categorized as undulatory when at least one full wave is present along their fin chord and oscillatory when at most half a wave is present along their fin chord, though a full spectrum of wavenumbers has been observed for this group of fish17,105,106,107. In terms of locomotion modes, oscillatory robots and fins are more common than undulatory ones, as listed in Table 1. Perhaps this trend is present because of the desirable abilities of oscillatory biological rays (efficient, fast cruising and greater lift generation)108 although another factor could be the decreased complexity of oscillation over undulation. To achieve a high wavenumber required for undulatory motion, researchers must either tune the material of the robot’s fin for passive undulation or use multiple actuators along the entire fin chord length for active motion. Each of these cases leads to increased fin complexity compared to oscillatory robots.

Oscillatory and undulatory biological rays also differ in their fin anatomy. The skeletal structure of biological ray fins consists of many jointed, radially oriented, cartilaginous bones called radials. The joints between these individual radial bones only bend ~15°, though biological ray fins still have a large range of motion thanks to the high quantity of joints present in their fins. Additional fin flexibility is modulated by the bendable nature of the cartilaginous fin radials, each calcified in varying amounts and orientations to control radial flexibility. Cross bracing between the radials also exists in some ray species (mainly those which use oscillatory locomotion), providing another means of controlling fin flexion. Together, the joint arrangement, radial calcification, and cross bracing — each present in varying amounts across the fin — reinforce ray fins in areas which support large loads while still enabling flexibility in other areas that need it. Trends in the arrangement of these skeletal features have been observed as a function of locomotion profile: oscillatory rays have cross bracing and increased calcification in the medial portions of their fins compared to undulatory rays which usually do not exhibit cross bracing109.

Fin shape is also correlated with the locomotion mode28. In nature, oscillatory batoids are largely pelagic and spend more time cruising in open water compared to undulatory species17. This pelagic lifestyle involves traversal of large, open areas, especially during migration where rays may travel thousands of miles110. Because of this, these pelagic rays would benefit from a morphology and locomotion profile that minimizes drag while efficiently producing the thrust needed to cruise for long distances in open water. To support these swimming abilities, oscillatory rays usually have more swept back fin tips and triangular fin shapes with higher aspect ratios (above 2.6) compared to undulatory rays28. This fin planform morphology is thought to enhance lift-based thrust production while minimizing induced drag near the fin tips111,112 — however, recent experiments found that the leading edge sweep angle of flexible, batoid inspired fins does not significantly affect the thrust generation113. Oscillatory rays with high aspect ratio fins also perform banking turns at larger angles than their undulatory, lower aspect ratio counterparts, allowing oscillatory rays to maneuver more adeptly in the open water column18,28. Conversely, undulatory rays exhibit the ability to turn in place, supporting their tendencies to live along the seafloor7,18. These batoids generally have smaller aspect ratios and flatter profiles to reduce drag in chaotic environments like tidal areas and streams, and maneuver along the bottom surface and complex environments21,28.

To compare, most batoid-inspired robot papers do not report the exact planform area to calculate an accurate aspect ratio — defined as the disc width squared over the planform area (W2/A). However, most do report disc length and width to give a similar metric of disc width over disc length (W/L). Using the width and length measured from multiple natural ray species28, we calculate the mean W/L for both oscillatory and undulatory rays to determine the boundary between aspect ratio regimes, in which the standard deviation to each mean is equidistant. As shown in Fig. 7a, this boundary exists at ~1.35.

a The width:length ratio of biological oscillatory and undulatory batoid rays show a clear division between swimming modes at W/L = 1.3528. Width is defined as the distance from fin tip to fin tip, and length is the distance between the tip of the leading edge of the ray to the trailing edge of the fin disc (excluding tails). The boundary at 1.35 is calculated by varying from the mean of each group (1.07 for undulatory and 1.73 for oscillatory) by the same number of standard deviations (standard deviation of 0.142 for undulatory and 0.192 for oscillatory). b The speed versus W/L ratio of various batoid-inspired robots shows distinct aspect ratio regimes for undulatory versus oscillatory locomotion. The 1.35 boundary seen in natural rays is shown, which also separates the approximate regimes for robot locomotion17,19,24,40,41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,58,59,61,62,63,68,70,71,73,74,75,76,77,79,80,82,84,85,86,87,120,121,122,123,124.

