Abstract

Digital health technologies (DHTs) and novel artificial intelligence tools have already begun to transform healthcare in many parts of the world. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are on the rise in sub-Saharan Africa, with cardiovascular disease accounting for the largest NCD burden. Digital technologies can accelerate healthcare transformation and improve healthcare delivery in sub-Saharan Africa. This article explores digital technologies in sub-Saharan Africa and potential applications in the field of cardiovascular medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

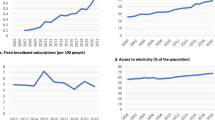

In the last two decades, sub-Saharan Africa has experienced a remarkable digital transformation, largely driven by mobile technology penetration and innovation, with more than 80% of the population having a mobile phone subscription1. The rapid adoption of mobile technology resulted in sub-Saharan Africa effectively skipping the development and use of landline phones and transitioning into the digital age2. This phenomenon is often referred to as leapfrogging. The use of digital mobile and internet technologies has led to significant developments across financial, communication, and public sectors in multiple countries, with evidence of improved labor force participation and reduction in poverty rates, specifically in Nigeria and Tanzania3. Although the use of mobile communication technology has grown tremendously and approximately 84% of individuals in sub-Saharan Africa reside in locations with mobile internet services, internet use remains low, estimated at 22% in 20213. As of 2023, mobile internet penetration was 25%4 and 37% for any internet use (including broadband)5, however, smartphone adoption is projected to reach 88% by 2030, and the use of mobile internet (4G and 5G) to reach 66%4.

Across the continent, many countries face significant healthcare challenges largely attributed to poor access to care, inadequate human resources, limited healthcare financing, ineffective use of available resources, and weak health information management systems6,7,8. Fortunately, health technology is ranked as one of the top five digital business sectors (based on total investment) in sub-Saharan Africa3, a region with an estimated population of 1.1 billion as of 2021 but expected to double by 2025. In addition, 2 of the 3 main categories of digital technology use identified as most promising in West Africa (internet of things and mobile telephones) have a huge potential to influence healthcare9. Studies in Africa have also demonstrated successful use of mobile health (mHealth) technologies in the healthcare domain, such as short message service (SMS) to improve oncology care coordination and education10,11, maternal health services12,13,14, post-surgical care15, and telemedicine for provision of mental health services16.

While communicable diseases have historically been the predominant driver of poor health in sub-Saharan Africa, there has been an increase in the occurrence of non-communicable diseases (NCD), with cardiovascular disease (CVD) accounting for the largest NCD burden. In fact, NCDs are projected to become the leading cause of death by 203017. This shift is mostly due to prevalent cardiovascular risk factors, which include unhealthy diets, air pollution, and low levels of physical activity17. Up to 80% of global CVD-related deaths occurred in developing countries, with more than 1 million deaths reported in sub-Saharan Africa18. In response to the rising incidence and prevalence of CVD in sub-Saharan Africa and the huge unmet need for cardiovascular care19, it is imperative that novel and practical strategies are considered to mitigate disease burden and enhance cardiovascular care. Increased integration of digital tools in African healthcare systems can enable efficient access to patient information, expanded access to healthcare services through remote monitoring and telehealth, enhanced diagnostic capabilities, improved health literacy, and facilitate the adoption of healthy lifestyle changes. Moreover, the advent of healthcare artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) algorithms presents substantial opportunities to transform health services in sub-Saharan Africa and promote health equity20,21. This progress has the potential to leapfrog healthcare in Africa into the 21st century.

Although many African nations have begun adopting digital health technologies (DHTs), challenges and opportunities for improvement remain. There have been a number of efforts by entrepreneurs, innovators, and other stakeholders to develop creative digital solutions to address local healthcare challenges, and the broad adoption of digital tools is predicted to significantly improve efficiency in healthcare spending without reducing quality by 2030. An analysis of the financial impact of DHTs showed an estimated savings of 400 million to 2.5 billion USD in Kenya, 700 million to 3.3 billion USD in Nigeria, and 1.9 billion to 11 billion USD in South Africa representing 4–14%, 4–10%, and 6–15% of projected healthcare spending in each country respectively22. These savings could potentially be redirected to other critical areas such as fair compensation for healthcare workers, improving health infrastructure, high-quality health services, and enhanced support for digital health tools, which is particularly important for financially constrained countries.

This article aims to explore and summarize the use of digital technologies for health care, emphasize relevant cardiovascular examples in various contexts within sub-Saharan Africa, highlight successful digital health initiatives, examine challenges and barriers to implementation, and provide potential solutions to effectively leverage digital technologies to transform cardiovascular care delivery.

Digital technology services and applications for healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa

Digital technologies have the potential to transform health systems across the continuum of care for patients, from diagnostics to therapeutics and long-term care15. DHTs provide a potential solution to the large cardiovascular care access gap. This section broadly examines key DHT applications and services reported in sub-Saharan Africa and pragmatic use cases (Fig. 1) based on the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of DHTs23.

Telehealth Systems

Telehealth and telemedicine

Telehealth broadly refers to the use of electronic technologies to support and promote clinical care, health education, and public health, while telemedicine is considered a specific domain of telehealth centered around real-time interactive communication between patient and clinician located at a distant site24. The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic catalyzed the adoption of telemedicine services across the world and in sub-Saharan Africa. Countries like Kenya and Rwanda launched dedicated telemedicine centers to manage COVID-19 cases, showcasing the ability to rapidly integrate and scale telemedicine services in resource-constrained environments25. Examples of digital health services to facilitate access to care and patient-doctor communications include ‘Babyl’ in Rwanda26, ‘Hello Doctor’ in South Africa27, ‘one2one’ and ‘Tremendoc’ in Nigeria28,29, and Reliance Health30, which provides telemedicine services, in-person primary care, and health plans in Nigeria. In Cameroon and Uganda, telemedicine services have been successfully utilized for transmission and remote interpretation of electrocardiograms (ECGs) and Echocardiograms31.

Communication Systems

Mobile health (mHealth)

Mobile health (mHealth) is one of the most popular forms of DHT in sub-Saharan Africa. Various studies have shown the utility of mHealth in increasing awareness of hypertension, promoting healthy behaviors, and providing clinical care32,33. A study in Nigeria showed that an mHealth application, which provided a platform for cardiologists to review patient blood pressure values and communicate with pharmacists, led to improved blood pressure control32. Similar results were replicated in Cameroon with study interventions and communication facilitated by phone calls, SMS, or voicemail34. The affordability and ubiquity of mobile devices in sub-Saharan Africa position mHealth as a unique tool for cardiovascular disease management35.

Social media

Social media platforms provide instant access to health information for connected individuals across the globe, including sub-Saharan Africa, and can facilitate disease surveillance and public health education36. Healthcare professionals, institutions, and organizations often use platforms like Facebook, Twitter (X), LinkedIn, and Instagram to deliver cardiovascular health information, share preventive measures, advertise cardiovascular care services, and engage with the public on health-related issues37,38. The wide reach and real-time interaction offered by these platforms can be useful when designing population-based cardiovascular health interventions in resource-limited settings. However, there remains a significant concern regarding its misuse for disseminating false information and advice. This issue can be mitigated by encouraging the general public to rely solely on information from trusted sources, such as local health departments, reputable academic and healthcare institutions, as well as credible international sources that provide health-related information, including United Nations agencies such as the WHO, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), among others.

