Abstract

Early detection of SARS-CoV-2 is critical for preventing transmission. We developed a nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dot (nGQD)-based SPR biosensor to improve sensitivity and stability. nGQDs, synthesized from citric acid and urea, enhanced biomolecular binding and reduced non-specific adsorption. The nGQDs improved biomolecular binding through nitrogen functional groups, reduced non-specific adsorption, and enhanced assay performance in real-time kinetic and affinity analyses. The nGQD-based SPR chip successfully detected the RBD of the S1 subunit of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, with a detection limit of 0.01 pg/mL in both PBS and 10% plasma. Compared to conventional methods, the nGQD-based chip showed superior sensitivity, enabling detection of low viral loads and providing valuable molecular interaction data, useful for monitoring mutations that affect infectivity. This technology supports early diagnosis, reduces false positives, and offers a promising tool for screening, outbreak control, and variant surveillance, meeting urgent needs in pandemic preparedness and public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak was caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which was first identified in December 2019 and remains a significant public health concern1,2,3. The rapid spread of the virus prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare COVID-19 a global pandemic in March 20204. A key factor in the widespread transmission was subsequently shown to be mutations in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, which increased its transmissibility and allowed strains to quickly emerge and spread1,2,3. On May 5, 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared an end to the global public health emergency caused by the COVID-19 pandemic; however, this does not signify that the pandemic itself has been eradicated or has come to an end5. The results suggested that although asymptomatic individuals generally have lower viral loads, they still have the potential to spread the virus6. Furthermore, risk factors and SARS-CoV-2 genomic features were distributed across all clusters, suggesting that host comorbidities and viral genotypes are not confined to specific clinical characteristics. Supporting this, a serological study reported that ~76% of individuals with SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were asymptomatic, underscoring the substantial role of asymptomatic carriers in the spread of COVID-197. These findings highlight the urgent need for highly sensitive diagnostic technologies capable of detecting low viral loads and enabling early identification. Such tools are essential for isolating infected individuals promptly and preventing silent transmission within the community. Coronavirus-related studies have indicated virus particle diameters ranging from ~60–140 nm, and also that the virus has a very unique spike protein, about 9–12 nm. It has been demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 uses receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2)3,8,9, and that virus cell entry requires TMPRSS2 to cut the virus S1/S2 furin cleavage site in S protein and fuse the virus with the host cell membrane10,11. The ACE2 receptor, which SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter cells, is found throughout the human body, including in the lungs, heart, kidneys, liver, thyroid, adipose tissue, blood vessels, pharynx, trachea, brain, intestines, and various biological systems12,13,14,15,16. Consequently, viral components can be present in numerous body fluids including nasal mucus, saliva, sputum, tears, blood, urine, feces, cerebrospinal fluid, semen, and breast milk17,18,19,20. Despite this widespread distribution, current evidence does not indicate a direct infection link between COVID-19 in pregnant women and the potential for intrauterine vertical transmission from mother to fetus21.

Considering the widespread distribution and transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2, early detection is essential. Currently, the WHO supports the use of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), lateral flow assay (LFA), and next-generation sequencing (NGS) as the primary clinical diagnostic tools for SARS-CoV-2. Assays for viruses in serum, body fluids, urine, saliva, and other samples use methods such as immune response detection and nucleic acid amplification to measure viral concentrations and evaluate the presence of viral infections. RT-PCR offers early detection with high sensitivity and specificity; however, its amplification process is time-consuming (requiring 4–6 h) and costly. In comparison, LFA for detecting the N protein (antigen) and antibodies against the N and S proteins (IgG/IgM) is a rapid screening method. Rapid antigen tests can detect SARS-CoV-2 as early as 14 days after infection. However, LFAs often suffer from lower sensitivity and specificity. The performance of traditional ELISA tests, which can detect antigens and antibodies, falls between that of RT-PCR and LFAs in terms of efficacy. These methods are used by health authorities worldwide for COVID-19 detection. Furthermore, NGS plays a crucial role in identifying virus strains and tracing their lineage, serving as a vital tool for virus sequence analysis. Compared with other SARS-CoV-2 detection technologies such as reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP)22,23,24,25,26, field-effect transistor-based biosensors27,28, electrochemical-based biosensors29,30,31, Raman-based biosensors32,33,34, and colloidal gold-based lateral flow (AuNPs-LFA) biosensors35,36,37, SPR-based biosensors offer unique advantages38,39,40. Lateral flow-based RNA hybrid capture fluorescence immunoassays (HC-FIA) have been reported to have a limit of detection (LOD) of 1000 TU ml−1 35. In addition, ACE2 fluorescence lateral flow-based SARS-CoV-2 spike 1 antigen assays have been reported to have a LOD of 1.86 × 105 copies/mL36, compared to 0.65 ng/mL (95% CI of 0.53–0.77 ng/mL) for fluorescence lateral flow-based spike (IgM and IgG) protein assays37, and 1 ng/mL for electrochemical-based biosensors for detecting SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgM29. However, these assay methods do not evaluate the binding and affinity between molecules, which limits their effectiveness in detecting mutations in viral strains and assessing infectivity. In addition, the integration of electrochemical41 and transistor-based42,43 sensing technologies with graphene materials enables the detection of aptamer–protein interactions and nucleic acids, as well as the analysis of their binding kinetics. A graphene-based electrochemical biosensor demonstrated ultra-sensitive detection of unamplified SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acids, with a detection limit as low as 0.1 copies/μL41. A wearable bioelectronic mask equipped with aptamer-functionalized ion-gated transistors enabled the detection of viral proteins in trace liquid (0.3 μL) and gaseous samples (0.1 fg/mL)42.

In recent years, graphene quantum dots (GQDs) have become highly promising materials for enhancing the performance of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors due to their unique optical, electronic, and surface characteristics. Their strong and tunable photoluminescence enables effective signal amplification, while their high surface-to-volume ratio promotes efficient biomolecule immobilization, thereby improving sensitivity44. GQDs also offer excellent biocompatibility and stability in biological environments, making them ideal for biosensing applications45. The presence of abundant functional groups and π–π stacking interactions allows easy chemical modification, facilitating their integration with capture probes such as DNA or antibodies46. Moreover, their high electron mobility enhances plasmon–exciton coupling, further strengthening SPR signals. Acting as plasmonic enhancers or intermediate layers, GQDs amplify local refractive index changes at the sensor surface44,45,46.

In this study, we developed novel nitrogen-doped quantum dot (nGQD)-based surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensor technology to advance existing blood detection methods. We hypothesized that such an nGQD-based SPR chip could enable rapid and accurate virus detection in plasma and offer numerous advantages. For example, a viral blood test can reduce infection risk from oral droplets, minimize respiratory contact, and provide a safer option for patients and healthcare providers by decreasing airborne transmission risks. In addition, we hypothesized that this technology would be able to enhance detection sensitivity, reduce non-specific molecular contamination, and facilitate the detection of molecular affinity of mutant virus strains. These improvements are crucial for analyzing the interactions between characteristic viral proteins and receptor proteins, enabling effective predictions of viral infection and transmissibility. Our results showed that the nGQD-based SPR chip could effectively evaluate the selectivity and interaction forces of the S protein, and thereby aid in the evaluation of antibody-escape mutations. Furthermore, our findings provide important information for the development of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, as well as detection methods and disease assessment based on the spike glycoprotein.

