Abstract

Magnetic resonance microscopy (MRM) produces high spatial resolution proton images of biological tissues, plants, and porous media, revealing microstructural details and contrast unattainable by other means. A major challenge in MRM is the low signal-to-noise ratio at high spatial resolutions, as smaller voxels produce smaller MR signals. This necessitates the use of highly sensitive microcoils, high-performance gradient systems, and high magnetic fields. Here, we present a step-by-step prescription for fabricating a cost-effective, flexible microimaging probe system compatible with horizontal bore high-field MRI systems. We demonstrate performance at 15.2 T by acquiring high-resolution (15 μm isotropic voxels) images of ex vivo mouse spinal cord (gray matter SNR 38; 46 h scan) and hippocampus (SNR 67; 45 h scan), clearly resolving microstructural features. Shorter imaging times are possible using compressed sampling. The flexible probe design supports solenoid diameters ranging from < 1 mm up to 10 mm in diameter, offering flexibility for imaging a variety of biological samples at high resolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic resonance microscopy (MRM) is a subset of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques designed to image aqueous samples with sub-100 μm isotropic spatial resolution1,2. MRM has been previously used to reveal fine microstructural details in various applications, including biological cells3,4, phantoms5,6,7,8, insects9, embryos10, ex vivo plant7,8,11,12,13, and animal tissues14,15,16,17.

One of the major limitations of MRM is the inherently low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) due to small voxel volumes, which contain a low number of spins that produce MR signals. The SNR depends on several key factors, including voxel volume, number of signals averaged, number of sampling points (\({N}_{x}\), \({N}_{y}\), and \({N}_{z}\)) in each direction, effective spin density (allowing for relaxation effects), temperature of the sample, temperature of the coil and electronics in the receive chain, receiver bandwidth, Larmor frequency (\({\omega }_{0}\) which depends on the \({B}_{0}\) field strength), receiver coil sensitivity (\({B}_{1}^{-}\)), and losses from the coil, sample, and receive chain. To compensate for the reduced SNR at high spatial resolution, repeated acquisitions are often performed. Because noise is uncorrelated in these repeated acquisitions, signal averaging is performed to reduce the standard deviation of the noise, increasing the SNR by \(\sqrt{{N}_{{acq}}}\). However, the repeated acquisitions come at a cost in terms of scan time \({T}_{{scan}}={N}_{{acq}}{N}_{y}{N}_{z}{TR}\) (assuming 3D spatial frequency data are collected in Cartesian format in k-space, where \({TR}\) = repetition time, and \({N}_{y}\) and \({N}_{z}\) are the number of phase encode steps in two dimensions). The number of readout points \({N}_{x}\), does not factor into the scan time because all readout points are collected within a single \({TR}\).

There are several potential ways to improve the SNR in MRM. The first is the use of a very high \({B}_{0}\) field strength since signal increases with Larmor frequency (\({\omega }_{0}\)) as \({\omega }_{0}^{2}\)18,19. However, SNR increases by only \({{\omega }_{0}}^{\frac{7}{4}}\) at high frequency in small samples when the resistance and the skin depth of the coil conductor are taken into consideration18,20. For larger samples, the dependence further decreases to just \({\omega }_{0}\) at high frequencies21, reducing the impact of using higher \({B}_{0}\) field strengths. The second area of SNR improvement could be to reduce the overall effective resistance \({R}_{{eff}}\), which depends on losses introduced by the coil, lead wires, capacitors, sample, and receiver circuit. The coil loss can be minimized by using miniaturized microcoils21,22,23. Lead wire losses, though typically smaller, can accumulate if excess wire length is used, so minimizing lead length is important. Capacitor losses are determined by their quality factor (Q) at the operating frequency; using high-Q capacitors reduces this contribution. Sample loss—arising from both magnetic (eddy-current) and dielectric losses in conductive tissues—often dominates at high frequency and increases with tissue conductivity and sample size. By contrast, radiation noise represents power carried away as propagating electromagnetic waves once coil dimensions approach the RF wavelength. For electrically small solenoids such as those employed here (millimeter-scale diameters at 650 MHz, λ~46 cm), the radiation resistance is orders of magnitude smaller than the coil’s resistive loss and negligible relative to sample noise. Optimizing coil geometry can reduce coil and sample contributions21, while the inherently higher receive sensitivity (\({B}_{1}^{-}\)) of microcoils further enhances SNR. Lastly, the SNR can be improved significantly by reducing the effective temperature \({T}_{{eff}}\) of the coil and the circuit components, decreasing noise contributions to MR signals. Several attempts have been made to exploit the temperature dependence of SNR using liquid helium-cooled24 and liquid nitrogen-cooled radiofrequency circuits25, also referred to as cryocoils.

The early development of micro-imaging coils began in 1986 when Aguayo et al. 3 first demonstrated MRM at sub-100 μm isotropic resolution. Since then, advances using custom-built MR microscopy probes have progressively been used to acquire higher spatial resolution, with reported voxel sizes down to 1 × 1 × 75 μm³ or isotropic 3.7 × 3.3 × 3.3 μm³ 7,26. Commercial micro-imaging coils have also enabled resolutions as fine as 3–7 μm isotropic across various biological and synthetic samples6,8,12,13,14,17. Recently, dynamic nuclear polarization at extremely low temperature has achieved even higher isotropic resolutions of 2.8 μm27. However, despite these advancements, most high-resolution micro-imaging probes remain optimized for vertical bore MRI systems, leaving horizontal bore preclinical MRI systems—widely used in research—without affordable, high-SNR micro-imaging coil solutions. While in principle coils designed for vertical-bore systems could be adapted, differences in bore geometry, gradient assembly dimensions, tune/match accessibility, and sample orientation relative to gravity in susceptibility-matched designs typically require purpose-built coil housing for horizontal bore configurations. Additionally, commercially available cryocoils designed for horizontal bore systems, while more SNR-efficient than traditional coils, are expensive (>$100,000), less flexible, primarily designed for larger specimens (e.g., mice) and require substantial hardware modifications. Moreover, recent comparisons indicate that microcoils can outperform larger cryoprobes in terms of SNR when imaging smaller samples28.

In this work, we aim to provide a comprehensive, step-by-step guide, with a list of required components and currently available vendor information, to develop a cost-effective, flexible micro-imaging probe system that is compatible with horizontal bore MRI scanners. This development meets the need for microimaging probes for use with the large number of horizontal bore high-field MRI systems (7 to 15.2 T) in current preclinical research. Consequently, this paper is primarily intended for non-RF specialists seeking a detailed, reproducible workflow for building custom MR microscopy hardware. There is currently no detailed guide in the literature on how to fabricate a coil system that is easy to construct, integrates seamlessly with these systems, and accommodates a range of sample sizes. We describe the design and manufacture of a micro-imaging probe with a transceive micro-solenoid coil that can be easily tuned and matched outside the bore, supporting solenoids with diameters ranging from less than 1 mm to 3.7 mm, where we performed susceptibility matching to reduce local B0 inhomogeneity at the copper-glass-sample interface. Larger coils (up to 10 mm) were used without susceptibility matching. We validated the probe’s performance by imaging ex vivo cervical mouse spinal cord and hippocampus tissues at a high spatial resolution of 15 μm isotropic, revealing tissue microstructures, that were identified through histology. Importantly, our micro-imaging probe leverages pre-existing system magnets, spectrometer, and gradients, eliminating the need for additional hardware modifications and making the design adaptable to any horizontal bore system. The cost of each probe is about 1/1000 that of a commercial cryoprobe.