Most ray-inspired robots also follow this trend (Fig. 7b) with some exceptions. One undulatory tissue-engineered robot had a higher aspect ratio than expected; however, tissue-engineered robots are on a smaller scale of ~1 cm in length, and demonstrate the potential of real muscles as actuators rather than focus on locomotion. Another discrepancy is that some oscillatory robots exist below the boundary; however, these are relatively close to 1.35, and could be because of different design choices. However, either by mimicking natural rays or through optimal testing, batoid robots follow similar trends to natural rays regarding aspect ratios for undulatory versus oscillatory locomotion. Thus, when designing robotic rays, this pattern should be considered when determining robot aspect ratio because oscillatory rays seem to benefit from a higher span-to-chord aspect ratio, and undulatory rays benefit from lower aspect ratios.

Further, while undulatory batoids generally exist on the seafloor or in more chaotic environments, batoid-inspired undulatory robots are commonly tested in still, open water. Future research could thus test undulatory versus oscillatory batoid robot performance near floors and in moving water, to compare to performance in open water to better understand the benefits and drawbacks of undulatory locomotion.

There also exist multi-modal robots, which strive to achieve both modes of locomotion; the existence of a boundary aspect ratio suggests an ideal target for such multi-modal robots, as demonstrated in one robot near this boundary. However, future work could expand on this by testing various aspect ratios or shifting between different surface profiles to work more efficiently in each regime.

Comparisons of actuator types

When comparing the normalized speed of robots relative to body size, different actuators typically operate in distinct regimes. As seen in Fig. 8, tissue-engineered robots generally operate on a much smaller scale (~1 cm) than other robots, with smaller normalized speeds because of biological and design limitations to incorporate muscle cells, as well as the increased effect of skin drag in Stokes flow. This provides a challenge to compare to other actuators, which do not operate at this size.

a Normalized speed (in CLs−1) versus CL shows differing levels of performance for different actuator types. These include tissue engineered (green), IPMC (pink), and SMA (yellow), with slower speeds at small scales, while DEA (dark pink) and HASEL (red) performed well at small scales. Tensegrity (blue) performed well at larger scales, pneumatic (orange) performed better at smaller scales, and servo (white) performed well primarily at larger scales. Biological rays (black) performed better than all ray-inspired robots. There is a gap in performance between CL = 15 to 35 cm, as seen in the grey section. There is also an upper bound (black dashed boundary) on robot performance because of servo limitations. Characteristic length (CL) is defined as \(\frac{{\rm{Width}}+{\rm{Length}}}{2}\) to account for discrepancies in aspect ratio between robots. b Normalized speed (CLs−1) versus CL for different servo actuator mechanisms, including a single-servo along the leading edge (SSLE), multiple aligned servos (MAS), and multiple servos with complex bending mechanisms (MSCB). Less complex single-servo robots show highest maximum speeds, indicating a tradeoff between complexity and performance. No drivetrain servo-driven robots reported sufficient data for inclusion in this plot17,19,24,40,41,42,44,45,46,58,59,61,62,63,68,70,71,73,74,75,76,77,79,80,82,84,85,86,87,120,121,122,123,124.

Increasing in size, another set of ray-inspired robots occurs between CLs of 5 and 15 cm. At this scale, robots are most commonly driven by electrostatic actuation, such as IPMCs, DEAs, and HASELs, as well as slightly larger SMAs. To compare, IPMCs have the lowest normalized speeds, likely because of their limited actuation frequencies and deflections (Fig. 8a). SMA actuators perform better, but also have a limited speed because of their limited actuation frequencies. For both SMA and IPMC actuators, the lower bandwidths are reflected in the lower mean frequencies (mean 0.67 Hz) compared to other (DEA and HASEL) small-scale electrostatic robots (mean 3.2 Hz).

Recently, small-scale robots have shifted from IPMC and SMA actuators to DEAs or HASELs (see Fig. 6). In addition to relatively low manufacturing complexity, DEAs also produce relatively large deflections that contribute to larger normalized speeds among small-scale robots85. However, DEAs require high voltages, have a low driving force, and typically have to be pre-stretched which increases manufacturing complexity24,85. While still requiring large voltages, HASEL actuators combine fluidic and electrostatic actuation to enable fast responses and large strains, low noise, and simple manufacturing24,90,114. For example, a HASEL-actuated ray robot showed a higher normalized speed compared to all other small-scale robots covered in this review. While this robot was tethered and had limited manipulability, the high performance of HASELs suggests their utility in future ray-inspired robots, especially as these actuators are further developed.

