Abstract

The role of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) in depression and suicidality is multifaceted. This study examined whether distinct electrocardiography based ANS profiles exist, associated with a lifetime/recent at-risk cohort or a resilient group. Using data from 15,768 participants from the UK Biobank, four unique ANS activity patterns related to heart rate variability (HRV) measures were identified. Two specific clusters, both with low HRV, showed different risks: one characterized by high relative sympathetic tonus and lower breathing rate, indicated higher resilience with less likely depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts whereas another cluster with dominant relative parasympathetic activity and high breathing rate, aligned with greater depression and suicide attempt prevalence, potentially representing a high-risk cluster. Resilience to depression might be defined by different psychophysiological entities and coping strategies, where the resilient cluster might be characterized by cognitive coping strategies, and increased susceptibility might be linked to more rigid maladaptive coping strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression and cardiovascular diseases rank among the most prevalent disorders and vastly impact mankind’s health according to the WHO and other sources1,2. While both cardiac disorders and affective symptoms reduce life expectations on their own, it long has been argued that there might be an association between the two entities1,2. The interaction is mutual: Not only is the outcome of patients after myocardial infarction worse, when they suffer from depression3,4,5,6. The risk for myocardial infarction is increased about 30% in patients with a depressive disorder7 with a linear association between severity of depression and risk of cardiovascular diseases8. Conversely, myocardial infarction also increases the risk for depressive symptoms9,10. The linkage between depression and cardiac disorders has been traced down to inflammatory genesis, the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and eventually the autonomic nervous system (ANS)1,8. While humans are conscious of their central nervous system’s (CNS) activity, the actions of the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the ANS are subconscious. An increased sympathetic activity—or correspondingly a decreased parasympathetic activity—as assessed by heart rate variability (HRV) measures of the resting electrocardiogram (ECG) have been found in depressed patients compared to healthy controls1. While numerous studies indicate that depression corresponds with a reduction in total HRV power1,11,12, there is substantial evidence pointing to a specific decrease in High Frequency (HF) Power1,13,14, which serves as an indicator of parasympathetic activity15 in affective disorders. However, the interpretation of frequency-domain HRV markers has been subject to ongoing debate. Recent research suggests that HF power, while associated with vagal activity, may be influenced by respiration and other factors, limiting its reliability as a direct index of parasympathetic tone16. Additionally, the role of low-frequency (LF) power as a marker of sympathetic activity remains controversial. Some studies observe elevated values17,18, while others find no correlation or even report a decrease in patients with depression19. Moreover, LF power may primarily reflect vagally mediated baroreflex activity rather than pure sympathetic modulation16. These inconsistencies highlight the need to move beyond single HRV measures toward identifying distinct patterns that integrate multiple HRV parameters, providing a more holistic view of autonomic regulation. Nonetheless, other ANS indicators also demonstrate signs of diminished parasympathetic activity in depression. This includes decreased time-domain markers of parasympathetic activity like the standard deviation of all normal RR intervals (time between two successive R-waves of the QRS signal on the ECG) during 24 h (SDNN) and the root mean square of successive differences between normal heart beats (RMSSD)20,21,22, other increased frequency-based indicators of sympathetic dominance such as the LF/HF ratio23,24,25, and alterations in nonlinear markers26,27.

Similar patterns of increased heart rates (HR), amplified HF power, and diminished LF power were observed in conditions like schizophrenia28,29,30. Likewise, post-traumatic stress disorder31, autism32, and anxiety disorders33 exhibit analogous trends. Beyond these specific diagnoses, broader transdiagnostic symptoms, such as suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, correlate with diminished HF HRV and signs of increased sympathetic activity34,35. However, findings from electrodermal activity studies suggest that the autonomic response in suicidal individuals might be more complex than just increased sympathetic activity. Some research indicates that people at higher risk for suicidality may not show solely an increased sympathetic arousal but rather an initial sympathetic overactivity followed by compensatory hyporeactivity. Electrodermal hyporeactivity, reflected in reduced skin conductance responses, has been proposed as a potential trait marker for suicide risk in both unipolar and bipolar depression36. These findings highlight that ANS dysfunction in suicidality is not unidimensional but dynamic, potentially reflecting maladaptive stress regulation and impaired autonomic flexibility.

Consequently, the specificity of individual HRV measures as diagnostic or therapeutic predictors appears limited31. Moreover, remaining inconsistencies across findings invite to reevaluate previous concepts of increased versus decreased activity of the ANS by returning to understand it as a complex and dynamic biological system trying to maintain homeostasis. Thus, a major challenge in employing HRV parameters as diagnostic, prognostic, or theragnostic biomarkers is this lack of specificity. A potential solution may lie in discerning distinct patterns across multiple HRV metrics from the frequency, time, and entropy domains. It is imperative to investigate if specific, stable combinations of multiple HRV indicators exist and if these can be associated with symptoms in a given cohort. Should varied HRV patterns and clusters be identified in transdiagnostic or even healthy groups, and if these can be linked to symptoms like depression or suicidality, they might offer valuable clinical insights to steer treatment strategies. Furthermore, integrating a hierarchical organization for the interpretation of dysfunctional ANS regulation might allow for the detection of different biological coping strategies, mirroring the diverse spectrum of depressive disorders and their heterogenous treatment success.

The study’s main objective was to elucidate the relationship between distinct combinations and clusters of HRV activity parameters and symptoms of depression and suicidality, thereby eschewing traditional a priori diagnostic classification systems in favor of a transdiagnostic approach. This methodology aligns with the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework, which advocates for a biologically grounded understanding of mental disorders that transcends conventional diagnostic categories. Utilizing a comprehensive sample from the UK Biobank, we employed a machine learning model to explore empirically derived unique patterns in ECG-based HRV features, which we then linked to the degree of manifestation of recent and lifetime depressive and suicidal symptoms. Our aim was to explore whether specific clusters exist that might signify heightened or reduced susceptibility to these symptoms and to discuss diverse hierarchically structured underlying mechanisms. Results could enable better management of these symptoms and foster preventive strategies.

