Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are easily accessible in biological fluids and carry the molecular “fingerprints” of their parent cells, making them compelling candidates for minimally invasive cancer diagnostics. For future translation into clinical settings, greater sensitivity and specificity are desired. Here, we achieve near-perfect classification for cancerous (2 types) and non-cancerous cell-derived EVs by using nanoaperture optical tweezers (NOTs) and deep learning. The NOT approach is label-free and has single-EV sensitivity – the signal acquired is simply the laser tweezer scattered light. The high level of specificity is achieved by the custom design of a four-layer convolution and Kolmogorov–Arnold linear layer deep learning model. Several other models are compared with this approach. Beyond diagnostics, this platform opens avenues for real-time EV profiling, deepening our biological understanding and advancing the development of minimally invasive personalized medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are accessible in biological fluids and carry the molecular “fingerprints” of their parent cells, making them ideal candidates for non-invasive diagnostics1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. These vesicles provide a snapshot of cellular activities and molecular contents, such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, offering valuable insights into the state of the parent cells, including whether they are cancerous or non-cancerous4,9. This accessibility and richness of information make EVs attractive for early cancer detection.

EV populations are highly heterogeneous, however, with their physical and biochemical properties varying significantly between different cell types4,5. This inherent variability—resulting from differences in cell origin, state (e.g., non-cancerous vs. cancerous), and the conditions under which EVs are released—presents a significant challenge for accurate and consistent detection10,11. The overlapping features of EVs from cancerous and non-cancerous cells make it difficult to reliably distinguish between them, hindering EV-based diagnostics in clinical settings. To overcome this challenge, machine learning (ML) approaches have been widely adopted to enhance the sensitivity and accuracy of cancer diagnostics based on EVs10,12,13,14,15. ML techniques, focusing on classification algorithms16, can analyze complex data from EVs, enabling the identification of subtle patterns and differences that may be imperceptible to traditional methods10,14,15. By learning from large datasets, ML algorithms have the potential to accurately classify EVs, even when their physical characteristics overlap, making them an invaluable tool for improving diagnostic precision17,18.

Many existing detection methods rely on labeling or binding markers, which increases complexity, raises costs, and risks altering the native state of EVs4,5. These requirements limit their practicality for large-scale, real-time diagnostics, where simplicity and speed are critical. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and enzyme tests6,19 use multiple labels to improve specificity when targeting known biomarkers. This further increases complexity and cost, and still falls short in capturing the full heterogeneity of EV populations.

Given the cost, complexity, and limited specificity of label-based methods, many researchers have turned to label-free approaches such as constituent analysis4,20, electrochemistry21,22, fluorescence23,24, and Raman spectroscopy25,26,27,28,29. Constituent analysis methods, including mass spectrometry and PCR, provide molecular information of EVs but require complex, costly procedures. Raman spectroscopy offers chemical profiling of EVs but suffers from inherently low signal strength, often necessitating signal amplification or aggregation of multiple EVs to improve detection reliability25,30.

To overcome these limitations, machine learning has been applied to improve the sensitivity and efficiency of EV classification10,12,13,14,15,31. A range of algorithms have been explored, including principal component analysis (PCA)22, linear discriminant analysis (LDA)21,32, partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLSDA)33,34, XGBoost35, support vector machine (SVM)23, k-nearest neighbor (KNN)24, and lightweight deep learning models36,37. While these methods show promise, they still face common challenges, including the risk of overfitting, high computational cost, and intricate preprocessing requirements31. In particular, many traditional models rely on handcrafted features and are limited in capturing nonlinear, temporally structured patterns in raw trapping signals18. For heterogeneous populations like EVs, achieving reliable classification requires not only well-designed algorithms but also higher-quality, more informative signals. This points to the importance of improving the detection platform itself, to provide better data inputs that can effectively support deep learning-based EV classification.

To balance the trade-offs among cost, complexity, and sensitivity, a low-cost, facile, and high-signal approach is required for ML/DL EV analysis. Single-particle detection offers several advantages: not only does it improve signal quality, but it also provides critical insights into EV heterogeneity, allowing the system to learn within a diverse population38,39. Optical trapping has emerged as a promising method to capture and analyze individual EVs in solution, offering label-free detection without the need for complex constituent analysis or binding interactions40,41,42.

Among various label-free platforms, nanoaperture optical tweezers (NOTs) have shown particular promise for enhancing trapping efficiency and sensitivity at the single-particle level41,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. Variants of NOT designs—including coaxial apertures54, Fano resonant structures52,53, nanoholes55, double-well structures56, and bowtie nano-apertures48,57—have been developed to further improve trapping capabilities. These platforms have demonstrated effective trapping and dynamic observation of single biomolecules, including proteins, DNA, enzymes, and nanoparticles, under low optical power conditions39,58,59,60,61,62,63,64.

The application of cancer detection from EVs requires extremely high accuracy due to the rarity of cancer cell-derived EVs. We originally worked on convolutional neural networks to do the classification, and although these achieved an accuracy of 88%11, much higher accuracy is required. For this reason, we have adopted a deep learning approach. The loss plots show convergence, which demonstrates that our approach is not overfitting the data18. This shortfall largely arose from the inherent heterogeneity of EVs and overlapping signal patterns, which limited classification performance. In this study, we address these challenges by integrating improved deep learning methodologies with DNH optical tweezers, significantly enhancing classification accuracy and demonstrating a robust framework for single-particle, label-free EV analysis. We expand on that previous work by integrating both the original dataset and new data collected in this study. New trapping data were gathered by different operators, with a time gap between collections to ensure reproducibility. To further validate the robustness of our approach, measurements were repeated on EVs produced under different batches and trapped by different researchers. Multiple samples were collected in each batch, creating a broad, robust, and generalized dataset, referred to as the EV trapping dataset.

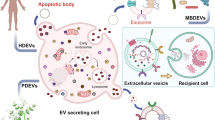

We developed the TrapNet-NOTs optical tweezer framework—a multiscale deep learning approach for low-power, high-throughput trapping of single EVs using cost-effective optical tweezers. Our framework achieves 100% accuracy in classifying EVs as cancerous or non-cancerous on the current dataset. Figure 1a shows the EV biogenesis pathway to clarify the origin and size diversity of vesicles analyzed in this study, which is relevant to their trapping behavior. The process begins by loading isolated EVs into the NOTs setup, where single EVs are trapped, and the trapping signals are recorded (Fig. 1a). Representative trapping events for MCF10A (non-malignant), MCF7 (poorly invasive, cancerous), and MDA-MB-231 (highly invasive, cancerous) EVs are shown in Fig. 1b, illustrating the observed data for each cell line. Probability density functions are applied to the transmission signals to capture amplitude and qualitative changes during trapping. Pre- and post-processing stages prepare the data for analysis by TrapNet (Fig. 1c), which trains, validates, and tests the model. Beyond classification, TrapNet extracts features from the latent space to interpret the learning process, as visualized in Fig. 1d.

a Exosomes bud inward into MVBs and are released when MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane. (LE: intraluminal vesicles; MVBs: multivesicular bodies; EE: early endosome; TGN: trans-Golgi network). EV samples are diluted, placed on the sample stage, and covered by the double nanohole (DNH) aperture. Single EVs are trapped using a DNH optical tweezer, with trapping signals detected by a photodiode. b Representative trapping signals, their probability density functions, and power spectral density boxcar averages are shown, each fitted with a Lorentzian curve across different EV lines. c Signals are pre-processed and split (8:1:1) into training, validation, and test sets before being encoded and input into deep learning networks. The model is trained to optimize classification performance and extract latent features for visualization and downstream analysis. d Final outputs include EV class predictions and visualizations of the latent feature space.

