Abstract

Flood research often emphasizes local, direct damages and treats cities as isolated, overlooking development heterogeneity and cascading supply-chain effects. Here we address this gap by coupling flood hazards with a risk-extended multiregional input–output model for 306 Chinese cities across 6 return periods. We quantify direct losses and trace indirect propagation, separating local-indirect losses in the flooded city from ripple losses elsewhere and introduce a spillover indicator for passive losses in nonflooded cities. Losses rise nonlinearly with severity, shifting from direct capital losses in frequent, low-intensity events to local-indirect losses in rare, high-intensity events. Spatial disparities emerge: wealthier cities incur larger absolute but lower loss-to-GDP impacts, whereas poorer cities face higher proportional losses, especially via labor. Spillovers concentrate in major hubs, amplifying systemic risk. Aggregating city stress tests yields conservative lower bounds; a Yangtze River Delta coshock shows strong amplification. Findings motivate sector- and region-specific adaptation and recovery planning.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data utilized in this study were collected from the following sources. The flood hazard map with water depth was derived from the Joint Research Centre of Europe Commission (https://data.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset/jrc-floods-floodmapgl_rp100y-tif). Urban land-use data, including detailed land-use type information, were obtained from the EULUC-China dataset, available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16794007 (ref. 67). The population dataset is from WorldPop (https://www.worldpop.org). The China city-level MRIO table is from CEADs (https://www.ceads.net.cn/). Elevation data were provided by the GEBCO Compilation Group (https://www.gebco.net/data-products/gridded-bathymetry-data). The datasets for building the road network and the river system data were extracted from OpenStreetMaps (https://www.openstreetmap.org/). The monthly precipitation dataset was provided by the National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center, available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3114194 (ref. 68). The three-dimensional building footprint dataset is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11397015 (ref. 69). We collected economic data, drainage pipeline data and built-up green space data for each city from government documents and reports.

References

Coumou, D. & Rahmstorf, S. A decade of weather extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 491–496 (2012).

Rentschler, J. et al. Global evidence of rapid urban growth in flood zones since 1985. Nature 622, 87–92 (2023).

Kotz, M., Levermann, A. & Wenz, L. The effect of rainfall changes on economic production. Nature 601, 223–227 (2022).

Ban, J., Sutton, C., Ma, Y., Lin, C. & Chen, K. Association of flooding exposure with cause-specific mortality in North Carolina, United States. Nat. Water 1, 1027–1034 (2023).

Raju, E., Boyd, E. & Otto, F. Stop blaming the climate for disasters. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 1 (2022).

Rajput, A. A., Liu, C., Liu, Z. & Mostafavi, A. Human-centric characterization of life activity flood exposure shifts focus from places to people. Nat. Cities 1, 264–274 (2024).

Gao, P. et al. Author Correction: Heterogeneous pressure on croplands from land-based strategies to meet the 1.5 °C target. Nat. Clim. Change 15, 682–682 (2025).

Costa, R., Bolte, E., Sharp, C. & Bowers, C. Repeated and localized flooding is an underestimated challenge for urban disaster risk management. Nat. Cities 1, 587–596 (2024).

Kephart, J. L. et al. Social disparities in neighborhood flood exposure in 44,698 urban neighborhoods in Latin America. Nat. Cities 2, 246–253 (2025).

Dottori, F. et al. Increased human and economic losses from river flooding with anthropogenic warming. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 781–786 (2018).

Wang, W., Yang, S., Stanley, H. E. & Gao, J. Local floods induce large-scale abrupt failures of road networks. Nat. Commun. 10, 2114 (2019).

Tian, Z. et al. Dynamic adaptive engineering pathways for mitigating flood risks in Shanghai with regret theory. Nat. Water 1, 198–208 (2023).

Kotz, M., Levermann, A. & Wenz, L. The economic commitment of climate change. Nature 628, 551–557 (2024).

Willner, S. N., Otto, C. & Levermann, A. Global economic response to river floods. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 594–598 (2018).