Results

Validation of optimization algorithm for micro-solenoid geometry

Numerical simulations of micro-solenoids across various wire diameter-to-pitch ratios (dwire/s) indicate that the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) peaks between approximately 0.6 and 0.8 for the tested wire diameters and other fixed conditions (Fig. 1a). In these simulations, SNR was calculated numerically from the coil sensitivity (\({B}_{1}^{-}\)), Larmor frequency (\({\omega }_{0}\)), and the effective resistance (Reff) determined from coil, lead, capacitors and sample (magnetic and dielectric) contributions, using Eq. (1) in Methods. To validate these results, SNR measurements were conducted on different coils as described in Methods (section Optimization of the micro-solenoid geometry). The measured SNR curves (Fig. 1b–e, Supplementary Fig. 1) showed strong agreement with simulated trends, with peaks at dwire/s of approximately 0.5–0.6, and with correlation coefficients R ranging from 0.883 to 0.975 (see Fig. 1f) for the first three wire diameters (150 μm, 230 μm, and 280 μm). The optimal dwire/s ratios determined experimentally closely matched the simulated peak positions, with absolute differences(\(\triangle\)) of 0.008–0.025, corresponding to relative differences of 1.6–5.1%. For the 440 μm wire case, measured peak was not fully resolved. RMSE values for the first three wire diameters were \(\le\) 0.288, indicating that the simulations accurately reproduced both the peak locations and the overall SNR curve shapes (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for details of peak calculation).

a Simulated SNR as a function of the wire diameter-to-pitch ratio (dwire/s) for solenoids with wire diameters ranging 150–440 μm. The solenoid length was fixed to the arithmetic mean length of solenoids used for experimental SNR measurements (shown in b–e). For example, for dwire = 150 µm (red plot), the solenoid length was set to the average length of the four solenoids (red hollow triangles) used for SNR measurements in (b). A similar approach was applied to other wire diameters. b–e Comparison of simulated and experimentally measured SNR versus dwire/s for wire diameters of (b) 150 µm, (c) 230 µm, (d) 280 µm, and (e) 440 µm. Measured SNR values are shown as hollow triangles, with error bars indicating mean ± standard deviation across three adjacent slices. Hollow circles represent simulated SNR values accounting for the actual solenoid lengths, while the dotted curves represent the same simulation plots from subplot (a). To allow direct comparison across coil geometries, all simulated and experimental SNR values (in all subplots) were normalized by dividing by the minimum SNR of the 150 µm dataset for that data type (hollow red circle for simulated and hollow red triangle for experimental in subplot (b)). As a result, the 150 µm dataset has a baseline of 1, while the other datasets are scaled relative to this same reference, allowing direct comparison of relative SNR across wire diameters. f Summary table showing measured and simulated peak dwire/s values (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for details of peak calculation), absolute and percentage differences (\(\Delta\)), root-mean-square error (RMSE), and correlation coefficients (R) between simulated and measured SNR curves for each wire diameter. g Simulated maximum deviation of RF field strength at the sample’s edges \(\left(\frac{\Delta {B}_{1}^{-}}{{B}_{1}^{-}}\right)\) versus length of coil to diameter of the coil ratio (lcoil/dcoil) given the length of sample to diameter of coil ratio (lsample/dcoil) of 2. h Simulated SNR versus wire diameter (dwire) for various numbers of solenoid turns, considering the following coil geometry: coil diameter (dcoil) = 3.7 mm, coil length (lcoil) = 8.4 mm, sample diameter = 3 mm, and sample length = 6 mm. All the SNR values in (h) were normalized by the minimum SNR across all cases, occurring at dwire = 4.2 mm.

For tissue imaging, we followed the pipeline in Methods. In keeping with standard microcoil practice21,29, we assessed RF-field homogeneity at the sample edges, defined as the two axial end planes of the specimen—i.e., the planes located at ±½ × sample length from the coil center, where the sample approaches the coil ends. These planes are explicitly marked in the homogeneity map and profile (Fig. 2b, c; see Methods for full description) and used as the locations where our edge-uniformity threshold is enforced. For hippocampus imaging (3 mm coil diameter, 6 mm sample length), a coil length-to-diameter ratio lcoil/dcoil = 2.80 met our homogeneity criterion of ≤ 15% deviation at the sample edges (Fig. 1g). This threshold–less strict than the ~4% used by Minard et al.21–was chosen as a practical SNR–uniformity trade-off for our specimen size; readers who need tighter uniformity can adopt a longer coil at the cost of SNR. Simulations of SNR versus wire diameter across turn counts then identified an optimal wire diameter of ~0.7 mm with five turns (Fig. 1h), which guided construction for hippocampal imaging. The same procedure was applied to design the spinal cord coil.

a The micro-solenoid optimization process begins by specifying the sample length (lsample) and coil diameter (dcoil). Based on the ratio of sample length to coil diameter (lsample/dcoil), an appropriate coil length-to-coil diameter ratio (lcoil/dcoil) is selected to achieve the desired RF field deviation at the sample edges (set at 15% in this example). From the chosen ratio, the coil length (lcoil) is determined. Next, the SolenoidOptimizer MATLAB program performs a numerical simulation of the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) versus wire diameter (dwire) for various numbers of turns. The simulation script accepts geometry parameters including the number of turns (n), coil length (lcoil), lead wire length, coil diameter (dcoil), wire diameter (dwire), wire pitch, and sample properties such as conductivity, sample diameter (dsample), and sample length (lsample). Using these parameters, it calculates several electrical properties: sensitivity (\({B}_{1}^{-}\)), the enhancement factor that corrects for proximity effects influencing coil resistance, inductance of the coil and lead wires (Lcoil, Llead), resistance of the coil and lead wires (Rcoil, Rlead), and sample-induced losses (RsampleMagnetic, RsampleDielectric), which collectively contribute to the effective resistance (Reff) at a given operating MR frequency. The SNR is calculated using the relation SNR ~ \({B}_{1}^{-}\,{\omega }_{0}^{2}/\surd {R}_{{eff}}\). The optimal combination of wire diameter and number of turns is identified based on the configuration that yields the highest SNR. b Simulated \({B}_{1}^{-}\) map along the axis of the optimized micro-solenoid (n = 5, dcoil = 3.7 mm, lcoil = 8.4 mm for a sample of diameter dsample = 3 mm and length lsample = 6 mm). Contours show \(\triangle {B}_{1}^{-}/{B}_{1}^{-}\); vertical red dashed lines mark the sample edges at ± ½ × lsample on the coil axis where the homogeneity criterion is enforced, and the vertical magenta dashed lines mark the coil edges. c Simulated \({B}_{1}^{-}\) profile along the axis in the center of the coil. As in (b), the vertical red dashed lines mark the sample edges at ± ½ × lsample, and the vertical magenta dashed lines mark the coil edges. From both (b, c), we can see that \(\frac{\triangle {B}_{1}^{-}}{{B}_{1}^{-}}\, \sim\) 15% near the sample edges when the optimized geometry parameters are used.

Spinal cord MR imaging and histological validation

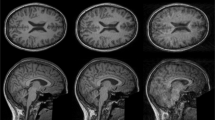

Figure 3a–c present representative orthogonal slices from the 3D volume image (see Supplementary Movie 1) of the mouse spinal cord at an isotropic spatial resolution of 15 μm. This imaging achieved a SNR of 38 in gray matter (GM) and 17 in white matter (WM). The coronal slice (Fig. 3a) and sagittal slice (Fig. 3b) reveal distinct microstructures, including the central canal and nerve fiber-like structures (black arrows) extending outward from GM into WM. The axial slice (Fig. 3c) provides additional insight into the GM, highlighting significant signal variations. These include the central canal (CC), ventral nerve roots (VN) of motor neurons extending from the GM into the WM, and potential nerve fibers entering the dorsal horn (white arrow). Additionally, networks of hypointense cores with fiber-like extensions (black arrow) are distributed within the GM. These features are not well-resolved in the lower-resolution 40 μm isotropic images of the same spinal cord (see Supplementary Fig. 2).

a Coronal slice of the spinal cord. The black arrow indicates nerve fiber-like structures in the gray matter, resolved at high resolution. b Sagittal slice of the spinal cord. The central canal (CC) is resolved in both coronal and sagittal images. c Transverse slice of the spinal cord. The white arrow points to possible nerve fibers entering from the dorsal horn of the gray matter, while the black arrow indicates the heterogeneity in the gray matter, potentially due to cell bodies of motor neurons, their dendritic extensions, and nerve fibers in the ventral horn. The ventral nerve roots (VN) emerging from the ventral horn are also resolved at high resolution. d Coronal slice of the hippocampus. e Sagittal slice of the hippocampus. The black arrow in the coronal and sagittal slices highlights the resolved cellular layers of the hippocampus, while the white arrow indicates structures measuring 4–20 voxels (~60–300 μm) may result from tissue tearing or damage during preparation. f Transverse slice of the hippocampus. Resolved structures include the Cornu Ammonis layers (CA1, CA2, CA3), the granule cellular layer of the dentate gyrus (DG), and the hippocampal fissure (HF). Smaller structures measuring 2–4 voxels (~30–60 μm) as indicated by light blue arrows in (d–f) could potentially represent blood vessels. The scale bars represent 500 µm. Images were upscaled 8-fold using bicubic interpolation in MATLAB for smoother visualization. The upscaling does not increase spatial resolution or modify the original data content.

