Abstract

This perspective article aims to provide an update on current trends in the research of radiolabelled siderophores for molecular imaging of bacterial infections. It begins by explaining the importance of developing novel diagnostic tools for infections and addresses the limitations of contemporary methods, including molecular imaging. The discussion then shifts to compounds currently being studied for nuclear imaging, with a focus on radiolabelled siderophores and recent advances in their development. It also provides the latest insights into the structures of siderophores, their utilisation by bacteria and their role in bacterial metabolism, as well as potential for labelling with various radioisotopes. Additionally, it presents the use of radiolabelled siderophores, both naturally occurring and artificial siderophore derivates, for imaging of various bacterial infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction – need for a new diagnostic tool

In general, bacterial infections are the second leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for approximately 7.7 million deaths per year1,2. The five most common pathogens in these infections are: Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa2. The situation is becoming increasingly serious with the alarming rise in antimicrobial resistance. If no precautions are taken, some researchers estimate that by 2050, the number of deaths annually caused by antimicrobial-resistant bacterial infections may exceed 10 million3. Data show that antimicrobial resistance is largely caused by the extensive misuse and over-prescription of antimicrobial agents. Diagnostic uncertainty, which often leads to empirical treatment, plays a major role in this situation4. Current diagnostic tools that provide insight into the patient’s condition and reflect their current state of health (such as C-reactive protein estimation) have contributed significantly to the reduction in antibiotic use5. However, not all current methods have all the requirements to diagnose bacterial infections accurately and quickly enough. For example, molecular techniques (such as polymerase chain reaction) may not be able to distinguish between simple bacterial colonisation and active infection, and traditional culture-based procedures are often time-consuming and resource-intensive6,7,8. In addition, both methods are susceptible to contamination and rely on accurate sampling, which may involve invasive procedures that pose a greater risk to critically ill patients9,10.

For these reasons, molecular imaging techniques are emerging as a non-invasive, time-sensitive means of rapidly diagnosing bacterial infections. With the right tracer, hybrid imaging techniques, such as positron emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) combined with either computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) could not only localise the ongoing infection in the patient and provide the results on the same day as the scan, but could potentially also quantify the bacterial burden and monitor the response to the antibiotic therapy11,12,13. However, current methods do not fulfil the potential of optimal bacterial imaging tracers. Traditionally used 2-deoxy-2[18F]fluoro-D-glucose ([18F]FDG) and [67Ga/68Ga]Ga-citrate are both taken up by metabolically active tissues, including inflammatory or malignant cells, making it difficult to differentiate these pathologies from bacterial infections14,15,16. In addition, these tracers can have high non-specific background uptake in healthy tissues (e.g., the brain, myocardium or kidneys for [18F]FDG), which can complicate the interpretation of results at these sites17. A different approach to bacterial infection imaging is the radiolabelling of white blood cells (WBC). Autologous WBCs are labelled (e.g., with [111In]In-oxine, or the newer [99mTc]Tc-hexamethylpropylenamine oxime) and then reinjected into the patient. However, this method is time-consuming and requires handling of patient blood samples, which are prone to contamination18,19.

Considering the limitations of available methods, the current search for novel bacteria-specific radiolabelled molecular imaging probes needs to focus on several characteristics that an optimal tracer should possess in order to provide a diagnostic method superior to conventional methods. These include, of course, high specificity for bacterial infections, allowing differentiation from other pathologies, but perhaps also some distinction between the bacterial species, such as the Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, to provide an advantage in tailoring the treatment plan20. High sensitivity of the tracer allows detection of the disease in its early stages. High affinity for the targeted infected tissue, with rapid accumulation of the tracer at the site of interest, followed by prolonged retention, ensures low non-specific uptake in other tissues and low background signals. Such high contrast could provide a signal proportional to the infectious burden, providing a means of monitoring disease progression and response to treatment21. The selected radionuclide should have a half-life long enough for the procedure to be performed, while keeping radiation exposure as low as reasonably achievable. Other suitable characteristics include high metabolic stability of the tracer, non-toxicity, availability and low production costs20,22.

Various compounds are being tested in the search for a novel imaging tool for infections, such as radiolabelled antibodies (e.g., non-specific human immunoglobulin or antigen-specific monoclonal/polyclonal antibodies)23,24, antibiotics (e.g., 99mTc-labelled ciprofloxacin, 18F-fluoropropyl-trimethoprim, 18F-vancomycin based radiotracers)25,26,27 in, human neutrophil peptide)28,29,30, vitamins ([111In]In-biotin, [99mTc]Tc-B12-derivate)31,32, aptamers33,34, bacteriophages35 or diverse molecules employing bacterial metabolism (e.g., sugars, sugar alcohols, D-amino acids, N-Acetyl muramic acid derivates, para-aminobenzoic acid, nucleoside analogues, or siderophores)36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43.

Although the possibility of radiolabelling siderophores has been explored since the 1970s, it has received increasing attention in recent years, due to the growing popularity of molecular imaging techniques44. Furthermore, the proof-of-concept studies demonstrating the ability to radiolabel siderophores with gallium-68 have stimulated further siderophore research. The earlier studies revealed the possibility of imaging mould infections caused by Aspergillus fumigatus in this way45,46,47, and later experiments, which will be discussed further in this article, extended the application of the same principle to bacterial pathogens48,49,50,51.

This review aims to provide an overview of siderophores, the current understanding of their basic mechanism and their applicability to the diagnosis of bacterial infections using molecular imaging techniques and to update the state of knowledge in this field following previous reviews52,53.

Siderophores: bacterial iron scavengers

Iron is an essential element that plays a fundamental role in the survival of almost all microorganisms, including bacteria. It is involved not only in their basic metabolism, growth and replication, but also in their virulence. For example, the availability of iron has a direct effect on biofilm formation and toxin production in some bacteria54,55. In nature, iron occurs in two oxidation states: ferrous (Fe2+) and ferric (Fe3+). While the latter is more abundant under aerobic conditions, it is insoluble in water at physiological pH, making it less bioavailable compared to the more soluble ferrous iron55,56. For these reasons, bacteria have developed several strategies to compete with their mammalian hosts for iron during an infectious process. These strategies can be divided into four main categories: (1) Direct iron uptake in ferrous form; (2) acquisition from host proteins such as lactoferrin, transferrin or ferritin; (3) acquisition from haem; and (4) siderophore-mediated iron uptake57.

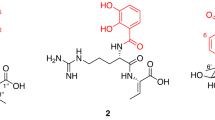

Iron acquisition by siderophores has been identified in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. These low molecular weight iron chelators scavenge iron from the external environment of the bacteria or by removing it from the host proteins, as they have very high ferric-ion association constants (1020-1030 M-1)55,58. Currently, more than 700 known structurally unique siderophores are known, and the number is constantly increasing59. They can be divided into 4 main categories, based on the chemical composition of their chelating moieties: (a) carboxylates; (b) catecholates and phenolates; (c) hydroxamates or (d) mixed siderophores (Fig. 1)60.

Adapted from Siderite and PubChem, created in ChemSketch59. (1) Carboxylates: a Staphyloferrin B, b Proferrorosamine A; (2) Catecholates and Phenolates: c Enterobactin, d Acinetobactin; (3) Hydroxamates: e Putrebactin, f Desferrioxamine B; (4) Mixed siderophores: g Aerobactin, h Quinolobactin, i Salmochelin SX.

