Abstract

A reliable early risk prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) allows for early lifestyle modifications during pregnancy to reduce the risk of developing GDM. In this retrospective study, we developed a logistic regression machine learning model with heart rate variability (HRV) characteristics during overnight sleep in early pregnancy as predictors for GDM prediction. The study used the nuMoM2b dataset from 2748 nulliparous women in the USA who underwent a standardized home sleep test between 6 and 15 weeks’ gestation with subsequent GDM assessment at 24–28 weeks. A total of 52 overnight HRV features were analyzed alongside the baseline risk factors recommended by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The model combining baseline and HRV features achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.73, outperforming the model using only baseline features (AUC = 0.69) and that using only HRV features (AUC = 0.65). These machine learning models all performed better than the early GDM risk assessment based on the NIH guidelines (AUC = 0.63). The findings suggest that overnight maternal HRV characteristics can be used as early predictors of GDM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy1, and is one of the most common adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs). The prevalence of GDM varies across countries and regions. A recent meta-analysis reported an average prevalence of GDM of 14.7% based on the criteria of the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG)2. In South or East Asia, it can be higher than 20%3,4. Differences in GDM diagnostic standards can explain differences in prevalence5. For decades, less attention was spent on GDM than on other APOs, since it was considered, in comparison with other outcomes that could directly cause maternal or fetal death, to have a relatively mild impact and was often considered fully reversible after delivery. However, it is increasingly understood that in addition to causing maternal hyperglycemia, GDM can induce breathing difficulties6,7, cesarean section8, urinary tract infection9, hydramnios, pregnancy induced hypertension10, and even preeclampsia11 on the mother. Uncontrolled GDM has a possibility of up to 87% in developing type II diabetes in 5–10 years after delivery12. For the infant, GDM exposes the newborn to an elevated risk of macrosomia13, postpartum hypoglycemia14, and future obesity15. GDM also imposes an additional economic burden on family and society. Research shows that pregnant women with diagnosed GDM spent up to 34% more costs in maternal care and 49% more in neonatal care than non-GDM pregnancies4,16.

Currently, clinical GDM risk screening is usually performed by an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation. In the second trimester, as pregnancy progresses, surges in local and placental hormones, including estrogen, progesterone, leptin, cortisol, placental lactogen, and placental growth hormone, combine to promote a state of insulin resistance17. Women who cannot produce enough insulin to adapt to this resistance will have increased blood glucose levels, so OGTT can screen out GDM at this stage18. However, emerging evidence indicates that abnormal fetal growth can start prior to the commonly used GDM diagnosis period19,20. Moreover, for pregnant women with advanced maternal age or BMI, GDM diagnosed at 24–28 weeks’ gestation already affected fetal abdominal circumference21. Various studies have demonstrated that early lifestyle modifications during pregnancy can help reduce the risk of developing GDM22. By making lifestyle adjustments (such as improving diet and physical activity) as early as possible in pregnancy - typically before 15 weeks —and maintaining them throughout the pregnancy, this effect is enhanced23. Early screening also offers advantages over the 24–28 weeks OGTT in reducing the incidence of adverse neonatal outcomes and severe perineal injury24,25, with the greatest benefits observed when interventions are initiated before 14 weeks. Furthermore, early diagnosis enables more precise ultrasound monitoring of fetal growth trajectories, allowing for the early detection of abnormal growth patterns (e.g., slow early growth followed by catch-up or accelerated early growth followed by slowing), both of which may increase the long-term risk of metabolic complications26,27. Hence, to facilitate effective treatment and lifestyle adjustments, it is pivotal to accurately predict the risk of developing GDM early in pregnancy.

Numerous studies on early risk prediction of GDM indicate that the most used risk factors are maternal demographics, family history and obstetric history factors (e.g., age, BMI, race and ethnicity, parity, history of GDM, family history of diabetes). Although they are attractive due to their good accessibility, their predictive power is unsatisfactory28. Recent research on biomarkers (e.g., fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1c level29) has been shown to improve GDM prediction accuracy. However, these markers are limited by their invasive and obtrusive acquisition methods and are not widely used in clinical practice. The National Institute of Health recommended a guideline (National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines) for early GDM risk assessment based on eight demographics and history questions. According to the NIH guidelines, the mothers would be graded for the risk of GDM from zero to eight, where a higher grade corresponds to a higher GDM risk.

This study assessed heart rate variability (HRV) as a new predictor for the early prediction of GDM. HRV is the physiological phenomenon of variation in the time interval between heartbeats (known as inter-beat intervals or IBIs). HRV measures can be obtained using, for example, wearable or unobtrusive devices, demonstrating good accessibility, in particular for pregnant women who are already using a wearable device. While technological advancements may enhance accessibility, current adoption requires consideration of device affordability and user literacy. HRV, characterized and quantified using different metrics, can change during pregnancy. In early pregnancy, in order to provide sufficient nutrients for the development of the fetus, maternal cardiac blood volume increases by 30-40% compared with the non-pregnant state, and the average heart rate is also 10-15% faster30. Stein et al.31 reported that mean heart rate (HR), standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN) and power of low frequent band (LF) showed significant difference in early pregnancy, compared with non-pregnant state. Bester et al.32 also reported that the worsening of systolic pulse in pregnant women was significantly different from that in non-pregnant women.

The contribution of autonomic nervous system (ANS) imbalance to the metabolic syndrome is well documented33,34. The overactivation of sympathetic nervous system will stimulate and inhibit pancreatic β-cell insulin secretion35 and may promote insulin resistance by inducing hemodynamic and cellular effects36. A systematic review37 reported that HRV can be used as an indicator of T2DM. Patients with T2DM had significantly higher HR, lower SDNN, RMSSD, LF and HF compared with healthy people. Both GDM and T2DM are associated with impaired insulin secretion and insulin resistance. For pregnancies with potential GDM, due to the fluctuations in hormone levels, automatic imbalances may be more easily induced or amplified.