Combining optical signals with deep learning, this label-free approach accurately classifies EVs into non-malignant, non-invasive cancerous, and invasive cancerous groups. Our method achieves 100% accuracy in classifying non-cancerous and cancerous cases and 99% overall accuracy across the three EV classes, MCF10A, MCF7, and MDA-MB-231, highlighting its potential for clinical translation.

Results

Nanoaperture optical tweezers

The double nanohole (DNH) aperture was fabricated using low-cost colloidal lithography, as described previously65 and detailed in the “Methods” section. A gold layer was deposited on a microscope coverslip with an image spacer to form a shallow well for the EV solution (Supplementary Fig. S3). The assembled chip was mounted onto an inverted optical tweezer system adapted from a commercial platform (Thorlabs OTKB). A continuous-wave 980 nm laser was used for trapping, selected for its strong field enhancement within the DNH. Simulated electric field distributions are provided in the Supplementary Information (SI).

Upon trapping, a sudden step is observed in the transmission signal due to dielectric loading of the aperture by the EV, which increases the effective optical cross-section. This event marks the beginning of the trapping period, typically lasting less than one minute. The transmission signal during trapping exhibits amplified characteristic thermal fluctuations, and its PSD increases significantly, reflecting the dynamic motion of the trapped particle. Representative time-series signals and corresponding PSDs are shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs. S5–S7(SI). In the past, optical trapping analysis, Lorentzian fitting of the PSD, and corner frequency estimation were commonly used to quantify trap stiffness and particle properties. However, in this study, our objective was not to extract specific mechanical parameters, but rather to use the entire time-domain trapping signal as input to a deep learning model. Therefore, we did not isolate or compute these features explicitly; instead, the model learns relevant patterns directly from the raw temporal signal39,46,58,59,60,63,64.

Classical analysis methods based on these physical features, while informative, are often insufficient to distinguish between EVs of different cellular origin due to overlapping distributions and signal noise. To address this, we previously implemented a lightweight 1D convolutional neural network (CNN) to classify EVs directly from the trapping signal. This approach achieved 88% overall accuracy11, demonstrating potential but falling short of the clinical threshold required for commercial diagnostics (~99%)4.

To enhance both performance and reproducibility, we expanded the dataset by more than two-fold. New measurements were acquired across multiple days, involving different DNHs (within the average cusp size), EV batches, and operators—measures taken deliberately to improve generalizability and reduce potential batch effects. In parallel, we systematically evaluated and optimized several deep learning architectures to increase classification accuracy with future clinical applications in mind. For robust generalization and to prevent any form of data leakage, the dataset was randomly divided into independent training, validation, and testing subsets in an 8:1:1 ratio. All reported model performance metrics are based exclusively on the held-out test set, which remained entirely unseen throughout training and hyperparameter tuning. Additional implementation details and precautions are outlined in the “Modeling, training, validating, and testing” section.

Deep learning approaches

To evaluate suitable deep learning architectures for EV classification, we benchmarked five established models: Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)66, Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM)67, CNN18, Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (CLSTM)68, and Transformer69. These models were selected for their relevance in time-series analysis and biomedical signal extraction18,66.

Recurrent neural networks, including LSTM and Bi-LSTM, were initially adapted due to their strength in modeling sequential dependencies18,66,67. LSTM achieved an overall accuracy of 94.4%, while Bi-LSTM improved performance slightly to 95.8%. We then tested a deeper CNN architecture, which reached 97.6% accuracy, and a hybrid CLSTM model that combines convolutional feature extraction with temporal modeling, achieving 97.1%. We also evaluated a lightweight Transformer model with 2 attention heads and a 16-dimensional embedding space. Despite its theoretical capacity to capture global dependencies, the model only achieved 95% overall accuracy.

To achieve the 99% classification accuracy necessary for clinical translation, we developed TrapNet—a compact, fast, convolution-based architecture specifically optimized for EVs classification tasks. TrapNet consistently outperformed the baseline models, demonstrating higher overall accuracy (99%), perfect ability to distinguish which EVs are derived from cancerous cells (100% accuracy), and more robust feature extraction across all three EV categories. As an integral component of our label-free diagnostic pipeline, it enables real-time, in-solution classification directly from raw trapping signals, with no requirement for molecular labeling, preprocessing, or external feature engineering.

Architecture and functional overview of TrapNet

As shown in Fig. 2a, TrapNet processes optical trapping data through a convolutional feature extractor and a classifier using a Kolmogorov–Arnold network layer. The network extracts contextual features from complex time-series signals by progressively refining the input data to reveal key biological signatures underlying trapping behavior. The first layer, Conv1, applies 128 filters with a kernel size of 3 and padding of 1. Conv2, Conv3, and Conv4 increase the feature map depth from 256 to 2048, using the same kernel size and padding. Each convolutional layer is followed by Layer Normalization (LN) to improve training stability and speed, and ReLU activation to introduce non-linearity. A pooling layer reduces dimensionality before flattening and applying a dropout mask (rate 0.6) to prevent overfitting by randomly zeroing features during training.

a The split trapping signal dataset is loaded onto the GPU and processed through convolutional neural networks. During training, dropout and layer normalization are applied to enhance robustness and stabilize learning. After max-pooling and flattening, features are passed to the KAN layer for the final classification of EV types. b TrapNet extracts hidden features from the latent space, revealing how the network differentiates data classes based on physical parameters such as power spectral density, transmission variance, corner frequency, trapping stiffness, and surface charge.

In TrapNet, we replace the traditional fully connected output layer with a Kolmogorov–Arnold Network (KAN) layer70. This layer uses learnable spline-based activation functions to better capture complex nonlinear relationships without relying on linear weights70. Compared to simpler parameterized units like PReLU, KAN’s spline-based structure allows the network to model more complex, smooth, and non-monotonic temporal patterns, which are essential for accurately representing EV trapping dynamics. It outputs class probabilities for the three EV types. Our results show that the KAN layer significantly improves network convergence and computational efficiency, which are critical for handling large datasets in real-world diagnostics.

Deep learning models capture physical features from optical trapping data that extend beyond human perception. Optical trapping signals provide information on nanoparticle size and shape64,71, vibrational dynamics41, protein interactions58, and even enzyme catalytic processes63. For physicists, chemists, and clinicians, identifying key physical indices is essential for understanding the behavior of single nanoparticles, such as isolated EVs.

To identify the features used by the network to classify EVs, we analyzed the features extracted in the hidden layers (Fig. 2b). The latent space aggregates high-dimensional features from the network’s convolutional and pooling layers, including power spectral density, transmission variance, corner frequency, trapping stiffness, and surface charge of the DNH aperture (Fig. 2). These features capture the physical properties that distinguish non-malignant, non-invasive cancerous, and invasive cancerous EVs, capturing a comprehensive molecular profile of each vesicle. To visualize the latent space, we applied t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) to reduce the feature space to two dimensions. t-SNE projects similar inputs to nearby points while preserving cluster relationships from the original high-dimensional space72.

