Abstract

Global lake and reservoir water surfaces were recently estimated to contribute ~10% of global methane (CH4) emissions. The sensitivity of these emissions to climate and environmental change is a growing concern. Here we present data-driven, globally gridded modelling of future open-water CH4 fluxes under different scenarios. We included multiple potential predictor variables and available peer-reviewed flux data focusing on in situ-verified relationships. The results indicate total lake and reservoir CH4 emissions increases of 24–91% under the IPCC Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) climate change scenarios SSP1-2.6 to SSP5-8.5 by 2080–2099. Effects of changed temperature and seasonality dominated these increases. Area and nutrient load changes also contributed substantially to reservoir emissions. Large absolute changes were predicted at all latitudes. The results demonstrate the urgency in minimizing climate change to avoid substantially increased future inland water CH4 emissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Emissions of methane (CH4) have increased from 1750 to 2019 contributing a total radiative forcing (direct and indirect) of 0.95 W m−2 (refs. 1,2). This is 22% of the total radiative forcing of all greenhouse gases (GHGs) and 30.5% of the total radiative forcing from carbon dioxide (CO2), CH4 and nitrous oxide (N2O)1,2. Overall, since 1750, CH4 levels have increased by a factor of 2.6 (compared to 1.5 for CO2 and 1.2 and N2O)2. Whereas atmospheric increases of CO2 and N2O have followed a regular trajectory aligned with human activity and fossil fuel use, the increase of atmospheric CH4 has much larger interannual- and decadal-variability for yet unknown reasons3,4.

CH4 has a 20-year global warming potential of 81 ± 26 compared to CO2 on a mass basis, but a relatively short atmospheric lifetime (~11 years) (ref. 2). Accordingly, increases or decreases in CH4 emissions can rapidly and substantially enhance or dampen global warming, making CH4 emissions regulation important for the future climate. Possible climate change effects on CH4 sources are therefore a concern, and it was recently suggested that the climate sensitivity of CH4 emissions is much greater than previously estimated5. However, the quantitative magnitudes and drivers of many of these effects remain uncertain, making it challenging to understand past atmospheric CH4 concentration variability and accurately forecast CH4 emissions into the future.

Open-water surfaces of freshwater lakes and reservoirs collectively represent one of the largest contemporary CH4 sources. On a global scale, the water surfaces of lakes and reservoirs have recently been estimated to emit 24–150 and 10–20 Tg CH4 yr−1, respectively6,7,8,9,10,11,12. A main CH4 source is microbial degradation of organic matter in anoxic sediments13. When CH4 production rates exceed dissolution, bubbles are formed which can be released and rapidly rise through the water column to the atmosphere—an emissions pathway referred to as ebullition, which often dominates total emissions from open-water environments7,8. The CH4 getting dissolved in the water follows a slower route towards the atmosphere via advection or turbulent diffusion. A large proportion of this dissolved CH4 is consumed by microbial oxidation when reaching portions of the water column where dissolved oxygen (O2) or other suitable electron acceptors are available. The remaining dissolved CH4 eventually passing the boundary layer at the water–atmosphere interface is emitted by diffusive flux. Methane being formed in oxic surface waters can also add to the diffusive flux14. Notably, ebullition and diffusive flux are regulated in different ways as described in detail elsewhere13,15.

Methane emissions from lake and reservoir water surfaces can be influenced by environmental change in multiple ways. Microbial CH4 production seems more sensitive to temperature than many other metabolic processes such as photosynthesis, oxic respiration and CH4 oxidation and increases exponentially with temperature across lake and reservoir types at all latitudes16,17. Similar exponential temperature responses have been observed for ebullition18 and for total CH4 emissions17,19. In addition, the length of the ice-free period influences high-latitude lake CH4 emissions20,21,22,23. Increased availability of labile substrates for methanogenesis, by, for example, biological productivity or access to organic matter released from melting permafrost soils, also enhance CH4 production24,25,26. Accordingly, changes in lake and reservoir inputs of catchment organic matter or nutrients can affect CH4 production rates and emissions. In addition, possible changes in water surface area will be important for overall emissions.

Constraining contemporary global lake and reservoir CH4 emissions and extrapolating contemporary assessments to future climate scenarios has been challenging due to limitations in the amount and comparability of flux observations and to the complexity in the regulation of all relevant processes. A data-driven extrapolation approach was recently published to improve contemporary lake and reservoir flux estimates7,8. This approach was further developed in this study to predict global lake and reservoir CH4 emissions over 20-year periods until the end of the century (2080–2099). It is based on a gridded lake and reservoir area distribution and considers temperature effects on CH4 fluxes under established climate change scenarios, along with the effects of ice-free period length, diel flux variability, water body types and ecoclimatic regions. Different flux types, including ebullition, diffusive flux and enhanced diffusive flux in lakes following ice melt and seasonal water column turnover when deep CH4-enriched water reaches the surface, were also included. All information used is linked to in situ flux observations integrating the complex interactions of relevant ecosystem processes. Flux data from 767 systems were used. The assessment of future fluxes also considers effects of estimated regional changes in water surface area and in phosphorous levels to account for nutrient load and associated changes in primary productivity.

Already-large-lake and reservoir CH4 emissions may double

The Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) climate change scenarios SSP1-2.6 and SSP2-4.5 translates to effective societal transformation and estimated global annual mean temperature increases of 1.5 to 2.6 °C by year 2080–2099 (Extended Data Fig. 1)27. Under these scenarios, the combined lake and reservoir water surface CH4 emissions were estimated to increase 24–52% in total (from 59 to 73–90 Tg CH4 yr−1; Table 1 and Fig. 1). The SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5 climate scenarios represent societal inability to mitigate GHG emissions and a resulting annual global mean temperature increase of 3.8–4.7 °C by the end of the century. Under these warmer scenarios, combined lake and reservoir emissions increased 80–91% to 107–112 Tg CH4 yr−1 (Table 1 and Fig. 1). A change from 59 to 113 Tg CH4 yr−1, that is, 53 Tg CH4 yr−1, represents almost a doubling of the lake and reservoir emissions and an ~10% increase of the total global contemporary CH4 emissions3. An increase of 53 Tg CH4 yr−1 can also be viewed in the context of the total estimated contemporary emissions from landfills and waste, coal mining or oil and fossil gas emissions (55–71, 23–40 and 60–97 Tg CH4 yr−1, respectively).

a,b, Modelled lake (a) and reservoir (b) CH4 emissions over time under different climate change scenarios (SSP1, SSP2, SSP3 and SSP5). Lines were derived from the model considering primarily the direct temperature response and ice-free period length. The dots represent the expected emissions by the end of the century combining this model and all other change factors in Table 1. Uncertainty estimates and analysis are available in Fig. 5 and Methods. Note that the y-axis scales do not start at zero.

Reservoir emissions increased proportionally more than lake emissions (124% versus 81% increase) and contributed 26% of the total combined absolute emissions increase in the SSP5-8.5 climate scenario (Table 1). These patterns reflect the fact that lakes and reservoirs differ in their global areas and geospatial distribution and therefore also in predicted temperature, area and nutrient load changes (Fig. 2, Extended Data Fig. 2 and Methods).

a–d, Present-day baseline and predicted future lake and reservoir emissions (a,b) and percent flux changes (c,d) by latitude for different SSP climate change scenarios. Dashed grey lines represent approximate latitude transitions between the boreal–arctic, temperate and tropical–subtropical ecoclimatic regions. Text provides details.

Temperature-related climate effects were most important for the predicted future fluxes (Table 1). Changes in water surface areas and nutrient load modulated the predicted fluxes for lakes but jointly had a larger effect on reservoir emissions. For example, the planned increase in reservoir area had similar effects as the temperature increase in the SSP1-2.6 and SSP2-4.5 scenarios. A lower estimated nutrient load in the SSP5-8.5 scenario compared to SSP3-7.028, made total predicted emissions under these two scenarios more similar than among other climate scenarios (Table 1).