Yet up to now, the effect of HRV characteristics in GDM prediction has not been explored, and no study has ever established any model using HRV in early pregnancy to predict GDM. This study is the first to develop models based on machine learning (ML) algorithms to verify whether HRV can be used as an early risk predictor for GDM and whether the GDM prediction can be improved when combined with risk factors suggested by existent guidelines for early GDM risk assessment such as the NIH guidelines.

Results

Cohort and HRV characteristics

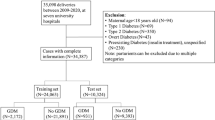

Among all 9289 participants in the nuMoM2b database, 431 (4.6%) had no OGTT, 134 (1.4%) had pre-existing diabetes mellitus, and 6060 (65.2%) did not participate in the home sleep test or did not have the minimum number of 5-min valid segments, resulting in a total of 2748 (29.6%) pregnant women included in this study. Overnight sleep ECG signals were collected during the home sleep test between 11 and 14 weeks of gestation. In nuMoM2b, individuals’ race and ethnicity were originally classified into 8 categories: Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, American Indian, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Other, Multiracial. The “Other” category refers to individuals with clear race and ethnicity information who do not fall into the first six categories and are not multiracial. As shown in Table 1, compared with participants without GDM, those diagnosed with GDM exhibited a significantly higher age and BMI (p < 0.001), higher (diastolic and systolic) blood pressure measures in early pregnancy (p < 0.001), and a higher prevalence in family history of diabetes (p < 0.05) and Asian (p < 0.001) and Other (p < 0.001) in race and ethnicity. No statistical difference was observed in PCOS (p = 0.35), history of miscarriage (p = 0.60), or in the racial/ethnic categories of Non-Hispanic White (p = 0.21), Non-Hispanic Black (p = 0.18), Hispanic (p = 0.87), American Indian (p = 0.75), Native Hawaiian (p = 0.20), and Multiracial (p = 0.71). The mean (SD) number of valid 5-min segments for individuals with GDM was 95.8 (22.7), the proportion of valid segments compared to the total recording time (TRT) was 70.9% (17.7). For non-GDM individuals, the mean (SD) number of valid segments was 95.5 (22.0), the proportion of valid segments compared to TRT was 70.2% (17.2). There were no significant differences between the GDM and non-GDM groups in the number of valid segments (p = 0.94) or the proportion of valid segments to TRT (p = 0.75). In addition, 46 out of 52 overnight statistics features from HRV during early pregnancy were statistically significantly different between GDM and non-GDM pregnancies (Supplementary Table 4).

Evaluation of the NIH guidelines for GDM prediction

We first applied the NIH guidelines on all 2748 samples and obtained GDM risk scores from eight binary variables (one not available as explained in the “Methods”). Figure 1a, b depict the number of individuals and GDM prevalence for each risk assessment level from the NIH guidelines. Since the risk factor “history of insulin resistance or blood glucose problems” is not available for all pregnant women in this study, and no pregnant woman meets all of the remaining seven risk factors simultaneously, the risk score range provided by the NIH guidelines is zero to six. The highest risk level (six) coincided with the highest GDM prevalence, with 10%, about 7 times higher than the risk level zero, for which only ten participants had GDM (less than 0.4%). To calculate the ROC curve when using the NIH guidelines for GDM prediction, we varied the risk score from zero to six as the threshold for decision making of GDM or non-GDM, obtaining an AUC of 0.63. As stated, NIH suggests that pregnancies with a score more than one in the assessment are high-risk pregnancies for GDM38, corresponding to the red bars in Fig. 1a. The NIH suggested-high risk group accounted for about 2/3 of the pregnancies in the studied cohort, but the actual GDM prevalence was only slightly higher than the average (5.9% vs. 4.4%), leading to a large number of false positives.

a and GDM prevalence b for each GDM risk assessment level (risk score) from the NIH guidelines. The gray bar represents NIH-assessed low-risk pregnancies (risk score equals to zero), yellow bar represents average-risk pregnancies (risk score equals to one) and red bar represents high-risk pregnancies (risk score larger than one). GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus.

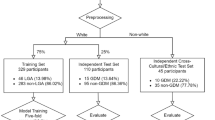

Evaluation of machine learning models for GDM prediction

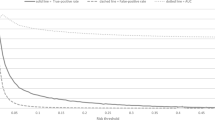

Figure 2 shows the ROC curves and the resulting AUC after ten-fold cross-validation for GDM prediction using the combined model, the baseline model, the HRV model and the NIH guidelines. The combined model achieved the highest AUC of 0.73 [95% CI, 0.72–0.74], superior to the baseline model (AUC = 0.69, [95% CI, 0.68–0.70]), the HRV model (AUC = 0.65 [95% CI, 0.64–0.66]), and the NIH guidelines (AUC = 0.63). The CI for NIH guidelines is not available since the risk scoring criteria of the NIH guidelines are fixed (seen from Supplementary Table 3) and do not need to be obtained through training. Although the NIH guidelines and the baseline model shared the same risk factors, the AUC of the baseline model is 6.1% higher than that of the NIH guidelines. The PR curves of the combined model, the baseline model, the HRV model and the NIH guidelines were shown in Fig. 3. The area under the PR curve (AUPRC) of the combined model is 0.14 [95% CI 0.13–0.15], superior to the baseline model (AUPRC = 0.11 [95% CI 0.10–0.12]), HRV model (AUPRC = 0.07 [95% CI 0.07–0.08]) and NIH guidelines (AUPRC = 0.08). The weighted F1 scores for the NIH guidelines, HRV model, baseline model, and combined model were 0.22, 0.93 [95% CI 0.93–0.94], 0.94 [95% CI 0.93–0.94], and 0.94 [95% CI 0.94–0.94], respectively. Within the GDM subgroup, the corresponding F1 scores were 0.17, 0.96 [95% CI 0.95–0.96], 0.96 [95% CI 0.96–0.96], and 0.96 [95% CI 0.96–0.96]. In the non-GDM subgroup, F1 scores were lower across all models, at 0.09, 0.13 [95% CI 0.12–0.14], 0.19 [95% CI 0.18–0.20], and 0.22 [95% CI 0.20–0.23], respectively. The calibration curves for the combined model, baseline model and HRV model was illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. The combined model can truly reflect the probability of GDM to a degree of 0–15%, superior to the baseline model and the HRV model. Since the nuMoM2b dataset is highly unbalanced and the number of positive samples is limited, the calibration curves of all three models’ experiences fluctuates.