Rentschler, J., Salhab, M. & Jafino, B. A. Flood exposure and poverty in 188 countries. Nat. Commun. 13, 3527 (2022).

Smiley, K. T. et al. Social inequalities in climate change-attributed impacts of Hurricane Harvey. Nat. Commun. 13, 3418 (2022).

Palagi, E., Coronese, M., Lamperti, F. & Roventini, A. Climate change and the nonlinear impact of precipitation anomalies on income inequality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2203595119 (2022).

Botzen, W. J. W., Deschenes, O. & Sanders, M. The economic impacts of natural disasters: a review of models and empirical studies. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 13, 167–188 (2019).

Ward, P. J. et al. A global framework for future costs and benefits of river-flood protection in urban areas. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 642–646 (2017).

Aerts, J. C. J. H. et al. Integrating human behaviour dynamics into flood disaster risk assessment. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 193–199 (2018).

Haer, T., Botzen, W. J. W., de Moel, H. & Aerts, J. C. J. H. Integrating household risk mitigation behavior in flood risk analysis: an agent-based model approach. Risk Anal. 37, 1977–1992 (2017).

Hallegatte, S. An adaptive regional input–output model and its application to the assessment of the economic cost of Katrina. Risk Anal. 28, 779–799 (2008).

Carrera, L., Standardi, G., Bosello, F. & Mysiak, J. Assessing direct and indirect economic impacts of a flood event through the integration of spatial and computable general equilibrium modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 63, 109–122 (2015).

Koks, E. E. et al. The macroeconomic impacts of future river flooding in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 084042 (2019).

Hirabayashi, Y. et al. Global flood risk under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 816–821 (2013).

Chen, W. et al. Integrated urban flood vulnerability assessment using local spatial dependence-based probabilistic approach. J. Hydrol. 575, 454–469 (2019).

Jiao, S. S., Li, W. J. & Wen, J. H. Spatiotemporal changes of manufacturing firms in the flood prone Yangtze Delta. Environ. Hazards Hum. Policy Dim. 21, 334–360 (2022).

Marin, G., Modica, M., Paleari, S. & Zoboli, R. Assessing disaster risk by integrating natural and socio-economic dimensions: a decision-support tool. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 77, 101032 (2021).

Mendoza-Tinoco, D., Guan, D., Zeng, Z., Xia, Y. & Serrano, A. Flood footprint of the 2007 floods in the UK: the case of the Yorkshire and The Humber region. J. Clean. Prod. 168, 655–667 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Economic ripple effects of individual disasters and disaster clusters. Int. J. Disast. Risk Sci. 13, 948–961 (2022).

León, J. A., Ordaz, M., Haddad, E. & Araújo, I. F. Risk caused by the propagation of earthquake losses through the economy. Nat. Commun. 13, 2908 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Economic footprint of California wildfires in 2018. Nat. Sustain. 4, 252–260 (2021).

Huizinga, J., De Moel, H. & Szewczyk, W. Global Flood Depth–Damage Functions: Methodology and the Database with Guidelines (Joint Research Centre, 2017).

Jin, X. Y., Fang, D. L., Chen, B. & Wang, H. Multiobjective layout optimization for low impact development considering its ecosystem services. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 209, 2986 (2024).

He, Y., Yang, Y. & Wang, S. Network and mechanism of China’s new energy vehicle industry from the perspective of value chain. J. Geogr. Sci. 34, 779–803 (2024).

Development Index Report on China’s Aviation Logistics Hubs (Social Sciences Academic Press, 2024).

Zhang, X., Lu, J. & Peng, Y. Hybrid MCDM model for location of logistics hub: a case in China under the Belt and Road Initiative. IEEE Access 9, 41227–41245 (2021).

Zhao, L. et al. Optimizing logistics hub selection in the integrated network of the China–Europe Railway Express and New International Land-Sea Trade Corridor. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 21, 4384–4411 (2025).

