Abstract

Emotion expressions constitute a vital channel for communication, coordination and connection with others, but despite such valuable functions, people sometimes engage in expressive suppression or substitution (expressing emotions they do not genuinely feel). Yet, how exactly do people decide when and what to express? To answer this question, we developed a computational model that casts emotion expressions as value-based communicative decisions. Our model reveals that while people (N = 254) indeed tended to suppress expressions of anger towards others in anticipation of potential social costs as past work theorizes, they also engaged in other nuanced forms of expressive regulation, especially when their reputation was at stake. Most strikingly, people selectively exaggerated/suppressed expressions of happiness when others made more/less equitable choices, seemingly to communicate stronger normative preferences for fairness than they privately held. Together, these findings yield insights into how people regulate their emotion expressions, providing a mechanistic and unified account of the different expressive behaviors people flexibly engage in to navigate their complex social interactions with others.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emotion expressions are inherently social, and exert a powerful influence on others’ behavior1,2,3. By efficiently communicating one’s evaluations of their environment4,5,6, emotion expressions serve important functions in coordinating and regulating people’s social lives—facilitating social relationships, deterring social transgressions, and eliciting prosocial behavior7,8,9,10. These adaptive socio-communicative functions of emotion expressions have been so thoroughly documented that researchers posit evolutionary pressures may have hard-wired human physiology to produce outward-facing expressions of internally-felt emotion4,11,12.

Yet, if communicating emotion is so valuable, why do people so often suppress their emotions13,14,15,16,17,18,19, or express emotions they do not genuinely feel20,21,22,23? Implicit in the tension between these observations is that despite furnishing communicative benefits, veridically expressing felt emotions (particularly negative ones) sometimes incurs costs to the expresser24,25,26,27,28,29. What precisely these costs are, where they come from, and how people consider them when deciding whether to express, suppress, or exaggerate/fake their emotions remain poorly understood, in part because it can be difficult to precisely quantify the calculations people make in such decisions. For example, what specific calculations do people make when deciding whether to express or suppress anger? When, why, and how might people mask anger with sadness, or exaggerate positive emotions they do not feel? Answering these questions would not only advance our understanding of fundamental socio-psychological processes, but also provide insight into how persistent patterns of expressive behavior might disrupt interpersonal processes and exacerbate personal, organizational, and societal ill-being8,21,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44.

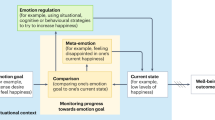

Here, we develop a precise mathematical and algorithmic model of emotion expression, based on two key assumptions that seamlessly accounts for a variety of expressive behaviors and provides a means for rigorously quantifying their communicative value. Our first assumption, consistent with work viewing other forms of emotion regulation as a value-based choice45,46,47, is that expressing one’s emotion to another constitutes a value-based decision. Whether a person chooses to express their emotions and what they express depends on the overall anticipated communicative value of the specific expression. In other words, expressing an emotion has the potential to both furnish some communicative benefits and incur some social costs, while suppressing it avoids the associated costs at the expense of any corresponding benefits. As an example, imagine feeling angry about being passed over for an opportunity at work. Expressing anger might invite others to correct the situation but also risks leaving a bad impression and further exclusion in the future. Suppressing it avoids these reputational costs but also leaves the situation unremedied. Moreover, by emphasizing the communicative goals of expressions, our model also considers that expression is a choice not just between expressing or suppressing a single emotion, but rather a choice between many possible emotion expressions, each of which communicates different information and thus furnish different benefits and incur different costs48. This in turn can lead to expressions of secondary, or even unfelt, emotions. For example, although expressing anger might risk ostracization, expressing sadness might instead elicit sympathy from others while still communicating discontent. Thus, one might express sadness in the aforementioned example, despite primarily feeling angry, because of the net value it provides over veridical emotion expression and full-blown suppression.

Second, our model assumes that the communicative value of different emotion expressions varies across individuals and contexts. Drawing on work in other domains of value-based decision-making49,50,51, our model emphasizes that people not only evaluate what emotion to express, if at all, by comparing the value of different options, but also actively construct each option’s value based on their own idiosyncratic goals and relevant features of the social environment. Importantly, an expression’s communicative value depends on contextual features in two ways. Different social environments may directly amplify or diminish the inherent social costs or benefits of emotion expression. For example, expressing anger or happiness to one’s boss vs. a co-worker could come both with greater benefits, but also greater costs, due to their power to shape one’s career progress. Such a prediction is consistent with existing work showing that people report regulating their emotion expressions more when others hold more power over them52,53.

Additionally, the communicative value of expressions might derive indirectly from the information that it conveys about the expresser’s preferences and character5,10,54,55,56,57,58. Expressing anger at a lost opportunity might plainly communicate discontent, but the specific context of this expression allows perceivers to infer why59. For instance, if the loss was unjust and the opportunity was given to someone undeserving, expressing anger might signal admirable preferences for fairness. In contrast, if the loss resulted from a fair process, expressing anger might instead signal unsavory selfish preferences. Knowing this, people might choose to communicate emotions that differ from those they might feel across different social interactions not only in response to the potential severity of the immediate consequences but also to more finely modulate the signals they send to others about their preferences. Our model allows us to capture both these considerations simultaneously by quantifying the degree to which different emotion expressions vary in accordance with specific features—e.g., reputational stakes, fairness, etc.—of the social environment.

Notably, our model conceptualizes people’s expressive decisions as ultimately resulting from the accumulation of value-based evidence towards a threshold for choice60,61,62. An advantage of this is that it allows us to precisely quantify the importance of different contextual features in shaping the active process of evaluation and distinguish them from other mechanisms, such as response biases which can simultaneously shape choice by effectively lowering the threshold of evidence for specific expressive options63. Thus, our model identifies these biases as another way people can regulate their emotion expressions, capturing how they might prime themselves to express a specific emotion or inhibit expression altogether—e.g., when people proactively ready their poker face or a polite smile in anticipation of any situation.

To interrogate and precisely quantify how these distinct mechanisms contribute to people’s regulation of their emotion expressions, we recruited participants for a pre-registered study (N = 254) in which they engaged with other individuals behaving generously or selfishly in a variant of the Dictator game64,65 (Fig. 1) and had the opportunity to either privately self-report how they felt about these choices to the experimenters (Nself = 84), anonymously express how they felt to their social partner (Nexp = 87), or express how they felt to their social partner with potential reputational consequences (Nrep = 83). By comparing selection of emojis between participants in the Self-Report, Expression, and Reputation conditions, and modeling these choices as a value-based response, we were able to precisely quantify the communicative value of different emotions in different contexts to test our hypothesis that people flexibly regulate their expressive decisions based on the context-specific costs and benefits of each expressive option.

Participants were presented with two distributions of outcomes for themselves and their partner. They were also informed which distribution their partner chose and asked to report which of four emojis (i.e., neutral, happy, angry, and sad) best represented how they felt or which of four emojis they would like to send to their partner. Each trial is characterized by three situational attributes that captured the difference between the chosen and unchosen option: difference in outcomes for the participant ($Self), difference in outcomes for their partner ($Other), and difference in the absolute inequality of outcomes ($Ineq). For example, in this example trial: $Self = 65 – 50 = 15; $Other = 38 – 50 = –12; $Ineq = | 65 – 38 | – | 50 – 50 | = | 27 | – | 0 | = 27.