Results

Synthesis and optical properties of the nGQD nanocomposites

Nitrogen was selected as the primary dopant due to its atomic size, which is similar to that of the host atoms, and the unique optoelectronic properties of nitrogen-doped graphene. The presence of five valence electrons in nitrogen significantly alters the PL properties of the doped material, making it a particularly effective choice for this purpose. Structural analyses of the nGQD nanocomposites were conducted using HRTEM microscopy. Before characterization, nGQD solution (10 μL) was diluted and uniformly and densely dispersed on a 400 mesh size carbon-coated copper grid and dried. Figure 1(a), (b) show HRTEM images of the nGQD nanocomposites, synthesized through carbonization. This process involved polymerizing CA and UR in a 2:1 ratio, leading to the formation of a crystalline structure. The resulting nGQD nanocomposites had diameters ranging from 3 to 10 nm. In addition, the average particle size, measured by DLS using Zetasizer Nano ZS was ~5.86 nm, with a zeta potential of −20 mV (Supplementary Fig. 1). These HRTEM results confirmed the successful synthesis of nGQD nanocomposites via hydrothermal reaction. Under hydrothermal conditions, CA and UR reacted to form citrate amide. This reaction facilitated dehydration and deamination among the carboxyl, hydroxyl, and amino groups of intermolecular compounds47. Moreover, by adjusting the CA to UR ratio, the self-assembly of amine groups on the carbide surface could be enhanced, leading to the formation of a nanosheet structure. HRTEM images revealed localized lattice fringes of the nGQDs, with an in-plane lattice spacing of about 0.24 nm (Fig. 1(b)). This spacing could be attributed to the (1120) lattice direction of the nGQD nanocomposites48.

a TEM image of nGQDs. b HRTEM image showing localized lattice fringes of nGQDs. c Comparison of SPR reflectivity curves obtained with a conventional SPR (bare Au) chip and different CA:UR ratios of nGQD-based SPR chips. Inset: Photograph of the bare Au and nGQD-based SPR chips. d UV-Vis absorption spectra of nGQD nanocomposites in different CA:UR ratios. e PL spectra under excitation at 405 nm in different CA:UR ratios. f PL spectra of the nGQDs under different synthesis times showing shifts in fluorescence.

To conduct SPR measurements, nGQD nanocomposites were applied as a coating on Au film to create an SPR sensing chip. Both the bare Au film and nGQD-based SPR chips were measured in air as the medium. The optical parameters of these SPR chips were evaluated under specific conditions: an incident angle scanning range from 32 to 44°, with a resolution of 0.02°, and operation using a 690 nm wavelength laser diode. A significant difference in resonance angles between the measured SPR signals was evident, demonstrating the detection capability, as shown in Fig. 1(c). This figure also compares the SPR reflectance curves for the nGQD-based SPR chips with those of the conventional Au chips. The SPR angles for the bare Au, Au/Cys, Au/Cys/nGQD (1:1), Au/Cys/nGQD (1:2), and Au/Cys/nGQD (2:1) chips were 34.92°, 36.15°, 36.21°, 36.56°, and 36.62°, respectively. The results indicated that increasing the mixed concentration ratio of CA and UR led to a shift in the SPR angle towards larger values. This shift could be attributed to the larger self-assembly of CA amide into carbon crystal grains of the nGQD nanocomposites. The inset in Fig. 1(c) shows both the bare Au and nGQD-based SPR chips (with nGQDs dried on the Au substrate), confirming the successful adsorption of nGQDs on the Au/Cys film surface. These findings suggested that the synthesized nGQD nanocomposites had a lattice orientation parallel to the surface and unique plasmon properties.

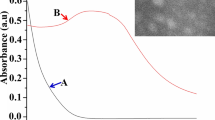

Figure 1(d) presents the UV-Vis absorption spectra of the nGQD nanocomposites in aqueous solutions at different CA:UR ratios. The hydrothermal synthesis conditions were a reaction time of 90 min and a temperature of 180 °C. The absorption spectra featured a shoulder π–π* absorption band at 237 nm and a distinct n–π* absorption band at 340 nm in the aqueous nGQD solution contained in a cuvette. The observed peak at 237 nm was attributed to the π–π* transition of graphitic sp2 domains (C=C), which was indicative of the graphene structure in the nGQDs. In addition, the absorption peak at around 340 nm, within the 300–400 nm range, corresponded to the n→π∗ transition. These were due to the presence of epoxide (C–O), peroxide (–O–O–), and pyrrolic N (C–N–C) structures49,50. These results clearly demonstrated that the π–π∗ and n–π∗ transitions were associated with highly localized π states, and that defects caused by surface oxidation created various trapped states51. The findings showed pronounced UV-Vis absorption spectra for the nGQD nanocomposites. Notably, the CA:UR ratio of 2:1 in the formation of nGQDs was associated with the highest absorption, suggesting that a higher concentration of CA was conducive to the molecular self-assembly of CA amide and subsequently the formation of GQDs.

Figure 1(e) shows the PL spectrum of the nGQD nanocomposites with different CA and UR mixing ratios. Two distinct characteristic peaks were observed at 440 nm and 480 nm. Notably, the CA:UR ratio of 2:1 had a higher fluorescence quantum yield (QY) of 26.5%. In comparison, the fluorescence quantum yields for CA:UR ratios of 1:1 and 1:2 were 22.4% and 23.5%, respectively. These findings suggested that synthesis of the nGQDs using high concentrations of CA modified the fluorescence properties of the nGQDs. A previous study reported that GQDs synthesized solely from citric acid exhibited a quantum yield (QY) of 9.0%. However, when urea was added to the citric acid precursor, the resulting GQDs showed a 40-fold increase in photoluminescence (PL) intensity. This enhancement was attributed to the role of urea in promoting PL, as confirmed by earlier literature52. The condensation product formed from urea and highly concentrated citric acid, known as citrate amide, shares structural features and oxygen-containing functional groups with GQDs, suggesting a common luminescence mechanism47. Conversely, an excessive amount of citric acid has been shown to reduce fluorescence QY. As illustrated in Fig. 1(a)–(e), the hydrothermal synthesis of nGQD nanocomposites was carried out with a reaction time of 90 min and temperature of 180 °C.

In addition, we varied the synthesis times to examine the PL characteristics of the nGQDs. Using a CA:UR concentration ratio of 2:1 at 180 °C, we polymerized the nGQD nanocomposites for 90, 180, 300, and 720 min, respectively. The resulting PL spectra of the nGQDs demonstrated shifts in fluorescence wavelength corresponding to the different synthesis durations (Fig. 1(f)). Specifically, the fluorescence wavelengths of the nGQD nanocomposites were recorded at 440, 490, 526, and 527 nm for synthesis times of 90, 180, 300, and 720 min, respectively. These results clearly indicated that the molecular structure of carbon was closely linked to the luminescent properties. Notably, as shown in Fig. 1(f), fluorescence of the nGQDs revealed that with synthesis times ranging from 300 to 720 min, the changes in wavelength exhibited a consistent pattern. The results obtained from nGQDs prepared at various reaction times indicated that the molecular structures contributing to the luminescence of nGQDs were aggregates or condensation products of CA amides. The findings demonstrated that extending the synthesis time did not further shift the wavelength towards the red spectrum. This indicated that the potential for further red-shift may have been limited due to the nature of the molecular structures, which were likely aggregates or condensation products47,48,50,53. These structures may reach a point of saturation or stability, beyond which no significant change in luminescence properties occurs. Taken together, the results indicated that nitrogen compounds in urea reacted with carbon surfaces, enhancing PL intensity during GQD formation by introducing nitrogen dopants, and thereby improving the optical properties and functionalization potential47,48,53.

In an attempt to visualize the structures of the nGQDs, XPS of the nGQD nanocomposites at CA:UR ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 2:1 were measured, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 2–4.

Further analysis of the C1s spectrum revealed that the proportions of C=C bonds in the carbon matrix for CA:UR ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 2:1 were 33.5%, 46.9%, and 38.5%, respectively, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 2(b), 3(b), and 4(b). In addition, the O1s spectrum indicated that the percentages of C=O bonds for the three ratios were 81.1%, 97.6%, and 73.2%, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 2(c), 3(c), and 4(c)). While the remaining bonds were roughly evenly distributed between C–N and N–O bonds, as confirmed by the N1s spectrum, the percentages of C-NH-C bonds at CA:UR ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 2:1 were 67.8%, 24.8%, and 81.1%, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 2(d), 3(d), and 4(d)). This was confirmed by the XPS spectra of the nGQD nanocomposites, which quantified the amounts of C, N, and O on the Au chips in the nGQDs, as shown in Figs. S2–S4. Fig. S3(d) shows that a CA:UR ratio of 2:1 resulted in a higher proportion of NH in the nGQDs, confirming that up to 81.1% of the nitrogen in the nGQDs was doped with C-NH-C. This high proportion could enhance the binding of -COOH groups in protein structures during sensing54,55,56. These results clearly demonstrated that nitrogen compounds had been successfully incorporated into the nGQD nanocomposites44,57,58.

To confirm the existence of nitrogen bonding in our nGQDs, the samples prepared with a reaction time of 90 min and different CA:UR ratios were analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows the FTIR spectra of the nGQD nanocomposites in attenuated total reflection (ATR) mode, analyzed to elucidate the properties of various O, C, N, H-containing species. These spectra were obtained to confirm the presence of surface functional groups on the nGQD nanocomposite samples. The FTIR spectra of the nGQD nanocomposites at CA:UR concentration ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 2:1 are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5(a)–(c), respectively.

