Abstract

Nonlinear waveguides harnessing the optical Kerr effect are promising for next-generation photonic technologies due to its ultrafast response, but the weak nonlinearities reported so far have limited practical applications. Here, we explore free-electron-induced Kerr nonlinearities in all-semiconductor waveguides, and we show that longitudinal bulk plasmons—nonlocal excitations—can induce exceptionally strong Kerr nonlinearities. Combining a novel nonlinear eigenmode analysis with semiclassical hydrodynamic theory, we compute the linear and nonlinear optical responses originating from the quantum behavior of free electrons in heavily doped semiconductors. Our waveguides achieve ultrahigh nonlinear refractive indices n2 = −8.93 × 10−16 m2 W−1 and nonlinear coefficients γwg = 4 × 107 W−1 km−1 while supporting modes propagating over 100 μm, all robust under viscoelastic and nonlinear dampings. Finally, we demonstrate efficient nonlinear modulation of the transmittance spectrum of a Mach–Zehnder interferometer made of our all-semiconductor waveguides via the free-electron Kerr effect. This work evidences the transformative potential of free-electron nonlinearities in heavily doped semiconductors for integrated photonics and scalable on-chip nonlinear systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonlinear optical waveguides are at the core of modern photonic technologies and are increasingly promising for next-generation systems in telecommunications, quantum technologies, optical computing, and biomedical sensing1. Among these, Kerr waveguides leverage the optical Kerr effect—a nonlinear optical phenomenon by which the refractive index of a medium changes with light intensity2—to enable critical processes such as self-phase modulation and soliton formation. In fact, refractive index engineering is central to many advancements in both traditional and meta optics3,4. By harnessing the optical Kerr effect, it is possible to achieve efficient and ultrafast photon-photon interactions, which are essential for applications like high-speed optical communication, wavelength conversion, entangled-photon generation, optical switching, modulation, and frequency-comb formation5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Additionally, the growing demands of artificial intelligence platforms have reignited interest in Kerr-based solutions, particularly due to their potential to deliver integrated, low-power, and ultrafast optical modulation. However, despite the Kerr effect’s inherent speed—operating on femtosecond timescales—its relatively weak nonlinearity values reported to date pose a challenge. Conversely, thermal nonlinearities, while potentially stronger, are limited by their slow response times (kHz–MHz timescales)6. Achieving both modulation strength and speed remains therefore a critical challenge for advancing photonic technologies.

Kerr guided-wave optics has long relied on silica fibers, which possess sub-10-μm core diameters and ultralow propagation losses. More importantly, silica fibers have a relatively small nonlinear waveguide coefficient (γwg ≈ 20 W−1 km−1), defined by the ratio between the nonlinear refractive index and the effective mode area, and conventionally used to characterize the Kerr nonlinearity in waveguides. Therefore, silica waveguides typically require extended (meter- to kilometer-scale) interaction lengths14, which makes them suboptimal despite their low losses. Photonic crystal fibers partly address these constraints by using high-nonlinearity SF57 glass and tighter mode confinement, achieving coefficients up to 640 W−1 km−1 15. Silicon-on-insulator (SOI) Kerr on-chip integrated waveguides further enhance nonlinear response through silicon’s large Kerr nonlinearity and strong modal confinement, reaching γwg ≈ 105 W−1 km−1 16,17, but two-photon absorption and free-carrier losses at telecom wavelengths limit both their speed and functionality18,19. Silicon–organic slot waveguides mitigate these issues by confining light within highly nonlinear polymers, attaining γwg ~ 106 W−1 km−1 16,20. Nevertheless, diffraction commonly constrains traditional Kerr guided-wave optics lengths to a few millimeters. Plasmonic platforms can overcome these restrictions by localizing electromagnetic fields below the diffraction limit, enhancing light–matter interactions and enabling the miniaturization of Kerr devices to the nanometer scale21,22,23,24,25. Theoretical projections suggest nonlinear coefficients on the order of 104 W−1 km−1 for nanoshell plasmonic waveguides26, 107 W−1 km−1 in metal-indium tin oxide (ITO)-metal slot waveguides27, while four-wave mixing in short hybrid-plasmonic devices28 holds promise for improved performance in ultra-compact geometries. However, these systems often suffer from high losses or limited scalability.

In this context, heavily doped semiconductors have emerged as promising alternative plasmonic materials for the infrared (IR) band. Apart from benefiting from mature large-scale fabrication, they can strongly confine electromagnetic fields while supporting strong, tunable free-electron (FE) optical nonlinearities29,30. Doped semiconductors transition from the size-quantization regime of quantum dots and wells to the classical regime of plasmon oscillations, where electron–electron interactions can induce strong nonlocal and nonlinear optical responses31. These collective FE oscillations can surpass traditional metal nonlinearities, partly because lower electron densities (1018–1019 cm−3) enhance the third-order polarizability, which, in the limit of small excitations, scales inversely with the square of the FE density, i.e., \(\propto {n}_{0}^{-2}\)32. Heavily doped InP and InGaAs stand out as promising candidates for exhibiting such high FE nonlinearities33, with third-harmonic generation exceeding conventional χ(3) nonlinearities, as recently observed in heavily doped InGaAs nanoantennas32. Additionally, surface carrier density modulation enables reconfigurable FE nonlinearities on ultrafast timescales, outpacing slower thermal mechanisms6,34,35.

Despite their promise, FE-driven effects in heavily doped semiconductors have seen limited deployment in waveguides and on-chip integrated circuits. Past research has largely emphasized bulk χ(3) processes over the many-micrometer propagation distances typical of waveguides, with nonlinear refractive indices n2 typically on the order of 10−17 m2 W−1 or smaller. Although second-harmonic generation via FEs has been reported in metal-insulator-metal waveguides36, FE-driven nonlinearities in semiconductor waveguides—in particular the Kerr effect—have remained elusive. One reason is the significant scale mismatch between the highly localized volumes where FE responses dominate—typically on the order of a few nanometers—and the long propagation lengths of guided modes in hybrid plasmonic waveguides—from hundreds to thousands of microns—which impose stringent computational demands for their design and optimization. Another reason is that FEs typically respond below the plasma frequency, restricting bulk Kerr effects. However, recent work37 has shown that heavily doped semiconductors can support strong nanoscale Kerr nonlinearities above the plasma frequency via longitudinal bulk plasmons (LBPs)—intrinsically nonlocal excitations fulfilling ε(ω, k) = 0 (with ω and k being frequency and wavevector, respectively)37,38,39,40. Historically identified in thin metal films at ultraviolet energies41,42, LBPs have recently been observed at IR frequencies in transparent conducting oxides43 and n-doped InAsSb44. In this work, we integrate LBPs into hybrid designs featuring intrinsic waveguide cores made of undoped III–V semiconductors evanescently coupled to heavily doped III–V semiconductor layers. Using a nonlinear hydrodynamic eigenmode analysis method that we specifically develop here, we demonstrate that the FE Kerr effect enhances the nonlinear refractive index and the waveguide nonlinear coefficient in these hybrid structures to n2 = −8.93 × 10−16 m2 W−1 and γwg ≈ 4 × 107 W−1 km−1, respectively. Crucially, this boost occurs without compromising the low-loss properties inherent to undoped III–V semiconductors, enabling strong nonlinearities over propagation distances exceeding 100 μm. We also demonstrate nonlinear modulation of the transmission spectrum in a Mach–Zehnder interferometer driven by the FE Kerr effect, introducing an ultrafast photonic platform for telecom to mid-IR frequencies.