Methods

Participants

We recruited 490 participants from Prolific Academic in US and Canada to respond as a recipient to a series of Dictator game choices made by a social partner (the Dictator) using the emoji response wheel to indicate how they felt about these choices (pre-registered at https://osf.io/8yscm). Of the 490 participants recruited, 236 participants were excluded from subsequent analyses based on pre-registered criteria (210 expressed disbelief about either their partners being a real person, that the interactions would impact their bonuses or that their expressions would be conveyed to their partner; 15 did not complete the experiment; two revoked consent to use their data; eight only used one response on > 90% of trials; and one failed comprehension checks on the task; exclusion per condition: Self-Report Nexcl = 93; Expression Nexcl = 75; Reputation Nexcl = 68). After these exclusions, 254 participants remained (Age: Mean = 39.19, SD = 13.497, Range = [18, 78], four participants preferred not to disclose their age, one participant reported their age to be more than 100 and is not included in these summary statistics; Gender: 118 men, 130 women, six non-binary; Participants’ self-reported racial and ethnic identity in this study were collected using a non-exclusive checklist where they could additionally self-identify using an open-ended textbox. 227 participants indicated that they only identified with one of the listed categories (156 White or European American/Canadian, 24 Asian or Asian American/Canadian, 23 Latino or Hispanic or Chicano or Puerto Rican, 21 Black or African American/Canadian, 3 Middle Eastern or North African), 24 either explicitly selected multi-racial and/or indicated two or more categories in their responses, two participants opted to self-identify using the open-ended textbox, and one preferred not to self-identify. Of the two participants who selected “Other” as a response, one specified that they identified as South Asian/Canadian and the other specified that they identified as Hebrew. Participants were compensated US$5 for their time and could win an additional bonus of up to $2 based on the summed outcomes of a randomly select trial from their interactions with each social partner they were paired with. All participants provided informed consent as approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of Toronto.

Procedure

Participants were assigned to one of three conditions where they could choose between four emojis (from the Twemoji database: https://github.com/jdecked/twemoji) corresponding to Neutral, Angry, Happy, and Sad as a response in a Dictator game where they were recipients of monetary distributions that their partners chose. In the “Self-Report” condition (Nself = 84), participants were asked to use the emojis to privately report to us, the experimenters, how they felt about their partner’s choices. In the “Expression” condition (Nexp = 87), they were instead asked to decide which emoji they would like to send to their partner (selecting the neutral response would result in no emoji being sent to their partner). Finally, in the “Reputation” condition (Nexp = 83), they were asked to make the same responses as the Expression condition but were additionally told that their partners would subsequently rate them at the end of the interaction for characteristics such as likability and transmit those ratings to the next partner they interacted with. We acknowledge here that while we sought to measure participants’ subjective feelings in the Self-Report condition, participants’ responses in this condition likely reflect a combination of those feelings with some modest concern of self-presentation to the experimenter. Thus, we primarily focus on comparing how differently participants respond across conditions where their choices have different socio-communicative consequences to identify patterns of expressive regulation and test our hypotheses. To evoke more genuine emotional responses to their partners’ choices, participants were all told that they would receive a monetary bonus at the end of the experiment that was proportional to the outcomes of a randomly selected choice their partners made, and that they had no direct way to influence the outcomes of the choices their partners made. Full instructions for the task can be found in Supplementary Appendix S1.

Each participant encountered 132 trials as a recipient in blocks of 33 trials, with each block representing choices by one of four partners on trials that varied in $Self, $Other and $Ineq. On average, the decider’s choices led to a small loss for the participant (M$Self = -1.979, Range = [-50, 50]), gain for their partner (M$Other = 10.458, Range = [-50, 50]) and increased inequality of outcomes (M$Ineq = 5.420, Range = [-100,100]). Once again, participants were made to believe that they were anonymously interacting with another participant while instead interacting with an algorithmic partner and debriefed after the experiment. However, to ensure that the responses people made in these games were reflective of their true emotional reactions to social behavior, participants were asked whether they (1) believed that they were interacting with a real person, (2) believed that their monetary bonuses were dependent on their partners’ choices, and—for participants who were asked to express their emotions—(3) believed that their expressions were conveyed to their partners. These questions served as a manipulation check and exclusion criterion. To enhance the believability that they are interacting with other people in these dyadic games, prior to the four blocks of recipient trials, participants were told that roles as decider and recipient were randomly assigned on each block and completed an initial series of 33 trials as a Dictator to a social partner in the same emotional response condition. For example, participants in the Self-Report condition decided for partners who they believed privately rated their feelings in this initial block of choices, whereas participants in the Expression and Reputation condition decided for partners who sent them emojis as feedback. This feedback was deterministically programmed into the task such that selfish responses that increased participant’s self-interest to the detriment of their partners’ outcomes were met with negative expressions like anger and sadness while altruistic sacrifices were met with happiness. Additionally, participants in the Reputation condition also subsequently rated their social partners on several characteristics that they were then told would be transmitted to their partners’ subsequent partners. After the experiment, participants were thoroughly debriefed about the deception used in accordance with a protocol approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of Toronto. The pre-registered design, sampling plan and analyses can be found on the Open Science Framework (registered Apr 7 2023: https://osf.io/8yscm). Detailed documentation of coherence to the preregistration can be found in Supplementary Note S1.

We note that the use of a between-participant design in this study sought to circumvent potential confounds in participants’ behavior that might arise from asking them to make different kinds of emotional responses using the same options to similar social interactions. Additionally, research has found that simply identifying and labelling one’s emotions for self-report has been shown to constitute a form of emotion regulation that makes emotions more resistant to subsequent regulation66,67. We considered that these influences could bias participants’ behavior in non-trivial ways, potentially introducing spurious differences and/or occluding key patterns of expressive regulation. Nonetheless, we conducted two supplemental studies using a within-participant comparison of feelings and expressions (without reputation) which demonstrate the robustness of our behavioral findings that people’s emotion expressions consistently deviate from their self-reported feelings (NS1 = 29, NS2 = 111, see Supplementary Note S2).

Behavioral Analyses

To analyze the overall patterns of emoji selection, we employed Bayesian mixed-effects multinomial regressions with random-intercepts fitted for each participant using default priors specified by the package brms68,69. To construct the posterior distribution over parameters of interest, the model iterated over 10,000 Monte-Carlo Markov Chain steps with a burn-in of 2000 across three chains, resulting in 24,000 total samples taken. Comparisons of response frequency between conditions were conducted by transforming estimated model parameters via the softmax function for all posterior traces to construct posterior estimates of response proportions for each emoji in each condition, and their differences between conditions. This in effect reflects a simple effects analysis of the response data. These general linear models of emoji frequency across the conditions were not pre-registered but conducted and reported to illustrate participants’ overall patterns of emotion responses.

The multi-attribute racing diffusion model

To uncover the computational dynamics that underlie both self-reported feelings and expressions of emotion, we fitted a multi-attribute Racing Diffusion Model (maRDM) to participants’ choice and response time data in our paradigm. The model assumes that emotional responses result from an evidence accumulation process where each response option (i.e., emoji) is characterized by its relative value (RV) and threshold for response (b). This relative value (RV) for each emotion response is determined by the average difference between the expected response value (V) of each specific emotion response and all other potential options (Eq. 1). Critically, our model assumes that V itself is constructed out of the weighted sum of situational attributes on the current trial and a value-constant (Eq. 2). Here, we fixed the expected response value of neutrality at 0, assuming that there is no independent evidence for neutral responses (Eq. 2). Consequently, evidence for choosing neutrality is derived entirely from strong evidence against the other emotion response options.

The model then assumes that decision-makers accumulate evidence over time for each option from zero towards their respective thresholds, where each sample of evidence is corrupted by some noise, εt, from a random normal distribution, N(0,1). Choice and response time on a trial is determined by which of the accumulators crosses its threshold first and the time it takes to cross that threshold plus a non-decision time (t0) accounting for pre- and post-decision perceptual and motor processes. Thus, the model contains 17 free parameters that include value-constants (C) and three weights (w) on $Self, $Other, and $Ineq for each of the three non-neutral emotion responses (e.g. Canger, w$self:anger, w$other:anger, w$ineq:anger, Chappiness, w$self:happiness,w$other:happiness, w$ineq:happiness, etc.), four thresholds (b): each associated with one emotion response option (bneutral, banger, bhappiness, bsadness) and a single non-decision time (t0). A model recovery exercise of 1,000 simulated participants based on the task stimuli revealed that this 17-parameter model is identifiable and well recovered by our fitting procedure. Across all parameters, the maximum a posteriori estimates of correlations between the generative and recovered parameters ranged from 0.704 to 0.888 (all 95% HDIs > 0.675, Supplementary Note S3). We note that the differentiability of the value-constants (C) from the corresponding thresholds (b) rely on their distinct influence over response times. Although increasing/decreasing C and decreasing/increasing b both similarly increases the frequency of choosing the corresponding response options, these response times exhibit a non-monotonic inverse u-shaped relationship with changes in C whereas they consistently increase as b increases. While increasingly positive values of C results in faster response times, more and more negative values of C also result in faster response times as negative evidence acts as evidence for the other options in our model and faster responses times when choosing the other alternatives.