In the presence of CA, the FTIR spectra of the prepared samples showed peaks at 1684 cm−1 and 1595 cm−1, providing evidence of amide bonding in the products. In addition, absorption bands around 3180 cm−1 and 3050 cm−1 represented N–H and O–H stretching vibrations, respectively. These functional groups enhanced the hydrophilicity and stability of the nGQDs in aqueous environments47,57. Supplementary Fig. 5(c) shows that increasing the CA:UR ratio to 2:1 enhanced the N–H content (1595, 1684, and 3180 cm−1). Consequently, this adjustment in the CA:UR ratio could improve the detection of protein molecules.

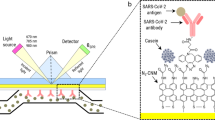

Immobilization and bonding analysis of SPR chip sensing probes

We used the nGQD nanocomposites successfully synthesized with a CA:UR ratio of 2:1 to develop a novel nGQD-based SPR chip. This chip was then used to detect interactions with the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S1-RBD) protein. Figure 2(a) illustrates the immobilization steps of the ligand probes (ACE2 and Anti-S1 protein) on the nGQD-based SPR chip in the flow channel of the BI-SPR system.

a The steps involved in the immobilization process of the Anti-S1 and ACE2 protein probes. b The immobilization binding of the ACE2 protein on the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip. c The immobilization binding of the Anti-S1 protein on the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip. d The immobilization binding of the ACE2 protein on the conventional SPR chip.

Figure 2(a) illustrates the immobilization process of ligand probes (ACE2 and Anti-S1 protein) on the surface of the nGQDs. Initially, EDC/NHS was injected at a flow rate of 60 µL/min to activate the –COOH groups on the surface of the nGQDs. In the microfluidic SPR system, a significant refractive index difference was observed as the high-concentration EDC/NHS activator reacted with the chip surface. Since EDC/NHS molecules are very small, their binding to the –COOH groups resulted in only a slight angular shift (about 9.5 m°) on the SPR time axis. A sensing probe (either ACE2 or Anti-S1 protein) was then introduced at a concentration of 10 µg/mL, facilitating the formation of a covalent bond between the -NH2 groups of the probe protein and the –COOH groups on the surface of the nGQDs. This immobilization step was conducted at a reduced flow rate of 10 µL/min to enhance the concentrations of ligand probes on the chip surface. Subsequently, BSA protein at a high concentration of 200 µg/mL was injected to block any remaining –COOH groups on the chip surface. After this, a high concentration of 1 M ethanolamine (EA) was introduced to deactivate any residual –COOH activity. Since EA molecules are very small, after reacting with the chip surface, the SPR exhibited a very small angular displacement (about 4 m°) on the SPR time axis. The purpose of using BSA and EA was to minimize non-specific binding in the assay. Finally, a regeneration step was carried out by injecting 50 mM NaOH, with the aim of removing unbonded and non-specifically bound molecules from the chip surface and return the SPR signal to the baseline of effective antibody immobilization.

The resulting data were fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model to evaluate the adsorption isotherm and determine the binding affinity between the nGQD surface and Anti-S1 or ACE2 protein probes (The analysis of SPR kinetics is provided in the Supplementary Information). The analysis of SPR kinetics (ka, kd, and KA) was performed by averaging the data from three measurements.

Figure 2(b) shows the SPR-time sensorgrams, which highlight the resonance angular shifts and binding molecular kinetics of the ACE2 protein immobilized on the surface of the nGQDs at varying concentrations (such as the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip). At an ACE2 concentration of 25 µg/mL, there was a significant shift in the SPR angle, reaching 74.82 millidegrees (m°) at a steady state (1000 sec). Conversely, at a lower concentration of 10 µg/mL, the SPR angle shift was smaller, at only 47.36 m°. In addition, the interaction analysis showed that the binding affinity, represented by the association constant (KA), was 4.79 × 107 M−1 at 25 µg/mL, whereas it increased to 2.66 × 108 M−1 at a concentration of 10 µg/mL. Figure 2(c) presents the SPR-time sensorgrams at a steady state (1000 sec) for different Anti-S1 protein concentrations immobilized on the surface of the nGQDs (such as the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip). The SPR angle shifts for Anti-S1 concentrations of 10 and 25 µg/mL were at 39.69 and 101.68 m°, respectively. The kinetic analysis showed that the KA values for concentrations of 10 and 25 µg/mL were 16.1 ×108 M−1 and 2.43 × 108 M−1, respectively.

We then compared the molecular binding rates of ACE2 probe immobilization on a conventional SPR (Au-MOA-based) chip and an nGQD-based SPR chip, following the same immobilization procedures. As depicted in Fig. 2(d), the SPR angular shifts caused by the injection of ACE2 protein at concentrations of 10 and 25 µg/mL on the conventional SPR chip were 26.03 and 42.38 m°, respectively. In addition, the affinities (KA) of molecular interaction kinetics for the conventional SPR chip at these concentrations were 2.64 × 108 M−1 and 4.14 × 108 M−1, respectively.

In further analysis of the immobilization of optimized protein probes (Anti-S1 or ACE2) on the chip surface, a comparison of the results in Fig. 2(b), (c), (d) revealed that a concentration of 10 µg/mL had the highest affinity among the three chip types. Notably, the nGQD-based SPR chip demonstrated a significantly higher binding rate than the conventional SPR chip. Among the tested configurations, the Anti-S1 protein at a concentration of 25 µg/mL on the nGQD-based SPR chip had the highest binding rate, with a maximum SPR angular shift of 101.68 m°. These findings highlighted that the nGQD-based SPR chip had high binding rate and affinity, particularly with the Anti-S1 protein. This enhanced performance could be attributed to the large molecular weight of the Anti-S1 protein subunit at ~160 kDa, which likely contributed to the larger angular shift and stronger affinity binding compared to the ACE2 protein, which has a molecular weight of 110 kDa.

Detection of S1-RBD protein and kinetic analysis with the nGQD-based SPR chip

For the detection of S1-RBD protein antigens in PBS buffer, we conducted experiments with a flow rate of 30 µL/min and evaluated the concentrations and kinetics of molecular interactions, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Analytes were serially diluted and injected for 160 s each. The resulting data were then fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model to analyze the adsorption isotherm and assess the binding affinity between the analytes and ligand probes. In SPR-time sensorgram equilibrium angle (θeq) analysis, the SPR signal equilibrium time (Teq) was established at 600 s. The affinity and kinetic constants were determined using Biosensing Instrument software (Biosensing Instrument) with an appropriate binding model54,55,59.

a Analysis of interactions between Anti-S1 and S1-RBD protein using the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip. b Analysis of interactions between ACE2 and S1-RBD protein using the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip. c Analysis of interactions between Anti-S1 and S1-RBD protein using a conventional Au-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip. d Analysis of interactions between ACE2 and S1-RBD protein using a conventional Au-based (ACE2) SPR chip.

The assay results for S1 antigens using an nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip immobilized with Anti-S1 emphasizing concentration and kinetic analyses are shown in Fig. 3(a). The SPR-time sensorgrams show equilibrium angles (θeq) at steady-state for various concentrations of S1-RBD protein used in the binding assay. The observed SPR angle shifts for S1-RBD protein concentrations of 0.01 pg/mL, 0.1 pg/mL, 1 pg/mL, 10 pg/mL, 100 pg/mL, 1 ng/mL, 10 ng/mL, 100 ng/mL, 1 µg/mL, and 5 µg/mL were 1.70, 2.77, 3.86, 4.85, 6.92, 9.82, 12.25, 15.47, 20.37, and 31.45 m°, respectively. In the kinetic analysis of the interactions between Anti-S1 and S1-RBD proteins on the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip, the affinity binding constant (KA) was 4.84 × 109 M−1, the association rate constant (ka) was 9.2 × 106 M−1s−1, and the dissociation rate constant (kd) was 19 × 10−4 s−1.