Results

Hydrodynamic linear response of hybrid heavily doped semiconductor waveguides

From a theoretical perspective, LBP resonances can be excited in finite-size systems if the material response is nonlocal39,45. One way to account for nonlocality in degenerate electron systems is to model the classical FE dynamics together with density-dependent energy potentials that encapsulate their quantum properties. This approach is commonly referred to as hydrodynamic theory (HT)46,47, deriving its name from the fact that FEs are intuitively treated as a fluid. In a preliminary work37, we developed a time-domain electromagnetic model integrated with semiclassical HT that directly captures the linear and nonlinear optical responses arising from the quantum nature of electrons-an often nontrivial task for conventional semiconductor frameworks based on the Schrödinger–Poisson equations48,49,50. Accounting for plasmonic hydrodynamic contributions to Kerr nonlinearity in heavily doped semiconductors, we discovered a strong FE Kerr-type nonlinearity that enables low-threshold bistability-two stable outputs at the same input intensity of 1 mW37. Here, we develop a nonlinear hydrodynamic eigenmode analysis and extend this model to heavily doped semiconductor waveguides, showing that LBPs can indeed drive a very large Kerr effect with strong modulation of the mode’s effective refractive index.

In heavily doped semiconductors, the high concentration of free-carriers dissipates electromagnetic energy through absorption, resulting in ohmic losses. To mitigate this, our design incorporates a hybrid architecture consisting of a 3.5 μm-thick undoped InGaAs core between an InP substrate and a 250-nm-thick InP layer, with a 30-nm-thick heavily doped InGaAs slab on top to modulate the guided mode (Fig. 1a). The undoped InGaAs core, with a low carrier concentration (on the order of 1017 cm−3) significantly suppresses the losses that would otherwise arise predominantly from the heavily doped InGaAs layer. We also consider a 300-nm-thick HfO2 layer and a 300-nm-thick Au layer on top, as these samples could eventually be gated to electrically reconfigure their response35. While this reconfiguration is not explored in this work, we already account for the potential additional losses that these layers could introduce. This configuration supports both transverse electric (TE) and transverse magnetic (TM) modes (see Supplementary Fig. 1 in Supplementary Note 1).

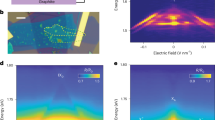

a Schematic of the structure, consisting of a 3.5 μm-thick InGaAs core and an InP cladding, which supports a guided mode. On top, a 30-nm-thick slab of heavily doped InGaAs is placed. The HfO2 and Au layers on top of the waveguide are not drawn here for simplicity. b Absorbance spectra of the free-standing heavily doped InGaAs slab for the two different doping concentrations: n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3 (blue curve) and n0 = 12 × 1018 cm−3 (red curve). The dashed line marks λ0 = 8 μm. c, d Simulated TM (transverse magnetic) electric field amplitude ∣E∣ distributions (not normalized) for n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3 (LBP mode) and n0 = 12 × 1018 cm−3 (SPP mode) at λ0 = 8 μm. The gray shadowing indicates the HfO2 and Au layers on top of the waveguide. e Line profile of the electric field amplitude ∣E∣ (not normalized) along the center of the structure for both doping levels. The LBP mode (blue curve) shows a significant field amplitude compared to the SPP mode (red curve). f Zoomed-in views of the electric field amplitude ∣E∣ profiles (not normalized) for the LBP and SPP modes. The LBP mode exhibits a propagation length Lp = 141 μm due to strong interaction between the guided mode and the heavily doped InGaAs layer, while the SPP mode has a much longer propagation length of Lp = 3690 μm due to lower interaction.

To decode the optical response of the system, it is key to understand the motion of FEs in the heavily doped InGaAs layer. Following the HT31,34,37, the equation of motion involves two macroscopic quantities: the electron density n and velocity v:

where E and H are the electric and magnetic fields, respectively, and me, e, and μ0 are the effective electron mass, electron charge, and vacuum permeability, respectively. Equation (1) incorporates convection (v⋅∇v), dissipation (γ), Coulomb and Lorentz forces, and a quantum pressure term arising from the internal energy functional G[n]. The factor γ phenomenologically accounts for the loss mechanisms in the heavily doped InGaAs system, such as ohmic losses and potential scattering with defects or material inhomogeneities. The total electron density is \(n={n}_{0}+{\sum }_{j}{n}_{j}{{\rm {e}}}^{-i{\omega }_{j}t}\), where n0 is the equilibrium density and nj the perturbed densities at harmonic order j (n2 should not be confused here with the nonlinear refractive index). We adopt the Thomas–Fermi (TF) approximation for G[n] ≃ TTF[n], which is crucial for describing nonlocal effects39. Additional refinements, including electron spill-out, can shift the plasmon resonance slightly46,47, but these are neglected here since they are typically relevant only in single-digit nanometer scales and below. By rewriting Eq. (1) with \(\dot{{\bf{P}}}={\bf{J}}=-ne{\bf{v}}\), we express the optical response through the constitutive relation at the jth harmonic31:

where the first-order TF quantum-pressure term is \(-\nabla \frac{\delta G[n]}{\delta n}=\frac{e{n}_{0}}{{m}_{{ {e}}}}\nabla {(\frac{\delta {T}_{{\rm{TF}}}[n]}{\delta n})}_{1}={\beta }^{2}\nabla (\nabla \cdot {{\bf{P}}}_{j})\). Here, \({\beta }^{2}=\frac{3}{5}{v}_{{\rm{F}}}^{2}=2\frac{{c}_{{\rm{TF}}}}{{m}_{{ {e}}}}{n}_{0}^{2/3},\,{c}_{{\rm{TF}}}=\frac{\hslash }{{m}_{{ {e}}}}\frac{3}{10}{(3{\pi }^{2})}^{2/3}\), where vF is the Fermi velocity51. The “ ⋅” on the variables denotes the time derivative and \({{\bf{S}}}_{{\omega }_{j}}^{{\rm{NL}}}\) is the FE nonlinear source. By combining Eq. (2) and Maxwell’s equations in the frequency domain—i.e., assuming time-harmonic fields \({\bf{F}}({\bf{r}},t)={\sum }_{j}{{\bf{F}}}_{j}({\bf{r}}){{ {e}}}^{-i{\omega }_{j}t}\), where F ∈ {E, H, P}—we have

In Eqs. (3) and (4), we account for the dielectric local contributions from the semiconductor, including both linear effects, represented by the local permittivity ε, and nonlinear effects, characterized by the nonlinear polarization \({{\bf{P}}}_{{\omega }_{j}}^{{\rm{NL}}}\). The coupling between different harmonic frequencies arises from the nonlinear contributions \({{\bf{P}}}_{{\omega }_{j}}^{{\rm{NL}}}\) and \({{\bf{S}}}_{{\omega }_{j}}^{{\rm{NL}}}\). In the linear regime, \({{\bf{P}}}_{{\omega }_{1}}^{{\rm{NL}}}={{\bf{S}}}_{{\omega }_{1}}^{{\rm{NL}}}=0\). The crystal lattice nonlinearities are incorporated through a bulk third-order susceptibility χ(3), described by \({{\bf{P}}}_{{\omega }_{3}}^{{\rm{NL}}}={\varepsilon }_{0}{\chi }^{(3)}({{\bf{E}}}_{1}\cdot {{\bf{E}}}_{1}){{\bf{E}}}_{1}\). Moreover, we set the normal polarization component to zero, \({P}_{n}^{-}={P}_{n}^{+}=0\) (Dirichlet boundary condition) as the required additional boundary condition5,52,53,54,55,56,57, and take n0 constant in the metal, zero outside (hard-wall condition).

We first analyze the linear optical response (j = 1) from Eqs. (3) and (4) (with \({{\bf{S}}}_{{\omega }_{j}}^{{\rm{NL}}}=0\)). We consider a semi-infinite 30-nm-thick slab of heavily doped InGaAs with carrier density n0 under a plane wave with oblique incidence at 60°. The material follows a Drude-like response with ε∞ = 12, γ = 8.9 ps−1, and me = 0.041m0 (m0 is the electron mass)32,37. The screened bulk plasma wavelength is \({\lambda }_{{\rm {p}}}=2\pi c\,\sqrt{{m}_{{ {e}}}{\varepsilon }_{0}{\varepsilon }_{\infty }/({n}_{0}{e}^{2})}\). Figure 1b shows the slab absorbance for two doping levels: n0 = 12 × 1018 cm−3 (red) and n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3 (blue), calculated using a finite-element solver (we use comsol multiphysics, see the “Methods” section)55,56,58. The bulk plasmon or epsilon-near-zero (ENZ) resonances for both systems are at λ0 = 5.85 μm and λ0 = 8 μm, respectively, with additional higher-order resonances satisfying ε(ω, k) = 0 under HT. Only odd-order LBPs carry a net dipole moment and thus couple to plane-wave incidence37. At λ0 = 8 μm, the slab with n0 = 12 × 1018 cm−3 (with screened plasma wavelength at 7.33 μm) supports an SPP, with LBP resonances occurring at lower wavelengths, whereas for a doping level n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3 (with screened plasma wavelength at 10.37 μm) λ0 = 8 μm exactly matches the first (m = 1) LBP mode.