To interpret these observations, Fig. 4a–t compares regions of interest (ROIs) from an axial slice of the 3D MR volume with histological stains—H&E, LFB, and CV—from the same spinal cord regions. Each stain highlights specific components: H&E emphasizes nuclei, LFB highlights myelin, and CV stains neurons. All three stains reveal key microstructures, such as the central nucleolus, the surrounding nucleus, and the cytoplasm of sensory neurons in the dorsal horn (red arrows, Fig. 4f–h) and motor neurons in the ventral horn (red arrows, Fig. 4j–p). These neuronal features correspond to hypointense circular structures in the MR images (red and orange arrows, Fig. 4i, m), approximately 2–3 voxels (~30–45 μm) in size, which we interpret as corresponding to the cytoplasm and its dendritic extensions (~30–45 μm in length and ~20–30 μm in width), as seen in the stained images shown by red and orange arrows, Fig. 4f–j, l–p. The hypointense appearance of cell bodies in the MR images can be attributed to their longer relaxation time T1 compared to the surrounding extracellular space.

a Transverse slice of the 15 μm isotropic volume image of the spinal cord with four regions of interest (ROIs) highlighted in different colors. b Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain of the spinal cord with the similar four ROIs as in (a). c Luxol Fast Blue (LFB) stain. d Cresyl Violet (CV) stain. e–h ROI 1 (red) compares the intermediate zone and dorsal horn of the spinal cord in the MR and stained images. i–l ROI 2 (green) corresponds to the left ventral horn region. m–p ROI 3 (blue) corresponds to the right ventral horn region. q–t ROI 4 (magenta) represents the central canal. The red arrows in (f–j, l–p) highlight the cell bodies of neurons, while the orange arrows indicate dendrites extending from neuronal cell bodies. The yellow arrows in (i, k, m–o) indicate the nerve roots emerging from the gray matter into the white matter, and the magenta arrows highlight the ependymal cellular layer lining the central canal. The green arrow in (e, g) marks patchy white matter structures at the gray matter-white matter interface in the intermediate zone. The blue arrows in (e, g, i, k, m, o) indicate possible myelinated nerve fibers in the transverse plane distributed throughout the gray matter as seen in the LFB-stained images. The white arrow in (f, j, n) indicates glial cells. The scale bar in (a–d) represents 250 µm, the scale bar in MR image ROIs (e, i, m, q) represents 100 µm, and the scale bar for stained ROI Fig. f–h, j–l, n–p, r–t represents 50 µm. The MR images in Fig. (a, e, i, m, q) were upscaled 8-fold using bicubic interpolation and their contrast adjusted in MATLAB to enhance visualization. It is important to note that the upscaling does not increase the spatial resolution or alter the original data content.

In the WM, axons running axially appear as tiny circular empty spaces surrounded by dense myelin (black arrows, Fig. 4k, o). These features may result from tissue dehydration during processing with 70% ethanol, which can alter tissue morphology. However, WM heterogeneity in MR images was not as discernible compared to the GM. In the intermediate zone (red ROIs), located between the dorsal and ventral horns, patchy regions of WM (green arrows, Fig. 4e, g) are interspersed with GM structures. Within these tracts, the GM contains cell bodies (red arrows, Fig. 4f–h) and myelinated fibers running transversely (blue arrows, Fig. 4g).

Although primarily composed of cell bodies, the dorsal and ventral horn also contain significant myelinated fibers extending in the transverse plane (blue arrows, Fig. 4g, k, o), as confirmed by LFB staining. Smaller structures, such as glial cells (white arrows, Fig. 4f, j, n), are distributed throughout the GM with diameter ~7 μm in the H&E stain, which may not have significantly contributed to the heterogeneity of GM due to the MR image resolution of 15 μm. Interestingly, the high resolution of 15 μm isotropic also resolved nerve roots extending from the ventral horn of the GM into the WM (yellow arrows, Fig. 4i, m), which are about two voxels wide (~30 μm). These nerve roots are corroborated by their presence in histological stains, including H&E and LFB, where they measure approximately 20–30 μm in width (yellow arrows, Fig. 4k, n, o).

The central canal appears in MR images as a circular hypointense region surrounded by a bright hyperintense ring (magenta arrow, Fig. 4q). This feature is also depicted in histological stains (magenta arrows, Fig. 4r–t), where the canal is lined by a single layer of ependymal cells (~7–10 μm in diameter). The hyperintense ring in the MR images likely results from Gadolinium-doped PBS infiltration into the extracellular region near the canal during tissue washing, while the central hypointense region is attributed to Fomblin infiltration into the cord.

While blood vessels and capillaries may also contribute to the heterogeneity of the GM, our attempt to acquire CD31 staining of the cord was less successful. This stain, which typically marks blood vessels with a brown lining, was likely affected by the perfusion fixation and prolonged exposure to PBS and Fomblin during tissue preparation and MR scanning (see Supplementary Fig. 3a–e).

Hippocampus MR imaging and histological validation

Figure 3d–f display representative orthogonal slice images from the 3D volume (see Supplementary Movie 2) of the mouse hippocampus acquired at an isotropic resolution of 15 μm and an SNR of 67. The images reveal well-resolved hippocampal microstructures such as cellular layers in the coronal and sagittal slices (black arrows, Fig. 3d, e). In the axial slice, as shown in Fig. 3f, additional microstructures are resolved, including the hippocampal fissure (HF), Cornu Ammonis (CA1–CA3) cellular layers, and the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus (DG), which are not resolved in low-resolution 40 μm isotropic images (see Supplementary Fig. 4). In addition to the resolved anatomical features, we observed occasional discontinuities and elongated hypointense structures in the hippocampal MR images. These features, consistent with the white arrows highlighted in Fig. 3d, e, are unlikely to represent true anatomy and may result from tissue tearing, handling, or damage during sample preparation.

To verify these structures, Fig. 5a–t compare regions of interest (ROIs) from the 3D MR volume slice to corresponding histological stains—H&E, LFB, and CV—of the same hippocampal regions (Fig. 5e–t). The CA1 (red arrow, Fig. 5e), CA2 (green arrow, Fig. 5i), and CA3 (magenta arrow, Fig. 5m) pyramidal cell layers are distinctly visible in the MR images. Patches of hypointense signals correlate with regions populated by pyramidal cells of diameter ~10 μm in CA1 layer (red arrows Fig. 5f–h), ~20 μm in length and ~10 μm in width in CA2 layer (green arrows Fig. 5j–l), and ~25–30 μm in CA3 layer (magenta arrows Fig. 5n–p) in the histological stains. Similarly, clusters of granule cells in the dentate gyrus (DG) were resolved in the MR images (blue arrow, Fig. 5q). The histological stains confirmed the presence of granule cells in the DG (blue arrows, Fig. 5r–t), with their cytoplasm measuring approximately 8 μm in diameter in both H&E and CV stains.

a Transverse slice of the 15 μm isotropic volume image of the hippocampus with four regions of interest (ROIs) highlighted in different colors. b Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain of the hippocampus with similar four ROIs as in (a). c Luxol Fast Blue (LFB) stain. d Cresyl Violet (CV) stain. e–h ROI 1 (red) represents the CA1 layer of the hippocampus in the MR image, H&E stain, LFB stain, and CV stain, respectively. i–l ROI 2 (green) represents the CA2 cellular layer. m–p ROI 3 (magenta) represents the CA3 cellular layer. q–t ROI 4 (blue) represents the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus. The red arrows in (e–h) highlight clusters of pyramidal cells in the CA1 layer. The green arrows in (i–l) indicate pyramidal cells in the CA2 cellular layer. The magenta arrows in (m–p) indicate pyramidal cells in the CA3 cellular layer. The blue arrows in (q–t) highlight granule cells in the dentate gyrus. The white arrow represents glial cells. The scale bar in (a–d) represents 250 μm, and the scale bar for all the ROI Fig. e–t represents 50 μm. The MR images in Fig. (a, e, i, m, q) were upscaled 8-fold using bicubic interpolation and had their contrast adjusted in MATLAB to enhance visualization. It is important to note that the upscaling does not increase the spatial resolution or alter the original data content.