Figure 3(b) shows the results of the assay of S1-RBD antigens on an nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip that had been immobilized with ACE2. This figure details both the concentration and kinetic analyses of interactions between S1-RBD antigens and the ACE2 protein ligand. The SPR-time sensorgrams show the equilibrium angles (θeq) across a range of S1-RBD protein concentrations. Specifically, the SPR angle shifts at concentrations of 0.1 pg/mL, 1 pg/mL, 10 pg/mL, 100 pg/mL, 1 ng/mL, 10 ng/mL, 100 ng/mL, 1 µg/mL, and 5 µg/mL were 0.37, 1.29, 2.39, 3.99, 5.84, 8.17, 9.29, 12.35, and 20.58 m°, respectively. In the kinetic analysis of interactions between ACE2 and S1-RBD protein on the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip, the affinity binding constant (KA) was 1.43 × 109 M−1, the association rate constant (ka) was 3.76 × 105 M−1s−1, and the dissociation rate constant (kd) was 2.63 × 10−4 s−1.

Figure 3(c) shows the SPR-time sensorgrams of a conventional Au-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip for the assay of S1-RBD protein. The results showed that the equilibrium angles (θeq) for S1-RBD protein concentrations of 0.1 pg/mL, 1 pg/mL, 10 pg/mL, 100 pg/mL, 1 ng/mL, 10 ng/mL, 100 ng/mL, 1 µg/mL, and 5 µg/mL were 0.39, 0.89, 2.54, 5.26, 6.74, 8.78, 12.84, 20.43, and 27.17 m°, respectively. Kinetic analysis of the conventional SPR chip revealed an affinity binding constant (KA) of 4.42 × 109 M−1, an association rate constant (ka) of 4.13 × 105 M−1 s−1, and a dissociation rate constant (kd) of 9.34 × 10−4 s−1.

Figure 3(d) shows the SPR-time sensorgrams of a conventional Au-based (ACE2) SPR chip for the assay of S1-RBD antigens. The results showed that the equilibrium angles (θeq) for S1-RBD protein concentrations of 0.1 pg/mL, 1 pg/mL, 10 pg/mL, 100 pg/mL, 1 ng/mL, 10 ng/mL, 100 ng/mL, 1 µg/mL, and 5 µg/mL were 1.83, 2.76, 3.86, 5.11, 5.82, 6.43, 9.79, 14.11, and 17.68 m°, respectively. Kinetic analysis of the conventional SPR chip revealed an affinity binding constant (KA) of 1.593 × 109 M−1, an association rate constant (ka) of 2.9 × 105 M−1 s−1, and a dissociation rate constant (kd) of 1.82 × 10−4 s−1.

Furthermore, the conventional SPR chips (Au-based (ACE2)) had comparable affinity to the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip, at about 1× 109 M−1. However, the SPR angle shift during the ACE2-S1 binding reaction on the conventional SPR chip showed only a minimal change. In contrast, the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip demonstrated a significantly higher affinity, with its affinity binding constant (KA) being enhanced by approximately 3.0-fold compared to the conventional SPR chip. At a concentration of 5 µg/mL, the SPR angle shift of the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip relative to the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip, the conventional Au-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip, and the conventional Au-based (ACE2) SPR chip was in a ratio of approximately 1.8:1.2:1.5:1.

Previous studies have reported that SARS-CoV-2 increased the binding rate of ACE2 to a value of (ka) 7.55 × 103 M–1 s–1, and that enhanced ACE2 enzymatic activity resulted from binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike S1-RBD domain8,60,61. These findings underscore the potential for SARS-CoV-2 infection to increase ACE2 activity, which may play a role in the cardiovascular symptoms seen in COVID-19 patients. This observation aligns with the outcomes of our research. The KA values for the interactions between Anti-S1 with S1-RBD and ACE2 with S1-RBD on the nGQD-based SPR chip demonstrated a significant difference, with a 3.4-fold increase in the apparent binding affinity. These results indicated that the binding affinity, with KA values in the range of approximately 1 × 109 M−1, could reflect interaction forces typically seen in immune reactions (antigen-antibody interactions), denoting high affinity8,9,60. These findings suggest that the specific chemical interaction between the S1-RBD protein and ACE2 was highly interactive, and comparable to the immune response between S1-RBD and Anti-S1.

Regarding the sensitivity and linearity analyses, Fig. 4(a), (b) show the specific SPR responses corresponding to various concentrations of the S1-RBD protein in PBS buffer. The analysis revealed a linear relationship between the S1-RBD protein concentration and specific SPR angle shift, measured at 600 s at the end of the dissociation phase. Notably, the calibration curves exhibited two distinct linear regions with different slopes, corresponding to low (0.01–100 pg/mL) and high (100 pg/mL–1 µg/mL) concentration ranges, each demonstrating strong log-linear regression and high linearity within its respective dynamic range.

Sensitivity and linear regression analyses were performed across four different SPR chips at two concentration ranges: a low concentrations (0.01–100 pg/mL) and b high concentrations (100 pg/mL–1 µg/mL). In additionally, calibration curves of the nGQD-based SPR sensor under interference conditions demonstrated similar linear trends at (c) low and (d) high concentration ranges. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from four independent experiments.

The linear regression equations for the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip were y = 4.02 + 1.25x with a correlation coefficient (R²) of 0.97 for low concentration, and y = -0.05 + 3.25x with an R² of 0.98 for high concentration. For the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip, the linear regression equations were y = 1.41 + 1.19x with an R² of 0.98 for low concentration, and y = −0.13 + 2.02x with an R² of 0.98 for high concentration. In comparison, the conventional Au-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip was described by the equations y = 1.46 + 1.62x with an R² of 0.92 for low concentration, and y = -3.76 + 3.64x with an R² of 0.89 for high concentration. For the conventional Au-based (ACE2) SPR chip, the linear regression equations were y = 2.83 + 1.11x with an R² of 0.99 for low concentration, and y = −0.43 + 2.18x with an R² of 0.86 for high concentration. These equations clearly demonstrated that the nGQD-based chips had significantly higher sensitivity compared to the conventional SPR chip.

We evaluated another key sensitivity characteristic across the four chips: the slope of the SPR response (dθ/dc), in which a steeper slope indicates higher sensitivity. Our results revealed that the slopes for the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip, nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip, conventional Au-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip, conventional Au-based (ACE2) SPR chip were 3.25, 2.02, 3.64, and 2.18, respectively. Notably, the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip demonstrated a significantly enhanced sensitivity, being 1.6-fold more sensitive than the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip. The nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip showed the ability to assay S1-RBD antigens with a detection limit (LOD) as low as 0.01 pg/mL. Both nGQD-based (ACE2) and conventional SPR chips showed a LOD of only 0.1 pg/mL for S1-RBD antigens. All of the experiments for SPR analyses were performed in triplicate and repeated four times. The data points, representing the mean ± standard deviation, are based on three consecutive injections, consistent with the methodologies illustrated in Fig. 3(a)–(d).

Detection of S1-RBD protein in selectivity assays

In the selective assay, we individually added six different proteins (hCG, CA-199, Cyfra21-1, HAS, PAPP-A, and S1-RBD) at a concentration of 100 ng/mL in PBS buffer and conducted the assay to evaluate the performance of the nGQD-based SPR chips. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 6(a), we injected hCG, CA-199, Crfra21-1, HAS, PAPP-A, and S1-RBD proteins at a flow rate of 30 µL/min onto the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip, resulting in SPR angle shifts of 1.31, 0.62, 1.19, 1.01, 1.07, and 14.81 m°, respectively. In addition, the average SPR angle shifts obtained by injecting hCG, CA-199, Crfra21-1, HAS, PAPP-A, and S1-RBD proteins at a flow rate of 30 µL/min onto the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip were 1.62, 1.89, 2.05, 1.83, 0.94, and 9.46 m°, respectively. These results clearly showed that the nGQD-based SPR chips had exceptional selectivity, and that the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip had even higher specificity.

We also conducted tests with the S1-RBD protein in spiked human plasma at various concentrations (0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%) (No. P9523, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) to assess the specificity and potential interference in the detection, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 6(b). The injection volume was 200 μL with a mixing ratio of 1:1, resulting in a final solution comprising S1-RBD protein (100 ng/mL) and various percentages of human plasma concentration. The average SPR angle shifts with the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) and nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chips were 14.81 m° and 9.46 m° (spiked 0% plasma), 16.36 m° and 10.89 m° (spiked 5% plasma), 16.82 m° and 15.61 m° (spiked 10% plasma), 18.21 m° and 20.05 m° (spiked 15% plasma), and 19.19 m° and 21.25 m° (spiked 20% plasma), respectively.