Effects among different ecoclimatic regions

The longer ice-free seasons in the future accounted for 9–33% and 14–17% of the temperature effect in the boreal–arctic lake and reservoir CH4 emissions, respectively, whereas direct temperature-sensitivity effects dominated the climate-induced flux increase (Extended Data Table 1). Shorter durations of ice cover reduce the time for CH4 accumulation in bottom waters during winter at high latitudes. Accordingly, emissions related to ice out and spring water column turnover are predicted to decrease (Extended Data Table 2). Correspondingly, the warmer summers and longer ice-free periods at northern temperate to boreal–arctic latitudes influenced the seasonal pattern of the total emissions (Table 1 and Fig. 3)7,8.

a–d, The 2000–2019 baseline emissions versus predicted emissions under the SSP5-8.5 climate scenario at 2080–2099 (a,c) and the difference between the two (b,d) in the northern and southern hemispheres, respectively. The differences between all used SSP scenarios and the baseline are shown in panel b (northern hemisphere) and d (southern hemisphere). The irregular patterns in the spring (March–June) and fall/winter (October–December), particularly in the northern hemisphere (a,b) are due to changes in ice-free season length and timing of emissions upon ice melt and seasonal water column turnover. The smoother portions of the predicted increases between these times primarily reflects temperature-related increases.

The predicted relative increase in emissions due to temperature-related effects was greater at high latitudes for both lakes and reservoirs in all climate scenarios (Fig. 2, Fig. 4 and Table 1). This is expected because of the combined effect of increasing temperatures, prolonged ice-free seasons length (Extended Data Table 2) and the large lake surface area in the temperate to arctic regions (Extended Data Fig. 2). Yet, the tropical and subtropical regions were found to contribute large absolute flux changes in spite of smaller water surface area and lower predicted mean temperature increase (Figs. 2 and 4, Table 1, Extended Data Figs. 1). This illustrates the great importance of high year-round emissions and of the exponential response to increasing temperatures, yielding greater absolute effects per degree of change at higher starting temperatures16,29. Accordingly, analyses of relative and absolute changes can yield contrasting patterns, and climate effects in areas with limited relative temperature changes can still be large in absolute terms. Therefore, consideration of climate effects on lake and reservoir CH4 emissions at all latitudes is important.

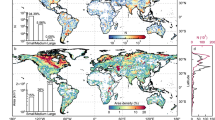

a–d, Geospatial distribution of contemporary (2000–2019) lake and reservoir emissions per m2 by grid cell (a) and the percent change in emissions by 2080–2099 under the SSP1-2.6 (b), SSP2-4.5 (c), SSP3-7.0 (c) and SSP5-8.5 (d) climate scenarios using the 20-model ensemble described in Extended Data Table 5.

Discussion

Emissions uncertainty

This section focuses on uncertainty of the results in relation to the influencing environmental factors and limitations to what environmental change could be considered at this stage. Fundamental uncertainty and limitations associated with the design of our prediction approach are discussed further in the Methods.

The total propagated uncertainty for all factors considered and linked to individual observations (ε; Methods) corresponded to a coefficient of variation (CV) of 60.7 and 48.7% for lakes and reservoirs, respectively (Fig. 5a). Among the influencing factors considered, the greatest uncertainty was associated with the temperature sensitivity, first assessed from observations in a range of individual systems (Extended Data Table 3). The exponential nature of this relationship makes the choice of temperature sensitivity factor, θ, highly important for the results. To constrain this uncertainty, we fitted regional θ to multi-system monthly mean fluxes observed at temperate to arctic latitudes. These regional multi-system calibrations resulted in close correspondence between predicted versus observed fluxes and substantially reduced the overall uncertainty (to a CV of 20%; Fig. 5b and Methods), while staying consistent with literature θ estimates from individual systems. This validation of single system temperature sensitivity to large amounts of in situ observations across regions represented an important novel way to constrain the prediction uncertainty. The use of a low-end θ value for tropical–subtropical areas (close to the minimum θ observed; Methods) means that low-latitude temperature sensitivity could be underestimated and makes the low-latitude results conservative.

a, Classical propagations of ε expressed as coefficient of variation (CV) of all considered factors (Methods). Such uncertainty propagation reflects uncertainty of the original observations but do not fully account for the integrated total uncertainty, which is often lower as some of the real inherent single-observation variability cancel out when many observations are integrated. Hence, the total uncertainty in a represents an upper bound and a likely overestimate, but this approach is useful for comparing the relative uncertainty among considered environmental factors. Note that the inherent uncertainty of some factors has limited influence on relative change with climate scenarios (text). The notes in the panel refer to: *High inherent variability; episodic extreme fluxes are key for the total flux. **Considered outside model by change factors (Table 1 and Extended Data Figs. 3 and 4). b, The uncertainty could be constrained by optimizing modelled θ for boreal–arctic and temperate lake ebullition (solid line) to monthly averaged in situ observed ebullition (dashed lines). After this optimization, θ is informed by the numerous distributed in situ observations and not only θ studies in a few systems (Extended Data Table 3). Importantly, this generated considerably lower integrated uncertainty (CV ~20%) while also being consistent with the range of previous single system θ observations (Extended Data Table 3; Methods). Hence, while a is primarily intended to provide an upper uncertainty bound and a relative comparison among considered environmental predictors, our best use of available information yields a lower overall uncertainty (CV ~20% for temperate and boreal-to-arctic lakes) (b). incl., including; accum, accumulation; temp., temperature; ebul. emiss., ebullitive emission; RMSE, root mean square error. ‘Soil temp. threshold’ refers to uncertainty in the definitions of the ecoclimatic regions (Methods).

The variability in the original flux data contributed the second largest uncertainty (Fig. 5a). Because episodic, semi-random, and positive outlier fluxes (ebullition and seasonal outgassing) often dominate cumulative yearly CH4 emissions from water surfaces, a large inherent (aleatoric) variability must always be expected. Hence, a low apparent measurement variability can indicate incomplete characterization of the system, while high variability among individual observations is logical if all flux types are represented. Importantly, this type of inherent variability reflects the processes behind the fluxes and is more important for the uncertainty of absolute local flux quantification than for the mean relative regional flux change.

The effects of changes in nutrient load generated the third-largest uncertainty (Fig. 5). The impact of such nutrient changes on the CH4 fluxes was larger for reservoirs than lakes due to proportionally larger high-emitting reservoir area in warm regions projected for greatest nutrient load increases. However, the flux uncertainty linked to nutrient load uncertainty was comparatively small and therefore not decisive for the results (Fig. 5a). This also applied for the uncertainty contributions from the remaining factors considered.

Some aspects of future lake and reservoir CH4 emissions could not be reliably considered at this stage because of in situ data limitations. One such aspect is the possibility of increased establishment of farm ponds and freshwater aquaculture ponds that have been highlighted as hotspots for CH4 emissions30,31. It is likely that a future increase in such pond areas would trigger greater emissions. At present, CH4 emissions from agricultural ponds in the United States and Australia, and from aquaculture in China, have been estimated to be ~0.17 and 1.6 Tg CH4 yr−1, respectively31,32, indicating a combined potential global emission contribution on the order of 10 Tg CH4 yr−1. However, the lack of accurate global area estimates for such ponds prevent precise flux estimations and thereby also reliable predictions.

In addition, reservoir turbine degassing is important for total reservoir emissions, but is more related with reservoir design than environmental change and was therefore not included in our estimate. Reservoir turbine degassing has been estimated to increase by 53% from 2010 to 204033, that is, in the order of 5 Tg CH4 yr−1, which is a small share of the total estimated increase but substantial from the reservoir perspective.

