Abstract

Wearable cardiovascular monitoring systems integrate advanced sensing technologies to provide real-time, personalized, and noninvasive healthcare through continuous monitoring and early warning capabilities, representing significant progress in accuracy, personalization, and connectivity. This review summarizes recent advances in wearable physical sensors, imaging technologies, and biochemical devices tailored for cardiovascular health monitoring, explores developments in early warning and closed-loop systems, and discusses future research directions and associated challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) poses a grave threat to public health, exhibiting alarming rates of mortality and disability. The total number of individuals living with CVD has nearly doubled from 271 million in 1990 to 535 million in 2022. Concurrently, the number of deaths attributable to CVD has steadily risen from 12.1 million in 1990 to 19.8 million in 2022. In 2022, the global mortality rate was 396 million deaths, with 44.9 million of these deaths resulting from disability. This indicates that approximately one-third (34%) of cardiovascular deaths occur before the age of 70 ref. 1,2. It not only precipitates acute events, including acute myocardial infarction and acute heart failure, but also engenders chronic conditions such as stroke, profoundly impacting patients’ quality of life and posing substantial health burdens ref. 3,4,5. Hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia—chronic conditions that also frequently coexist with CVD—not only elevate the risk of cardiovascular events but also contribute to organ damage and dysfunction across multiple systems ref. 6,7,8,9,10. Furthermore, CVD frequently intertwines with other health maladies, fostering a pernicious cycle of decline ref. 11.

Existing medical equipment, such as echocardiography and coronary computed tomography angiography, suffers from issues of point measurement and an inability to conduct comprehensive assessments. They can only provide local monitoring and are incapable of dynamically tracking systemic vascular changes. Additionally, traditional medical equipment is inadequate in monitoring sudden-onset conditions. For example, the detection of atrial fibrillation may be delayed, preventing timely early warnings. In contrast, wearable devices significantly enhance the efficiency of early screening and round-the-clock management of cardiovascular health through continuous dynamic monitoring, multi-modal data integration, and real-time alerting capabilities ref. 12,13. Through the persistent surveillance of pivotal physiological parameters, wearable sensors exhibit a remarkable capability to promptly identify deviations within the cardiovascular system ref. 14,15,16. This early detection affords crucial therapeutic windows for patients, thereby effectively mitigating the progression of their condition and substantially diminishing the incidence of morbidity and mortality associated with cardiovascular events ref. 17,18. The deployment of diverse wearable sensors holds the promise of enabling more refined early warning systems and potentially even the realization of closed-loop therapeutic interventions for cardiovascular-related diseases ref. 19.

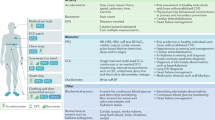

Wearable sensors for cardiovascular monitoring constitute a diverse spectrum of devices, encompassing physical sensors, advanced imaging technology, and biochemical sensors, each tailored to offer insights into various facets of cardiovascular health and function. Physical sensors, through their sophisticated mechanisms, translate diverse signals encompassing light intensity, electrical activity, and pressure into cardiovascular parameters of critical importance, namely electrocardiograms, oxygen saturation levels, and pulse rates. This conversion is achieved by leveraging technologies such as photoplethysmography (PPG) sensors, pressure sensors, and skin electrodes, which meticulously detect and interpret these foundational signals ref. 20,21,22. Furthermore, advancements in imaging technology, particularly those achieved through the innovative application of flexible ultrasound skin patches, have revolutionized our ability to acquire high-resolution visualizations of deep vascular blood flow dynamics, cardiac structures, and various other organs ref. 23. These technological strides offer unprecedented insights into the intricate physiology and functional status of these critical systems ref. 24. Concurrently, Biochemical sensors, employing intricate chemical reactions, detect an array of biomarkers pertinent to cardiovascular disease from various body fluids, including sweat, saliva, and tears. These biomarkers encompass glucose levels in the blood, cholesterol concentrations, lactate production, cardiac enzymes, and inflammatory mediators, each offering a window into the cardiovascular health status. This advanced sensing capability facilitates the comprehensive analysis of biochemical signals, providing valuable insights into the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases ref. 25. The convergence and deployment of pioneering technologies, notably flexible electronics, miniaturization, and wireless communication, have facilitated the emergence of wearable sensors seamlessly incorporated into skin patches or intelligent apparel. The compact size and versatile integration capabilities of wearable sensors make them highly promising for applications in early warning systems and closed-loop control systems ref. 26. These sophisticated systems integrate an extensive array of wearable sensors, enabling real-time data monitoring, swiftly generating timely alerts upon the detection of anomalies, and autonomously initiating tailored interventions based on the comprehensive analysis of monitoring outcomes. These innovations have bestowed upon us the capability to monitor physiological parameters continuously and in real-time, heralding profound implications for the realms of health management, disease prophylaxis, diagnostics, and treatment (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Wearable sensors for cardiovascular applications encompass physical, imaging, and electrochemical sensors. The integration of multiple sensors, communication systems, and algorithms has the potential to facilitate early warning systems and closed-loop control mechanisms for disease management. Clockwise direction: “Pulse Wave60”, “Electrocardiogram106”, “Blood Pressure Sensors”, “Blood Flow Sensors171”, “Ultrasound Imaging184”, “Blood Glucose Sensors205”, “Other Cardiovascular-related Biochemical Sensors237”, “Disease Early Warning Systems255”, “Closed-loop Systems267”.

In this comprehensive review, we meticulously delineate the cutting-edge advancements and technological merits of contemporary wearable physical sensors, wearable imaging technologies, and flexible biochemical devices tailored for cardiovascular health. We undertake a rigorous comparison of the strengths and limitations of each sensor, employing diverse metrics pertinent to cardiovascular health assessment. Furthermore, we delve into the evolution of early warning systems and explore the development of closed-loop control systems, offering insights that resonate with the latest trends in this dynamic field. Ultimately, we delineate the existing challenges, delve into potential trajectories, and sketch out the horizons for forthcoming research endeavors.

Pulse wave sensors

Pulse wave measurement is a key diagnostic tool for assessing cardiovascular health by analyzing pulse wave propagation ref. 27,28. Pulse wave velocity (PWV) is a critical indicator of vascular stiffness ref. 29,30, with elevated PWV linked to cardiovascular diseases, atherosclerosis, and other conditions ref. 31,32. Regular PWV measurement can aid in early detection of cardiovascular risks and enhance disease prevention. Additionally, Pulse wave analysis (PWA) provides insights into heart rate variability (HRV), reflecting autonomic nervous system function ref. 33,34. Higher HRV typically indicates better cardiovascular health, while lower HRV is associated with conditions such as anxiety, depression, and heart disease ref. 35,36,37. In sports medicine, pulse wave monitoring helps optimize training, reduce injury risk, and improve performance ref. 38. Wearable pulse wave monitoring technologies primarily include optical sensors and pressure sensors.

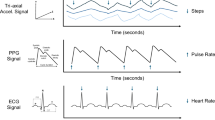

Optical sensors for pulse wave

PPG is a widely used optical technique for biomedical monitoring, typically comprising a light-emitting diode (LED) and a photodetector (PD). The LED emits light (e.g., green, red, or near-infrared) that penetrates the skin and interacts with blood. Changes in arterial blood volume during the cardiac cycle modulate light absorption, and the PD detects the reflected or transmitted signal, converting it into an electrical waveform synchronized with blood flow dynamics. This signal is used to extract physiological parameters such as heart rate, pulse waveform, and oxygen saturation ~39. As shown in Fig. 2a, a typical PPG waveform contains a slowly varying direct current (DC) component, related to tissue structure and average blood volume, and a pulsatile alternating current (AC) component, reflecting cardiac-induced blood volume changes. The AC frequency corresponds to heart rate and is superimposed on the DC baseline, which can also vary with respiration ref. 40. Based on light path, wearable PPG sensors are classified into transmission- and reflection-based configurations. Clinically deployed devices (finger/ear clips) typically use transmission-mode PPG, which provides higher SNR and superior accuracy and repeatability for SpO2 and heart-rate measurements, and remains more reliable under low perfusion in quiet or monitored settings. However, these probes are often wired and conspicuous, limiting subject mobility and making them unsuitable for continuous, all‑day monitoring. By contrast, reflective PPG has somewhat lower SNR and signal fidelity, but this can be partly mitigated by algorithmic optimization and multi‑channel fusion. Reflective sensors can be worn at the wrist, chest or other sites and integrated into watches and wearables, enabling long‑term, wireless, around‑the‑clock monitoring and broadening their prospects for everyday health surveillance.