Methods

Subjects and UK Biobank

The UK Biobank37 is a large-scale health study that recruited around 500,000 individuals aged 40–69 years from the United Kingdom between 2006 and 2010. Participants provided extensive health information, including medical histories, and underwent various investigations. As part of this extensive dataset, ~50,000 subjects underwent a standard 12-lead resting state ECG as part of an imaging sub-study. We utilized the mental health questionnaires to assess psychiatric symptoms in participants concerning the depressive and suicidal syndromes. Intake of any medication was assessed, including pharmacological interventions that might impact the heart activity and the ANS. We assessed age at assessment, sex, and body-mass index (BMI).

From initial 50,784 ECG datasets available, duplicate records were eliminated (N = 41,760 unique subjects). Records where the deviation between the HR as given by the recording amplifier and the in-house calculated HR by the in-house algorithms exceeded 20% were removed (N = 38,979). Records with durations less than 20 s were excluded (N = 24,286) and finally participants were removed with missing data on outcome variables concerning suicidal or depressive symptoms or on HRV-indicator variables (N = 16,387). Further, individuals receiving psychopharmacological medication with potential influence on HRV parameters were excluded, leading to the participant count of 15,768.

Outcome measures

Mental health data were retrieved for each subject to reconstruct lifetime diagnosis or current depression severity or the occurrence of recent or lifetime suicidal symptoms. To assess lifetime depression the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (CIDI-SF38) was used. To diagnose depression, the CIDI requires at least one primary symptom (either persistent sadness or loss of interest), along with at least five additional symptoms (fatigue or low energy, changes in weight, changes in sleep, difficulty concentrating, feelings of worthlessness, or thoughts of death). These symptoms must persist for the whole or most of the day, on all or most days over a period of at least 2 weeks to indicate a change from the individual’s normal state, and lead to significant impairment in daily activities. CIDI items were binary-coded (yes/no).

Current depression symptoms were assessed using the 9-item self-reported Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-939). A total score (PHQ-9 sum) was calculated by summing up the following nine Likert-scaled items: “Feeling down, depressed or hopeless”, “Lack of interest or pleasure in doing things”, “Poor appetite or overeating”, “Feelings of tiredness or low energy”, “Trouble falling or staying asleep or sleeping too much”, “Feelings of inadequacy”, “Trouble concentrating on things“, “Changes in speed/amount of moving or speaking”, and “Thoughts of suicide or self-harm”. Based on this score, participants were categorized into five different levels of depression severity of “No or minimal symptoms” (0–4), “Mild depression” (5–9), “Moderate depression” (10–14), “Moderately severe or severe depression” (20 or higher). Symptoms of lifetime and current depression were analyzed using categories and scores as described above as well as symptom-wise separately. Moreover, lifetime suicidality was analyzed by using three binary-coded (yes/no) items: “Ever thought that life not worth living”, “Ever self-harmed”, and “Ever contemplated self-harm”. Information on sociodemographic status (BMI, age, sex, employment status, income) was assessed to characterize the sample.

ECG recording, processing, and HRV measures

Resting state ECGs from 50,784 participants were available. ECG recording took place at two different instances from 2014+ and from 2019+, using the ECG GE Cardiosoft Version 6. A 12-lead ECG was recorded following clinical routine parameters. For standardized assessment of ECG parameters, a 10 s strip of ECG activity was used. The results of this assessment served as control markers (e.g., HR) for the quality control of the automated HRV analysis. This analysis was done on longer recordings, with a minimum recording length of 20 s (mean: 24.23 ± 19.34), making the HRV parameter extraction more reliable.

Extraction of HRV parameters was done using HeartPy software (35,36) with python 3.6. Data was only used for further analysis, if the difference between the automated heart rate detection of the ECG GE Cardiosoft System and the HeartPy result did not differ ≥20% and were in a physiological range (35–150 bpm).

The following parameters were calculated for the time domain: beats per minute (BPM), standard deviation for intervals between adjacent beats (SDNN), root mean square of successive differences between adjacent R-R intervals (RMSSD), proportion of differences between R-R intervals greater than 20 ms or 50 ms (pNN20, pNN50) and median absolute deviation of heart rate (MAD); for nonlinear markers the standard deviations in two orthogonal directions of the Poincaré plot (SD1 and SD2); for the frequency domain40: the low frequency component power (0.04–0.15 Hz; LF), the high frequency component power (0.15–0.4 Hz; HF, the normalized low frequency power (LFnu) and the total HRV power (TP). Additionally, the breathing rate (BR) was assessed from the RR-peak interval changes using HeartPy. As such, BR was derived based on the respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), the natural fluctuation in heart rate due to breathing, where the HR increases during inspiration and decreases during expiration. To estimate BR, spectral analysis was applied to the RR tachogram, identifying the dominant frequency within HF band (0.15–0.4 Hz, corresponding to 9–24 breaths per minute).

Statistics

To efficiently illustrate the strength and polarity of linear relationships among HRV measures and between HRV and outcome variables, we utilized heatmaps (Fig. 1). We adopted a dual-criterion approach: initially, we eliminated HRV-related variables demonstrating a correlation of 0.8 or higher to preclude redundancies within the K-means clustering. Subsequently, we also discarded HRV features that lacked any correlation to outcome variables, as they failed to contribute meaningful insights regarding our research query. Doing so, we ensured that the included HRV features were methodologically robust and relevant to our research question while minimizing redundancy and statistical noise. The following parameters were kept: BPM, pNN20, pNN50, MAD, LF, HF, LFnu, TP, RMSSD, and BR.