Diagnostic information systems

Remote monitoring

The marked shortage of cardiologists to care for the millions of people in many regions of sub-Saharan Africa39 emphasizes the need for innovative solutions to aid diagnosis and treatment, including remote monitoring solutions. In Nigeria, the ratio of cardiologists relative to the total population is estimated at 1 to ~475,000 persons40. As of 2020, up to 18% of countries in sub-Saharan Africa did not have a registered cardiologist39. The Cardio Pad®, a portable ECG device which was developed and deployed in Cameroon utilizes non-specialist rural health workers to perform 3-lead, 6-lead, or 12-lead resting ECGs, and real-time continuous ECG monitoring using a tablet in remote villages. These ECGs can be transmitted wirelessly to cardiologists in urban centers via a mobile phone network for interpretation and management recommendations41. This technology facilitates early detection of acute coronary syndromes and arrhythmias and connects rural residents to specialized cardiovascular care. Other portable technologies evaluated for remote ECG monitoring include the AliveCor KardiaMobile, which has been approved for use in more than 25 countries42. One study evaluating the KardiaMobile device in Kenya showed a 98% acceptance rate, 100% study completion rate, and yielded a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation in 8% of the study sample43.

Biometric monitoring technologies (BioMETs)

This group of DHTs has become ubiquitous worldwide and is gaining popularity in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa as not just diagnostic tools, but also for health research, promoting healthy lifestyles, and managing chronic diseases44,45,46,47. Wearable BioMETs such as smart watches, bracelets, rings, patches, and garments paired with mobile phone apps enable users to monitor physical activity, sleep, track dietary intake, and other metrics that impact cardiovascular health48. Automated reminders from connected apps serve as motivation to continually engage in healthy behaviors with the goal of establishing good habits. Non-wearable BioMETs such as digital home blood pressure monitors, pulse oximeters, and glucose monitors provide users with the ability to monitor specific health measures at home to identify new conditions, improve treatment adherence, and guide medication management to prevent disease progression. Studies in Ghana and Nigeria have demonstrated some success in improving blood pressure control49,50,51. The use of virtual coaches, in addition to using BioMETs, to provide personalized advice and motivation to help individuals achieve health and fitness goals has also been shown to be successful in African countries52. These technologies empower users to take control of their health, make informed decisions, and adopt healthier behaviors, which are crucial for managing cardiovascular diseases53.

Decision support systems

Artificial intelligence and machine learning

The integration of AI in healthcare is poised to revolutionize patient care as we know it. The use of AI to guide echocardiographic image acquisition was shown to be feasible and effective in the identification of rheumatic mitral valve disease in Uganda54. AI-enabled ECG devices, including a digital stethoscope able to record a single lead ECG, were recently evaluated in a randomized clinical trial for peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) screening in Nigeria55- known to have the highest reported PPCM incidence worldwide. The trial results showed that AI-guided screening doubled the detection of cardiomyopathy cases when compared to usual obstetric care56. AI-enabled portable ultrasound devices are also being evaluated in obstetric care to provide high-quality imaging and analysis, to aid in the early detection of complications and improve maternal and fetal outcomes57,58,59,60. The use of hand-held portable ultrasound devices, enabled with AI, has also been demonstrated to be useful for assessment, or left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)61,62 and detection of acute complications such as pericardial effusion63 and hemoperitoneum64. AI/ML applications have been developed to target various aspects of cardiovascular medicine ranging from disease detection to image acquisition and interpretation65,66. The list of approved AI-based cardiovascular health tools in the United States is rapidly expanding67, ranging from risk prediction and notification to diagnostic and disease monitoring software. However, only a limited number of these tools have demonstrated a direct impact on clinical outcomes within the context of randomized clinical trials68. Notable examples assessed in clinical trials include enhanced detection of cardiac dysfunction using AI-enabled ECGs in primary care settings69, as well as increased efficiency among cardiologists utilizing an AI-guided echocardiography interpretation workflow, which maintains interpretation quality70. Even fewer studies and implementation examples exist in sub-Saharan Africa, making it imperative to evaluate the clinical impact of AI tools for cardiovascular applications in African settings prior to widespread adoption. AI has immense potential to address barriers to care and extend specialized cardiovascular health services to underserved areas in sub-Saharan Africa by leveraging its ability to analyze large or complex datasets to identify patterns, predict cardiovascular risks, enable diagnosis in resource-limited settings, and support targeted screening and treatment interventions. AI can also enhance the efficiency of healthcare delivery services, promote equitable access to health across regions, and identify areas where further research is needed. The advent of generative AI, particularly large language models (LLMs), may yet provide novel cardiovascular care delivery solutions, but will require further exploration71,72.

Logistics management information systems

Health supply chain management

The use of digital platforms can improve access to essential medications and medical supplies, and many countries in sub-Saharan Africa have leveraged AI and DHT solutions to improve efficiency, reduce costs, and ensure the timely delivery of essential medical supplies. Key applications have been in the areas of demand forecasting to help optimize inventory levels and avoid shortages or overstocking. Other uses include inventory management, supply chain optimization, quality control, and risk management. Rwanda has implemented a nationwide digital network for medical supply distribution. This system allows the Ministry of Health to track the distribution of medical supplies in real time from the warehouse till it gets to the patient73. Additionally, the Transforming Rwanda Medical Supply Chain (TRMS) is an initiative funded by USAID that is expected to reduce procurement lead time by 75% and lower end-user markups from 66% to 40%74. LifeBank, an organization that originally aimed to reduce maternal deaths in Nigeria caused by blood shortages, developed an online platform to connect blood banks and hospitals75,76. Blood is requested online or via an app, and the blood product requests are then fulfilled expeditiously through motorcycle dispatch riders. Over time, LifeBank has evolved to also supply medical oxygen and has expanded into Kenya and Ethiopia77. Medical drones have also been used successfully in Malawi and Ghana to deliver emergency medicines and to improve service delivery78.

Examples and pragmatic use cases of digital health technologies in sub-Saharan Africa

Across sub-Saharan Africa, numerous countries have implemented innovative digital health solutions aimed at improving healthcare access and patient outcomes. These initiatives span various aspects of healthcare delivery, from health data management and telemedicine to mobile diagnostics.

Angola

The provision of self-paced and flexible electronic learning delivered through internet-enabled mobile devices for healthcare workers, called ‘Kassai’ has demonstrated the potential to use this innovative technology to improve capacity building across public and private sectors. ‘Kassai’ was developed by the Health for All project funded by USAID with the goal to provide education on Malaria management and other key health issues79,80. This technology can be expanded across various medical specialties, including cardiovascular medicine, for health system strengthening and continuing medical education.

Ghana

‘mPedigree’, originally developed in Ghana, utilizes mobile phone SMS technology, to verify the authenticity of pharmaceutical products and provide instant feedback. It is now being used in other countries, including Kenya and Nigeria81. ‘Bisa’ is a telehealth platform developed to improve healthcare access in Ghana82. ‘Bisa’ offers mobile health care via phone or video calls, bi-directional communication with a health expert or physician, pharmaceutical services, an AI-powered chatbot for health-related questions, and personalized health and nutrition plans using AI algorithms83. The ‘AllRound Specialists Virtual Clinic’, established in 2021 and headquartered in Ghana, provides telemedicine services, including both text- and video-based consultations. The clinic also facilitates access to a range of medical specialists, encompassing cardiology and cardio-thoracic surgery84.