The histological stains also identified potential glial cells (white arrows, Fig. 5f, j, r) distributed throughout the hippocampus, however, unlikely resolved in MR images due to their approximate size of 10–12 μm in the stains. CD31 staining was performed to test for the presence of blood vessels; however, only a few positive CD31 represented by brown stains in elongated structures, measuring approximately 25–60 μm in length, were observed, possibly representing the inner lining of blood vessels (see Supplementary Fig. 3f–j).

The reported dimensions in the above sections were estimated by counting the number of pixels in the histological images of a subset of cells. These measurements may not fully represent the entire distribution of cell sizes due to potential sampling bias. Additionally, tissue shrinkage during staining and processing could have affected the absolute dimensions of the cells. As such, these values should be interpreted as approximate rather than definitive.

Discussion

This work presents a comprehensive, step-by-step approach to designing and constructing a micro-imaging probe optimized for maximum SNR in ultra-high-resolution MR microscopy. The probe employs a single-channel transceive micro-solenoid coil, which performs both RF transmission (\({B}_{1}^{+}\)) and reception (\({B}_{1}^{-}\)) of the MR signal. It is highly cost-effective compared to commercial coils and can be adapted to high-field horizontal bore systems with only minor modifications. The total build cost is approximately USD 700, which is substantially lower than the USD 300,000–400,000 that is typically required for commercial high-resolution microimaging probes or cryoprobes. Although the design is based on a narrow-bore 15.2 Tesla horizontal system, minimal adjustments to the coil housing and capacitors allow similar probes to be created for narrow to wide-bore systems operating at different \({B}_{0}\) field strengths.

The SNR performance of a micro-imaging probe is significantly influenced by coil parameters including coil diameter, coil length, copper wire diameter, and the number of turns. The optimization procedure considers SNR reductions caused by coil resistivity, capacitive losses, and the sample’s dielectric and magnetic properties. By identifying the optimal number of turns for each wire diameter, the method maximizes SNR while achieving the desired RF field homogeneity. The simulation results closely matched experimental measurements of micro-solenoids with a coil diameter of approximately 0.87 mm, showing peak SNR values at wire diameter-to-pitch ratios around 0.6–0.7 when using conductive samples. This wire diameter-to-pitch ratio range aligns well with established literature30. The strong agreement between simulation and experimental data (in Results) validates the optimization algorithm as described in the Methods, which was subsequently used to optimize coil geometries for hippocampus and spinal cord imaging, ensuring maximum achievable SNR at specified RF homogeneity levels.

The quasi-static approximation used in this work assumes the coil’s physical dimensions are small compared to the RF wavelength \(\lambda\). For a small solenoid, the transition to full-wave effects (such as radiation losses and phase variations) typically becomes significant when the coil’s circumference or length, \({L}_{{coil}}\), exceeds \(\sim \,\lambda /10\). At our operating frequency of 650 MHz (corresponding to \(\lambda \, \sim\) 46 cm in free space, or \(\sim\)31 cm in water), the \(\lambda /10\) limit is approximately 3–4 cm. Our largest coil diameter is 10 mm (and length is comparable), so the quasi-static approximation remains valid for our coil geometries at 650 MHz. However, the full-wave model becomes increasingly necessary as the operating frequency (\({\omega }_{0})\) increases or the coil diameter dcoil increases, as this reduces the ratio \(\lambda /{L}_{{coil}}\). For systems with dcoil \(\sim\) 1 cm, the practical upper field limit where a quasi-static model remains robust is typically around 3 GHz, or higher if the coil dimensions are significantly smaller. We acknowledge that full-wave electromagnetic simulations (e.g., HFSS, CST, XFdtd) can provide a more rigorous partitioning of conductor, capacitor, sample, and radiation losses. The full-wave simulations could be benchmarked against experimental measurements by comparing the simulated S11 parameters and the measured \({B}_{1}^{+}\) field profiles, which, by reciprocity for these small coils, validate the receive sensitivity (\({B}_{1}^{-}\)) required for SNR estimation. Such simulations represent an important avenue for future work, particularly for coils approaching larger electrical dimensions or when imaging highly conductive samples at ultra-high fields.

Our probe’s effectiveness is demonstrated by high-resolution images of the mouse spinal cord and hippocampus. High spatial resolution at 15 μm isotropic revealed spinal cord microstructures, such as the central canal, ventral nerve roots in WM, and notable heterogeneity in GM with possible resolution of neuronal cell bodies, confirmed by histology. We observed a difference in contrast, with a central GM SNR of 38 and a WM SNR of 17. This disparity is likely driven by a combination of intrinsic tissue properties—such as lower proton density and shorter T₁ in WM—as well as potential differences in Gadolinium diffusion and uptake. The spinal cord gray matter may retain more Gadolinium due to its microstructural and vascular characteristics, resulting in stronger T₁ shortening and higher signal. While B1 inhomogeneity could contribute, the tissue’s position within the most homogeneous region of the coil makes this less likely. Additionally, hippocampal microstructures, including the CA1-3 cellular layers and the granule cellular layer of the dentate gyrus, were visualized at a spatial resolution of 15 μm isotropic. By comparison, these structures were indistinguishable in images of the same tissues with a slightly lower resolution of 40 μm isotropic (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 4). While the T1-weighted images were acquired for demonstration purposes in this work, the probe’s imaging capabilities may have potential applications in relaxometry, diffusion, magnetization transfer, and spectroscopy studies. Potential samples of interest would be animal tissue sections, plant tissues, insects, and phantoms. A limitation to note is that certain discontinuities and elongated voids observed in the hippocampal images (Fig. 3d, e) are likely artifacts introduced during tissue handling or sectioning. In addition, tissue shrinkage and deformation during preparation and histological processing may alter sample geometry and cellular dimensions, which should be considered when interpreting absolute size estimates or comparing MRI with histology.

An important feature of the probe is its capability for susceptibility matching, which substantially reduces field inhomogeneities and signal distortions. This feature is critical for micro-imaging applications where susceptibility-induced artifacts can severely limit resolution and image quality (See Supplementary Fig. 5). However, susceptibility matching requires the detachable sample holder with an integrated Fomblin well, which constrains the maximum coil size. When a larger solenoid (~6–10 mm in diameter and length) is used for imaging larger samples, such as whole mouse brains (Supplementary Fig. 6), susceptibility matching was not achievable in our setup because the Fomblin well cannot completely submerge the coil and sample. In such cases, susceptibility differences can be significantly reduced by replacing the glass sample holder with a plastic one, as demonstrated in whole mouse brain imaging (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Despite the trade-offs in SNR due to the larger coil, this configuration still enables microscopy of larger specimens—including excised brains, kidneys, liver sections, and biopsy samples—for applications that do not require ultra-high resolution.