a The Principle of measuring pulse wave with PPG ref. 40. b PPG sensors based on the transmissive principle ref. 41,42. c PPG sensors based on the reflective principle ref. 46. d Body location selection strategies for transmissive and reflective PPG sensors. The areas highlighted in green are suitable for operation in transmissive mode sensors, while the sensing locations highlighted in purple are suitable for operation in reflective mode ref. 48. e Multi-light PPG sensor for pulse monitoring ref. 59. f PPG sensors integrated with solar cells ref. 60. g Dome microstructure piezoresistive pressure sensors72. h Piezoresistive pressure sensors array integrated with transistors ref. 73. i The schematic principle of measuring different pressures through capacitance pressure sensors ref. 77. j Capacitive pressure sensor with microstructure for programmable fabrication ref. 79,80. k Magnetoelastic pressure sensors for pulse wave monitoring ref. 82. l Piezoelectric pressure sensors inspired by human muscle fibers for pulse wave monitoring ref. 78. m Triboelectric sensors for pulse wave monitoring and the operational mechanism ref. 87,88.

Transmissive PPG sensors utilize light passing through the skin to provide a clearer representation of blood circulation, offering improved accuracy in cardiac rhythm and oxygen saturation measurement. The light penetration reduces interference from ambient light and surface reflections. However, to achieve deeper tissue penetration, transmissive PPG sensors require light sources with higher power, increasing energy consumption, a major current research direction is to boost detector responsivity (output current per incident optical power) through materials development, thereby reducing overall power consumption. Commercial PPG detectors have largely relied on single-crystal inorganic materials (Si, Ge, GaInAs), which are costly, mechanically rigid, and temperature-sensitive. In contrast, organic semiconductors are cheaper, solution-processable, tunable, and mechanically flexible, attracting attention for integrated photodetection. Huang et al. developed a PD using a novel ultranarrow-bandgap nonfullerene acceptor, achieving over 0.5 A/W responsivity in the NIR region (920–960 nm), the highest reported for organic PDs. These devices also exhibited specific detectivity up to 1012 Jones, comparable to commercial silicon photodiodes. Using this device, a volunteer’s heart rate was measured at rest and after exercise. In both conditions, the PPG waveform showed the characteristic systolic and diastolic peaks. Heart rates, computed as 60 divided by the averaged interbeat interval, were 67 and 106 bpm at rest and post-exercise, respectively. (Fig. 2b) ref. 41,42.

Reflective PPG sensors emit light from LEDs onto the skin, where it is modulated by capillaries and reflected back to PDs, providing pulse wave data. Unlike transmissive sensors, reflective PPG sensors do not require placement on areas like the ear or finger, making them suitable for use on sites such as the wrist or other skin surfaces for prolonged wear. These sensors are also easier to integrate into commercial wearable devices, such as bracelets and watches ref. 43,44. Ultra-thin, flexible PPG sensors are crucial for long-term health monitoring. Optimizing sensor flexibility and thickness improves skin adhesion, reducing interference from ambient light and motion while enhancing signal quality. Yokota et al. demonstrated a highly efficient, ultraflexible three-color polymer light-emitting diode and organic photodetector system, which unobtrusively measured blood oxygen levels when placed on the finger. The total device thickness was just 3 mm, thinner than the epidermis ref. 45. Most sites suitable for long-term wear are three-dimensionally curved. To maintain comfort, sensors should conform as closely as possible to these surfaces, applying minimal pressure to the skin. Wu et al. developed a patch-type system integrating flexible perovskite PDs and inorganic LEDs for real-time PPG monitoring. The use of three-dimensional (3D) wrinkled-serpentine interconnections improved the device’s adaptability to curved surfaces, maintaining excellent functionality even at significant bending angles (60°) (Fig. 2c) ref. 46. However, reflection-mode PPG is generally less precise than transmission-mode PPG for detecting small microvascular changes. Reflection-mode relies on skin-adjacent diffuse backscatter, making the signal more vulnerable to ambient light and noise. Besides, green illumination common in reflection-mode is more strongly absorbed by melanin, reducing accuracy for darker skin and often requiring extra calibration. The detected light in reflection-mode mainly comes from superficial epidermal/dermal layers, where melanin content strongly modulates absorption and thus the pulsatile amplitude and SNR. By contrast, transmission-mode light traverses thicker tissue to sample deeper vessels, so skin-color effects along the path are averaged and pulsatile interference is smaller, though total intensity can still vary with skin color ref. 47. Reflective sensors are more suitable for areas like the wrist, forearm, and abdomen, while regions with thinner tissue and higher capillary density, such as the earlobes and fingers, are better for transmissive sensors (Fig. 2d) ref. 48.

PPG sensors with a single light source are valued for their simple design, cost-effectiveness, and compactness but suffer from limited sensitivity, susceptibility to interference, and shallow data acquisition ref. 49,50. To address these limitations, multi-light-source PPG sensors have gained attention for their ability to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, reduce motion artifacts, and capture vascular information at various depths. These sensors facilitate the precise computation of cardiovascular metrics51,52 and are essential for measuring oxygen saturation ref. 53. Oxygen saturation calculation relies on the distinct absorption properties of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin at different wavelengths, with combined light sources used to exploit these profiles. Multi-light-source PPG sensors enable non-invasive, two-dimensional oxygen saturation mapping, promising advancements in real-time and postoperative monitoring of tissues, wounds, and organs ref. 54,55,56. Khan et al. developed a flexible printed sensor array using organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) and photodiodes, capable of detecting reflected light and accurately measuring oxygen saturation, with an average error of 1.1%. This system also generated two-dimensional oxygenation maps of the forearm under ischemic conditions ref. 48. Traditional multi-source sensors, however, suffer from high power consumption, limiting their use in continuous monitoring. Lee and colleagues addressed this by creating a reflective, ultra-low-power patch-type sensor using red and green OLEDs and organic photodiodes, operating at just 24 milliwatts ref. 57. Although multi-light-source sensors mitigate noise issues associated with single substrates, signal precision remains affected. To overcome this, Lee’s team developed a fiber-optic quantum dot PPG system, enhancing sensitivity and minimizing substrate-related noise ref. 58. Multi-light-source sensors, by generating richer datasets, create a better foundation for algorithmic processing, especially machine learning. Franklin et al. integrated multiple synchronized PPG sensors into a wireless dermal system, using data to build a support vector machine model for categorizing hemodynamic states influencing blood pressure, cardiac output, and vascular resistance (Fig. 2e) ref. 59.

PPG sensors are among the most energy-intensive components in wearable devices due to their reliance on LED light sources. Self-powered sensors address this challenge by eliminating the need for frequent recharging, thereby allowing continuous monitoring and enhancing the practical utility of wearable technologies. A promising solution for self-powering PPG sensors involves the integration of solar cells. Jinno et al. developed an ultraflexible, self-powered organic optical system for PPG sensors, combining air-stable polymer light-emitting diodes, organic solar cells, and organic photodetectors (Fig. 2f) ref. 60. Similarly, Sun et al. introduced a solution-process approach for fabricating wearable self-powered PPG sensors with a three-layer device architecture for organic photovoltaics, photodetectors, and light-emitting diodes. Their device demonstrated comparable performance and enhanced stability compared to a sophisticated reference device with evaporated electrodes. This integration facilitates the development of a self-powered, long-term health monitoring system ref. 61.

In summary, despite the extensive use of PPG sensors for monitoring physiological signals, such as pulse wave, their signals remain susceptible to various factors, including skin temperature, skin pigmentation, physical activity, and lighting conditions ref. 62,63,64. Furthermore, miniaturization and flexibility of the devices are needed to enable continuous, long-term, comfortable monitoring. Moreover, in specific patient demographics, including individuals with hypotension or compromised blood circulation, PPG sensors are unable to capture physiologically relevant cardiovascular signals effectively. Addressing these challenges is of paramount importance for the advancement of PPG sensors in the future.

