Abstract

Heatwaves, wildfires, aerosol pollution, and their compound occurrences are increasingly recognized as severe threats with profound societal and environmental consequences. However, their global ptterns and associated exposure inequalities remain insufficiently understood. On the basis of multisource satellite and reanalysis data, we explore spatiotemporal variations of individual and compound hazards of heatwaves, wildfires, and aerosol pollution globally over 2002–2023. Exposure inequality is further assessed from both demographic and socioeconomic perspectives. Results reveal a widespread increase in heatwaves and related compound events, particularly during boreal summer and autumn, while wildfires and related compound events exhibit greater spatial and temporal heterogeneity. Despite less frequent, compound events lead to significantly greater exposure inequality. Demographic inequality generally declines, while socioeconomic disparities intensify over the past two decades. Economically disadvantaged regions are disproportionately facing higher and faster-growing exposure. These findings underscore the urgent need to incorporate compound hazard risk and inequality into climate adaptation and public health strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, heatwaves have become more frequent, longer-lasting, and intense across the globe, primarily due to human-induced climate change1,2,3,4. It was reported that since the 1970s, the number of extreme heat events has doubled in a range of mid-latitude and tropical belts5. Severe heatwaves not only cause direct health impacts6 and increase stress on infrastructure7 but also create highly flammable landscapes by drying out vegetation and reducing soil moisture8. Prolonged exposure to extreme heat accelerates drying of vegetation and lowers fuel moisture content, significantly raising the risk of wildfire ignition and propagation9. Coinciding with increasing heatwaves, wildfire activity has also intensified in recent decades10. Direct links between heatwaves and fires have been reported11,12,13. Studies indicated that the annual burned area in several fire-prone regions, such as western North America, southern Europe, and parts of Australia, has increased markedly, with climate-driven fuel aridity playing a dominant role14,15,16. Wildfires pose serious threats to ecosystems17, properties18, and human life19. Moreover, they emit large amounts of pollutants into atmosphere, including black carbon and fine particulate matter (PM2.5)20, leading to widespread and persistent aerosol pollution21.

Both public health and ecosystems are threatened by heatwaves, wildfires, and aerosol pollution. Heatwaves have been linked to increased mortality and morbidity, particularly among vulnerable populations such as the elderly, children, and individuals with pre-existing health conditions22. Heatwaves also disrupt ecological balance by affecting species’ physiology, survival, and interactions, leading to shifts in population dynamics and community structures23,24. Similarly, wildfires further exacerbate ecosystem disruption by directly combusting vegetation, altering soil chemistry25, and triggering long-term changes in vegetation and species composition26. Wildfire-generated aerosols can be transported over thousands of kilometers, degrading air quality across regions far remote from fire sources27. Intense wildfires even inject smoke into the stratosphere28, where particles persist for months, destroy stratospheric ozone29, influence radiative balance, and contribute to regional and global climate anomalies30. Wildfire smoke has been associated with respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses31,32,33, while chronic exposure to elevated PM2.5 levels is a well-established cause for premature death34. When these hazards occur concurrently or sequentially, their impacts on human health and earth's environments are likely to be synergistically amplified, resulting in compound stressors and placing disproportionate burdens on exposed communities35,36. The intertwined nature of heatwaves, wildfires, and aerosol pollution, along with the amplified damages of their co-occurrence, highlights the urgent need to examine these hazards not only individually but also as interacting and compounding threats in a warming world37.

It is crucial to note that the risks posed by these environmental hazards are not shared equally. Socioeconomic factors significantly influence exposure and vulnerability to climate-related hazards. Marginalized and low-income populations that often reside in high-risk areas with inadequate adaptive infrastructure face greater health and economic challenges38. These disparities underscore the importance of examining not only the frequency and intensity of climate hazards, but also the unequal distribution of population exposure across regions and socioeconomic groups. An increasing number of studies have examined compound heatwave–wildfire or wildfire–aerosol events. However, existing studies have largely been confined to specific regions39,40, such as Europe41,42 parts of the United States43,44, and Canada45. A global study that focuses on compound events across diverse climatic, seasonal, and socioeconomic contexts remains lacking. Moreover, while a number of studies have examined inequalities in exposure to individual climate hazards46 such as heatwaves47,48, the unequal distribution of risks from concurrent exposure to heatwaves, wildfires, and air pollution has received limited attention.

To tackle the challenges mentioned above, we present here a global-scale analysis to reveal variations in human exposure to co-occurring heatwaves, wildfires, and aerosol pollution events, using multi-source data from satellites, statistical records, and reanalysis products spanning the period of 2002–2023. In addition, exposure inequality was assessed from two complementary perspectives: population-based exposure inequality (demographic inequality), quantified by the Gini index (GI), and socioeconomic inequality, based on comparative analysis among groups stratified by gross domestic product (GDP) and a modified version of GI. By integrating exposure and socioeconomic data, we also identified and mapped global hotspots of vulnerable regions, providing a spatial reference for prioritizing adaptive responses. These findings advance our understanding of compound climate risks in socially and economically differentiated contexts and offer evidence that supports more equitable strategies for climate adaptation and public health planning.

Results

Spatiotemporal patterns of individual and compound hazard frequencies

This study integrates three key datasets to characterize heatwaves, wildfires, and aerosol pollution: daily maximum air temperature from the ERA5 reanalysis; active fire detections from MODIS Collection 6.1; and aerosol optical depth (AOD) from the Long-term Gap-free High-resolution Air Pollutants dataset (LGHAP v2)49. The fire and AOD data were resampled to a consistent spatiotemporal resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°.