Servo-driven and pneumatic robots also exist at or near these small scales. Small servo-driven robots are all larger than 15 cm in CL and perform relatively poorly (less than 0.4 CLs−1) compared to larger scale servo-based robots, likely because of power limitations. In contrast, a small-scale pneumatic robot has a greater normalized speed (greater than 0.7 CLs−1) but remains tethered, with no pneumatic actuators onboard.

At larger scales (CL > 35 cm), ray-inspired robots are either servo-driven, tensegrity-driven, or pneumatic/fluidic. Pneumatic-driven robots possess the slowest normalized speeds, less than 0.4 CLs−1. The largest fluidic robot’s pumps were limited in volumetric flow rate which reduced the maximum frequency of the robot, thus limiting thrust74 and demonstrating how larger fluidics robots are limited by having to move greater fluid volumes. This effect is demonstrated in the three oscillatory pneumatic ray robots in Fig. 8a, which decrease in normalized speed with increasing size. Servos make up the largest group of large-scale ray-inspired robots because of their higher power output and better precision relative to other modes of actuation. Servo-actuated ray robots vary in complexity and mode of implementation, in which there is a tradeoff between complexity and normalized speed. Robots with the highest normalized speeds (above 1.2 CLs−1) have only one servo per fin, whereas even the fastest robots with more complex motion only reach 0.8 CLs−1 (Fig. 8b). While complexity might hinder performance, additional actuators enable more precise control and maneuverability, considering all batoid-inspired robots that have implemented closed-loop control have used multiple actuators per fin. This difference suggests that single-actuator robots may be more useful in open-ocean environments where high speeds are preferred and maneuverability is not necessary. In contrast, robots with more actuators may be better suited to navigate more complex environments where high maneuverability is required. Tensegrity-based robots also fit this trend and perform comparably to the fastest multi-servo actuated robots. Their use of spanwise bending could potentially improve efficiency and could be investigated in future work.

Additionally, biological rays outperform current ray-inspired robots (see Fig. 8a). This suggests that mimicking ray movement, structure, and control could further improve the normalized speed for robots.

Performance gaps and limitations

When comparing normalized speed (CLs−1 versus CL) in all batoid-inspired robots (see Fig. 8), a few trends emerge. Ray-inspired robots only exceed speeds of 0.5 BLs−1 in two regimes: at smaller scales (CL of 5 to 15 cm) dominated by electrostatic actuators, and a larger regime (CL of 35 to 75 cm) dominated by servos and tensegrity-actuated robots. The actuator diversity in each regime suggests that electrostatics perform better at smaller scales, while servos perform better at large scales. This relation corresponds with electrostatic versus electromagnetic scaling laws (electrostatic forces scale with length2 and thus perform better at smaller scales, while electromagnetic forces scale with length4 and are more effective at larger scales)115. The presence of these two regimes also reveals a gap in ray-inspired robot construction: no high-performing robots exist within the 15 to 35 cm CL range. This gap is not likely due to hydrodynamic conditions because many biological rays in this region have speeds exceeding 1.5 CLs−1 (Fig. 8a). Therefore, actuator limitations might affect robot size toward this divergence, or a research gap exists at this intermediate scale.

Another trend is that for larger-scale robots, normalized speed decreases with size above a CL of ~60 cm, and no robots over 70 cm in CL exceed a speed of 0.6 CLs−1. This could indicate another knowledge gap or limit in actuation because of the high torques required. The batoid robots at these scales exclusively use oscillation, in which the lift-based thrust is proportional to \({U}_{f}^{2}* {L}^{2}\), where Uf is the fin speed, assuming wing area scales with length squared. Uf scales with the f\(*\) A (frequency times amplitude) because the vertical velocity correlates to the lift produced in the propulsive direction. Thus, the propulsion scales with f2\(*\)A2\(*\)L2. The drag on the robot scales with U2\(*\)L2, where U is the velocity of the robot, assuming the cross sectional area scales with length squared. Setting the thrust equal to the drag, the relation U ~ f\(*\)A emerges to state that the speed of a robot is proportional to the fin tip speed f\(*\)A, consistent with the literature35. While robots differ in structure and efficiency, the maximum achievable fin speed for a given robot relies on the maximum torque that the actuators provide, as faster fin tip speeds correlate to larger forces on the fins.