Model fitting

Model-fitting was conducted exactly as pre-registered. To ensure the stability of model fits, we conducted additional trial-level exclusions based on pre-registered criteria unique to computational modelling. Specifically, we first excluded all trials that took shorter than 200 ms and trials that took longer than 10 s, and any trials that had logRTs that were 2.5 median absolute deviations from the participant’s median response time70. We then excluded all data from 8 additional participants who lost more than 20% of their data from these trial-based exclusions. We fitted the maRDM to the remaining 246 participants’ (Nself = 82; Nexp = 82; Nrep = 82) choice and response time data hierarchically using Differential Evolution Monte-Carlo Markov Chains (DEMCMC)71,72,73. In short, this method estimates the likelihood of the observed data, derived using a closed-form mathematical solution given a specific combination of parameters60, and uses this likelihood to incrementally construct the posterior distribution of model parameters for each participant by iteratively proposing new sets of model parameter values and evaluating it using the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm. It then simultaneously constructs the posterior distribution of population hyperparameters given the current estimates of all participants in the same way through iteratively proposing and evaluating potential sets of hyperparameters based on the participant-level estimates. To prevent chains from getting stuck in the local minimas of this high-dimensional parameter space, we further blocked parameter estimation such that each iteration of DE-MCMC sampling comprised five sub-steps. Each iteration first proposed and evaluated parameter values for the value-constants of the three non-neutral emojis, then weights on self-interest, then weights on other-welfare, then weights on inequality, and finally the thresholds for all emojis and the non-decision-time.

We ran 100 chains in parallel for 25,000 samples after a burn-in of 25,000, thinning the samples by a factor of 10. This yielded a total of 250,000 samples to construct the posterior distribution over parameter estimates. We additionally implemented a probabilistic migration step, α = 0.0005, with every MCMC step in place of the differential evolution to improve chain-mixing and convergence towards the high probability density region of the posterior distribution of parameters. The migration step cycles the positions of a subset of chains (Nmigrate uniformly sampled from the total number of chains, i.e. 100) such that the positions of chains {i,i + 1,…j-1, j} were compared against {i + 1, i + 2,…,j, i} and evaluated based on the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm71,74.

Since parameters such as response threshold and non-decision times were theoretically constrained to be positive, we fitted log-transformed parameters that were subsequently exponentiated to obtain the true diffusion model parameter. we assumed that participant-level parameters were normally distributed with respect to a set of hyperparameters: population mean and standard deviations and set priors over the population means to be a random normal distribution, N(0,1), and over the population standard deviations to be a half-cauchy distribution, HC(0,1). To model differences across the three conditions, we initialized two additional sets of hyperparameters. One set of these hyperparameters captured the difference between population means of the Expression and Self-Report condition, while the other set captured any additional differences between the population means of the Reputation and Expression condition. These population-level differences in conditions were similarly assumed to be drawn from a prior normal distribution N(0,1) which instantiates the null hypothesis that computational model parameters do not differ between the Self-Report, Expression, and Reputation conditions. Variances across participants were assumed to be homogenous and thus only a single population standard deviation was estimated across the three conditions.

Statistical inference

All models were assessed to have converged to the posterior distribution based on the Gelman-Rubin statistic for all hyperparameters and participant specific parameters: max(Ř) < 1.0175,76. Statistical results report the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate of the population mean for the parameter of interest, using the 95% high-density interval (HDI) to quantify the uncertainty of the estimate. Here, we note a change to the pre-registered criterion for statistical inference. While we had initially pre-registered statistical significance to be inferred when the 90% HDI does not include zero based on recommendations for computational stability77 and rejection of arbitrary standards imported from frequentist frameworks of null hypothesis significance testing (NHST)78, we revised our criterion to infer statistical significance when the 95% HDI does not include zero. This change reflects the evolution of discourse acknowledging the benefits of aligning with conventional thresholds from NHST to encourage replicability and reproducibility across the literature. We also sincerely and gratefully acknowledge considerable discussion and thoughtful comments from our reviewers in arriving at this change from our preregistered criterion for reporting. Consequently, we interpret statistical results that meet the pre-registered 90% threshold but not the more conservative 95% threshold as having marginal evidentiary support. Furthermore, to complement these categorical significance judgments, we also include the probability of direction (pD)—i.e., the proportion of the posterior distribution that aligns with the direction of the MAP estimate— to quantify the strength of evidence supporting an effect for all statistical tests79,80. For comparisons between parameter estimates of the computational model, we further calculated Cohen’s d effect sizes by taking the differences of interest and normalizing it over the fitted pooled standard deviation hyperparameter of the population, creating a posterior distribution from which we further derived the MAP and 95% HDI.

Software

The experiment was delivered to participants over the internet using Inquisit Web (v6.5.2). Behavioral analyses were conducted in Rstudio v1.4.1717 (R v4.1.2) using the brms package (v2.16.3)68,69 in rstan (v2.21.3)81, where summary statistics of posterior distributions of parameters-of-interest were extracted using the bayestestR package (v0.11.5)79,80. Visualizations in R were generated using the ggplot2 package (v3.5.0)82. Computational model fitting was conducted in Python (v3.6.8) using numpy (v1.15.1)83, pandas (v0.24.2)84, and numba (v0.52.0)85 on the Niagara supercomputer at the SciNet HPC Consortium86,87. Parallelization across compute resources was supported by mpi4py (v3.1.4)88,89. Statistical inference over parameter posteriors of the computational model was conducted in Python (v3.9.18) using numpy (v1.26.4)83, pandas (v2.2.1)84, numba (v0.59.0)85, scipy (v1.12.0)90, and arviz (v0.16.0)91, with visualizations produced by matplotlib (v3.8.0)92 in the Spyder IDE (v5.5.1). Because model-fitting was optimized for high-performance computing on the Niagara supercomputer (5 Nodes x 40 CPUs), a local version of the computational model-fitting procedure and an accompanying demo that uses the programming environment for statistical inference is provided in the openly accessible data and code repository.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

People tend to suppress anger but not sadness

We first sought to demonstrate that participants’ expressive decisions in our paradigm reflect the unique communicative value of emotions by analyzing overall patterns of emoji use between the Self-Report and both expression conditions (Fig. 2 & Table 1). Given past findings showing that people tend to suppress negative emotions, we might expect people to select the angry and sad emojis less frequently in the Expression and Reputation condition15,16,93. Alternatively, if people use emotions to communicate expectations to their partner, they should either veridically express or even exaggerate one or both emotions94. Consistent with the former hypothesis, participants in both the Expression and Reputation conditions selected the anger emoji significantly less frequently than participants in the Self-Report condition (Difference in proportion of angry responses: MAPexp-self = −0.066, 95% HDI = [−0.122, −0.016], pD = 0.996; MAPrep-self = -0.075 [−0.135, −0.036], pD > 0.999). However, consistent with the latter hypothesis, expression groups appeared to select sadness more often compared to the Self-Report group, although this difference was marginal in the Expression only condition (Sad responses: MAPexp-self = 0.036 [−0.005, 0.082], pD = 0.961; MAPrep-self = 0.052 [0.008, 0.112], pD = 0.992). The two expression groups showed similar expressive changes for both emotions (Anger: MAPrep-exp = -0.016 [−0.047, 0.008], pD = 0.912; Sadness: MAPrep-exp = 0.018 [−0.038, 0.077], pD = 0.745).

Each colored shape represents the proportion of trials where a participant chose that emotion response (Red: Anger, Blue: Sadness, Yellow: Happiness, Grey: Neutral) in the Self-Report (circles; N = 84), Expression (triangles; N = 87), and Reputation condition (squares; N = 83). The boxplots represent the maximum a posteriori estimate and 95% HDI of the model-estimated posterior distribution of the population mean *95% HDI of the difference between conditions does not include zero. †90% HDI does not include zero.