Pressure sensors for pulse wave

Pressure sensors detect pulse waves by measuring the pressure transmitted to the skin surface from the cyclic expansion and contraction of blood vessel walls with each heartbeat. These sensors convert pressure variations into electrical signals, providing extensive cardiovascular information. Unlike PPG sensors that capture signals from capillaries, pressure sensors typically measure pulse waves from larger arteries, offering richer physiological insights. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practitioners similarly palpate the wrist to assess pulse characteristics, reflecting their analogous function ref. 65. Although not yet widely adopted in clinical practice, their ability to sustain continuous monitoring under challenging conditions (movement and underwater) endows them with potential for large-scale deployment in the future.

Pressure sensors can be classified based on operational principles, including resistive, capacitive, magnetoelectric, piezoelectric, and triboelectric sensors ref. 66. Resistive pressure sensors are widely used, relying on changes in the conductive pathway structure within the material due to external pressure. This shift alters the sensor’s resistance, enabling pressure inference ref. 67,68. To enhance sensitivity, resistive sensors often employ microstructural patterns, such as pyramids and microspheres ref. 69,70,71, improving responsiveness to subtle pressure changes. Lee et al. developed a high-performance electronic skin with interlocked microspheres, achieving excellent conformal adaptability for precise pulse measurements (Fig. 2g) ref. 72. Variations in the arterial pulse location can complicate sensor placement; to streamline this process, Baek et al. created a method for spatiotemporal measurement of arterial pulse waves using wearable active matrix pressure sensors, fabricated via inkjet printing of thin-film transistor arrays, enhancing diagnostics in cardiovascular diseases (Fig. 2h) ref. 73.

Capacitive pressure sensors measure pressure through capacitance changes between conductors, offering faster response times than resistive sensors and reduced sensitivity to temperature variations ref. 74,75,76. While both capacitive and piezoresistive sensors share similarities in design, capacitive sensors may introduce non-linearity, necessitating complex data processing for accurate output. Lv et al. developed a self-wrinkling dielectric layer using Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and Polydimethylsiloxane, achieving enhanced sensitivity with a linear range extending up to 21 kPa and a detection limit of 0.2 Pa which covers the 0.5–5 kPa window for extracting skin-surface pulse signals (Fig. 2i) ref. 77. Yang et al. introduced an innovative fabrication method for a flexible pressure sensor that demonstrates remarkable sensitivity and precision in pulse detection ref. 78. Ruth et al. improved manufacturing processes with a pyramid microstructured layer, yielding tunable and reproducible sensors for applications like extracorporeal pulse sensing (Fig. 2j) ref. 79,80.

Magnetic-effect-based sensors like Hall sensors leverage changes in magnetic fields due to mechanical deformation, distinguishing themselves with high durability and reliability for physiological signal measurement. However, challenges remain in their application for wearable devices, including the mechanical properties of traditional materials ref. 81. Zhao’s group shows that the magnetoelastic effect can be harnessed in flexible fibers to yield a textile magnetoelastic generator that converts arterial pulses into electrical signals. The detection limit reaches as low as 0.05 kPa, well below the 0.5 kPa required for epidermal pulse‑wave sensing, enabling more precise measurement of human pulse signals. The sensor has been demonstrated to operate unencapsulated on sweat-saturated skin and even underwater, a capability that paves the way for all‑weather, long‑term pulse monitoring (Fig. 2k) ref. 82.

Self-powered pressure sensors, utilizing piezoelectric or triboelectric principles, alleviate energy constraints for continuous monitoring ref. 83. Chu et al. created a piezoelectric pulse sensing system capable of detecting subtle vibrations in the human radial artery, showcasing precision and stability, akin to TCM diagnostic methods ref. 84. Su et al. explored piezoelectric sensors based on muscle fiber analogs to enhance robustness and adhesion, suitable for pulse wave measurement and motion monitoring (Fig. 2l) ref. 78. Despite their promise, piezoelectric sensors face challenges, including thermal sensitivity and limited static pressure measurement capabilities ref. 85. Triboelectric sensors operate on the contact electrification effect, offering flexibility and affordability for diverse applications in biomedicine and sports ref. 86. Motion artifacts is a common challenge in pulse testing. While clinically, patients typically remain stationary in bed, making this issue negligible, motion by subjects cannot be entirely avoided during wearable, long-term pulse signal monitoring. Therefore, acquisition devices must minimize or suppress motion artifacts. Meng et al. designed a highly sensitive and conformal pressure sensor inspired by kirigami structures to measure pulse waves during movement, exhibiting excellent sensitivity and stability. Moreover, this sensor is integrated into a wireless cardiovascular monitoring system capable of real-time transmission of pulse signals to a smartphone, and it operates normally during motion ref. 87. Fang et al. developed a lightweight textile triboelectric sensor for continuous pulse monitoring in dynamic environments, achieving high fidelity and accuracy (Fig. 2m) ref. 88. While triboelectric sensors represent a promising direction for environmentally friendly pressure sensing, they still require advances in stability and linear response to broaden their practical applications ref. 89.

Electrocardiogram sensors

Electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring is essential in cardiovascular health management90,91, aiding in the detection of cardiac issues such as arrhythmias92,93,94, myocardial ischemia95,96,97, and myocardial infarction ref. 98,99,100. Early detection enables timely interventions, reducing the risk of complications ref. 101. ECG results provide critical clinical insights, informing personalized treatment plans, including medication adjustments102,103, interventional therapies, or surgery. Conventional electrocardiography requires adhesive electrodes at multiple body sites wired to a recorder, precluding comfortable long‑term monitoring. Given the episodic nature of cardiovascular events, prolonged cardiac assessment and surveillance are essential; flexible wearable devices are uniquely suited to this task ref. 104. The advent of wearable electronics has addressed these limitations by integrating electrodes with advanced systems capable of autonomous sensing and data processing, enabling prolonged, comfortable ECG monitoring. ECG sensors can be broadly classified into two main categories: wet electrodes and dry electrodes. Furthermore, an emerging technology has come to prominence, involving non-contact ECG techniques that obviate the requirement for direct electrode-skin contact.

Wet electrodes for ECG

Wet electrodes are characterized by their moisture content, which reduces contact impedance, thereby minimizing signal interference and improving signal quality ref. 105. Addressing the challenges associated with moisture evaporation in long-term wearable devices, skin adaptability, and stable data measurement under various complex environmental conditions—such as underwater and high-temperature settings—remains fraught with numerous obstacles. A prevalent challenge in the field of wet electrodes is ensuring seamless integration between the skin and electronic devices while allowing the skin to breathe freely. Cheng et al. developed an ultra-thin hydrogel that conforms to skin contours without air gaps, offering high water vapor permeability, mechanical compliance, and biocompatibility, with a usability period exceeding one week (Fig. 3a) ref. 106. Aquatic ECG enables underwater monitoring of vital signals, potentially preventing heart attacks—a leading cause of death among divers ref. 107. Ji et al. addressed the challenge of maintaining electrode adhesion and conductivity in water by creating a waterproof electrode with a metal-polymer composite substrate and dopamine polymer coating, ensuring reliable ECG signal acquisition in aquatic environments (Fig. 3b) ref. 108. This innovation supports real-time cardiac monitoring during swimming, enhancing health surveillance in aquatic settings. Elasticity in epidermal electrodes is critical for comfort and performance. Lu’s team developed a flexible conductive nanocomposite using hydrogels as energy-dissipating interfaces, significantly enhancing stretchability by over fivefold. This approach enabled the fabrication of multifunctional wearable sensors for skin monitoring and cardiac patches for intrabody detection ref. 109.

a Ultra-thin hydrogel ECG electrodes that fit perfectly with the skin ref. 106. b Wet electrodes for underwater ECG monitoring ref. 108. c Dry electrodes for long-term ECG monitoring ref. 110. d Biomimetic design of ECG dry electrode for enhanced adhesion ref. 111. e Principle of non-contact ECG sensors ref. 114. f Electrodes, acquisition circuits, and photos of non-contact ECG sensors worn on the human body ref. 114. g The non-contact ECG sleep monitoring system ref. 116.