The structure of siderophores affects many aspects of the siderophore metabolism, including siderophore recognition by receptors and transporters and iron utilisation. The importance of this fact is demonstrated, e.g., by a recently published study by Krasulova et al., which discusses the effect of cis-trans isomerism of two siderophores, ferrirubin (FR) and ferrirhodin (FRH), on their radiolabelling, in vitro properties and in vivo behaviour. Although these siderophores have the same chemical formula, they differ in the 3D orientation of their acyl groups. The main findings of this study were that the nuance in their structure results in significantly higher plasma protein binding values for [68Ga]Ga-FRH (~50% vs. 6% after 120 min incubation), and as expected from the in vitro results, the authors observed a significantly slower pharmacokinetics of [68Ga]Ga-FRH and its retention in blood and most of the organs, confirmed by both ex vivo animal studies and in vivo PET/CT imaging. The mentioned study further showed that although both siderophores are produced by fungi, they exhibit significant uptake in various bacterial species in vitro. This is a practical example of siderophore piracy, which is explained later in this work. Additionally, the study evaluated the biodistribution of radiolabelled siderophores using PET/CT imaging in a murine model of Staphylococcus aureus-induced myositis. Myositis was induced in the left hind limb of immunosuppressed mice by injecting 50 µL of live S. aureus culture five hours before imaging. To assess tracer specificity, the contralateral hind limb was injected with an equivalent volume of heat-inactivated S. aureus. This model allows in vivo assessment of tracer uptake at both infected and control sites within the same animal, thereby minimising inter-animal variability. The use of heat-inactivated bacteria enables a direct evaluation of whether tracer accumulation reflects the presence of viable bacteria or is merely associated with inflammation induced by bacterial presence. The imaging showed clear accumulation of both 68Ga-siderophores in the infected tissue and no significant uptake in the heat-inactivated culture (Fig. 2)61.

These MIP images were taken 5 h after infection and 45 min after administration of radiolabelled siderophore. Previously published by Krasulova et al.61.

Unique metabolism of microbial siderophores

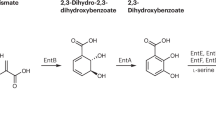

The metabolism of siderophores in bacteria is quite unique. The biosynthesis of siderophores depends on the availability of iron in the surrounding environment, as their production is up-regulated when iron is deficient. Synthesis occurs in three main ways in the bacterial cell, depending on the enzymes that are involved in their production. Some siderophores, such as enterobactin and salmochelins, are produced by the non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) multienzymes; other siderophores, such as ferrioxamines and acinetoferrin, are synthesised by NRPS-independent siderophore synthetase enzymes62,63,64. However, the production of some siderophores (e.g., yersiniabactin, albomycin) involves more than one type of enzyme and can therefore be described as “hybrid” production65. Synthesised siderophores are then exported into the cytoplasm to the external environment, where they chelate iron and form iron-siderophore complexes.

The iron-siderophore complex is then transported back into the bacteria by specific transport systems. As the mechanism of iron-siderophore uptake has been extensively described in previous sources66,67,68, we will only provide a basic overview of the mechanism involved in iron-siderophore import, as it plays an important role in understanding the use of siderophores for bacterial imaging. In both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, the specificity of siderophore receptors varies—some are highly specific for a single siderophore, while others are more permissive and can recognise multiple structurally related siderophores. This allows some bacteria to exploit siderophores that are not produced by the bacterium itself. This phenomenon is often referred to as siderophore piracy or xenosiderophore utilisation69. As this strategy gives bacteria an advantage in the competition for available iron, it is used by a variety of bacterial species70,71,72. Additional details concerning xenosiderophores are thoroughly discussed in a review published by Kumar et al.73.

The uptake of the iron-siderophore complex differs between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria due to differences in the composition of their cell walls. Gram-positive bacteria lack an outer membrane and have a cell membrane that is surrounded by a thick layer of peptidoglycan. The iron-siderophore complex is therefore bound to a siderophore binding protein (SBP), which is anchored directly to the bacterial cell membrane74. The complex is then transported by a permease protein in a process that is energised by ATP-binding cassettes (ABC). The ABCs provide the conformational changes that push the siderophore complex through the transmembrane channel and into the cytoplasm75.

In Gram-negative bacteria, the iron-siderophore complex is initially recognised by the outer membrane receptor (OMR), which interacts with the inner-membrane TonB protein. TonB is driven by other inner membrane proteins, ExbB and ExbD, which together induce a conformational change in the OMR. This alteration causes the iron-siderophore complex to be transported across the outer membrane into the periplasmic space76. In the periplasm, depending on the bacterial strain and siderophore type, the iron-siderophore complex is either directly cleaved or transported further into the bacteria77. In each case, the components are transferred across the inner membrane by the ABC-associated periplasmic binding protein (PBP), in a manner similar to Gram-positive bacteria78,79. The process of siderophore uptake in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Created in https://BioRender.com. Bendová, K. (2025) (Gram-positive) https://BioRender.com/5d0c3ij and (Gram-negative) https://BioRender.com/c57m966.

Siderophores as radiotracers

Due to the structural composition of siderophores and the mechanism by which they are taken up by bacteria, siderophores can be considered promising candidates for radiolabelling. The iron naturally bound to siderophores can be easily substituted by a radioisotope, providing an opportunity for delivering a selected isotope into the bacterial cell. Historically, the first experiments exploiting this principle were performed in 1980 by Emery and Hoffer, who successfully radiolabelled the ferrichrome siderophore with gallium-67. They were soon followed by Chandra et al., who labelled desferrioxamine B (DFO-B) with indium-11144. Both groups demonstrated that these isotopes form complexes with siderophores and that the resulting complexes retain their biological uptake into microorganisms44,80,81. Both gallium and indium are trivalent metal cations with similar coordination chemistry to that of iron, making them suitable substitutes in siderophores, with gallium forming slightly higher stability complexes than indium61,82. These isotopes have been clinically used as SPECT imaging agents since the 1970s. Both decay by electron capture with a half-life of 3.3 and 2.8 days, respectively. These longer half-lives allow for extended imaging protocols, such as monitoring infection progression or therapeutic response, but the prolonged radiation exposure to the patient must be considered83. Another disadvantage is that both isotopes require high-energy cyclotron production, limiting their availability compared to generator-produced isotopes84.

With the advances in imaging technology, the development of siderophore radiotracers expanded to PET isotopes. Gallium-68 was among the first clinically relevant PET isotopes investigated for siderophore labelling39,45. Its major advantage is availability from an on-site 68Ge/68Ga generator, which is fairly long-lived (T1/2 = 271 days) and relatively affordable. Gallium-68 has a short half-life (67 minutes), resulting in a lower radiation burden for patients. Such a short half-life does not pose a concern for siderophore imaging. These compounds usually exhibit rapid biodistribution, and significant accumulation in the targeted infected tissue has been observed as early as 5-10 minutes post-injection in mice50,85. Some concerns have been brought up regarding the positron energy of gallium-6886. Its mean positron energy (Eβ+ max = 1.89 MeV) is higher than that of other PET isotopes (e.g., fluorine-18, Eβ+ max = 0.63 MeV), which increases the distance between the location of the decaying parent nucleus and positron annihilation87. This leads to reduced spatial resolution and scan sensitivity88. Nevertheless, contemporary technologies involving positron range corrections and denoising techniques can decrease this effect87. Additionally, the PET isotope, zirconium-89, was also reported to form stable complexes with siderophores47. Zirconium-89 emits lower-energy positrons (Eβ+max = 0.89 keV) than gallium-68 and has a considerably longer half-life than gallium-68 (78.4 h), making it more suitable for slow-accumulating tracers such as antibodies or nanoparticles rather than siderophores. Unlike gallium-68, zirconium is produced in a medical cyclotron, which limits its accessibility89. Recently, research has also been exploring the potential of alternative radioisotopes for siderophore labelling, which are discussed in respective sections.