Additionally, most ray-inspired robot papers test a variety of conditions and report the maximum speed, but for larger and higher performing robots, speed or thrust is shown at different amplitudes and frequencies40,42,46. Each of these cases reports consistently that speed or thrust increases with both amplitude and frequency. However, for the highest amplitudes and frequencies, there are diminishing returns for further increasing amplitude and frequency inputs, which indicate a limitation on actuation speed because of viscous resistance (Fig. 8a). This observation is further substantiated as multiple works mention actuator torque limitations35,42,46. Because the maximum normalized speed of robots decreases at larger sizes, and actuators are the main constraint on maximum speed for a given construction, larger robots are constrained by actuator limitations that reduce speed.

This trend is also substantiated by the finding that servo actuator torque scales with mass116. To illustrate, the constraint on normalized speed relative to size can be expressed by relating the scaling of hydrodynamic forces on the fin and actuator output forces. Hydrodynamic forces on the fin scale with L2\(*\)U2, from drag and lift, where the free stream velocity U is the speed of the robot. As discussed previously, for pectoral fin locomotion, both spanwise and chordwise lengths are relevant to propulsion; thus, the length used is the designated CL. Because servo actuator torque scales with mass116, we can relate the torque required to actuate the fin to implement a given speed to the maximum torque output of a servo for a given robot. Assuming mass is proportional to L3, reasonable for servos constructed with similar materials, we can obtain the relation \({{CL}^{3}}*{{U}^{2}}={C}*{{L}^{3}}\), where C is a constant and another CL is added to the left side to convert force to torque. This results in U2 = C, or U = K, where \(K=\sqrt{C}\). The constant K changes for each robot because of servo quality and the efficiency towards which torque is transmitted into thrust differing among robots. However, choosing the robot with the highest thrust-to-torque ratio40, we can plot a curve for speed normalized by CL, \(\frac{U}{CL}=\frac{K}{CL}\). This curve shows a general upper bound on normalized speed relative to size for batoid-inspired robots with servo-based actuation (Fig. 8a).

This potential upper bound illustrates how normalized speed could be limited by actuator performance at large sizes, and sets a target for the development of fins with improved hydrodynamic efficiency and actuators with better performance. Furthermore, while other forms of actuation lie within these bounds, other actuators may scale differently with size and perform better than servos at larger scales. Actuation at larger scales should be investigated to increase swimming speeds for the potential to cover larger areas for ocean monitoring and mapping.

Control and sensing

Open-loop control has been extensively developed for simple oscillatory robots using sinusoidal fin motion. The use of asymmetric oscillators and CPGs in addition to open-loop control have further aligned robot locomotion patterns with biological ray motions. Though less prevalent, closed-loop control of ray-inspired robots has achieved lower error in both yaw and depth modes: rise times as low as 3.5 s and 2.5 s have been achieved for a 90° disturbance in yaw and a 35 cm disturbance in depth respectively91,117.

Even with these achievements, there are still limitations to the controls implemented in ray-inspired robots. Robots with more developed control do not yet reach the speeds achieved by simpler single-servo robots. Furthermore, though closed-loop depth and heading control have been demonstrated for ray-inspired robots, closed-loop velocity control hasn’t been implemented, possibly because of the variable nature of batoid propulsion.

Closed-loop control is also generally limited to fuzzy control and generally does not take into account the dynamics of the system. While system dynamics are difficult to calculate because of flexible fin motion and added mass effects, some estimation beyond fuzzy logic could improve response times and reduce error. Many papers have developed dynamic models of batoid locomotion to study locomotion hydrodynamics27,98,99,100, but these models have not been utilized to develop control schemes for robots. Biological ray motion involves active spanwise bending20; however, many batoid-inspired robots that do implement control lack active spanwise bending, limiting their ability to use previously developed dynamic models of batoid locomotion. Instead, most rely on flexible rods to achieve passive spanwise bending, therefore utilizing a locomotion mode not entirely analogous to natural ray motion and not captured by corresponding models. This discrepancy presents a direction for future research in applying batoid swimming models to control of robots and implementing active spanwise bending capabilities.

Neural networks and machine learning methods have also improved ray-inspired robot control. For example, batoid robot motion patterns have been optimized by genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization to improve open-loop control96,118. Other batoid robots that used Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy control neural networks in combination with CPGs for closed-loop control achieved depth tracking, course correction37, and path following over a sloped surface101. Future work could use advancements in machine learning-based control in other AUVs, such as approximating unmodeled hydrodynamic forces, to develop more comprehensive batoid robot control systems119.