Dry electrodes for ECG

Dry electrodes are gaining prominence in ECG monitoring due to their advantages over wet electrodes, including the elimination of conductive gel, ease of use, reduced skin irritation, and improved portability and storage ref. 105. However, their performance is hindered by suboptimal conformability to the skin during physical activity and perspiration, leading to increased impedance and motion artifacts. Ensuring comfortable, long-term skin contact while maintaining high-quality signal acquisition is a critical challenge. Zhang et al. developed an intrinsically conductive polymer dry electrode with exceptional self-adhesion, extensibility, and conductivity. This electrode significantly reduces skin contact impedance and noise during both static and dynamic measurements, enabling reliable ECG, EMG, and EEG signal acquisition under various conditions, including dry and moist skin, and during physical movement (Fig. 3c) ref. 110. Even after 16 hours of continuous wear, it maintained superior performance without causing skin discomfort. In current clinical practice, electrodes widely used for 12-lead ECG measurements primarily consist of Ag/AgCl coupled with conductive gel, which exhibit excellent performance in resting ECG. However, their insufficient skin adhesion poses challenges for monitoring during physical activity, or in moist/submerged environments. In nature, the microchannels on tree frog toe pads and the suckers of octopuses facilitate strong adhesion to objects in wet/submerged settings. Drawing inspiration from these biological structures, Kim et al. developed a biomimetic skin patch. Its structurally biomimetic design drastically enhances electrode adhesion, particularly in motion, moist, and submerged environments where conventional electrodes often fail. This electrode creates a vacuum chamber between itself and the contact surface via an octopus sucker-like structure, physically boosting adsorption. The eco-friendly, residue-free patch boasts good biocompatibility, with a hexagonal architecture featuring raised cup-shaped grooves that ensure high breathability, excellent water drainage, and enhanced adhesion. It maintains improved skin contact even during sweating or water exposure (Fig. 3d) ref. 111.

Non-contact ECG sensors

Non-contact ECG monitoring represents a cutting-edge advancement in cardiac signal detection, utilizing capacitive coupling to measure ECG signals through intervening layers such as hair, fabric, and insulators (Fig. 3e) ref. 112,113,114. Unlike traditional contact electrodes, non-contact capacitive electrodes offer a more convenient and comfortable recording method, eliminating the need for electrical leads and adhesive electrodes. This technology, initially proposed by Richardson, uses a thin aluminum oxide layer as a dielectric medium for bioelectrical signal detection ref. 115. Wang et al. developed a polymer foam with a low surface resistance of 0.05 ohms per square inch to enhance capacitive coupling between the body and electrode surface, achieving non-contact ECG recordings with a signal-to-noise ratio of 29.8 dB and a heart rate measurement accuracy of 99.5% compared to wet contact ECG (Fig. 3f) ref. 114. To address the limitations of traditional contact ECG, Wang et al. introduced a non-contact sleep ECG system that uses capacitive coupling and a flexible electrode array to capture signals through sleepwear and bed linens, achieving an signal-to-noise ratio exceeding 30 dB and enabling accurate respiratory wave extraction (Fig. 3g) ref. 116. To improve signal quality, Chen et al. developed a self-regulating non-contact sensing smart garment that monitors the capacitive properties of the skin-electrode interface in real time, with an attenuation compensation mechanism that adjusts for changes in fabric composition and interface conditions ref. 117. Non-contact ECG eliminates the discomfort and dermal irritation associated with direct skin contact, making it especially beneficial for sensitive populations, including the elderly and those with dermatological issues. Despite current challenges with environmental noise and electromagnetic interference, ongoing technological advancements hold promise for the future of non-contact ECG in cardiac health monitoring.

Blood pressure sensors

Blood pressure (BP) monitoring is critical for cardiovascular health118, as hypertension is a leading risk factor for conditions such as heart disease, stroke, and heart failure ref. 119,120,121. Regular BP assessment enables early detection and management of hypertension, reducing the risk of cardiovascular events ref. 122,123,124. Common BP measurement techniques in clinical practice today include the oscillometric method, auscultatory method, and invasive arterial catheterization (employed in intensive care). While the accuracy of these approaches has been extensively validated clinically, they are not suitable for long-term, non-invasive, and comfortable blood pressure monitoring. Continuous monitoring of BP fluctuations is essential for effective personal health management and cardiovascular disease prevention ref. 125. Currently, wearable BP monitoring devices have been developed by Huawei, CNSystems, and Samsung, utilizing oscillometric methods (Fig. 4a)126,127, the vascular unloading technique (Fig. 4b)128,129, and PPG (Fig. 4c) ref. 130,131. However, challenges remain regarding measurement precision, comfort during prolonged use, and the necessity for frequent calibration. Emerging BP measurement technologies based on alternative principles, such as ultrasound, pressure sensors, and multi-signal analysis, are gaining traction due to their potential advantages.

a Blood pressure measurement watch based on the oscillometric technique. b Wearable blood pressure device based on the vascular unloading technique. c Blood pressure measurement watch based on the PPG technique. d Stretchable ultrasound sensors for blood pressure measurement ref. 136. e Pressure sensors for blood pressure measurement ref. 140. f PTT and PAT for blood pressure measurement ref. 131. g PAT wireless measurement system ref. 148. h PTT measurement system based on PPG and ECG ref. 149. i PTT measurement system based on IPG sensors ref. 152.

Ultrasound sensors for BP

Ultrasound sensors are widely used in hemodynamic monitoring and medical imaging, employing piezoelectric transducers to convert electrical signals into ultrasonic pulses. These pulses, typically in the range of 20 kHz to several MHz, penetrate the skin and reflect off deeper tissues, with the transducer capturing the echoes and converting them back into electrical signals. The cross-sectional area of arteries is a reliable indicator of blood pressure, as fluctuations in blood pressure correlate with changes in arterial dimensions. In contrast, conventional non-invasive methods, such as PPG, are limited to superficial vascular systems and cannot access central blood pressure waveforms from deeper vessels like the carotid and jugular arteries. Accurate prediction of these waveforms is critical for reducing cardiovascular mortality132,133,134. Traditional ultrasonic probes face challenges such as bulkiness and rigidity, which hinder stable coupling with tissue surfaces and limit long-term continuous monitoring. Wang et al. introduced a wearable ultrasonic device that conforms to the skin’s contours, enabling the capture of blood pressure waveforms from deep arterial and venous sites135. This ultra-thin (240 μm) and highly elastic device (stretchability up to 60%) allows non-invasive, continuous monitoring of cardiovascular parameters across multiple anatomical sites. However, the device’s transducer elements, designed for large central arteries, have limited efficacy for smaller peripheral arteries, such as the brachial and radial arteries. The absence of a backing layer also impedes accurate tracking of minute arterial expansions, particularly in stiff peripheral arteries. To address these issues, Zhou et al. redesigned the transducer array and added a backing layer to enhance alignment and accuracy. The re-engineered wearable sensor features a compact linear array with a closely spaced acoustic window (ref. 10mm), minimizing misalignment and improving measurement reliability. The incorporation of a backing layer enhances the accuracy of arterial wall detection. Blood pressure waveforms obtained from this sensor closely match those from conventional cuff-based measurements (Fig. 4d)136. Ultrasound blood pressure sensors offer a unique advantage by providing waveforms from deeply embedded vasculature, a feat other sensor types cannot achieve. These sensors are particularly suitable for continuous, long-term monitoring. However, the complexity of device design and signal processing, along with potential interference from skin thickness, tissue composition, and environmental factors, may affect accuracy. Despite these challenges, wearable ultrasound sensors hold significant potential for real-time, dynamic blood pressure monitoring and clinical decision-making137,138.