BPM beats per minute, SDNN Standard deviation for intervals between adjacent beats, RMSSD Root mean square of successive differences between adjacent R-R intervals, pNN20/pNN50 Proportion of differences greater than 20 ms or 50 ms, MAD Median absolute deviation heart rate, SD1/SD2 Standard deviation in the two orthogonal directions of the Poincaré plot (for frequency domain), BR breathing rate, LF low frequency component power, HF High frequency component power, LFnu Normalized low frequency power, TP Total heart rate variability power.

After selecting the most relevant HRV features by removing highly correlated variables (≥0.8) and those uncorrelated with outcome measures, we imputed missing values using mean substitution to ensure a complete dataset. The selected variables were then standardized using the StandardScaler, ensuring equal contribution to the clustering process.

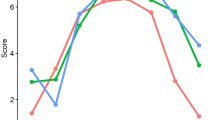

We applied K-means clustering, a widely used unsupervised machine learning algorithm, to identify underlying patterns within the data. To determine the optimal number of clusters, we iteratively ran K-means clustering (using Python’s scikit-learn library) with cluster counts ranging from 1 to 10, recording inertia (sum of squared distances from each point to its assigned cluster center). The optimal number of clusters was identified using the elbow point, where a clear decrease in inertia indicates a good balance between model complexity and explanatory power. Additionally, we calculated silhouette scores for cluster solutions between 2 and 9, providing an alternative validation metric that quantifies how well-separated the clusters are. Based on these evaluations, we selected a four-cluster solution and assigned each participant to a cluster using the K-means algorithm with 10–20 initializations to improve stability. The resulting clusters were analyzed by computing the mean values of the selected HRV parameters within each group, which were then visualized (Fig. 2). We also quantified the size of each cluster to reveal the distribution of data points. Further statistical analysis of clusters for associations with symptoms of depression and suicidality was done using STATA software (STATA/SE 16.1). Statistical analyses were adjusted for age, sex, and BMI to control for confounding effects21,41.

The plot displays the distortion scores (within-cluster sum of squares) for K-means clustering, with the number of clusters (K) ranging from 1 to 10. The “elbow point,” indicating the optimal number of clusters, is observed at K = 4, where the rate of decrease in distortion significantly slows down. This suggests that 4 clusters provide a suitable balance between model simplicity and accuracy for this dataset.

Results

Sociodemographic

The sample’s sociodemographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The participants were on average 64 years old. The average BMI was 26.5. The largest proportion of participants had an income ranging from £52,000 to £100,000. 53.2% of the sample was female, and most of the subjects (69.2%) were in paid employment or self-employed.

Distinct ANS clusters

K-means clustering algorithm was applied to the data set. As illustrated in the elbow plot (Fig. 2), the distortion score exhibited a pronounced decline as the number of clusters increased, yielding an inflection point (“elbow”) at K = 4, indicating the optimal trade-off between the number of clusters and the tightness of the clustering.

After the identification of four clusters as the optimal model for our dataset, clusters were characterized. Table 2 displays distributions of all study variables (all HRV variables—including those not in the model—and age, gender, and BMI) as well as a detailed comparison among the four clusters. Pairwise comparisons highlight where clusters significantly diverge (see Table 2). Across all clusters and variables, the HRS- or LRS clusters showed the highest or lowest values. The pairwise differences confirm that HP-Cluster consistently shows the greatest variability, particularly when compared to MP- and HRS-Clusters. The following clusters were delineated:

-

“Medium Parasympathetic Cluster (MP)” is characterized by a consistently medium parasympathetic activity with balanced sympathetic and parasympathetic tone.

-

“High relative Sympathetic Cluster (HRS)” has low HRV activity with a dominant sympathetic activation.

-

“Low relative Sympathetic Cluster (LRS)” has low HRV activity with a dominant parasympathetic activation.

-

“High Parasympathetic Cluster (HP)” is defined by the highest parasympathetic activation with balanced sympathetic and parasympathetic tone.

Association of classes with depression and suicidality

Table 3 displays the associations between ANS clusters and symptoms of depression. The LRS cluster exhibited higher proportions of all lifetime depression symptoms and had the highest proportion of subjects meeting the CIDI criteria for depression compared to others, in particular compared to those in the HRS cluster.

When analyzing symptoms related to recent depression, the LRS cluster had significantly higher core symptoms of recent depression, such as “lack of interest or pleasure in doing things” and “feelings of depression” as well as most other symptoms compared to others, especially against the HRS cluster. No significant differences among clusters were found for the symptoms “trouble concentrating on things”, “changes in speed/amount of moving or speaking”, and the item assessing recent suicidality. Furthermore, the LRS cluster had a significantly larger proportion of subjects with PHQ sum scores indicating mild to severe depression compared to the other clusters.

In terms of lifetime suicidality, individuals in the MP and LRS clusters more often reported suicidal thoughts, contemplations and actions than those in the HRS cluster.

Discussion

This work aimed at exploring the association between distinct HRV markers and symptoms of depression and suicidality in a large cohort of 15,768 participants derived from the UK Biobank37. Following an initial feature selection, we identified four clusters using a K-means clustering approach each characterized by a unique pattern of ANS activity. Of particular interest might be the HRS-cluster and the LRS-cluster: While both clusters show rather low HRV activity, the HRS-cluster shows a relatively high relative sympathetic tonus with comparatively lower BR, compared to the LRS-cluster with a dominant relative parasympathetic tonus and high BR. When comparing scores on depression and suicidality measures, the HRS-cluster appears to represent a population with higher resilience, whereas the LRS-cluster presented with the overall highest percentages on recent- as well as lifetime depression, characterizing a population at risk.