Further, over long timescales, indirect effects may lead to changes in the distribution of the ecoclimatic regions. One example would be the replacement of tundra landscapes by the northward migration of the coniferous taiga forests. This would lead to more lakes being situated in warmer regions and receive more organic matter from the catchments, which would probably lead to increased lake CH4 emissions34. Over long timescales, transitions from lakes to wetlands with emergent vegetation can also increase CH4 emissions via macrophyte gas exchange35,36,37. Such long-term effects are beyond the scope of this study, but in the foreseeable scenarios, the most likely outcome seems to be increasing CH4 emissions in the humid biomes. Hence, future studies on effects of landscape development are important to better understand long-term CH4 flux changes.

Directional versus quantitative predictions

This is a global geospatial study, integrating available relevant in situ observed emissions by different flux types with temperature sensitivity, remote-sensing observations of ice-cover phenology, diel patterns, fluxes associated with water column storage and turnover in interaction with methane oxidation, differences among ecoclimatic regions, updated information of the area of the smallest lakes and with established quantitative projections of climate, lake area and nutrient regimes over time, to assess future CH4 emissions from both lake and reservoir water surfaces (Extended Data Table 4 and Extended Data Figs. 3 and 4). To our knowledge, all these aspects have not been integrated previously to predict future CH4 emissions from both lakes and reservoirs. Similarly, distinguishing the relative contribution of different influencing factors (predictors) have seemingly been rare. Comparisons with past work are therefore limited to subsets of the regions and lake types, lake size categories, flux types or a few of the flux predictor variables as explained for each study below. A recent regional modelling study of lake CH4 emissions upon permafrost thaw in the taiga plains, based on studies of 20 lakes, indicated increases of 31–121% from the Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) climate scenarios RCP2.6 and 4.5, respectively34. There are also estimates of a future global lake CH4 production increase of 13–40% (ref. 38) and a 51% increase in ebullition from a warming of 4 °C (ref. 18). Diffusive fluxes of Finnish lakes have been estimated to increase by 26–59% until the 2090s due to a prolonged ice-free period22. A 1-D process-based lake model originally designed for arctic lakes, using data from 60 lakes, indicated lake CH4 emissions increases of 58–86% under the RCP8.5 scenario, albeit suggesting much lower absolute fluxes12. Studies of three subarctic lakes have led to an estimated increase in mean annual ebullition by 38% during the half-century period from 2009–2013 until 2040–207921. Cumulative reservoir open-water CH4 emissions have been estimated to increase by 8 and 30% for diffusive flux and ebullition, respectively, from 2010 to 204033. Despite the considerable differences in approaches, extent and environmental driver features considered, all studies agree on the direction, that is, that emissions of CH4 from lakes and reservoirs will probably increase considerably in the future. Our result, that the temperature effects are dominating (Table 1) explains why the direction of the future development is consistent. The disagreements in magnitudes are expected given the differences in scope and data support for the different studies. For the future, a greater consistency among studies in considered system types, flux types, spatio-temporal extent and environmental predictor variables would be beneficial. This would improve our underlying understanding of lake and reservoir CH4 emissions and allow systematic model intercomparisons, which are valuable for evaluating and constraining predictive models. In addition, it seems important that future models include not only climate and temperature effects but also effects from other potential predictors. For example, as the projections of future surface water area and nutrient loads will progress, these factors deserve more attention. They are complex to predict at high resolution and may develop in less predictable ways over space and time because of dependency on technological development and policy. For example, both lake and reservoir fluxes may be influenced by changes in agricultural practices which influence nutrient load and water use for irrigation. Hydropower reservoir area and distribution are influenced by energy policies and the cost of alternative energy sources.

Outlook and implications for the global CH4 budget

Future climate effects on CH4 emissions have been discussed conceptually but have rarely been quantified globally and are thereby poorly constrained39,40. Our results of a 24–91% or 14–53 Tg CH4 yr−1 increase from present day to 2080–2099 for lakes and reservoirs depending on the climate scenario (Table 1), represent an integration of available process knowledge and in situ observations to assess possible future emissions on a global scale. For comparison with global wetlands, a data-driven integration of numerous studies estimated a climate-induced increase of wetland CH4 emissions of 20–60% or 14–90 Tg CH4 yr−1 (RCP2.6 to RCP8.5 scenarios)41. We note consistent predictions for lakes, reservoirs (present study) and wetlands41 in having highest relative emissions increases in boreal to arctic latitudes but high absolute emissions increases also at lower latitudes. This highlights the importance of climate effects at all latitudes.

Clearly, substantial climate effects are to be expected in natural CH4-emitting environments. In the business-as-usual ‘fossil-fuelled’ scenario (SSP5-8.5), the combined climate effects on lakes and reservoirs (this work) and wetlands41, together constituting ~10% of the continental area7,8,42, are likely to increase total global CH4 emissions by > 25% by the end of the century. Such climate effects on previously natural emissions indicate that future climate change may become more dramatic and challenging for societies than expected.

The substantial differences between the climate change scenarios illustrate that the climate effect on CH4 emissions from lakes and reservoirs will be highly dependent on the anthropogenic GHG emissions. Hence, urgent mitigation of anthropogenic GHG emissions is not only vital per se but also has a critical extra benefit by mitigating future positive feedbacks linked to lake and reservoir CH4 emissions.

Methods

We developed a data-driven, globally gridded approach to estimate climate-driven changes in lake and reservoir CH4 emissions from temperature change and change in the ice-free season length under four climate scenarios for the time periods of 2000–2019 (present), 2020–2039, 2040–2059, 2060–2079 and 2080–2099 (end of the century). This model considered the major open-water CH4 flux types and multiple factors affecting them (Extended Data Table 4). The results from the model were combined with estimated effects on fluxes from projected changes in water surface area and nutrient levels of lakes and reservoirs (phosphorous used as proxy for biological productivity). General workflows are provided in Extended Data Figs. 3 and 4.

Data-driven modelling for flux predictions

A previous static model for estimating contemporary CH4 emissions7,8 was further developed and extended to enable predictive capacity. The previous model was restructured to add a time dimension and allowing temporal changes in e.g. temperatures and ice-free period length under future climate scenarios (Shared Socioeconomic Pathways SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.543). Climate model temperature inputs for each grid and time periods were consistently used—including the present time period (2000–2019; used as baseline). The temperature-response calculations were extended to cover both seasons and years. Climate effects on projected deep-water temperatures38 were incorporated. Additional aspects of uncertainty associated with predictions were added. The input CH4 flux data were extended to include more recent in situ CH4 flux observations. The model was driven by in situ observed relationships between temperature or ice-free water area over time and direct in situ flux measurements, thereby integrating net influences of the numerous complex physical, chemical and biological processes affecting CH4 production, oxidation and transport, without a need of knowing process-specific parameterization. Overall, we aimed for (1) maximum transparency and simplicity, along with minimum sensitivity to (2) limitations in the understanding of underlying processes and their interactions and (3) to challenges related to access to, or uncertainty of, accessory driver data. This strategy was motivated by the scarcity of local in situ data to validate all processes involved at the spatio-temporal scale needed and by the lack of time series for lake and reservoir CH4 emissions, which prevented traditional validation of predictive models via hindcasting. Importantly, the selected approach reduces the risk of unpredictable model behaviour based on unexpected nonlinear process interactions (further discussed below). Key parts of this model were derived from in situ observations and the general assumption that these observations collectively are representative of the ecoclimatic region and the respective lake types. An overview of all the factors being considered is available in Extended Data Table 4. The different parts of the model are described below.

CH4 flux data

Starting from available databases, the original sources providing in situ observations of lake and reservoir CH4 fluxes were revisited to confirm correctness of values and collect more extensive original accessory information on measurement methods, measurement times (month and time of day) and durations, water or air temperatures during each measurement, coordinates, flux type and ecoclimatic region or lake type6,7,8,10,23,44. Some new data from data-scarce regions were added specifically for this study (for example, data from Africa45). Altogether data from 606 individual lakes and 161 reservoirs were used. As a part of data quality control, only data from peer-reviewed publications were accepted.