Although sub-10 µm voxel sizes have been demonstrated in previous studies6,7,14,26, these were typically achieved with ultra-small coils and miniature samples (e.g., micro-bead phantoms in <100 µm capillaries), where the high sensitivity of small coils and reduced coil resistive loss are confined to very limited volumes close to the coil. In contrast, our work emphasizes high-resolution volumetric imaging of millimeter-scale biological tissues on a horizontal bore system, enabling applications where larger structures must be examined holistically. Our approach provides a reproducible and cost-effective probe design suited for studying systems-level neurobiology (e.g., spinal cord injury in rodents, hippocampal lamination) without sacrificing field of view. Using a 3.7 mm diameter solenoid, we achieved 15 µm isotropic resolution imaging of the mouse spinal cord and hippocampus, resolving microstructural features such as spinal cord architecture and hippocampal layers in which neuronal cell bodies (15–30 µm in size) are resolved within the intact tissue volume. Our hippocampus imaging achieved an SNR of \(\sim\)67 in \(\sim\)45 h, corresponding to an SNR efficiency of \(\sim\)10.0 SNR/√hour. This provides a quantitative benchmark for biological tissue imaging at this resolution and field of view. The SNR scales as \(\propto\) 1/dcoil for millimeter-scale diameters, so a smaller coil of diameter \(\sim \,\)1 mm could, in principle, push the resolution towards \(\sim\)10 μm isotropic in a similar scan duration with comparable SNR efficiency. For even smaller coils (dcoil ~ 100 μm), SNR \(\propto\) \(1/\sqrt{{{\rm{d}}}_{{\rm{coil}}}}\)22, enabling further resolution gains. While direct comparison with previous MRM studies is challenging due to differences in \({B}_{0}\) field strength, sample types (paramagnetic phantoms vs. biological tissues), gradient performance (affecting minimum TE), and pulse sequences, the SNR efficiency allows a fairer cross-study comparison. Notably, studies using CuSO₄-doped phantoms benefit from shortened T₁ relaxation enabling faster acquisition, while biological tissues are inherently limited by longer T₁ values and greater susceptibility-induced signal losses.

Despite the above-mentioned advantages of the imaging probe, the scan time for ultra-high-resolution 3D acquisitions still takes hours. Several potential improvements can be tested in the future. First, pure phase encoding constant time imaging (CTI), which has been known to outperform frequency encoding in terms of SNR at high resolution, can be utilized to acquire higher resolutions6,10,31. In addition, studies have shown that acceleration techniques such as compressed sensing with non-linear reconstruction can speed up microscopy experiments by a factor of 532,33, while compressed sensing with AI-supported reconstructions can further reduce image noise34. Another variation is parallel imaging, which—if implemented with multiple receiver coils or microcoil arrays—which can reduce scan times without directly increasing SNR, thereby enabling more efficient acquisitions or permitting additional averaging to recover lost sensitivity. Micro-gradients over a localized volume are often prescribed for micro-imaging due to their high gradient strengths, which offer notable SNR advantages and help to expand the maximum achievable resolution6,8,10,13,26,35. However, it should be noted that designing such gradients is not straightforward and requires extensive work to optimize the performance. While preexisting gradients may have SNR limitations due to longer echo time at high resolution, they provide greater reliability during high-duty-cycle gradient-intensive imaging, such as diffusion MR microscopy at high resolution, where factors like gradient uniformity, rise time, and thermal stability are crucial. With the 1 T/m gradient coil in the 15.2 T scanner, the maximum high resolution that we can target can be calculated by5 \(\triangle {x}_{{Diffusion}} \sim \,2.6{\left(\frac{D}{\gamma G}\right)}^{\frac{1}{3}}\) where D is the diffusion coefficient and G is the gradient strength. By taking the free water diffusion value of D = 2.4 μm2/ms, we can get to the resolution limit of 5.4 μm before the linewidth broadening due to diffusion limits further reduction of the voxel size. However, reaching such an extreme resolution would require further SNR improvement to decrease the scan time. To this date, the highest resolution reported was 3 micron isotropic voxel by Weiger et al.6, which has been achieved using micro-surface coils with diameters less than 500 μm, as previously applied by several studies6,9,15,17,36. However, the \({B}_{1}\) sensitivity of micro-surface coils drops significantly with increasing distance from the coil37, which limits the sensitivity to only the surface of the tissue. Because of all of the above-mentioned issues, a micro-solenoid design was chosen for this study due to the ease of fabrication and significant \({B}_{1}\) homogeneity over a large sample volume compared to a micro-surface coil.

We have provided a detailed step-by-step guide for constructing and applying a low-cost micro-imaging probe to perform microscopy within a horizontal bore MR system. The probe’s capability for susceptibility matching and utilization of preexisting gradients allows for high-quality imaging without requiring significant hardware modifications to the MR console. This comprehensive guide can serve as a valuable resource for building similar micro-imaging probes for pre-clinical horizontal bore systems, facilitating potential applications in MR microscopy.

Methods

Micro-imaging probe development

The micro-imaging probe consists of a coil housing assembly that includes a coil base, sample holder, and circuit holder (Fig. 6 top). The sample holder houses a Fomblin well (for susceptibility matching), a micro-solenoid, and a sample capillary, while the circuit holder accommodates the printed circuit board (PCB) and the tune-and-match assembly. The tune-and-match assembly consists of tuning and matching rods and parts that connect the rods attached to the trimmer capacitors. Lastly, the cable assembly comprises the coaxial cable and the balun circuit. Sections below describe in detail the step-by-step process of developing each of these components and assemblies. Note that the following provides a design example for a 15.2 T MRI system. The specific coil sizes and the B0 field strength can be easily adjusted using the approaches below to suit different applications. In this work, the micro-solenoid RF coil was implemented as a single-channel transceiver, serving both as the transmit (\({B}_{1}^{+}\)) and receive (\({B}_{1}^{-}\)) element.

Top: SolidWorks model of the micro-imaging probe. The design illustrates the micro-coil radiofrequency circuit optimized for use in a horizontal bore 15.2 T magnet. The entire probe is designed to be inserted into the back end of the 15.2 T magnet. The S11 measurement shows about –50 dB dip at resonance (650 MHz) for both loaded (PBS) and unloaded micro-solenoids (inner coil diameter ~3 mm, wire diameter ~0.7 mm, 5 turns), later used for hippocampus imaging. Bottom: Components and assemblies for constructing micro-imaging probes. a Acrylic coil base b Sample holder with openings for the capillary (green arrows) and lead wires of the micro-solenoid coil (red arrows). c Circuit holder. d Cap for the Fomblin well in the sample holder. e O-ring for sealing the cap. f printed circuit board. g Chip capacitor. h Trimmer capacitor. i A representative micro-solenoid and glass capillary. j Circuit design schematic: Cb represents balance capacitors (chip capacitors), Cm is the match trimmer capacitor, and Ct is the tune trimmer capacitor. k Circuit assembly with soldered components. l Balun circuit. m SolidWorks model of the balun with an interior view of the circuit (Ct is a tuning chip capacitor). n Components of the tune and match assembly: 1. Spring retainer, 2. O-ring, 3. Brass Spring, 4. Plastic ferrule, 5. Cover. o Internal view of the tune and match assembly, showing its components. p Fully assembled tune and match rod. q Garolite rod and tuning knobs. r Coaxial cable that connects the balun circuit to the ODU plug. s ODU plug that connects the coaxial cable to the 15.2 T magnet. t Custom-built fan box for blowing room-temperature air into the bore of the 15.2 T magnet. u Final assembly of the micro-coil RF circuit. Rubber stoppers seal the capillary insertion points of the Fomblin well, and foam padding minimizes vibrations of the coil during gradient-intensive imaging. Blue arrows indicate the opening for the Fomblin spill tank preventing the leakage of Fomblin into the bore.

Coil base development

The coil base serves as the mechanical backbone of the probe, providing a stable platform that securely mounts to the scanner gradient assembly while maintaining alignment and accessibility.

-

1.

An acrylic tube (OD = 5.0 cm, ID = 4.4 cm, length = 106 cm) was first split axially to form a semicylindrical half using a table saw. One of the semicylindrical halves was attached to a square-shaped acrylic plate with a circular hole of the same diameter as the acrylic tube (dim.: 9.5 cm × 0.5 cm), as shown in Fig. 6a.

-

2.

Before attaching the rectangular base, four screw holes were drilled and tapped into the plate. This helps secure the probe to the screw holes on the gradients outside the magnet.

Sample and circuit holder development

This assembly was designed to integrate the sample and RF components into a compact, modular unit that facilitates tuning, positioning, and sample exchange while maximizing mechanical stability. A SolidWorks assembly for the circuit and sample holder was finalized after several design iterations and testing improvements. The final design, 3D-printed in clear material using a Stratasys J35 Pro 3D printer, consists of three main components: (1) a sample holder, (2) a circuit holder, and (3) a cap (Fig. 6b–d).

-

1.