Previously, patients with depression showed reduced HRV measures1, like a reduced total HRV power1,11,12, often attributed to decrease in HF power1,13,14, indicating a reduction of parasympathetic activity15. Conversely, markers of sympathetic (over-)activity remain inconsistent. Noteworthy, an enhanced LF/HF ratio has frequently been reported indicating a sympathovagal dysbalance with a sympathetic dominance23,24,25. Despite only a few studies investigated ANS dysregulation specifically for suicidality, similar patterns have been found in patients with suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior42,43. A study from Rüesch et al. in a sample of patients after suicide attempt showed a pattern of reduced parasympathetic and sympathetic activity35. These previous findings are overall similar to our current transdiagnostic approach in a subclinical sample showing reduced HRV in participants reporting more lifetime depression and suicidality. However, contrary to previous findings in depression and suicidality, subjects at risk were characterized in parallel by low overall HRV power and by increased relative parasympathetic activity, whereas increased relative sympathetic tonus might correspond to stress resilience. HRV has been suggested to be a variable state biomarker of depression44,45, thus, different underlying mechanisms may come in play in a subclinical population.

The HRV can be considered a marker for the cardiovascular system to cope with physiological, but also psychological challenges that threaten homeostasis, i.e., the dynamic process of responding flexibly to external conditions with the aim to maintain the stability of the internal system. To do so, the brain constantly predicts metabolic needs while dynamically adapting to changing conditions by a process referred to as allostasis46. Notably, the set-point for allostasis is flexible, i.e., what might be appropriate at rest might not work during stressful situations, with allostatic load summarizing the cumulative effect of stress on the body47,48. Under stress, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) mobilizes physiological resources49, keeping the system at a state of higher vigilance and alertness towards threat. Contrarily, the parasympathetic nervous system helps downregulating the stress response50. Previously, a low HRV—as observed in the HRS and LRS-clusters—has been associated with a dysregulation of the homeostatic ANS functions reducing the ability to adapt to stressors51, i.e., contributing to an allostatic overload. Thus, a low HRV has been suggested to represent a psychophysiological biomarker for vulnerability to stress52.

In the context of our HRS- and LRS-clusters, their distinct ANS patterns may serve as indicators of varying physiological coping mechanisms to stress53, which must be conjointly interpreted as parts of a more complex system. While a dominant and high absolute sympathetic activation has been identified as a potential hallmark of psychological stress54, it has been suggested that parasympathetic activity may correspond to maladaptive psychological coping strategies, in particular associated with sad mood and rumination55. Likewise, the lack of resilience observed in the HP-cluster may be explained by fact that chronic parasympathetic dominance does not always indicate an adaptive state, but rather a rigid and passive coping strategy. Excessive parasympathetic activation in the absence of adequate sympathetic counterbalance may be associated with behavioral inhibition, withdrawal, and emotional bluntings, all of which are hallmarks of depression and anhedonia55,56,57. Furthermore, autonomic dysfunction in depression may not be solely defined by low sympathetic activity but also by the inability to flexibly shift between sympathetic and parasympthatetic states in response to environmental demands (according to the Neurovisceral Integration Model57), suggesting autonomic flexibility to be a key player for psychological resilience. In line with that, the HP-cluster may reflect a maladaptive autonomic profile characterized by low adaptability (i.e., passive stress regulation), rather than a resilient physiological state.

In contrast, the HRS cluster, despite its low overall HRV, displayed a relative balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity, potentially reflecting a more adaptive stress response. This resilience pattern must have an additional explanation. These findings may align with the hierarchical Bayesian perspective, describing the brain as an active inference generator at which predictions about the body’s upcoming metabolic, autonomic, and immunological needs (posterior) are made based on precise internal models (priors) that depend on past (aversive) experiences58. Predictions about incoming sensory input are compared to the actual physical state, representing the prediction error. To maintain stability, the body aims at minimizing the prediction error59, which depends on the (un)certainty of the prior beliefs and the (im)precision of the prediction error itself. It has been shown that rumination negatively impacts cognitive flexibility60, leading to increased activation of aversive memories and negative thoughts, and thus, building the prior beliefs/internal models about current life events based on depressogenic inferences61,62, resulting in rigid priors63. Therefore, under chronic hyperarousal, the Bayesian brain might rely more on its priors (foreseeing stress) rather than the sensory input. As a result, the body might constantly anticipate increased metabolic needs, leading the body to remain in a state of chronic alertness, which will eventually further increase the prediction error. The ANS may increase the parasympathetic tone to guide the body towards sickness behavior associated with fatigue and negative affect—initial symptoms commonly observed in depression64—with the ultimate goal to reduce the predicted increased metabolic needs65,66,67. The increased relative parasympathetic tonus—as observed in the LRS cluster—might result from ongoing attempt to downregulate the system as a consequence of chronic stress59, which ultimately is in line with the reported increased percentage of lifetime depression in this cluster. Therefore, the increased relative parasympathetic tonus might reflect a maladaptive/rigid physiological coping strategy, with the initial aim to counterbalance an overactive SNS but resulting in an overall dampened and rigid ANS with almost no possibility to reactivate the SNS in face of new threats. Such rigid priors might also be reflected in previous electrophysiological findings on vigilance states (i.e., alertness and wakefulness states as measured using electroencephalography (EEG))68. It has been observed that patients with depression exhibit “hyper-rigid” vigilance regulation, which decreased potential to change an ongoing brain state69,70.

On the contrary, the increased relative sympathetic tonus as observed in the resilient HRS-cluster might not necessarily represent a sympathetic over-reactivity but might rather reflect the absence of a relative parasympathetic overshoot71. To understand the apparent resilient nature of the HRS cluster, further insights on allostatic regulation might be achieved when considering the distinct breathing patterns at which the HRS cluster shows overall the lowest BR in comparison to all other clusters. In the face of ongoing stress, like depression or suicidal thoughts, relaxed breathing could dominate over a dampened ANS system. Previous research on respiratory rate in individuals with depression has yielded mixed results. While some studies found no significant differences in BR between depressed and non-depressed individuals72, others reported an increased BR in relaxed conditions among those with greater depression severity, suggesting an altered autonomic regulation of respiration73. These findings indicate that BR, while an important component of ANS assessment, may vary depending on individual physiological responses and methodological differences across studies. Thus, its interpretation should be considered within the broader framework of autonomic flexibility and stress regulation.