We can then find out the linear modes supported by the structure shown in Fig. 1a by solving the corresponding eigenvalue problem. From Eq. (4), and using the curl of curl identity, ∇×(∇ × Ej) = ∇(∇ ⋅ Ej)−∇2Ej, together with ∇⋅Pj = −ε0∇⋅Ej and rearranging terms, we have:

where \({\chi }_{j}=\varepsilon ({\omega }_{j})-1=-\frac{{\omega }_{{\rm {p}}}^{2}}{{\omega }_{j}^{2}+i\gamma {\omega }_{j}}\). Then, substituting Eq. (5) into Eq. (3), using again the curl of curl identity, and particularizing for j = 1 yields the eigenvalue problem for the fundamental mode, where the eigenvalue is the wavevector k1:

where we have rewritten \({k}_{1}^{2}=\varepsilon {\omega }^{2}/{c}^{2}\) and set \({{\bf{S}}}_{{\omega }_{1}}^{{\rm{NL}}}\approx 0\) since we are calculating the linear response. Letting the mode propagate along \(z,\,{{\bf{E}}}_{1}({\bf{r}})={A}_{1}\,{\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{1}(x,y)\,{{\rm {e}}}^{i{\kappa }_{1}z}\). We solve Eq. (6) numerically for arbitrary cross-sections using a finite-element eigenmode solver (we use comsol multiphysics, see the “Methods” section)55,56,58.

Figure 1 c and d show the electric-field amplitudes ∣E∣ of the TM mode for both doping levels, n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3 (Fig. 1c) and n0 = 12 × 1018 cm−3 (Fig. 1d) at z = 0. In each case, the mode is mostly confined in the undoped InGaAs and extends into the heavily doped layer. The field profiles in Fig. 1e reveal a stark difference between both cases: the LBP mode displays a significantly larger field amplitude in the bulk of doped layer, while the SPP mode’s field amplitude is comparatively smaller and confined in the vicinity of the surface. More importantly, the former mode has the maximum field amplitude inside the heavily doped InGaAs whereas the latter repels the field outside of the InGaAs, where the FE nonlinearity comes from. A closer view (Fig. 1f) underscores this difference and indicates the respective propagation lengths, calculated from the eigenmodes’ wavevectors k1 as Lp = 1/Im(k1). The LBP mode has Lp = 141 μm, enabled by strong interaction between the guided mode and the doped layer, whereas the SPP mode shows a longer propagation (Lp = 3690 μm) due to weaker overlap with the heavily doped semiconductor, that is, the most damped region. Overall, the hybrid LBP mode provides stronger field confinement and enhanced FE interactions, leveraging both the low-loss waveguide mode and the strong contribution of the heavily doped InGaAs.

Free-electron Kerr nonlinearity in hybrid heavily doped semiconductor waveguides

In fact, the LBP is a charge density wave in the bulk (fields shown as Fig. 1c) that overlaps with the physical dimension of the heavily doped InGaAs, guaranteeing enough active interaction volume and strong nonlinearity37. This hybrid LBP-guided mode is thus an ideal platform for generating strong FE Kerr at low power, which we now investigate. To calculate the nonlinear modulation due to the FE-driven Kerr effect, we solve the nonlinear problem self-consistently to allow the field to be self-modulated by its own intensity. In particular, we solve the extension of Eq. (6) to Kerr nonlinearity by accounting for third-order (i.e., direct effects) processes, as indicated by \({{\bf{S}}}_{{\omega }_{1}}^{(3)}\), neglecting cascaded effects for simplicity:

where \({\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{1}^{{\prime} }\) and \({k}_{1}^{{\prime} 2}\) are the self-consistent solutions for the transverse electric field and wavevector under FE Kerr nonlinearity, respectively. \({({{\bf{S}}}_{{\omega }_{1}}^{(3)})}^{{\prime} }\) is the self-consistent FE Kerr source, which is given by:

with \({{\bf{P}}}_{1}^{{\prime} }\) denoting the self-consistent solution of the polarization. The “*" on the variables denotes the complex conjugate. Eq. (8) contains terms proportional to \({n}_{0}^{-2}\), which boost nonlinearities at relatively low doping levels. On the other hand, the Kerr nonlinearity from the dielectric can be considered with a self-consistent polarization \({{\bf{P}}}_{{\rm{d}}}^{{\rm{NL}}}=3{\varepsilon }_{0}{\chi }^{(3)}| {\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{1}^{{\prime} }{| }^{2}{\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{1}^{{\prime} }\) with the susceptibility of InGaAs given by \({\chi }_{{\rm{InGaAs}}}^{(3)}=1.6\,\cdot \,1{0}^{-18}\) m2/V2, while that of InP is \({\chi }_{{\rm{InP}}}^{(3)}=1{0}^{-18}\) m2/V2 2, with ε0 the permittivity of free space.

Let us now consider Eqs. (7) and (8). In nonlinear optics, the divergence term in Eq. (7) is generally neglected and a solution can be easily obtained in the slowly varying envelope approximation, through the definition of overlap integrals evaluated in the waveguide cross-section59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66. In the case of metal nonlinearities, and in particular of hydrodynamic nonlinearities, neglecting the divergence will strongly affect the results, since the larger nonlinear contributions arise at the metal surface, where the divergence is non-zero. On the other hand, fully solving Eqs. (7) and (8) in a three-dimensional numerical set-up is challenging, due to the large scale mismatch between the surface effects and the overall mode propagation. Assuming, without loss of generality, that the modes propagate along the z direction, we can solve for the mode profile at the waveguide cross-section. By writing \(\nabla ={\nabla }_{\perp }+i{\kappa }_{1}\hat{{\bf{z}}}\), the FE Kerr nonlinear source in Eq. (8), it can be rewritten as

We develop a specific nonlinear eigenmode solver to find out the solutions of Eqs. (7) and (9) and calculate the refractive index change Δneff in the waveguide due to the FE Kerr effect. In a standard linear mode analysis, one assumes a refractive index profile that is independent of the optical field intensity and solves for the corresponding electromagnetic eigenmode. However, in the nonlinear eigenmode problem given by Eqs. (7) and (9), the Kerr effect induces a change in the refractive index that depends on the local field intensity. This creates a feedback loop: the mode profile itself modifies the refractive index distribution, which then further modifies the mode. One must then solve Maxwell’s equations self-consistently with an intensity-dependent refractive index67,68. Commercially available FEM nonlinear eigenmode solvers can struggle with nonlinearities and, more importantly, with the added complexity of non-localities introduced by functionals like the TF. In our method, we introduce a nonlinear scaling coefficient \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}^{2}\) in the nonlinear source terms \({\tilde{{\bf{S}}}}_{{\omega }_{1}}^{(3)}\), given by Eq. (9), and \({{\bf{P}}}_{{\rm{d}}}^{{\rm{NL}}}\). We can thus rewrite the eigenvalue problem as

starting from the solution to Eq. (10) with \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}=0\)—i.e., the linear eigenmode—as initial guess for the field amplitude \({\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{1}\) and effective index neff = k1/k0. Then, we incrementally adjust \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}^{2}\) in small steps, solving Eq. (10) at each step. Each iteration effectively linearizes the problem, and we can solve it self-consistently until the effective mode index \({n}_{{\rm{eff}}}^{{\prime} }={k}_{1}^{{\prime} }/{k}_{0}\) converges (see the “Methods” section for more technical details on the nonlinear eigenmode solver). Once convergence is reached, \({\rm{\Delta }}{n}_{{\rm{eff}}}={n}_{{\rm{eff}}}^{{\prime} }-{n}_{{\rm{eff}}}\) and the total input power can be calculated as \(P={{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}^{2}\,\cdot \,{P}_{0},\) where \({P}_{0}=\int{\bf{S}}\,\cdot \,\hat{{\bf{z}}}\,{\rm {d}}z\) represents the integral of the Poynting vector z component over the waveguide cross-section. Because each iteration updates the material response, these converged solutions form the nonlinear mode. Our nonlinear eigenmode analysis is validated against existing experimental data (see Supplementary Fig. 2 in Supplementary Note 2) and, to facilitate reproducibility, its beta version is publicly available on69.