Reputational concern uniquely motivated exaggeration of happiness

Although both expression groups exhibited similar differences in their communication of anger and sadness, we did observe one expressive difference that was uniquely sensitive to reputational concerns: the Reputation group chose to express happiness more frequently compared to any other condition (MAPrep-exp = 0.098 [0.004, 0.206], pD = 0.975; MAPrep-self = 0.126 [0.025, 0.236], pD = 0.991; MAPexp-self = 0.029 [-0.076, 0.136], pD = 0.696). This came largely at the expense of fewer neutral expressions in the Reputation group compared to the other groups (MAPrep-exp = -0.101 [-0.167, -0.041], pD = 0.999; MAPrep-self = -0.105 [-0.165, -0.039], pD > 0.999), which did not differ from each other (MAPexp-self = -0.001 [-0.071, 0.070], pD = 0.502).

These results provide strong evidence, using conventional analyses, that people flexibly regulate their emotion expressions in our economic game paradigm. They not only seemed to broadly suppress anger and potentially exaggerate sadness but also responded in a context-sensitive way to salient reputational consequences by expressing more happiness. However, these aggregate-level analyses fail to fully exploit the richness of the paradigm, which allows us to tease apart different explanations for when, why, and how people express, suppress, and exaggerate their emotions. To address this gap, we turned to computational modelling, which provides a much richer description of the different mechanisms underlying expressive regulation.

A sequential sampling model of affective responding

We developed a multi-attribute extension of the Racing Diffusion Model60,95,96 to computationally instantiate our value-based theory (see Methods). Our model makes several key assumptions. First, when choosing which emoji to select, the model assumes that people construct noisy evidence for each of the four response options (i.e., neutral, happiness, sadness, and anger) and accumulate this evidence over time and in parallel until one response option’s evidence surpasses an option-specific threshold, triggering selection of that option. In the case of private self-reported feelings, the strength of evidence for a specific option reflects the degree to which it matches the subjective feelings of the participant (representational value)62,97,98,99. In the case of expressions, we assume that the strength of evidence reflects the sum of both this representational value and the added socio-communicative value of the emoji. Second, the model assumes that these values—representational and socio-communicative—are themselves constructed from a weighted sum of the situational attributes on the current trial (i.e., w$Self × self-outcomes, w$Other × other-outcomes, and w$Ineq × inequality) and a constant, C, that represents a general evaluation of the emoji response option. As an example, the weight translating self-outcomes into evidence for the angry emoji, w$Self:anger, is likely negative since people feel angrier when they receive poorer outcomes. In contrast, the weight on self-outcomes for the happy emoji, w$Self:happiness, is likely positive since people likely feel happy when they receive good outcomes. Importantly, we assume that the evidence constant and weights are not the only factor determining choices in our model. Instead, our model parameterizes four option-unique thresholds, b, whose relative heights capture people’s a priori response biases towards specific options (Fig. 3). A lower threshold for a particular emotion represents a bias toward that emotion that will tend to increase both the frequency and speed with which people select it.

Critically, our model identifies several potential mechanisms for why expressions might deviate on average from private self-reports. First, overall suppression or exaggeration of a particular emotion expression might result from simple changes in the value constant, reflecting canonical hypotheses that expressing a negative emotion like anger incurs a general cost. However, our model also allows a second possibility: overall patterns of suppression or exaggeration might result from people’s a priori or default response biases63,100 against or towards certain expressive options (captured in the expression-specific threshold), effectively constituting a proactive form of regulation101. Lastly, deviation of expression from feeling might be sensitive to specific features of the social interaction. For example, expressing emotions that signal normative preferences for equality, despite not holding those preferences in private, might confer communicative or reputational advantages. In this case, one might selectively express happiness (anger) in the face of inequality-minimizing (maximizing) choice, despite not genuinely feeling such emotions.

To examine the unique influence of these distinct mechanisms and to explore their implications for when, why and what emotions people express, we fit the model to participants’ choices and response times hierarchically using a Bayesian approach and compared differences in parameter values between the Self-Report, Expression, and Reputation conditions. Posterior predictive checks confirmed that the model fit participants’ behavior well (Supplementary Note S4).

Overall communicative costs and benefits to expressing negative emotions

Given both past research26,28, as well as the fact that our behavioral results showed decreased expression of anger, and increased expression of sadness, we hypothesized that value constants for these two emotions should differ between the Expression and Self-Report conditions, but in opposite ways. Consistent with these hypotheses, participants valued the anger emoji less in both the Expression and Reputation conditions compared to the Self-Report condition (mean Canger MAPexp-self = -0.344 [-0.568, -0.137], pD > 0.999, Cohen’s d = -0.520 [-0.836, -0.193]; MAPrep-self = -0.415 [-0.633, -0.202], pD > 0.999, Cohen’s d = -0.609 [-0.941, -0.294]; MAPrep-exp = -0.071 [-0.281, 0.150], pD = 0.728, Cohen’s d = -0.111 [-0.414, 0.222]; partially confirming a pre-registered hypothesis, Supplementary Note S1).

As with overall response frequency, this did not generalize to sadness. Instead, the model seemed to identify a general communicative benefit to expressing sadness, with higher value constants in the Expression and Reputation conditions compared to the Self-Report condition, though this benefit was only marginal for the Reputation condition (mean Csadness MAPexp-self = 0.175 [0.015, 0.367], pD = 0.982, Cohen’s d = 0.337 [0.020, 0.656]; MAPrep-self = 0.151 [-0.021, 0.331], pD = 0.958, Cohen’s d = 0.286 [-0.037, 0.600]; MAPrep-exp = -0.035 [-0.210, 0.146], pD = 0.638, Cohen’s d = -0.064 [-0.382, 0.259]; Table 2).

Reputational concern biases people towards positive expressions

In contrast to negative emotions, where both Expression and Reputation conditions showed equivalent differences when compared to the Self-Report condition, our behavioral results suggested that the Reputation condition uniquely increased the frequency of happy expressions, compared to both the Expression alone, and Self-Report conditions. Given that the suppression of anger and exaggeration of sadness were driven by the active anticipation of their potential costs and benefits, one might expect exaggeration of happy responses under reputational concern to be driven by similar mechanisms. However, we found only limited support for this idea. Although the model suggested that people perceived an overall communicative benefit to expressing happiness in the Reputation condition (mean Chappiness MAP rep-self = 0.155 [0.016, 0.292], pD = 0.986, Cohen’s d = 0.372 [0.040, 0.680]), this did not seem to fully explain the amplification of happy expressions unique to the Reputation condition. We found marginal evidence that Expression alone also increased the value constant of the happy emoji to an equivalent extent as Reputation compared to Self-Report (MAPexp-self = 0.125 [-0.015, 0.260], pD = 0.960, Cohen’s d = 0.287 [-0.036, 0.603]; MAPrep-exp = 0.028 [-0.105, 0.171], pD = 0.678, Cohen’s d = 0.067 [-0.243, 0.396]; partially confirming a pre-registered hypothesis, Supplementary Note S1) suggesting another mechanism at work under reputational concern.

Indeed, our model revealed that the reputation-driven increase in happy expressions resulted from reduced thresholds (mean bhappiness MAPrep-self = -0.209 [-0.318, -0.099], pD > 0.999, Cohen’s d = -0.617 [-0.933, -0.281]; MAPrep-exp = -0.150 [-0.260, -0.042], pD = 0.997, Cohen’s d = -0.437 [-0.765, -0.120], Fig. 4 and Table 3). Whereas participants maintained similar thresholds of evidence for neutral and happy responding in the Self-Report and Expression conditions (mean bhappiness-neutral MAPself = 0.099 [-0.035, 0.231], pD = 0.926; MAPexp = 0.035 [-0.096, 0.167], pD = 0.703), participants in the Reputation condition had a significantly lower threshold for happiness compared to neutral (mean bhappiness-neutral MAPrep = -0.232 [-0.364, -0.100], pD > 0.999). Given that thresholds for happiness and neutral were significantly lower than those for anger and sadness in all conditions (all 95% HDIs < 0, Table 3), this in effect meant that participants in the Reputation condition tended to default towards expressing happiness regardless of how their partner chose to distribute the money in an interaction.