Each curve represents the mean performance of a model across repeated experiments, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the AUC. The CI for NIH guidelines is not available since the risk scoring criteria of the NIH guidelines are fixed and do not need to be obtained through training. AUC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. HRV heart rate variability. NIH National Institutes of Health.

Each curve represents the mean performance of a model across repeated experiments, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the AUC. The CI for NIH guidelines is not available since the risk scoring criteria of the NIH guidelines are fixed and do not need to be obtained through training. AUPRC area under the precision-recall curve, HRV heart rate variability, NIH National Institutes of Health.

Relative feature importance was ranked based on the average absolute coefficient of the normalized features across cross-validation folds, and top 20 relatively prominent features in the combined model were plotted in Fig. 4. A positive coefficient means that the feature has a higher correlation with GDM, while a negative coefficient means that the feature has a higher correlation with non-GDM. It’s important to note that due to the elastic net regularization, these coefficients reflect relative importance rankings rather than absolute magnitudes of association, as the penalization process shrinks toward zero to improve generalizability. This approach prioritizes stable predictors while maintaining clinical interpretability of top-ranked features. Since the combined model was trained and tested using ten-fold cross validation, the coefficients of each feature are likely different. Thus, the SD of each feature was also provided in Fig. 4 as error bars.

Including HRV features derived from noisy segments resulted in a significant decline in model performance: the AUC of the combined model decreased from 0.73 [95% CI 0.72–0.74] to 0.71 [95% CI 0.70–0.72] (p < 001), and that of the HRV model decreased from 0.65 [0.64–0.66] to 0.64 [0.63–0.65] (p < 001). These findings highlight the importance of excluding invalid segments when computing HRV features. The effect of varying the minimum valid segment threshold on model performance was evaluated using repeated experiments to derive AUC, AUPRC, and corresponding 95% CI. Applying an appropriate threshold improved performance for both the HRV and Combined models, compared with using no threshold (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Although the Baseline model does not incorporate HRV features, its performance was also affected due to changes in sample size. Around the threshold used in this study (minimum of 24 valid segments), all three models demonstrated stable performance with minimal variation.

Relatively feature importance was ranked based on the average absolute coefficient of the normalized features across cross-validation folds. The x-axis indicates the absolute value of the coefficient of each feature, averaged between the ten-fold cross-validation; the error bars indicate the corresponding standard deviation. The y-axis indicates the name of each feature. Red bars indicate features with a positive coefficient, blue bars negative coefficients. HR heart rate, BMI body mass index, HF band power of high frequency, SD standard deviation, SDNN standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals, RMSSD root mean square of successive differences, PNN20 proportion of NN intervals differing by >20 ms, PNN20 proportion of NN intervals differing by >50 ms. SD1 minor axis of Poincaré ellipse, SD2 major axis of Poincaré ellipse.

Subgroup analysis

Figures 5 and 6 compare the performance of GDM prediction in different age and BMI subgroups, respectively. The prevalence of GDM for age <25, 25–30 and >30 was 2.3%, 4.1% and 7.6%, respectively. For subgroups of underweight/healthy, overweight and obese, the GDM prevalence was 3.2%, 5.0% and 8.2%, respectively. The combined model outperformed the baseline and the HRV model for pregnant women in all age and BMI subgroups (p < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). Compared with the baseline model, the accuracy improvement of the combined model is higher (10–15%) in the lower and intermediate age and BMI subgroups, and lower in the higher age and/or obese subgroups (2–4%). The women in these two subgroups had a higher prevalence of GDM, and this is consistent with literature39,40. The HRV model underperformed for most subgroups, except for the subgroup of young pregnant women <25 years, where it outperformed the baseline model.

Discussion

Early identification and intervention targeting GDM can help improve pregnancy outcomes22,23. To investigate predictors of this condition, we first evaluated the NIH guidelines as the clinical practice baseline to predict the risk of GDM in early pregnancy. A baseline ML model based on an LR algorithm using the same risk factors from the NIH guidelines showed significantly higher performance than the NIH guidelines (AUC of 0.69 versus 0.63). This improvement likely results from LR’s ability to assign different weights to individual risk factors based on their data-driven relative importance. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6, the coefficients in the baseline model vary, and its performance exceeds that of an equal-weight model (AUC: 0.69 vs 0.66, Supplementary Fig. 7). These findings highlight the advantage of automatic feature weighting in enhancing model performance. However, potential limitations should be acknowledged, as data-driven models that optimize weights may overfit, particularly when trained on small datasets. Such models may exhibit limited generalizability compared with NIH guidelines.