The field distributions of the resulting linear and nonlinear eigenmodes for n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3, λ0 = 8 μm, and different powers P are shown in Fig. 2. Fig. 2a depicts the linear eigenmode at P = 0, consistent with the distribution shown in Fig. 1c. In turn, Fig. 2b illustrates the nonlinear eigenmode at \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}=1.5\,\cdot \,1{0}^{5}\), corresponding to an input power of P = 0.144 W. The arrow lengths indicate that the LBP’s electric field amplitude increases with increasing power while the core electric field amplitude decreases. Figure 2c displays the field distribution along a line profile taken through the center of the structure, clearly showing the LBP electric field amplitude in the heavily doped InGaAs layer for the nonlinear mode. This is more clearly seen in the zoomed in field profile shown in Fig. 2d, where a pronounced increase in the electric field is observed in the heavily doped InGaAs layer as the input power increases. In turn, the field distribution of the guided mode in the undoped InGaAs layer shows a decrease of the field amplitude, which is associated to a decrease of the effective mode index in this region. In fact, the overall refractive index change of the nonlinear mode is Δneff = −0.0011, that is, the nonlinear response of heavily doped InGaAs causes the refractive index to decrease with increasing power. This behavior is often referred to as self-defocusing, and can stem from various mechanisms, including negative refractive indices in left-handed metamaterials70, filamentation and plasma dynamics71, and excitonic interactions in quantum dots72, allowing for effects such as the formation of optical vortex solitons73 or the design of lenses70. Here, it is attributed to free-carrier effects in heavily doped semiconductors.

a Simulated linear TM eigenmode electric field amplitude distribution (not normalized) for n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3 (LBP mode) at λ0 = 8 μm and a power P = 0 W. The white dashed lines mark the waveguide boundaries and the gray shadowing indicates the HfO2 and Au layers on top of the waveguide. b Simulated nonlinear TM eigenmode electric field amplitude distribution (not normalized) for n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3 (LBP mode) at λ0 = 8 μm and a power P = 0.144 W. The white dashed lines mark the waveguide boundaries and the gray shadowing indicates the HfO2 and Au layers on top of the waveguide. c Linear and nonlinear eigenmode electric field amplitude profiles (not normalized) along the center of the waveguide. d Zoomed-in views of the linear and nonlinear eigenmode electric field amplitude profiles (not normalized) in the heavily doped InGaAs layer. The mode at P = 0.144 W shows an appreciable field amplitude increase. e Zoomed-in views of the linear and nonlinear eigenmode electric field amplitude profiles (not normalized) in the undoped InGaAs region. The mode at P = 0.144 W shows an appreciable field decrease, associated with a lower mode effective refractive index.

By varying \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}\) one can get a Δneff curve as a function of P. The resulting values form a linear dependence Δneff = n2(P)P, where n2 is the nonlinear refractive index—a parameter that quantifies the Kerr nonlinearity of the system. We note that n2 should not be confused with the second-order perturbed carrier density, i.e., j = 2 in \(n={n}_{0}+{\sum }_{j}{n}_{j}{{\rm {e}}}^{-i{\omega }_{j}t}\). In the case of a plane wave propagating through a bulk nonlinear material, the nonlinear effect initially scales linearly with P. The electric field intensity eventually reaches its maximum permissible value before material damage occurs, marking the limit of the nonlinear index change74. Additionally, our hydrodynamic formalism is derived under the perturbative condition n1 ≪ n0. To remain within this regime, we estimate the power at which n1 reaches 20% of n0 (see Supplementary Fig. 3 in Supplementary Note 3).

The resulting line fits to our calculated Δneff(P) points are shown in Fig. 3a, comparing the contributions from purely hydrodynamic effects (\({\tilde{{\bf{S}}}}_{{\omega }_{1}}^{(3)}\), solid line) with the combined hydrodynamic and lattice nonlinearity (\({\tilde{{\bf{S}}}}_{{\omega }_{1}}^{(3)}+{{\bf{P}}}_{{\rm{d}}}^{{\rm{NL}}}\), dashed line) for different doping levels n0. For n0 = 12 × 1018 cm−3 (red dashed line), which corresponds to the SPP mode in Fig. 1d, the modulation due to hydrodynamic contributions remains minimal due to the weak field amplitude inside the active volume (doped InGaAs bulk), as shown in Fig. 1e. The nonlinear susceptibility χ(3) contribution remains low in this regime. Conversely, the LBP mode exhibits strong nonlinear modulation, with Δneff reaching values as high as −0.04 for P = 6.5 W at an electron concentration of n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3 (blue dashed line). This is due to the larger nonlinear active volume and field amplitude of the LBP mode, and corresponds to a relative change of 1.3%. As anticipated in the description of Fig. 2, the nonlinear response of heavily doped InGaAs causes the refractive index to decrease with increasing power, i.e. the slope of Δneff versus P is negative and thus the Kerr coefficient n2 is negative. Incorporating materials with negative n2 into waveguide structures can enhance performance metrics such as bandwidth, power handling, and signal fidelity. Additionally, electronic contributions to n2 provide a fast, instantaneous negative nonlinear response, which is highly advantageous for ultrafast optical applications. On the other hand, the presence of a positive χ(3) component introduces a slight upward bending of the line, but it is orders of magnitude weaker than the hydrodynamic contribution. Finally, moving away from the LBP resonance at λ0 = 8 μm, the hydrodynamic Kerr nonlinearity is much weaker, as shown by calculations at n0 = 6.5 and 7 × 1018 cm−3. For n0 = 5 × 1018 cm−3, the values decrease and are hidden behind those for n0 = 12 × 1018 cm−3 in the plot. This suggests that the large nonlinearity at n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3 is not solely due to the \({n}_{0}^{-2}\) dependence of the FE Kerr effect but is mainly caused by the resonance of the LBP.

a Comparison of refractive index modulation for different carrier concentrations from n0 = 6 × 1018 (blue) to n0 = 12 × 1018 cm−3 (red). Solid lines correspond to self-consistent hydrodynamic contributions (\({\tilde{{\bf{S}}}}_{{\omega }_{1}}^{(3)}\)), while dashed lines include lattice nonlinear contributions (\({\tilde{{\bf{S}}}}_{{\omega }_{1}}^{(3)}+{{\bf{P}}}_{{\rm{d}}}^{{\rm{NL}}}\)). b Effect of viscoelastic damping γVE on the refractive index modulation. As γVE increases from 0 to 10γ, the field amplitude is reduced, increasing the nonlinear propagation length Lp (color scale). The top panel shows the simulated electric field amplitude distribution ∣E∣ (not normalized) in the heavily doped InGaAs layer as a function of nonlinear damping. c Impact of nonlinear damping γNL. The damping parameter γNL is varied relative to χ(3) from 0 to 104.