Pressure sensors for BP

Compared to ultrasonic devices, pressure sensors offer a streamlined design, cost-effectiveness, and straightforward signal processing, making them promising for continuous BP monitoring. The primary methods for BP measurement using pressure sensors are PWA, which evaluates pulse wave morphology and velocity, and tensometry, which measures pulse wave intensity under varying static pressures to determine the equilibrium pressure between the interior and exterior of the artery. However, the accuracy of these methods remains controversial due to the lack of accurate transfer functions to convert sensor signals into BP values and insufficient clinical validation of measurement precision139. Min et al. introduced a wearable piezoelectric BP sensor (WPBPS) for continuous non-invasive arterial pressure monitoring. They developed a linear regression-based transfer function to convert sensor signals into BP readings, achieving mean discrepancies of -0.89 ± 6.19 mmHg and -0.32 ± 5.28 mmHg compared to a commercial sphygmomanometer. The integration of the WPBPS into a wristwatch highlights its potential for portable, continuous BP monitoring in cardiovascular diagnostics (Fig. 4e)140. Traditional Chinese medicine pulse diagnosis, which relies on palpating the wrist to assess a patient’s health, suggests the existence of latent physiological information within arterial pulsations. While the method has not gained widespread acceptance due to its subjective nature, sensor-based data acquisition and analytical algorithms may help validate its scientific basis141,142,143. Wang’s team developed a flexible pressure sensor array integrated into an adaptive wristband system, enabling precise identification of pulse characteristics and BP metrics, including systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial pressure, through a machine learning-based model144. Despite the promise of pressure sensors for continuous BP monitoring, their accuracy remains influenced by factors such as tissue composition, sensor positioning, and static pressure applied to the sensor.

Multi-sensor analysis for BP

Pulse transit time (PTT) and pulse arrival time (PAT) are key parameters in assessing cardiovascular health, reflecting the impact of blood pressure on pulse wave propagation12. Both require the use of multiple sensors and signal analysis from modalities such as impedance plethysmography (IPG), ECG, PPG, ballistocardiography, seismocardiogram, and pressure sensors. PAT represents the time for the pulse wave to travel from the heart to a distal site, while PTT measures the time between pulse detection at proximal and distal sites, such as the arm and finger, or between two distal sites like the finger and toe131. Blood pressure fluctuations affect pulse wave velocity: higher blood pressure increases wave speed due to decreased arterial compliance, while lower blood pressure slows wave propagation (Fig. 4f)145. PTT and PAT are commonly measured using ECG and PPG sensors. However, traditional systems require multiple cables and rigid sensors, which can be harmful to sensitive skin, especially in infants146,147. To address this, Chung et al. introduced ultra-thin, flexible, wireless skin-like electronic devices for ECG and PAT measurement (Fig. 4g)148. Xu et al. developed a flexible, epidermal near-infrared PPG sensor integrating low-power organic phototransistors and inorganic light-emitting diodes (Fig. 4h)149. Validation against a commercially available cuff-based PPG sensor showed a mean absolute difference of less than 5 mmHg in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, demonstrating high accuracy. IPG is an innovative, non-invasive technique for assessing peripheral arterial impedance, which correlates with arterial cross-sectional area, a key factor in blood pressure regulation150. Patil et al. introduced a blood flow monitoring system based on IPG, successfully estimating hemodynamic parameters across a range of conditions151. Huynh et al. demonstrated the feasibility of IPG for measuring PTT and estimating blood pressure, with results closely aligned to medical-grade devices (Fig. 4i)152. While multi-sensor methods based on PTT and PAT show promise, their accuracy is influenced by the dynamic nature of physiological states, requiring frequent recalibration for precise blood pressure estimation.

Blood Flow Sensors

Cardiovascular pathologies such as atherosclerotic stenosis, thrombosis, embolism, aneurysmal dilation, and valvular regurgitation not only affect vital signs like heart rate and blood pressure but also lead to significant hemodynamic changes in the cardiac chambers and vasculature, including alterations in blood flow153,154,155,156. These conditions often remain undetected until they progress into critical emergencies, as they are typically asymptomatic. Thus, detecting hemodynamic changes is crucial for early diagnosis and prevention157. Thus, detecting hemodynamic changes is crucial for early diagnosis and prevention157. During intensive care and surgery, hemodynamic monitoring provides critical guidance for selecting and adjusting treatment strategies. In current clinical practice, non-invasive approaches, including echocardiography and pulse wave-based non-invasive cardiac output monitoring, are primarily used for hemodynamic assessment in general patients. For critically ill patients, invasive methods such as arterial catheterization, central venous catheters, and pulmonary artery catheters are typically employed. However, none of these approaches are suitable for continuous, routine monitoring158,159,160. As a result, the development of compact, portable, and wearable blood flow sensors with high precision is essential for effective cardiovascular health management. Currently, wearable devices for blood flow monitoring primarily utilize thermal analysis and Doppler-based principles, including ultrasound, laser, and photoacoustic technologies.

Thermal Analysis For Blood Flow

Thermographic analysis for blood flow measurement is based on the principles of thermal conduction and temperature variation161. This method infers blood velocity and volume by monitoring the effects of blood flow on the thermal field. By applying a heat source to a blood vessel or tissue, the surrounding blood flow alters heat transmission and distribution, allowing for indirect estimation of blood flow velocity162. Increased blood flow enhances heat transfer efficiency, leading to measurable temperature changes compared to static conditions. Applications of thermographic analysis include assessing vascular function, evaluating blood vessel compliance and reactivity, and monitoring tumor blood supply, as well as facilitating cardiovascular research related to blood flow alterations due to various lesions163. In wearable thermal analysis devices, the temperature acquisition module is critical. Effective integration of sensitive, and compact temperature sensors is vital for the performance of these analytical tools. Webb et al. introduced an ultra-thin, flexible epidermal sensor technology that conforms to the skin, allowing for continuous thermal characterization with millikelvin precision and enabling quantitative assessment of tissue thermal conductivity164. This technology provides insights into the temporal dynamics of blood flow and perfusion, laying the groundwork for advanced thermal analysis-based blood flow sensors. Building on this progress, a development further enhanced this skin-conforming sensor technology, demonstrating sensitivity and accuracy in assessing macrovascular and microvascular flows across various physiological states (Fig. 5a)163. Krishnan et al. developed a platform integrating a thermal sensor and actuator array for accurate and continuous measurement of flow through subcutaneous shunts (Fig. 5b)165. Clinical studies confirmed the sensor’s capability to differentiate baseline flow from diminished flow and distal shunt failure. However, the deployment of thermal analysis equipment can introduce measurement inaccuracies due to placement discrepancies on the skin. To mitigate this, Tian et al. reported the design of a high-precision, long-term epidermal blood flow sensor that adapts to these variabilities (Fig. 5c)166. This sensor significantly enhances the signal-to-error ratio when measuring high-throughput blood flow (100 to 600 mL/min), achieving blood flow resolution of 10 to 50 mL/min in preclinical validation against Doppler ultrasound. Despite its viability, thermographic analysis has limitations, including the capacity to provide only relative changes in flow rates167 and its confinement to monitoring the superficial vascular system168. Additionally, the technique’s spatial resolution is relatively low, making it challenging to obtain precise data on variations in blood flow within small vascular or tissue regions.

a Structure of the thermal analysis sensors and photos integrated with human skin163. b Thermal analysis sensor for human blood flow monitoring165. c Self-adaptive epidermal thermal analysis sensors prevent measurement errors caused by variations in mounting position166. d Doppler principle for blood flow measurement169. e Laser Doppler blood flow measurement system for PAD patients169. f Wearable laser Doppler blood flow sensors while running170. g Flexible ultrasound transducers for blood flow monitoring171. h Ultrasensitive ultrasonic blood flow sensor capable of mitigating measurement inaccuracies caused by Doppler angle discrepancies167. i Photoacoustic blood flow sensors168.

Doppler-baseD Sensors For Blood Flow

The Doppler effect refers to the change in observed frequency of a wave due to relative motion between the source and observer, with applications across acoustics, optics, and electromagnetic waves. Blood flow sensors that utilize this effect include acoustic Doppler, laser Doppler, and photoacoustic Doppler sensors. Figure 5d illustrates the principle of laser Doppler velocimetry, which employs laser light to illuminate the bloodstream, using moving erythrocytes as scatterers169. The frequency of the scattered light changes based on the velocity (v) of the red blood cells in peripheral arteries, resulting in a frequency shift. The variable fshift encapsulates the fluctuations in v, while the polarity of fshift serves as an indicator of the direction of blood flow, whether it be towards or away from the sensory system169.