We then analyzed differences in SPR angle shift ratio (△θ%, θplasma %/θplasma %) as characteristics of the binding interactions observed when the nGQD (Anti-S1) chip was exposed to solutions with 0% human plasma compared to solutions spiked with various concentrations of human plasma. The resulting differences in △θ% were: 4.93% (spiked 5% plasma), 13.57% (spiked 10% plasma), 22.96% (spiked 15% plasma), and 29.57% (spiked 20% plasma). In contrast, the △θ% values for the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip were 15.12% (spiked 5% plasma), 39.39% (spiked 10% plasma), 111.95% (spiked 15% plasma), and 124.63% (spiked 20% plasma). Greater angular signal drift was observed when plasma concentrations exceeded 10%. This effect is consistent with previous findings and may be attributed to interactions with other proteins in plasma that interfere with binding site occupancy or involve electrostatic forces. These results demonstrated that the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip maintained high specificity, even when spiked with 10% human plasma, as indicated by an angular displacement of less than 14%. In addition, Supplementary Fig. 6(b) shows that the angular changes in SPR with the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip remained relatively unaffected by the concentration of human plasma when compared to the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip, which exhibited relatively small SPR angular shifts. Moreover, the assay using the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip in spiked plasma samples showed excellent correlations.

The calibration plots in Fig. 4(c), (d) demonstrate the ability of the nGQD-based SPR chip to assay S1-RBD protein concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 1 µg/mL in two different settings: with five spiked proteins (hCG, CA-199, Cyfra21-1, HAS, PAPP-A), and in 10% spiked human plasma. Figure 4(c) shows the assay results for low concentrations of S1-RBD protein (0.01 pg/mL to 100 pg/mL), while Fig. 4(d) shows results for high concentrations of S1-RBD protein (100 pg/mL to 1 µg/mL). The solid lines represent fitted regression curves, demonstrating a linear range. Data points indicate the mean SPR angle ± standard deviation for four consecutive injections.

As shown in Fig. 4(c), when the concentration of S1-RBD protein increased from 0.01 to 100 pg/mL, the SPR angle response also increased, showing a good correlation. In buffer spiked with the five proteins, the regression equations of the calibration curves were y = 4.04 + 1.45x (R2 = 0.95) for the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip, and y = 1.69 + 1.43x (R2 = 0.96) for the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip, where x is the S1-RBD protein concentration and y is the SPR angle (θ). In spiked plasma (10%) buffer, the regression equations of the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip and nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip were y = 4.15 + 1.73x (R2 = 0.98) and y = 3.95 + 1.78x (R2 = 0.95), respectively.

Figure 4(d) shows the S1-RBD protein assay results with a concentration from 100 pg/mL to 1 µg/mL. The calibration plots for the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) and nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chips were generated from optimized analytical performance at different concentrations. The SPR responses to the corresponding regression equations of the S1-RBD protein assay in spiked buffer of the five proteins were y = - 0.25 + 3.61x (R2 = 0.96) and y = −0.55 + 2.38x (R2 = 0.97) for the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) chip and nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip, respectively. Furthermore, the regression equations of the S1-RBD protein assay in spiked plasma (10%) buffer were y = −1.24 + 4.01x (R2 = 0.94) and y = −2.29 + 3.81x (R2 = 0.86), respectively.

These results showed that the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip remained largely unaffected when subjected to spiked samples containing the five different proteins and plasma as potential interfering substances. This suggested that the specificity of the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip was superior to that of the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip. Notably, a highly significant linear relationship between the concentration of S1-RBD protein and SPR angle shift in the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip was observed across various test solutions. This showed that the nGQD-based SPR chip could selectively detect SARS-related coronavirus proteins in complex media. Furthermore, when testing S1-RBD protein antigens in spiked human plasma samples, the results showed excellent correlations. The calibration curves showed superior linearity and sensitivity in two distinct ranges for the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip compared to the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip.

Discussion

We further compared the performance between commercially available S1-RBD detection chips, a lateral flow assay (LFA)-based rapid S1-RBD antigen test kit, and the nGQD-based SPR chips. The LFA-based rapid test kit (Fidelity Pharmaceutical Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Taiwan) demonstrated a sensitivity of 83.9% and specificity of 95.5%, with a LOD of 1.2 × 102 TCID 50/mL for the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The LFA infectious virus titer was determined by observing the viral infection of cultured cells using the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID 50) method.

Figure 5(a) illustrates the detection of S1-RBD antigen protein at various concentrations (0.05–100 ng/mL) using the LFA method. Different concentrations of S1-RBD protein were diluted with PBS buffer, and an injection volume of 200 μL of S1-RBD protein was introduced into the LFA device. After a 15 min incubation period, the LFA strip was photographed using a smartphone and analyzed using ImageJ software. The intensities of the control (C) and test (T) lines in the bar graph were transformed into peak histograms, as depicted in Fig. 5(b). The line intensities on the LFA strip were semi-quantified, and the intensities of the C and T lines were calculated using 8-bit grayscale analysis with ImageJ software.

a Images of experimental LFA test lines for various concentrations of S1-RBD protein at the control (C) and test (T) lines. b Comparison of experimental LFA test line profiles (black outline) measuring different concentrations of S1-RBD protein obtained from the LFA reader, for the C control line (top) and T test line (bottom) outlined in (a) above. c Quantitative intensity analysis of the LFA test line for S1-RBD in PBS buffer. d Quantitative intensity analysis of S1-RBD in spiked 10% plasma buffer. e Comparison between LFA test lines and the nGQD-based SPR chip for S1-RBD detection in spiked 20% plasma buffer. The values represent the mean ± standard deviation from five separate experiments.

Figure 5(c) shows the calculated values of the bar graph intensities of detecting S1-RBD protein in PBS buffer. The concentrations of S1-RBD protein were 0 (negative), 0.05, 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 ng/mL, respectively, and relative to the bar graph, the average intensities of the test (T) were 26, 29, 30, 40, 69, and 46, and the average intensities of the control (C) lines were 95, 83, 105, 132, 169, and 160. The LOD was determined to be 0.05 ng/mL based on the mean value of negative controls (0 ng/mL of S1-RBD protein) and the standard deviation.

In the spiked plasma experiment, 100 μL of S1-RBD protein was mixed with 10% plasma buffer in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio, and 200 μL of the mixed solution was loaded into the LFA device, as shown in Fig. 5(d). The concentrations of S1-RBD protein were 0 (negative), 0.05, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 ng/mL, respectively. Relative to the bar graph average intensities, the test (T) lines had values of 18, 47.5, 65, 64.5, 69, and 83, corresponding to the respective S1-RBD protein concentrations. Similarly, the control (C) lines had values of 130, 107, 191, 132.5, 149.5, and 137.5. It was evident that the addition of 10% plasma to the detection of S1-RBD protein led to stronger bar graph intensities of both the T and C lines, as depicted in Fig. 5(d). These results indicated that spiked plasma had an impact on the color development of the LFA bands, potentially causing errors in semi-quantitative results.

Furthermore, we increased the plasma doping concentration to 20% to assess the specificity of the detection chip. Figure 5(e) compares the performance of the LFA device and nGQD-based SPR chip in the presence of 20% plasma only and 100 ng/mL of S1-RBD protein in spiked 20% plasma. The results showed that the LFA device failed to produce a distinguishable color reaction for S1-RBD protein 100 ng/mL in 20% plasma, with the bar graph average intensities of the control (C) lines falling within the range of 58–35. This overlap in results with the 20% plasma only (the bar graph average intensities range of 45-13) sample indicated that the LFA device was not suitable for detecting S1-RBD in 20% plasma under these conditions. These results showed that the nGQD-based SPR chip had a unique detection ability to differentiate between 20% plasma only and S1-RBD protein spiked with 20% plasma. It could effectively detect S1-RBD protein (100 ng/mL) in complex plasma and cause displacement changes in the SPR reaction angle. Furthermore, the average angular displacements observed with different probes (ACE2 and Anti-S1) immobilized on the nGQD-based SPR chips were also significantly different. The nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip had an average angular shift of 16.82 m°, whereas the nGQD-based (ACE2) SPR chip had an average shift of 15.61 m°. These results emphasize the accuracy and sensitivity of the nGQD-based SPR chip in detecting S1-RBD protein concentrations, with the nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip achieving the highest detection rates.