Generalizability of DL classification with samples

Considering real-world clinical scenarios, we conducted optical trapping experiments to isolate and classify three EV groups. The goal was to evaluate the robustness and applicability of TrapNet on an independent test set. For comparison, we benchmarked TrapNet against five established deep learning models18: LSTM, Bi-LSTM, CLSTM, CNN, and Transformer69. All models were trained on the same dataset with identical seeds to ensure fair comparison.

We calculated the confusion matrices for all models to quantify classification performance (Fig. 3). These matrices map true labels against predicted labels, providing a clear measure of accuracy and robustness. Darker shades indicate higher counts, highlighting each model’s ability to correctly identify EV types. Diagonal cells represent correct classifications, while off-diagonal cells indicate misclassifications. TrapNet shows near-perfect performance, correctly classifying 104 MDA-MB-231, 191 MCF7, and 110 MCF10A samples, with only one MCF7 sample misclassified as MDA-MB-231 and three MDA-MB-231 as MCF7, as shown in Fig. 3a.

The LSTM model (Fig. 3b) shows reasonable performance, correctly classifying 102 MDA-MB-231 and 181 MCF7 samples, but misclassifying 11 MCF7, 7 MCF10A, and 5 MDA-MB-231 samples. Bi-LSTM (Fig. 3c) improves marginally over LSTM, correctly classifying 103 MDA-MB-231, 183 MCF7, and 106 MCF10A samples, but still misclassifying MCF7 and MCF10A due to limited feature representation. CNN (Fig. 3d) achieves performance close to TrapNet, with only 10 misclassifications overall. CLSTM (Fig. 3e) performs slightly better, correctly identifying 103 MDA-MB-231, 185 MCF7, and 109 MCF10A samples, with 12 total errors, reflecting the benefit of combining spatial and temporal features. The Transformer model (Fig. 3f) correctly classifies 103 MDA-MB-231, 186 MCF7, and 99 MCF10A samples but misclassifies 10 MCF10A as MCF7 and 11 samples across other categories, likely due to global attention capturing redundant signals at the expense of critical local features.

We evaluated precision, recall, and F1 scores for classifying MDA-MB-231, MCF7, and MCF10A across six deep learning models. TrapNet outperforms all others, achieving 99% overall accuracy (Fig. 4a), with full scores in all aspects (100%) for MCF10A, and high precision, recall, and F1 scores for MCF7 (98.5%, 99.5%, 99.0%) and MDA-MB-231 (99.0%, 97.2%, 98.1%). These results confirm TrapNet’s superior classification performance and minimal misclassification.

In comparison, LSTM (Fig. 4b) and Bi-LSTM (Fig. 4c) achieve lower overall accuracies of 94.4% and 95.8%, respectively, with Bi-LSTM performing slightly better on MDA-MB-231 (precision 96.2%, recall 96.3%). CNN (Fig. 4d) achieves 97.6% accuracy with balanced metrics across EV classes, while CLSTM (Fig. 4e) performs comparably at 97.1%, benefiting from its hybrid architecture. The Transformer model (Fig. 4f) reaches 94.9% accuracy but struggles with MCF7 and MCF10A, with lower recall (90%) and F1 scores (93%).

We repeated the training, validation, and testing process using 20 randomly generated seeds to avoid biased distribution of the dataset and ensure robustness in our results. Fig. 4g shows the distribution of overall accuracy across these 20 trials, providing an understanding of model stability and generalizability. The histogram illustrates the range of overall accuracies achieved, with most values clustering between 96% and 99%, indicating consistent model performance. The fitted Gaussian curve demonstrates the central tendency of the model’s performance, with a peak of around 97%–98% overall accuracy. This consistency across multiple trials reinforces the reliability of our deep learning model, indicating that TrapNet can achieve high EVs classification accuracy regardless of the random variations in dataset splits.

To assess computational efficiency, we compared TrapNet with LSTM, Bi-LSTM, CLSTM, CNN, and Transformer, as summarized in Table 1. The Transformer achieved the shortest training time (24 min) but required the most epochs to converge (1070). Bi-LSTM had the largest parameter count (138.9M), while CLSTM, despite high accuracy, had the longest training time. TrapNet and CNN, with low parameter counts (2.1M), trained faster and maintained strong performance, balancing efficiency and accuracy. All models used the same learning rate (5 × 10−5) and patience parameter (200). Overall, TrapNet offers the best balance of training time, memory use, and computational cost, making it well-suited for optical trapping signal analysis.

TrapNet enhances the visualization and interpretation of the diagnosis

We have applied several traditional methods, such as analyzing power spectral density (PSD), autocorrelations, and changes in transmission percentages through DNH, to analyze our trapping data. While these methods provide useful insights, they struggle to handle the inherent noise and complexity of time-series data, particularly when distinguishing closely related EV heterogeneity. In contrast, deep learning models have shown remarkable effectiveness in classifying different EV types from noisy trapping signals, as they can extract meaningful patterns from such complex data. To better understand how deep learning performs so well, we analyzed the latent spaces and representation of complex biological information and applied Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM)73to visualize the regions most influential for classification, which is shown in SI.

Figure 5a–f shows t-SNE visualizations of feature spaces extracted by six deep learning models at the final network layer: TrapNet, LSTM, Bi-LSTM, CNN, CLSTM, and Transformer. t-SNE reduces the high-dimensional feature space into two dimensions74, allowing us to visualize how each model organizes the latent features of the three EV types (MDA-MB-231, MCF7, MCF10A). TrapNet (Fig. 5a) forms well-defined clusters with clear boundaries, indicating its strong ability to extract distinct and separable features, which is essential for accurate classification. In contrast, LSTM (Fig. 5b) and Bi-LSTM (Fig. 5c) show overlapping clusters, particularly between MCF7 and MDA-MB-231, indicating difficulty in distinguishing biologically similar EV types. CNN (Fig. 5d) shows moderate clustering, but with less distinct boundaries, suggesting limited sensitivity to nonlinear features. CLSTM (Fig. 5e) improves clustering over LSTM and Bi-LSTM, reflecting its advantage in capturing both spatial and sequential patterns, although some overlap remains between MCF7 and MDA-MB-231. The Transformer model (Fig. 5f) produces scattered clusters with poorly defined boundaries, likely due to its reliance on global attention, which may dilute local feature distinctions in this dataset.

a TrapNet, b LSTM, c Bi-LSTM, d CNN, e CLSTM, and f Transformer, applied to classify three EV types: MDA-MB-231 (purple), MCF7 (green), and MCF10A (yellow). These plots show the clustering of individual EVs based on extracted features, with color indicating EV class. The degree of cluster separation reflects each model’s ability to extract features and classify EVs accurately.