Although the breathing reflex is on a similar level as the ANS function, both originating from the brainstem and spinal nuclei, breathing rhythms can be controlled via CNS function, even consciously, while this is not possible for the heart rate and consecutively the HRV74. While respiration and cardiac activity exert bidirectional effects on each other (cardio-ventilatory coupling75), the influence of respiration is dominant, at which the ponto-medullary respiratory network exerts its influence on vagal influences but not vice versa76. Thus, the slow BR of the HRS cluster might reflect a certain top-down influence on the stress system, mirroring cognitive coping strategies. These top-down mechanisms in place might be the source of the resilient character of the HRS cluster with low BR, even in contrast to the MP and HP clusters. Taken together, these findings support the notion that resilience for depression and suicidal thoughts might arise from a tight and complex coupling of ANS subbranches and potentially top-down driven CNS coping strategies77. Taken together, these findings support the notion that resilience for depression and suicidal thoughts might arise from a tight and complex coupling of ANS subbranches and potentially top-down driven CNS coping strategies77. These concepts are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Visual representation of A low relative (LRS) cluster and B high relative (HRS) cluster. Chronic stress and depression are associated with a low heart-rate variability (HRV). A In the LRS cluster, rigid Priors based on depressogenic inferences lead to a hypervigilance state where a constantly increased metabolic need is anticipated (e.g, increasing breathing rate [BR]), which increases the prediction error. To minimize the prediction error, the parasympathetic tonus is elevated as a result from ongoing attempt to counterbalance an overactive sympathetic nervous system, guiding the body towards sickness behavior reflecting maladaptive physiological coping behaviors. B In the HRS cluster, the respiratory influences might dominate over the cardiac activity, eventually dampening the sympathetic activity, reflecting a top-down cognitive coping strategy. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

The clinical application of the various ANS regulation types identified in this study could be implemented through automatic labeling of routine ECG recordings, with classification into “at-risk” or “resilience” clusters72. Since ECG recordings are implemented as routine pipelines at psychiatric hospitals to rule out cardiac side effects due to psychopharmacological medications, this approach could be utilized within the framework of risk management to recommend urgencies for the development of emergency plans or to trigger additional crisis intervention discussions. From the perspective of a general practitioner, these ECG-based risk labels could help making the right decisions for the referral to a psychiatric specialist, where the threshold for someone belonging to the “at-risk” label should be lower than for someone belonging to the resilience cluster, while both patients otherwise share all features. While these different risk labels should surely not be the ultimate advisor for clinical practice, this information could be included into the multidisciplinary decision-making process to improve the way we prevent emergency situations like suicidality. However, for ANS-based screening the integration of additional electrophysiological markers beyond HRV (e.g., electrodermal activity) should be considered to increase specificity72. While these parameters are not yet routinely assessed in psychiatric care, advancements in wearable and digital health technologies may facilitate their incorporation into clinical practices78. Regarding treatment options, regulating sympathovagal dysbalance might be addressed using personalized HRV biofeedback79 or respiratory80 trainings to treat or prevent depressive symptomatology, which has shown promising results on reducing stress and anxiety in clinical81,82 and nonclinical81,83 populations.

Furthermore, these findings might provide important insights for pharmacological treatments in patients with depression. Thus, patients that responded to antidepressant treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were found to also show improved HRV parameters84. These findings highlight the need for personalized psychiatric treatment under consideration of distinct biomarkers. In line with hypervigilance states in depression, more probable treatment response to ketamine was found in patients with high EEG vigilance states85 and in patients with lower HRV86. While ketamine shows a sedating effect on the CNS, it shows activating effects on the ANS87. Thus, higher vigilance might be in line with rigid priors on a central level which will be attenuated by pharmacological effects of ketamine, allowing the parasympathetic regulation to act as a coping mechanism.

A critical question that arises is whether these markers represent a physiological trait, or if they vary with changes in symptomatology. Addressing this requires longitudinal data with multiple measurement points for HRV and psychiatric symptomatology, alongside knowledge of the interventions that have been applied. Should the markers prove to be responsive and modifiable, ECG marker-based therapeutic modalities could be developed to enable stratified therapy. This approach could significantly refine personalized treatment strategies, aligning therapeutic interventions more closely with the physiological profiles indicated by ECG markers.

This study has some limitations. The mean ECG recording duration was 24 s, which is shorter than the 5-min standard recommended for HRV analysis15,88. While some studies suggest that ultra-short-term recordings (10–30 s) can approximate HF power under stable conditions, they are generally less reliable for LF power and total HRV40. Furthermore, while BR was estimated from RR interval fluctuations using RSA, this indirect approach may have a larger error margin, particularly given the 24-s ECG recording duration. However, due to the large sample size, this estimation remains valuable for identifying general autonomic patterns, though future research should consider direct respiratory measurements for improved accuracy. Moreover, while HRV is widely used to assess autonomic function, it primarily reflects cardiac vagal modulation and provides limited insight into sympathetic activity. Recent research suggests that a more comprehensive evaluation of autonomic function should incorporate additional measures such as baroreflex sensitivity, blood pressure variability, electrodermal activity, and pupillometric indices72. Likewise, body position, daily time, consumption of alcohol/nicotine can affect HRV measurements41,89. However, these parameters were not available in the present dataset, which is why we focused on HRV-based features. In addition, the inclusion of multiple ANS-related parameters presents a fundamental dilemma in clinical research: while a more comprehensive autonomic assessment may improve specificity, it also increases variability and interpretational challenges due to multiple influencing factors such as test conditions, circadian rhythms, and individual physiological differences72. Further, the mean of ECG recording duration was 24 s. Although for some of the used measures a longer recording period of e.g., 2–5 min is recommended40, the number of datasets might outweigh outliers. However, the individual items were transformed, and outlier correction was performed beforehand. A strict exclusion of outliers has been performed by the statistical analysis, so the results can be regarded as reliable. Moreover, HRV-derived measures were not corrected for level of physical activity or BR90. Moreover, different breathing types91 or pulmonary volume might influence HRV-derived measures92. However, especially BR has been controversially discussed as being an integral part of the whole system53. Moreover, autonomic dysregulation might represent a feature of (susceptibility for) depression or might represent a consequence of being ill. Lastly, the suicidality and self-harm measures used in this study were derived from the UK Biobank’s standardized dataset, which is predetermined and not under researchers’ control. While these items are consistent with those used in large-scale public health research, their specific psychometric properties have not been independently validated.