An important aspect to consider in the research of radiolabelled siderophores and their potential for clinical translation is the availability of native siderophores. DFO-B (marketed as Desferal®) is the most notable exception, as it is widely commercially available and already used clinically, for example, for the treatment of iron overload and aluminium toxicity. A few other well-studied siderophores, such as enterobactin, staphyloferrin, or pyoverdines, can also be purchased commercially. However, many siderophores remain difficult to access, and research progress is often limited by restricted supply. Nonetheless, as interest in siderophores has increased in recent decades, numerous protocols for their acquisition have been published despite the substantial structural diversity of these compounds. In general, siderophores can be obtained either by chemical synthesis or by isolation from microbial cultures that naturally produce the compound90,91,92,93. Both strategies have limitations and require significant expertise, which hinders the large-scale production needed for clinical translation94,95. In the case of chemical synthesis, challenges include the molecular complexity of siderophores, the presence of enantiomers, and, in many cases, low yields, which increase the production cost95,96. Concerning isolation, the key limitations involve careful selection of siderophore-producing species, which must be evaluated for biological safety and production capacity. Furthermore, incubation conditions, particularly the formulation of the growth medium, play a decisive role, as iron availability directly regulates siderophore secretion and non-optimised conditions often lead to reduced yields. Final extraction and purification require compound-specific protocols, posing an additional obstacle for their mass production. Addressing all these challenges is crucial for enabling the full-scale translation of siderophores for clinical use, and is discussed in more detail in previously published reviews95,96.

In summary, the optimal choice of siderophore–isotope combination must balance several factors. The radionuclide should exhibit coordination chemistry comparable to Fe(III) to ensure efficient complexation. Radiolabelling must not compromise the siderophore’s recognition and uptake by bacterial transport systems. The resulting complex should remain stable against competing endogenous metals, even though their free concentrations in vivo are generally low97. Furthermore, the physical properties of the isotope—such as half-life, emission characteristics, and clinical availability—must be compatible with the pharmacokinetic profile of the chosen siderophore. In any case, the optimal siderophore-based tracer should comply with the requirements of other radiotracers, as was discussed above20.

Radiolabelled natural siderophores

To explore radiolabelled siderophores' potential for bacteria-specific imaging, Petrik et al. evaluated the potential for detecting Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections using a gallium-68-labelled siderophore naturally produced by the bacterium, pyoverdine (PAO1). The study revealed that [68Ga]Ga-PAO1 behaves similarly to its ferric analogue, exhibiting high uptake in P. aeruginosa cultures while retaining high specificity for this pathogen. In animal models, [68Ga]Ga-PAO1 demonstrated excellent biodistribution, with rapid renal clearance and selective accumulation in infected muscle tissue, showing superior performance compared to clinically used tracers ([68Ga]Ga-citrate, [18F]FDG)48.

Siddiqui et al. investigated the possibility of radiolabelling the siderophore yersiniabactin (YbT) with a range of radiometals: 55Co, 64Cu, 68Ga, and 89Zr. The authors demonstrated that [64Cu]Cu-YbT has the highest complexation and showed that it is taken up by bacteria expressing the FyuA receptor, which is known to mediate the import of YbT into bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Furthermore, the affinity of [64Cu]Cu-YbT for bacterial infection in vivo was demonstrated by PET imaging of a mouse model of myositis and a mouse model of pneumonia, showing accumulation of radiolabelled YbT in the tissues infected with FyuA-expressing bacteria and low signals in the negative control, Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which have been reported not to express FyuA. Nevertheless, [64Cu]Cu-YbT displayed accumulation in non-infected organs, such as liver, heart, lung, gastrointestinal tract and kidneys, which may hinder its usability for PET imaging, and thus further improvement of the compound is required before its further application98.

Petrik et al. reported that the previously mentioned DFO-B could also be used to image bacterial infections using PET. The authors radiolabelled DFO-B with gallium-68 and assessed that the resulting complex had in vitro properties suitable for PET imaging. They reported high uptake in several bacterial strains, including P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and S. agalactiae. They also showed that [68Ga]Ga-DFO-B has optimal pharmacokinetics in healthy animals, with exclusive renal excretion. The use of [68Ga]Ga-DFO-B for PET imaging of infections was evaluated in two animal models of infection: acute murine myositis and acute rat pneumonia49. Two clinical trials with [68Ga]Ga-DFO-B are currently ongoing. A phase I/IIa study to evaluate the safety, biodistribution, dosimetry, and preliminary diagnostic performance of [68Ga]Ga-DFO-B for PET imaging in patients with bacterial infections is being performed at the Medical University of Innsbruck in Austria (EudraCT Number 2020-002868-31). Another clinical trial, also focusing on [68Ga]Ga-DFO-B, is currently being conducted at King’s College London (NCT number: NCT05285072) to investigate the ability of the tracer to be taken up at sites of infection in patients with vascular grafts.

A recent evaluation by Bendova et al. has assessed the potential of the radiolabelled siderophore ornibactin (ORNB) for the imaging of infections caused by the Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC). The authors have successfully radiolabelled ORNB with gallium-68 with high radiochemical purity, resulting in a complex with favourable in vitro properties. They demonstrated its high in vitro specificity for BCC and optimal biodistribution in healthy mice, as it was exclusively excreted via the urinary system. In vivo PET/CT imaging of a murine model of myositis showed that [68Ga]Ga-ORNB can distinguish between B. multivorans and an E. coli infection or sterile inflammation. Furthermore, they demonstrated that [68Ga]Ga-ORNB can be used to image pneumonia in a rat model of lung infection induced by B. multivorans (Fig. 4)50.

Yellow arrows indicate the site of infection Previously published by Bendova et al.50.

Additionally, Dvorakova Bendova et al. investigated the potential of gallium-68-labelled siderophores for PET/CT imaging of Acinetobacter baumannii infections. They selected two siderophores—ferrioxamine E (FOX E) and previously mentioned FR—based on their favourable in vitro properties and significant uptake in A. baumannii for further evaluation. In healthy animals, [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-FR demonstrated slightly better biodistribution, with renal excretion as the primary clearance pathway. In contrast, [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-FOX E also showed minor uptake in the gastrointestinal tract. Both compounds successfully tracked A. baumannii infections in three distinct animal models: a murine model of myositis, a murine dorsal wound infection model, and a rat model of pneumonia. Quantitative analysis revealed that [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-FOX E exhibited slightly superior imaging results, with lower background signal and statistically significant differences between infected and control animals across all models85.

Akter et al. investigated the potential of using gallium-68-labelled hydroxamate siderophore schizokinen (SKN), produced by Bacillus megaterium, for the diagnosis of bacterial pathogens. They successfully radiolabelled SKN with gallium-68 and assessed that the resulting complex exhibited hydrophilic properties, short-term stability in human serum and uptake by several strains of bacteria: S. aureus, S. epidermidis, E. coli and P. aeruginosa. [68Ga]Ga-SKN also showed rapid blood clearance exclusively via the kidneys, as confirmed by both PET/CT imaging and ex vivo biodistribution studies. However, the urine analysis indicated only 22% stability of the complex. For future work, the authors plan to further evaluate the stability of [68Ga]Ga-SKN and explore its ability to detect infections in vivo51.

All natural siderophores discussed in this review are summarised in Table 1, together with key information on their microbial production, reported uptake by clinically relevant pathogens, tested radioisotopes, biodistribution profiles, and potential applications.