When combined with t-SNE, we observe that data points of the same color are divided into two groups (e.g., Fig. 5). This separation can be attributed to domain shifts, which refer to changes in data distribution caused by variations such as different operators, EV batches, inherent heterogeneity of EVs, or differences between training and testing environments. Such shifts make it challenging for deep learning models to generalize, often leading to reduced classification accuracy. LSTM, Bi-LSTM, CNN, CLSTM, and Transformer models exhibit subgroups within the same EV category, showing difficulty in generalizing across the dataset. These models are more sensitive to domain shift, struggling to distinguish EV types from different batches or operators. In contrast, TrapNet shows well-defined clusters with nearly invisible boundaries between batches in the MCF10A category. This aligns with the classification results in Figs. 3a and 4, where TrapNet achieves perfect precision, F1, and recall scores, demonstrating its ability to handle domain shifts effectively and enabling more reliable classification of both cancerous and non-cancerous EVs.

Figure 6a and b shows the t-SNE visualizations for the test and training sets, respectively, with circle size representing the average PSD of each signal. The three EV types form distinct clusters, with MDA-MB-231 (purple) showing the smallest circles (lowest mean PSD), MCF7 (green) displaying intermediate sizes, and MCF10A (yellow) the largest (highest mean PSD). This PSD gradient reflects underlying biophysical properties such as corner frequency and transmission variance, which correlate with trapping stiffness. Surface charge, linked to zeta potential, also influences the transmission signal. These variations between cancerous and non-cancerous EVs provide valuable insights into their trapping behavior and physical characteristics.

While the network does consider PSD as an important feature for classification, the Grad-CAM feature heatmap (shown in SI) still reveals significant overlap in the signal regions, particularly between MCF7 and MDA-MB-231. This suggests that despite the inclusion of PSD, there are still additional factors influencing the classification that are not immediately apparent from the PSD alone. The complexity of the network’s learning process suggests that further exploration of additional features is needed to fully understand the underlying factors at play.

Discussion

TrapNet is the core analytical method of our NOT platform, enabling trustworthy, label-free classification of EVs based on their optical trapping signatures. Integrated with DNH tweezers, the system analyzes individual EVs directly in solution, without molecular labeling, staining, or biochemical modification, thereby preserving the vesicles’ native biophysical properties. This in situ, real-time analysis capability is essential for accurate and minimally invasive early cancer detection.

A key strength of the platform is its ability to operate directly on raw transmission signals—eliminating the need and expense for substantial preprocessing or handcrafted feature engineering. TrapNet can not only observe fluctuations in the trapping signal that arise from intrinsic EV properties, such as size, shape, refractive index, and surface charge, but also some hidden features that we usually do not pay attention to. By learning from these hidden, often unresolvable observation differences, the network achieves high classification accuracy even across heterogeneous EV populations.

The latent representations extracted by TrapNet are also interpretable, offering insight into the physical basis of EV class separation. This supports its potential integration into an on-demand, clinician-assist framework75, where real-time feedback and biological insight are both critical. Together, the TrapNet-NOTs system offers a compact, low-complexity diagnostic tool that combines minimal sample preparation with high robustness and clinical relevance.

While the current framework demonstrates strong classification performance and label-free operability, several practical challenges remain to be addressed for broader clinical translation. In particular, sensitivity and throughput are areas for future optimization. Although the system performs well at the single-EV level, real-world applications may require detection at abundance levels well below current thresholds. For instance, tumor-derived EVs can constitute less than 1 in 100,000 of all circulating vesicles38, requiring substantially higher detection sensitivity to support early-stage diagnostics. In addition, accessing diagnostically relevant EVs remains a challenge in certain clinical contexts. For malignancies such as glioblastoma, the presence of the blood-brain barrier significantly limits the release and detectability of tumor-derived EVs in peripheral circulation76. In such cases, the feasibility of our detection method depends critically on obtaining representative and accessible biofluid samples, which may require cerebrospinal fluid collection or alternative biomarker strategies. It is important to develop both upstream enrichment techniques and downstream high-throughput analysis to extend the applicability of the TrapNet-NOTs framework across diverse clinical scenarios.

One promising avenue is the use of pre-selection or enrichment techniques to increase the proportion of tumor-relevant EVs prior to trapping. These enrichment steps are not dependent on prior classification but operate based on general tumor-associated markers or EV biophysical properties, making them compatible with downstream label-free classification. These approaches—ranging from immunoaffinity capture to microfluidic sorting—could be integrated upstream of the NOT workflow to reduce analysis time and enhance diagnostic sensitivity. For example, recent studies suggest that detection rates for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) can reach 97% when tumor volumes exceed 0.1 cm338, underscoring the importance of enrichment-based strategies in early-stage cancer detection. While some of these approaches may reintroduce labeling or surface tethering, they offer a practical compromise to accelerate deployment in clinical workflows. While the classification accuracy we achieved in this work is, in our opinion, very high, clinical application will likely require this high accuracy in addition to some preconcentration approaches.

Beyond improvements in the preprocessing methods, algorithmic strategies are also critical to scaling EV-based diagnostics. Federated learning (FL) offers a promising strategy to address data scarcity and privacy challenges in EV-based diagnostics77,78. Using a decentralized model, training across multiple institutions without transferring raw data, it is easy to build a more generalized model while preserving patient confidentiality. This is particularly advantageous for rare cancers or low-abundance EV cell lines, where assembling large centralized datasets from one or two institutes is often impractical. Moreover, FL frameworks can support continual learning from distributed clinical centers, allowing the model to evolve and generalize in real-world deployment.

Alternatively, efforts to massively parallelize optical trapping offer a path toward overcoming throughput constraints without sacrificing the advantages of label-free analysis. Techniques employing large-scale arrays of optical apertures—potentially reaching tens of thousands of traps (around 15,000 wells) in a single field of view—could enable simultaneous measurement of thousands of EVs79. When paired with high-speed camera systems and automated classification pipelines, such designs have the potential to scale the TrapNet-NOTs system for high-throughput diagnostics.

Here, we demonstrated that deep learning can achieve clinically relevant accuracy using only the optical scattering signals of individual EVs, without labeling, complex preprocessing, or spectroscopic analysis. This was not previously obvious, given the noisy and weak nature of the optical signal. By extracting and interpreting hidden features directly from raw data, which we expect is related to the biophysical attributes of the highly heterogeneous EV population. This shows that real-time, label-free EV classification is possible at the single-molecule level, which is promising for future clinical translation. Further improvements in trapping throughput and model optimization will be critical to meet the efficiency and sensitivity requirements for early detection.

Methods

Colloidal lithography of DNHs

All double nanoholes (DNHs) used in this study were fabricated using a modified colloidal lithography technique, adapted from a low-cost method previously reported by previous work65. All fabricated DNHs were pre-screened to verify optical trapping capability and exhibited cusp sizes ranging from 100 to 120 nm, consistent with geometries known to support stable trapping. Commercial microscope slides (Fisherbrand, 1 mm thickness) were first cleaned with lens paper to remove dust and inspected for visible scratches. The slides were then cut to 75 × 50 mm using a diamond scribe. To remove fine particles, they were sonicated in ethanol for 10 min, dried with compressed nitrogen, and treated with oxygen plasma for 15 min to improve surface cleanliness. A 10 μL aliquot of 0.01% w/v polystyrene spheres (600 nm diameter, diluted in ethanol) was drop-coated onto each slide. The slides were left overnight in a clean container to allow solvent evaporation and spontaneous aggregation of the spheres onto the surface. After the monolayer formed, a metal film consisting of 7 nm titanium and 70 nm gold was deposited by sputtering using a MANTIS QUBE system. The polystyrene spheres were then removed by tape lift-off or by sonication in ethanol for at least 10 min, revealing the nanohole patterns.