In summary, diverse HRV clusters exist, which might contribute to different susceptibility to depression and suicidal features. A low HRV together with high relative sympathetic tonus and low BR might represent a resilience cluster activated as a result of a top-down modulated breathing rate exerting a dominant effect on vagal influences, reflecting a cognitively moderated coping strategy. On the contrary, a high relative parasympathetic tonus with high BR contributes to increased susceptibility as a result of hypervigilance representing a maladaptive physiological coping strategy. However, understanding potential resilience patterns requires further insights into allostatic regulation, particularly considering HRV regulation at various hierarchical neurophysiological and anatomical levels and reflecting on distinct breathing patterns. Taken together, proper functioning and CNS regulation of the ANS might be crucial to build effective resilience pattern towards depressive symptomatology during allostatic overload. Further studies should aim at adopting a comprehensive approach when analyzing HRV, considering all contributing factors, including their relative components. Furthermore, a longitudinal analysis is necessary to replicate and validate the herein presented findings, ensuring a robust understanding of HRV dynamics.

Data availability

The data used was received from the UK Biobank. Additional data can be received upon request from the authors.

Code availability

The code used for this analysis is available under https://github.com/webersamantha/ECG_Depression_Suicidality.

References

Kemp, A. H. et al. Impact of depression and antidepressant treatment on heart rate variability: a review and meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 67, 1067–1074 (2010).

Musselman, D. L., Evans, D. L. & Nemeroff, C. B. The relationship of depression to cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 55, 580–592 (1998).

Carney, R. M. et al. Depression, Heart rate variability, and acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 104, 2024–2028 (2001).

Carney, R. M., Freedland, K. E. & Veith, R. C. Depression, the autonomic nervous system, and coronary heart disease. Psychosom. Med. 67, S29–S33 (2005).

Cocchio, S. et al. Is depression a real risk factor for acute myocardial infarction mortality? A retrospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 19, 122 (2019).

Sundbøll, J. et al. Impact of pre-admission depression on mortality following myocardial infarction. Br. J. Psychiatry 210, 356–361 (2017).

Scherrer, J. F. et al. Increased risk of myocardial infarction in depressed patients with type 2 diabetes. Diab. Care 34, 1729–1734 (2011).

Brown, A. D. H., Barton, D. A. & Lambert, G. W. Cardiovascular abnormalities in patients with major depressive disorder: autonomic mechanisms and implications for treatment. CNS Drugs 23, 583–602 (2009).

Thombs, B. D. et al. Prevalence of depression in survivors of acute myocardial infarction: review of the evidence. J. Gen. Intern Med. 21, 30–38 (2006).

Schleifer, S. J. et al. The nature and course of depression following myocardial infarction. Arch. Intern Med. 149, 1785–1789 (1989).

Brown, L. et al. Heart rate variability alterations in late life depression: a meta-analysis. J. Affect Disord. 235, 456–466 (2018).

Jandackova, V. K., Britton, A., Malik, M. & Steptoe, A. Heart rate variability and depressive symptoms: a cross-lagged analysis over a 10-year period in the Whitehall II study. Psychol. Med. 46, 2121–2131 (2016).

Baik, S. Y. et al. The moderating effect of heart rate variability on the relationship between alpha asymmetry and depressive symptoms. Heliyon 5, e01290 (2019).

Koch, C., Wilhelm, M., Salzmann, S., Rief, W. & Euteneuer, F. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability in major depression. Psychol. Med. 49, 1948–1957 (2019).

Electrophysiology, T. F. of the E. S. of C. the N. A. S. of P. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation 93, 1043–1065 (1996).

Thomas, B. L., Claassen, N., Becker, P. & Viljoen, M. Validity of commonly used heart rate variability markers of autonomic nervous system function. Neuropsychobiology 78, 14–26 (2019).

Berger, S., Kliem, A., Yeragani, V. & Bär, K.-J. Cardio-respiratory coupling in untreated patients with major depression. J. Affect Disord. 139, 166–171 (2012).

Schulz, S., Koschke, M., Bär, K.-J. & Voss, A. The altered complexity of cardiovascular regulation in depressed patients. Physiol. Meas. 31, 303–321 (2010).

Guinjoan, S. M. et al. Depressive symptoms are related to decreased low-frequency heart rate variability in older adults with decompensated heart failure. Neuropsychobiology 55, 219–224 (2007).

Ha, J. H., Park, S., Yoon, D. & Kim, B. Short-term heart rate variability in older patients with newly diagnosed depression. Psychiatry Res. 226, 484–488 (2015).

Choi, K. W. et al. Heart rate variability for treatment response between patients with major depressive disorder versus panic disorder: A 12-week follow-up study. J. Affect. Disord. 246, 157–165 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Altered cardiac autonomic nervous function in depression. BMC Psychiatry 13, 187 (2013).

Kemp, A. H., Quintana, D. S., Felmingham, K. L., Matthews, S. & Jelinek, H. F. Depression, comorbid anxiety disorders, and heart rate variability in physically healthy, unmedicated patients: implications for cardiovascular risk. PLoS One 7, (2012).

Yeh, T.-C. et al. Heart rate variability in major depressive disorder and after antidepressant treatment with agomelatine and paroxetine: Findings from the Taiwan Study of Depression and Anxiety (TAISDA). Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 64, 60–67 (2016).