Ecoclimatic regions, lake types and water surface area

The spatial definitions of tropical–subtropical, temperate and boreal–arctic regions were derived from annually averaged soil temperature from the Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2)46 as described in detail previously7,8,20. Within the boreal–arctic region, lakes were divided into several classes based on datasets of distributions and types of permafrost, soil organic carbon content and ground-ice coverage (thermokarst, glacial/postglacial, peat pond, organic and other boreal)20. Geospatial area distributions of lakes and reservoirs were derived from Messager et al. (2016)47 for water body area > 0.1 km2. Smaller water bodies ( < 0.1 km2) were estimated from visually verified BWALD boreal–arctic small lake data48 as follows: BWALD data were used to derive ratios of small ( < 0.1 km2) to mid-size (0.1–10 km2) lake areas for peatland lakes (ratio of 0.86), yedoma lakes (0.82) and glacial lakes (0.24). The mean of peatland and yedoma lake ratios (0.84) was used to estimate small lake areas from mid-size lake area for our thermokarst, peat pond and organic lake categories. The glacial lake ratio was used for our glacial/postglacial lake category, and the grand mean ratio (0.54) was used to estimate small lake area in temperate and tropical–subtropical regions. The inland water areas were distributed in grids of 0.25° × 0.25°.

The water area data products used47,48,49 are remote-sensing-verified and for BWALD boreal–arctic regions also visually verified versus Google Earth satellite imagery48. The total lake area used was 3,099 × 103 km2 and the area of lakes < 0.1 km2 had a global coverage of 405 × 103 km2. Other area estimates of lakes < 0.1 km2 are up to almost 3–4 times greater (1,300 × 103 km2) (ref. 9). This highlights the importance of constraining the water area before it can be adequately considered in spatially explicit predictions. This is a reason why water area change effects in this study were considered as a proportional change factor outside the gridded model. Small and shallow water bodies are characterized by proportionally greater emissions than larger systems18,19,50,51 and the area estimate of the smallest water bodies can be important for absolute flux values (although less so for relative flux change). The total contemporary reservoir area used was 297 × 103 km2 (ref. 7), which is slightly smaller than recent estimates from 2010 to 2020 of 315–348 × 103 km2 (ref. 33).

Temperature predictions from climate change scenarios

For each grid cell, mean monthly near-surface (2 metres above ground level) air temperatures for the periods of 2000–2019, 2020–2039, 2040–2059, 2060–2079 and 2080–2099 under the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Report 627 climate scenarios SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5 were derived from an aggregated ensemble comprising 20 climate models (Extended Data Table 5). Monthly mean temperatures for the time periods and all SSP scenarios used in this study were extracted from the ensemble model and used as CH4 flux model input. Monthly near-surface air temperature data from each model were linearly interpolated from their native spatial resolution to 0.25° × 0.25° before producing the multi-model monthly mean data. Surface water and air temperatures are typically strongly correlated over 24 h to monthly periods52,53,54. Model results from monthly grid temperatures of the period of 2000–2019 were verified towards results from corresponding observation-constrained temperature predictions from the Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2)46 and resulting grid-specific CH4 fluxes deviated < ± 2.5%. This indicated a general consistency among modelled and observed temperatures in terms of effects on CH4 fluxes.

Ice-cover phenology

Spatio-temporal daily lake and reservoir freeze/thaw times for the contemporary time period were derived using satellite microwave observations of ice-cover phenology7,8,20. To predict future lake and reservoir ice-cover periods due to changing temperature, a second-order polynomial fit between present-day ice-free season length and 2-metre MERRA-2 air temperature was derived (\(f\left(x\right)=a{x}^{2}+{bx}+c\); where \(x\) is the 2-metre air temperatures; \(a=\) 0.0522, \({b}=\) −21.38, \(c=\) 2,109; R2 = 0.81). This fit was then applied using future SSP climate scenario 2-metre air temperatures to calculate the duration of ice cover and ice-free periods in the future for each grid and climate scenario.

Ebullition and diffusive flux

Open-water CH4 flux data not already measured over full 24-h cycles were corrected for diel variability to consistently represent 24-h fluxes as described in detail previously55. Field-observation-derived temperature–CH4-flux relationships from the literature, combined with information about the fluxes and temperatures during months of measurements, were used to estimate ice-free monthly fluxes at each measurement location. The emissions–temperature relationship was based on data listed in Extended Data Table 3. Briefly, the generic equation

where \({E}_{{{T}}}\) represents the emissions rate (mg CH4 m−2 d−1) at the surface temperature T (°C), \({E}_{20}\) is the emissions rate at 20 °C and θ represents the temperature sensitivity factor. For predictions into the future, the temperature sensitivity was applied only to ebullition due to the absence of a clear temperature relationship for diffusive flux in the most comprehensive intercontinental study18, which is consistent with the complex interactions among many processes regulating diffusive flux13. Ebullition on the other hand seems more directly linked to sediment CH4 production, and there is strong empirical support of its temperature sensitivity across the world17,18,19,21,56,57,58,59,60,61,62. A few datasets indicate that the temperature response seems general and valid both within and among years and among locations up to 45 °C (refs. 17,18,19,21,62) (Extended Data Table 3). Importantly, because the direct temperature response only regards ebullition in our predictions, the future diffusive flux is therefore only affected by climate change in the model via the length of the ice-free season. If diffusive flux is also influenced in a direct way by increased future temperatures, which some studies indicate19,63, our results are conservative and expected climate effects may be even greater.

By applying equation (1), the relative emission rates for each month (the proportion of yearly flux estimated to occur each ice-free month) were derived based on the monthly mean temperatures for each grid7,8, in turn allowing estimation of each monthly flux from available measurements. The temperature–flux relationship was used to generate extrapolated mean monthly fluxes scaled to the grid-specific temperatures as exemplified by equation (2) and equation (3) for cases where annually averaged or single month daily flux rates, respectively, were available.

EN represents the calculated monthly averaged daily emissions rate (mg CH4 m−2 d−1) for each month (N is the month number; January to December = 1 to 12) at the surface temperature TN (°C) for each month, E20 is the emissions rate at 20 °C, θ represents the temperature sensitivity factor and EY is the annual-averaged daily emissions rate and Nmax = 12. EM is the known monthly emissions rate and TM is the air temperature for the month of the known emissions rate. These equations are extended for transparency and because E20 cancels out, only EY or EM, TN, TM and θ are needed as input variables.

For rescaling the temperature effect on fluxes to each future time period, the temperature-response equation was applied to rescale monthly fluxes from each grid cell to the predicted mean temperature of the corresponding months under each SSP climate scenario and time period.

The mean temperature sensitivity factor in equation (1), θ was 1.18 based on in situ flux temperature sensitivity studies in specific systems (Extended Data Table 3). To constrain θ further, we used seasonal temperature variability in the full dataset and fitted θ to minimize the deviation between predicted and observed mean monthly contemporary ebullition in the temperate and boreal–arctic regions (best fit at θ = 1.15 and 1.22, respectively; Fig. 5). Only ebullition was considered because the predicted future direct temperature response via θ only regarded ebullition as described above. The lack of distinct temperature seasonality at lower latitudes prevented this type of θ optimization and instead the mean θ value for tropical–subtropical in situ temperature sensitivity studies was used (θ = 1.09), being close to the minimum observations of 1.08 (Extended Data Table 3) and reducing the risk of overestimating the temperature sensitivity at these latitudes, contributing to making the results conservative.

Notably, the temperature sensitivity relationships derived using in situ observations represent the total integrated temperature influence on emissions via both biochemical reactions rates and substrate supply rates (via temperature effects on biological productivity) regarding CH4 production and CH4 oxidation and on CH4 transport processes that are correlated with temperature.