Mutations of the SARS-CoV-2 virus have had a profound impact on human health and economic growth. There is an urgent need for effective diagnostic tools to halt the spread of the virus, such as rapid and precise assay methods. Given the rapid transmission of the virus, early-stage and asymptomatic testing is vital for controlling the epidemic. The main drawbacks of current traditional assay methods are low accuracy, complex sample preparation and data analysis, and long processing times. This study proposes the addition of urea during the synthesis of nGQDs to increase the content of NH groups, thereby enhancing the binding reaction with proteins and improving detection sensitivity. The key findings of this investigation were the excellent sensitivity and high affinity of the nGQD-based SPR chip.

The proposed nGQD-based SPR chip could be used to quickly and accurately detect viruses in plasma, reducing droplet infection risk and offering a safer, contact-free option. The nGQD-based (Anti-S1) SPR chip had 1.6-fold higher detection sensitivity and 3.4-fold higher binding affinity compared to a conventional SPR chip. The detected S1-RBD protein concentration exhibited a strong linear relationship across low (0.01 to 100 pg/mL) and high (100 pg/mL to 1 µg/mL) concentration ranges, with a linear equation of y = 4.02 + 1.25x (R² = 0.97) and y = −0.05 + 3.25x (R² = 0.98). The LOD for the virus in PBS buffer was 0.01 pg/mL. Experimental results demonstrated that the nGQD-based SPR chip had high selectivity and robust anti-interference (spiked human plasma 10%) capabilities in detection tests. The nGQD-based SPR chip demonstrated significantly higher specificity, accuracy, and sensitivity in detecting S1-RBD protein compared to LFA testing methods, and it was more commercially valuable. Through kinetic analysis of molecular interactions, this technology can allow for the early diagnosis of viral infections, detection of mutant strains, and also the capability to predict virus transmission efficiency. This will facilitate disease screening, infection risk reduction, as well as disease assessment and management. Virus mutations and evolution have caused large numbers of human diseases and deaths throughout history. Humans cannot immediately control or prevent large-scale disease outbreaks, however, they can be limited with the use of advanced detection technology. As such, the development of new technologies such as biosensors plays a crucial role, and we hope that novel biosensors such as those proposed in this article will have a meaningful impact on epidemic control in the future.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of aminated-graphene quantum dots

To develop the novel bioaffinity sensing material in this study, we synthesized nGQDs through a hydrothermal reaction. The method for creating this composite sensing material is depicted in Fig. 6(a). We used citric acid (C6O8H7, CA, Sigma-Aldrich Brand, Merck KGaA, Germany) and urea ((NH2)2CO, UR, Sigma-Aldrich Brand, Merck KGaA, Germany) to carry out the high-temperature hydrothermal reaction to polymerize the molecules47,48,53. In this experiment, CA at a concentration of 0.0042 mol/L and UR at 0.25 mol/L were mixed in 30 mL of deionized water. Three different concentrations were prepared with CA to UR ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 2:1, and these solution were evenly mixed at 25 °C. Subsequently, each mixed solution was placed into the sample tank of a high-pressure hydrothermal reactor. The heating temperature was set to 180 °C, and four distinct reaction times were used: 90, 180, 300, and 720 min. In the initial chemical reaction, CA and UR reacted to form citrate amide. Subsequently, under hydrothermal conditions, dehydration and deamination reactions occurred involving the carboxyl, hydroxyl, and amino groups of intermolecular compounds. Upon further heating, citric acid amide self-assembled, leading to the formation of aggregates comprising dimers or oligomers of nanostructures. Following an extended period of hydrothermal condensation, these aggregates gradually evolved, growing into quantum dots characterized by a nanosheet structure53. These conditions were used to ascertain the optimal synthesis procedure for nGQD nanocomposites. Following the reaction, the nGQD aqueous solution was cooled to finalize the synthesis of the nanocomposites. This method required only one step to prepare the nGQD nanocomposites with efficient luminescence characteristics and high bioaffinity.

a Synthetic nanocomposites were generated by reacting citric acid (CA) with urea (UR) to form nitrogen-doped graphene oxide quantum dots (nGQDs); b Modification of Au surface and immobilization of nGQD nanocomposites. c The immobilization of primary probe Anti-S1 (or ACE2) protein and immobilization BSA protein to block excess functional groups. d The structure of SARS-COV-2 virus and its mutated amino acid sites. e Detection and interaction analyses of S1 protein on the nGQD-based SPR chip. f Evaluation of the performance of the nGQD-based SPR chip using kinetic analysis of the affinity and binding efficiency of S1-RBD protein in a dual-channel system.

Characterization of nGQD nanocomposites

TEM images were taken using a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HR-TEM) on an FEI Tecnai G20 system (Hillsboro, OR, USA) to observe the morphology of nGQDs. Dynamic light scattering particle size and zeta potential were analyzed using a DLS Zetasizer Nano ZS system (Malvern Instruments Ltd, Cambridge, UK) to observe the size of the nGQDs and interface potential. The ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption spectrum was observed using a double-beam UV-vis spectrophotometer (U-2900, Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with a wavelength from 200 to 1100 nm at room temperature. Photoluminescence (PL) spectrum measurements were performed with a 40 mW diode laser (Tayhwa Technology Co., Ltd., Taiwan) at an excitation of 405 nm, and a high-resolution spectrometer (HR 2000+, Ocean Optics, Inc., USA) at two fixed incident angles (0° and 45°) at room temperature. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed using the facilities at the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC, Taiwan), and the FTIR spectra were analyzed (Beamline TLS 14A1 BM-IR Microscopy). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was also performed using the facilities at NSRRC to analyze the XPS spectra (Beamline TLS 24A1 BM-(WR-SGM)).

Preparation of nGQD-based SPR chips and antibody immobilization technology

Figure 6(b) illustrates the biosensor surface modification technique. We used 16-mercaptohexadecanoic acid (MHA, 10 mM, Sigma-Aldrich Brand, Merck KGaA, Germany) for 12 h to form Au-thiol self-assembled monolayers on BK7/Cr (2 nm)/Au (47 nm) chip structures. MHA contains both thiol (-SH) and carboxyl (-COOH) groups, which acted as connectors between the Au film and nGQDs. To enhance covalent bonding of -COOH with NH2, it was necessary to activate the carboxyl group. The activation of carboxyl was achieved using a solution of N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, 98%, Sigma-Aldrich Brand, Merck KGaA, Germany) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC, ≥98%, Sigma-Aldrich Brand, Merck KGaA, Germany)54,55,59,62,63.

The activator consisted of a mixture of 100 μL of 0.4 M EDC with 100 μL of 0.1 M NHS. Subsequently, we used a 0.5 mg/mL concentration of the nGQDs, prepared with CA and UR in a 1:1 (1:2 or 2:1) ratio, in a 2 h immobilization process. The -NH terminus of the nGQDs, derived from UR, could form a covalent bond with the -COOH end of the MHA linker. For the immobilization of protein probes on the nGQD-based SPR chip, we used specific proteins: SARS-CoV-2 spike S1 monoclonal antibody (recombinant rabbit SARS-CoV-2 spike S1 protein IgG antibody, Anti-S1, molecular weight of 160 kDa, MBS2563839, MyBioSource, Inc., CA, USA) and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protein (recombinant human ACE2, molecular weight of110 kDa, tags for human IgG1 Fc, EPB223966, Euprotein, NJ, USA). These proteins were immobilized on the Au chip to facilitate subsequent detection and analysis. The immobilization step was carried out in an SPR dual-channel instrument (BI-3000G SPR system, Biosensing Instrument Inc., Tempe, AZ, USA). During this step, a volume of 200 µL of protein probes (either Anti-S1 or ACE2) at a concentration of 10 µg/mL was injected, with a flow rate set to 10 µL/min. To minimize non-specific molecular interference, bovine serum albumin (BSA, CAS 9048-46-8, B4287, Sigma-Aldrich Brand, Merck KGaA, Germany) and ethanolamine (EA, >98%, Sigma-Aldrich Brand, Merck KGaA, Germany) were used to block and deactivate the interface. The use of covalent binding between the nGQDs and protein probes helped reduce non-specific adsorption of antigen targets, and also facilitated the formation of stable covalent bonds between the nGQDs and probe proteins. This immobilization process is depicted in Fig. 6(c).