Radiolabelled siderophore derivates and artificial siderophores

Besides studying naturally occurring siderophores, researchers are also investigating their modifications and derivatives. One of the main aims of siderophore modification is to improve their pharmacological properties, including stability, sensitivity, and accuracy, in two main divergent directions. One approach is to extend their application to a wider range of bacterial species to develop a universal tool for bacterial imaging. The opposite approach seeks to design a pathogen-specific tool to differentiate specific bacterial species.

Ioppolo et al. attempted to develop a derivate of the previously mentioned DFO-B to slow down the clearance of [67Ga]-DFO, which, in their opinion, is cleared too rapidly in its natural state for imaging of infection. They succeeded in synthesising a library of [67Ga]-DFO derivates, some of which retained in vitro uptake in S. aureus cultures, while others, more lipophilic compounds, were not taken up by the bacterial culture. Subsequent biodistribution studies were performed with 4 compounds that had good uptake rates in vitro. Although they had higher uptake in infected tissues compared to non-infected tissues, they all showed high non-specific accumulation in the gall bladder, liver, and intestine, which significantly hinders their use for imaging of infection99.

A recent study published by Margeta et al. describes the preparation and gallium-68 labelling of a salmochelin derivate: [68Ga]Ga-RMA693. This derivate showed strain-dependent in vitro uptake by E. coli, accumulating only in the strains expressing the salmochelin receptor (IroN), which is often associated with pathogenic strains. They also showed, using in vivo PET/CT imaging and ex vivo gamma counting of mice with subcutaneous E. coli infection, that [68Ga]Ga-RMA693 accumulates in the tissue infected with E. coli expressing IroN. The group is continuing this work by exploring the sensitivity of the tracer and its applicability in different mouse models of infection in the currently ongoing studies100.

Jiang et al. synthesised deferoxamine dithiocarbamate (DFODTC) and successfully radiolabelled it with the [99mTc]TcN2+ complex. The [99mTc]TcN(DFODTC)2 complex showed high in vitro stability and promising in vitro uptake in S. aureus cultures. In an ex vivo biodistribution study in mice, the complex demonstrated moderate uptake in bacteria-infected muscle, as well as moderate uptake in turpentine-induced abscess. In addition, the complex showed increased accumulation in the healthy liver and intestine, which could potentially compromise the accuracy of imaging results. In vivo SPECT/CT imaging confirmed the ex vivo findings. While this tracer shows some potential, its uptake in the internal organs hinders its applicability to other infectious models and therefore calls for further development101.

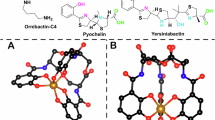

In a different study, six derivatives of the siderophore FOX E, previously shown to be a promising radiotracer for imaging of pulmonary aspergillosis46, were evaluated as potential gallium carriers for therapeutic and diagnostic purposes against bacterial pathogens. All ligands were labelled with gallium-68 with sufficient radiochemical purity, and the resulting complexes showed stability comparable to naturally occurring siderophores102. Variable levels of uptake were observed in S. aureus cultures, generally correlating with growth promotion studies performed on the same bacteria. These results show that FOX E derivates have a potential for medical applications. Based on this work, further studies were carried out to compare the uptake of modified siderophores. The study showed that altering the ring size of the compounds induced species-specific uptake. These results were further confirmed in vivo, in a rat model of pneumonia caused by A. fumigatus and in a mouse model of acute myositis caused by S. aureus (Fig. 5). These results demonstrate the possibility of selective targeting of pathogens by siderophore modification and open a way for further exploration of siderophore derivatization103.

A S. aureus infected mice 45 min after injection. Yellow arrows indicate the infection. B A. fumigatus infected rats 45 min after injection. The red arrow indicates the infection. Previously published by Mular et al., modified103.

Peukert et al. synthesised 11 cyclen-based artificial siderophores containing catecholate units for gallium-68 labelling and investigated their uptake in bacteria. The two most promising compounds, numbered 7 and 15, showed promising results suitable for PET imaging and were then used in animal studies. Both compounds showed rapid biodistribution with significant uptake in E. coli-induced myositis and rapid tracer washout from lipopolysaccharide-induced sterile inflammation in the control leg. In the future, these compounds have the potential to accommodate other metal cations or undergo further modification (optimisation of properties, induction of antibacterially active moieties)104.

Radiolabelled Sideromycins

Another primary goal of siderophore modification is to expand their potential applications beyond nuclear imaging. In such cases, siderophores are linked not only to a radioisotope but also to another functional molecule, such as antimicrobial moieties, to facilitate the import of the structure into the bacterial cell. Antimicrobial siderophores, called sideromycins, can be either naturally occurring (albomycin, salmycin) or artificial conjugates of siderophores with an antibiotic structure. This process, in which an antimicrobial molecule is transported directly into a bacterial cell thanks to its binding to a siderophore, is referred to as the “Trojan horse“ strategy, which may be a potential means of combating the global pandemic of antimicrobial resistance (Fig. 6)105. This fact opens up the possibility of using siderophores as theranostic tools, both for therapeutic and diagnostic purposes, which has inspired further studies. One of the earliest attempts to design such a molecule was made by Ferreira et al., who attached DOTAM (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic amide) scaffold to catechol-based moieties and incorporated ampicillin for antibacterial activities106. Research on sideromycins was further motivated by the fact that in October 2019, the FDA approved the use of Cefiderocol, a siderophore-cephalosporin conjugate, for the treatment of urinary tract infections, followed a year later by approval for use in patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia.

(1) The antimicrobial agent is conjugated to the siderophores, which can be (2) radiolabelled. These conjugates are then (3) actively transported into pathogens via iron uptake pathways. Once internalised, (4) the antimicrobial compound and the radioisotope are released, enabling simultaneous detection and elimination of the microorganism (a theranostic approach). This strategy exploits specific microbial iron acquisition systems, thereby increasing drug specificity and might potentially help to overcome common resistance mechanisms. Created in https://BioRender.com. Bendová, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/gm3sbxd.

Pandey et al. aimed to design a synthetic sideromycin by attaching the ciprofloxacin molecule to desferrichrome and gallium isotopes. The conjugate they designed displayed growth-inhibitory activity in several bacterial strains with high potency in E. coli. In addition, the authors radiolabelled these conjugates with gallium-67 and evaluated their biodistribution and stability in naive mice through ex vivo studies107.

Building on their previous study, Pandey et al. sought to improve the potency of their designed compounds by synthesising a second generation of albomycin-inspired ciprofloxacin-bearing molecule. The compound, designated Galbofloxacin, exceeded the potency of the parent ciprofloxacin in vitro, and the gallium-67-labelled Galbofloxacin showed renal clearance and active uptake in S. aureus-infected muscle that exceeded the uptake of [67Ga]Ga-citrate in ex vivo studies. The therapeutic study in Balb/c mice infected with S. aureus resulted in survival and complete resolution of infection in mice treated with Galbofloxacin, whereas the infection was fatal after 24 h in mice treated with the same molar dose of ciprofloxacin. This research practically demonstrates the dual applicability of siderophores for theranostic purposes: on the one hand, the siderophore facilitates the transportation of antimicrobial compounds for the treatment of infection in the manner of the aforementioned Trojan horse strategy, but it also enables the diagnosis of infection thanks to its chelation of gallium-67108.

Sanderson et al. took a similar approach by designing a ciprofloxacin-salmochelin S4-based molecule. The main aim of the design was to selectively target bacteria that express salmochelin transporters and evade the mammalian immune response to the molecule. However, the resulting compound showed significantly lower antimicrobial activity than ciprofloxacin in E. coli expressing the relevant transporter. The authors radiolabelled the compound with gallium-67 in high yields and further tested its bacterial uptake. They confirmed their suspicion that the compound was not significantly taken by the bacteria tested and decided to focus their future studies on optimising the active conjugate transport109.