The sample holder contains a well designed to be filled with Fomblin—a perfluorinated polyether fluid—which can be used to mitigate the effects of magnetic susceptibility caused by the proximity of the coil to the sample13,38 (see Supplementary Fig. 5). The Fomblin well includes two sets of holes: one for inserting the sample capillary (Fig. 6b, green arrows) and the other for inserting the lead wires of the micro-solenoid (Fig. 6b, red arrows).

-

2.

The circuit holder has a slot for securing the PCB and two arms for supporting the trimmer capacitors (Fig. 6c). The semicylindrical tail of the Fomblin well unit slides through the circuit holder, forming an integrated sample and circuit holder assembly.

-

3.

The Fomblin well is sealed with a cap (Fig. 6d) and an O-ring (Fig. 6e) to prevent leakage.

PCB circuit development

The custom layout provides a precise and reproducible interface for high-frequency tuning and matching components, tailored for solenoid integration and minimal parasitic effects at 650 MHz.

-

1.

The RF circuit PCB layout was initially sketched in 3D modeling software (SolidWorks 2018). The sketch consisted of two layers: (1) the circuit board outline and (2) the copper trace pattern, as shown in Fig. 6j.

-

2.

The sketches were converted into Drawing Exchange Format (DXF) files and imported into an electronic design software (DipTrace). Gerber (GRB) files were then generated for the top layer and board outline. These files were then imported into computer-aided manufacturing software (LPKF CircuitPro PM 2.7) to control an LPKF milling router (LPKF Laser & Electronics).

-

3.

The final PCB was printed on FR4-clad material with a single copper layer on top. The completed circuit is shown in Fig. 6f.

Circuit components and soldering

The tuning and matching capacitors allow precise control of the resonance frequency and impedance, critical for optimizing SNR. Balanced capacitors and coaxial connection ensure stable RF performance and minimal signal reflection.

-

1.

Two trimmer capacitors, with a capacitance range of 0.7–10 pF, were soldered to the PCB (Fig. 6h, j, k). The trimmer positioned near the signal port serves as the matching capacitor (for impedance matching to 50 Ω), while the other functions as the tuning capacitor (for resonance at 650 MHz). Additionally, two chip capacitors with a capacitance of 33 pF were soldered as balance capacitors (Fig. 6g, j, k).

-

2.

A short coaxial cable with an SMB connector plug was soldered to the PCB (Fig. 6k), to which a bazooka balun is later connected.

-

3.

A copper wire of appropriate diameter was wrapped around a glass capillary of desired diameter to form a solenoid (Fig. 6i). The coil length and number of turns are optimized for a given sample, which is discussed in the Methods (Optimization of micro-solenoid geometry).

-

4.

After winding the wire, the insulation on the lead wires was scraped off, allowing them to be soldered to the PCB.

Balun circuit development

The balun suppresses common-mode currents along the coaxial cable that can introduce RF interference or degrade the image quality. This is especially important at high fields and for small coils.

-

1.

A bazooka balun39,40 (balanced–unbalanced) circuit was constructed using a coaxial cable, copper shielding, male SMB connectors, 3D-printed helical grooves, and chip capacitors (Fig. 6l, m).

-

2.

The balun circuit resonates at 650 MHz, preventing interference from common-mode currents on the coaxial cable surface, which could disrupt signal transmission.

Tune and match assembly development

The tune and match assembly enables remote fine-tuning of the RF circuit outside the magnet bore, avoiding repeated repositioning and improving workflow. Mechanical stability of the rods is crucial for precise capacitor adjustment.

-

1.

Two 3 mm diameter Garolite rods were used to make the tuning rods.

-

2.

A thin vertical cut was made at one end of each rod using a razor saw. A flat copper piece was inserted into the cut, serving as the driver tip for the tuning rod. The gap was filled with superglue to secure the copper piece (Fig. 6o).

-

3.

A 3D-printed retainer (Fig. 6n, part 1) was glued about 1 cm from the tip of the rod. A rubber O-ring (Fig. 6n, part 2) was placed concentrically with the retainer to provide frictional resistance and maintain concentric alignment of the rod, thereby preventing unwanted slipping or wobbling during tuning. The rod was inserted into a 1 cm long brass spring, with a plastic ferrule (Fig. 6n, part 4) sliding through the opposite end. The plastic ferrule acts as a secondary retainer, as shown in Fig. 6o.

-

4.

The entire assembly was enclosed in a 3D-printed cylindrical cover (Fig. 6n, part 5) with through-holes for a brass screw, which prevent the ferrule from slipping under spring tension as shown in Fig. 6p. The covers were fabricated on a Form3 printer (Formlabs Inc.) using Tough 2000 resin. Each cylindrical cover incorporated a fine-thread design, allowing it to securely attach to the trim capacitors.

-

5.

Three tune rod supports (Fig. 6 top, 6u) were 3D-printed using the Form3 printer. These supports provide physical support to the tuning rods.

-

6.

Tuning knobs, machined from large plastic screws on a lathe, were attached to the ends of both tuning and matching rods and secured with brass screws (Fig. 6q).

Final assembly

The final integration ensures alignment between the solenoid, PCB, and interface components for optimal RF performance, mechanical stability, and reproducibility of imaging conditions.

After all the parts were built, a final hardware assembly was carried out.

-

1.

First, the PCB with soldered components was installed in the circuit holder (Fig. 6k). Next, a micro-solenoid was inserted into the sample holder and aligned with the two holes (Fig. 6b, green arrows) using a glass capillary, ensuring the lead wires passed through (Fig. 6b, red arrows).

-

2.

The sample holder was slid into the circuit holder, and the solenoid’s lead wires were soldered to the PCB.

-

3.

The combined assembly of the circuit and sample holder was then attached to the acrylic tube using a plastic screw after drilling a through-hole in the tube’s bottom, and the tune-and-match rod assembly was connected to the trimmer capacitors.

-

4.

The balun circuit and coaxial cables were used to bridge the connection between the radio-frequency circuit and the ODU plug (Fig. 6r,s).

-

5.

A final check was performed by connecting the coil to an Open-short-load (OSL) calibrated vector network analyzer (VNA) to verify that the coil is tuned to 650 MHz and matched to 50 Ω using the tuning and matching rods. Ideally, the S11 plot should show a sharp dip at 650 MHz, with a return loss of –20 dB or better, indicating good impedance matching (see Fig. 6 (top right)).

The complete micro-imaging probe is shown in Fig. 6u. To further characterize probe performance, Supplementary Fig. 7 presents S11 measurements under different conditions (with and without susceptibility matching, and with and without sample loading). In addition, the effect of susceptibility matching on image quality was validated experimentally, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 5.The list of all the items used for the micro-imaging probe fabrication is provided in Supplementary Table 1. For reproducibility, all code and 3D-printed part designs used in this study are available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/BibekDhakal977/microSolenoidGeometryOptimizer.git).

Optimization of the micro-solenoid geometry

The micro-solenoid optimization process is based on the work by Minard et al. 21,29. It begins with two user-defined inputs: the sample length and the coil diameter (Fig. 2, left). The maximum deviation of the RF field at the sample edges near the coil ends is then computed for various coil length-to-diameter ratios. The sample length is defined by the user, either as the full specimen length or the portion intended to lie within the region of acceptable RF field homogeneity, while the coil diameter is determined by the diameter of the sample holder or capillary. This step establishes the minimum coil length required to achieve a chosen RF field homogeneity, given the known sample length and coil diameter. Once the coil length is determined, a custom MATLAB script (GitHub link provided) was used to perform numerical simulations of the expected SNR as a function of wire diameter across different solenoid turn counts (Fig. 2, right).

When temperature is held constant, preamplifier contributions are neglected, and acquisition parameters, sample properties, and pulse sequence settings remain unchanged, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of a micro-solenoid can be expressed as18,21:

where \({\omega }_{0}\) = 2\(\pi {f}_{0}\) is the Larmor frequency (with \({f}_{0}\) the resonant frequency), \({B}_{1}^{-}\) is the coil receive sensitivity defined as \({B}_{1}^{-}=\,\frac{{\mu }_{0}}{2}{({H}_{x}-i{H}_{y})}^{* }\) with \({H}_{x}\) and \({H}_{y}\) the transverse magnetic field components and \({\mu }_{0}\) is the permeability of free space, \({R}_{{eff}}\) is the effective resistance of the receiver coil and sample losses. Although the same micro-solenoid is used as a transceive coil, optimization focuses on the receive component of the \({B}_{1}^{-}\) field, since only the receive sensitivity directly contributes to the SNR.