Characterization of DNHs samples

Aperture characterization and cusp size measurement were performed using SEM imaging (Hitachi S-4800). The cusp size is defined as the minimum distance between overlapping regions of the two holes. To enable fast localization under the CCD camera during trapping, a fiducial mark was scratched at the center of each sample. SEM images were imported into FDTD simulation software for further analysis in SI.

Preparation of trapping solution for EVs

Ectosomes and exosomes are two major classes of EVs. Ectosomes directly bud from the plasma membrane with a size range of 100–1000 nm, and exosomes originate from endosomal pathways with a size range of 30–150 nm80,81. Given the challenge of separating exosomes from ectosomes using standard EV isolation techniques like ultracentrifugation, the MISEV 2023 guidelines recommend classifying EVs smaller than 200 nm as small EVs and those larger than 200 nm as large EVs82. The size distribution of EVs can be found in Table 2. This is comparable to the gap size. Larger EVs are expected to sit above the gap based on the electromagnetic field distribution.

EVs were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to final concentrations of 0.112 μg/μl for MCF10A, 0.494 μg/μl for MCF7, and 0.191 μg/μl for MDA-MB-23111. Glass cover slides (Gold Seal, 24 × 60 mm, No. 0, 85–130 μm thickness) were cleaned with isopropyl alcohol and dried with compressed nitrogen, then placed on a cooled metal block at 4 ∘C to prevent sample degradation. A double-sided adhesive microwell spacer (Grace Bio-Labs, GBL654002) was attached at the center of each slide, and 9.37 μl of diluted EV solution was pipetted into the well. The gold DNH sample was placed on top to fully immerse the apertures in the EV solution. After applying objective oil, the assembled EV-DNH sample was mounted on the 3D stage between the objectives in the trapping setup. The full assembly procedure is shown in Supplementary Fig. S4.

Transmission electron microscopy sample preparation and imaging of EVs

We acquired high-resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images at the University of British Columbia, Bioimaging Facility. Specifically, EVs isolated from MCF7, MCF10A, and MDA-MB-231 cell lines were visualized under identical imaging conditions to ensure consistency in subsequent analyses (Supplementary Fig. S2).

After isolation, EVs were fixed by mixing 1:1 with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences). The fixed EVs were then drop-cast onto glow-discharged copper grids (15 μA for 60 s; Electron Microscopy Sciences) with a mesh size of 300 and type-B carbon coating. The samples were left for 10 min to allow the EVs to settle onto the grid, after which the excess suspension was carefully blotted away using filter paper. The grids were subsequently stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 60 s to enhance image contrast. Finally, the prepared samples were imaged using an FEI Tecnai Spirit TEM operated at 120 kV, with an accelerating voltage set to 80 kV.

Optical trapping setup

Figure 1 shows a simplified schematic of the trapping setup, with detailed assembly in Fig. S2. The system uses a 980 nm continuous-wave laser (JDS Uniphase SDLO-27-7552-160-LD) for both trapping and probing. Beam alignment is controlled by a half-wave plate and polarizer, followed by collimation, filtering, and beam expansion before focusing on the DNH sample with a 100× oil-immersion objective (NA 1.25). The sample stage includes piezoelectric adjusters for precise positioning. Transmitted light is collected by a 10× objective and detected by an avalanche photodiode (Thorlabs APD-120A). During alignment, the CCD camera resolves only the white apertures, while DNH confirmation relies on APD voltage changes under varying polarization, as described previously83; a significant voltage shift indicates proper DNH geometry.

-

Mount the EV-DNH sample on the 3D stage.

-

Activate the laser at low power and mark the beam position using the CCD camera.

-

Align the beam to the target DNH and adjust the sample-objective distance to locate the focal spot; refine alignment with piezoelectric control.

-

Increase laser power and rotate the half-wave plate to optimize trapping at a well-formed DNH.

Single EVs trapping data acquisition

A data acquisition system (DAQ) with a 100 kHz sampling rate recorded the transmission signals during trapping. Voltage outputs from the APD were monitored using DAQNavi Datalogger software. Data post-processing was performed with custom Python scripts. A new DNH was found for each trapping event, and all DNHs were able to trap. Therefore, the number of double nanoholes used equals the number of trapping events.

Composition of optical trapping EVs datasets

The dataset used for model development consists of 502 independent optical trapping sessions collected across multiple days, involving different experimental operators, EV batches, and multiple colloidally fabricated DNH structures with cusp sizes ranging from 91 nm to 121 nm. Specifically, it includes 152 sessions for MDA-MB-231, 216 for MCF7, and 134 for MCF10A. To ensure consistent and unbiased input, each session was segmented into 1-s intervals, and the raw transmission signals were downsampled from 100 kHz to 500 Hz prior to training. This sampling rate preserves the key temporal features of EV trapping dynamics, effectively reduces high-frequency noise, and significantly lowers data volume and computational cost. Importantly, this setting is consistent with our previous work, enabling comparative analysis. Further reductions in sampling rate (e.g., to 100 Hz) were evaluated but resulted in diminished classification performance, suggesting that some relevant information is retained at high-frequency components.

Each of the trapping sessions was recorded for an average duration of 5 s and divided into five non-overlapping 1-second intervals, yielding 3267 complete segments. These segments were pooled and randomly split into training, validation, and testing subsets at an 8:1:1 ratio. (Fig. 1). Most data were allocated for training, with the validation set used for hyperparameter tuning and convergence monitoring. We implemented early stopping with a defined patience parameter, which halts training after a set number of epochs without improvement in validation loss. This strategy stabilizes training, avoids overfitting, and reduces unnecessary computation.

Modeling, training, validating, and testing

Data loader preparation

The processed dataset includes 3267 observations, each with extracted features and labels. Data were converted to PyTorch tensors and compiled into a custom EVDataset. Data loaders were configured for each subset with a batch size of 6 to enable efficient, randomized access during training and evaluation. To ensure generalization, all reported metrics were computed exclusively on the held-out test set, which was strictly isolated from training and validation, thereby preventing any risk of data leakage across the experimental splits. To preserve the biophysical integrity of the trapping signals, we did not apply artificial data augmentation such as noise addition or time shifting, which could introduce distortions unrelated to the underlying EV dynamics.

Training process

The training iteration setting was fixed at 8000 epochs but with early stopping implemented to prevent overfitting. The early stopping mechanism monitors validation loss and terminates training if no improvement is observed for 200 epochs (patience). During each epoch, the model processes batches of data, computes the loss, and updates the model parameters using backpropagation and the adaptive moment estimation (Adam) optimizer. Training/validation loss and accuracy are recorded for monitoring the model’s learning progression.

Validation and model selection

Beyond the training process, model performance was continuously monitored on the validation set to prevent overfitting. Validation loss and accuracy guided hyperparameter tuning, and the best-performing model was saved for final evaluation on the test set. The loss curves are shown in SI.