Kenya

‘M-TIBA’, created in 2014, is a mobile phone health wallet that provides a platform for patients to save money for health care, pay for health services or health insurance premiums, receive aid to subsidize healthcare expenses, and for institutions to share and manage care utilization and claims data. The key goals of ‘M-TIBA’ is to improve healthcare delivery, provide a sustainable healthcare financing option in a transparent manner, and reduce individual out-of-pocket expenses85.

‘Afya Rekod’, founded in 2019, is a health technology company86,87 that provides a digital platform to support individual access to, storage of, and ownership of personal health records. It also offers an electronic health record system to health institutions and physicians, as well as telehealth solutions. It also hopes to utilize AI technology in the future to detect disease outbreaks and monitor disease progression88.

Several other digital health platforms utilizing AI technology exist in Kenya including: ‘Antara Health’89 which provides virtual primary care and connects patients with subspecialty care services; ‘SIHA AI’90, a mobile app that uses computer vision to improve microscopy and tissue pathology-based diagnostics; ‘Ilara health’91 which provides a health information management system and financing for diagnostic equipment and pharmaceutical supplies; ‘Afya Pap’92, a digital health companion which offers personalized health education and coaching for management of chronic disease; and ‘Zuri Health’ which utilizes a video-based AI solution (using photoplethysmography signals) for screening and monitoring of a range of biometric parameters and cardiovascular health metrics (including blood pressure, total cholesterol, and HBA1c)93. However, there is very sparse to no data regarding the effectiveness of these AI-solutions, nor are there published validation studies in Kenya or other African countries. Nonetheless, these technological solutions have the potential to support healthcare financing options, ensure comprehensive health record keeping, and facilitate diagnostic testing for cardiovascular care, as well as establishing follow-up care with primary care providers.

Nigeria

Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and leads the continent in both the number of digital technology start-ups and venture capital investments (reaching 1.8 billion USD in 2022)94. In Nigeria, health technology start-ups rank as the third most prevalent, after Fintech and e-commerce94. As such, there are several examples in Nigeria utilizing DHT’s in innovative ways that spans the whole spectrum of healthcare infrastructure and services from health education to delivery of clinical, laboratory, and pharmaceutical services, with some examples discussed below. ‘Cutica healthcare’ provides, via a web-based portal, curated information using short entertaining write-ups or skits, both in English and pidgin English, to address health topics or popular health-related myths and practices95. This platform can be utilized to enhance the dissemination of cardiovascular health education and prevention recommendations to the public, accommodating individuals of all educational backgrounds. ‘MyItura’ developed a mobile and web-based health information system that seamlessly connects independent healthcare providers (clinicians, laboratories, pharmacies) to patients. It offers solutions that providers can use to schedule appointments, document encounters, bill, order labs, and medications for patients. Patients can control access to their own records and manage their medical records as they move from one service to another, such that results and encounter details are available to any new caregiver. Providers benefit by getting access to an integrated health information system without needing to acquire any hardware or software, or storage infrastructure. ‘MyItura’ also provides an AI assistant (chatbot) directly to consumers for health-related questions96. ‘Reliance health’ provides a platform for patients to access health services, primary care, and pharmaceuticals through various health plans. They also offer employer-based health plans that allow access to their network of health services. Members are able to schedule physician consultations and receive prescriptions through a mobile health app30. ‘Wellahealth’ provides direct-to-consumer health insurance plans and digital health care services. It supports signing up for a plan using SMS based messaging. Some of the services include direct access to a clinician via a free messaging/video calling app – WhatsApp (owned by Meta and used by over 2 billion people worldwide) as long as the user has access to the internet or a mobile data plan; and an artificial intelligence chatbot that functions as medical assistant, available at any time to provide guidance and support to patients with chronic conditions97. ‘Mobihealth’ provides 24/7 telemedicine consultations through a mobile app and connects patients in Nigeria to clinicians (with various specialty expertise) within Nigeria or a different country, including the United States and United Kingdom, essentially allowing users to access healthcare experts globally98. ‘Vitira’ is a mHealth platform developed as part of a research study99 to securely store patient health records and share with care providers at the point of care without relying on electricity or internet14. ‘Vitira’ includes three components: an encrypted handheld smartcard, a mobile phone application, and an encrypted online database, but is not publicly available for clinical use yet. ‘AVIVA’ has been used to enhance the effectiveness of cervical cancer screening by connecting non-specialist health workers with gynecologic oncologists for teleconsultation and timely review of results11. The diverse range of telehealth platforms outlined above presents a significant opportunity to enhance access to cardiovascular care services, especially considering the limited availability of specialists within the country40.

‘Helpmum’ was founded to improve maternal and infant health in Africa by leveraging cost-effective digital solutions and artificial intelligence100. Digital services provided include AI-enabled child vaccination tracking and optimizing allocation101, health information chatbots, and educational programs for community birth attendants made available as pre-recorded videos on donated electronic devices and on YouTube102. The integration of AI-driven solutions has the potential to further enhance access to innovative cardiovascular care tools through portable technologies by facilitating their expedited adoption.

Rwanda

‘Babyl Rwanda’, originally launched in 2016 to provide broad telehealth services for primary care, was successfully integrated into the existing health system, and grew rapidly to become the largest digital health service provider in Rwanda, providing up to 4000 medical consultations daily and reaching over a third of the adult population (2.5 million registered users) as of July 202326. It provided a platform for patients to access qualified physicians and nurses, schedule appointments via mobile phones with automated dial codes, receive unique prescription codes via SMS, which could be redeemed at partner pharmacies, as well as access specialty care at partner health facilities using SMS-based referral codes26. However, ‘Babyl’ ceased operations in August 2023 due to financial difficulties experienced by its parent company26. Although ‘Babyl’ demonstrates feasibility and successful adoption of DHT for healthcare, it also underscores the potential challenge of ensuring long-term sustainability in resource-limited settings with insufficient healthcare financing. This initiative clearly illustrates that telehealth represents a viable solution for Rwanda’s healthcare resource challenges, given its widespread adoption over a short period of time. Moreover, its potential extends to cardiovascular care, contingent upon establishing a self-sustaining financing model to ensure long-term success.

South Africa

With an average of 8 medical doctors per 10,000 persons103 as of 2021, the launch of the ‘Hello Doctor’ telemedicine platform eased physician workload and enhanced healthcare access in South Africa81, particularly in underserved areas. The ‘Hello Doctor’ system operates efficiently, with an average response time of 51 minutes, and a patient satisfaction survey revealed a 75% satisfaction rate27. ‘MomConnect’ is a flagship program launched by South Africa’s national department of health in 2014, designed to improve perinatal care, access, and outcomes among obstetric patients104. The program is offered through mobile phones and facilitates prenatal care registration, provision of maternal and infant health information, and an avenue to provide feedback regarding care quality104. The ‘MomConnect’ program was rapidly scaled with 50,000 women registered within the first month, and over a 3-year period, it attained the highest population-level coverage reported in the country (reaching a total of 1.7 million women, more than 60% of women attending prenatal care as of 2017)105. However, there are some concerns about the long-term self-sustainability of this initiative due to the high cost of maintenance estimated at approximately 1 million USD annually which is currently funded by the department of health, private companies, and philanthropic donors106. The two telemedicine examples mentioned above demonstrated rapid and widespread adoption, mirroring trends in other African countries, and suggest significant potential for delivering cardiovascular care, comparable to the success seen with primary and obstetric care services.