Detection of nGQDs-based SPR chips for the antigen of S1-RBD protein in PBS

In the assay, the antigen used was the recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike S1 receptor-binding domain (S1-RBD) protein (Tag: human IgG1 Fc, molecular weight: 29.5 kDa; EPY259461, Euprotein, NJ, USA). The antigen was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the running buffer consisted of 10 mM PBS at pH 7.4. Detection of the S1-RBD protein was conducted in PBS. Sensor surface regeneration between cycles was performed using 50 mM NaOH at pH 12.0, prepared in deionized water. In the SPR sensorgram analysis, biomolecular interactions were evaluated based on angle shifts using a regenerable SPR immunoassay to detect various concentrations of the S1-RBD antigen, following multiple washes with the regeneration buffer. A BI-3000G SPR system was used to monitor real-time binding of the S1-RBD protein on the nGQD-based SPR chip and to analyze interactions between the S1-RBD antigen and either anti-S1 antibodies or ACE2 protein. The immunoassay experiments were conducted using a BI-3000G SPR dual-channel instrument, with antibodies immobilized on both channels. Resonance angle shifts were recorded in the test channel upon antigen injection, while the reference channel helped minimize signal noise caused by temperature fluctuations.

Detection of spike RBD protein (S1-RBD) in spiked human blood plasma

Figure 6(d) shows that the structure of SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded RNA virus enveloped by a lipid membrane. This virus strain is characterized by three distinct antigenic proteins on its surface: the Spike (S), Membrane (M), and Envelope (E) proteins. The Nucleocapsid (N) antigen, another structural protein located inside the virus, forms a complex with the RNA and encases it. This N protein plays a crucial role in the life cycle of the virus, interacting with the M protein during virion assembly and enhancing the efficiency of virus transcription and assembly. The structure of the virus is also stabilized by a fragile bond in the lipid membrane that holds the viral RNA, proteins, and outer membrane together. The integrity and shape of these lipid membranes are critical for the ability of the virus to infect cells. The S protein, a class I fusion glycoprotein similar to the influenza glycoprotein, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) fusion glycoprotein (F), and human immunodeficiency virus gp160 (Env), is the major surface protein of coronaviruses and the primary target of neutralizing antibodies60.

The S protein is particularly vital for the ability of the virus to invade human cells, and it is composed of two subunits, Spike 1 (S1) and Spike 2 (S2). The S protein attaches to the ACE2 receptor2,3,61, which is abundantly found on the surface of human lung cells. The receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the S1 subunit is the specific region that binds to the ACE2 receptor. The S2 subunit contains essential elements necessary for membrane fusion. Mutations in the RBD of the S1 protein are crucial in determining the ability of the virus to infect human cells; changes in the RBD can either prevent the virus from binding to ACE2 or increase its affinity for this receptor. According to current scientific literature, amino acid mutations in the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 identified as E484, K417, N501, N439, and N440 enhance the binding affinity between the S1 protein and ACE2, thereby increasing infectivity of the virus by approximately 60%61,64.

Since mutation of the S protein of the virus is the main factor influencing infection and transmission, the aim of the nGQD-based chip developed in this study was to facilitate the detection and analysis of S1 protein RBD binding sites. Figure 6(e) shows that the nGQD-based SPR chip could accurately evaluate kinetic analysis of the RBD binding sensitivity and affinity of ACE2 and Anti-S1 to S1-RBD protein antigen.

Figure 6(f) shows the performance of the nGQD-based SPR chip in the SPR microfluidic system for Kretschmann prism coupling. The system was designed based on double flow channel detection using a 690 laser source to angularly resolve SPR sensing in a BI-3000G SPR dual-channel instrument. In this setup, the test injection sample volume was 200 μL, and the flow rate was maintained at 60 μL/min to detect S1-RBD protein in spiked human blood plasma. To reduce non-specific binding (NSB), bovine serum albumin (BSA) and Tween-20 (Cat. No. P9523, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were added to the plasma samples, which improved hydrophobic and charge interactions between plasma proteins and the sensing surface. The running buffer (PBBT buffer) consisted of 1× PBS, 0.05% Tween-20, and 600 μL of BSA (1 mg/mL) in a total volume of 100 mL, designed to suppress NSB and prevent unwanted protein adsorption on the nGQD surface. All experiments were conducted at a controlled temperature of 22–24 °C. Each assay used a 200 μL injection volume with a flow rate of 30 μL/min. Sensor regeneration between cycles was achieved with 50 mM NaOH at pH 12.0. All measurements were performed in triplicate to ensure accuracy and reproducibility.

Preparation procedure to evaluate assay selectivity

To evaluate the selectivity of the assay for S1-RBD protein, interference assays were performed against five nonspecific proteins: human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, product number 1297001, Sigma-Aldrich), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9, product number MBS2011087, MyBioSource), cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA21-1, TROMA-III, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, USA), human serum albumin (HSA, ≥98%, product number SRP618, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A, product number MBS2011936, MyBioSource, Inc., USA). In addition, S1-RBD protein was tested at a concentration of 100 ng/mL in PBS buffer supplemented with human plasma at concentrations of 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%. All S1-RBD detection experiments were performed at room temperature (23 ± 1 °C) with an injection volume of 200 μL and a flow rate of 30 μL/min.

In the selective experiments, the running buffer consisted of 50 mM NaCl (10 mL) and 0.05% Tween-20 (30 μL), mixed in 100 mL 1× PBS54,55,59. In the spiked protein and spiked plasma experiments, the running buffer consisted of 50 mM NaCl (10 mL), 0.05% Tween-20 (50 μL), and 2 mg/mL BSA (500 μL), which were mixed in 100 mL of 1× PBS54,59. The regeneration buffer used was sodium hydroxide (NaOH 50 mM, pH 12.0–13.0).

All S1-RBD detection experiments were performed at room temperature (23 ± 1 °C) with an injection volume of 200 μL and a flow rate of 30 μL/min.

Data plots and statistical analysis

This study presents reliable results that are independent of the visual output quality of the analyzer. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis, spectral interpretation, and derivative regression were conducted using OriginPro software (version 2024b, OriginLab Corporation, USA). SPR data calculation and interpretation followed previously published methods. Affinity and kinetic constants were determined using Biosensing Instrument software (version 2.4.4, Biosensing Instrument Inc., Tempe, AZ, USA). Line intensities on the lateral flow assay (LFA) strips were quantified using 8-bit grayscale analysis in ImageJ software (version 1.54).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. The data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhu, N. et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in china, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 727–733 (2020).

Lu, R. et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 395, 565–574 (2020).

Zhou, P. et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273 (2020).

World Health Organization. Origin of SARS-CoV-2, 26 March 2020. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332197 (2020).

World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic 2023. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19, (2023).

Molina-Mora, J. A. et al. Clinical profiles at the time of diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Costa Rica during the pre-vaccination period using a machine learning approach. Phenomics 2, 312–322 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Antibody seroprevalence in the epicenter Wuhan, Hubei, and six selected provinces after containment of the first epidemic wave of COVID-19 in China. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 8, 100094 (2021).

Wrapp, D. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367, 1260–1263 (2020).

Yan, H. et al. ACE2 receptor usage reveals variation in susceptibility to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 infection among bat species. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 600–608 (2021).

Hoffmann, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271–280.e8 (2020).

Peacock, T. P. et al. The furin cleavage site in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is required for transmission in ferrets. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 899–909 (2021).

Li, M. Y. et al. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infect. Dis. Poverty 9, 45 (2020).

Trypsteen, W. et al. On the whereabouts of SARS-CoV-2 in the human body: A systematic review. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1009037 (2020).

Ni, W. et al. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in COVID-19. Crit. Care 24, 1–10 (2020).

Yan, J. et al. Potential influence of COVID-19/ACE2 on the female reproductive system. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 26, 367–373 (2020).

Madjunkov, M. et al. A comprehensive review of the impact of COVID-19 on human reproductive biology, assisted reproduction care and pregnancy: a Canadian perspective. J. Ovarian Res. 13, 1–18 (2020).

Lucchese, G. Cerebrospinal fluid findings in COVID-19 indicate autoimmunity. Lancet Microbe 1, e242 (2020).

Kwon, T. K. et al. Seasonal stability of SARS-CoV-2 in biological fluids. Pathogens 10, 540 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J. Med. Virol. 92, 833–840 (2020).