Heatwave (H) shows a mean global annual occurrence frequency of 14.54 days, with slightly higher occurrences in western coastal areas of North America and India (Fig. 1A). Aerosol pollution (P) occurrence frequency exhibits smaller spatial variations, with a mean global annual occurrence frequency of 35.85 days (Fig. 1C). Most of the fire (F) days occur in Africa (56.89% of total day-grids globally, Table S1), followed by South America (17.13%) and Asia (16.04%), with the annual occurrence frequency reaching more than 100 days in some regions (Fig. S1). Compound events exhibit a significantly lower occurrence frequency compared to individual hazard events. The spatial distributions of heatwave-fire compound events (HF) and fire-pollution compound events (FP) show a pattern similar to that of fires, with high frequencies observed in Africa (41.93% for HF and 50.70% for FP). Notably, HF events also demonstrate a moderate frequency in Eastern Europe, where Europe as a whole accounts for only 3.89% of global fire days, yet the percentage of HF events rises to 7.35%. Similarly, the northeastern part of Europe also experiences a high frequency of heatwave-pollution compound events (HP), while other HP hotspots are found in regions such as southern Africa and the southeastern Mediterranean. Regarding triple compound events (HFP), in addition to the high frequency in Africa and South America, it is worth noting the elevated occurrence rates in high-latitude areas of the Northern Hemisphere.

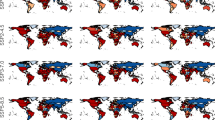

The frequency of heatwaves exhibits an increasing trend across most regions globally (Figs. 2A and S2), with the notable exception of northern India, where a significant decline is observed. The global overall increasing rate reaches 583,984 day-grids per year, indicating a widespread and rapid escalation. Remarkable escalations occur in 2015 and 2023, during which the spatiotemporal extents of heatwaves doubled compared to the preceding year. The interannual variations in wildfires and aerosol pollution demonstrate pronounced spatial heterogeneity (Fig. 2B, C). Regions experiencing a significant increase in fire frequency include southern Africa, India, and central-eastern to northeastern China, whereas notable declines are observed in South America, northwestern Asia, and eastern Europe. Aerosol pollution exhibits significant decreases in southeastern North America, eastern Europe, and southeastern Asia, while notable increases are observed in northwestern North America, South America, and western Asia.

A–H The spatial distributions of interannual variation trends. The bar charts above each map illustrate the total number of global event days per year. Red, blue, and gray bars represent significant increasing trends, significant decreasing trends, and insignificant trends, respectively, as indicated by the linear slope. The values in the bottom right corner represent the global interannual trend rate derived from linear regression. The symbols in parentheses denote the results of the Mann–Kendall (MK) test, where ↑, ↓, and – represent increasing trends, decreasing trends, and no trend, respectively. An asterisk (*) denoting statistical significance (p < 0.05). The maps below depict the spatial distributions of interannual trend rates; only grid cells with statistically significant linear trends (p < 0.05) are shown. H presents the multi-year mean frequencies (represented by the total number of day-grids where events occurred) across seasons. Grid colors reflect the relative frequency ranking across the four seasons, from the least to the most frequent. I The interannual trend rates for different seasons. DJF, MAM, JJA, and SON represent December-January-February, March-April-May, June-July-August, and September-October-November, respectively, corresponding to boreal winter, spring, summer, and autumn.

Compound events associated with heatwaves, including HF, HP, and HFP events, also exhibit an overall upward trend, although the increasing trend of HFP frequency was not significant (Fig. 2D, E, G). Regions with a significant increase in the frequency of HF and HFP events are primarily located in Africa, South America, and southeastern Asia. In contrast, HP events exhibit a predominantly significant increase across most regions, except for the northeastern America and southeastern China. This result suggests that, against the backdrop of climate change and global warming, there has been a widespread increase in the frequency of heatwaves and heatwave-related compound extreme events. The spatial pattern of interannual variations in FP compound events closely aligns with that of fires (Fig. 2F), showing significant declines in South America, eastern Europe, and northwestern Asia, while exhibiting notable increases in Africa and southern Asia.

The implementation of day-specific thresholds in this study facilitates a discussion on seasonal disparities. Heatwaves, wildfires, aerosol pollution, and their compound events are most severe during the boreal summer (June-July-August, JJA), followed by the boreal autumn (September-October-November, SON) (Fig. 2H). Heatwaves and heatwave-related compound events (H, HF, HP, HFP) consistently exhibit increasing interannual trends across all seasons, with the most rapid increase occurring in SON. Notably, the growth rate of triple compound events during SON is five times higher than that observed in other seasons on average. In contrast, wildfires and FP events show declining trends in all seasons, with the steepest decreases also found in SON. These patterns suggest that climate-related hazards in the boreal autumn season are undergoing particularly rapid changes, highlighting the need for heightened attention and further investigation. A more detailed analysis of seasonal variations is provided in the Supporting Information (SI).

Demographic inequality in exposure to individual and compound hazards

Figure 3 presents a quantitative analysis of inequality in population exposure (Fig. S3) to heatwaves, wildfires, aerosol pollution, and their compound events using GI. The results indicate that exposure to heatwaves and aerosol pollution exhibits low and very low levels of inequality, with GI values of 0.23 (Fig. 3A) and 0.08 (Fig. 3C), respectively. In contrast, fire exposure demonstrates a high degree of inequality, with a GI of 0.61 (Fig. 3B). Annual GI analysis reveals that inequalities in heatwave and fire exposure have been decreasing at rates of 0.0055 and 0.0014 per year, respectively. By comparison, the inequality in aerosol pollution exposure has been increasing significantly over time, with the GI rising at a rate of 0.0026 per year.