To investigate whether overnight HRV characteristics in early pregnancy can be early predictors for the risk of GDM, we proposed a model using only HRV characteristics, and another model where the HRV characteristics and the risk factors from the baseline model were combined. The combined model achieved the best performance with an AUC of 0.73, 15.9% higher than that using the NIH guidelines, 12.3% higher than the HRV model and 5.8% higher than the baseline model. Considering the study cohort is highly unbalanced, AUPRC was also used to evaluate model performance. The combined model had the highest AUPRC of 0.14, i.e., 75.0% higher than that using the NIH guidelines, 100% higher than HRV model and 27.3% higher than the baseline model.

As maternal age and/or BMI increase, the frequency of sleep disordered breathing events (such as sleep apnea) and nighttime awakenings may increase41,42. Their presence would interfere with the measurement of HRV43 and weaken the effectiveness of HRV characteristics in GDM prediction. From Fig. 4, age and BMI had the highest coefficients in the model, indicated that the individuals with advanced age or BMI are assigned higher GDM predicted value in the model. Often in current clinical practice, pregnant women with advanced maternal age and/or BMI at the beginning of pregnancy will be noted that they have a higher risk of developing GDM. This implies that intervention can be started at the beginning of the pregnancy to reduce the risk of GDM and its adverse consequences. For the younger age or healthier BMI individuals, their GDM risks are often overlooked. The comparison results of model performance in different age and BMI groups in Figs. 5 and 6 showed that the combination of HRV characteristics and clinically suggested risk factors can help the model more accurately identify the individual GDM risk in moderate age and BMI groups, and the AUC can be improved by up to 15% in some subgroups.

It is well known that individuals identifying as Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI) are at a higher risk of developing GDM compared to the other race and ethnicity groups44. In our study cohort, the representation of American Indian and Native Hawaiian participants was substantially lower than that of Asian participants, and their corresponding risk factors were not significantly associated with GDM. To address this, we combined American Indian, Asian, and Native Hawaiian categories into a single AAPI feature and conducted a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the impact of this aggregation on model performance in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6. The results indicated that feature aggregation did not significantly affect the AUPRC across all three ML models. Although a statistically significant change in the AUC was observed, the average change was less than 0.01.

It is challenging to accurately estimate the risk of GDM for nulliparous pregnant women who did not have a history of GDM or avaliable early plasma glucose level. Compared with biomarkers that require blood or body fluid sampling, we investigated the possibility of using the unobtrusive and easily accessible HRV characteristics as additional predictors to predict the risk of GDM. Prior to this study, there was no study considering early pregnancy HRV characteristics used in a prediction model for GDM, and the analysis between HRV and GDM has focused mainly on the end of the second trimester or later45,46,47,48,49. Although some studies45,46,47,48 reported no difference between GDM and non-GDM pregnant individuals in terms of HRV metrics, Pöyhönen-Alho et al.49 reported that the HRV frequency domain components were different between control and GDM groups. In our study, most of the HRV characteristics listed in Supplementary Table 1 showed statistically significant difference (p < 0.05 or p < 0.001) between GDM and non-GDM pregnancies in the nuMoM2b dataset. Furthermore, in the feature importance analysis characterized by logistic regression coefficients, we identified average HR (overnight mean and minimum) as the strongest predictor positively associated with GDM risk. Elevated average heart rate indicates sympathetic overactivation coupled with vagal withdrawal, a pattern consistent with autonomic imbalance observed in metabolic dysregulation50. Conversely, RMSSD, PNN50, SD1, SD1/SD2 ratio, and Poincaré plot area (S) exhibited negative associations with predicted GDM probability. The observed reductions in nocturnal RMSSD means and their variability (SD), alongside diminished SD1 variability, lower SD1/SD2 ratios, and decreased S values, reflect impaired parasympathetic tone and attenuated autonomic regulatory capacity51. Specifically, the decline in SD1 and RMSSD indicates blunted vagally mediated beat-to-beat adjustments, while reduced SD1/SD2 and S values suggest compromised integration of short- and long-term cardiovascular control mechanisms52,53. This confirmed the hypothesis that ANS activity and its manifestation in cardiac rhythms would appear different already in earlier phases of pregnancy in women who develop GDM in later pregnancy. Qiu et al.54 reported that the (daytime, 5-min) resting heart rate in the first trimester is associated with GDM, which also supports our findings. As pregnancy progresses, fetal growth and changes in maternal hormone levels have an impact on the cardiac system and ANS, thereby masking or attenuating differences related to GDM. The findings in our study suggest that the overnight maternal HRV characteristics measured during sleep are novel physiological factors that can aid in the early risk prediction of GDM. From an application perspective, HRV can theoretically be easily measured with a wearable or unobtrusive device at home such as a bracelet, watch, mattress, camera, and radar55,56,57. These unobtrusive methods make it possible to accurately and continuously monitor HRV for multiple nights or even weeks in a home environment, possibly enabling further improvements in the GDM prediction performance.

Although there is currently no consensus on conducting GDM screening for all mothers in early pregnancy, this may be due to limitations of the OGTT. Despite being the gold standard for diagnosing GDM, the OGTT is invasive, time-consuming, and shows low sensitivity in early pregnancy58. Nevertheless, some regional and international organizations have begun to recommend screening for GDM in early pregnancy. For example, a new consensus has been established in the Flanders region to measure fasting blood glucose in early pregnancy59. It is recommended that women with a fasting blood glucose of 5.3–6.9 mmol/L before 20 weeks of pregnancy be diagnosed with early GDM. “International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics” (FIGO) recommend screening universally in early pregnancy for diabetes and GDM60, Italian recommendations state that pregnancies with high risk factors should be tested at 16–18 weeks and an FPG ≥ 5.1 mmol/L is diagnosed as GDM61. And American Diabetes Association62 and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence63 both recommend blood glucose screening in early pregnancy (<15 weeks) for high-risk pregnancies. Importantly, the lack of consensus on early GDM screening not only highlights a research gap but also reinforces the need to explore novel risk factors to enhance early prediction of GDM. This aligns with the aim of our study to advance early risk stratification and ultimately improve maternal and fetal outcomes.