Episodic high-latitude CH4 fluxes upon ice-out and water column turnover events

The grid-specific water freeze/thaw prediction affects open-water diffusive flux and ebullition via the ice-free season length. This seasonality also affects fluxes from accumulated CH4 under ice upon ice melt and spring water column turnover and from accumulated CH4 during summer stratification upon fall water column turnover8,64. To include such effects, we assumed that sediment CH4 production and water column accumulation could be estimated from ebullition rates scaled to bottom water temperatures of 5 °C under present climate to 7 °C by the end of century38. The accumulation was initiated after a 60 ± 15-day lag phase as observed in situ65,66. A substantial fraction of the accumulated CH4 is considered to be oxidized in the water before being emitted (75–89%; range used in uncertainty analysis)19,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75. Equations (4) and (5) below were used.

where EIS represents the calculated combined daily ice out and spring turnover emissions rate (mg CH4 m−2 d−1), DICE is the length of the ice-cover season for each model grid, LT is the accumulation lag phase, Em is the lake type-specific annual-averaged emissions rate, Lb is the burst length of ice-out emissions (assumed to occur for 14 days around ice melt), and Fmox is the daily oxidation fraction.

where EF represents the calculated daily fall turnover emissions rate (mg CH4 m−2 d−1) and other factors as above. Lb for fall turnover was assumed to be 7 days.

Scaling of large lake fluxes

Presently available flux data from large lakes are rare but indicates that emissions per m2 from lakes ≥ 5,000 km2 are in the range of 0–25% of emissions from smaller lakes2. Therefore, a corresponding scaling factor for such large lakes were used (average 0.1 but the full range of 0–0.25 used in uncertainty analyses).

Reservoir emissions pathways

For reservoirs, the emissions from turbine degassing and downstream riverine fluxes were not considered. Such fluxes have been estimated to amount for more than one-third of reservoir emissions33 but are linked to reservoir design and whether the turbine inlet is positioned in anoxic water with large amounts of accumulated CH4 or in oxic water with little CH4. Given the primary dependency of technical design, this flux was not considered to be sensitive to environmental change in the same way as other targeted flux pathways.

Effects of future water area changes on fluxes

Whereas the global lake water storage in the largest lakes has declined over the period of 1992–202076, the total lake area has increased 0.71% from 1988 to 201577. This area increase was linked primarily to smaller lakes, which also emit more CH4 per area unit50. Whereas it is difficult to predict lake area by the end of the century, a continued increase seems reasonable because of projections of increased precipitation in already humid lake-rich regions78. We estimated the maximum lake area increase by the end of the century from linear projection of the recent trend77 resulting in a 2.6% increase in lake area. However, future precipitation may be irregular, and some areas predicted to get increased annual mean precipitation may still have long dry summer periods, making a smaller change in lake area possible. We therefore also included half the extrapolated increase, 1.3%, by the end of the century as a realistic low-end global scenario and applied an in-between estimated change factor of 1.02 using 1.013 and 1.026 as uncertainty range ( ± 1 SD) to estimate possible contribution of lake area change to future fluxes from non-thermokarst lakes. It is premature to try to distinguish the geospatial distribution of this effect at present given the uncertain area distribution of lakes < 0.1 km2, and overall results indicate that the temperature-related effects are much greater than the possible area change effects (Table 1). Hence, the change factors for effects of future water area were applied by ecoclimatic region and lake types (Table 1).

The future distribution of thermokarst lakes, formed from thawing of permafrost and having high areal CH4 emissions, is debated. Whereas models predict increased thermokarst abundance and area in the near future, remote sensing has revealed that thermokarst lake area has decreased between 2000 and 2021 in spite of rapidly ongoing permafrost thaw79. These actual observations showed an area decrease rate of 0.0007 to 0.0013 yr−1, which would correspond to a 7.3–10.6% loss of thermokarst lake area by the end of the century. A mean change factor of 0.91 (9% loss) was used to modulate the model predictions for thermokarst lakes and the full range was used as an estimate of ±1 SD in the uncertainty analysis.

Reservoir area is likely to increase considerably if the plans for new reservoirs are realized. Recent increases in reservoir area revealed by remote sensing during 1988–2015 corresponded to 9.5% resulting in a 35% increase by end of the century if extrapolated77. Half of this area increase was arbitrarily considered as a low-end estimate (17.5% increase), assuming some plans may be abandoned as alternative power sources are becoming more cost effective. We used a mean change factor between these estimates (1.26) when estimating effects of end-of-century reservoir area while the range of 17.5 to 35% increase was used as a ± 1 SD estimate in the uncertainty analysis. This is comparable with another recent study estimating reservoir areas to increase by 21% between 2010 and 204033 probably followed by gradual stabilization as suitable new sites for reservoir construction becomes increasingly depleted and solar and wind power becomes more competitive.

Possible influence on fluxes from changes in nutrient levels

Increased nutrient levels have been shown to stimulate CH4 fluxes via increased primary productivity80 and it has been suggested that eutrophication will increase future inland water CH4 emissions81. To estimate the magnitude of the nutrient change effect we combined the relationship between CH4 emissions and total phosphorous (P) concentrations developed by Beaulieu et al. (2016; data from their Table 2)81 and projected future river P export (proxy for catchment nutrient load) under different SSP climate scenarios until 205028. The river P export was projected separately for the industrialized countries (IC; largely corresponding to temperate, boreal, subarctic, and arctic regions in our regionalization), and Brazil, India and China (BIC) and the rest of the world (RW) which were approximated to our subtropical and tropical regions). It was concluded that river P transport will change by −18.2 to +4.5 % in the industrialized world (decrease in all but the SSP3 scenario) and by +12.0 to +36.0% in BIC + RW. We assumed increased P prices along with development of more effective fertilization practices and better sewage treatment globally by 2050, which will counteract further BIC + RW eutrophication as observed in the past trajectory for industrialized countries. We therefore used 2050 projections also for end-of-century CH4 emissions estimates. These P changes translate to CH4 flux change factors ranging from 0.90 (10% decrease) to 1.19 (19% increase) depending on ecoclimatic region and SSP climate scenario (Table 1). Notably, the predicted nutrient load effect was lower under the SSP5-8.5 scenario than under the SSP3-7.0 scenario28.

This assessment has two main types of uncertainties. One is the relationship between CH4 fluxes and P, which were derived by combining relationships between CH4 fluxes and chlorophyll-a concentrations and between P and chlorophyll-a81. This link between productivity and CH4 emissions is highly uncertain in terms of absolute fluxes, with R2 values in the order of 0.3 and a CH4 emissions 95% confidence interval being of similar magnitude as the mean CH4 emissions81. Therefore, the CH4 emissions versus P equation was tested with coefficients representing the low and high bounds of the 95% confidence interval. Despite large differences in absolute fluxes among models, the proportional relative effect of changing P load on fluxes (change factors in Table 1) were largely consistent and within 4% of the mean (best-estimate) model. The other type of uncertainty regards the estimated future changes in P load. This uncertainty is probably large and in the absence of uncertainty estimates in the source information, we estimated ±1 SD in our uncertainty analysis by using the full range of P change estimates across all regions and climate scenarios (that is, after applying the change factors 0.89 and 1.21 in Table 1). Thereby, we possibly overestimate the uncertainty for single regions and under single climate scenarios.

Uncertainty estimation

The uncertainty estimates calculated for reservoir and lake emissions integrated up to 11 factors. Total uncertainty linked to individual observations (\(\varepsilon\)) was expressed as the integrated coefficient of variation (CV) as percent of the mean in our CH4 emissions estimate. The calculation for lakes propagated individual uncorrelated uncertainties from each factor including the temperature in the climate scenarios (εT), ice-free time projections (εi), soil temperature threshold used to separate temperate and tropical/subtropical regions (εt), diffusive and ebullitive emissions measurements (εv), temperature sensitivity of ebullition (εθ), lag time for CH4 accumulation for calculating ice out (εai) and fall water-column turnover flux (εaf), the fraction of accumulated CH4 which is oxidized (εox) and emissions scaling factors applied to large lakes (εsf), the lake-area change effect including thermokarst and non-thermokarst lakes (εar) and the effect of nutrient levels change on fluxes (εn) through equation (2).

The same uncertainty propagation was applied for reservoirs by implementing relevant uncertainties from εT, εi, εt, εv, εθ, εar and εn in equation (6).