Terhardt, J. et al. Heart rate variability during antidepressant treatment with venlafaxine and mirtazapine. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 36, 198–202 (2013).

Yeragani, V. K. et al. Diminished chaos of heart rate time series in patients with major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 51, 733–744 (2002).

Leistedt, S. J.-J. et al. Decreased neuroautonomic complexity in men during an acute major depressive episode: analysis of heart rate dynamics. Transl. Psychiatry 1, e27 (2011).

Townsend, M. H., Baier, M. B., Becker, J. E. & Ritchie, M. A. Blood pressure, heart rate, and anxiety in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 151, 155–157 (2007).

Liu, Y. et al. Altered heart rate variability in patients with schizophrenia during an autonomic nervous test. Front Psychiatry 12, 626991 (2021).

Henry, B. L., Minassian, A., Paulus, M. P., Geyer, M. A. & Perry, W. Heart rate variability in bipolar mania and schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 44, 168–176 (2010).

Bandelow, B. et al. Biological markers for anxiety disorders, OCD and PTSD: a consensus statement. Part II: neurochemistry, neurophysiology and neurocognition. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 18, 162–214 (2017).

Villar de Araujo, T. et al. Autism spectrum disorders in adults and the autonomic nervous system: Heart rate variability markers in the diagnostic procedure. J. Psychiatr. Res. 164, 235–242 (2023).

Cheng, Y.-C., Su, M.-I., Liu, C.-W., Huang, Y.-C. & Huang, W.-L. Heart rate variability in patients with anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 76, 292–302 (2022).

Wilson, S. T. et al. Heart rate variability and suicidal behavior. Psychiatry Res. 240, 241–247 (2016).

Rüesch, A. et al. A recent suicide attempt and the heartbeat: electrophysiological findings from a trans-diagnostic cohort of patients and healthy controls. J. Psychiatr. Res. 157, 257–263 (2023).

Thorell, L. H. et al. Electrodermal hyporeactivity as a trait marker for suicidal propensity in uni- and bipolar depression. J. Psychiatr. Res. 47, 1925–1931 (2013).

UK Biobank (2007) UK Biobank: protocol for a large-scale prospective epidemiological resource. https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/media/c4yefr4t/210527-uk-biobank-communications-guidelines.pdf (accessed June 2024).

Kessler, R. C. & Üstün, T. B. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int. J. Methods Psychsol. Res. 13, 93–121 (2004).

Levis, B., Benedetti, A. & Thombs, B. D. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ l1476 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1476 (2019)

Shaffer, F. & Ginsberg, J. P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front Public Health 5, (2017).

Vila, X. A., Lado, M. J. & Cuesta-Morales, P. Evidence-based recommendations for designing heart rate variability studies. J. Med. Syst. 43, 311 (2019).

Kang, G. E. et al. Objective measurement of sleep, heart rate, heart rate variability, and physical activity in suicidality: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 273, 318–327 (2020).

Bellato, A. et al. Autonomic dysregulation and self-injurious thoughts and behaviours in children and young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JCPP Adv. 3, e12148 (2023).

Hartmann, R., Schmidt, F. M., Sander, C. & Hegerl, U. Heart rate variability as indicator of clinical state in depression. Front. Psychiatry 9, 735 (2019).

Perna, G. et al. Heart rate variability: Can it serve as a marker of mental health resilience?. J. Affect. Disord. 263, 754–761 (2020).

McEwen, B. S. Stress, adaptation, and disease: allostasis and allostatic load. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 840, 33–44 (1998).

Karatsoreos, I. N. & McEwen, B. S. Psychobiological allostasis: resistance, resilience and vulnerability. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 576–584 (2011).

Godoy, L. D., Rossignoli, M. T., Delfino-Pereira, P., Garcia-Cairasco, N. & De Lima Umeoka, E. H. A comprehensive overview on stress neurobiology: basic concepts and clinical implications. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 12, 127 (2018).

Goldstein, D. S. Stress-induced activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Baillière’s. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1, 253–278 (1987).

Weissman, D. G. & Mendes, W. B. Correlation of sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activity during rest and acute stress tasks. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 162, 60–68 (2021).

Kim, H.-G., Cheon, E.-J., Bai, D.-S., Lee, Y. H. & Koo, B.-H. Stress and heart rate variability: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. Psychiatry Investig. 15, 235–245 (2018).

An, E. et al. Heart Rate Variability as an Index of Resilience. Mil. Med. 185, 363–369 (2020).

Ritz, T. Putting back respiration into respiratory sinus arrhythmia or high-frequency heart rate variability: Implications for interpretation, respiratory rhythmicity, and health. Biol. Psychol. 185, 108728 (2024).

Krkovic, K., Clamor, A. & Lincoln, T. M. Emotion regulation as a predictor of the endocrine, autonomic, affective, and symptomatic stress response and recovery. Psychoneuroendocrinology 94, 112–120 (2018).

Carnevali, L., Thayer, J. F., Brosschot, J. F. & Ottaviani, C. Heart rate variability mediates the link between rumination and depressive symptoms: a longitudinal study. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 131, 131–138 (2018).

Laborde, S., Mosley, E. & Thayer, J. F. Heart rate variability and cardiac vagal tone in psychophysiological research—recommendations for experiment planning, data analysis, and data reporting. Front. Psychol. 08, 213 (2017).

Thayer, J. F. & Lane, R. D. A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. J. Affect. Disord. 61, 201–216 (2000).

Friston, K. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 127–138 (2010).

Barrett, L. F. & Simmons, W. K. Interoceptive predictions in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 419–429 (2015).

Wackerhagen, C. et al. Influence of familial risk for depression on cortico-limbic connectivity during implicit emotional processing. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 1729–1738 (2017).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E. & Lyubomirsky, S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3, 400–424 (2008).