A–G The Lorenz curves and corresponding GI values. The bar charts above the Lorenz curves display the annual GI values from 2002 to 2023. Purple, cyan, and gray bars represent significant increasing trends, significant decreasing trends, and insignificant trends in GI, respectively, as indicated by the linear slope. The values in the bottom right corner show the global interannual trend rate derived from linear regression, along with the results of the MK test, where ↑, ↓, and – denote increasing, decreasing, and no trends, respectively. An asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05). H The GI values of different hazard events (heatmap) and total GI of all events (bubble chart) across continents. The abbreviations AS, NA, EU, AF, SA, and OC refer to Asia, North America, Europe, Africa, South America, and Oceania, respectively.

Exposure to compound events tends to be more inequitable than exposure to individual hazards, particularly for fire-related compound events. Notably, HF and FP events all exhibit very high levels of inequality, with GI of 0.86 and 0.85, respectively (Fig. 3D, F). GI for HF exposure shows a significant decreasing trend from 2002 to 2023 at a rate of 0.0031 per year. Among the compound events, HP exhibits the lowest exposure inequality, with a GI of 0.59. The triple compound event (HFP) exhibits the highest level of inequality, with the GI approaching 1 (Fig. 3G). GI values for compound events of HFP also exhibit declining trend over the years. We also analyzed exposure inequalities across different continents (Fig. 3H). Overall, Asia and Oceania exhibit the highest levels of inequality, and Africa and South America show the lowest inequality. Specifically, heatwave, wildfire, and pollution events show the highest inequality in Africa (GI = 0.31), Europe (GI = 0.76), and Oceania (GI = 0.13), respectively. For compound events, HF, HP, FP, and HFP exhibit the highest inequality in Oceania (GI = 0.91), South America (GI = 0.66), Europe (GI = 0.94), and Oceania (GI = 0.99), respectively.

Socioeconomic inequality in exposure to individual and compound hazards

Economic development strongly influences a region’s ability to prepare for, mitigate, and respond to extreme heat, wildfires, and pollution, leading to systematic differences in exposure and vulnerability. Incorporating per capita GDP data, we further examined disparities in exposure levels across regions with varying degrees of economic development as displayed in Fig. 4. The analysis reveals significant differences (by Kruskal–Wallis test, Table S2) among GDP-based regional groupings. In most cases, both individual hazard events and compound disasters tend to have lower average exposure levels in economically developed regions compared to less developed areas, with the exposure disparity reaching up to a 7-fold difference between the highest and lowest GDP quartiles (mean ratio: 7.26 ± 0.50). Moreover, the increasing rates in exposure levels are generally higher in lower-GDP regions compared to wealthier ones. For instance, in the case of triple compound events (HFP), the mean exposure level in the lowest GDP quartile exhibits a significant upward trend, increasing by 108 person-days per year. In contrast, the highest GDP quartile shows a slight and statistically insignificant decline of 3 person-days per year (Fig. 4H). A similar pattern is observed across nearly all other types of hazard events, except for heatwaves, where the upper-middle GDP quartile exhibits the most rapid increase in exposure (Fig. 4B). These findings indicate that less developed regions not only experience a disproportionately higher exposure burden but also face a growing disparity with wealthier areas over time, further exacerbating inequality.

A Global distribution of GDP groups categorized into four levels—lowest quartile, lower-middle quartile, upper-middle quartile, and highest quartile—based on the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of the global GDP for the given year. The map illustrates the classification using 2023 data as an example. B–H Interannual variations in mean exposure levels across different GDP groups for various events. Distinct markers represent the average exposure for each GDP group in a given year, with short vertical lines indicating the 95% confidence intervals. Solid lines depict the five-year moving average trends. The numbers at the end of each line represent the interannual variation rates, calculated as the slope of a linear regression fitted to the annual mean exposure data, with units in person-days per year. The symbols in parentheses denote the results of the MK test, where ↑, ↓, and – represent increasing trends, decreasing trends, and no trend, respectively. Asterisks (*) denote statistically significant trends (p < 0.05).

A further quantitative evaluation of socioeconomic exposure inequality measured by modified Gini index (MGI) is presented in Fig. 5. MGI ranges from −1 to 1, where positive values indicate that lower-GDP populations bear disproportionately higher exposure, negative values indicate the opposite, and larger absolute values reflect stronger socioeconomic inequality. Overall, fire and fire-related compound events exhibit substantially greater levels of socioeconomic inequality compared to heatwaves, aerosol pollution, and HP events with larger absolute MGI value. The MGI values for fire-related events are consistently positive, indicating that populations in economically disadvantaged areas bear a disproportionately higher exposure burden (see “Method”). In addition, with the exception of heatwave events, all other event types show a statistically significant increasing trend in MGI values over time, suggesting a worsening of exposure-related socioeconomic inequality across years. Notably, the triple compound event (HFP) exhibits the fastest annual increase in MGI, with a rate of 0.0183 per year. These findings are generally consistent with the group-based analysis presented in Fig. 4, which also indicates increasing disparities across GDP levels. Continent-level MGI analysis (Fig. 5H) reveals that North America and Europe exhibit the highest levels of socioeconomic inequality, particularly for fire and fire-related compound events. In North America, the MGI values for fire, HF, FP, and HFP events reach 0.40, 0.38, 0.45, and 0.40, respectively. We also conducted a country-specific Z-score to GDP data to investigate the inequalities within countries and results are displayed in Supplementary Material (Fig. S4).