Radiolabelled siderophores beyond nuclear imaging of bacterial infections

Although this work focuses on the use of siderophores for nuclear imaging of infection, it is important to note that their potential extends beyond this field. Since some siderophores can be conjugated with targeting molecules, their innate ability to form stable complexes with radiometals makes them versatile bifunctional chelators for additional applications. At first, the siderophore used in these cases was DFO-B, most commonly labelled with gallium-68, gallium-67, or zirconium-89 and coupled with targeting molecules, such as fibrinogen, albumin, monoclonal antibodies, nanobodies, Octreotide, or folate110,111,112,113,114,115. Subsequently, fusarinine C (FSC) was also used as a bifunctional chelator to couple radioisotopes (e.g., Ga-68 and Zr-89) with RGD peptide for integrin or minigastrin for cholecystokinin B receptor targeting116,117,118,119,120. All of these examples and other historical conjugates are discussed in detail in previously published articles52,121.

In a more recent proof-of-concept study inspired by previous works, Summer et al. explored a pre-targeted imaging approach that combined optical imaging and PET. They also used the FSC scaffold for its ability to be readily radiolabeled with gallium-68. The FSC was conjugated with various fluorophores for optical imaging, as well as tetrazine moieties that selectively bind to the pretargeting agent trans-cyclooctene (TCO). In biodistribution studies conducted in mice pretreated with a bone-targeting TCO conjugate, the imaging agent accumulated in bone tissue and was clearly visualised by both PET and optical imaging, which was not observed in control animals (Fig. 7). This study clearly demonstrates the versatility of siderophores and highlights their potential application in pretargeted imaging strategies122.

Mice receiving bone-targeting alendronate alone (left column) or alendronate-TCO (right column), PET/CT images: transverse slices (top) and sagittal slices (middle), yellow arrows indicate uptake in joints and spine, white arrow indicates the bladder. Bottom image: Optical image of excised bones of the lower limbs. Both PET and OI indicate higher accumulation in the bone of alendronate-TCO pre-treated mice as compared to controls. Previously published by Summer et al.122.

In addition, FSC was recently used in a study that again focused on targeting cholecystokinin receptors. In this study, Gariglio et al. compared two chelating scaffolds, triazacyclononane-phosphinic acid (TRAP) and FSC, which were coupled to fluorophores and cholecystokinin binding motifs. They observed specific accumulation in tumour-bearing mice for both compounds on both PET and optical imaging, although the FSC-based molecule had more favourable biodistribution properties and higher tumour uptake123.

Recent research has also explored other siderophores for their chelating properties. A study by Koller et al. was inspired by siderophore-antibiotic conjugates and provides an example of an interesting alternative to the use of siderophores. The authors combined the catechol moiety from enterobactin (ENT) with a prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), resulting in a new compound called ENT-DUPA. They successfully radiolabelled their new compound with titanium-45 and demonstrated that in tumour-bearing mice bearing both PSMA-positive and PSMA-negative tumours, [⁴⁵Ti]Ti-ENT-DUPA selectively accumulated in the PSMA-positive tumours and was mainly excreted via the kidneys124.

Interesting utilisation of siderophores was reported by Pfister et al., which further demonstrates their potential for combined imaging and theranostic applications. The team modified triacetylfusarinine C (TAFC) with several fluorescent dyes for optical imaging and labelled it with gallium-68 for PET imaging. Two of these derivates facilitated µPET/CT imaging of lung regions infected by invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, with the infected areas corresponding to lesions visualised by ex vivo optical imaging125,126. Additionally, the team modified the TAFC siderophore by conjugating it with various antifungal molecules. Susceptibility tests indicated potential fungal growth inhibition, and biodistribution studies in rats with pulmonary aspergillosis showed uptake of all conjugates in the infected lungs. However, in vivo studies assessing therapeutic effects have not yet been conducted127,128.

On the topic of Aspergillus fumigatus, Misslinger et al. showed that the bacterially produced DFO-B, mentioned earlier, can be used for imaging of this fungal pathogen, as they demonstrated in a rat model of pulmonary aspergillosis129.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Ongoing research into radiolabelled siderophores for bacterial imaging has laid a solid foundation for future advances in targeted diagnostics. The development of these compounds holds the promise of more effective and specific imaging techniques that could significantly improve the diagnostic process for bacterial infections. In addition, the possibility of using these compounds for therapeutic purposes, such as targeted antibiotic delivery or via radionuclide therapy using suitable radionuclides130, represents an innovative direction in the fight against antimicrobial resistance. However, despite significant progress in radiolabelled siderophore research, their full potential has not yet been fully explored, particularly in the context of clinical applications, with a limited number of ongoing clinical trials involving these compounds.

Prospects in this field are promising, with several areas for exploration. One important direction is to further optimise the pharmacokinetic profiles of siderophore radiotracers to enhance their efficacy and reduce potential side effects. The development of new siderophore analogues that can improve binding affinity and uptake by bacterial cells is crucial. Additionally, expanding the range of pathogens that can be targeted by this imaging technique will be essential to broaden the clinical applicability of radiolabelled siderophores.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1204–1222 (2020).

GBD 2019 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 400, 2221–2248 (2022).

O’Neill, J. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. in Review on Antimicrobial Resistance https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf (2014).

Llor, C. & Bjerrum, L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther. Adv. Drug Safety 229–241 https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098614554919 (2014).

Cals, J. W. L., Butler, C. C., Hopstaken, R. M., Hood, K. & Dinant, G. J. Effect of point of care testing for C reactive protein and training in communication skills on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster randomised trial. BMJ 338, 1112–1115 (2009).

Sy, R., Rothman, R. E. & Yang, S. PCR-based diagnostics for infectious diseases: uses, limitations, and future applications in acute-care settings. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4, 337–348 (2004).

Loderstädt, U., Hagen, R. M., Hahn, A. & Frickmann, H. New developments in PCR-based diagnostics for bacterial pathogens causing gastrointestinal infections—a narrative mini-review on challenges in the tropics. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 6 https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6020096 (2021).

Eldin, C., Parola, P. & Raoult, D. Limitations of diagnostic tests for bacterial infections. Med. Mal. Infect. 3, 98–101 (2019).

FIGDOR, D. & GULABIVALA, K. Survival against the odds: microbiology of root canals associated with post-treatment disease. Endod. Top. 18, 62–77 (2008).

Rothe, K. et al. Evaluation of a multiplex PCR screening approach to identify community-acquired bacterial co-infections in COVID-19: a multicenter prospective cohort study of the German competence network of community-acquired pneumonia (CAPNETZ). Infection 49, 1299–1306 (2021).

Singh, S. B. et al. Is imaging bacteria with PET a realistic option or an illusion? Diagnostics 7 https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13071231 (2023).

Diaz, L. A. et al. Imaging of musculoskeletal bacterial infections by [124I]FIAU-PET/CT. PLoS ONE 2 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001007 (2007).

Berton, D. C., Kalil, A. C. & Teixeira, P. J. Z. Quantitative versus qualitative cultures of respiratory secretions for clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated Pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006482.pub4 (2014).

Zhuang, H. & Alavi, A. 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomographic imaging in the detection and monitoring of infection and inflammation. Semin. Nucl. Med. 1, 47–59 (2002).

Lavender, J. P., Lowe, J., Barker, J. R., Burn, J. I. & Chaudhri, M. A. Gallium 67 citrate scanning in neoplastic and inflammatory lesions. Br. J. Radiol. 44, 361–366 (1971).

Littenberg, R. L. et al. Gallium-67 for localization of septic lesions. Ann. Intern. Med. 79, 403–406 (1973).