Violin plots indicate the model-estimated posterior distribution over the average log-transformed threshold for each response option in the Self-Report (N = 82), Expression (N = 82), and Reputation (N = 82) conditions. Colors indicate the specific response option (Grey: Neutral, Yellow: Happiness, Red: Anger, Blue: Sadness). The dot, boxplot and whiskers represent the maximum a posteriori estimate, 25th and 75th quantile, and 95% HDI. *95% HDI of the difference between conditions does not include zero.

People avoid communicating preferences for self-interest using anger

Although the foregoing results already suggest important differences in the mechanisms by which people express their emotions, showing that both general costs/benefits and response-biased thresholds emerge in different contexts, our model has an additional advantage. Prior research, as well as the previous analyses in this paper, tends to examine emotion expression in general terms across social contexts. Yet we hypothesized that one way emotion expressions furnish social value is by tracking with specific attributes of the social interaction to communicate preferences that reflect well on their character. For example, if people want to convey their support for social norms, they may selectively suppress or exaggerate emotion expressions in the face of inequality. If they want to convey a generally altruistic stance, they might suppress certain emotion expressions for larger amounts of money for the self or exaggerate them for larger amounts to the other. We tested such hypotheses by examining differences in weights on $Self, $Other, and $Ineq across our conditions.

We first examined how these features shaped evaluations of the angry emoji as an option for self-reported feelings compared to expressions (Fig. 5 and Table 4). Unsurprisingly, participants tended to self-report feeling angry more when their partners chose distributions that led to poorer outcomes for the participant (mean w$Self:anger MAPself = −1.100, [−1.317, −0.876], pD > 0.999) and greater inequality (mean w$Ineq:anger MAPself = 0.975, [0.768, 1.164], pD > 0.999), especially when they also meant worse outcomes for the partner (mean w$Other:anger MAPself = −0.423, [−0.614, −0.211], pD > 0.999). However, participants reduced sensitivity to their own outcomes when expressing anger (mean w$Self:anger MAPexp-self = 0.329 [0.025, 0.649], pD = 0.983, Cohen’s d = 0.351 [0.024, 0.672]; MAPrep-self = 0.439 [0.103, 0.726], pD = 0.995, Cohen’s d = 0.443 [0.108, 0.757]; partially confirming a pre-registered hypothesis, Supplementary Note S1). In fact, for every loss of $1 that increased the value of self-reporting anger, participants were willing to tolerate an additional loss of roughly $0.375 and $0.530 before communicating anger to same extent in the Expression and Reputation condition respectively.

Heatmaps plotting the model-estimated mean value of the anger emoji (color) as a function of participants’ and their partners’ outcomes in the Dictator Game for the Self-Report (Left; N = 82), Expression (Middle; N = 82), and Reputation (Right; N = 82) conditions. Warmer colors indicate more positive response values, and cooler colors indicate more negative response values. The diagonal line on each plot indicate that partners’ choices did not change the inequality of the option. The different maps on the upper and lower row indicate their partners (the Dictator) chose the more unequal option (Upper) or less unequal option (Lower), with greater deviations from the line in the upper row indicating that Dictators chose more unequal options (e.g., $75–$25 compared to $50–$50), and greater deviations from the line in the lower row indicating that Dictators chose more equal options (e.g. $50–$50 compared to $25–$75).

Participants also seemed to moderate their anger expressions in response to the overall inequality of their partner’s choice (mean w$Ineq:anger MAPexp-self = −0.279 [−0.562, −0.001], pD = 0.977, Cohen’s d = −0.314 [−0.637, −0.004]; MAPrep-self = −0.266 [−0.541, 0.020], pD = 0.965, Cohen’s d = −0.302 [−0.611, 0.023]; contrary to a pre-registered hypothesis, Supplementary Note S1), tolerating greater inequality when evaluating the option to express anger compared to self-reporting it, though less robustly so in the Reputation condition where evidentiary support was marginal. We also note that both expression groups deployed these regulatory strategies equally, regardless of reputational consequences (0 ∈ 95% HDIsrep-exp, Table 4). We found no consistent evidence that participants moderated their anger expression based on their partners’ outcomes (0 ∈ 95% HDIs, Table 4).

Importantly, the nuanced regulation of negative emotion expressions compared to self-reported feelings based on specific features of the social interaction appeared unique to anger. Although participants’ self-reported feelings of sadness increased with decreasing payoffs for themselves (mean w$Self:sadmess MAPself = −0.736 [−0.906, −0.568], pD > 0.999) and their partner (mean w$Other:sadness MAPself = −0.274 [−0.395, −0.159], pD > 0.999), and increased with greater inequality (mean w$Ineq:sadness MAPself = 0.818 [0.668, 0.964], pD > 0.999) as expected, we found no evidence that expressions of sadness with or without reputational costs altered these basic patterns (0 ∈ all 95% HDIs, Table 4). Thus, while participants appeared to deliberately suppress their anger expressions to avoid signaling preferences for self-interest and—to a lesser extent—equality, there was no evidence they regulated communication of these preferences through expressions of sadness.

Reputational concern drives positive communication of normative preferences for equality

Complementing participants’ selective suppression of angry expressions as a negative signal of their preferences, we found that participants regulated their expressions of happiness even more strongly based on the inequality of the social interaction, and that reputational concern further exacerbated these patterns of expressive communication (Fig. 6 and Table 4). In particular, we found that participants in the Self-Report condition grew increasingly likely to self-report feeling happy as outcomes for themselves improved (mean w$Self:happiness MAPself = 1.623 [1.411, 1.857], pD > 0.999), as outcomes for their partners worsened (mean w$Other:happiness MAPself = −0.303 [−0.442, −0.163], pD > 0.999), and, somewhat surprisingly, as inequality grew (i.e., indicating a positive preference for inequality; mean w$Ineq:happiness MAPself = 0.312 [0.102, 0.502], pD = 0.998). Importantly, however, this contrasted with participants in the Expression condition, whose happy expressions were relatively insensitive to inequality (mean w$Ineq:happiness MAPexp = −0.011 [−0.203, 0.198], pD = 0.515; MAPexp-self = −0.309 [−0.581, −0.016], pD = 0.983, Cohen’s d = −0.320 [−0.655, −0.021]). More strikingly, when reputational consequences were made salient, participants in the Reputation condition further shifted their happy expressions to communicate more normative preferences (i.e., an aversion) against inequality rather than a preference for or indifference (mean w$Ineq:happiness MAPrep = −0.337 [−0.543, −0.146], pD > 0.999; MAPrep-self = −0.647 [−0.928, −0.364], pD > 0.999, Cohen’s d = −0.735 [−1.042, −0.398]; MAPrep-exp = −0.331 [−0.620, −0.057], pD = 0.991, Cohen’s d = −0.379 [−0.700, −0.066]; confirming a pre-registered hypothesis, Supplementary Note S1). Self- and partner-outcomes were similarly associated with self-reported feelings and expressions across all conditions (0 ∈ all 95% HDIs of differences between conditions, Table 4). In other words, by selectively suppressing the happiness they might have felt as inequality increased and exaggerating/faking expressions of unfelt happiness as inequality was reduced, participants seemed to signal normative preferences for equality when their reputation was at stake that were completely divorced from their privately held preferences.

Heatmaps plotting the model-estimated mean value of the happy emoji (color) as a function of participants’ and their partners’ outcomes in the Dictator Game for the Self-Report (Left; N = 82), Expression (Middle; N = 82), and Reputation (Right; N = 82) conditions. Warmer colors indicate more positive response values, and cooler colors indicate more negative response values. The diagonal line on each plot indicate that partners’ choices did not change the inequality of the option. The different maps on the upper and lower row indicate their partners (the Dictator) chose the more unequal option (Upper) or less unequal option (Lower), with greater deviations from the line in the upper row indicating that Dictators chose more unequal options (e.g., $75–$25 compared to $50–$50), and greater deviations from the line in the lower row indicating that Dictators chose more equal options (e.g. $50–$50 compared to $25–$75).