A–G The Lorenz curves and corresponding MGI values. The bar charts above the Lorenz curves display the annual MGI values from 2002 to 2023. Purple, cyan, and gray bars represent significant increasing trends, significant decreasing trends, and insignificant trends in MGI, respectively, as indicated by the linear slope. The values in the bottom right corner show the global interannual trend rate derived from linear regression, along with the results of the MK test, where ↑, ↓, and – denote increasing, decreasing, and no trends, respectively. An asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05). H The MGI of different hazard events (heatmap) and total MGI of all events (bubble chart) across continents. The abbreviations AS, NA, EU, AF, SA, and OC refer to Asia, North America, Europe, Africa, South America, and Oceania, respectively.

Hotspot maps for vulnerable regions

Regions with higher GDP generally possess stronger adaptive capacity through better urban planning, fire management, heat mitigation strategies, and pollution control, allowing them to reduce both their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related hazards. In contrast, economically disadvantaged regions often lack the institutional and technological capacity to prevent, detect, or respond effectively to extreme heat, wildfires, or severe air pollution. Through systematic integration of exposure metrics and socioeconomic capacity data, we developed a vulnerability index (VI) to identify critical hotspot regions disproportionately burdened by heatwave, wildfire, and pollution events while exhibiting limited adaptive capacity. As illustrated in Fig. 6, pronounced geographic concentration is revealed, with most of these vulnerable zones located in Africa and Asia. For each type of exposure, we identified the ten countries with the highest VI as representatives of vulnerable regions. The results indicate that 85.71% (60 out of 70) of these countries are located in Africa, 12.86% (9 out of 70) in Asia, and 1.43% (1 out of 70) in North America. Regarding composite hazard events, representative countries of vulnerable regions are predominantly located in Africa, accounting for 92.50% (37 out of 40), with the remaining 7.5% (3 out of 40) situated in Asia. Countries exhibiting high vulnerability across multiple hazard events include Malawi, Burundi, Togo, Sierra Leone, and Gambia etc.

Discussion

Against the backdrop of global climate change, increasing attention has been directed toward heatwave-related compound hazard events. Existing studies have investigated hotspot regions of heatwave–fire compound events9,40,42, their temporal evolution trends45,50, and associated risk assessments39,43. The findings indicate that the frequency and population exposure of compound heatwave–fire events are rising45,50, leading to amplified impacts on human health43 and ecosystems. Our results further demonstrate that compound events were not merely additive in their impacts but also trigger synergistic effects that exacerbate existing vulnerabilities36. Compound events generally exhibit significantly higher levels of exposure inequality than individual hazard events. Their expanding temporal and spatial footprints into densely populated and economically underdeveloped regions further amplify their societal consequences. While most existing studies focus on developed regions such as Europe and North America, our analysis shows that African countries are highly vulnerable to these compound events, particularly those involving fire. This elevated vulnerability arises from the disproportionately high frequency of fires across Africa, compounded by the region’s relatively limited economic capacity to mitigate and respond to such hazards. Therefore, despite their lower frequency, the accelerating occurrence and disproportionate impacts of compound hazards warrant greater scientific attention and stronger policy responses than they currently receive.

We explored exposure inequality to heatwaves, wildfires, pollution, and their compound events from both demographic and socioeconomic perspectives. GI for most hazard types, including heatwaves, wildfires, and HP events exhibited declining trends, suggesting that these hazards had been increasingly affecting a broader portion of the population. In contrast, the analysis based on GDP stratification and MGI revealed a widening socioeconomic disparity. Regions with lower economic development were disproportionately burdened by higher exposure risks, and the gap in exposure between high- and low-GDP groups has been expanding over time with an increasing MGI. This indicates a growing socioeconomic inequality in exposure to these environmental hazards. Economically developed regions generally possess stronger capacities to cope with climate-related hazards—including more effective policies, better healthcare systems, and advanced technologies—which helps reduce their overall exposure. The opposing trends observed in these two dimensions of inequality highlight an important and concerning point. Although the overall population experiencing environmental hazards has expanded, the distribution of impacts remains uneven. Economically disadvantaged regions bear a disproportionately greater burden. These findings underscore the urgent need for targeted attention and adaptation strategies in vulnerable and low-income regions to prevent the further exacerbation of socioeconomic inequality under a changing climate.

While this study provides a comprehensive global assessment of compound events involving heatwaves, wildfires, and aerosol pollution, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, we utilized the GI and GDP-based group comparisons to assess inequality, which may not fully reflect the multidimensional nature of vulnerability. Factors such as health status, infrastructure resilience, or institutional capacity should be considered. Incorporating more granular, multidimensional socioeconomic indicators (e.g., healthcare access, housing quality, or education level) would allow for a more nuanced analysis of risk and vulnerability51. Second, the compound events analyzed here were limited to synchronous occurrences of heatwaves, wildfires, and pollution. However, cascading or lagged effects, where one hazard triggers or intensifies another over time, may also play a critical role in amplifying risks52,53. Future studies could consider these temporal dependencies. Third, uncertainties in our results may arise from several sources. The underlying exposure and socioeconomic data are derived from diverse satellite and reanalysis products, each with inherent measurement errors and methodological assumptions. Moreover, differences in spatial resolution across datasets (e.g., finer-scale fire and AOD grids versus coarser-scale temperature and population data) may introduce spatial mismatches, potentially affecting the accuracy of exposure and inequality estimates. While resampling techniques were applied to harmonize these datasets, residual uncertainties remain and warrant cautious interpretation.