While the LR model with elastic net regularization provided good interpretability and reasonable performance, we also implemented a voting ensemble that combines LR, support vector machine (SVM), and random forest (RF) models. This was done to explore potential performance gains and better capture complex interactions between HRV and other risk factors. The results in Supplementary Table 7 showed that the LR and SVM models performed comparably, while the RF model yielded the poorest results. As a result, the voting model achieved performance similar to the standalone LR model but introduced additional complexity.

This study had several limitations. The nuMoM2b researchers used three different standards of OGTT (non-fasting 50 g OGTT, fasting 75g-2h OGTT, and fasting 100g-3h-OGTT) to diagnose GDM42. This might lead to inconsistency in GDM samples used for training a GDM prediction model, and it is difficult for us to evaluate the impact of the different diagnostic criteria on the prediction of GDM in this dataset. Ideally, different diagnostic standards should be applied and evaluated for same pregnancies, which merits further investigation. Second, in the nuMoM2b dataset, the overnight ECG recording was collected only once per participant during early pregnancy, with variable recording quality and duration. Although removing these noisy segments could ameliorate the data quality and improve model’s performance, the influence of reducing the number of segments on the reliability of HRV estimates still existed. In addition to the ECG recording duration and quality, sleep stage is another important factor that may influence HRV characteristics32. Many invalid segments might likely correspond to wakefulness with movement artifacts, which should be further verified when sleep stages are available. However, sleep stage information was not available in this dataset due to the absence of EEG, the required signal modality in the gold standard polysomnography for sleep staging. Given HRV-based sleep staging has been shown to be feasible64, the effect of sleep stages should be further studied in the future. Besides, HRV characteristics can also alter as pregnancy progresses65. The time-dependent discrepancy of HRV due to different gestational age might confuse the ML model when including HRV for GDM prediction. Future work should investigate the use of prolonged monitoring of HRV for potentially improving the early prediction of GDM. Third, this study only used seven of the eight risk factors recommended by NIH guidelines. The history of GDM, macrosomia or stillbirth and history of insulin resistance or blood glucose problem (except diabetes) are not available in the nuMoM2b dataset, this study is unable to evaluate how the models’ performance would change after including the above unavailable risk factors. Finally, the accessibility of wearable devices used for HRV monitoring may vary across populations, particularly for individuals with lower socioeconomic status (SES) or limited health literacy. While our study demonstrates the technical feasibility of HRV-based prediction, the current reliance on wearable technology could pose barriers to equitable implementation in resource-constrained settings. Future research should validate this approach in socioeconomically diverse cohorts and explore alternative lower cost solutions to improve accessibility.

In conclusion, this study presents the first model designed to predict the risk of GDM early in pregnancy by utilizing overnight maternal HRV, which can potentially be measured unobtrusively at home. By integrating HRV characteristics with risk factors identified in existing guidelines, there was a notable improvement in the accuracy of early pregnancy GDM prediction. This enhancement underscores the utility of maternal HRV characteristics as physiological indicators for forecasting GDM risk.

Methods

Study population

This retrospective study population included individuals who were enrolled in the observational cohort study “Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be” (nuMoM2b), in which nulliparous women with singleton pregnancies were recruited from hospitals affiliated with eight clinical centers in the USA between March, 2011 and September, 2013, and 4 visits were scheduled at 6–13, 16–21, and 22–29 weeks of gestation and at the time of the delivery66. The local institutional review board of each study site approved the study protocol, and all women provided written informed consent before participation. The study population was selected from the original nuMoM2b participants as follows. Women were excluded in case they were diagnosed with diabetes before the current pregnancy, or when they did not undergo OGTT between 24 and 28 weeks gestation, or when they did not join standardized level 3 home sleep test between 6 and 13 weeks’ gestation, or when the sleep monitoring device did not work properly or valid sleep test duration of less than 2 h (equal to 24 valid 5-min segments), resulting in a sample size of n = 2748 participants (121 with GDM [4.4%]). The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development review board (approval date: December 15, 2021, request ID: 11961) and Eindhoven Technology University ethical review board (approval date: November 1, 2021, reference number: ERB2021BME4) approved the study protocol. Our study complied with all relevant ethical regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Assessment of HRV characteristics

Overnight maternal cardiac rhythm was measured through a bipolar ECG sensor of the Embletta-Gold device66 during a home sleep test at the first study visit between 6 weeks and 13 weeks plus 6 days of gestation. The overnight ECG signals were divided into non-overlapping 5-min segments, and a linear phase high-pass filter was used on each segment to eliminate the baseline drift of the ECG signal. The filter used a 1.106 s Kaiser window, a cutoff frequency of 0.8 Hz, and a sidelobe attenuation of 30 dB67. We then removed segments whose average signal amplitude within 5-min segments was much lower than the normal ECG signal (<0.1 mV) and visually confirmed the removed parts. A low-complexity precise QRS complex localization algorithm67 was then used to extract the R interval. We further removed the RR intervals that fell outside the range of more than 0.5–2 s32. In each 5-min interval, if the coverage rate of RR intervals was more than 50%, we considered it as valid segment otherwise it would be treated as noisy segment.