The initiatives discussed above emphasize the transformative power of digital technology in healthcare delivery across sub-Saharan Africa. By utilizing digital tools and online platforms, these countries are addressing critical healthcare challenges and enhancing access to care with the goal of improving patient outcomes.

Challenges and barriers to DHT deployment and adoption

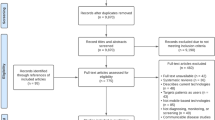

Despite the advances in sub-Saharan Africa’s digital health sector, numerous barriers and challenges must be addressed to realize its full potential (Fig. 2).

The pie chart illustrates eight key barriers (in each slice) to digital health technology implementation in sub-Saharan Africa. The four quadrants surrounding the pie chart outline proposed solutions: (1) Renewable energy and investments in ICT infrastructure, (2) Digital inclusion, education, and transformation, (3) Improve healthcare financing, (4) Clear legislative framework and guidelines. ICT - Information and Communication Technology.

Unreliable power supply and limited connectivity

A major challenge is a lack of stable power supply, limited internet connectivity, and outdated infrastructure. Many digital technologies rely on access to stable electricity and or internet connectivity, however, the infrastructure for these varies and is more often lacking across the continent. An estimated 550 million people across the continent do not have reliable access to electricity and internet services107. Furthermore, USAID estimates that approximately 100,000 public health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa do not have reliable access to electricity and internet services108. The lack of dependable electric energy sources requires the use of alternate power sources such as diesel- or petrol-powered generators, which are costly to operate and maintain, and prone to frequent mechanical malfunction109. Recurrent electric power outage and intermittent use of backup generators leaves many medical devices susceptible to damage, and consequently, the need for frequent repairs or expensive replacements109.

Financial constraints and infrastructure gaps

Poverty, limited healthcare funding options, and poor health system infrastructure pose significant challenges to large-scale implementation of digital technologies in African countries. On average, many countries in sub-Saharan allocate between 5–6% of their gross domestic product (GDP) to healthcare110 compared to wealthier countries who spend from 10–16% of GDP on healthcare111. In South Africa, critical challenges to digital healthcare transformation identified were limited government funding, reliance on secondary infrastructure from private sector companies, geographical disparities in infrastructural availability, and insufficient resources to purchase hardware and software112. These issues are similar across other countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The recent suspension of USAID funding113, coupled with uncertainties regarding its future role in sub-Saharan Africa, has placed a spotlight on the substantial adverse health consequences associated with heavy reliance on foreign aid. This situation highlights the critical and urgent need for countries in sub-Saharan to develop a diverse portfolio of financial investments and to explore innovative alternate funding sources to support healthcare financing.

Low digital literacy among healthcare workers

In Ethiopia, it is estimated that about half of healthcare workers had sufficient digital literacy levels, based on a meta-analysis of 5 studies114. Factors associated with higher digital literacy were educational attainment, high income, perceived ease of use, and a positive attitude towards digital technologies. This digital literacy gap has also been observed among the general population in sub-Saharan Africa and many individuals do not have the necessary skills to use digital tools effectively115,116. A qualitative study of healthcare professionals working in primary care representing 13 countries in sub-Saharan Africa identified low digital literacy levels and access to technology as key challenges for patients to embrace DHTs117. Among healthcare workers, key challenges were limited financial and human resources, lack of support and training, and high staff turnover rates117. Socio-cultural beliefs also contribute to resistance to DHT adoption. One study evaluating barriers to the adoption of digital health tools found some rural communities in Botswana perceived technology to negatively interfere with the sanctity of human life118. In addition, a lack of knowledge and awareness of digital health tools contributes to patient reluctance in using DHTs118.

Limited availability of large digital datasets

The implementation of AI in healthcare holds numerous benefits for patients residing in sub-Saharan Africa, including improved diagnosis, prognosis prediction, and clinical decision support, which can improve healthcare efficiency119 and consequently reduce the workload burden on the limited number of healthcare professionals and specialists. However, the development of AI algorithms relies on the availability of large, complete, digital, and labeled clinical datasets, which are mostly non-existent in sub-Saharan Africa and can be very costly and time-consuming to curate prospectively. The limited use of electronic health records is a large contributor to the paucity of health data available to train AI models66,120,121. There is some concern that the use of AI algorithms developed outside Africa, trained with data from patient populations with likely different demographic and epidemiological characteristics, may lead to biased predictions and consequent risk of harm when deployed in Africa120. Furthermore, these algorithms may lack information on unique disease states and health conditions specific to certain regions in sub-Saharan Africa, leading to limited applicability and or relevance. However, a clinical trial evaluating an AI algorithm that was developed in a US-based patient population at the Mayo Clinic was shown to have strong performance among obstetric patients in Nigeria and improved the detection of left ventricular systolic dysfunction56. The study demonstrated the importance of validating AI algorithms in specific patient populations where it is intended for use. Thorough validation remains a key component of responsible artificial intelligence122 and can potentially address the challenge related to the paucity of large digital datasets in sub-Saharan Africa.

Governance and data security challenges

The complex and evolving regulatory and policy landscape in some countries has also limited the adoption of DHT and created uncertainty123. Lack of interoperability between different DHT systems and associated data has also been identified as a challenge124. Data security is also a major concern as it relates to electronic medical records and other protected health information collected with the aid of digital technologies. While the use of hardcopy paper records does not offer complete data security, recent data breaches at large public and private companies have rekindled public unease with the collection and storage of private digital health information125. Additionally, the legal framework supporting digital healthcare and data management is underdeveloped, with unclear guidelines for accountability related to AI use for healthcare120. Recently, the European Union AI Act was passed into law and addresses the use of AI for healthcare126,127,128,129. While data protection laws exist in some African countries – such as the Nigeria data protection regulation (NDPR)130 and Egypt’s Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL)131, clear regulations specific to the use of artificial intelligence in the context of healthcare data will be required to ensure adequate healthcare AI governance in sub-Saharan Africa.

Overall, despite the challenges and barriers identified that may hinder the implementation of DHTs in sub-Saharan Africa, its potential to positively transform healthcare delivery remains strong. Many countries are making concerted efforts to address these challenges, recognizing the massive potential benefits of digital health adoption to improve health outcomes.

Potential solutions to address the digital health gap and future directions

Suggested recommendations to address existing challenges and enhance access to and availability of DHTs are identified below (Fig. 2).

Addressing power supply challenges

African countries need to consider alternative renewable energy options to address the lack of a stable electric power supply. Given the tropical climate in several regions of sub-Saharan Africa with many more hours of sunlight compared to other continents, there is substantial potential to harness solar energy as a major power source. Given the required infrastructure can be expensive to establish, government and private financial investments will be required. Companies such as Sun King (formerly Greenlight Planet), SunCulture and GridX Africa have already invested in solar energy solutions to support various sectors in multiple African countries132,133,134,135. Increased availability of affordable renewable energy sources can address the lack of a reliable electric power supply to support DHTs.

Strengthening healthcare financing through public-private partnerships and increased investment

Countries can improve healthcare financing by increasing national budgetary allocation to the healthcare sector and leveraging public-private partnerships and investment in healthcare. These investments can support the development of efficient and sustainable digital infrastructure and facilitate data curation efforts for AI model training and validation. Furthermore, public-private partnerships can enhance accessibility through cost-sharing measures as well as offering subsidized low-cost options to ensure that services remain affordable and accessible to patients across various income levels. A successful example is the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation partnering with countries like Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Malawi to support health information gathering to guide public health programs119.