La Rosa, D. & Pappalardo, V. Planning for spatial equity—a performance based approach for sustainable urban drainage systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 53, 101885 (2020).

Brillinger, M., Scheuer, S. & Albert, C. Deliberating options for nature-based river development: insights from a participatory multi-criteria evaluation. J. Environ. Manag. 317, 115350 (2022).

Landry, C. E., Turner, D. & Petrolia, D. Flood insurance market penetration and expectations of disaster assistance. Environ. Resour. Econ. 79, 357–386 (2021).

Bradt, J. T., Kousky, C. & Wing, O. E. J. Voluntary purchases and adverse selection in the market for flood insurance. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 110, 102515 (2021).

Vitale, C., Meijerink, S. & Moccia, F. D. Urban flood resilience, a multi-level institutional analysis of planning practices in the Metropolitan City of Naples. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 66, 813–835 (2023).

Tellman, B. et al. Satellite imaging reveals increased proportion of population exposed to floods. Nature 596, 80–86 (2021).

Wu, X., Zhou, L., Gao, G., Guo, J. & Ji, Z. Urban flood depth-economic loss curves and their amendment based on resilience: evidence from Lizhong Town in Lixia River and Houbai Town in Jurong River of China. Nat. Hazards 82, 1981–2000 (2016).

Tanoue, M. et al. Estimation of direct and indirect economic losses caused by a flood with long-lasting inundation: application to the 2011 Thailand flood. Water Resour. Res. 56, 120068 (2020).

Wu, Z., Lv, H., Meng, Y., Guan, X. & Zang, Y. The determination of flood damage curve in areas lacking disaster data based on the optimization principle of variation coefficient and beta distribution. Sci. Total Environ. 750, 142277 (2021).

Koks, E. E., Bočkarjova, M., de Moel, H. & Aerts, J. C. J. H. Integrated direct and indirect flood risk modeling: development and sensitivity analysis. Risk Anal. 35, 882–900 (2015).

Jongman, B. et al. Declining vulnerability to river floods and the global benefits of adaptation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E2271–E2280 (2015).

Jonkman, S. N., Bočkarjova, M., Kok, M. & Bernardini, P. Integrated hydrodynamic and economic modelling of flood damage in the Netherlands. Ecol. Econ. 66, 77–90 (2008).

Zhu, Z. et al. Historic storms and the hidden value of coastal wetlands for nature-based flood defence. Nat. Sustain. 3, 853–862 (2020).

Jonkman, S. N., Vrijling, J. K. & Vrouwenvelder, A. C. W. M. Methods for the estimation of loss of life due to floods: a literature review and a proposal for a new method. Nat. Hazards 46, 353–389 (2008).

Jonkman, S. N., Maaskant, B., Boyd, E. & Levitan, M. L. Loss of life caused by the flooding of New Orleans After Hurricane Katrina: analysis of the relationship between flood characteristics and mortality. Risk Anal. 29, 676–698 (2009).

Hallegatte, S. Modeling the role of inventories and heterogeneity in the assessment of the economic costs of natural disasters. Risk Anal. 34, 152–167 (2013).

Sun, Y. et al. Global supply chains amplify economic costs of future extreme heat risk. Nature 627, 797–804 (2024).

Wang, D. et al. Supply chains create global benefits from improved vaccine accessibility. Nat. Commun. 14, 1569 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. How to integrate labor disruption into an economic impact evaluation model for postdisaster recovery periods. Risk Anal. 39, 2443–2456 (2019).

Li, J., Crawford-Brown, D., Syddall, M. & Guan, D. Modeling imbalanced economic recovery following a natural disaster using input–output analysis. Risk Anal. 33, 1908–1923 (2013).

Noth, F. & Rehbein, O. Badly hurt? Natural disasters and direct firm effects. Fin. Res. Lett. 28, 254–258 (2019).

Xia, Y. et al. Assessment of the economic impacts of heat waves: a case study of Nanjing, China. J. Clean. Prod. 171, 811–819 (2018).