Testing and performance evaluation

After identifying and saving the best models, they were loaded and tested on the unseen test set to evaluate generalization to avoid any data leakage concerns. The testing phase included calculating accuracy, F1 score, recall, and average loss. A confusion matrix was generated to assess performance across different classes.

Baseline methods

CNN

To ensure a fair comparison with TrapNet, the ConvNet model was designed with identical convolutional layer configurations. This eliminates performance variations due to architectural differences, focusing only on the models’ learning capabilities.

The CNN starts with a Conv1 layer (128 filters, kernel size 3), maintaining the same output length as the input. Conv2 uses 256 filters to refine features and detect more complex patterns. Conv3 increases complexity further with 512 filters, capturing comprehensive data aspects. Conv4 tops the sequence with 2048 filters for extensive feature representation, supporting accurate classification. Each convolutional layer is followed by Layer Normalization (norm1 to norm4), stabilizing training by normalizing layer outputs. ReLU activations are applied post-normalization to introduce non-linearity. After convolution, adaptive average pooling is applied, followed by a dropout layer (rate = 0.6) to prevent overfitting. Finally, a fully connected layer maps the pooled features to three output classes corresponding to different EV types.

LSTM

LSTMNet is built with unidirectional LSTM layers that process input features sequentially, preserving temporal information. The network consists of six LSTM layers, each with 512 hidden units, enabling the extraction and retention of long-range dependencies. A linear transformation follows the LSTM layers, reducing dimensionality to 256, with ReLU activations to introduce non-linearity and dropout regularization (rate = 0.6) to prevent overfitting. A final linear layer maps the processed features to three output classes.

Bi-LSTM

Bi-LSTM uses bidirectional LSTM layers as its core component, with 1024 hidden units across six layers. Unlike unidirectional LSTMs, which only process information from the past, Bi-LSTM processes data in both forward and backward directions, effectively doubling the hidden state’s dimensionality. This bidirectional approach allows the model to capture more comprehensive dependencies and features. Following the Bi-LSTM layer, a linear transformation reduces the concatenated forward and backward hidden states (2048 units) to 256 units. This reduction is followed by ReLU activations to introduce non-linearity and dropout regularization to prevent overfitting. A final linear layer projects the features to three output classes corresponding to the different types of EVs.

CLSTM

CLSTM combines the ability of both CNN and LSTM. CNN block: The first convolutional layer, Conv1, uses 128 filters with a kernel size of 3. Conv2, Conv3, and Conv4 increase the filters to 256, 512, and 2048, respectively, with kernel sizes up to 7. Each layer is followed by layer normalization and ReLU activation, stabilizing training and introducing non-linearity for learning complex features. Layer normalization (norm1 to norm4) ensures consistent output scaling, improving convergence and enabling unbiased comparison with TrapNet.

LSTM block: After the convolutional layers, the model includes a bidirectional LSTM layer with 512 hidden units over 2 layers. This captures long-term dependencies by processing CNN features in both forward and backward directions, providing a comprehensive understanding of temporal dynamics. The LSTM output is passed through global average pooling to reduce dimensionality while retaining key temporal features, followed by dropout for regularization. The final fully connected layer maps the LSTM output to three classes, corresponding to the different EV types.

Transformer

The Transformer network begins with a Conv1d encoder layer, which embeds the input sequences. This layer processes 1-dimensional data with one input channel and transforms it into an embedding dimension of 16 features. A positional encoding tensor (1 × 1000 × 16) is added after the embedding layer, allowing the model to adaptively fine-tune positional influences during training. The Transformer encoder is built using PyTorch, with an embedding dimension (d_model = 16) and 2 attention heads (num_head = 2). A dropout rate of 0.5 is applied to regularize the training and prevent overfitting. The feedforward network within the encoder has a dimension of 512, providing greater capacity for processing information. The model uses num_layers = 1, with the option to adjust the number of layers for different task complexities. After the encoder, a pooling layer, and a fully connected layer map the output to three EV classes.

Despite the Transformer’s attention mechanism, we opted for a simpler model. Transformers are sensitive to noise-like patterns in the trapping data, as seen in Fig. 1, which could interfere with feature extraction and interpretation. Additionally, Transformers can capture more features at the same parameter level compared to CNNs or LSTMs, but this increases the risk of overfitting. Therefore, given the characteristics of our data, the Transformer architecture was deemed unsuitable for classifying the optical trapping data.

A comparison of the six deep learning models can be found in Table 1. All models return latent representations from the final layer, which are used for interpretation analysis in this work.

Feature extractions

We aim to understand how the deep learning network classifies noise-like optical trapping signals across three types of EVs. Latent space representations refer to the internal features or encodings that the network learns during training, capturing underlying patterns within the data.

In TrapNet and pure ConvNet architectures, latent representations are extracted after successive convolutional and activation layers. Each convolutional layer applies filters to capture spatial hierarchies of features, with representations becoming more abstract as they pass through deeper layers. Early layers capture signal volatility and intensity, while deeper layers encode more complex patterns, such as power spectral density in time-series data. The final latent representation is taken from the output of the last convolutional layer. In LSTM, Bi-LSTM, and CLSTM networks, latent representations are extracted from the output of the LSTM layers. In the Transformer model, latent representations are similarly derived from the output of the attention mechanism.

To analyze the spectral properties of the optical trapping signals, we used Welch’s method to compute the PSD for each sample. This method segments the time-series data into overlapping windows, computes the Fourier transform for each segment, and averages the resulting power spectra. We set the sampling frequency to 1.0 Hz and used a segment length of 250, balancing frequency resolution and statistical reliability. PSD values were calculated and stored for each batch of input data, capturing the frequency-domain representation of the optical trapping signals.

To visualize the distribution of latent features learned by each deep learning model, we applied t-SNE to the latent representations extracted from both the training and testing datasets74. These representations were obtained by forwarding each input through the trained model and capturing the output from the final feature layer—for instance, the last convolutional layer in ConvNet-based architectures or the final hidden state in LSTM variants.

The t-SNE implementation was based on the TSNE class from scikit-learn. We projected the high-dimensional latent space into two dimensions (ncomponents = 2) to enable visual inspection of class separation and feature clustering. A perplexity value of 30 was selected to balance sensitivity between local and global data structures, which is appropriate for datasets of this scale. The learning rate was set to 200 to ensure stable convergence during optimization, and the number of iterations (niter) was set to 1000, allowing sufficient refinement of the embedding. A fixed random seed was used to ensure reproducibility of the visualization. Euclidean distance was used as the similarity metric in the high-dimensional latent space.

To reduce visual clutter and improve interpretability, we randomly sampled 1000 data points from each dataset for plotting. Each point was color-coded by its EV class label. To enrich the visualization with spectral information, we scaled marker sizes according to the mean PSD of each signal. For each 1-s segment, the PSD was computed across all frequency components using Welch’s method, and the resulting mean PSD value was transformed using log(1 + PSD) for normalization, followed by min-max scaling. This allowed signals with lower dynamic content (e.g., from MDA-MB-231) to appear as smaller markers, and those with higher spectral activity (e.g., from MCF10A) as larger markers, highlighting characteristic differences across EV types.