Digital inclusion, health education, and transformation

Investments in information and communications technology infrastructure will be critical to narrow the digital divide and connectivity access gap. Improving the availability of affordable, high-quality internet via government and private sector investments, along with thoughtfully crafted government policies and regulation, will be essential. Creation of public health campaigns to drive awareness of DHTs and improve public education on the use of these tools can enhance public digital literacy levels. Community-based educational/training programs can also leverage existing infrastructure and human resources such as community health workers, nurses, and digital health navigators136. Curation of electronic datasets through digitization of existing medical records and prospective development of electronic health data through national registries and surveys to facilitate research and development of context-appropriate AI/ML clinical decision support tools. DHT developers and companies also need to ensure these tools employ user-friendly interfaces to increase acceptability and uptake for individuals with limited digital literacy. Capacity building through targeted educational and training sessions for clinicians and health care professionals137 can support implementation and sustainability of DHTs.

Creating a regulatory landscape for responsible AI and digital health

The development of clear legislative frameworks and guidelines related to the use of DHTs and AI for healthcare is imperative. These should outline the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders, healthcare providers, and consumers. The Digital Health Act, enacted in Kenya in 2023, serves as an exemplary model by creating safeguards to ensure data privacy and security, facilitate data sharing for health-decision making, and prevent data misuse. It also established a digital health agency to ensure accountability138.

Conclusion

The use of digital technologies and AI has the potential to improve cardiovascular care access and delivery in sub-Saharan Africa, ranging from enabling healthcare efficiency, facilitating health promotion, personalized medicine, population-based screening, and public health interventions. However, the infrastructure needed to realize the potential benefits of these tools will require investments by both public and private stakeholders. In addition, the need for prospective validation and implementation studies evaluating DHTs and healthcare AI tools in sub-Saharan Africa cannot be overemphasized. It is imperative that all stakeholders are engaged in this process, this includes governments and regulatory agencies, healthcare institutions, clinicians and allied health professionals, researchers, technology companies, and patients.

In summary, DHTs have a strong potential to enhance the quality and delivery of cardiovascular healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa. Although there are considerable challenges, we propose practical solutions to bridge the digital health gap and guide the development and implementation of digital health interventions, ensuring that the vast capabilities of these technologies are fully harnessed to advance cardiovascular care for all individuals.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

- BioMETs:

-

Biometric monitoring technologies

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DHT:

-

Digital health technology

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- E-commerce:

-

Electronic commerce

- FINTECH:

-

Financial Technology

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- LLM:

-

Large language model

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- mhealth:

-

Mobile health

- NCD:

-

Non-communicable disease

- SMS:

-

Short message service

- UNFPA:

-

United Nations Population Fund

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations Children’s Fund

- USAID:

-

United States Agency for International Development

- USD:

-

Unites States Dollar

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- 4G:

-

Fourth generation mobile phone technology

- 5G:

-

Fifth generation mobile phone technology

References

Songwe, V. The Role of Digitalization in the Decade of Action for Africa. United Nations Trade and Development News page. Accessed July 2, 2024. https://unctad.org/news/role-digitalization-decade-action-africa

Jérôme, C., CRémi, J., Karine, G. & Florian, R. The impact of digitalisation on West African cities: École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL). Accessed July 2, 2024. https://exafepfl.shorthandstories.com/the-impact-of-digitalisation-on-west-african-cities/index.html

Begazo, T., Moussa, P. B. & Mark, A. D. Digital Africa: Technological Transformation for Jobs. World Bank, Washington, DC; 2023. Accessed July 2, 2024. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/publication/digital-africa

The Mobile Economy Sub-Saharan Africa 2023. Global System for Mobile Communications (GSMA); 2023. https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-economy/sub-saharan-africa/

Measuring Digital Development Facts and Figures 2023. International Telecommunication Union: Development Sector; 2023. 2023. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.itu.int/hub/publication/d-ind-ict_mdd-2023-1/

Oleribe, O. O. et al. Identifying key challenges facing healthcare systems In Africa and potential solutions. Int J. Gen. Med. 12, 395–403 (2019).

Abubakar, I. et al. The Lancet Nigeria Commission: investing in health and the future of the nation. Lancet 399(10330), 1155–1200 (2022).

Ibeneme, S. et al. Strengthening health systems using innovative digital health technologies in Africa. Review. Front. Digit. Health. 2022-March-31 2022;4 https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2022.854339

Jérôme Chenal, C. C., Jaligot, R., Ginisty, K.& Rudaz, F. The use of digital technology in the context of West African cities. 2021. Accessed July 2, 2024. https://www.epfl.ch/research/domains/exaf/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/EXAF_rapport_DDC_juillet21_ENG_v3.pdf

Kabukye, J. K., Kakungulu, E., Keizer, N. & Cornet, R. Digital health in oncology in Africa: A scoping review and cross-sectional survey. Int J. Med. Inform. 158, 104659 (2021).

Ogunsola, O. O. et al. AVIVA: a telehealth tool to improve cervical cancer screening in resource-constrained settings. BMJ Glob. Health. 8 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012311 (2023).

Coleman, J., Eriksen, J., Black, V., Thorson, A. & Hatcher, A. The mobile alliance for maternal action text message-based mhealth intervention for maternal care in South Africa: Qualitative user study. JMIR Hum. Factors 7(2), e14078 (2020).

Omole, O. et al. The effect of mobile phone short message service on maternal health in south-west Nigeria. Int J. Health Plann. Manag. 33(1), 155–170 (2018).

Gbadamosi, S. O. et al. A patient-held smartcard with a unique identifier and an mHealth platform to improve the availability of prenatal test results in rural Nigeria: Demonstration study. J. Med. Internet Res. 20(1), e18 (2018).

Manyazewal, T., Woldeamanuel, Y., Blumberg, H. M., Fekadu, A. & Marconi, V. C. The potential use of digital health technologies in the African context: a systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia. npj Digit. Med. 4(1), 125 (2021).

Adepoju, P. Africa turns to telemedicine to close mental health gap. Lancet Digit. Health 2(11), e571–e572 (2020).

Niohuru, I. Disease Burden and Mortality. Healthcare and Disease Burden in Africa: The Impact of Socioeconomic Factors on Public Health. Springer International Publishing 35–85 (2023).

Bulto, L. N.& Hendriks, J. M. The burden of cardiovascular disease in Africa: prevention challenges and opportunities for mitigation. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvad134 (2023).

Adedinsewo, D., Omole, O., Oluleye, O., Ajuyah, I. & Kusumoto, F. Arrhythmia care in Africa. J. Inter. Card. Electrophysiol. 56(2), 127–135 (2019).

Qoseem, I. O. et al. Digital health and health equity: How digital health can address healthcare disparities and improve access to quality care in Africa. Health Promot. Perspect. 14(1), 3–8 (2024).

Schwalbe, N. & Wahl, B. Artificial intelligence and the future of global health. Lancet 395(10236), 1579–1586 (2020).

Jousset, O. et al. How digital tools could boost efficiency in African health systems. McKinsey and Company Updated March 10, 2023. Accessed July 29, 2024. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/how-digital-tools-could-boost-efficiency-in-african-health-systems.