After removing noisy segments disrupted by motion artifacts, for each 5-min segment, HRV properties were quantified as time-domain characteristics (including average HR, SDNN, root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), proportion of NN intervals differing by >20 ms or >50 ms (PNN20/PNN50) and mean absolute deviation (MAD)), frequency-domain characteristics (including ultra-low-frequency (VLF), low-frequency (LF) and high-frequency (HF)) and non-linear-domain characteristics (including, minor axis of Poincaré ellipse (SD1), major axis of Poincaré ellipse (SD2) and area of Poincaré ellipse (S)). Time-domain metrics capture ANS dynamics through sympathetic-parasympathetic balance (average HR), overall rhythm variability (SDNN), rapid parasympathetic modulation (RMSSD), and vagally mediated heartbeat fluctuation thresholds (PNN20/PNN50)68. Frequency-domain oscillations correspond to distinct physiological regulatory processes: VLF associated with metabolic homeostasis69, LF oscillations reflecting baroreflex-mediated blood pressure control70, and HF components synchronized with respiratory-driven vagal activity71. Nonlinear-domain parameters characterize cardiac rhythm complexity via Poincaré plot geometry, where SD1 quantifies instantaneous beat-to-beat variability, SD2 represents long-term regulatory trends, and S (equal to SD1 multiplied by SD2) reflecting global autonomic complexity72. Detailed description of the HRV characteristics is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Then each HRV characteristic was overnight summarized using sample statistics [maximum, minimum, mean and standard deviation (SD)].

NIH guidelines for early risk assessment of GDM

The NIH recommended a self-administered, eight-binary questionnaire for clinicians to determine GDM risk in early pregnancy38. The eight binary questions were applied to data collected in the first study visit and corresponded to eight risk factors: body mass index (BMI), family history of diabetes, race and ethnicity, age, history of GDM or macrosomia or miscarriage or stillbirth, history of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), history of insulin resistance or blood glucose problem, and high blood pressure (systolic pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic pressure ≥90 mmHg) or heart disease (Supplementary Table 2). This study selected this early risk screening or assessment tool to represent the current clinical baseline in GDM early risk prediction, called “NIH guidelines”, for comparison with the proposed ML models. Since all the pregnant women in the nuMoM2b were nulliparous and the women with pre-existing diabetes were excluded from our study population, only history of miscarriage in the risk factor “history of GDM, macrosomia, miscarriage or stillbirth” was available. And for the risk factor “history of insulin resistance or blood sugar problem”, the specific pre-pregnancy blood glucose or insulin resistance levels were not available in the nuMoM2b dataset. We were unable to confirm whether there were participants who had insulin resistance or blood glucose problems before pregnancy except for those already diagnosed with diabetes. In principle, the NIH guidelines assessed the individual’s GDM risk from zero to eight through a risk score add-up methodology. For each question answered “yes”, the individual’s risk score was increased by one37. However, since one question was not available on the nuMoM2b dataset, the maximum risk score that the NIH guidelines could provide is seven.

Machine learning prediction models

We developed three logistic regression (LR) based-ML models, each characterized by the set of input features included: a baseline model, an HRV model and a combined model. The baseline model included seven NIH-recommended risk factors, consisting of age, BMI, race and ethnicity, family history of diabetes, history of PCOS, high blood pressure or heart disease and history of miscarriage. The history of insulin resistance or blood glucose problems were not available except for those diagnosed with diabetes before pregnancy, and this risk factor was removed. The HRV model included all 52 overnight statistics [max, min, mean, and SD] features from 13 HRV characteristics mentioned above. The combined model included both the NIH suggested risk factors and the overnight HRV characteristics. The outcome variable for each subject was a binary value indicating whether the participant was diagnosed with GDM (1) or not (0). (Supplementary Table 3).

Given the simplicity and good interpretability of LR, it has been the most widely used algorithm in GDM risk stratification or prediction28, motivating us to employ the same technique in our study. While LR is often positioned at the intersection of statistics and ML, this study considers it within the framework of statistical ML model, given its data-driven optimization of model parameters. Elastic net regularization was applied separately in each fold of cross validation to cope with potential collinearity and overfitting issues. To help with model convergence, features corresponding to the risk factors or HRV characteristics were z-score normalized before being entered into the model.

All the ML models were trained, validated and tested using ten-fold cross-validation. Participants were randomly partitioned into ten equally sized subsets, referred to as “folds”. Of the ten subsets, eight subsets were used as training sets (80%) for model training, one subset was used as the validation set (10%) for optimizing the model’s hyper-parameters and the remaining one subset was held out as the test set (10%) for testing the model. The cross-validation process was repeated ten times, with each of the ten subsets used exactly once as the test set. Within each training set we computed the Cohen’s d effect size for each feature to assess its discriminative capability for GDM and then applied effect size-based feature selection thresholds ranging from 0.2 (small effect) to 0.8 (large effect) during hyperparameter tuning73. The hyperparameters were tuned using the validation set, including the regularization strength (C) over a range from 0.1 to 1, the L1 ratio with values from 0 to 1, and the effect size-based feature selection threshold ranging from 0.2 (small effect) to 0.8 (large effect). The model performance in predicting GDM was assessed using the area under the receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) and area under the precision-recall (PR) curve (AUPRC) and F1 score for all test results of cross-validation. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the AUC, AUPRC and F1 score of each model was provided through 100 times randomly shuffled repeated experiments.

To assess the impact of identifying and excluding invalid segments, we first evaluated how the inclusion of such segments influenced model performance by comparing results when HRV features were derived from all segments versus only valid ones, with the study population being constant. We then examined how the number of valid segments, among samples deemed to contain only valid data, affected the reliability of HRV estimation and its contribution to model performance. Performance metrics, including AUC and AUPRC with corresponding 95% CI, were obtained through repeated experiments.

In the subgroup analysis, we compared the performance of the baseline, the HRV and the combined model under different age and BMI subgroups. Calibration curves were also plotted to evaluate the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes for the three ML models.

For statistical analysis, the two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to examine the statistical significance of risk factors and characteristics between the GDM and non-GDM groups, and Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was used to adjust p value. Model performance was also statistically compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development—Data and Specimen Hub: https://dash.nichd.nih.gov/study/226675.