Culverwell, A. D., Scarsbrook, A. F. & Chowdhury, F. U. False-positive uptake on 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron-emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) in oncological imaging. Clin. Radiol. 66, 366–382 (2011).

De Vries, E. F. J., Roca, M., Jamar, F., Israel, O. & Signore, A. Guidelines for the labelling of leucocytes with 99mTc-HMPAO. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 842–848 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-010-1394-4 (2010).

Sarrazin, J.-F., Philippon, F., Trottier, M. & Tessier, M. Role of radionuclide imaging for diagnosis of device and prosthetic valve infections. World J. Cardiol. 8, 534 (2016).

Ordonez, A. A. & Jain, S. K. Pathogen-specific bacterial imaging in nuclear medicine. Semin. Nucl. Med. 182–194 https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2017.11.003 (2018).

Lai, J., Wang, B., Petrik, M., Beziere, N. & Hammoud, D. A. Radiotracer development for fungal-specific imaging: past, present, and future. J. Infect. Dis. 228, S259–S269 (2023).

Davidson, C. Q., Phenix, C. P., Tai, T. C., Khaper, N. & Lees, S. J. Searching for novel PET radiotracers: imaging cardiac perfusion, metabolism and inflammation. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 8, 200–227 (2018).

Rubin, R. H. et al. Radiolabeled, nonspecific, polyclonal human immunoglobulin. J. Nucl. Med. 30, 389–389 (1989).

Malpani, B. L., Kadival, G. V. & Samuel, A. M. Radioimmunoscintigraphic approach for the in vivo detection of tuberculomas-a preliminary study in a rabbit model. Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instrum. 19, 45–53 (1992).

Sierra, J. M. et al. Accumulation of 99mTc-ciprofloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 2691–2692 (2008).

Sellmyer, M. A. et al. Bacterial infection imaging with [18F]fluoropropyl-trimethoprim. PNAS 114, 8372–8377 (2017).

Spoelstra, G. B. et al. Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of novel 18F-vancomycin-based tracers for the detection of bacterial infections using positron emission tomography. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 51, 2583–2596 (2024).

Welling, M. M. et al. Radiochemical and biological characteristics of 99mTc-UBI 29-41 for imaging of bacterial infections. Nucl. Med. Biol. 29, 413–422 (2002).

Sarda-Mantel, L. et al. Evaluation of 99mTc-UBI 29-41 scintigraphy for specific detection of experimental Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infections. Eur. J. Nucl. Med Mol. Imaging 34, 1302–1309 (2007).

Akhtar, M. S., Imran, M. B., Nadeem, M. A. & Shahid, A. Antimicrobial peptides as infection imaging agents: better than radiolabeled antibiotics. Int. J. Peptides https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/965238 (2012).

Baldoni, D. et al. Evaluation of a novel Tc-99m labelled vitamin B12 derivative for targeting Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and in an experimental foreign-body infection model. Mol. Imaging Biol. 17, 829–837 (2015).

Lazzeri, E. et al. Scintigraphic imaging of vertebral osteomyelitis with 111 in-biotin. SPINE 33 https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816960c9 (2008).

Chen, L. et al. 99mTc-MORF oligomers specific for bacterial ribosomal RNA as potential specific infection imaging agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21, 6523–6530 (2013).

Ferreira, I. M. et al. Detection of bacterial infection by a technetium-99m-labeled peptidoglycan aptamer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 93, 931–938 (2017).

Rusckowski, M., Gupta, S., Liu, G., Dou, S. & Hnatowich, D. J. Investigation of four 99mTc-labeled Bacteriophages for infection-specific imaging. Nucl. Med. Biol. 35, 433–440 (2008).

Weinstein, E. A. et al. Imaging enterobacteriaceae infection in vivo with 18F-fluorodeoxysorbitol positron emission tomography. Sci. Transl. Med. 6 https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3009815 (2014).

Gowrishankar, G. et al. Investigation of 6-[18F]-fluoromaltose as a novel PET tracer for imaging bacterial infection. PLoS ONE 9 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107951 (2014).

Pullambhatla, M. et al. 125I]FIAU Imaging in a preclinical model of lung infection: quantification of bacterial load. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2, 260–270 (2012).

Petrik, M. et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of selected 68Ga-siderophores for infection imaging. Nucl. Med. Biol. 39, 361–369 (2012).

van Oosten, M. et al. Targeted imaging of bacterial infections: advances, hurdles and hopes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 892–916 (2015).

Martínez, M. E. et al. New radiosynthesis of 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoroacetamido-d-glucopyranose and its evaluation as a bacterial infections imaging agent. Nucl. Med. Biol. 38, 807–817 (2011).

Neumann, K. D. et al. Imaging active infection in vivo using D-amino acid derived PET radiotracers. Sci. Rep. 7 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08415-x (2017).

Lee, S. H. et al. Imaging the bacterial cell wall using N-acetyl muramic acid-derived positron emission tomography radiotracers. ACS Sens. 8, 4554–4565 (2023).

Chandra, R., Plerno, C. & Braunstein, P. 111In desferal: a new radiopharmaceutical for abscess detection. Radiology 128, 679–699 (1978).

Petrik, M. et al. 68Ga-siderophores for PET imaging of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: proof of principle. J. Nucl. Med. 51, 639–645 (2010).

Petrik, M. et al. Preclinical evaluation of two 68Ga-siderophores as potential radiopharmaceuticals for Aspergillus fumigatus infection imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 39, 1175–1183 (2012).

Petrik, M. et al. In vitro and in vivo comparison of selected Ga-68 and Zr-89 labelled siderophores. Mol. Imaging Biol. 18, 344–352 (2016).

Petrik, M. et al. Imaging of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa infection with Ga-68 labelled pyoverdine for positron emission tomography. Sci. Rep. 8, 15698 (2018).

Petrik, M. et al. 68Ga-labelled desferrioxamine-b for bacterial infection imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 48, 372–382 (2021).

Bendova, K. et al. [68Ga]Ga-ornibactin for Burkholderia cepacia complex infection imaging using positron emission tomography. J. Med. Chem. 66, 7584–7593 (2023).

Akter, A. et al. [68Ga]Ga-schizokinen, a potential radiotracer for selective bacterial infection imaging. ACS Infect. Dis. 10, 2615–2622 (2024).

Petrik, M., Zhai, C., Haas, H. & Decristoforo, C. Siderophores for molecular imaging applications. Clin. Transl. Imaging 5, 15–27 (2017).

Petrik, M., Pfister, J., Misslinger, M., Decristoforo, C. & Haas, H. Siderophore-based molecular imaging of fungal and bacterial infections—current status and future perspectives. J. Fungi 6 https://doi.org/10.3390/jof6020073 (2020).

Litwin, C. M. & Calderwood, S. B. Role of iron in regulation of virulence genes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 6, 137–149 (1993).

Page, M. G. P. The role of iron and siderophores in infection, and the development of siderophore antibiotics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 69, S529–S537 (2019).

Wilson, B. R., Bogdan, A. R., Miyazawa, M., Hashimoto, K. & Tsuji, Y. Siderophores in iron metabolism: from mechanism to therapy potential. Trends Mol. Med. 12, 1077–1090 (2016).

Kronstad, J. W. & Caza, M. Shared and distinct mechanisms of iron acquisition by bacterial and fungal pathogens of humans. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2013.00080 (2013).

Krewulak, K. D. & Vogel, H. J. Structural biology of bacterial iron uptake. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1778, 1781–1804 (2008).

He, R. et al. SIDERITE: unveiling hidden siderophore diversity in the chemical space through digital exploration. iMeta https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.192 (2024).