We now study the robustness of the Δneff driven by the LBP mode under more realistic conditions. It has been reported that materials like CdO, ITO and InAsSb44, particularly near their ENZ frequencies, often exhibit viscosity-driven nonlocal effects in their optical response43. This is because strong electron-electron scattering induces shear viscosity in the electron fluid, leading to effects such as thickness-dependent dissipation observed in thin structures75. The nonlocal damping can also be interpreted as an effective way to account for single particle excitations76. To account for this effect, we introduce a phenomenological nonlocal viscoelastic damping coefficient γVE in \(\beta =\sqrt{\frac{3}{5}-i\frac{{\gamma }_{{\rm{VE}}}}{\omega }\frac{4}{15}}{v}_{F}\), which accounts for both dispersive and dissipative contributions43. Figure 3b depicts the impact of viscoelastic damping on the nonlinear modulation for increasing values of γVE relative to the Drude damping rate γ of heavily doped InGaAs (color gradient) ranging from 0 to 10γ. Here we fix a doping level n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3, which corresponds to the maximum FE Kerr nonlinearity in Fig. 3a. As γVE increases, the field amplitude in the heavily doped InGaAs layer diminishes, resulting in a reduced nonlinear index shift and an increase in the nonlinear propagation length Lp, from Lp = 141 μm for γVE = 0 up to Lp = 170 μm γVE = 10γ (color bar). Despite this reduction, the overall nonlinearity remains robust. Another source of damping can arise in our structure, since FE nonlinearities alter the carrier distribution and induced polarization, making absorption depend nonlinearly on the electric field. This effect can be modeled by an additional phenomenological nonlinear damping term \(i{\gamma }_{{\rm{NL}}}| {\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{1}{| }^{2}{\tilde{{\bf{E}}}}_{1}\), giving rise to a change in the refractive index. Additionally, high optical powers can also induce a red shift of the LBP resonance due to local heating of electrons in the conduction band (hot-electron effects). However, we neglect such a shift in our study and only account for the potential induced loss. Additional nonlinear damping may arise from Auger recombination (significant at high carrier densities) or phonon-assisted scattering, whereas two-photon absorption remains weak in mid-IR InGaAs. Figure 3c shows the influence of γNL relative to χ(3), ranging from 0 to 104χ(3). Again, we fix a doping level n0 = 6 ⋅ 1018 cm−3, i.e., the doping yielding the maximum FE Kerr nonlinearity in Fig. 3a. We observe that the change in the refractive index decreases for increasing values of γNL. In addition, since χ(3) is considerably smaller than the hydrodynamic contribution, the nonlinear damping has a small impact on the refractive index modulation, confirming the resilience of the optical nonlinearity in this system.

From the slope of the Δneff(P) lines in Fig. 3, one can extract the nonlinear refractive index as n2 = Δneff(P)V, where V is the mode volume. The mode volume is defined as \(V=\frac{\int{\bf{S}}\,\cdot \,\hat{{\bf{z}}}\,{\rm {d}}A}{\max (\varepsilon | {\bf{E}}{| }^{2})}\), where S = E × H* is the Poynting vector. For a carrier concentration of n0 = 6 × 1018 cm−3 and a wavelength of λ0 = 8 μm (corresponding to the LBP mode in Fig. 1c), the mode volume is V = 0.47 μm2. This exceptionally small mode volume arises from the strong field confinement in the heavily doped InGaAs layer (Fig. 1e). From this, we obtain n2 = − 8.93 ⋅ 10−16 m2 W−1, notably higher in absolute value than previously reported near- and mid-IR Kerr nonlinear refractive indices (see Table 1). Our significantly higher value at 8 μm arises from exceptionally strong FE nonlinearities, which stem from the FE polarizability scaling as \({n}_{0}^{-2}\)31. Since \({\omega }_{{\rm {p}}}\propto \sqrt{{n}_{0}}\), reducing n0 shifts the response toward longer wavelengths. Interestingly, the requirement for a lower n0 also has the added benefit of reducing losses. All this is complemented by a large interaction volume due to the LBP that induces a pronounced field enhancement in the bulk of the heavily doped InGaAs layer37. We note that, apart from the platforms reported in Table 1, quantum wells in III–V heterostructures have also been employed to engineer giant nonlinearities29,30,77, although Kerr nonlinearities have been less explored in those platforms.

Finally, we compute the waveguide’s Kerr nonlinear coefficient γwg, which quantifies the waveguide’s nonlinear response to an optical field and is given by24,78

where \({k}_{1}^{{\prime} }\) is given by Eq. (7), n(x, y) is the refractive index profile, and E and H are the electric and magnetic fields of the LBP mode. The integral in the numerator captures the spatial overlap of the nonlinear interaction with the mode intensity, whereas the denominator normalizes by the mode power. Consequently, we find γwg ≈ 4 × 107 W−1 km−1. For comparison, silicon and AlGaAs waveguides at 1.55 μm typically exhibit nonlinear parameters of 103–105 W−1 km−1, while silicon nitride and lithium niobate show more moderate values of 100–102 W−1 km−1 (see Table 2). On the other hand, ITO waveguides can reach values of up to 107 by leveraging ENZ resonances27,79. As discussed above, the exceptionally large nonlinear refractive index of our mid-IR waveguides, stemming from the synergy between high nonlinearity and tight mode confinement, drives γwg far beyond near-IR benchmarks, positioning LBP-based plasmonic waveguides as a promising platform for nonlinear integrated photonic circuits and underscoring the potential of FE nonlinearities in heavily doped semiconductors for mid-IR integrated photonic platforms. As mentioned above, the problem of free carrier losses, typically increasing as λ−2, becoming more severe at mid-IR wavelengths, can be mitigated with hybrid designs featuring intrinsic cores and evanescently coupled doped layers, like the one presented in this work.

Finally, we calculate the FOM of the conversion efficiency η as a function of the length L, driven by a power P, which can be calculated as \(\eta \approx {e}^{-\alpha L}{\left({\gamma }_{{\rm{wg}}}P{L}_{{\rm{eff}}}\right)}^{2}\)24,25, where the attenuation and nonlinear coefficients, α and γwg respectively, are calculated from the electromagnetic field using mode analysis. α is given by 1/Lp, where Lp for the LBP is 140 μm, and γwg is given by Eq. (11). The effective length Leff is defined as \({L}_{{\rm{eff}}}=\frac{1-{e}^{-\alpha L}}{\alpha }\), in agreement with the one reported for lossy waveguides24. The conversion efficiency η takes into account the balance between nonlinearity and losses. For instance, silicon and silicon nitride waveguides typically yield values of η ≈ 10−2 to 1. However, silicon tends to attain higher η at short lengths due to its strong nonlinearity, but losses quickly reduce efficiency for longer waveguides. Silicon nitride waveguides, in turn, with lower γwg, compensate with much lower loss and longer effective interaction lengths, allowing significant nonlinear effects over longer distances. On the other hand, metal–ITO–metal slot waveguides, with a very high γwg ≈ 107 W−1 km−1 yield relatively low η values due to its large losses, which limit propagation length to a few microns, as well as phase accumulation27,79. For our system, the maximum η ≈ 200 is attained at a waveguide length L ≈ 160 μm, i.e., at a very long distance, for a power P = 6.5 W (see Supplementary Fig. 4 in Supplementary Note 4). Values of η around 100–200 are comparable to or exceed state-of-the-art values at telecom wavelengths, but at mid-IR, where losses tend to be higher, and also exceed Kerr conversion efficiencies reported for plasmonic waveguides by several orders of magnitude24,25. This suggests efficient nonlinear interactions by exploiting the low-loss character of our all-semiconductor waveguides, together with strong FE nonlinearities from heavily doped InGaAs.