To compare the relative uncertainty contributions from the different factors, proportional effects on equation (6) results with all factors included, versus with each factor omitted was estimated (Fig. 5).

Design choices and associated uncertainty and limitations

Overall, our aim was to model spatio-temporally explicit environmental change effects on CH4 fluxes from reservoirs and lakes based on quantitative and in situ supported information. Because long time series of in situ observed lake or reservoir CH4 emissions are missing, it was not possible to validate our model versus historical trends. Furthermore, because of the aim to focus on in situ observations, to minimize the dependency of many ex situ determined predictors and to avoid added uncertainty from separate predictor models, our approach was developed with inspiration from wetland models developed at stages when the lack of systematic data over time was similar to the current lake and reservoir situation35,82,83 and predict regional averages over 20-year time periods. This excludes the option of validation using predicted versus observed data for specific systems. Further, the need to group data by ecoclimatic regions and lake types to enhance spatial data representativity, made Monte Carlo approaches to estimate uncertainty suboptimal. The reliability of our approach therefore is linked to key tradeoffs as exemplified below:

(1) One core assumption is that the data available (after quality control and consideration of transparency and method compatibility) properly represents the different system types, ecoclimatic regions and flux types. Given that the results are generated from most of the available data that covers all ecoclimatic regions and a great variety of environmental conditions (Extended Data Fig. 2), the degree of comprehensiveness and representativity should be as high as presently possible. As for all global predictive ecosystem models, data availability and coverage are typically more restricted than desired and additional systematic observations covering the lake-rich regions will be beneficial for improving the flux estimates. Importantly, the results on relative flux changes are less sensitive to the representation bias than the absolute fluxes.

(2) Another key related aspect is that future projections were based on available quality-approved in situ observations not only for the CH4 fluxes but also for the predictors. For the predictor variables historic in situ verified trajectories (for example, ice cover periods, lake area and river P) were used, along with attempts to incorporate their uncertainty in the analysis as described above. Accordingly, the factors considered, and their variability among environmental conditions, integrates the in situ complexity of all the underlying processes under as many environmental conditions as possible. This yields robustness to insufficient process understanding and to effects of unexpected nonlinear process interactions.

(3) Further, the choice to constrain predictions to present in situ observations and present mechanistic understanding by relatively simple and transparent calculations, along with the averaging to grids and ecoclimatic regions, leads to both limitations and benefits. One of the limitations is a potential conservative bias because nonlinear effects from unexpected process interactions will not be predicted. Other limitations are not having as high spatio-temporal resolution predictions as in more detailed process-based models, nor taking advantage of the latest developments regarding data-driven models by machine learning. On the other hand, benefits of our approach include having the above-mentioned high robustness to unrealistic predictions from nonlinear process interactions that may otherwise progress unconstrained over time. Similarly, the risks associated with applying machine learning models outside the training data domains is reduced. The typical way to mitigate these issues in both process-based and data-driven modelling, by validation of predictions via hindcasting is not possible because of the lack of time series data. Accordingly, the transparency and simplicity of our approach is beneficial by greatly facilitating the detection of unreasonable results.

(4) Additional aspects of the choice of a grid-based approach include that the grid-specific uncertainty is dependent on how well the lakes in a specific grid reflect the regional observation data imposed on that grid via the model. A grid cell with many lakes will probably represent the regional-scale variability better than a grid cell with only one lake. This means that the uncertainty at specific grids can be higher or lower than the aggregated regional estimates, in a similar way as the uncertainty for individual years may differ from the uncertainty for the integrated 20-year time periods. Generally, the associated grid-specific spatial uncertainty generated by lake aggregation is expected to be higher at lower latitudes, south of the lake-rich landscapes influenced by the last glaciation (compare with the lake density map by grid in Fig. 2a in ref. 8). These areas account for a high share of both current and future emissions, highlighting the need to generate enough data to allow future evaluation of the lake aggregation effects in grid-based models. The focus on uncertainty at the regional scale in this study was to ensure that uncertainty was analysed at compatible scales for all included information (for example, Fig. 5a), incorporating the fundamental spatial uncertainty associated with the spatial integration of the original observations.

The grid-based approach also means that individual lakes and their characteristics were not considered specifically. Consequently, some lake morphometry features known to influence CH4 emissions, such as depth, were not considered in individual lakes and it was assumed that data from the respective ecoclimatic regions to a reasonable extent represents the associated lake characteristics. Such morphometry characteristics, including annual mean depth, could also be considered largely constant over time, supported by the small predicted change in lake area over time. This makes the estimated relative flux change less sensitive to a data bias than the absolute flux estimates. Another benefit of the grid choice is compatibility with other gridded products.

(5) The temperature sensitivity θ is a key variable for extrapolation among seasons and years and it yielded the highest potential uncertainty of all factors when using traditional error propagation based on SD of individual system observations (Fig. 5a). However, after regional optimization of θ to monthly average fluxes in our dataset, the integrated uncertainty was substantially reduced (Fig. 5b). This indicates that classical error propagation overestimated the uncertainty and that our approach was capable of predicting temperature effects at a better-than-expected accuracy given the high variability among individual flux observations. Still, we acknowledge a need for more in situ studies of CH4 flux temperature sensitivity at all latitudes and in all types of systems for improved future predictions.

Any temperature sensitivity model can have intrinsic features that make the associated temperature-sensitivity coefficient influenced by the absolute temperature range considered. This is important to consider when making comparisons across latitudes. We evaluated this using the standard Arrhenius equation for a theoretical process with an activation energy of 70 kJ mol−1 as reference case. We then calculated θ for this process at each temperature from 0 to 50 °C, which revealed that θ decreased 0.04 % per °C compared to the reference relationship. Accordingly, an increase in the mean temperature of as much as 10 °C would decrease θ by less than 0.5%, which is minor compared with the uncertainty margins of approximately 20% (Fig. 5b). Further, this effect was mitigated by the θ optimization at the temperate and boreal–arctic regions that calibrated θ to the regional in situ observations, and by using a low-end θ for tropical and subtropical latitudes.

(6) Effects of factors with large local uncertainty and being important for fluxes in specific regions, for example, ice-out and seasonal water-column turnover emissions are in general challenging to predict, and our approach can only provide regional average estimates. However, these factors contributed small shares of the total global fluxes and flux changes and thereby also probably small shares of the prediction uncertainty (Fig. 5a).

(7) There is of course also some uncertainty associated with the used climate scenarios. To their support, the contemporary (2000–2019) gridded temperatures from the ensemble climate model used was successfully validated to observations (described above in paragraph Temperature predictions from climate change scenarios). Beyond this validation, we rely on extensive past work to derive and evaluate the climate scenarios. For this study the core aspect is that they encompass the likely range of future conditions.

Overall, the core strategies behind our approach were to maximum robustness, firm connections to in situ observations, in situ verified relationships and mechanistic understanding, minimize the need for assumptions, along with transparency and simplicity, based on careful consideration of amounts and characteristics of available data. While we thereby chose a simpler approach compared to more complex alternative approaches, the strategies were successful in yielding predictions that are well supported by, and highly realistic compared to, in situ observations from widely different conditions. The methods were also designed to generate conservative predictions and avoid unconstrained overestimates. Hence, the distinct results of large climate change effects on lake and reservoir CH4 emissions, showing clearly how we need to change our view on natural GHG flux balances and their climate sensitivity, are more likely underestimated than the opposite, making the main conclusions highly robust.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data used to derive the results are deposited via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17193077 (ref. 84).

Code availability

The Matlab code used to derive the results is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17193077 (ref. 84).

References

Mar, K. A., Unger, C., Walderdorff, L. & Butler, T. Beyond CO2 equivalence: the impacts of methane on climate, ecosystems, and health. Environ. Sci. Policy 134, 127–136 (2022).

Forster, P. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 923–1054 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Saunois, M. et al. The global methane budget 2000–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 1561–1623 (2020).