Classification of digital interventions, services and applications in health: a shared language to describe the uses of digital technology for health, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. 2023. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/373581/9789240081949-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

Chaet, D., Clearfield, R., Sabin, J. E., Skimming, K. & On behalf of the Council on E, Judicial Affairs American Medical A. Ethical practice in Telehealth and Telemedicine. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 32(10), 1136–1140 (2017).

Dodoo, J. E., Al-Samarraie, H. & Alsswey, A. The development of telemedicine programs in Sub-Saharan Africa: Progress and associated challenges. Health Technol. 12(1), 33–46 (2022).

Kurian, O. C., Snodgrass, J. Health Equity and Inclusion in Action. Observer Research Foundation (2024).

The Health Foundation Annual Report 2024. The Health Foundation;2024. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.thehealthfoundation.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/thf_annualreport_highquality.pdf.

Lawal, L. S. et al. Digital health inclusion: a pilot study of health services deployment using communications satellite for the underserved in Nigeria (2023).

Tremendoc Limited: Doctors in your pocket. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://vc4a.com/ventures/tremendoc-limited/

Reliance Health: Human-led, tech-powered clinical services. Reliance Health Accessed July 3, 2024. https://getreliancehealth.com/clinical-services/.

Mahmoud, Z., Sanusi, M., Nartey, C. & Adedinsewo, D. Using technology to deliver cardiovascular care in African countries. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 25(12), 1823–1830 (2023).

Muiruri, C. et al. Opportunities to leverage telehealth approaches along the hypertension control cascade in Sub-Saharan Africa. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 21(10), 75 (2019).

Hacking, D. et al. Hypertension health promotion via text messaging at a community health center in South Africa: A mixed methods study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 4(1), e22 (2016).

Kingue, S., et al. Efficiency of an intervention package for arterial hypertension comprising telemanagement in a Cameroonian rural setting: The TELEMED-CAM study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 15, 153 (2013).

Manyazewal, T. et al. Mapping digital health ecosystems in Africa in the context of endemic infectious and non-communicable diseases. npj Digit. Med. 6(1), 97 (2023).

Hagg, E., Dahinten, V. S. & Currie, L. M. The emerging use of social media for health-related purposes in low and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 115, 92–105 (2018).

Ikpi, N. E. & Undelikwo, V. A. Social media use and students’ health-lifestyle modification in University of Calabar, Nigeria. Eur. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 6(1), 101–113 (2020).

Garofalo, R. et al. Evaluation of the iCARE Nigeria Pilot intervention using social media and peer navigation to promote HIV testing and linkage to care among high-risk young men: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 5(2), e220148–e220148 (2022).

Yuyun, M. F., Sliwa, K., Kengne, A. P., Mocumbi, A. O. & Bukhman, G. Cardiovascular diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to high-income countries: an epidemiological perspective. Glob. Heart 15(1), 15 (2020).

Ogah, O. S., Orimolade, O. A. & Jinadu, T. O. Cardiovascular diseases in Nigeria: Current status, threats, and opportunities. Circulation 148(19), 1441–1444 (2023).

Noubiap, J. J., Jingi, A. M. & Kengne, A. P. Local innovation for improving primary care cardiology in resource-limited African settings: an insight on the Cardio Pad(®) project in Cameroon. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 4(5), 397–400 (2014).

Faruk, N. et al. A comprehensive survey on low-cost ECG acquisition systems: Advances on design specifications, challenges and future direction. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 41(2), 474–502 (2021).

Evans, G. F., Shirk, A., Muturi, P. & Soliman, E. Z. Feasibility of Using Mobile ECG Recording Technology to Detect Atrial Fibrillation in Low-Resource Settings. Glob. Heart 12(4), 285–289 (2017).

Barteit, S. et al. Feasibility, acceptability and validation of wearable devices for climate change and health research in the low-resource contexts of Burkina Faso and Kenya: Study protocol. PLoS One 16(9), e0257170 (2021).

Matzke, I. et al. Assessment of heat exposure and health outcomes in rural populations of Western Kenya by using wearable devices: observational case study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 12, e54669 (2024).

Mvelase, P., Dlamini, Z., Dludla, A., Sithole H. Integration of smart wearable mobile devices and cloud computing in South African healthcare. 1–10 (2015).

Johnson, N. E., Venturo-Conerly, K. E. & Rusch, T. Using wearable activity trackers for research in the global south: Lessons learned from adolescent psychotherapy research in Kenya. Glob. Ment. Health. 10, e86 (2023).

Ntshumi, N. & Adebesin, F. Not missing a step: South Africans taking control of their personal wellbeing using wearable health devices. J. Health Inform. Afr. 6(2), 11–18 (2019).

Commodore-Mensah, Y. et al. Addressing Hypertension Care in Africa (ADHINCRA): Study protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled pilot trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 125, 107077 (2023).

Commodore-Mensah, Y. et al. Abstract 15333: The addressing hypertension care in Africa (ADHINCRA) Study: A multi-level nurse-led, mobile-health enhanced intervention to improve hypertension control in Ghana. Circulation 148(Suppl_1), A15333–A15333 (2023).

Nelissen, H. E. et al. Pharmacy-based hypertension care employing mHealth in Lagos, Nigeria – a mixed methods feasibility study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18(1), 934 (2018).

Ogboye, A., Rahman, K. M. J., Odukwe, A. & Mobisson, N. Digital Interventions To Drive Self-Management In People With Hypertension In Nigeria. J. Hypertens. 40(Suppl 1), e196 (2022).

Wongvibulsin, S., Martin, S. S., Steinhubl, S. R. & Muse, E. D. Connected Health Technology for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Management. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 21(6), 29 (2019).

Peck, D. et al. The use of artificial intelligence guidance for rheumatic heart disease screening by novices. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 36(7), 724–732 (2023).

Adedinsewo, D. A. et al. Screening for peripartum cardiomyopathies using artificial intelligence in Nigeria (SPEC-AI Nigeria): Clinical trial rationale and design. Am. Heart J. 261, 64–74 (2023).

Adedinsewo, D. A., et al. Artificial intelligence guided screening for cardiomyopathies in an obstetric population: a pragmatic randomized clinical trial. Nat. Med. 2024;https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03243-9.

Pokaprakarn, T. et al. AI estimation of gestational age from blind ultrasound sweeps in low-resource settings. NEJM Evid. 1(5), EVIDoa2100058 (2022).

Toscano, M. et al. Diagnosis of pregnancy complications using blind ultrasound sweeps performed by individuals without prior formal ultrasound training. Obstet. Gynecol. 141(5), 937–948 (2023).

Gomes, R. G. et al. A mobile-optimized artificial intelligence system for gestational age and fetal malpresentation assessment. Commun. Med. 2(1), 128 (2022).

AI-enabled ultrasound: Working toward a world where healthy mothers give birth to healthy babies with next-generation technology. Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Accessed July 29, 2024. https://www.gatesfoundation.org/ideas/science-innovation-technology/future-womens-health-technology/ai-ultrasounds.

Motazedian, P. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound with artificial intelligence-assisted assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction. npj Digit. Med. 6(1), 201 (2023).

Kagiyama, N. et al. Multicenter validation study for automated left ventricular ejection fraction assessment using a handheld ultrasound with artificial intelligence. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 15359 (2024).