FE-Kerr-induced transmittance modulation in a hybrid heavily doped semiconductor Mach–Zehnder interferometer

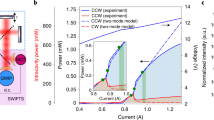

Finally, we investigate the possibility of leveraging the nonlinear modulation of the refractive index discussed in Fig. 3 to induce an intensity-dependance modulation of the transmittance spectrum. To do so, we employ a Mach–Zehnder interferometer (MZI), sketched in Fig. 4a. The input light (green arrow) enters through port 1 into the waveguide core, made of undoped InGaAs (green) cladded by InP (beige), with a mode index neff = 3.11 (see Supplementary Fig. 1 in Supplementary Note 1) and propagation losses γ/20, where γ corresponds to the Drude damping for heavily doped InGaAs, leading to a propagation length Lp = 32 mm. The input light is then divided at a 200 μm-long splitter, with a curvature radius R = 400 μm optimized to minimize reflection and scattering losses. The two waveguide arms guide the light along different paths: the right arm contains a 30-nm-thick layer of heavily doped InGaAs on top (gray), inducing a refractive index change dependent on the input intensity based on the hydrodynamic Kerr plus the third-order susceptibility χ(3), while the left arm remains undoped and undergoes only Kerr effects characterized by the third-order susceptibility χ(3). Therefore, the key contribution to the phase shift difference comes from the hydrodynamic nonlinearity in the right arm. Traversing a 175 μm-long recombination section, the two arms interfere at the output ports 2 (blue) and 3 (red), with the phase accumulation in the left arm given by ϕl = k0neffL, where L is the length of the nonlinear interaction section, set to 150 μm. For the arm with the heavily doped InGaAs, the phase accumulation depends on the input intensity as \({\phi }_{{\rm{r}}}=\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{0}^{L}{k}_{0}{{\Delta }}{n}_{{\rm{eff}}}(z)\,{ {d}}z=\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{0}^{L}{k}_{0}{n}_{2}P(z)\,{ {d}}z\), where n2 = −0.007 W−1 is the nonlinear refractive index coefficient extracted from the slope of the blue curve in Fig. 3a, and P(z) is the power profile along the waveguide. Since the electric field intensity \({E}_{0}^{2}\) decays due to losses, the power profile is modeled as \(P(z)={P}_{0}\exp (-\gamma z)\), where P0 is the input power and γ = Im(neff)k0 is the attenuation constant of the mode, with Im(neff) = 0.009. Substituting this into the integral yields \({\phi }_{{\rm{r}}}=\frac{{k}_{0}{n}_{2}{P}_{0}}{\gamma }\left[1-\exp (-\gamma L)\right]\). The relative phase difference between the two arms is Δϕ = ϕr−ϕl, which dictates the interference pattern at the output. Fig. 4b shows the power-dependent transmittance at the output ports: the blue curve ∣T21∣ represents the transmittance through port 2, while the red curve ∣T31∣ represents the transmittance through port 3. At low input powers, nonlinearities are low, and the transmittance is dominated by the linear arm, with most light exiting through port 2, ∣T21∣ ≈ 60%. As input power increases, the nonlinear phase shift in the doped arm grows, shifting the interference toward destructive interference at port 2 and constructive interference at port 3. At around 3 W input power, the output switches entirely, with most light starting to exit through port 3, up to ∣T31∣ ≈ 60%. The modulation range from ≈20% to ≈60% demonstrates the significant impact of the hydrodynamic Kerr effect on the transmittance. Importantly, this transmittance could be potentially tuned on-demand by leveraging the reconfigurability of the FE Kerr effect through the application of a bias voltage35.

a 3D schematic of the Mach–Zehnder interferometer (MZI) composed of undoped InGaAs (green) cladded by InP (beige). Input light enters through port 1 (green arrow) and is split into two arms at the splitter (200 μm length). The right arm includes a 30-nm-thick heavily doped InGaAs layer (dark gray) to induce an intensity-dependent refractive index change, while the left arm does not. The nonlinear interaction region (150 μm) in the doped arm exploits hydrodynamic and Kerr nonlinearities to produce a phase shift, while the left arm undergoes only dielectric Kerr effects. The two arms interfere at the output in a 175 μm-long recombination section, determining the transmittance at output ports 2 (blue) and 3 (red), given by T21 and T31, respectively. b Power-dependent output transmittance, showing the modulation at ports 2 and 3 (T21 in blue and T31 in red, respectively) as a function of the input power P.

Discussion

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that FEs can induce exceptionally strong Kerr nonlinearities in all-semiconductor hybrid waveguides. Building on this, we can design waveguides that harness LBPs, nonlocal resonances, that achieve ultrahigh nonlinear coefficients. Leveraging this high nonlinearity, we have shown an all-optical intensity-dependent modulation of the transmittance in a MZI. These results highlight the potential of FE nonlinearities in heavily doped semiconductors for integrated nonlinear photonics, offering a new route to realize high-speed, low-power, and ultra-compact optical devices for next-generation data processing. Our proposed waveguides can be fabricated using well-established techniques such as metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), electron beam lithography, and reactive ion etching32,80. These methods enable precise local doping and alloy-composition control, high crystal quality and excellent fabrication precision at mid-IR wavelengths. Importantly, MOCVD is compatible with III–V foundry processes, which is crucial for the scalability of our design. However, a common challenge to be overcome in all mid-IR photonic integrated circuits is the development of mid-IR transparent passivation layers that will help make the circuits more stable, long-lived and reproducible.

Methods

Finite element method simulations

We employed the finite-element method (specifically, we used comsol multiphysics) to solve the system of differential hydrodynamic-Maxwell equations in the mode analysis study (eigenfrequency solver) in Eqs. (3) and (4). The coupled equations were customized and implemented using divergence elements and appropriate weak-form expressions. In all cases, mesh convergence was ensured by suitably adjusting the element size. The applied boundary conditions were scattering boundaries and perfectly matched layers around the waveguide to minimize reflections. For hydrodynamic calculations, we set the normal polarization component to zero, \({P}_{n}^{-}={P}_{n}^{+}=0\) (Dirichlet boundary condition) as the required additional boundary condition5,52,53,54,55,56,57, and take n0 constant in the metal, zero outside (hard-wall condition).

The nonlinear and nonlocal simulations presented in Figs. 1–3 were carried out in a 2D transverse cross-section of the waveguide. The simulation process involved three steps: one for linear eigenmode analysis and two for iterative nonlinear eigenmode analysis (see further details about the nonlinear eigenmode analysis in the section below).

For the Mach–Zehnder interferometer simulations, we optimized the splitter’s curvature radius and length to minimize scattering losses from waveguide boundaries in a 3D geometry, also using the finite-element method (we employ comsol multiphysics). Nonlinearity was manually incorporated into a linear model by modifying the material permittivities to support the effective mode refractive index \({n}_{{\rm{eff}}}^{{\prime} }\) for each power P according to the relationship \({n}_{{\rm{eff}}}^{{\prime} }={n}_{{\rm{eff}}}+{\rm{\Delta }}{n}_{{\rm{eff}}}(P)\) from the calculations shown in Fig. 3.

To facilitate reproducibility, our finite element method models are publicly available on69.

Nonlinear eigenmode analysis

The iterative procedure for solving the nonlinear eigenmodes based on Eq. (10) is carried out as follows. We implement the process in comsol multiphysics by setting up two eigenmode solvers with an initial value of \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}=0\), corresponding to the purely linear regime. The relative tolerance of the solver is set to ϵrel = 10−9. From there, we incrementally increase \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}\) in small steps. At each step, both solvers are iteratively run by setting the other one as the initial condition until they converge—that is, until they identify the same mode within a specified tolerance. Such a tolerance, the maximum difference of the effective mode indices of the two modes that we allow, is different from the one above and is set to \({\epsilon }_{{\rm{rel}}}^{* }=1{0}^{-4}\). The parameter \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}\) effectively linearizes the nonlinear problem by gradually activating the hydrodynamic free-electron nonlinear sources. Once convergence is achieved for a given \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}\), we increase it again and repeat the process. Each value of \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}\) corresponds to a certain power level, as described in the main text. For sufficiently large \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}\), convergence can no longer be achieved, and the perturbative assumption may also become invalid (see Supplementary Fig. 3 in Supplementary Note 3).

The nonlinear eigenmode solver is validated against experimental data in Supplementary Fig. 2 in Supplementary Note 2).

To facilitate reproducibility, the beta version of the nonlinear eigenmode analysis is publicly available in ref. 69.

Data availability

The data supporting our study is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

To facilitate reproducibility, the beta version of the comsol multiphysics files used for our nonlinear eigenmode analysis are publicly available on [https://zenodo.org/records/15264605 (ref. 67)].

References

Suhara, T. & Fujimura, M.Waveguide Nonlinear-Optic Devices, vol.1 of Springer Series in Photonics 1st edn (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003).