The above-mentioned script calculates the SNR of a micro-solenoid given the coil geometry parameters (coil length, coil diameter, lead wire length, and number of turns) and sample geometry parameters (sample length, sample diameter, and conductivity). Specifically, the program computes coil sensitivity (\({B}_{1}^{-}\)), inductance, and resistance contribution from the coil, lead wires, capacitors, and sample (magnetic and dielectric losses), combines these into an effective resistance (\({R}_{{eff}}\)), and then estimates SNR using Eq. (1) at the operating frequency of 650 MHz (see Supplementary information, Noise budget and SNR calculation of micro-solenoid). The script above is used to iterate through possible wire diameters and turn counts, and the combination that yields the maximum SNR is then selected for constructing the micro-solenoid, ensuring both RF field homogeneity (see Fig. 2b, c) and maximal SNR.

Before using the above optimizing procedure for tissue imaging, validation experiments were conducted to ensure the accuracy of the developed script. Numerical simulations were first performed using the above-mentioned MATLAB script to calculate the SNR of micro-solenoids with an inner coil diameter of 0.87 mm, using copper wires with diameters ranging from 0.1 mm to 0.44 mm. The conductivity of the sample in the numerical simulation was set at 1 S/m, which closely resembles biological tissues. The number of turns ranged from 2 to 7, resulting in coils with an average length of approximately 3 mm and wire diameter-to-pitch ratios (dwire/s) varying from 0.1 to 1 (Fig. 1a). Subsequently, actual SNR measurements using uniform PBS phantoms (conductivity \(\sim \,\)1 S/m) sealed inside quartz capillaries (inner diameter: 0.7 mm, outer diameter: 0.87 mm, length ~4 cm; imaged portion ~3 mm) were performed to validate these simulations (Fig. 1b–e). In these experiments, copper wire thickness ranged from 0.15 mm to 0.44 mm, coils had an average coil length of about 3 mm, and the number of turns varied between 2 and 12, yielding wire diameter-to-pitch ratios from 0.1 to 0.8. The length of the two lead wires was consistently maintained at 5 mm. A quartz capillary (inner diameter: 0.7 mm, outer diameter: 0.87 mm, VitroCom) served as the sample holder for the PBS phantom, and both ends of the capillary were sealed using capillary wax. All solenoids used were individually tuned and matched to 650 MHz using the trimmer capacitors prior to imaging to ensure optimal resonance and impedance matching. Notably, the same trimmer capacitors were sufficient for all coils, and S11 remained consistently better than −50 dB, indicating high reproducibility and minimal fabrication variability.

MR imaging was conducted using a 15.2 T Bruker Avance III horizontal bore system (Bruker BioSpin, Billerica, MA) with a 110 mm bore diameter and an ID of 60 mm triaxial gradient system (Resonance Research, Inc., Billerica, MA) with a maximum gradient strength of 1 T/m in each direction. The imaging console was controlled by ParaVision 6.0.1 software. The PBS-filled capillaries above were scanned with a multislice 2D fast low-angle shot (FLASH) sequence using the following parameters: field of view (FOV) = 7×7 mm², image matrix = 128 × 128, slice thickness = 0.1 mm, number of slices = 3, echo time (TE) = 4 ms, repetition time (TR) = 100 ms, flip angle = 30°. The SNR was calculated using Eq. (2), based on manually drawn signal regions of interest (ROIs) in the center of the phantom image, and four noise ROIs drawn in the air outside the phantom in the four corners of the magnitude image. The SNR was then calculated as

The mean and standard deviation of the SNR of the three slices were then calculated. The correction factor \(\sqrt{(2-\pi /2)}\) ≈ 0.66 is needed because the noise in the magnitude-only images follows a Rayleigh distribution41 rather than a Gaussian distribution.

Tissue sample preparation

To illustrate the performance of the probe design, we elected to image small ex-vivo samples of mammalian neural tissues.

All animal protocols were approved by Vanderbilt’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). A 12-week-old adult male C57BL/6 J mouse (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor ME, USA) was anesthetized with isoflurane and sacrificed via transcardial perfusion. A 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) wash was perfused through the left ventricle, followed by a fixative solution (1X PBS, 4% glutaraldehyde, 0.5% paraformaldehyde, and 2.0 mM Gadolinium contrast agent). The cervical spinal cord was then removed and immersed in the same fixative solution for 1 week, changing the wash 4 times. Next, the sample was washed with the PBS-Gadolinium mixture (1X PBS and 1.0 mM Gadolinium) for 3 days before imaging, changing the wash 3 times a day.

For hippocampus imaging, the hippocampus was prepared using a similar protocol to that for the spinal cord but employed a different fixative solution (1X PBS, 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde, and 1.0 mM Gadolinium).

Before imaging, samples were inserted into a 3 mm diameter NMR tube (Wilmad Glass), shortened to ~4 cm in length, and filled with Fomblin (Solvay Solexis, Thorofare, NJ, USA). After loading the sample into the micro-imaging probe, two rubber stoppers sealed the capillary and the opening of the Fomblin-filled well (Fig. 6u). The well was then sealed from the top with a cap containing an O-ring.

MR microscopy of spinal cord and hippocampus

For tissue MR microscopy, micro-solenoids were optimized for a 3 mm diameter sample NMR tube using the method described in the Methods (Optimization of the micro-solenoid geometry) and validated in the Results (Validation of the optimization algorithm for micro-solenoid geometry). A 6-turn solenoid using \(\sim\)0.7 mm copper wire was employed for spinal cord imaging, while a 5-turn solenoid with the same thickness was designed for hippocampus imaging. The same imaging hardware was used as described previously.

A 3D FLASH sequence was used to image the excised mouse spinal cord with parameters: flip angle: 64° (Ernst angle), TR = 75 ms, TE = 7.53 ms, number of acquisitions = 56, image matrix = 650 × 200 × 200, FOV = 9.5 × 3 × 3 mm3, resolution = 14.62 × 15.00 × 15.00 μm3, receiver bandwidth = 65,789 Hz, Scan time = 46 hours.

For mouse hippocampus imaging, a 3D FLASH sequence was used with parameters: flip angle = 58° (Ernst angle), TR = 150 ms, TE = 7.40 ms, number of acquisitions = 16, image Matrix = 480 × 260 × 260, FOV = 7 × 4 × 4 mm3, resolution = 14.58 × 15.38 × 15.38 μm3, receiver bandwidth = 50,000 Hz, scan time = 45 h.

Temperature control and monitoring were part of all imaging sessions. Bore temperature was continuously monitored using an MR-compatible thermoprobe placed on the coil housing adjacent to the sample. In prolonged 3D scans with high gradient duty cycles, small temperature increases were observed at the coil housing, consistent with gradient-induced heating but not RF heating of the sample. A custom-built low-noise fan (Fig. 6t) provided continuous room-temperature airflow into the bore, which maintained thermal stability with an absolute temperature change of less than 2 °C during data acquisition (Supplementary Fig. 8). Only data acquired during periods of stable temperature, as confirmed by continuous monitoring, were included in the final image averaging.

After reconstruction, the repeated 3D images were registered and averaged in MATLAB.

Histology

Once the MR imaging was performed, the samples were stored in 10% formalin and later fixed in 70% ethanol. Next, the tissues were embedded in paraffin and serially sectioned to 5 μm thickness using a microtome. Tissue sections were placed on glass slides and stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E), Luxol Fast Blue (LFB), and Cresyl Violet (CV). Brightfield Whole Slide Imaging of all the stained slides was performed with a Leica SCN400 Scanner at 20X magnification (0.5 μm/pixel).

Data availability

All numerical simulations, imaging, and analysis datasets generated in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

All codes and 3D-printed part designs used in this study are available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/BibekDhakal977/microSolenoidGeometryOptimizer.git). The numerical simulations were performed in MATLAB R2023a software, and the designs were created in SolidWorks2018 software.