Yıldız Potter İ, Leo, M. M., Vaziri, A. & Feldman, J. A. Automated detection and localization of pericardial effusion from point-of-care cardiac ultrasound examination. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 61(8), 1947–1959 (2023).

Leo, M. M. et al. Using deep learning to detect the presence and location of hemoperitoneum on the focused assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) Examination in Adults. J. Digit. Imaging 36(5), 2035–2050 (2023).

Elias, P. et al. Artificial intelligence for cardiovascular care—Part 1: Advances. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83(24), 2472–2486 (2024).

Antia, S. E. et al. Artificial Intelligence and Cardiology Practice in Nigeria: Are We Ready?. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 27(8), 933–937 (2024).

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Enabled Medical Devices. US Food and Drug Administration. Updated May 13, 2024. Accessed July 18, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-aiml-enabled-medical-devices.

Ouyang, D. & Hogan, J. We need more randomized clinical trials of AI. NEJM Ai. 1(11), AIe2400881 (2024).

Yao, X. et al. Artificial intelligence–enabled electrocardiograms for identification of patients with low ejection fraction: a pragmatic, randomized clinical trial. Nat. Med. 27(5), 815–819 (2021).

He, B. et al. Blinded, randomized trial of sonographer versus AI cardiac function assessment. Nature 616(7957), 520–524 (2023).

Howell, M. D., Corrado, G. S. & DeSalvo, K. B. Three Epochs of artificial intelligence in health care. JAMA 331(3), 242–244 (2024).

Wachter, R. M. & Brynjolfsson, E. Will generative artificial intelligence deliver on its promise in health care?. JAMA 331(1), 65–69 (2024).

African Healthcare Network: A Case Study on the Healthcare Supply Chain of Rwanda. One Network Enterprises. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.onenetwork.com/supply-chain-management-resources/papers/case-study-healthcare-supply-chain/.

Transforming Rwanda Medical Supply Chain: Improving the Efficiency of Rwanda’s Health Supply Chain. USAID; 2024. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2024-04/TRMS-2024.pdf.

Brian Trelstad PTA, Wale Lawal. LifeBank Nigeria. Havard Business School 2020. October 2, 2020. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=59052.

Ramachandran, V., et al. The New Economy of Africa: Opportunities for Nigeria’s Emerging Technology Sector. Center for Global Development 2019. November 12, 2019. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://metaintelligence.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/new-economy-africa-opportunities-nigerias-emerging-technology-sector.pdf.

LifeBank in Ethiopia, The Next Chapter in Our Story. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://lifebankcares.medium.com/lifebank-in-ethiopia-the-next-chapter-in-our-story-300f01eb5d5b.

Mwonzora EAAaG. Medical Drones in Africa: A Gamechanger for the Continent’s ‘Ailing’ Health Sector? European Association of Development Research and Training Institutes. Updated September 4, 2024. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.developmentresearch.eu/?p=1800.

Berlin, E., Lourenço, C., Poyer, S. Surveillance for Action: Operationalizing Private Sector Surveillance and Service Delivery across the Malaria Transmission Continuum. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hygiene. 1(aop) (2024).

Anya Fedorova, J. P. Efficient and Convenient Remote Capacity Building of Frontline Health Workers in Angola. Population Services International (PSI). Updated March 18, 2021. Accessed July 29, 2024. https://www.psi.org/2021/03/efficient-and-convenient-remote-capacity-building-of-frontline-health-workers-in-angola/.

Adekoya, O. O. et al. Digital health: a tool for mitigating health workforce brain drain in Africa. Pan Afr. Med J. 45, 172 (2023).

Onuoha, C. Telehealth in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Human-Centered Design Approach to Bridging Gaps in Healthcare and Wellbeing Across the African Diaspora. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2022.

Bisa - a telemedicine mobile health platform. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://bisaapp.com/about-us/.

AllRound Specialists Virtual Clinic. Accessed February 14, 2025. https://myhealth.asvclinic.com/.

Huisman, L. et al. A digital mobile health platform increasing efficiency and transparency towards universal health coverage in low- and middle-income countries. DIGITAL Health. 8, 20552076221092213 (2022).

Kitili, J., Karanja, N. The new wave of eHealth: AI and privacy concerns? A case study of Kenya. CIPIT- Strathmore University 2023. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/000b82d8-ceb2-4c3d-94b1-357839684a5c/content.

Signé, L. Strategies for Effective Health Care for Africa in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution; 2021. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Strategies-for-effective-health-care-delivery-in-Africa_FINAL.pdf.

Wasonga, M. Afya Rekod Launches AI Platform To Curb Pandemic. CIO Africa. Updated March 25, 2020. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://cioafrica.co/afya-rekod-launches-ai-platform-in-support-of-global-efforts-to-curb-corona-pandemic/.

Antara Health. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://www.antarahealth.com/.

SIHA Artificial Intelligence - Mobile-Based Precision AI Medical Diagnostics. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://sihaai.com/.

Ilara Health. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://www.ilarahealth.com/providers.

Transforming access to Care, One Digital Step at a Time. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://www.baobabcircle.com/.

Zuri Health - AI Vitals Sign Screening. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://zuri.health/aiscreening/demo.

The State of Tech In Africa 2023. AfricArena; 2023. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://www.africarena.com/_files/ugd/0da073_08aec517db784543b2802cd80330a491.pdf

CUTICA Health - Your Health and Wellness Partner. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.cuticahealth.com/

MyItura. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://www.myitura.com/

Wellahealth. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://wellahealth.com/Home/About.

Mobihealth. Updated 2024. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://mobihealthinternational.com/about-us.

Ezeanolue, E. E. et al. An mHealth Framework to Improve Birth Outcomes in Benue State, Nigeria: A Study Protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 6(5), e100 (2017).

Improving Maternal and Infant Healthcare in Africa with AI and low cost Innovations. Helpmum. Accessed October 30, 2024. http://helpmum.org/.

Kehinde O. et al. Deploying ADVISER: Impact and lessons from using artificial intelligence for child vaccination uptake in Nigeria. 22185-22192 (2024).

HelpMum E-Learning Platform. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.helpmum.org/elearning.

Medical doctors (per 10,000 population). World Health Organization. Accessed July 18, 2024. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/medical-doctors-(per-10-000-population).

Barron, P. et al. Mobile health messaging service and helpdesk for South African mothers (MomConnect): history, successes and challenges. BMJ Glob. Health 3(Suppl 2), e000559 (2018).

Peter, J., Benjamin, P., LeFevre, A. E., Barron, P. & Pillay, Y. Taking digital health innovation to scale in South Africa: ten lessons from MomConnect. BMJ Glob. Health 3(Suppl 2), e000592 (2018).

Jahan, R. Impact of MomConnect program in South Africa: A narrative review: OJNI. On - Line J. Nurs. Inform. Summer Summer 2020 2023-11-30. 24(2) (2020).

Digital healthcare in Africa essential for saving lives - but electricity and knowledge shortfalls prove barriers. Omnia Health. Updated October 27, 2021. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://insights.omnia-health.com/show-news/digital-healthcare-africa-essential-saving-lives-electricity-and-knowledge-shortfalls.

USAID. Powering Health. United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Accessed September 7, 2024. https://www.usaid.gov/powerafrica/powering-health.