Hardware and software

All operations, including EV signal post-processing, deep learning model training, feature extraction, testing, and results visualization, were performed on computing setups with NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2060 and RTX 4060 GPUs paired with Intel i7-11700 and AMD Ryzen 9 7845HX processors, respectively. The environment was built on Python 3.9.7, with key libraries including torch (1.10.1), scikit-learn (1.2.2), scikit-tda (1.1.1), matplotlib (3.7.0), and numpy (1.21.2).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available at the following repository: https://github.com/layallan/TrapNet_EVs.

Code availability

The code associated with this manuscript is publicly available at our GitHub repository: https://github.com/layallan/TrapNet_EVs.

References

Zhou, J. et al. High-throughput single-ev liquid biopsy: rapid, simultaneous, and multiplexed detection of nucleic acids, proteins, and their combinations. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc1204 (2020).

Van Niel, G., d’Angelo, G. & Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 213–228 (2018).

Mathieu, M., Martin-Jaular, L., Lavieu, G. & Théry, C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 9–17 (2019).

Carney, R. P. et al. Harnessing extracellular vesicle heterogeneity for diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Nat. Nanotechnol 20, 14–25 (2025).

Bordanaba-Florit, G., Royo, F., Kruglik, S. G. & Falcón-Pérez, J. M. Using single-vesicle technologies to unravel the heterogeneity of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Protoc. 16, 3163–3185 (2021).

Morales, R.-T. T. & Ko, J. Future of digital assays to resolve clinical heterogeneity of single extracellular vesicles. ACS Nano 16, 11619–11645 (2022).

Chen, H., Huang, C., Wu, Y., Sun, N. & Deng, C. Exosome metabolic patterns on aptamer-coupled polymorphic carbon for precise detection of early gastric cancer. ACS Nano 16, 12952–12963 (2022).

Kapoor, K. S. et al. Single extracellular vesicle imaging and computational analysis identifies inherent architectural heterogeneity. ACS Nano 18, 11717–11731 (2024).

Liang, J. et al. Deep learning supported discovery of biomarkers for clinical prognosis of liver cancer. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 408–420 (2023).

Zeune, L. L. et al. Deep learning of circulating tumour cells. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 124–133 (2020).

Peters, M. et al. Classification of single extracellular vesicles in adouble nanohole optical tweezer for cancer detection. Journal of Physics: Photonics 6, 035017 (2024).

Ciarlo, A. et al. Deep learning for opticaltweezers. Nanophotonics 13, 3017–3035 (2024).

Rao, L., Yuan, Y., Shen, X., Yu, G. & Chen, X. Designing nanotheranostics with machine learning. Nat. Nanotechnol 19, 1769–1781 (2024).

Chua, I. S. et al. Artificial intelligence in oncology: path to implementation. Cancer Med. 10, 4138–4149 (2021).

Natalia, A., Zhang, L., Sundah, N. R., Zhang, Y. & Shao, H. Analytical device miniaturization for the detection of circulating biomarkers. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 1, 481–498 (2023).

Cichos, F., Gustavsson, K., Mehlig, B. & Volpe, G. Machine learning for active matter. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 94–103 (2020).

Jordan, M. I. & Mitchell, T. M. Machine learning: trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 349, 255–260 (2015).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Yang, Z. et al. Ultrasensitive single extracellular vesicle detection using high throughput droplet digital enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Nano Lett. 22, 4315–4324 (2022).

Priglinger, E. et al. Label-free characterization of an extracellular vesicle-based therapeutic. J. Extracell. Vesicles 10, e12156 (2021).

Wang, F., Gui, Y., Liu, W., Li, C. & Yang, Y. Precise molecular profiling of circulating exosomes using a metal–organic framework-based sensing interface and an enzyme-based electrochemical logic platform. Anal. Chem. 94, 875–883 (2022).

Qin, C. et al. Dynamic and label-free sensing of cardiomyocyte responses to nanosized vesicles for cardiac oxidative stress injury therapy. Nano Lett. 23, 11850–11859 (2023).

Wu, N. et al. Ratiometric 3d dna machine combined with machine learning algorithm for ultrasensitive and high-precision screening of early urinary diseases. Acs Nano 15, 19522–19534 (2021).

Xiao, X. et al. Intelligent probabilistic system for digital tracing cellular origin of individual clinical extracellular vesicles. Anal. Chem. 93, 10343–10350 (2021).

Kruglik, S. G. et al. Raman tweezers microspectroscopy of circa 100 nm extracellular vesicles. Nanoscale 11, 1661–1679 (2019).

Qin, Y.-F. et al. Deep learning-enabled Raman spectroscopic identification of pathogen-derived extracellular vesicles and the biogenesis process. Anal. Chem. 94, 12416–12426 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Enabling sensitive phenotypic profiling of cancer-derived small extracellular vesicles using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy nanotags. ACS Sens 5, 764–771 (2020).

Stremersch, S. et al. Identification of individual exosome-like vesicles by surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Small 12, 3292–3301 (2016).

Langer, J. et al. Present and future of surface-enhanced Raman scattering. ACS Nano 14, 28–117 (2019).

Yang, Y., Zhai, C., Zeng, Q., Khan, A. L. & Yu, H. Multifunctional detection of extracellular vesicles with surface plasmon resonance microscopy. Anal. Chem. 92, 4884–4890 (2020).

Zhang, Q., Ren, T., Cao, K. & Xu, Z. Advances of machine learning-assisted small extracellular vesicles detection strategy. Biosens. Bioelectron. 251, 116076 (2024).

Zhang, X.-W. et al. Integral multielement signals by DNA-programmed UCNP–AuNP nanosatellite assemblies for ultrasensitive ICP–MS detection of exosomal proteins and cancer identification. Anal. Chem. 93, 6437–6445 (2021).

Penders, J. et al. Single particle automated Raman trapping analysis of breast cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicles as cancer biomarkers. ACS Nano 15, 18192–18205 (2021).

Premachandran, S. et al. Self-functionalized superlattice nanosensor enables glioblastoma diagnosis using liquid biopsy. ACS Nano 17, 19832–19852 (2023).

Lv, J. et al. Amperometric identification of single exosomes and their dopamine contents secreted by living cells. Anal. Chem. 95, 11273–11279 (2023).

Jalali, M. et al. MoS2-plasmonic nanocavities for Raman spectra of single extracellular vesicles reveal molecular progression in glioblastoma. ACS Nano 17, 12052–12071 (2023).

Xie, Y., Su, X., Wen, Y., Zheng, C. & Li, M. Artificial intelligent label-free SERS profiling of serum exosomes for breast cancer diagnosis and postoperative assessment. Nano Lett. 22, 7910–7918 (2022).

Ferguson, S. et al. Single-EV analysis (sEVA) of mutated proteins allows detection of stage 1 pancreatic cancer. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm3453 (2022).

Hong, C. & Ndukaife, J. C. Scalable trapping of single nanosized extracellular vesicles using plasmonics. Nat. Commun. 14, 4801 (2023).

Hong, I. et al. Anapole-assisted low-power optical trapping of nanoscale extracellular vesicles and particles. Nano Lett. 23, 7500–7507 (2023).

Marago, O. M., Jones, P. H., Gucciardi, P. G., Volpe, G. & Ferrari, A. C. Optical trapping and manipulation of nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 807–819 (2013).