Timofeeva, A. M., Galyamova, M. R. & Sedykh, S. E. Bacterial siderophores: classification, biosynthesis, perspectives of use in agriculture. Plants 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11223065 (2022).

Krasulova, K. et al. Preclinical characterisation of gallium-68 labeled ferrichrome siderophore stereoisomers for PET imaging applications. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 9 https://doi.org/10.1186/s41181-024-00249-z (2024).

Barry, S. M. & Challis, G. L. Recent advances in siderophore biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 13, 205–215 (2009).

Zhou, Z., Lai, J. R. & Walsh, C. T. Directed evolution of aryl carrier proteins in the enterobactin synthetase. PNAS 104 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705122104 (2007).

Patel, P., Song, L. & Challis, G. L. Distinct extracytoplasmic siderophore binding proteins recognize ferrioxamines and ferricoelichelin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Biochemistry 49, 8033–8042 (2010).

Puja, H., Mislin, G. L. A. & Rigouin, C. Engineering siderophore biosynthesis and regulation pathways to increase diversity and availability. Biomolecules 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13060959 (2023).

Klebba, P. E. et al. Iron acquisition systems of Gram-negative bacterial pathogens define TonB-dependent pathways to novel antibiotics. Chem. Rev. 12, 5193–5239 (2021).

Vijay, K., Shibasini, M., Sivasakthivelan, P. & Kavitha, T. Microbial siderophores as molecular shuttles for metal cations: sources, sinks and application perspectives. Archives Microbiol. 205 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-023-03644-3 (2023).

Chao, A., Sieminski, P. J., Owens, C. P. & Goulding, C. W. Iron acquisition in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem. Rev. 119, 1193–1220 (2019).

Rocha, E. R. & Krykunivsky, A. S. Anaerobic utilization of Fe(III)-xenosiderophores among bacteroides species and the distinct assimilation of Fe(III)-ferrichrome by bacteroides fragilis within the genus. MicrobiologyOpen 6 https://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.479 (2017).

Chan, D. C. K. & Burrows, L. L. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa FpvB is a high-affinity transporter for xenosiderophores ferrichrome and ferrioxamine B. mBio 2023, 14 https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.03149-22 (2023).

Hussein, S. M., Sofoluwe, A., Paleja, A. & Duhme-Klair, A., Thomas, M. S. Identification of a system for hydroxamate xenosiderophore mediated iron transport in Burkholderia Cenocepacia. Microbiology 170 https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.001425 (2024).

Lange, M. D. et al. Proteome analysis of virulent Aeromonas hydrophila reveals the upregulation of iron acquisition systems in the presence of a xenosiderophore. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 367 https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnaa169 (2020).

Kumar, R., Singh, A., & Srivastava, A. Xenosiderophores: bridging the gap in microbial iron acquisition strategies. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 41 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-025-04287-w (2025).

Endicott, N. P., Rivera, G. S. M., Yang, J. & Wencewicz, T. A. Emergence of ferrichelatase activity in a siderophore-binding protein supports an iron shuttle in bacteria. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 493–506 (2020).

Karpowich, N. et al. Crystal structures of the MJ1267 ATP binding cassette reveal an induced-fit effect at the ATPase Active Site of an ABC Transporter. Structure 9, 571–586 (2001).

Klebba, P. E. ROSET model of tonB action in gram-negative bacterial iron acquisition. J. Bacteriol. 198, 1013–1021 (2016).

Schalk, I. J. & Guillon, L. Fate of ferrisiderophores after import across bacterial outer membranes: different iron release strategies are observed in the cytoplasm or periplasm depending on the siderophore pathways. Amino Acids 44, 1267–1277 (2013).

Chu, B. C. H. & Vogel, H. J. A structural and functional analysis of type III periplasmic and substrate binding proteins: their role in bacterial siderophore and heme transport. Biol. Chem. 1778, 39–52 (2011).

Delepelaire, P. Bacterial ABC transporters of iron containing compounds. Res. Microbiol. 170, 345–357 (2019).

Emery, T. & Hoffer, P. B. Siderophore-mediated mechanism of gallium uptake demonstrated in the microorganism Ustilago sphaerogena. J. Nucl. Med. 21, 935–939 (1980).

Moerlein, S. M., Welch, M. J., Raymond, K. N. & Weitl, F. L. Tricatecholamide analogs of enterobactin as gallium-and indium-binding radiopharmaceuticals. J. Nucl. Med. 22, 710–719 (1981).

Thakur, M. L. Gallium-67 and Indium-111 radiopharmaceuticals. Int. J. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 28, 183–201 (1977).

Manapragada, P. et al. Gallium 67 SPECT as a treatment monitoring tool in temporal bone and skull base osteomyelitis. J. Nucl. Med. 55, 1973 (2014).

Johnson, H., John, J., Benjamin, J. & Hephzibah, J. A comparative case study between gallium-67 citrate scintigraphy and gallium-68 citrate positron emission tomography-computed tomography in bone infection. Indian J. Nucl. Med. 37, 271–273 (2022).

Dvorakova Bendova, K. et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of Acinetobacter baumannii infection: comparison of gallium-68 labeled siderophores. ACS Infect. Dis. 11, 917–928 (2025).

Carter, L. M. et al. The Impact of positron range on PET resolution, evaluated with phantoms and PHITS Monte Carlo simulations for conventional and non-conventional radionuclides. Mol. Imaging Biol. 22, 73–84 (2020).

Gavriilidis, P., Koole, M., Annunziata, S., Mottaghy, F. M. & Wierts, R. Positron range corrections and denoising techniques for gallium-68 PET imaging: a literature review. Diagnostics 1 https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12102335 (2022).

Kleynhans, J., Ebenhan, T. & Sathekge, M. M. Expanding role for gallium-68 PET imaging in oncology. Semin. Nucl. Med. 11, 778–791 (2024).

De Feo, M. S. et al. 89Zr-PET imaging in humans: a systematic review. Clin. Transl. Imaging 2, 23–36 (2022).

Takeuchi, Y. et al. Synthesis of acinetobactin. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 58, 1552–1553 (2010).

Ankenbauer, R. G., Toyokuni, T., Staley, A., Rinehart, K. L. & Cox, C. D. Synthesis and biological activity of pyochelin, a siderophore of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 170, 5344–5351 (1980).

Fuhrmann, J. J. Purification of siderophores from cultures of fluorescent pseudomonas spp by ion-exchange chromatography. Soil Biol. Biochem. 23, 1111–1113 (1991).

Penwell, W. F. & Actis, L. A. Isolation and characterization of the acinetobactin and baumannoferrin siderophores produced by Acinetobacter baumannii. Methods Mol. Biol. 1946, 259–270 (2019).

Neilands, J. B. Methodology of Siderophores. in Structure and Bonding Vol. 58 (eds Sainz, L. G.-H., et al) 2–23 (Berkeley, 1984).

Garzón-Posse, F., Quevedo-Acosta, Y., Mahecha-Mahecha, C. & Acosta-Guzmán, P. Recent progress in the synthesis of naturally occurring siderophores. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 10, 7747–7769 (2019).

Soares, E. V. Perspective on the biotechnological production of bacterial siderophores and their use. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 6, 3985–4004 (2022).

Ullah, I. & Lang, M. Key players in the regulation of iron homeostasis at the host-pathogen interface. Front. Immunol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1279826 (2023).

Siddiqui, N. A.; et al. Leveraging copper import by yersiniabactin siderophore system for targeted PET imaging of bacteria. JCI Insight 6 https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.144880 (2021).

Ioppolo, J. A. et al. 67Ga-labeled deferoxamine derivatives for imaging bacterial infection: preparation and screening of functionalized siderophore complexes. Nucl. Med. Biol. 52, 32–41 (2017).