Code availability

The code generated for data analysis in the current study is available from the corresponding author (X.L.) on reasonable request.

References

Metzger, B. E. Summary and recommendations of the Third International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes 40, 197–201 (1991).

Saeedi, M. et al. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus when implementing the IADPSG criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 172, 108642 (2021).

Yuen, L. et al. Projections of the prevalence of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy in 2019 and beyond: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 157, 107841 (2019).

Gillespie, P. et al. Modeling the independent effects of gestational diabetes mellitus on maternity care and costs. Diabetes Care 36, 1111–1116 (2013).

Behboudi-Gandevani, S. et al. The impact of diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes on its prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 11, 11 (2019).

Bisson, M. et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus and sleep-disordered breathing. Obstet. Gynecol. 123, 634–641 (2014).

Izci Balserak, B. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with newly diagnosed gestational diabetes mellitus. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 17, 754–761 (2020).

Boriboonhirunsarn, D. & Waiyanikorn, R. Emergency cesarean section rate between women with gestational diabetes and normal pregnant women. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 55, 64–67 (2016).

Yefet, E. et al. The association between gestational diabetes mellitus and infections in pregnancy-systematic review and meta-analysis. Microorganisms 11, 1956 (2023).

Hwu, L.-J. et al. Risk of subsequent hypertension and diabetes in women with hypertension during pregnancy and gestational diabetes. Mayo Clin. Proc. 91, 1158–1165 (2016).

Weissgerber, T. L. & Mudd, L. M. Preeclampsia and diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 15, 9 (2015).

Ratner, R. E. et al. Prevention of diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes: effects of metformin and lifestyle interventions. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 4774–4779 (2008).

Kc, K. et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus and macrosomia: a literature review. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 66, 14–20 (2015).

Voormolen, D. N. et al. Neonatal hypoglycemia following diet-controlled and insulin-treated gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 41, 1385–1390 (2018).

Zhao, P. et al. Maternal gestational diabetes and childhood obesity at age 9–11: results of a multinational study. Diabetologia 59, 2339–2348 (2016).

Kolu, P. et al. Health care costs associated with gestational diabetes mellitus among high-risk women–results from a randomised trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 12, 71 (2012).

Plows, J. F. et al. The pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3342 (2018).

Rani, P., Reddi, P. & Begum, J. Screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus, where do we stand. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 10, QE01–QE04 (2016).

Venkataraman, H. et al. Increased fetal adiposity prior to diagnosis of gestational diabetes in South Asians: More evidence for the ‘thin-fat’ baby. Diabetologia 60, 399–405 (2017).

Sovio, U. et al. Accelerated fetal growth prior to diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study of nulliparous women. Diabetes Care 39, 982–987 (2016).

Kim, W. et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation in older and obese Women: Is it too late?. PLoS One 14, e0225955 (2019).

Song, C. et al. Lifestyle intervention can reduce the risk of gestational diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 17, 960–969 (2016).

McIntyre, H. D. et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 5, 47 (2019).

Hivert, M.-F. et al. Pathophysiology from preconception, during pregnancy, and beyond. Lancet 404, 158–174 (2024).

Simmons, D. et al. Treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed early in pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 2132–2144 (2023).

Prentice, P. M. et al. Reduced size at birth and persisting reductions in adiposity in recent, compared with earlier, cohorts of infants born to mothers with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 62, 1977–1987 (2019).

van Poppel, M. N. M. et al. Is the biphasic effect of diabetes and obesity on fetal growth a risk factor for childhood obesity?. Diabetes Care 46, 1124–1131 (2023).

Lamain-de Ruiter, M. et al. Prediction models for the risk of gestational diabetes: a systematic review. Diagn. Progn. Res. 1, 3 (2017).

Fong, A. et al. Use of hemoglobin A1c as an early predictor of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 211, 641.e1–7 (2014).

Ciliberto, C. F. & Marx, G. F. Physiological changes associated with pregnancy. Update Anaesth. 9, 1–3 (1998).

Stein, P. K. et al. Changes in 24-hour heart rate variability during normal pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 180, 978–985 (1999).

Bester, M. et al. Maternal cardiorespiratory coupling: differences between pregnant and nonpregnant women are further amplified by sleep-stage stratification. J. Appl. Physiol. 135, 1199–1212 (2023).

Hu, M. X. et al. Basal autonomic activity, stress reactivity, and increases in metabolic syndrome components over time. Psychoneuroendocrinology 71, 119–126 (2016).

Wulsin, L. R. et al. Autonomic imbalance as a predictor of metabolic risks, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and mortality. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100, 2443–2448 (2015).

Moullé, V. S. et al. The autonomic nervous system regulates pancreatic β-cell proliferation in adult male rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 317, E234–E243 (2019).

Jamerson, K. A. et al. Reflex sympathetic activation induces acute insulin resistance in the human forearm. Hypertension 21, 618–623 (1993).

Benichou, T. et al. Heart rate variability in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 13, e0195166 (2018).

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS. Am I at Risk for Gestational Diabetes? 12–4818 (U.S. Government Printing Office, 2012).

Li, Y. et al. Maternal age and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 120 million participants. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 162, 108044 (2020).

Torloni, M. R. et al. Prepregnancy BMI and the risk of gestational diabetes: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 10, 194–203 (2009).

Louis, J. M. et al. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 218, 521.e1–521.e12 (2018).

Haas, D. M. et al. A description of the methods of the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be (nuMoM2b). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 212, 539.e1–539.e24 (2015).

Qin, H. et al. The different facets of heart rate variability in obstructive sleep apnea. Front. Psychiatry 12, 642333 (2021).

Gregory, E. C. W. & Ely, D. M. Trends and characteristics in gestational diabetes: United States, 2016-2020. Natl. Vital. Stat. Rep. 71, 1–15 (2022).