Righini, M., Volpe, G., Girard, C., Petrov, D. & Quidant, R. Surface plasmon optical tweezers: tunable optical manipulation in the femtonewton range. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 186804 (2008).

Gordon, R., Peters, M. & Ying, C. Optical scattering methods for the label-free analysis of single biomolecules. Q Rev. Biophys. 57, e12 (2024).

Bustamante, C. J., Chemla, Y. R., Liu, S. & Wang, M. D. Optical tweezers in single-molecule biophysics. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 1, 25 (2021).

Juan, M. L., Righini, M. & Quidant, R. Plasmon nano-optical tweezers. Nat. Photonics 5, 349–356 (2011).

Verschueren, D., Shi, X. & Dekker, C. Nano-optical tweezing of single proteins in plasmonic nanopores. Small Methods 3, 1800465 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Plasmonic tweezers: for nanoscale optical trapping and beyond. Light Sci. Appl 10, 59 (2021).

Wu, B. et al. Directivity-enhanced detection of a single nanoparticle using a plasmonic slot antenna. Nano Lett. 22, 2374–2380 (2022).

Volpe, G. et al. Roadmap for optical tweezers. J. Phys. Photonics 5, 022501 (2023).

Li, N. et al. Algorithm-designed plasmonic nanotweezers: quantitative comparison by theory, cathodoluminescence, and nanoparticle trapping. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9, 2100758 (2021).

Raza, M. U., Peri, S. S. S., Ma, L.-C., Iqbal, S. M. & Alexandrakis, G. Self-induced back action actuated nanopore electrophoresis (sane). Nanotechnology 29, 435501 (2018).

Kotsifaki, D. G., Truong, V. G. & Chormaic, S. N. Fano-resonant, asymmetric, metamaterial-assisted tweezers for single nanoparticle trapping. Nano Lett. 20, 3388–3395 (2020).

Kotsifaki, D. G., Truong, V. G., Dindo, M., Laurino, P. & Chormaic, S. N. Hybrid metamaterial optical tweezers for dielectric particles and biomolecules discrimination. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.12878 (2024).

Yoo, D. et al. Low-power optical trapping of nanoparticles and proteins with resonant coaxial nanoaperture using 10 nm gap. Nano Lett. 18, 3637–3642 (2018).

Kotnala, A., Ding, H. & Zheng, Y. Enhancing single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy with simple and robust hybrid nanoapertures. ACS Photonics 8, 1673–1682 (2021).

Yoon, S. J. et al. Hopping of single nanoparticles trapped in a plasmonic double-well potential. Nanophotonics 9, 4729–4735 (2020).

Jensen, R. A. et al. Optical trapping and two-photon excitation of colloidal quantum dots using bowtie apertures. ACS Photonics 3, 423–427 (2016).

Pang, Y. & Gordon, R. Optical trapping of a single protein. Nano Lett. 12, 402–406 (2012).

Pang, Y. & Gordon, R. Optical trapping of 12 nm dielectric spheres using double-nanoholes in a gold film. Nano Lett. 11, 3763–3767 (2011).

Yang, W., van Dijk, M., Primavera, C. & Dekker, C. FIB-milled plasmonic nanoapertures allow for long trapping times of individual proteins. Iscience 24, 103237 (2021).

Yousefi, A. et al. Optical monitoring of in situ iron loading into single, native ferritin proteins. Nano Lett. 23, 3251–3258 (2023).

Yousefi, A. et al. Structural flexibility and disassembly kinetics of single ferritin molecules using optical nanotweezers. ACS Nano 18, 15617–15626 (2024).

Ying, C. et al. Watching single unmodified enzymes at work. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.06407 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Coupling perovskite quantum dot pairs in solution using a nanoplasmonic assembly. Nano Lett. 22, 5287–5293 (2022).

Ravindranath, A. L., Shariatdoust, M. S., Mathew, S. & Gordon, R. Colloidal lithography double-nanohole optical trapping of nanoparticles and proteins. Opt. Express 27, 16184–16194 (2019).

Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 404, 132306 (2020).

Siami-Namini, S., Tavakoli, N. & Namin, A. S. The performance of LSTM and BiLSTM in forecasting time series. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data 3285–3292 (IEEE, 2019).

Medel, J. R. & Savakis, A. Anomaly detection in video using predictive convolutional long short-term memory networks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1612.00390 (2016).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 37 (eds Guyon, I. et al.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Kan: Kolmogorov-Arnold networks. The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations https://openreview.net/forum?id=Ozo7qJ5vZi (2025).

Wheaton, S. & Gordon, R. Molecular weight characterization of single globular proteins using optical nanotweezers. Analyst 140, 4799–4803 (2015).

Van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9, 2579–2605 (2008).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 618–626 (2017).

Hinton, G. E. & Roweis, S. Stochastic neighbor embedding.Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst 15, 833–840 (2002).

Salmond, N. & Williams, K. C. Isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicles for clinical applications in cancer–time for standardization? Nanoscale Adv. 3, 1830–1852 (2021).

Chandran, V. I., Gopala, S., Venkat, E. H., Kjolby, M. & Nejsum, P. Extracellular vesicles in glioblastoma: a challenge and an opportunity. NPJ Precis Oncol. 8, 103 (2024).

Rieke, N. et al. The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ Digit. Med 3, 119 (2020).

Tashakori, A., Zhang, W., Wang, Z. J. & Servati, P. Semipfl: personalized semi-supervised federated learning framework for edge intelligence. IEEE Internet Things J. 10, 9161–9176 (2023).

Chiou, P. Y., Ohta, A. T. & Wu, M. C. Massively parallel manipulation of single cells and microparticles using optical images. Nature 436, 370–372 (2005).

Inamdar, S., Nitiyanandan, R. & Rege, K. Emerging applications of exosomes in cancer therapeutics and diagnostics. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2, 70–80 (2017).

Willms, E. et al. Cells release subpopulations of exosomes with distinct molecular and biological properties. Sci. Rep. 6, 22519 (2016).

Welsh, J. A. et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (misev2023): from basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 13, e12404 (2024).

Hajisalem, G. et al. Accessible high-performance double nanohole tweezers. Opt. Express 30, 3760–3769 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from the New Frontiers in Research Fund, Exploration Grant NFRFE-2023-00280. We also acknowledge the use of the Centre for Advanced Materials and Related Technologies (CAMTEC) facilities at the University of Victoria. Additionally, we thank the Bioimaging Facility at the University of British Columbia (RRID: SCR\021304) for their assistance and support in acquiring the electron microscopy images.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived and designed by H.Z., W.Z., K.C.W., and R.G. Data analysis and result interpretation were conducted by H.Z. and W.Z. The code development was led by H.Z., W.Z. T.Z. and T.C. were responsible for fabricating the DNH structures and performing the trapping experiments and data collections. H.Z. conducted the FDTD simulations. S.H. and K.C.W. provided the EV samples and TEM imaging. R.G. supervised the experiments, analysis, simulations, and theoretical framework of the study. All authors contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Zhao, T., Zhang, W. et al. Accurate label free classification of cancerous extracellular vesicles using nanoaperture optical tweezers and deep learning. npj Biosensing 2, 33 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00053-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00053-y