Azzi, L. et al. Saliva is a reliable tool to detect SARS-CoV-2. J. Infect. 81, e45–e50 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet 395, 809–815 (2020).

Huang, W. E. et al. RT-LAMP for rapid diagnosis of coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Microb. Biotechnol. 13, 950–961 (2020).

Lalli, M. A. et al. Rapid and extraction-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 from saliva by colorimetric reverse-transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Clin. Chem. 67, 415–424 (2021).

Ganguli, A. et al. Rapid isothermal amplification and portable detection system for SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 22727–22735 (2020).

Aoki, M. N. et al. Colorimetric RT-LAMP SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic sensitivity relies on color interpretation and viral load. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–10 (2021).

Dong, Y. et al. Comparative evaluation of 19 reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays for detection of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 11, 2936 (2021).

Seo, G. et al. Rapid detection of COVID-19 causative virus (SARS-CoV-2) in human nasopharyngeal swab specimens using field-effect transistor-based biosensor. ACS Nano 14, 5135–5142 (2020).

Fathi-Hafshejani, P. et al. Two-dimensional-material-based field-effect transistor biosensor for detecting COVID-19 virus (SARS-CoV-2). ACS Nano 15, 11461–11469 (2021).

Yakoh, A. et al. Paper-based electrochemical biosensor for diagnosing COVID-19: detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and antigen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 176, 112912 (2021).

Chaibun, T. et al. Rapid electrochemical detection of coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 12, 802 (2021).

Song, Z. et al. Electrochemical biosensor with enhanced antifouling capability for COVID-19 nucleic acid detection in complex biological media. Anal. Chem. 93, 5963–5971 (2021).

Carlomagno, C. et al. COVID-19 salivary Raman fingerprint: innovative approach for the detection of current and past SARS-CoV-2 infections. Sci. Rep. 11, 4943 (2021).

Yin, G. et al. An efficient primary screening of COVID-19 by serum Raman spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 52, 949–958 (2021).

Guenther, D. A. Ocean Insight: COVID-19 Antibody detection with surface enhanced raman scattering, Proc. SPIE 11715, SPIE BiOS Exhibition Product Demonstrations, 1171509 (2021).

Wang, D. et al. Rapid lateral flow immunoassay for the fluorescence detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 1150–1158 (2020).

Lee, J. H. et al. A novel rapid detection for SARS-CoV-2 spike 1 antigens using human angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Biosens. Bioelectron. 171, 112715 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Development of spike protein-based fluorescence lateral flow assay for the simultaneous detection of SARS-CoV-2 specific IgM and IgG. Analyst 146, 3908–3917 (2021).

Qiu, G. et al. Dual-Functional plasmonic photothermal biosensors for highly accurate severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 detection. ACS Nano 14, 5268–5277 (2020).

Moitra, P. et al. Selective naked-eye detection of SARS-CoV-2 mediated by N gene targeted antisense oligonucleotide capped plasmonic nanoparticles. ACS Nano 14, 7617–7627 (2020).

Basso, C. R. et al. Fast and reliable detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies based on surface plasmon resonance. Anal. Methods 13, 3297–3306 (2021).

Ji, D. et al. Electrochemical detection of a few copies of unamplified SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acids by a self-actuated molecular system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 13526–13537 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Wearable bioelectronic masks for wireless detection of respiratory infectious diseases by gaseous media. Matter 5, 4347–4362 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Measurements of aptamer–protein binding kinetics using graphene field-effect transistors. Nanoscale 11, 12573–12581 (2019).

Martins, G. et al. Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots (N-GQDs): a promising material for the development of electrochemical immunosensors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 8, 5908–5918 (2025).

Geng, B. et al. DNA binding graphene quantum dots inhibit dual topoisomerases for cancer chemotherapy. Carbon 187, 365–374 (2022).

Üzek, R. Engineering a graphene quantum dot-enhanced surface plasmon resonance sensor for ultra-sensitive detection of Hg2+ ions. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 12, 2400679 (2024).

Ogi, T. et al. Transient nature of graphene quantum dot formation via a hydrothermal reaction. RSC Adv. 4, 55709–55715 (2014).

Peng, J. et al. Graphene quantum dots derived from carbon fibers. Nano Lett. 12, 844–849 (2012).

Liu, Y. J. et al. Pyrrolic-nitrogen doped graphene: a metal-free electrocatalyst with high efficiency and selectivity for the reduction of carbon dioxide to formic acid: a computational study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 5491–5498 (2016).

Xu, L. et al. Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots with oxygen-rich functional groups. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 2244–2253 (2014).

Hao, J. et al. Time-resolved luminescence properties of laser-fabricated nano-diamonds. Nanoscale Res Lett. 15, 168 (2020).

Dong, Y. et al. Blue luminescent graphene quantum dots and graphene oxide prepared by tuning the carbonization degree of citric acid. Carbon 50, 4738–4743 (2012).

Ogi, T. et al. Kinetics of nitrogen-doped carbon dot formation via hydrothermal synthesis. N. J. Chem. 40, 5555–5561 (2016).

Chiu, N.-F. & Yang, H.-T. High-sensitivity detection of the lung cancer biomarker CYFRA21-1 in serum samples using a carboxyl-MoS2 functional film for SPR-based immunosensors. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 234 (2020).

Chiu, N.-F. et al. Clinical application for screening Down’s Syndrome by using carboxylated graphene oxide-based surface plasmon resonance aptasensors. Int. J. Nanomed. 15, 8131–8149 (2020).

Chiu, N.-F. et al. Immunoassay-amplified responses using a functionalized MoS2-based SPR biosensor to detect PAPP-A2 in maternal serum samples to screen for fetal Down's syndrome. Int. J. Nanomed. 16, 2715–27333 (2021).

Ju, J. et al. Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots-based fluorescent probe for the sensitive turn-on detection of glutathione and its cellular imaging. RSC Adv. 4, 52583–52589 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots with oxygen-rich functional groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 15–18 (2012).

Chiu, N.-F. et al. High-affinity carboxyl-graphene oxide-based SPR aptasensor for the detection of hCG protein in clinical serum samples. Int. J. Nanomed. 14, 4833–4847 (2019).

Corbett, K. S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature 586, 567–571 (2020).

Lu, J. & Sun, P. D. High affinity binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein enhances ACE2 carboxypeptidase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 18579–18588 (2020).

Chiu, N.-F. & Lin, T.-L. Affinity capture surface carboxyl-functionalized MoS2 sheets to enhance the sensitivity of surface plasmon resonance immunosensors. Talanta 185, 174–181 (2018).

Chiu, N.-F. et al. Carboxyl-functionalized graphene oxide composites as SPR biosensors with enhanced sensitivity for immunoaffinity detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 89, 370–376 (2017).

Winger, A. & Caspari, T. The spike of concern—the novel variants of SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 13, 1002 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of China (ROC), Taiwan, for financially supporting this research under Contract No. MOST 108-2221-E-003 -020 -MY3, MOST 109-2221-E-003-028-MY3, and NSTC 112-2221-E-003 -016 -MY3. The authors would like to thank Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua City, Taiwan. This work was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Changhua Christian Hospital for Human Clinical Trials (Permit Numbers: CCH IRB No.: 200518). All experiments were performed in compliance with the relevant laws and institutional guidelines, and the Human Subjects Research Ethics Committee of Changhua Christian Hospital approved the experiments. This work is sponsored by “Higher Education Sprout Project” of National Taiwan Normal University and the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.F.C., M.J.T., and T.H.K. designed the study and analyzed the data; M.J.T., J.C.L., and D.T.N. performed the device fabrication, collected the experimental data and analyzed the data; T.H.K. provided support with the IRB supervision and clinical guidance; N.F.C., M.J.T., J.C.L., and D.T.N. performed TEM, SPR, LFA, absorption spectra, PL spectra, FTIR, and XPS analyzes; N.F.C. and M.J.T. performed the post-processing of data, programming and implementation of computational methods; N.F.C. provided guidance for the experimental setups, wrote the paper and oversaw the project and performed the overall editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chiu, NF., Tai, MJ., Lin, JC. et al. Enhanced detection of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein using nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dot-based SPR biosensors. npj Biosensing 2, 28 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00046-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00046-x

This article is cited by

-

Ultra-low detection of SARS-CoV-2 Virus Like Particles (VLPs) with functionalized gold plasmonic nanoresonator array

Biomedical Microdevices (2025)