Methods

Data collection and preprocessing

Air temperatures were obtained from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset, the fifth generation of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) reanalysis54. ERA5 provides global high-resolution meteorological variables for the past 8 decades. In this study, ERA5 post-processed daily statistics on single levels from 1940 to present were used, specifically daily maximum 2-m air temperatures at a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°. Active fire observations were derived from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Collection 6.1 active fire product (MCD14DL)55, which detects thermal anomalies using mid-infrared and thermal-infrared signatures from the MODIS sensors aboard Terra and Aqua satellites. The active fire data were distributed by the Fire Information for Resource Management System of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). To ensure spatial consistency with ERA5 dataset, the original 1-km resolution fire counts were aggregated into 0.25° × 0.25° grids by summing the number of fire pixels within each grid cell. Aerosol pollution was assessed using AOD from the Long-term Gap-free High-resolution Air Pollutants dataset (LGHAP v2)49. LGHAP v2 provides gap-free daily 1-km AOD records from 2000 to 2023, generated through an advanced data fusion framework integrating satellite retrievals, ground-based measurements, and numerical model outputs. Compared to the original satellite AOD products, the gap-free AOD distribution provided by LGHAP v2 can reduce the uncertainty in experimental analysis caused by missing satellite observations. In this study, daily AOD data were utilized to represent aerosol pollution level and were resampled to 0.25° × 0.25° grids to align with the spatial resolution of ERA5.

Population distribution was represented using the LandScan Global Population Dataset56, developed by Oak Ridge National Laboratory. LandScan Global provides annual estimates of ambient (24-h average) population at a 30 arc-s (~1 km) resolution from 2000 to 2023. Using an innovative approach that combines geospatial science, remote sensing technology, and machine learning algorithms, LandScan Global offers the highest-resolution data for global population distribution. Same as AOD data, it was resampled to 0.25° × 0.25° grids. The GDP data were sourced from a downscaled gridded global dataset that provides GDP per capita from 1990 to 202257. This dataset offers high-resolution estimates down to the second administrative level, encompassing 43,501 administrative units. It integrates reported subnational GDP data from 89 countries and 2708 subnational divisions with machine learning-based downscaling algorithms, making it an invaluable resource for detailed economic assessments over the past three decades. For this study, the 0.25° × 0.25° gridded product was employed, and GDP data for the year 2023 were substituted with those from 2022.

Definition of hazard events

Heatwave events were defined as periods of at least three consecutive days when daily maximum temperatures exceed a predefined threshold2. The threshold was determined as the 90th percentile of daily maximum temperatures at a given grid point, calculated within a 9-day sliding window centered on the specific day over the study period from 2002 to 2023. Previous studies used sliding windows with lengths ranging from 1 day to a full month4,9,11,43,58,59. In this research, we opted for an intermediate window length of 9 days41. For each day at every grid point, a total of 198 data points, derived from 22 years of observations within the 9-day window, were utilized to determine the 90th percentile as the threshold for that specific day and location. This dynamic threshold approach that accounts for regional and seasonal variations and allows for a more accurate reflection of local anomalies has been widely adopted in recent studies2,60,61,62 as a preferred alternative to the fixed-threshold method.

Polluted days were defined as days when AOD exceeds a specified threshold. Similar to heatwaves, the threshold was set as the 90th percentile of daily AOD values at each grid point, computed within a 9-day sliding window centered on the given day across the study period. The spatial distributions of the thresholds used for heatwave and pollution events for examples of two specific days are shown in Fig. S5. Fire events were identified where a grid contains two or more fire counts on a given day. The necessity for two fire points helped mitigate the impact of observational errors, ensuring that only significant fire occurrences were considered and minimizing the potential for misclassifying due to isolated or spurious data points. A compound hazard event was defined as the simultaneous occurrence of two or more individual hazard events (heatwave, fire, or pollution) within the same grid cell on a given day. The concurrent manifestation of all three hazard types (HF-pollution) was also named a triple compound event. We also tested the sensitivity of our results by adopting broader temporal windows to define compound events, and the outcomes of these analyses are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Fig. S6).

To systematically classify and analyze compound hazard events that multiple types of disasters occur simultaneously, we utilized an encoding system41. When temperature, fire, and AOD data were analyzed, each grid cell on a given day was assigned a numerical value based on existing specific hazard events. We used 1 for heatwave occurrence, 2 for fire occurrence, 4 for pollution occurrence, and 0 if no hazard event was present. The occurrence of both single and compound hazard events was then determined by summing these values, as outlined in Table S3. Finally, we analyzed the annual occurrence frequency for each type of hazard event and compound hazard event by computing the total number of days per year.

Assessment of demographic inequality

Exposure was defined as the number of person-days that people are impacted by certain hazard events in a year47:

where Di,j,k represents the total days of occurrence for hazard event type k in year j for grid i, and Pi,j represents the population in year j for grid i.