Discussion

From facilitating affiliative relationships to deterring antagonistic behaviors, emotion expressions serve as fundamental signals that underpin our ability to communicate and coordinate with others1,3. Yet an extensive body of research suggests that people do not always veridically express how they feel, sometimes suppressing13,14,15,16,17,18,19,39,42,102, and sometimes exaggerating or faking specific emotions20,21,22,23. However, despite decades of work, it remains unclear how, when, and why people express, suppress, or exaggerate their emotions. To bridge this gap, we developed a value-based computational model that views emotion expressions as communicative decisions, allowing us to leverage the substantial literature on computational mechanisms of decision-making61,73,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122. In so doing, we demonstrated how such a model not only seamlessly accounts for a wide array of expressive behavior during a dyadic social interaction (including expression, suppression, and exaggeration) but also yields insights into the specific computational mechanisms underlying expressive communication.

Corroborating longstanding theories of expressive suppression39,102,123, we found that people tended to suppress expressions of anger, and that this suppression derives in part from the estimation of a cost to expressing this emotion. However, these costs did not apply uniformly to other negative emotions. People appeared to exaggerate expressions of sadness in anticipation of potential socio-communicative benefits, complementing existing research suggesting that sadness or disappointment may be particularly effective at eliciting sympathetic reactions that circumvent costly retaliation following expressions of anger124,125,126,127,128. Additionally, confirming our theoretical predictions, we found that people were keenly sensitive to relevant features of the social environment when evaluating whether and what emotion they ought to express. At a broader level, making salient the reputational consequences of expression (by highlighting that partners would share their perception of participants with others) disproportionately biased people to exaggerate happy expressions. Importantly, and in contrast to regulation of anger and sadness, this exaggeration seemed to result not from changes in its overall communicative value, but through a response-related bias that reduced the amount of evidence required to trigger a happy expression. Such a pre-emptive strategy might represent an effort to leverage the affiliative benefits of positive expressions which have been shown to generate reciprocal prosociality and buffer against potential disrepute from negative impressions55,129,130.

Crucially, our results demonstrate people’s remarkably nuanced flexibility in regulating their emotion expressions. Our computational approach allowed us to rigorously characterize and quantify how exactly people selectively expressed, suppressed, and exaggerated specific emotions based on features of the immediate social interaction, which we propose may be designed to control the social preferences that they communicated to their partners. For example, people seemed to selectively suppress anger to temper its use as a communicative signal of self-interest and outrage at inequality, potentially to project agreeableness and greater tolerance for these undesired outcomes. People also selectively suppressed and exaggerated their expressions of happiness in different contexts based on the fairness of their partner’s choice. More concretely, although they appeared to anticipate general benefits to expressing happiness, these benefits were specific to expressions of happiness towards norm-abiding behavior from their partners. When their partners violated those norms (even to the participant’s own benefit), they perceived a cost to expressing happiness. Reputational concern further exacerbated these socio-communicative benefits and costs, fully switching the effect of inequality from positive in self-reported feelings of happiness (indicating that participants liked it) to negative (as if they disliked it) when expressing to partners who could effectively gossip131,132,133,134 about them to others.

Our results join existing work suggesting that a primary function of emotions, and socio-moral emotions in particular, is to serve as communicative signals of norm-conformity, perhaps as a way of incentivizing prosocial behaviors from others towards the self in an interpersonal interaction24,58,135,136. Intriguingly, despite much of this work focusing on negative socio-moral emotions like anger or outrage30,31,32,33,34,36, our results demonstrate how people might selectively leverage expressions of positive emotions to communicate normative preferences in certain contexts. This then raises the question of how people balance the use of positive and negative emotion expressions to signal norm-conformity. Here, future work might consider how intended observers of expressions might be a critical determinant of people’s expressive patterns. In our paradigm, participants expressed their emotions in a fully dyadic interaction where the only observer of the expression is the same social partner whose actions elicited the emotion in the first place. The persistently asymmetrical social dynamics produced when participants’ partners unilaterally controlled the outcomes for everyone, may have in effect restricted impression management, such that suppression of anger and exaggeration of happiness became the sole way to regulate their partner’s behaviors137. Yet the communicative utility of emotion expressions like anger and happiness may differ substantially when signaling to third-party observers who possess the resources to intervene on one’s behalf58,138,139,140,141,142. In such cases, one might observe benefits to exaggerating anger, rather than happiness, in response to inequality. Such an observation could shed light on why negative emotional content spreads virulently across online social networks (where the benefit of expressing anger to millions of third-party observers may outweigh any costs of expressing anger towards a single actor)30,143. Understanding these dynamics through a computational and value-based lens might also reveal insights into interventions that could effectively moderate expressions of emotion in both the public and private domains32,33,34.

Yet, such insights could only be gleaned from approaches like the value-based framework and computational model we have developed here, that (1) consider how a significant source of emotion expression’s socio-communicative value derive from its emergent pattern of use across multiple different social interactions and (2) disentangle it from other potential mechanisms that shape expressive decision-making. Specifically, that people’s expressions are simultaneously driven by different mechanisms in similar social interactions for the same emotion suggests the utility of exploring how these processes play out in real-world interactions. Apart from driving people to communicate normative preferences for equality using positive expressions, our results also show that reputational concern biases people towards expressing happiness by default in these economic games which increases not only the frequency but also the speed of these expressions. Although these positive expressions might aim to communicate agreeableness, some recent work suggests that happy expressions which emerge too quickly might be perceived to be deliberate and disingenuous144, which could backfire on expressers. Whether, and when, certain communicative strategies are more adaptive than others remain an open question for future work.

Importantly, differentiating between mechanisms that produce patterns of expressive behavior that are similar at first blush could illuminate unique associations with social and psychological (dys)function13,14,15,16,17,18,19,39,42,102. For example, suppression of negative expressions due to overall perceptions of outsized costs (i.e. negative value constants) might be indicative of negative rumination associated with social anxiety and depression, while broad perceptions of expression as beneficial (i.e. positive value constants) might be indicative of an indifference to the negative effects of one’s expression on others characteristic of borderline, antisocial or narcissistic personality types145. Alternatively, indiscriminately lowered thresholds for emotion expressions might track individuals’ levels of impulsivity146. Additionally, examining how these persistent patterns of expressions trade-off against more nuanced communicative strategies aimed at signaling intentions and preferences over multiple interactions could further shed light into how they impair social functioning. By consistently suppressing one’s emotions or constantly plastering a smile on one’s face, expressions become an impoverished signal for others to accurately infer our goals and preferences147. Indeed, we suspect that the capacity to flexibly suppress and exaggerate one’s emotion expressions based on cues in our social environment confers the greatest utility for adaptive communication137,148,149,150. A model capable of quantifying these nuanced differences in expressive communication might thus facilitate the development of personalized interventions to improve interpersonal outcomes for a wide spectrum of clinical disorders impacting social behavior.

Limitations

While we believe our work here lays the foundation for future research to take up these important questions, we also acknowledge that it has some limitations. First, participants in our study were only allowed to select one out of a limited set of four emojis to self-report and express how they felt. Although emojis represent an ecologically valid mode of emotion expression151,152, these restrictions in how many and which emojis participants could use likely constrained our ability to capture more nuanced aspects of both participants’ subjective feelings and communicative behaviors. Moreover, emotion expressions in the real-world are conveyed across multiple different modalities. At the same time, our paradigm relies on deception to elicit participants’ socio-affective responses in asynchronous economic games with algorithmic partners. In the current study, these limiting design choices were necessary to rigorously test our proposed value-based computational model but may have constrained the emergence of unique communicative dynamics inherent to synchronous interactions153. Thus, additional work is required to extend our findings across modes of expressive behavior and social interactions.