Laser Doppler sensors are particularly suited for microcirculatory blood flow measurements, such as in peripheral arterial disease (PAD), a common condition that narrows arteries and reduces blood flow to extremities, increasing cardiovascular disease risk. Awan et al. developed a compact wearable monitoring system that employs the Doppler effect alongside optoelectronic sensing technology for independent blood flow monitoring in PAD patients, minimizing dynamic artifacts by avoiding optical filters or fibers (Fig. 5e)169. To address the limitations of traditional flowmeters, which are often bulky and sensitive to movement, Iwasaki et al. created a microelectromechanical systems-based wearable laser Doppler flowmeter that captures signals stably during physical activity (Fig. 5f)170. This device demonstrates remarkable sensitivity for detecting low-velocity blood flows, though its penetration depth is limited to superficial tissues and is influenced by environmental factors.

Ultrasonic Doppler sensors operate on a similar principle, utilizing high-frequency sound waves to monitor blood flow. The frequency shifts of scattered waves provide information about the velocity of blood flow even from deeper tissues. Wang et al. developed a skin-conforming ultrasonic phased-array capable of monitoring hemodynamic signals from as deep as 14 centimeters, demonstrating the ability to capture Doppler spectra and central blood flow waveforms in healthy volunteers (Fig. 5g)171. However, optimal Doppler angles for accurate velocity assessments are below 60 degrees, with reduced precision as the angle approaches 90 degrees. Wang et al. also introduced a stretchable ultrasound device optimized for continuous monitoring of blood flow velocities in deeply situated arteries, using a dual-beam Doppler technique to negate angle effects (Fig. 5h)167. The superior penetration capability of ultrasound Doppler devices allows for real-time monitoring of hemodynamic dynamics but suffers from lower spatial resolution compared to other imaging modalities, particularly when imaging through bone172.

Photoacoustic Doppler sensing is an emerging technology that combines the photoacoustic effect with Doppler principles. In this approach, laser pulses incident on the bloodstream are absorbed by erythrocytes and cause thermal expansion, generating ultrasonic waves. Jin et al. developed a flexible optoacoustic “stethoscope” using a microlens array and piezoelectric polyvinylidene fluoride thin film for acoustic detection. This device enables continuous, non-invasive monitoring of cardiovascular biomarkers, such as hypoxia and hemodynamics (Fig. 5i)168. Although this technology integrates advantages from both acoustical and optical Doppler devices, challenges remain, including varying tissue absorption and scattering effects, which influence data accuracy. Additionally, photoacoustic imaging requires advanced signal processing and may be limited by imaging speed, but its potential in biomedical applications is significant173,174.

Ultrasound imaging sensors

Imaging technology holds a central position in the evaluation of cardiovascular health and the diagnosis of related diseases175. It offers a unique capability to display cardiac structures, vascular morphologies, and hemodynamic characteristics in a non-invasive and clear manner, furnishing physicians with a meticulously detailed and intuitive diagnostic foundation176. Furthermore, this technology enables real-time monitoring of cardiac function, facilitating the timely detection and early warning of potential cardiovascular risks177. Consequently, it provides robust support for the formulation of precise treatment plans, the assessment of treatment efficacy, and prognostic evaluations. Indeed, it serves as an indispensable tool in the development of accurate therapeutic strategies, the evaluation of treatment responses, and the assessment of disease prognosis. Among the array of imaging modalities, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound imaging constitute the cornerstone of cardiovascular imaging178. CT reconstructs 3D images by rotating X-ray projections, thereby precisely delineating the intricate details of blood vessels179. MRI, leveraging magnetic fields and radiofrequency wave resonance, offers a non-invasive portrayal of the heart’s comprehensive structural and functional landscape180. Meanwhile, ultrasound imaging, utilizing ultrasound wave reflection technology, monitors the heart’s motion and hemodynamics in real-time, establishing itself as the bedrock for the screening and follow-up of cardiac diseases181. Notably, the noninvasive attribute, coupled with real-time imaging capabilities, straightforward operational ease, relatively economical pricing, and a broad spectrum of applications, collectively render ultrasound imaging technology an alluring choice for medical practitioners182.

In recent years, portable ultrasound imaging technology has gained considerable significance for research endeavors aimed at real-time visualization of cardiovascular and other tissue and organ structures. Ultrasonic imaging sensors achieve continuous non-invasive monitoring through miniaturized flexible probes. For example, wearable ultrasonic patches can dynamically assess left ventricular ejection fraction and hemodynamic parameters, overcoming the limitations of traditional ultrasound, which requires a fixed site and is limited to single examinations. Their clinical relevance is demonstrated in real-time perioperative monitoring of organ function (such as efficacy evaluation after atrial fibrillation ablation). Compared to traditional ultrasound equipment, the wearable design supports continuous imaging during movement, reducing interference from motion artifacts and enhancing data reliability. A recent publication by Hu et al. introduces an innovative wearable ultrasound device, specifically designed to facilitate continuous, real-time, and direct assessment of cardiac function183. They made high-density multilayered stretchable electrodes based on a composite of eutectic gallium–indium liquid metal and SEBS. The incorporation of novel device design and materials has resulted in a substantial improvement in the mechanical coupling between the device and human skin, enabling effective examination of the left ventricle from various angles, even during physical exercise (Fig. 6a). Despite these advancements, further enhancements are necessary in terms of the device’s penetration depth and spatial resolution. To address this issue, Hu et al. undertook further development, creating a stretchable ultrasound array capable of performing continuous non-invasive elastography measurements of tissues at a depth of 4 cm beneath the skin, with a spatial resolution of 0.5 mm (Fig. 6b)184. These studies continue to encounter hurdles in the realm of continuous imaging of internal organs during prolonged motion. The deformation of extensible flexible ultrasound probes, in conjunction with the dynamic contours of the skin, introduces perturbations in the relative positioning of the sensing unit, thereby impacting the precision of the imaging procedure. In response, Wang et al. have devised a bioadhesive ultrasound (BAUS) device, which comprises a thin, rigid ultrasound probe securely attached to the skin via a coupling agent formulated from a soft, tough, dehydration-resistant, and bioadhesive hydrogel-elastomer blend (Fig. 6c)185. The BAUS couplant effectively transmits acoustic waves, insulates the BAUS probe from skin deformation, and maintains robust and comfortable adhesion on the skin over 48 hours.

a Schematics showing the exploded view of the wearable ultrasound imager, with key components labeled (left) and its working principle (right)183. b Schematics of the stretchable ultrasonic array laminated on a soft tissue and a 3D quantitative elastographic image of a porcine abdominal tissue by the stretchable ultrasonic array184. c Ultrasonic device consists of a thin and rigid ultrasound probe robustly adhered to the skin via a couplant made of a soft, tough, antidehydrating, and bioadhesive hydrogel-elastomer hybrid185. d Schematic of the working configuration and simulation results of diverging and focused ultrasound fields based on 2D matrix array beamforming188. e Schematic of a cUSBr-Patch on the body and exploded view of the cUSBr-Patch to illustrate its four main components189. f Schematic of the operation of a handheld probe on the human’s lower abdomen for bladder imaging and schematic of the cross-sectional view of the cUSB-Patch on the lower abdomen190. g Photograph of the encapsulated USoP laminated on the chest for measuring cardiac activity via the parasternal window. The inset shows the folded circuit191.

In addition to direct monitoring of the cardiovascular system, the health status of other tissues and organs can impact cardiovascular health, either directly or indirectly186,187. Wearable ultrasound imaging has gained widespread utilization for surveillance of cerebrovascular and other critical organs and tissues, including the breast and bladder, underscoring its versatility and practicality in clinical practice. This holistic approach to detection and management is instrumental in effectively decreasing the risk profile for cardiovascular mishaps and their sequelae. These devices offer real-time data to aid in the clinical management of diseases, enabling more precise condition assessments and the formulation of personalized treatment plans. Zhou et al. developed a conformal ultrasound patch designed for hands-free volumetric imaging and continuous monitoring of cerebral blood flow (Fig. 6d)188. This patch utilizes 2 MHz ultrasound waves to effectively mitigate cranial-induced attenuation and phase aberration. Furthermore, a copper mesh shield ensures conformal skin contact and enhances the signal-to-noise ratio by 5 dB. The ultra-fast ultrasound imaging technique, based on evanescent waves, accurately renders the three-dimensional morphology of Willis’ circle, minimizing the potential for human error during the examination. Meanwhile, Du et al. introduced a wearable, form-fitting ultrasound breast patch (cUSBr-Patch) that facilitates standardized and reproducible image acquisition across the entire breast (Fig. 6e)189. The patch’s design, inspired by the natural honeycomb-like structure, is integrated with phased-array technology guided by an easy-to-operate tracker, providing capabilities for large-area, deep-scanning, and multi-angle breast imaging. Furthermore, Zhang et al. described a conformal ultrasound bladder patch consisting of multiple phased arrays embedded in a stretchable substrate (Fig. 6f)190. This device enables mechanically robust, conformal, and in vivo volumetric organ monitoring. The bladder volumes estimated using this patch were comparable to those obtained with standard clinical ultrasound equipment.