Fang, D., Duan, C. & Chen, B. Average propagation length analysis for carbon emissions in China. Appl. Energy 275, 115386 (2020).

Fang, D. L. et al. Clean air for some: unintended spillover effects of regional air pollution policies. Sci. Adv. 5, 115386 (2019).

Vazquez Santiago, J., Hata, H., Martinez-Noriega, E. J. & Inoue, K. Ozone trends and their sensitivity in global megacities under the warming climate. Nat. Commun. 15, 10236 (2024).

Xu, R. et al. Global population exposure to landscape fire air pollution from 2000 to 2019. Nature 621, 521–529 (2023).

Bakhtsiyarava, M. et al. Potential drivers of urban green space availability in Latin American cities. Nat. Cities 1, 842–852 (2024).

Chen, B. et al. Contrasting inequality in human exposure to greenspace between cities of Global North and Global South. Nat. Commun. 13, 4636 (2022).

Li, Z. & Chen, B. EULUC China 2.0: Essential Urban Land Use Categories Map across China for 2022 (Shapefile and Geodatabase). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16794007 (2025).

Peng, S. High-spatial-resolution monthly precipitation dataset over China during 1901–2017. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3114194 (2019).

Che, Y. et al. Building height of Asia in 3D-GloBFP. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11397015 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42230106 to C.S., 72574027 to D.F. and 72174029 to D.F.) and the 10th Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (to D.F.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: D.F. Data curation and formal analysis: D.F., F.X. and X.J. Writing—original draft: D.F. Interpretation of the results: D.F., P.G. and D.W. Writing—review and editing: D.F., L.S. and K.F. with input from all co-authors. Funding acquisition: D.F. and C.S. Supervision: C.S., L.S. and K.F.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cities thanks Jlenia di Noia, Yoomi Kim and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Sectoral composition and trends of fluvial flood-induced losses under different flood recurrence intervals.

Stacked bar plots show the sectoral breakdown and evolution of (a) capital loss, (b) labor loss, (c) local indirect loss (that is, supply-chain disruptions within the affected city), (d) ripple effect (that is, supply-chain disruptions affecting other cities), and (e) total loss, under 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500-year flood. Each color represents a different economic departmental category (see legend above).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Spatial distribution of fluvial flood-induced spillover impacts under 10 and 500-year floods.

a, c: Spatial distribution of the average spillover impact for each city experiences flooding in other regions under 10 and 500-year floods. b, d: Spatial distribution of the average spillover impact as a percentage of each city’s GDP experiences the flood occurs in other regions under 10 and 500-year floods. Cross-hatched areas indicate regions not included in the analysis due to data limitations. Cited from Tianditu https://www.tianditu.gov.cn/.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Top 10 cities with by spillover impact losses under 10 and 500-year fluvial floods.

(a, b) Cities with the largest absolute spillover impact losses (bars: loss value, left axis; dots: loss as % of GDP, right axis) for 10-year (a) and 500-year (b) floods. (c, d) Cities with the highest spillover impact loss ratios (bars: loss value, left axis; dots: loss as % of GDP, right axis) for 10-year (c) and 500-year (d) floods. Bar colors reflect GDP per capita (red = low, blue = high). Cities with black triangles (▲) are newly ranked in the top 10 under 500-year floods. Asterisks (*) denote provincial or municipal capitals.

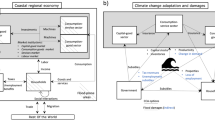

Extended Data Fig. 4 Schematic diagram of the methodological framework.

Coupling mechanisms for overlay, direct loss, and economic recovery modules.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, uncertainty analysis and parameter calibration, Supplementary Results, model limitations and pathways for enhancement, Supplementary Figs. 1–8 and Supplementary Tables 1–9.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, D., Xu, F., Jin, X. et al. Stress-testing the cascading economic impacts of urban flooding across 306 Chinese cities. Nat Cities 3, 89–101 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00372-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00372-1