While both open and closed-loop control configurations exist for ray-inspired robots, few forms of sensing have been applied to such systems - beyond IMU and depth sensing, only optical sensing has been implemented. Additional modes of sensing, such as acoustic or bioinspired sensing, could aid batoid-inspired robots deployed in the field. Drawing from advancements in other AUVs30,36, integration of multiple sensing methods could increase sensing robustness to better enable autonomous navigation. Similarly, future work could use path planning and navigation algorithms developed for other AUVs to overcome challenges in communication and unpredictable flow31,32,33. Such developments could enable batoid-inspired robots to navigate and monitor marine environments more independently.

Conclusion

Batoid fish continue to serve as an aquatic robot inspiration source, driving the development of high-efficiency, high-stability, and low-disturbance platforms for ocean exploration. Ray-robot platforms have been developed at an increasing rate over the past few decades; these robots comprise a large diversity of shapes, locomotion modes, and actuators. These previously developed robots have followed key, informative trends which could influence future robot designs. For example, ray-inspired robots have generally followed the pectoral fin aspect ratio and locomotion style trends seen in natural rays: higher width-to-length aspect ratios are mainly seen in oscillatory rays whereas lower aspect ratios are seen in undulatory rays. Various actuation strategies are employed in ray-robots, with robot size and desired locomotion style serving as key factors in actuator selection. Actuators perform better at different scales, with HASEL actuators working best at smaller scales, and servo and tensegrity outperforming at large scales. Performance gaps exist at medium and very large robot scales, potentially due to actuator limitations. Aside from actuator improvements, there is a need to develop more closed-loop control of batoid-inspired robots.

Other trends also exist: oscillatory ray-robots outnumber undulatory robots, possibly due to the increased fin kinematic complexity seen in undulatory robots compared to their oscillatory counterparts. Still, further work should be done to develop undulatory ray-robots as their biological inspirations can maneuver with ease near the ocean floor and underwater structures. We have found that undulatory and oscillatory robots typically exist in different aspect ratio regimes; though future research could investigate how aspect ratio coupled with locomotion mode affects robot performance. External conditions — like flow, wall, and ground effects — also could unequally affect the performance of robots sporting various body shapes and locomotion modes. Furthermore, although some examples of multi-modal robots exist, only one lies in the intermediate zone between oscillatory and undulatory aspect ratios. If aspect ratio couples with locomotion style to impact performance, multi-modal robots may benefit from an intermediate aspect ratio or even a morphing fin design that optimizes the fin shape considering the locomotion mode.

Beyond robot shape, there are many avenues of research for different actuators. At smaller scales, electrostatic actuators — such as DEAs and HASELs — perform better, especially in driving simple oscillation. In addition, HASEL actuators could be used in more mechanically complex mechanisms or tensegrity structures, although the high voltages required for these actuators do present a challenge for future work. At larger scales, pneumatic, tensegrity, and servo-based actuators dominate. Servo-based robots are the most common; however, multiple actuators or mechanically complex mechanisms are required to achieve the fin motions displayed by biological rays. Still, some of the servo-based robots demonstrate faster speeds and utilize simpler, passively flexible fins, indicating a tradeoff between fin complexity and speed. While pneumatic and fluidic actuated robots are somewhat limited by pump size and speed at larger scales, other actuation mechanisms could support higher performance at these scales. Tensegrity-based structures are promising: they could be configured to more accurately reflect biological ray fin motion and potentially increase efficiency, while still achieving higher actuation frequencies than pneumatic and fluidic robots. Future work should report more data on propulsive efficiency and turning speed for different robot fin structures and motion profiles. Widespread use of these metrics would allow better analysis of different fin shapes and actuator performances across multiple studies, which could thus benefit the field19.

Few robots have been constructed at intermediate scales (CL of 15 to 35 cm), and no robots at this scale have achieved normalized speeds of over 0.5 CLs−1 — yet many biological rays exist at this scale and routinely achieve speeds greater than 1.5 CLs−1, suggesting that actuator torque limitations may be driving this performance gap. Another performance gap exists above CLs of 60 cm. This gap suggests that normalized speed is limited because hydrodynamic forces exceed actuator force capabilities. Future work could seek to target the established higher performing regimes that allow robots to achieve maximal speed. Studies could also expand into intermediate and large-scale regimes or improve the torque-to-thrust efficiency to exceed the current limitations for normalized speed. Constructing larger robots (CL > 60 cm) with multiple actuators could provide more torque, although this approach also adds complexity. Future research could focus on overcoming the current drawbacks of complexity by improving control of multiple actuators to better use the power contribution of each actuator.