To assess the inequality in the exposure distribution across different people (i.e., demographic inequality), we constructed Lorenz curves and computed the Gini index (GI) for various exposure types. The Lorenz curve is a widely used graphical representation of inequality63, originally proposed in the field of economics64 and later widely applied in medicine, environmental science, and other disciplines60,65,66,67. The x-axis usually represents the cumulative share of the population, and the y-axis represents the cumulative share of targeted variable. If the targeted variable is perfectly evenly distributed, the Lorenz curve will follow the line of equality (i.e., the 45° diagonal). The degree of inequality is quantified by the deviation of the Lorenz curve from this diagonal, which is expressed by the GI. GI is defined as twice the area between the Lorenz curve and the line of perfect equality, expressed as:

Where A is the area under the Lorenz curve L(p) (\(A={\int }_{0}^{1}L(p)\), the shaded area in Fig. S7), L(p) describes the cumulative proportion of targeted variable held by the bottom p fraction of the population. GI ranges from 0 to 1, 0 indicates perfect equality (i.e., all population groups experience the same exposure), and 1 represents maximum inequality (i.e., all exposure is concentrated in a single individual or unit). A more detailed calculation process is provided in Supporting Information (SI).

Given our spatial analysis using gridded datasets, where both population and exposure parameters were aggregated at the grid-cell level, we implemented a population-weighted calculation48,65 when we plotted the Lorenz curve and calculated GI. Specifically, grid cells were first ranked in ascending order based on their exposure values. The x-axis of the Lorenz curve represents the cumulative share of the total population across these ranked grid cells, while the y-axis represents the cumulative share of total exposure of different grid cells (rather than individuals). The GI values were classified into five tiers to quantify environmental exposure disparities: very low inequality (<0.2), low inequality (0.2–0.4), moderate inequality (0.4–0.6), high inequality (0.6–0.8), and very high inequality (≥0.8)66.

Assessment of socioeconomic inequality

We classified data points into four groups based on the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of GDP values: lowest GDP quartile (≤25th percentile), lower-middle GDP quartile (25th–50th percentile), upper-middle GDP quartile (50th–75th percentile), and highest GDP quartile (>75th percentile). To assess whether exposure levels significantly differ across GDP groups, we conducted a Kruskal–Wallis test68, a non-parametric method for comparing multiple independent samples. If significant differences were detected, we computed the mean exposure within each GDP group and visualized its interannual variations for comparative analysis. Additionally, we applied linear regression to estimate the rate of interannual change in exposure, where the slope of the fitted trend line represents the rate of change. A significance test was also performed to assess the statistical significance of the trends.

In addition, we employed a modified GI69,70 (MGI, or referred to as the cumulative environmental hazard inequality index as in Jason G. Su, et al.69) to quantify exposure inequality in relation to socioeconomic status (i.e., socioeconomic inequality). Unlike the classical GI, where data are ranked based on exposure levels, MGI ranks the data by their corresponding GDP values in descending order. Accordingly, the resulting Lorenz curve captures the relationship between cumulative exposure and cumulative population share ordered by socioeconomic status. While the traditional GI is a univariate measure of inequality, MGI introduces socioeconomic variables into the analysis, allowing for the assessment of exposure inequality in relation to socioeconomic attributes70.

The computational definition of MGI remains the same: it is defined as twice the area between the Lorenz curve and the line of perfect equality. If populations with higher GDP levels experience lower exposure, while those with lower GDP levels are exposed more severely, the Lorenz curve will initially rise slowly (i.e., a lower slope at high GDP levels) and accelerate later (i.e., a steeper slope at low GDP levels). In this case, the Lorenz curve lies below the line of equality, resulting in a positive MGI (red curve in Fig. S7B). Conversely, if higher-GDP populations bear greater exposure compared to lower-GDP populations, the Lorenz curve lies above the line of equality, and MGI becomes negative (blue curve in Fig. S7B). The theoretical range of MGI spans from −1 to 1, where values near ±1 indicate extreme socioeconomic inequality (or environmental injustice).

It is important to note that, although the GI and the MGI share a highly similar computational formulation, their values are not directly comparable due to differences in data ranking. Specifically, a lower MGI value (absolute value) compared to GI does not necessarily indicate a lower level of socioeconomic inequality (GDP-based) relative to demographic inequality (population-based). The inequality classification based on GI values discussed earlier is also not applicable to MGI.

Assessment of vulnerability

We assigned scores to the exposure and GDP data to assess regional vulnerability. For the exposure data, a score of 0 was assigned when the value was 0. For non-zero exposure values, we calculated the 10th, 20th, …, 90th percentiles and divided the data into ten intervals. The lowest interval was assigned a score of 1, while the highest was assigned a score of 10 (ZEXP). In contrast, the GDP data were scored in reverse. After dividing GDP values into ten intervals based on percentiles, the highest interval received a score of 1, while the lowest interval was assigned a score of 10 (ZGDP). The final VI was calculated by summing the scores of exposure and GDP, resulting in values ranging from 1 to 20:

Higher VI values indicate greater vulnerability, characterized by high exposure and low economic levels, suggesting that these areas are more susceptible to disasters and should be prioritized for intervention. Country-level VI values were derived by computing the median of pixel-level VI values within each country.

Data availability

MODIS active fire data were provided by the Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS) and are available at https://firms.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/active_fire; LGHAP AOD data can be downloaded from https://zenodo.org/communities/ecnu_lghap/records?q=&l=list&p=1&s=10&sort=newest; Temperature data from ERA-5 are available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/derived-era5-single-levels-daily-statistics?tab=download; Global population data can be obtained from https://landscan.ornl.gov/. GDP data are accessible at https://zenodo.org/records/13943886.

Code availability

The code to carry out the current analyses is available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Valérie Masson-Delmotte, P. Z. et al. Nada Caud Climate Change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change 2 (IPCC, 2021).

Domeisen, D. I. V. et al. Prediction and projection of heatwaves. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 36–50 (2022).