The aforementioned studies predominantly concentrate on wearable ultrasound probes that lack autonomous operational capability, necessitating wired connections to devices for data acquisition and analysis. This limitation precludes the achievement of genuine wearability. To overcome this limitation, Li et al. developed a fully integrated autonomous wearable ultrasonic-system-on-patch (USoP) (Fig. 6g)191. This system incorporates a miniaturized and flexible control circuit, which is seamlessly connected to the ultrasound transducer array for signal preprocessing and wireless data communication. Additionally, machine learning methodologies were employed to track mobile tissue targets and enhance data interpretation. On mobile subjects, the USoP can continuously monitor physiological signals, including central blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output, for as long as 12 h. This result enables continuous autonomous surveillance of deep tissue signals toward the internet-of-medical-things.

Biochemical sensors

Wearable biochemical sensors are defined as instrumental devices capable of converting biochemical signals emitted by organisms into measurable electrical signals or other quantifiable formats. An illustrative example is the utilization of electrochemical sensors, which employ electrochemical reaction processes to determine the concentration of analytes in biological samples. Biochemical indicators such as blood glucose, cholesterol, uric acid, lactate, electrolytes (e.g., sodium, potassium), urea, and inflammatory cytokines can be obtained from human sweat, saliva, tears, and other bodily fluids. The relationship between these indicators and cardiovascular health is of paramount importance. Among them, blood glucose, cholesterol, uric acid, lactate, and inflammatory cytokines are particularly crucial and frequently used, as they reflect the physiological and pathological states of the cardiovascular system and serve as fundamental bases for assessing cardiovascular health, predicting disease risks, and formulating treatment strategies. Biochemical sensors are revolutionizing traditional clinical practices through non-invasive/minimally invasive detection technologies (such as sweat and saliva analysis). By utilizing flexible electrochemical patches as an alternative to venous blood sampling, they enable continuous and dynamic monitoring of key indicators, including glucose, uric acid, and inflammatory factors. This approach not only circumvents the limitations of conventional single-point tests (which require laboratory analysis and result in delayed reporting), but also breaks through the efficiency bottleneck of traditional item-by-item testing by enabling simultaneous multi-indicator detection (e.g., graphene arrays for concurrent analysis of cholesterol, C-reactive protein [CRP], and electrolytes).

Blood glucose sensors

Blood glucose monitoring holds paramount importance in the realm of cardiovascular health, as it serves as a vital sentinel for the early identification of aberrant glucose fluctuations192. These fluctuations exhibit a robust correlation with the risk profile for cardiovascular disease193,194. Traditional approaches to blood glucose monitoring predominantly rely on a punctual measurement procedure, which involves the utilization of a needle to obtain a blood sample, followed by a chemical interaction between this sample and test strips within a glucometer. This methodology is constrained to furnishing blood glucose levels at a solitary point in time, thereby precluding continuous, real-time surveillance of glucose fluctuations195,196,197. However, the significance of continuous blood glucose monitoring cannot be overstated in the context of diabetes management. Diabetic patients experience glucose level variations that can be influenced by an array of factors, including diet, physical activity, and pharmacological interventions, with these variations potentially posing severe health implications198,199.

At present, a variety of commercially viable wearable glucose monitoring devices, particularly those produced by Abbott and Dexcom, employ subcutaneously implanted microneedle technology to facilitate continuous glucose monitoring200. The utilization of microneedle technology in this context boasts distinct advantages, notably its minimally invasive approach, which mitigates patient pain and discomfort while enabling uninterrupted monitoring of blood glucose levels. This continuous assessment aids patients in gaining a comprehensive understanding of their blood glucose dynamics, thereby enhancing the management of diabetes mellitus201. Nonetheless, this technology is not devoid of challenges; specifically, the microneedle may experience suboptimal adhesion following skin insertion due to bodily movements, potentially resulting in heightened measurement inaccuracies. Furthermore, despite the relative sophistication of microneedle technology, a residual infection risk persists, necessitating rigorous attention to hygiene practices, including sterilization procedures and the timely replacement of microneedles during utilization.

To advance the field of non-invasive blood glucose monitoring, researchers have delved into the electrochemical analysis of diverse bodily fluids, encompassing sweat, saliva, and tears. This endeavor is grounded in the recognition that these fluids harbor glucose concentrations, which, to a certain extent, mirror blood glucose levels202. In practice, aliquots of these fluids are interfaced with specialized sensors or test strips, where glucose undergoes enzymatic reactions—typically involving glucose oxidase—to elicit measurable signals, such as electrical currents or discernible color changes. Among the aforementioned methods, the colorimetric method, which detects the concentration of corresponding biochemical substances based on the color change caused by biochemical reactions, is more commonly utilized. Chen et al. proposed the utilization of a 3D printed flexible wearable health monitor for blood glucose monitoring in sweat (Fig. 7a)203. This monitor features a unique one-step continuous fabrication process that integrates self-supporting microfluidic channels and a novel single-atom catalyst-based bioassay. By employing direct ink writing technology, the researchers printed microfluidic devices with self-supporting structures, thereby mitigating the contamination and sweat evaporation issues associated with conventional sampling methods. Additionally, the need for sacrificial support materials was eliminated, and the integration of bioanalysis into the printing process through a pick-and-place strategy enhanced productivity. The advent of single-atom catalysts and their application in colorimetric bioassays has significantly improved the sensitivity and accuracy of monitoring. However, the wearable sweat detection system still faces challenges in the real-time collection and detection of fresh sweat. To address this challenge, Niu et al. designed a fully elastic wearable electrochemical sweat detection system (Fig. 7b)204. This system comprises a microfluidic chip for sweat collection, a multiparameter electrochemical sensor, a microheater, and an elastic circuit board for sweat detection. The microfluidic chip adopts a distinctive tree-like bionic design that significantly enhances the collection and discharge efficiency of fresh sweat, enabling the electrochemical sensor to perform real-time detection. The sensor can accurately and sensitively measure a range of parameters, including sodium ions, potassium ions, lactate, and glucose. The electronic system is constructed on a flexible circuit board that aligns seamlessly with the skin’s texture, ensuring optimal comfort during wear and enabling the collection, processing, and wireless transmission of multi-channel data. While electrochemical detection and colorimetric methods offer distinct advantages, the former is limited by non-ideal form factors, and the latter is hindered by semi-quantitative operation and a limited range of measurable biomarkers. Bandodkar et al. introduced an alternative approach by proposing a battery-free wireless electronic sensing platform inspired by biofuel cells (Fig. 7c)205. The platform seamlessly integrates a chrono-microfluidic system with an embedded colorimetric analysis, facilitating electrochemical sensing in a regimen where the target analyte autonomously elicits an electrical signal that scales directly with its concentration. This innovation obviates the requirement for a continuous potential meter, thereby optimizing the sensor’s design in terms of weight, cost, and size.

a 3D printed wearable glucose sensor203. b Flexible electrochemical sweat detection system integrated a microfluidic chip204. c Battery-free wireless electronic sensing platform inspired by biofuel cells205. d Schematic image of the mouthguard biosensor to custom-fit the patient’s dentition209. e Wearing of the mouthguard sensor and photograph of the fabricated MG sensor integrated with a wireless module and battery210. f Schematic illustration of smart contact lens for diabetes monitoring. The structure and glucose sensing mechanism of bimetallic nanocatalysts in nanoporous hydrogels213. g Schematic illustration for in vivo diabetic diagnosis and therapy of the smart contact lens214. h Working principle of microwave-based blood glucose219. i The antenna slots and the filter, inspired by the anatomy of the veins and arteries of the hand and the arm, respectively. The proposed sensors operate at UHF and microwave bands, providing sufficient EM wave penetration depth to target veins and arteries, along with a wide characterization range220.