Margeta, R. et al. A novel radiolabelled salmochelin derivative for bacteria-specific PET imaging: synthesis, radiolabelling and evaluation. Chem. Commun. 60, 3507–3510 (2024).

Jiang, Y. et al. Radiolabeling and evaluation of a novel [99mTcN]2+ complex with deferoxamine dithiocarbamate as a potential agent for bacterial infection imaging. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2021.128102 (2021).

Mular, A. et al. Cyclic analogs of desferrioxamine E siderophore for 68Ga nuclear imaging: coordination chemistry and biological activity in Staphylococcus aureus. Inorg. Chem. 60, 17846–17857 (2021).

Mular, A. et al. Biomimetic analogues of the desferrioxamine e siderophore for PET imaging of invasive aspergillosis: targeting properties and species specificity. J. Med. Chem. 67, 12143–12154 (2024).

Peukert, C. et al. Optimization of artificial siderophores as 68ga-complexed pet tracers for in vivo imaging of bacterial infections. J. Med. Chem. 64, 12359–12378 (2021).

Rayner, B., Verderosa, A. D., Ferro, V. & Blaskovich, M. A. T. Siderophore conjugates to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. RSC Med. Chem. 5, 800–822 (2023).

Ferreira, K. et al. Multivalente siderophor-DOTAM-konjugate als Theranostika zur Visualisierung und Behandlung bakterieller Infektionen. Angew. Chem. 129, 8384–8389 (2017).

Pandey, A. et al. Theranostic gallium siderophore ciprofloxacin conjugate with broad spectrum antibiotic potency. J. Med. Chem. 62, 9947–9960 (2019).

Pandey, A., Śmiłowicz, D. & Boros, E. Galbofloxacin: a xenometal-antibiotic with potentin vitroandin vivoefficacy againstS. Aureus. Chem. Sci. 12, 14546–14556 (2021).

Sanderson, T. J. et al. A Salmochelin S4-inspired ciprofloxacin Trojan horse conjugate. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 2532–2541 (2020).

Ohmomo, Y. et al. 67Ga-labeled human fibrinogen: a new promising thrombus imaging agent. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 7, 458–461 (1982).

Ohmomo, Y. et al. Deferoxamine, a promising bifunctional chelating agent for labeling proteins with gallium: Ga-67 DF-HSA: concise communication. J. Nucl. Med. 23, 909–914 (1982).

Koizumi, M. et al. 67Ga-Labeled antibodies for immunoscintigraphy and evaluation of tumor of drug-antibody conjugates in mice. Cancer Res. 48, 1189–1194 (1988).

Vosjan, M. J. W. D. et al. Facile labelling of an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor nanobody with 68Ga via a novel bifunctional desferal chelate for immuno-PET. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 38, 753–763 (2011).

Wang, S., Lee, R. J., Mathias, C. J., Green, M. A. & Low, P. S. Synthesis, purification, and tumor cell uptake of 67 Ga-deferoxamine-folate, a potential radiopharmaceutical for tumor imaging. Bioconjugate Chem. 7, 56–62 (1996).

Smith-Jones, P. M. et al. Gallium-67/gallium-68-[DFO]-octreotide - a potential radiopharmaceutical for PET imaging of somatostatin receptor-positive tumors: synthesis and radiolabeling in vitro and preliminary in vivo studies. J. Nucl. Med. 35, 317–325 (1994).

Kaeopookum, P. et al. Comparison of 68Ga-labeled rgd mono- and multimers based on a clickable siderophore-based scaffold. Nucl. Med. Biol. 78, 1–10 (2019).

Zhai, C. et al. Comparison of Ga-68-labeled fusarinine C-based multivalent RGD conjugates and [68Ga]NODAGA-RGD—in vivo imaging studies in human xenograft tumors. Mol. Imaging Biol. 18, 758–767 (2016).

Zhai, C. et al. Rational design, synthesis and preliminary evaluation of novel fusarinine C-based chelators for radiolabeling with zirconium-89. Biomolecules 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9030091 (2019).

Summer, D. et al. Multimerization results in formation of re-bindable metabolites: a proof of concept study with FSC-based minigastrin imaging probes targeting CCK2R expression. PLoS ONE 2018, 13 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201224 (2018).

Summer, D. et al. Exploiting the concept of multivalency with 68Ga- and 89Zr-labelled fusarinine C-minigastrin bioconjugates for targeting CCK2R expression. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3171794 (2018).

Wei, W. et al. ImmunoPET: concept, design, and applications. Chem. Rev. J. 120, 3787–3851 (2020).

Summer, D. et al. Hybrid imaging agents for pretargeting applications based on fusarinine C- proof of concept. Molecules 25, 2123 (2020).

Gariglio, G. et al. Comparison of two chelator scaffolds as basis for cholecystokinin-2 receptor targeting bimodal imaging probes. Pharmaceuticals 17 https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17121569 (2024).

Koller, A. J. et al. “Off-label use” of the siderophore enterobactin enables targeted imaging of cancer with radioactive Ti(IV). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63 https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202319578 (2024).

Pfister, J. et al. Hybrid imaging of Aspergillus fumigatus pulmonary infection with fluorescent, 68Ga-labelled siderophores. Biomolecules 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10020168 (2020).

Kaeopookum, P. et al. Modifying the siderophore triacetylfusarinine C for molecular imaging of fungal infection. Mol. Imaging Biol. 21, 1097–1106 (2019).

Pfister, J. et al. Siderophore Scaffold as carrier for antifungal peptides in therapy of Aspergillus Fumigatus infections. J. Fungi 6, 1–14 (2020).

Pfister, J. et al. Antifungal siderophore conjugates for theranostic applications in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis using low-molecular tafc scaffolds. J. Fungi 7 https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7070558 (2021).

Misslinger, M. et al. Desferrioxamine B-mediated pre-clinical in vivo imaging of infection by the mold fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Fungi 2021, 7 https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7090734 (2021).

Dadachova, E. Future vistas in alpha therapy of infectious diseases. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 50, S49–S52 (2019).

Davidov, Y., Tejman-Yarden, N., Robinson, A., Rahav, G. & Nissan, I. Enterobactin and salmochelin s4 inhibit the growth of Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 15 https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2025.1456046 (2025).

Akter, A. et al. Radiotracers for in situ infection imaging: experimental considerations for in vitro microbial uptake of gallium-68-labeled siderophores. Diag. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 110 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2024 (2024).

Winkelmann, G. & Drechsel, H. Microbial siderophores. in Biotechnology: Products of Secondary Metabolism (eds Rehm, J., & Reed, G.) 200–246 (VCH, 1997).

Zhu, W. et al. Xenosiderophore utilization promotes bacteroides thetaiotaomicron resilience during colitis. Cell Host Microbe 27, 376–388.e8 (2020).

Perry, R. D. & Fetherston, J. D. Yersiniabactin iron uptake: mechanisms and role in yersinia pestis pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 13, 808–817 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by National Institute of Virology and Bacteriology (Programme EXCELES, ID project no. LX22NPO5103)−funded by the European Union−Next Generation EU; the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (project EATRIS-CZ LM2023053), the Internal Grant Agency of Palacký University (project IGA LF IGA_LF_2025_006) and the Czech Science Foundation, grant number 24-14579L. The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.D.B. wrote the manuscript; M.P., K.K., B.N., and M.H. reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dvorakova Bendova, K., Krasulova, K., Neuzilova, B. et al. New insights into radiolabelled siderophores for molecular imaging of bacterial infections. npj Imaging 3, 63 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44303-025-00126-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44303-025-00126-7