Weissman, A. et al. Power spectral analysis of heart rate variability during the 100-g oral glucose tolerance test in pregnant women. Diabetes Care 29, 571–574 (2006).

Heiskanen, N. et al. Gestational diabetic patients with adequate management have normal cardiovascular autonomic regulation during the third trimester of pregnancy and 3 months after delivery. J. Diabetes Complicat. 24, 234–241 (2010).

Maser, R. E. et al. Autonomic modulation in gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Complicat. 28, 684–688 (2014.

Žákovičová, E. et al. ECG body surface mapping in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus and optimal metabolic compensation. Physiol. Res. 4(63 Suppl), S479–S487 (2014).

Pöyhönen-Alho, M. et al. Imbalance of the autonomic nervous system at night in women with gestational diabetes. Diabet. Med. 27, 988–994 (2010).

Svensson, M. K. et al. Alterations in heart rate variability during everyday life are linked to insulin resistance. A role of dominating sympathetic over parasympathetic nerve activity?. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 15, 91 (2016).

Arroyo-Carmona, R. E. et al. Heart rate variability as early biomarker for the evaluation of diabetes mellitus progress. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 8483537 (2016).

Ciccone, A. B. et al. Reminder: RMSSD and SD1 are identical heart rate variability metrics. Muscle Nerve 56, 674–678 (2017).

Kubičková, A. et al. Heart rate variability analysed by Poincaré plot in patients with metabolic syndrome. J. Electrocardiol. 49, 23–28 (2016).

Qiu, J. et al. Early-pregnancy maternal heart rate is related to gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 268, 31–36 (2022).

Zheng, Y.-L. et al. Unobtrusive sensing and wearable devices for health informatics. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 61, 1538–1554 (2014).

Chen, S. et al. Flexible wearable sensors for cardiovascular health monitoring. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, e2100116 (2021).

Werth, J. et al. Unobtrusive sleep state measurements in preterm infants—a review. Sleep. Med. Rev. 32, 109–122 (2017).

Huhn, E. A. et al. Sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of WHO 2013 criteria for diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus in low risk early pregnancies: International, prospective, multicentre cohort study. BMJ Med. 2, e000330 (2023).

Benhalima, K. et al. The 2024 Flemish consensus on screening for gestational diabetes mellitus early and later in pregnancy. Acta Clin. Belg. 79, 217–224 (2024).

Hod, M. et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) initiative on gestational diabetes mellitus: a pragmatic guide for diagnosis, management, and care. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 131, S173–S211 (2015).

Torlone, E. et al. Italian recommendations for the diagnosis of gestational diabetes during COVID-19 pandemic: position statement of the Italian Association of Clinical Diabetologists (AMD) and the Italian Diabetes Society (SID), diabetes, and pregnancy study group. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 30, 1418–1422 (2020).

Webber, J., Charlton, M. & Johns, N. Diabetes in pregnancy: management of diabetes and its complications from preconception to the postnatal period (NG3). Br. J. Diabetes 15, 107–111 (2015).

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee 15. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: standards of care in diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care 48, S306–S320 (2025).

Radha, M. et al. A deep transfer learning approach for wearable sleep stage classification with photoplethysmography. NPJ Digit. Med. 4, 135 (2021).

Speranza, G. et al. Autonomic changes during pregnancy: assessment by spectral heart rate variability analysis. J. Electrocardiol. 31, 101–109 (1998).

Facco, F. L. et al. NuMoM2b sleep-disordered breathing study: objectives and methods. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 212, 542.e1–127 (2015).

Fonseca, P. et al. A novel low-complexity post-processing algorithm for precise QRS localization. SpringerPlus 3, 376 (2014).

Shaffer, F. & Ginsberg, J. P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front. Public Health 5, 258 (2017).

Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation 93, 1043–1065 (1996).

Malliani, A. et al. Cardiovascular neural regulation explored in the frequency domain. Circulation 84, 482–492 (1991).

Berntson, G. G. et al. Heart rate variability: origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology 34, 623–648 (1997).

Hoshi, R. A. et al. Poincaré plot indexes of heart rate variability: relationships with other nonlinear variables. Auton. Neurosci. Basic Clin. 177, 271–274 (2013).

Masino, N. & Quintero-Rincón, A. Effect sizes as a statistical feature-selector-based learning to detect breast cancer. In Proc. IEEE Biennial Congress of Argentina (ARGENCON) (IEEE, 2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was performed within the framework of the Eindhoven MedTech Innovation Center (e/MTIC) and was funded by the China Scholarship Council (Grant No: 201906340168). The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.W., X.L., S.A., and M.v.d.V.; Data curation: Y.W., S.A., M.v.d.V., and M.B.v.d.H.; Formal analysis: Y.W., S.A., M.v.d.V., M.B.v.d.H., and X.L.; Investigation and clinical interpretation: M.v.d.V.,. M.B.v.d.H., P.F., S.O., E.P. and S.G.O.; Writing—original draft: Y.W. and X.L.; Writing—review & editing: S.A., M.v.d.V., M.B.v.d.H., S.G.O., M.M., P.F., S.O., and E.P.; Supervision: M.M. and X.L.; Funding acquisition: Y.W. and X.L.; All authors had full access to the data in the study and accepted responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

At the time of writing, S.A. and P.F. were employed by or affiliated with Royal Philips, a health-tech company and manufacturer of consumer and medical electronic devices, commercializing products and solutions in the area of mother and child-care. Philips had no role in the study design, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Asvadi, S., van der Ven, M. et al. Overnight maternal heart rate variability for early prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus: a retrospective cohort study. npj Womens Health 3, 37 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44294-025-00081-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44294-025-00081-z