Saliva glucose monitoring emerges as a non-invasive and highly convenient alternative to blood glucose monitoring, necessitating merely a straightforward stimulation of the oral cavity to elicit saliva, followed by its collection using a specialized apparatus206,207. In contrast, the glucose concentration in sweat is susceptible to numerous confounding factors, potentially compromising the fidelity of measurement208. Arakawa et al. developed and rigorously tested a saliva-based biosensor designed specifically for monitoring blood glucose levels, which can be adequately energized within the oral cavity (Fig. 7d)209. The biosensor is composed of a mouthguard holder that incorporates Pt and Ag/AgCl electrodes, along with an enzyme membrane. This configuration enables the effective monitoring of glucose concentrations in saliva. In vitro performance assessments demonstrated a strong correlation between the output current and glucose concentration. However, the presence of certain salivary constituents, notably ascorbic acid and uric acid, introduced significant interference, thereby compromising the accuracy of glucose concentration measurements. Consequently, Arakawa and colleagues have dedicated their efforts to developing an enhanced version of the mouthguard glucose sensor. By coating the electrode with CA (Wako) as an anti-interference membrane, their aim is to achieve precise quantification of glucose concentrations within the range of 1.75 to 10,000 μmol/L (Fig. 7e)210.

Tear glucose monitoring distinguishes itself from sweat and saliva approaches by virtue of its more direct and consistent physiological linkage. Certain constituents of the blood are transported across the blood-tear barrier into the tear fluid, enabling the metabolites present within the latter to exhibit a more intimate correlation with blood glucose concentrations211. This physiological process facilitates the attainment of more precise blood glucose measurements. Furthermore, the composition of tears is relatively shielded from external environmental perturbations, making it an ideal solution for blood glucose mornitoring212. Kim et al. overcame these hurdles by achieving robust long-term continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in diabetic rabbits through the use of a bimetallic nanocatalyst immobilized within a nanoporous hydrogel incorporated into a smart contact lens (Fig. 7f)213. This ocular glucose sensor exhibited remarkable characteristics, including high sensitivity, rapid response time, low detection limit, and minimal hysteresis. Additionally, Keum et al. develop smart contact lenses tailored for sustained glucose monitoring and treatment of diabetic retinopathy (Fig. 7g)214. The reference electrode coated with Ag/AgCl increased the accuracy of amperometric electrochemical glucose sensor in the fluidic environment by providing a constant voltage to the working electrode during the glucose measurement. Constructed using biocompatible polymers, these lenses integrate ultra-thin flexible circuits and a microcontroller chip, enabling advanced functionalities such as real-time electrochemical biosensing, on-demand controlled drug delivery, wireless power management, and data communication capabilities.

Beyond the realm of traditional body fluid analysis, microwave-based blood glucose monitoring has emerged as a noteworthy endeavor215. A change in glucose concentration results in a corresponding alteration in the microwave reflection coefficient, microwave technology boasts a substantial penetration depth, enabling it to traverse biological tissues and procure blood glucose data that more accurately reflect physiological states216. This methodology is notably resilient to perturbations from extraneous blood constituents within the measurement vicinity, thereby underpinning its heightened precision in assessments217. Furthermore, microwave-facilitated glucose detection is user-friendly, characterized by swift detection timelines, and capable of furnishing real-time glucose insights. These attributes render it an exceptional fit for patient cohorts necessitating frequent glucose monitoring218. Baghelani et al. developed a highly sensitive, non-invasive sensor designed for real-time monitoring of blood glucose in interstitial fluids (Fig. 7h)219. The sensor is capable of detecting glucose with an accuracy of approximately 38 mM/l over the physiological range of glucose concentration, exhibiting a resonance shift of 38 kHz. Notably, this sensor eliminates the need for power consumption and demonstrates the capability to accurately detect glucose at physiological concentrations. Meanwhile, Hanna et al. also presented a highly sensitive wearable multi-sensor system for non-invasive continuous glucose monitoring (Fig. 7i)220. The innovative use of a distinctive vasculature system and anatomy-inspired tunable electromagnetic topology enables precise and real-time responses from the sensors. This system exhibits a strong correlation (above 0.9) between blood glucose levels and physical parameters, without any discernible time lag.

Other cardiovascular-related biochemical sensors

The assessment of cardiovascular health is a multifaceted and complex endeavor that goes beyond the limitations of a single biochemical indicator. Indeed, to attain a more holistic comprehension of the cardiovascular system’s overall condition, physicians must meticulously consider an array of biochemical markers, encompassing cholesterol, lactate, cortisol, uric acid, and inflammatory factors. Each of these markers holds a pivotal role in unveiling the intricate status of cardiovascular health221,222,223,224. Collectively, they intertwine to form a complex network that mirrors the comprehensive health of the cardiovascular system and offers indispensable insights for clinical diagnosis and therapeutic interventions.

Cholesterol concentrations, particularly those of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, serve as direct indicators of the propensity for atherosclerosis225,226,227. The deposition of LDL cholesterol fosters the development of plaques along arterial walls, whereas HDL cholesterol performs a protective role by facilitating the removal of these deposits, thereby mitigating the hazard of heart disease228,229. Likewise, perturbations in lactate metabolism, a pivotal energy substrate for the heart, can compromise both the energetic provisioning and structural integrity of the myocardium, ultimately impacting cardiovascular well-being230,231. Moreover, lactylation is recognized as a crucial aspect in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease, underscoring its significance in this context232. Arwani et al. devised an innovative sensor design capable of in situ detection of solid lactate and solid cholesterol prevalent in human skin (Fig. 8a)233. This novel sensing modality utilizes an ionic–electronic bilayer hydrogel structure to form a solvation–diffusion layer. The ionic conductive hydrogel facilitates SEB solvation and diffusion towards the ECH interface for enzyme-catalyzed redox reactions, with electrons captured by ECH readable by a flexible circuit board, correlated to SEB density. An integrated circuit with a Bluetooth module wirelessly transmits the data to a user interface. This design successfully achieved continuous monitoring of both water-soluble analytes (e.g., solid lactates) and water-insoluble analytes (e.g., solid cholesterol), demonstrating ultra-low detection limits of 0.51 nmol/cm−2 for the latter. Furthermore, the design incorporated a bilayered hydrogel-electrochemical interface, which effectively mitigated motion artifacts by a factor of three compared to conventional liquid sensing electrochemical interfaces.

a Photograph of the cholesterol and lactic acid sensor placed on human skin233. b Illustration of the laser direct-written graphene sensor for cortisol. The details show the schematic of the electrochemical detection of cortisol in human sweat and representation of the affinity-based electrochemical cortisol sensor construction and sensing strategy237. c Wearable surface-enhanced Raman scattering chip for noninvasive monitoring of uric acid in sweat243. d Flexible Nafion/aptamer-modified MoS2 inflammatory factor sensor for the real-time assessment of the immune response’s vigor through the detection of TNF-α concentrations in sweat246.

Cortisol, a hormone emanated by the adrenal cortex, encompasses a diverse array of physiological roles, notably encompassing the modulation of immune responsiveness and metabolic processes ref. 234,235. Sustained periods of heightened cortisol levels may culminate in myocardial tissue injury ref. 236. Rodríguez et al. presented a highly sensitive, selective, and miniaturized wearable medical device based on a laser direct-written graphene sensor (Fig. 8b) ref. 237. This device facilitated non-invasive monitoring of stress hormones (e.g., cortisol) and demonstrated a strong correlation between sweat and circulating cortisol levels. Notably, the device can rapidly identified alterations in sweat cortisol levels in response to acute stress stimuli and, for the first time, characterized the circadian cycle and stress response profile of sweat cortisol, further validating the potential of this wearable health sensing system for dynamic stress monitoring.