Moretta, T. & Messerotti Benvenuti, S. Early indicators of vulnerability to depression: the role of rumination and heart rate variability. J. Affect. Disord. 312, 217–224 (2022).

Parr, T., Rees, G. & Friston, K. J. Computational neuropsychology and Bayesian inference. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 12, 61 (2018).

Dantzer, R., O’Connor, J. C., Freund, G. G., Johnson, R. W. & Kelley, K. W. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 46–56 (2008).

Raison, C. L. & Miller, A. H. Malaise, melancholia and madness: the evolutionary legacy of an inflammatory bias. Brain Behav. Immun. 31, 1–8 (2013).

Dantzer, R., Heijnen, C. J., Kavelaars, A., Laye, S. & Capuron, L. The neuroimmune basis of fatigue. Trends Neurosci. 37, 39–46 (2014).

Harrison, N. A. et al. Neural origins of human sickness in interoceptive responses to inflammation. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 415–422 (2009).

Hegerl, U. & Hensch, T. The vigilance regulation model of affective disorders and ADHD. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 44, 45–57 (2014).

Olbrich, S. et al. EEG vigilance regulation patterns and their discriminative power to separate patients with major depression from healthy controls. Neuropsychobiology 65, 188–194 (2012).

Rotenberg, V. S. et al. REM sleep latency and wakefulness in the first sleep cycle as markers of major depression. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 26, 1211–1215 (2002).

Shaffer, F., McCraty, R. & Zerr, C. L. A healthy heart is not a metronome: an integrative review of the heart’s anatomy and heart rate variability. Front. Psychol. 5, 1040 (2014).

Schumann, A., Andrack, C. & Bär, K.-J. Differences of sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation in major depression. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 79, 324–331 (2017).

Sarlon, J., Staniloiu, A. & Kordon, A. Heart rate variability changes in patients with major depressive disorder: related to confounding factors, not to symptom severity?. Front. Neurosci. 15, 675624 (2021).

Arnsten, A. F. T. Stress weakens prefrontal networks: molecular insults to higher cognition. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1376–1385 (2015).

Tzeng, Y. C., Larsen, P. D. & Galletly, D. C. Mechanism of cardioventilatory coupling: insights from cardiac pacing, vagotomy, and sinoaortic denervation in the anesthetized rat. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292, H1967–H1977 (2007).

Jänig, W. The Integrative Action of the Autonomic Nervous System: Neurobiology of Homeostasis (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Sgoifo, A., Carnevali, L., Pico Alfonso, M. D. L. A. & Amore, M. Autonomic dysfunction and heart rate variability in depression. Stress 18, 343–352 (2015).

Ettore, E. et al. Digital phenotyping for differential diagnosis of major depressive episode: narrative review. JMIR Ment. Health 10, e37225 (2023).

Pizzoli, S. F. M. et al. A meta-analysis on heart rate variability biofeedback and depressive symptoms. Sci. Rep. 11, 6650 (2021).

Chaitanya, S., Datta, A., Bhandari, B. & Sharma, V. K. Effect of resonance breathing on heart rate variability and cognitive functions in young adults: a randomised controlled study. Cureus https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.22187 (2022).

De Souza, P. M. et al. Long-term benefits of heart rate variability biofeedback training in older adults with different levels of social interaction: a pilot study. Sci. Rep. 12, 18795 (2022).

Goessl, V. C., Curtiss, J. E. & Hofmann, S. G. The effect of heart rate variability biofeedback training on stress and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 47, 2578–2586 (2017).

Van Der Zwan, J. E., De Vente, W., Huizink, A. C., Bögels, S. M. & De Bruin, E. I. Physical activity, mindfulness meditation, or heart rate variability biofeedback for stress reduction: a randomized controlled trial. Appl Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 40, 257–268 (2015).

Giurgi-Oncu, C. et al. Evolution of heart rate variability and heart rate turbulence in patients with depressive illness treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Medicina 56, 590 (2020).

Ip, C.-T. et al. EEG-vigilance regulation is associated with and predicts ketamine response in major depressive disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 14, 64 (2024).

Meyer, T. et al. Predictive value of heart rate in treatment of major depression with ketamine in two controlled trials. Clin. Neurophysiol. 132, 1339–1346 (2021).

Zanos, P. & Gould, T. D. Mechanisms of ketamine action as an antidepressant. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 801–811 (2018).

Lombardi, F., Huikuri, H., Schmidt, G. & Malik, M. Short-term heart rate variability: easy to measure, difficult to interpret. Heart Rhythm 15, 1559–1560 (2018).

Young, F. L. S. & Leicht, A. S. Short-term stability of resting heart rate variability: influence of position and gender. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 36, 210–218 (2011).

Spina, G. D., Gonze, B. B., Barbosa, A. C. B., Sperandio, E. F. & Dourado, V. Z. Presence of age- and sex-related differences in heart rate variability despite the maintenance of a suitable level of accelerometer-based physical activity. Braz. J. Med Biol. Res. 52, e8088 (2019).

Ma, X. et al. The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults. Front. Psychol. 8, 874 (2017).

Van Diest, I. et al. Inhalation/exhalation ratio modulates the effect of slow breathing on heart rate variability and relaxation. Appl Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 39, 171–180 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF Grant 205913). This research has been conducted using data from UK Biobank, a major biomedical database. Thanks to PD Dr. med. Georgios Schoretsanitis, who made us aware of the database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the study and reviewed the manuscript. M.M. and V.A-G. did the statistical analysis. S.W. did the main writing. S.O. designed the hypothesis. G.K., S.O. and S.W. did the recherche. S.W. and M.M. designed the figures and tables, E.S. provided resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weber, S., Müller, M., Kronenberg, G. et al. Electrocardiography-derived autonomic profiles in depression and suicide risk with insights from the UK Biobank. npj Mental Health Res 4, 17 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-025-00130-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-025-00130-0