Peng, S. et al. Wetland emission and atmospheric sink changes explain methane growth in 2020. Nature 612, 477–482 (2022).

Cheng, C.-H. & Redfern, S. A. T. Impact of interannual and multidecadal trends on methane-climate feedbacks and sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 13, 3592 (2022).

Bastviken, D., Tranvik, L. J., Downing, J. A., Crill, P. M. & Enrich-Prast, A. Freshwater methane emissions offset the continental carbon sink. Science 331, 50 (2011).

Johnson, M. S. et al. Spatiotemporal methane emission from global reservoirs. J. Geosphys. Res. Biogeosci. 126, e2021JG006305 (2021).

Johnson, M. S., Matthews, E., Du, J., Genovese, V. & Bastviken, D. Methane emission from global lakes: new spatiotemporal data and observation-driven modeling of methane dynamics indicates lower emissions. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 127, e2022JG006793 (2022).

Rosentreter, J. A. et al. Half of global methane emissions come from highly variable aquatic ecosystem sources. Nat. Geosci. 14, 225–230 (2021).

Deemer, B. R. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from reservoir water surfaces: a new global synthesis. Bioscience 66, 949–964 (2016).

Harrison, J. A., Prairie, Y. T., Mercier-Blais, S. & Soued, C. Year-2020 global distribution and pathways of reservoir methane and carbon dioxide emissions according to the greenhouse gas from reservoirs (G-res) model. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 35, e2020GB006888 (2021).

Zhuang, Q. et al. Current and future global lake methane emissions: a process-based modeling analysis. J. Geosphys. Res. Biogeosci. 128, e2022JG007137 (2023).

Bastviken, D. in Encyclopedia of Inland Waters 2nd edn (eds Mehner, T. & Tockner, K.) 136–154 (Elsevier, 2022).

Hartmann, J. F. et al. High spatiotemporal dynamics of methane production and emission in oxic surface water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 1451–1463 (2020).

Deemer, B. R. & Holgerson, M. A. Drivers of methane flux differ between lakes and reservoirs, complicating global upscaling efforts. J. Geosphy. Res. Biogeosci. 126, e2019JG005600 (2021).

Marotta, H. et al. Greenhouse gas production in low-latitude lake sediments responds strongly to warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 467–470 (2014).

Yvon-Durocher, G. et al. Methane fluxes show consistent temperature dependence across microbial to ecosystem scales. Nature 507, 488–491 (2014).

Aben, R. C. H. et al. Cross continental increase in methane ebullition under climate change. Nat. Commun. 8, 1682 (2017).

Natchimuthu, S. et al. Spatio-temporal variability of lake CH4 fluxes and its influence on annual whole lake emission estimates. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, S13–S26 (2016).

Matthews, E., Johnson, M. S., Genovese, V., Du, J. & Bastviken, D. Methane emission from high latitude lakes: methane-centric lake classification and satellite-driven annual cycle of emissions. Sci. Rep. 10, 12465 (2020).

Thornton, B. F., Wik, M. & Crill, P. M. Climate-forced changes in available energy and methane bubbling from subarctic lakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 1936–1942 (2015).

Guo, M. Y. et al. Rising methane emissions from boreal lakes due to increasing ice-free days. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 064008 (2020).

Wik, M., Varner, R. K., Anthony, K. W., MacIntyre, S. & Bastviken, D. Climate-sensitive northern lakes and ponds are critical components of methane release. Nat. Geosci. 9, 99–105 (2016).

Duc, N. T., Crill, P. & Bastviken, D. Implications of temperature and sediment characteristics on methane formation and oxidation in lake sediments. Biogeochemistry 100, 185–196 (2010).

Davidson, T. A. et al. Synergy between nutrients and warming enhances methane ebullition from experimental lakes. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 156–160 (2018).

Knoblauch, C., Beer, C., Liebner, S., Grigoriev, M. N. & Pfeiffer, E.-M. Methane production as key to the greenhouse gas budget of thawing permafrost. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 309–312 (2018).

IPCC Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Beusen, A. H. W. & Bouwman, A. F. Future projections of river nutrient export to the global coastal ocean show persisting nitrogen and phosphorus distortion. Front. Water 4, 893585 (2022).

Gudasz, C., Karlsson, J. & Bastviken, D. When does temperature matter for ecosystem respiration? Environ. Res. Commun. 3, 121001 (2021).

Grinham, A. et al. The importance of small artificial water bodies as sources of methane emissions in Queensland, Australia. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 5281–5298 (2018).

Dong, B., Xi, Y., Cui, Y. & Peng, S. Quantifying methane emissions from aquaculture ponds in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 1576–1583 (2023).

Malerba, M. E., de Kluyver, T., Wright, N., Schuster, L. & Macreadie, P. I. Methane emissions from agricultural ponds are underestimated in national greenhouse gas inventories. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 306 (2022).

Soued, C., Harrison, J. A., Mercier-Blais, S. & Prairie, Y. T. Reservoir CO2 and CH4 emissions and their climate impact over the period 1900–2060. Nat. Geosci. 15, 700–705 (2022).

Kuhn, M. A. et al. Opposing effects of climate and permafrost thaw on CH4 and CO2 emissions from northern lakes. AGU Adv. 2, e2021AV000515 (2021).

Kuhn, M. A. et al. BAWLD-CH4: a comprehensive dataset of methane fluxes from boreal and arctic ecosystems. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 5151–5189 (2021).

Bastviken, D. et al. The importance of plants for methane emission at the ecosystem scale. Aquat. Bot. 184, 103596 (2023).

Bodmer, P., Vroom, R. J. E., Stepina, T., del Giorgio, P. A. & Kosten, S. Methane dynamics in vegetated habitats in inland waters: quantification, regulation, and global significance. Front. Water 5, 1332968 (2024).

Jansen, J. et al. Global increase in methane production under future warming of lake bottom waters. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 5427–5440 (2022).

Reay, D. S., Smith, P., Christensen, T. R., James, R. H. & Clark, H. Methane and global environmental change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 43, 165–192 (2018).

Canadell, J. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 673–816 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Koffi, E. N., Bergamaschi, P., Alkama, R. & Cescatti, A. An observation-constrained assessment of the climate sensitivity and future trajectories of wetland methane emissions. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay4444 (2020).

Global Wetland Outlook: State of the World’s Wetlands and their Services to People (Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, 2018).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Li, M. et al. The significant contribution of lake depth in regulating global lake diffusive methane emissions. Water Res. 172, 115465 (2020).

Borges, A. V. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from African lakes are no longer a blind spot. Sci. Adv. 8, eabi8716 (2022).

Gelaro, R. et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (2017).

Messager, M. L., Lehner, B., Grill, G., Nedeva, I. & Schmitt, O. Estimating the volume and age of water stored in global lakes using a geo-statistical approach. Nat. Commun. 7, 13603 (2016).

Olefeldt, D. et al. The Boreal–Arctic Wetland and Lake Dataset (BAWLD). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 5127–5149 (2021).

Lamarche, C. et al. Compilation and validation of SAR and optical data products for a complete and global map of inland/ocean water tailored to the climate modeling community. Remote Sens. 9, 36 (2017).

Holgerson, M. A. & Raymond, P. A. Large contribution to inland water CO2 and CH4 emissions from very small ponds. Nat. Geosci. 9, 222 (2016).

Rasilo, T., Prairie, Y. T. & del Giorgio, P. A. Large-scale patterns in summer diffusive CH4 fluxes across boreal lakes, and contribution to diffusive C emissions. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 1124–1139 (2015).

Livingstone, D. M. & Lotter, A. F. The relationship between air and water temperatures in lakes of the Swiss Plateau: a case study with palaeolimnological implications. J. Paleolimnol. 19, 181–198 (1998).

Yu, S. J., Ryu, I. G., Park, M. J. & Im, J. K. Long-term relationship between air and water temperatures in Lake Paldang, South Korea. Environ. Eng. Res. 26, 200177–200170 (2021).