We expect that doing so would not only require more precise measures of subjective feelings and spontaneous expressions in more naturalistic social interactions, but also more sophisticated extensions of the value-based computational model we have proposed here. As an example, research has found that facial movements are not always fully volitional and that micro-expressions may sometimes betray people’s deliberate attempts to conceal their true emotion states154,155,156,157,158. One extension of our computational model might consider how facial action units (FAUs) physiologically instantiate evidence accumulators. While these accumulators may share common sources of evidence, each may be more or less amenable to deliberate regulation based on the communicative goals of the expresser. A computational model that considers the influence of different kinds of evidence on different FAUs might help to go beyond simple categorical approaches to emotion expressions and reveal subtler communication subserved by more flexible combinations of facial movements. By comparing the evidence considered by these expressive action units and those considered when making subjective self-reports, researchers could then further understand not only the psychological processes that underlie expressive regulation but also its biophysical constraints. Future models capable of capturing such dynamics would not only extend our current understanding of expressive regulation to a new modality but also reveal deeper insight into both the processes through which facial expressions are generated and the psychological dynamics of real-time social exchanges in face-to-face interaction.

Data availability

The experimental data that support the findings of this study are available on OSF at https://osf.io/hg3ft/.

Code availability

The experimental code used to collect the data for this study and all computer code generated for the computational models and analyses are available on OSF at https://osf.io/hg3ft/.

References

Van Kleef, G. A. How emotions regulate social life: The emotions as social information (EASI) model. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 18, 184–188 (2009).

van Kleef, G. A., Cheshin, A., Fischer, A. H. & Schneider, I. K. Editorial: The Social Nature of Emotions. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00896 (2016).

Van Kleef, G. A. & Côté, S. The social effects of emotions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 73, 629–658 (2022).

Ekman, P. Expression and the Nature of Emotion. in Approaches to Emotion (eds Scherer, K. R. & Ekman, P.) 319–344 (Psychology Press, 1984).

Horstmann, G. What do facial expressions convey: Feeling states, behavioral intentions, or actions requests?. Emotion 3, 150 (2003).

Izard, C. E. Innate and universal facial expressions: Evidence from developmental and cross-cultural research. Psychol. Bull. 115, 288–299 (1994).

Clark, M. S. & Taraban, C. Reactions to and willingness to express emotion in communal and exchange relationships. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 27, 324–336 (1991).

Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. & Manstead, A. S. The interpersonal effects of emotions in negotiations: a motivated information processing approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87, 510 (2004).

Van Kleef, G. A., Van den Berg, H. & Heerdink, M. W. The persuasive power of emotions: Effects of emotional expressions on attitude formation and change. J. Appl. Psychol. 100, 1124 (2015).

Hareli, S. & Hess, U. The social signal value of emotions. Cogn. Emot. 26, 385–389 (2012).

Fridlund, A. J. Evolution and facial action in reflex, social motive, and paralanguage. Biol. Psychol. 32, 3–100 (1991).

Crivelli, C. & Fridlund, A. J. Facial Displays Are Tools for Social Influence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 388–399 (2018).

Butler, E. A. & Gross, J. J. Hiding Feelings in Social Contexts; Out of Sight Is Not Out of Mind. in The Regulation of Emotion (eds Philippot, P. & Feldman, R. S.) 103–128 (Psychology Press, 2004).

Gross, J. J. Antecedent-and response-focused emotion regulation: divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 224 (1998).

Gross, J. J., John, O. P. & Richards, J. M. The dissociation of emotion expression from emotion experience: a personality perspective. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 26, 712–726 (2000).

Gross, J. J. & John, O. P. Facets of emotional Expressivity: Three self-report factors and their correlates. Personal. Individ. Differ. 19, 555–568 (1995).

Gross, J. J. & John, O. P. Revealing feelings: Facets of emotional expressivity in self-reports, peer ratings, and behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72, 435–448 (1997).

Gross, J. J. & John, O. P. Mapping the domain of expressivity: Multimethod evidence for a hierarchical model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 170–191 (1998).

Gross, J. J. & John, O. P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 348 (2003).

Andrade, E. B. & Ho, T.-H. Gaming emotions in social interactions. J. Consum. Res. 36, 539–552 (2009).

Côté, S., Hideg, I. & Van Kleef, G. A. The consequences of faking anger in negotiations. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49, 453–463 (2013).

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V. & O’Sullivan, M. Smiles when lying. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54, 414–420 (1988).

Mann, S. Emotion at work: to what extent are we expressing, suppressing, or faking it?. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 8, 347–369 (1999).

Fischer, A. H., Manstead, A. S. R., Evers, C., Timmers, M. & Valk, G. Motives and Norms Underlying Emotion Regulation. in The Regulation of Emotion (eds Philippot, P. & Feldman, R. S.) 189–212 (Psychology Press, 2004).

Kalokerinos, E. K., Greenaway, K. H., Pedder, D. J. & Margetts, E. A. Don’t grin when you win: The social costs of positive emotion expression in performance situations. Emotion 14, 180 (2014).

Le, B. M. & Impett, E. A. When holding back helps: Suppressing negative emotions during sacrifice feels authentic and is beneficial for highly interdependent people. Psychol. Sci. 24, 1809–1815 (2013).

Schall, M., Martiny, S. E., Goetz, T. & Hall, N. C. Smiling on the inside: The social benefits of suppressing positive emotions in outperformance situations. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 42, 559–571 (2016).

Wang, L., Northcraft, G. B. & Van Kleef, G. A. Beyond negotiated outcomes: The hidden costs of anger expression in dyadic negotiation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 119, 54–63 (2012).

Wei, M., Su, J. C., Carrera, S., Lin, S.-P. & Yi, F. Suppression and interpersonal harmony: a cross-cultural comparison between Chinese and European Americans. J. Couns. Psychol. 60, 625 (2013).

Brady, W. J., Wills, J. A., Jost, J. T., Tucker, J. A. & Van Bavel, J. J. Emotion shapes the diffusion of moralized content in social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 7313–7318 (2017).

Brady, W. J., Crockett, M. & Van Bavel, J. J. The MAD Model of Moral Contagion: The role of motivation, attention and design in the spread of moralized content online. (2019).

Brady, W. J., McLoughlin, K., Doan, T. N. & Crockett, M. J. How social learning amplifies moral outrage expression in online social networks. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe5641 (2021).

Brady, W. J. et al. Overperception of moral outrage in online social networks inflates beliefs about intergroup hostility. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 917–927 (2023).

Brady, W. J. & Crockett, M. J. How effective is online outrage?. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 79–80 (2019).

Kring, A. M. & Elis, O. Emotion Deficits in People with Schizophrenia. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 409–433 (2013).

McLoughlin, K. L. & Brady, W. J. Human-algorithm interactions help explain the spread of misinformation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 56, 101770 (2024).

Perez, J. E., Riggio, R. E. & Kopelowicz, A. Social skill imbalances in mood disorders and schizophrenia. Personal. Individ. Differ. 42, 27–36 (2007).

Wagner, H. & Lee, V. Alexithymia and individual differences in emotional expression. J. Res. Personal. 42, 83–95 (2008).

Butler, E. A. et al. The social consequences of expressive suppression. Emotion 3, 48 (2003).

Butler, E. A., Lee, T. L. & Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific?. Emotion 7, 30–48 (2007).

Richards, J. M. & Gross, J. J. Composure at any cost? The cognitive consequences of emotion suppression. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 25, 1033–1044 (1999).

Srivastava, S., Tamir, M., McGonigal, K. M., John, O. P. & Gross, J. J. The social costs of emotional suppression: A prospective study of the transition to college. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 96, 883 (2009).

Cameron, L. D. & Overall, N. C. Suppression and expression as distinct emotion-regulation processes in daily interactions: Longitudinal and meta-analyses. Emotion 18, 465 (2018).

Van Kleef, G. A., De Dreu, C. K. W. & Manstead, A. S. R. The interpersonal effects of anger and happiness in negotiations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 86, 57–76 (2004).

Etkin, A., Büchel, C. & Gross, J. J. The neural bases of emotion regulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 693–700 (2015).

Tamir, M., Bigman, Y. E., Rhodes, E., Salerno, J. & Schreier, J. An expectancy-value model of emotion regulation: Implications for motivation, emotional experience, and decision making. Emotion 15, 90–103 (2015).