Perkins, S. E., Alexander, L. V. & Nairn, J. R. Increasing frequency, intensity and duration of observed global heatwaves and warm spells. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39 https://doi.org/10.1029/2012gl053361 (2012).

Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. E. & Lewis, S. C. Increasing trends in regional heatwaves. Nat. Commun. 11, 3357 (2020).

Barriopedro, D., García-Herrera, R., Ordóñez, C., Miralles, D. G. & Salcedo-Sanz, S. Heat waves: physical understanding and scientific challenges. Rev. Geophys. 61 https://doi.org/10.1029/2022rg000780 (2023).

Ebi, K. L. et al. Hot weather and heat extremes: health risks. Lancet 398, 698–708 (2021).

Stone, B. Jr. et al. Compound climate and infrastructure events: how electrical grid failure alters heat wave risk. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 6957–6964 (2021).

Libonati, R. et al. Assessing the role of compound drought and heatwave events on unprecedented 2020 wildfires in the Pantanal. Environ. Res. Lett. 17 https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac462e (2022).

Ridder, N. N. et al. Global hotspots for the occurrence of compound events. Nat. Commun. 11, 5956 (2020).

Cunningham, C. X., Williamson, G. J. & Bowman, D. Increasing frequency and intensity of the most extreme wildfires on Earth. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1420–1425 (2024).

Hegedűs, D., Ballinger, A. P. & Hegerl, G. C. Observed links between heatwaves and wildfires across Northern high latitudes. Environ. Res. Lett. 19 https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad2b29 (2024).

Balch, J. K. et al. Warming weakens the night-time barrier to global fire. Nature 602, 442–448 (2022).

Brown, P. T. et al. Climate warming increases extreme daily wildfire growth risk in California. Nature 621, 760–766 (2023).

Abatzoglou, J. T. & Williams, A. P. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11770–11775 (2016).

Bowman, D. M. J. S. et al. Vegetation fires in the anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 500–515 (2020).

Ellis, T. M., Bowman, D., Jain, P., Flannigan, M. D. & Williamson, G. J. Global increase in wildfire risk due to climate-driven declines in fuel moisture. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1544–1559 (2022).

Tang, W. et al. Widespread phytoplankton blooms triggered by 2019-2020 Australian wildfires. Nature 597, 370–375 (2021).

Wang, D. et al. Economic footprint of California wildfires in 2018. Nat. Sustain. 4, 252–260 (2020).

Johnston, F. H. et al. Unprecedented health costs of smoke-related PM2.5 from the 2019–20 Australian megafires. Nat. Sustain. 4, 42–47 (2021).

Burke, M. et al. The contribution of wildfire to PM2.5 trends in the USA. Nature 622, 761–766 (2023).

Xu, R. et al. Global population exposure to landscape fire air pollution from 2000 to 2019. Nature 621, 521–529 (2023).

Gasparrini, A. et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. Lancet 386, 369–375 (2015).

Smale, D. A. et al. Marine heatwaves threaten global biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 306–312 (2019).

Smith, K. E. et al. Biological impacts of marine heatwaves. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 15, 119–145 (2023).

Shakesby, R. A. Post-wildfire soil erosion in the Mediterranean: review and future research directions. Earth Sci. Rev. 105, 71–100 (2011).

Moritz, M. A. et al. Learning to coexist with wildfire. Nature 515, 58–66 (2014).

He, Y. et al. Formation of secondary organic aerosol from wildfire emissions enhanced by long-time ageing. Nat. Geosci. 17, 124–129 (2024).

Yu, P. et al. Black carbon lofts wildfire smoke high into the stratosphere to form a persistent plume. Science 365, 587–590 (2019).

Bernath, P., Boone, C. & Crouse, J. Wildfire smoke destroys stratospheric ozone. Science 375, 1292–1295 (2022).

Yu, P. et al. Persistent stratospheric warming due to 2019–2020 Australian wildfire smoke. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL092609 (2021).

Chen, H., Samet, J. M., Bromberg, P. A. & Tong, H. Cardiovascular health impacts of wildfire smoke exposure. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 18, 2 (2021).

Aguilera, R., Corringham, T., Gershunov, A. & Benmarhnia, T. Wildfire smoke impacts respiratory health more than fine particles from other sources: observational evidence from Southern California. Nat. Commun. 12, 1493 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Respiratory risks from wildfire-specific PM2.5 across multiple countries and territories. Nat. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01533-9 (2025).

Apte, J. S., Marshall, J. D., Cohen, A. J. & Brauer, M. Addressing global mortality from ambient PM2.5. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 8057–8066 (2015).

Bansal, A. et al. Heatwaves and wildfires suffocate our healthy start to life: time to assess impact and take action. Lancet Planet. Health 7, e718–e725 (2023).

Zscheischler, J. et al. Future climate risk from compound events. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 469–477 (2018).

Gao, M. et al. Future intensification of co-occurrences of heat, PM2.5 and O3 extremes in China and India despite stringent air pollution controls. Environ. Res. Lett. 20, 014044 (2025).

Banzhaf, S., Ma, L. & Timmins, C. Environmental justice: the economics of race, place, and pollution. J. Econ. Perspect. 33, 185–208 (2019).

Ducros, G. et al. Multi-hazards in Scandinavia: impacts and risks from compound heatwaves, droughts and wildfires. EGUsphere 2024, 1–25 (2024).

Mario, E. et al. Coupling heat wave and wildfire occurrence across multiple ecoregions within a Eurasia longitudinal gradient. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 169269 (2024).