Heddam, S., Ptak, M. & Zhu, S. Modelling of daily lake surface water temperature from air temperature: extremely randomized trees (ERT) versus Air2Water, MARS, M5Tree, RF and MLPNN. J. Hydrol. 588, 125130 (2020).

Sieczko, A. K. et al. Diel variability of methane emissions from lakes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 21488–21494 (2020).

Praetzel, L. S. E., Schmiedeskamp, M. & Knorr, K. H. Temperature and sediment properties drive spatiotemporal variability of methane ebullition in a small and shallow temperate lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 66, 2598–2610 (2021).

van Bergen, T. et al. Seasonal and diel variation in greenhouse gas emissions from an urban pond and its major drivers. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 2129–2139 (2019).

McClure, R. P. et al. The magnitude and drivers of methane ebullition and diffusion vary on a longitudinal gradient in a small freshwater reservoir. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 125, e2019JG005205 (2020).

Barbosa, P. M., Melack, J. M., Amaral, J. H. F., Linkhorst, A. & Forsberg, B. R. Large seasonal and habitat differences in methane ebullition on the Amazon floodplain. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 126, e2020JG005911 (2021).

Maher, D. T., Drexl, M., Tait, D. R., Johnston, S. G. & Jeffrey, L. C. iAMES: an inexpensive, automated methane ebullition sensor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 6420–6426 (2019).

Linkhorst, A. et al. Comparing methane ebullition variability across space and time in a Brazilian reservoir. Limnol. Oceanogr. 65, 1623–1634 (2020).

Wik, M. et al. Energy input is primary controller of methane bubbling in subarctic lakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 555–560 (2014).

Xun, F. et al. Methane ebullition fluxes and temperature sensitivity in a shallow lake. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 169589 (2024).

Michmerhuizen, C. M., Striegl, R. G. & McDonald, M. E. Potential methane emmision from north-temperate lakes following ice melt. Limnol. Oceanogr. 41, 985–991 (1996).

Jansen, J. et al. Climate-sensitive controls on large spring emissions of CH4 and CO2 From northern lakes. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 124, 2379–2399 (2019).

Vachon, D., Langenegger, T., Donis, D. & McGinnis, D. F. Influence of water column stratification and mixing patterns on the fate of methane produced in deep sediments of a small eutrophic lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 2114–2128 (2019).

Utsumi, M. et al. Oxidation of dissolved methane in a eutrophic, shallow lake: Lake Kasumigaura, Japan. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 471–480 (1998).

Striegl, R. G. & Michmerhuisen, C. M. Hydrologic influence on methane and carbon dioxide dynamics at two north-central Minnesota lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 1519–1529 (1998).

Kankaala, P., Taipale, S., Nykanen, H. & Jones, R. I. Oxidation, efflux, and isotopic fractionation of methane during autumnal turnover in a polyhumic, boreal lake. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 112, G02033 (2007).

Schubert, C. J., Diem, T. & Eugster, W. Methane emissions from a small wind shielded lake determined by eddy covariance, flux chambers, anchored funnels, and boundary model calculations: a comparison. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 4515–4522 (2012).

Boereboom, T., Depoorter, M., Coppens, S. & Tison, J. L. Gas properties of winter lake ice in northern Sweden: implication for carbon gas release. Biogeosciences 9, 827–838 (2012).

Fernandez, J. E., Peeters, F. & Hofmann, H. Importance of the autumn overturn and anoxic conditions in the hypolimnion for the annual methane emissions from a temperate lake. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 7297–7304 (2014).

Mayr, M. J. et al. Growth and rapid succession of methanotrophs effectively limit methane release during lake overturn. Commun. Biol. 3, 108 (2020).

Zimmermann, M. et al. Microbial methane oxidation efficiency and robustness during lake overturn. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 6, 320–328 (2021).

Pajala, G. et al. The effects of water column dissolved oxygen concentrations on lake methane emissions—results from a whole-lake oxygenation experiment. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 128, e2022JG007185 (2023).

Yao, F. et al. Satellites reveal widespread decline in global lake water storage. Science 380, 743–749 (2023).

Pi, X. et al. Mapping global lake dynamics reveals the emerging roles of small lakes. Nat. Commun. 13, 5777 (2022).

Lee, J.-Y. et al. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 553–672 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Webb, E. E. et al. Permafrost thaw drives surface water decline across lake-rich regions of the Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 841–846 (2022).

Davidson, T. A. et al. Eutrophication effects on greenhouse gas fluxes from shallow-lake mesocosms override those of climate warming. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 4449–4463 (2015).

Beaulieu, J. J., DelSontro, T. & Downing, J. A. Eutrophication will increase methane emissions from lakes and impoundments during the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 10, 1375 (2019).

Forbrich, I. et al. Three decades of wetland methane surface flux modeling by Earth system models—advances, applications, and challenges. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 129, e2023JG007915 (2024).

Wania, R. et al. Present state of global wetland extent and wetland methane modelling: methodology of a model inter-comparison project (WETCHIMP). Geosci. Model Dev. 6, 617–641 (2013).

Johnson, M. S., & Bastviken, D. Meta information associated with the publication ‘Future methane emission from lakes and reservoirs’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17193077 (2025)

Acknowledgements

D.B. acknowledges support from the European Research Council (ERC H2020 grant number 725546 METLAKE), the Swedish Research Councils VR (grant number 2016-04829 and 2022-03841), Formas (grant number 2018-01794) and Linköping University. M.S.J. was funded for this work by NASA’s Interdisciplinary Research in Earth Science (IDS) Program and the NASA Terrestrial Ecology and Tropospheric Composition Programs. We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme, which, through its Working Group on Coupled Modelling, coordinated and promoted the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6). We thank the climate modelling groups for producing and making available their model output, the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) for archiving the data and providing access and the multiple funding agencies who support CMIP6 and ESGF. We specifically thank the institutions that provided the climate models: The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO; Australia); Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (Germany); Beijing Climate Center (China); Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences (China); Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis (Canada); National Center for Atmospheric Research (USA); Centro Euro-Mediterraneo sui Cambiamenti Climatici (Italy); CNRM-CERFACS (National Center for Meteorological Research; France); Institute of Atmospheric Physics (China); National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)-Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (USA); Institute for Numerical Mathematic (Russia); Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace (France); National Institute of Meteorological Sciences, Korea Meteorological Administration (South Korea); University of Arizona (USA); Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC, National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES), Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute (AORI), University of Tokyo (Japan); Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Deutsches Klimarechenzentrum and Deutscher Wetterdienst (Germany); Meteorological Research Institute (Japan); Norwegian Climate Center (Norway); Research Center for Environmental Changes, Academia Sinica (Taiwan); Met Office Hadley Center (UK) and Natural Environment Research Council (UK).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Linköping University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This manuscript was developed in close collaboration between the authors regarding all aspects. D.B. had responsibility for conceptualization and drafting the first version of the manuscript, and M.S.J. had responsibility for the modelling and data representation. For other parts there was shared responsibility.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Water thanks Gavin McNicol and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Geospatial distribution of temperatures in different climate scenarios.

Extended Data Fig. 1. Geospatial distribution of contemporary (2000-2019) yearly mean 2-metre air temperature from the five CMIP6 model ensemble by grid cell (a), and the predicted change by 2080-2099 under SSP1-2.6 (b), SSP2-4.5 (c), SSP3-7.0 (c) and SSP5-8.5 (d) climate scenarios using the 20 model ensemble described in Extended Data Table 5. Global mean temperature changes are denoted in the upper right of panels b), c), d), and e).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Geospatial distribution of lakes, reservoirs and flux measurements.

Extended Data Fig. 2. The geospatial distribution of (a) lakes and (b) reservoirs in different ecoclimatic regions, and locations of the flux measurements included in the analysis (black spots). Please note that the color bars differ between panels.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bastviken, D., Johnson, M.S. Future methane emissions from lakes and reservoirs. Nat Water 3, 1397–1410 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00532-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00532-6