Boyd, R. W., Gaeta, A. L. & Giese, E. Nonlinear optics. In: Springer Handbook of Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics (Springer, 2008).

Smith, D. R., Pendry, J. B. & Wiltshire, M. C. Metamaterials and negative refractive index. Science 305, 788–792 (2004).

Galiffi, E. et al. Photonics of time-varying media. Adv. Photonics 4, 014002–014002 (2022).

Krasavin, A. V., Ginzburg, P. & Zayats, A. V. Free-electron optical nonlinearities in plasmonic nanostructures: a review of the hydrodynamic description. Laser Photonics Rev. 12, 1700082 (2018).

Almeida, V. R. & Lipson, M. Optical bistability on a silicon chip. Opt. Lett. 29, 2387–2389 (2004).

Gibbs, H. et al. Room-temperature excitonic optical bistability in a GaAs–GaAlAs superlattice étalon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 41, 221–222 (1982).

Un, I.-W., Sarkar, S. & Sivan, Y. Electronic-based model of the optical nonlinearity of low-electron-density drude materials. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 044043 (2023).

Cox, J. D. & Javier García de Abajo, F. Electrically tunable nonlinear plasmonics in graphene nanoislands. Nat. Commun. 5, 5725 (2014).

Christensen, T., Yan, W., Jauho, A.-P., Wubs, M. & Mortensen, N. A. Kerr nonlinearity and plasmonic bistability in graphene nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. B 92, 121407 (2015).

Cox, J. D., Silveiro, I. & García de Abajo, F. J. Quantum effects in the nonlinear response of graphene plasmons. ACS Nano 10, 1995–2003 (2016).

Ryabov, D., Pashina, O., Zograf, G., Makarov, S. & Petrov, M. Nonlinear optical heating of all-dielectric super-cavity: efficient light-to-heat conversion through giant thermorefractive bistability. Nanophotonics 11, 3981–3991 (2022).

Niu, J. et al. All-optical nonlinear neuron based on metallic quantum wells. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2300223 (2023).

Toulouse, J. Optical nonlinearities in fibers: review, recent examples, and systems applications. J. Lightwave Technol. 23, 3625–3641 (2005).

Petropoulos, P. et al. Highly nonlinear and anomalously dispersive lead silicate glass holey fibers. Opt. Express 11, 3568–3573 (2003).

Koos, C., Jacome, L., Poulton, C., Leuthold, J. & Freude, W. Nonlinear silicon-on-insulator waveguides for all-optical signal processing. Opt. Express 15, 5976–5990 (2007).

Leuthold, J., Koos, C. & Freude, W. Nonlinear silicon photonics. Nat. Photonics 4, 535–544 (2010).

Moss, D. J., Morandotti, R., Gaeta, A. L. & Lipson, M. New CMOS-compatible platforms in nonlinear optics. Nat. Photonics 7, 597–607 (2013).

Lin, Q., Painter, O. J. & Agrawal, G. P. Nonlinear optical phenomena in silicon waveguides: modeling and applications. Opt. Express 15, 16604–16644 (2007).

Koos, C. et al. All-optical high-speed signal processing with silicon-organic hybrid slot waveguides. Nat. Photonics 3, 216–219 (2009).

Ebbesen, T. W., Genet, C. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. Surface-plasmon circuitry. Phys. Today 61, 44–50 (2008).

Kauranen, M. & Zayats, A. V. Nonlinear plasmonics. Nat. Photonics 6, 737–748 (2012).

Salgueiro, J. R. & Kivshar, Y. S. Nonlinear couplers with tapered plasmonic waveguides. Opt. Express 20, 9403–9408 (2012).

Li, G., de Sterke, C. M. & Palomba, S. Figure of merit for Kerr nonlinear plasmonic waveguides. Laser Photonics Rev. 10, 639–646 (2016).

Li, G., de Sterke, C. M. & Palomba, S. Fundamental limitations to the ultimate Kerr nonlinear performance of plasmonic waveguides. ACS Photonics 5, 1034–1040 (2018).

Hossain, M. M., Turner, M. D. & Gu, M. Ultrahigh nonlinear nanoshell plasmonic waveguide with total energy confinement. Opt. Express 19, 23800–23808 (2011).

Rojas Yanez, L., Hu, H., Cirací, C. & Palomba, S. Plasmonic slot waveguides: a quantum leap in nonlinear nanophotonics. Front. Nanotechnol. 7, 1536462 (2025).

Diaz, F. J. et al. Sensitive method for measuring third order nonlinearities in compact dielectric and hybrid plasmonic waveguides. Opt. Express 24, 545–554 (2016).

Lee, J. et al. Giant nonlinear response from plasmonic metasurfaces coupled to intersubband transitions. Nature 511, 65–69 (2014).

Yu, J. et al. Electrically tunable nonlinear polaritonic metasurface. Nat. Photonics 16, 72–78 (2022).

De Luca, F., Ortolani, M. & Ciracì, C. Free electron nonlinearities in heavily doped semiconductors plasmonics. Phys. Rev. B 103, 115305 (2021).

Rossetti, A. et al. Control and enhancement of optical nonlinearities in plasmonic semiconductor nanostructures. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 192 (2025).

De Luca, F., Ortolani, M. & Ciracì, C. Free electron harmonic generation in heavily doped semiconductors: the role of the materials properties. EPJ Appl. Metamaterials 9, 13 (2022).

De Luca, F. & Ciracì, C. Impact of surface charge depletion on the free electron nonlinear response of heavily doped semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 123902 (2022).

Hu, H. et al. Modulating low-power threshold optical bistability by electrically reconfigurable free-electron Kerr nonlinearity. arXiv preprint https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.14082 (2024).

Noor, A. et al. Second-harmonic generation in plasmonic waveguides with nonlocal response and electron spill-out. Phys. Rev. B 106, 045415 (2022).

Hu, H., Álvarez Pérez, G., Otomalo, T. O. & Cirací, C. Low-power threshold optical bistability enabled by hydrodynamic Kerr nonlinearity of free carriers in heavily doped semiconductors. ACS Photonics 11, 4812–4817 (2024).

Ruppin, R. Optical properties of a plasma sphere. Phys. Rev. Lett. 31, 1434 (1973).

Ruppin, R. Extinction properties of thin metallic nanowires. Opt. Commun. 190, 205–209 (2001).

Raza, S., Toscano, G., Jauho, A.-P., Wubs, M. & Mortensen, N. A. Unusual resonances in nanoplasmonic structures due to nonlocal response. Phys. Rev. B 84, 121412 (2011).

Anderegg, M., Feuerbacher, B. & Fitton, B. Optically excited longitudinal plasmons in potassium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 27, 1565 (1971).

Lindau, I. & Nilsson, P. Experimental verification of optically excited longitudinal plasmons. Phys. Scr. 3, 87 (1971).

De Ceglia, D. et al. Viscoelastic optical nonlocality of low-loss epsilon-near-zero nanofilms. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–11 (2018).

Moreau, A. et al. Optical excitation of bulk plasmons in n-doped InAsSb thin films: investigating the second viscosity in electron gas. arXiv preprint https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.01466 (2024).

Christensen, T. et al. Nonlocal response of metallic nanospheres probed by light, electrons, and atoms. ACS Nano 8, 1745–1758 (2014).

Ciracì, C. & Della Sala, F. Quantum hydrodynamic theory for plasmonics: impact of the electron density tail. Phys. Rev. B 93, 205405 (2016).

Toscano, G. et al. Resonance shifts and spill-out effects in self-consistent hydrodynamic nanoplasmonics. Nat. Commun. 6, 7132 (2015).

Silberberg, Y. & Sands, T. Optical properties of metallic quantum wells. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 28, 1663–1669 (1992).

Qian, H., Xiao, Y. & Liu, Z. Giant Kerr response of ultrathin gold films from quantum size effect. Nat. Commun. 7, 13153 (2016).

Cominotti, R. et al. Theory of coherent optical nonlinearities of intersubband transitions in semiconductor quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 107, 115431 (2023).

Grosso, G. & Parravicini, G. P. Solid State Physics (Academic Press, 2013).