Sheppes, G. et al. Emotion regulation choice: a conceptual framework and supporting evidence. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 143, 163 (2014).

Van Kleef, G. A. The emerging view of emotion as social information. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 4, 331–343 (2010).

Johnson, E. J., Häubl, G. & Keinan, A. Aspects of endowment: a query theory of value construction. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 33, 461–474 (2007).

Rangel, A., Camerer, C. & Montague, P. R. A framework for studying the neurobiology of value-based decision making. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 545–556 (2008).

Slovic, P. The construction of preference. Am. Psychol. 50, 364 (1995).

van Kleef, G. A. & Lange, J. How hierarchy shapes our emotional lives: effects of power and status on emotional experience, expression, and responsiveness. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 33, 148–153 (2020).

Hecht, M. A. & LaFrance, M. License or obligation to smile: the effect of power and sex on amount and type of smiling. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 24, 1332–1342 (1998).

Keltner, D., Sauter, D., Tracy, J. & Cowen, A. Emotional expression: advances in basic emotion theory. J. Nonverbal Behav. 43, 133–160 (2019).

Martin, J., Rychlowska, M., Wood, A. & Niedenthal, P. Smiles as multipurpose social signals. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 864–877 (2017).

Hareli, S. & David, S. The effect of reactive emotions expressed in response to another’s anger on inferences of social power. Emotion 17, 717 (2017).

Hareli, S. & Hess, U. What emotional reactions can tell us about the nature of others: An appraisal perspective on person perception. Cogn. Emot. 24, 128–140 (2010).

Hareli, S., Moran-Amir, O., David, S. & Hess, U. Emotions as signals of normative conduct. Cogn. Emot. 27, 1395–1404 (2013).

Gershman, S. J., Norman, K. A. & Niv, Y. Discovering latent causes in reinforcement learning. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 5, 43–50 (2015).

Tillman, G., Van Zandt, T. & Logan, G. D. Sequential sampling models without random between-trial variability: the racing diffusion model of speeded decision making. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 27, 911–936 (2020).

Forstmann, B. U., Ratcliff, R. & Wagenmakers, E.-J. Sequential sampling models in cognitive neuroscience: Advantages, applications, and extensions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67, 641–666 (2016).

Teoh, Y. Y., Cunningham, W. A. & Hutcherson, C. A. Framing Subjective Emotion Reports as Dynamic Affective Decisions. Affect. Sci. 4, 522–528 (2023).

Leite, F. P. & Ratcliff, R. What cognitive processes drive response biases? A diffusion model analysis. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 6, 651–687 (2011).

Engel, C. Dictator games: A meta study. Exp. Econ. 14, 583–610 (2011).

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L. & Thaler, R. H. Fairness and the Assumptions of Economics. J. Bus. 59, S285–S300 (1986).

Nook, E. C., Satpute, A. B. & Ochsner, K. N. Emotion naming impedes both cognitive reappraisal and mindful acceptance strategies of emotion regulation. Affect. Sci. 2, 187–198 (2021).

Torre, J. B. & Lieberman, M. D. Putting feelings into words: affect labeling as implicit emotion regulation. Emot. Rev. 10, 116–124 (2018).

Bürkner, P.-C. brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 80, 1–28 (2017).

Bürkner, P.-C. Advanced Bayesian multilevel modeling with the R package brms. R J. 10, 395–411 (2017).

Leys, C., Ley, C., Klein, O., Bernard, P. & Licata, L. Detecting outliers: Do not use standard deviation around the mean, use absolute deviation around the median. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49, 764–766 (2013).

Turner, B. M., Sederberg, P. B., Brown, S. D. & Steyvers, M. A method for efficiently sampling from distributions with correlated dimensions. Psychol. Methods 18, 368 (2013).

Holmes, W. R. & Trueblood, J. S. Bayesian analysis of the piecewise diffusion decision model. Behav. Res. Methods 50, 730–743 (2018).

Roberts, I. D., HajiHosseini, A. & Hutcherson, C. A. How bad becomes good: A neurocomputational model of affect-informed choice. Emotion 24, 1737–1752 (2024).

Hu, B. & Tsui, K.-W. Distributed evolutionary Monte Carlo for bayesian computing. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 54, 688–697 (2010).

Brooks, S. P. & Gelman, A. General methods for monitoring convergence of iterative simulations. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 7, 434–455 (1998).

Gelman, A. & Rubin, D. B. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Stat. Sci. 7, 457–472 (1992).

Kruschke, J. Doing Bayesian data analysis: A tutorial with R, JAGS, and Stan. (2014).

McElreath, R. Statistical rethinking: A Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan. (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018).

Makowski, D., Ben-Shachar, M. S., Chen, S. H. A. & Lüdecke, D. Indices of Effect Existence and Significance in the Bayesian Framework. Front. Psychol. 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02767 (2019).

Makowski, D., Ben-Shachar, M. S. & Lüdecke, D. bayestestR: Describing effects and their uncertainty, existence and significance within the Bayesian framework. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1541 (2019).

Stan Development Team. RStan: the R interface to Stan. (2021).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (Springer-Verlag New York, 2009).

Harris et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

The pandas development team. pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas. (2020) https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3509134.

Lam, S. K., Pitrou, A. & Seibert, S. Numba: a LLVM-based Python JIT compiler. in Proceedings of the Second Workshop on the LLVM Compiler Infrastructure in HPC 1–6 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1145/2833157.2833162.

Loken, C. et al. SciNet: lessons learned from building a power-efficient top-20 system and data centre. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 256, 12026 (2010).

Ponce, M. et al. Deploying a Top-100 Supercomputer for Large Parallel Workloads: The Niagara Supercomputer. in Proceedings of the Practice and Experience in Advanced Research Computing on Rise of the Machines (Learning) (Association for Computing Machinery, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3332186.3332195.

Dalcin, L. & Fang, Y.-L. L. mpi4py: Status Update After 12 Years of Development. Comput. Sci. Eng. 23, 47–54 (2021).

Dalcín, L., Paz, R. & Storti, M. MPI for Python. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 65, 1108–1115 (2005).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Kumar, R., Carroll, C., Hartikainen, A. & Martin, O. ArviZ a unified library for exploratory analysis of Bayesian models in Python. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1143 (2019).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007).

Nezlek, J. B. & Kuppens, P. Regulating positive and negative emotions in daily life. J. Pers. 76, 561–580 (2008).

Xiao, E. & Houser, D. Emotion expression in human punishment behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 7398–7401 (2005).

Osth, A. F. & Farrell, S. Using response time distributions and race models to characterize primacy and recency effects in free recall initiation. Psychol. Rev. 126, 578–609 (2019).

Logan, G. D., Van Zandt, T., Verbruggen, F. & Wagenmakers, E.-J. On the ability to inhibit thought and action: general and special theories of an act of control. Psychol. Rev. 121, 66 (2014).

Givon, E., Itzhak-Raz, A., Karmon-Presser, A., Danieli, G. & Meiran, N. How does the emotional experience evolve? Feeling generation as evidence accumulation. Emotion 20, 271–285 (2020).

Givon, E. et al. Can feelings “feel” wrong? similarities between counter-normative emotion reports and perceptual errors. Psychol. Sci. 33, 948–956 (2022).

Givon, E. et al. Are women truly “more emotional” than men? Sex differences in an indirect model-based measure of emotional feelings. Curr. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04227-z (2023).

Forstmann, B. U., Brown, S., Dutilh, G., Neumann, J. & Wagenmakers, E.-J. The neural substrate of prior information in perceptual decision making: a model-based analysis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 4, 40 (2010).

Braver, T. S. The variable nature of cognitive control: A dual-mechanisms framework. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16, 106–113 (2012).

Gross, J. J. & Levenson, R. W. Emotional suppression: physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 64, 970 (1993).

Bogacz, R., Brown, E., Moehlis, J., Holmes, P. & Cohen, J. D. The physics of optimal decision making: A formal analysis of models of performance in two-alternative forced-choice tasks. Psychol. Rev. 113, 700–765 (2006).