References

Glover, P. & Mansfield, S. P. Limits to magnetic resonance microscopy. Rep. Prog. Phys. 65, 1489–1511 (2002).

Benveniste, H. & Blackband, S. MR microscopy and high resolution small animal MRI: applications in neuroscience research. Prog. Neurobiol. 67, 393–420 (2002).

Aguayo, J. B., Blackband, S. J., Schoeniger, J., Mattingly, M. A. & Hintermann, M. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging of a single cell. Nature 322, 190–191 (1986).

Cho, Z. H. et al. Recent progress in NMR microscopy towards cellular imaging. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 333, 469–475 (1990).

Ciobanu, L., Webb, A. G. & Pennington, C. H. Magnetic resonance imaging of biological cells. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 42, 69–93 (2003).

Weiger, M. et al. NMR microscopy with isotropic resolution of 3.0 μm using dedicated hardware and optimized methods. Concepts Magn. Reson. 33B, 84–93 (2008).

Lee, S.-C. et al. One Micrometer Resolution NMR Microscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 150, 207–213 (2001).

Krug, J. R. et al. Assessing spatial resolution, acquisition time and signal-to-noise ratio for commercial microimaging systems at 14.1, 17.6 and 22.3 T. J. Magn. Reson. 316, 106770 (2020).

Lee, C. H., Blackband, S. J. & Fernandez-Funez, P. Visualization of synaptic domains in the Drosophila brain by magnetic resonance microscopy at 10 micron isotropic resolution. Sci. Rep. 5, 8920 (2015).

Hüfken, T. et al. Magnetic resonance microscopy for submillimeter samples in a horizontal MR scanner. Sci. Rep. 14, 23583 (2024).

Cho, Z. H. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance microscopy with 4 micron resolution: Theoretical study and experimental results: NMR microscopy with 4 micron resolution. Med. Phys. 15, 815–824 (1988).

van Schadewijk, R. et al. Magnetic Resonance Microscopy at Cellular Resolution and Localised Spectroscopy of Medicago truncatula at 22.3 Tesla. Sci. Rep. 10, 971 (2020).

van Schadewijk, R. et al. MRM Microcoil Performance Calibration and Usage Demonstrated on Medicago truncatula Roots at 22 T. JoVE 2021, 1–20 (2021).

Flint, J. J. et al. Magnetic resonance microscopy of mammalian neurons. NeuroImage 46, 1037 (2009).

Flint, J. J. et al. Cellular-level diffusion tensor microscopy and fiber tracking in mammalian nervous tissue with direct histological correlation. NeuroImage 52, 556–561 (2010).

Flint, J. J. et al. Magnetic resonance microscopy of human and porcine neurons and cellular processes. NeuroImage 60, 1404–1411 (2012).

Lee, C. H. et al. Magnetic Resonance Microscopy (MRM) of Single Mammalian Myofibers and Myonuclei. Sci. Rep. 7, 39496 (2017).

Hoult, D. I. & Richards, R. E. The signal-to-noise ratio of the nuclear magnetic resonance experiment. J. Magn. Reson. 24, 71–85 (1976).

Hoult, D. I. & Lauterbur, P. C. The sensitivity of the zeugmatographic experiment involving human samples. J. Magn. Reson. 34, 425–433 (1979).

Callaghan, P. T. Principles of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Microscopy. (Oxford University Press, 1991).

Minard, K. R. & Wind, R. A. Solenoidal microcoil design. Part II: Optimizing winding parameters for maximum signal-to-noise performance. Concepts Magn. Reson. 13, 190–210 (2001).

Peck, T. L., Magin, R. L. & Lauterbur, P. C. Design and Analysis of Microcoils for NMR Microscopy. JMR 108, 114–124 (1995).

Neuberger, T. & Webb, A. Radiofrequency coils for magnetic resonance microscopy. NMR Biomed. 22, 975–981 (2009).

Ratering, D., Baltes, C., Nordmeyer-Massner, J., Marek, D. & Rudin, M. Performance of a 200-MHz cryogenic RF probe designed for MRI and MRS of the murine brain. Magn. Reson. Med 59, 1440–1447 (2008).

Hardy, B. M. et al. A cryogenic tune and match circuit for magnetic resonance microscopy at 15.2 T. J. Magn. Reson. Open 18, 100147 (2024).

Ciobanu, L., Seeber, D. A. & Pennington, C. H. 3D MR microscopy with resolution 3.7 μm by 3.3 μm by 3.3 μm. J. Magn. Reson. 158, 178–182 (2002).

Chen, H.-Y. & Tycko, R. Low-temperature magnetic resonance imaging with 2.8 μm isotropic resolution. J. Magn. Reson. 287, 47–55 (2018).

Dhakal, B. High-Resolution MR Microscopy of Mouse Spinal Cord at 15.2 T. in Proceedings of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (Singapore, 2024).

Minard, K. R. & Wind, R. A. Solenoidal microcoil design. Part I: Optimizing RF homogeneity and coil dimensions. Concepts Magn. Reson. 13, 128–142 (2001).

Hoult, D. I. & Richards, R. E. The signal-to-noise ratio of the nuclear magnetic resonance experiment. J. Magn. Reson. 213, 329–343 (2011).

Hardy, B. M. et al. Experimental demonstration of diffusion limitations on resolution and SNR in MR microscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 352, 107479 (2023).

Wang, N., White, L. E., Qi, Y., Cofer, G. & Johnson, G. A. Cytoarchitecture of the mouse brain by high resolution diffusion magnetic resonance imaging. NeuroImage 216, 116876 (2020).

Johnson, G. A. et al. Merged magnetic resonance and light sheet microscopy of the whole mouse brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 120, e2218617120 (2023).

Lehtinen, J. et al. Noise2Noise: Learning Image Restoration without Clean Data. in vol. 80, 2965–2974 (PMLR, Stockholm, 2018).

Seeber, D. A., Hoftiezer, J. H., Daniel, W. B., Rutgers, M. A. & Pennington, C. H. Triaxial magnetic field gradient system for microcoil magnetic resonance imaging. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 71, 4263–4272 (2000).

Flint, J. J. et al. Magnetic resonance microscopy of mammalian neurons. NeuroImage 46, 1037–1040 (2009).

Eroglu, S., Gimi, B., Roman, B., Friedman, G. & Magin, R. L. NMR spiral surface microcoils: Design, fabrication, and imaging. Concepts Magn. Reson 17B, 1–10 (2003).

Olson, D. L., Peck, T. L., Webb, A. G., Magin, R. L. & Sweedler, J. V. High-Resolution Microcoil 1H-NMR for Mass-Limited, Nanoliter-Volume Samples. Science 270, 1967–1970 (1995).

Harrison, W. H., Arakawa, M. & McCarten, B. RF coil coupling for MRI with tuned RF rejection circuit using coax shield choke. US patent 4682125 (1988).

Lu, M., Yang, Y., Chai, S. & Yan, X. Float solenoid balun for MRI. NMR Biomed. 38, e5292 (2025).

Brown, R. W., Cheng, Y.-C. N., Haacke, E. M., Thompson, M. R. & Venkatesan, R. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Physical Principles and Sequence Design. (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) for Deep Tissue Imaging. The authors would like to thank Gary Drake, Zou Yue, Jingping Xie, and Shuyang Chai for their help at different stages in the probe development, tissue preparation, and histology, Dan Colvin for constant support during the MR imaging, Xinqiang Yan for advice regarding the coil development, and Xiaoyu Jiang for constant feedback and support at different stages of the work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.D., B.M.H. and J.C.G. contributed to the design of the imaging probe. B.D. and B.M.H. carried out probe development. B.D. conducted the imaging experiments, performed the formal analysis, and drafted the manuscript. J.C.G., A.W.A. and M.D.D. contributed to project administration and funding acquisition. J.X., M.D.D. and A.W.A. provided guidance and feedback throughout the probe design, development, imaging, and data analysis. J.C.G., J.X., B.M.H. and M.D.D. provided feedback during manuscript preparation. J.C.G. supervised the overall project. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dhakal, B., Hardy, B.M., Anderson, A.W. et al. A practical prescription for magnetic resonance microscopy in a horizontal bore magnet. npj Imaging 3, 64 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44303-025-00129-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44303-025-00129-4