Energizing Africa’s health care: how electricity helps make people better. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/partner-content-energizing-africas-health-care.

Bilal, W. et al. Improving access to maternal care in Africa through telemedicine and digital health. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 37(4), 2494–2500 (2022).

Kirigia, D., Okungu, V. & Chuma, J. Distribution of public health care spending: a comparative analysis of Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Latin America and high income countries. Afr. J. Health Econ. 2, 47–72 (2013).

Zharima, C., Griffiths, F. & Goudge, J. Exploring the barriers and facilitators to implementing electronic health records in a middle-income country: a qualitative study from South Africa. Front. Digit. Health 5, 1207602 (2023).

American chaos: standing up for health and medicine. Lancet. 2025;405(10477):439.

Chereka, A. A. et al. Evaluating digital literacy of health professionals in Ethiopian health sectors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 19(5), e0300344 (2024).

Kwakwa, V. Empowering Africa’s youth: Bridging the digital skills gap. Updated July 15, 2024. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/nasikiliza/empowering-africa-s-youth-bridging-the-digital-skills-afe-gap.

Kronke, M. Africa’s digital divide and the promise of e-learning. Afrobarometer; 2020. June 2020. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/pp66-africas_digital_divide_and_the_promise_of_e-learning-afrobarometer_policy_paper-14june20.pdf.

O’Brien, N. et al. Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats analysis of the use of digital health technologies in primary health care in the Sub-Saharan African Region: Qualitative study. J. Med Internet Res. 25, e45224 (2023).

Dodoo, J. E., Al-Samarraie, H. & Alzahrani, A. I. Telemedicine use in Sub-Saharan Africa: Barriers and policy recommendations for Covid-19 and beyond. Int. J. Med. Inform. 151, 104467 (2021).

Musa, S. M. et al. Paucity of health data in Africa: An obstacle to digital health implementation and evidence-based practice. Public Health Rev. 44, 1605821 (2023).

Owoyemi A., Owoyemi J., Osiyemi A., Boyd A. Artificial intelligence for healthcare in Africa. Opinion. Front. Digit. Health. 2020-July-07 2020;2 https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2020.00006.

Dalhatu, I., et al. From paper files to web-based application for data-driven monitoring of HIV Programs: Nigeria’s journey to a National Data repository for decision-making and patient care. Methods Inf. Med. 62(3-04), 130–139 (2023).

Perez-Downes, J. C. et al. Mitigating Bias in clinical machine learning models. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 26(3), 29–45 (2024).

Klaaren, F. C. A South African Public Law Perspective on Digitalisation in the Health Sector. Oxford University, Blavatnik School of Government; 2021. July 6, 2021. https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/publications/south-african-public-law-perspective-digitalisation-health-sector.

Ibeneme, S. et al. Strengthening capacities among digital health leaders for the development and implementation of national digital health programs in Nigeria. BMC Proc. 14(10), 9 (2020).

Mitchell, M. & Kan, L. Digital technology and the future of health systems. Health Syst. Reform. 5(2), 113–120 (2019).

EU AI Act: first regulation on artificial intelligence. European Parliament. Updated June 18, 2024. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20230601STO93804/eu-ai-act-first-regulation-on-artificial-intelligence.

European Parliament Briefing - Artificial Intelligence Act European Union/European Parliamentary Research Service 2024. February 9, 2024. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/698792/EPRS_BRI(2021)698792_EN.pdf.

Busch, F. et al. Navigating the European Union Artificial Intelligence Act for Healthcare. npj Digit. Med. 7(1), 210 (2024).

Aboy, M., Minssen, T. & Vayena, E. Navigating the EU AI Act: implications for regulated digital medical products. npj Digit. Med. 7(1), 237 (2024).

Nigeria Data Protection Regulation 2019: Implementation Framework. NITDA; 2020. November 2020. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://nitda.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/NDPR-Implementation-Framework.pdf.

Egypt: Law 151/2020 on the Protection of Personal Data. International Labour Organization; 2020. July 14, 2020. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://natlex.ilo.org/dyn/natlex2/natlex2/files/download/111246/EGY111246%20Eng.pdf.

Munro, P., Jacome, V. & Samarakoon, S. Off-Grid Enterprise: A Critical History of Small-Scale Off-Grid Solar in Sub-Saharan Africa. In: Ojong N., ed. Off-Grid Solar Electrification in Africa: A Critical Perspective. Springer International Publishing; 2022:25–64.

About Sun King: We’re on a mission to power access to brighter lives. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://sunking.com/about-sun-king/.

Toesland F. Start-ups powering up Africa’s solar energy ecosystem. Updated January 25, 2024. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/january-2024/start-ups-powering-africa’s-solar-energy-ecosystem.

GridX Africa - Powering Africa’s Energy Transition. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://www.gridxafrica.com/.

Rodrigues, S. M. et al. Digital health-enabled community-centered care: scalable model to empower future community health workers using human-in-the-loop artificial intelligence. JMIR Form. Res. 6(4), e29535 (2022).

Borges do Nascimento, I. J. et al. Barriers and facilitators to utilizing digital health technologies by healthcare professionals. NPJ Digit. Med. 6, 161 (2023).

Wanyama, E. Does Kenya’s Digital Health Act Mark A New Era for Data Governance and Regulation? Updated May 3, 2024. Accessed September 7, 2024. https://cipesa.org/2024/05/does-kenyas-digital-health-act-mark-a-new-era-for-data-governance-and-regulation/.

Acknowledgements

Figure illustrations created with BioRender.com. Dr. Adedinsewo is supported by the Mayo Clinic Center for Women’s Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.A.S.O.: Wrote sections of the initial draft; created figures for the manuscript; contributed to critical review, writing, and revisions of the manuscript; approved the final version of the manuscript. J.A.O.: Wrote sections of the initial draft; contributed to critical review, writing, and revisions of the manuscript; approved the final version of the manuscript. A.E.: Wrote sections of the initial draft; contributed to critical review, writing, and revisions of the manuscript; approved the final version of the manuscript. S.M.S.: Contributed to critical review, writing, and revisions of the manuscript; approved the final version of the manuscript. F.K.: Contributed to critical review, writing, and revisions of the manuscript; approved the final version of the manuscript. O.O. Contributed to critical review, writing, and revisions of the manuscript; approved the final version of the manuscript. K.O.O. Contributed to critical review, writing, and revisions of the manuscript; approved the final version of the manuscript. N.I.A. Contributed to critical review, writing, and revisions of the manuscript; approved the final version of the manuscript. J.O.O. Contributed to critical review, writing, and revisions of the manuscript; approved the final version of the manuscript. E.E.E. Contributed to critical review, writing, and revisions of the manuscript; approved the final version of the manuscript. D.A. Conceptualized the paper; wrote sections of the initial draft; created figures for the manuscript; contributed to critical review, writing, and revisions of the manuscript; approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Kuti is the founder and chief executive officer of Reliance Health. Dr. Ogunyankin is the chief medical director at First Cardiology Consultants (FCC) Healthcare. The other authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Segun-Omosehin, O.A., Omiye, J.A., Elalfy, A. et al. Evaluating the digital health technology landscape in sub-Saharan Africa and its implications for cardiovascular health. npj Cardiovasc Health 2, 20 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-025-00055-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-025-00055-9

This article is cited by

-

The evolving landscape of cardiovascular health in Africa: insights from WHO AFRO

Nature Medicine (2025)