Future work could expand closed-loop control of batoid-inspired robots beyond fuzzy control and take advantage of their inherent stability to improve control in chaotic environments. Other research could implement dynamic models of batoid locomotion for control and potentially bolster such models with machine learning methods. Batoid-inspired robots could also include larger and more diverse sensor arrays. For example, just as batoids in nature sense their environment with electroreceptors and mechanoreceptors distributed across their large planform areas, using bio-inspired sensing in ray-robots could improve their sensing capabilities. To further increase autonomy, ray-inspired robots could also draw on path planning and navigation algorithms developed for other AUVs.

As the development of ray-inspired robots continues to progress and expand to field applications — from search-and-rescue missions to ocean monitoring — we identify key trends, knowledge gaps, and promising directions for future work on batoid robots.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

S. 2030, Our Mission https://seabed2030.org/our-mission/ (2024).

Xu, N. & Dabiri, J. Bio-inspired ocean exploration. Oceanography 35, 35–48 (2022).

Industries, H. I. REMUS 100M Unmanned Underwater Vehicle Mine Countermeasures Variant https://hii.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/REMUS-100M-3-31-22_web.pdf (2022).

Industries, H. I. REMUS 300M Unmanned Underwater Vehicle Mine Countermeasures Variant https://hii.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/REMUS-300M-data-sheet_2025.pdf (2022).

Industries, H. I. REMUS 620 Unmanned Underwater Vehicle https://hii.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/REMUS-620_11-29-2023.pdf (2023).

Industries, H. I. New Generation REMUS 6000 Unmanned Underwater Vehicle https://hii.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/REMUS-6000-3-29-22.pdf (2022).

Salazar, R., Campos, A., Fuentes, V. & Abdelkefi, A. A review on the modeling, materials, and actuators of aquatic unmanned vehicles. Ocean Eng. 172, 257–285 (2019).

Fish, F. E. Advantages of aquatic animals as models for bio-inspired drones over present AUV technology. Bioinspiration Biomim. 15, 025001 (2020).

White, C. H., Lauder, G. V. & Bart-Smith, H. Tunabot Flex: a tuna-inspired robot with body flexibility improves high-performance swimming. Bioinspiration Biomim. 16, 026019 (2021).

Hwang, J. & Wang, W. D. Shape memory alloy-based soft amphibious robot capable of seal-inspired locomotion. Adv. Mater. Technol. 7, 2101153 (2022).

Song, S.-H. et al. Turtle mimetic soft robot with two swimming gaits. Bioinspiration Biomim. 11, 036010 (2016).

Xu, N. W. & Dabiri, J. O. Low-power microelectronics embedded in live jellyfish enhance propulsion. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz3194 (2020).

Xiong, X. et al. A Bio-Inspired Underwater Robot Inspired by Jellyfish (American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2023).

Muralidharan, M., Saini, P., Ameta, P. & Palani, I. A. Bio-inspired soft jellyfish robot: a novel polyimide-based structure actuated by shape memory alloy. Int. J. Intell. Robot. Appl. 7, 671–682 (2023).

Wang, Y., Zhang, P., Huang, H. & Zhu, J. Bio-inspired transparent soft jellyfish robot. Soft Robot. 10, 590–600 (2023).

Bujard, T., Giorgio-Serchi, F. & Weymouth, G. D. A resonant squid-inspired robot unlocks biological propulsive efficiency. Sci. Robot. 6, eabd2971 (2021).

Rosenberger, L. J. Pectoral fin locomotion in batoid fishes: undulation versus oscillation. J. Exp. Biol. 204, 379–394 (2001).

Parson, J. M., Fish, F. E. & Nicastro, A. J. Turning performance of batoids: limitations of a rigid body. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 402, 12–18 (2011).

Fish, F. E., Dong, H., Zhu, J. J. & Bart-Smith, H. Kinematics and hydrodynamics of mobuliform swimming: oscillatory winged propulsion by large pelagic batoids. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 51, 35–47 (2017).

Fish, F. E. et al. Hydrodynamic performance of aquatic flapping: efficiency of underwater flight in the manta. Aerospace 3, 20 (2016).

Fish, F. E. & Hoffman, J. L. Stability design and response to waves by batoids. Integr. Comp. Biol. 55, 648–661 (2015).

McEachran, J. D., De Carvalho, M. R., & Carpenter, K. E. Batoid fishes. in The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Atlantic, 1, 507–589 (FAO, Special Publication Rome, 2002).

Li, G. et al. Underwater undulating propulsion biomimetic robots: a review. Biomimetics 8, 318 (2023).