Sutanto, S. J., Vitolo, C., Di Napoli, C., D’Andrea, M. & Van Lanen, H. A. J. Heatwaves, droughts, and fires: exploring compound and cascading dry hazards at the pan-European scale. Environ. Int. 134, 105276 (2020).

Vitolo, C., Di Napoli, C., Di Giuseppe, F., Cloke, H. L. & Pappenberger, F. Mapping combined wildfire and heat stress hazards to improve evidence-based decision making. Environ. Int. 127, 21–34 (2019).

Chen, C., Schwarz, L., Rosenthal, N., Marlier, M. E. & Benmarhnia, T. Exploring spatial heterogeneity in synergistic effects of compound climate hazards: extreme heat and wildfire smoke on cardiorespiratory hospitalizations in California. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj7264 (2024).

Ratajczak, Z. et al. The combined effects of an extreme heatwave and wildfire on tallgrass prairie vegetation. J. Veg. Sci. 30, 687–697 (2019).

Cleland, S. E., Paul, N., Coker, E. S. & Henderson, S. B. The co-occurrence of wildfire smoke and extreme heat events in British Columbia, 2010–2022: evaluating spatiotemporal trends and inequities in exposure burden. ACS ES&T Air 2, 319–330 (2025).

Zheng, Y., Davis, S. J., Persad, G. G. & Caldeira, K. Climate effects of aerosols reduce economic inequality. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 220–224 (2020).

Alizadeh, M. R. et al. Increasing Heat-Stress Inequality in a Warming Climate. Earths Future 10 https://doi.org/10.1029/2021ef002488 (2022).

Mashhoodi, B. & Kasraian, D. Heatwave exposure inequality: an urban-rural comparison of environmental justice. Appl. Geogr. 164 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2024.103216 (2024).

Bai, K. et al. LGHAP v2: a global gap-free aerosol optical depth and PM2.5 concentration dataset since 2000 derived via big Earth data analytics. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 2425–2448 (2024).

Jones-Ngo, C. G. et al. Increasing exposures to compound wildfire smoke and extreme heat hazards in California, 2011–2020. Earths Future 13 https://doi.org/10.1029/2024ef005189 (2025).

Brulle, R. J. & Pellow, D. N. Environmental justice: human health and environmental inequalities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 27, 103–124 (2006).

Gruber, N., Boyd, P. W., Frölicher, T. L. & Vogt, M. Biogeochemical extremes and compound events in the ocean. Nature 600, 395–407 (2021).

Mukherjee, S., Mishra, A. K., Zscheischler, J. & Entekhabi, D. Interaction between dry and hot extremes at a global scale using a cascade modeling framework. Nat. Commun. 14, 277 (2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorolog. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Giglio, L., Schroeder, W. & Justice, C. O. The collection 6 MODIS active fire detection algorithm and fire products. Remote Sens. Environ. 178, 31–41 (2016).

Lebakula, V. et al. LandScan Global (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN, 2024).

Kummu, M., Kosonen, M. & Masoumzadeh Sayyar, S. Downscaled gridded global dataset for gross domestic product (GDP) per capita PPP over 1990–2022. Sci. Data 12, 178 (2025).

Wu, S. et al. Local mechanisms for global daytime, nighttime, and compound heatwaves. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00365-8 (2023).

Al-Yaari, A., Zhao, Y., Cheruy, F. & Thiery, W. Heatwave characteristics in the recent climate and at different global warming levels: a multimodel analysis at the global scale. Earths Future 11 https://doi.org/10.1029/2022ef003301 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Changes in global heatwave risk and its drivers over one century. Earths Future 12 https://doi.org/10.1029/2024ef004430 (2024).

White, R. H. et al. The unprecedented Pacific Northwest heatwave of June 2021. Nat. Commun. 14, 727 (2023).

Yin, J. et al. Future socio-ecosystem productivity threatened by compound drought–heatwave events. Nat. Sustain. 6, 259–272 (2023).

Chen, B. et al. Contrasting inequality in human exposure to greenspace between cities of Global North and Global South. Nat. Commun. 13, 4636 (2022).

Ceriani, L. & Verme, P. The origins of the Gini index: extracts from Variabilità e Mutabilità (1912) by Corrado Gini. J. Econ. Inequal. 10, 421–443 (2012).

Steinbeis, F., Gotham, D., von Philipsborn, P. & Stratil, J. M. Quantifying changes in global health inequality: the Gini and Slope Inequality Indices applied to the Global Burden of Disease data, 1990-2017. BMJ Glob. Health 4, e001500 (2019).

Song, Y. et al. Observed inequality in urban greenspace exposure in China. Environ Int 156, 106778 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Global future population exposure to heatwaves. Environ. Int. 178, 108049 (2023).

McKight, P. E. & Najab, J. in The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology (Wiley, 2010).

Jason, G. S. et al. An index for assessing demographic inequalities in cumulative environmental hazards with application. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 7626–7634 (2009).

Su, J. G., Jerrett, M., Morello-Frosch, R., Jesdale, B. M. & Kyle, A. D. Inequalities in cumulative environmental burdens among three urbanized counties in California. Environ. Int. 40, 79–87 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3700103), and the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project Nos. C2002-22Y, HKBU12201023, and HKBU12202824), and the China Meteorological Administration Aerosol-Cloud and Precipitation Key Laboratory, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology (KDW2410).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G. and Q.Y. designed the research; Q.Y. conducted the research; Q.Y. and M.G. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Q., Gao, M. Divergent trends in demographic and socioeconomic inequalities of global wildfire and compound hazard exposures. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 109 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00163-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00163-7