Scalora, M. et al. Second-and third-harmonic generation in metal-based structures. Phys. Rev. A 82, 043828 (2010).

Ciracì, C., Poutrina, E., Scalora, M. & Smith, D. R. Second-harmonic generation in metallic nanoparticles: clarification of the role of the surface. Phys. Rev. B 86, 115451 (2012).

Raza, S., Christensen, T., Wubs, M., Bozhevolnyi, S. I. & Mortensen, N. A. Nonlocal response in thin-film waveguides: loss versus nonlocality and breaking of complementarity. Phys. Rev. B 88, 115401 (2013).

Huang, Q., Bao, F. & He, S. Nonlocal effects in a hybrid plasmonic waveguide for nanoscale confinement. Opt. Express 21, 1430–1439 (2013).

Toscano, G. et al. Nonlocal response in plasmonic waveguiding with extreme light confinement. Nanophotonics 2, 161–166 (2013).

Cirací, C., Pendry, J. B. & Smith, D. R. Hydrodynamic model for plasmonics: a macroscopic approach to a microscopic problem. ChemPhysChem 14, 1109–1116 (2013).

Zheng, X., Kupresak, M., Moshchalkov, V. V., Mittra, R. & Vandenbosch, G. A. E. A potential-based formalism for modeling local and hydrodynamic nonlocal responses from plasmonic waveguides. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 67, 3948–3960 (2019).

Ruan, Z., Veronis, G., Vodopyanov, K. L., Fejer, M. M. & Fan, S. Enhancement of optics-to-THz conversion efficiency by metallic slot waveguides. Opt. Express 17, 13502 (2009).

Davoyan, A. R., Shadrivov, I. V., Bozhevolnyi, S. I. & Kivshar, Y. S. Backward and forward modes guided by metal-dielectric-metal plasmonic waveguides. J. Nanophotonics 4, 043509 (2010).

Zhang, J., Cassan, E., Gao, D. & Zhang, X. Highly efficient phase-matched second harmonic generation using an asymmetric plasmonic slot waveguide configuration in hybrid polymer-silicon photonics. Opt. Express 21, 14876 (2013).

Zhang, J., Cassan, E. & Zhang, X. Efficient second harmonic generation from mid-infrared to near-infrared regions in silicon-organic hybrid plasmonic waveguides with small fabrication-error sensitivity and a large bandwidth. Opt. Lett. 38, 2089 (2013).

Wu, T., Sun, Y., Shao, X., Shum, P. P. & Huang, T. Efficient phase-matched third harmonic generation in an asymmetric plasmonic slot waveguide. Opt. Express 22, 18612 (2014).

Sun, Y., Zheng, Z., Cheng, J., Sun, G. & Qiao, G. Highly efficient second harmonic generation in hyperbolic metamaterial slot waveguides with large phase matching tolerance. Opt. Express 23, 6370 (2015).

Huang, T., Tagne, P. M. & Fu, S. Efficient second harmonic generation in internal asymmetric plasmonic slot waveguide. Opt. Express 24, 9706 (2016).

Shi, J. et al. Efficient second harmonic generation in a hybrid plasmonic waveguide by mode interactions. Nano Lett. 19, 3838 (2019).

Liu, Y., Bartal, G., Genov, D. A. & Zhang, X. Subwavelength discrete solitons in nonlinear metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 153901 (2007).

Cohen, O., Schwartz, T., Fleischer, J. W., Segev, M. & Christodoulides, D. N. Multiband vector lattice solitons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 113901 (2003).

Álvarez-Pérez, G. Ultrahigh free-electron Kerr nonlinearity in all-semiconductor waveguides for all-optical nonlinear modulation of mid-infrared light. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15264605 (2025).

Hu, Y., Wen, S., Zhuo, H., You, K. & Fan, D. Focusing properties of Gaussian beams by a slab of Kerr-type left-handed metamaterial. Opt. Express 16, 4774–4784 (2008).

Béjot, P. et al. Transition from plasma-driven to Kerr-driven laser filamentation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 243902 (2011).

Luo, X.-Q., Li, Z.-Z., Li, T.-F., Xiong, W. & You, J. Q. Tunable self-focusing and self-defocusing effects in a triple quantum dot via the tunnel-enhanced cross-kerr nonlinearity. Opt. Express 26, 32585–32598 (2018).

Swartzlander, G. A. & Law, C. T. Optical vortex solitons observed in kerr nonlinear media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2503–2506 (1992).

Li, G., Palomba, S. & de Sterke, C. M. A theory of waveguide design for plasmonic nanolasers. Nanoscale 10, 21434–21440 (2018).

Javani, M. H. & Stockman, M. I. Real and imaginary properties of epsilon-near-zero materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 107404 (2016).

Ciracì, C. Current-dependent potential for nonlocal absorption in quantum hydrodynamic theory. Phys. Rev. B 95, 245434 (2017).

Rosencher, E. et al. Quantum engineering of optical nonlinearities. Science 271, 168–173 (1996).

V, S. A. & Monro, T. M. A full vectorial model for pulse propagation in emerging waveguides with subwavelength structures part I: Kerr nonlinearity. Opt. Express 17, 2298–2318 (2009).

Li, G. H. Y., de Sterke, C. M. & Tuniz, A. Omnidirectional field enhancements drive giant nonlinearities in Epsilon-near-zero waveguides. Opt. Lett. 45, 6514–6517 (2020).

Zhang, K., Böhm, G. & Belkin, M. A. Kerr nonlinearity and group velocity dispersion of InGaAs/InP and GaAsSb/InP waveguides in the mid-infrared. APL Photonics 8, 066107 (2023).

Smektala, F. et al. Chalcogenide glasses with large non-linear refractive indices. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 239, 139–142 (1998).

Reshef, O., De Leon, I., Alam, M. Z. & Boyd, R. W. Nonlinear optical effects in epsilon-near-zero media. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 535–551 (2019).

Alam, M. Z., Schulz, S. A., Upham, J., De Leon, I. & Boyd, R. W. Large optical nonlinearity of nanoantennas coupled to an epsilon-near-zero material. Nat. Photonics 12, 79–83 (2018).

Ji, X. et al. Ultra-low-loss on-chip resonators with sub-milliwatt parametric oscillation threshold. Optica 4, 619–624 (2017).

Hurlbut, W. C., Lee, Y.-S., Vodopyanov, K. L., Kuo, P. S. & Fejer, M. M. Multiphoton absorption and nonlinear refraction of GaAs in the mid-infrared. Opt. Lett. 32, 668–670 (2007).

Chiles, J. et al. Multifunctional integrated photonics in the mid-infrared with suspended algaas on silicon. Optica 6, 1246–1254 (2019).

Ensley, T. R. & Bambha, N. K. Ultrafast nonlinear refraction measurements of infrared transmitting materials in the mid-wave infrared. Opt. Express 27, 37940–37951 (2019).

Yu, Y. et al. A broadband, quasi-continuous, mid-infrared supercontinuum generated in a chalcogenide glass waveguide. Laser Photonics Rev. 8, 792–798 (2014).

Hon, N. K., Soref, R. & Jalali, B. The third-order nonlinear optical coefficients of si, ge, and Si1−xGex in the midwave and longwave infrared. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 011301 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the European Innovation Council through its Horizon Europe program with Grant Agreement No. 101046329. Views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Á.-P. led the work; G.Á.-P. performed the simulations with input from H.H., F.C. and C.C.; C.C. and H.H. developed the nonlinear eigenmode analysis; G.Á.-P. analyzed the data, with input from H.H. and C.C.; G.Á.-P. prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript with input from H.H. and M.O.; C.C. and M.O. conceived the original idea. G.Á.-P., H.H., T.O.O., M.O. and C.C. contributed to the discussion.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Álvarez-Pérez, G., Hu, H., Huang, F. et al. Ultrahigh free-electron Kerr nonlinearity in all-semiconductor waveguides for all-optical nonlinear modulation of mid-infrared light. npj Nanophoton. 2, 33 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-025-00074-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-025-00074-5